57 minute read

Rice

The culture of a seed

The laundry rocks by the river are dry this morning. It is rice planting day.

Coughing clouds and mist-hued hills find six women gathered at a concrete bench facing the hamlet's sacred Bodhi or bo tree. The word bodhi means "enlightenment." It also means a species of pipal or ficus under which the future Buddha once meditated on the night he achieved Enlightenment and the path out of the brambled thickets of ignorance and doubt. The hamlet’s bo tree was planted from a cutting taken from ancient Lanka’s Sri Maha Bodhi, itself grown from a cutting of the original Buddha’s Enlightenment Tree. The women carry fire-blackened chattie pots for cooking, wicker hampers filled with food, and bundles of laundry they had washed the night before. Since it is bad luck to leave laundry to dry out of view where it might inspire thoughts of thievery, the women will drape the garments over nearby bushes when the sun emerges from its foggy dawn.

The misty sky is a bad omen — rice loves sun and the best omen for a good harvest is being planted on a hot day. A gloomy planting day forewarns a poor harvest.

A new mother carries her baby on her back. She carries a large bottle of water and her lunch wrapped in brown paper tied with string. The others range from flowers trudging out their time to a withered face murmuring its creases. There would have been seven of them today, but one felt her period begin the night before, and blood — from the woman in the pain of her flow or from a man in the heat of anger — must never spill onto a paddy.

The oldest woman in the hamlet stays at home during planting time now; in her wake many years have begotten their days. She plucks supper's kari leaves from their stems, one by one, and gently nudges at the hammock in which the newest-born sleeps.

The women compare the omens. A cold sun at dawn is a bad portent, but now they add other malefics to the list. One woman heard a gecko chirp during the night — always a bad sign before starting a journey or new venture.

Another woman whispers of a dream she had in the dark of night. She felt a handsome prince slip into her bed and fondle her thighs, but when she awoke with a start only her husband was there, drunk and snoring as usual.

"Kalukumara!" they nod gravely as she describes the warmth she felt in her thighs where the invisible spirit in the dream had just lain. "Black Kumar. He was left unsatisfied because you awoke. He is taking revenging by plaguing us with the clouds in the sky today."

Kalukumara is a seducer spirit whose khamma* is to turn friends into enemies. Today those friends-turned-enemies are the paddy and the sun — a sign which could hardly be worse as they bemoan the omen of a cold dawn. And another bad sign: squalling black birds chasing each other through the coconut and rubber-tree groves. And if there are parrots on the telephone wires, the woman whisper, that will be the most dreadful sign of all, for parrots are grain thieves even greedier than crows.

They are silent for a time, weighing these signs. Around them the gama or hamlet is getting on with its day, although with less concern about the state of the sky. Paddy life is not gama life. In gama life there is margin for error. Not so in paddy life. In the gama a bad day is only one of many days. In the paddy the malefic of a bad planting day carries all the way through to the harvest.

The women are startled by an eruption of grackle-like sounds as two Bajaj tri-wheelers angrily blare their klaxons in a traffic jam. An oxcart has stopped on the hamlet's one-lane road while its driver picks up a load of kitchen firewood stacked in a latticework square by a woodcutter. One by one he threads the sticks into the back of the cart to parallel the rest of his load, oblivious to the impatience of the tri-wheeler drivers, whose furiously burping klaxons escalate to what sounds like a propaganda war between two ponds of frogs.

This the women take as a good sign which balances in part the bad signs of the sky, the gecko, and the birds. For the life of the gama is second only to that of the paddies. That young people are hiring Bajaj tuk-tuks to their jobs making seats for school buses in the village a kilometer away is good, for those job holders had been unemployed for years. Educated but unemployable youth has been a problem ever since the British lodged in people’s minds the notion that the only worthy work was working for a government. Ever since, schools have been graduating municipal administrators in numbers far in excess of the positions ever likely to become available.

