HANDS-ON Experience Learning

Issue 24: June 2023

The legacy of Douglas and Eleanor Murray Invest in South Africa’s Potential

The legacy of Douglas and Eleanor Murray Invest in South Africa’s Potential

DGMT is a South African public innovator through strategic investment. Our goal for South Africa is a flourishing people, economy and society. Towards this end DGMT currently distributes about R200 million per year and leverages and manages a similar amount of funding through joint ventures with other investors.

Through the newly rebranded edition of our Hands-on Learning publication, we hope to play a helpful role in synthesising information from innovators and implementers in civil society, supporting them to share what they have learnt so that others are able to draw from and build on their experiences.

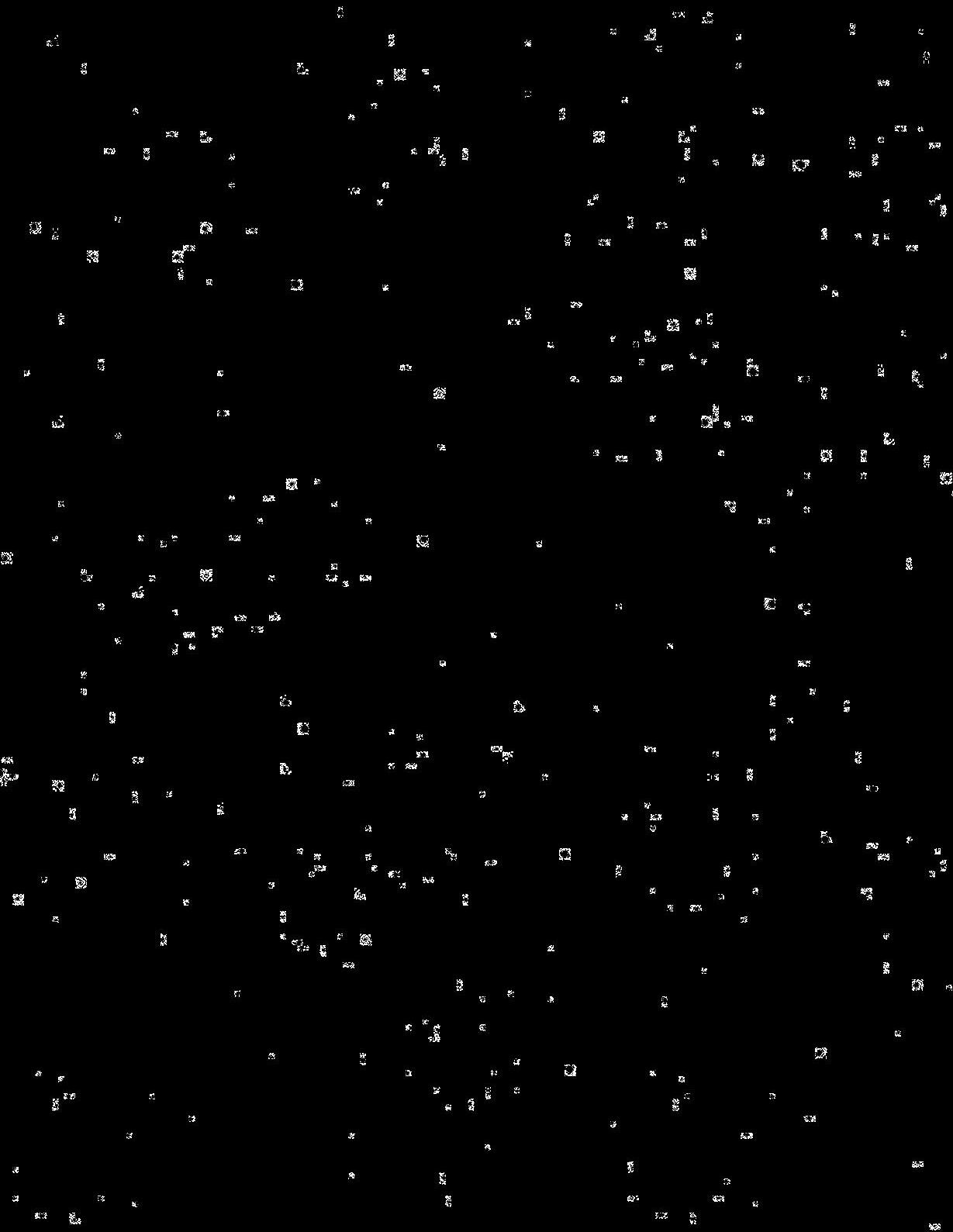

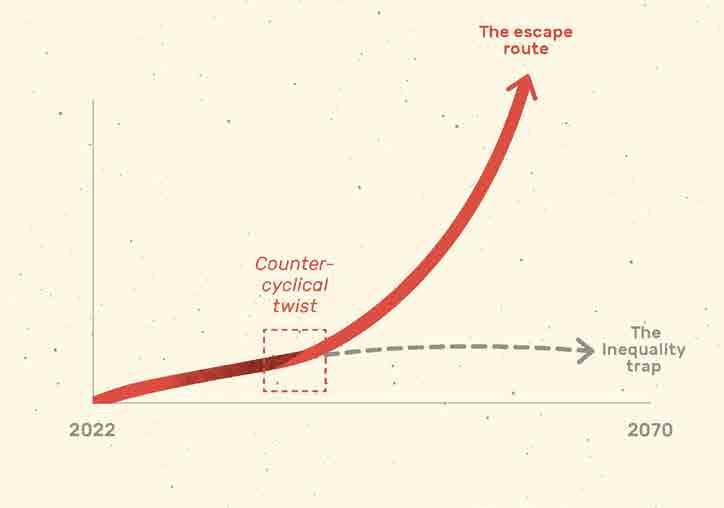

Have you read our 2023-2027 strategy titled Escaping the Inequality Trap?

To build a thriving society, more people must have the knowledge, skills and opportunity to participate fully in society and the economy, for the good of one another, and in synergy with the environment. To escape the inequality trap in South Africa we have set 3 goals. We then identified practical opportunities to realise each goal. This forms the guiding framework for everything we do.

We have identified 10 opportunities that constitute some of the most profound twists to enable South Africa to escape the inequality trap. This is because we can’t keep tracing the same old pathways to development in South Africa. We need bold and decisive twists that get us out of the rut, give fresh perspective and create new opportunities.

2023-2027 strategy available at: dgmt.co.za/our-approach

Our

Time National development

Twisting the nation's trajectory

IN THIS ISSUE WE FEATURE:

LEARNING BRIEF 1 Escaping The Inequality Trap: The Case For Supporting Pregnant Women

South Africa is stuck in an inequality trap with too few people able to build the knowledge and skills needed to fully participate in society and the economy. Our human capital pipeline is throttled at source, as high rates of low birth weight, stunting and inadequate access to early learning opportunities mean many children enter school with enduring learning deficits. They are likely to join the 300 000 learners that drop out of school annually; perpetuating inter-generational cycles of social and economic exclusion. Stop and think about it: we already know that, without a major change in the way we treat our children, many of the babies born in South Africa today have no chance of fulfilling their human potential!

This learning brief will show how, and why, improved support for pregnant women can help address malnutrition and stunting in the critical first 1 000 days of a child’s life, thereby changing a child’s development trajectory.

LEARNING BRIEF 2

Social Fathers: How Men Can Play A Greater Role In Caregiving And How This Impacts Our Children’s Future

The presence and support of nurturing and responsive caregivers helps children to reach their full potential. Although women have traditionally been seen as caregivers, adult men have an important role to play in the development of children as fathers, grandfathers, brothers, uncles, caregivers and Early Childhood Development (ECD) practitioners.

This brief explores how ECD practitioners and civil society organisations are challenging gender norms and changing perceptions about men in caregiving roles; helping to shape the lives of young people and refreshing attitudes about gender.

LEARNING BRIEF 3 Power, Access And Agency: Understanding Barriers To Parental Involvement

Parents are the first educators of their children. Their ability to know and love their children has unparalleled benefits. Research shows that encouragement and support from parents/caregivers, not necessarily assistance with specific homework, improves learner achievement even for children attending schools where the education offered is not of the highest quality. Although parents have untapped power – and rights – to hold schools accountable for quality standards, many feel they have little say in their children’s education for a number of complex reasons.

This learning brief looks at how three NGOs – Parent Power, Axium Education and Common Good – are driving parent engagement strategies in order to empower parents and fundamentally alter the educational trajectory of children in South Africa.

6 16 24

ESCAPING THE INEQUALITY TRAP: THE CASE FOR SUPPORTING PREGNANT WOMEN _

South Africa is stuck in an inequality trap with too few people able to build the knowledge and skills needed to fully participate in society and the economy. Our human capital pipeline is throttled at source, as high rates of low birth weight, stunting and inadequate access to early learning opportunities mean many children enter school with enduring learning deficits. They are likely to join the 300 0001 learners that drop out of school annually; perpetuating inter generational cycles of social and economic exclusion. Stop and think about it: we already know that, without a major change in the way we treat our children, many of the babies born in South Africa today have no chance of fulfilling their human potential!

