primary data.

Stakeholder Profile Analysis and Interaction Map:

Stakeholder mapping became a crucial tool in visually collating and comprehending the relationships, power dynamics and influence of different actors in and around Casarão. It also falls within our thick mapping methodology in our primary research as in superimposing a stakeholder map with the findings of our thick mapping, we can begin to understand how social intersections multiply and how this may contribute to the narrative of (de)marginalisation. For example, beneficiaries may have a different and potentially hostile relationship with the state, whereas Casarão primarily relies on municipality income since it’s inception. In conducting interviews and collating the information with this tool, we can highlight the push and pull factors related to marginalisation of trans refugees/migrants in São Paulo. Stakeholder mapping also reveals how knowledge is distributed within a network of people and organisations which helps in evaluating the interventions that Casarão offers.

In addition to mapping stakeholders, we also wanted to highlight more information on the people we are interviewing as a means to understand the intersections in their identities better. Demographic profile analysis is often based on personal information such as age, ethnicity, gender, economy and education of the interviewees. In the study of Casarão, personal information was collected from the interviewees in order to better characterise the group of “transgender migrants”, to understand the dilemmas they face in migration, and how pivotal Casarão is in changing these dilemmas.

social media

casarão staff

corporate funder

corporate partner

casarão beneficiaries

dutch government

casarão volunteers

celebrity representative

casarão leadership individual donations

são paulo mayor

company

são paulo representative hospitals

são paulo residents

private sphere (companies) private sphere (NGO)

key: state actors citizen sphere

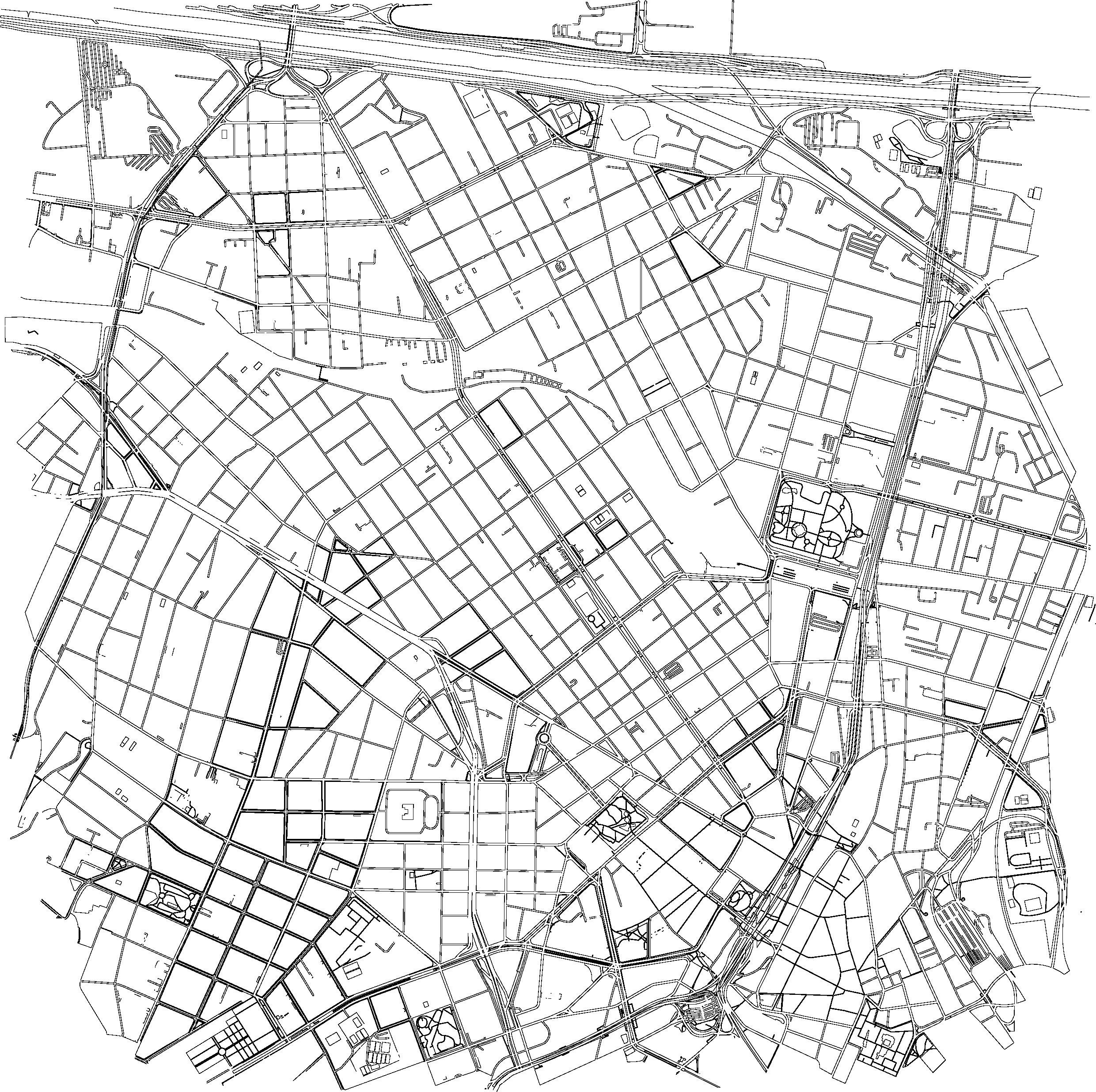

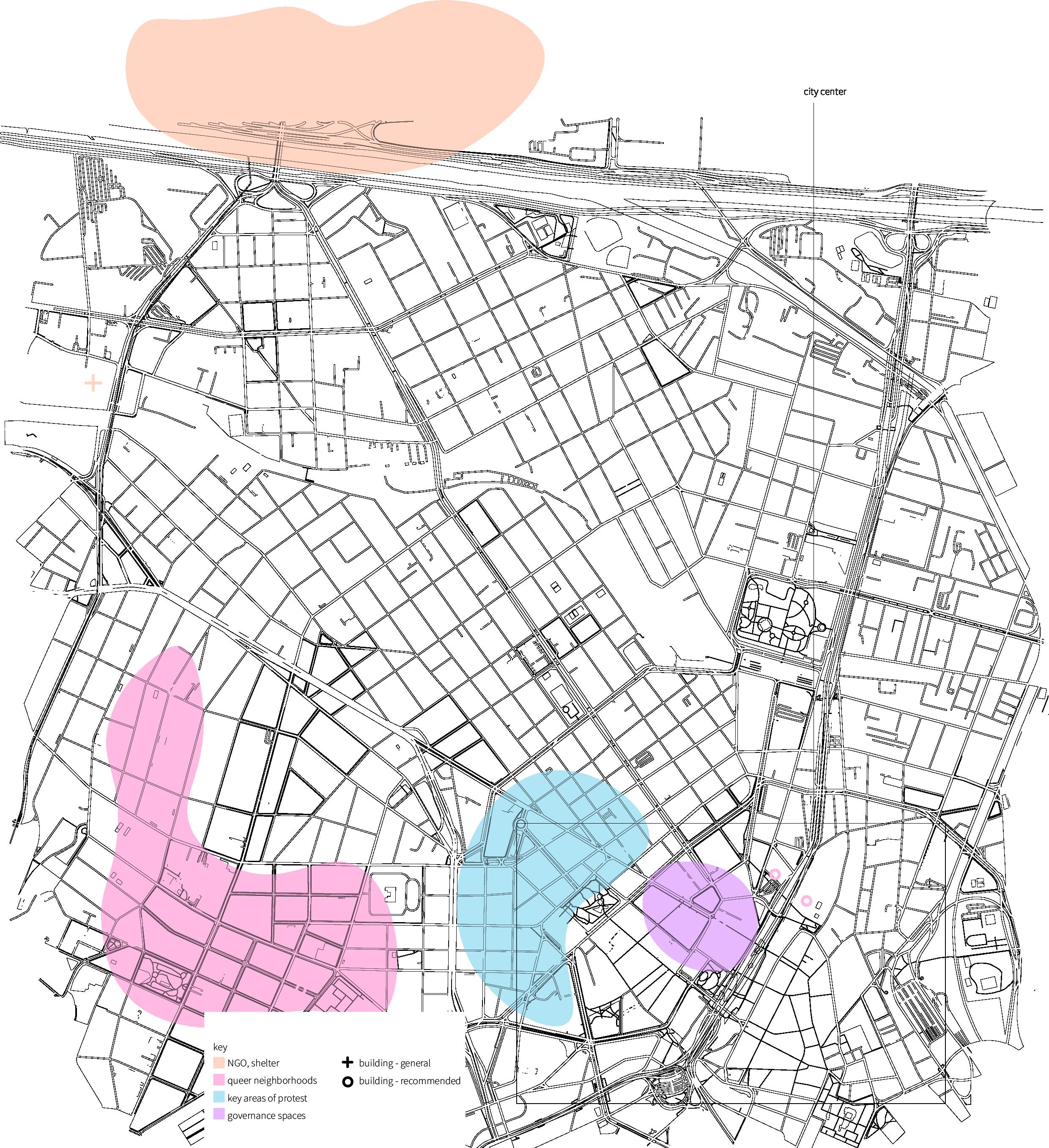

Thick Mapping - Primary:

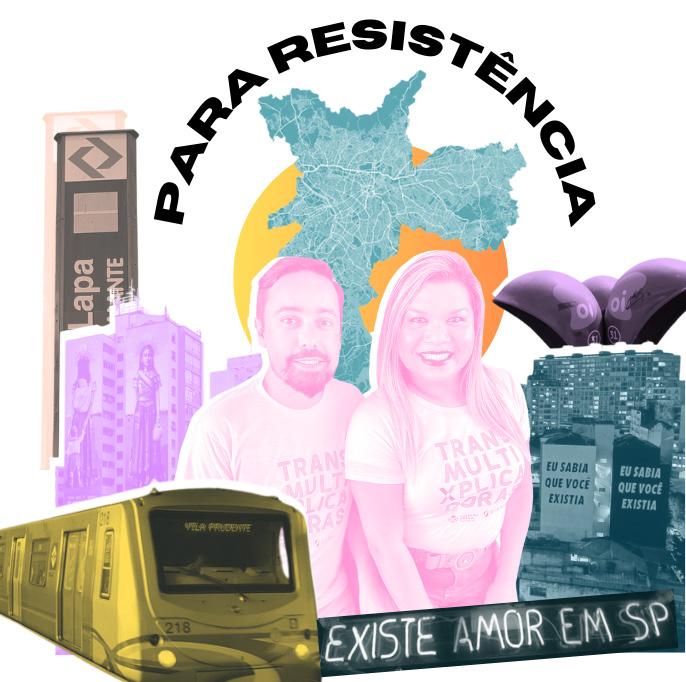

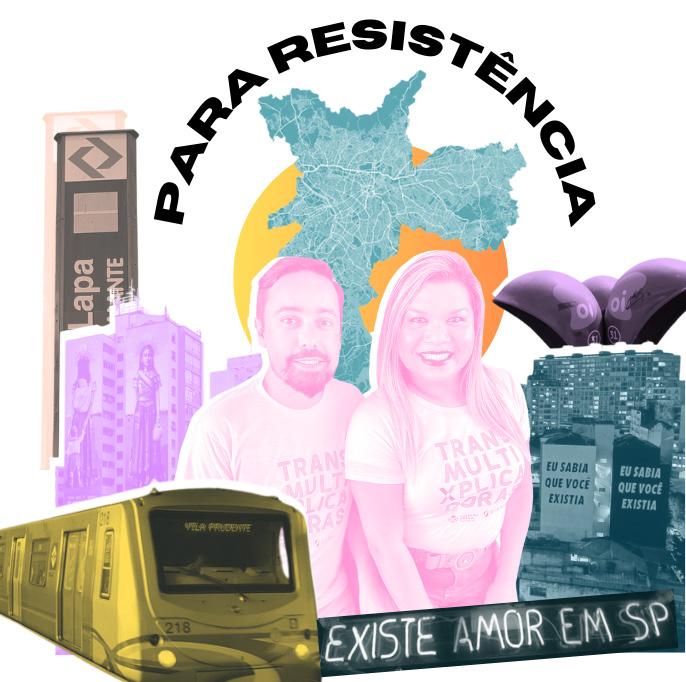

Thick mapping as a method to study marginalisation gives us an insight into the ways in which humans occupy and navigate space. In essence, it is a way of understanding the social conditions of spaces and the interactions that are sparked in varied conditions through heavy detailing and description (Kling and Roidis, 2021). In order to create a thick map that helps us to understand how transgender people occupy and appropriate spaces, we first set out to gather spaces from the people we interviewed as well as spaces available from city maps. By compiling this information and seeing support and legal spaces overlapped with recreational and informal spaces we can understand the ways in which people fill their need gaps in the city to resist marginalisation and invisibilization.

Rogério. Director of the organization. Spoke to the logistics and work of the organisation as well as the intricasies of different programmes.

Semi-structured interviews refer to a type of informal interview in which a rough outline of the interview is drawn up prior to the interview. The interviewer has the flexibility to adapt the follow-up questions through the interview, and there are no explicit requirements on how, when, or where the interview should be recorded (Aramberri, 2009). This type of interview can be better attuned to the mood of the interviewees and understand their true feelings by deconstructing their social and cultural backgrounds. In Casarão, semi-structured interviews with leaders, staff and beneficiaries were used to investigate their feelings of participation in the organisation and the possible future direction of Casarão. We asked questions that would prompt interviewees to give their perspectives as well as a chance to speak into existence their wishes for the programmes and future of the organisation. By doing this we learned both about the gaps within the organisation but also how Casarao has filled societal gaps.

Mikaella. Director’s assistant.

Also takes leadership in income generation and partnership management. Comes from a background in healthcare and works to mainstream trans rights into public healthcare services.

Patricia. Administrative Assistant of Casarão who has herself completed the transcitizenship programme. She is usually the first point of interaction for those external to Casarão, whether it be potential beneficiary or otherwise.

Psychologist

Co-shares responsibility of running mental healthcare provisions (namely clinical consultations) within the organisation and being the intermediary for external organisation. Takes on responsibilities involving meeting people to better understand their mental health needs.

Isabel.

English Teacher.

Leads on the pedagogy strategy of the organisation, especially in regards to language learning. Teaches languages as a skill to mainstream literacy integration both within Brazil and internationally.

Ricardo. Resident Social Worker

Psychologist

Co-shares responsibility of running mental healthcare provisions (namely clinical consultations) within the organisation and being the intermediary for external organisation. Takes on responsibilities involving meeting people to better understand their mental health needs.

Beneficiary*

They participate in Casarão’s programme and arrived with the non-binary beneficiary.

Beneficiary* Moroccan non-binary refugee beneficiary of the organisation.

Mainly deals with the needs of beneficiaries in regards to social security and welfare.

*To maintain anonymity, photos for beneficiaries are filled by photos from the organization website, rather than the people we discussed with

Beneficiary*

Tunisian trans man who has sook refuge in Brazil with the help of Casarão

Spatial ethnography:

Spatial ethnography encompasses a multidisciplinary approach that integrates geography, sociology, anthropology, and public health to comprehend the spatial patterns, social dynamics, and health issues within the city. The racialisation of migrants and the articulation of race and class hierarchies in São Paulo have been examined through spatial ethnographic studies (Ikemura, 2021) which was the impetus in incorporating this concept within our conceptual framework. These studies shed light on how social and spatial mobilities intersect with identity constructions in urban settings. A key contributor in terms of the concept application into our research is Radical Housing Journal’s ‘Permanent transitoriness and housing policies: Inside São Paulo’s low-income private rental market’ long read (Villela de Miranda, Rolnik, Santos, Lins, 2019) as it explores transitoriness (a recurrent theme and condition within our thematic area) within the greater concept of spatial ethnography in São Paulo. This concept was the precursor (and cornerstone of our rationale) of our curation of our primary data collection methodology as spatial ethnography marries different disciplines with the goal of ‘thickening’ via both the y and x-axis of exploration and visualisation of intersections. Superimposing information in the same manner as this form of scholarship allows us to synthesise and grasp the connection between the digital and physical within Casarão’s practice.

Right to the city:

Right to the city was proposed by Henri Lefebvre (Lefebvre, 1968) and advocates that urban environments should be inclusive and participatory and accessible to all residents. This framework expresses the diversity of social justice, urban life and citizenship. The integration of this framework into our research allows us to contextualise Casarão’s practice in terms of their ability to negotiate and navigate the urban landscape on behalf and alongside their beneficiaries as a means to fortify their resilience and advocate for the community’s de-marginalisation. Right to the city offers an evaluative praxis that can synthesise Casarão’s participatory practices as well as ascertaining how São Paulo the city, a complex and intricate web of elusive socio-political powers, contributes to the (de)marginalisation of trans migrants and refugees.

Man giving directions to stranger while tourists guide themselves. The open Avenida Paulista, showing a reclaimation of public space for pedestrian use. A warm meeting at Casarão when people could meet in person again after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 14.

Figure 15.

Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Figure 16.

Figure 14.