To the good sign of young people with jobs, the women add the good omen of seeing full bowls of milk before leaving their homes — for which, be it known, they had assured themselves the night before by generously overfilling their cats' milk saucers. The grateful cats may not know anything about planting-time omens, but they do know a bountiful bowl as they lap it up.

Thus the bounty charm: As bounty is provided to the cats at planting time, bounty will be provided to the gama upon harvest. For the same reason many farmers plant a go dane field with corn for the exclusive enjoyment of their cattle. Nor are cattle shu-shued away from rice grains in the cracks on the threshing floor, for the more bountifully they graze today the more bountiful will be the harvest a hundred days from now.

The women discuss other good planting omens — a gentle breeze, full jars in the gama's boutiques (a matter attended to by any boutique owner who desires further business that season), trays filled with ripe mangos (no one will sell or consume a mango until the planters leave the gama for their fields), and fully opened white blossoms. The women nod with approval that the police have made sure no beggars entered town overnight, because on the long list of bad planting omens, beggars and parrots share equal status as the worst.

There are good omens for many ventures — favorable stars for marriages, seeing a peacock before making love, hearing a woman sing a sweet song as a young man musters the courage to open the envelope of photos of a woman chosen by his parents to be his bride. Seeing yellow parasols before examinations. The trumpet of an elephant before childbirth. All these are very well and good, but they are not the planting-day omens whose malefics are presently being compared by the women.

To propitiate the day’s bad omens, the women have come to the bo tree to meet with the bhikkhu, the Buddhist monk in charge of this particular tree’s Bodhi Puja, the daily meditations whilst grooming the tree’s grounds. The bhikkhu will chant pirit prayers to assure a successful planting. A good planting is a simple planting, and that requires the elimination of omens, which in turn requires the bhikkhu to chant the pirit of planting day prayers.

Rice achieves perfection by way of its simplicity. Its stem is slender and tough and thrifty. It has eliminated petals, nectar, scent, color. It has no need of bees or butterflies. For thousands of years the simplicity associated with rice has never been altered. It has always been planted the same way, harvested the same way, cooked and eaten the same way, with the fingers on one hand. To make certain that this shall always be, there is a pirit for plowing, a pirit for planting, a pirit for harvesting, a pirit for winnowing, and a pirit for cooking. That is why the bhikkhu is as central to society today as he was twenty-two hundred years ago.

During the time of the great king Dutthugemunu a century and a half before Jesus, the fact became clear that someone must feed and house the thousands of monks who were withdrawing from the world into monasteries and hermitages to devote themselves to learning and teaching the dhamma (Sinhala rendering of dharma), the four great truths of the Buddha. The dhamma was the spiritual thread that united the kingdom, from king to beggar, from novice samanera to aged mahathera, from the century in which the great emperor Asoka of India dispatched his son Mahinda to preach the dhamma to the dark-skinned curly-aired yakhsa arborists of far Lanka, to the century we live in today.

The Sangha, the order of Buddhist monks, first learned and then taught the dhamma. Verbal piety was converted into visual piety in the form of countless whitewashed round-domed dagobas in front of vihara spiritual gathering places and pansala monks’ personal quarters.

Only a king could fill so many begging bowls, but who would fill the king’s bowl? Dutthugemunu turned to the support of those who would do the providing, the cultivators. Monks needed kings, kings needed cultivators, and cultivators needed water. Thus originated the water-based civilization of ancient Lanka, and the rice culture that nourished it.

Small reservoirs and sluiceways had long been built by villages for their own needs. But the dozen-acre reservoirs whose waters supplied the gama where the women wait today could never supply an ancient city like Anuradhapura, filled with monasteries and palaces and the thousands of artisans and merchants who made it the core of ancient Lanka’s civilization.

Hence kings like Dutthugemunu devised a social order founded in principle on religion, royalty, and economy; but in fact upon a small grain called rice, and the water that grew it.