This learning brief will show how, and why, improved support for pregnant women can help address malnutrition and stunting in the critical first 1 000 days of a child’s life, thereby changing a child’s development trajectory.

June 2023 | Issue 24 HANDS-ON Build simple, loving connections for every child OPPORTUNITY 7

Experience Learning

6 Issue 24 /// June 2023 ESCAPING THE INEQUALITY TRAP: THE CASE FOR SUPPORTING PREGNANT WOMEN

1 Van der Berg S., Wills G., Selkirk R., Adams C., Van Wyk C. 2019. The cost of repetition in South Africa. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series No. WP13/2019. https://www.ekon. sun.ac.za/wpapers/2019/wp132019

South Africa is the most unequal country in the world –80% of wealth is in the hands of 10% of the population and women earn 30% less than men with the same level of education.2 According to South Africa’s Living Conditions Survey, 52.2% of women fall below the upper-bound poverty line, compared with 46.1% of men.3 Additionally, research shows that 74.8% of women-led households fall below the upper-bound poverty line. Grow Great, a national campaign that seeks to galvanise South Africa towards a national commitment to zero stunting by 2030, says only a quarter of the approximately 1.2 million women who become pregnant annually have any source of income.

Stunting is a (largely preventable) condition where young children are short for their age and do not reach their full growth potential due to chronic nutritional deprivation, repeated infections and poor psycho-social stimulation. Stunting is associated with lifelong cognitive defects, educational and employment challenges, increased risk of chronic diseases in adulthood and cycles of inter-generational poverty.

2 Africanews with AFP. 2022. South Africa: The most unequal country in the world. Africanews, 10 March. https://www.africanews.com/2022/03/10/world-bank-southafrica-is-the-most-unequal-country-in-the-world//

3 Stats SA.2018. Men, Women and Children: Findings of the Living Conditions Survey 2014/15. Report 03-10-02. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=1854& PPN=Report-03-10-02

"Lack of access to socio-economic rights provides the clearest reflection of the levels of systemic poverty, unemploxyment, and inequality in South Africa and demonstrates the persistent recurrence of the cycle of poverty..."

South African Human Rights Commission, December 2018

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 7 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

As the cost of food continues to rise, poor households are paying more for less. This deepens food insecurity and places millions of children at risk of stunting. In order to reduce the cost of a carefully chosen basket of commodities by 30% and improve the diet of South Africa’s most underprivileged children, DGMT and its allies in a burgeoning nutrition coalition (including Grow Great) are urging the national government to join manufacturers and retailers, who waive their mark-ups on the 10 “best buy” foods for cash-constrained families, by matching the waivers.4

WHY DO PREGNANT WOMEN NEED SUPPORT?

A review published in The Lancet in 2013 found that maternal undernutrition accounts for about a fifth of all stunting.5 The 2022 provincial survey of child growth and stunting in the Western Cape found that babies who are born with a low birthweight are 2½ times more likely to have stunted growth.6 Typically, low birthweight is associated with undernutrition, maternal stress and other factors such as smoking and drinking alcohol. These interlocking factors are more prevalent in poorer communities, and threaten the well-being of pregnant women living in depressed socio-economic circumstances.

Poverty affects the nutritional status and mental well-being of pregnant women. These are factors that mutually reinforce each other7 and have a knock-on effect on foetal development, which in turn has a knock-on effect on early childhood outcomes (physical, cognitive and psychological).

Decades of structural inequality have concentrated disadvantage among poor, black women, reproducing cycles of racialised, gendered and class inequity. Despite policy and legislation aimed at expanding women’s economic participation, women remain less likely to be employed than men. When women do work, they are concentrated in low-skilled and less secure positions; earning lower wages for work of equal value (about 75% of what their male peers earn).8

According to the National Income Dynamics Study — Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), women experienced slower financial recovery than men as the economy reopened after the national lockdown. Of the women who were employed pre-Covid, only 47% stayed employed across cycles of the pandemic.9 Women were also more likely than men to increase the hours they spent on childcare with the closing of schools and early childhood development centres, which showed that women tend to take on a bigger share of the responsibility of looking after children in the home. This also meant that many were prevented from working the same hours they were able to work before the Covid-19 lockdown, and were delayed or prevented from returning to their jobs or finding employment.

Pregnancy simultaneously reduces women’s income-generating potential and brings with it several financial responsibilities. Julie Mentor, project lead of Embrace, a national movement for supported and celebrated motherhood, points out that a lack of affordable childcare creates significant barriers to looking for work and continuing to work.

4 Harrison, D. 2023. Why Supermarkets should slash the price of these 10 foods. Financial Mail, 2 March. https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/fm-fox/2023-03-02-whysupermarkets-should-slash-the-price-of-these-10-foods/

5 Black R.E., Victora C.G., Walker S.P., Bhutta Z.A, Christian P. de Onis M., et al.; the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013: 371:243–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

6 Western Cape Dept of Health and DG Murray Trust (2023). Western Cape Stunting Baseline Survey on under-5-yr-old children.

7 Field, S., Honikman, S. and Laurenzi, C.2020. Food Insecurity, Maternal Mental Health, and Domestic Violence: A Call for a Syndemic Approach to Research and Interventions. Maternal and Child Health Journal 24, p 401–404 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-01902872-8

8 Realising women’s rights for an equal future on Women’s Day. StatsSA. 9 August 2021. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14559

9 Casale, D. and Shepherd, D. 2021. Gendered employment dynamics during the Covid-19 pandemic. National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/4.-CasaleD.-_-Shepherd-D.-2021-Gendered-employment-dynamics-during-the-Covid-19pandemic-Evidence-from-four-waves-of-a-South-African-longitudinal-survey.pdf

1PREGNANT WOMEN ARE FINANCIALLY VULNERABLE

8 Issue 24 /// June 2023 ESCAPING THE INEQUALITY TRAP: THE CASE FOR SUPPORTING PREGNANT WOMEN

WHAT DO EXISTING SOCIAL SAFETY NETS LOOK LIKE?

South Africa offers a child support grant to poor and vulnerable families, but this grant is only available once the infant is born, missing a critical window of opportunity in pregnancy when brain development is happening and when pregnant women are especially vulnerable to unemployment. At the moment employed female contributors can apply to the Unemployment Insurance Fund to receive maternity benefits when they go on maternity leave. To qualify for the benefits, they must receive less than their normal wages while on maternity leave.10

There is also the Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant of R350 per month for six months to be paid to individuals who are currently unemployed, and do not receive any form of income, social grant or UIF payment etc. In his State of the Nation speech in February 2023, President Cyril Ramaphosa said that work was under way to develop “targeted basic income support” known as the Basic Income Grant (BIG) in South Africa – separate from the temporary SRD grant, which would be extended. At R350, the cost of the grant would range from R27 billion (if offered to original SRD recipients) to R252 billion if offered to everyone in the country (universal grant).11

Mentor believes South Africa needs a comprehensive and efficient social security system that caters to women who are self-employed and employed in the informal economy.

2THEIR CHILD IS AT RISK OF STUNTING

The World Bank considers stunting to be one of the most serious, but least-addressed, problems in the world.12 It affects the development of more than a quarter of South African children under five years old.13 The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting hunger crisis is expected to exacerbate stunting globally, increasing the need for critical nutritional services among children by 15% and placing an additional 1.7 million South African children at risk for stunting by 2025.14

Dr Edzani Mphaphuli, Grow Great executive director, says the time of greatest vulnerability to stunting is the first 1 000 days of a child’s life. “It’s a time when brain development is happening, so [it offers] an opportunity to establish a foundation for children’s academic success, health, and general well-being but it is also a time when the brain is most sensitive to poor nutrition and toxic stress.” How well or how poorly mothers and children are nourished and cared for during the first 1 000 days has a profound impact on a child’s ability to grow, learn and thrive. But sadly, in our context, the first 1 000 days is a time of great vulnerability for many of South Africa’s women and children.

10 https://www.gov.za/services/uif/maternity-benefits-uif#:~:text=As%20an%20 employed%20female%20contributor,you%20are%20on%20maternity%20leave.

11 Basic income grant for South Africa is coming. Business Tech. 9 February 2023. https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/663607/ramaphosa-confirms-basicincome-grant-for-south-africa-is-coming/#:~:text=Most%20proposals%2C%20 however%2C%20fall%20into,month%20for%20all%20unemployed%20adults).

12 The World Bank. 2021. Investing in Nutrition Can Eradicate the “Silent Pandemic” Affecting Millions of Poor Families in the Philippines. Press Release No: 2021/10/PH. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/06/15/investing-innutrition-can-eradicate-the-silent-pandemic-affecting-millions-of-poor-families-inthe-philippines-world-ba

13 Stats SA. 2017. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicator Report https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2003-00-09/Report%200300-092016.pdf

14 Reddy, S.2021. The 'slow violence' of malnutrition in South Africa. United Nations South Africa. https://southafrica.un.org/en/123531-slow-violence-malnutrition-south-africa

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 9 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

3 VULNERABILITY TAKES ITS TOLL ON MENTAL HEALTH

Maternal stresses were greatly increased by the Covid-19 pandemic, lockdown and the economic recession. Dr Simone Honikman, founder and director of the Perinatal Mental Health Project (PMHP) in Cape Town, says that for women already living in poverty, becoming pregnant can often catalyse a scenario of psychological distress, hunger in the household and impaired capacity to take up health or social services. According to the PMHP, studies have found that about one in three women living in adversity in South Africa will experience a common mental illness (depression and/or anxiety) during or after pregnancy.

