7 minute read

Heritage

from Village Tribune 138

Fair Trade in Medieval Tribland

By Dr Avril Lumley Prior

Advertisement

Speed’s Map of Peterborough (1612). ‘H’ marks the market place. Helpston Butter Cross

Nowadays, fun fairs, antiques fairs, collectors’ fairs, craft fairs, steam fairs, stamp fairs, village fayres, church fetes, etc. are all associated with the pursuit of pleasure, pastimes or the prospect of procuring a bargain.

Conversely, in medieval times, fairs had a much more serious function. Yet, like their latter-day counterparts, they were set up for the exchange of goods or services for profit as well as providing a few light-hearted distractions. Exchange and Mart People have probably been bartering with one another since time began. However else could a Neolithic flint axe from the Thetford area find its way to the Alps? It is also highly likely that the Iron-Age ringwork or lowland fort, bisected by Decoy Road north of Milking Nook near Newborough, became a trading post during the periodic gatherings of tribes for ritual feasting. And we know that the Romans had been trading with Britain long before the invasion of 43AD. Domesday Book reveals that 60 markets were operating in 1086, including Leighton Buzzard [Bedfordshire] and Warsop [Nottinghamshire]. Permission to hold them could only be given by the king to the lord of the manor and upon payment of a hefty fee. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle would have us believe that ‘King Eadgar’s’ charter to Peterborough Abbey of 972, granted a market ‘in the same town’ and hints of others at Stamford and Huntingdon. Unfortunately, ‘Eadgar’s’ charter is an early-twelfth-century forgery. The first hard evidence of a market in Peterborough is not until 1146, when Abbot Martin de Bec realigned the continued overleaf >> villagetribune 39

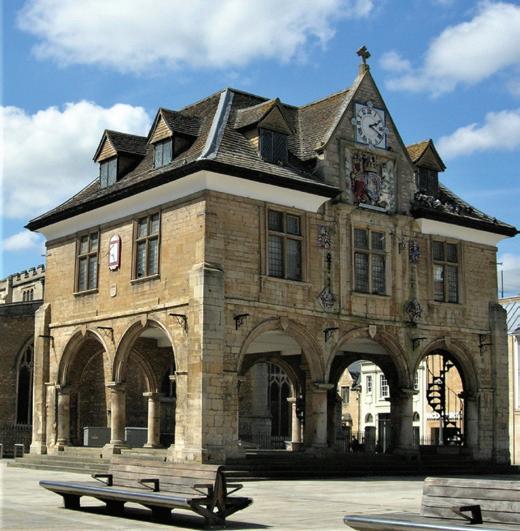

HERITAGE | FAIR TRADE IN MEDIEVAL TRIBLAND town and repositioned the old marketstead from the east side of the monastic precincts to the present Cathedral Square. By the 1300s, locally produced combed wool, fleeces, skins (for leather and parchment) and meat were among the goods on sale together with live sheep and cattle and geese reared on Borough Fen. The market ceased trading during the visitation of the Black Death in 1348/9 but was soon revived, with the abbot raking in the revenue from the rentals of booths and tolls on goods entering the town from all directions, including across the town bridge (constructed in 1308). Toll-dodgers were heavily fined and/or had their goods confiscated. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, in 1539, the market fell under the control of the Dean and Chapter of Peterborough Cathedral who continued to harvest the profits in the same old style. By then, many of the stall-holders or stallengers had moved into shops with living quarters above, near their old pitches and again leased from the Dean and Chapter. The purveyors of meat were to the west of St John’s church in Butchers’ Row; hides and fleeces were traded in Cumbergate [lost to Queensgate shopping mall] and the cattle market was in Long Causeway. Butter was sold beneath an arcaded hall, replaced in 1686 by the present Guildhall, which was still referred to as ‘the Butter Cross’ as late as 1927! Butter Cross, Chichester Peterborough Guildhall (formerly the ‘Butter Cross’)