As cultivators were the foundation of the entire social structure, they were given the proudest of castes — govi-vangsa as it was spelled then, which is rendered govigama, govinda, or simply govi today. Look in any of the newspaper advertisements for brides or grooms and you will see the qualification govinda given greater pride of place than nearly any other qualification except a glowing horoscope.

At one time each term had a slightly different meaning, distinguishing owner-cultivator from non-owning cultivator from tenant. Today those details have dwindled in importance. Govinda is common currency in a basket of social history coined by many mints.

As govi-vangsas were proud of their place, they worked to keep that pride. Knowing the kings' duty was to provide prosperity for all and that prosperity flowed from the kingdom's waters, the govivangsas accepted that their duty was to relinquish their surplus beyond their family and seed rice needs, to the king. Over time the surplus came to be considered one-sixth of the harvest.

The kings in turn used this surplus to feed the populace. In time, royalty, Sangha, and commoners all prospered from the king's granaries. What was left over went into the treasury. Rice cultivators were so productive that the kingdom was not only well fed but accumulated a surplus so large that ancient Lanka was known as the “granary of South Asia.”*

* Today’s Sri Lanka has enjoyed (some say endured) more names than most locations in the world

— Serendib (of the Three Princes fame); Tambapane by the preBuddhist conquistadores led by Vijaya; Jambudvipa (“island”) in Asokan Buddhist times; Taprobane to Roman traders; Zeylan to the Portuguese; Zeilan to the Dutch; Ceylon to the British; and Lanka (“The Isle”) to everyone who lives there today. The official name, Sri Lanka, means "Resplendent Isle" and amply earns its reputation, as any visitor will attest.

All these citizens being fed and housed owed an obligation to the king who fed them. Their repayment was the King's Labor, Rajakariya. Although coinage existed, it was a medium mainly of interest to merchants and itinerant purveyors. Self-reliant cultivators seldom needed it. What they did need was food, housing, and acknowledgment of social worth. This wasn't an economic system as much as a commonwealth, and from it grew great palaces, vast monasteries, a ceaseless construction of water-storing reservoirs that reached hundreds of times the size of the homebuilt gama tanks, networks of irrigation civilization across 2,400 years and 123 kings uniting the govi-vangsas of Dutthugemunu to the six govinda women now waiting for the bhikkhu.

