Forme del presente per l’antica città di Ashkelon

sara masi Tessere musive

di architettura

tesi | architettura design territorio

Il presente volume è la sintesi della tesi di laurea a cui è stata attribuita la dignità di pubblicazione. “Il lavoro di Tesi si pone come un esempio altamente significativo di sensibilità progettuale contemporanea in ambito archeologico esplorando orizzonti non convenzionali nel rapporto tra attività di scavo e la fruizione del visitatore”.

Commissione: Proff. C. M. Luschi, A. Ricci, F. Fabbrizzi, M. Pivetta, L. Marzi

Ringraziamenti

Ai miei professori Cecilia Maria Roberta Luschi e Andrea Ricci per avermi accompagnata in questo percorso di crescita e curiosità, permettendo la realizzazione del qui presente progetto.

Ai miei cari, ai miei amici e compagni di viaggio.

Ma soprattutto grazie a voi, mamma e babbo.

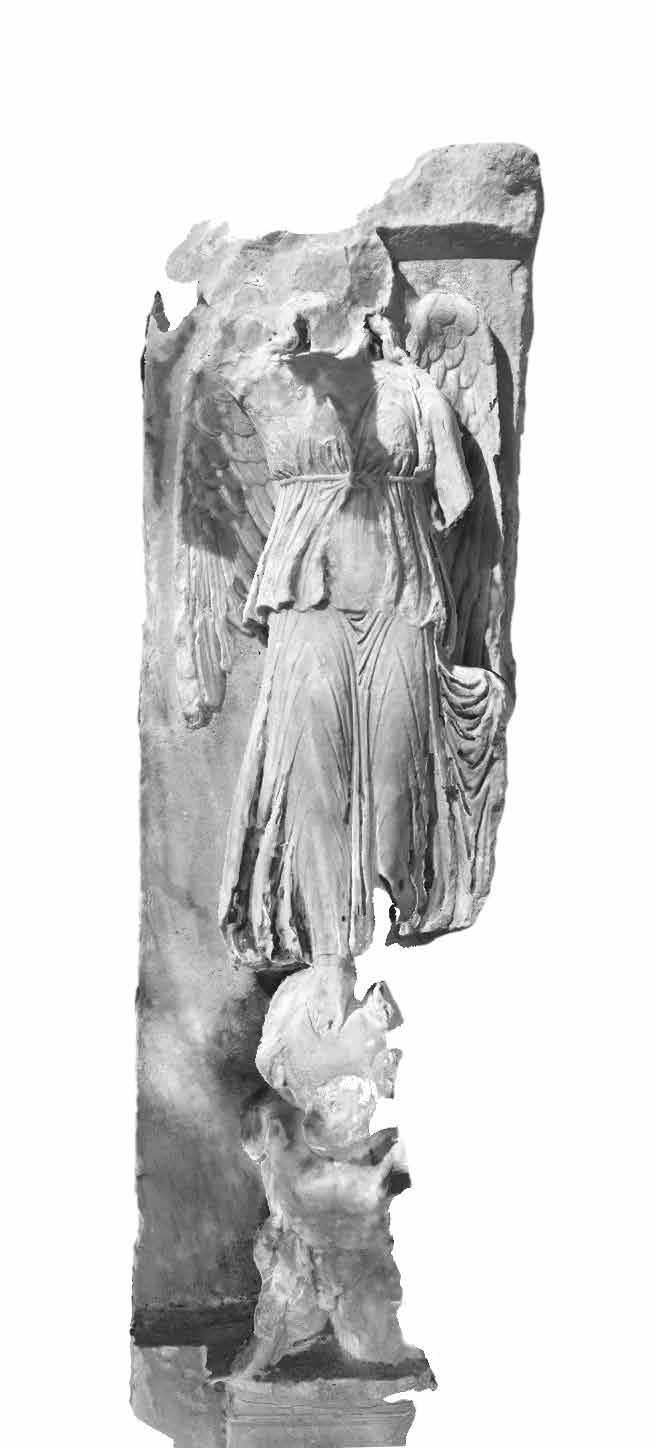

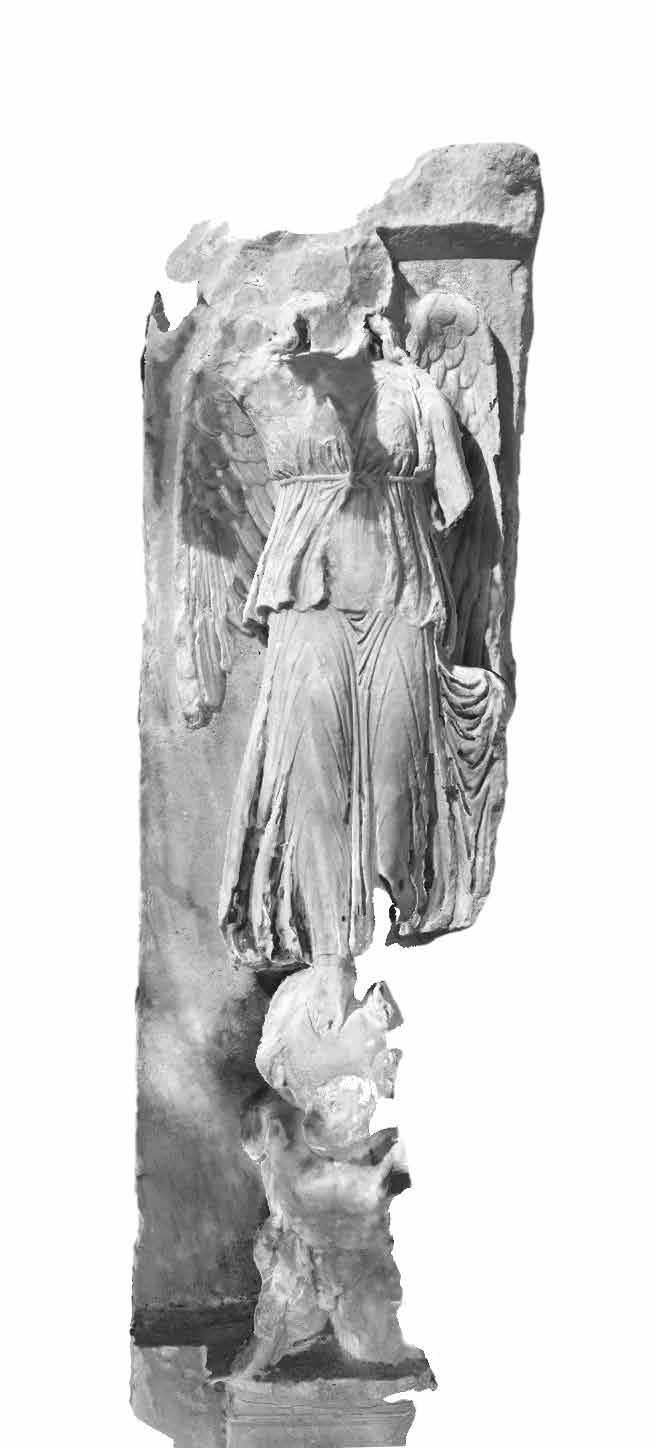

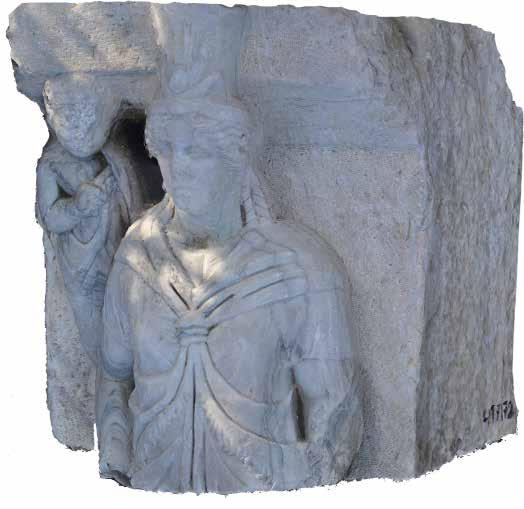

in copertina

Immagine estrapolata da rilievo fotogrammetrico della Nike Alata.

progetto grafico didacommunicationlab

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Firenze

Susanna Cerri

Federica Giulivo

didapress

Dipartimento di Architettura

Università degli Studi di Firenze via della Mattonaia, 8 Firenze 50121

© 2023

ISBN 978-88-3338-181-7

Stampato su carta di pura cellulosa Fedrigoni Arcoset

sara masi Tessere musive di architettura

Forme del presente per l’antica città di Ashkelon

Presentazione Preface

Cecilia Maria Roberta Luschi Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Firenze

Il momento della tesi per un futuro collega rappresenta in genere una prova che guarda oltre la possibilità lavorativa del progetto, dove si misura la capacità di controllare un iter progettuale; spesso valica il confine della ricerca e si tuffa in un mondo altro, fatto di dialoghi con la “Traditio”, di confronti con i colleghi del passato e con la sfida a comprendere il linguaggio dell’architettura.

Non tutti arrivano a queste istanze, non tutti si vogliono misurare con chi prima di loro ha avuto la capacità di controllo e la visione del progetto. Per la tesi in questione ciò è felicemente accaduto.

All’interno della missione AskGate, attività di ricerca riconosciuta dal MAECI e supportata dal DIDA, si è approntata una analisi urbana per meglio comprendere la natura dei rapporti che sono stati messi in campo per una socialità cittadina, che doveva confrontarsi con l’asperità del deserto circostante e la tumultuosità del mare su cui si affaccia. Ashkelon in Israele è un compendio di classicità e di architetture inaspettate, intraviste in lacerti di muri che sono stati lasciati al proprio destino da archeologi e storici. Ma il profilo di un architetto vede nei lacerti testimonianze di forme e da quelle le funzioni a cui dovevano assolvere ed inizia così un percorso di ricomposizione per verificare le questioni architettoniche intraviste. In primis, quindi, studi documentari storici, e per un architetto hanno rilevante importanza le rappresentazioni antiche o le descrizioni letterarie eseguite in periodo bizantino e medievale.

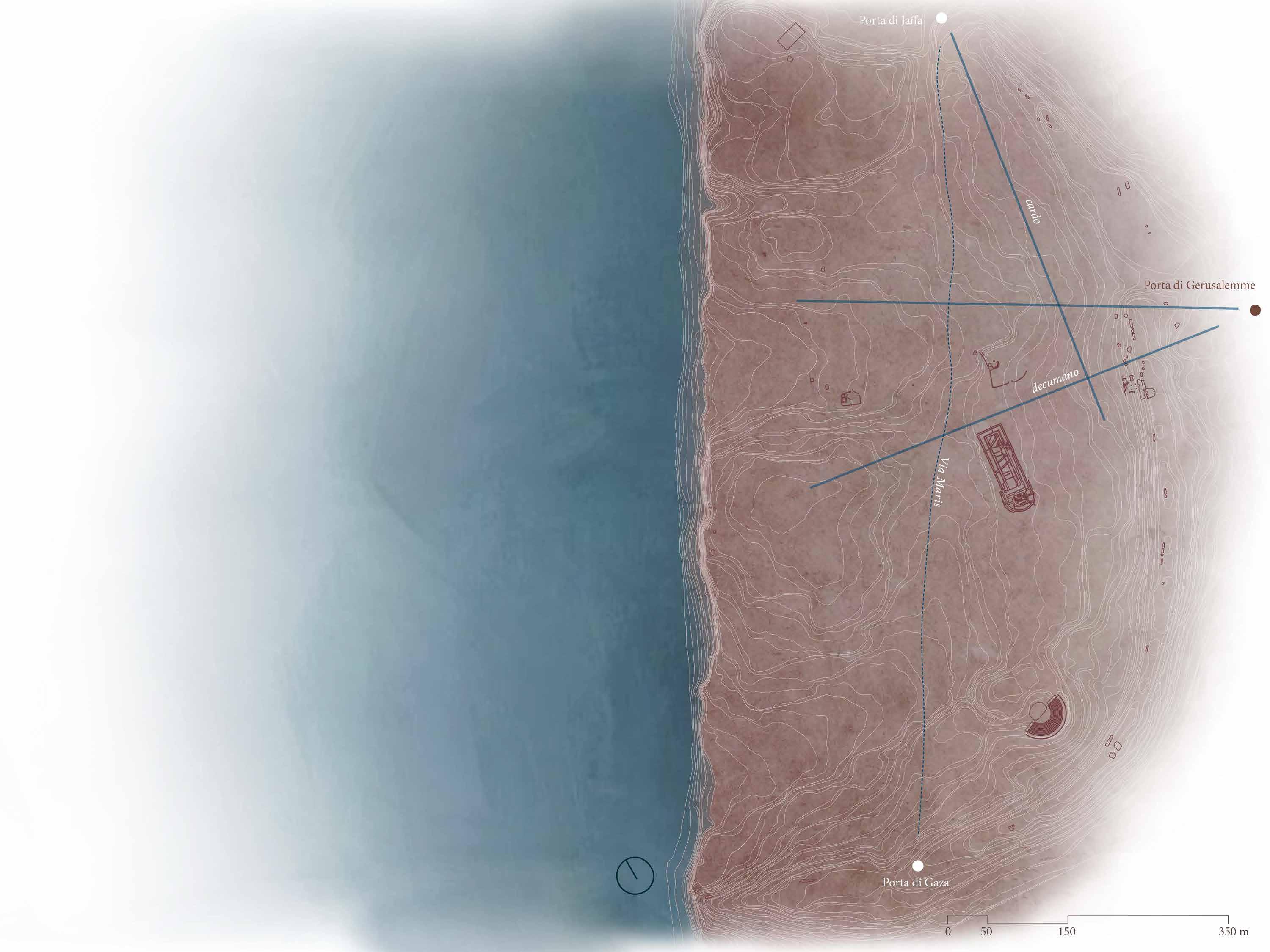

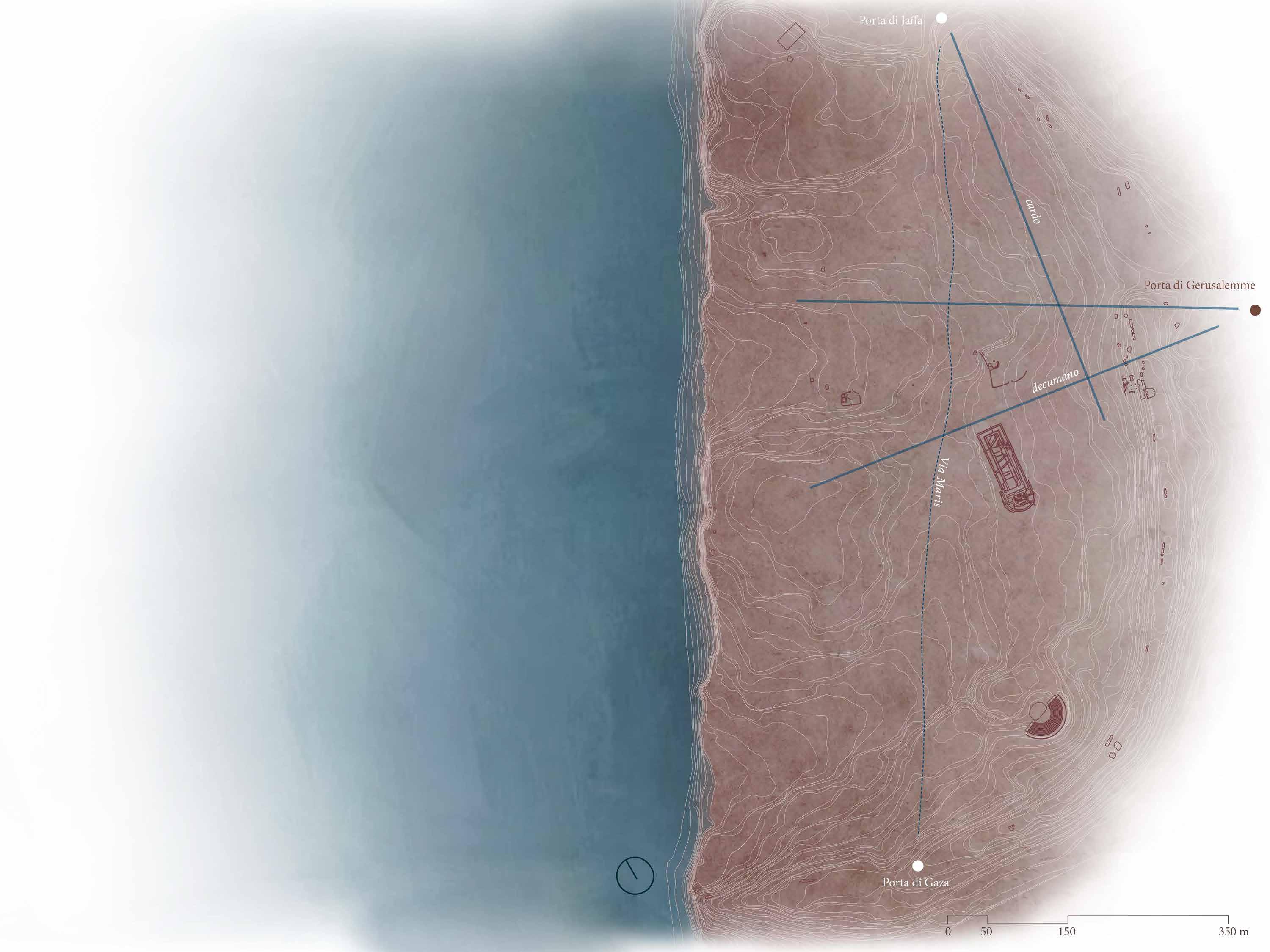

L’accostare la mappa di Madaba all’ipotesi di assetto urbano concretamente realizzato in età tardo imperiale, non è stato un azzardo. Se Gerusalemme è stata ben descritta nelle tessere del mosaico bizantino realizzato fra il 543 ed il 560, anche il frammento di Ashkelon ha per noi credito formale e base per una riflessione sull’organizzazione del doppio decumano e dell’unico cardo. Un opposto a Gerusalemme stessa che annovera invece due cardi ed un decumano.

Ebbene, il verificare la credibilità di questo disegno urbano ha dato il via ad una idea progettuale che, lungi da essere nostalgica della classicità, ha suggerito come dislocare le funzioni atte a realizzare un parco archeologico a più funzioni. Non solo luogo turistico ma anche sito di ricerca attiva, luogo di deposito dei reperti organizzando laboratori e residenze collettive per i gruppi di ricercatori tutti dislocati secondo l’originale organizzazione urbana. Una volontà, dunque, di risemantizzare un’antica idea secondo nuove funzioni da insediare, in un continuo temporale e spaziale che non avrebbe uguali nella terra di Israele. Il progetto, quindi, non è alla ricerca di un pretesto per legittimarsi, ma ha la volontà di porsi in un dialogo con la storia urbana affondando la sua composizione nei tracciati cardo decumani dei severi. Riscoprendo prospettive e organizzando le stesse secondo scorci e visuali antichi rinnovati dalle ricostruzioni degli archeologi e facendo di un mero percorso verso il lido un vero e proprio percorso dove la storia si affaccia per frammenti e scorci. Questo ritengo sia il merito del progetto presentato, essere essenziale, attuale e memore del passato da cui non scappa snaturandolo o volendolo negare, al contrario, confrontandosi e cercando un linguaggio contemporaneo armonizzato alla nuova realtà dal parco. L’azione progettuale diviene quindi una valorizzazione a tutto tondo e risulta efficace anche nella possibilità di essere ampliata nel futuro di pari passo con le nuove scoperte e le nuove esigenze. Moduli che si dipanano su disegno del mosaico di Madaba e che si affacciano oltre che sul mare su una storia bimillenaria.

The moment of the thesis for a future colleague usually represents a test that looks beyond the working possibility of the project, where the ability to control a design process is measured; it often crosses the border of research and plunges into another world, made up of dialogues with the “Traditio”, comparisons with past colleagues and the challenge to understand the language of architecture.

Not everyone arrives at these instances, not everyone wants to measure themselves against those who have had the ability to control and the vision of the project before them. For this thesis, this has happily happened.

As part of the AskGate mission, a research activity recognised by MAECI and supported by the DIDA, an urban analysis was prepared in order to better understand the nature of the relationships that were put in place for a social city, which had to deal with the harshness of the surrounding desert and the tumultuousness of the sea it overlooks. Ashkelon in Israel is a compendium of classicism and unexpected architecture, glimpsed in scraps of walls that have been left to their fate by archaeologists and historians. But the profile of an architect sees in the fragments evidence of forms and from those the functions they were meant to fulfil and thus begins a path of recomposition to verify the architectural issues glimpsed. First and foremost, therefore, historical documentary studies, and for an architect, ancient representations or literary descriptions from the Byzantine and medieval periods are of importance.

The juxtaposition of the map of Madaba with the hypothesis of an urban layout concretely realised in the late imperial period was not a gamble. If Jerusalem was well described in the Byzantine mosaic tiles made between 543 and 560, the Ashkelon fragment also has formal credence for us and a basis for reflection on the organisation of the double decumanus and the single cardo. An opposite to Jerusalem itself, which instead has two cardo and one decumanus.

5

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

“La costa marittima della Palestina può essere definita una delle particolarità del mondo. È risaputo da tutti che questa terra è santa: lunga e spietata spazzata dalla frontiera egiziana al Carmelo la cui sua caratteristica principale è chiaramente visibile. Non ha un porto naturale … Su una costa del genere dobbiamo chiederci perché dovrebbe essere selezionato un punto piuttosto che un altro come porto, e a questo probabilmente troveremo una risposta pronta. L’uomo primitivo alla ricerca dell’ acqua fresca sopra le pianure aride della Filistea l’ha trovata a volte dove meno se lo aspettava, in riva al mare. Una di queste oasi tra le dune di sabbia si erge sull’orlo del Mediterraneo a circa 12 miglia a Qui troverai palme e siepi, campi verdi coltivati e piacevoli zo-

Questo paradiso è Askalon.”

(Phythian-Adams, 1921)

Lungo la ‘via Maris’

“The sea coast of Palestine may be called one of the curiosities of the world. Its long, pitiless sweep from the Egyptian frontier to Carmel is familiar to all to whom this land is holy, and its chief characteristic is plain, so to speak, upon its face. It has no natural harbour On such a coast we have to ask ourselves why any one point rather than another should be selected as a port, and to this we shall probably find a ready answer. Primitive man in his search for fresh water over the parched plains of Philistia found it sometimes where he least expected it, on the seashore. One such oasis amongst the sand-dunes stands on the very brink of the Mediterranean some 12 miles north of Gaza. Its wells to this day can be counted by scores. Here you will find palms and hedgerows, fields green with cultivation and bounteous with grateful shade.

This Paradise is Askalon.”

(Phythian-Adams, 1921)

31°40.156’ N 34°34.289’ E Ashkelon Striscia di Gaza Gerusalemme Tel Aviv (Jaffa) 9 pagina

Along the ‘via Maris’ Mappa

d’Israele e localizzazione principali città

d’interesse Map of Israel and location of main cities of interest

precedente

/

previous

page

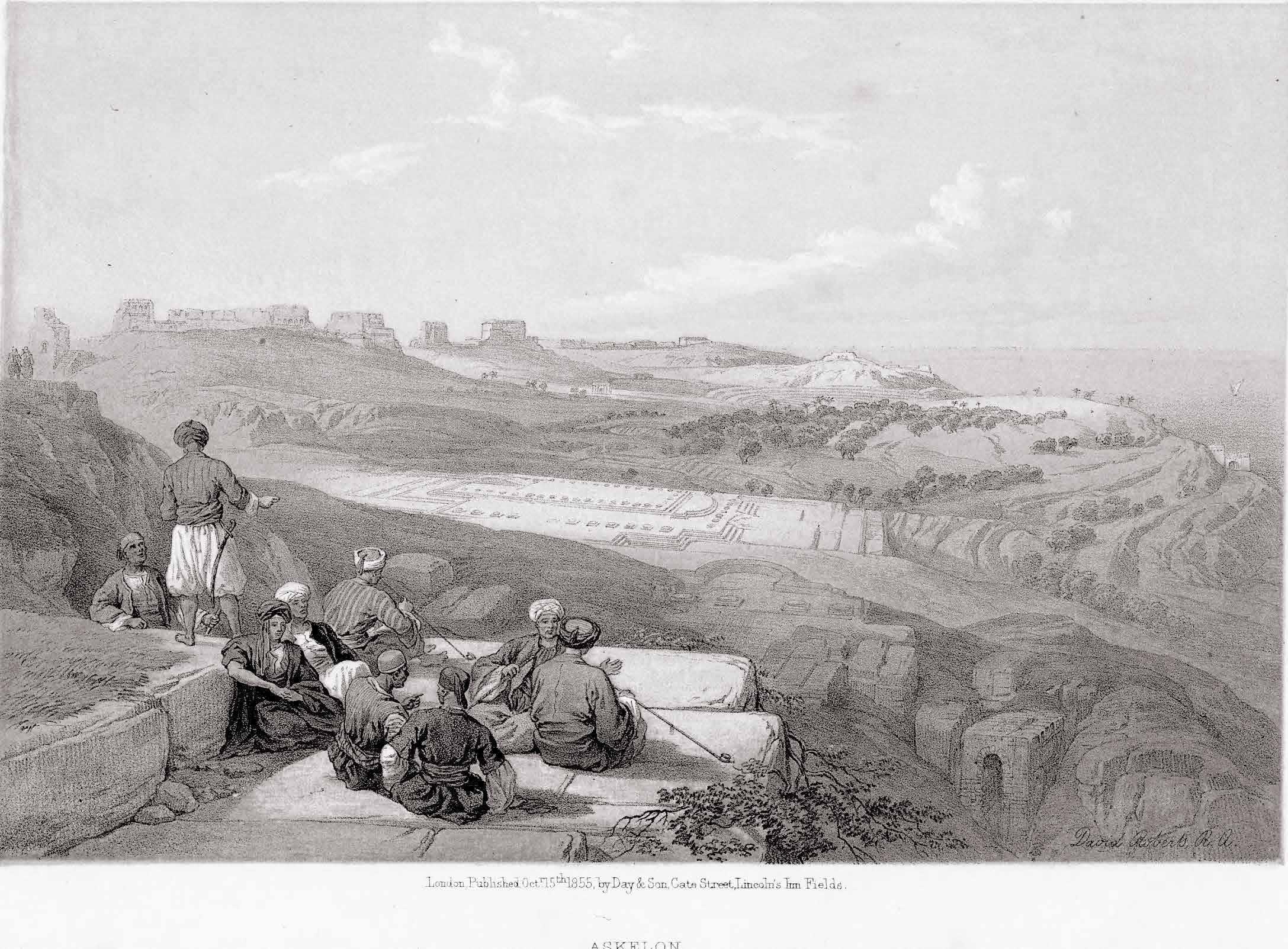

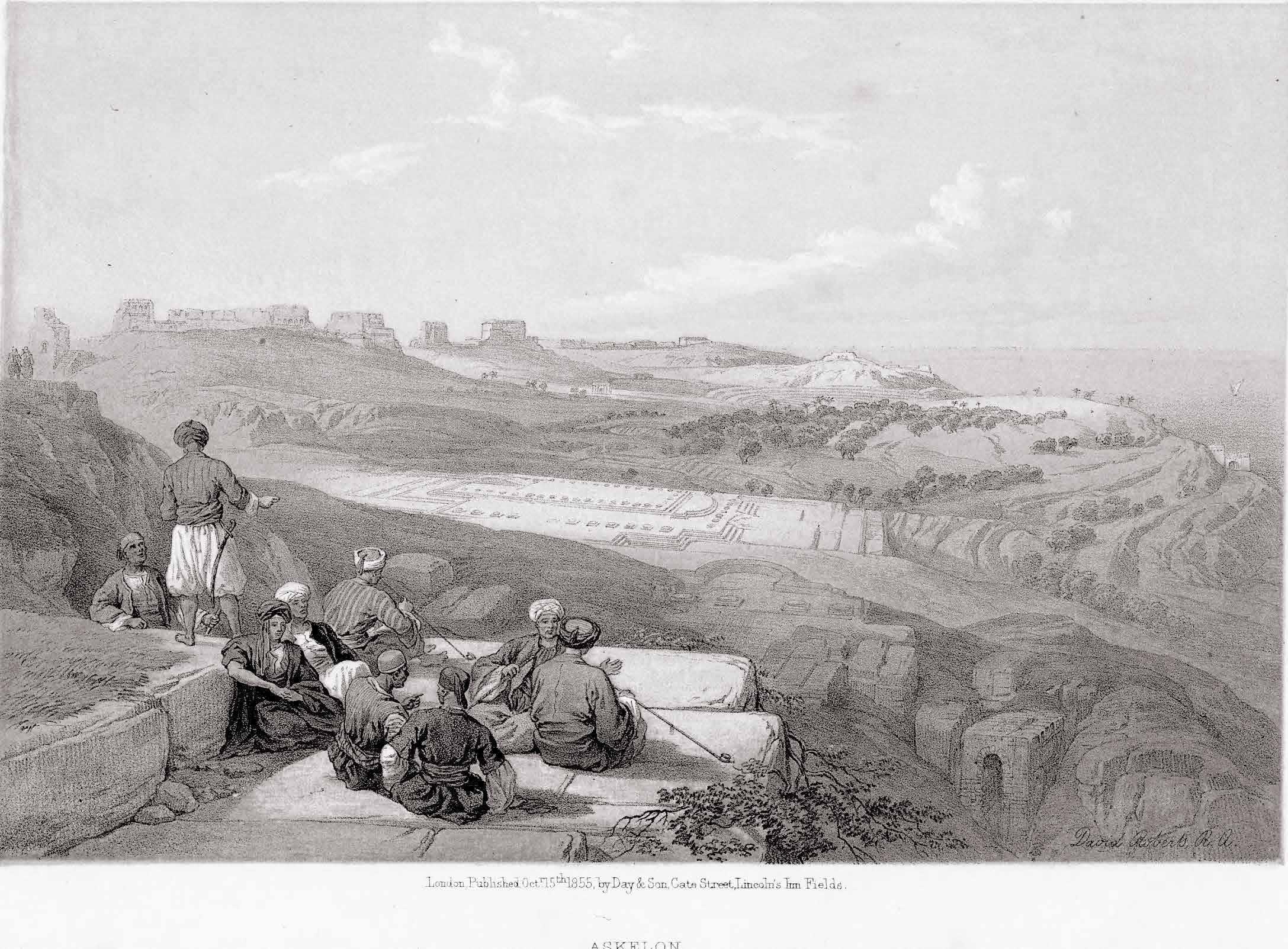

Dipinto della veduta di Ashkelon da nord | Painting of Ashkelon viewed from the north. (David Roberts in 1839)

Il Mar Mediterraneo è quel vuoto tra i pieni che si pone come ponte di connessione tra popoli diversi dove lì si sono incontrati e scontrati, generando culture eterogenee ma caratterizzate dalla loro dimensione corale prettamente mediterranea. Diversi Topoi si riscontrano nelle città appartenenti a questa realtà della culla dei popoli, descritta anche dal geografo greco Strabone, nel I secolo a.C.. Nel suo trattato, parlando del Mediterraneo, egli scrive: “Da questo punto di vista il ‘nostro mare’ possiede una grande superiorità ed è dunque seguendolo che inizieremo il giro del mondo”.

