HANDS-ON Experience Learning

Issue 22: September 2022

The legacy of Douglas and Eleanor Murray Invest in South Africa’s Potential

IN THIS ISSUE WE FEATURE:

LEARNING BRIEF 1

Strengthening Links in the Learning Chain: The Value of Accelerated Learning Programmes

In South Africa, poor reading proficiency in schools has been compounded by pandemic-era learning losses. Accelerated Learning Programmes (ALPs), in various forms, can help address this deficit because they are designed to support children who are constantly falling behind. This learning brief explores how ALPs can help fill the gaps in our schooling system.

LEARNING BRIEF 2 Think, Plan, Act and Adapt!

Ilifa Labantwana’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic provides important lessons for civil society on how to respond to increased demand for social services from low-resource communities in rural and semi-urban areas.

LEARNING BRIEF 3

Proactive Interventions to Build Stronger Learning Foundations

One of South Africa’s biggest developmental challenges is the large proportion of children who cannot read for meaning in early grades. Reading with comprehension is a fundamental skill upon which others are built. Children who do not have strong learning foundations are not equipped to read for meaning and, without adequate support, they struggle to reach their potential with long-term social- and economic consequences for the country. We can’t rely on schools alone to fix the country’s literacy problem as causal factors occur before children enter primary school.

page 11 4 16

Support young people to keep their grip on opportunity

HANDS-ON Experience Learning

Accelerated Learning Programmes

10STRENGTHENING LINKS IN THE LEARNING CHAIN: THE VALUE OF ACCELERATED LEARNING PROGRAMMES

In South Africa, poor reading proficiency in schools has been compounded by pandemic-era learning losses. Accelerated Learning Programmes (ALPs), in various forms, can help address this deficit because they are designed to support children who are constantly falling behind. This learning brief explores how ALPs can help fill the gaps in our schooling system.

Academic performance is influenced by a learner’s ability to read for meaning. But far too many children in South Africa’s schooling system lack this crucial skill. There are several reasons why; perhaps first and foremost is the long neglect of the early childhood development (ECD) 1 sector – a topic that is explored on page 11. Many children start school without the foundational building blocks they need to be ready to learn to read.

Children in the foundation phase (Grade R to Grade 3), learn the mechanics of reading (phonetics, sentence structure and sense-making), so that from the intermediate phase (Grade 4 to Grade 6) onwards, they can use these skills to acquire knowledge. Lessons move from “learning to read” to “reading to learn”, with pupils using textbooks to understand new concepts in various subjects in their school curriculum. The curriculum is built on the assumption that learning is linear, yet this is not the reality for many learners.

4Statistics tell us that even before the COVID-19 pandemic many children had weak foundational learning, particularly in literacy 2 and maths 3, but this does not mean there hasn’t been any progress in outcome trends since 20114 Nevertheless, the pandemic has set many children back. Due to disrupted schooling in 2020 and 2021, Grade 4 children lost 1.3 years 5 of learning according to the Department of Basic Education (DBE).

Socio-economic factors such as overcrowding in classrooms, lack of parental support and minimal reading resources in schools also contribute to the fact that many learners find themselves without the basic foundational literacy and numeracy skills they need when they enter Grade 4. According to education policy, learners who are failing academically are only allowed to repeat one year per phase of their schooling 6. Thus, children are progressed to the next grade regardless of their reading ability. Without effective remedial classes, the chain of learning is effectively broken. But the links can be reconnected.

1 According to Ilifa Labantwana, a programme seeking to ensure all children get access to quality ECD, only 20% of the seven million children who need subsidised early learning are receiving it.

2 https://nicspaull.com/2017/12/05/the-unfolding-reading-crisis-the-newpirls-2016-results/

3 https://www.gov.za/speeches/minister-angie-motshekga-and-humansciences-research-council-release-timss-2019-grade-9

4 https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/wp022020.pdf

5 https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/south-africanchildren-have-lost-13-years-of-schooling-due-to-covid-19-20220203

6 In 1998, the Admission Policy for Ordinary Public Schools was adopted which stipulates that the guideline for repetition is “one year per school phase where necessary”.

4 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR GRIP ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022

OPPORTUNITY

VICIOUS VERSUS VIRTUOUS

GOVERNMENT CANNOT DO IT ALONE

South Africa spends more than 6% of its GDP on education6 –among the highest in the world – and achieves among the poorest outcomes considering the size of the investment. This is largely the consequence of South Africa’s “inequality trap” where the poorest children, who often enter Grade 1 with learning deficits, typically receive poor quality education.

Through the lens of “formal education”, all children have the same endpoint but not all children reach it in the same amount of time. Civil society organisations are key players in creating enabling conditions for the realisation of education reform. This can be achieved by capacitating schools to implement programmes with the aim of improving education outcomes.

Accelerated Learning Programmes (ALPs) or “catch-up” initiatives are implemented in various countries to support vulnerable children who do not have access to schooling because of crises, conflicts or dropping out of school. Typically, the learning process happens over a short period of time. ALPs differ from education enrichment, weekend classes or holiday programmes aimed at improving learning outcomes. They are designed to support children who are below the expected academic level for their age group and to bridge the essential learning gap, thus strengthening the chain of learning.

DGMT-funded projects are involved in ALPs aimed at redressing educational inequity:

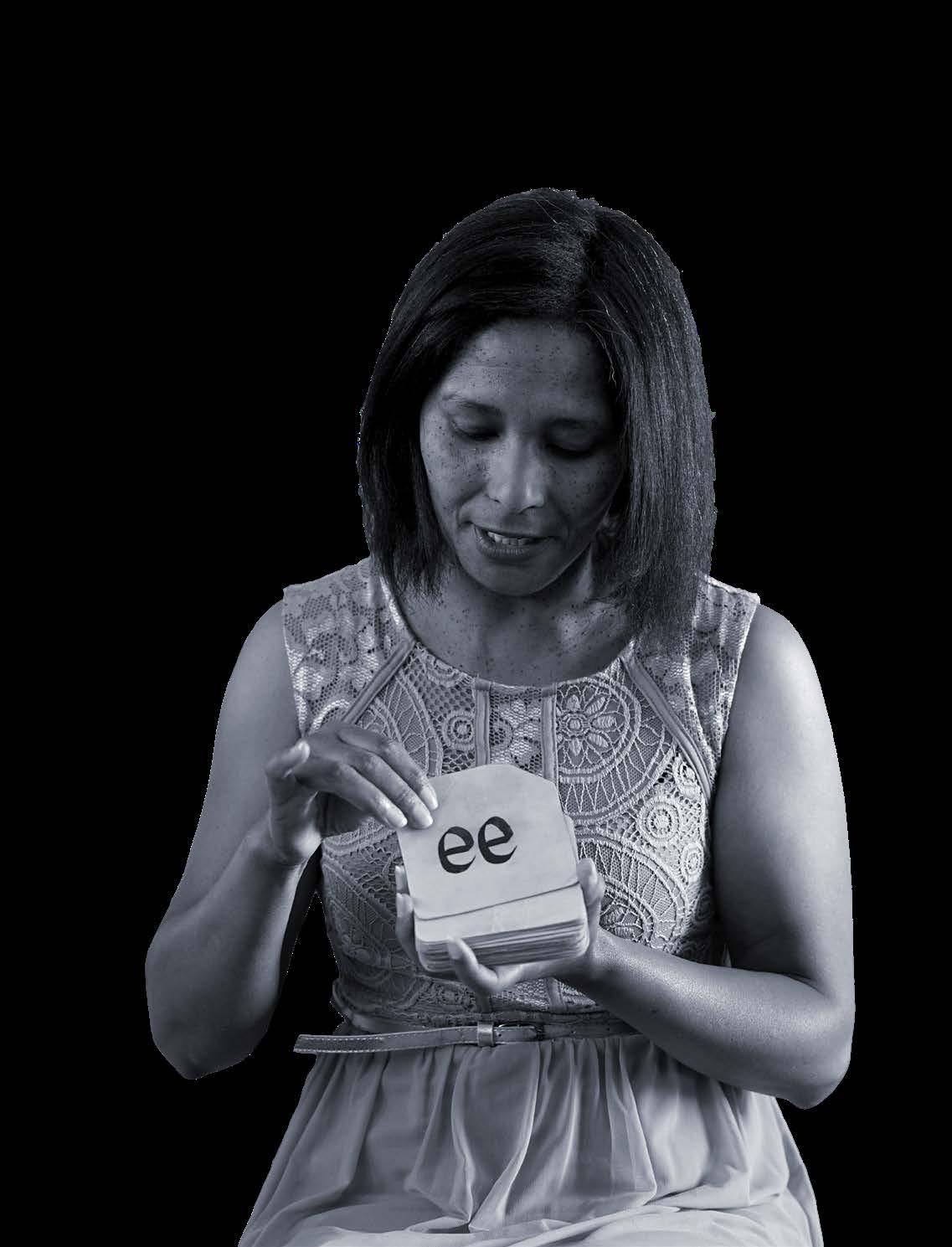

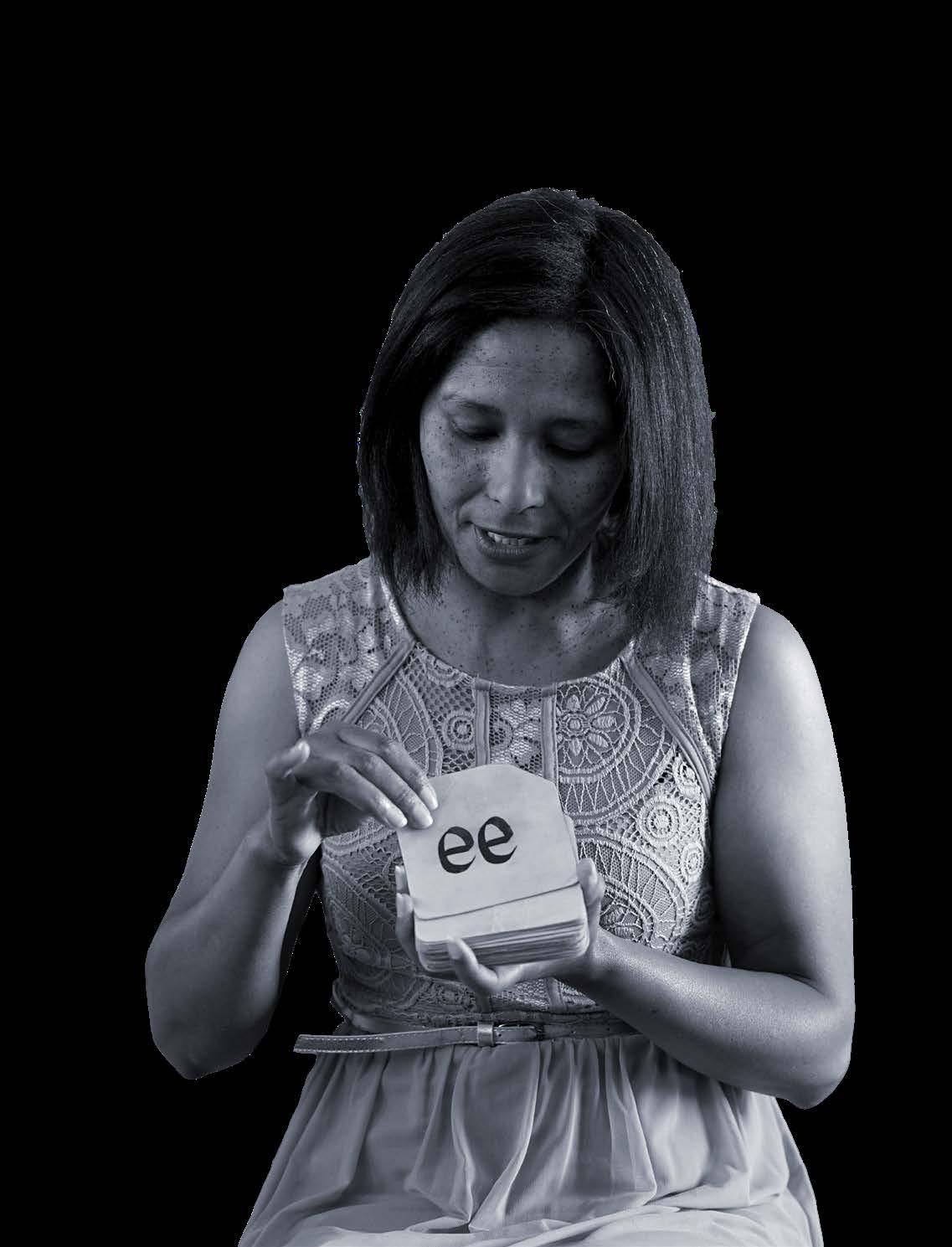

Reading for Meaning7 (a programme of the Zero Dropout Campaign8) focuses on Grade 5 learners; and Acorn Education9 (in collaboration with Public School Partnerships10) implements a reading intervention to help Grade 7 learners transition into high school.

These projects seek to change the trajectory of learners who have fallen behind so they are better positioned to keep their grip on opportunity.

ADDRESSING GAPS IN FOUNDATIONAL LITERACY SKILLS

Pumza Ndamase, Project Lead for Reading for Meaning, says a learner’s poor academic performance is an indicator that they are likely to drop out of school. About 40% of learners drop out of school before completing matric, and the Zero Dropout Campaign is working toward halving this rate by 2030. Weak foundational literacy is a major reason why learners struggle academically and may have to repeat a year or more.

It is important to note that there is no guarantee that repeating a year will improve reading skills if the necessary support and resources are not available for struggling learners.

Often these learners become demotivated and disengaged from schooling, eventually dropping out of school. The Reading for Meaning programme is part of the campaign’s strategy to address poor academic performance at an early stage so learners can gain the foundational literacy and numeracy skills they need to stay motivated and on track to complete their schooling.

Reading for Meaning aims to help learners who are struggling to keep up with their peers. It uses the internationally recognised Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) methodology, which focuses on a child’s learning needs rather than their age or grade to support learners who missed key literacy and numeracy concepts early in the foundation phase of their learning journey. The programme runs after-school sessions with Grade 5 learners in low-resource

5 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR GRIP ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022 10

“If a child leaves the foundation phase without being able to read, they step into the vicious cycle because they are constantly trying to catch up and they are limited in terms of what they can learn. If they can read, they step into the virtuous cycle, because they are unlimited in terms of what they can read and learn.”

Celeste Abrahams, Acorn Education Instructional Coach

> >

6 Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP) in South Africa was reported at 6.1929 % in 2020, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators, compiled from officially recognised sources. 7 https://zerodropout.co.za/reading-for-meaning/ 8 https://zerodropout.co.za/ 9 https://acorneducation.org.za/ 10 https://dgmt.co.za/publicschoolpartnerships/

communities in the Eastern Cape, Western Cape and KwaZuluNatal by training community volunteers, known as Reader Leaders, to facilitate 30 sessions over 16 weeks.

