16 minute read

on a Digital Nomad Running Fundraiser

from Village Tribune 127

Running Tara Lepore Fundraiser A local student will be running 13.1 miles through Tribland in fancy dress to raise money for Meningitis Research Foundation.

Advertisement

Tara Lepore, 24, will run a half marathon at the end of March to attempt to raise £400 for the charity. She plans to run through Maxey, Etton, Glinton, Peakirk and Northborough as part of her 13.1 mile (21km) route in the last weekend of March. She is currently on track to raise a total of £3,490 for Meningitis Research Foundation, a charity aiming to eradicate meningitis globally by 2030. Her final fundraising challenge will be trekking to Machu Picchu in Peru in June 2022. Tara is a psychology student at Nottingham Trent University but is living at home in Market Deeping during the national lockdown. “I grew up in Etton so thought it would be fun to complete this charity fundraiser in my old stomping ground, The purple tutu should hopefully raise a smile or two when I’m out - please say hello or beep your car horn in support if you see me running through the villages that weekend!” She told the Village Tribune.

St Martin’s High St, 1960s (Wilfrid Wood of Barnack)

Stories from the

South Bank by Dr Avril Lumley Prior Pushing the Boundaries to Stamford Baron

The River Welland rises in the Hothorpe Hills near Sibbertoft (Northamptonshire), flows through Rockingham Forest to the Fens, forms the northern boundary of Tribland and empties into the Wash at Fosdyke. Until the sixteenth century, it was navigable as far as Stamford. And it is there, that we are going to do as the sign bids and ‘stay awhile’, exploring Stamford Baron (aka Stamford St Martin) south of the river, which like the rest of the town is jam-packed with history and ‘ancient charm’

Battles, burhs and bottle-necks

The Welland Valley has been exploited since prehistoric times and possibly indicated the boundary between the Iron-Age Corieltauvi and Catuvellauni tribes. The prehistoric track now called the Jurassic Way can be traced down the present Pinfold Lane (behind the Garden House Hotel), crossing the river near the George Bridge onto Castle Meadows, continuing over

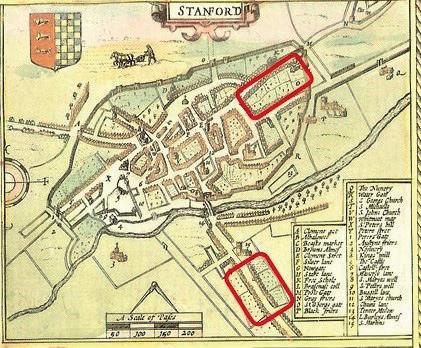

Lammas Bridge, along Castle Dyke to Red Lion Square and on to Scotgate (the way to Scotland). By 1086, it formed a stretch of the main London-toEdinburgh route (known from the 1600s as ‘The Great North Road’) and remained so until 1960, when it was bypassed by the A1. (I vaguely remember from childhood trips to Surrey the traffic-jams that afforded me my first glimpses of a town full of quaint houses and lofty churches that lured me back again and again!) By 50AD, Roman engineers had completed this section of their London-to-York super-highway, Ermine Street, connecting the forts at Water Newton (Durobrivæ) on the River Nene and Great Casterton on the Gwash, a tributary of the Welland. It passed through Burghley Park, along Wothorpe Road, crossing the Welland west of the Jurassic Way over a ‘stone ford’ that eventually gave the settlement its place-name. Here Queen Boudicca and her Iceni warriors reputedly pursued the hapless Ninth Legion after sacking Verulamium [St Albans] and Londinium [London], in 60AD. However, it was not really until c.877 that events in Stamford began to be reported. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles reveal that, after the Scandinavian invasions, it became one of Five Boroughs of Danelaw together with Derby, Leicester, Lincoln and Nottingham. Each was ruled by a Danish jarl (earl), who in turn was subject to the chief jarldom of York, and was governed and taxed on Danelaw terms. A burh (stronghold) was constructed on the Jurassic limestone terrace north of the river, stretching roughly from the site of Marks’ & Spencer’s as far as Red Lion Square and seemingly respected the pre-existing Anglo-Saxon settlement to the west.

