DIRECTED STUDIES (V/I)

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN IN MEDITATION CENTER

Submitted by

Name : Dibesh Man Malego

Roll no : 72013

Date : March 2020

Kathmandu Engineering College

Department of Architecture

Abstract

The study and report are prepared as a partial fulfillment for the subject Directed and Seminar Studies and Seminar, as in the syllabus of ninth semester (V-year, part 1) of Bachelor degree of Architecture, by Institute of Engineering, Tribhuwan University.

Architecture has the unique ability of being able to have a direct effect on the way people feel within a space. The interplay between architectural design and human psychology is significant, yet it remains largely unnoticed or even ignored both in and outside the academic study. The current mentality towards sustainable architecture is incomplete. As we are rightfully concerned with energy conservation, material life cycles, recycling and footprint. However, we tend to overlook the deeper psychological implications contributing to prosper the quality of life. In order for architecture to become truly sustainable, our buildings must actively work to reduce local environmental pollution and must also work to repair the individual’s connection to the essence of life.

The research covers behavioral implications of the outlined architectural elements on the interrelationship – both positive and negative – between designed spaces and our psychology. The study is done in the basis of the secondary data for literature review and International case studies through internet and field visits and interviews for national case study. The information collected are compared and analyzed, which has helped to plot a guidance necessary for interventions in the meditation center.

Any valuable comments and suggestions about the improvement of report are always appreciated.

“Whatever good things we build, end up building us.”

Acknowledgement

This project is a part of an academic work as a requirement in the syllabus of Bachelor Degree in Architecture for the subject as in the syllabus of ninth semester (V-year, part 1), Directed Studies and Seminar. I would like to express my gratitude to Asso. Prof. Kailash Shrestha, Asso. Prof. Ar. Moon Singh Dongol, Asso. Prof. Ar. Sweta Shrestha and Asso. Prof. Subash Phuyal for providing valuable guidance during the research. Their valuable lectures and suggestions always helped me to handle the challenges and their appreciations for good work always kept motivating me to do much better..

I want to further acknowledge the Department of Architecture, Kathmandu Engineering College and all the faculty members, for an opportunity to research on psychological impact of architectural design in meditation center.

Last but not the least; I am thankful to all, who lent their help during the research. I will always cherish their support, guidance and encouragement that bolster me to achieve my goal. I hope the study will be extremely beneficial for the forthcoming future projects.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

The relationship between architecture and the human body obviously has a long history. And the questions that arise when exploring this relationship are more than simply about finding the proper dimensions and placements within architectural space to “accommodate” a person and their behaviors within it. The relationship between architecture and the human body dives deep into why those behaviors manifest in the first place, as it calls upon the experiential characteristics and qualities that spark when the two unite — impacting not only occupant behavior through the body, but also impacting occupants intellectually, emotionally, physiologically and even spiritually through the body as well.

The interplay between architectural design and human psychology is significant, yet it remains largely unnoticed or even ignored both in and outside the academic study. Moreover, the relationship between design and psychology is not only consequential, it is bidirectional. On the one hand, successful design has been shown to have clear psychological and physiological impacts; on the other, psychology, human experience, and the function of our neurological systems all play a significant role in what we perceive to be successful design.

1.2. Problem statement

“The positive and negative psychological impact of Architectural Design in meditation center.”

1.3. Research Questions

How does a built environment influence human psychology?

How can a person develop independent thinking and decision making attitude?

How different spaces can impact mental, social physical environment.

What is the relation between human psychology and built spaces?

How does our building shape us?

1.4. Research Objectives

To find out how to manipulate spatial impact on people and environment.

To find out the essence of built form in user experience.

Identify possible measures to promote physical, social and psychological health.

1.5. Delimatation, focus and scope of the research

The main focus of this research is to gain knowledge about all the positive and negative aspects related to the application of different built spaces in a building as well as the environment and the processes involved. The study shall not cover detail study of the psychological behavior. This research only deals with the human behaviour and psychological impact of designed spaces and hence it is quite limited.

1.6. Rationale of the study

If science could help the design profession justify the value of good design and craftsmanship, it would be a very powerful tool and quite possibly transform the quality of the built environment. The research is done in order to understand how we shape our buildings and how they shape us. Thus, this dissertation will study behavioral implications of the outlined architectural elements on designed spaces and human psychology.

1.7. Methodology

This study is based on the secondary data available in the internet and books. The International case studies are based on the online study of the institutions and the national case studies will be prepared on the basis of the field visits. The methods of study can be briefed as follows:

• Topic selection

• Study on the selected topic browsing internet sources and studying books of related topic.

• Collection of related documents from reports, books and internet.

• Study and analysis of the collected documents from different sources.

• Finding solutions to the questions rose above on the basis of literature study and case studies.

• Analysis.

• Compilation of all the information to produce a final research report.