Learners are divided into four different groups depending on their reading ability (whether they are able to recognise letters, words, or read sentences with comprehension). Throughout the 16-week programme, learners in the programme are regularly assessed to determine whether they can move to the next level. Reader Leaders teach in English, translating into a learner’s mother tongue if necessary. Currently, there is a bilingual pilot (in terms of teaching, workbooks and resources) in English and IsiZulu in KwaZulu-Natal. The programme aims to add another home language each year, depending on the province.

PROGRAMME FINDINGS:

In 2021, the Reading for Meaning programme began with 35% of learners at letter and word level. At the end of the programme cycle, more than 70% of learners were able to read at paragraph level, which is an indication of their ability to read for meaning. So far, the programme has reached more than 2 000 learners.

ABUKWE’S STORY

*Abukwe is a 12-year-old boy who was raised at a place of safety for a year until his paternal grandmother decided to take him and look after him. He now lives in Parkside in East London with his father, little brother and grandmother.

He attends *Willow Primary and is repeating Grade 5 because his teachers say that he cannot read and write. He was referred by his class teacher, *Mrs Martins, to an educational psychologist because he was not coping with schoolwork, and it was suggested by some in his school that he may need to attend a special learning institution to cater to his needs. His grandmother refused to send him to another school and insisted that all he needed was someone who could understand him and help him learn at his level.

While Abukwe was on the waiting list to be assessed by a psychologist, the Reading for Meaning programme was introduced at his school and he was selected to participate.

He did not miss a single session. Before he started the programme, his teachers described him as a playful child who did not take his schoolwork seriously. But things turned around when he started developing basic reading skills through the programme, received intentional supervision and one-on-one mentoring.

Mrs Martins says: “I saw a huge difference in Abukwe’s academic record as he managed to pass all his subjects and he is also able to do individual activities.”

Abukwe feels “happy” about his own progress. His favourite story in the Reading for Meaning programme is the Singing Sack because he loves the main song in the story.

*Names have been changed.

6 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR

GRIP

ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022 10

LEARNING GAPS WIDEN

OVER TIME

Learners who start high school without strong foundational literacy skills are at risk of constantly falling behind if the gaps in their learning are compounded and widen. Acorn Education, a non-profit company that supports no-fee schools in providing quality education, aims to ease this problem by targeting learners before they transition into high school. Acorn works in the community of Eerste River in the Western Cape – an area traditionally underserved and home to children impacted by poverty. Celeste Abrahams, Acorn Education Instructional Coach, says: “We’ve observed that many learners are not ready for high school in terms of their reading comprehension; they start Grade 8 with learning barriers that were initiated in primary school.”

The Acorn team found that although there are many highquality apps and interventions that schools can use to support learners academically, some of their reading levels are so low that they struggle to utilise these digital learning tools without programmatic support or mentoring. For example, Reflective Learning is a maths app that has shown positive results11 However, Acorn coaches have seen learners struggle to work on the maths app, not because they can’t do maths, but because they can’t read the explanations and instructions. In August 2021, Acorn Education and Apex High School piloted a reading intervention that focused on teaching learners how to read before they entered high school so they could advance academically once they got there.

The programme targeted the Grade 7 cohort of learners transitioning into Grade 8 at Apex High. The objective was to get them reading at Grade 6 level (as a minimum) and it ran for nine weeks. Students had the choice of instruction in English or Afrikaans, depending on their learning stream. The programme aimed at remediating specific gaps, and intentionally supporting learners in essential skill areas such as reading fluency, vocabulary, phonics, phonemic awareness and comprehension. These are foundational skills that, if not mastered, may cause learners to work persistently below their grade level. The effectiveness of this project was determined by comparing the results of a baseline test and a post-test.

ACORN EDUCATOR REPORTS BACK

PROGRAMME FINDINGS:

A total of 179 learners took the baseline test, which used Grade 6 reading-level texts as a yardstick. Before the project, only 53 were reading at Grade 6 level. A total of 126 were identified as “at risk”. Of these, 62 showed significant gaps in early literacy development and essentially struggled to decode basic words. These learners were identified independently as “seriously at risk” and were provided with reading remediation in smaller groups, in addition to online interventions. Each learner who participated in the small group sessions was given a reading book to take home. For many of them it was the first time they had owned a book.

After the nine-week programme, the 126 learners who were “at risk” or “seriously at risk” were invited to complete a similar Grade 6 reading assessment. The improvement was significant: 76 out of the 126 learners (60%) scored proficiently in the post-intervention Grade 6 assessment!

“My colleague and I were very excited to hand out books. The excitement soon turned into a mix of emotions when we observed some of the scholars’ responses. Firstly, all of them were surprised that they could keep the books. They doublechecked to find out if they could take them home. One of the boys, *James – I distinctly recall – smelled the pages of his book. I asked him why and he told me that it was the first time he owned a book that was not for schoolwork and also ‘new-new’. He told me his primary school didn’t have a library and his classroom only had textbooks.”

*Names have been changed.

7 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR GRIP ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022 10

11 https://reflectivelearning.co/case-study/a-winning-formula/7

learners were unable to complete the assessment and were expected to complete it at a later stage.

The 27 learners who are still either “At

or “Seriously at Risk” (most of whom are Afrikaans Higher Language) will continue to be

8 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR GRIP ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022 10 23

Risk”

supported. Source: Acorn Education PRE-GRADE 8 READING INTERVENTION BASELINE TEST vs. END-OF-INTERVENTION TEST [% of Answers Correct in Each Category] Comprehension Cognitive Levels Phonemic Awareness Literal 100% 100% 80% 80% 60% 60% 40% 40% 20% 20% 0% 0% General Literacy Skills 23 11 16 76 END-OF-INTERVENTION TEST Proficient At Risk Seriously At Risk Test Delayed Phonics Reorganisation Vocabulary Inference Spelling Evaluation and Application Baseline End-of-Intervention 46 42 31 58 39 27 44 36 69 92 78 85 66 72 68 78

WHAT CAN CIVIL SOCIETY LEARN FROM ACCELERATED LEARNING PROGRAMMES?

We can learn how to address the inequity in our schooling system from these initiatives. As Abrahams points out: “The impact is huge; this is the onset of bringing about educational reform in terms of equity… we know that learners who enjoy reading independently will have the door opened to knowledge, new interests and confidence.”

Acorn started by defining what a proficient reader is (learners who can negotiate the grade-level materials in a way that uses flexible thinking and allows them to make inferences beyond the text). Abrahams explains: “Be intentional about which skills need to be remediated and avoid teaching them in isolation or disconnected from the pupil’s current learning.”

Here are five main takeaways from the two projects discussed in this brief:

1 Have a clear goal

Decide what it is you want to achieve and how. Explore various methodologies and do the necessary research to ensure that they can work in the South African context. Identifying which achievement gaps to close can take many forms, but basically, the gap that Acorn was concerned with is the disparity in performance between what children are expected to have learned and what they had learned and mastered to date. To help identify the gaps,

Nurture relationships

It is important to nurture relationships with the different stakeholders involved in an accelerated learning programme. An essential element is to procure the buy-in of schools and caregivers so that the programme can access children in a safe environment while caregivers are able to support reading at home. In the pilot phase of the Reading for Meaning programme, the process of relationship building and securing buy-in stretched the time and resources of the programme’s core staff. It was only when implementing partners12 took on this role and responsibility that the process became easier as they already had established relationships with communities and schools. Implementing partners also enabled the programme to scale up and reach more children.