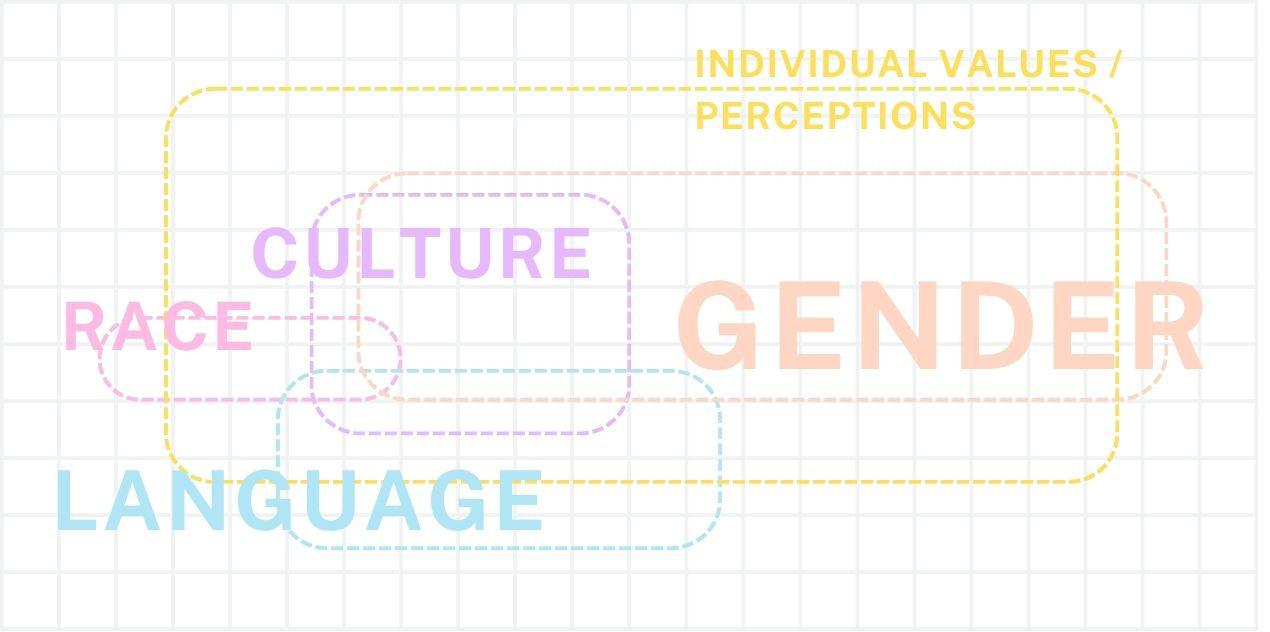

Feminist intersectional lens:

Utilising a feminist intersectional lens is absolutely paramount in our conceptual framework as it provides a roadmap, guide and evaluative reference points that can guide our research as well as providing a logical foundation. In putting a lens that focuses on the dichotomy of oppression and power in order to comprehend the multiplicity of individual lived experiences (Collins et al., 2021: 690) we are able to put different forms of ‘reality’ in discussion with each other in order to communicate an accurate representation of the context analysed in this study. An example of this would be the discourse on womanhood centring around ‘who is a woman’ or even/rather ‘who is allowed to be a woman’. In exploring the providence of logic surrounding political arguments, epistemological/ontological analysis can be threaded throughout our research. It will not only facilitate the bridge between theory and practice within feminist scholarship but also offer another layer of nuanced critique in other parts of our conceptual framework. When we are understanding who has the right to the city (or who has the right to use land as a pedagogy) we need to understand what makes the city accessible for some people and dangerous/inaccessible for others. In studying Casarão’s modus operandi, we used a feminist intersectional lens to study the plight of transgender immigrants in Brazil, especially in regards to the support received by various actors, access to healthcare and the wider politics of acceptance/tolerance.

Land as pedagogy:

Land as pedagogy is a concept developed by Simpson (2014) that emphasises the importance of land education in the context of indigenous knowledge and culture. This concept is often associated with learning through contact with the land, and often incorporates traditional local stories, practices and cultures. Land as pedagogy tends to encompass relational learning, traditional stories, indigenous sovereignty and rejuvenation, and resistance to colonial systems. This approach is beneficial in fostering deeper connections between individuals and the environment, promoting community sustainability and well-being. Within this context, we instrumentalise this concept to characterise the relationship between the beneficiaries and the urban environment they inhabit in a way that is cognizant of epistemological/ontological providence of their realities. This means that the politics of memory, decolonisation and integration are woven into our methodology approach (both for primary and secondary data collection) in order to fully capture the breadth and complexity of transgender migrant rights in São Paulo, Brazil.