1.8. Methodology tree

PROBLEM STATEMENT

“The positive and negative psychological impact of Architectural Design in meditation center.”

RESEARCH QUESTION

How does a built environment influence human psychology?

How can a person develop independent thinking and decision making attitude?

How different spaces can impact mental, social physical environment.

What is the relation between human psychology and built spaces?

How does our building shape us?

2. LITERATURE STUDY

2.1. HUMAN SENSES AND ENVIRONMENT

To explore the various architectural elements that affect the built space we have to classify the elements on the basis of how they are perceived .Humans perception is governed by the internal and external senses that are; Sight, hearing smell, taste and touch there are also other internal senses such as thermoception and proprioception .These senses help us to perceive a multitude of elements. The recent advancements in neurological science coupled with evidence based designs and behavioural science literature can help us to determine the qualitative and quantitative attributes of the elements we perceive in the built environment and nature that would aid in stress recovery and subsequent neurological nourishment.

These outlined environmental factors have the biggest role in creating stress relieving spaces because these factors have a dual nature .These factors are studied because

primarily these are the most essential factors that are present in any environment and also these factors can be suitably modelled by the Architect for developing proper effects of stress relief Secondly these elements not only provide stress relief but if used without proper knowledge about design of healing space such as mediation centre these very factors become environment stressors .Thus these elements have to be thoroughly studied and understood for designing a meditation centre.

SENSE ELEMENT PERCIEVED

Sight

Smell

Hearing

Taste

Touch

Thermoception

Proprioception

Colour ,light, forms, texture and patterns

Odour

Sound

Textures and forms

Temperature

Relative positioning and efforts in

movement

The brain is the most important part of the human nervous system. It gathers and analyzes information, and controls most of the body’s organs and system The mind is not a part of the brain, but it is the process of the activities and functions, in particular, those functions in which the human being aware of such as personality, thinking, controversy, memory, intelligence and even emotion. Hence, the mind is what distinguishes between the human and the animal, not the brain.

2.1.1. VISION

Vision is one of the most important senses and is also responsible for perception of light, colour, patterns, forms and texture in the space. A space that is visually beautiful, with the right kind of lighting, colour and use of materials to bring in textures, patterns and forms, creates a largely positive ambiance. Explained below are the effects of colour, light as architectural elements on the human mind. Texture and forms is dealt with in a different section because it goes beyond just the visual aspect of the space.

Light serves for various purposes: to make spaces to find the orientation, to reveal or conceal the spatial volume or features, or to draw attention to a task. Our perception and desire for light also varies among the purposes we will need the light for, for example Spaces for meditation or relaxation have different light requirement than that of space for physical activities.

When performing a visual task, the light that reaches our eyes and is therefore laden with the raw information for our mind is usually reflected light.

Daylight may serve a vast spectrum of users without any major problems but direct day lighting may cause certain discomfort. The Daylight produces glare and direct incidence can also heat up the environment and may reduce the usability of the space. The space in the outdoor environment like meditation rooms or learning rooms may be designed within an envelope of with low transmitting glasses, or shadings, also general outdoor spaces should be designed such that the direct incidence of western and south western lights can be avoided with shading from natural elements.

a) Lighting as an Environmental Stressor:

Of particular interest is evidence that stress levels are responsive to light conditions. The association between stress, cardiac, and healing (immune and inflammatory) responses is now well documented (Sternberg, 2003).Many studies show that stress responses change rhythmically with diurnal modulation, and yet our built environments provide constant, noncyclic light settings. The relationship between light and stress relief outcomes is most important in outdoor environments

b) Circadian Lighting:

Based on some of the evidence cited above, it has been suggested that the introduction of brief ―light showers might provide a means to modulate circadian responses.Such solutions will be particularly useful in built environments where the climate or architectural configuration limits access to adequate natural circadian lighting (e.g., compass orientation, interior spaces, etc.). A number of studies conducted in real world situations show that brief exposure to individual lighting devices can assist in modulating sleep patterns and behaviour

c) Exterior Conditions:

Scientific data reveals that the built exposure to exterior conditions or climates may not provide enough light for circadian stimulation, or may provide more light than is needed to drive circadian rhythms. If an external site does not provide sufficient natural light, window design alone cannot be used to specify the amount of light that will enter a space.

d) The Circadian Cycle:

Every species on earth exhibits a wide range of biological cycles that repeat approximately every 24 hours .These are known as circadian rhythms (circa –approximately ,dies-day) and are exhibited at every level of biological systems, from timing of DNA repair in individual cells to behavioural changes ,like the sleep-wake cycle. Considering the significance of the light-dark cycle for regulating biological functions, and the accumulation of evidence from epidemiological and animal studies linking circadian disruption to compromised health and well-being.