Honikman explains that when caregivers (mothers, fathers, grandparents and child minders) of young children are psychologically in good shape, they are able to manage the challenges associated with childcare and socio-economic adversity. A caregiver who is mentally well has agency, a sense of purpose, and is best able to plan, problem solve, and access public health and welfare resources.

Healthy engagement with children – whether it relates to communication, stimulation, play or discipline – requires a caregiver who has the capacity to connect at an emotional level with their child. A person who is depressed or anxious usually finds it hard to read the cues of others, especially infants or children who are still learning to communicate their needs and responses. Caregivers with these common mental disorders may respond to infants harshly, withdraw from them, or engage in an intrusive manner.

Thus, PMHP strongly advocates that pregnant women in South Africa have access to financial assistance through a government grant. Global evidence has demonstrated the benefit of a Maternal Support Grant (also called the Maternity Support Grant or MSG) for both mother and infant. Grow Great, Embrace and their partners in the Western Cape have shown that providing digital food vouchers to pregnant women mitigates food insecurity and symptoms of mental distress in mothers (See case study).

“A Maternal Support Grant has significant long-term physical and mental health benefits for mother and baby. It is timebound, ringfenced and essentially easier to budget for and thus could actually be a cost-saver to government in the long term,” argues Embrace’s Mentor.

"Promotion of maternal mental health, which could take the form of social, economic and psychological support as well as access to basic human rights such as shelter and safety, is likely to yield enormous benefit for early childhood development."

Dr Simone Honikman, PMHP director

10 Issue 24 /// June 2023 ESCAPING THE INEQUALITY TRAP: THE CASE FOR SUPPORTING PREGNANT WOMEN

Case Study: MATERNAL SUPPORT

In 2020/21 the CoCare Maternal Support Study conducted by Grow Great, Embrace and partners in the Western Cape found that vulnerable pregnant women who received digital food vouchers reported improvements in maternal hunger, mental health and dietary diversity between baseline and endline results.

INTERVENTION:

› 584 pregnant women in the Western Cape participated in the baseline telephonic survey and received R300 digital food vouchers every two weeks between November 2020 and April 2021.

RESULTS:

› At baseline, 39% of respondents indicated that they had gone to bed hungry in the past seven days. Pregnant women who had experienced hunger in the past week were almost twice as likely to report feeling down, depressed or hopeless. These odds increased when pregnant women reported that a child in their household had gone to bed hungry.

› Respondents who reported receiving no direct social grant income were 63% more likely to report mental health symptoms, such as “having little interest or pleasure in doing things”.

› In order to determine the potential impact of receiving digital food vouchers during pregnancy, participants were contacted in March/April 2021 and again in October/ November 2021. Maternal hunger had significantly decreased at follow-up by 14% versus 39% at baseline. Child hunger also decreased by 9% compared with 22% at baseline.

LEARNINGS:

› These findings supported the evidence base that cash transfers provided to poor and economically vulnerable pregnant women and new mothers can have a significantly positive impact on their food security and that of their children, as well as on maternal mental health.

› The study helped to dispel some of the harmful myths around mothers’ misuse of grants and cash transfers. Follow-up reports documented how vouchers were utilised and showed that recipients had redeemed the vouchers to purchase food, baby items and electricity. This negated popular myths that women use grants irresponsibly and demonstrated that, when given the chance, mothers would most likely act in the best interests of their children.

› The study makes a case for why unconditional cash transfers, and not just food parcels, are a better option for pregnant women to meet their needs and the needs of their unborn children, and why we need to ensure that our social security system recognises, respects and protects the dignity, autonomy and agency of mothers.

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 11 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

Extending the child support grant into pregnancy is one way to support pregnant women living in low-resource communities. As Mentor notes, it is important to change public perception that “because such a grant is timebound (a few months while a woman is pregnant), it can’t possibly be an effective intervention.” She concludes: “Of course, it can't be a standalone intervention. Pregnant women need wrap-around support, but the financial assistance through a Maternal Support Grant signifies that pregnancy has financial implications requiring financial support.”

The MSG should not be seen as a competition for a BIG; rather it is an acutely targeted intervention likely to have significant impact on the core drivers of stunting.

COSTING STUDY OF MSG CONDUCTED IN 2021

To arrive at an estimate of the approximate financial cost of implementing a maternal grant, we need estimates of the annual number of eligible pregnant women.

In a 2021 study conducted by Debbie Budlender, commissioned by the Soul City Institute15, an estimate of 1.1 million pregnancies per year was used, and it was assumed that 75% would qualify in terms of the child support grant means test. According to the Budlender study, the 75% was based on previous estimates and research16. In practice, not all women who are eligible will apply for the grant, especially in the first few years. The use of 75% will thus produce a worst-case scenario in terms of the size of the cost to government.

It is assumed that all women apply for the grant in time to receive it for the full six months of the second and third trimester. Again this produces an over-estimate because not all women will apply so early.

For the value of the grant, the 2021 study used the value of R460 per month.17

These estimates produce a maximum annual budget of R2.23 billion for the maternal grant. This constitutes only 1.2% of the total grant budget for 2021/22.

R460

15 https://www.soulcity.org.za/projects/previous-projects/re-engineering-primaryhealth-care/campaign-for-the-accelerated-reduction-of-maternal-mortality-inafrica-carmma

16 Delany A, Jehoma S & Lake L (eds) (2016) South African Child Gauge 2016. Cape Town: Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town. ISBN: 978-0-7992-2531-0.

17 The Child Support Grant increased to R500 on 1 April 2023 (an increase of R20 since the last adjustment to the grant).

2.2bn

1.2%

grant per month annual budget of total grant budget

12 Issue 24 /// June 2023 ESCAPING THE INEQUALITY TRAP: THE CASE FOR SUPPORTING PREGNANT WOMEN

OTHER FORMS OF SUPPORT FOR PREGNANT WOMEN

Other forms of support for pregnant women that can help address stunting include Flourish mom and baby classes, Grow Great Champions and the PMHP maternal support service.

Flourish

Flourish, a Grow Great initiative, helps parents provide responsive caregiving to their children through a rapidly growing national network of affordable and evidence-based mom and baby classes. It is a social franchise that offers a community of support for new and expectant mothers. It empowers and equips them with the skills and information they need to care for themselves and provide nurturing care to their child in the critical first 1 000 days. Since its inception more than 26 000 moms have been reached.

Grow Great Champions

Grow Great Champions (GGCs) is an initiative that catalyses Community Health Workers (CHWs) to be “Grow Great Champions” who support parents and children. They focus on maternal and child health, growth and early childhood development in the first 1 000 days of a child’s life. In several developing countries, where significant reductions in stunting have been achieved, CHWs have been central to these countries’ stunting reduction strategies. If one considers that a healthy child typically only interacts with the health system for 20 of the first 1 000 days, a strategy that includes interacting with the child and primary caregiver in the home is critical to the prevention of stunting. There are currently more than 2 000 GGC-trained CHWs operating in four provinces who have supported more than 125 000 children.

Maternal support service

For 12 years, PMHP has provided a maternal support service at the Hanover Park Midwife Obstetric Unit. Women visiting this unit come from Hanover Park and surrounding areas and face extremely high levels of social and economic hardship. The service design has recently changed to increase efficiency; shifting from a universal screening approach to providing targeted screening to adolescents, women with HIV, women experiencing violence and women deemed at-risk by the unit’s staff.

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 13 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

WHAT’S NEXT?

Pregnant women are excluded from South Africa’s current social security system. Because women make up a significant proportion of vulnerable workers in the formal and informal economies, many mothers lack basic rights to care and provide for their families. In order for them to break out of the inequality trap, we must provide better systems of support for pregnant women. Mentor believes that changes to the Basic Conditions of Employment Act and the introduction of an improved paid maternity leave policy would help ensure women are not forced to drop out of the economy to care for their young children.

Honikman is of the opinion that a Maternal Support Grant (MSG) would incentivise pregnant women to visit health facilities early in pregnancy and get greater benefits of preventive and promotive maternal health services and monitoring. “Further, a maternal support grant that converts into a child support grant when the child is born would likely promote early birth registration, which has many documented benefits for infants’ health and development. From the evidence available, it is highly likely that the societal benefits of such a grant would significantly outweigh the costs.”

Dr Edzani Mphaphuli of Grow Great says that although mothers are vulnerable, they are – and have historically been – key agents of social change. She urges government to invest in the MSG, rather than “pay the price of stunting in the form of high unemployment, continued poverty and poor health outcomes”. She believes children whose brains and bodies “grow great” in the first 1 000 days grow up to be adults with great ideas that grow great economies!

Learning brief developed by Daniella Horwitz, with contributions from Embrace, Grow Great and the Perinatal Mental Health Project, and edited by Rahima Essop.

