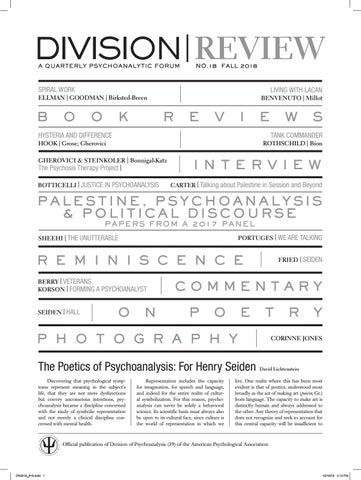

DIVISION REVIEW DIVISION A QUARTERLY PSYCHOANALYTIC FORUM

A QUARTERLY PSYCHOANALYTIC FORUM

NO.4 SUMMER 2012

NO.18 FALL 2018

SPIRAL WORK

LIVING WITH LACAN

ELLMAN | GOODMAN | Birksted-Breen

B

O

O

K

BENVENUTO | Millot

R

E

V

I

E

HYSTERIA AND DIFFERENCE

W

S

TANK COMMANDER

HOOK | Grose; Gherovici

ROTHSCHILD | Bion

GHEROVICI & STEINKOLER | Bonnigal-Katz The Psychosis Therapy Project | BOTTICELLI | JUSTICE IN PSYCHOANALYSIS

INTERVIEW CARTER | Talking about Palestine in Session and Beyond

PALESTINE, PSYCHOANALYSIS & POLITICAL DISCOURSE P A P ERS F ROM A 201 7 PA N EL

PORTUGES | WE ARE TALKING

SHEEHI | THE UNUTTERABLE

R E M I N I S C E N C E BERRY | VETERANS KORSON | FORMING A PSYCHOANALYST SEIDEN | HALL

O

N

FRIED | SEIDEN

COMMENTARY P

O

E

T

P H O T O G R A P H Y The Poetics of Psychoanalysis: For Henry Seiden Discovering that psychological symptoms represent meaning in the subject’s life, that they are not mere dysfunctions but convey unconscious intentions, psychoanalysis became a discipline concerned with the study of symbolic representation and not merely a clinical discipline concerned with mental health.

Representation includes the capacity for imagination, for speech and language, and indeed for the entire realm of cultural symbolization. For this reason, psychoanalysis can never be solely a behavioral science. Its scientific basis must always also be open to its cultural face, since culture is the world of representation in which we

R

Y

CORINNE JONES

David Lichtenstein

live. One realm where this has been most evident is that of poetics, understood most broadly as the act of making art (poiein, Gr.) from language. The capacity to make art is distinctly human and always addressed to the other. Any theory of representation that does not recognize and seek to account for this central capacity will be insufficient to

Official publication of Division of Psychoanalysis (39) of the American Psychological Association

DR2018_#18.indd 1

10/10/18 2:12 PM

CONTENTS EDITOR

David Lichtenstein

BOOK REVIEWS 4

Paula L. Ellman & Nancy R. Goodman

9

Sergio Benvenuto

Hysteria Today by Anouchka Grose

14

Derek Hook

Transgender Psychoanalysis: A Lacanian Perspective on Sexual Difference by Patricia Gherovici

16

Louis Rothschild

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Ricardo Ainslie, Christina Biedermann, Chris Bonovitz, Steven Botticelli, Ghislaine Boulanger, Muriel Dimen, Patricia Gherovici, Peter Goldberg, Adrienne Harris, Elliott Jurist, Jane Kupersmidt, Paola Mieli, Donald Moss, Ronald Naso, Donna Orange, Robert Prince, Allan Schore, Robert Stolorow, Nina Thomas, Usha Tummala, Jamieson Webster, Lynne Zeavin

La vie avec Lacan [Life With Lacan] by Catherine Millot

Derek Hook

Steven David Axelrod, J. Todd Dean, William Fried, William MacGillivray, Marian Margulies, Bettina Mathes, Henry Seiden, Manya Steinkoler

The Work of Psychoanalysis: Sexuality, Time and the Psychoanalytic Mind by Dana Birksted-Breen

12

SENIOR EDITORS

WEB SITE EDITOR

Loren Dean BOOK REVIEW EDITOR

War Memoirs: 1917-1919 by Wilfred R. Bion

Brian Smith PHOTOGRAPHY BY

Corinne Jones

INTERVIEW 20

IMAGES EDITOR

Psychosis Therapy Project: Manya Steinkoler An Innovative Psychoanalytic Treatment Program interview Dorothée Bonnigal-Katz Patricia Gherovici &

PALESTINE, PSYCHOANALYSIS & POLITICAL DISCOURSE: PAPERS FROM A 2017 PANEL 24

Steven Botticelli

27

Carter Carter

How Do We Talk about Justice in Psychoanalysis? The Case of Palestine Talking about Palestine in Session and Beyond for Mental Illness

28

Lara Sheehi

Palestine is a Four-Letter Word

31

Stephen H. Portuges

The Times Must Be Changing, Because Psychoanalysts Are Talking About Palestine

REMINISCENCE 36

William Fried

Henry Seiden: Literalist of the Imagination

Andrew Berry

43

Michael Korson

The Interpersonal Psychoanalytic Approach to Working with Veterans The Candidate’s Experience: Immersion into Disavowed and Hidden Aspects of Others, Culture, and Oneself ON POETRY

45

Henry M. Seiden

Hannah Alderfer, HHA design, NYC DIVISION | REVIEW a quarterly psychoanalytic forum published by the Division of Psychoanalysis (39) of the American Psychological Association, 2615 Amesbury Road, Winston-Salem, NC 27103. Subscription rates: $25.00 per year (four issues). Individual Copies: $7.50. Email requests: divisionreview@optonline. com or mail requests: Editor, Division/Review 80 University Place #5, New York, NY 10003 Letters to the Editor and all Submission Inquiries email the Editor: divisionreview.editor@gmail.com or send to Editor, Division/Review 80 University Place #5, New York, NY 10003 Advertising: Please direct all inquiries regarding advertising, professional notices, and announcements to divisionreview.editor@gmail.com

DIVISION | REVIEW accepts unsolicited manuscripts. They should be submitted by email to the editor: dlichtenstein@gmail.com, prepared according to the APA publication manual, and no longer than 2500 words DIVISION | REVIEW can be read online at divisionreview.com

ISSN 2166-3653

On Dreams and Poems: A Poem by Donald Hall

2

DR2018_#18.indd 2

DESIGN BY

© Division Of Psychoanalysis (39) of the American Psychological Association. All rights reserved. Nothing in this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the publisher.

COMMENTARY 40

Tim Maul

DIVISION | R E V I E W

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:12 PM

The Poetics of Psychoanalysis: For Henry Seiden from page 1 an understanding of the human subject. Thus, psychoanalysis finds itself directly concerned with the processes involved in making art. Neither an embellishment nor a decorative surplus, art, poetics, and human cultural creation are central to the focus and the object of psychoanalytic study. These thoughts are dedicated to Henry Seiden, the cofounder of this publication, who passed away last year, and who regularly wrote a column On Poetry in these pages. The point of Henry’s columns, which were collected in his book entitled The Motive for Metaphor: Brief Essays

on Poetry and Psychoanalysis (see William Fried’s essay in this issue), was that there was a fundamental link between the two disciplines, not an incidental similarity. Understanding the way experience is represented in poetry enables the psychoanalyst to understand better how it is represented in dreams, in symptoms, and indeed in the wandering speech of the psychoanalytic session. For the final time, we are publishing one of Henry’s essays, this one on a poem by Donald Hall that appears to be about a dream. It allowed Henry to reflect on imagination, representation, and the work of conveying it to another. Poems may address universal themes, but their expression is always singular, and

it is that singularity that is essential to how a poem works. Likewise, with psychoanalytic treatment, the themes may be universal and the methods repeatable, but each treatment involves a singularity in the way those themes are experienced and expressed, and without an appreciation and recognition of that singularity, no treatment can succeed. Thus, the replicable science of psychoanalytic method is met by the singularity of creative expression and in this seemingly impossible collision, a psychoanalysis may be possible. Henry Seiden was both a scientist and a poet. In his work and in his writing, this seemingly impossible collision was allowed to have its effects for the benefit of us all. z

backpack). Collage often looks the way music sounds. Klaus Voormann’s cover of The Beatles “Revolver” (1966) correctly advertised the music within as did, a decade or so later, Jamie Reid’s mismatched lettering and ravaged appropriations that mimicked the destabilizing energy of the Sex Pistols, grabbing one’s attention with the urgency of a ransom note. Corinne Jones’s work in media includes sound recording, and since I believe that everything an artist does affects everything that artist makes, I cannot disconnect her recent collages from her deep engagement with music of a wide spectrum. Even on the page, her pictures lure and promptly abandon us on a hectic but legible field of multiple directives and textural expanse that could be read as geological. They are not “easy on the eye”; early criticism of Pixar’s Toy Story series mourned the gaze’s “lack of refuge” in all things computer animated, with the pixel-driven image offering little beyond exactitude and constant stimuli in our sustained looking.