Il Mar Mediterraneo è perciò quella forte quinta scenica che ha caratterizzato le radici della città di Ashkelon e ne ha tenacemente influenzato il suo sviluppo.

Civiltà di mare

Ashkelon è una delle antiche città portuali che si inserisce in questa realtà mediterranea, ed è situata nella striscia costiera israeliana tra Gerusalemme e Gaza precisamente lungo la via

Maris. Antica strada commerciale parallela al mare, la via Maris collegava Alessandria con Damasco attraversando la costa palestinese e passando per Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod e Dor.

Le sue origini risalgono al XX secolo a.C. con l’insediamento dei Cananei dopo i quali si susseguirono popolazioni eterogenee provenienti dal Medio Oriente e dall’Occidente. Nel XIV sec a.C. gli Egizi governano la città che, successivamente, raggiunge importanza in virtù del porto con i Filistei. Nel IX sec. a.C. diventa perciò brama di molte popolazioni tra cui gli Assiri, i Babilonesi, i Persiani per poi diventare una colonia dei Greci nel 332 a.C. con la conquista di Alessandro Magno. Maccabei e Asmonei li succedono fino all’arrivo dei Romani nel I sec a.C. con la costruzione delle mura sugli spalti di origine cananea. Il culmine della prosperità di Ashkelon si ha nel periodo bizantino, in contemporanea con la sua conversione al cristianesimo (IV-VII sec d.C), diventando un potente centro commerciale con l’esportazione di grano e vini.

The Mediterranean Sea is that empty space between fullnesses, being a a connecting bridge between different populations where they have met and clashed. It generates heterogeneous cultures, but all characterised by their typically Mediterranean choral dimension. Varied Topoi can be found in different cities belonging to this cradle of peoples, also described by the Greek geographer Strabone, in the 1st century BC. In his treatise he wrote, speaking of the Mediterranean Sea : “From this point of view, ‘our sea’ possesses great superiority and it is therefore by following it that we will begin our tour of the world “.

The Mediterranean is therefore the striking scenic backdrop that characterized the roots of the city of Ashkelon and tenaciously influenced its development.

Civilisation of the sea

Ashkelon is one of the ancient port cities in the Mediterranean Sea, and it is located in the Israeli coastal strip between Jerusalem and Gaza precisely

along the Via Maris. An ancient trade route parallel to the sea, the Via Maris , connected Alexandria with Damascus by crossing the Palestinian coast and passing through Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod and Dor.

Its origins date back to the 20th century B.C. with the settlement of the Canaanites, after whom heterogeneous populations from the Middle East and the West followed. In the 14th century B.C., the Egyptians ruled the city, which later gained importance due to its port with the Philistines . Therefore in the 9th century B.C., it became the coveted city of many populations, including the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians, before becoming a colony of the Greeks in 332 B.C. with the conquest of Alexander the Great.

The Maccabees and Hasmoneans succeeded them until the arrival of the Romans in the 1st century B.C. with the construction of the walls on the Canaanite ramparts. The peak of Ashkelon’s prosperity occurred in the Byzantine period, at the same time as its conversion to Christianity (4th-7th

Distrutta e successivamente ricostruita fortificata con gli Arabi, diventa mussulmana per essere poi terra cristiana con la spedizione dei Crociati per liberare la Terra Santa nel XII sec d.C.

Nel 1187 Salah al-Din (Saladino) sconfigge i crociati e conquista le roccaforti. Nel 1191 il suo esercito viene sconfitto nella battaglia di Arsuf (Apollonia) da Riccardo Cuor di Leone, ma Saladino riesce ugualmente a demolire le fortificazioni di Ashkelon prima che i Crociati entrino in città.

Nel 1240 viene nuovamente fortificata da Riccardo I di Cornovaglia, ma nel 1270 le forze musulmane guidate dal sultano Bybars conquistano e distruggono definitivamente la città portuale. Dopo tale evento, verrà abbandonata per poi svilupparsi all’esterno delle mura disposte a semicerchio verso il mare. Nel corso dei secoli la popolazione, e di conseguenza la città, si è sviluppata sempre di più nell’entroterra allontanandosi dal mare fino a perdere quell’antico importante ruolo di città portuale che aveva portato all’egemonia economica e commerciale.

century AD), when it became a powerful trading centre with the export of grain and wine.

Destroyed and later rebuilt fortified by the Arabs, it became Muslim and then Christian land with the Crusade expedition to liberate the Holy Land in the 12th century AD. In 1187 Salah al-Din (Saladin) defeated the Crusaders and conquered the strongholds. In 1191 his army was defeated at the Battle of Arsuf (Apollonia) by Richard the Lionheart, but Saladin still managed to demolish the fortifications of Ashkelon before the Crusaders entered the city. In 1240 it was fortified again by Richard I of Cornwall, but in 1270 Muslim forces led by Sultan Bybars conquered and permanently destroyed the port city. After this event, it was abandoned and developed outside the walls arranged in a semicircle towards the sea.

Over the centuries, the population, and consequently the city, continued to develop inland, moving away from the sea, until it lost its former important role as a port city, which had led to economic and commercial hegemony.

11

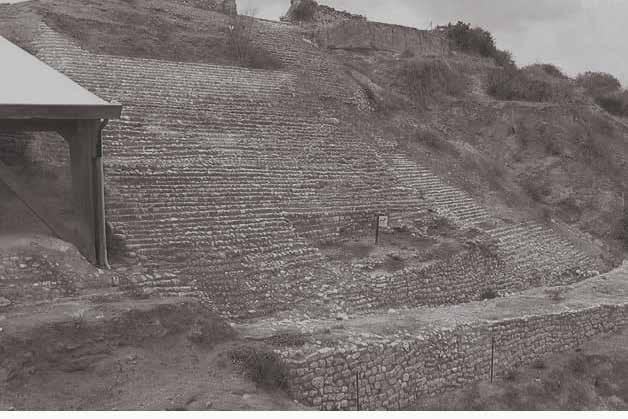

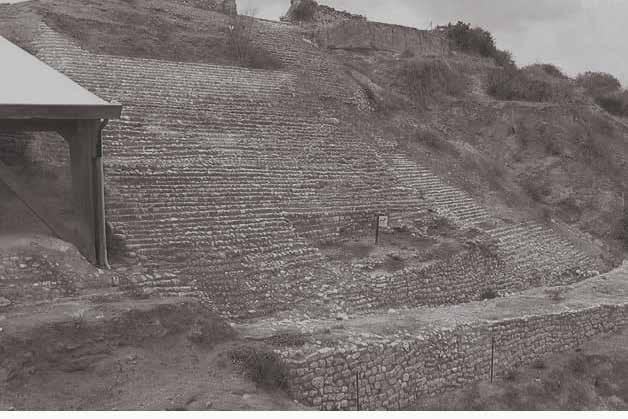

pagina precedente / previous page Rovine delle mura ad est. | Ruins of the Wall from the east.

(photo: Denys Pringle, 2011)

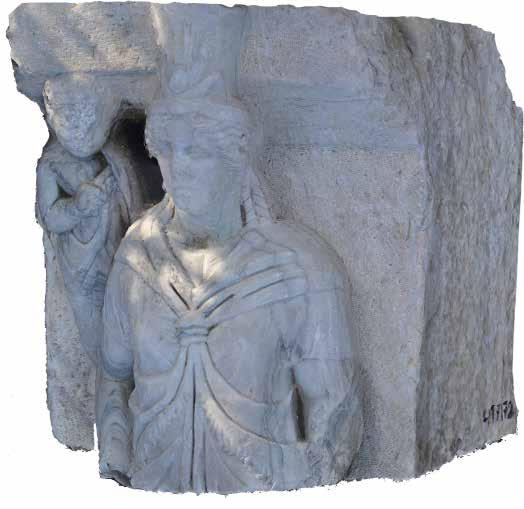

Modello 3D con texture di una parte della statua di Isis presente nel National Park di Ashkelon. | 3D textured model of part of the statue of Isis in Ashkelon National Park. (digital photogrammetry, Ashkgate mission 2020)

Missioni archeologiche

Le rovine dell’antica città di Ashkelon vengono riportate alla luce solamente nel periodo ottomano (XVI-XX sec d.C.), inizialmente per opera della missione archeologica di Lady Hester Stanhope del 1815, succeduta poi dalle varie spedizioni del XX secolo. Tra le missioni di maggior rilievo è opportuno citare quelle di Leon Levy (1985 –2006), in quanto hanno apportato una catalogazione delle rovine ed un’accurata descrizione storica, morfologica e archeologica della città.

Da tali missioni archeologiche, è accresciuto l’interesse per l’antica città costiera da parte delle istituzioni israeliani, aumentando le attività di ricerca e aprendo il sito ai locali e turisti. Allo stesso tempo è aumentata anche la necessità di salvaguardia dei ritrova-

menti derivati dagli scavi, oltre a proseguire l’attività archeologica per poter continuare a dar voce alla sua storia.

Da questa crescente necessità, nel 1964 nasce il parco archeologico di Ashkelon con il nome di National Park Authority

Archeological expeditions

The ruins of the ancient city of Ashkelon were only brought to light in the Ottoman period (16th - 20th century AD), initially by Lady Hester Stanhope’s archaeological mission in 1815, followed by various expeditions in the 20th century. Among the most important missions those of Leon Levy (1985 - 2006) should be mentioned, as they catalogued the ruins and provided an accurate historical, morphological and archaeological description of the city.

From these archaeological missions, the interest in the ancient coastal city on the part of Israeli institutions has grown, increasing research activities and opening the site to locals and tourists. At the same time the need to safeguard the findings from the exca-

vations has also increased, as well as to continue archaeological work continues in order to keep giving voice to its history.

From this growing need, the Ashkelon Archaeological Park was born in 1964 as the National Park Authority.

Matrice Mediterranea

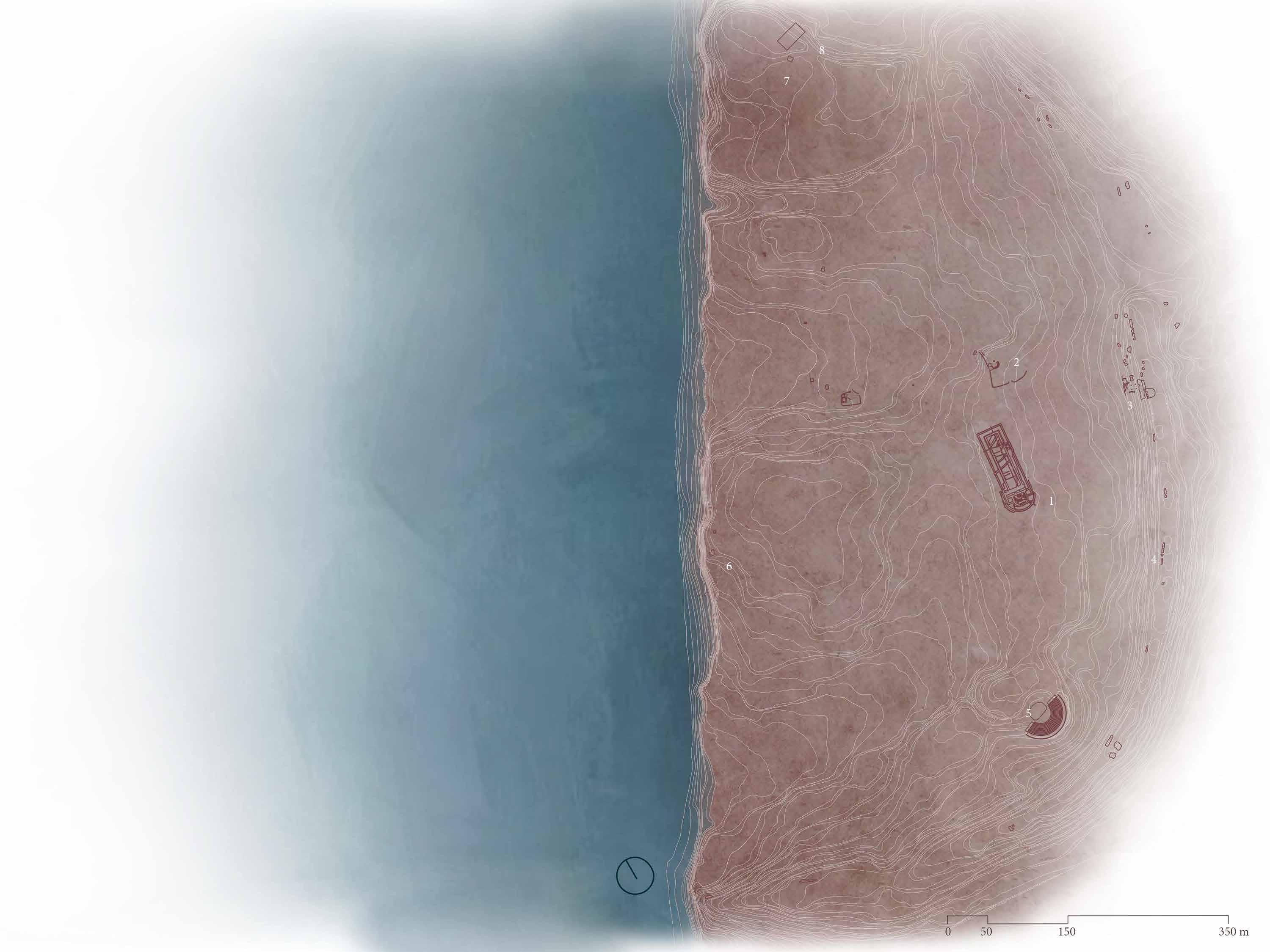

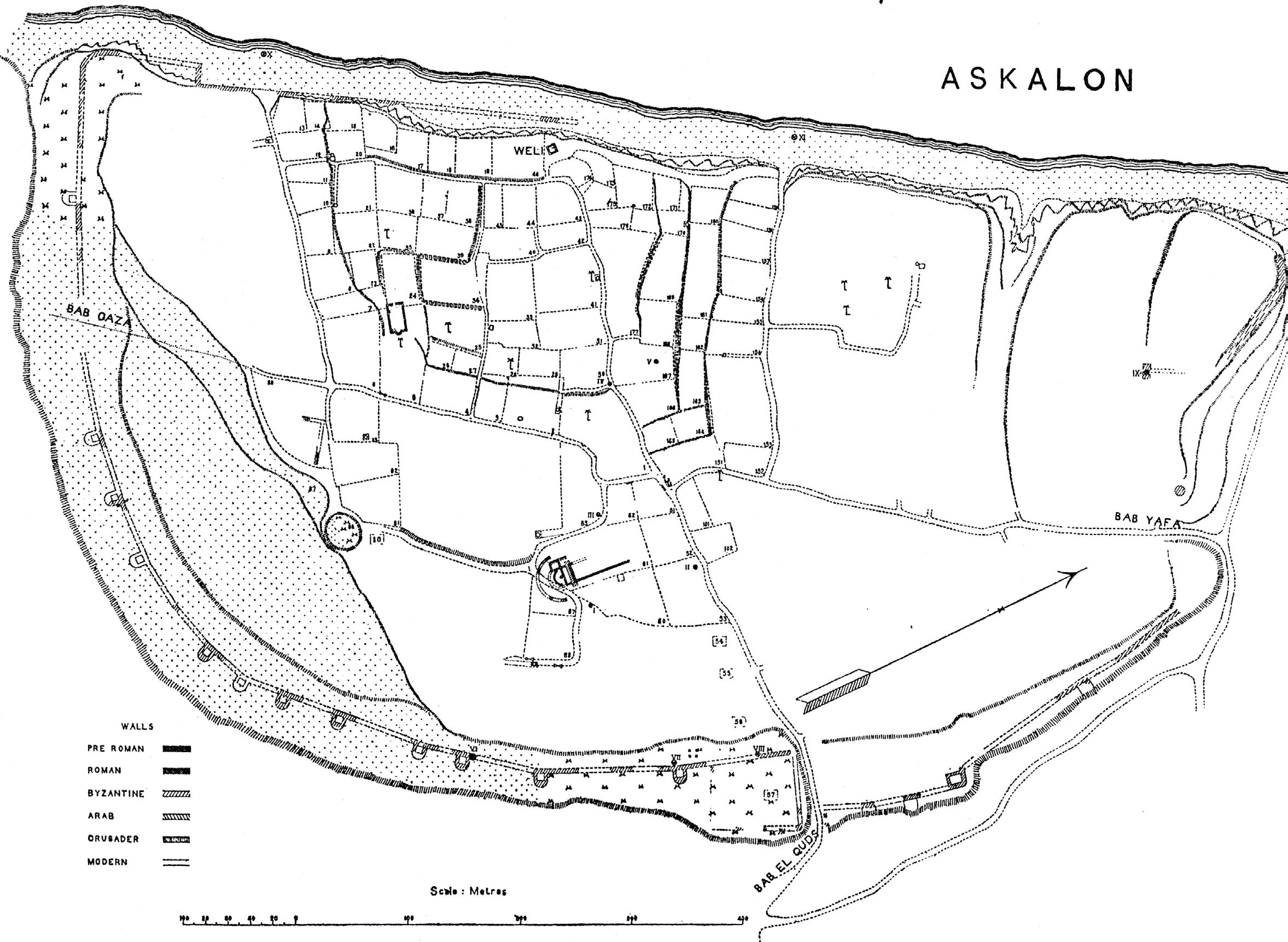

Estendendosi nell’entroterra, l’originaria Ashkelon assume una configurazione a semicerchio, il cui diametro corrisponde alla fascia a contatto con il mare mentre l’arco è definito dalle antiche fortificazioni che seguono la conformazione del terreno caratterizzata in alcune aree dalla presenza delle creste di kurkar. Queste dune di arenaria locale sono state create da sabbie di epoca preistorica provenenti da quello che poi diventerà il Delta del Nilo. Tali dune di sabbia hanno successivamente sepolto il canale fluviale preistorico che, partendo dalla sua falda acquifera delle colline ad est, trasporta acqua dolce fino alle spiagge di Ashkelon.

La pressione dell’acqua dolce sotterranea che scorre da est impedisce al mare di rendere le acque sotterranee locali salmastre, come altrimenti accadrebbe lungo la riva. Il motivo della presenza di numerosi antichi pozzi che sono stati scoperti nell’area dell’antica città è perciò chiaro. Sfruttano tale peculiarità arrivando fino a quella sorgente d’acqua dolce, così prossima al mare. La disponibilità di abbondante acqua fresca era tale da rendere Ashkelon una vera e propria oasi.

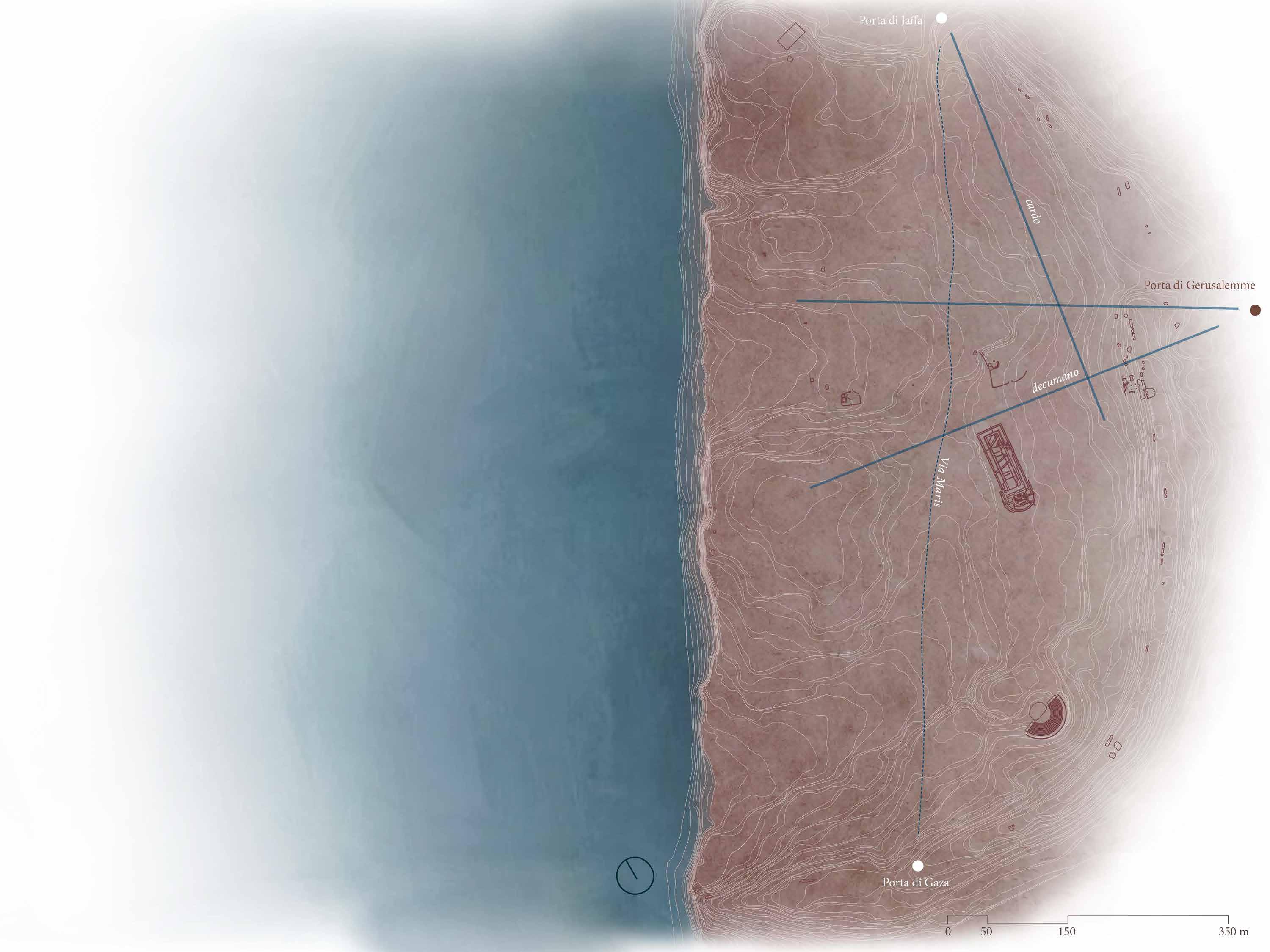

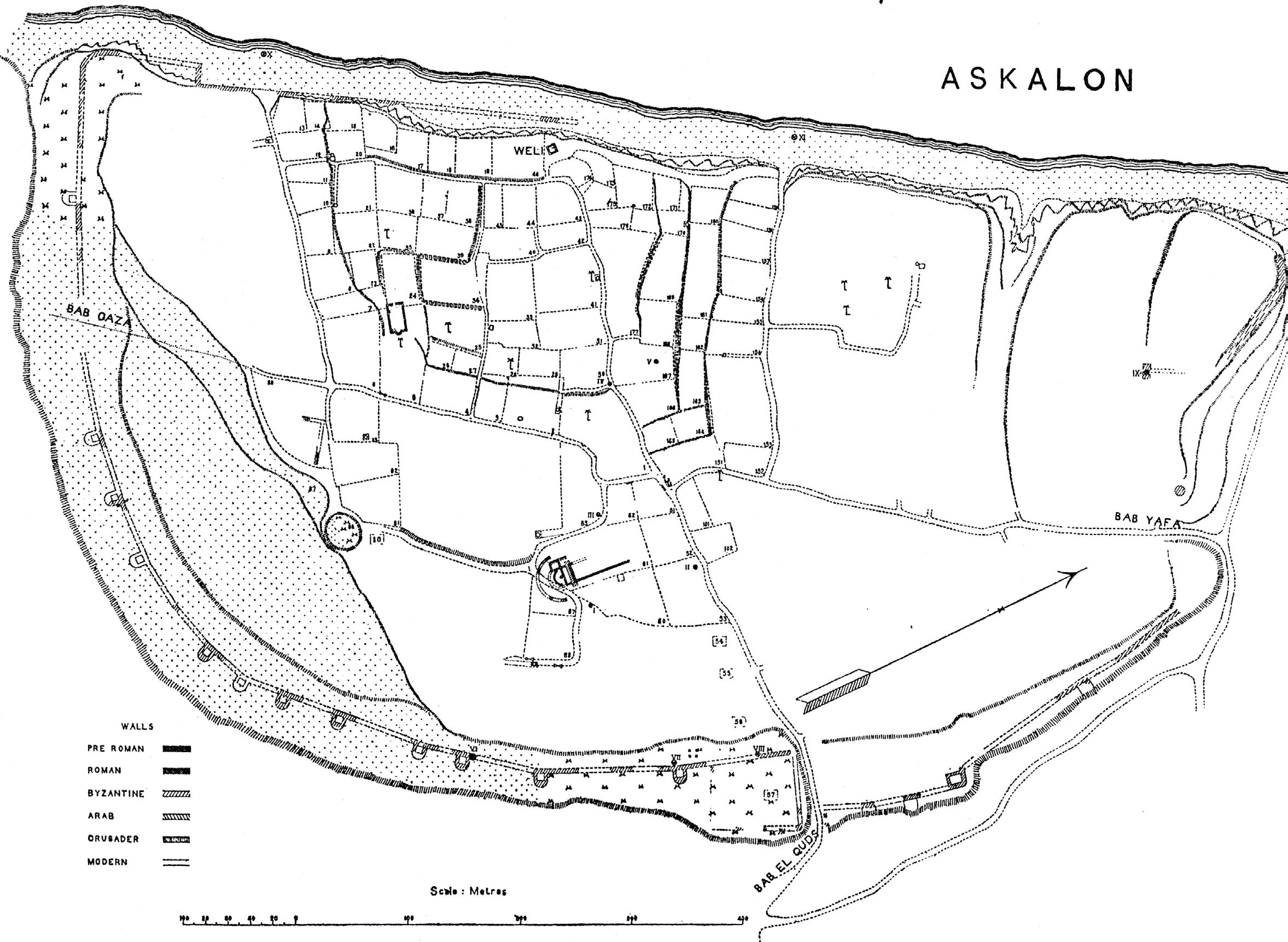

Lungo la cinta muraria a semicerchio, i cui resti sono ancora presenti, si dispongono le quattro porte della città : una di queste è la Porta di Gerusalemme (o Maggiore), chiamata così perché rivolta verso est, verso la Città Santa. La seconda è la Porta di Jaffa in direzione nord mentre a sud è presente la Porta di Gaza, entrambe rivolte verso le corrispondenti omonime città, entrambe collegate dalla via Maris

Si presume infine, che ci fosse anche il quarto accesso verso ovest, la cosiddetta Porta del Mare, ancora però oggetto di ricerca e discussione.