Learning brief developed by Daniella Horwitz, with contributions from Embrace, Grow Great and the Perinatal Mental Health Project, and edited by Rahima Essop.

This is the learning experience of:

"Pregnant women need wrap-around support."

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 15 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

Julie Mentor, Embrace Project Lead

HANDS-ON Experience Learning

SOCIAL FATHERS: HOW MEN CAN PLAY A GREATER ROLE IN CAREGIVING AND HOW THIS IMPACTS OUR CHILDREN’S FUTURE

The presence and support of nurturing and responsive caregivers helps children to reach their full potential. Although women have traditionally been seen as caregivers, adult men have an important role to play in the development of children as fathers, grandfathers, brothers, uncles, caregivers and Early Childhood Development (ECD) practitioners.

This brief explores how ECD practitioners and civil society organisations are challenging gender norms and changing perceptions about men in caregiving roles; helping to shape the lives of young people and refreshing attitudes about gender.

June 2023 | Issue 24

Build simple, loving connections for every child OPPORTUNITY 7 16 Issue 24 /// June 2023 SOCIAL FATHERS: HOW MEN CAN PLAY A GREATER ROLE IN CAREGIVING AND HOW THIS IMPACTS OUR CHILDREN’S FUTURE

_

Many children in South Africa live away from their biological father. As the 2021 State of South Africa’s Fathers (SOSAF) report points out, the issue of father absence attracts a great deal of attention, even though there are different degrees and kinds of absence. “Father absence” can be defined as fathers (whether biological or social fathers) who are physically, economically and psycho-socially absent from their children’s lives. The focus on the biological father-mother-child triad overlooks the important role that men play in the lives of children who are not their own, as social fathers, in their wider kinship network.

SOCIAL FATHERHOOD

A social father is a person who takes on the responsibility and role of being a father to a child, but who is not the biological male parent of the child. The status of fatherhood is therefore a social status rather than a biological one, and may be actively sought by and/or ascribed to the person by their family or community. A person could be a biological father to one child and a social father to another.1

2 Ibid, p. 88.

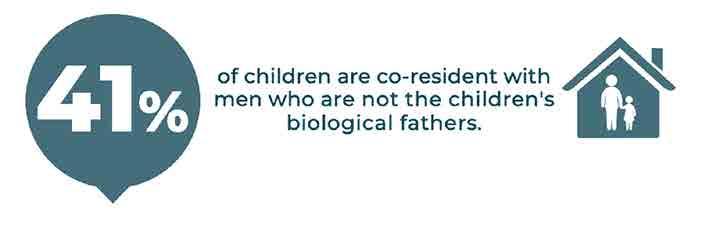

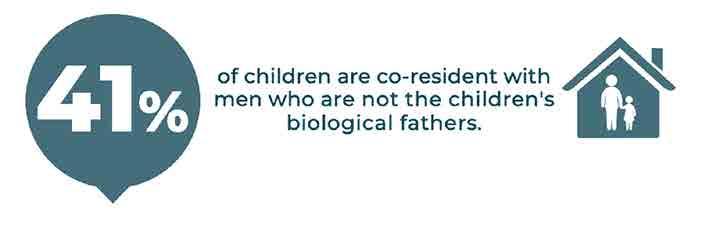

In South Africa, 41% of children live with men who are not their biological fathers.2 Many children are also connected across households to other men such as grandfathers, uncles, brothers and stepfathers. At the end of 2017, 48% of men in the country were living in a household with at least one child. However, during the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, 61% of men reported living with at least one child in the same household.3 Such a marked change in living arrangements, some of which may have been involuntary, shows how circumstances can change rapidly for families in low-resource communities, many of whom are in a state of precarity.4 Although sudden changes in household dynamics pose obvious risks for children, there are also opportunities.

1 Van den Berg, W., Makusha, T.& Ratele, K. (Eds.) (2021). State of South Africa's Fathers 2021. Cape Town/Stellenbosch: Sonke Gender Justice, Human Sciences Research Council, & Stellenbosch University, p. 8. https://genderjustice.org.za/publication/ state-of-south-africas-fathers-2021/

3 Posel, D. & Casale, D. 2020. Who moves during times of crisis? Mobility, living arrangements and COVID-19 in South Africa. Working paper, National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM). Wave 1, 2020. p. 2.

4 Van den Berg,W. et al. SOSAF 2021. p. 54.

Figure 1:

The percentage of children who live with men who are not their biological fathers.

1 Van den Berg, W., Makusha, T.& Ratele, K. (Eds.) (2021). State of South Africa's Fathers 2021. Cape Town/Stellenbosch: Sonke Gender Justice, Human Sciences Research Council, & Stellenbosch University, p. 8. https://genderjustice.org.za/publication/ state-of-south-africas-fathers-2021/

3 Posel, D. & Casale, D. 2020. Who moves during times of crisis? Mobility, living arrangements and COVID-19 in South Africa. Working paper, National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM). Wave 1, 2020. p. 2.

4 Van den Berg,W. et al. SOSAF 2021. p. 54.

Figure 1:

The percentage of children who live with men who are not their biological fathers.

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 17 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

GENDER NORMS AFFECT BOYS AND GIRLS IN DIFFERENT WAYS

Gender norms are shared beliefs, ideas and expectations about how men and women are supposed to be and act, according to a classification system that categorises people as either male or female, known as a gender binary. For example, a common gender norm is that women and girls will and should do the majority of domestic work. These social principles are internalised from a young age and can shape people’s livelihoods and life chances by giving boys and men the advantage over girls, women and other genders.

Gender norms are not static; they vary according to culture and can change over time. But harmful norms perpetuating inequality and discrimination persist, impacting people’s access to healthcare, education, employment and other economic opportunities. Harmful gender norms also perpetuate power asymmetries between men and women, manifesting in different forms of gender-based violence (GBV) and high rates of violence between young men.

Studies and reports have shown that the likelihood of dying from violence is much higher among males; in other words, among those who will be or are fathers. The vulnerability of males begins early – during boyhood. A prevalence study5 of adolescent homicides (among those aged 10 to 17) found a pattern of higher homicide rates among adolescent males compared with adolescent females; and that the differential rates increased with age.

Disrupting harmful gender norms requires strategies and programmes that challenge inequalities. It involves rethinking gender hierarchies and roles while questioning the root causes of inequality and systems of oppression. The authors of SOSAF 2021 have argued that we need “comprehensive prevention programmes that challenge men, specifically fathers, rather than condemning them, to engage in gender transformative relations and positive parenting. We also need a supportive state that addresses the current structural violence, which often trickles down into the direct forms of violence.”6

iWHAT ARE GENDER TRANSFORMATIVE APPROACHES?

These approaches actively seek to examine, challenge and transform the underlying causes of gender inequality. Gender transformative methodologies encourage reflection, self-awareness and creation of new ideas and knowledge through participatory approaches, community conversations and trainings.7

7 https://prevention-collaborative.org/foundations/gender-transformative-programming/

18 Issue 24 /// June 2023 SOCIAL FATHERS: HOW MEN CAN PLAY A GREATER ROLE IN CAREGIVING AND HOW THIS IMPACTS OUR CHILDREN’S FUTURE

“We should be interested in whether those men are a risk to the child, but we could also use that as an opportunity to get men more involved in care..."

Wessel van den Berg, MenCare Officer at Equimundo: Center for Masculinities and Social Justice and lead editor of SOSAF 2021

5 Mathews, S.,Abrahams, N., Martin, L. J., Lombard, C., and Jewkes, R. 2019. Homicide pattern among adolescents: A national epidemiological study of child homicide in South Africa. PloS ONE, 14(8), e0221415.

6 Van den Berg,W. et al. SOSAF 2021., p. 164.

Research by Professor Rachel Jewkes in the international What Works To Prevent Violence Programme demonstrates that the community activism approach to shifting harmful gender attitudes, roles and social norms has proved effective in some contexts.8 However, short-term interventions to shift cultures of patriarchy have little effect, because gender norms are already fixed by early adolescence. Embedding gender-transformative norms requires a prolonged intergenerational project, which starts early on, ideally in the ECD phase, with positive influences from both peers and parental figures.9 Studies have shown that a positive male role model profoundly affects children. Father-child interaction promotes a child’s physical health, perception and ability to relate to others.10

Disrupting harmful gender norms requires strategies and programmes that challenge inequalities. It involves rethinking gender hierarchies and roles while questioning the root causes of inequality and systems of oppression. The authors of SOSAF 2021 have argued that we need “comprehensive prevention programmes that challenge men, specifically fathers, rather than condemning them, to engage in gender transformative relations and positive parenting. We also need a supportive state that addresses the current structural violence, which often trickles down into the direct forms of violence.”

8 Jewkes, R. 2019 What works to prevent violence against women and girls? https://www.svri.org/forums/forum2019/Presentations/What%20works%20Jewkes. pdf, Page 5

9 Kågesten A, Gibbs S, Blum R, Moreau C, Chandra-Mouli V, Herbert A and Amin A. 2016. Understanding Factors that Shape Gender Attitudes in Early Adolescence Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS One. Jun 24;11(6):e0157805. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0157805. eCollection 2016.

