4 minute read

Shining Examples

by dgilesltd

DIANA GREENWOLD

Mary Chase Perry Stratton (American, 1867–1961) Group of

Advertisement

Pewabic pottery

United States, Detroit, 1903–61

Clay with iridescent glaze; dims. variable Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1918.166, F1912.103, F1908.255, F1912.104, F1917.440, F1914.117, F1917.434

“In the Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C., contemporary ceramic art is represented by a single piece of pottery. This, a Pewabic vase, holding a place of honor in the Whistler Room, displays one of many unusual glazes developed by Mary Chase Stratton.” 1 So reads the introductory sentence penned by the New York Times reporter Adelaide Handy describing the vaunted display of Pewabic pottery in the Freer Gallery of Art in 1940. As Handy notes, works from this small-scale workshop in Detroit are anomalies in Charles Lang Freer’s collection—the only American objects that he collected for his museum, works designed to be viewed alongside masterpieces of Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and Near Eastern ceramics. That a Pewabic object rested in a “place of honor” in the Peacock Room, Whistler’s dazzling interior, is testament to the high esteem in which Freer and gallery curators held Stratton’s work. What appealed to Freer about Pewabic’s vessels, products of an arts-and-crafts-style workshop named for a Michigan copper-mining region? How did Freer and Stratton ignite curiosity in one another as collector and creator to develop these wares and to situate them within a collection of American painting and historic Asian art?

Like many women of her era, the Michigan-born Mary Chase Perry Stratton began her career as a hobbyist painting designs on porcelain blanks. She formalized her interests in art and ceramics as a student at the Cincinnati Art Academy, where she befriended successful ceramicists such as Maria Longworth Nichols and Louise McLaughlin. 2 After returning to Michigan, Perry met Horace J. Caulkins, a dentist who had repurposed an oven that hardened dental inlays into a portable ceramics kiln. The so-called Revelation Kiln subsequently became popular in small-scale workshops across the country. Using Caulkins’s technology, Stratton founded the Pewabic Pottery in 1903 and began creating matte vases with raised vegetal elements in the vein of Boston’s Grueby Faience Company. In operation from 1899 through roughly 1911, Grueby specialized in vessels with sculpted surfaces enhanced with matte glazes. By the end of the decade, Stratton had abandoned such sculptural details to focus instead on what she termed “painting with fire,” an effort to use glazes and oxides to produce artists did—a trial-and-error approach that may similarly have inspired his use of imitation leather in Map of My Mind (fig. 1).2 After his return to Japan, Kawakami’s prints mostly feature landscape scenes made from his North American sketches. He took his early efforts to the door of Yamamoto Kanae (1882–1946), the pioneering progenitor of the newly emerging “creative print,” or sōsaku hanga, movement. In traditional Japanese woodblock printing, prints were the product of many hands, as specialist carvers and printers were commissioned by a publisher to execute an artist’s design. By contrast, in so-called creative prints, the artist was personally responsible for every aspect of a print’s production. Yamamoto was not impressed with the young artist’s work, and his rejection was so brutal that Kawakami did not attempt printing again for two years.

However, by the late 1920s, Kawakami’s prints had attracted the attention of the leader of the sōsaku hanga movement, Onchi Kōshirō (1891–1955). In 1928 Onchi involved

