7 minute read

bella’s books

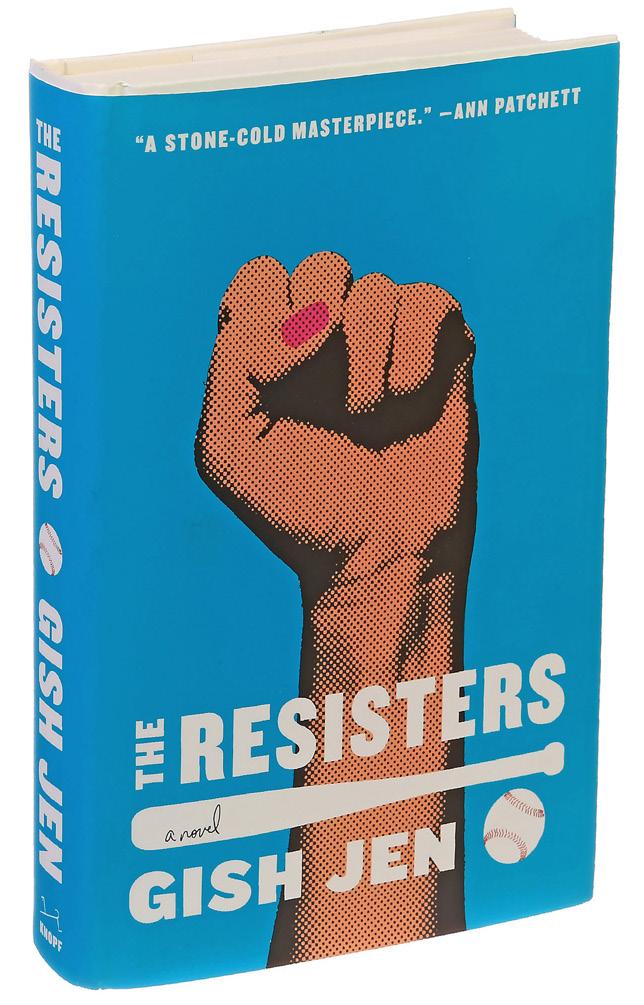

The Resisters By Gish Jen Gish Jen’s The Resisters depicts a future United States, dubbed AutoAmerica, where climate change and convenience culture have resulted in a waterlogged surveillance society. The lower Surplus class live in AutoHouses (or AutoHouseboats) and accumulate a kind of currency in the form of Living Points, which they earn from consuming the creations of the Netted, the producing upper class. All the while, the Surplus are subject to the watchful eye of Aunt Nettie, an ever-present version of the internet that doubles as a ruling power.

Like many other dystopian novels, The Resisters can be read as a cautionary tale. However, while the book has a lot to say about the general pitfalls of investing in a consumerist society, it more specifically demonstrates how the dream of class ascension in such a society is a cruel and complicated beast, and it does so through the most American of sports: baseball.

Advertisement

The story focuses on a Surplus girl named Gwen, whose extraordinary pitching ability gives her a chance to level up in life. (Though two of the main characters are young people, the book is written for an adult audience.) Much of the book’s rising action is tied to the question of whether or not Gwen will use her baseball talent as a ticket to attend college, a privilege not normally afforded to the Surplus, and possibly eventually “Cross Over” to the Netted class.

The book is narrated by Gwen’s father Grant, a former teacher who is racially categorized as “coppertoned.” His wife Eleanor, a lawyer of mixed Caucasian and Asian descent with a history of advocating on behalf of Surplus citizens, has twice been invited to Cross Over but refused, thereby becoming a “resister.” Dedicated as they are to solidarity with their fellow Surplus, Eleanor and Grant have mixed feelings about Gwen going to college and playing baseball for a Netted team, but they encourage her to explore her choices.

Gwen’s burgeoning success in the sports world is complicated by her friendship with Ondi, another mixed-race Blasian (Afro-Asian) girl who has her own ambitions where baseball and higher education are concerned. It soon becomes clear that the opportunities afforded to Gwen come at a price, as does being female and Surplus in baseball, which in AutoAmerica is a coed sport but still largely male and Netted. Pressures to conform to Netted norms when in Netted settings are great, to the point that a skin lightening procedure called PermaDerm is available for coppertoned people who want to appear “angelfair,” the whiteequivalent designation that applies to most of the members of the Netted class.

Ondi, who lacks the social currency and stability Gwen’s pitching skills bring her, appears to be more willing to conform to expectations at times, but also more prone to spontaneous acts of rebellion, which creates tension between the two. The plot points built around their struggles don’t just draw obvious parallels to racism in American society in general, but also raise questions about how adequate and meaningful current diversity and inclusion initiatives really are, especially when they focus on giving just a few marginalized people opportunities and then fail to change the hostile environments those opportunities put them in.