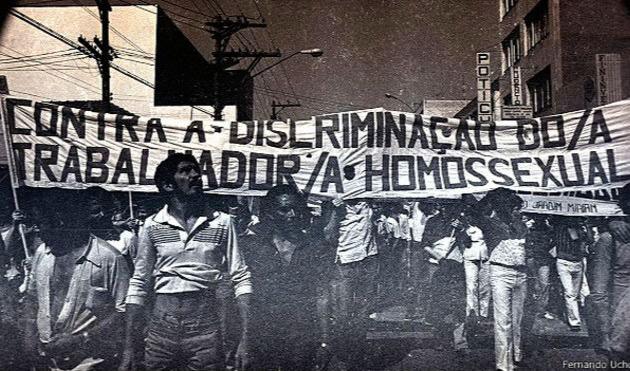

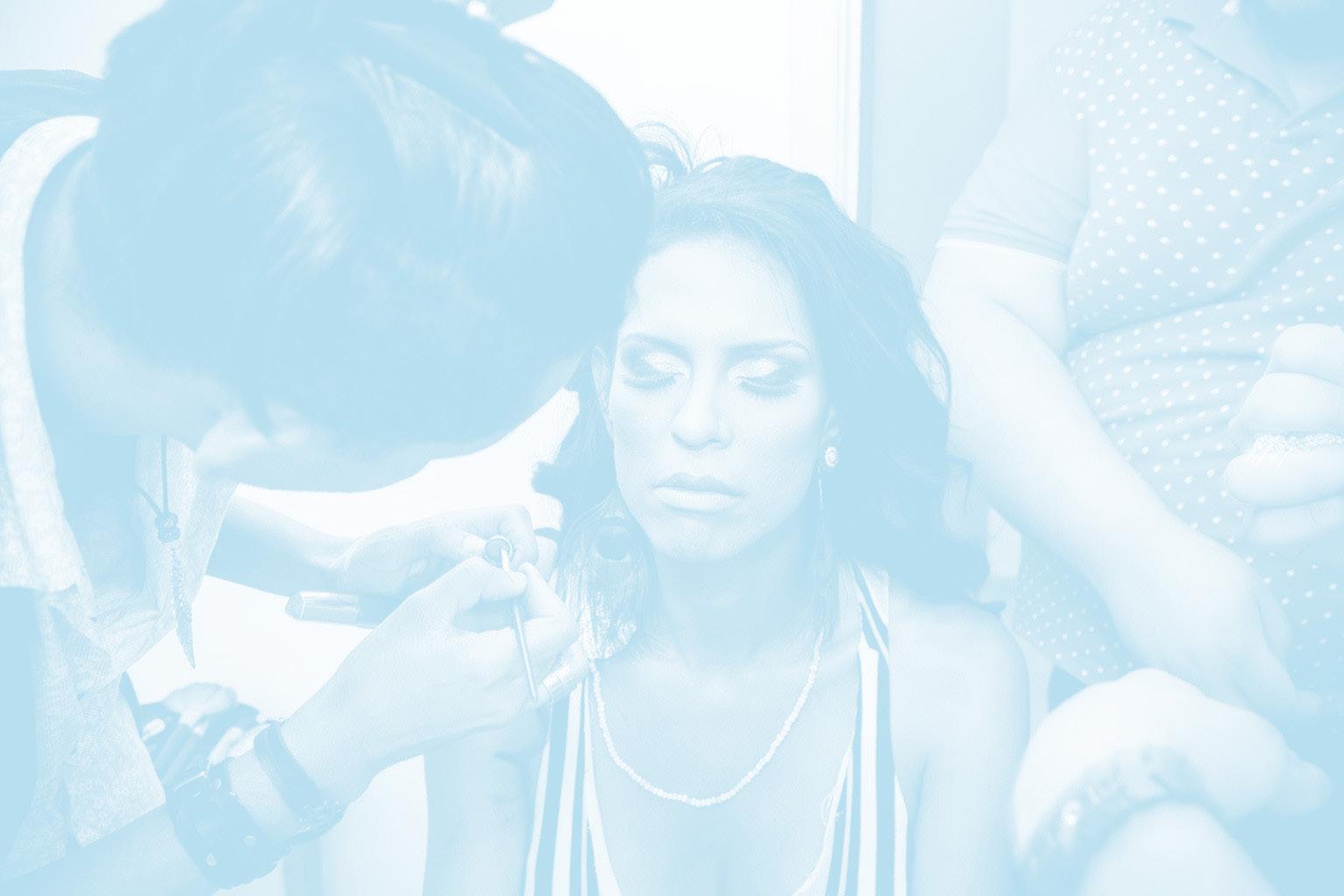

Theory of Change: Visibility, Empowerment and Intersectionality

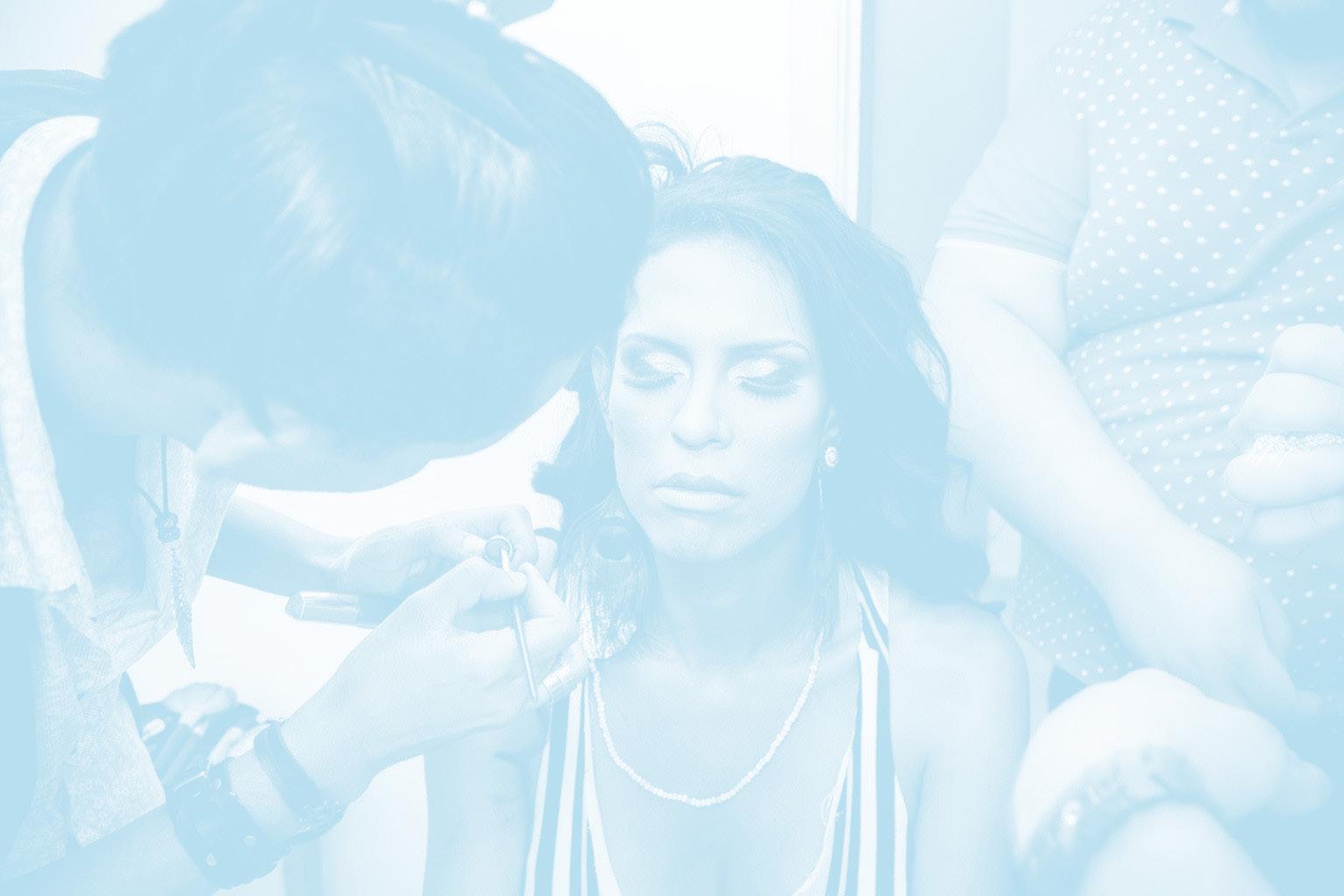

The binary of inclusion and exclusion can be articulated in terms of visibility which is the prism from which Casarão operates from. Mainstreaming efforts are synonymous with visibility in Casarão’s practice as societal integration, namely through facilitating the transition from the informal to the formal economy as the primary means to curtailing marginalisation and empowering the trans migrant/ refugee community in São Paulo. The graph above provides the visual narrative to this notion with the x axis denoting vulnerability and support pathways marked along the y-axis. In the skill/capacity building stage, Casarão have purposefully chosen transferable skills that create linkages and avenues to the formal markets from informal labour such as sex work or street vending. This theory of change has been corroborated by trans members of staff in Casarão who themselves have undergone the transcidadania municipal programme who then feed in their lived experiences into project planning of the organisation. Mikaela, the director’s assistant, is one of these women who helped shape the rationale of these projects. In her interview, she states that cosmetic skills such as make-up and wig-making are forms of currency within the world of sex work for trans women (Cai et al, 2024b). Casarão has identified skill sets that can feasibly and rapidly be utilised in creating the necessary conditions for social inclusion.

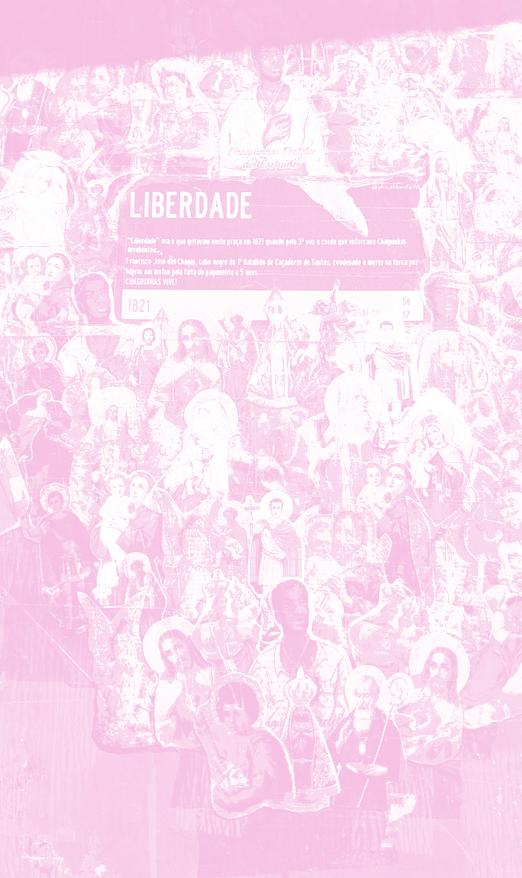

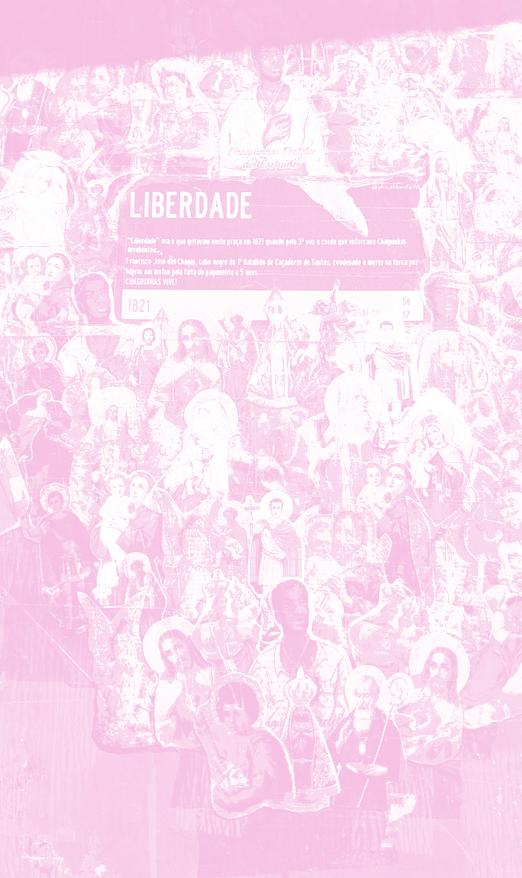

Liberdade (liberty) - was what was screamed in this square in 1821 when for the 3rd time rope wrapped around Chaguinhas broke.

Francisco José das Chagas, black corporal of the first battalion of caçadores de santos, condemned to death on the gallows for leading a mutiny for the 5 years of lack of wage payments

Figure 18.

Centro de Cidadania

LGBTI Cláudia Wonder (LGBTI citizenship centre)

Centro de Acolhida

Especial Casarão Brasil (trans women shelter centre)

Prefeitura de São Paulo (São Paulo Municipal Government)*

Sistema Único de Saúde (Brazilian Universal healthcare system)

2024 partnerships with Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Acor Hotel Group and Mercury Hotels

2023 partnerships with the Dutch Government, docusign and shopping point

* namely the human rights and citizenship office, the office of social development and assistance, the health department and the city’s working group on HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment

Space

Digital and physical space (be it internal or external) coalesce in a manner which speaks to the organisational infrastructure built by Casarão in the pursuit of de-marginalising transgender refugees and migrants. The table below shows exactly where those intersections are situated with four key focal points to highlight the nature of this intricate web. The Cláudia Wonder centre is featured heavily on Casarão’s Instagram due to the fact that it is the location where the majority of the organisation’s activity takes place. Instagram acts as a digital space that attracts funders and other engagers while providing a record of their achievements, all of which are vital to the sustainability of their programmes. CAE (Centro de Acolhida Especial) occupies a unique space on Casarão’s YouTube as through the ‘vidas migrantes’ documentary, women who use their shelter were able to tell their own stories in their own words. In terms of external spatial occupation, Casarão’s branding is massively linked with the São Paulo Municipality and short-term sponsors such as the Dutch Government in order to bring a sense of added legitimacy to the organisation’s mainstreaming efforts in the city. In marrying the physical to the digital, Casarão are able to extend their reach both nationally and internationally.