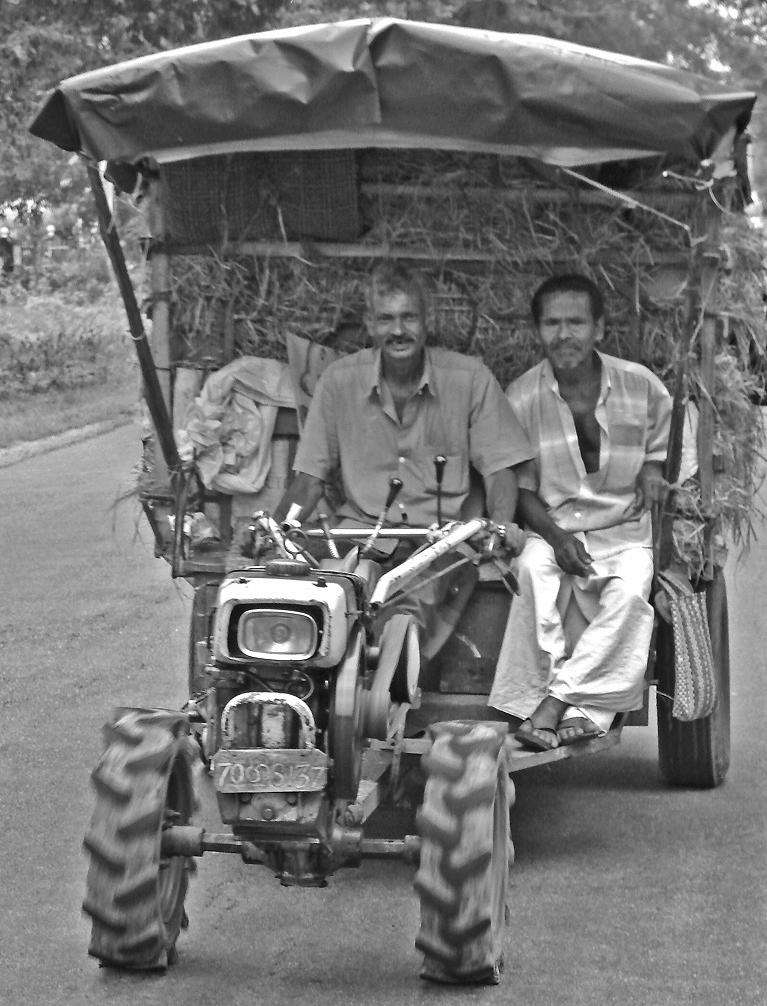

Surrounding the women are reflections off the facets of the necklace of life founded upon rice — mud-daub and woven stick walls, tin roofs, brick-lined wells with wood-beam posterns, concrete house cisterns raised on stilts, bissa granary walls of roughcut wood with untrimmed edges, irregular lengths of roof timbers lopped at the ends with an adze, curlicue shavings from a spokeshaved cartwheel repair, red tile roofs torn loose by monkeys in their incessant fights, garden plots bordered with coconut husks, advertising banners in Sinhala's frothy script, the HiGrip Tyre House (one-cylinder, two-wheel, handlebar-steered tractors a specialty), distance markers to the next village plastered over with politicians' oleaginous smiles, the rubbery rattle of bicycles crossing cobbled stones, a rope shop's rust-colored wares in sheepshank-knotted bundles. Shops crammed with a blur of lottery tickets, soft drinks in bottles, month-old cookies, Rinso Detergent in singleuse packets, widemouth cookie jars, bolts of cloth stacked in gradations of hue, tins of sardines in oil — all of these being enclosed within a wire mesh cubicle to deter pilfering fingers. Shop fronts postered edge-toedge with entreaties for Highland Ice Cream, Koh-i-Noor Tea, the Vijaya Saloon and Tea Room. No arrack in this saloon: the word means "Hair Parlor."

A dirty-kneed young boy with shirt and shorts in different shades of white marches glumly to school in knee-length stockings with holes for his toes. When he reaches the schoolyard, he and the other students line up before their instructors for the roll. The school has open-air walls for ventilation, but today because of the weather the openings are covered with split-bamboo matting to soften the wind. Teachers have lesson plans for gusty days like today when zephyrs can whisk a sheet of paper off a desk any moment.

This being a deep-country hamlet, there are Buddha flags on every storefront and most of the houses. The only national flag in evidence hangs above the entrance to the police station with its barbed wire perimeter and sandbagged guard hut at the entrance.

The bhikkhu arrives, carrying his temple’s pirit book on a pillow covered with a piece of white cloth. One of the women opens a hamper and gives him a bundle tied with string. It contains milk rice which has been cooked until solid then cut into diamondshaped wedges called koki — a shape and a name bequeathed by the British in a comestible they called a cookie. While the diamond shapes all look the same, each woman has her own ancestral recipe mix of coconut shreds, boil-down viscosity for the coconut milk, and spices. No self-respecting wife would consider using another woman’s recipes.

The bhikkhu greets the women, then parts a curtain for them to enter the temple's image house. Village Buddhism is a different world than the great monuments tourists visit. A village temple's image house resembles a suburban bedroom with a twenty-foot ceiling, yet packs more carved, painted, and cloth imagery into its entrance and interior than any traditional museum would dare put on its walls. In a village vihara’s image house, the imagery never stops. There is no tastefully contemplative expanse of eye-calming white or creme.

It has been said that the image density in tropical shrines derives from jungle surroundings in which nature is pile upon pile of vegetation, layer upon layer of forest from ground creeper to weed to shrub to bush to grove of bamboo to coconut cluster to giant leaf- laden trees to sky, and thence to pile upon pile of cloud above. Emptiness does not exist because there is no place for it to reside.

