Limited, its publisher in the United Kingdom. I particularly wish to thank Dan Giles, Liz Japes, Susan Kelly, Allison McCormick, Louise Parfitt, and Louise Ramsay for their efforts in bringing Zao Wou-Ki: Watercolors and Ceramics , the book, to a successful and satisfying resolution. It is a pleasure working with you.

Every Dixon staff member and volunteer contributes in some way large or small to the success of everything we do, including our exhibitions and publications program. At this time, I thank Miguel Alcantor, Christan Allen, Melvin Avendano, Juliana Bjorklund, Melissa Bosdorf, Sarah Catmur, Theresa Cunningham, Chantal Drake, Jenny Duggan, Chris Emanus, Erika Fuller, Jeff Goggans, Braden Hixson, Gail Hopper, Mitzi Igleharte, Stuart Janssen, Susan Johnson, Robert Jones, Kristen Kimberling, Sarah Lorenz, Norma Montesi, Glenn Overall, Lorenzo Perez, Julie Novarese Pierotti, Adam Queen, Kristen Rambo, Christine Ruby, Kim Rucker, Margarita Sandino, Charity Saunders, Corkey Sinks, Dale Skaggs, Elizabeth Sloane, Karen Strachan, Kori Van der Bijl, and Julia Waters. There are too many Dixon volunteers to list each of them by name, but Suzanne Allen, Caroline Brown, Erin Daniels, Linda Eddins, and Phil McMillion always go above and beyond, as do so many others as well. My deepest thanks to these excellent colleagues. Yann Hendgen would like to extend his thanks to Ludivine Cottier, his colleague, who assisted with the bibliography and offered helpful comments on the design of this book.

Finally, I very much appreciate that some talented artists must be bold enough to find a place other than where they were born for their gifts to be nurtured and their

expressive impulses to take root and grow. For Zao Wou-Ki, the journey from China to France was long and sometimes difficult, but he discovered his place in Paris, a city then still recovering from a devastating war. We are the beneficiaries of his creative genius, but also of his personal courage. My last word of thanks goes to Zao Wou-Ki for the splendid works we are about to enjoy.

Kevin Sharp Linda W. and S. Herbert Rhea Director

Zao Wou-Ki, 1998

Friendship Foreword 10

Photo by Micheline Pelletier

Zao Wou-Ki

The Breath of Life

Gilles Chazal

Zao Wou-Ki is a marvelous example of the contribution a man can make to humanity when, in the process of building his character, and the creativity that flows from it, he allows very different cultural traditions—in this case, those of China and the West—to come together and co-exist within himself.

Zao was born in 1920 in Beijing, into a well-todo family dating back to the prestigious Song dynasty (960–1279)—prestigious thanks to the prosperity and the very rich cultural life that were implemented, most notably, by the scholar class. For centuries, these men of letters had formed a powerful elite with a solid intellectual education rooted in a knowledge of the foundational texts of Chinese civilization, in particular those of Confucianism and Taoism. They were masters of the complex practice of calligraphy, which is both an art of constructing thought and an art of communicating emotion.

Those scholars who regarded themselves as belonging mainly to the Confucian tradition were, as “good men,” deemed fit to serve the government. The self-professed Taoists, on the other hand, favored a more independent life devoted to poetry and painting. However, the boundary between these two currents was far from watertight.

Zao Wou-Ki’s grandfather was himself an accomplished man of letters. He took great pains to pass down to his grandson a very solid grounding in traditional culture. To begin with, he introduced him to the

art of calligraphy, a form in which word and image are inseparable. Zao learned how to handle a brush, to master the spread of ink-infused water on paper, to write, read, and paint, creating at once meaning and beauty. Again, thanks to his grandfather, Zao also gained in his youth a familiarity with the classic texts of Chinese civilization, especially those of Taoism. Many years later, in about 1956, Zao embarked on a collaboration with the poet Claude Roy (1915–1997) to produce a French translation of the Tao Te Ching by the master of Taoism, Laozi (Lao Tzu).1