While there is a significant body of evidence that demonstrates that electrical light sources can be used to drive many circadian responses, it cannot be said that a single electrical light condition can replace solar light as a means to stimulate all circadian effects. Many human systems respond to circadian and seasonal lighting changes. Only a few aspects are well understood, and more research is clearly required. Nonetheless, we can form some general design hypotheses based on current findings that are expressed below. (Dickson, 2018)

A published model of human circadian photo-transduction (i.e, the conversion of optical radiation incident on the retina to neural signals) was used to estimate levels of circadian stimulation from four typical outdoor light sources as might be experienced by people under different realistic scenarios. The approach taken was to determine whether sufficient light is incident on the retina to reach a working threshold for stimulating the circadian system and, thereby to ascertain whether and to what degree outdoor lighting might stimulate the circadian system, as measured by melatonin suppression.

e) Results:

A 6900 K LED is predicted to have a modest stimulating effect after a one hour exposure (corresponding to 12-15% Nocturnal melatonin suppression).A reasonable and conservative working threshold for suppressing nocturnal melatonin by light at night following a 30minute exposure would be about 30 lx at the eye for a ―white‖ light source. It is expected that human function, performance, biological, medical, and mood responses will change subject to lighting conditions.

f) Benefits:

It is expected that human function, performance, biological, medical, and mood responses will change subject to lighting conditions. This is not to say that the simple response of creating more light or more windows will suffice. Architectural and electrical lighting must be designed for users, their function, and their environment over time.

2.1.2. Colour

Perceived colour is based on the relative activity of ganglion cells whose receptive field centres receive input from red, green, and blue cones. It appears that the ganglion cells provide a stream of information to the brain that is involved in the spatial comparison of three opposing processes: light versus dark, red versus green, and blue versus yellow.Since perception of colours differ from age to age and between mental states, for enriched environments it will be a more common approach to determine the colours by their brightness colours instead of grouping them with their perceptions. When colours are brighter they will behave as stimuli since they are more recognizable. Brains remember the things easily that are more remarkable. If the colours are used in connection with the spaces, it can strengthen the position in the mental map, and stimulates the memory. However same stimuli are not desired for every function. The brighter the colours, the more attention they attract. It will a better solution to involve neutral colours, with less contrast, and preferably light colours to perform with lighting

Colour preference has been studied for several decades and across many cultures. The following reviews a small subset of this work in order to demonstrate the complexity that must be accounted for in designing colour experiments, and for the interpretation of the results.

g) Cultural Effects:

Abel‘s study of 90 undergraduate students from 5 different cultures expressed colour preference in mosaic design. Researchers found that Japanese students preferred green and Mexicans blue, and that Iranian students chose fewer colours. Choungourian found definite cultural and some gender differences in colour preference of paired comparisons among 160 American, Iranian, and Kuwaiti university males and females. Studied 490 university students (Japanese, Chinese, Indonesian), who selected the most liked colour from a colour chart. People from each country showed tendencies for unique colour preferences, with significant differences in frequency of colours and hues .Our Study of 100 undergraduate students of architecture discipline selected most of royal blues and green colours. A high preference for white was common, along with a preference for some colours. Images based on environmental and cultural aspects may be important influences. However, in order to make direct cultural comparisons, one must also consider the influence of changing preferences that occur over time, and that such changes differ across country and culture even within the same location. A rigorous analysis is required for comparisons across references in order to discern rigid or fixed preferences that will stand the test of time and location. (Herschorn, 2016)

h) Performance and Mood:

The effects of 9 monochromatic office interior colours on clerical tasks and worker mood. Pre/post studies of 9 treatment groups examined proof reading performance, 6 mood states, and colour preference in high/low saturation, dark/light value, and warm /cool colours, in 341 male and 334 female subjects (16–37years). Significantly more errors were made in the white room than in blue and red, with females performing significantly better than males. Saturation of colour was the most salient predictor of difference between male and females, with females indicating more depression, confusion, and anger in low saturation colours (white, gray, beige), and males in high saturation colours (green, blue, purple, red, yellow, and orange). Subjects revealed that they would prefer to work in beige and white offices over orange and purple offices. Ishihar found that 50 male prisoners with normal colour vision responded similarly to normal subjects. Colour preference was assessed using the colour pyramid test in normal subjects (green, blue, red, and yellow in descending order).

2.1.3. Patterns

Patterns recognized by our neurophysiologic apparatus are a key to understanding humanity and its connection to the universe. Patterns organize individual actions into more complex wholes. While this is a process well understood in a language, where words are combined to achieve a meaningful message, it remains outside most people‘s analytical understanding of the world.

