17 minute read

1.5 Conceptual Framework 101.5 Conceptual Framework 10

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

As discussed in the previous chapters, the project’s goal is to shape the transition from a linear to circular economy in the construction and demolition sector. It also addresses the demands on urban cores and the plethora of landscapes that need to be regenerated. In this chapter the conceptual foundation of this transition is explained. The foundation is mainly based on the following theories.

Advertisement

Transitional landscapes, New developmental models, Knowledge distribution, Re-envisioning construction practices. In the course of our research, we found that studies have shown high and diverse demands on land in South Holland. The agricultural sector still remains the main land user in South Holland, occupying over half of the province’s surface area as of 2015 (Clo.nl,2012). Built-up areas along with housing infrastructure take up only about 20 percent of the overall land. These urban areas, especially in Randstad, are very dense due to the prevailing spatial planning policies of the Netherlands (Ministry of Housing and Physical Planning 1966) which we will depict in detail in the next section.

“Land is considered a finite source” which can’t be extended beyond a limit (Amenta & van Timmeren, 2018; European Commission, 2020). The criticality of land depends on the limit to which it can be exploited before it stops acting as an important resource (Kasperson et al., 1995: 25). To use the land to its full potential and bring it under the umbrella of circularity, it needs to be treated as a renewable resource (Marin, 2018).

The landscapes of South Holland share an inherent relationship with human activities (Pols et al., 2005). The dutch landscapes are treated as cultural landscapes and the land is given the utmost importance historically in dutch context (PBL, 2019). Land reclamation, urbanisation and industrialisation have been major contributors to the identity of the South Holland landscapes today. These landscapes have in turn influenced the resilience of the social groups and communities dependent on them (W.Adger, 2000).

Today’s linear economy witnesses major transitions of land from extraction, reclamation, conversion, development, contamination (especially in the case of industrial activity), usage and finally abandonment. The resultant landscapes take the longest to heal after undergoing these developments. Ergo, these wastescapes left behind by diverse human interventions are unusable and need to be regulated for efficient revival and reuse.

Wastescapes are wasted landscapes or unused land parcels which are usually a result of human activity, industrial activity or spatial development strategies. The industrialisation of older city areas and the rapid urbanisation of newer city areas could be identified as two primary processes for the formation of dross scapes ( Berger, 2006). Brownfields are the results of the process of industrial change, especially in Urban areas (Grimski, & Ferber, 2001).

Research suggests that there are over 93800 hectares of industrial lands and Brownfields across the Netherlands. In this new transitioning economy that iaccounts for 30% of areas that are obsolete and eligible for redevelopment. This is more than 30,000 ha of industrial land alone which is wasted as of now (PBL, 2019). These industrial areas are well-connected and in the vicinity of city centres because logistics and accessibility were the main focuses for their initial establishment. These factors give them a competitive edge over greenfield development.

Waste scapes provide opportunities for sustainable urban and territorial regeneration. It includes a regenerative system which provides continuous replacement through its functional processes of energy and materials used in its operations (Van Timmeren, 2006). Revitalising wastescapes is a complex discipline and it requires diverse fields of focus making it multidisciplinary. It brings together different concepts related to economy, quality of life, health, accessibility, resources, landscape, environment and infrastructure (Van Timmeren, 2019). Since this is inherently a complex process, it is not just achieved by a single party but requires a collaborative

effort of multiple processes, flows and actors. It requires a systems thinking which allows one to utilise a holistic and transdisciplinary approach across multiple scales and sectors (Cloy, 2019).

In our proposal, the plugins will not consume unused pristine lands or green fields. This will prove inefficient and result in more depletion of natural resources. Hence, we will examine the potentials of different types of abandoned landscapes that are left behind due to planning initiatives, transformation stages or industrial activities. The development of these wastescapes, instead of new agricultural fields, has multiple economic, ecological and logistical advantages. Circular management of land aims to reduce the land resource required for new building constructions, transportation facilities, working and residential areas. It proposes densification through remediating abandoned landscapes, recycling and introducing mixed typology buildings for efficiency, economic productivity and flexibility of built land (Preuß & Verbücheln, 2013).

Land can be considered a ‘common good’. Common goods are defined as goods that are rivalrous and non-excludable (Lefebvre et al., 2015). Commons are those resources that are held in common (Rocco, 2020). These include resources held by few communities, like agricultural land owned by farmers and industrial land by shipping industries and other actors as such ( Zuid-Holland Circular). In recent developments, the land has been privatised and is controlled by only a few actors owing to the global economy and market (PBL, 2017).