At the age of fifteen, Zao Wou-Ki passed the entrance examination to the School of Fine Arts in Hangzhou, a city of some significance. South of Shanghai, rich and refined, Hangzhou is the outlet point of the Grand Canal, the longest of the ancient manmade waterways originating in Beijing. The capital of the Song dynasty in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Hangzhou is most notable for its position on the banks of the fascinating West Lake, surrounded on three sides by magnificent mountains. Embellished with features designed to express the harmonious union between man and nature, this landscape has been a source of inspiration for poets and artists since the ninth century (fig. 1). West Lake was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2021.

In the eighteenth century, this impressive setting was famously home to a group of admirable poet-painter scholars with Taoist leanings known as the Eight Eccentrics

17

Fig. 10.

Zao Wou-Ki (Chinese-French, 1920–2013) Homage to Françoise – 23.10.2003 – Triptych , 2003 Oil on canvas

76 3/4 × 127 1/2 in. (195 × 324 cm) Private collection

30

Zao Wou-Ki — The Breath of Life

Fig. 11. (Cat. 49)

Zao Wou-Ki (Chinese-French, 1920–2013)

Untitled (Maurice) , 2008 Watercolor on paper 22 3/8 × 30 in. (57 × 76 cm) Private collection

a descriptive text: “Story of two Canadian maples.” What was even more surprising was the presence in his studio of some photos of one of the two maple trees sent by Riopelle from his home in Canada, as a sign of faithful friendship overcoming geographical distance.

Three years later, in 2006, Zao began to work on another painting with a title, a canvas he called Orchids After years of distancing his art from visible reality, Zao was again allowing physical things to assert themselves

in the studio. As he worked, orchids were not far from his easel. Nature had returned to the very heart of his creative activity. But while he had turned his gaze back to the spectacle of the world around him, nature and observed reality remained absent from his painting, as had been the case since 1954. The orchids were there only to inspire a visual journey into the colored splendor of unlimited space. With age, Zao Wou-Ki became more peaceful. He gradually moved away from the arduous work of oil painting, and began to create impressive ink drawings on paper, luminous watercolors (fig. 11) on large white sheets, and painting on porcelain (fig. 12), a substance shot through with light. In 2006, he produced more watercolors than oil paintings, and they revealed a dazzling sense of ease in space, these explosions of color and dynamic movement.

In 2007, Zao Wou-Ki accepted an offer from his friend Dominique de Villepin, at the time prime minister of France, to leave the seclusion of his studio and to paint outdoors at La Lanterne, the prime minister’s official residence on the grounds of the Château de Versailles. To his wife’s surprise, Zao accepted the offer, and he produced radiant watercolors there. Painting in watercolor outdoors, surrounded by nature, marked a dramatic shift in his working method. Some of the late oil paintings were still produced in his studio, but many of the watercolors were created in the open air. In this last period, Zao’s artistic adventure would increasingly take place surrounded by the beauties of nature. However, as in the case of Orchids , his work transcended the immediate visible appearance of nature.

Gilles Chazal 31

Catalogue

Cat. 2

3.12.96 , 1996

Oil on canvas, 23 5/8 × 23 5/8 in. (60 × 60 cm)

38

Cat. 3

1.05.2001 , 2001

Oil on canvas, 19 5/8 × 24 in. (50 × 61 cm)