A less lofty explanation for the ubiquity of visual excess is that appeals to the devout can be relied upon to anonymously donate funds for yet another decorative figure whose carvers or painters know how create near-identical resemblances of the donors. Hence it is in the best interests of bhikkhus — who have many messages to convey and a limited construction budget — to see to it that every iota of surface is put to use.

The bhikkhu removes his sandals at the entrance. The women’s feet are already bare, as they have been virtually all of their lives.

The lintel over the entrance is guarded by the makara torana, a fiercely glowering face with bulging eyes made of molded layers of plaster, a ghastly lolling tongue, fire from its nose that flames down both sides of the doorway and materialize into glowering chimeras bearing the hoofs of a pig, the eyes of a lizard, the teeth of a crocodile, the trunk of an elephant, the tail of a peacock, and menace of a dog. The demons look transplanted from Tibet, and perhaps are, for many of the themes in village temple art today emerged during a surge of cultural syncretism rebelling against the aesthetic dominance of eighteenth century colonialism.

Ceylon’s original Theravada (“Wisdom of the Ancients”) school of Buddhism assimilated ideas and images from the Mahayana (“Greater vehicle”) schools of China and Tibet. The visual residua seen in temples all over Sri Lanka today are a substrate of primordial pre-Aryan animist demon worship atop which lies a foundation of canonical Theravada Buddhism supporting multiple anterooms above, each of them an echo chamber devoted to one of the many squabbling schools of interpretation.

The women passing beneath the makara torana see none of this grand syncretism of the prehistoric and ancient, they see a blue demon eating an elephant, a pink demon chewing the head off a dog, blood flowing from their jaws onto their garments. The demons’ body hair is clustered in small bunches of four or five follicles that markedly resemble rice shoots emerging from the mud. The wrists and biceps of the demons are clad in geometrically patterned metal bands. Two cobras strangle an elephant while an infant demon wearing a diaper flings two infant elephants by their trunks into the sky. Other demons are armed with swords and clubs. All the demon mouths feature great flaring boar's-tusk fangs. The message the women extract from this is: “Bad planting omens beware: this fate awaits you once the bhikkhu recites pirit today.”