Cognitive psychologists recognize patterns as schemata that identify certain preferred sensory inputs. Patterns also control coordinated body movements. Almost every human activity will be found to contain patterns, and those patterns generate the forms and connective complexity of traditional architecture and urbanism (Alexander et. al., 1977) Whereas some design components are contextual (i.e. cultural, temporal, or locationspecific), many are indeed universal. Christopher Alexander‘s Pattern Language codified evolved patterns of how humans interact with their environment and with each other. This prescient book established a practical combinatory framework for design, based on evolved solutions. Incidentally, it already contains many of the key concepts that later came together to define biophilic design. In Appendix II of this Chapter, we have summarized several Alexandrine patterns. The reader can readily see how these design patterns anticipate and support restorative or contemplative design. Architects can draw upon the Pattern Language combining that helpful knowledge with the latest notions of human adaptively into an innovative design. (Ricci, 2017)

Pattern in architecture is often referred to as rhythm; it is what causes the eye to flow from one focal point to the next (for example from one part of a room, or house, to the next). Not only does it work to grab one’s attention, but it also contributes to the beauty of the object (house or room). There are four categories of rhythm in the architectural world: Alternation, the repetition of a contrasting pair; Progression, either increasing or decreasing the size of the element in the pattern; Repetition, continuously repeating a single element; and Transition, the use of a line that the eye is able to continuously follow from one point to the next.

2.1.4. Hearing (Sound)

Previous research in this area has mainly used visual stimuli, for example videos and photographs of nature settings and urban areas. However, sound stimulation is also known to be a potent stressor, evoking unpleasant feelings (annoyance) and physiological stress reactions, especially at high sound pressure levels. Studies on the connection between sound environment and stress recovery are currently lacking. Soundscape research has shown that natural sounds are typically perceived as pleasant and technological noise as unpleasant components of the sound environment. It is therefore plausible that the sound environment may have a similar effect on stress recovery as the visual environment.

Ulrich et al. used video films with sound and found faster physiological stress recovery during exposure to films depicting nature compared with urban environments. However, Ulrich et al. did not control for sound pressure level. Indeed, the soundtrack to their films of urban environmental settings had considerably higher sound pressure levels than the soundtrack to the films of nature environments. This makes it difficult to determine whether the effect was related to the characteristics of the environments or to differences in sound pressure levels. So, although positive effects of visual natural environments are well established, no research has been done using only auditory stimulation with controlled stimuli and sound pressure levels.

In another study researchers induced psychological stress and compare effects of different sound conditions on the rate of physiological recovery. The sound conditions were chosen so that a pleasant natural sound environment was compared with three less pleasant urban sound environments dominated by noise. To study effects of sound pressure level on physiological recovery, the urban sound conditions had higher, equal, or lower average sound pressure levels than the nature sound. Two measures of physiological stress were used: SCL as an index of sympathetic activity and HF HRV as an index of parasympathetic activity. Physiological recovery is associated with a decrease in sympathetic activation (i.e., SCL decreases) and an increase in parasympathetic activation (i.e., HF HRV increases). Because physiological stress recovery should be faster during exposure to pleasant than to

unpleasant sounds, we hypothesized that (i) SCL should decrease faster and (ii) HF HRV increase faster during pleasant nature sound than during less pleasant noise. (Dickson, 2018)

The main purpose of this study was to test whether physiological stress recovery is faster during exposure to pleasant nature sounds than to noise, results show that mean SCL during the nature sound was lower than for the noises. Although this difference was statistically significant only between the nature sound and the high noise, detailed analyses of the recovery functions showed that half-life SCL recovery was 9−37% faster during the nature sound than during the noises. These results suggest a faster recovery of the sympathetic nervous system during the nature sound. Because HF HRV showed no effects of experimental sounds, this null finding suggests that the parasympathetic activation may be less affected by sound during recovery.

The present results suggest that recovery from sympathetic arousal is affected by type of sound (nature sound versus noise). Recovery was faster during the nature sound (50 d BA) compared with the noises, including the low noise (50 d BA) and the ambient noise (40 d BA). The mechanisms behind the faster recovery could be related to positive emotions (pleasantness), evoked by the nature sound as suggested by previous research using non audio film stimuli. Other perceptual attributes may also influence recovery. The Ambient noise was perceived as less familiar than the other sounds, presumably because it contained no identifiable sources. One may speculate that this lack of information might have caused an increased mental activity and thereby an increased SCL, compared with the nature sound. An effect of sound pressure level can be seen in the difference between high and low noise, this difference is in line with previous psychoacoustic research and is not a surprising considering the large difference (30 dBA) in sound pressure level.

The results from SCL are consistent with those of Ulrich et al. who found a faster decrease in SCL after audio-visual exposure to natural compared with urban environments. The effect of natural sound environments on stress recovery may be greater in situations with longer exposure times and with lower sound pressure levels commonly found in recreational and rural areas outside cities. In city parks and other urban outdoor areas, the sound environment is typically a mix of sound from nature sounds and traffic noise. Based on the present results, it seems plausible to speculate that recovery from sympathetic activation in such areas would be less effective than in areas undisturbed by noise. (Dickson, 2018)

The present results suggest that after psychological stress, physiological recovery of sympathetic activation is faster during exposure to pleasant nature sounds than to less pleasant noise of lower, similar, or higher sound pressure level.