39

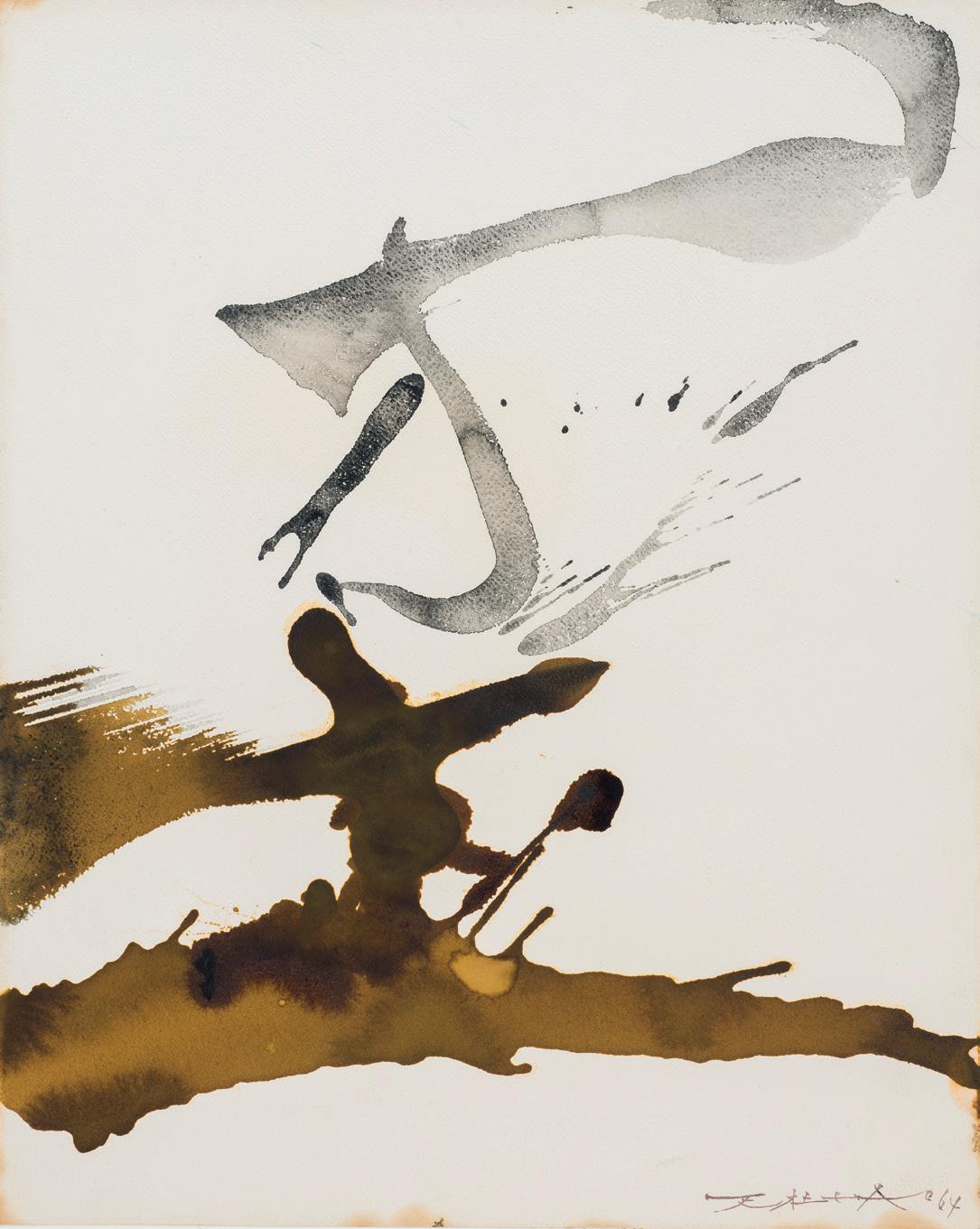

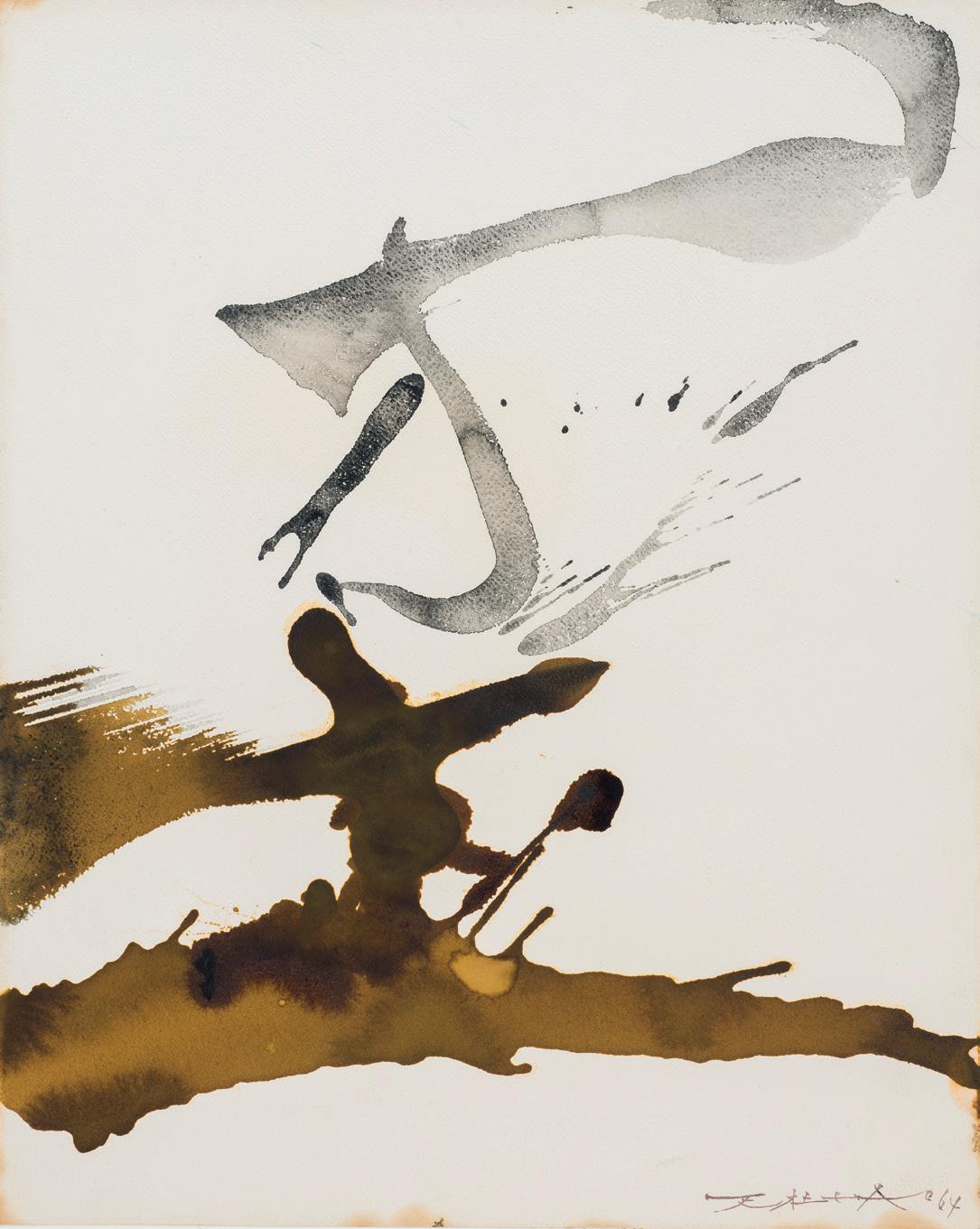

