17 minute read

Fighting for the Boys

by DFWChild

Parents of medically fragile children are 24/7 caregivers and advocates, waging everyday battles to give their kids the best life possible.

WORDS CARRIE STEINGRUBER

Advertisement

ick Schilling is medical mystery wrapped in a perpetual roguish grin. The 25-year-old’s diagnoses include autism, epilepsy and intellectual disability, but his body has also been gradually deteriorating for the past eight years, and genetic testing has yet to reveal why. He has feeding and digestive problems, muscle weakness and arthritis in both hips. When he walks, it’s only around the house, aided by orthotics and toting an IV pole. Nick RIGHT // Ethan Schilling talks with the help of an iPad. He loves storms, doesn’t need words to share his affection for his Christmas and Taylor Swift. older brother, Nick.

He is not a morning person. He is a flirt.

Nick’s timeline has stretched beyond his doctors’ prognoses, despite dozens of trips to the ER; in the past few years, Nick has been hospitalized with sepsis nine times.

“This boy bounces back,” Josh says. “Twelve hours after being septic and having a 15-inch scar on his stomach and 12 inches of colon taken out, he was sitting up and playing on his iPad and laughing.”

Josh laughs a lot too. He’s got a ruddy, boyish face and what can seem like an irreverent way of talking about his two sons’ acute disabilities. Perhaps the laughter is an unconscious coping mechanism, sharpened by years of trying to stay positive even though his oldest is on a timeline and his youngest will never be able to live independently.

Nick’s 11-year-old brother, Ethan, had brain surgery as a toddler; now he has a mesh patch on the back of his head, so falls (or headbanging, a past habit of his) can be dangerous. Unfortunately, he also has poor motor skills and a genetic neuropathy in his legs that makes him prone to falling. “He can be walking and then go numb at any second and trip and fall,” Josh explains.

Because of Ethan’s brain condition, called Chiari malformation, he is at risk of respiratory failure and aspiration. His food has to be cut into small pieces, and he can’t take liquids by mouth. Like his older brother, Ethan has intellectual disability and is nonverbal.

Between them, the boys have 18 doctors, nearly 50 prescriptions, and 230 hours of weekly nursing care.

“This is the life we were blessed with, and we’re going to make the best of it,” Josh says. “[But] every once in a while, it sneaks up on you and hits you. There was a bunch of boys Ethan’s age playing soccer, and I was like, Wow—that’s something my son’s never going to do. We don’t have a friend knocking on the door, and he’s never going to verbalize and say, ‘Hey, I’ll be back later!’ I did tear up for a minute, but then I got over it. He’s happy, he’s content. It’s not about me; it’s about him.”

Some families repeatedly wheel their medically fragile children to the steps of the state capitol, trying to persuade lawmakers to fix Texas’ dysfunctional Medicaid programs. Their work is noble, taxing, headline-making.

On the home front, meanwhile, these parents are feeding their kids through gastronomy tubes. Changing diapers. Cleaning IV ports. Scheduling appointments. Spending days on the phone with insurance companies battling for medications, supplies, therapies and nursing care. These acts of love are their daily advocacy. There is no time to take a breather, no putting it off till tomorrow.

“They’re pretty much advocating at all times,” says Ashlyn Estes, vice president of home health operations for Angels of Care—the company that provides nursing and attendant services for Ethan and Nick. “I feel like everything that they do for their children is a piece of advocacy because [the kids] don’t always have a voice to be heard, and so the parents are also their voice 24/7.”

When I first speak to Josh, he’s in the middle of a messy insurance situation. “I had seven phone calls today just for both boys’ enteral supplies,” Josh laughs. “It’s exhausting.”

For many moms and dads, exhaustion is one of the accepted costs of loving their children, and parents of medically fragile kids would tell you they’re doing no more than any parent would—it’s just that what is required of these families is extraordinary.

“They always have a long list of things that they have to do,” Estes says. “Their job is never done—not that any parent’s is, but theirs is definitely on a different level.”

“Wakey, wakey, artichokey!” Jackie Schilling chants as she rousts Ethan from under the covers one Friday morning. “Hey, you stayed all night in your bed!” Ethan’s neuropathies disrupt his sleep, so he sometimes wanders restlessly to his parents’ bedroom. Last year, he went six months sleeping only an hour a night. “So none of us got sleep last year,” Josh jokes.

