21 minute read

Heritage

from Village Tribune 128

George Cruikshank, ‘The Bottle’, Plate 5 (1847) As Cold as Charity Below the breadline in old Tribland

by Dr Avril Lumley Prior

Advertisement

Care of the vulnerable is tenet of most religions - and for many people who embrace no faith too. This recently has been demonstrated by the generous donations to food banks and the sterling efforts of volunteers who provide nutritious meals for those struggling during Lockdown and run shelters for the abused and homeless. We are familiar with Jesus’ parable of the gentleman from Samaria who tended a Jewish mugging victim whilst his fellow countrymen scuttled by on the other side of the road. Thank goodness, we still have so many ‘Good Samaritans’ left in the world.

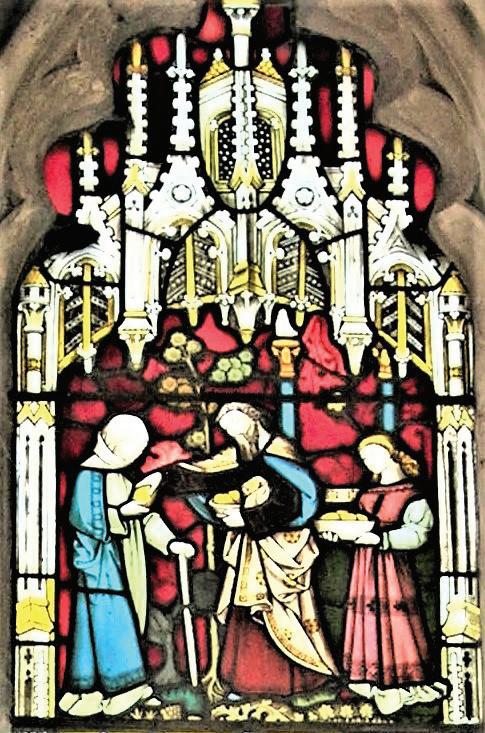

Sutton: Good Samaritan (1867)

Care of the vulnerable is tenet of most religions - and for many people who embrace no faith too. This recently has been demonstrated by the generous donations to food banks and the sterling efforts of volunteers who provide nutritious meals for those struggling during Lockdown and run shelters for the abused and homeless. We are familiar with Jesus’ parable of the gentleman from Samaria who tended a Jewish mugging victim whilst his fellow countrymen scuttled by on the other side of the road. Thank goodness, we still have so many ‘Good Samaritans’ left in the world. Creature Comforts?

The New Testament is peppered with acts of Christian charity with converts disposing of their wealth to help the poor. Three centuries later, Sulpicius Severus wrote about St Martin of Tours (317-71), a Roman soldier who gave half his cloak to a mendicant. Closer to home, Bede the ‘Father of English History’ told how King Oswald of Northumbria (634-42), after resolutely fasting throughout Lent, surrendered his Easter Sunday feast complete with silver salver to beggars at his gate. ‘Corporal Works of Mercy’ (feeding the hungry, giving water to the thirsty, clothing the naked, offering shelter to travellers, visiting the sick and imprisoned and burying the dead) became popular themes for medieval wall-paintings and Victorian stained-glass windows. Nowadays, Social Services are theoretically the ‘safety-net’ for the impoverished and at-risk, crucially assisted by registered charities. However, in medieval Europe, these duties were performed mainly by religious houses. A monastery official called an almoner was tasked with doling out alms in the form of food and in extenuating circumstances clothing and small amounts of money to the penniless. At Peterborough Abbey, his department [the almonry], was funded by rents from various houses and shops in town, profits from woodland at Eastwood and Westwood and the manors of Sutton, Gunthorpe, Paston and part of Maxey. The almonry hall was situated near the precinct’s East Gate (now opening onto Bishops’ Road Gardens), strategically placed so that beggars queued at the monastery’s back door instead of lowering the tone of its market-place entrance. Aged and poverty-stricken men of good character found shelter in ‘hospitals’ (often called bedehouses) established by religious orders, craftsmen’s guilds or individuals like woolmerchants, William and Margaret Browne, who financed Browne’s Hospital in Stamford, in 1475. There, twelve male inmates slept in cubicles in a communal hall, with two resident widows of equally-impeccable reputation at their beck and call, preparing meals, washing their garments and nursing them when they fell ill. In return, the bedesmen offered daily prays for the souls of their benefactors in the adjoining chapel.

