4 minute read

Pioneer of time and motion study

by James Nalley

Before the turn of the 20th century, a Fairfield-born man graduated from high school and broke into the construction industry as a bricklayer. According to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), “In the course of his work, he observed that each bricklayer approached his job differently, some seemingly more efficient than others. He then began analyzing their motions to determine which approach to bricklaying was the best.” Eventually, his expertise as an efficiency expert made him renowned in the field of scientific management (the theory of management that analyzes workflows to improve economic and labor efficiency). He also became a pioneer in time and motion study. As for this field, time study focused on establishing standard times (i.e., the amount of time that should be allowed for an average worker to process one work unit at a normal pace), while motion study aimed at improving work methods. The two techniques were eventually integrated into a widely accepted method, which is still applied today in industrial and service organizations, including banks, schools, and hospitals.

Advertisement

Frank Bunker Gilbreth was born in Fairfield on July 7, 1868. When Gilbreth was three years of age, his father died suddenly from pneumonia. After his father’s death, his mother moved the family to Andover, Massachusetts.

According to the book, Making Time: Lillian Moller Gilbreth (2004), by Jane Lancaster, “The substantial estate left by her husband was managed by her husband’s family. By the fall of 1878, the money had been lost or stolen, forcing his mother to find a way to make a living…She opened a boarding house since the salary of a schoolteacher could not support the family.”

Meanwhile, Gilbreth was not a good student. After his mother homeschooled him for one year, he attended Boston’s English High School, and his grades dramatically improved, especially in math and science. Although he took the entrance examinations for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he decided to go to work, rather than attend college. As stated earlier, at the age of 17, Gilbreth became a bricklayer for the Whidden Construction Company, and gained an interest in finding the best way to execute the task. As stated by Lancaster, “He took night school classes to learn mechanical drawing and advanced rapidly in the construction company. After five years, Gilbreth became a superintendent, which allowed his mother to give up her boarding house.” At the age of 27, Gilbreth was the chief superintendent. However, after the Whiddens chose not to make him a partner, he resigned and started his own company in 1895.

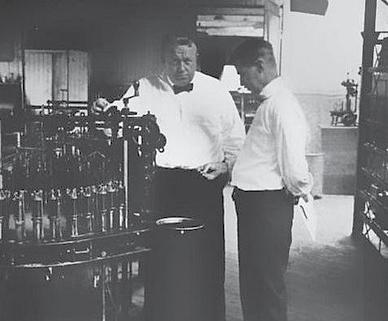

As a general contractor, Gilbreth built 90 large-scale projects across the United States, including full-scale factories, paper mills, canals, dams, and powerhouses. By 1908, he had become the inventor of 13 patents. In 1912, Gilbreth changed careers to efficiency and management engineering. This grew into a collaboration with his wife, Lillian Moller Gilbreth, after which they studied the work habits of manufacturing and clerical employees in many different industries to find ways to increase their output. In fact, he and Lillian founded a management consulting firm, Frank B. Gilbreth, Inc., to focus on such endeavors.

In World War I, Gilbreth served as a major in the U.S. Army. His assignment was to find faster and more efficient means of assembling/disassembling small arms. However, he caught rheumatic fever and then pneumonia weeks into his service and spent four months in recovery prior to being discharged. However, Gilbreth managed to reduce all motions of the hand into a combination of 17 basic motions. He also used a motion picture camera that was calibrated in fractions of minutes to time the smallest motions of the hands. He also devised the standard techniques used by armies around the world to teach recruits how to quickly disassemble/reassemble their weapons, even when blindfolded or in total darkness.

As for scientific management, the work of the Gilbreths is often association with Frederick Winslow Taylor, who was widely known for his methods (cont. on page 30)

Hathaway Mill Antiques, a sister shop to Cabot Mill Antiques in Brunswick, is a 10,000 square foot multi-dealer quality antique shop featuring period furnishings to mid-century modern. Including furniture, textiles, books, jewelry, art, and general store displays.

(cont. from page 29) to improve industrial efficiency. However, according to the Newsletter of the Gilbreth Network (1997), “The symbol of Taylorism was the stopwatch, which was used to reduce processing times. The Gilbreths, in contrast, sought to make processes more efficient by reducing the motions involved. They saw their approach as more concerned with workers’ welfare than Taylorism. This difference led to a rift between Taylor and the Gilbreths.” Interestingly, “after Taylor’s death, this rift turned into a feud between Gilbreth’s and Taylor’s followers.”

When conducting their motion studies, the Gilbreths found that to improve work efficiency, it was important to reduce unnecessary motions. They also found that such motions directly caused employee fatigue. As stated in the Newsletter of the Gilbreth Network, they focused on “reducing motions, tool redesign, parts placement, and bench and seating height. Their work also broke ground for the contemporary understanding of ergonomics.”

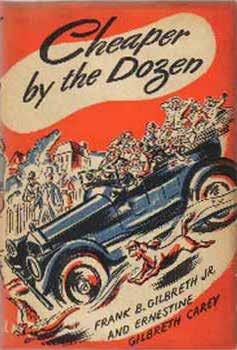

Unfortunately, due to heart damage from Gilbreth’s bout with rheumatic fever and pneumonia, he died of a heart attack on June 14, 1924. He was 55 years of age. As for their legacy, aside from their pioneering work in motion studies and efficiency management, they frequently used their large family in their experiments. Such exploits are detailed in the 1948 book Cheaper by the Dozen, written by son Frank Jr. and daughter Ernestine. This book inspired a 1950 film starring Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy, and a second (2003) and third (2022) film, which bear no resemblance to the first.

The Gilbreths also received a lifetime achievement award by the Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers.

Cheaper by the Dozen was published in 1948 and written by Frank’s son Frank Jr. and his daugter Enrestine. The book inspired a 1950 film starring Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy.

Finally, as a fitting acknowledgement of his work, Gilbreth’s saying of “I will always choose a lazy person to do a difficult job, because a lazy person will find an easy way to do it” is still commonly used today.