In 918, Alfred the Great’s son, Edward the Elder, king of Wessex (899-924), resolved to gain control of the rest of England. So, he left his indomitable sister, Æthelflæd, ‘the Lady of the Mercians’, in charge at home. Then, according to the original and somewhat-biased Winchester

River Welland at Stamford

‘Boudicca’s’ Ford

John Speed’s Map of Stamford showing the burhs (1612)

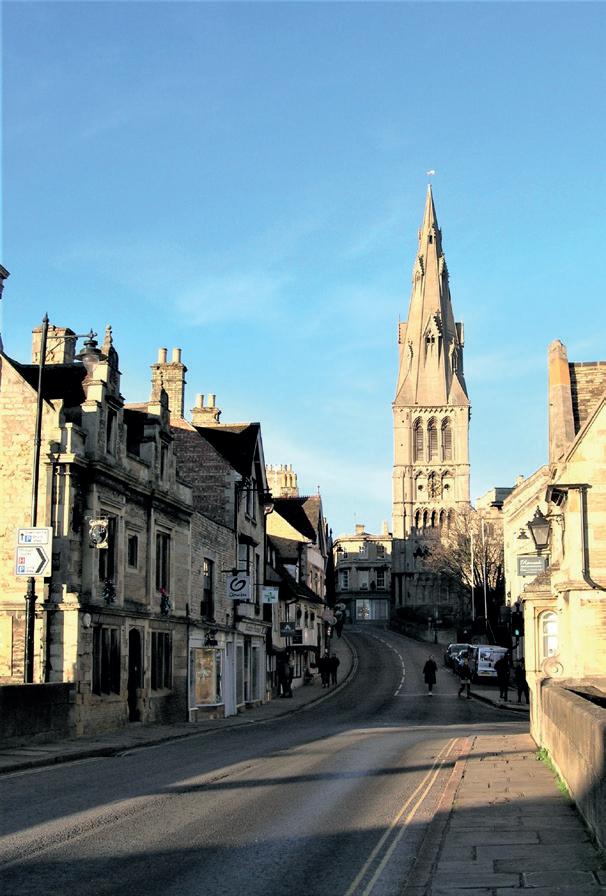

St Martin’s church with the boundary of the burh on left The Great North Road through Stamford

version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (commissioned by their father), ‘Edward went with an army to Stamford, and ordered a burh to be built on the south side of the river; and all the people who belonged to the morenortherly burh submitted to him and sought him as their lord.’ I doubt if the Danish debacle were as simple as that! It is possible to plot most of the outline of Edward’s stronghold. Park Lane follows its eastern boundary with Burghley [the ‘clearing by the burh’]; Pinfold Lane marks part of the western limits, whilst St Martin’s churchyard wall suggests its northern periphery. The Jurassic Way was diverted to make the Highgate [High St] the burh’s axial route, leading to the tenth-century river-crossing at the Welland’s narrowest point. This deviation explains the road’s circuitous course north of the Welland before joining Scotgate. Having secured his kingdom, Edward organised it into shires for administration purposes. Of the Five Danish Boroughs, Derby, Leicester, Lincoln and Nottingham all became county towns. Although there are a few references to ‘Stamfordshire’, its estates and privileges were lost to Lincoln. Indeed, Stamford straddled three counties: Northamptonshire [now Lincolnshire] comprising Edward’s burh, Lincolnshire with its Danish burh and Rutland to the west, where Rutland Terrace now stands. Nevertheless, Stamford thrived under the rule of Edward and his son, Æthelstan (924-39). North of the Welland, there was significant Saxo-Norman pottery industry, where fine glazed-ware was crafted for domestic use and export until the late-thirteenth century. On the south bank, was a mint, employing 52 moneyers, the fifth most important in the country after London, Lincoln, Winchester and York. It was operating until at least 1146.