Barnack: Clothing the naked (1869) Peterborough: The Almonry at the East Gate

The Call to Alms

In the countryside, ‘works of mercy’ were carried out at parish level with the priest ostensibly donating a third of his tithes [land taxes] for congregants in dire straits. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in 1539 and the abolition of Guilds by his son, Edward VI, in 1547, the welfare system completely collapsed. The plight of the poor became so critical that clergymen were instructed to collect alms from their parishioners, some of whom were living on the breadline themselves. In 1572, during Elizabeth I’s reign, every parish had both an appointed Alms Collector and a Supervisor of the Labour of Rogues and Vagabonds, whose job-description was to assess and extract ‘poor-rates’ from those who could afford to pay, move on vagrants whether seeking work or not and force home-grown layabouts to find gainful employment. The two offices combined in 1597 under the title of Overseer of Poor, a dubious honour bestowed upon Church Wardens by the Poor Law Act of 1601. Bedehouses were reinvented as almshouses and run along similar lines. Attendance at chapel was still compulsory, though prayers now were said for Queen and Country as well as for benefactors. In 1597, Elizabeth’s chief advisor and High Treasurer, William Cecil of Burghley rebuilt the Hospital of St John and St Thomas in Stamford St Martin as Burghley Almshouses. At Marholm, William Fitzwilliam removed the priest and re-instated his father and namesake’s bedehouse as almshouses [now Alms Cottages] for ‘four poor secular men’. Meanwhile, in Millstone Lane, Barnack, the fifteenthcentury chapel and hall of the Guild of Corpus Christi also

Ufford: Walnut Barn 'To six Decayed Gentle Women’

Bainton’s old school (opened 1820)

were remodelled as almshouses [now Ffeoffes’ Cottages]. In fact, during Tudor times it became de rigour for the wealthy to help those who had fallen upon hard times. ‘Charity begins at Home’