Acorn Education had an existing relationship with Apex High School, so the challenge there was around building relationships with a new cohort of children and parents. In the first three weeks, learner attendance was 80%, however it dwindled during the examination period, declining to 50% over the remainder of the programme. Regular communication with parents and learners’ primary schools allowed Acorn to contextualise the work they were doing, and this mitigated some of the attendance issues.

2 3

Focus on the learner

ALPs are meant to meet learners at their own level in small group settings. Abrahams maintains that it is still important to maintain rigour and encourage the learner to use their foundational skills. A learner-centric approach helps to accelerate learning in a short space of time.

Ndamase adds: “We encourage a positive learning environment where learners are able to use their voice, engage and ask questions, which is not often the case in many learning spaces. In many cases, their parents have noted not only a positive change in academic behaviour but also a boost in the child’s confidence.”

Implementing partners have also seen an increase in support from the schools in terms of assisting learners and integrating them back into the classroom.

9 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR GRIP ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022 10

12 Teenagers and Youth Health SA – KZN (eShowe), National Association of Child Care Workers (NACCW) – KZN, Social Change – EC (Mthatha), Lisebanzi Foundation –EC (East London), Masibumbane Development Organisation – EC (East London).

Reading for Meaning adopted the TaRL methodology because it showed results in other developing countries, is cost-effective in terms of resources and relatively easy to implement. Additionally, trainers do not need to have a teaching qualification. Implementing partners train and mentor volunteers who are unemployed young people, able to read and enthusiastic about sharing this skill.

Flexibility is also an integral requirement. Part of the Acorn intervention was to create a buddy reading segment, where learners partner with someone and take turns reading the same book for enjoyment. Acorn needed to procure Hi/Lo reading books for this activity (Hi/Lo refers to books that have a high interest level and a low vocabulary or readability level). Contrary to popular belief, it was a challenge to find suitable books for this group due to availability. To supplement the books, Acorn ended up creating reading materials or editing complicated passages to fit the criteria.

THE PATH AHEAD

The success of Acorn’s pre-Grade 8 learning intervention was such that the school governing body has now amended its admissions policy to state that completion of the assessments and participation in the programmes are mandatory for admission to the school. Both Acorn and Reading for Meaning are currently testing numeracy ALPs for roll-out in the future.

“We are at a critical point that requires investment from all parties: private sector, civil society and government. Government departments must put forward policies that further reform,” says Ndamase.

Abrahams agrees that education reform does not lie at the door of government. Civil society organisations can assist by pooling their resources toward levelling the academic playing field.

If we are not able to turn this around, especially after all the learning losses from COVID-19, it is going to have severe repercussions for South Africa. We must provide accessible, sustainable, effective programmes that help learners catch up and perform better so they can benefit from the education they deserve. And we must do it now.

Health issues may be the real barrier

Acorn ensured that all learners went for health screenings to check their vision, hearing and other general health concerns. Often there are non-scholastic problems that interfere with a learner’s ability to learn. The screenings help detect these problems, which are often subtle and go unnoticed for years.

During 2021, 348 learners in Acorn programmes were screened for potential learning barriers, with 40% referred for medical attention.

“It is not beyond our power to create a world in which all children have access to a good education. Those who do not believe this have small imaginations.”

Nelson Mandela

This is the learning experience of:

10 SUPPORT YOUNG PEOPLE TO KEEP THEIR GRIP ON OPPORTUNITY SEPTEMBER 2022 10

WWW.DGMT.CO.ZA

Learning brief developed by Daniella Horwitz with contributions from Reading for Meaning and Acorn Education.

5

4Programmes should be cost-effective, user-friendly and adaptable

OPPORTUNITY

HANDS-ON Experience Learning

Ilifa Labantwana’s COVID-19 Response

4Give every child the benefit of early childhood development

THINK, PLAN, ACT AND ADAPT!

Ilifa Labantwana’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic provides important lessons for civil society on how to respond to increased demand for social services from low-resource communities in rural and semi-urban areas.

From the onset of South Africa’s hard lockdown in March 2020, it was clear the government would not be able to address the humanitarian challenges associated with the pandemic on its own. Civil society groups partnered with one another, funders and government, trying to mitigate the loss of income, increasing hunger and lack of access to personal protective equipment (PPE). The early childhood development (ECD) sector – which is largely informal and dominated by women –was particularly vulnerable because it mainly consists of microsubsistence-based enterprises generating an income for the women who run them and their staff.

Disruptions to ECD programmes impede the ability of mothers to take up income-earning opportunities because they tend to shoulder the burden of childcare.

At the height of the pandemic, thousands of ECD sites were forced to close and livelihoods were threatened. Unregistered ECD programmes, and the women who run them, were most at risk. Millions of children faced hunger and the loss of essential ECD services such as early learning and nutrition programmes. Civil society rallied in response and documented the impact of the pandemic on the sector with an April 2020 report, The Plight of the ECD Workforce

It’s important to note that registration is a complex process that requires approval from several government departments and certain resources, and as such is beyond the reach of most informal ECD practitioners.

Ilifa Labantwana is committed to quality ECD for all children. Over the years, it has worked with the government and a range of implementing partners to demonstrate effective delivery mechanisms for a suite of quality, age-appropriate early childhood development programmes.

Ilifa spearheaded an ambitious response that brought urgent relief to the ECD sector at a time when it was most needed. It mobilised resources and partnerships, raised R36-million in funds and launched the Early Childhood Development COVID-19 Response Project in September 2020.

It had two major objectives:

to help unregistered South African ECD programmes withstand the pressure of the pandemic and meet stringent government COVID-19 protocols to re-open; and to see if ECD sites serving poor children could be used as nodes for delivering nutrition interventions, using electronic vouchers.

11 GIVE EVERY CHILD THE BENEFIT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT SEPTEMBER 2022

1 2

Time was of the essence. Given the limited timeframe to initiate such a relatively wide-scale project, Ilifa built its response on available data from a rapid survey of ECD practitioners in April 2020. The planning phase involved fundraising and due diligence on proposed aspects of the project. Ilifa also engaged a range of ECD stakeholders by co-designing the project with funders and potential partners, and contracted three NGOs to implement the project’s activities with their own cohort of ECD sites, staff and children. These implementing partners were: SmartStart, The Unlimited Child and Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading (VPUU).

In total, the project helped more than 1 700 unregistered ECD sites to re-open by November 2020. It ensured about 30 000 children received regular, healthy meals over a period of 18 weeks and provided income support to almost 3 500 ECD workers. By March 2021, almost all the project sites had fully reopened, most of the children had returned and an encouraging proportion of parents had recommenced paying fees.

This learning brief explores the decisions and factors that enabled and constrained Ilifa’s response to the pandemic so that civil society organisations can learn from the experience and adapt aspects of the response to their own work.

HIGH-LEVEL TAKEAWAYS

This was a complex project to get off the ground, with challenges and lessons for the Ilifa management team and implementing partners. Ever-changing COVID-19 regulations added another layer of complexity, constantly challenging field operations. Nevertheless, Ilifa managed to achieve most of its objectives and the following high-level takeaways can prove useful to civil society.