The tragedy of the commons is a situation in a shared-resource system where individual users, acting independently according to their self-interest, behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting or spoiling the shared resource through their collective action. (Hardin, 1968). We also had to differentiate between the common goods from the common pool resources. Unlike the common pool resources (CPRs), which work like an open-access regime with no particular resource management system, Commons are guided and negotiated by the people. We are proposing a more informal structure to manage these shared resources.

The usage of land by an individual actor under the policies of the province essentially means that it is rivalrous and not accessible to others during the time of use. Hence, the transitional periods of these landscapes become very crucial for our proposal. Our vision strongly emphasises that landscapes which are under transition would be given back to a shared-resource system where after debate and collaboration, all stakeholders of the community can decide how the land can be used to create equal opportunities of knowledge sharing and just living conditions.

The Dutch landscapes are of important public interest and belong to everyone (PBL, 2019). The viability of these landscapes during the course of remediation and revitalisation are very important for the whole society (Baldock, Hart and Scheele, 2011). These transitional landscapes are full of potential to address key values of the society, and the problems we face today like climate change, social vulnerability etc. It is very important to make them accessible for diverse uses and to distribute the gains of those uses fairly. This would increase the efficiency of land usage and collective action that would result in the common good.

The Post-Industrial city, developed in Europe in the latter half of the 20th century, caused major social, economic and ecological changes. Cities became the main attractors for livelihoods in the process. The rapid and large scale urbanisation has taken its toll on the movement patterns, environment and social behaviour (Banister,1997; Williams et al., 2000; Marshall, 2001).

South Holland is a highly urbanised Province (PBL, 2017). Most of the jobs are found in the cities and they have the highest share of knowledge workers and also attract the most foreign immigrants. The main pull factors are the proximity of amenities, job opportunities and the proximity of educational centres (Vissers, 2019). The high population density and concentration of human activity in cities are causing climate change, increasing urban heat island effect, air pollution and waste (PBL, 2017). The everexpanding urban boundaries have become highly dependent on their city centres for functioning. On a city scale, these over-dependencies have led to weaker sections being pushed away from the urban centre and from the advantages and opportunities it holds.

In South Holland, Hague and Rotterdam act as the two main economic pillars (OECD, 2007). The Metropolitan region of Rotterdam-The Hague acts as a monocentric system of the whole province which contains multiple satellite towns and suburbs that are over-dependent on them. On a regional scale, a great majority of the economic activity is dependent on this area, which leaves the whole region vulnerable to potential risks.

The current growth of South Holland is greater than in the past. Research shows that there will be a need for an additional 250,000 houses in the province south Island by the year 2050 (Zuid-Holland Circular, 2019). The municipality vision proposes that 83% of these houses be built within the urban borders adding additional pressure to the already strained cities (Clo.nl, 2017). This methodology is based on the compact organisation policies in the Netherlands (Geurs,K; Wee,B., 2006). To protect the natural ecological systems, curb suburban sprawl and protect the fragility of the peri urban areas, national spatial planning policies were aimed towards implementing compact urbanisation in various forms.

One of the approaches adopted for channelling suburbanisation is to implement "concentrated deconcentration" which aims to accommodate new urban growth outside of existing urban areas in several designated spillover centres (Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and the Environment, 1977). This policy was embraced as a feasible compromise between concentration and low-density dispersal of urban activities.

However, due to the decline of the inner cities, this was further replaced by the ‘compact city’ model. From the late 1990’s, there is a call to relax strong emphasis on compact urban form after the housing stock and the number of inhabitants in the large cities started to grow again after a decade of serious decline (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 1999). These discussions gave way to the replacement of the compact urban development by a ‘Network city’. Network city is a planning concept that would lead to decentralisation and reduced local governance.