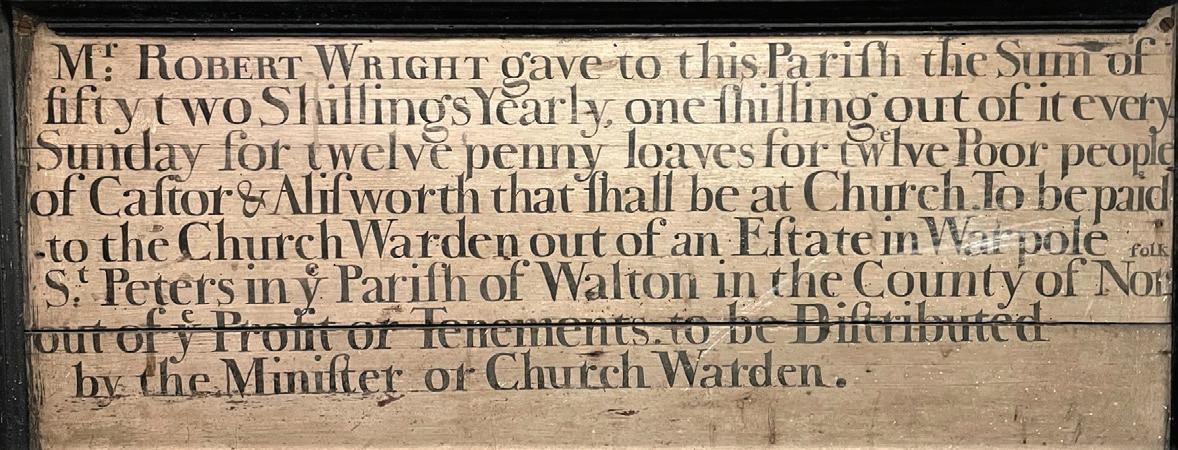

Wills, Church Wardens’ Accounts, blatant manifestations and, after 1894, Parish Council Minutes Books reveal numerous charities set up to care for the sick and financially distressed in the community. In 1724, the executors of widow, Ruth Edges’, estate placed a tablet on the gable of Ufford’s Walnut [Tree] Farm barn declaring that rents from the property went to aid ‘six Decayed Gentle Women For ever’. In 1734, Mr Robert Wright boasted on a board in St Kyneburgha’s church that he had given lands yielding 52s a year for ‘twelve penny loaves every Sunday for Twelve poor people of Castor & Ailsworth that shall be at Church’. Other patrons were more modest but their benevolence sometimes had strings attached. Henry Walton, ‘gentleman’ of Borough Fen (c.1749-1800), who tragically lost his nine children in infancy, bestowed the interest on an annuity of £100 for the upkeep of his tomb and a row of family gravestones in Peakirk churchyard. The remainder, henceforth named ‘The Walton Charity’, went to poor folk who were not already receiving relief. Mary Barnard, widow of incumbent Reverend Benjamin Barnard (1801-15) had the same intention, when she left £109 for fuel for the poor on condition that her husband’s tomb was maintained. The two Peakirk charities combined and were managed by trustees until the 1894 Charitable Trusts Act transferred their role and that of Peakirk Provident Society (formed in 1853 ‘to relieve the sick and destitute of the village’) to the Parish Council. In 1898, Reverend Edward James (1865-1912) set up a further charity in memory of his wife, Emily, again to benefit the poor. Groceries and fuel continued to be distributed until the winter

Castor: ‘Penny loaves’

Peakirk: Henry Walton’s Tomb

of 1964/65 when 39 hundredweights of coal were given to 15 households. Most villages had similar schemes in place. Widows were remembered at Ufford, in 1702, by George Quarles, Reverend John Browne and a Mrs Hangar. In 1662, the Brownes of Walcot Hall purchased land to benefit the poor of Barnack. In 1723 Elizabeth, Dower Duchess of Exeter invested in reclaimed land at Newborough and Borough Fen to aid the needy at Maxey and Deeping Gate. In 1638, William Budd left money in trust to the vicar and church wardens of Marholm for coal for the poor as did Ann Scott for Glinton, in 1870, and Elizabeth Bellars for Maxey, in 1875. Flannel cloth was added to the rations by Charles Mossop and Daniel Webster, in 1858, for Helpston and Etton and by Mary Ann Northey at Castor, in 1900. For anonymous cash donations, there was the church poor-box. The foundation of schools appealed to benefactors as education was seen as a route out of poverty. In c.1686, Reverend Richard Haw of Bainton left annual rents of £51 from parish land for the provision of education (presumably in St Mary’s church) until 1819, when lord-of-the-manor, Sir John Trollope, donated a further £271 and adjacent land for a purposebuilt school. Spinster Ann Ireland (1635-1712) left £100 for a Charity School so that ten ‘free scholars’ from Glinton and five from Peakirk could learn to read in the north aisle of St Benedict’s. A broader curriculum evolved to include writing and arithmetic together with sewing for girls and gardening for boys, in preparation for a life ‘in service’. Too much learning was deemed a dangerous thing and could give brighter pupils ideas ‘above their station’. It was exceedingly-rare for a poor boy to gain a place at a Grammar School and rarer still for his parents to afford to send him.

Begging for money to buy ‘The Bottle’, Plate 4 (Cruikshank, 1847)

Distinction was made between the ‘deserving’ poor (the elderly, widows, orphans, severely-disabled etc) and the ‘undeserving poor’, whose plight was perceived to be caused by the triple evils of fecklessness, idleness and drunkenness. Indeed, the terrible consequences of yielding to the demon drink were portrayed in George Cruikshank’s series of mid nineteenth-century satirical drawings, ‘The Bottle’. Yet, when life was grim and water not fit for consumption, alcohol was a solace. Wherever possible ‘outdoor relief’ was dispensed locally with recipients described as being ‘on the parish’. However, in 1723, an Act was passed encouraging clusters of villages to procure land or property for workhouses to provide ‘indoor relief’ in return for unpaid labour. By 1782, such an institution was operating in Church Street, Werrington, with beds for 14 paupers overseen by the ‘Workhouse Master’. In 1834, all English parishes were organised into 585 ‘Unions’, each with a workhouse controlled by a Board of Guardians of the Poor, who initially were elected by ratepayers and, after 1894, by Parish Councillors. The Werrington institution was converted into a school when Peterborough Union Workhouse opened in Thorpe Road in 1836, with a capacity for 200 souls. The 1881 Census Returns divulge that they came from as far away as Ireland and Somerset but there were Triblanders too, including Stanley Coaten (aged 67), an agricultural labourer from Helpston, orphans Emma (8) and Isabella (11) Goude of Peakirk and Frances Townshend (76) from Castor. Entering the Workhouse was the worst possible scenario for both the unfortunate and his/ her family and for the homeparish, since it was obliged to pay a nominal sum [the Poor Rate] for their ‘indoor relief’ and for burials if they ‘failed to thrive’. Besides having a stigma attached, married couples were separated to prevent workhouses becoming breeding grounds for more dependents for hard-pressed rate-payers to keep. Therefore, only the absolutely-desperate sought admittance. Although usually efficiently-run and the paupers fairly well-fed, workhouses were not Butlins and the Devil finds work for idle hands! Activities for able-bodied men included rock-breaking and bone-grinding (for fertiliser), whilst women toiled in the laundry or kitchens or picked oakum [teasing rope for caulking timber ships], all menial tasks lest they should undercut labourers on the outside. Old ladies were