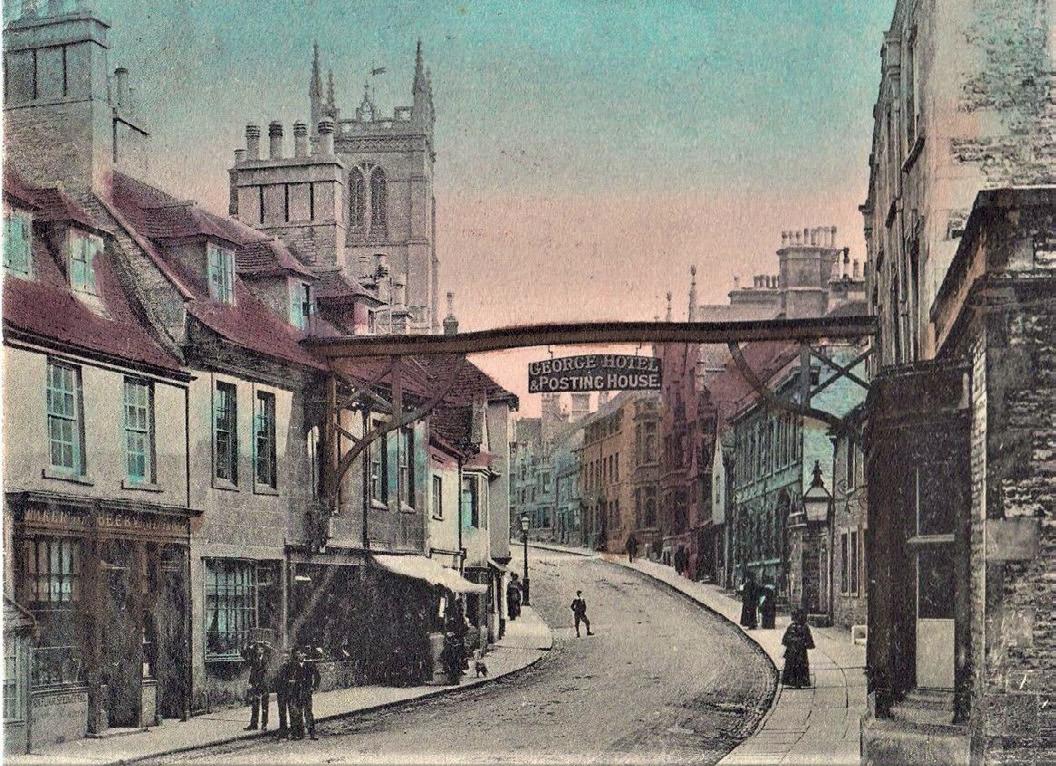

St Martin’s High Street, c.1905

St Martin’s High St, 2020

Walls, wharfs and the wool-trade

After the Norman Conquest, William I raised his castle north of the river and appointed the cudgel-wielding military monk, Turold de Fécamp, as abbot of Peterborough confirming to his monastery lands in Stamford ‘across the bridge’ [later the Barony of Stamford or Stamford Baron] and the right to levy tolls. The town continued to flourish, owing its success as a tradingcentre to its position on a major road and navigable waterway and the demand for grain and quality wool from the backs of Leicestershire and Lincolnshire sheep. By the early-1200s, a large proportion of fleeces was transported by boat to Boston and King’s Lynn and thence to Flanders; the rest was woven into a fine twill called haberget. The mid-Lent Wool Fairs attracted merchants from as far away as western Europe. Unlike most other produce, wool was exempt from taxation; so, the wily tenants of Stamford Baron sold bread from their windows to avoid paying the market tariffs ‘over the water’!

Later in the thirteenth-century, the town walls (of which little remains) were reconstructed north of the river, causing the land beyond to be referred to as Stamford Without. People entering the town from the south were confronted by the Bridge Gate, which housed the town hall and gaol. Revamped in 1558, it was finally dismantled in 1776/77, when the road was turnpiked and the Council relocated to an impressive edifice on St Mary’s Hill. The wealthiest residential areas of medieval Stamford were north of the Welland whilst wharves lined the south bank. Yet, Water Street parallel with the river (known during the thirteenth century as Este-by-the-water), boasted a row of substantial, stone merchants’ houses too. Those excavated during the 1960s revealed crypt-like cellars, slab-floors, indoor privies with soakaways, built-in ovens and backyards.