Josh leaves for work early in the mornings— he has two full-time jobs—so his wife Jackie is in charge of getting Ethan and their 13-year-old daughter, Kiersten, off to school. Four days a week, Jackie also shuttles Kiersten to dance classes, a crucial outlet for the eighth grader, who understandably deals with a lot of anxiety.

Jackie used to work as a special education teacher, but she left her career to stay home with Ethan. “When Ethan had his brain surgery, no day care would touch him, and by the time Ethan was old enough for a full-day school, that’s when Nick’s health went downhill,” Josh explains.

On school days, limping out the door with one shoe on, Pop-Tarts in hand, is not an option. Jackie has to ensure that Ethan goes to the bathroom, receives his medications at the right time and eats breakfast without choking or aspirating.

Even at age 11, he can’t put on his clothes by himself—he leans against Jackie, hands on her shoulders, while she pulls up his jeans. Perhaps because he has a guest during this morning’s routine, Ethan is on his best behavior, all smiles and twinkly eyes. He’s a total ham. “We don’t usually have this easy of a time, do we, E?” Jackie says. “You don’t like to get out of bed, you don’t like to get on the potty, you don’t like to eat your breakfast…”

Eventually his nurse arrives, and she and Ethan head for the crosswalk, pulling a massive blue duffle that Jackie has packed with her son’s most important school supplies: nebulizer, oxygen, backup G-button, vital signs monitors, medications and a suction machine in case he gets sick during the day. “He’ll just be happy, then all of a sudden—symptoms,” Jackie explains.

The duffle represents a sampling of what’s in the Schillings’ at-home medical supply closet. It’s the size of a small bedroom, lined with industrial shelving and piled floor-to-ceiling with alcohol pads, wipes, gloves, suction filters, saline tubing. . . Ten to 15 boxes arrive weekly. (During the pandemic, as suppliers have rationed personal protective equipment, the Schillings have paid a lot out of pocket to obtain what they need. With Nick’s delicate central line, they can’t afford not to.)

The storage space is one of several features the family loves about their new house in Far North Dallas; No. 1 is the lack of stairs.

“For two years, myself and the nurses were carrying Nick up and down the stairs, and it was killing my back. And Ethan’s fallen down the stairs before,” Josh says. “So now we’re in a onestory. Nick loves it—he just keeps saying, ‘New house. No stairs!’”

Single-story living also gives Nick more freedom to roam. “He was just sitting on the couch all day, and we needed him to be able to have

choices and move around,” Jackie says. “He just has so many more options. He’s been so much happier.” Modifying a home—or finding a new one, like the Schillings did—is not uncommon for families with medically fragile children. In order to accommodate a child’s equipment, parents may install ramps and widen hallways. They may buy an extra refrigerator to store medications. The modification process is continual, both as the child’s needs change and as the parents age and become less able to lift their child into the bathtub or carry them upstairs. The Schillings haven’t been in their house long, but they’ve already made one significant (and unexpected) installation. When that violent microburst last June knocked out the power for four days, the family lost thousands of dollars of refrigerated medications, and the boys couldn’t access some of their critical, electricity-based treatments. “It was a nightmare,” says Josh. The state doesn’t cover the cost of a generator, so he went to work writing grant requests—a familiar process, since he’d done the same thing in order to buy their accessible van. He also told the story to their long-time electrician. As it turns out, the company decided to donate a generator to power the whole house. “That’s my goal and my wife’s goal, is to tell parents, ‘I know it’s exhausting, but don’t give up,’” Josh says. “‘Don’t give up, because that’s what people want you to do, because it’s hard.’”

As an advocate, Josh is bold, getting things done with smiles and persistence.

“If the boys are healthy, in a good week, I probably spend four to five hours on the phone or emails just fighting for the boys, and making sure their supplies are in,” he says. When one of the boys is sick, that time triples.

Several of Nick and Ethan’s doctors and home-health nurses have become indispensable advocates themselves. Nick’s intensivist (the ICU doctor who directs his care) “has kept Nick alive because of what he does,” Josh says. “He can move mountains”—for example, arranging for Nick to bypass the ER since he’s so susceptible to infection. The intensivist even gave Josh his cell number.