2.1.5. Smell (Odour)

Smell is the primary element that immediately influences the human behaviour. We live in a culture that overwhelms us with stimulation delivered through sight and sound. Even taste and touch are highly valued and utilized to expand our experience of pleasure and sensuality. But a human‘s sense of smell has been relegated to the bottom of the sensory pile.

Unlike the other senses, the sense of smell is always on duty. Each day, without any thought, a person breathes in over 23,040 times, inhaling over 238 cubic feet of air . Each breath floods the smell receptors with information about the surrounding environment. We are capable of recognizing approximately 10,000 different odours, with each odour having the power to influence our moods and behaviour.

Smell has a powerful effect on behaviour. Certain smells can brighten up the moods and lift our spirits, like the smell of a good cup of coffee and warm cinnamon buns straight from the oven. An exotic perfume or the smell of your lover‘s skin can lead to intimacy and romance while other scents bring a sense of calm and make us feel at home. (Herschorn,

2016)Aromas delivered directly to the smell receptors in our brain have a powerful effect on our behaviour. Since birth, the human smell receptors have been busy cataloguing every smell that passed through the nostrils.

The brain processes information delivered through our other senses by cognitive identification first, which in turn triggers an emotional response but the sense of smell is unique. It does the opposite. Our smell receptors are directly connected to the limbic system which controls emotional behaviour and memory. Incoming odours first trigger an emotional response which is then followed by cognitive recognition. This is the reason that the refreshing smell of lavender comforts us before we realize the presence of it around us.

Aromas have long been used to influence behaviour. ―Legend has it that Cleopatra perfumed the sails of her ship sent to meet Anthony so the wind would carry a hint of her desire. For centuries, doctors would diagnose various diseases by smell alone and we all know that our shopping experience is influenced by the smells funnelled through the air conditioning systems. Smells are being introduced everywhere – in our household products, our homes, our cars and office environments. (Ricci, 2017)

2.1.6. Touch (Texture)

Texture is a subject of two senses – vision and touch. For instance, the decorative value of a wall paper or a wall colour largely depends on the texture used on it. The dead gloom of black and the dead glare of white are relived and endowed with life and animation, as the heat of red, the cold of blue and the brilliancy of yellow are tempered with texture.

(Herschorn, 2016)

Visual textures are produced by the patterns given to the lighting of the surface both through the way the materials are worked (e.g., vertical or horizontal chiselling of stone) and through the way they are employed in building (e.g., vertical or horizontal boarding, projection and recession of courses of brick). Like all patterns, visual textures create associations of movement, giving rhythm to the surface.

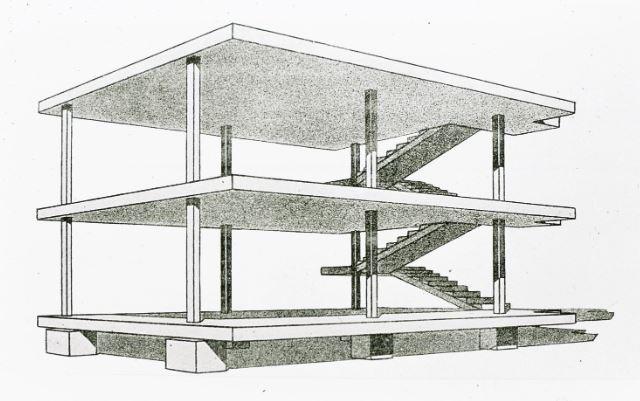

2.1.7. Forms

Human beings connect physiologically and psychologically to structures embodying organized complexity more strongly than to environments that are either too plain, or which present disorganized complexity. It follows that the built environment performs a crucial function — in some instances to the same degree — as does the natural environment. The connection process (outlined in the following sections) plays a key role in our lives, because it influences our health and mental well-being. Studying the geometrical characteristics of the type of visual complexity responsible for positive effects reveals its commonality with biological structures. Applying such concepts to architecture leads to two distinct conclusions. First, that we should bring as much of nature as we can into our everyday environments so as to experience it first hand; and second, that we need to shape our built environment to incorporate those same geometrical qualities found in nature.

A second, and much deeper aspect of architecture for healing spaces requires us to incorporate the essential geometrical qualities of nature into the building and urban structure. This implies a more complex built geometry, following the same complexity as natural forms themselves. Once again, there is a danger of misunderstanding this geometry and superficially copying shapes that are irrelevant to a particular building or city