Out in the countryside, the products on offer were not dissimilar to those found at a present-day farmers’ market. The Farmers’ Cross (of which only fragments survive) on Castor village green, Bainton Butter Cross (another shadow of its former glory) and its counterpart at Helpston, would have made attractive unofficial ‘pop-up’ venues with merchandise laid out on their steps. According to oral tradition, Helpston’s structure was enclosed by a timber penthouse or shelter until c.1850, adding weight to the theory that goods were traded here centuries ago. Conversely, there is no documentary evidence relating to trading at Castor, Helpston or Bainton. Indeed, there are only two references to chartered markets in the whole of Tribland, whilst a further two were established at Northam and Oxney (both near Eye). In 1264, Henry III allowed Ralph Camoys of Torpel to hold a Thursday market and an annual three-day St Giles’ Fair (temporary market) from 31 August until 2 September. It is generally understood that both market and fair took place on the manorial site, now known as Torpel Field, next to the old Roman thoroughfare, King Street. Unfortunately, Ralph’s grandson, John Camoys, went bankrupt in 1281 and his assets were seized by Edward I. Upon the king’s death, Torpel manor passed to his son, Edward II (130727), who bestowed it upon his companion, Piers Gaveston. It is unlikely that the market and fair lasted beyond 1309, when Gaveston exchanged Torpel and Upton for land in Cornwall and it would certainly have disappeared when the plague struck, in 1348/9, after which the settlement was abandoned. Our second Tribland citation of a market is in 1294, when Godfrey de la Mare of Northborough procured a charter to hold a Wednesday market and an annual three-day fair commencing 14 August, from Edward I, who was perpetually short of money due to his military campaigns. Both were so successful that they

drew trade away from the town of Peterborough and incurred the wrath of Abbot Geoffrey de Crowland (1299-1321). Ultimately, he persuaded his de la Mare namesake to surrender his royal charter on pain of Eternal Damnation, a fate worse than death which terrified many Christians until well into the twentieth century. All the Fun of the Fair Fairs or marts attracted bone-fide traders and hawkers from a much wider area, including overseas. A fusion of a Christmas market, an agricultural show and the tented village at Burghley Horse Trials, they were usually held on the feast day of the saint consecrated at the local parish church. In order to raise funds for his disastrous Crusades to the Holyland in 1189, Richard the Lionheart granted a charter to Abbot Benedict of Peterborough for the annual St Peter’s or Petermas Fair in the abbey precincts, commencing immediately after Mass on 29 June. Henry III (1216-72), sanctioned St Oswald’s Fair, lasting eight days from the second Sunday in Lent, in honour of the seventh-century Northumbrian king whose undecayed right arm was a lucrative Peterborough pilgrim attraction. Whilst the Bridge Fair, privileged by Henry VI in 1439, stretched from the present Bridge Street across the Nene into Huntingdonshire and was held from 21-23 September. Fairs proved such a welcome relief from the dreary daily grind for the local peasantry that The remains of Castor’s Farmers’ Cross Bainton Butter Cross

many were tempted to sneak away from working on the lord’s demesne in order to attend. For those who went AWOL, the punishment was dire; they were hauled back to the fields by the bailiff and banned from returning for the fair’s duration. There were no fortune tellers, ‘freak shows’ or exotic animals until Tudor times and fairground rides did not arrive until improvements to the steam engine in the nineteenthcentury. Neither were there hoopla stalls, coconut shies nor rifle ranges, where you could win a cuddly toy, a tawdry ornament nicknamed a ‘fairing’ or, until recently, a goldfish in a plastic bag. Instead, medieval punters were entertained by contests of strength and prowess, especially wrestling and archery (in preparation for the next war). Goods were on sale that usually could not be purchased at a weekly market. They included spices, textiles, pottery, weapons, tools and, inevitably, ‘cheapjack’ or tat for the poor. Troublesome teeth could be extracted, quack doctors consulted, panaceas and love potions purchased, money lost to tricksters and letters and wills written by scribes for members of the largely illiterate public. Refreshments were dispensed from fast-food stalls with pies selling like hot cakes. (In those days, the often-inedible pastry served as a throw-away wrapper.) And there was neither tea and coffee nor burgers for they were yet to arrive on our shores. But ale and mead were plentiful as were drunkenness and anti-social behaviour! A Sad Farewell Alas! All of our Tribland markets and fairs vanished centuries ago. Moreover, in spring, after nearly 900 years of trading, Peterborough’s market was lost to a housing development and has been reduced to a handful of stalls on Bridge Street. Only the Bridge Fair prevails. The fairground has moved to Peterborough Embankment and is now run by John Thurston & Son, with side shows and stalls selling sweets and candy-floss. This September, it boasted hair-raising rides such as the Extreme Orbiter, Freak Out and Jumping Frog along with old favourites like the Ghost Train and the Dodgems. A far cry from the medieval trade fairs but a still a whole lot of fun!