Strong project management required

When conducting a large and ambitious project in a humanitarian crisis, with a sizeable budget and various implementing partners in different provinces, strong and ongoing project management is required.

Ilifa put together a project management team to: coordinate all activities with implementing partners; manage problems and issues as they arose; drive the monitoring, evaluation and learning aspects of the project; and report to funders.

Careful research is essential

Ilifa demonstrated that even in times of crises, when there is urgent pressure to respond, it is essential to obtain information directly from the intended beneficiaries to provide an effective response. The rapid survey conducted by Ilifa and other organisations in April 2020 found that, of the 8 500 ECD programmes that were contacted, nearly all of them said caregivers had stopped paying fees; 83% had not been able to pay their staff’s salaries over the lockdown period; 96% said that their income could not cover their operating costs; and 68% were worried they would not be able to reopen after lockdown.

Four months later in August 2020, the widely reported NIDS-CRAM Wave 2 study1 confirmed the validity of the initial survey, reporting that ECD attendance dropped to an 18-year low of just 13%.

The findings from the research enabled Ilifa to design a comprehensive project approach with key interventions necessary to provide the following basic support to selected ECD sites:

COVID-19 compliance materials (containing all required cleaning and hygiene materials) and other compliance support such as reliable water access and water storage capacity needed to be made available.

CoCare vouchers were issued via SMS to ECD site managers – to be redeemed for food for the children –and to ECD staff, providing them with income support.

Ilifa provided a guideline document that recommended 10 food purchases that were affordable and would promote physical and cognitive development in children.

HOW THE COCARE VOUCHER SYSTEM WORKS

Flash (the retail technology service provider) sends an SMS to the mobile phones of verified beneficiaries. This notifies recipients that they have received a CoCare voucher. It provides the amount of the voucher, the expiry date and a voucher PIN. Beneficiaries take this PIN to their nearest Flash/Kazang vendor and may purchase essential items to the value of the voucher. The beneficiary may redeem the whole amount in one shop, or partially redeem it, in which case the system automatically sends a new PIN for the balance of the voucher.

12 GIVE

EVERY CHILD THE BENEFIT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD

DEVELOPMENT SEPTEMBER 2022 4

1 2

> > > > > > >

1 Wills, G., Kotze, J., Kika-Mistry, J. (2020) A Sector Hanging in the Balance: ECD and Lockdown in South Africa

Harness existing capacity of NGOs

Ilifa worked with NGOs and leveraged their existing local capacity, relationships and networks with ECD programmes to ensure the success of the project. It would not have been possible for the project to have wide-scale reach if the implementing partners were not already operating in the ECD space. NGOs with large footprints (i.e. across multiple provinces) should work with local organisations to maximise local-level relationships, communitybased and regional knowledge systems, and stakeholder buy-in. However, it is important to note that partners may need additional support as their resources will be stretched by the crisis. Depending on the scale of the effort, NGOs may need more support and capacity at all levels (field, office and management personnel) and areas (such as technical capacity, monitoring systems and management tools) to provide an expanded range of services.

Appropriate ECD sites and ECD staff had to be identified and verified by NGO partners. They were able to identify and validate unregistered ECD sites using their existing databases and networks. Where organisations did not have an existing network, the implementing partners conducted a manual audit of ECD sites in the community and consulted bodies such as ECD forums. The partners demonstrated that NGOs can effectively identify and confirm the validity of ECD sites and staff through a variety of approaches, which include speaking to community leaders and residents to verify that the site had been operational and serving the community prior to the onset of the pandemic, the collection of staff payslips, bank statements or affidavits.

Given the complexities and risks associated with disseminating funds, Ilifa learnt through implementation experience that voucher PINs must be secure and only accessible to the ultimate beneficiary to avoid them being redeemed by individuals who are not the intended recipients. In fact, in one instance, such fraud happened during the project and was flagged when the retail technology service provider identified that a number of vouchers were redeemed on one particular device in a short time period.

Civil society is not immune to the misuse of resources. It’s something that the sector must continually work to strengthen by learning from mistakes and carefully considering the controls that should be put into place.

Inaccurate data hampers delivery

The project targeted unregistered ECD sites in low-resource communities because they were most in need of support and least likely to obtain government assistance. The reality is that many of these sites do not have a computer, let alone accurate databases recording the number of school children attending on weekly or part-time bases or the number of full-time or parttime staff. This meant that implementing partners often had to gather all this information from scratch and this took a long time, impacting the number of beneficiary requests that could be submitted before the deadline2 .

In times of crises, when government departments reallocate resources for emergency expenditure without rigorous oversight and accountability measures, the conditions are ripe for corruption, maladministration, and malfeasance. That is why verification and security are so important – to ensure the correct resources reach the intended recipients in a timeous fashion.

A water-needs assessment tool was carefully designed to determine the water requirements of each site. Implementation partners managed to conduct this assessment at the majority of sites, despite the tight timeframes. However, when Ilifa received the data electronically, the site location data was unclear. Field monitors had provided names of ECD sites, names of site owners, and a general idea of location, but there was otherwise no specific geospatial data on the exact location of the sites. The service provider worked with partners to try to identify as many sites as possible by calling site managers and scoping the areas themselves. But in the end, some sites missed out because of ambiguous data.

In this type of work, it’s important to compile databases that include unique identifiers, good geospatial data and up-to-date contact information for ECD site staff.

13 GIVE EVERY CHILD THE BENEFIT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT SEPTEMBER 2022 4

Strong systems prevent misuse of resources

3 4 5

2 The humanitarian crisis facing the ECD sector and children in project communities influenced these urgent timelines.

Data challenges during a crisis can be ameliorated if accurate and up-to-date records are gathered on an ongoing basis and kept in a format which can be easily shared. ECD programme managers should also be trained and encouraged to use simple electronic tools such as Google Forms, which they can complete and submit regularly, keeping accurate records of all staff, records of payment, employment contracts, etc.

Innovative payment systems such as digital vouchers can work to channel government or private sector funding to selected beneficiaries through verified sites. Ideally, digital vouchers must be easy to operate and user-friendly to minimise the amount of support needed by beneficiaries to receive and redeem the vouchers at a large scale.

Ongoing monitoring6 7

Ensure delivery systems are user-friendly

The voucher programme was a core activity in the project that took up most of the budget and capacity of all project partners. Although the voucher system worked for most of the beneficiaries, who received their vouchers and were able to use them, there were some challenges where 15% of beneficiaries did not receive their vouchers. These challenges included cellphone network problems; lost or stolen phones and vouchers being deleted or misplaced. Some of these individuals needed their voucher PINs resent, and others needed their numbers changed because the number provided had been incorrect.

Those working on the project had to process these requests manually so it became necessary to invest more resources in the voucher system in response to the day-to-day challenges that arose in the early stages of implementation.

Any voucher system designed for urgent social relief must be able to handle complexity. Although high-tech solutions tend to be more secure, they can be too complex for beneficiaries to use. The implementing partners tried to address this issue by providing on-the-ground support through field workers, but pandemic social distancing regulations meant this was not always possible.

POSITIVE OUTCOME: INCREASED DIGITAL AND FINANCIAL LITERACY

The voucher programme pushed many of the recipients to use their phones and technology on a higher level than before. For many ECD site managers, the practice of receiving a voucher on their phone and redeeming it at a spaza shop made them more familiar with digital transactions – a skill that would place them in good stead as the financial services sector becomes increasingly digital.