L’esatta posizione del porto difatti è ancora sconosciuta e probabilmente è variata nel corso dei secoli, ma nel muro sud-ovest a strapiombo sul mare sono presenti delle colonne di granito posizionate in orizzontale. Si suppone abbiano la funzione di rafforzare le pareti murarie dal momento in cui il porto ed il fronte mare hanno avuto un ruolo estremamente importante.

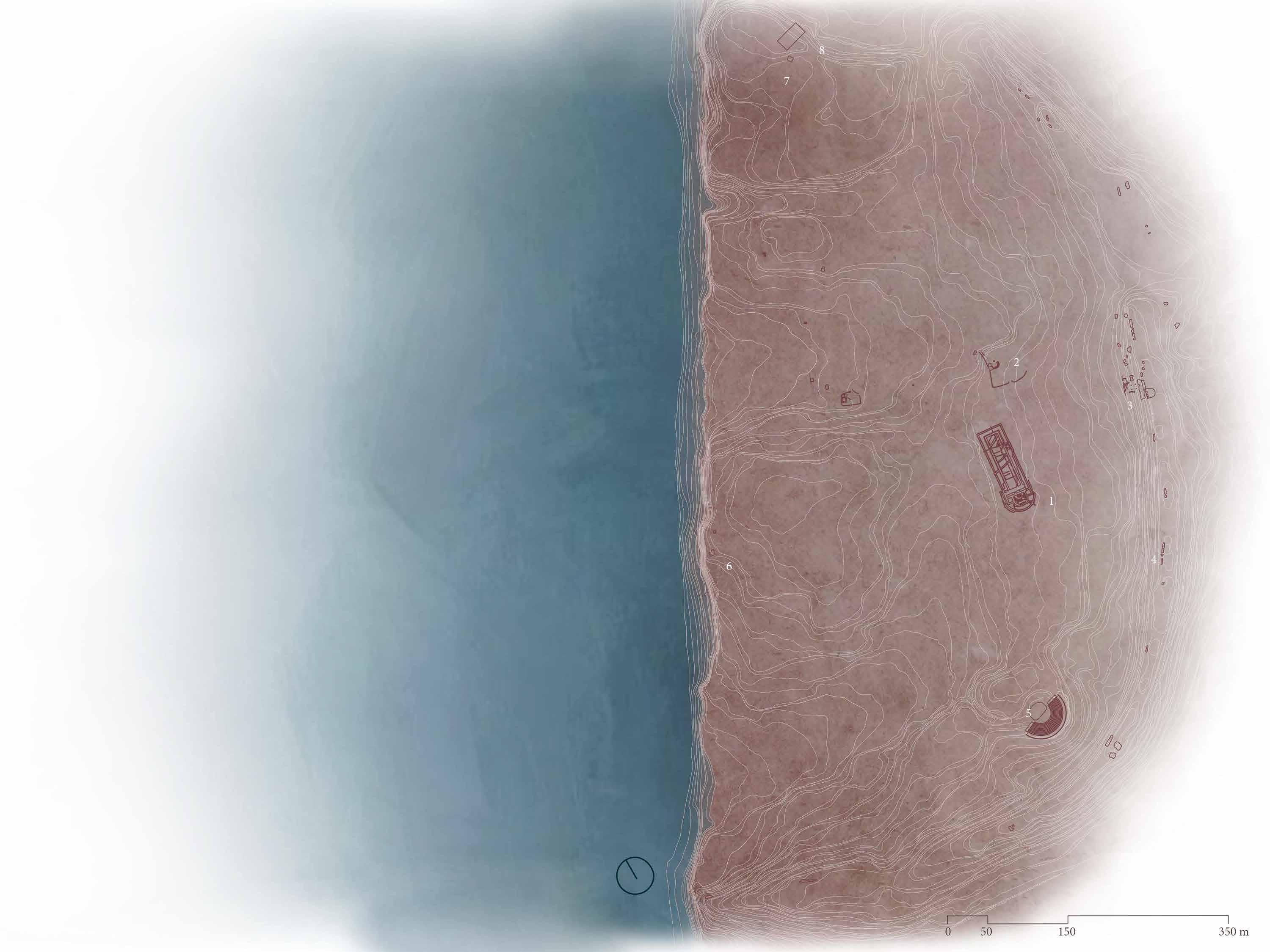

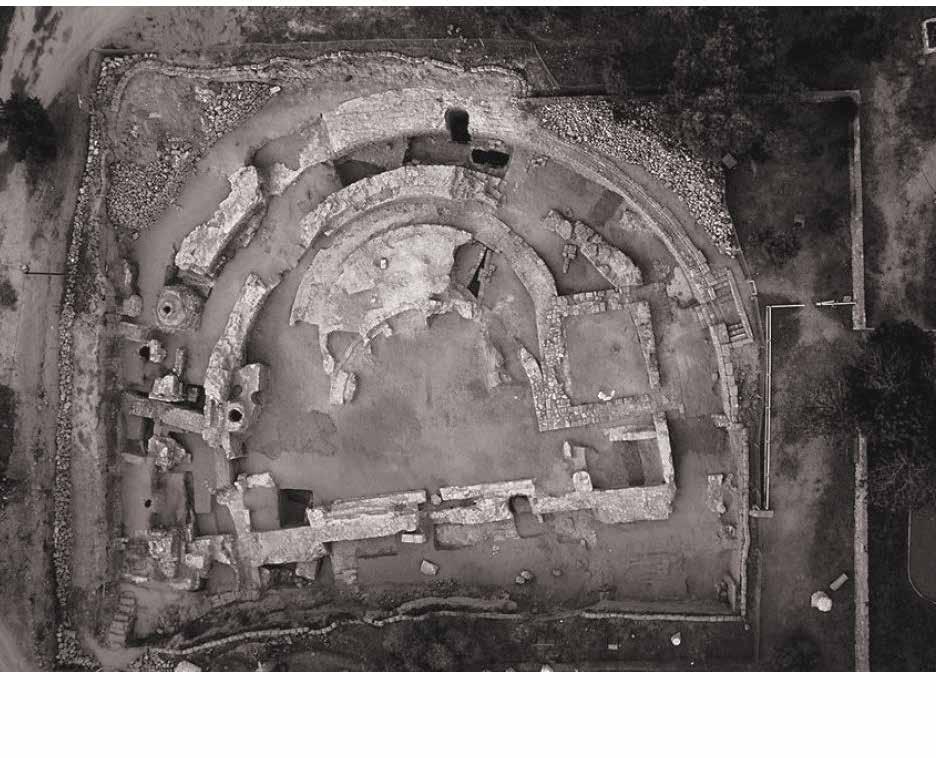

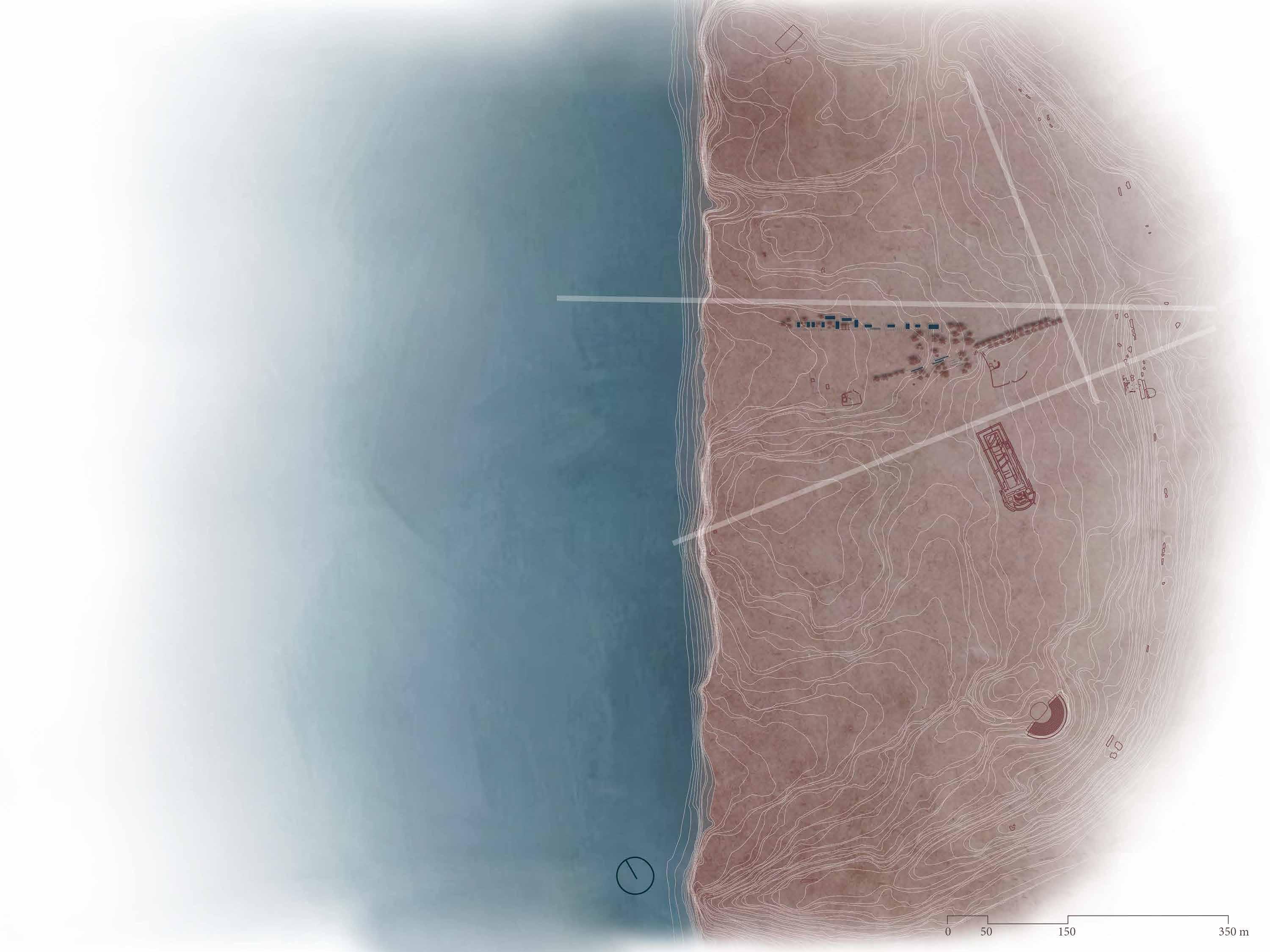

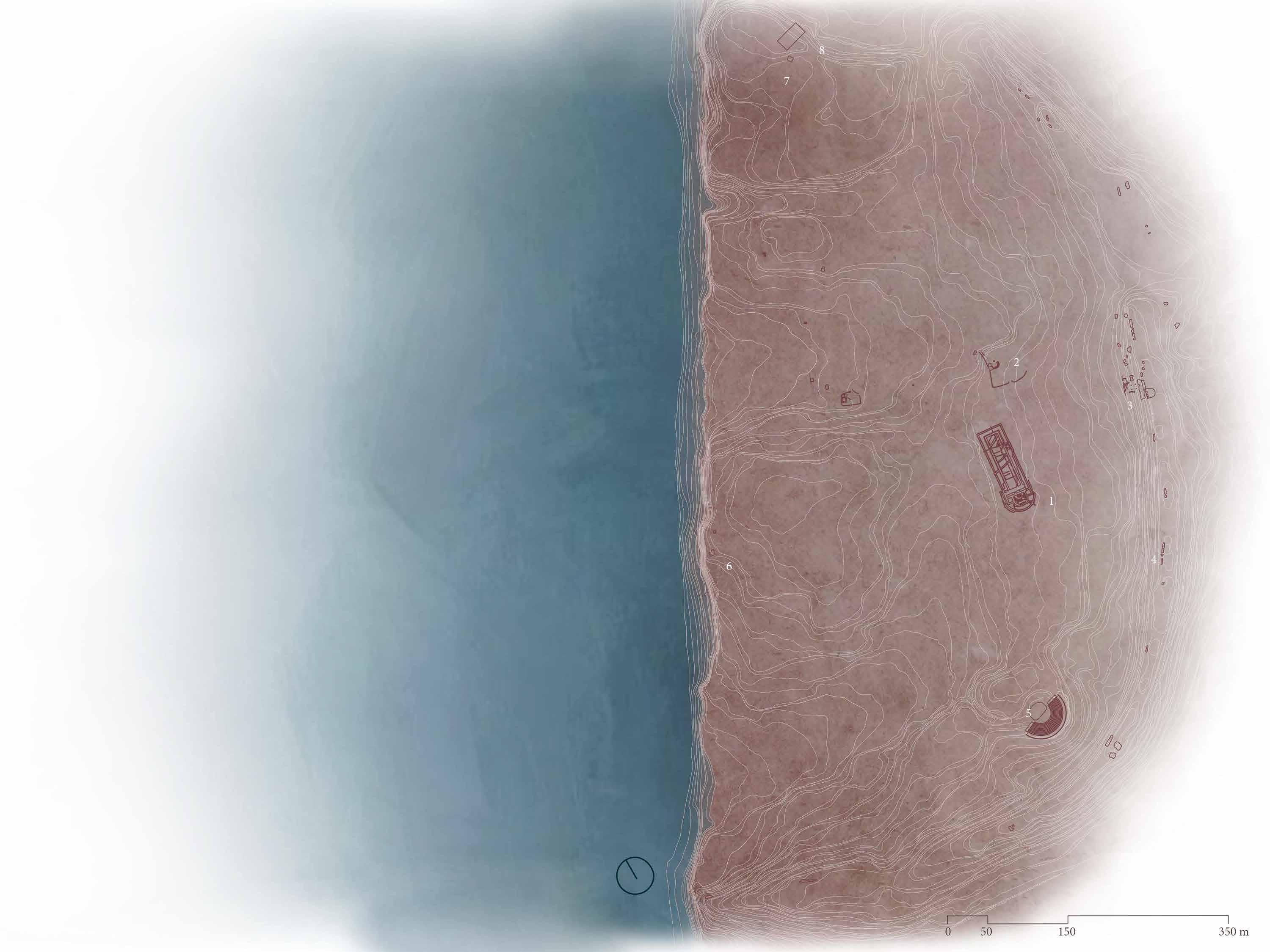

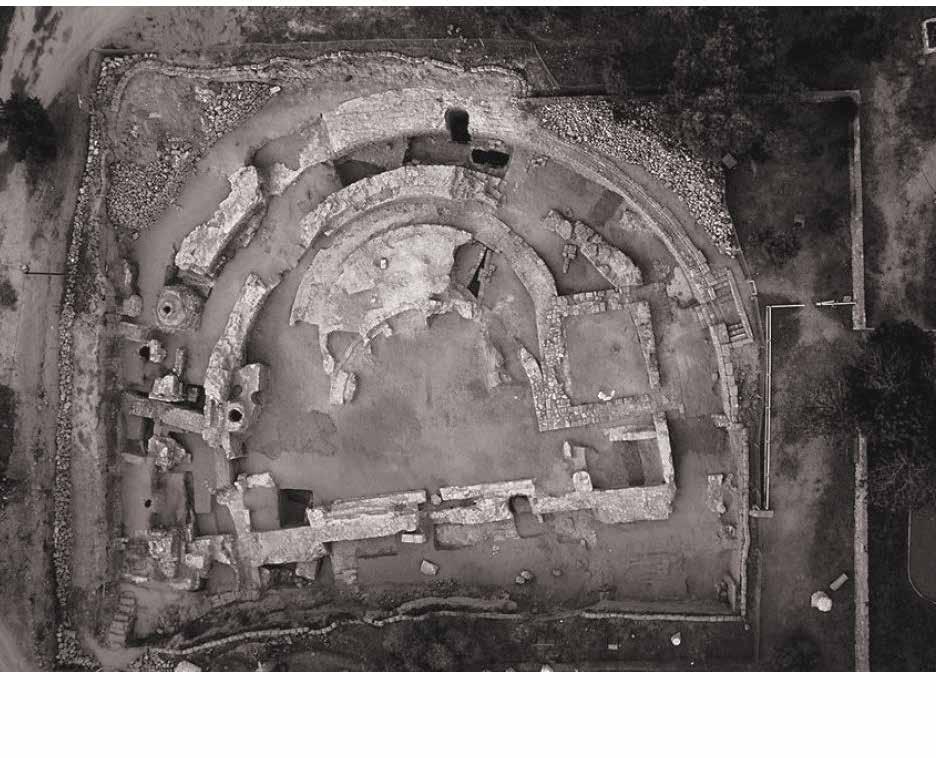

Oltre ai vari pozzi ed alcune parti della cinta muraria nel sito di Ashkelon, attualmente sono visibili resti archeologici ed architettonici presenti in maniera diffusa in tutta l’area, nella quale si possono identivifare due zone principali denominate North Tell e South Tell. Durante le spedizioni archeologiche il sito è stato ideologicamente diviso in aree di lato 100mx100m, permettendo una migliore localizzazione e catalogazione dei reperti. Tra i ritrovamenti arrivati fino ai nostri giorni emergono i resti della struttura colonnata di una Basilica, indicativamente al centro di tale griglia, ad est la Chiesa detta di S. Maria Viridis ed il Teatro di epoca romana, mentre ad ovest alcuni ruderi di ambienti voltati. L’immagine zenitale ha facilitato lo studio del tessuto urbano, del quale si può notare la somiglianza con l’impianto architettonico di Cesarea (Israele), anch’essa città portuale che si trova più a nord, a 42 km da Haifa, affacciandosi sul Mediterraneo. Le analogie tra queste due città si possono trovare già dalla cinta muraria dove è possi-

Mediterranean matrix

The original Ashkelon assumes a semicircle configuration extending inland, and its diameter corresponds to the belt in contact with the sea, while the arc is defined by the ancient fortifications that follow the conformation of the land, characterised in some areas by the presence of kurkar ridges. These dunes of local sandstone were created by prehistoric sands, from what later became the Nile Delta. At a later time, these sand dunes buried the prehistoric river channel that carries fresh water from its aquifer in the east ernhills to the beaches of Ashkelon. The pressure of fresh underground water flowing from the east prevents the sea from making the local groundwater brackish, as would otherwise happen along the shore. The reason why numerous ancient wells have been discovered in the area of the ancient city is therefore clear. They exploited this peculiarity by reaching that freshwater spring, so close to the sea. The availability of abundant fresh water was such that Ashkelon became a true oasis.

Along the semicircular city wall, whose remains are still present, are the four city gates: one of these is the Jerusalem Gate (or Major), so called because it faces east, towards the Holy City.

The second is the Jaffa Gate facing north, while to the south is the Gaza Gate, both facing the corresponding cities of the same name, both connected by the Via Maris. Finally, it is assumed that there was also a fourth access to the west, the so-called Porta del Mare (Sea Gate), which is still the

subject of research and discussion. The exact position of the port is still unknown and has probably varied over the centuries. But, overhanging the sea in the south-west wall, there are some granite columns with a horizontal position. They are supposed to have the function of reinforcing the walls, since the port and the waterfront played an extremely important role.

In addition to the various wells and parts of the wall in the Ashkelon site, archaeological and architectural remains can currently be seen scattered throughout it. Two main areas called North Tell and South Tell can be identified. During archaeological expeditions, the site was ideologically divided into areas of 100mx100m, allowing for a better localisation and cataloguing of the finds.

Among the archeological ruins that have survived to the present day are the remains of the columned structure of a Basilica, approximately in the centre of this grid, in the eastern part of the Church of S. Maria Viridis and the Roman theatre, and in the west part some ruins of vaulted spaces.

The aerial photograph facilitated the study of the urban structure, in which it is possible to note the similarity with the architectural layout of Caesarea (Israel), also a port city located further north, 42 km from Haifa, overlooking

13

pagina precedente / previous page Le rovine della chiesa di Santa Maria in Virdis e le mura retrostanti. | The remains of the Santa Maria in Virdis and the walls behind. (photo: Denys Pringle, 2009)

bile notare in entrambe, la conformazione a semicerchio delle fortificazioni. Assumendo un’impostazione binata, raddoppiandone il tracciato. Un’area che viene identificata per il suo ruolo difensivo viene così definita, all’interno della quale vengono localizzate varie attività funzionali inserendo il teatro, lo stadio e l’anfiteatro. Più a nord di Cesarea precisamente nella città di Akko (Israele) si riscontra il medesimo impianto binato che ne determina al suo interno la presenza di un fossato.

Proseguendo questa lettura per analogie, possiamo arrivare a identificare quella matrice mediterranea secondo la quale il popolo romano organizzava il fronte mare nell’area mediterranea del Medio Oriente.

Confrontando tra loro Ashkelon e Cesarea si evince la dislocazione delle strutture pubbliche come la Basilica e l’area del Foro come fattore comune, seguendo l’orientamento cardo-decumano solo però nel caso della seconda località. Per quanto riguarda invece Ashkelon, la disposizione sembra discordare rispetto agli assi che sono stati identificati come Cardo e Decumano.

Lo sfarzo delle rovine e le imponenti fortificazioni ci lasciano intendere la posizione dell’antica Ashkelon come una città molto potente, ricchezza generata grazie alla strategica posizione sul Mar Mediterraneo, e quindi ad uno sviluppo commerciale molto potente, assieme ad un terreno estremamente fertile che ha permesso un’agricoltura abbondante.

La fertilità ed il prestigio economico per le attività mercantili della città si ritrovano nel suo nome, che riferendosi alla radice della parola shekel, indica l’unità di peso e l’antica e moderna valuta ufficiale israeliana. La medesima parola diventa identificazione dello scalogno, una delle varietà di allium, lì coltivato ed esportato in tutto il Medi-

terraneo. Inoltre, altre piantagioni occupavano il terreno fertile di Ashkelon, tra cui gli ulivi, il fumento e molte piante medicinali e da frutto. Il clima è difatti ottimo per la cereagricoltura, frutticoltura e agrumicoltura.

La ricca vegetazione e l’affaccio sul Mar Mediterraneo garantivano l’indipendenza e l’egemonia della città nella pianura litorale palestinese.Secondo Claude Conder, uno degli autori della monumentale ottocentesca Survey of Western Palestine, che aveva calpestato la maggior parte del nazione: “Ascalon è uno dei luoghi più fertili della Palestina. Le grandi mura, che sono ben descritte da William di Tiro come un arco con la corda al mare, racchiude uno spazio di cinque ottavi di miglio a nord e sud, di tre ottavi di profondità.

Il tutto è pieno di ricchi giardini, e non meno di trentasette pozzi di acqua dolce esistono all’interno delle mura, mentre a nord, per quanto lontano come il villaggio, altri giardini e altri pozzi saranno trovati. L’intera stagione sembrava più avanzata in questo angolo riparato che sulla pianura più esposta. Le palme crescono in numero; i mandorli e limoni, il tamerice e il fico d’India, le olive e la vite, con ogni tipo di verdura e mais, già nella spiga, fioriscono in tutta l’estensione dei giardini all’inizio di aprile. Solo a sud le grandi onde di sabbia sempre invadente ha ora sormontato le fortificazioni e spazzò giardini un tempo fecondi, minaccioso in tempo per fare tutto un deserto sabbioso, a meno che non si trovino i mezzi per arrestarne il progresso.”

(Conder ,1875)

the Mediterranean Sea. The similarities between these two cities can already be found in the city walls where it is possible to note in both the semicircular conformation of the fortifications. Doubling the line it takes a twin layout.

An area that is identified for its defensive role is thus defined, within which various functional activities are located by inserting the theatre, the stadium and the amphitheatre. More northerly of Caesarea, in the city of Akko (Israel), the same twin layout can be found. Which determines the presence of a moat within it.

Proceeding this analysis by analogy, we can identify that Mediterranean matrix, according to which the Roman people organised the seafront in the Mediterranean area of the Middle East.

Comparing Ashkelon and Caesarea shows the dislocation of public buildings such as the Basilica and the Forum area as a common factor, following the cardo-decuman orientation only in the case of the latter location. As for Ashkelon, on the other hand, the layout seems to deviate from the axes that have been identified as Cardo and Decumanus

The magnificence of the ruins and the massive fortifications suggest the position of ancient Ashkelon as a very powerful city, its prosperity generated by its strategic location on the Mediterranean Sea, and thus by a very powerful commercial development, combined with an extremely fertile soil that provided abundant agriculture. The fertility and economic prestige for the city’s mercantile activities are reflected in its name, which indicates the unit of weight and the ancient and modern official Israeli currency. Referring to the root of the word shekel

The same word became the identification of the shallot, one of the varieties of allium, cultivated there and ex-

ported throughout the Mediterranean. Moreover other plantations filled Ashkelon’s fertile soil, including olive trees, wheat and many medicinal and fruit plants. In fact the climate is excellent for cereal, fruit and citrus cultivation.

The rich vegetation and the overlooking of the Mediterranean Sea guaranteed the city’s independence and hegemony in the Palestinian coastal plain. According to Claude Conder, one of the authors of the monumental nineteenth-century Survey of Western Palestine, who had travelled through most of the nation:

“Ascalon is one of the most fertile spots in Palestine. The great walls, which are well described by William of Tyre as a bow with the string to the sea, enclose a space of five-eighths of a mile north and south, by threeeighths deep. The whole is filled with rich gardens, and no less than thirty-seven wells of sweet water exist within the walls, whilst on the north, as far as the village, other gardens and more wells are to be found. The whole season seemed more advanced in this sheltered nook than on the more exposed plain. Palms grow in numbers; the almond and lemon-trees, the tamarisk and prickly pear, olives and vines, with every kind of vegetable and corn, already in the ear, are flourishing throughout the extent of the gardens early in April. Only on the south the great waves of ever-encroaching sand have now surmounted the fortifications and swept over gardens once fruitful, threatening in time to make all one sandy desert, unless means can be found to arrest its progress.”