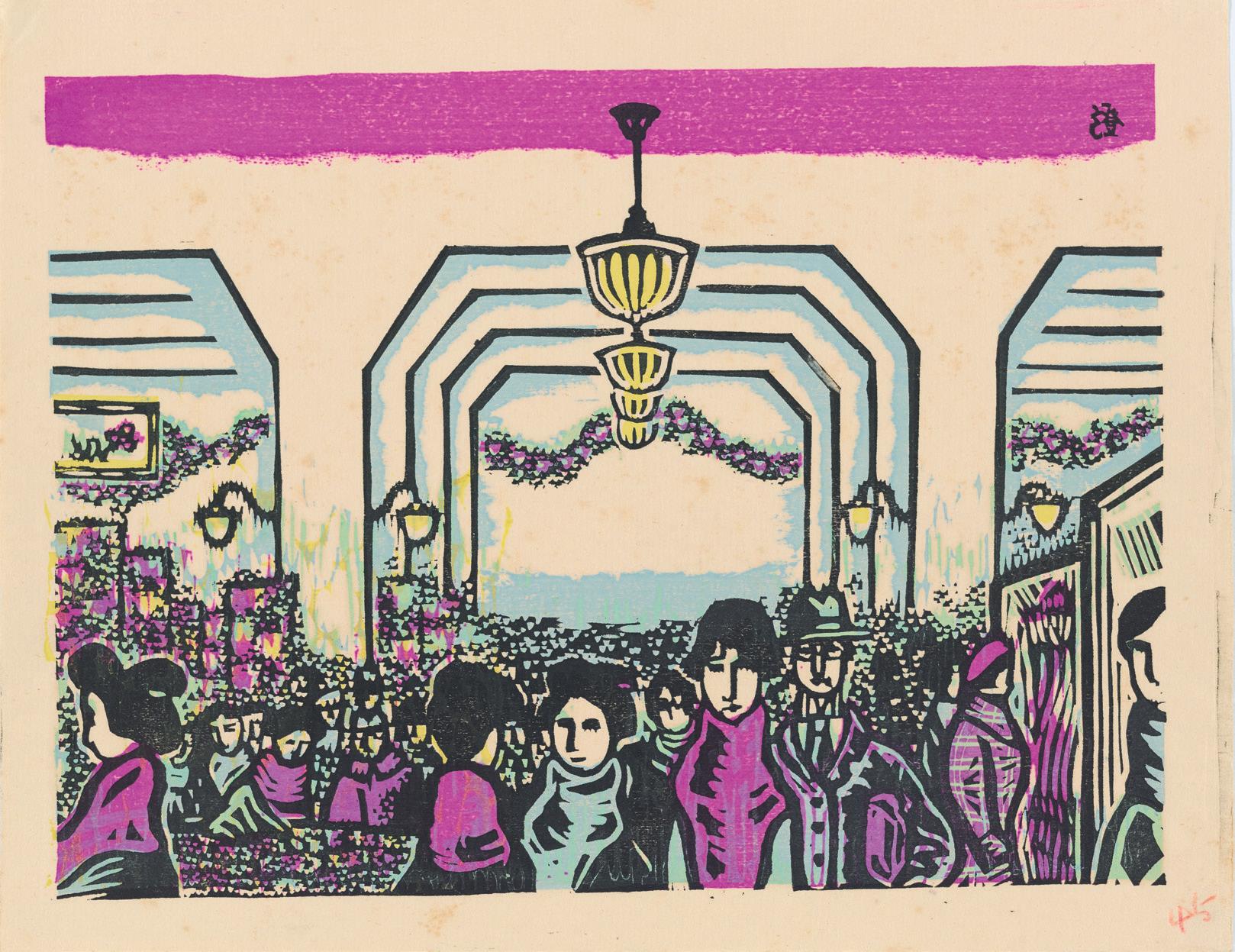

Kawakami in a major project involving several artists, One Hundred Views of New Tokyo (Shin Tōkyō Hyakkei). While celebrating some of the best-known traditional views of the city, the series also showcased visions of the new, modern metropolis, which had been rebuilt and redefined in the wake of the destruction caused by the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923. One of Kawakami’s contributions shows a sleek department store in the ritzy Ginza area (fig. 2). Not only are the location and the shoppers’ clothing modern, but the use of a bright chemical magenta also suggests the glowing charge of neon lights. Our knowledge that Kawakami had once wished to become a designer of departmentstore window displays creates an additional layer of personal significance.

After that series, Kawakami had relatively little involvement in the broader sōsaku hanga movement, and he claimed that this separation from artistic circles allowed him to freely pursue his own interests. While teaching English, Kawakami became a collector of antiquarian books and historic foreign-language dictionaries. He was particularly transfixed by artifacts generated through the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century encounters between Japan and the Portuguese, a genre known as nanban. 3 Although this idiomatic style marks him out among print artists, he was not alone in his interests. The early twentieth century also saw the emergence of nanban as a subject of scholarly attention, and the most significant collection of nanban art in the world, assembled by Ikenaga Hajime of the 1969 album Nashville Skyline , for which the portfolio is named. 4 In the early 1960s, Dylan recorded and released traditional American folk songs, but went on to break genre conventions by integrating political and literary influences with country music, rural themes, and the electric guitar. In 1969, Dylan recorded the American folksong “Nashville Skyline Rag” and popularized it through the Nashville Skyline record, thereby making it more widely available and accessible to a broader audience. Similarly, prints are multiples—more easily disseminated and appreciable by more people than singular paintings—and Ay-Ō sought to bring American folk paintings into a broader sphere.

Often portraits of loved ones or depictions of scenes with deep personal meaning, early American paintings were treasured by those who had commissioned them or received them as gifts directly from the artists. The episode depicted in Hicks’s painting is from the Biblical verses of Isaiah 11:6–9, an imagined future where creatures that are usually considered to be natural enemies coexist in a tranquil harmony, guided by the infant Christ. Such a rapprochement was particularly meaningful for Hicks, who hoped for a reconciliation to heal the schism in the Quaker community to which he belonged.5 The painting includes a cluster of figures on the left, illustrating the treaty between William Penn (1644–1718) and the Lenni Lenape tribe. Penn was a personal hero of Hicks, who regarded this moment as concrete instantiation of harmonious accord among men.6 Ay-Ō, who had been living in Lexington for two years by this time as an instructor at the University of Kentucky, depicts this episode without Hicks’s romanticized distortion of the realities of the exchange between these two peoples. Ay-Ō was certainly conscious of that history, remarking in his essay that his Kentucky residence was close to the descendants of those who had driven out the original inhabitants of the Appalachian Plateau “by force or by fraud.”7 In Ay-Ō’s version, the group has been stripped of color, effectively bleaching them from the rainbow paradise.