Burghley Almshouses

Old East Station House

Towards the end of the thirteenth century, Stamford was suffering a decline in fortune caused by a chain of cataclysmic events, beginning in 1290 with the expulsion of the Jews, who were renowned as money-lenders especially for municipal projects. From 1312 onwards, came a series of harsh winters and cold, wet summers, resulting in crop failure, cattle disease and famine. The Welland burst his banks, flooding the cellars of the Water-Street properties, after which they were infilled. The 1348/9 visitation of the Black Death had devastating financial consequences and the relocation of the wool-trade to East Anglia and undercutting by Flemish weavers must have been deemed as the final nails in Stamford’s coffin. Still more disasters were in store. In 1461, during the Wars of the Roses, the town was besieged by the Lancastrians. A century later, the river had silted up, rendering Stamford only accessible to shallow-draught vessels. When Henry VIII’s surveyor, John Leland, visited c.1541, he described the ‘onceprivileged’ town as a ‘decay’d’, though at least one of the medieval houses on Water Street survived until the nineteenth century with others making way for maltings and the workhouse. During reign of Elizabeth I (15581603), her High Treasurer and advisor, William Cecil First Baron Burghley (1520-97), depopulated his village to build his mansion and create Burghley Park on land acquired by his father, Sir Richard (c.1495-1553). Their presence was unpopular in Stamford as they bought rundown properties at knockdown prices and meddled in local politics, albeit sometimes for the greater good. Burghley Almshouses, the ‘Bottle Lodges’ (1803), the Estate Office at 61 St Martin’s High Street are reminders of the Cecils [later Marquises of Exeter] abiding influence. Justifiably, the Second Marquis, Brownlow Cecil, refused to allow the Great Northern Railway London-to-York line to blight his park. When the Peterborough-Grantham section completely bypassed the town, he invested in the Stamford and Essendine Railway (dubbed ‘The Marquis of Exeter’s Railway’) which opened in 1856 linking it with the mainline. Brownlow commissioned a tunnel beneath St Martin’s High Street so that the track did not cross the Great North Road (near the Antiques Centre) and stipulated that the East Station in Water Street resembled an Elizabethan mansion. The line closed in 1959. Stamford’s second station, also south of the river, originally served the Syston and Peterborough Railway, a branch of the Midland Counties Railway, which opened in 1846 and now forms part of the Birmingham-toStansted route.

William Cecil’s Tomb (1598)

Burghley Almshouses’ medieval foundations

Saving souls, soothing bodies and salving consciences

Situated on a ‘trunk road’, Stamford Baron was frequented by pilgrims (heading for saints’ shrines at Walsingham, York, Canterbury and beyond), soldiers, bishops, monks, merchants, vagrants, government officials and even royalty. Edward I (12721307) held court in Stamford, lodging at St Leonard’s Priory west of the town. Moreover, the cortège of his beloved Eleanor of Castille rested in here on its progress from Lincoln to London, prompting him to erect an ‘Eleonor Cross’ in her memory on Casterton Road.

Stamford Baron already supported two churches, three chapels, a nunnery, leper hospital and various hostelries run by religious communities. By 1146, Peterborough Abbey owned 59 houses and both churches. Presiding over High Street is St Martin’s (patron of soldiers), whose predecessor may have existed since Edward the Elder established his burh. During the Middle Ages, it contained a guild chapel where prayers for past and present members were offered. The guild also maintained a bull to participate in the St Brice’s Day Bull-Run, which was abolished after 600 years, in 1839. St Martin’s was restored shortly after the Lancastrian siege and was adopted as the Lords of Burghley’s burial-place. Peterborough Abbey’s other church, All Saints,’ stood at the south-east corner of the rivercrossing and was referred to by the Lincolnshire townsfolk as ‘All Saints’-beyond-the-bridge’. Its congregation had dwindled by the fifteenth century with its stalwarts diverted to St Martin’s. Pizza Express currently occupies the site.