Similarly unrelenting displacements agitate Jones’s “Knock On Effect” (2018) series initially resembling the upturned jumbled contents of a board game or early “scatter” piece by the sculptor Barry Le Va. Jones’s “September, October, November” (2018) group cross-references seasonal kitsch as we careen through disproportionate reconfiguring of commercial stock images of garish decor, four poster beds, and parquet floors aligned in funhouse perspective(s) suggesting the labyrinthian distortions of the perpetually uncool M. C. Escher. Corinne Jones’s paintings and interventions firmly resist being synthesized into any form other than what they already are. Other types of pleasures are to be derived from this new work where Jones reenlists and subverts the idealized depictions of one impossible dreamworld to fabricate another. It’s a good thing for art to do. z www.corinnejones.net Tim Maul

On the Photography of Corinne Jones Modern two-dimensional collage first appeared in women's scrap books of the later 1800s during an era of affordable photography, increased leisure time, and the availability of disposable print culture—a fortuitous meeting of the burgeoning publishing industry with the stationary store. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s modest but important 2010 exhibition Playing With Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage demonstrated that the recycling of mechanical reproductions began not with cubist experiments of gluing extractions of the real world onto paper, but in the mischievous and uncanny amusements of women with both time and scissors at hand. Since this use of craft originated outside the artist’s studio without the associated manual skills, collage/assemblage remains a less gendered medium taken up by reclusive occultists (as exemplified by Joseph Cornell), outsiders wanting in (Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns) and furtive adolescents (any kid’s bedroom wall, locker interior, or

3

DR2018_#18.indd 3

DIVISION | R E V I E W

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:12 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

A Voyage in Spiraling Motion In her opening chapter, Birksted-Breen writes of psychoanalytic treatment being a voyage. An essential ingredient of the voyage is the intimacy of two psyches being with The Work of Psychoanalysis: Sexuality, Time, and The Psychoanalytic Mind. By Dana Birksted-Breen Routledge, 300pp., $55.80, 2016 each other. Another image of movement is presented in the form of a “spiral” honoring non-linearity. Birksted-Breen incorporates into her style of writing the original ways she has of visiting psychoanalytic concepts. She writes of the spiraling, the back and forth, the reverberation time, to depict the mother-infant relationship contributing to psychic growth and the analyst-analysand engagement in the psychoanalytic process. Her concepts suggesting movement, space, and time become her style of writing and invite the reader to join in the journey. Moving in a spiral reflects the importance of space and time. Throughout her writing, Birksted-Breen enacts this sense of voyage and spiral that is alive in both psychoanalytic theory and in the hours of clinical work. Concepts are revisited in different theoretical contexts, with abundant clinical examples, and are articulated and revisited throughout the book. Birksted-Breen is currently editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis (IJP), and is embarking on the second five-year term of her editorship as she plans for the IJP centennial celebration. She references contributions from all regions and across time, from 1893-2016. She brings in her thinking from papers written early in her psychoanalytic career, and a significant proportion of chapters are current, presenting new ideas and synthesis of her thinking. With recognition of her lifetime in psychoanalysis since the early 1970s, she begins with a review of her very first research contribution on first pregnancies—an instance of life’s moments requiring change if “lived through rather than gone through.” Birksted-Breen informs us that her ordering of chapters is not based on publication date, but more on the evolution of the book. The course of the book moves from sexuality to symbolization to the psychic work of the analyst and phenomena of the analytic dyad, with themes of sexuality, temporality, and disturbances of identity. With the journey through Birksted-Breen’s chapters, one has a rich and deepening sense of psychoanalytic concepts, traditions, and a high regard for Birksted-Breen’s clinical astuteness. In our review, we take the voyage in a spiraling fashion, stopping along the way

to explore femininity, penis-as-link, trauma, reverberation time, and termination. Spiraling 1: Femininity Birksted-Breen’s Chapter Three, “The feminine and unconscious representation of femininity, a duality at the heart of femininity,” was written in the same year (1996) as the publication of a complete volume of Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association devoted to femininity and female identity, and brings focus to a psychoanalytic understanding of femininity. Birksted-Breen provides a full literature review of the topic, including the other side of the Atlantic, not typical in most of her chapters. She reviews the North American perspective on the concept of gender identity and primary femininity and emphasizes that both sides of the Atlantic want to understand what is feminine before language, that is, what is primary. Having written papers on the topic of primary femininity, we appreciate the integration of thinking from our side of the Atlantic (Basseches et al., 1996; Fritsch et al., 2001). She brings her emphasis to the duality at the heart of femininity, the contradiction of negative and positive femininity, what is lacking and what is present. This was an era of wrestling with what is beyond the bedrock of penis envy, the lack, and Birksted-Breen was very much present. Her work reminds us of the study group we engaged in, seven women who trained together many years ago to study our work with women as women psychoanalysts. Out of our study came two associated papers on femininity and psychoanalysis. The first, “Hearing What Cannot Be Seen: A Psychoanalytic Research Group’s Inquiry into Female Sexuality” (Basseches et al., 1996), reports on our discovery of a lag between our then current theoretical ideas and our clinical practice. “The group identified our anachronistic emphasis on penis envy functioning as ‘bedrock’ and with our discussion of current writers of female development, our integration of theory and practice became more possible” (p.511). Our clinical material confirmed the view that psychic derivatives of penis envy or female genital anxiety have multiple developmental determinants and stem from varying defensive solutions. We discovered that penis envy may relate to an effort to merge with the pre-Oedipal mother or, alternatively, to a wish to pleasure the Oedipal mother. The turn to a wish for a phallus often involves an effort to move away defensively from female genital anxieties involving Oedipal-level conflicts. It is 4

DR2018_#18.indd 4

Paula L. ELLMAN and Nancy R. GOODMAN

DIVISION | R E V I E W

better to long for what one does not have than to be under superego certainty that the female genital will be harmed, raped, or closed off. And/or it may serve as a protection against the terrors of merger with the pre-Oedipal mother. Our second paper, “The Riddle of Femininity: The Interplay of Primary Femininity and the Castration Complex in Analytic Listening” (Frisch et al., 2001), reports on the study group’s exploration of the relative heuristic use of these two important organizing concepts in analytic work with female analysands. Both papers emphasize the crucial importance of openness in analytic listening when the treatment involves the working through of conflicting feminine identifications and defenses and the layering of facets of unconscious fantasy (Ellman & Goodman, 2017). Birksted-Breen, in a similar way, explores the anxieties arising from the positive and negative based in the early relationships to mother and father. She suggests that the rejection of femininity could be understood as the envious denigration of the mother and the desire to triumph over the omnipotent primal mother at the same time as being a way to deal with anxiety in relationship to the inside of the body and fear of attack, often leading to rejection of the receptive position. She brings us the clinical material of Charlotte to demonstrate the dual aspects of femininity. Charlotte’s anorexia and compulsive exercise is an attempt to control her terror of death and disintegration. With regard to her severe anxiety about damage to internal organs, the treatment allows for a negotiation of the two dimensions: “namely the acceptance of lack (and difference) and the acceptance of the feminine body (with the complex anxieties rooted in the relationship with the mother and father) and their interplay traces a woman’s experience of her own body and sexual position” (p.81). Chapter Two, the “Modalities of thought and sexual identity,” offers a broader perspective of the construction of identity and the place that gender has in organizing and being organized by identity. Birksted-Breen spirals back to her statement that there is no oneto-one relationship between actual body and psychic representation; as she said in 1996, “psychical events do not simply parallel biological determinants” (p.73). Returning to femininity, Birksted-Breen emphasizes the role of vision, the having and not having, and that feminine identity is closely connected with the capacity for symbolic thinking: “…the representation of the self in terms of masculinity and femininity will reflect levels of symbolization, which vary within the