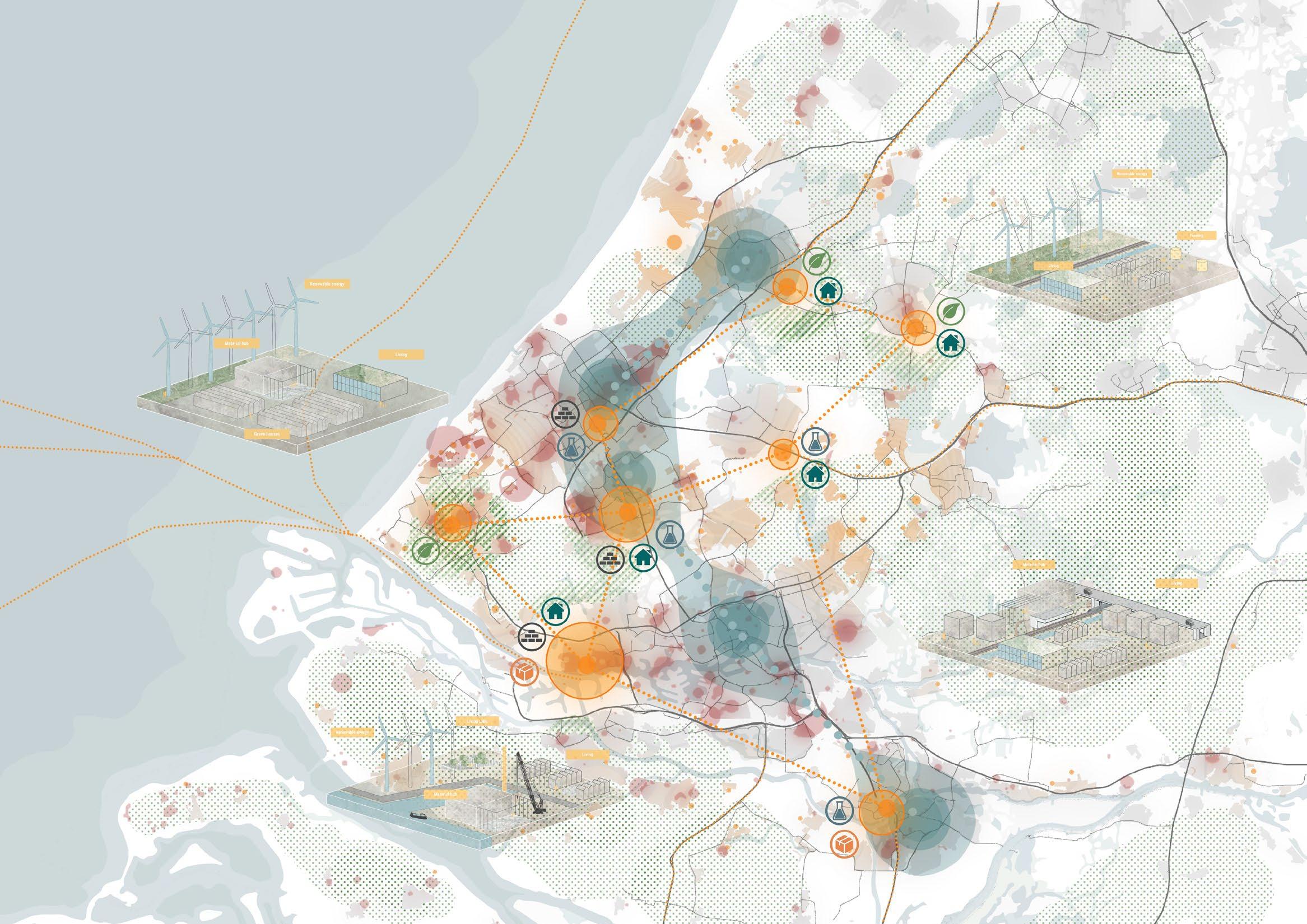

We have proposed a similar model for our densification strategies. A synergetic regional development model aims at reducing the over-reliance on a single metropolitan area and strengthens the region as a whole. In this new configuration, all the cities and smaller towns would merge in terms of disciplines and act as a single coherent robust region (Meijers and Romein, 2003). This synergetic, polycentric model strengthens the relationships and the connections between the region’s different cities. It creates specialised and complementary urban centres that vary in size, function and identity but work as one system, avoiding a destructive large scale urban sprawl (Beily and Turok, 2001). A polycentric system that functions with diverse and complementary urban areas can achieve a steadier pattern of development and greater spatial justice (European Commission, 1999).

These new development areas are proposed at the peripheries of the existing urban cores at the threshold of the urban fabric and open landscape. These maintain the fragility and the cultural significance of the peri urban areas which are considered the main bridges of the divided worlds of rural and urban (Wandl, et al.2014). In our proposal, the plugins that are created near these multiscalar regions would use the local potentials and promote more local economies that would then be interlinked with a robust infrastructural system that is already in place.

This reduces the pressure on the major urban centres to support the transition towards a just and circular development. The economy is diversified and each area supports the other under the systems theory and creates better conditions to address the fundamental uncertainties of this shift.

To put circular economy concepts into practice, citizens, their awareness, mindsets and behaviors play an essential role (Veleva, Bodkin, & Todorova, 2017). This awareness will be brought in only by equal cognition. Central to our vision for South Holland is the assimilation and dispersion of knowledge. There was a keen interest to understand whether knowledge can be perceived as a public good.