Werrington Workhouse now a private residence

employed knitting; children were taught to spin and were sent to a nearby school (where they became a target for bullies) or were sold into apprenticeships and often exploitation. ‘As poor as church mice’

Before the meagre Old Age Pension of five shillings [25p] per week was introduced for 70-year-olds of ‘good character’ in 1909, people literally worked until they dropped and died ‘in harness’. My four times greatgrandfather, ancient mariner Robert Wilson (1754-1841), was still putting to sea as a pilot aged 86, presumably rather than go ‘on the parish’ - or worse! Conversely, a large percentage of the working-classes sought ‘indoor’ or ‘outdoor’ relief at some stage in their lives. And, naturally, recipients were expected to show profound gratitude and deference towards their benefactors. Even in church, the poor were required to know their place in the days when better-off worshippers rented their pews. Peakirk’s North Chapel was reserved for the owners of St Pega’s Hermitage, who until 2001, were responsible for its upkeep. In contrast, from their ‘free sittings’ at the draughty ‘low-end’, the less-fortunate were brainwashed from the cradle into believing – and accepting - that their situation was divine ordination. Hence, the dreadful, woefully-‘unwoke’ and now-jettisoned verse of ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’, published in 1848 as one of Mrs Cecil Alexander’s Hymns for Little Children: ‘The rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, God made them, high and lowly, And ordered their estate.’ Inevitably, this hierarchical system deflected many Anglicans to Methodism, a more egalitarian, grass-roots form of Christian worship. ‘The poor will always be with us’

Nonetheless, poverty was regarded by many as a necessary evil in the order of things because it drove people to work, a sentiment ironically endorsed by the ‘idle rich’! Comfortably-off middle-class benefactors, such as ‘yeoman’ farmers, merchants and industrialists could be seen to ‘doing good’ and bask in the glory of their munificence; an attitude contrary to Christ’s teaching that charity should be delivered discretely and without self-aggrandisement (which, to be fair, some philanthropists did). And, of course, the destitute were a cheap source of labour. They performed jobs that those

Peakirk: Boat Inn (1912) By 1932, the Boat Inn on Peakirk’s Thorney Road was in such an advanced state of disrepair that daylight showed through the thatch and holes in the wall were stuffed with newspapers.

who were slightly higher up the social pecking-order baulked at (such as coal-mining, cleaning out cess-pits and standing thigh-deep in urine at the tannery) and, thereby, gave them someone to look down upon. Churchwarden’s Accounts, newspaper reports and Parish Council Minute Books tell us that deprivation, sub-standard living conditions and low regard for the welfare of the poor were still prevalent in the twentieth century. After a visit from the Housing Inspector, in 1912, it was recorded that there were nine rented properties in Peakirk ‘that were in such a deplorable condition that something must be done’ since some were in danger of collapse. Despite the 1919 Housing Act to address the national shortage of adequate accommodation after World War I, as late as 1928 a family of four were living in a stone outbuilding with only a single door and without a yard, water or sanitation for which they were paying 6 shillings [30p] a week rent. By 1932, the Boat Inn on Peakirk’s Thorney Road was in such an advanced state of disrepair that daylight showed through the thatch and holes in the wall were stuffed with newspapers. Even so, the licensees, William and Sarah Jones, both approaching 70, were reluctant to leave as they had no other source of income and nowhere else to go. The pub duly was closed and its owners, a Spalding brewery, were awarded £450 compensation for their loss of revenue, from which the Jones received £63 and were reduced to renting a single room in the building which they now shared with other tenants. And Peakirk was not unique. It’s merely a case-study since my husband, Greg, has spent the last half century living in and researching the village’s history! ‘For richer for poorer’

During medieval times, primogeniture (inheritance by the eldest son) meant that siblings could descend from the manor house to a peasant’s hovel within a couple of generations, unless they found rich spouses. Moreover, like today, impecuniousness was not necessarily caused by indolence and alcoholism, but by low wages, economic recessions, unemployment, ill-health, the loss of the main wage-earner, many mouths to feed or simply misfortune. Covid-19 also has been a cruel and indiscriminate leveller. The hitherto hard-grafting, comfortably-off have seen their businesses ruined, their lives upturned and been forced to rely on charity to make ends meet. As for the rest of us, it is simply a case of there but for fortune . . .