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:12 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

individual in relation to special issues linked with sexuality (in the widest sense of the word to refer to the drives and their objects)” (p.62). Birksted-Breen speaks to the impact of psychoanalysis as “disrupting a rigid coherence” and shifting fantasy positions. Thinking of femininity brings BirkstedBreen to Chapter Four, “Sexuality in the consulting room,” and her continued focus on dualities. Here, the duality is between silent sexuality and noisy sexuality, emphasizing that sexuality underlies the analysis at all times, but manifests in different ways. Similar to the duality of life and death forces (Basseches et al., 2013), Birksted-Breen writes of silence belonging to Eros, the libidinal, motoring the transference and keeping treatment alive. In contrast, noisy sexuality “cannibalizes” and controls the object, which she attributes to the erotized phallic position often leading to fragmentation. Marie’s eating and talking are libidinized, and there is the genitalization of the oral and confusion of oral and vaginal. Psychoanalytic understanding of femininity

has journeyed far over the last 20 years, and Birksted-Breen’s chapters demonstrate the span of its development. Birksted-Breen shows how femininity is now viewed within the larger context of identity, and how it spirals through the transference where sexuality and identity are expressed within the here and now of psychoanalysis. Spiraling 2: Phallus, Penis, Mental Space, and Alterations In her chapter entitled “Phallus, penis, and mental space” (Chapter Six, pp.126138), Birksted-Breen offers a new concept compelling in its clinical and theoretical significance. We stop our voyage to take in the meanings about male and female and about thinking itself that are related to penis-aslink. It becomes clear that the phallus as fantasy is often related to a narcissistic position in which omnipotence and unreachability take precedence. Whether a male or a female patient expresses this phallic yearning through the bodily enactment of bulimic

vomiting or through an isolated search for the perfect other, phallic maneuvering tends to render contact impossible and meaningless. Penis-as-link, Birksted-Breen’s new concept, is triadic and Oedipal in object relations and in intercourse within one’s mind, taking place between analyst and analysand. As opposed to the binary aspect of the phallic vision along the lines of presence and absence, the structuring and linking function of the penis of the tripartite world of the mother, linked with but different from the father, and child in relation to the parents, makes for a more complex world…. In this position, good and bad, powerful and powerless, masculine and feminine are encompassed rather than being mutually exclusive. (p.130) Penis-as-link is a function just as the Oedipal couple function to connect and create. The use of the word “link” is crucial in recognizing the bond that becomes possible when the constellations of fantasies about the penis include relationships and love. While there may be fantasies about the phallus and about penis-as-link, their content in relation to sexual excitement and to the other are quite different in their aim. While the phallus belongs to the mental configuration that allows only for the ‘all-or-nothing’ distinction, hence to the domain of omnipotence, and is an attempt away from triangulation, the penis-as-link, which links mother and father, underpins Oedipal and bisexual mental functioning and hence has a structuring role which underpins the process of thinking. (p.137) The penis-as-link brings about contact between analyst and analysand to bring observation and thought to the analytic session, as does knowledge of the Oedipal couple bring about the structure and containment of powerful effects including desire, envy, and acceptance of reality. “It is this structuring function of the penis that creates the necessary space leading to the possibility of separateness and link” (p.131). The phallus and penis-as-link have different relations to space—phallic narcissism closes space and penis-as-link opens space, while simultaneously allowing for observation, knowledge, and structure. When the articulation of a new concept leads to listening in a different way to clinical material, one recognizes the value of that concept. With Birksted-Breen’s concept in mind, one of us (N. Goodman) heard her patient, Mr. C, in a new way. Mr. C was thinking of a tender feeling he had in a dream when he was reunited with a childhood female friend. “I felt tender, romantic. I do not think it was erotic, maybe a little,

5

DR2018_#18.indd 5

DIVISION | R E V I E W

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

but it made me nervous.” He then spoke of the familiar terrifying feeling of being seduced by his mother’s need for him and his search for his own phallic presence through pornography. Goodman realized the awakening of a new position in her ability to think and in connection with the patient. She was able to say to Mr. C., “You and your penis were linking with your childhood girl friend in a tender way, and something made you anxious about linking in that way.” She later brought it into the transference by saying, “Tender feelings toward me acknowledge our thinking together, a meeting that is somewhat romantic and not highly erotic.” Mr. C. replied that hearing his analyst’s voice made him want to turn away and tell her how unworthy she was—that there would be no contact. The analyst understood how his erotic solitary turning to pornography was in the phallic domain, while the new/old feelings were in the penis-as-link domain. As with male patients that BirkstedBreen mentions in this article, the patient’s father is conspicuously absent. We are wondering if hearing the new penis-as-link is like the infant hearing the existence of the primal scene in the mother’s mind bringing about space. Penis-as-link carries the knowledge of coupling. “What I call penis-as-link is part of the position or configuration in which the vagina is known” (p.128). We found this linking to the literature on female genital anxieties, such as the article by Arlene Kramer Richards, “The Influence of Sphincter Control and Genital Sensation on Body Image and Gender Identity in Women” (1992), in which knowledge of the internal genital is known by women and placed in compromise formation fantasies. It is good to recognize the knowing of the female genitals across psychoanalytic continents. The penis-as-link creates space and depth and the possibility of meaning that resides in the multiple layers of the unconscious. “Mental space and the capacity to think are created by the structure that allows for separateness and linking between internal objects, and the self and other, instead of fusion and fragmentation” (p.136).

resonance in the work of Birksted-Breen in her thinking about Nachträglichkeit and her emphasis on how the reversal of time relates to thinking and symbolization. For Birksted-Breen, the discovery of traumatic recollections, unconscious fantasies, and affects becomes articulated in the landscapes of trauma that are located in the transference and countertransference.

sessions. She focuses often on the path from sexuality to the symbolic.

Spiraling 3: Trauma Birksted-Breen takes up psychic trauma in various ways throughout this volume. As the unknown of trauma becomes symbolized, time takes shape. In our way of thinking, articulated in Finding Unconscious Fantasy in Narrative, Trauma, and Body Pain: A Clinical Guide (2017), we emphasized the important recognition of the way the traumatic, and the unconscious fantasies gathered around it, are discovered and uncovered with temporality. That is, the “here and now” leads back to the trauma that requires symbolization. We find

Birksted-Breen revisits “fort/da” throughout her writing. Uncovering the traumatic mind appears to be a particular version of here/there—it is near; it is also at a distance. The knowing of the trauma consciously and unconsciously takes place in time, pulling it forward and pushing it away. Winnicott’s premise that the trauma of the past is anticipated in the future is useful here, as Birksted-Breen states, “…the trauma needs to be experienced in the here and now in order to become a past trauma” (p.144). Throughout her writing, the powerful and overwhelming effects of the past become known in the frame of the analytic

clinical situations in which awareness of emotions is not available and in which there is significant lack of connection between emotion or sensation and idea and in which necessary representation is unavailable. (p.5)

6

DR2018_#18.indd 6

DIVISION | R E V I E W

My focus on the development of symbolic capacity and the connections with temporality ‘in the presence of the object’ (that is within the clinical situation) is the thread which runs throughout this book. I address in particular,

Trauma is not directly mentioned, but in essence, this is a definition of the traumatized, unconscious, overwhelmed mind. Ellman and Goodman (2017) describe a process in the treatment of trauma in which enactments puncture timelessness, the fusion defending against the

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

helplessness of trauma and of Oedipal longing. Our observations in Finding Unconscious Fantasy in Narrative, Trauma, and Body Pain (2017) identify how enactment processes in the here and now of sessions bring about narratives of the events themselves and of intermingled unconscious fantasies presenting in transference and countertransference:

Finding involves the creation of space in the mind of the patient and the analyst, and within the treatment dialogue. In cases where there is narrative and trauma we have the opportunity to recognize and listen to symbolized and unsymbolized material, and investigate the process of uncovering of networks of fantasy between analyst and patient. (Ellman & Goodman, 2017, p.4) Birksted-Breen introduces the concept of “bi-ocularity” in the analyst’s mind and as the crucial element in establishing

representation where previously there has been none. The triangle, the space, is essential to the process of symbolization: “bi-ocular…two images are overlapping but distinct and (there is the) need to retain or regain coexistence in the mind of the psychoanalyst” (p.216). For trauma to become symbolized, there must be a gap, and transformation becomes possible in “reverberation time.”