(Conder, 1875)

15

Veduta aerea degli scavi della Basilica |Aerial view of the excavations of the Basilica (2012)

Mappa di Madaba Madaba map

La storia della città di Ashkelon, determinata dalla molteplicità di interazioni culturali, è estremamente ricca di eventi e di popolazioni che si sono succedute ed influenzate a vicenda, determinando un tessuto urbano ed impianto architettonico specifico. Essendo dunque una città ricca di storia, un qualsiasi progetto nell’area più a diretto contatto con il suo passato non può astenersi dal confronto con l’antica Ashkelon.

La lettura storica, quella geografica ed archeologica forniscono alcune fonti scritte che spesso e volentieri non sono state troppo esaurienti in merito all’impostazione urbana. Tuttavia, il confronto con le raffigurazioni della città all’interno delle antiche carte è stato un’importante analisi che ha permesso una diversa interpretazione della conformazione di Ashkelon.

Due carte in particolare sono state prese come riferimento per metodo di indagine precedentemente descritto:

la Tabula Peuntingeriana per il periodo romano, mentre durante il periodo medievale la Mappa di Madaba

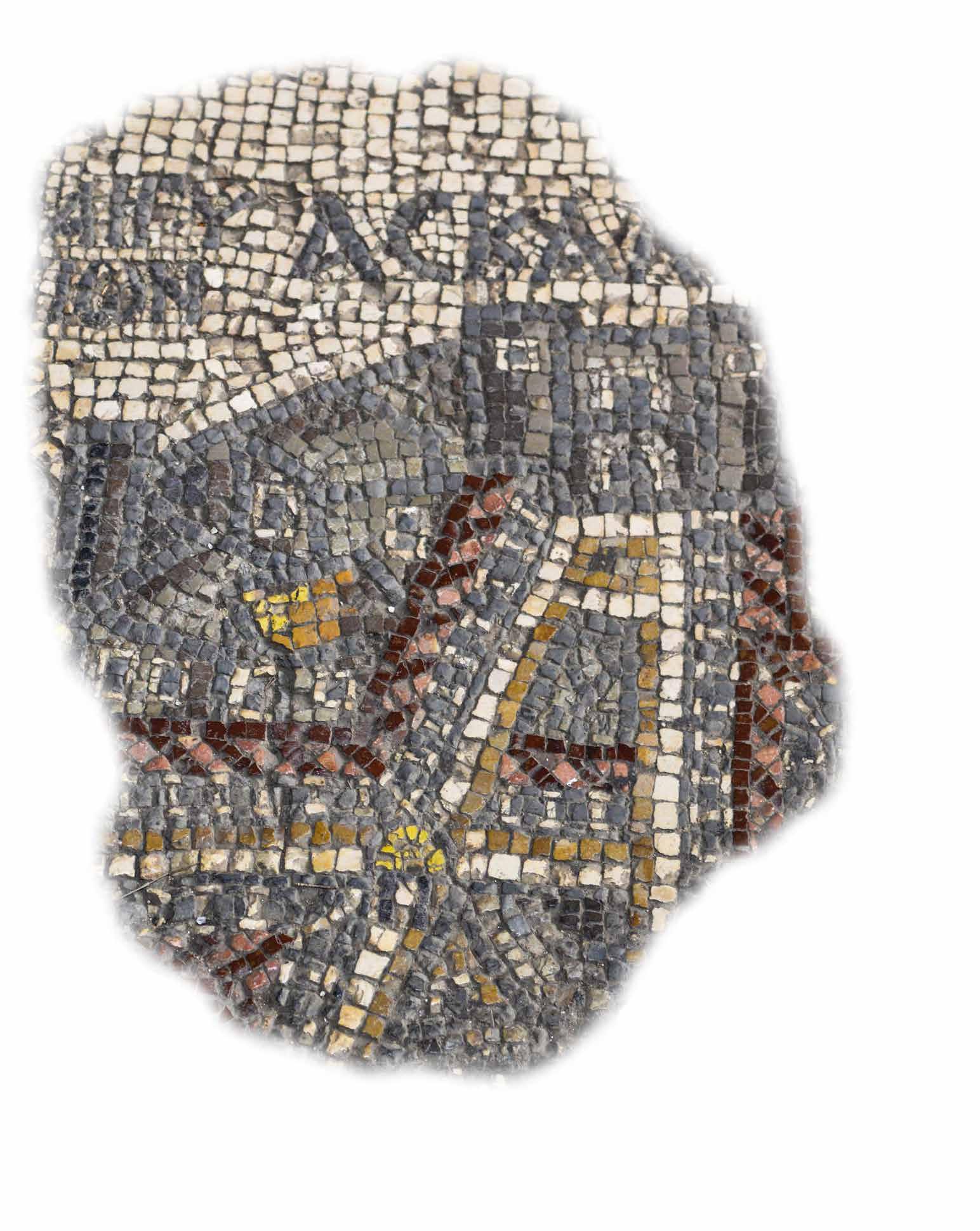

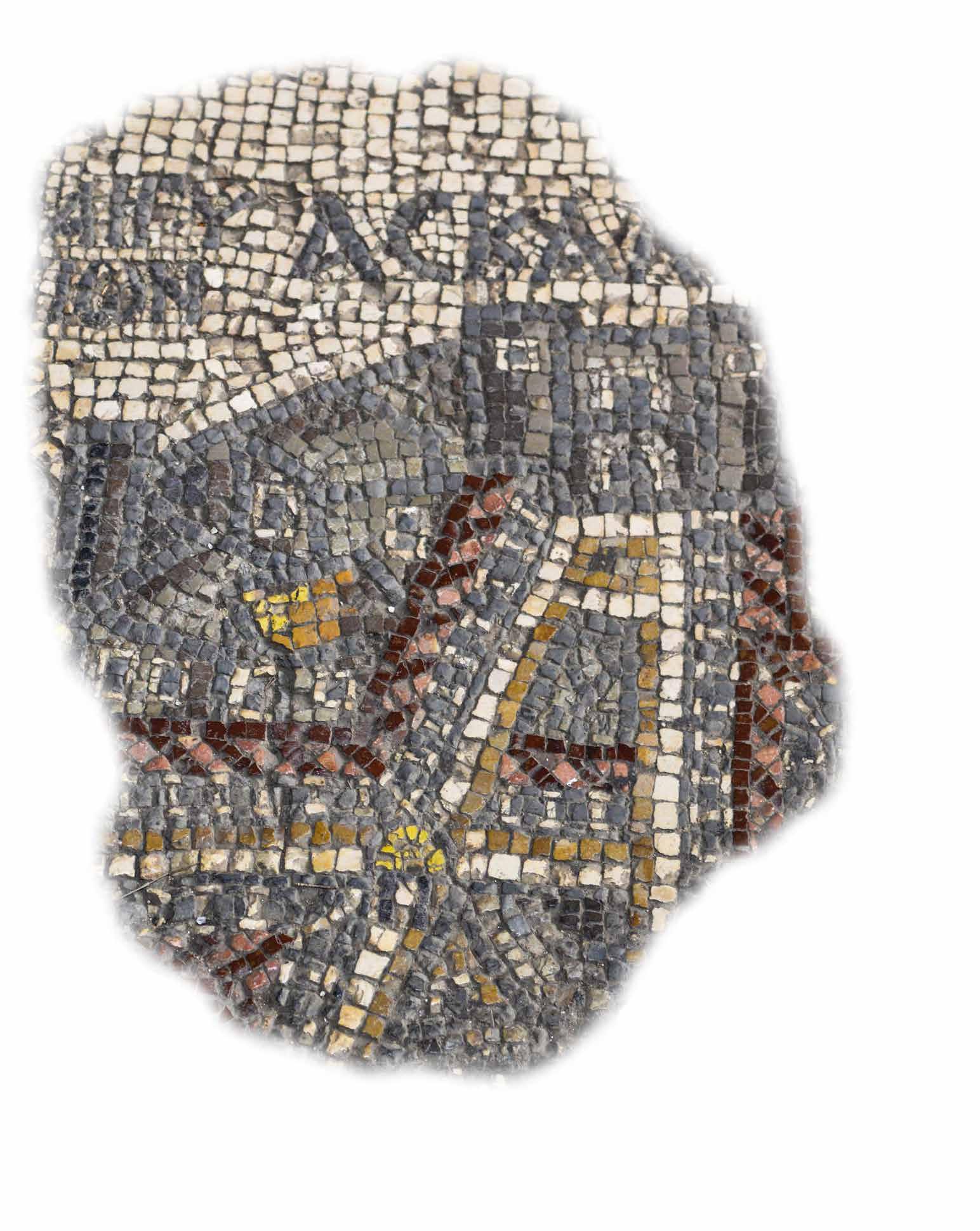

La Mappa di Madaba è un frammento di un mosaico pavimentale risalente al VI sec d.C che si trova nella chiesa bizantina di San Giorgio, nella città giordana di Madaba. E’ una mappa del Medio Oriente che viene considerata una delle rappresentazioni più affidabili di

‘Tabulae’ lontane Long gone ‘tabulae’

quel periodo, principalmente per la descrizione della Gerusalemme di epoca adrianea, ma anche di tanti altri siti biblici e luoghi sacri tra i quali anche Ashkelon.

La città viene descritta attraverso una vista dall’alto dove è riconoscibile la porta turrita di Gerusalemme leggermente in scorcio, dalla quale il decumano si biforca fino ad arrivare al fronte mare. Il Cardo invece di proseguire oltre l’intersezione con il Decumano s’interrompe all’altezza della Basilica, fermando anche la parte colonnata che prosegue verso ovest individuando uno scarto.

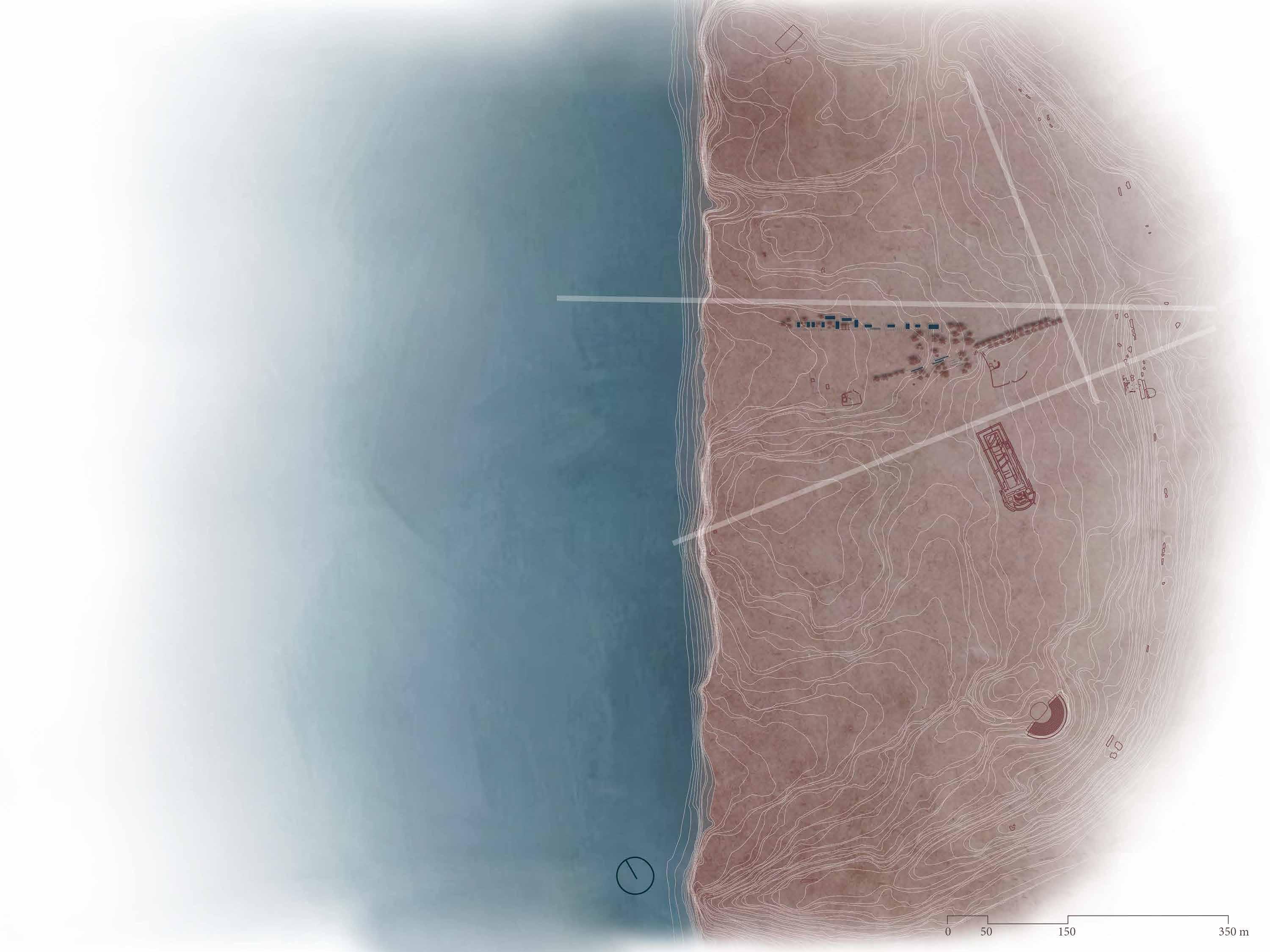

Attualmente attraverso una vista zenitale sono facilmente riconoscibili i due assi viari: uno est-ovest mentre l’altro in direzione nord-sud corrisponde alla via Maris, la strada commerciale parallela al mare che collega la Porta di Jaffa con quella di Gaza. Sovrapponendo ed orientando correttamente l’immagine aerea e la rappresentazione della Mappa di Madaba , ci si accorge che gli assi del cardo e del decumano coincidono con l’orientamento della Chiesa Bizantina, che succede alla Basilica romana.

La biforcazione del Decumano definisce un’area trapezoidale verso il fronte mare che, date le sue caratteristiche, potrebbe corrispondere al sito dell’antico porto di Ashkelon.

The history of the city of Ashkelon, is extremely rich in events and populations that have succeeded and influenced each other. It has been determined by the multiplicity of cultural interactions, resulting in a specific urban structure and architectural system. Therefore, as a city rich in history, any project in the area in direct contact with its past cannot avoid confrontation with the ancient Ashkelon. The historical, geographical and archaeological studies provide a number of written sources that have often been less than comprehensive regarding the urban confromation. However, comparing the representations of the city within ancient maps was an important analysis that allowed for a different interpretation of Ashkelon’s structure.

Two maps in particular were taken as reference for the survey method described above: the Tabula Peuntingeriana for the Roman period, and the Map of Madaba for the medieval period. The Map of Madaba is a fragment of a floor mosaic dating from the 6th century AD found in the Byzantine Church of St George in the Jordanian city of Madaba. It is a map of the Middle East that is considered one of the most trustworthy representations of that period. Mainly for its description of Hadrian-era Jerusalem, but also of

many other biblical sites and holy places including Ashkelon.

The city is described through a view from above where the turreted gate of Jerusalem is recognisable slightly in foreshortening, from which the Decumanus bifurcates to the seafront. The Cardo is interrupted near the Basilica, also ending the columned part that continues westwards, instead of continuing beyond the intersection with the Decumanus, identifying a gap.

Currently, in an aerial view, the two road axes are easily recognisable: one east-west while the other, in a northsouth direction corresponds to the Via Maris, the trade road parallel to the sea that connects the Jaffa Gate with the Gaza Gate.

By accurately superimposing and orienting the aerial image and the representation of the Map of Madaba, it can be clearly seen that the axes of the Cardo and Decumanus coincide with the orientation of the Byzantine Church, which follows the Roman Basilica. The bifurcation of the Decumanus defines a trapezoidal area towards the waterfront that, considering its characteristics, may correspond to the site of the ancient port of Ashkelon.

pagina precedente / previous page Giordania, Illustrazione di Ashkelon nel mosaico pavimentale di Madaba | Jordan, Ashkelon illustrated on the Madaba mosaic map. (photo: Denys Pringle, 2016)