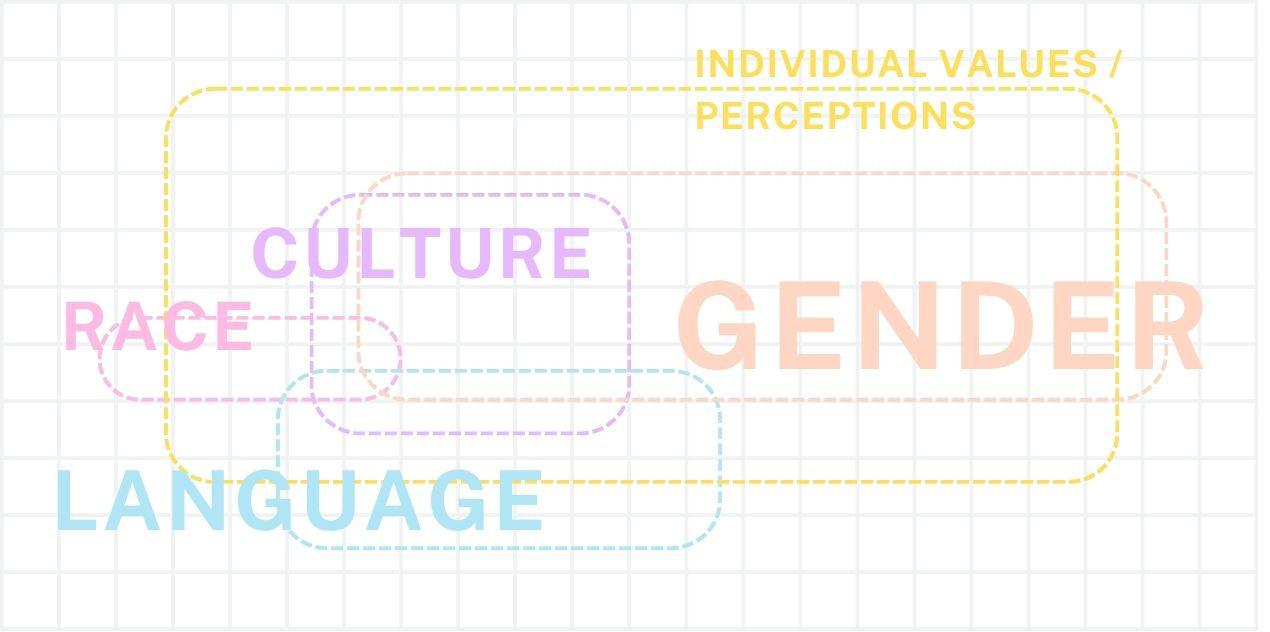

Intersectionality

Projects such as receptionist training, wig making and baking classes also speak to the intersections of identity markers which was a recurrent theme in our interviews. The narrative of discrimination picked up by Casarão and our data collection indicates the compounded nature of race, culture, gender and language (to name a few characteristics) is the catalyst of marginalisation but it can also be instrumentalised by actors like Casarão to curtail said subjugation. The three North African beneficiaries that we met both noted that the language difference has been an ongoing barrier in terms of integration; however, the other languages that they speak (namely Arabic, English and French) were crucial in obtaining their current jobs in the hospitality industry (which was facilitated by Casarão) (Cai et al, 2024b).

Inclusion = Resistance: De-marginalisation inevitably is a story of resistance and social protection. Casarão becomes the organisational hub for this as it posits itself as a buffer between different corners of public life in order to limit exposure to further forms of structural violence for its beneficiaries. On site nurses, psychologists and social workers help migrant/ refugee beneficiaries navigate the complexities of trans life in São Paulo on their behalf or in collaboration. This is further supplemented by their partnership strategy in income generation as creating far-reaching rapports can be leveraged in terms of funding programmes or creating employment opportunities for the beneficiaries.

Needs:

More representation: Their visibility and representation needs to be increased to gain more support for their work and community needs.

More resources for workshops: Improve and increase workshop resources, especially for transgender immigrant and refugee women.

Dedicated shelters for trans refugees and migrants: Establish dedicated centers or shelters to provide safe spaces for transgender immigrants and refugees.

More research on healthcare: Advance medical research to ensure the transgender community has access to appropriate health care.

Political assurance:

Work with political leaders to ensure the sustainability of transgender civil rights programs and protect the legal and social rights of community members.

Barriers

Key barriers that also need to be addressed in conjunction with pursuing the above needs are the need for further representation within the organisation, generating research output and governmental relations at different echelons. Casarão already has initiatives in motion surrounding these three areas whether it be hiring transcidadania programme graduates, interacting with academic institutions like UCL or lobbying like-minded politicians in the upcoming municipal elections. This also shapes future planning as the natural progression from the organisation’s standpoint would be to:

- Continuously provide education, job training and employment opportunities as a long-term strategy for the communities to improve their socio-economic status.

- Curate education programmes for new generations.

- Broaden the project to more cities and nations.

- Specific shelters for trans migrants/refugees with dedicated task forces for the subgroups under that umbrella.

- Build more capacity/engagement in the community.

An image of Claudia Wonder, still legible but fragemented to communicate that there are organisational needs. Figure 19.

dipal mistry

This fieldwork has taught me how to question what I think I know, how I know it and be prepared to be confronted with unexpected knowledge. I think it was important to learn about how Casarao’s work went beyond the screen and manifested locally with the support of social media, and how the hard work and solidarity of the staff of the organisation was a hidden component of support and visibility to make the project possible.

This research project as a whole has reaffirmed my belief in the interconnectivity and transnational nature of marginalisation. While our project was focused on a specific context, innumerous parallels can be drawn in terms of reflecting on my own background and the environment I come from. Reflecting on positionality is crucial in qualitative research in order to reflect on epistemological/ ontological providence of knowledge whether it be external or internal and this definitely came to the forefront during the interviews that we conducted.

I think fieldwork about data collection, an opportunity to into a community stand its culture, ture and lifestyle. cess, I need to build community members can better understand feelings and experiences interviewees. The field trip also more direct understanding the experiences es faced by LGBTI different countries, more representation litical guarantees, trans-citizenship to help them get not just physical

sumayyah mohammoud

deyu cai

is not only collection, but also to go deeper community and underculture, social struclifestyle. In this probuild trust with members so that I understand the real experiences of the also gave me a understanding of and challengLGBTI groups in countries, who need representation and poguarantees, such as the trans-citizenship programme, get basic power, physical help.

ruobei liang

It was an interesting experience, I met people from different countries with different experiences, I heard different voices and it made me think more.The OPE in Brazil provided profound insights into the struggles of the LGBT community, particularly transgender individuals, highlighting their experiences of discrimination and violence in the developing world.This experience prompted a deep reflection on the urgency of advocating for LGBT rights globally, including in China, where societal attitudes are evolving amidst government conservatism. The comparison between Brazil’s contradictory environment and China’s changing social landscape emphasised the role of governmental policies in shaping societal acceptance.

Fieldwork is the process of stepping out of your comfort zone. As someone from a small city in a developing country, each survey was an enrichment of my experience, both in the process and in the preparation and wrap-up of the survey. Seeing something in person is more valuable and surprising than in text. It was great to meet everyone on the trip, especially the beautiful women of Casarão and the rest of the staff! Thanks also to my perfect colleagues!

The research journey we have taken you on via this pamphlet captures the intricate and multidimensional landscape of transgender migrant and refugee experiences in São Paulo, Brazil. This was done through magnifying Casarão’s efforts in combating marginalisation through their specific brand of social inclusion and mainstreaming. In spite and because of Brazil’s grim reality for LGBTQIA+ individuals (namely right-wing evangelical conservatism, trans murder rate, limited federal and state support in comparison to the municipal level in São Paulo etc..) Casarão offers a needed juxtaposition and a narrative of resilience that can be translatable in other contexts that face similar levels of hostility.

Through a multifaceted approach combining secondary data analysis, semi-structured interviews, critical multimedia content analysis, a nuanced conceptual framework that nods at spatial ethnography amongst other relevant scholarships, we unravelled the nuanced layers of marginalisation and resilience within the transgender migrant community and made sense of it via thick mapping and critical intersectional/feminist analysis. Our findings underscored the pivotal role of visibility, empowerment, and intersectionality in Casarão’s theory of change, where mainstreaming efforts and skill-building initiatives serve as pathways to inclusion and economic independence.

Furthermore, our exploration of the nexus of Casarão’s digital and physical spaces illuminated the association’s ability and desire to evermore extend their reach, provide pastoral/legal/social support, and nurture vital income generating partnerships in the perennial goal against structural violence and fostering empowerment via social protection and solidarity.

Key barriers have also been identified by Casarão members both staff and beneficiary alike, which have been incorporated into this pamphlet. It is clear that Casarão’s future trajectory is cognizant of the challenges of today and tomorrow which is completely due to the diligent work Rogério (CEO) and his team do tirelessly, day in and day out. Casarão have shown great commitment to education, job training, and broadening its reach to more cities and countries, with a focus on specific shelters and community engagement for various substrata within the trans migrant/ refugee community which has been nurtured since their inception as an organisation. Casarão’s desire and motivation to further disaggregate social markers with the goal of bettering their intersectional practice is an important takeaway in terms of furthering the discussion of development practice within the planning/administration sphere in a global sense.

People doing eachother’s makeup at a class even at Casarão.