10 Baumgardner, J. 2017. The Importance of Positive Role Models. First things First. 15 August. https://firstthings.org/the-importance-of-positive-male-rolemodels/#:~:text=Studies%20have%20shown%20that%20a,competency%20for%20 relating%20with%20others.

WHAT IS EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT?

Early Childhood Development (ECD) is the period of a child’s development from the moment of conception to the point the child enters formal schooling (Grade R). ECD deals with the child’s physical growth, language development, emotional awareness, self-control, social skills and identity. ECD takes place, first and foremost, within the responsive and caring relationship between the child and the parent/caregiver.

Source: Ilifa Labantwana (https://ilifalabantwana.co.za)

i

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 19 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

The following case studies illustrate how South African men are providing positive role models and redefining gender norms by interacting with children in the Early Childhood Development (ECD) space.

Case Study

1

AMAGENTS

Training and Resources in Early Education (TREE) is a non-profit organisation based in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, which develops under-resourced ECD sites into sustainable, quality early childhood education providers. In 2022, specific funding was provided to TREE for the training of a group of male ECD practitioners. They were recruited from ECD forums – a positive indication that there are some males working in the sector. None had ECD qualifications, although some were qualified in other areas. All were eager to receive ECD training.

Cleopatra Nana Cele, a TREE trainer, was impressed by their ECD knowledge; noting how attentive they were to their work, their eye for detail and the way they engaged with children. She says: “They knew ECD; it wasn’t a matter of me introducing ECD to them. They were big guys, but they were nurturing. I was captivated by the way they interacted with the children.”

Most of these male ECD practitioners hailed from Hammarsdale, an area in KwaZulu-Natal that has witnessed high levels of violence since the political unrest of the 1980s. Within this context, several men were showing what was possible when they embraced caregiving roles.

Since the training programme started, more men have moved into ECD and there are now more than 20 men working in crèches in the area. Kwanda Ndoda, DGMT innovation manager, believes that preconceived ideas about men have the potential to be transformed by seeing more men in the childcare space. Ndoda has made a documentary about these men called “amaGents”.

“Can you really expect a young black male to be loving, nurturing and caring, if it has never been modelled before? Or if they never see a male in a caring role until they get to high school? Because there is a dearth of male teachers in foundation phase as well as the ECD environment.

Kwanda

WHO ARE THE AMAGENTS?

› Khetani Sibisi runs Lily & Jerry Daycare in Hammarsdale and is determined to contribute to his community, despite high levels of crime and violence. He survived a stabbing in an attempted robbery at the centre. Despite this, he continues to provide daily ECD services to local children and uses the centre’s garden to encourage the community to grow their own fruit and vegetables.

› Nkanyezi Zulu has an honours degree and was initially working in government when his mother persuaded him to join an ECD centre. He is now the supervisor of the KhulaKahle David Beare centre in Hammarsdale and is involved in ECD management programmes.

“There is a message that I would like to send to men: Let’s take care of our children. Let’s be there for our kids right from the start. Let’s look after the mothers of our children.

Let’s be present in our children’s lives.

20 Issue 24 /// June 2023 SOCIAL FATHERS: HOW MEN CAN PLAY A GREATER ROLE IN CAREGIVING AND HOW THIS IMPACTS OUR CHILDREN’S FUTURE i

Ndoda, DGMT innovation manager

Nkanyezi Zulu, supervisor of the KhulaKahle David Beare centre, Hammarsdale

Case Study

2IXESHA LAM NOTATA (TIME WITH MY FATHER)

The Mikhulu Child Development Trust runs a book-sharing programme specifically targeted at fathers. Ixesha lam noTata (isiXhosa for Time With My Father) is made up of weekly sessions, running for a period of six weeks. It formed part of a research study on fatherhood that took place between August 2021 and December 2022. This study was conducted with 70 fathers of children aged one and two years old in Gugulethu, Western Cape.

iWHAT IS BOOK-SHARING?

“Dialogic book-sharing” is a special kind of interaction between an adult and a young child using a wordless picture book. It is not simply “reading” to a child who listens passively – instead, it is an active exchange, led by the child, and supported by an adult who is attentive to their interests and communication. This enjoyable and simple activity has been proven to improve children’s language and cognitive development, and help children understand and get along with other people. It also influences the adult’s behaviour to be more sensitive and reciprocal in their relationship with the young child.

Source: Mikhulu Child Development Trust (https://mikhulutrust.org/)

After the study concluded, five NGOs were recruited to run the programme with fathers of young children in their communities. Kaathima Ebrahim, CEO of Mikhulu Child Development Trust, says these organisations were eager to embark on the initiative because their work with fathers and men tends to be less structured and focuses on helping men understand why they behave the way that they do. Generally, men gather to talk about issues, but this programme gives them something to do – it gives them a tool that directly helps them shift those behaviours.

Ebrahim says the outcomes are similar to those reported by women: “I did not know this about my child/I learnt this with my child/I couldn’t believe this thing my child said.” Fathers feel excited about spending time with their children and using book-sharing as a tool to support their relationship.

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 21 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

LEARNINGS

DISRUPTING HARMFUL GENDER NORMS

1 2

In South Africa, and many countries around the world, women tend to be responsible for childcare even in dual-income households. The ECD sector in this country is also largely led by women with pockets of male participation. Ndoda notes that when it comes to working with children men feel inhibited because 1) they aren’t expected to do it, or 2) they feel they might not have the capacity to do so because it hasn’t been modelled for them. He stresses that although there is a justified fear of men being violent, women are also capable of violence.

FATHERS WANT SPECIALLY DESIGNED PROGRAMMES

Mikhulu developed Ixesha lam noTata because the level of father participation in their “Book-sharing for Families” programme was low – between one and five percent.

“Initially, fathers stayed away because they saw it as a programme for women. So, we needed to specifically design one to be more attractive to fathers and needed it to work specifically with organisations who work with men,” explains Ebrahim.

The programme was first called “Book-sharing for Fathers”, but feedback showed that most dads were resistant to the word “book”. They said: “We don’t read, we don’t do books.” The conclusion was that the word book would deter dads from participating. But, as facilitators of the programme quickly found out, any anxiety the fathers may have felt fell away when they opened the wordless picture book with their child.

iFIRST DO NO HARM

There are high rates of neglect, abuse and exploitation of children in South Africa. It is critical that anyone working with children is aware of how to respond when they suspect that a child is at risk. Equally important is the need to ensure appropriate conduct in our interactions with children and to ensure that all initiatives benefit children.

It is essential that programmes, activities, research, partnerships and associations are run on the principle of “Do No Harm” and that interventions do not inadvertently put children at risk or make them vulnerable in any way. The Children’s Act No. 38 of 2005 and the Children’s Amendment Act No. 41 of 2007 provide a comprehensive legal framework for the protection of children from all forms of abuse and exploitation.

Source:

Ilifa Labantwana ( https://ilifalabantwana.co.za/)

Gender norms can change. In fact, progressive attitudes about gender are starting to show in fairly recent alterations to labour regulations around paternity leave and popular discourse about the role of men in the care economy. For instance, a survey of more than 1 000 fathers (most under the age of 35), revealed that just 27% of respondents believed that it was inappropriate for men to be preschool teachers.11

“Parents need to do due diligence when it comes to selecting ECD centres for their child to ensure that both male and female practitioners have been properly screened.” 11

22 Issue 24 /// June 2023 SOCIAL FATHERS: HOW MEN CAN PLAY A GREATER ROLE IN CAREGIVING AND HOW THIS IMPACTS OUR CHILDREN’S FUTURE

Van den Berg,W. et al. SOSAF 2021, p. 172.

4 3

POSITIVE MALE ROLE MODELS PROMOTE FEMALE ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT

The Stats SA gender series report says studies have shown that “women are faced with many responsibilities in their respective households that hinder them from actively participating in the labour force, such as childbearing, lack of affordable childcare, and balancing childcare responsibilities with the demands of work”.12 If young boys see men engaging in childcare at school and at home, these boys grow up knowing that men can and should take on caregiving responsibilities at home.

And if more men take on caregiving responsibilities, it may free up time for women to pursue work opportunities. Changes such as better parental leave for fathers when children are born and recruiting more men into ECD can shift the balance of care work.

BOOK-SHARING IMPROVES RELATIONSHIPS AND REDUCES VIOLENCE

Mikhulu researched different programmatic interventions that could best support a child’s early development in terms of cognitive and socio-emotional development and found that book-sharing had the most impact. In a randomised control trial of children aged 14 months, the language of those who participated in the book-sharing study far outweighed those in the control group. It also improved concentration levels. It has also been shown that book-sharing improves the nature of the parent-child relationship, helping the parent engage with the child in a more sensitive and reciprocal way.

Ebrahim explains: “What we learned from the book-sharing study is when you are engaging with your child in a nurturing, caring way, those children are also able to imitate that nurturing, affectionate behaviour. By creating a nurturing, caring engagement with a young child, that child can imitate that affectionate behaviour later on in life.”