21

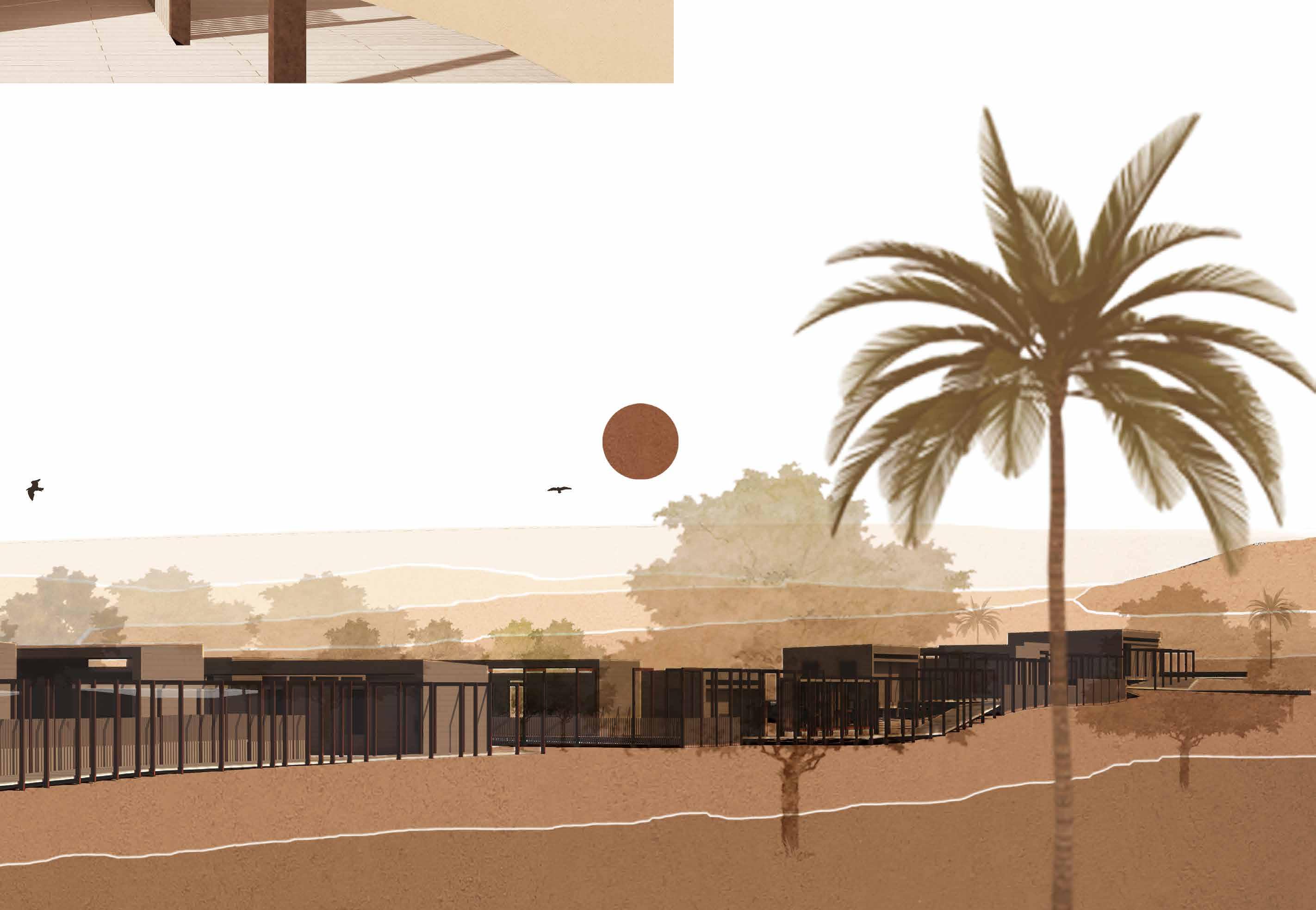

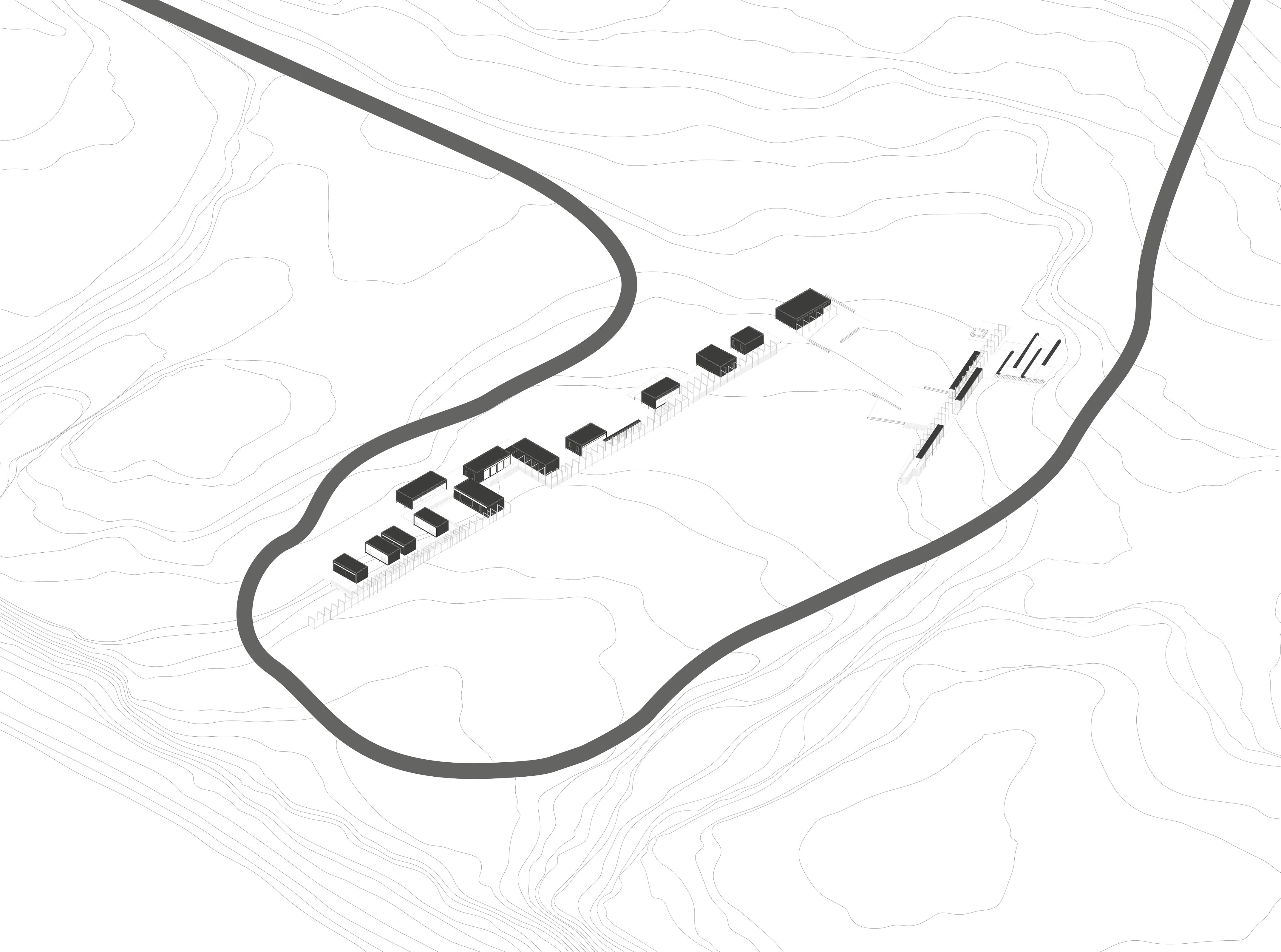

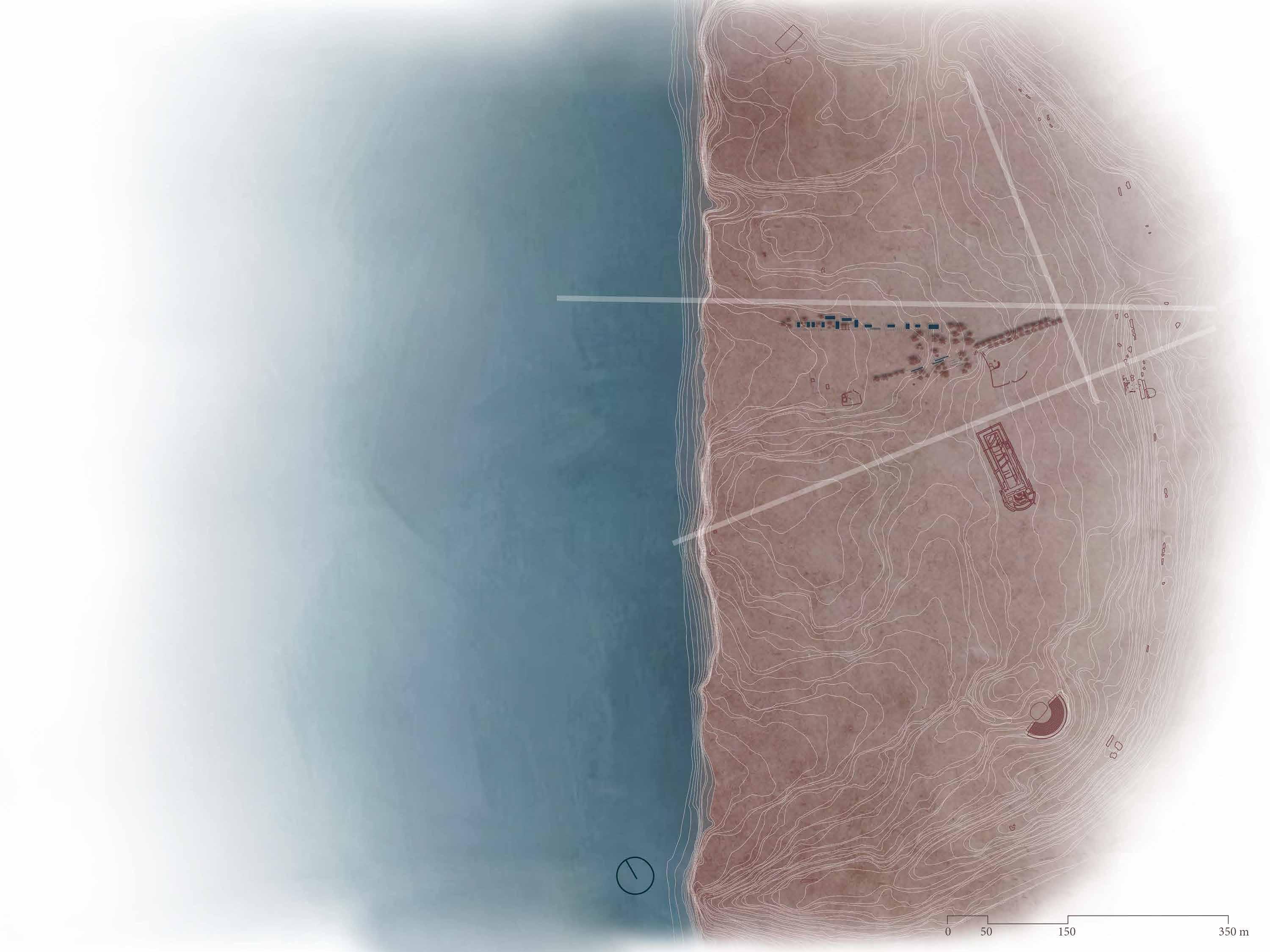

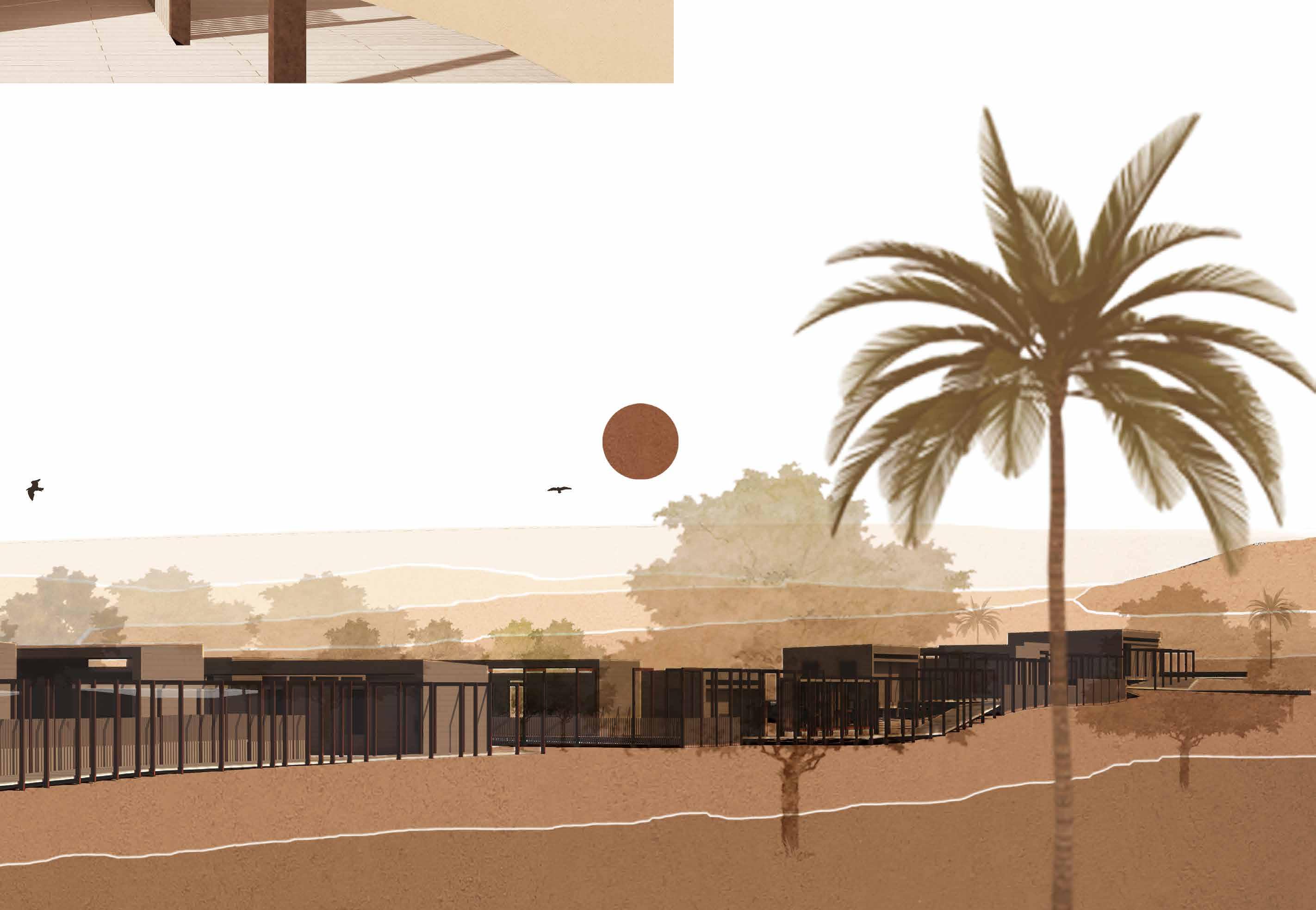

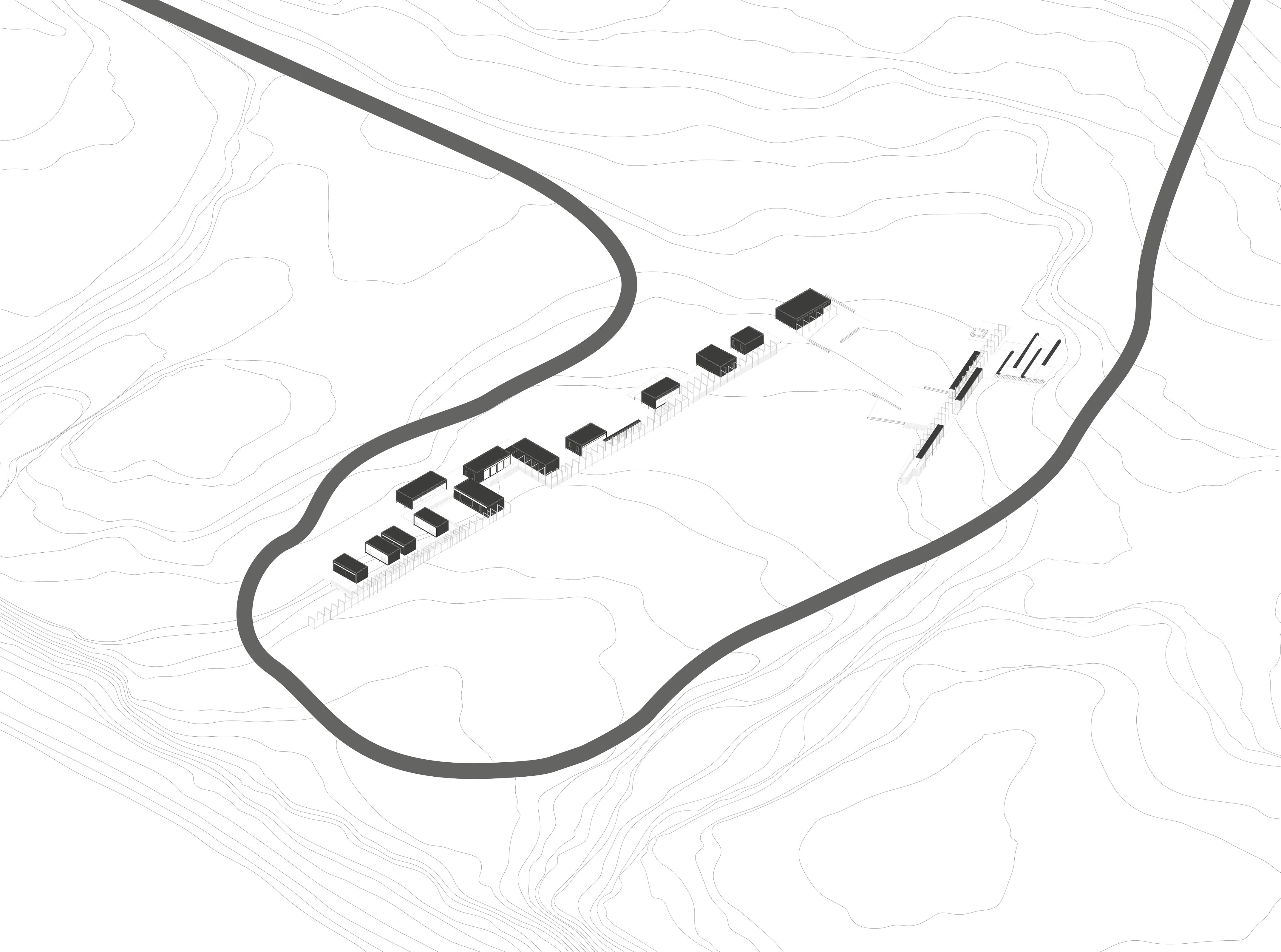

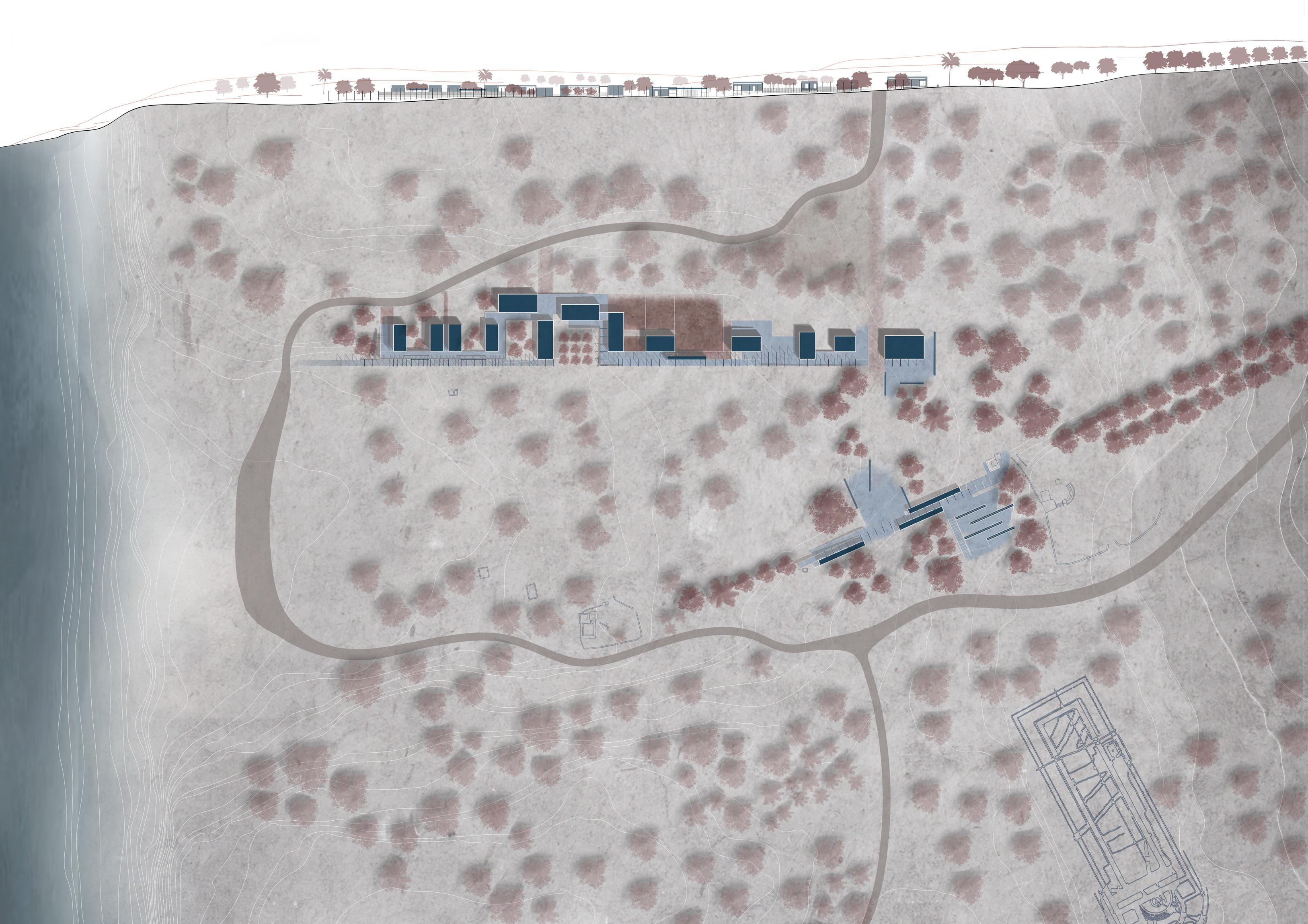

pagina precedente / previous page Vista dall’alto del progetto e relativo rapporto con il territorio. | Top view of the project and its relationship with the territory.

Segni di progetto | Design signs

Velato ricordo

L’incontro e la simbiosi del nuovo e l’antico definiscono una questione alquanto delicata, soprattutto in un sito archeologico dove questo contatto è estremamente diretto. L’archeologia convive con l’architettura funzionale del presente, necessaria per soddisfare le nuove esigenze e poter in questo modo vivere a pieno un luogo ricco di storia e civiltà.

Tale confronto e unione esprime la volontà di non voler lasciare in abbandono e nell’oblio frammenti di un passato più o meno recente con un inestimabile valore culturale, sia a livello artistico-architettonico sia storico ed etno-antropologico.

Valorizzare un sito archeologico implica la realizzazione di nuovi elementi che possano migliorare la qualità dell’esperienza del luogo, oltre a rendere più esplicativo l’approccio conoscitivo e culturale.

Nuove forme che neghino l’autoreferenzialità, tendendo verso un rispettoso dialogo e confronto con la storia.

Un’ interrelazione tra passato e presente.

Veiled remembrance

The meeting and symbiosis of the new and the old defines a rather delicate issue, especially on an archaeological site where this contact is extremely direct. Archaeology coexists with the functional architecture of the present, which is necessary to meet new needs and thus make the visitor fully experience a place so rich in history and culture.

This contrast and union expresses the desire not to allow fragments of a more or less recent past with an inestimable cultural value to be abandoned and forgotten, from an artistic-architectural as well as a historical and ethno-anthropological perspective.

Enhancing an archaeological site implies the realisation of new elements that can improve the quality of the experience of the place, as well as making the cognitive and cultural approach more explanatory.

New shapes that deny self-referentiality, tending towards a respectful dialogue and confrontation with history.

An interrelationship between the past and the present.

Il confronto con la raffigurazione della città di Ashkelon nelle antiche carte è stato uno dei fattori cardini per lo sviluppo del progetto, in particolare con la Mappa di Madaba

Il progetto di tesi vuole valorizzare l’area archeologica e dialogare con l’antica conformazione di Ashkelon, facendo proprio l’intento di ricostruire la memoria di Madaba senza però darne un’immagine compiuta.

Tale incompiutezza non vuole affermare l’impossibilità di nuove forme nei siti dove predomina il resto archeologico, ma l’impossibilità di ricostruire l’antico in tempi del presente.

Eredita dunque gli assi del Cardo e del Decumano, facendoli diventare linee direzionali lungo le quali si sviluppano

le varie componenti di progetto: come se fossero tessere di un mosaico incompiuto, in parte perso, del quale rimane solo un ricordo.

L’architettura diffusa così generata non assume mai una conformazione chiusa, perché non finita e continuamente in divenire, dove la reversibilità e un sistema funzionale aperto sono caratteristiche fondamentali del progetto in questione. La frammentarietà architettonica vuole far rinascere l’antica città attraverso non la ricostruzione, bensì però la sua memoria.

Un ricordo offuscato che, assimilato, genera nel presente quell’ordine antico incompiuto.

The comparison with the depiction of the city of Ashkelon in the ancient maps was one of the pivotal factors for the development of the project, in particular by the Map of Madaba

The thesis project aims to valorise the archaeological area and dialogue with the ancient conformation of Ashkelon, with the intention of reconstructing the memory of Madaba without giving it a completed image.

This incompleteness is not intended to affirm the impossibility of new shapes in sites where archaeological remains predominate, but the impossibility of reconstructing the ancient in the present time.

It therefore inherits the axes of the Cardo and the Decumanus , mak-

ing them into directional lines along which the various project components are developed: as if they were tiles of an unfinished mosaic, partly lost, of which only a memory remains.

The diffuse architecture thus generated never assumes a closed conformation, because it is unfinished and continually in evolving with reversibility and an open functional system as fundamental characteristics of the project in question. The architectural fragmentariness seeks to revive the ancient city not through reconstruction, but rather through its memory.

A blurred memory that, if assimilated, generates that unfinished ancient order in the present.

Vista del versante nord con fossato asciutto in primo piano. Sotto la tettoia si trova l’accesso nord dell’antica Ashkelon. |View of north slope with dry moat in foreground. Under the roof, one of city gates of the ancient Ashkelon.

Pianta dell’antica Ashkelon con la periodizzazione delle sue mura. | Plan of the ancient Ashkelon with the periodisation of its walls. (John Garstang, 1921)

25

Progetto Project

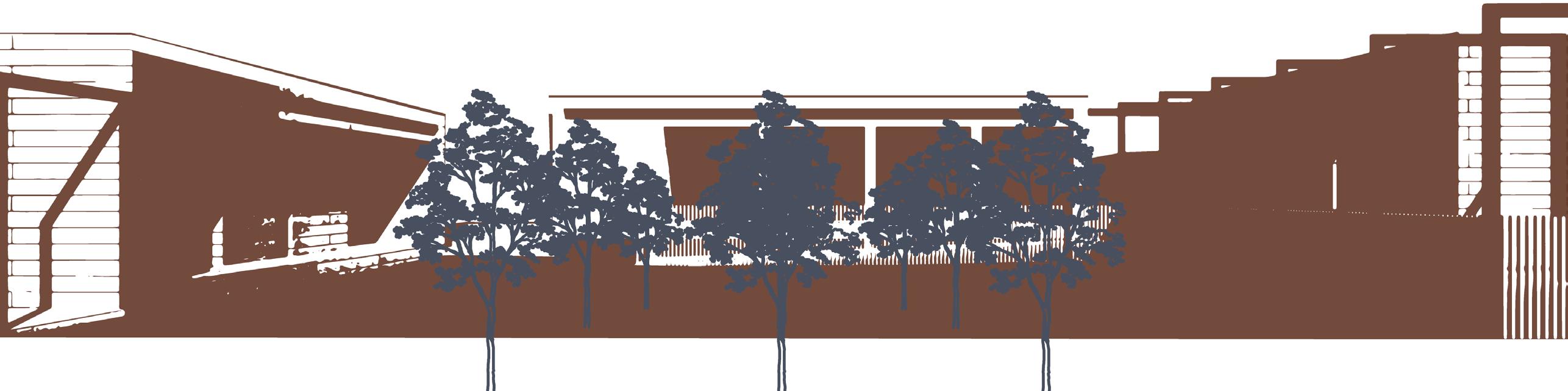

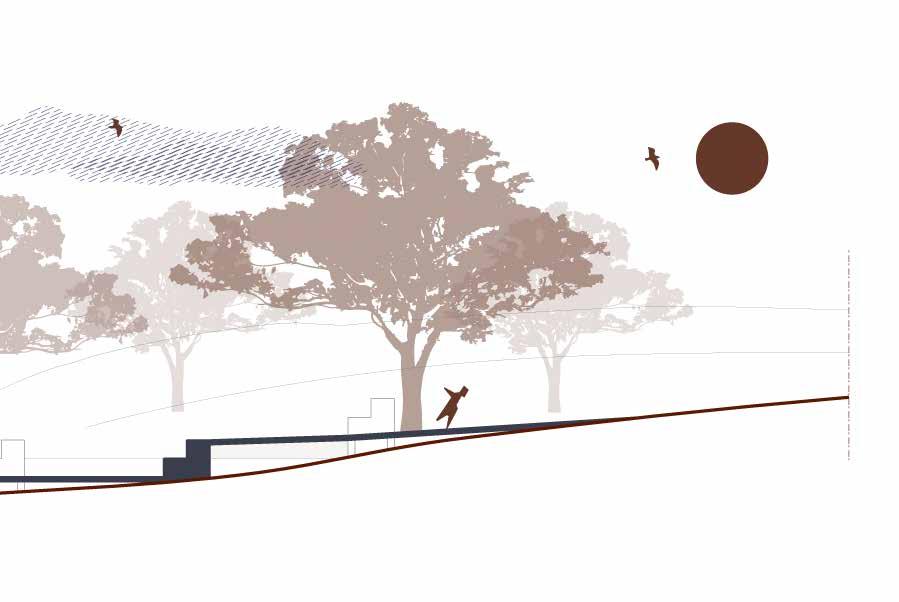

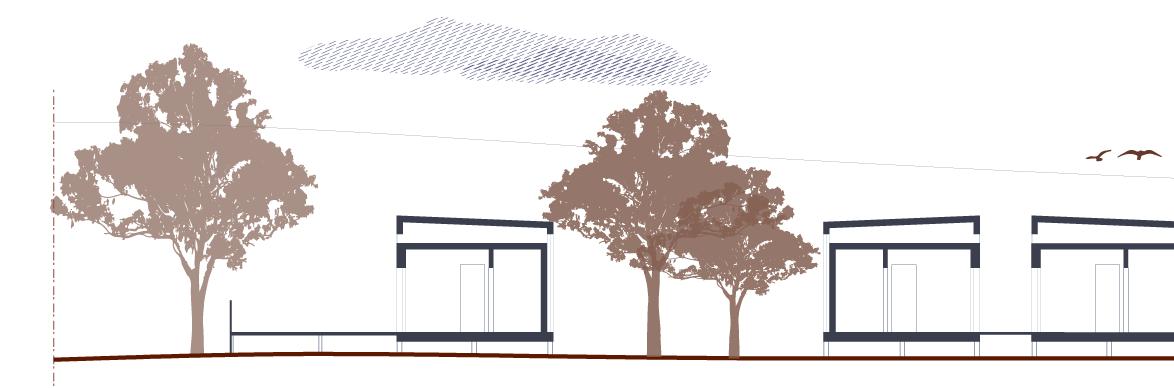

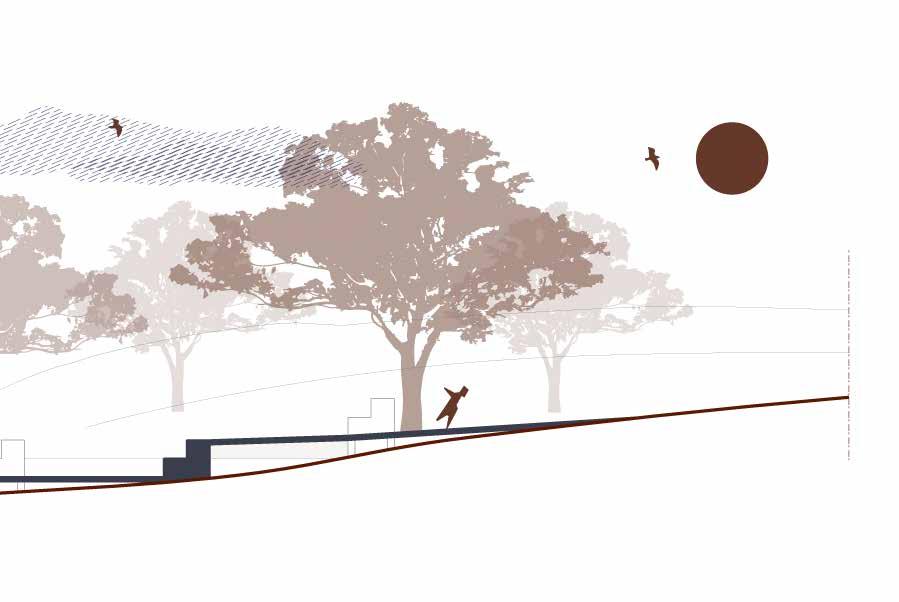

Sezione AA’

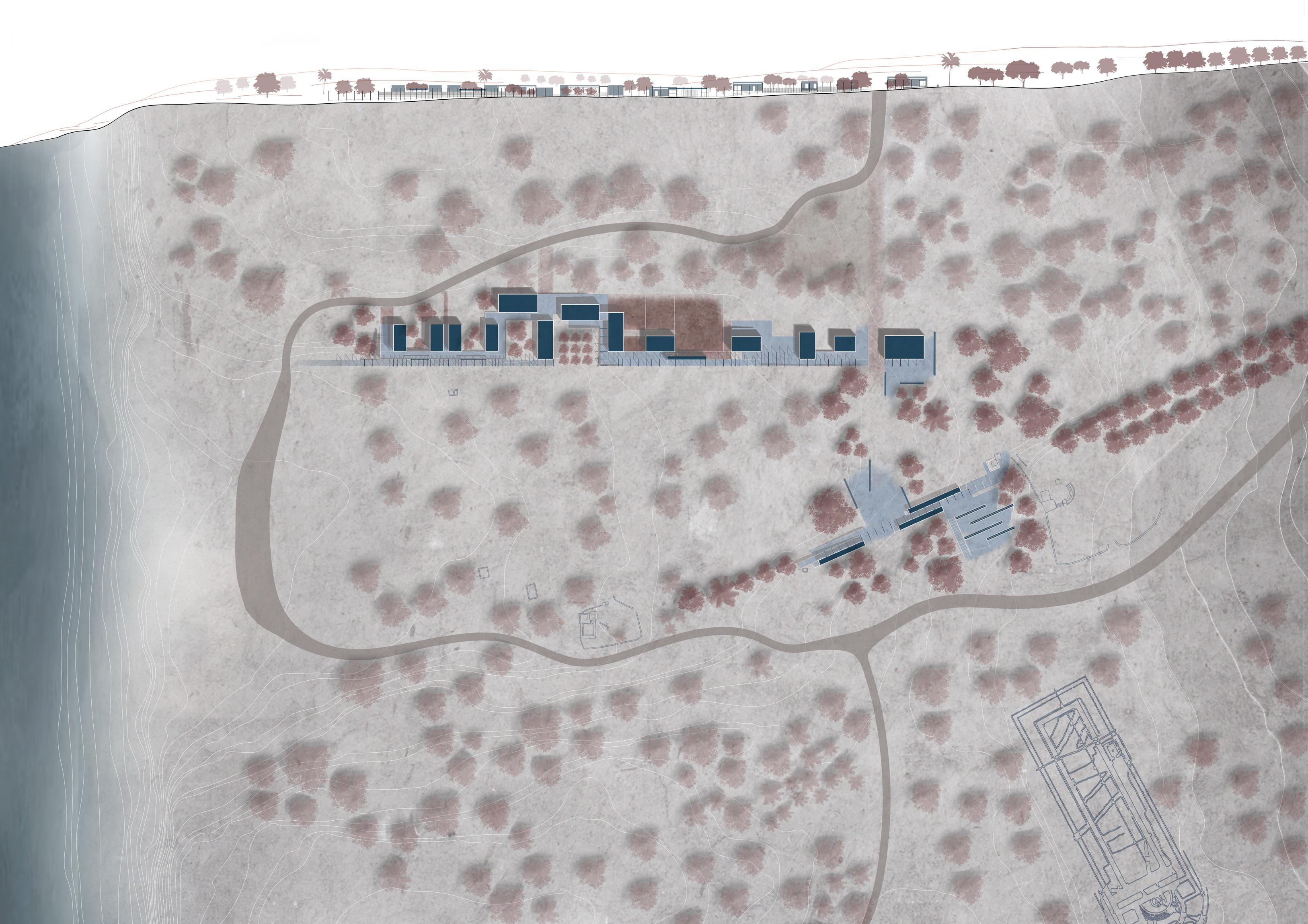

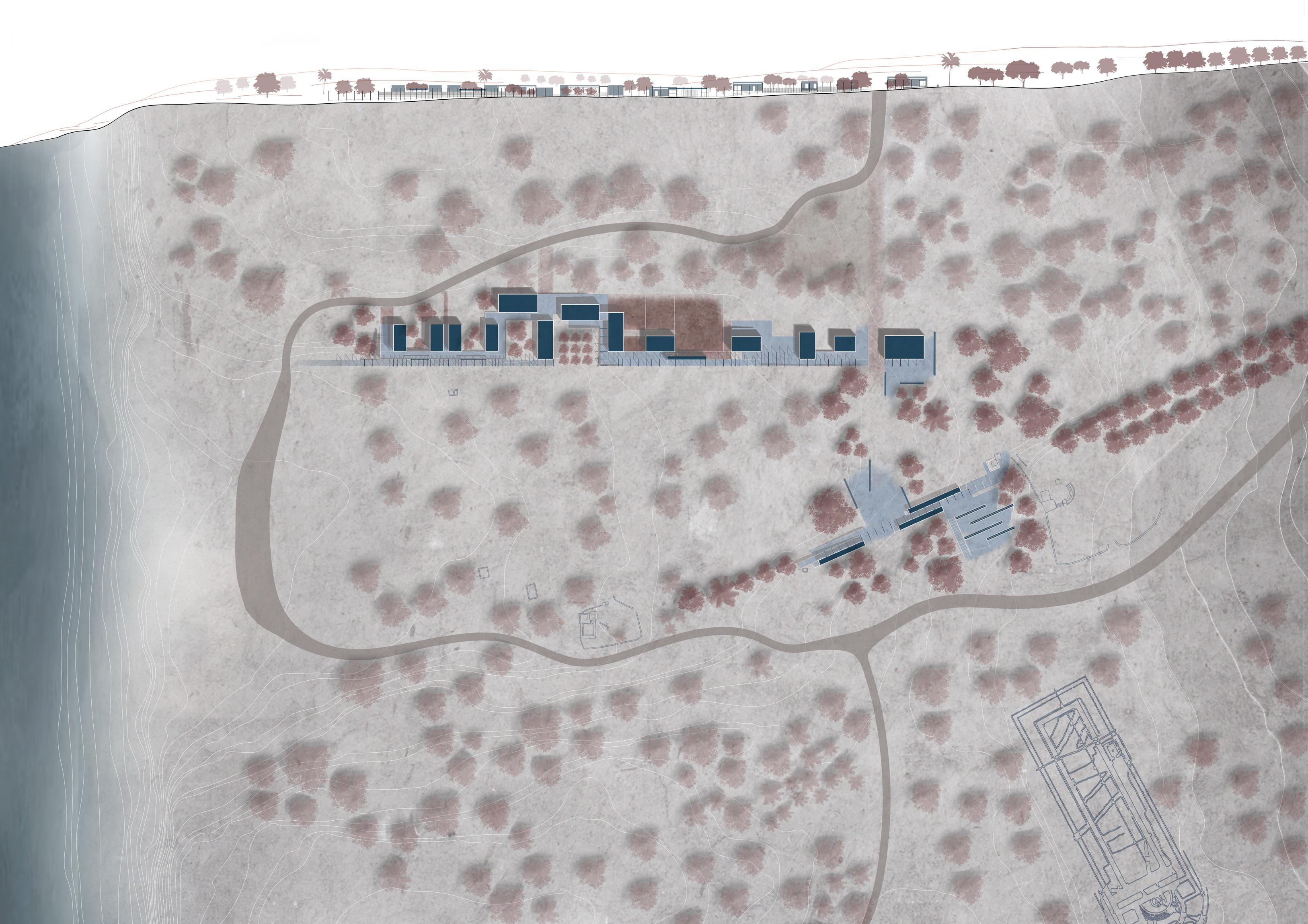

A Planivolumetrico e sezione ambientale di progetto. | Planivolumetric and environmental section of the project.