“I’ve got four of the doctors’ cellphone numbers,” laughs Josh. “We just text.”

He really leans on those relationships when insurance or Medicaid is involved. Fortunately for the Schillings, Nick and Ethan are on Josh’s insurance through work, with Medicaid as their secondary coverage. “That’s the only reason why every doctor and home health agreed to take us,” Josh says.

But when Nick turned 21, his state-funded care options became limited; one was placing him in a skilled nursing facility instead of keeping him at home. “We had to write letters, the doctor had to write letters, the doctor from the Health and Human Services Commission had to come out to our house, and we had to prove to him why putting him in a nursing home would kill our son,” Josh explains.

We could devote a whole magazine to parents’ daily toils in the trenches of insurance and Medicaid managed care. This year, the boys’ primary insurance changed, and Ethan had to switch to a new Medicaid managed care organization as well, meaning there was a chance that their doctors, nurses and medical suppliers would no longer be in network. Before the Sept. 1 deadline, Josh begged all their providers to either continue accepting their insurance or take the boys on a special basis. He worked for months to get all the sign-offs. Still, the changeover was chaotic. “It was phone calls, complaints, all of a sudden they aren’t covering that…” says Josh. “I think we’re in a good place now.”

On a Friday in February, Josh takes off work to chaperone the boys to a doctor’s appointment (where he reminds the doctor of the insurance signoffs he needs by Sept. 1). Afterward, the family has a brief interlude before Josh heads off to work.

It’s time for Mario Kart.

Josh, Jackie, Ethan and his nurse each grab a game controller, and Nick watches, smiling broadly and predicting who’ll be victorious. During each race, Josh keeps an eye on Ethan’s somewhat erratic progress. “Watch the road!” he suggests. “Use your mushroom!”

Ethan has improved at video games since the family got a Nintendo Switch, because his hands can better manipulate the controls. In the final race, he finishes fourth, besting the majority of the field. It’s a little thing, but as ABOVE // Nick was confined to the house until Josh applied for grants to buy an accessible van.the whole family cel- RIGHT // The family keeps ebrates and Josh gets two shelves’ worth of ready to leave, it feels diapers and bed pads. like a validation of the Schillings’ small, everyday efforts to make their boys happy.

Occasionally, Josh and Jackie allow themselves to feel the crush of exhaustion. “I don’t want to call and fight,” Josh admits. “You’re not supposed to have to shower your 25-year-old and even bathe your 11-year-old.

“But we have to remember, it’s not happening to us; it’s happening to our boys,” he continues. “We’re just along for the ride. Life could be worse. Our motto is ‘Everyone runs their own race.’”

This is how parents find the strength to make one more phone call. This is their north star when navigating thorny decisions. No matter what hopes they harbor for the future, they speak for their kids—and sometimes that means saying no to a treatment option, quitting a therapy, giving up distant possibilities in order to make life better for their children now.

As much as they can, the Schillings consult Nick and Ethan in these decisions. The boys may be nonverbal, but they do have voices. Last year doctors gave Nick the option of another surgery to shore up his deteriorating back muscles—he’d already had a rod put in his upper back. This second surgery, however, could permanently take away his ability to walk, or worse.

Josh and Jackie simplified the situation for Nick, and through his iPad, he said no to the surgery. “Our only option was to manage pain,” Josh says. “And that’s what we’re going to do.”

Because Nick is on a timeline, Josh and Jackie fight primarily for their oldest son’s happiness and comfort. They don’t advocate to prolong a life that Nick doesn’t want. Right now, he’s content, his pain is managed, and he has a purpose, Josh says. But someday, when those things are no longer true for Nick, his parents will advocate for him by giving him permission to let go.

About three years ago, Nick’s colon ruptured, and he needed emergency surgery. Before the operation, Josh had a moment with his son in the ICU. This had become a familiar scene: his son in a hospital bed, enduring the erosion of his physical body with an unquenchable happiness. But this time Nick was obviously in great pain.