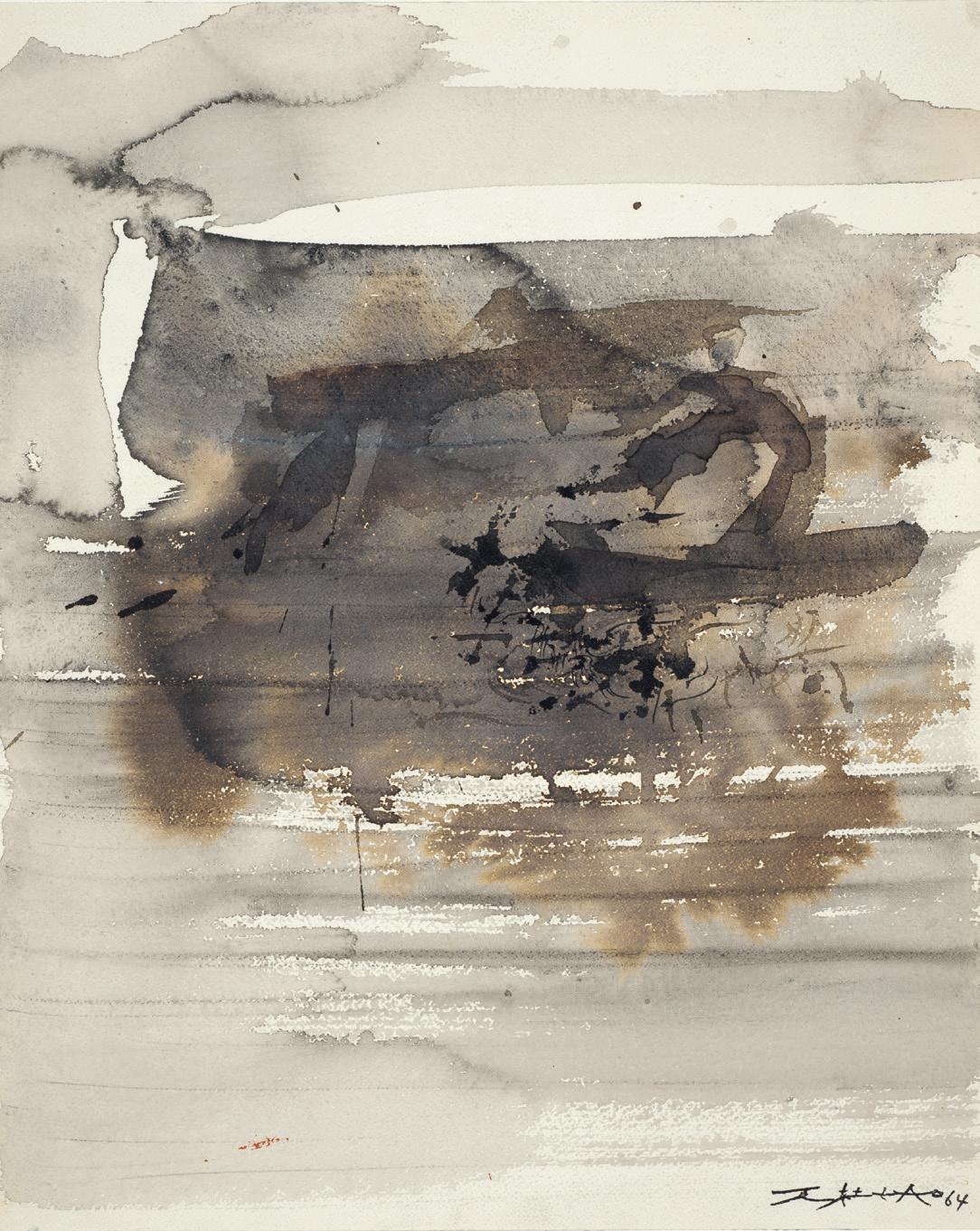

Cat. 5

Untitled , 1964 Watercolor on paper, 16 1/8 × 13 in. (41 × 33 cm)

Cat. 6

Untitled , 1964 Ink on paper, 16 3/8 × 13 1/16 in. (41.5 × 33.2 cm)