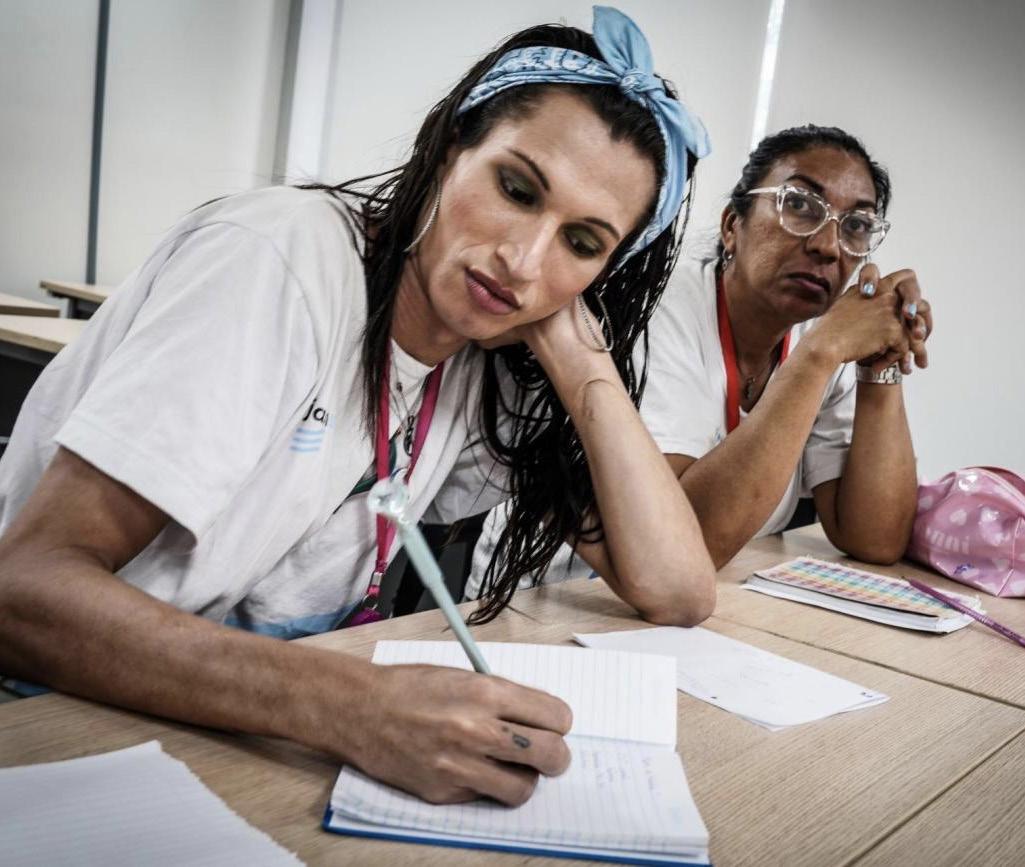

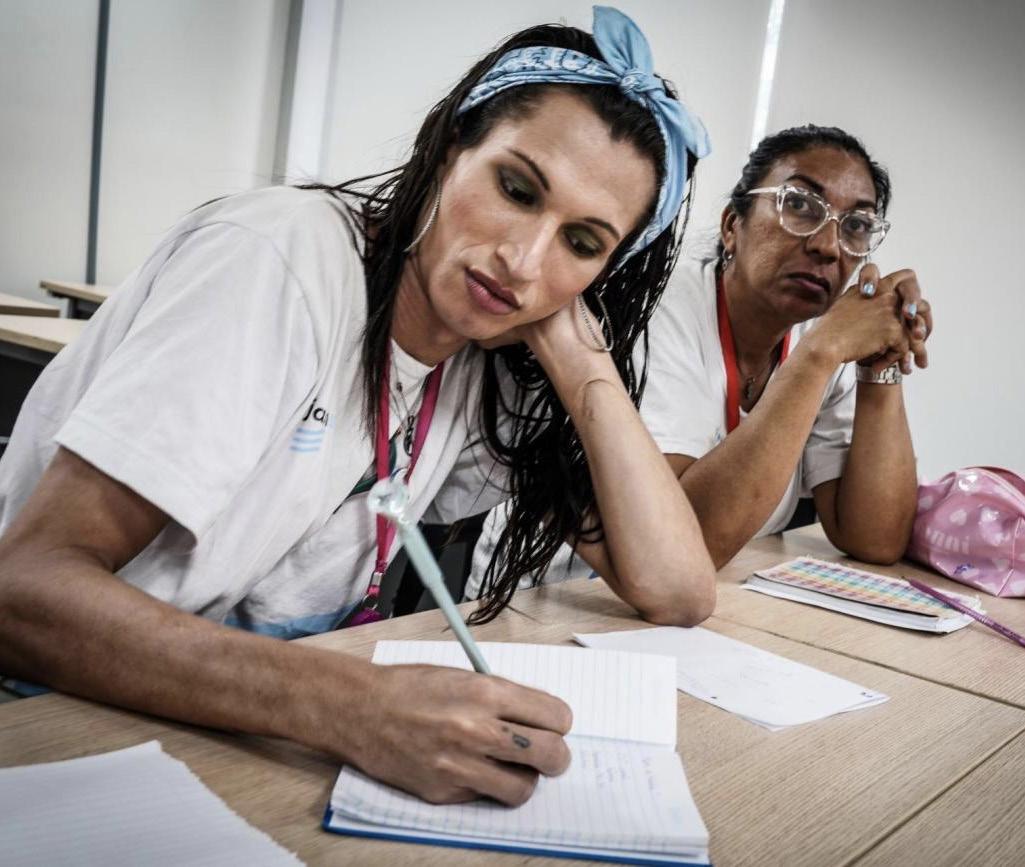

People studying during a learning event at the Casarão education center.

Women competing at fashion show.

Figure 20.

Figure 21.

Figure 22.

Figure 20.

Figure 21.

Figure 22.

The malleability and flexibility of Casarão’s modus operandi means that their theory of change can evolve and mature thus giving further credibility to their logic in reducing marginalisation. In observing the ever-increasing number of trans women working for Casarão, the growing use of participatory practices (in evaluating and constructing programmes) will facilitate further validation of Casarão’s theory of change as well as informing what development practice should look like within this context and perhaps elsewhere.

However, our research is limited as we do not have a comprehensive insight of the entire trans migrant and refugee community in São Paulo outside of Casarão nor did our study have the necessary duration to fully tease out all possibilities stemming from our research question. While there are many aspects of our findings and of Casarão’s practice that are translatable, a global review would be needed within this thematic area in order to create the necessary linkages to facilitate this.

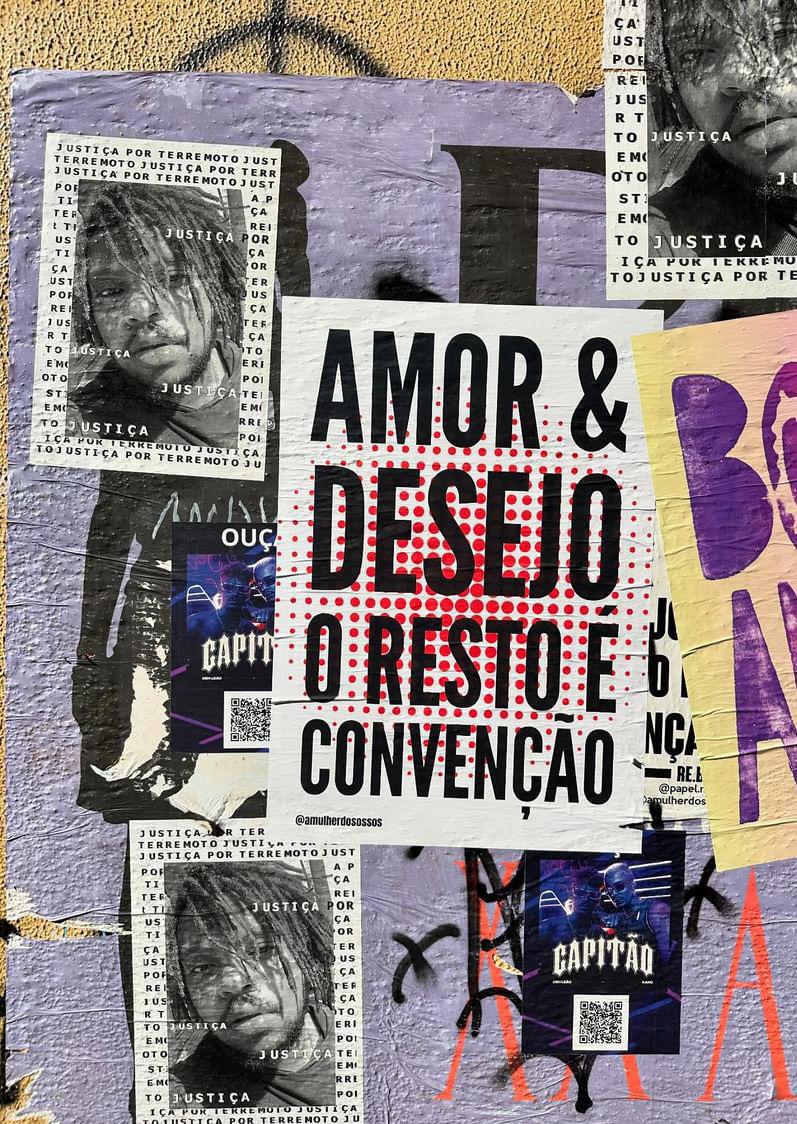

To conclude, our study not only highlights the tribulations faced by transgender migrants and refugees but also celebrates and immortalises the narratives of resilience stemming from trans individuals themselves and the organisations dedicated to uplifting them. In learning about how Casarão has created spaces of empowerment, support and belonging within the complicated and vibrant urban landscape that is São Paulo, it is beyond paramount for us all to amplify their voices, dismantle systemic barriers and work towards a more inclusive and equitable society for all, as and where possible. Our peers in Building and Urban Design in Development (BUDD) cohort worked with a vertical occupation in São Paulo at the same time as our fieldwork research and there is a saying painted on a wall outside the occupation that is relevant to us: ‘quem não luta tá morto’ (he/she who doesn’t fight, is dead) (Dávila and Ruf, 2009). De-marginalisation concerns us all, everywhere, and we hope that we have been able to expand your horizons within and beyond the confines of São Paulo through our mapping and have provoked questions about transgender migrants and refugees in your respective communities.