PS. Workhouses were formally abolished in 1930 though many endured as Public Assistance Institutions with paupers renamed ‘residents’. Peterborough’s former Union Workhouse was demolished 1971 to make way for retirement homes.

James Hetherington Annie Taylor Mornons' History

All so relative by Tony Henthorn

I have never really taken much notice of my own family history but remember being confused as a child as to why I had a Grandad and Grandma Ormerod and a Grandad Taylor – but no Grandad or Grandma Henthorn.

In my later years I discovered that my dad’s father (James Hetherington) was killed in action in Iraq in 1920 before he could marry his betrothed, Alice Henthorn. So, my dad made his entrance into the world six months before dad James was killed and he was given Alice’s Henthorn surname. Five year later, Alice met and married James Ormerod, they didn’t have any children together. I was also fascinated to be told (I cannot remember by whom), that one of my ancestors was Annie Taylor who found fame (but not fortune) by being the first woman to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel – and survive. When we went into the last lockdown, I wanted to find something to help keep me occupied and sane and decided to treat myself to an early Christmas present – a subscription to Ancestry.com and I started plotting my family journey through the generations. Over five months later and I am truly ‘hooked’! I have discovered (to my horror!) that I am not of pure Lancashire stock, my DNA is shared across a number of north west counties, including (dare I say it?) … Yorkshire! The first hundred years, (approx 4 generations) is mainly filled with working-class folk earning their livelihoods in the cotton mills and coal mines, but it’s when I delved a little further back that the discoveries started to become more interesting. It turns out that Ann Henthorn (2nd cousin 6 x removed) ventured to America in 1854 – converted to the beliefs of the Church of the Latter Day Saints (Mormons) through her marriage to James Fielding And then there’s General Ralph Assheton 1605-1650, my 11th Great Grandfather He refused a knighthood that went with his estate in 1632, probably through a rebellion against the Stuart Monarchy. In 1640 he was returned as one of the Knights of the Shire. In the civil war, he took a leading role on the Parliamentary side. Throw in a handful of convicts, war heroes, The Black Knight of Ashton, publicans, train drivers, farmers and politicians and you start to build a picture of who you are and where you have come from – plus, I have learned more about history than I did in all my school years! I am currently working on a new tree for Arthur and Percy – this one tracks their direct (blood) descendants as far back as the 1450s – some 20+ generations. For each entry, I am looking to illustrate it with either a photograph, portrait, depiction of job, map of area etc. It has turned out to be a huge undertaking, but the result (thanks to on-line technology) will be a hard-copy book with details of almost 2,000 direct descendants. I’m sure that when they receive it at Christmas, they will be far more interested in the Paw Patrol toys and books but will hopefully appreciate it in the years to come. As for Annie Taylor? Well, to date I cannot find any evidence of a family link – but I do think I’m on the cusp of discovering an ancestor who was beheaded at the Tower!

A veritable wilderness

Uncovering Peakirk's astP

Archaeology above the Ground

By Greg Prior

Undoubtedly, some of the most picturesque sights in our landscape are our ancient stone churches set in leafy graveyards with their table-tombs, tilting headstones and venerable old yews. As we know well in Peakirk, both church and churchyard can be a haven for wildlife, a magnet for historians and people searching for their ancestors - and a nightmare to maintain.

Lost in the wilderness

Peakirk’s Lost ‘Tombs’

Inspired by St Pega’s Church Wardens’ and their spouses’ heroic efforts in clearing the eastern wall of the churchyard of creeper and suffering withdrawal symptoms from the lack of test-pitting, PAST (Peakirk Archaeological Survey Team) joined forces with Pauline and Barry Cooke to tackle the western section of ‘God’s Acre’, which was an unsightly and perilous wasteland of brambles, ivy and elders. Barry uncovers a lost grave-slab Two generations of Parr memorials

Our objectives were to: 1. Clear the undergrowth and remove overhanging branches so that the memorials can be safely accessed. 2. Improve the aspect of the area. 3. Reveal a previously-hidden part of Peakirk's heritage. 4. Photograph and record the monuments uncovered and, ultimately, compile brief biographies of their owners.