Monitoring and evaluation were fundamental to ensure that the funds were spent and the support had the desired impact on ECD sites, staff and children, but also to learn vital lessons to strengthen the sector.

The project was implemented during the peak of the second wave of COVID-19 which caused major concerns and disruptions in the country. This made field visits difficult. The field monitors could not travel around as freely or safely as was planned, which impacted their ability to quickly conduct all their site visits.

Alternative, flexible means of monitoring and supporting sites can be put in place by using social media and technology. Using local forums can also improve field capacity.

Sites in urban areas are easy for partners’ field monitors to visit frequently, but in large rural provinces this is harder to do because of geographical distances. Therefore, in some areas, NGOs may require additional human capacity, such as volunteers to provide an expanded range of support and monitoring.

14 GIVE EVERY

CHILD THE BENEFIT OF EARLY

CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT SEPTEMBER 2022 4

PROPOSALS

FOR THE FUTURE

Often the biggest hurdle during a crisis is the effective distribution of resources. Below are four proposals that can help to ensure this occurs.

Ensure stronger information systems

Strong systems for gathering, storing and making available up-to-date and accurate information are needed to support voucher or payment systems at a systemic level.

NECESSARY SCAFFOLDING

This learning brief provides an illustration of how an underresourced, largely informal sector made up of microsubsistencebased enterprises, was provided with the resources and support necessary to withstand a crisis. However, it is important to note that if any sector is to be able to act on the lessons learnt it will need to work in partnership with government and other stakeholders to ensure that the necessary scaffolding is in place.

This means considering the inequalities in access to banking and digital communication systems, and the circumstances and preferences of beneficiaries.

Consider connectivity

Payment systems need to take context into account in their design. Something as simple as geographic location can dramatically affect a person’s ability to cash in a voucher. Vouchers received via SMS work better in an urban context where connectivity is strong and there are more shops available.

Learning brief developed by Daniella Horwitz in conjunction with Ilifa Labantwana.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, South African NGOs proved to be crucial conduits of relief and support. When the state partners with experienced NGOs in a crisis, it can benefit from the systems and structures already in place, and reach more beneficiaries without incurring further logistical expenses.

This is the learning experience of:

15 GIVE EVERY CHILD THE BENEFIT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT SEPTEMBER 2022 4

Take beneficiaries’ lived realities into account

Government should partner with NGOs to ensure capability in a crisis

1 2 3 4

WWW.DGMT.CO.ZA

6Make sure every child is ready to read by the time they go to school

HANDS-ON Experience Learning

Building Stronger Learning Foundations

PROACTIVE INTERVENTIONS TO BUILD STRONGER LEARNING FOUNDATIONS

One of South Africa’s biggest developmental challenges is the large proportion of children who cannot read for meaning in early grades1. Reading with comprehension is a fundamental skill upon which others are built. Children who do not have strong learning foundations are not equipped to read for meaning and, without adequate support, they struggle to reach their potential with long-term social- and economic consequences for the country. We can’t rely on schools alone to fix the country’s literacy problem as causal factors occur before children enter primary school.

It is well known that South Africa has a literacy crisis, with most Grade 4 children unable to read for meaning in any language2 Fortunately, the government has started to make reading a key developmental priority. President Cyril Ramaphosa often cites reading for meaning in his State of the Nation Address (SONA), envisaging that in the next 10 years “every 10-year-old will be able to read for meaning”3. As part of the government’s efforts to improve literacy levels and education outcomes in the public schooling system, the Department of Basic Education

(DBE) initiated the Early Grade Reading Study (EGRS) to better understand the literacy challenge and find ways of addressing it in collaboration with academics from the University of the Witwatersrand, Georgetown University and the Human Sciences Research Council4

These studies are generating evidence around what sort of interventions influence reading outcomes in the primary school years.

1 78% of South African Grade 4 children cannot read for meaning in any language. Source: https://nicspaull.com/2017/12/05/the-unfolding-reading-crisis-thenew-pirls-2016-results/

2 https://nicspaull.files.wordpress.com/2017/12/p16-pirls-internationalresults-in-reading.pdf

3 https://resep.sun.ac.za/reading-for-meaning-a-common-issue-inpresidents-sona-speech-and-reseps-binding-constraints-report/sample-post/

4 https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/EGRS%20 Policy%20Summary%20Report.pdf?ver=2017-08-15-092224-000

MAKE SURE EVERY CHILD IS READY TO READ BY THE TIME THEY GO TO SCHOOL

16

SEPTEMBER 2022

OPPORTUNITY

Early Grade Reading Studies

The Early Grade Reading Study (EGRS)5 evaluated three Setswana Home Language interventions aimed at improving reading in early grades: a teacher training intervention, an on-site training and coaching intervention and a parental involvement intervention.

These three interventions were implemented with the teachers of a cohort of learners in Grade 1 in 2015, the teachers of the same cohort of learners in Grade 2 in 2016 and the first two interventions were extended to the teachers of the same learners in Grade 3 in 2017.

RESULTS:

The results show evidence of a sustained impact from the coaching intervention on several Setswana (home language) outcomes. Although there was a significant average impact for all learners in the coaching intervention on only one of the Setswana oral reading passages, the most consistent impacts were for learners who received the maximum “dosage” of the EGRS I intervention in Grades 1 to 3 (i.e. those who progressed, as intended, through the three years of the intervention from 2015 to 2018).

Significant impacts were found for these learners on four of the seven Setswana reading outcomes (with marginally significant impacts on the rest). This provides evidence that results from an early grade reading intervention can be sustained into upper grades but also points to the importance of frequency or “dosage”.

Interestingly, the coaching intervention also showed a statistically significant impact on retention, with a smaller proportion of learner attrition than the control group (38% versus 45%).

Overall, the results are very promising for the EGRS I coaching intervention, particularly because few other research studies have shown such a sustained, longterm impact of an early grade reading programme.

If proactive measures are not taken to ensure a child has the solid foundations of early learning, their academic progress will suffer, and this could lead to them constantly falling behind and dropping out of school. As children make their way through school, those lagging behind their peers may require remedial interventions, such as accelerated learning programmes in later school years.

This learning brief will explore innovative methods already used by several civil society organisations to promote early learning and reading. These are critical interventions to close learning gaps and improve educational outcomes (as the learning brief on Strengthening Links in the Learning Chain on page 4 demonstrates).

5 This report derives from the data collection and analysis for the Early Grade Reading Study (EGRS I), the Reading Support Project (RSP) and the Language Benchmarking study in two districts in North West, South Africa. This study was conducted for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Department of Basic Education (DBE).

ORGANISATIONS CHAMPIONING PROACTIVE INTERVENTIONS

Proactive interventions can help to critically address weak learning foundations. The fact is that the foundational building blocks for reading happen before a child enters primary school. The first five years of life lay the groundwork for a child’s lifelong development. This is the time when children learn to learn6 Many studies have found a strong positive link between the language skills that children demonstrate in their preschool years, and their ability to learn later on in school. The early language development that occurs through storytelling and reading builds pathways to understanding and expression as the central currency for human interaction. When it occurs in a loving relationship – between a parent and child for example – it creates positive associations that promote empathy and the curiosity and imagination that underpin lifelong learning and innovation.

Unfortunately, the early childhood development (ECD) sector is not well-supported by the government. According to Ilifa Labantwana, a programme seeking to ensure all children get access to quality ECD, only 20% of the seven million children who need subsidised early learning are receiving it7

Civil society can address this deficit by increasing access to early learning programmes (ELPs) for children. Several South African NGOs have been pioneering interventions to create effective community platforms for early learning and reading.