BOOK-SHARING CAN CONTRIBUTE TO A LOVING AND NURTURING HOME

SAPPIN (South African Parenting Programme Implementers Network) is a network of NGOs that use evidence-based research to develop parenting programmes across South Africa. SAPPIN has identified book-sharing as a method that supports parents in adopting nurturing approaches to raising children.

“Research shows when a child is in a secure relationship with the parent they are better equipped to benefit from stimulation and be more resilient,"

Kaathima Ebrahim, CEO of Mikhulu Child Development Trust

12 Stats SA 2022. Gender Series Volume IX: Women Empowerment, 2017–2022. Report No. 03-10-26, p. 33 GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 23 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

WHAT'S NEXT? THE CASE FOR MORE MEN IN CAREGIVING ROLES

It is important to shift the gender balance within the paid workspace of ECD because it holds benefits for gender equality; basically releasing women from necessarily being identified as default caregivers and also sets the standard for healthy relationships between men and children. This creates an opportunity for children to grow up seeing and getting to know caring men they can trust. This ties in with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal which aims to reduce the gaps between men and women and allow women and girls to achieve their full potential.13

"The benefits outside the institutional space of paid care are that, if men do spend more time on caregiving, it is good for men in terms of improved emotional satisfaction and belonging, it is good for children in terms of belonging, attachment and developmental outcomes, and it is good for mothers in terms of not having to carry this double burden of paid and unpaid work."

Wessel

van den Berg, MenCare

Officer

at Equimundo:

Center

for Masculinities and Social Justice

This Learning Brief was developed by Daniella Horwitz, with contributions from Training and Resources in Early Education (TREE) and Mikhulu Child Development Trust, and edited by Rahima Essop.

This is the learning experience of:

13 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 concerns gender equality and is fifth of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by United Nations in 2015. The 17 SDGs recognise that action in one area will affect outcomes in others, and that development must balance social, economic and environmental sustainability.

GOAL 2 /// All children on track by Grade 4 25 OPPORTUNITY 7 /// Build simple, loving connections for every child

Changing perceptions about men in caregiving roles can help shape the lives of young people and can refresh attitudes about gender.

Experience Learning

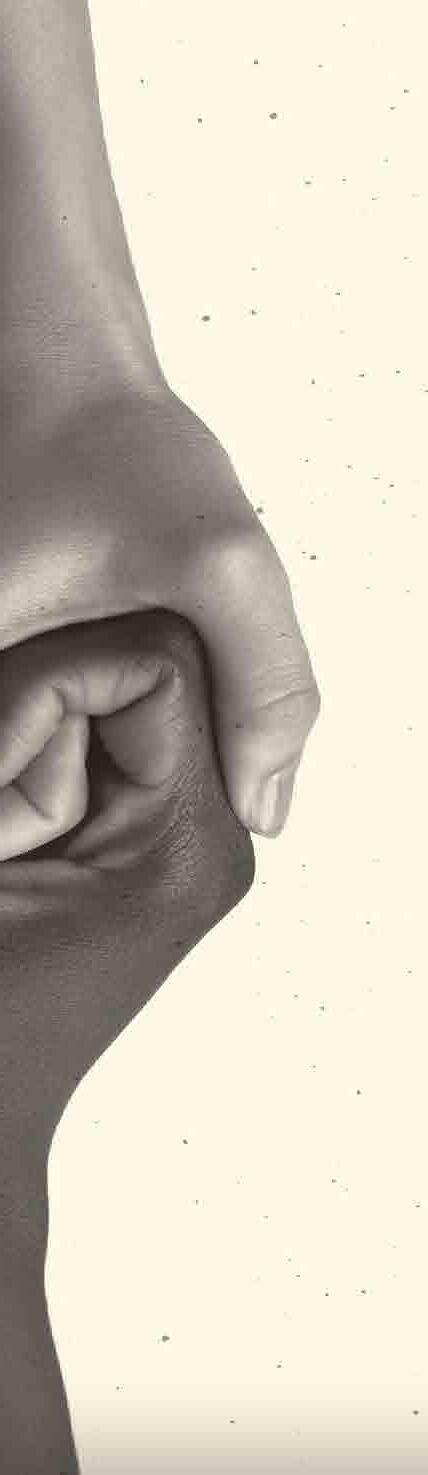

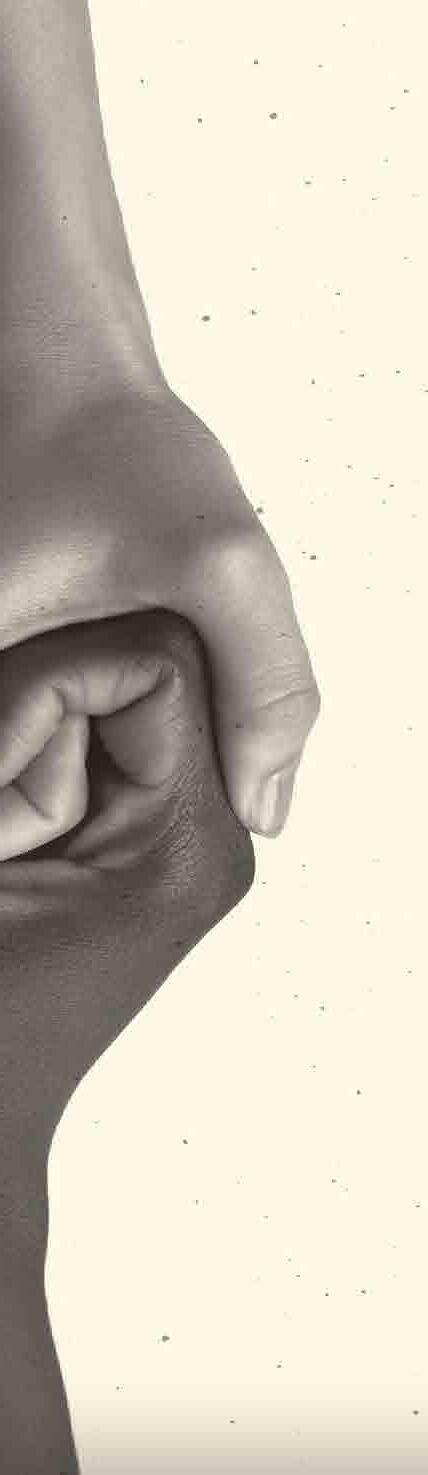

POWER, ACCESS AND AGENCY: UNDERSTANDING BARRIERS TO PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT

_

Parents are the first educators of their children. Their ability to know and love their children has unparalleled benefits. Research shows that encouragement and support from parents/caregivers, not necessarily assistance with specific homework, improves learner achievement even for children attending schools where the education offered is not of the highest quality.1 Although parents have untapped power – and rights – to hold schools accountable for quality standards, many feel they have little say in their children’s education for a number of complex reasons.

This learning brief looks at how three NGOs –Parent Power, Axium Education and Common Good – are driving parent engagement strategies in order to empower parents and fundamentally alter the educational trajectory of children in South Africa.

June 2023 | Issue 24 HANDS-ON

OPPORTUNITY

Support young people to keep their grip on opportunity

10

1 Bergbauer, A. 2016. The role of inter-personal interactions in South African education, Research on Socioeconomic Policy (ReSEP), Working Paper 09/16. https://resep.sun. ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ReSEP-WP-09-BERGBAUER.pdf

26 Issue 24 /// June 2023 POWER, ACCESS AND AGENCY: UNDERSTANDING BARRIERS TO PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT

The South African public schooling system is marked by a high prevalence of grade repetition, overaged learners in high school, and wide learning deficits among learners in poorer schools. In fact, more than 20% of learners in Grades 10, 11 and 12 are three or more years overage, which suggests that they were caught in cycles of grade repetition.2 The outcome of such an inefficient system is that far too many learners do not acquire the knowledge and skills needed to progress through school in the requisite time3 – and about 300 000 drop out annually before completing matric.4

A lack of parental involvement is commonly cited as a contributing factor to poor educational outcomes, and parental “involvement” is often devolved into support on subject-based homework.5 Most parents want the best for their children and will go to great lengths to enhance their child’s life chances. However, there is no denying that doing this is more challenging in contexts where parents lack education and resources.

Research shows that, of the approximately 19% of adults with no or low education, 79% live in poverty.6 In addition, employed parents from poor backgrounds are more likely to have inflexible work schedules and long commuting times, which makes it difficult for them to be involved parents in the current, narrow conception of “involvement”.

THE SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOLS ACT

The South African Schools Act (SASA) of 1996 decentralised certain forms of authority to School Governing Bodies (SGBs) and attempted to alter historical relations based on centralised and authoritarian modes of educational governance, to provide parents – required to comprise a majority on SGBs – with the power to devise policies in the interests of local communities and their own children.

The Act has been praised for its commitment to democratic participation of parents, but criticised for its failure to make a clear distinction between the governance (which should include parents) and management (which should be the responsibility of the principal and educators, accountable to the SGB). This fuzziness has not been good for effective school functioning.