42

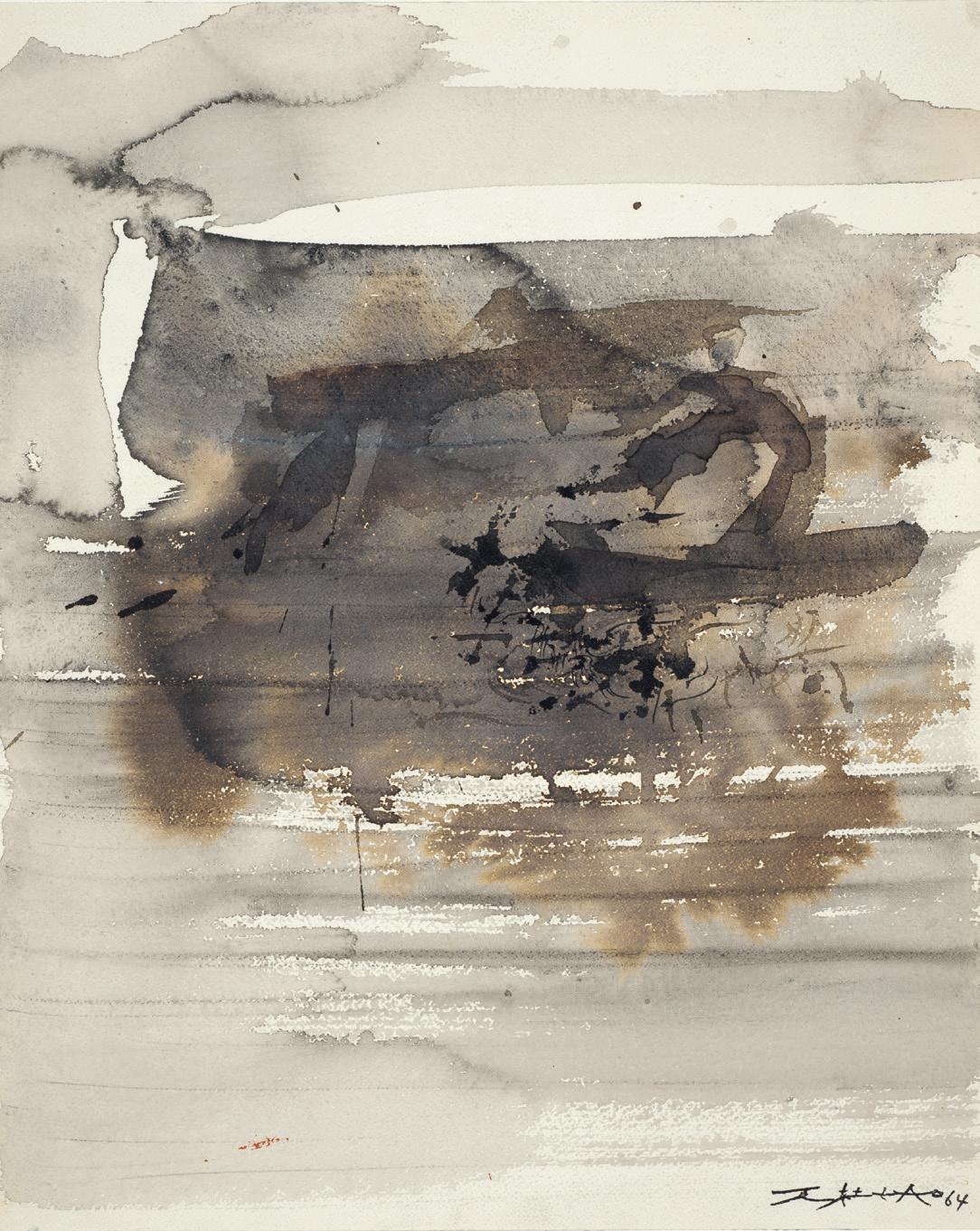

Cat. 7

Untitled , 1964 India ink and watercolor on paper, 19 5/8 × 25 5/8 in. (50 × 65 cm)

43

“Dare to use new colors, giving birth to new spaces, to invent lightness”

72

Zao Wou-Ki

Cat. 36

Untitled Triptych (Ibiza) , 2007 Watercolor on paper, 19 5/8 × 38 3/8 in. (50 × 97.5 cm)