(Herschorn, 2016)Neurological nourishment depends upon an engagement with information and its organization. This connective mechanism acts on all geometrical levels, from the microscopic, through increasing physical scales up to the size of the city. The correct connective rules were rediscovered repeatedly by traditional societies, and are applied throughout historic and vernacular architectures. Traditional ornamentation, colour, articulated surfaces, and the shape of interior space helped to achieve informational connectivity. Long misinterpreted as a copy of natural forms, ornamentation in its deepest expressions is far more than that: it is a distillation of geometrical connective rules that trigger our neurophysiology directly. These qualities are emphatically not present in the dominant architectural ideology of the twentieth century. Some architects consider that neurological nourishment comes strictly from living biological forms. In their view, ornamented forms and surfaces are derivative of natural forms, and thus provide only a second-hand (i.e. vicarious) experience. We, on the other hand, believe that the underlying geometrical complexity of living structure is what nourishes humans. This geometry could be equally expressed in biological organisms as in artefacts and buildings: the difference is merely one of degree. If implemented correctly, it is not neurologically discernable, only more or less intense. Every living being incorporates this essential geometry to an astonishing degree (in its physical form), whereas only the greatest of human creations even come close. In this view, the distinction between the living and the artificial is left intentionally vague, and life itself is drawn closer to geometry. At the same time, this approach helps to explain the intense connection people feel with certain inanimate objects, i.e. the artefacts and creations of our human past. (Tandan, 2018)

Traditional techniques for creating neurologically-nourishing structures are wedded to spiritual explanations, which are often unacceptable to contemporary architects (and to

business clients). Not surprisingly, the most intense connection is achieved in historic sacred sites, buildings, and artefacts. It is only in recent times that a scientific explanation has been given for what were originally religious/mystical practices of architecture and design. Today, it is finally possible to build an intensely connective building and justify it scientifically, by extending the geometrical logic of the natural world into the built world.

To summarize, two branches of contemporary architecture are beginning to be practiced today. One basically continues to use industrial typologies but incorporates plants and natural features in a nontrivial manner; while the other alters the building materials, surfaces, and geometry themselves so that they connect neurologically to the user. This second type ties in more deeply to older, traditional, sacred, and vernacular architectures. So far, the first (high-tech) method has an advantage over the second (mathematical/sacred) method, because it is already in line with the industrial building/economic engine of our global society. Visually and philosophically very distinct, nevertheless, these two movements are contributing to a rediscovery of our immediate connection to the environment. (Hegazy, 2018)

Perhaps the greatest impact of the biophilic movement is to establish a value system for a particular group of essential geometric qualities. Living forms and the geometrical characteristics they embody must be protected from destruction, because they provide us with neurological nourishment. This is the seed for conservation, both of biological species, as well as for historic and traditional architectures.

In case of need to change the user’s consciousness to meditation and creativity, the brainwaves need to be guided to be theta waves that may be occurred if the user stays in a cylinder space (with steel, wood or glass materials), or in a steel or wooden dome. In addition, this case may be attained if the user stays in a space with a vault form made of concrete, steel or glass.

Alpha waves that help in moderation and mental stability, learning and improving the status of general mood may be occurred during staying in a square space made of concrete or glass materials. This is also obvious in the cases of wooden cone and vault as well as the concrete cylinder. (Ricci, 2017)

In case of need to change the user’s consciousness to attention, concentration or conscious thinking, the brainwaves need to be guided to be beta waves that may be occurred if the user stays in a cone space made of concrete, steel or glass. In addition, this case may be attained if the user stays in a space with a wooden square or a glass dome. There is an obvious relationship between the geometric forms of architectural spaces and their construction materials and the users’ consciousness. Each geometric form resonates with a specific resonance frequency. The resonance occurred causes a change in the human brainwaves which guides his consciousness to a particular status. Depending on the research results, it is evident that there are different effects related to the geometric forms and construction materials of the architectural spaces on the users’ brainwaves and consciousness. (Hegazy, 2018)

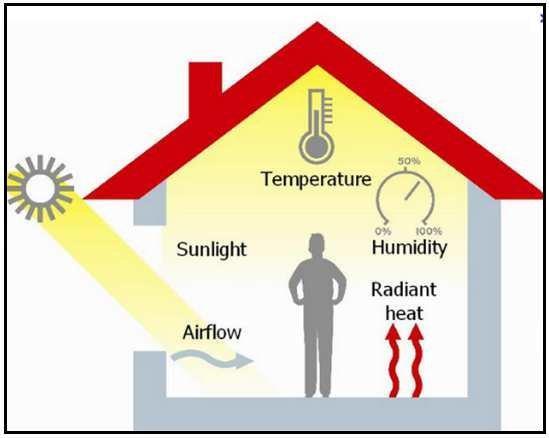

2.1.8. Thermoception (Thermal Comfort)

Thermal comfort is the condition of mind that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment and is assessed by subjective evaluation (ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55).

Maintaining this standard of thermal comfort for occupants of buildings or other enclosures is one of the important goals of HVAC design engineers. Whenever the studies referenced tried to discuss the thermal conditions for different groups of occupants in one room, the studies ended up simply presenting comparisons of thermal comfort satisfaction based on the subjective studies.