Figure 23.

Figure 23.

Figure 24.

Reference List by Section:

Background:

Associação Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais (2018) ‘História’, Associação Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais, 16 January. Available at: https://antrabrasil.org/historia/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Brown, W. (2006) ‘Tolerance as a Discourse of Depoliticization’, in Regulating Aversion. Princeton University Press (Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire), pp. 1–24. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j. ctt7st91.4 (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Cai, D. et al. (2024a) What is the extent of marginalisation of trans migrant and refugee individuals in São Paulo and what are organisations doing to combat marginalisation? A Research Report on the Work of Casarão Brazil? University College London.

Casarão Brasil - Associação LGBTI (no date) Casarão Brasil. Available at: https://www.casaraobrasil.org.br (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

CEDEC, (Centro de Estudos de Cultura Contemporânea) (2022) ‘Mapeamento da população TRANS no município de São Paulo – Cedec’. Available at: https://www.cedec.org.br/mapeamento-da-populacao-trans-no-municipio-de-sao-paulo/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Corrales, J. (2015) ‘The Politics of LGBT Rights in Latin America and the Caribbean: Research Agendas’, European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, (100), pp. 53–62.

Ferreira, B. de O. and Nascimento, M. (2022) ‘Construction of LGBT health policies in Brazil: a historical perspective and contemporary challenges’, Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 27(10), pp. 3825–3834. Available at: https:// doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320222710.06422022.

Lamond, I.R. (2018) ‘The challenge of articulating human rights at an LGBT “mega-event”: a personal reflection on Sao Paulo Pride 2017’, Leisure Studies, 37(1), pp. 36–48. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436 7.2017.1419370.

Prefeitura de São Paulo (n.d). Transcidadania: Entenda como funciona. Available at: https://www.capital. sp.gov.br/noticia/transcidadania-entenda-como-funciona (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Prefeitura de São Paulo (2020) ‘Plano de trabalho de Casarão e a Prefeitura de São Paulo’. Refugiados LGBT são discriminados pelos próprios conterrâneos, diz pesquisador (2019) Folha de S.Paulo. Available at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/2019/12/refugiados-lgbt-sao-discriminados-pelos-proprios-conterraneos-diz-pesquisador.shtml (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Prefeitura da Cidade de São Paulo (2024) Transcidadania | Secretaria Municipal de Direitos Humanos e Cidadania |. Prefeitura da Cidade de São Paulo. Available at: https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/direitos_humanos/lgbti/programas_e_projetos/index.php?p=150965 (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Salabert, Duda (2021), Os impactos da pandemia na população trans Nexo Jornal. Available at: https://www. nexojornal.com.br/os-impactos-da-pandemia-na-populacao-trans (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Trip, Cleber (2024) CASARÃO BRASIL, conheça um pouco mais desse projeto que salva vidas! Revista ViaG. Available at: https://revistaviag.com.br/casarao-brasil-conheca-um-pouco-mais-desse-projeto-que-salva-vidas/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Methodology:

Aramberri, J. (2009). The future of tourism and globalization: Some critical remarks. Futures, 41(6), pp.367–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2008.11.015.

Casarão Brasil (2022a) 1a Conferência de Direitos Humanos para Refugiados e Migrantes LGBTI - 17/03/2022. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvgeZasgR54 (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Casarão Brasil (2022b) Documentário ‘Vidas Migrantes’ - Produção Casarão Brasil - Associação LGBTI - YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrkK1KskKMk&t=262s&ab_channel=Casar%C3%A3oBrasil (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Fairclough, N. (1995) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language / Norman Fairclough. London: Longman (Language in social life series).

Kling, N. and Roidis, A. (2021). Thick Mapping – Discussion Paper. Available at: https://www.arc.ed.tum.de/ land/projekte/thick-mapping/thick-mapping-discussion-paper/ [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Conceptual Framework:

Collins, P.H. et al. (2021) ‘Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory’, Contemporary Political Theory, 20(3), pp. 690–725. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-021-00490-0.

Ikemura Amaral, A. (2022) ‘Neither Natives nor Nationals in Brazil: The “Indianisation” of Bolivian Migrants in the City of São Paulo’, Bulletin of Latin American Research, 41(1), pp. 53–68. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1111/blar.13287.

Lefebvre, H. et al. (1968) Le droit à la ville. 3e éd. Paris: Economica-Anthropos (Anthropologie).

Simpson, L.B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, [online] 3(3). Available at: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ des/article/view/22170.

Villela De Miranda, F. et al. (2019) ‘Permanent transitoriness and housing policies: Inside São Paulo’s low-income private rental market’, Radical Housing Journal, 1(2), pp. 27–43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.54825/ MVOX3365.

Findings:

Cai, D. et al. (2024b) ‘DEVP0010 Overseas Practical Engagement Casarão Interview Transcripts’, University College London.

Conclusion:

Dávila, A. and Ruf, C. (2009). Quem não luta tá morto! – POR. [online] Bineural. Available at: https://www. bineuralmonokultur.com/pt/2020/12/quem-nao-luta-ta-morto-por/ [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Full reference list spanning the entire research project:

ACNUR Brasil (n.d.). Perfil das Solicitações de Refúgio relacionadas à Orientação Sexual e à Identidade de Gênero. Available at: https://www.acnur.org/portugues/refugiolgbti/ (Accessed: 20 February 2024).

Associação Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais (2018) ‘História’, Associação Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais, 16 January. Available at: https://antrabrasil.org/historia/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Aramberri, J. (2009). The future of tourism and globalization: Some critical remarks. Futures, 41(6), pp.367–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2008.11.015.

BBC News Brasil (no date) ‘Agressões em casa, discriminação e risco de morte: os dramas das “refugiadas” trans brasileiras’. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-37999436 (Accessed: 20 February 2024).

Belmont, F. and Ferreira, A.Á. (2020) ‘Global South Perspectives on Stonewall after 50 Years, Part II—Brazilian Stonewalls: Radical Politics and Lesbian Activism’, Contexto Internacional, 42, pp. 685–703. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2019420300008.

Brasil facilita refúgio para pessoas LGBTQIA+, mas acolhida ainda é desafio (2023) Folha de S.Paulo. Available at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/2023/06/brasil-facilita-refugio-para-pessoas-lgbtqia-mas-acolhida-ainda-e-desafio.shtml (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Brasil, J. do (2023) Brasil já concedeu 134 pedidos de refúgio por perseguição sexual, Brasil. Available at: https://www.jb.com.br/pais/2018/11/960680-brasil-ja-concedeu-134-pedidos-de-refugio-por-perseguicaosexual.html (Accessed: 20 February 2024).

Britto, C.C. and Machado, R. dos S. (2020) ‘Informação e patrimônio cultural LGBT: as mobilizações em torno da patrimonialização da Parada do Orgulho LGBT de São Paulo’, Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação, 25, pp. 01–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5007/1518-2924.2020. e70964.

Brown, W. (2006) ‘Tolerance as a Discourse of Depoliticization’, in Regulating Aversion. Princeton University Press (Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire), pp. 1–24. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j. ctt7st91.4 (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Cai, D. et al. (2024a) What is the extent of marginalisation of trans migrant and refugee individuals in São Paulo and what are organisations doing to combat marginalisation? A Research Report on the Work of Casarão Brazil? University College London.

Cai, D. et al. (2024b) ‘DEVP0010 Overseas Practical Engagement Casarão Interview Transcripts’, University College London.

Casarão Brasil (2022a) 1a Conferência de Direitos Humanos para Refugiados e Migrantes LGBTI - 17/03/2022. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvgeZasgR54 (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Casarão Brasil (2022b) Documentário ‘Vidas Migrantes’ - Produção Casarão Brasil - Associação LGBTI - YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrkK1KskKMk&t=262s&ab_channel=Casar%C3%A3oBrasil (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Casarão Brasil - Associação LGBTI (no date) Casarão Brasil. Available at: https://www.casaraobrasil.org.br

(Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Casarão Brasil - Associação LGBTI (@casarao_brasil) • Instagram photos and videos (no date). Available at: https://www.instagram.com/casarao_brasil/ (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Castro Seixas, E. (2021) ‘Urban (Digital) Play and Right to the City: A Critical Perspective’, Frontiers in Psychology, 12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636111.

CEDEC, (Centro de Estudos de Cultura Contemporânea) (2022) ‘Mapeamento da população TRANS no município de São Paulo – Cedec’. Available at: https://www.cedec.org.br/mapeamento-da-populacao-trans-no-municipio-de-sao-paulo/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Collins, P.H. et al. (2021) ‘Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory’, Contemporary Political Theory, 20(3), pp. 690–725. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-021-00490-0.