These organisations include: Wordworks, an NGO that focuses on early language and literacy development.

Mikhulu Child Development Trust, an NGO that promotes parents and caregivers as their children’s first and best teachers.

Nal’ibali, the national reading for enjoyment campaign. Nal’ibali has drawn on both Wordworks and Mikhulu for training and resources.

SmartStart is a social franchise that aims to expand access to quality early learning in South Africa for three- to five-year-old children.

Three things stand out in all of these interventions: reading needs to be encouraged from a young age and parental involvement is imperative. These resources must also be accessible.

6 https://dgmt.co.za/early-learning-the-great-equalizer-for-south-africa/ 7 https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-08-22-women-led-ecd-sectorstill-receives-a-tiny-slice-of-the-budget-pie/

17 MAKE SURE EVERY CHILD IS READY TO READ BY THE TIME THEY GO TO SCHOOL SEPTEMBER 2022 6

ARRIVE READY TO LEARN

Katie Huston, Chief Operating Officer of Nal’ibali, the national reading for enjoyment campaign, says that when we think of reading as a skill mainly developed in the classroom, we limit children’s potential and disempower the adults who love them.

Regardless of what kind of interventions are introduced to schools, children who arrive at school ready to learn are going to learn to read better than those who are not.

Huston expands: “You want kids to arrive with this massive vocabulary and large body of general knowledge and the alphabetic principle of knowing that a letter stands for a sound, even if they don’t know all the letters or sounds yet.”

According to international research8, children who are read one book a day will hear 290 000 more words by age five than children who are not read to.

In 2022, Nal’ibali refocused its strategy to invest more in parental involvement. During its high-profile annual campaign for World Read Aloud Day, which draws attention to the importance of reading aloud to children in their mother tongue, Nal’ibali invited more families to pledge. The rationale behind this initiative is that if families get into the habit of reading together, such practices may result in sustained behaviour change with regards to reading at home.

Currently, Nal’ibali is piloting a programme in particular communities in the Northern Cape and Free State. The team arranged parent workshops and home visits based on Wordworks’ Every Word Counts programme for parents and caregivers of young children, integrated into the Nal’ibali model of ECD centre visits, community activations, “tuk-tuk” libraries (see box below), reading clubs and reading club training.

A particularly interesting aspect of this pilot is that although Nal’ibali is deploying the same carefully designed and structured programme in these geographical regions, they have landed differently. In one community there is significant uptake, regular attendance by parents and strong engagement. In the other community, campaigners are struggling to get parents to attend meetings or make return visits.

This highlights the fact that the unique circumstance of an area will affect the impact of an intervention.

WHAT ARE TUK-TUK LIBRARIES?

“If families try reading together, they will experience short-term, immediate benefits – observing their children’s curiosity and interest, enjoying closeness and together time – which can support families to adopt these habits more long-term.

Katie Huston, COO, Nal’ibali

Nal’ibali takes a collaborative approach to activating parental participation and reached out to other organisations that have experience in this field. Huston explains: “The Nal’ibali team is skilled in training ECD practitioners, community volunteers or teachers to run reading clubs for older kids. But we needed to better understand how to encourage parents to engage with young children.”

As an approach to upskilling staff, Nal’ibali collaborated with Wordworks, an NGO that focuses on early language and literacy development, and Mikhulu Child Development Trust, an NGO that promotes parents and caregivers as their children’s first and best teachers. These organisations trained the Nal’ibali team in their methodologies and provided access to their materials.

Tuk-tuk libraries are housed in three-wheeled motor vehicles, loaded with books, stories and other reading material. The logistics, safety concerns, fleet management challenges, etc. of driving the tuk-tuks proved an unviable and extremely costly model after two years of testing. Though they are now stationary, the tuk-tuk libraries provided access to library material while municipal libraries were closed for an extended period during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. They offer a visible space for literacy activities and activations. They are stocked with children’s books in local languages.

Many parents or caregivers may not feel confident in the role of educator. This may be because they were not able to complete school themselves or because the turbulent and unequal history of education in South Africa means they may associate schooling with trauma.

SmartStart is a social franchise that aims to expand access to quality early learning for three- to five-year-old children. It has a network of more than 7 000 practitioners, or SmartStarters, working across South Africa, in rural and urban areas, running early learning programmes for children. As part of this work, SmartStarters are supported to include story-sharing daily in their programme with children, to encourage a love of reading and the development of pre-literacy skills. Additionally, SmartStarters are equipped and encouraged to support primary caregivers to continue this learning and the development of early reading skills at home.

18 MAKE SURE EVERY CHILD IS READY TO READ BY THE TIME THEY GO TO SCHOOL SEPTEMBER 2022 6

8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30908424/

Kirsty Paxton, SmartStart’s Early Learning and Design Manager, says: “Often parents don’t realise the value of storytelling or just talking with their child. Probably a huge part of it is the culture of education in this country and the idea that education is something that happens only at school, particularly in a formal school setting.”

Wordworks partners with NGOs such as Nal’ibali that integrate their programmes into home visits and community work with schools and centres, where teachers run workshops for parents. Jane Coombe, Head of Programmes at Wordworks, says their team has worked for nearly 20 years to change parents’ perception of their role and to share simple activities for them to try at home.

“Our school system alone isn’t able to compensate for five years without learning stimulation and exposure to rich language stimulation. Our Every Word Counts programme and ‘parent programmes’ were developed to build parents’ confidence to facilitate informal language learning at home.”

PARENTS AS LEARNING PARTNERS

During the COVID-19 pandemic, more teachers recognised parents as learning partners, particularly with children too young to direct their own learning at home. In this context, Wordworks created a home learning programme, Together In My Education (TIME), endorsed by the Western Cape Education Department (WCED). Hard copy packs in English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa were sent home to 50 000 families during 2021 and again in 2022, providing fun, skills-based, daily activities for caregivers to do with their children.

The model was for materials to be managed by schools, so Wordworks provided Grade R and Grade 1 teachers with online sessions and access to multimedia messages that they could share with parents through a data-free website. Teachers were urged to set up WhatsApp groups and to hold meetings to support caregivers to guide the learning process at home.

Wordworks’ Every Word Counts programme can be used across a range of community settings to introduce knowledge about early learning to those who care for, and work with, babies and young children. It provides practical ideas for supporting the development of early language and literacy from birth to five years of age. Organisations can integrate the programme and resources into their work with parents and caregivers through home visits or parent groups. ECD practitioners and playgroup facilitators are encouraged to run a series of workshops for their parents.

The Home-School Partnerships programme builds co-operation between families and schools, while supporting and encouraging parents in their role as their children’s first teachers.

“Once parents understand the difference they can make, we have found they are almost always willing to try. Once they do, their experiences are overwhelmingly positive, often changing their relationship with their children in very profound ways,” says Coombe. But the challenge is finding scalable models to reach parents.

There is early evidence that the programme establishes a relationship of learning between the parent and the child, and a relationship of support between the teacher and parent. At an annual cost of R50 per family and with system buy-in, it has the potential to scale. Wordworks is conducting a longitudinal study to understand factors for successful uptake in homes, as well as the impact of the programme on children.