Although different researches are undertaken on thermal comfort of people, it is also necessary to study the effects of thermal comfort conditions on the quality and the quantity of healing for patients in hospitals. There are also original researches that show the link between thermal comfort for staff and their levels of productivity, but no studies have been produced individually in healing spaces in this field. Therefore, researches for coverage and methods individually for this subject are recommended. Finally, the interaction between people, systems and architectural design in healing space like meditation centre is a field in which require further work needed to improve the knowledge of how to design buildings and systems to reconcile many conflicting factors for the people using these environments. (Ricci, 2017)

2.1.9. Proprioception

The ability to sense stimuli arising within the body regarding position, motion, and equilibrium. Even if a person is blindfolded, he or she knows through proprioception if an arm is above the head or hanging by the side of the body. The sense of proprioception is disturbed in many neurological disorders. It can sometimes be improved through the use of sensory integration therapy, a type of specialized occupational therapy.

Today, it is believed that proprioception refers to 2 kinds of sensations: that of static limb position and of kinesthesia. Static position reflects the conscious recognition of the orientation of the different body parts, while kinesthesia is the conscious recognition of rates of movement. In general, impulses from receptors in the joints and surrounding tissues are synthesized into a picture of the body's position. The brain then functions to perceive this information. Unfortunately, however, the system for proprioception is not quite that simple. Rather, proprioception is based on a multi-component sensory system which includes: various types of peripheral receptors which detect specific signals and major

sensory afferent pathways which carry the information from the spinal cord up to the cortex. (Ricci, 2017)

2.2. Impact of Architecture on Human Psychology

We may define ourselves as out-going, adventurous, full of wanderlust but it is surprising just how much of our lives are spent indoors. From alarm clocks buzzing in the morning to the last blink in the night, an adult, in spite of being engaged with work and studies, spends as much as 80–90% of his/her time indoors and the space, lighting, colors, acoustics, aesthetics indeed play a big role on the psychology of the individual. So, ever wondered what actually shapes our personality? May be the shapes or shades?

Imagine how much more your design would affect the client if you know what he/she really wants? What are the colors they are fascinated by or the elements that attract them the most in their surrounding? Individual differences are bound to exist so proper architectural implementation is necessary to meet everyone’s psychological desires. Hence, there is a definite relationship between architecture and psychology. (Vats, 2017)

Whether we like a place or not depends on how we perceive it’s design elements, the illumination, materials and furnishing or if the place is similar to any previous ambiance we are well acquainted with. It’s pretty simple, if we are not comfortable with the environment at some place, we are not at ease be it a public space, or our own home. So, it is of utmost importance to keep psychological needs of a person regarding a vicinity in mind while designing a space. The enchanting aesthetics will go in vain if a person inside is stifled by heat from a badly placed window or unable to arrange furniture neatly inside. For an architect to show his skills it is essential to keep in mind the taste and preferences of the client along with the purpose of construction of a particular space. For instance, a prison cannot have bright and vibrant colors simply because it is not meant to be. Likewise an old age home should be soothing and calm where senior citizens could feel like at home, therefore, the architect works on the design scheme by introducing soft colors with some cooling effect, soft materials and patient- friendly features, a healing garden, a space for them to gather, private rooms, taking in the consideration of temperature for their healthy wellbeing. (Vats, 2017)

2.3. The Importance of Architecture

At its roots, architecture exists to create the physical environment in which people live, but architecture is more than just the built environment, it’s also a part of our culture. It stands as a representation of how we see ourselves, as well as how we see the world. While the concept of shelter is a fairly simple thing, the style of buildings was originally shaped by the climate of a particular location, what materials were readily available, as well as the values of the society building them. As the world became more and more connected, the styles evolved, but even in modern construction, there is still an importance in honoring the cultural nuances in the built environment.

2.3.1. More than Just a Building

Architecture not only affects society on a high level but also on a more personal level, it can have a profound impact on its occupants. Everything from the layout of the space to the material finishes can contribute towards occupant health, mood, and productivity. It’s been shown that people who work in well-designed spaces take less sick leave, are more focused, and generally contribute more to their company.

Sterile, concrete landscapes and unimaginative buildings cause higher levels of stress. Designing buildings, as well as cities, to combat this, whether it be beautiful, awe-inspiring architecture, or simply a mindful connection to nature, helps humans to feel more relaxed, happy and engaged.

Well-designed architecture and the connection individuals have to it is not something that’s easily quantified. However, we all know the feeling of walking into a space that just feels right. It’s not only functional but resonates with you on a different, subconscious level. While designing for function is certainly crucial, it’s important to tap into that emotional connection as well, as they both speak to the sense of experiencing architecture. It’s not just an intellectual understanding, but a connection between the user and the space itself in an emotional way.

Throughout history, architecture has stood as a representation of society, reflecting the values, successes, and eventual downfall of civilizations over time. From the monumental structures to the residences and buildings that make up the fabric of a city, we can learn a lot about who the people were who inhabited them long before our time. By studying the built environment of the past, combined with modern-day research on psychology and the environment, we’re coming to understand the effects of architecture on people in entirely new ways.