In her conceptualization, temporality evolves in a mind that gains structure through the bi-directionality of now and then. Bi-directionality is active for discovering the unconscious mind in all its dimensions. When the strong effects of now take place in treatment, Birksted-Breen considers it of the utmost importance that the analyst carries the knowledge that now is also then. “The greatest danger I believe is when the analyst has lost the temporal perspective in his or her own mind and is colluding with the patient in a malignantly denuded present” (p.142). The analyst has to be aware that time does 7

DR2018_#18.indd 7

DIVISION | R E V I E W

not stand still, a fantasy that may be multidetermined, leading to a wished-for truth that symbiosis is possible and agreed upon in a folie-a-deux of analyst and patient. Working with trauma is embedded in the ways Birksted-Breen develops her ideas on time: “…the same hatred of progressive time produces an attack on retroactive time” (p.151), emphasizing that for there to be progression, there has to be a “retrospective resignification.” This is the après-coup, the creation of meaning where trauma and nothingness existed, and where time progression results from linking. Movement forward is freed from attack, and the future becomes possible, as trauma experienced in the here and now can become past trauma. Spiraling 4: Reverberation Time On a voyage, the experience of time changes. We spiraled into variations of time as we discovered Birksted-Breen’s profound understanding of time and space: “The ‘reverberation time’ created by the mother’s and the analyst’s capacity for reverie, includes both a chronological aspect and a back-and-forth aspect between mother and infant. We can represent this as spiraling in non-even ways (because the back and forth aspect takes varying lengths of time at different moments)” (p.147). Birksted-Breen brings an important focus to reverberation time that “spirals” through most of her chapters, but especially in Chapter Seven, “Time and the après-coup,” Chapter Nine, “Reverberation time, dreaming and capacity to dream,” and Chapter Ten, “Taking time, the tempo of psychoanalysis.” BirkstedBreen addresses time as a crucial element in understanding analytic process. “One important curative factor of psychoanalysis is precisely that it is a process, that the time element is central to it” (p.155). Birksted-Breen associates her reverberation time with the many related psychoanalytic concepts that we are all so familiar with: the “containment,” “reverie,” “transitional space,” “time of sojourn,” “potential space” (Britton), “theory in practice,” “dreaming up” (Winnicott), “dreamlike flash” (Ferro), “analytic third” (Ogden), the back and forth, the spiraling, triangular space. Birksted-Breen’s description of reverberation time has a way of capturing the capacity to think, to dream. “For the infant, therefore, the time which can be tolerated will be, at first, the time of transformation within the mother’s psyche, if the mother is able herself to tolerate the time factor and not have to block or immediately eject the projections. I call ‘reverberation time’ the time it takes for disturbing elements to be assimilated, digested, and transformed” (p.147). She writes of the way thinking detaches from immediate reality, allowing for the moving back and forth in time and thereby bringing the possibility of a symbolizing process. In symbolizing, we

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

find the capacity to think, to represent, and to capture the yet known past in a new way in the present (Ellman & Goodman, 2017). Enactments contain both past and present, and have the power to bring timelessness to an end by creating the event of the enactment, which produces links between present affects and fantasy, and past memory (Ellman & Goodman, 2012). We appreciate Birksted-Breen’s emphasis on place in the dyad, where “echo reverberates back and forth with mother and infant recognizing themselves in the other” (p.183). She tells us that the primitive subjective sense of time created by the reverberation between mother and infant is where something is internalized and then becomes the basis of the capacity to dream. The dream then becomes the container of the “back and forth,” of the unconscious dialogue. For there to be an analytic process, here and now is mediated by reverie and the analyst’s capacity to give meaning. The mediation by analyst’s psyche in the now and the then, and the reverberation of the patient’s experience, enables a change in temporality in the patient’s psychic functioning. Time becomes linked with the space in the dyad and the space across time. One of us (Ellman) was reminded of an analysand, a young woman in the termination phase of her analysis, who had a narcissistically limited mother unable to imagine her child’s mind, and who longed for closeness with a feminine object who could digest her thoughts. Coming to the end of a session, the analyst slipped and rather than say, “It is time for us to stop,” she said, “It is time for us to shop,” recognizing the reverberation time of having the maternal longing to provide the mother-daughter joining that had been missing. In this slip, the “there and then” became present in the “here and now” as the patient’s longings and the years of analytic exploration were mediated in the slip, “It is time to shop.” In the context of discussing reverberation time, Birksted-Breen spirals back to discussing her discrimination between the British and French models of psychoanalysis, the British here and now emphasis and the French non-linear form of temporality, their après-coup (deferred action), retrospective attribution of meaning. Birksted-Breen contends that the British “here and now” approach, while taking center stage, does not actually depart from a form of temporality, as even in the here and now, the past must remain present. With this important recognition, the present amends the past according to the principle of après-coup. Free association depends on temporality. One thing leads to another; there is time and space that is between and connects thoughts. The French use of metaphorical language speaks in one moment of different times. The notion of reverberation time links

with free association as thoughts/feelings move back and forth, and echo with unconscious processes. Birksted-Breen emphasizes that time is about tolerating frustration with positioning in the Oedipal and generational difference, the depressive position of mourning, and the capacity to think about and imagine the past and future. The work in reverberation time, the back and forth, the spiraling, rather than the straight line, makes for the central necessity of the other. The analytic dyad holds the promising potentiality for reverberation time. Spiraling 5: Termination Birksted-Breen’s final chapter on termination is quite moving. Her depiction of the termination process brings to life the powerful impact that psychoanalysis has on the mind reaching closer to its potential. Birksted-Breen describes the way self-awareness and the recognition of beginnings and endings brings about greater connection to objects, increases in symbolization, room in the mind for the reflection and recognition of time. All of these elements come together with greater human connection to others, to the future, and to one’s own deep experience. In her words: The aim of psychoanalysis is to enable the development of the capacity to reconfigure the threads in a symbolic form, enabling separation via the creation of memory of the process. (p.235) In reading this termination chapter, Ellman recognized her current immersion in a termination phase of an analysis of a 30-yearold man, having conquered potent demons of his psychic past and opened facets of his inner world that were previously inaccessible. In the depth of psychic work, both patients and analysts increase awareness of time within life and death forces. Birksted-Breen writes how representation replaces repetition. With self-awareness, the repetitions are no longer identical, and the struggle is not the same. She addresses two dimensions. There is better psychic functioning and the growth of the greater capacity to experience a loving connection to others. The second affects relationships to both external and internal objects. These two facets both … lead to an overall picture in which there is a greater ability to face psychic reality, a greater sense of responsibility without masochism, a better self-esteem and toleration of separateness and loss, a better toleration of the more disturbed parts of the self and capacity to contain these, a better protecting ‘shield/skin’ or a greater sense of an internal structure when these have been deficient. (pp.232-233) 8