A’ 0 10 20 40 60 m 100

pagina precedente / previous page Vista delle teche espositive. | View of the expositive cases.

Forme del presente per allontanare l’oblio Shapes of present to ward off oblivion

Ricerca e musealizzazione

Il patrimonio culturale è narrazione della propria storia, è ricchezza del luogo e della relativa popolazione nel quale ritrova il senso di comunità e di appartenenza. In esso si identifica grazie alla forza del bello e alla potenza della memoria.

La città, come l’architettura, storica deve però rinnovarsi per non cadere nell’oblio e dimenticare se stessa. Il paradosso della conservazione esiste proprio in questi termini :

“…nulla si conserva mai né mai si tramanda se resta immobile e stagnante. Anche la tradizione è un continuo rinnovarsi…” (Settis)

La necessità di tale movimento e innovazione deve però preservare tale dna ricco di valori e di storia, confrontandosi in parallelo con il presente.

L’intervento in un sito archeologico deve tenere ben stretti questi temi , ed il progetto dell’ ‘agire sensibile’ dell’architetto diventa, instaurandosi, un dialogo tra presente e passato.

L’area archeologica di Ashkelon entra a far parte dei parchi nazionali israeliani, diventando meta turistica per le attività di balneazione, campeggio e altri eventi oltre alle visite d’interesse prettamente culturale legate alle rovine del sito. Alcune aree del parco sono at-

tualmente ancora da rilevare, molti dei resti archeologici sparsi nell’area ancora da portare alla luce. Gli scavi archeologici sono stati quindi ripresi e convivono con gli ingressi dei visitatori che ogni anno affollano il parco. Ancora oggi il sito è però carente di infrastrutture attrezzate sia per i turisti che per i ricercatori e archeologi che lavorano nell’area; oltre a non avere un’accurata organizzazione e gestione del luogo nel quale è possibile ritrovare parti di capitelli, colonne, trabeazioni e resti vari ammassati a terra senza alcuna attenzione né salvaguardia. Dall’analisi delle condizioni attuali e solo dopo un’approfondita ricerca storica, il progetto ha preso forma assumendo funzionalità eterogenee che potessero far dialogare le diverse necessità del sito e confrontarsi con un pubblico variegato. Si assume in questo modo il compito di valorizzare l’antica città di Ashkelon generando nuove forme che possano dialogare con la contemporaneità ma ritenendo prioritario il compito di esaltare il suo patrimonio culturale.

Research and musealisation

Cultural heritage is the narration of one’s own history, it is the wealth of the place and its people in which they find their sense of community and belonging. It identifies itself through the power of beauty and the power of memory.

However, the historical city, like architecture, must renew itself in order not to fall into oblivion and forget itself. The paradox of preservation exists precisely in these terms :

“…nulla si conserva mai né mai si tramanda se resta immobile e stagnante. Anche la tradizione è un continuo rinnovarsi…” (Settis)

The need for such mobility and innovation must not, however, preserve this dna rich in values and history through a simultaneous confrontation with the present.

An intervention in an archaeological site must respect these concepts, and the architect’s ‘sensitive approach’ project becomes a dialogue between the present and the past.

The archaeological area of Ashkelon became part of Israel’s national parks, turning into a tourist destination for bathing, camping and other activities in addition to cultural visits related to the site’s ruins. Some areas of the

park are currently still to be surveyed, many of the archaeological remains scattered in the area are still to be unearthed. Archaeological excavations have therefore been resumed and coexist with the visits by people who annually flock to the park. Even today, there is still a lack of wellequipped infrastructure both for tourists and for researchers and archaeologists working in the area, as well as a need for careful organisation and management of the site, where parts of capitals, columns, entablatures and various remains can be found piled up on the ground without any care or protection.

From the analysis of the current conditions and only after in-depth historical research, the project was shaped by adopting heterogeneous functionalities that could dialogue with the different needs of the site and deal with a diversified target audience. In this way, the task of enhancing the appeal of the ancient city of Ashkelon is taken on by generating new form that can dialogue with the contemporary world while prioritising the task of enhancing its cultural heritage.

33

Sezione CC’ delle teche espositive verso la Basilica. | Section CC’ of the exhibition cases towards the Basilica.

Sezione CC’ delle teche espositive verso la Basilica. | Section CC’ of the exhibition cases towards the Basilica.

35 A B C

Da queste considerazioni, necessità ed intenti, si è così sviluppata l’idea di progettare un museo non convenzionale, dove lo scavo e l’attività archeologica diventano l’oggetto di esposizione; oltre ad un think tank come complesso eterogeneo per venire incontro alle esigenze relative sia alla ricerca che a quelle prettamente turistico-ricettive. Un museo a cielo aperto che si arricchisce di attività integrando i turisti e i cittadini più frequenti, dove la vitalità delle interazioni genera una forte simbiosi tra cultura e svago.

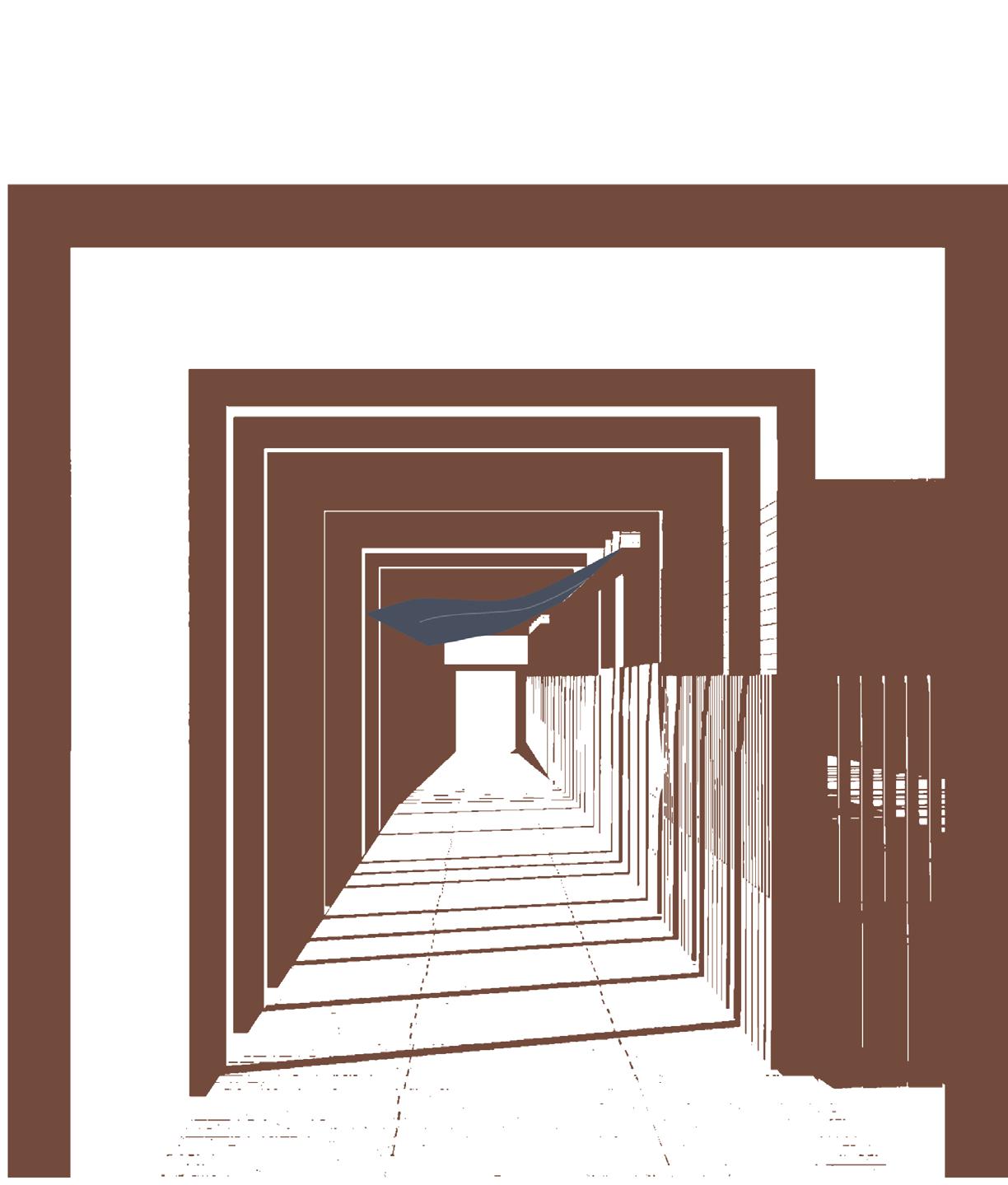

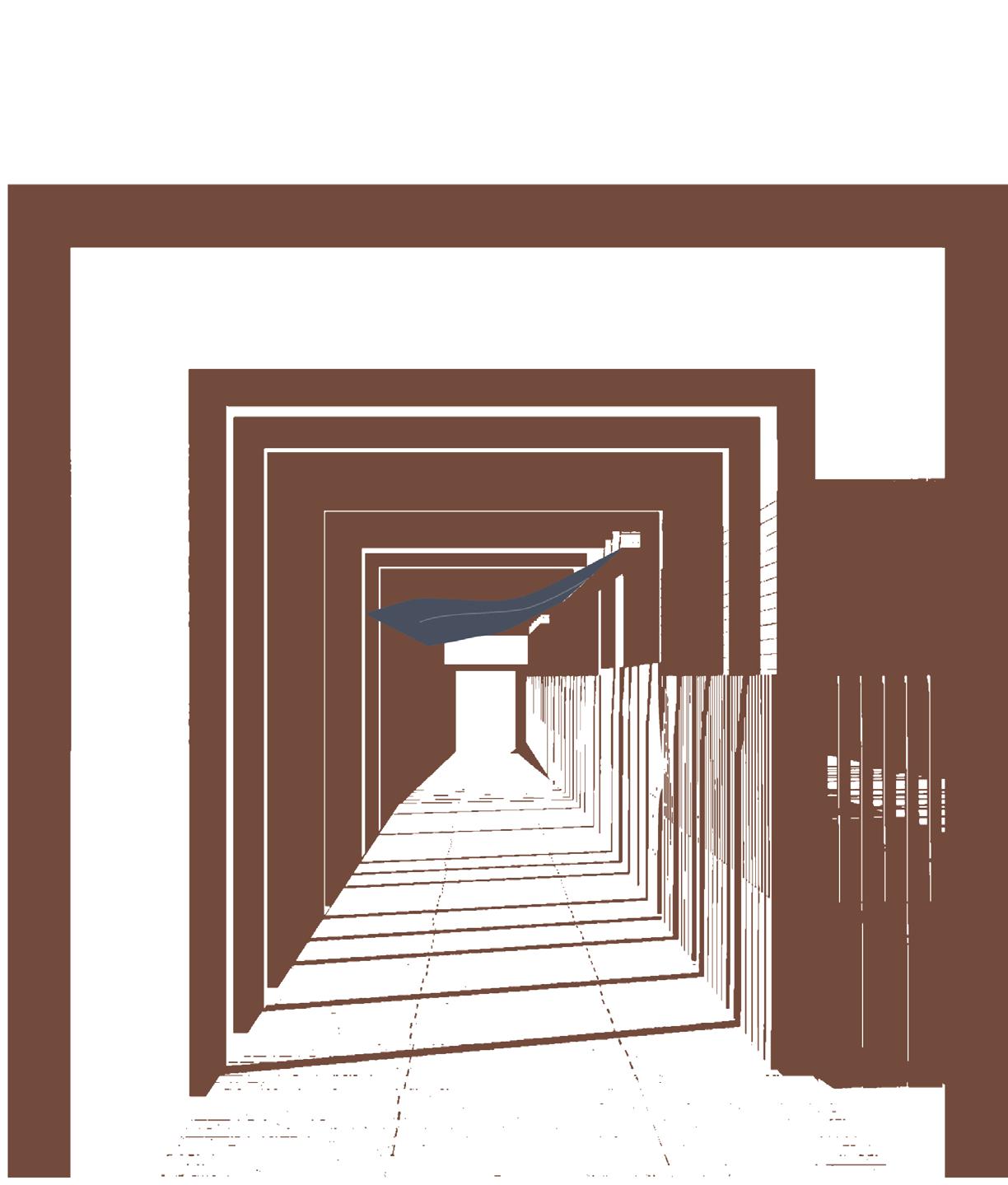

Think tank e musealizzazione non sono però entità separate e distanti, sono strutture simbionti che dialogano e si confrontano attraverso un percorso. Percorso che diventa un forte elemento connettivo e di progetto: lo stoà

Il dialogo con la storia continua nell’architettura attraverso la ripresa del topos greco della via porticata, rappresentata nella raffigurazione di Ashkelon sulla mappa di Madaba da bianche ed esili colonne che seguono la direzione del Cardo e del Decumano.

Lo stoà sviluppandosi lungo due direzioni, le stesse direzioni degli assi del Decumano ritrovati in Madaba, vuole essere un forte richiamo alla storia della città con l’intento di creare quel velato ricordo dell’antica sua conformazione.

I singoli elementi di progetto, diffusi nell’area, sono affiancati e allineati da tale percorso porticato assumendo forti proprietà connettive. Quest’azione ha permesso all’area archeologica dell’entroterra di interagire con quella balneare del fronte mare non solo visivamente, ma creando una congiunzione molto più forte e diretta.

These considerations, needs and intentions led to the idea of designing an unconventional museum, where the excavation and archaeological activities become the subject of the exhibition, besides a think tank as a heterogeneous complex to satisfy both research and tourist-recreation needs.

An open-air museum that is enriched with activities integrating tourists and frequent visitors, where the vitality of interactions generates a strong symbiosis between culture and recreation. However, think tank and musealisation are not disconnected and unrelated entities. They are simbiotic structures interacting with and facing each other through the pathway. A path that becomes a strong connective element of the project: the stoà

The dialogue with history continues throughout the architecture by taking up the Greek topos of the porticoed street. In the depiction of Ashkelon on the Madaba map , it is represented by slender white columns following the direction of the Cardo and the Decumanus.

The stoà is meant to be a strong reminder of the city’s history, developing along two directions. The same directions as the axes of the Decumanus found in Madaba. Its aim is to create that veiled memory of its ancient conformation.

Il percorso diventa museo: un museo in divenire.

The individual elements of the project, spread throughout the area, are flanked and aligned by this porticoed pathway, assuming strong connective properties. This action allowed the archaeological area of the hinterland to interact with the seaside area of the waterfront, not only visually but creating a a stronger and more direct connection.

The path becomes a museum: a museum-to-be.

The path becomes a museum: a museum-to-be.

AREA TURISTICO-RICETTIVA

Sala espositiva Info point Shop

AREA BOTANICA

THINK TANK Ristoro Sagra/Picnic Orti Laboratorio botanica

Laboratori archeologici Laboratori aperti al pubblico Hortus conclusus Ricerca

Alloggi ricercatori/ archeologi

pagina precedente / previous page Illustrazione dello stoà con le vele. | Illustration of the stoa with sails.

Vista aerea di progetto con relative funzioni. | Project aerial view with related functions.

37 TECHE ESPOSITIVE

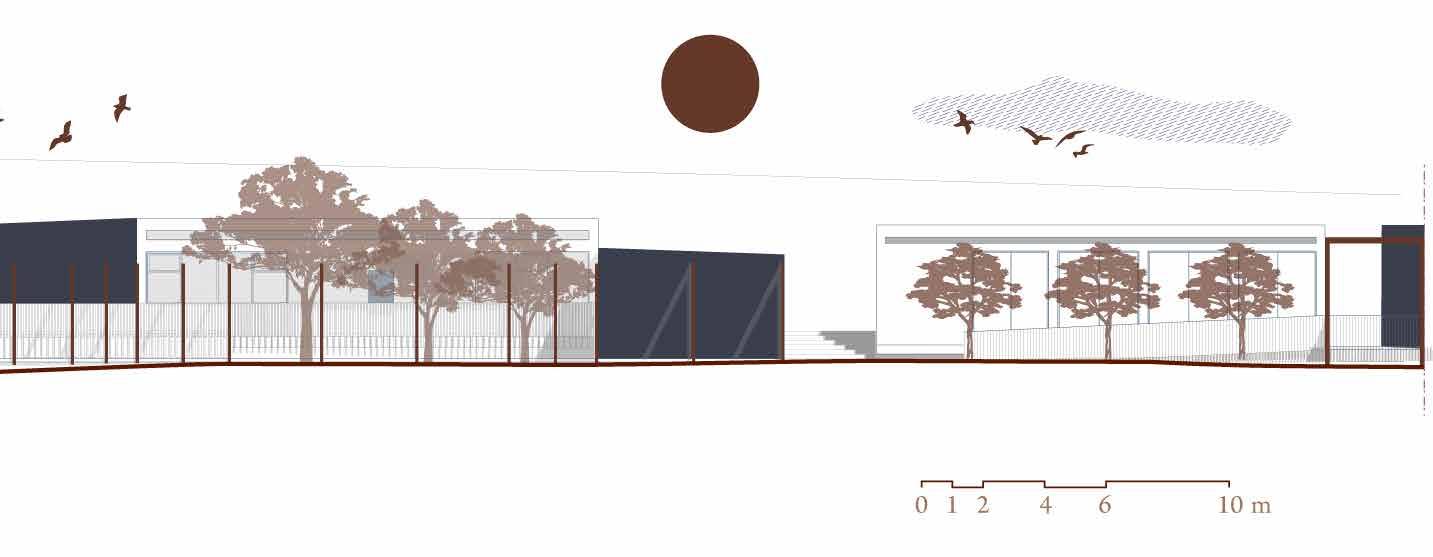

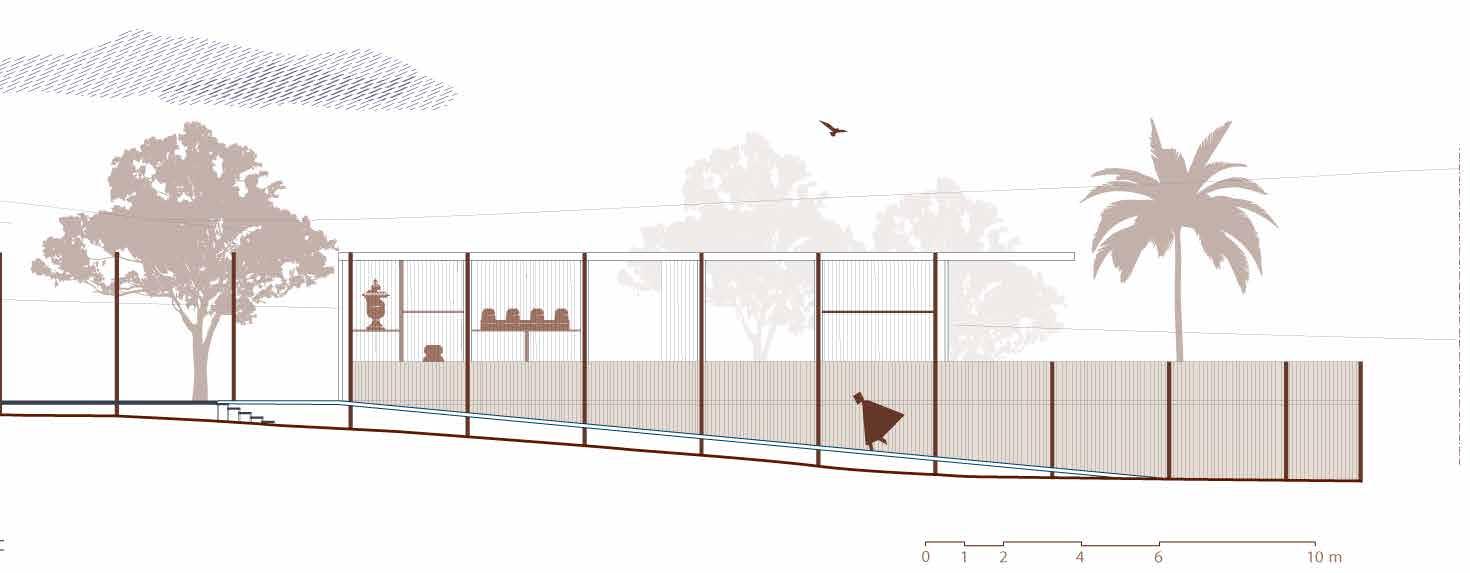

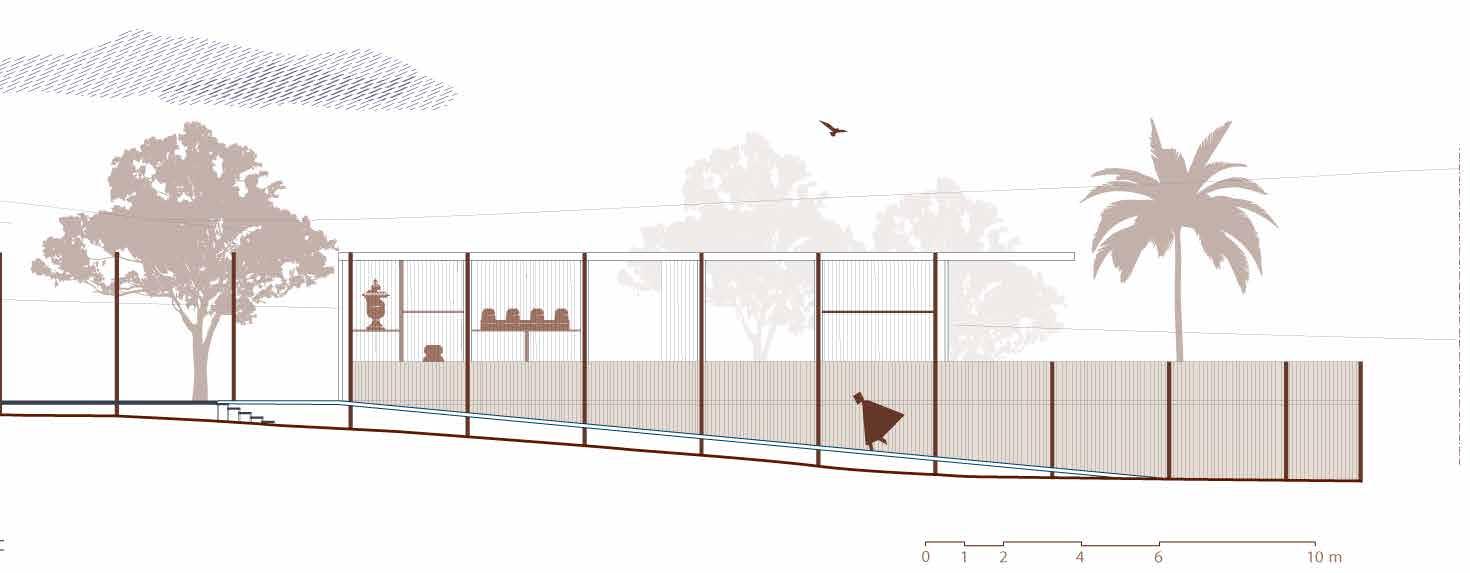

Prospetto Nord delle teche espositive verso la Basilica. | North Elevation of the exhibition cases towards the Basilica.

Prospetto Nord delle teche espositive verso la Basilica. | North Elevation of the exhibition cases towards the Basilica.

Un museo in divenire

Entrare nel National Park di Ashkelon è come accedere a un museo archeologico a cielo aperto, dove è possibile scoprire i resti dell’antica città disseminati nel suo suolo terroso. Sin dall’incontro visivo con le prime rovine, le possenti mura canaanite, nella nostra mente la ruina genera una ricostruzione molto approssimativa, immaginaria in certi casi, di quella antica egemone città portuale.

L’intervento, delicato nella sua semplicità ed impatto, non vuole racchiudere nella classica scatola museale la storia di Ashkelon, ma bensì sfruttare le caratteristiche del sito rendendo esso stesso museo.

L’asse verso la Basilica è il ponte di dialogo più diretto con la memoria di Ashkelon, ed è proprio attraverso l’esposizione delle sue rovine in aperte teche lungo questa direttrice che si riapre la narrazione. Esili teche espositive che vi si inseriscono in silenzio, ridando voce e dignità a quelle rovine che attualmente sono disperse nel sito. Permettendone una miglior cura e conservazione. Non sono state pensate solo come mobilio museale ma diventano elementi funzionali anche per gli scavi, durante i quali possono essere utilizzate dagli archeologici come deposito temporaneo in attesa di una successiva catalogazione e restauro.

La Basilica diventa dunque la quinta delle rovine in esposizione che, anticipando questa, ne forniscono un’immagine anche se frammentata.

Attraverso la disposizione delle teche, il progetto delinea un vero e proprio percorso che viene interrotto ad un certo punto dall’intersezione con il Cardo. In questo preciso incrocio, attraverso un sistema di rampe e di scale, si apre il collegamento diretto con la Basilica stessa con la quale condivide l’orientamento.

Rimanendo a est della via Maris ma spostandoci nell’altro asse del Decumano, è stato progettato un ambiente chiuso che potesse fungere da sala esplicativa con materiale informativo e di divulgazione di vario genere, dalla realtà virtuale agli ologrammi. Dove poter narrare la storia dell’antica Ashkelon, non solo attraverso le sue rovine.

Il percorso museale prosegue verso il fronte mare, le teche espositive si dispongono lungo lo stoà diventando il legante tra le aree più culturali e quelle costiere, puramente di svago.

Non esiste un vero e proprio ingresso, non ci sono né inizio né fine predisposti: il percorso museale non ha limites.

J. Garstang e W. J. Phythian-Adams esaminano la statua della Nike.| J. Garstang and W. J. Phythian-Adams examining the statue of Nike. (Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund)

Illustrazione delle teche espositive e stoà. | Illustration of the expositive cases and stoà.