Three of Stamford’s eight or so ‘hospitals’ fronted St Martin’s High Street. They were not infirmaries in the modern sense but more like medieval Travellodges. West of the bridge (Station Road) was the Hospital of St John the Baptist and St Thomas [Becket] the Martyr. A cell of Peterborough, it housed a band of monks whose mission was to provide succour for the poor and homeless, hospitality to travellers and collect tolls for the upkeep of the bridge. The complex maintained two chapels where prayers (and donations) could be offered for safe journeys and/or successful enterprises. The institution was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1547 and eventually purchased by William Cecil, who raised his almshouses on its foundations shortly before his death in 1598. St Thomas’ chapel was demolished but ‘St John-onStamford-Bridge’ endured until the road was turnpiked in the 1770s.

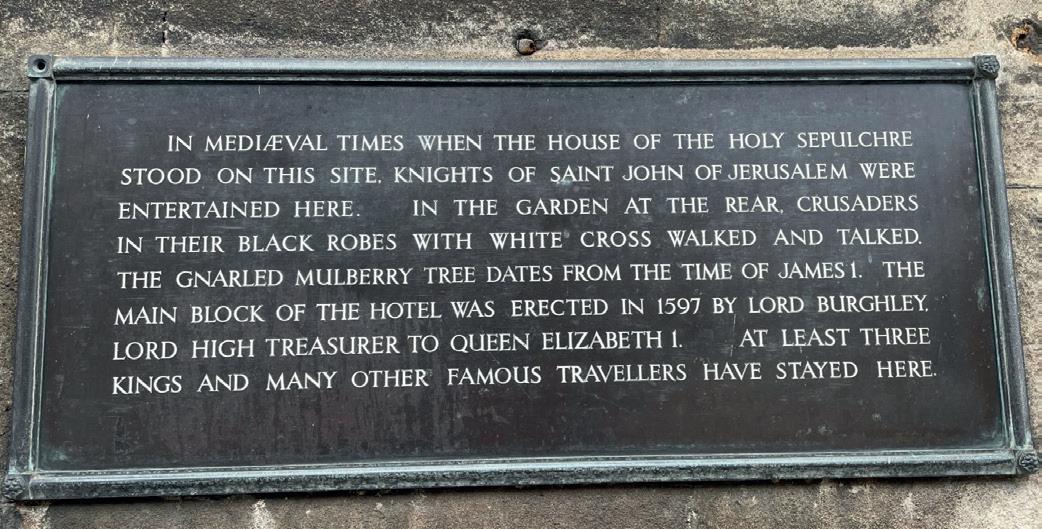

On a building formerly known as ’The Hermitage’, now part of the George Hotel, is a plaque inspired by Stamford historian, Francis Peck (1692-

Sign: George Hotel

The plaque proclaims that the site was occupied by ‘The House of the Holy Sepulchre’ and patronised by the Knights of St John of Jerusalem (alias the Knights Hospitallers), giving the impression that it represented the up-market end of pilgrim-tourism. In reality, members of the order, would have been too embroiled in providing hospitality for pilgrims bound for Christ’s tomb (The Holy Sepulchre) to relax in the gardens.

1743). It proclaims that the site was occupied by ‘The House of the Holy Sepulchre’ and patronised by the Knights of St John of Jerusalem (alias the Knights Hospitallers), giving the impression that it represented the up-market end of pilgrimtourism. In reality, members of the order, would have been too embroiled in providing hospitality for pilgrims bound for Christ’s tomb (The Holy Sepulchre) to relax in the gardens. Yet, despite the nineteenth-century façade, the hotel has a medieval core, and was known as le George (another knightly saint) as early as 1536, when it was leased from Peterborough Abbey by Richard Cecil.

Other antiquarians, like William Stukeley (1687-1765), claimed that the Holy Sepulchre’s chapel was opposite St Martin’s Church, and dedicated in the honour of St Mary Magdalen, a saint venerated by the Knights Templar, whose role was to protect pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land and who also owned property in Stamford. If so, the Templars did not stay long. By 1189, the hospital was run by Austin Canons helping lowly pilgrims reach Jerusalem but had vanished from records by 1227. Curiouser and curiouser! On the outskirts of town and society (opposite the ‘Bottle Lodges’) was St Giles’ Leper Hospital, of which only earthworks survive. Its function was to accommodate sufferers who probably contracted the disease whilst on a Crusade or pilgrimage. It too was sponsored by Peterborough Abbey which kept a standing army of knights, one of whom was Robert de Torpel who died of leprosy in 1147.