DR2018_#18.indd 8

DIVISION | R E V I E W

In this beautiful quote, Birksted-Breen captures the internal growth that congeals in the termination phase. Ellman’s patient exemplifies the growth of awareness that takes place with the increase of temporality and the good-bye. He recalled a film he repeatedly watched as a child, which to this day he watches and which moves him to tears at the moment when the protagonist triumphs over an internal weakness. He remarked that lately he is reminiscing more about memories of himself as a child and said that perhaps this is the time for that, since he anticipates he will be reminiscing about the years of our work together in the near future. He wants to speak during the upcoming last month of our work about his anger at what’s been lost that he will never get back, reckoning with how his gains, his engagement and upcoming wedding, his professional advancement, the beginning of his graduate studies, his place of comfortable autonomy from his parents, his ease with his aloneness and newly found comfort with travel, poignantly bring him the sense of what he missed out on and will never rediscover. He is working at digesting the limits of our relationship, and what I cannot be for him. The earlier pressure, anxiety, and panic has moved away, and what has moved in is a sense of sadness along with an energized hopefulness in his own found capacities without the paralyzing fears of destruction. As our spiraling voyage with BirkstedBreen is at an end, we are intensely aware of the richness of our travel with her. Ideas of temporality, sexuality, and being with the unconscious are present for us in new and transforming ways, adding to our understanding of the psychoanalytic process. We have spanned the continents with Birksted-Breen as she has integrated psychoanalytic thinkers from across expanses of geography and time. z REFERENCES Basseches, H. I., Ellman, P. L., Elmendorf, S., Fritsch, E., Goodman, N. R., Helm, F., & Rockwell, S. (1996). Hearing what cannot be seen: a psychoanalytic research group’s inquiry into female sexuality. Journal of the American Psychoanalytical Association, 44S, 511-528. Basseches, H. I., Ellman, P. L., & Goodman, N. R. (Eds.). (2013). The battle of life and death forces in sadomasochism: Clinical perspectives. London, UK: Karnac. Birksted-Breen, D. (2016). The work of psychoanalysis: Sexuality, time and the psychoanalytic mind. London, UK and New York, NY: Routledge. Ellman, P. L. & Goodman, N. R. (2012). Enactment: Opportunity for symbolising trauma. In A. Frosch (Ed.), Absolute truth and unbearable psychic pain: Psychoanalytic perspectives on concrete experience. Confederation of Independent Psychoanalytical Studies series on the boundaries of psychoanalysis. London, UK: Karnac. Ellman, P. L. & Goodman, N. R. (2017). Finding unconscious fantasy. In P. L. Ellman and N. R. Goodman (Eds.), Finding unconscious fantasy in narrative, trauma, and body pain (pp.1-22). London, UK: Routledge. Fritsch, E., Ellman, P. L., Basseches, H., Elmendorf, S., Goodman, N. R., Helm, F., & Rockwell, S. (2001). The riddle of femininity: The interplay of primary femininity and the castration complex in analytic listening. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 82(6), 1171-1182. Richards, A. K. (1992). The influence of sphincter control and genital sensation on body image and gender identity in women. Psychoanalytical Quarterly, LXI, 331–351.

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

Catherine Millot’s Life With Lacan The celebrated Orson Welles film Citizen Kane (1941) develops as a biographical reconstruction. A journalist has to reconstruct the life of media mogul and tycoon Life With Lacan By Catherine Millot, Andrew Brown (Trans.) Polity, 128pp., $19.95, 2018 Charles Foster Kane immediately after his death. He composes a sort of jigsaw puzzle consisting of interviews with various characters who had shared part of their lives with Kane. The several witness accounts make

up a multifaceted image of this figure, but what the journalist mainly wants to find out is why, before dying, Kane uttered the word “Rosebud.” Who or what was Rosebud? This signifier seems to indicate a missing piece of the jigsaw. As well as the unopened flower of a rose, Rosebud is also used to indicate a rosy mouth, delicate and rose-tinted. As an orifice with mucosa, the term also evokes the large and small lips of the vagina. Rosebud would indeed seem to refer to a woman, but it is also a signifier of what in French is

known as béance: what remains open, like a slit vein or a half-open mouth. The journalist eventually discovers nothing in particular, with the final revelation—a MacGuffin, in cinema language—being reserved for the spectator; a revelation, however, which leaves open the question of the ultimate meaning of the signifier uttered on the verge of death. The Welles film came to my mind after reading La vie avec Lacan1 (“Life with Lacan”) by Catherine Millot (2017). The author, a psychoanalyst and writer, was

Lacan biography by Elisabeth Roudinesco (1997). We have a wealth of anecdotes, some quite palatable, others more or less imaginary, on the character of Lacan. We have to set these accounts side by side, a little like the journalist in Citizen Kane, if we want to compose the Lacan jigsaw. But are we left with a Rosebud to find a solution to? I think we are. In short, I believe a Lacan enigma does exist. Various friends I respect have said that they don’t think this brief volume is worth much. I wonder what motivates this severe

Lacan’s pupil-lover and partner in the 1970s. He was 43 years older than she was, and she notes that she has finished writing the book being the same age Lacan was when she met him: he was 72 at the time. Millot’s is a witness account of her personal experience with Lacan, one that adds to the various testimonies, all with different perspectives, published over the years by Lacan’s relatives, friends, pupils, and analysands; and to the list, we can add the bulky

judgment. A witness account owes its interest not to whether it results in a more or less well-written book, or whether it’s more or less profound, but to the mere fact that it records and informs us on aspects of a life that particularly interests us. Several Lacanians abhor biographical writings on Lacan in general; “it’s only gossip,” they say, but ultimately, all historiography is a form of gossip. Analysis itself may somehow appear as gossip on oneself, translating into words something intimate and unspeakable. Perhaps some would rather

1. Gallimard, Paris, 2016. The pages quoted are taken from the Italian edition, Vita con Lacan, Raffaello Cortina, Milano, 2017. 9

DR2018_#18.indd 9

Sergio Benvenuto

DIVISION | R E V I E W

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

see hagiographies about Lacan rather than biographies. Serious biographies always involve a halo of demystification, and I can see why those who are devoted to a form of personality cult to Lacan are unable to accept them. In contrast, I am also interested in “gossip” on Lacan, because, as psychoanalysis teaches, psychoanalytical theories are not only the product of disembodied minds, but of specific subjects with their histories, their unconscious, and their life wounds. In addition, it is also true that every biography appeals to our voyeurism. In fact, we might have expected Millot to tell us about her sexual relations with Lacan, or her relations with Lacan’s wife Sylvia; why not? But the more we find out about eminent women and men, the more we are haunted by something similar to Rosebud: there’s always something that escapes us, a sort of gap. Basically, who was Lacan really? One of Lacan’s behaviors those most intimate with him point out is quite striking: the way he drove. He would drive over the speed limit, failing to give way, slipping into the emergency lanes to avoid a traffic jam; in short, he would jeopardize his own life and those of his passengers. Even if somebody else were driving, he would immediately lose his patience at a red light, sometimes even leaving the car. This anarchism of Lacan as motorist particularly surprises me, because Lacan was the psychoanalyst who gave the most importance to the role played by the law in the unconscious and in individual destinies. For Lacan, as for Saint Paul2, the law is not an obstacle against our desire, but is, on the contrary, the condition for desire itself; it is what desire is made of and what unleashes it. Now, how to consider the fact that the theorist of the law failed to heed to the simplest of laws, the Highway Code? Do we capture here a dyscrasia between theory and life? Transgression, indeed: I think it is quite significant that Lacan clashed with the International Psychoanalytic Association not because of the content of his teaching, but for what I would call “fiscal” reasons: the fact that his sessions were variable in length (and therefore didn’t respect the fixed time, usually 45 minutes, adopted by orthodox analysts) and were usually too short. There’s nothing wrong with creating a new analytical technique, in doing short sessions, but I think it is significant that the rift broke out because Lacan failed to follow the code of the analytic setting. We come across this problematic relationship with “the rules” in several more of Lacan’s behaviors, in particular making 2. Paul, Letter to Romans, 7, 7-8.