2.3.2. Ripple effect in architecture

In thinking deeply about the wider impact that architecture has both locally and globally, it concludes that architecture is deeply contextual; an architecture that responds both to its social and environmental context as much as its historical and physical one. If we’re designing for the ripple effect consciously, we’re not only benefitting the individuals but we’re supporting the community at large

2.4. The Positive Psychological Effects of Thoughtful Architectural Design

Architectural style has evolved over time as the preferences of the general public have changed, and as new materials and building processes have been discovered. Some styles have been fads that have quickly come and gone, while others have stood the test of time and been around for centuries, even influencing some modern architecture today. What separates the architectural styles that last from those that do not, a prominent architect in Denver, Colorado believes there are three components that make for a “beautiful” building: form, use, and beauty. Although the word

Beautiful is fundamentally subjective, the feeling associated with it is universal. Seeing something we define as beautiful causes us to feel pleasure. The feeling of pleasure is a result of oxytocin, endorphins and DHEA being released inside our brain. If the sole purpose of buildings is form, or a place where humans can simply gather for some specific purpose, why then would they have the ability to positively impact us physiologically? Again, the answer has its basis in evolution. Buildings that provide us with a sense of pleasure are those that incorporate the architectural elements that our brain recognizes as having similar characteristics to those locations that helped our human ancestors to survive. Thus, it is important to identify which specific characteristics or patterns our brain associates with those survival attributes and why. Patterns represent consistency and organization; a lack of chaos. When our ancestors were able to identify a pattern and predict what came next, their chances of survival were improved. Today, patterns in our built environment that the brain recognizes from nature as having been advantageous to our ancestors evoke the same physiological reaction. It makes intuitive sense that chaos or unpredictability, the opposite of pattern, can negatively impact us physiologically. The human brain has used pattern recognition as a form of survival for so long, it has become something we do subconsciously daily. Although your conscious mind might not realize the feelings it is experiencing are due to a pattern, or lack thereof, our physiological system does resulting in the same sympathetic or parasympathetic response our ancestors experienced. (Chauhan, 2014)

2.5. The Negative Psychological Effects of Poorly Designed Architecture

While the psychological benefits of beautiful architecture are more commonly recognized today, there was a time when the traditionally taught elements of architecture (form, use, and beauty), were discarded in exchange for form, utility and craft.The need for faster, more efficient building and the limited technology at the time, less detailed, smaller houses that focused on the afore mentioned form, utility and craft. This led to the proliferation of small, ugly (in the way that they lacked the characteristics that activate our pleasure response) one floor ‘box’ houses in the 1950’s that were not well thought out in terms of floor plan, use of space, or aesthetics. This trend of simple, architecturally unoriginal buildings was not unique to houses; it also greatly influenced the industrial side of the built environment. Glass, concrete, aluminium, synthetics and steel were the primary materials utilized to create a boxy, futuristic, space like style

Just to highlight the importance, let’s consider the red road flats of Glasgow, built in 1971. Considered the best high-rise estate in the city, these apartments were soon left vacant as the residents found them difficult to warm up in the cold Scandinavia winters.

Another example which highlights a different attribute altogether is the social encounters.

The pruitt- igoe public housing building of St. Louis built in 1959 was praised for wasting no space through some private areas but had to be demolished just opportunity for interaction, social order and perceived safety through knowing one another. As a result, the building attracted substantial crime and vandalism.

Monochromatic colors, poorly placed windows, an absence of architectural detail, and repetitive styles produced a unique form of sensory deprivation. Not only did this trend result in a lack of intellectual stimulation, it effectively removed every aspect of human touch, creating a cold, unwelcoming environment that lacked the ability to produce a positive physiological response or a sense of well-being (Vats, 2017)

2.6. Meditaion

According to sacred texts, Nepal is a place where the Hindu gods and ancient rishis have been coming to meditate and relax for thousands of years. It is believed that meditation rejuvenates one’s energy level and zeal, hence its popularity. It has gained a following worldwide and is taught in many parts of the world.

2.6.1. Types of Meditation

- Mindfulness meditation.

- Spiritual meditation.

- Focused meditation.

- Movement meditation.

- Mantra meditation.

- Transcendental meditation.

2.6.2. Vipassana Meditation

Vipassana, which means to see things as they really are, is one of India's most ancient techniques of meditation. The technique of Vipassana Meditation is taught at ten-day residential courses during which participants learn the basics of the method, and practice sufficiently to experience its beneficial results. People from different background come to reside for 10 days in meditation center. Vipassana teaches to be aware and unanimous, balanced, despite all the ups and downs of life.

“Meditation brings wisdom; lack of meditation leaves ignorance. Know well what leads you forward and what holds you back, and choose the path that leads to wisdom.” - Gautam Buddha