CHILD IS READY

READ

TIME THEY GO

19 MAKE SURE EVERY

TO

BY THE

TO SCHOOL SEPTEMBER 2022 6

“If we don’t intentionally engage with parents and caregivers, ECD practitioners, pre-Grade R and Grade R teachers so they can build strong oral language and emergent literacy skills, we are simply just landing the Grade 1 teachers with the same phenomenon year after year – children who are completely unfamiliar with what is being provided to them. They can’t yet hear the sounds in words, they don’t recognise that letters link to sounds, they don’t know that words in books contain meaning, or that they have the power to initiate text. They don’t have such tacit emergent literacy knowledge that makes it possible to make sense of and benefit from what the teacher is doing.”

Jane Coombe, Head of Programmes, Wordworks

Coombe explains: “So we are building an oral to written language connection in those two-week cycles, repeating the process with a new story focus each fortnight.”

The Wordworks Grade R programme has been taken to all public-school Grade R classrooms in the Western Cape and Gauteng. The open-source programme is now available in all South African languages.

BOOK-SHARING DEVELOPS RELATIONSHIPS AND LANGUAGE

Book-sharing is a two-way interaction between a parent and a young child between the ages of one to five using a wordless picture book.

“Research shows when a child is in a secure relationship with the parent they are better equipped to benefit from stimulation and actually develop better resilience,” says Kaathima Ebrahim, CEO of the Mikhulu Child Development Trust. This NGO focuses on developing evidence-based programmes for parents and caregivers of young children.

ORAL TO WRITTEN LANGUAGE

Coombe says that as part of her organisation’s contribution to quality education, Wordworks developed two classroom programmes designed to build strong oral home language and emergent literacy skills through playful, interactive, story-based activities.

These Wordworks classroom programmes, Stellar (Grade R) and Little Stars (pre-Grade R), take a body of language around a story and use it purposefully over two weeks of teaching. The same story has activities built around it, which bring the child into relationship with the story language (vocabulary and syntax), characters, context and themes. In the first week, all interaction is oral, and in the second week the child encounters text forms that also relate to the story. Children naturally learn that oral language can be represented in pictures and writing, in published books and in their own drawings.

Mikhulu researched different programmatic interventions that could best support a child’s early development in terms of cognitive and socio-emotional development and found that book-sharing had the most impact. In a randomised control trial of children aged 14 months, the language of those who participated in the book-sharing study, far outweighed those in the control group. It also improved concentration levels. Booksharing has also shown to improve the nature of the parentchild relationship, helping the parent engage with the child in a more sensitive and reciprocal way.

MAKE SURE EVERY CHILD IS READY TO READ BY THE TIME THEY GO TO SCHOOL

20

SEPTEMBER 2022 6

Ebrahim says: “A strong language foundation and the ability to sit and focus helps children learning to read.” Ebrahim shares that her organisation did not invent the technique of engaging children using wordless picture books, but turned it into a programmatic intervention relevant to the South African context.

The programme consists of eight weekly group sessions with a trained facilitator for parents. Each parent can practise what they have learnt in the session and is given a resource to take home and use with their child.

IMPACT TAKES TIME

Ebrahim says a common request is for the programme to be conducted over one day. It is possible, but it will not have the same impact because this method has proven to be most effective working with families over several weeks. Mikhulu has developed instructional guides, because partners occasionally want to donate the picture books to parents but these parents do not know how to use them.

Mikhulu capacitates community-based organisations or government partners to use their book-sharing programme. During the pandemic, when this was not possible, Mikhulu developed a series of video resources to help parents learn about book-sharing. It is currently working with the Western Cape Department of Health to train community health workers to bring book-sharing and early stimulation into homes.

Advantages of book-sharing:

can be done in any language; parent does not have to be literate; community workers are trained to support parents; builds a stronger parent-child relationship; and lays the foundations for lifelong learning.

STIMULATING A LOVE OF READING

SmartStart also employs other methods to promote a love of reading. The daily routine for SmartStarters includes half an hour for sharing stories, and group activities often link to the stories.

SmartStart has long recognised the pivotal role of parents and caregivers in learning. Paxton says: “Parents and caregivers are so important. The how of involving them can sometimes be challenging.” Since SmartStart’s previous approach of monthly meetings did not have the desired uptake, it is now implementing four family fun days a year:

SmartStart also advocates book-sharing with wordless picture books. Ten picture stories, each printed onto a single A4 page folded up into a booklet, have recently been added to the SmartStart curriculum. The booklet is sent home with children, together with an activity sheet (translated into 11 languages) to support caregivers at home and stimulate the joy of reading.

The additional resource promotes learning interaction between parent and child and increases SmartStarters’ value in the eyes of the parents. As the stories are wordless, this supports families with low literacy levels too.

an open day welcoming parents and caregivers at the start of the year; a play day promoting the importance of learning through play in the home; a story day promoting the importance of families sharing stories in the home; and an end-of-year celebration or “graduation”.

SmartStarters are encouraged to build relationships with parents by meeting with them regularly, communicating with them via WhatsApp groups and sharing progress reports twice a year.

21 MAKE SURE EVERY CHILD IS READY TO READ BY THE TIME THEY GO TO SCHOOL SEPTEMBER 2022 6

THE NEXT CHAPTER

As this learning brief has illustrated, schools cannot be solely responsible for preparing our children to read with understanding. Government, civil society, and communities have a role to play in laying the essential foundations of learning to ensure children will have the best chance of advancing to the next chapter.

This learning brief was developed by Daniella Horwitz in conjunction with Nal’ibali, Wordworks, SmartStart and Mikhulu Child Development Trust.

About the contributors

Nal’ibali (isiXhosa for “here’s the story”) is a national reading-forenjoyment campaign targeting children between the ages of one and 10. It seeks to spark and embed a culture of reading across South Africa, so that reading, writing and sharing stories – in all South African languages – is part of everyday life. Nal’ibali maintains that children who read and hear engaging stories in languages they understand are well equipped and motivated to learn to read and write. Nal’ibali web and mobi sites are now zero-rated.

Wordworks is a South African non-profit organisation that focuses on early language and literacy development in the first eight years of children’s lives. Since 2005, it has worked in low-resource communities with those adults best positioned to impact on young children’s language and literacy development. Wordworks offers training, resources and support for partners who wish to use its early language and literacy programmes in their own networks. All its programmes include messaging about the importance of language for literacy development and the need to build children’s home language in the early years as a foundation for the acquisition of a second language. The Wordworks main site and home literacy sites are zero-rated.

SmartStart provides a pragmatic, affordable solution to rapidly expand access to quality early learning. The franchised programme is delivered through playgroups, day mothers and early childhood development (ECD) centre classrooms to improve children’s readiness for learning, school performance and overall life success.

By 2030, SmartStart aims to reach one million children between the ages of three and five every year.

Mikhulu Child Development Trust promotes parents as being their young children’s first and best teachers. The trust contributes to the development of a systemic approach where support for parents is part of a holistic ECD ecosystem, and they are supported to do the best for their young children.

MAKE SURE EVERY CHILD IS READY TO READ BY THE TIME THEY GO TO SCHOOL

22

SEPTEMBER 2022 6

WWW.DGMT.CO.ZA

Douglas Murray House 1 Wodin Rd Claremont 7700 PO Box 23893 Claremont 7735 +27 (0)21 670 9840 www.dgmt.co.za DGMT is a South African public innovator through strategic investment. Our goal for South Africa is a flourishing people, economy and society. Towards this end DGMT currently distributes about R180-million per year and leverages and manages a similar amount of funding through joint ventures with other investors.