Catherine Millot his lover while she was still his analysand and pupil. Lacan himself describes his meeting with the famous Austrian psychoanalyst Ernst Kris at the 1936 International Psychoanalytical Congress in Marienbad (Lacan, 1966). The young Lacan expressed to his colleague his wish to go to the Berlin Olympics, which were being held at the time. The point was that these were set to be Hitler’s Olympics… And Kris, a Jew, said to him in French, “ça ne se fait pas!” [“You shouldn’t do that!”] Lacan went anyway. Indeed, ça ne se fait pas. You shouldn’t go through a red light, you shouldn’t go to bed with patients, you shouldn’t do excessively short sessions, you should yield right-of-way to other vehicles… And I say this not to launch an anathema on Lacan, quite the opposite, but rather to say that Lacan was a dandy. No biographer or witness of Lacan, as far as I know, has portrayed Lacan as a dandy. Perhaps because the great dandies—Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, Raymond Roussel, etc.—don’t appear ethically correct to us. They excluded themselves from the values and tastes of the masses, boasting their freedom from the rules that applied to the common people, i.e., to the mediocre. Now, it would seem that the charming arrogance of the dandy cannot be reconciled with psychoanalysis, which is after all, whether you recognize it or not, a curative activity, a form of help, a service to the person. Can a dandy be a philanthropist or simply a doctor? Millot stresses how Lacan made common people feel comfortable, how well he could converse with psychotics; in other words, he knew how to help. Besides, if you have that mysterious charm that today we call charisma, it’s easier to help people than if you don’t have it. The dandy, therefore, feels free. Now, it so happens that Lacan always scorned to preach freedom, something that distinguishes him sharply from Sartre, the philosopher of the human being’s boundless freedom. When a TV journalist asked him a question about freedom, Lacan burst out laughing and eventually said to her, “I never talk about freedom.” He never talked about it, but he put it into practice, even if it meant breaking his neck. Millot mentions Lacan’s pupil Giacomo Contri, translator of the Écrits into Italian, and here she makes a mistake. She says Lacan was exasperated by the fact that Contri had named his Milan school “Comunione e Liberazione” [“Communion and Liberation”]. In fact, Contri had called his group “Scuola freudiana” (“Freudian School”, of which I 10

DR2018_#18.indd 10

DIVISION | R E V I E W

was a member for several years), but he was also a member of the Comunione e Liberazione movement, which we Italians know very well: it is an organization of fundamentalist Catholics, which even in politics took quite a conservative stance. Lacan actually blamed Contri for his subscription to Catholic fundamentalism. In a meeting in Milan with Contri’s pupils, he said that the two signifiers “communion” and “liberation” were deeply foreign to his teachings, which was certainly not Catholic or Communist. The analyst in particular is never free: “It cannot be said that my discourse promises you liberation from anything, because it concerns, on the contrary, fixing upon ourselves people’s suffering …” (Lacan, 1978). Millot writes: “To a transsexual who proclaimed his female essence, he never ceased to remind him during their interview of the fact that he was a man, whether he liked it or not, and that not even an operation would ever turn him into a woman” (p.42). There’s a position that would be seen as retrograde today, one that the LGBT movement would censure decisively. What prevails today is the idea that our gender is something that is assigned to us, not something we objectively are. But this is the point; Lacan did not gratify the liberal ideology according to which we should be free to be what we want to be, even with the aid of surgery and technology. The rhetoric of liberation that was so fashionable at the time both with the left and the right—“it is forbidden to forbid” (one of the famous slogans of May 1968 in Paris), the theology of liberation, and so on—was totally alien to him. In fact, several more theories countered Lacan at the time, laying claim to, in the wake of 1968, an unconditioned liberation. These included Wilhelm Reich’s apotheosis of orgasm, Deleuze and Guattari’s desiring-machines, or Jean Baudrillard’s liberational criticism. Compared to these philosophies that glorified the freedom of desire, Lacan’s thought appears a sore callback to the determinism in which the human being is involved. Yet Lacan felt he was free from any rule. His pessimism regarding freedom was therefore only one side of the medal; the reverse was a liberation that I would call in extremis, born precisely out of a sort of inaugural submission. We can compare it to Antigone—on whom he held some fine seminars—the heroine that rebels against the law of the city to follow her own law, that of her desire. Because Lacan’s transgressions went against the laws of Creon—from the International Psychoanalytical Association’s standard sessions to red lights—in order

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

to affirm another law, the law of desire. “We feel guilty,” he said, “when we give up on our desire.” He did not want to give up on his desire. “For him there were no small desires, the smallest longing was already enough for him,” Millot says (p.69), including the longings for the people he loved, longings that he had to satisfy immediately, without ever putting off to the next day what could be done right away. Significantly, as a young man he was friends with some of the surrealists, including Dalí, even if Millot prefers to call Lacan a “Dadaist.” Perhaps this is why he married the former wife of Georges Bataille, whom we can consider the ultimate libertarian philosopher. It is precisely when we theoretically deny human freedom, as Luther did (De Servo Arbitrio), that you must practice it in the most candidly desperate way. Lacan always wanted to enjoy everything: women, money, knowledge, thinking. In short, of Lacan we can by no means say he was wise—never mind the prejudice that says an analyst must be a champion of wisdom. Lacan expressed instead a remarkable vitality, an almost futurist passion for movement, sport, speed, travel. An almost childish vitality, which he himself acknowledged when he would say that he had the mental age of a five-year-old child. Ultimately, what distinguishes someone merely intelligent, even extremely intelligent, from a genius is indeed vitality and energy. Lacan didn’t need amphetamines, unlike Sartre, who would take heaps of them, to always be somewhat in high spirits. And, in fact, like Erik Porge, we could interpret the title of Millot’s book as With Lacan: Life. This vitality also expressed itself in the opposite of movement: Lacan spent long hours rapt, silent, motionless. This static void he created around himself at home, absorbed by his reflections, actually expresses the vitality of his thinking, which, whipped by the urgency of a perhaps impossible solution, would nail him down. A fast running for life, which, however, headed straight towards death, not towards the sense that each of us must die. After being diagnosed with bowel cancer, Lacan refused to follow a cure. And to his daughter who asked him why, he replied “No reason, just a whim.” The shadow of a quasi-suicide thus hovers over him, and the Stoics said that suicide is one of the few truly free actions a human being can allow himself. When you’re extremely vital, you do not fear death, and Millot insists on Lacan’s fearlessness. Once, during a supervision session, a burglar broke in and pointed his gun straight at him, demanding money, but he absolutely refused to give him anything. When faced with death, he didn’t run away from it.

Like a dandy, he paid the price of a fundamental loneliness. “There was never an ‘us’, there was just him, Lacan, and me following him… After all, if the word ‘us’ was never congenial to me, to Lacan it was absolutely alien… His profound loneliness, his apartism [feeling ‘apart’ from others] made the ‘us’ something inappropriate” (p.19). The “us” is that dimension of communion that, as we’ve seen, Lacan found lamentable about the Communion and Liberation movement. This is why he didn’t believe in Communism, and why those who practice group analysis are quite allergic to him. Freud had dealt with the dimension of the “us” in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921/1955), in which he describes every Mass, every collective, every “us,” as something essentially fascist. Because the unity of the “us” always presumes a Führer, a leader, a sort of alienation of desire in him. How then could Lacan found an almost-mass school of which he was the undisputed leader? The fact that he dissolved it shortly before his death tells us, however, that it had not been set up to exercise power on the masses. “With the exercise of power he had a relationship I would describe as minimalistic” (p.52). What was then Lacan’s Rosebud? I would say the very fact he told us that each singular existence—even his own—rotates around the mystery of a half-closed mouth presenting itself as extremely sweet. He was at once Kane with his hole and the journalist looking for him. The enigma Lacan represents for us is his way of going round and round the enigma that every human being is, even to him or herself. Ultimately, he has always indicated a fundamental hole that breaks the coherence of the subject-organism. A béance, a cleft, a gap, in psychoanalytical theory, of course, and also in his own theory, which, however, in turn expresses a fundamental gap in the human being. As Millot reminds us, he called the human being “the singular,” separating it from the particular and the individual. He sought a singularity with no sense with which we all have to confront ourselves. In physics, a singularity is every phenomenon by which the laws of normal physics cease to be valid, as in the case of black holes. Lacan believed that the bottom of every one of us is something “impossible” in which our laws are not valid and which he called the Real, a black hole that polarized him in his later years. At the time Lacan was completely absorbed, I would say harried, by Borromean knots. These consist of an undefined number of rings—at least three—interlaced in such a way that removing any one ring results in the others being unlinked: 11