The technical definition that was pinned down by Elinor Ostrom in her book, Governing the Commons, divides economic goods and units of exchange, on two axes. Public goods are non-rivalrous and non-excludable (Rocco,2020). Knowledge is infinite and doesn’t reduce when someone consumes it and once given can’t be taken away. However, the main issue with characterising knowledge as a public good was that it is not free at the point of delivery. It is an excludable entity. Knowledge is highly privatised in the capitalist economy (Hirschman, 1977). Natural incentives exist to create private goods as accumulation seems to be the natural aspect of human character (Hirschman, 1977).

'Knowledge Commons', a concept which is half socialist utopian and half neoliberal is a belief that technology can enable the effective sharing of knowledge as a resource. The resources that can be shared and explored by all would then act as effective foundations for value creation (Hess & Ostrom, 2006). So to determine and drive knowledge as a public good, we needed to ascertain different forms of provision.

Dispersion of knowledge and its just sharing requires the same tools that would support the creation of public goods. Especially, for an entire paradigm shift, these mandates and legislatures are of utmost importance.

The current model of knowledge concentration needs to be diminished because it results in the accumulation of this resource in the hands of a few actors who would, in turn, control the extent of its impact. Distribution of knowledge creates greater benefits and enables the creation of even great value. Since the province's future vision looks at a drastic shift that needs knowledge build-up and innovations, there is a need to establish new networks of knowledge dispersions. These public goods need to be resourced at a global level and mandated through legislation.

A shift in the economy and ensuring that this shift would be sustainable, a transition in perspectives is needed (Hobson & Lynch, 2016). Changing the mindset and driving the knowledge about circularity is a multi-scalar and multi-systems approach. Hence, at a policy level, we propose a collaboration between the top-down and bottom-up disciplines so there is a shift in the economy in every household from being passive consumers to more proactive prosumers. The greatest hindrance to achieving this is the lack of knowledge and its distribution (North & Nurse, 2014). It is inaccessible to a whole section of the population to realise this. Our proposal forms an initial seed for an integrated systems approach that connects flows of biocentric and service/ knowledge-centric industries.

To engage all the citizens in this circular economy, the new developments should be organized in a way where opportunities for participation and engagement are maximised and a sustainable lifestyle becomes more obvious and easier to achieve (North & Nurse, 2014). For this, self builders need to be encouraged, localised business, social enterprises, small entrepreneurs and local material production and distribution services and community based institutions would have to be supported both informally and also on an administrative level (North & Nurse, 2014). Local economies and new community-based business models would inspire confidence of the citizens more easily and guide them to take an active part in creating the circle (Hobson & Lynch, 2016). Localising the logistics and supply chains would also transform the transportation means and as a result, emissions can be reduced. Localised economies do not mean independent actors, they still rely on each other and the overall region to develop synergies. They bring forward strong and integrated regions that complement each other in terms of functionality and identity and the local economies engage citizens to participate (North & Nurse, 2014).

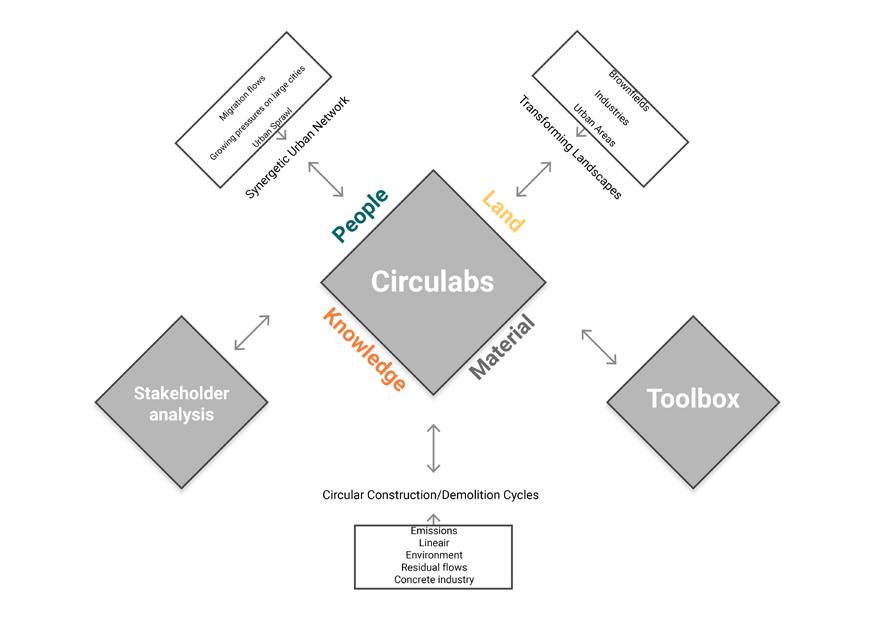

Figure 2.2| Multifacated nature of Circulabs; Illustrated by authors

RE-ENVISIONING CONSTRUCTION PRACTICES.