73

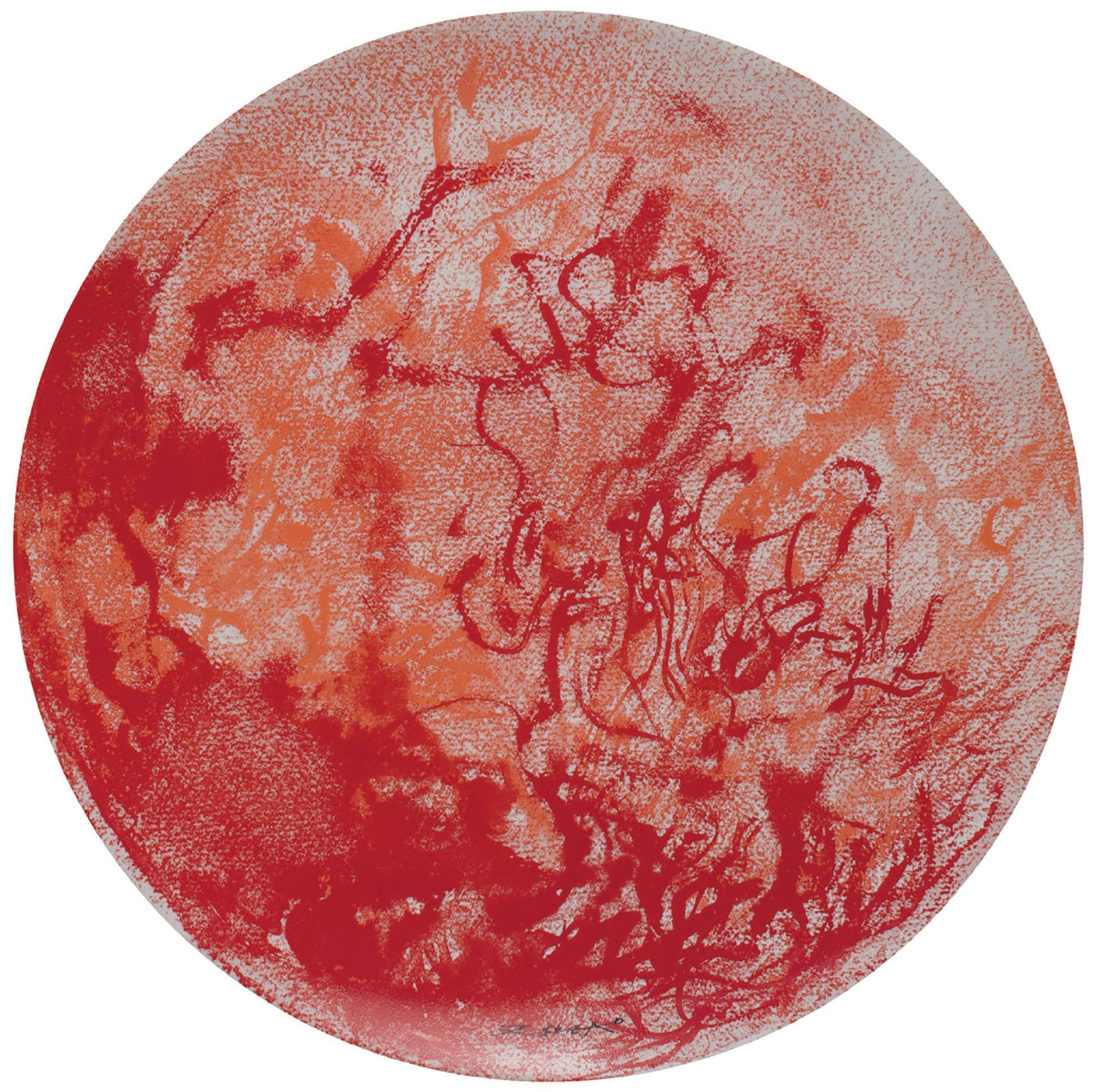

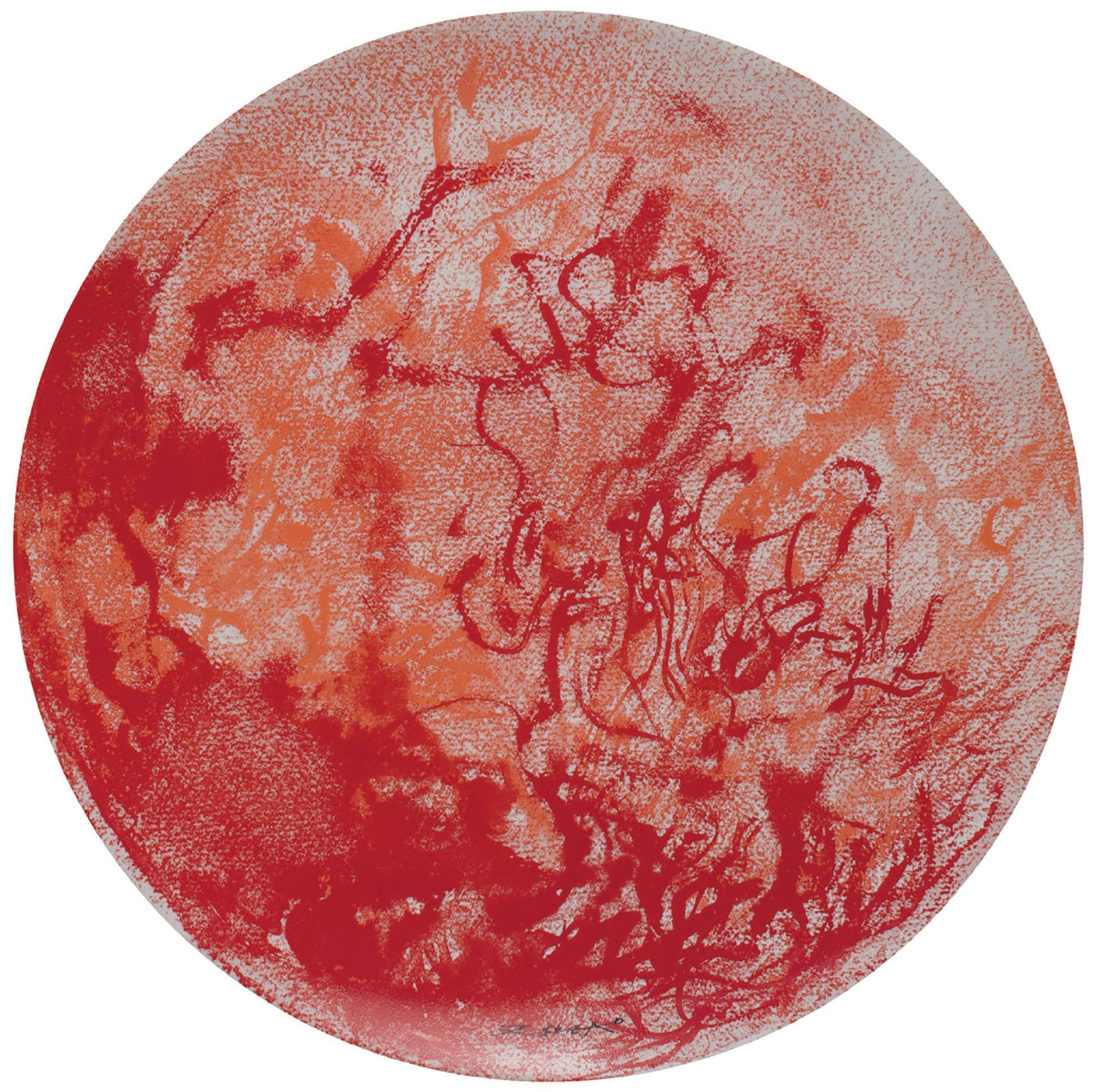

Cat. 68

Firestone plate, 2004 Bernardaud manufactory, Limoges Porcelain with lithograph after a watercolor by the artist, 14 1/8 in. (36 cm)

104

Cat. 69

Sandstone plate, 2004 Bernardaud manufactory, Limoges Porcelain with lithograph after a watercolor by the artist, 14 1/8 in. (36 cm)

105