DR2018_#18.indd 11

DIVISION | R E V I E W

Millot reminds us that the strings he used to create Borromean chains had at one point invaded both of Lacan’s houses. In his later seminars, he would limit himself to drawing on a blackboard more and more complex rings and knots, in silence; he had almost stopped talking. I shan’t discuss here the possible utility of Borromean knots in analytical theory and practice, but Lacan’s passion for them was certainly his jouissance and his symptom. Psychoanalytical theory needs to be psychoanalyzed too, along with the psychoanalyst who develops it. Lacan was apparently questioning himself: how to put together the fact that we manage to link aspects of our subjectivity, in such a way as to happily “close ourselves” to the cut, the breaking of the knot, which throws everything into the hubbub of freedom? In these knots, I can see an attempt to give an answer to a fundamental paradox, that of human existence, which psychoanalysis does nothing but retrace. Around this paradox, the vortex of Lacan’s way of living and thinking. This vortex makes him stodgy for many, precisely because we can never rest upon a definitive consistency of the theory. He had most of human knowledge rotate as an ensemble in this vortex, in a bulimia similar to Hegel’s speculative one: psychoanalysis and works of literature, mathematics and philosophy, logic, art, and linguistics. This cyclone rotated around an eye that he called the Real. This something missing from the jigsaw puzzle—and that which, in a way, dangerously frees us from any law— is something he confronted his entire life. z REFERENCES Freud, S. (1955). Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), Standard edition (Vol. 18, pp.65-134). London, England: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1921) Lacan, J. (1966). The direction of the treatment and the principles of its power. Écrits (Vol. II, p.77). Paris, France: Seuil. Lacan, J. (1978). Lacan in Italia/En Italie Lacan (pp.122127). Milan, Italy: La Salamandra. Millot, C. (2017). Vita con Lacan (R. Prezzo, Trans.) [Life with Lacan]. Milan, Italy: Raffaello Cortina. (Original work published 2016). Roudinesco, E. (1997). Jacques Lacan (B. Bray, Trans.). New York NY: Columbia University Press. Welles, O. (Producer and Director). (1941). Citizen Kane [Motion picture]. United States: RKO Radio Pictures.

SPRING 2015

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

HYSTERIA AND DIFFERENCE Hysteria Today As Patricia Gherovici (2017) has recently noted, the histories of psychoanalysis and hysteria are intimately connected. Both demonstrate that there is no natHysteria Today edited by Anouchka Grose Karnac (2016) and Routledge (2018). 198 pp., $25.95 ural object for the drive; both are testimony to the fact that there is no pre-given “normal” model of sexuality. The imperative to reiterate these two fundamentally Freudian principles is particularly urgent today, in an era of trans-gender/sexuality, in a time when psychoanalysis is more than ever being called upon to demonstrate its relevance. Hence, the urgency of attending to what hysteria might be, and what diverse forms hysteria might take, in today’s world. Anouchka Grose’s impressive collection of essays, published by Karnac under the imprint of London’s Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research, provides an instructive means of comparing varying definitions and descriptions of hysteria in contemporary clinical work. Grose’s opening chapter, which provides a wonderfully succinct overview of historical conceptualizations of hysteria, notes the opprobrium that has been targeted on the diagnostic notion of hysteria by feminism, before asserting that

Derek HOOK

forward in the form of accepted laws and norms. They use their dissatisfactions and discomforts as a means to interrogate the Other, to make it say something back… In this sense the hysteric can be seen as a seeker after truth. (p.xxix) Hysteria, notes Grose, had disappeared from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) by 1980, only to be replaced by the categories of “conversion disorder” and “histrionic personality disorder.” Leonardo Rodríguez takes up this argument, pointing to the hysterical phenomena that persist in the DSM under a diversity of headings: “Anxiety Disorders,” “Dissociate Disorders,” “Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders,” “Sexual Dysfunctions,” and so on. Rodríguez warns against the tendency to simply equate conversion symptoms with hysteria. Almost anyone is capable of developing a conversion symptom, he notes, going on to specify that We diagnose a patient as a hysteric of the conversion type if the conversion symptom is the dominant symptom, that is, if the conversion symptom…is what holds the patient together, providing neurotic stability and an unconscious form of personal identity. (pp.10-11)

It is, by contrast, forms of anxiety hysteria that are more likely to present at today’s clinic. As Rodríguez rightly notes, a great number of patients today “suffer from social inhibitions, incipient or ill-defined phobias, and episodes of anxiety with detrimental physiological concomitants” (p.15). Rodríguez goes on to set conversion symptoms apart from more generalized psychosomatic symptoms. Conversion symptoms, he points out, are metaphoric in nature; metaphoric substitutions are not present in psychosomatic symptoms, which, furthermore, “correspond to a direct, sealed link between unconscious conflicts and the affected organs” (p.16). A further distinction follows, between conversion symptoms and “pure” states of anxiety, which, as Rodríguez emphasizes, are still hysterical in the sense of being open to “becoming affected by the signifiers that the running of human life normally present[s] to the subject” (p.18). In each of these cases—hysteria manifesting in conversion symptoms, psychosomatic complaints, or varying forms of anxiety—the body remains the battlefield of subjective conflicts. In her account of the apparent disappearance of hysteria into new diagnostic categories (such as those of anorexia and borderline personality), Anne Worthington reminds us of Freud’s concerns, which in his early work on hysteria lay with

in the Lacanian clinic, a diagnosis of hysteria is anything but an affront. Dissatisfaction is the motor for desire, and desire drives existence. Hysterics specialise at using dissatisfaction to keep desire spinning, acting against atrophy and ossification. Far from trying to get them to stop fussing and get back in line, one might encourage them to take their questioning further, to use it in their lives and work, and even to attempt to enjoy it. (p.xxx) Hence, Lacan’s terminological choice in the 1970s, when he spoke about the need to “hystericize” neurotic analysands, stressing in this way the importance within clinical work of confronting incongruities and questioning what analysands claim to know about themselves and their history. So, Far from portraying hysterics as people who foolishly manufacture symptoms in a doomed attempt to buck the system, they are…seen [in Lacanian psychoanalysis] as people who refuse easy answers, resisting commonplace idiocies put 12

DR2018_#18.indd 12

DIVISION | R E V I E W

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

the reconstruction of…patients’ histories, which gave access to a knowledge about desire, a desire so strongly prohibited by the patients’ own desires about what was acceptable, whether socially or according to their ideas about who they were, that it has been repressed only to emerge in bodily symptoms. (p.36) The existential question that distinguishes hysteria from other neuroses may today be less “Am I man or a woman?” (Lacan’s favoured formulation) than “Am I straight or bisexual?” or even “Am I gay, or queer, or homosexual?” There are of course differing cultural contexts within which hysteria emerges. Worthington’s analysis of queer identity and politics as a site for “the articulation…of hysteria today” (p.49) provides a case in point; despite that, a series of crucial clinical continuities remains in place: Hysteria today, then, is perhaps not quite so different from the hysteria of yesterday: the somatic symptoms are messages, expressions of something repressed, questions addressed to the Other; it is associated with sex and sexuality, feminine sexuality; and the inherent bisexuality of the neurotic manifests itself in the hysteric’s speech, dreams, and identifications. (p.40) In a somewhat cryptic, yet nevertheless compelling, account, Vincent Dachy speaks of “the hysterical arrangement,” in which an effort is made “to keep and maintain the traumatic encounter with an enjoyment that poses the question of desiring within the realm of love” (p.57). The hysterical subject does not want to be desired as an object (for, as Dachy stresses, their body, their looks, their money, status, etc.), “but wants to be desired as and for ‘oneself ’…wants to be desired for the same reasons as those of being loved—but still wants to feel desired sexually” (p.57). The apparent structural impossibility of such a demand is nicely underlined by Dachy: “enjoyment, love and desire do not constitute a simple and automatic, ‘natural’ continuum!” (p.57). It is the hysteric’s attempt to use love as a means of containing the traumatic encounter with enjoyment that particularly fascinates Dachy: As the traumatic disruptive enjoyment is too much to deal with, love…is called