The stressful, ultra-connected atmosphere of AutoAmerica is

ArtDiction | 8 | March/April 2020 mercifully tempered by Eleanor and Grant’s countercultural habits: They avoid the “mall truck” food that would earn them Living Points, opting to grow their own vegetables and do their own baking. They home-school Gwen and teach her classic literature and history, rather than leaving her in the Surplus school environment, which prioritizes consumption over education. Through details like these, along with the presence of baseball itself—which seems relatively quaint in AutoAmerica—Jen effectively blends nostalgia for a mythical American past with the anxiety of a consumerist country forever reaching for the future, creating a society with new quirks that nevertheless doesn’t feel that dissimilar from our own.

At times, the book’s worldbuilding gets in the way of its plot development. Grant’s narration can feel overwhelming as he fits tangents and backstory into the current timeline while dropping myriad product names (DeviceWatch, DisposaCloth, etc.). The names are there to illustrate a point about the ubiquity of branding, of course, but the flow of Gwen’s story occasionally loses its momentum in her father’s

meandering references and exposition. However, this doesn’t stop the novel from arcing naturally to a satisfying, if sobering, conclusion. Much more than a cautionary tale, The Resisters feels like a generous space to sit with the sadder truths of our consumption-driven society. While it doesn’t shy away from the specifics of how a system lacking in basic humanity hurts people (and some more than others), it also shows faith that the forces able to overcome (or at least resist) such a system exist. - Reviewed by Elisabeth Cook

The Mercies By Kiran Millwood Hargrave It’s 1617 and a violent storm has claimed the lives of 40 fishermen off the coast of Vardø, a remote Norwegian settlement. Aside from a handful of elders, this amounts to almost the entire male population, leaving behind a devastated community of women and children. These women spend the next three years establishing a newfound selfsufficiency while navigating their immense collective grief. This matriarchy is interrupted by the arrival of Absalom Cornet, a God-fearing Christian and renowned witch hunter from Scotland. He is summoned by the King of Norway to bring the women of Vardø to heel once more, and to stamp out any lingering trace of native Sámi culture—its spiritualism and strong ties to the land considered an obstacle to establishing absolute reverence for his own God. With subtlety and tact, Kiran Millwood Hargrave explores the ingrained societal roles that define and separate us, with a particular focus on the trappings of gender and religion. Though distressed by their losses, the women of Vardø experience an unexpected liberty when forced to take over duties once reserved for men. Tensions already existed between those who followed Christian teachings and those who favored older Sámi ways, but a code of tolerance made room for everyone’s beliefs. It is only with the arrival of Cornet, and his tyrannical insistence that everyone follow the rule of the Church—lest they be accused of witchcraft—that frays begin to show. The women are increasingly forced to declare their loyalties, independence crushed by the vise-like grip of resurgent patriarchy. Differences that were once accepted are now the grounds for accusation, trial and certain death.

There is great sadness in witnessing this once harmonious community turning on itself—the corrupting power of fear driving former friends to betray each other in desperate bids to secure their own safety.

Among these women are Maren, a native of Vardø, and Ursa, Cornet’s new wife. The latter is plucked from the comparative splendor of a wealthy home in Bergen with all the grace and romance of a business transaction during Cornet’s journey from Scotland. Adjusting from life in a populous city in the southwest to the barren expanse of the icy north is no small feat, and through the two women’s blossoming relationship, Hargrave touches on the delicate task of bridging class divides, the pain of forbidden love and the quiet heroism of following your heart when daring to be different is enough to get you killed. In addition to presenting nuanced, multifaceted characters, the author skillfully evokes this particular time and place. Crystalline prose captures the raw power and awe-inspiring beauty of the landscape with equal fervor; the howl of the wind, the swell of the sea and the bite of salt practically leaping from the page. With such a vivid and transporting atmosphere, the reader remains fully invested in the story’s outcome, despite the sense of inevitable doom that comes with a novel inspired by true tragic events. The author does, in fact, manage to keep the reader guessing along the way to a surprising extent. Emotional beats hit at all the right moments, and the denouement is powerfully moving in its avoidance of anticipated tropes. The narrative is impressively fresh, especially as the author sticks close to the official version of events.

The horror of witch trials—how they were used as a front to exert control and wipe out so-called “undesirables”—has been explored in fiction many times before. It is to Hargrave’s credit that The Mercies feels no less emotionally engaging, factually enlightening, thematically resonant and narratively compelling as a result. She breathes life into the experiences of those too often relegated to mere statistics. If history books define victims of such trials by their deaths alone, this author asks us to remember them for the lives and loves they fought to defend. Snyder debunks pervasive myths (restraining orders are the answer, abusers never change) and writes movingly about the lives (and deaths) of people on both sides of the equation. She doesn’t give easy answers but presents a wealth of information that is its own form of hope. - Reviewd by Callum McLaughlin