2 Van der Berg, Servaas and van Wyk, Chris and Selkirk, Rebecca and Hofmeyr, Heleen, Learner Flows Through Schools: Using High Quality Administrative Data to Understand Education System Performance (August 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=4009654 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4009654

3 Ibid.

4 Van der Berg S., Wills G., Selkirk R., Adams C. and Van Wyk C. 2019. The cost of repetition in South Africa. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series No. WP13/2019. https://www.ekon. sun.ac.za/wpapers/2019/wp132019

5 Felix, N., Dornbrack, J. & Sheckle, E. 2008. Parents, homework and socio-economic class: Discourses of deficit and disadvantage in the “new” South Africa. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 7(2): p.99–112. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ EJ832211.pdf

6 Stats SA. 2006. Poverty trends in South Africa: An examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/ Report-03-10-062015.pdf

The South African Schools Act of 1996 states that parental involvement is integral to a child's education. However, parents from lower socio-economic backgrounds continue to experience disempowerment and alienation from schools because they simultaneously work and travel long hours due to spatial planning that isolates them from wealthy urban centres and leaves little time for participation in school processes.

Many South African parents living in poverty feel they have little, if any, say in education because their children are taught by teachers who are much better qualified.7 As a result, parents rely heavily on those who occupy positions of power around them, such as school staff, to assist in their lives. This reliance is often simply ignored, leading to an unequal relationship between schools and parents, in which parents are unable to hold schools accountable.

Yet the Zero Dropout Campaign8 has shown that having a meaningful, trusting relationship with a caring adult can make a significant difference in a child’s ability to cope with day-today challenges that could lead to disengagement and school dropout.9 When a parent or caregiver shows interest in a child’s academic journey, we’re likely to see better educational outcomes.

THE CRITICAL ROLE OF A CARING, SUPPORTIVE ADULT

Some learners stay in and do well at school despite challenging circumstances. Researchers studying their resilience have found that these youth often succeed because they have “personal anchors – stable, positive emotional relationships with at least one parent or key person”.10

The status quo can be disrupted if parents are equipped with the language, information and tools to help them engage meaningfully with their child’s school and in their child’s education. This does not mean that they have to be accredited teachers, but rather that they understand the difference their contribution can make to their child’s education. One way to do this is by encouraging parents to see themselves as partners in their child’s education and to drive parent engagement strategies.

7 Smit, A. G. and Liebenberg, L. 2003. Understanding the dynamics of parent involvement in schooling within the poverty context. South African Journal of Education EASA Vol 23(1) p.1 – 5

8 The Zero Dropout Campaign is a DGMT-funded campaign that aims to halve the rate of school dropout by 2030.

9 Hartnack, A. 2018. Parental Involvement: Engaging Families and Ensuring that Caregivers Play an Active Role in their Children’s Education. Technical Brief 2: Zero Dropout Schools Initiative. https://dgmt.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ZeroDropout-Schools-Technical-Report-2.pdf

10 Shore, R. 2003. Reducing the High School Dropout Rate KIDS COUNT Indicator Brief. Baltimore, MD: The Annie e. Casey foundation. https://www.aecf.org/resources/kidscount-indicator-brief-reducing-the-high-school-dropout-rate

i

GOAL 3 /// All young people on pathways to productivity 27 OPPORTUNITY 10 /// Support young people to keep their grip on opportunity

The following three case studies explore varied parent engagement strategies.

Case Study

PARENT POWER

Parent Power seeks to redefine the role of parents or primary caregivers vis-à-vis their children’s education by buttressing their agency as a group, so they feel confident to partner with schools and hold them accountable for quality education.

Parent Power recently commissioned a study11 to understand the factors that shape parents’ perceptions of education quality. The parents who were interviewed spoke at length about educators, resources, safety and the curriculum. However, in these reflections they perceived themselves largely in passive terms. They evaluated educators’ practices, the resources that are available at schools, safety and security concerns, and what they desire from the curriculum, but little was said of how they could potentially contribute to these challenges.

In 2022, Parent Power initiated a year-long programme in the North West province to help parents harness their collective agency and champion their children’s education. Four primary schools and one high school participated in the pilot known as the Parent Champion Journey. Each cohort of Parent Champions comprised a principal, a School Management Team member, a teacher, two SGB representatives and a parent not involved in any school structure. Parent Power took them on a journey that showed them how to build trust and partnerships with parents.

After the training, Parent Champions called the greater parent body to a meeting and discussed obstacles that prevent parents and teachers from working together. Various issues were identified, and an action plan was developed to resolve them. For example, a problem identified during the meeting was drug use by learners. As a means to mitigate the problem of learners accessing drugs after school, a group of parents decided to walk home with learners so they would not be tempted to visit a house where they could buy cannabis. Parent Power met with the cohort twice a term to review their plan and offer additional support where needed.

LEARNINGS 1 2

Andisiwe Hlungwane, project lead, Parent Power, says schools need to commit time and effort into developing a trusting relationship with parents. It is also important to consider the trauma that parents themselves may be carrying from their own school experience, or lack thereof.

Hlungwane acknowledges that building trust with parents may be a big ask from lower quintile12 schools that are already over-stretched, but says that it opens essential lines of communication that can promote parental engagement and improved child outcomes in the long term.

BUILD TRUST OPEN DIALOGUE

In the study commissioned by Parent Power, a prevailing theme emerged about the importance of open dialogue between schools and parents. WhatsApp groups have become extremely useful to parents, saving them from costly trips to school. Educators may also be available to parents via their smartphones, as they can potentially respond when they have time, which may not be the case if parents suddenly arrive at school.

However, the Covid-19 pandemic presented important lessons for parent involvement in school life: parents need clear instructions to assist with schoolwork and WhatsApp communication sometimes needs to be contextualised and not simply “dumped” on parents’ doorsteps.

Parents who do not have access to this form of communication will need to be supported so that there are no exclusions. It is clear parents want principals and teachers to initiate contact with them and to be informed about anything that could influence their child’s school life. However, schools need to make it clear that communication is two-way; parents should feel safe to also reach out to the school about issues at home that could affect the child's school life.

Parent-educator communication can contribute to children having multiple adults who care about them, working together towards their best outcomes and interests.

i

1

11 This study was conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) on behalf of Parent Power.

28 Issue 24 /// June 2023 POWER, ACCESS AND AGENCY: UNDERSTANDING BARRIERS TO PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT

12 For the purposes of allocating and receiving different funding allocations, South African schools are divided into quintiles based on the socio-economic profile of the community in which they are located. Quintile 1 schools are located in the poorest communities, while Quintile 5 schools are found in the wealthiest. Learners in Quintiles 1–3 schools do not have to pay school fees, although Quintile 4 and even 5 may also be non-fee-paying schools.

3

MODEL BEHAVIOUR

“Many parents were not given the opportunity to be involved in their children’s education prior to 1994. Then SASA happened and all of a sudden, parents are expected to be engaged in a particular way. But prior to that, there were no Parent Teacher Associations (PTAs) or things like that in

As previously stated, parents may want to be involved in the school, but are either unsure of how to contribute or lack the confidence to step forward. NGOs can educate parents about their rights, model creative pathways and show parents/ caregivers how to be involved in a positive way.

4 5

PARTNER AT THE RIGHT LEVEL

Not every parent has the time and the capacity to be a member of the SGB. But there are small things that each parent can do to make school a more positive experience for the child. Examples include: listening to their child talk about their school day, assisting their child with homework and ensuring punctuality. “We can show the importance of education to our child by demonstrating that we value it and that we are there to support them the best way that we can,” advises Hlungwane.

INCREASE TRANSPARENCY

Typically, parents fetch their children’s reports at the end of each term, but during the pilot they were given the chance to see how each grade was faring in various subjects. For example, parents could see that 50% of learners in Grade 5 were failing English. This increased sharing of information enabled parents to work collectively to support Grade 5 learners.

lower quintile schools."

GOAL 3 /// All young people on pathways to productivity 29 OPPORTUNITY 10 /// Support young people to keep their grip on opportunity

Andisiwe Hlungwane, project lead, Parent Power

Case Study

AXIUM EDUCATION

Axium Education has successfully trialled several parent engagement strategies in rural parts of the Eastern Cape under the banner of the Public School Partnerships (PSP)13 programme, a model of governance that empowers parents to support the delivery of high-quality education in no-fee public schools. Axium works with 10 schools (eight primary schools and two high schools) in two of the most under-resourced education districts in the country, where many families do not have electricity or running water.

Babalwa Mtumtum, Axium school development manager, recalls: “When I first arrived here the parents really didn’t like to go and support their learners at school. Eish! It was a struggle. Part of the problem is it is a deep rural area, many of the parents are illiterate and there is a high rate of poverty. So, initially they didn’t care about education. But we tried by all means to get them directly involved.”

Her first step was to regularly invite parents to meetings at the school to inform them about the importance of knowing their child’s teacher and motivating and supporting learners. Axium uses a three-pronged approach:

› showing parents practical ways to engage with their child’s education;

› awards and ceremonies for parents and learners; and

› training and support of the SGB.