Consumo, M. do (2020) Migrações LGBT na cidade de São Paulo. Available at: https://memorialdoconsumo. espm.edu.br/migracoes-lgbt-na-cidade-de-sao-paulo/ (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Corrales, J. (2015) ‘The Politics of LGBT Rights in Latin America and the Caribbean: Research Agendas’, European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe, (100), pp. 53–62.

Cowie, S. (2017) ‘Inside Crackland: the open-air drug market that São Paulo just can’t kick’, The Guardian, 27 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/27/inside-crackland-open-air-crackmarket-sao-paulo (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Dávila, A. and Ruf, C. (2009). Quem não luta tá morto! – POR. [online] Bineural. Available at: https://www. bineuralmonokultur.com/pt/2020/12/quem-nao-luta-ta-morto-por/ [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Davis, K. (2008) Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful - Kathy Davis, 2008. Available at: https://journals-sagepub-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/doi/ abs/10.1177/1464700108086364 (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Duarte, A. de S. and Cymbalista, R. (2023) ‘Casa 1, a site of LGBTQ memory in São Paulo, Brazil’, Memory Studies, 16(2), pp. 243–263. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980211073089.

Fairclough, N. (1995) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language / Norman Fairclough.. London: Longman (Language in social life series).

Ferreira, B. de O. and Nascimento, M. (2022) ‘Construction of LGBT health policies in Brazil: a historical perspective and contemporary challenges’, Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 27(10), pp. 3825–3834. Available at: https:// doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320222710.06422022.

Food insecurity in a Brazilian transgender sample during the COVID-19 pandemic | PLOS ONE (no date). Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0284257 (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Galego, D. (2023) ‘Brazil’s LGBTQ public policy: A Potemkin policy?’, Latin American Policy, 14(3), pp. 442–466. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/lamp.12311.

Gamrani, S. et al. (2021) ‘Cities with Pride: Inclusive Urban Planning with LGBTQ + People’, Ciudades Sostenibles, 28 June. Available at: https://blogs.iadb.org/ciudades-sostenibles/en/cities-with-pride-inclusive-urban-planning-with-lgbtq-people/ (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Gomes, S.M. et al. (2023) ‘Food insecurity in a Brazilian transgender sample during the COVID-19 pandemic’, PLOS ONE. Edited by C. Infante Xibille, 18(5), p. e0284257. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0284257.

Halberstam, J. (2005) In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: NYU Press. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/193/monograph/book/10698 (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Holston, J. (2009) ‘Insurgent Citizenship in an Era of Global Urban Peripheries’, City & Society, 21(2), pp. 245–267. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01024.x. Home (no date) lgbt+movimento. Available at: https://lgbtmaismovimento.com.br/ (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Ikemura Amaral, A. (2022) ‘Neither Natives nor Nationals in Brazil: The “Indianisation” of Bolivian Migrants in the City of São Paulo’, Bulletin of Latin American Research, 41(1), pp. 53–68. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1111/blar.13287.

Jaramillo-Dent, D. et al. (2023) ‘Digital Leisure and Aspirational Work among Venezuelan Refugee and Migrant Women in Brazil’, in P. Arora, U. Raman, and R. König (eds) Feminist Futures of Work. Amsterdam University Press (Reimagining Labour in the Digital Economy), pp. 241–252. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/ jj.2711713.23.

Khawas, N. (2022) ‘Striving for Urban Space: A Case of Street Vendors of Pokhara, Nepal’, Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, pp. 80–88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3126/dsaj.v16i01.50933.

Kling, N. and Roidis, A. (2021). Thick Mapping – Discussion Paper. Available at: https://www.arc.ed.tum.de/ land/projekte/thick-mapping/thick-mapping-discussion-paper/ [Accessed 16 May 2024].

Lamond, I.R. (2018) ‘The challenge of articulating human rights at an LGBT “mega-event”: a personal reflection on Sao Paulo Pride 2017’, Leisure Studies, 37(1), pp. 36–48. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436 7.2017.1419370.

Lefebvre, H. et al. (1968) Le droit à la ville. 3e éd. Paris: Economica-Anthropos (Anthropologie).

Leite, M., Zanetti, V. and Toniolo, M.A. (2020) ‘TERRITORIALIDADES LGBTs: : UM ESTUDO DA REPÚBLICA E DO BAIXO AUGUSTA NO CENTRO DA CIDADE DE SÃO PAULO’, Sociedade e Território, 32(1), pp. 96–114. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21680/2177-8396.2020v32n1ID19925.

Pan American Health Organization (2008) Campaigns against Homophobia in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization. Available at: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/campaigns-against-homophobia-argentina-brazil-colombia-and-mexico (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Pinheiro, C.V.S. and Martinez, E.D.M. (2023) ‘THE TRANSCIDADANIA PROGRAM: achievements, representativeness and narrative disputes’, Caderno CRH, 36, p. e023005. Portfolio Casarão Brasil | PDF | LGBT | Estudos LGBTQIA+ (no date) Scribd. Available at: https://pt.scribd.com/ document/464521056/Portfolio-Casarao-Brasil (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Prefeitura de São Paulo (2020) ‘Plano de trabalho de Casarão e a Prefeitura de São Paulo’. Refugiados LGBT são discriminados pelos próprios conterrâneos, diz pesquisador (2019) Folha de S.Paulo. Available at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/2019/12/refugiados-lgbt-sao-discriminados-pelos-proprios-conterraneos-diz-pesquisador.shtml (Accessed: 1 March 2024).

Ribeiro, E.P. dos S. and Bernardino, M. (2019) ‘Homotransphobia in Brazil: From School to Society’, Global Research in Higher Education, 2(4), p. 129. Available at: https://doi.org/10.22158/grhe.v2n4p129.

Salabert, Duda (2021), Os impactos da pandemia na população trans Nexo Jornal. Available at: https://www.

nexojornal.com.br/os-impactos-da-pandemia-na-populacao-trans (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Setor, R.O. 3o (2022) Casarão Brasil realiza nova campanha para ajudar comunidade LGBTI, Observatório do 3° Setor. Available at: https://observatorio3setor.org.br/noticias/casarao-brasil-realiza-nova-campanha-para-ajudar-comunidade-lgbti/ (Accessed: 14 March 2024).

Setor, R.O. 3o (2023) Organização irá acolher refugiados LGBTQI+ em São Paulo, Observatório do 3° Setor. Available at: https://observatorio3setor.org.br/noticias/organizacao-ira-acolher-refugiados-lgbtqi-em-sao-paulo/ (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Sex at the Margins: Migration, labour markets and the rescue industry | Feminist Review (no date). Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/fr.2010.23 (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

da Silva Theodoro, H.G. (2023) ‘Spaces of violence in the case of LGBTIQ+ immigration’, Estudos Feministas, 31(1), pp. 1–13.

Simpson, L.B. (2014) ‘Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3). Available at: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/ view/22170 (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Simpson, L.B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, [online] 3(3). Available at: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ des/article/view/22170.

Su, Y. and Valiquette, T. (2022) ‘“They Kill Us Trans Women”: Migration, informal labour, and sex work among trans Venezuelan asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Brazil during COVID-19’, Anti-Trafficking Review, (19), pp. 119–124. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201222198.

Theodoro, H.G.S. and Cogo, D. (2019) ‘LGBTQI+ Immigrants and Refugees in the City of São Paulo: Uses of Icts in a South-South Mobility Context’, Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication [Preprint], (17). Available at: https://doi.org/10.4000/rfsic.7053.

Prefeitura da Cidade de São Paulo (2024) Transcidadania | Secretaria Municipal de Direitos Humanos e Cidadania |. Prefeitura da Cidade de São Paulo. Available at: https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/direitos_humanos/lgbti/programas_e_projetos/index.php?p=150965 (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Transcidadania: Entenda como funciona (no date) Prefeitura. Available at: https://www.capital.sp.gov.br/ noticia/transcidadania-entenda-como-funciona (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Trip, Cleber (2024) CASARÃO BRASIL, conheça um pouco mais desse projeto que salva vidas! Revista ViaG. Available at: https://revistaviag.com.br/casarao-brasil-conheca-um-pouco-mais-desse-projeto-que-salva-vidas/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Türk, V. (2022) ‘Ensuring protection for LGBTI Persons of Concern’. Vartabedian, J. (2018) Brazilian ‘Travesti’ Migrations: Gender, Sexualities and Embodiment Experiences. Cham: Springer International Publishing (Genders and Sexualities in the Social Sciences). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77101-4.

Villela De Miranda, F. et al. (2019) ‘Permanent transitoriness and housing policies: Inside São Paulo’s low-income private rental market’, Radical Housing Journal, 1(2), pp. 27–43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.54825/ MVOX3365.

Zaken, M. van B. (2018) Equal rights for LGBTIQ+’s - Human rights - Government.nl. Ministerie van Algemene Zaken. Available at: https://www.government.nl/topics/human-rights/human-rights-worldwide/ equal-rights-for-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-and-intersex-lgbti (Accessed: 15 March 2024).

Contributors:

Dipal Mistry

Sumayyah Mohamoud

Longrui Han

Deyu Cai

Longrui Liang

Backcover: Esteban Llano, São Paulo, 2024

This pamphlet is published as part of a summative requirement of DEVP0010: Development in Practice (2023-2024 cohort) under the Bartlett Development Planning Unit.