The construction industry in the province of South Holland uses up to 5.6 Mton of building materials (Zuid Holland Circular, 2017). It contributes to the largest flow of materials within the region. Even though it boasts of recycling 85% of the building materials after demolition, the vast majority are not reused or used only for their second-grade value (Metabolic, 2019). The province has ambitions to transform the region into a circular economy by 2050.

Policies in the region already recognise that the construction sector needs immediate mitigation efforts that aim to tackle greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, protect natural and renewable resources and transform into a circular economy (Hodge et al., 2010; Sieffert et al., 2014). A circular economy can be described as a model of development where the end-of-life waste concept is replaced by generating alternate uses for recovering materials, by recycling, revitalising and reusing them. These materials undergo various transformations due to production, utilisation, distribution and consumption processes (Kirchherr et al., 2017).

The new model emphasises the necessity of maintaining the products and materials in the flow so that the dependence of new and virgin resources can be diminished which are usually accompanied by negative environmental impact (Mirata, 2004). The concept of circularity has recently garnered attention as a means for policymakers to respond to sustainability issues (Veleva, Bodkin, & Todorova, 2017) (North & Nurse, 2014) (Hobson & Lynch, 2016). However, in many critical conclusions, this refers to a zero-waste model, in which as much waste as possible would be turned into a reusable resource material (Veleva, Bodkin, & Todorova, 2017).

However, it now becomes very important to understand the shortcomings of a circular economy before transitioning into it fully. In a growth-based economy like south holland, this model doesn't respond to the fundamental problem of overconsumption (Hobson & Lynch, 2016). The only way this can be addressed is if the objectives include zero waste as well as making a robust reusable material bank to establish a zero consumption of new resources.

Effective and comprehensive collaborations between scientists, policymakers, government ministers and companies must be established. The focus should be on expanding the scale and the quality of construction and demolition recycling and its potential to also be reused to construct new buildings which are energy efficient. Although, circular construction is not only about resource recovery, re-use and recycling, is a much broader concept (Ghaffar, Burman & Braimah, 2019).

The stakeholders in the construction sector lack proper incentives to innovate in terms of dismantling strategies and material recovery, since the market hasn't incentivised them yet. The onus then falls on the government to issue mandates to meet the recycling targets and provide reasons for them to invest (Ghaffar, Burman & Braimah, 2019). It becomes quite complex since new legislations are required and not the general appreciation for global challenges and environmental concerns (Dahlbo et al., 2015; Kurdve et al., 2015).

KNOWLEDGE AS A PUBLIC GOOD

EQUAL ACCESS STIMULATION OF SYSTEMS

RELATION BETWEEN PEOPLE AND LANDSCAPE

NEW GROWTH MODEL

COLLECTIVE SYNERGIES

CLEANER CONSTRUCTION AND DEMOLITION SECTOR

CONSUMER TO PROSUMER

Figure 2.3

CONCLUSIONS

The conceptual framework has been guided by the different theories which were discussed in the earlier sections. The fair sharing of knowledge ideology has put the focus on the notion of whether knowledge can be considered a public good. This is especially important for the transition of the current linear economy into a circular economy. It also addresses the inherent relation between knowledge and development of the current socialtechnical systems of construction practices.

Also, the notion that land is considered a common good is strongly intertwined with socio-spatial justice for large segments of weaker and marginalised parts of the society. Since the land is a finite source, it is important to aspire for its fair distribution and access. The transitional landscapes of South Holland should be taken into consideration for their regeneration and reuse. Then the expectations of these landscapes along with the other abandoned landscapes and waste scapes should be equally distributed. Along with the prosperity of developers and construction industries, the well-being of the citizens needs to be considered. Even though the land itself is owned by a few, it would still cater to people, planet and prosperity.

The role of the strategy is to guide, stimulate and educate so that the transition from a linear to a circular economy can happen with a fair distribution of resources and knowledge. The inherent relation between the development of a society and their dependence on landscapes are also reflected in our proposal. The transformative landscapes can revitalise their support systems and also be extremely valuable to the societies that are dependent on them. The transition of these landscapes will happen simultaneously with the fair dissemination of knowledge regarding the new methods of achieving circularity in the construction and demolition sector particularly.

16