to make it passable. Love attenuates the shock of the traumatism, gives it a limit. By seeking the protection of the powers of love…desiring can be upheld as un-realised, and the re-encounter of the problematic enjoyment kept at bay. (p.57) Part of what is compelling about this account is that it foregrounds how a traditionally masculine dilemma—how to both love and enjoy the sexual object—is also fundamentally hysterical. Darian Leader continues the study of careful diagnostic distinctions apparent in Rodríguez’s chapter by insisting not on the content of clinical symptoms, but on the place they occupy for their sufferers, and by drawing attention to what they give voice to. Any number of culturally available symptom types might be utilized as a means of articulating the hysteric’s discontent. Contrary to how the term is often invoked, there can be no cross-cultural or trans-historical definition of hysteria: Hysteria by definition is constantly updating its symptom pictures. Presenting symptoms will change with culture…A robust diagnosis will be predicated not on surface symptomology but on how the subject speaks about their symptom, the position it occupies, and what we can learn about its construction. (p.28) Leader’s chapter is concerned with three particular areas where diagnoses of hysteria and psychosis are sometimes confused, namely questions concerning Other minds, the Other woman, and the Other body. The psychotic subject, like the hysteric, may spend much of their life in the unbearable situation of not knowing who they are for the Other. This puzzle of Other minds can often be separated in its psychotic from its hysterical in the following terms: What seems on the surface to be a… stoking the desire of the Other, of creating…unsatisfied desires…turns out [for the psychotic] to be a way of creating… distance. …The Other must be kept at an artificial distance which the subject has created. …for the hysteric, such refusals serve to perpetuate the question of their value for the Other-…The relation to the Other here aims at a point of desire, of lack, which the subject identifies with. (pp.29-30) The hysteric’s identification with the lack, furthermore, is generally situated in the father. The role of paternity thus makes for a useful differential diagnostic feature in hysteria and psychosis. Whereas the Name-of-the-Father 13

DR2018_#18.indd 13

DIVISION | R E V I E W

is famously foreclosed for Lacan in the structure of psychosis, something about the father does not work here; the trace of the father and the lacking father are typically operative in hysteria. Leader’s conclusion makes for an important consideration in any differential diagnosis of hysteria: The hysteric is not the only subject allowed to pose a question about their sexual identity, just as the hysteric is not the only one with a sensitivity to the desire of the Other or a claim to use the body as a space for conversion. It is less the presence of these motifs that truly characterizes hysteria than the nature of the space in which they are elaborated. (p.33) If the medium of this space is lack, Leader continues—opting here for a topological formulation—and if this lack is one within which elements of identification are operating, “we are probably with hysteria” (p.33). Hysteria Today has obviously been prepared as a text primarily for clinicians, and its focus on differential issues is certainly one of its strengths. It would have been useful, perhaps, if more on Lacan’s later theory of the four discourses might have been introduced, thus opening up a link to social and political theory. This being said, Colette Soler’s contribution to the volume does usefully foreground a series of Lacanian formulations regarding hysteria that connect his early to his later work: Clinically speaking, the key phenomenon of hysteria is…a systematic lack of satisfaction, that is, a lack that is cultivated. …This has given rise to a series of different interpretations: first it was the manifestation of a desire to desire, then it was necessary to keep jouissance unsatisfied so that desire can be sustained. But any desire is always linked to a modality of jouissance. (pp.91-92) Particularly helpful here is how Soler reformulates the idea of a hysterical desire for an unsatisfied desire in terms of the later Lacan’s attention to jouissance. There are a series of motifs—signatures of jouissance, as we might put it—that point us to how hysteria is most likely to manifest today: the jouissance of being deprived; the idea of “the body on strike,” and “identification with the jouissance of the castrated master” (Soler, pp.91-92). Bearing these clinical indications in mind gives one little doubt about the persistence of hysteria in today’s world. z REFERENCES Gherovici, P. (2017). Transgender psychoanalysis: A Lacanian perspective on sexual difference. Abingdon, UK and New York, NY: Routledge.

FALL 2018

10/10/18 2:13 PM

BOOK REVIEWS

Transgender Psychoanalysis: A Lacanian Perspective on Sexual Difference It is unfortunate that much of institutionalized clinical psychoanalysis, particularly perhaps in the more medicalized US context, has lent itself to a patholoTransgender Psychoanalysis: A Lacanian Perspective on Sexual Difference By Patricia Gherovici. Routledge, 198pp., $52.95, 2017 gization of “non-normative” or so-called “deviant” sexualities. Patricia Gherovici’s distinctive political and Lacanian engagement with what is perhaps the most urgent debate in psychoanalysis today—that of sex/gender change, as brought to the fore by the trans movement—does not shy away from this lamentable history. It is something of an irony that a mode of clinical and theoretical practice developed on the basis of Freud’s texts (inclusive of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, 1905/1953) should be either somewhat detached from, or worse yet, pathologizing of, “minority” sexualities. As Gherovici shows, Freud himself was far keener to collaborate with experts of sexology in the development of psychoanalysis than were many of his colleagues, and he certainly demurred from the homophobia that many later psychoanalytic institutions sadly came to exemplify. The polymorphous perversity that Freud posits as underlying sexuality itself, along with his suggestion, echoed and amplified by Lacan, that drive is by definition skewed, deviant, “non-normative” (even, might we say: “queer”), should mean that the concept of sexual abnormality has no place in psychoanalysis. We could take this argument further: in having gravitated towards the conservative, particularly with respect to current debates on trans identity, psychoanalysis has—in effect—ceased to be psychoanalysis at all, at least in the sense of being a discipline attuned to the non-normative and unconscious dimensions of sexuality. It is for this reason that Gherovici argues that psychoanalysis needs a sex change, and that current developments in the trans movement best enable such a revision. Humorously, she asks: “Could it be that today’s psychoanalysts are no longer as afraid of Lacan as they were yesterday? Are they not more afraid of sexual and gender non-conformity?” (p.2). If Freud’s non-normalizing theory of sexuality is in any doubt, let us refer back to Freud’s thoughts on sex as related to the drive, as so articulately described by Gherovici:

Freud separates sexuality from the destiny of genitality, from the destiny of gender, and even from the destiny of reproduction. …Freud had further elaborated on the sexual drive as not determined by gender…in Freud’s thinking the drive has only one object—the aim of the drive is satisfaction, a satisfaction that even when obtained is never complete. The drive, a tireless power, unlike other biological functions, knows no rhythm… The drive carries along a non-representable sexuality in the unconscious. The drive is neither a biological force nor a purely cultural construction. (p.165) What this means then is that “sexuation”—how one identifies and, as importantly, how one desires as a sexual being—cannot be reduced to questions of either biological sex or sociological gender. For psychoanalysis, as Gherovici puts it in a succinct formulation, “sexual difference is neither sex nor gender because gender needs to be embodied and sex needs to be symbolized” (p.165). Moreover, “The problem that one finds in the clinical practice,” says Gherovici, “is always of the order of the Real…of the unassimilable aspect of sexuality” (p.165). Sexuality, viewed from a Lacanian perspective, is invariably a failed or incomplete project, a function of modalities of jouissance that are never completely domesticated or harmonized with that of another subject. Hence Lacan’s famous rhetorical insistence that “there is no such thing as a sexual relationship.” Or, put in a more straightforward way, sexuality for Freud exceeds sexual practices and sexual identity and is hence inherently problematic. Why? Because it is disruptive of identity, or as Gherovici puts it, paraphrasing Leo Bersani: “sexual pleasure occurs when a certain threshold of intensity is traversed, when the organization of self is…disturbed by sensation” (p.38). The notion of jouissance is crucial to grasping the radically de-natured form of human sexuality; jouissance connotes “a violent, climactic bliss closer to loss, death, fragmentation, and the disruptive rapture experienced when transgressing limits” (p.63). Given then the de-essentialized, “real,” and disruptive nature of sexuality as a type of constitutive incommensurability, how should we define trans? Gherovici provides a helpful and necessarily inclusive description: “Trans” is an umbrella term that applies to genderqueer people, to male-tofemale and female-to-male transsexuals, to gender non-conforming folk, to drag queens and drag kings, to cross-dressers, to a large range of people who do not identify with the sex assigned on their birth certificate. (p.3) 14

DR2018_#18.indd 14

DIVISION | R E V I E W