St Michael’s Nunnery was founded in 1155 by William de Waterville, Abbot of Peterborough, roughly on the site of Stamford station. Initially, it accommodated 40 sisters and, unusually, several monks and a prior, and was financed by property rentals and revenue for St Martin’s church. Numbers diminished after the Black Death until by 1535, the convent comprised just four nuns, a chaplain and fifteen servants! After the Dissolution of the monasteries in 1539, Richard Cecil bought the conventual buildings and estates south of the Welland. In 1541, Stamford Baron/St Martin and Rutland were enveloped in the diocese of the newly-established Peterborough Cathedral and remained there until 1990, contrary to all the other Stamford churches, which were with Lincoln. Within a century, coaching inns replaced hospitals, especially after the opening of the Stamford Canal, in the 1670s, and improvements to the Great North Road revived the town’s prosperity by attracting investors and visitors. Guests at Stamford Baron’s hostelries included two exceedingly-different Daniels. In 1724, Daniel Defoe, whilst researching his Journey Round

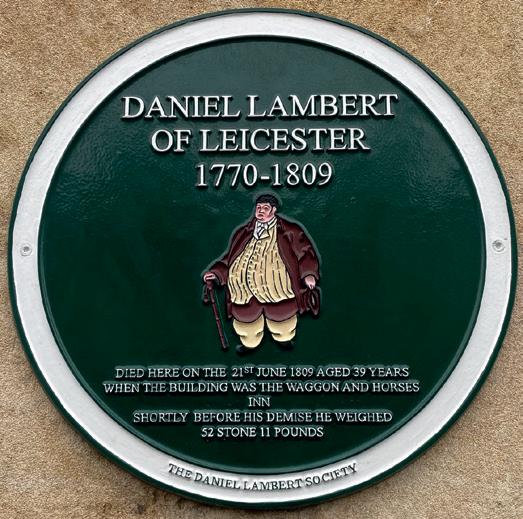

Memorial to Daniel Lambert St Martin’s High St, 2020

the Whole Island of Great Britain, declared that The George Hotel was ‘one of the greatest inns in England’. The less-fortunate Daniel Lambert, a redundant gaoler from Leicester who held the dubious title of the ‘fattest man in England’, died aged 39 at the Waggon and Horses at 47-50 High Street on 21 June 1809 after attending Stamford Races. Weighing in at 52 stones 11 pounds (335 kg) and with a girth of 9 feet 4 inches (284 cm), he had made his fortune by exhibiting himself at sporting events. His coffin required 156 square-feet (14.4 squaremetres) of timber and ‘upwards of 20 men’ to manoeuvre it into the grave in St Martin’s burialground. Over two centuries later, Daniel Lambert is remembered with affection in both Stamford and his birth-place and, in 2009, was deemed by the Leicester Mercury to be ‘one of the city’s most treasured icons’.

A town divided?

It is easy to perceive Stamford as two separate entities divided by a river. The Welland was, perhaps, an Iron-Age tribal boundary; it marked the northern limits of Peterborough Abbey’s jurisdiction, possibly, as early as the lateseventh century, and the southern limits of Danelaw by the ninth. In 918, two rival burhs faced each other across a ford here. Although outcome was peaceful, Stamford was carved up among three counties, stayed so until 1972 and was held by assorted landlords - and royal ladies. From 1541 until 1990, the ‘Borough’ and Stamford Baron lay in different dioceses. Yet, as we have witnessed, their past is inextricably intertwined and ‘Borough’ and Baron are together but genially apart. Hopefully, it won’t be long before we are free to return to Stamford and ‘stay awhile amid its ancient charm’, enjoy refreshments, shop and soak in the atmosphere, architecture and history on both sides of the River Welland.