A museum-to-be

Walking into Ashkelon National Park is like visiting an open-air archaeological museum, where it is possible to find the remains of the ancient city scattered across its earthy soil. From the very first visual contact with the early ruins, the mighty Canaanite walls, in our minds the ruin generates a very rough reconstruction, an imaginary one in some cases, of that ancient hegemonic port city.

The intervention, gentle in its simplicity and impact, is not intended to enclose the history of Ashkelon in the classic museum box. Instead, it exploits the characteristics of the site by making it a museum itself.

The axis towards the Basilica is the most direct bridge of dialogue with the memory of Ashkelon, and it is through the display of its ruins in open showcases along this axis that the narrative is reopened. Thin display cases are silently placed there, restoring voice and dignity to those ruins that are currently scattered around the site, allowing them to be better maintained and preserved. They have not only been conceived as museum furniture but also become functional elements for excavations, during which they can be used by archaeologists as a temporary repository pending later cataloguing or restoration.

The Basilica consequently becomes the backdrop for the exhibited ruins which, anticipating this, provide an image of it, however fragmented.

Through the arrangement of the showcases, the project outlines an actual itinerary that is interrupted at a certain point by the intersection with the Cardo. At this precise intersection, through a system of ramps and stairs, a direct connection opens up with the Basilica itself, sharing the orientation with the latter.

Keeping to the east of the Via Maris but shifting to the other axis of the Decumanus, an enclosed room was designed to work as an explanatory room with various kinds of information and dissemination material, from virtual reality to holograms. A room where the history of ancient Ashkelon could be told, not only through its ruins. The museum itinerary continues towards the waterfront, the display cases are arranged along the stoà and become the link between the more cultural areas and the coastal, purely recreational ones.

There is no real entrance, there are no designated starts or end points: the museum itinerary has no limits.

41

Modello 3D con texture della Nike alata nel Ashkelon National Park. | 3D textured model of the winged Nike in the Ashkelon National Park. (digital photogrammetry, Ashkgate mission 2020)

Sezione AA’

Sezioni AA’ e BB’ delle teche espositive verso la Basilica. | Sections AA’ and BB’ of the exhibition cases towards the Basilica.

Sezione AA’

Sezioni AA’ e BB’ delle teche espositive verso la Basilica. | Sections AA’ and BB’ of the exhibition cases towards the Basilica.

Sezione BB’ A B C

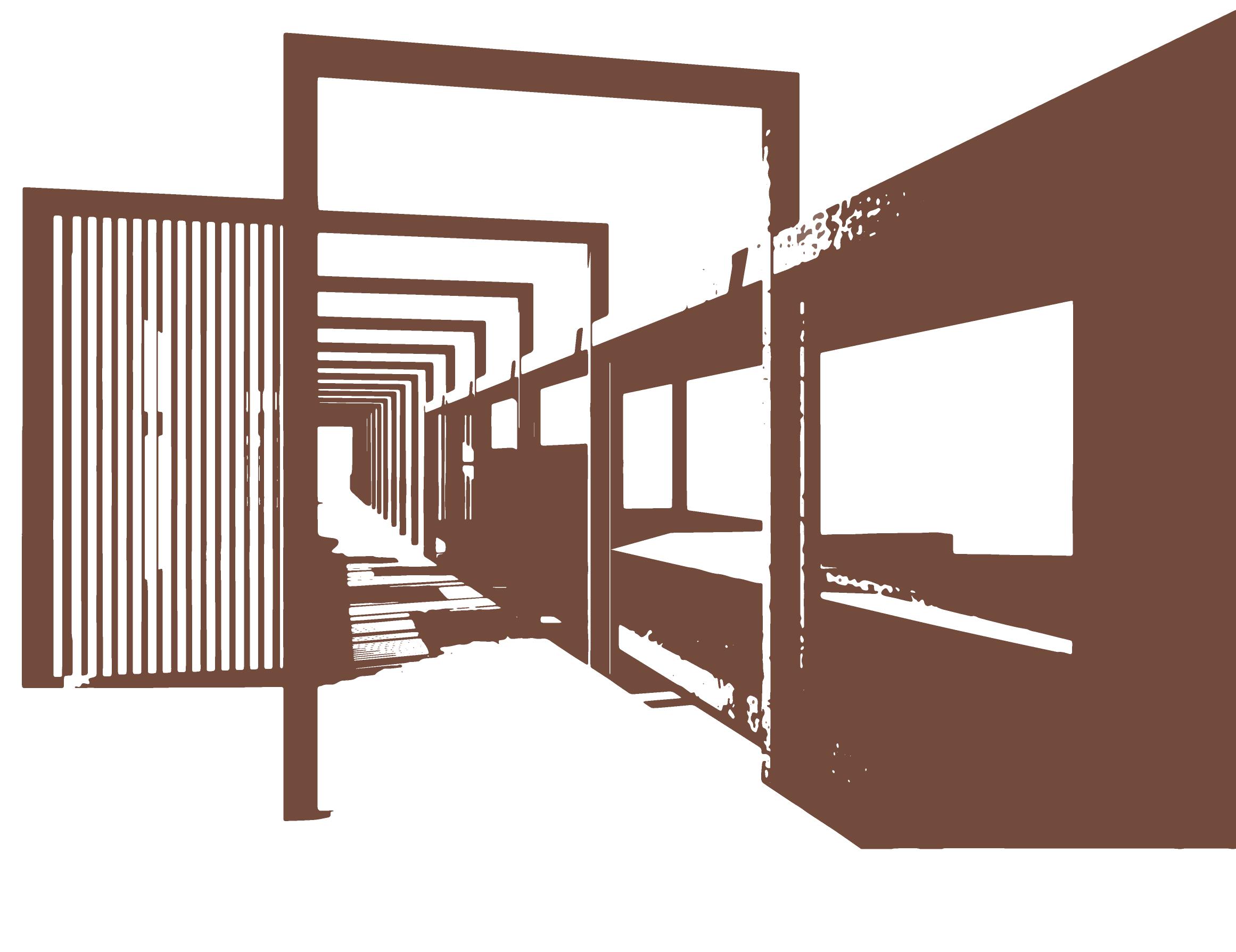

Il think tank

Il National Park di Ashkelon gode di una caratteristica peculiare, ancora oggi gli scavi archeologici sono operanti ed al contempo è presente un’affollata attività balneare. Il sito gode quindi di una duplice funzionalità, una più ludica e un’altra più culturale e di ricerca. Il progetto vuole perciò creare un organismo architettonico eterogeneo, nel quale archeologi, studiosi e turisti possano condividere e fare esperienza dell’antica città di Ashkelon.

Dall’idea dunque di generare un luogo vivo ed attivo, complesso nelle sue diverse attività ma allo stesso tempo unitario, nasce il think thank: piccoli elementi eterogenei capaci di ascoltare e soddisfare le distinte esigenze degli utenti.

Riuscendo in questo modo a condividere e accrescere nella diversità, negando il sonno eterno di un luogo che ha ancora molto da raccontare.

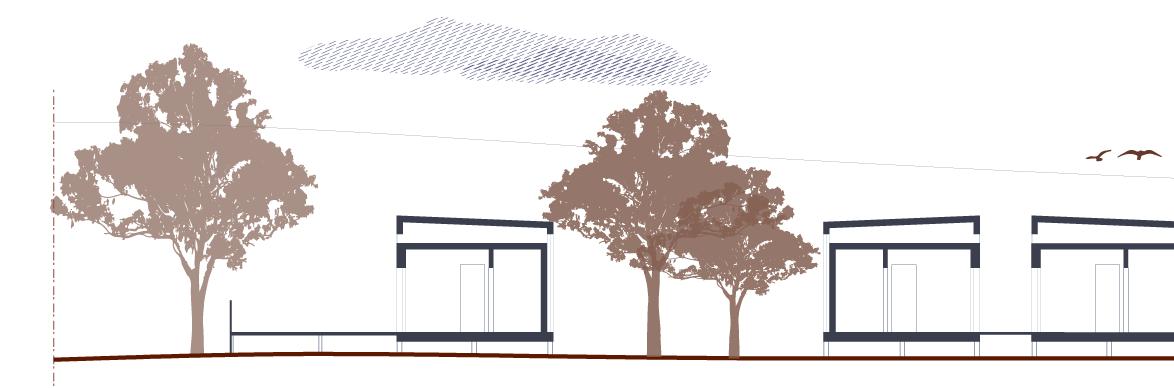

Nell’asse più lungo che arriva al fronte mare senza interruzioni si dispongono armonicamente i singoli fabbricati affacciandosi sulla via pergolata che tiene il fronte interno ben definito, mentre assumono una maggior libertà compositiva nel lato del fronte strada. La loro disposizione funzionale permette l’accoglienza del turista nell’area archeologica offrendo varie infrastrutture come un infopoint, alcuni

shops e un ristorante per poi assumere caratteristiche più vicine alla sfera archeologica e di ricerca progredendo verso il mare, come i laboratori, le sale comuni polifunzionali e gli alloggi. Il desiderio di riportare l’importanza dell’agricoltura in quelle terre ancora fertili, ha portato a progettare un’area dove la vegetazione è protagonista. Viene così progettata una zona caratterizzata dalla presenza di un laboratorio di botanica e da vari orti sui quali si affaccia il ristorante, garantendo così una cucina a km 0 con la materia prima del sito. Quest’area si presterebbe perciò molto bene a sagre all’aperto e picnic, già estremamente diffusi nel sito ma senza attualmente opportune attrezzature.

CAMERA

Illustrazione dello stoà nei pressi dei laboratori ed hortus conclusus. | Illustration of the stoà near the laboratories and the hortus conclusus.

CAMERA

Illustrazione dello stoà nei pressi dei laboratori ed hortus conclusus. | Illustration of the stoà near the laboratories and the hortus conclusus.

The think tank

The Ashkelon National Park has a unique feature; archaeological excavations are ongoing and at the same time the beach is crowded with bathers. The site therefore enjoys a dual functionality, one more recreational and another more cultural and research-related.

The project is thus intended to create a heterogeneous architectural organism in which archaeologists, academics and tourists can share and experience the ancient city of Ashkelon. So from the idea of generating a living and active place the think thank was born, complex in its various activities but at the same time unitary. Small heterogeneous elements capable of listening to and satisfying the distinct needs of the users.

Thus managing to share and grow in diversity, denying the eternal sleep of a place that still has much to tell.

In the longest axis that reaches the waterfront without interruption, the individual buildings are harmoniously arranged facing the via pergolata that keeps the internal front well-defined, while they take on greater compositional freedom on the side of the street front. Their functional layout allows the tourist to be welcomed into the archaeological area by offering infrastructural items such as an info-

point, some shops and a restaurant. They then assume more archaeological and research-related functions as they progress towards the sea, such as laboratories, multifunctional common rooms and accomodations.

The desire to bring the importance of agriculture back to these still fertile lands led to the design of an area where vegetation is the protagonist. Thus an area characterised by the presence of a botany laboratory and several botanical gardens overlooked by the restaurant was designed. This guarantees a zero-kilometre cuisine using the site’s raw materials. The area would therefore easily lend itself to open-air festivals and picnics, which are already extremely popular on the site but currently lack the appropriate facilities.

45

brise-soleir vetro

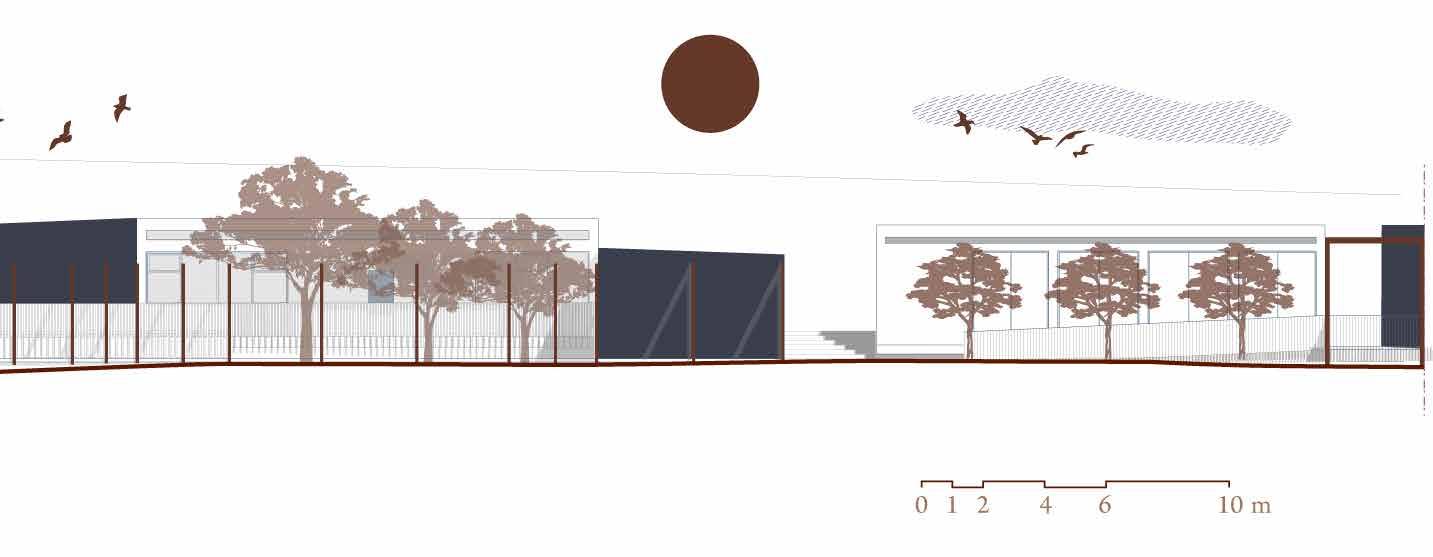

sopra / upper side Sezione BB’ del think tank. | Think tank section BB’.

Illustrazioni delle scelte tecnologiche di comfort per i moduli del think tank. | Illustrations of comfort technology choices for think tank modules.

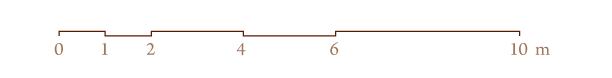

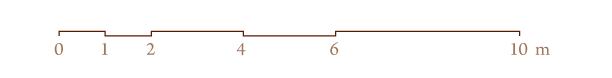

0 1 2 4 6 10 m ±0.00 -1.50 -1.00 B

Pianta del think tank. | Plan of the think tank.

47 ±0.00 -1.00 -1.50 -1.50 A’ B’ A

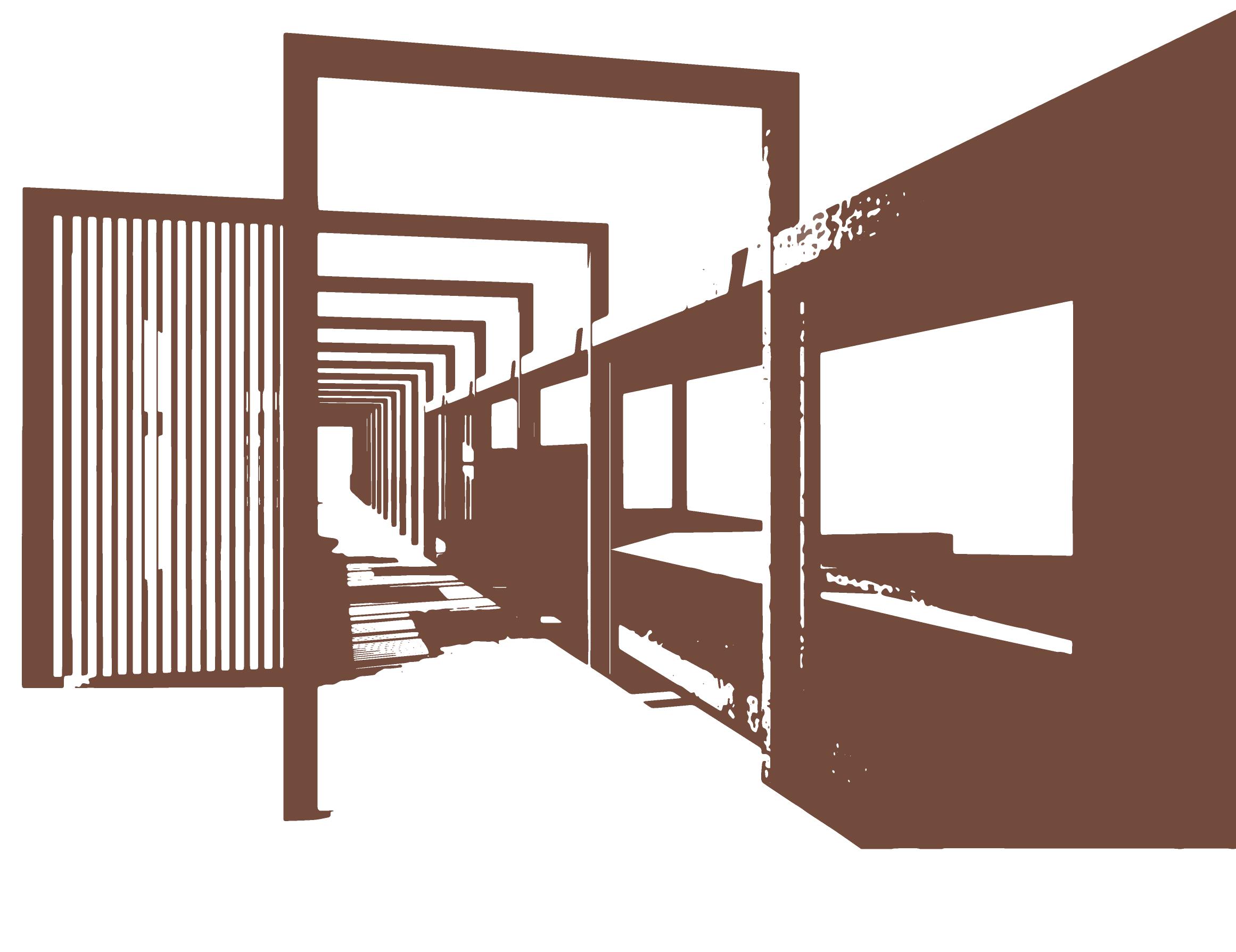

Di seguito, proseguendo verso il mare, attorno ad un hortus conclusus di ulivi, sono disposti due laboratori di cui uno, avendo un lato quasi completamente vetrato, si mostra al visitatore il quale può osservare gli archeologi al lavoro durante la passeggiata lungo lo stoà. Alcuni di questi spazi laboratoriali sono accessibili anche ai turisti grazie all’organizzazione di attività esperienziali, di laboratorio, dando l’opportunità di avere un contatto diretto e personale con il luogo e la sua storia.

Arrivando infine all’estremità dell’asse a nord, il progetto sfrutta un salto del terreno con un dislivello di quasi tre metri sdoppiando in altezza il percorso, il quale alla quota inferiore si materializza diventando l’ultimo tratto pergolato che accompagna il cammino verso la spiaggia. L’ultimo tratto pergolato che incornicia il mare.

L’estremità superiore della biforcazione dell’asse è invece adibita all’alloggio per i ricercatori, gli archeologi o per gli studenti universitari che vogliono svolgere attività di studio e di ricerca nel sito. I moduli abitativi si dispongono a

due a due definendo un’area verde di intramezzo che li separa. Arrivando da est e percorrendo il percorso pergolato, le abitazioni sono precedute da un corpo di fabbrica più grande con vari spazi comuni.

Il dislivello naturale del terreno permette una vicinanza visiva e integrità volumetrica, ma allo stesso tempo mantiene la privacy delle abitazioni separando i flussi dei turisti con quelli di chi lavora e studia sul sito.

Questa sistemazione complessiva vuole far interagire le attività d’interesse culturale con quelle prettamente ludiche e di svago, con l’intento di suscitare interesse al visitatore occasionale e farlo avvicinare alla storia dell’antica Ashkelon. Il progetto vuole in questo modo facilitare il lavoro all’interno del sito, dando delle infrastrutture per poter vivere lo scavo e l’area archeologica .

Eterogeneità funzionale dei singoli fabbricati si amalgamano in una unicità visiva del tessuto volumetrico.

Continuing towards the sea, around a hortus conclusus of olive trees, two workshops have been arranged, one of which, having an almost completely glassed-in side, is visible to visitors who can observe the archaeologists at work during their walk along the stoà Some of these laboratory spaces are also accessible to tourists thanks to the planning of experiential activities, giving them the opportunity to have a direct and personal contact with the place and its history.

Finally reaching the end of the northern axis, the project exploits a drop in the terrain with a difference in height of almost three metres, doubling the height of the path, which at the lower elevation becomes the last pergola stretch that accompanies the path towards the beach. The last pergola part framing the sea.

The upper end of the axis doubling is instead used for accommodation for researchers, archaeologists or university students carrying out study and research activities on-site. The living modules have been arranged two

by two defining a green area between them and are preceded by a larger building with various common areas. The natural difference in height of the terrain allows for visual closeness and volumetric integrity, but at the same time maintains the privacy of the residences by separating the fluxes of tourists from those who work and study on the site.

This overall arrangement is intended to make activities of cultural interest interact with activities of a recreational and entertainment kind. The intention is to arouse the interest of the casual visitor and bring him/her closer to the history of ancient Ashkelon. In this way, the project aims to facilitate work on the site by providing facilities for experiencing the excavation and the archaeological area.

The functional heterogeneity of the individual buildings blends into a visual uniqueness of the volumetric framework.

0 1 2 4 6 10 m

Sezione AA’

pagina precedente / previous page

Sezione AA’ del think tank | Section AA’ of the project

Illustrazione dei laboratori e dell’hortus conclusus | Illustration of the laboratories and the hortus conclusus

LAB

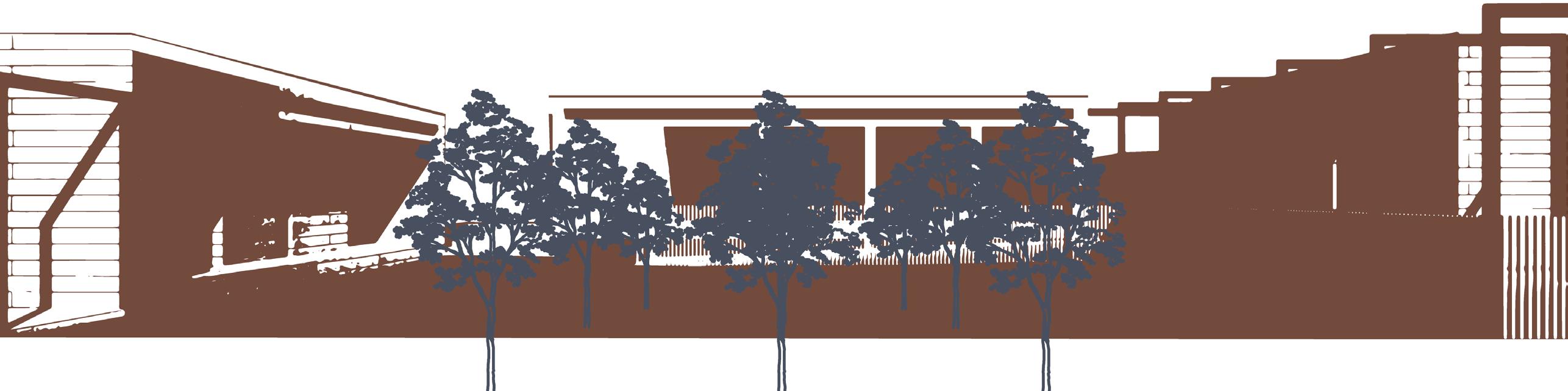

Prospetto Sud del

| South

think tank.

Elevation of the think tank.

Temporaneità e sostenibilità

Intervenire in un’area archeologica richiede un’estrema sensibilità e accuratezza, responsabilità ed ascolto. Un’architettura responsabile ha intrinseco un forte valore etico, di rispetto e di devozione alla società, in cui l’ego dell’architetto viene un po’ meno. Un gesto minuzioso che risponde attentamente alle richieste e necessità.