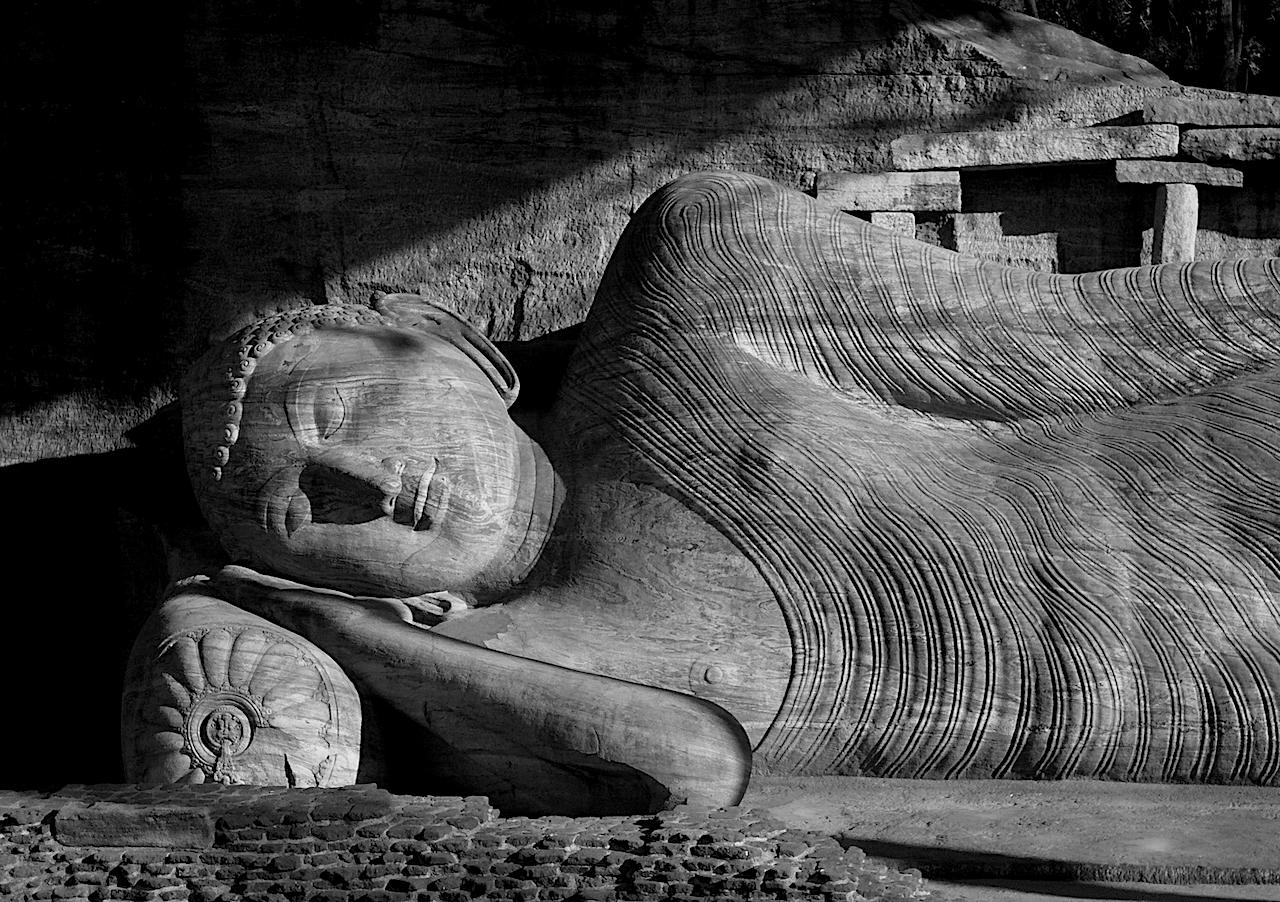

The bhikkhu rings the image-room bell. The women part the curtain to enter. They kneel into the anjali, an homage in which their feet, knees, elbows, hands, and forehead all touch the ground — the five major parts of the body being a metaphor for the Five Precepts of no lying, stealing, killing, sexual misconduct, or intoxicants. When the women rise to their feet, they face a great glowing ten-meter carmine-colored reclining Buddha made of brick overplastered in multiple layers, then sculpted and painted.

The Buddha’s eyes are half-closed, symbolizing the moment of parinibbana during which he extinguished the flame of existence to enter the no-self of nibbana, the nirvana of having blown out the flames of ignorance, desire, and delusion after a multitude of lifetimes passed in pursuit of this final flicker of the candle of self.

The soles of the statue’s feet are painted with a whorl of thirtysix signs of a true Buddha. The cave ceiling above is decorated with a checkerboard of identical images of the Buddha in samadhi or seated meditation. All 547 of the replicas are identical, each of their six colors having been applied by pressing tempera through a stencil, silk-screen style. The number 547 represents each of the previous lives of the Buddha-to-be before incarnating for the final cycle of mortal samsara in the body of an infant born in a Himalayan foothills village named Lumbini.

On the long altar beneath the recumbent statue the women light coconut-oil lamps and proffer jasmine and marigold flowers they gathered on the way to the vihara. Then the bhikkhu asks (as though he didn't know) “For what do you wish pirit sung?”

The reply: “That the paddy shall prosper.”