Axium runs a caregiver engagement initiative through Masakhane (isiXhosa for Let’s Build Each Other), a daily after-school programme teaching maths and English to Grades 4 to 7. The initiative was kickstarted by Covid-19 in 2020. The programme communicates with parents weekly, suggesting an activity they can do with their child (e.g. read a book together). The mode of communication is SMS because few parents can afford smartphones in that geographical region, but most have basic mobile phones. During caregiver engagement meetings, school staff perform skits, showing parents how to practically engage with children and form partnerships with the trainers and the school.

Parents are also invited to a lesson where they can participate in learning activities with their child. Sinovuyo Mcunukelwa, Axium literacy instructional leader and coach, says parents are initially reluctant to participate, but when they see they can do the activities, they are eager to continue.

Axium introduced awards and ceremonies to recognise the contributions of learners and parents (e.g. best-performing learner or best attender of meetings). There is a popular “tie ceremony” for matrics at the high school. The Grade 12s are given a special tie, acknowledging that they have made it to the final year of school and this is also intended to motivate other learners in Grades 10 and 11. Parents join the children on stage and help them knot their ties, while giving their own personal messages of encouragement. These rites of passage help to fortify a culture of support within a school community.

Axium is co-opted on to the SGBs of the eight schools it supports, and runs SGB training. Mtumtum inducts SGB members so that they are familiar with the relevant policies and understand their roles and responsibilities. “You have to know your lane so there are no crashes. So, there is no principal taking the roles of the SGB or vice versa. Each and every person must know their own role.”

An essential element is training on the management of finances with the principal and school finance officer; school finances depend on the SGB and this is often where tensions and disagreements occur. Proper recording of financial transactions ensures transparency and the finance subcommittee shares information with parents.

After training, Mtumtum visits each school to monitor the implementation of various processes. If SGB members are struggling, she supports them with side-by-side coaching. This wrap-around strategy ensures that parents constantly feel supported.

2

“When there are high levels of transparency among the teachers, principal, School Management Team and SGB, you minimise the risk of serious financial mismanagement or abuse."

Babalwa Mtumtum, Axium school development manager, AmaJingqi Public School Partnerships

13 For more information about the PSP visit: https://dgmt.co.za/project/public-school-partnerships/ 30 Issue 24 /// June 2023 POWER, ACCESS AND AGENCY: UNDERSTANDING BARRIERS TO PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT

LEARNINGS

1 2

SGB TRAINING EMPOWERS PARENTS TO HOLD SCHOOLS ACCOUNTABLE

In a deep rural school, having parent SGB members who know their roles and responsibilities, and who can demand that teachers are present and perform competently, is a significant achievement. Part of the reason for this awareness and capacity among parents to hold schools to account was the SGB training and internal financial management training that Axium initiated.

MODELLING ENCOURAGES ENGAGEMENT

Parents who had not completed schooling themselves and lacked confidence were able to re-engage with their children’s work after interacting with Axium. Mcunukelwa explains: “In the beginning it was like: ‘Yoh! I don’t know how to do it.’ But they know now that it is not scary and they can do schoolwork together with their child.” Parents/caregivers have developed a good relationship with the Axium team, communicating with them via SMS if their child is struggling with a problem or is too sick to attend classes.

3

Many parents/caregivers are in food-insecure households. When called to attend meetings at their children’s schools, they often have to travel long distances and do not have money to buy food while on the road because their budgets are already stretched. Axium found that more parents attended meetings when catering was provided. Mtumtum says: “When we eat together, we chat a lot and this promotes a good relationship.”

"Now that I am part of the SGB, I am a treasurer; I observe how the money of the school is spent."

SGB parent

CATERING IS AN INCENTIVE

GOAL 3 /// All young people on pathways to productivity 31 OPPORTUNITY 10 /// Support young people to keep their grip on opportunity

Case Study

3 COMMON GOOD

Common Good is an education non-profit that works with three PSP schools in a more urban context in the Western Cape.

Common Good also runs its own SGB induction training, and SGB members recently attended training offered by the Western Cape Education Department. Yet attendance at SGB meetings remains a challenge. Dave de Korte, education programme director at Common Good, explains: “At almost every meeting, we arrive there only to sit and wait. Then we start getting WhatsApps about people stuck in traffic, who can’t come because they are sick, their baby is sick, there has been a family crisis and they need to go somewhere else. We just never ever get all the parents there. And these are the same parents who put their hands up to be SGB members. I don’t know how you solve this particular problem.”

However, there are other events with high levels of parental involvement and, in some cases, parents initiate participation by asking to help manage stands at their school’s market day. De Korte also notes that parental attendance at disciplinary meetings is good, perhaps because SGB parents who sit on the disciplinary sub-committee are usually very committed to their school’s ethos and values.

LEARNINGS 1

FIND THE GEMS

2 MOBILISE AROUND AN EVENT BE FLEXIBLE

De Korte says it’s important to identify and secure the buyin of parents who are vocal in their community and invested in their children’s education. These key actors in the school community tend to hold sway and can encourage other parents to invest their efforts in the school.

3

When parents arrive at school, it is important to seize the opportunity to interact with them. For example, parents typically visit the school every quarter to get their child’s report and that is an opportunity to meet the educators in a parent-teacher conference. De Korte says: “There is a moment where, four times a year, you will get people on to campus without a problem, and it is just being strategic about how you use that time.”

Parents in lower quintile schools tend to work long hours in low-paid or unskilled jobs or are unemployed. A parent’s work commitments are often a barrier to engagement with schools unless there is flexibility around meeting times. For instance, scheduling a meeting on a Saturday morning may draw more people whose weekdays are busy. Common Good also found parents are more likely to attend if a meeting is catered and if their transport costs are subsidised.

"In each one of our schools we have a couple of gems – parents who are highly invested in their school. These people are from poor backgrounds and offer tremendous value."

32 Issue 24 /// June 2023 POWER, ACCESS AND AGENCY: UNDERSTANDING BARRIERS TO PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT

Dave de Korte, education programme director, Common Good

BENEFITS OF PARENT ENGAGEMENT

Greater parent engagement builds parent confidence so they can:

› show up and support their child and the school;

› confidently hold educators to account; and

› use their voice to champion their child’s education.

WHO SUPPORTS THOSE WHO SUPPORT THE PARENTS?

SAPPIN (South African Parenting Programme Implementers Network) is a network of NGOs working with parents, who come together to support one another and share lessons and challenges. The main objective is to work together to find a collective voice on issues in the parenting sector and to advocate for those issues collectively with government and funders.

“Parents should not be seen as a peripheral appendage to other work that focuses on children. Parents are a critical resource. So if we want parents to show up, we must show them that we are willing to support their needs,” says Kaathima Ebrahim, CEO of Mikhulu Child Development Trust, a SAPPIN member.

WHAT’S NEXT?

This brief has illustrated how parents’ agency can be built and how narrow confines of “parent involvement” can be widened to broader avenues of parent engagement. When parents/ caregivers work together with schools to support children, their trajectory can be altered and they can succeed not only at school, but at life.

Learning brief developed by Daniella Horwitz, with contributions from Parent Power, Axium Education and Common Good, and edited by Rahima Essop.

Learning brief developed by Daniella Horwitz, with contributions from Parent Power, Axium Education and Common Good, and edited by Rahima Essop.

This is the learning experience of:

THE LEGACY OF DOUGLAS AND ELEANOR MURRAY

DGMT is a South African foundation built on endowments from Douglas and Eleanor Murray to promote charitable, educational, philanthropic and artistic purposes within South Africa. Douglas Murray was the son of, and successor to, John Murray, the founder of the Cape-based construction company, Murray and Stewart, which was established in 1902. This company merged in 1967 with Roberts Construction to become Murray & Roberts, with the parent Trusts as the main shareholders. In 1979, the Trusts combined to form the DG Murray Trust as the main shareholder before the company was publicly listed. Subsequently, the Trust relinquished its ownership to a major finance house. Eleanor Murray remained actively engaged in the work of the Trust until her death in 1993.

The Foundation is now the holder of a portfolio of widely diversified assets, which reduces the risks in funding the achievement of its strategic objectives. DGMT currently distributes about R200 million per year and leverages and manages a similar amount of funding through joint ventures with other investors. DGMT’s ultimate goal is to create an ethical and enabling environment where human needs and aspirations are met; where every person is given the opportunity to fulfil their potential, for both personal benefit and for that of the wider community.

By investing in South Africa’s potential we aim to:

› Create opportunity for personal growth and development that will encourage people to achieve their potential.

› Help reduce the gradients that people face in trying to seize those opportunities.

› Affirm the value and dignity of those who feel most marginalised and devalued by society.

The DGMT Board

TRUSTEES Mvuyo Tom (Chairperson) - John Volmink - Ameen Amod - Shirley Mabusela

Murphy Morobe - Hugo Nelson - Maria Mabetoa - Diane Radley - Michael Kahn

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER David Harrison

Douglas Murray House, 1 Wodin Rd, Claremont, 7700 PO Box 23893, Claremont, 7735 +27 (0)21 670 9840 www.dgmt.co.za

The legacy of Douglas and Eleanor Murray Invest in South Africa’s Potential

The legacy of Douglas and Eleanor Murray Invest in South Africa’s Potential