4 minute read

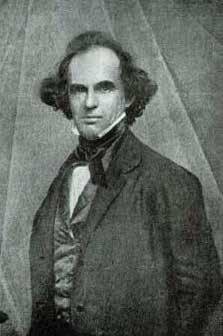

On Conscience & Kittens: The Two Minds of Nathaniel Hawthorne

BY ALIDA ORZECHOWSKI

If you were asked to supply a few words describing the American gothic fiction author Nathaniel Hawthorne, it’s probably safe to assume ‘funny’ would not be among them.

Known for his dark romances full of guilt, torment, suffering, and sin, with nary a happy ending to be found, it seems quite improbable that anything even remotely humorous could emerge from this brooding cobbler of words.

The fact that Hawthorne spent the better part of twelve years holed up in his bedroom like a moody teenager, scribbling madly in his notebooks certainly didn’t help to normalize his relationship with the world. If you’ve ever seen the movie Beetlejuice where Wynona Rider, dressed entirely in black, is composing a dramatic goodbye letter in which she declares, “I am utterly… alone!”, it probably looked a little bit like that.

Or, as Philip McFarland explains in Hawthorne in Concord, during those twelve years in his bedroom, “Hawthorne was thinking about those who are different than others, alienated, tormented, have secrets, must confess. He brooded on cruelty, suffering, and guilt, on decay, and death, on loneliness.”

It’s no wonder even Nathaniel seems concerned by his solitary weirdness, as he writes in an 1837 letter to his friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “I seldom venture abroad till after dark. By some witchcraft or other - for I really cannot assign any reasonable why and wherefore - I have been carried apart from the main current of life, and find it impossible to get back again...I have put me into a dungeon; and now, I cannot find the key to let myself out…”

The key to his timely escape would turn out to be the equally strange and lonely little soul of Sophia Peabody, introduced to Hawthorne by her sister, Elizabeth. In a meeting of true minds, Sophia and Nathaniel were married on July 9th, 1842 and moved immediately to the Old Manse in Concord to continue their utter aloneness with each other. From this moment forward, Hawthorne’s journals undergo a radical transformation. He was always a keen observer, but suddenly all is light, and sweetness, and beauty, as he proclaims their new home Paradise, and themselves, Adam and Eve.

Sophia Peabody Hawthorne

commons.wikimedia.org

Into these blissful musings is woven a gently sardonic humor, rarely seen in his early journals, such as when he chides lesser humans for the unforgivable sin of interrupting their honeymoon. “One rash mortal, on the second Sunday after our arrival, obtruded himself upon us in a gig. There have since been three or four callers, who preposterously think that the courtesies of the lower world are to be responded to by people whose home is in Paradise…” As if the mere idea of visitors was not insulting enough, it appears there was some sort of problem with the water at the Old Manse upon their arrival there. Hawthorne feels this is decidedly unacceptable for Heavenly residents, and he takes up his grievance directly with the great Landlord in the sky. “…it is one of the drawbacks upon our Paradise, that it contains no water fit either to drink or bathe in; so that the showers of Heaven have become, in good truth, a godsend. I wonder why Providence does not cause a clear, cold fountain to bubble up at our doorstep… At present, we are under the ridiculous necessity of sending to the outer world for water. Only imagine Adam trudging out of Paradise with a bucket in each hand, to get water to drink, or for Eve to bathe in! Intolerable!”

The Old Manse

commons.wikimedia.org

Having got that off his chest, the almost unrecognizable Hawthorne from just months ago concludes his petition with an adorable and wholly ungothic request, “Also, in the way of future favors, a kitten would be very acceptable.”

This from the man who would soon gift us with The Scarlet Letter, a novel that would immediately take its place on the top ten list for Least Fun Books Ever Written.

With the striking exception of his nonfiction work, such as Twenty Days with Julian & Little Bunny, Hawthorne would go on to produce an impressive repertoire of sad and somber volumes, often completely at odds with the cheerful and chatty missives in his personal notebooks.

But while it’s at first difficult to reconcile the desperate depression in a book like The Blithedale Romance or the alarmingly creepy The Minister’s Black Veil with what is Hawthorne’s visibly joyful life, there remain definite hints of the original struggle between good and evil that so profoundly permeates his literature.

Illustration from The Minister’s Black Veil. The artist was depicting the scene “the children fled from his approach.”

commons.wikimedia.org

In a letter to his publisher after the completion of The Marble Faun in 1860, Hawthorne returns briefly to his dark dungeon room when he reveals to James Fields, “The devil himself always seems to get in my inkstand, and I can only exorcise him by pensfull at a time.”

Whatever demons clung to his inner psyche, Nathaniel Hawthorne seemingly managed to compartmentalize these, and, when they proved overwhelming, channelled them outward through his pen, as if by banishing them to the public realm, he could reserve only what was wholesome and good for his private life. Like kittens.

You might be delighted to know that Hawthorne’s cheeky prayer at the Old Manse was answered just a short time later with the addition of a little black kitten to the family, whom they named ‘Pigwiggen’. And to the great disappointment of melancholy writers everywhere, they all lived happily ever after.

If you’d like to learn more about Nathaniel Hawthorne and his personal journals, Concord Tour Company recommends “The Business of Reflection: Hawthorne in His Notebooks,” edited by Robert Milder and Randall Fuller.