Pirit connects the bhikkhu on a single thread to words uttered by the Buddha himself. When someone became ill or felt threatened by a malefic, the Buddha or a disciple would knot a white thread around their wrist while reciting the words, “Dhammo have rakkhati dhamma charim” — “Dhamma protects those who protect the dhamma.” The phrase would activate the dhamma residing within the individual and the person would be protected by the quality of the dhamma he or she practiced in daily life. Over the ensuing 2,500 years a multitude of specific chants evolved, collectively called pirittas. The act of chanting them was called pirit. The amulet of a single white thread around someone’s wrist signals that person properly adheres to the Five Precepts of the Dhamma — no lying, mendacity, intoxicants, impure physical relations, and so on. The white thread awakens the moral force of satyagraha, the ideal of commitment to moral propriety which entered into the Buddha as he sat under the Bodhi tree at the moment of attaining Enlightenment. Pirit thread is encircled around the adjoined little fingers of a couple desiring to marry; when unwound by the bride’s father, they are married.

By the fourth century ACE, the era during which Constantine put on the purple robes of Imperium, and, arguably, the era when following the footsteps of Jesus transformed into following the strictures of Saint Paul, pirit chanting was already a codified six- century-old custom in far-away Taprobane, the name of the isle to Roman traders.

The Great Pirit Book or Maha Pirit Pota consists of seventeen suttas (Sanskrit sutra), of which some are fixed and others vary for the occasion. Pirit is sung to protect from robbers and sickness and evil spirits, induce rain and a good harvest, to ease labor pains, bring down high fever, embark on a voyage or new venture, protect a house from evil.

Pirit normally lasts all day or night. The abbreviated sarva ratri form lasts a few hours. In the case of the women eager to get on with the planting today, the bhikkhu condenses it to a ten-minute gloss called a varu.

For this varu the bhikkhu faces the great Buddha statue and recites the Stanzas of the Victorious Auspices in the pirit's five monotones: followed by Stanza 15-A:

Yandunnimittam avamangalanca, Yo camanapo sakunassa saddo, Papaggaho dussupinam akantam, Buddhanubhavena vinasamentu.

Whatever bad portent, and what is inauspicious, Whatever unpleasant noise of a bird, Whatever evil planet and dream unpleasant, Let them all come to naught through the power of Buddha.

Nakkhattayakkhabhutanam

Papaggaha nivarana

Parittassanubhavena

Hantu tesam upaddhave.

Of asterisms, yakkhas, and demigods, For the warding-off of evil planets, through the power of the Protections, May their dangers come to naught.

He ends with an invocation used so often in the rice regions that preschoolers already know it by heart:

Sassasampathi hoter ca!

May the paddy prosper!

The women depart the gama amid housewife flags of drying laundry and the acrid smoke of burning wood from kitchen fires mixed with the incense of a mosquito coil. From somewhere comes the dull regular thuds of a vangediya, a mortar and pestle made from a hollowed-out coconut-palm trunk plus a thick, grippolished pole. It is used to husk rice, powder curry spices, mash vegetables, crack nutmegs. After a dozen years its scent is an amalgam of every spice the house has ever served.

They pass mounds of sand and brick, leftover remains after the construction of a new house, a bridal dowry financed by two decades of rice harvests. A large earthen pot under a window awaits its next charge of powdered lime mixed with water, enough whitewash to shield the hand-smoothed plaster of cow dung and mud against the fearsome sheets of wind-driven southwest monsoon rain.

In preparation for two-month season of springtime rains, the sand heap is rimmed by a barrier of bricks cross-stacked two bricks high, just as the earliest known stupas were rimmed by stones to keep their heap of surplus rice from washing away. To this day one of the five basic stupa designs known to historians is called the paddy heap style.

This is the yala planting, the springtime planting just before the arrival of the southwest monsoon. The shoots must be seeded in May, transplanted in June, harvested in September. There were no calendrical spring–summer–autumn–winter seasonal demarcations in ancient Lanka. There was the yala planting before the May-June monsoon, the growing season through September; then the maha planting before the autumnal monsoon from the northeast, followed by its hundred-day growing cycle.