“I told him, ‘Nicholas, if you’re tired, it’s OK to let go,’” Josh shares. “That was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever said.”

Then he laughs, and his voice is steady again.

“But it’s not about Jackie or I. It’s about him.”

ACCEPTING NEW STUDENT APPLICATIONS

Tuition Assistance Scholarships Available

Serving Grades PK–8TH

• Small Class Sizes & Individualized Approach to Learning • Reading/Writing Workshop Model • STEM Lab, Art, Music & Library Time • Spanish, PE and Recess Daily • Leadership & Community Service • Middle School - Mandarin, Innovation & Entrepreneurship Program • After School Care &

Enrichment Programs • Located in North Oak Cliff,

Convenient to Downtown Dallas

CALL OR VISIT US ONLINE FOR MORE INFORMATION

Now Enrolling 2 yrs–Kindergarten

A place where children come first

Virtual and In-Person Classes Small Class Sizes

www.htadallas.com 13555 Hillcrest Rd, Dallas, TX 75240 | 972.490.7060

SACS ACCREDITED

Serving students with learning challenges such as Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, Anxiety and ADD

IN-PERSON CLASSES USING COVID SAFETY MEASURES We use differentiated and multisensory instruction techniques, allowing for multiple intelligence and strength compensations

55 Main St. #290, Colleyville | 817-803-5010 INSPIREACADEMYTX.COM

Dana Judd, MEd, CALT, DLT Owner & Lead Instructor

All children are unique & marvelously made by God

CultivatingCharacter D AY - BY - D AY

Montessori Lower School Community TODDLER THROUGH GRADE 6

Join us for 2 upcoming events: https://bit.ly/2GZDRBc

PRE-K PARENT PREVIEW (online)

Thurs, Nov 5 • 6:30 pm

OPEN HOUSE

Sunday, Nov 15 • 1 - 4 pm Limited Spots Available - Reserve Today: dgiorgini@westwoodschool.org | 972-239-8598 THE WESTWOOD SCHOOL WestwoodSchool.org