Initially, we set a target of revealing a grave-marker each. But many hands - and Gregg Duggan’s trusty hedge-cutter - made light work. By lunchtime, we had liberated over a dozen ‘lost’ memorials ranging from farmers’ and graziers’ to a Parish Clerk’s.

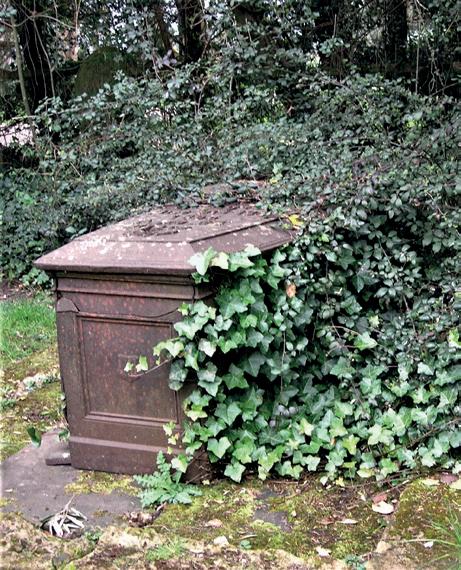

Peakirk Pedigrees

Whilst Avril was beavering away on Robert (1784-1846) and Charlotte (1802-66) Parr’s curious cast-iron ‘tomb’, Barry was rescuing the find of the morning. It was a carved medieval-style grave-slab commemorating Robert’s and Charlotte’s son, Robert jnr, and his wife, Anne, who died at Market Deeping. Further along the row, Pauline unveiled a memorial to Robert’s and Charlotte’s grandsons, yet another Robert and James, the offspring of their daughter, Elizabeth (1814-74) and her husband, Thomas Vergette (1804-87) who farmed on Borough Fen. Meanwhile, Gregg and I tackled the jumble of creepers enveloping headstones belonging to five more of Thomas and Elizabeth’s eleven children, Charlotte, Mary

Two generations of Parr memorials Unusual cast-iron tomb Thomas and Elizabeth Vergette’s grave-slab

Sophia, Anne Elizabeth, Francis and Emily. Although several of them had died elsewhere, they all returned to Peakirk to be buried, together in death as they had been in life. Avril and I returned at the weekend, to strip Thomas and Elizabeth Vergette’s impressive slab of its ivy shroud. Then, beyond their family plot, we turned our attention on the headstones erected for Joseph Eatherley (1807-72), draper and Parish Clerk, his wife, Hannah (1813-76), their sons, Nathan, Daniel, John and Joseph jnr and daughter-in-law, Jane. Next, we progressed to the those of the Kettle family, Joseph (1835-1919), an agricultural labourer, his wife Annie (1842-1922) and their daughter, Sarah Perkins. Annie and Joseph, did not have far to travel for their funerals since their cottage in Chestnut Close backed onto the churchyard. The following Wednesday, Pauline, Avril, Gregg and I met with Sheila Lever and David Hankins. Our agenda was to trim dangerously-low branches, eliminate trip-hazards like ivy runners and dispose of the cuttings from previous sessions to leave the site tidy. In the process, Sheila unearthed a broken headstone dedicated to Bartholomew and Emma Guymer’s baby son, Charles Christian, who died in 1893. And tucked away forgotten in the corner, lies an assemblage of diminutive headstones with the tantalising inscriptions, ‘J. E. 1867’, ‘D. E. 1871’, ‘J. E. 1871’ and ‘J. E. 1872’. More infant burials? Perhaps not. For Avril surmises that they were temporary grave-markers for Joseph Eatherley jnr (1837-67), his brother, Daniel (1853-71), sister-in-law, Jane (1844-71), and father, Joseph snr (died 1872), until they could be replaced with more-elaborate memorials. Afterwards, they were re-used as 'footstones' (and trip hazards). To Whose Benefit?

We will be leaving enough undergrowth along the western boundary with The Old Rectory to satisfy the even most ardent of eco-warriors. We also plan to create several habitat piles, though the only evidence of fauna that we detected during our activities was the distinct and pungent aroma of a patrolling tom-cat. And, of course, unlike our previous exploits in archaeology, we are able to leave the fruits of our labours uncovered for all to see. There will be no need for explanatory labels for each monument tells its own story.