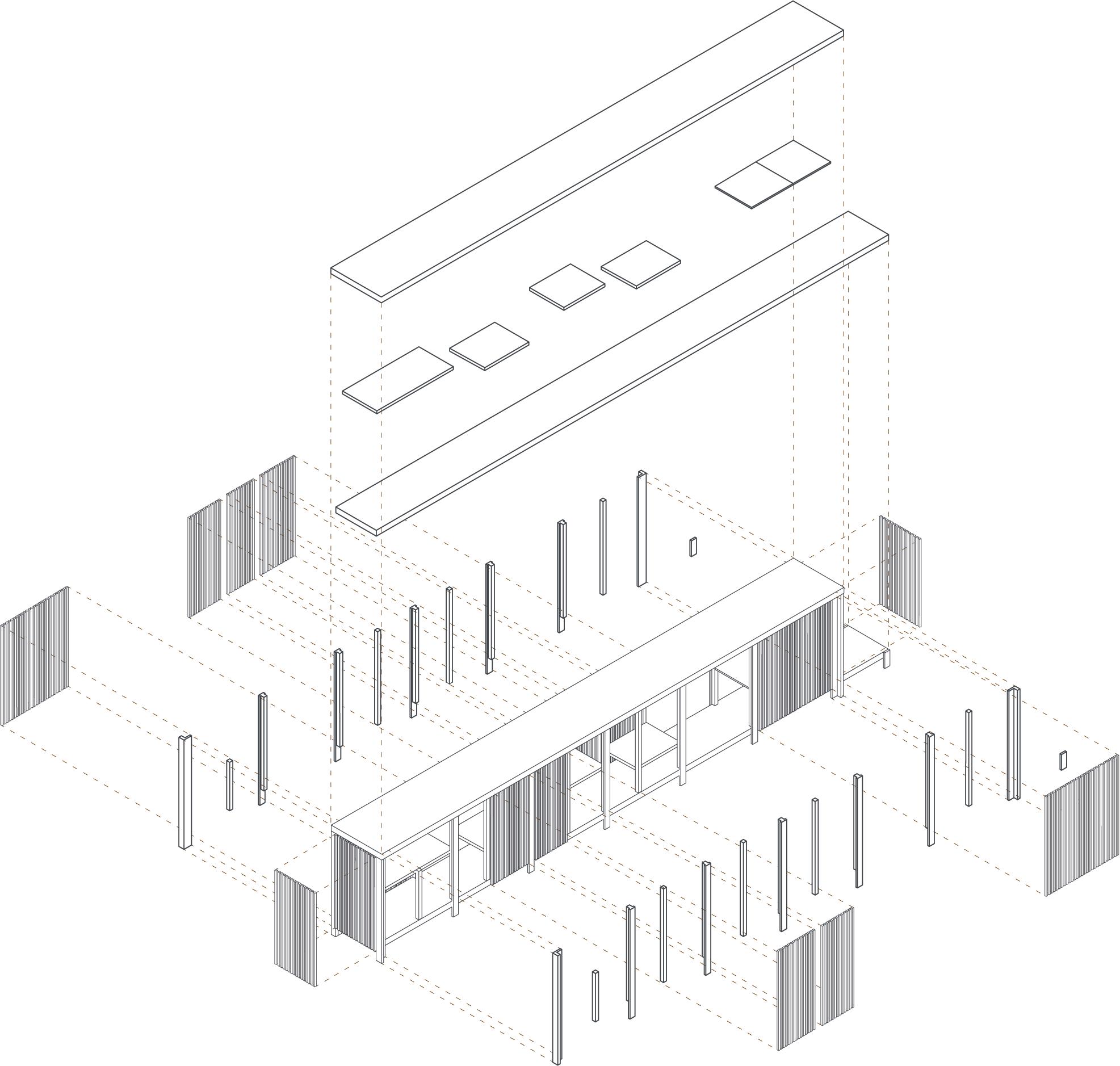

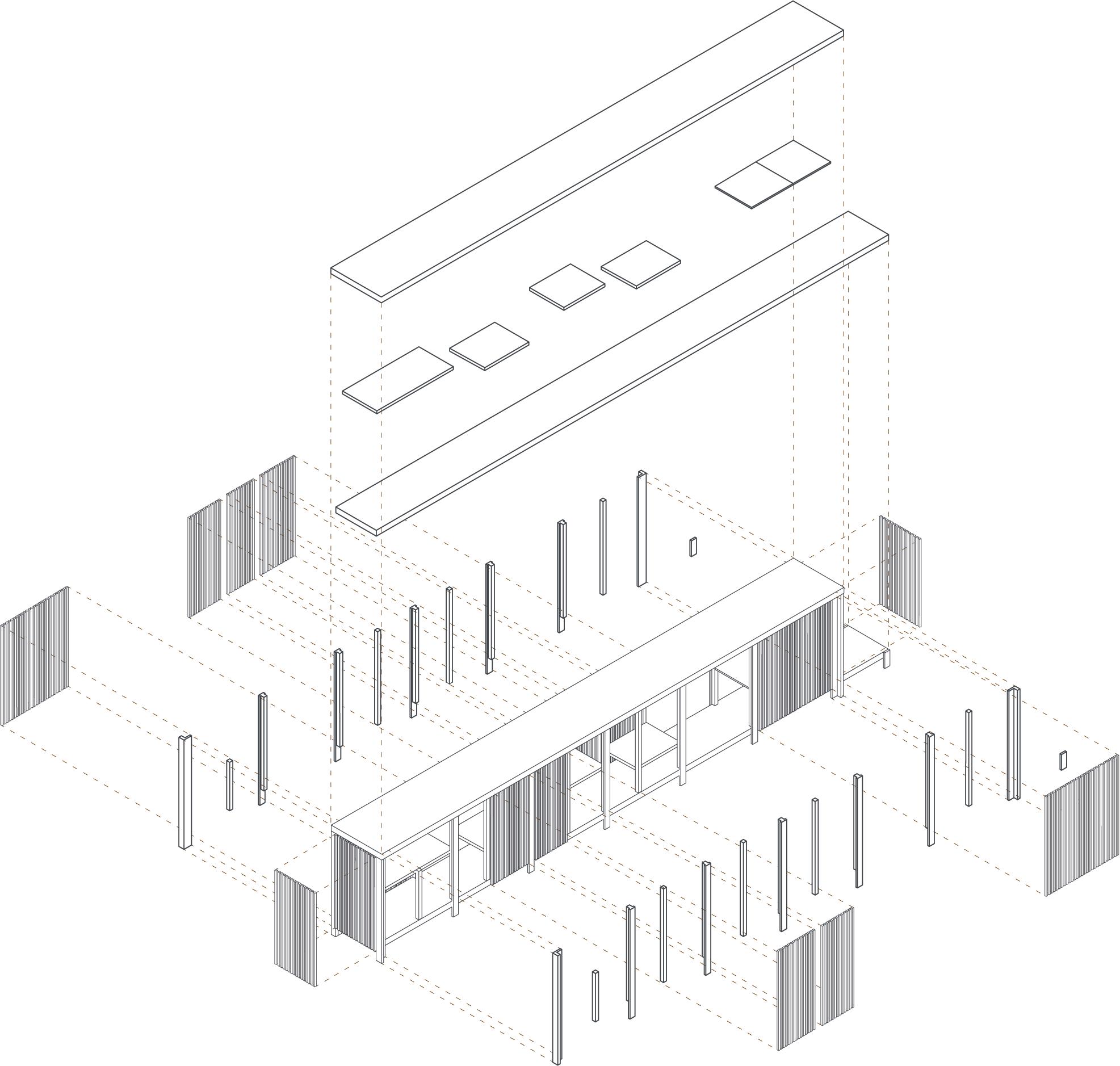

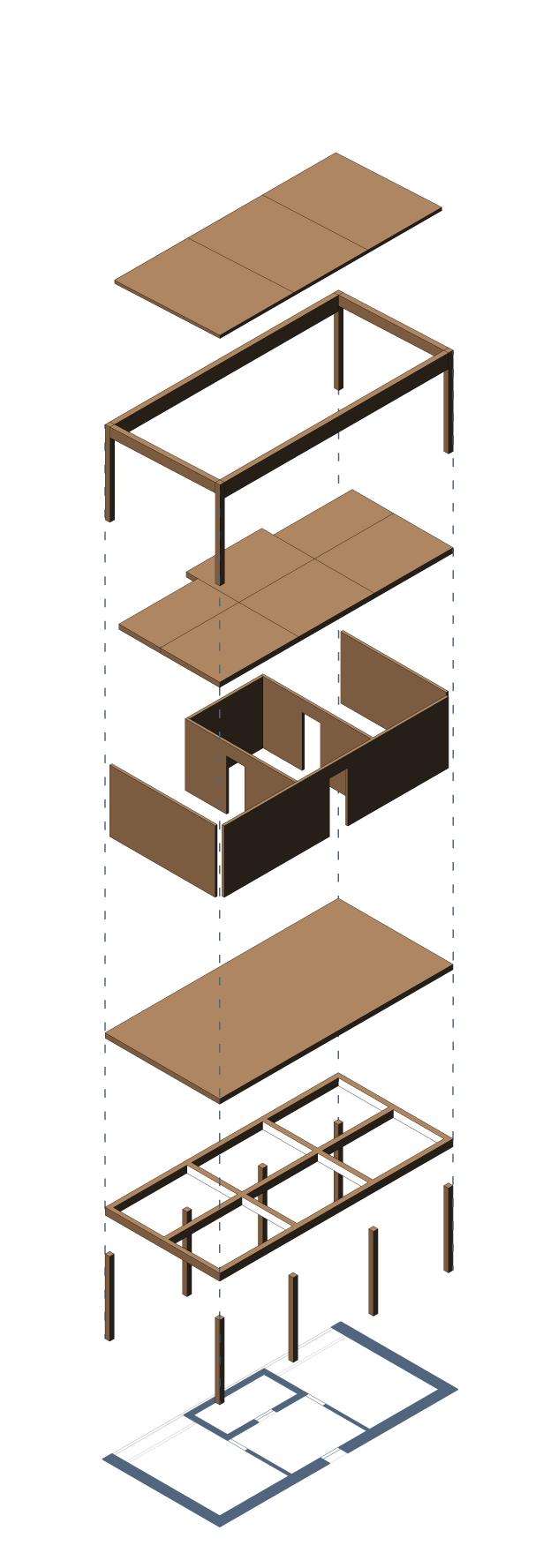

Il sito di progetto quindi ha fortemente influenzato la scelta tecnologica, facendola vertere verso strutture non invasive e mobili. Reversibilità e temporaneità sono i principi cardini progettuali che hanno portato alla determinazione di un’architettura effimera , modulare, in legno e acciaio elevata su fondazioni puntiformi a vite per un impatto minimo con il terreno.

Il modulo abitativo è stato studiato nel dettaglio sia in pianta, che a livello tecnologico-costruttivo, definendo in questo modo un modello base potenzialmente ripetibile e riutilizzabile in contesti diversi. La struttura del corpo di fabbrica è un ibrido: un’ossatura portante di travi e montanti in legno lamellare tamponata da setti in xlam

che vengono usati anche come orizzontamenti nel solaio e in copertura.

Il modulo poggia su un telaio ligneo o d’acciaio che fa da base, al quale si collegano le fondazioni a vite rimanendo in questo modo sopraelevato come le architetture su palafitte.

La struttura scatolare delle case modulari prefabbricate viene scomposta diventando una ‘scatola-nella-scatola’ con la creazione, per questioni di comfort, di un’intercapedine tra il tetto ed il solaio diventando un passaggio ventilato. Il lato lungo che si affaccia verso l’area verde alberata, è caratterizzato da due grandi aperture vetrate oscurate da brisesoleil in legno con controllo domotico, mentre quello opposto corrisponde all’ingresso dell’abitazione. Al suo interno gli spazi delle due camere da letto ed il bagno si sviluppano attorno allo spazio comune di ingresso.

Ciò che lo distingue dall’architettura modulare prefabbricata è l’accurata progettazione e attenzione ai dettagli che lo svincolano dalla rigida forma minimalista del parallelepipedo.

Temporariness and sustainability

Intervenin in an archaeological area requires extreme sensitivity and accuracy, responsibility and listening. Responsible architecture entails strong ethical values, respect and dedication to society, and leaves less room for the architect’s ego. A meticulous gesture that carefully complies with requests and needs.

The project site has therefore strongly influenced the choice of technology, making it focus on non-invasive and mobile structures. Reversibility and temporariness are the pivotal design principles that have led to the determination of an ephemeral and modular architecture in wood and steel, elevated on screw-type point foundations for minimal impact with the soil.

The housing module has been studied in detail both in plan and on a technological-constructive level, thus defining a basic model that is potentially repeatable and reusable in different contexts. The structure of the building is a hybrid: a load-bearing framework of lamellar wood beams and columns buffered by xlam partitions that

are also used as ceiling and roof structures. The module stands on a wooden or steel frame that constitutes the base, to which the screw foundations are connected. In this way it remains elevated like stilt architecture. The box structure of the prefabricated modular houses is broken up to become a ‘box-within-a-box’ with the creation, for the purpose of comfort, of a cavity between the roof and the attic becoming a ventilated passage. The long side, which faces the green area with trees, is characterised by two large windows obscured by wooden brisesoleils with home automation control. The opposite side constitutes the entrance to the house. The interior spaces of the two bedrooms and the bathroom have been developed around the common entrance area. What distinguishes it from prefabricated modular architecture is the careful design and attention to detail that frees it from the rigid minimalist form of the parallelepiped.

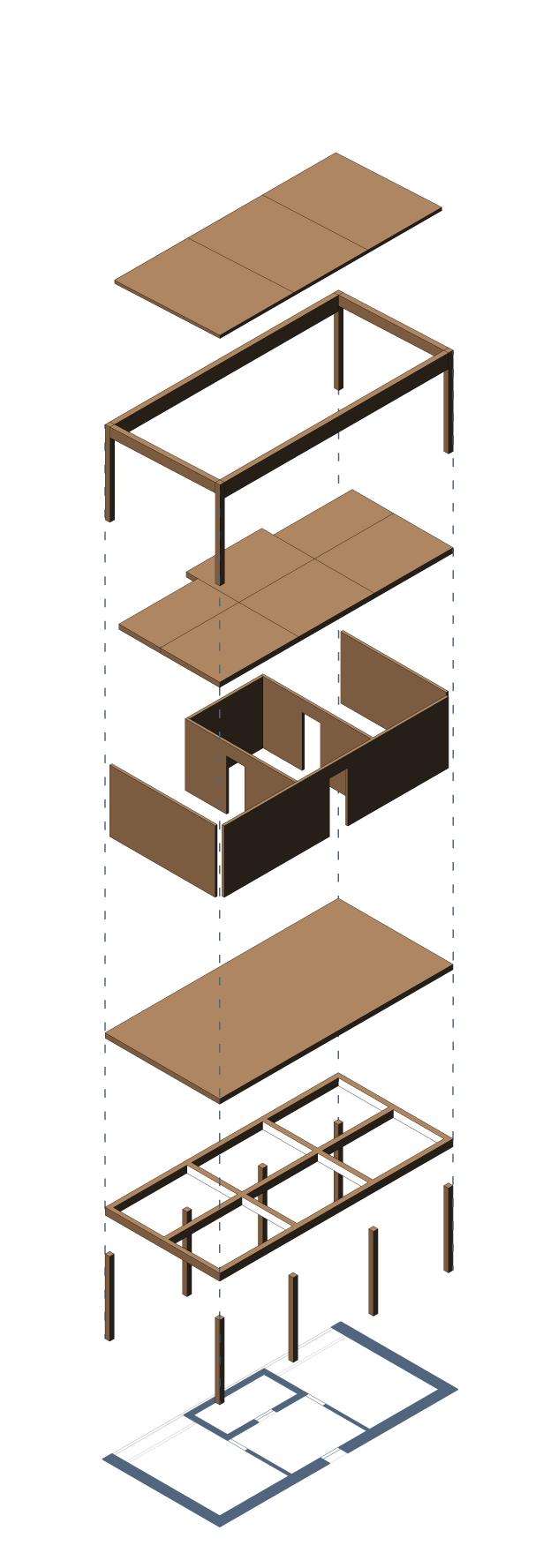

Esploso assonometrico delle teche espositive. | Axonometric exploded view of the project.

53

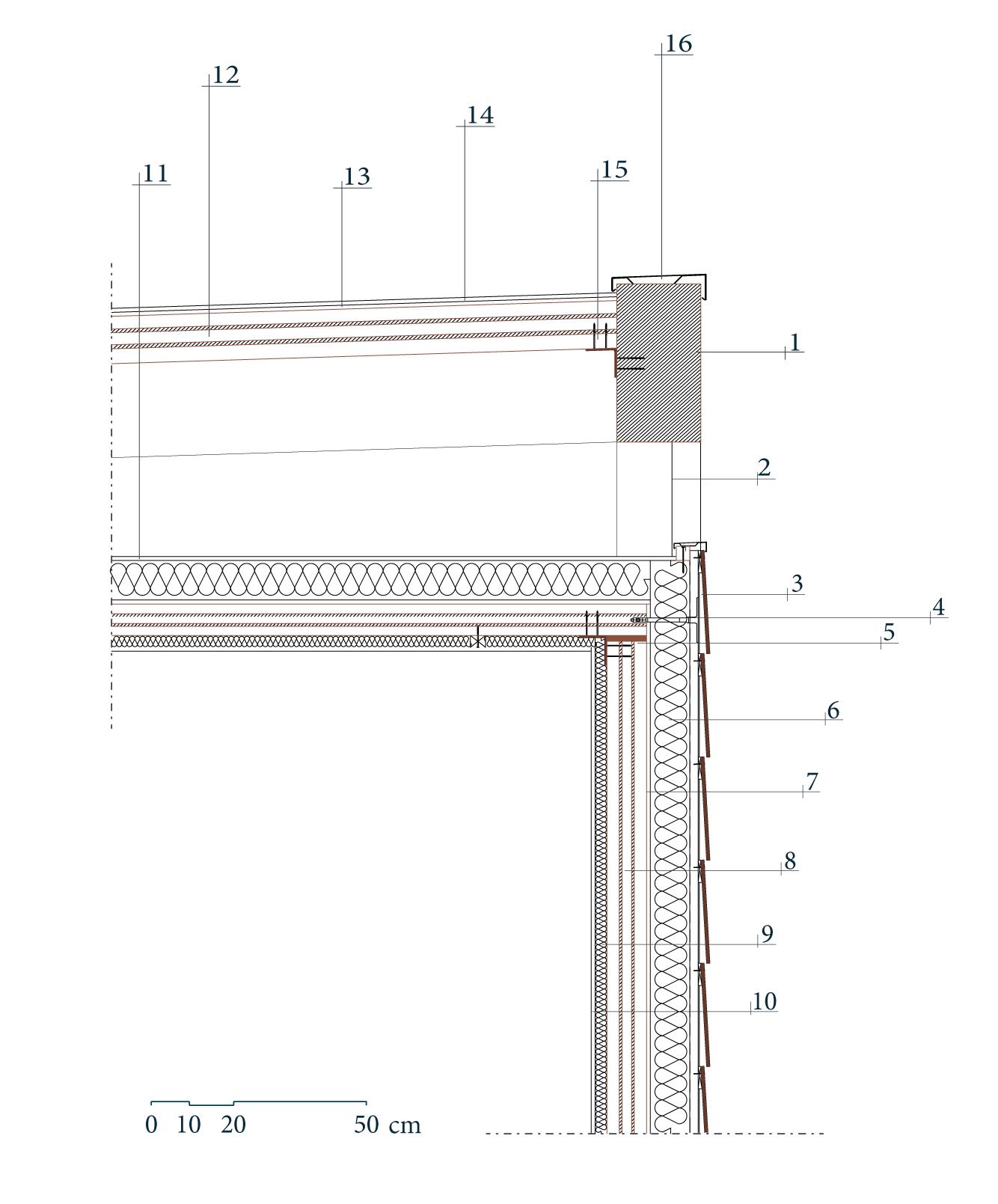

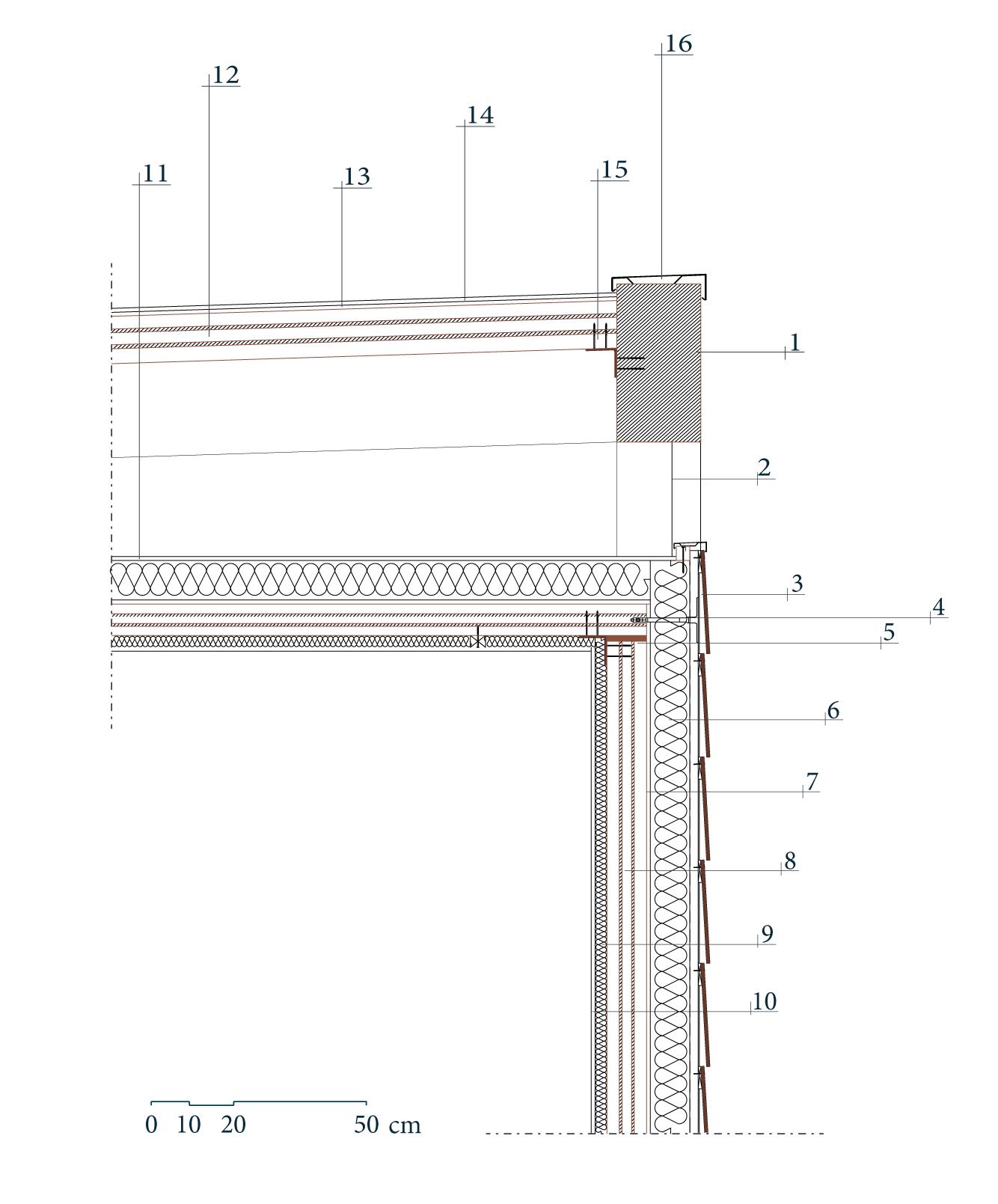

.1 Trave in legno lamellare 0.4x0.2 m

.2 Rete antivolatili

.3 Rivestimento esterno in doghe di legno

.4 Tassello per ancoraggio

.5 Guarnizione per tenuta all’aria

.6 Isolante

.7 Barriera al vapore

.8 Xlam 3s 100 DL

.9 Isolante in fibra di legno

.10 Cartongesso

.11 Guaina impermeabilizzante

.12 Xlam 3s 120 DL

.13 Guaina impermeabilizzante

.14 Pannello coibentato

.15 Angolari metallici di giunzione

.16 Scossalina in lamiera metallica sagomata

La disposizione planivolumetrica dei vari edificati, con la creazione di vicoli stretti tra di essi, è stata pensata per migliore il comfort ambientale creando dei veri e propri tunnel d’aria. Comfort ambientale che tra i principali scopi progettuali e perciò la scelta tecnologica e la progettazione dei singoli moduli assumono un forte rilievo.

Per far fronte al clima caldo e temperato è stato progettato un sistema di ‘vele’ come copertura in alcuni punti dello stoà di acciaio, permettendo un riparo con la creazione di alcune zone d’ombra. Un sistema con controllo domotico che garantisce un facile controllo, in relazione al soleggiamento.

Legno, acciaio e reversibilità: nuove forme e tecnologie per l’originaria Ascalona.

The planivolumetric arrangement of the various buildings, with the creation of narrow alleys between them, was designed to improve environmental comfort by creating authentic air tunnels. Environmental comfort is one of the main design goals and therefore the choice of technology and the design of the individual modules highly significant.

In order to cope with the hot climate, a system of ‘sails’ was designed as a cover in some parts of the steel stoa, allowing for shelter with the creation of some shaded areas. A system with home automation control that ensures easy control depending on the sunshine.

Wood, steel and reversibility: new forms and technologies for the original Ascalona.

55

pagina precedente / previous page Dettaglio costruttivo del modulo del think tank. | Construction detail of the think tank module.

Esploso costruttivo del modulo del think tank e relativa pianta. | Exploded view of the think tank module and its floor plan.

Vista di progetto da Ovest. | West view of the project.

Postfazione Afterwords

Andrea Ricci Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Firenze

Il percorso di ogni progetto di architettura, indipendentemente dalle scelte figurative e dagli esiti formali dello stesso, è determinato dall’intreccio “compositivo” per cui un programma più o meno articolato di esigenze di ordine funzionale ( intese estensivamente dalla dimensione pratica a quella simbolica) si pone in relazione alla specificità di un “luogo” che si qualifica attraverso la sua capacità di fissare nella sua natura il lascito, reale e/o ideale, degli eventi della storia umana. Il progetto di tesi di Sara Masi non fa eccezione. Nell’area archeologica di Ashkelon soltanto le alcune testimonianze monumentali sono state oggetto di scavi sistematici e sono attualmente visibili nelle poche parti superstiti (in sostanza solo la basilica romana ed il circuito delle mura urbiche). La maggior parte dell’antico spazio urbano è ancora scarsamente indagato e solo parzialmente conosciuto per singoli frammenti Tutta area è oggi compresa in un grande parco posto ai margini della moderna Ashkelon, forse più attrezzato per ospitare i pic-nic dei turisti e/o per la gestione di eventi, che non per valorizzare il patrimonio storico del luogo. Nemmeno esiste una adeguata struttura museale in città, dal momento che, a quanto mi risulta, l’esposizione pubblica dei locali reperti archeologici si limita ad alcune vetrine collocate nell’atrio dell’Ashkelon Accademic College, la locale sede universitaria. Da tali premesse discende una chiara scelta programmatica del progetto. L’intervento all’interno della città antica non poteva essere concepito soltanto come un’efficiente struttura logistica di servizio all’attività di scavo, una “cittadella” destinata a studiosi ed archeologi, magari un po’ defilata rispetto ai flussi del turismo dei campeggiatori e dei bagnanti. Un progetto di architettura dovrebbe, al contrario, tenere insieme le diverse esigenze postulate dal “luogo”: la necessità di studiarne la storia (attraverso l’indagine archeologica dallo scavo alla fase di analisi interpretativa), la necessità di mostrarne la storia (attraverso una pubblica esposizione del reperto fin dalla sua fase di studio) infine, la necessità di usarne positivamente la storia (attraverso la flessibilità di un sistema in grado di veicolare interazioni di reciproco vantaggio fra diverse modalità di fruizione dell’area). La chiave figurativa capace di comporre (cioè tenere insieme in termini compositivi) tali complessità, si cela proprio in quel concetto di “luogo” che comprende in sè, ma anche trascende, il dato fisico. Ovviamente esiste una dimensione planimetrica/altimetrica con cui non può non confrontarsi qualsiasi progetto, pena la sua irrilevanza ed ineffettualità, ma il “luogo” incarna soprattutto l’idea di quella continuità progettuale che, attuandosi nel sito attraverso la storia, diventa di fatto il fattore qualificante di una riconoscibilità figurativa del sito stesso. In tale stratificazione narrativa la memoria di

ciò che è stato può abitare accanto agli sviluppi di ciò che, plausibilmente, avrebbe potuto essere. Appare allora legittimo che, fuori da ogni accertata “verità” archeologica, il progetto “inventi” le proprie ragioni figurative all’interno di una memoria plausibile, anzi oggettivamente assai probabile, come la parziale rappresentazione di Ashkelon romano-bizantina presente nella mappa mosaicata di Madaba. Nel frammento di tale mosaico, purtroppo mutilo, due decumani porticati si dipartono dalla Porta di Gerusalemme, l’uno a scendere verso il mare, l’altro a salire verso il tell meridionale. L’idea d’ordine che strutturava la città antica definisce una matrice spaziale che, oggi, può strutturare anche l’impianto planimetrico del progetto all’interno di una precisa “volontà” urbana. Essa è tanto forte nell’affermare la necessità del gesto ordinatore, quanto contemporaneamente consapevole dell’impossibilità di dare ad esso compimento. I “nuovi” decumani sono strumenti figurativi “antichi” che connettono complessità ed ambiguità del sito, disegnando, fuori da ogni mimesi formale, la riconoscibilità del luogo. Essi creano le condizioni affinché le diverse istanze funzionali comprese nel programma di progetto possano non solo disporre degli spazi necessari, ma anche interagire all’interno di un sistema unico, capace cioè di agevolare situazioni di scambio e condivisione tra i vari ambiti. I luoghi della ricerca a servizio dell’attività archeologica di scavo sono contigui ai percorsi di un variegato flusso turistico: da un lato studiosi ed archeologi possono svolgere il proprio lavoro senza doversi isolare all’interno di un “museo”, dall’altro ogni visitatore del parco, sia esso campeggiatore, bagnante o sportivo, è inevitabilmente coinvolto nell’offerta culturale del sito, cioè la fruizione visiva dei reperti in deposito, senza dover mai compiere l’atto di entrare in un “museo”. La questione non riguarda tanto la fisicità degli spazi progettati, quanto le relazioni di un sistema che il progetto struttura in termini di ideale recupero della memoria “urbana” del sito antico, seppur nell’ottica del frammento. È vero che il progetto rappresenta sempre il momento deputato a confrontare le soluzioni tecniche più opportune e/o meno invasive per ottimizzare la funzionalità e/o sostenibilità degli interventi in relazione al contesto. È però altrettanto vero che un progetto d’architettura non è soltanto questo: uno specifico strumento operativo atto a fornire risposte tecniche a problemi contingenti. Perseguire una sorta di “comodità” d’uso nelle varie scelte progettuali rappresenta un logico, forse necessario, obiettivo di programma, ma il fine ultimo cui deve tendere l’architettura è la costruzione di “luoghi”. Questa idea sottende tutto il percorso figurativo del progetto di tesi, anzi, di fatto, “è” il progetto di tesi il resto è mera questione “di mestiere”.