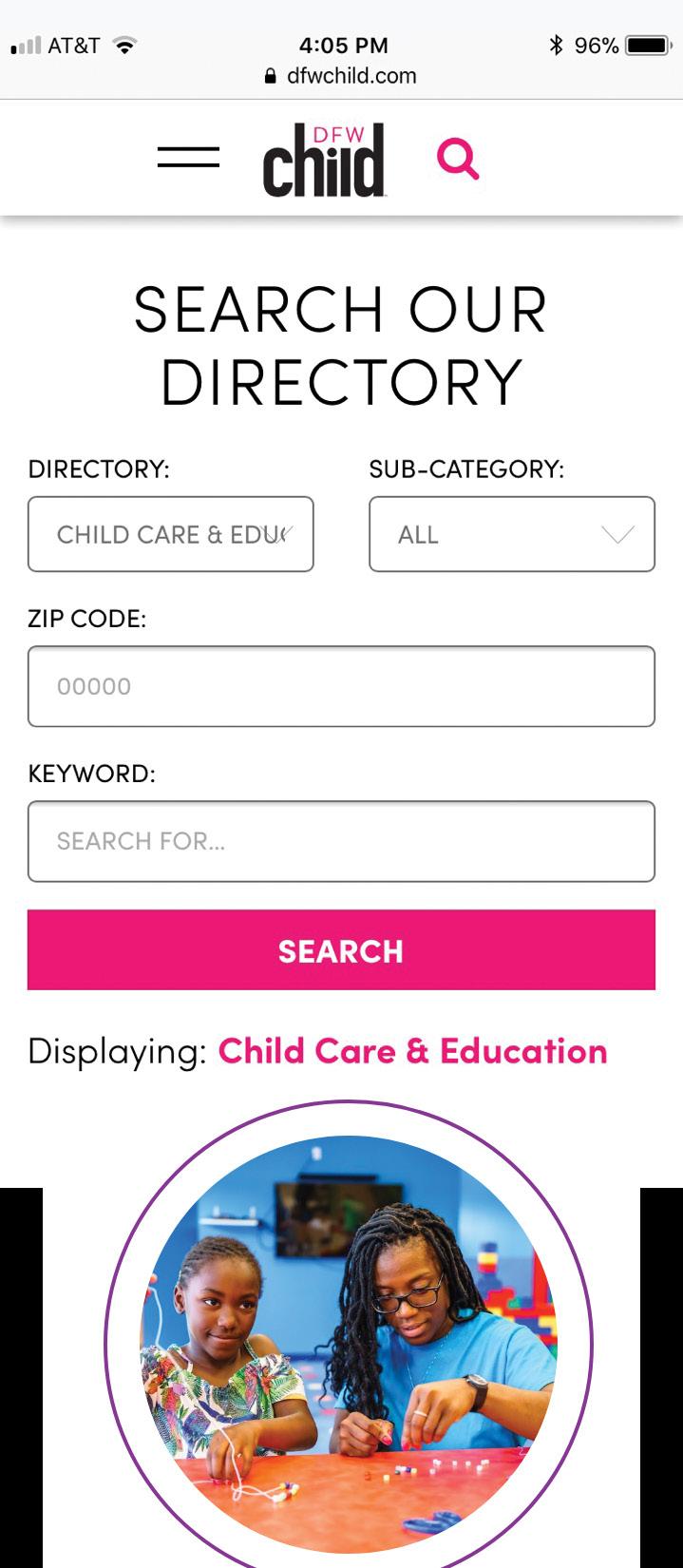

DFWChild.com Directory

Helping parents successfully navigate the childhood years is kind of our thing. Explore our not-so-secret weapon, the online directory, at dfwchild.com.

BOARDING SCHOOL G U I D E

Boarding school might be considered unconventional for some parents but leaving the nest sooner has its long-term benefits. From financial aid that precedes many private day schools to smaller class sizes and more time to explore electives, eliminating some of the stress in everyday life could help nurture a more well-adjusted child. If boarding school is something your family is considering, let our guide be your starting point.

Baylor School

High academic standards and the development of leadership skills in a coed environment are the hallmarks of a Baylor School education. Students from 23 states and 15 countries enjoy our 690-acre campus situated on the Tennessee River and surrounded by mountains, located just five minutes from downtown Chattanooga.

171 Baylor School Rd., Chattanooga, TN 37405 423/267-5902 baylorschool.org

Florida Prep

Located on Florida’s Space Coast, Florida Prep provides a challenging academic program to boys and girls in grades 5 thru 12.

Innovative course options and learning partnerships with local companies, equip Florida Prep students with real-world skills, and the tools, moral compass and strengths necessary to succeed at all levels.

1950 S. Academy Dr., Melbourne, FL 32901 321/723-3211 flprep.com

Wilbraham & Monson Academy

Wilbraham & Monson Academy offers a global experience for students from 30 countries, afternoon programming and the Center for Entrepreneurial, Economics & Finance department and Mark R. Shenkman Trading Center. Students have the opportunity to learn critical thinking and entrepreneurial skills, while creating a foundation for business, finance or entrepreneurial endeavors in the future.

423 Main Street, Wilbraham, MA 01095 413/596-9107 wma.us

Cushing Academy

Cushing Academy’s innovative curriculum develops curious and confident learners and ensures a transformative experience for every student at every level. With expansive visual and performing arts opportunities, a pioneering academic support program, renowned competitive sports, and numerous extracurricular activities, students build skills for college and beyond in a tight-knit, supportive, and diverse community.

39 School St., Ashburnham, MA 01430 978/827-7000 cushing.org

Doing Everything Right For Boys!

Salisbury is designed for boys to succeed in a place where traditions matter. Providing opportunities for one-on-one learning with an emphasis on building character. For more than 100 years Salisbury has been developing champions in the classroom and on the field.

Learn more about our first-class academic and athletic programs by visiting:

salisburyschool.org 860-435-5732

Woodside Priory School

California’s only co-educational, Benedictine, college preparatory boarding school. Spanning 50 acres, Priory is a community guided by the Benedictine values of spirituality, hospitality, individuality, community, and integrity. With an international student body, the Priory way is one of hospitality and following the sage wisdom of Saint Benedict by “listening with the ear of our hearts.”

Portola Valley, CA (Silicon Valley) 650/851-8221 • admissions@prioryca.org prioryca.org