Aruvudu (New Year) is at the end of the maha season, in midApril. Aruvudu is still traditionally celebrated by boys throwing firecrackers at the monkeys, while girls gather lotuses from the ponds. The married women prepare a great communal feast and the men get drunk on a home-brewed coconut arrack called kasippu.

In recent years the Buddhist and Christian clergy have enjoyed a rise in the number of young men who abjure alcohol of any kind, based largely on their disgust with the behavior of their fathers. Much to their delight, these abstainers discovered rewards well beyond clearheadedness, communal respect, and the ability to hold jobs. They also enjoy the clandestine visits of “kasippu wives” who face many nights of drunkhusband longing in their futures before the end of menopause and their transition from wives into community elders. A pair of socks or a belt wrapped around the outside doorknob is a “do not disturb” pennant every young man knows. What those same young men do not know is that a bhikkhu’s robe bunched over a clothesline sends the same signal to women in the know. The dilemmas posed by the congruence of a positive virtue with a negative desire are not raised in the bhukkhu’s monthly poya-day homilies.

The six women leave the bustling life of the gama behind as they pass through the tisamba or communal green. It is partly a pasturage where the cattle are kept at night, but in the rice cycle’s long and low-maintenance growing season, it is a convenient place for the gama's alternate economic lifeline, gadol (brick) making.

The gama’s busy contingent of gadol makers are paddy cultivators turning the long growing season's spare time and their expertise in working with wet earth into extra income. The island is dotted with pockets of silty clay that can be shaped into rectangular forms that harden in the sun.

The cheapest gadol are sun-dried to a hardness that a fingernail can just scratch. The gadol bakers begin by compacting handfuls of iron-red earth into rectangular wooden forms. When the form is lifted away the biscuit of wet clay will become firm enough after six hours under the sun that it can be handled without crumbling. The biscuits are layered into rows and covered with criss-crossed layers of plaited cadjan (coconut) fronds to keep off the rain. Two weeks later they are durable enough for box border and doghouse duties.

To make construction-quality gadol, the brick bakers stack several thousand sun-dried biscuits into a structure longer and higher than a village house. They leave tunnels penetrating from one end to the other. The men plaster the entire outside surface of the structure with mud, fill the tunnels with cadjan fronds and fallen tree limbs, set them afire on a windy day. They continuously stoke the resulting inferno from morning till dusk. Three days later when the bricks finally cool enough to remove. the gadol bakers brush aside the baked mud crust, and sell the bricks for a few rupees each.

Coconut logs burn the fiercest because of the rich oil embedded in the pores, but coconut logs are so expensive that they are burned only for cremating those affluent enough to afford the traditional Buddhist ceremony. A small grove of ten coconut trees can supply a family with water, oil, and white flesh throughout months-long dry seasons. Water from an immature coconut is so pure it has been used in lieu of intravenous saline solution during an emergency surgeries in the fields or roadside.

The women cross a concrete bridge made of one-by-four-foot, three-inch-thick slabs lain corduroy fashion across three rails left over after the railroad nearby changed its track size. The irregularly broken halves of the former bridge lie in the swirling water below. It had been built by a politician in an election year. He was voted out office when the bridge broke in two and villagers discovered he had diverted the reinforcing rod to the construction of a new room for his house.

The water beneath is a tourmaline-colored stream with green moss ribbons swillowing as its hair. The path to the paddies curls past a bower where once a man saw two six-foot Green Reaper snakes twine themselves around each other as they mated in an erotically sinuous dance no village dancer has ever dared to mimic. In poorer houses, palm fronds dry on poles for future roofing materials. Plaited palm frond leaves are called cadjan and are the most all-purpose building material on the island. Long ago, coconut harvesters noticed that if the stem of a coconut frond is split lengthwise and folded over, the leaves cross at a right angle. Weave them tightly and they become a windproof, rainproof mat. Today, as the six women pass through the fields and hamlets, cadjan is so ubiquitous they don't even notice it — cadjan house roofs, cadjan chicken coops, cadjan pig sties, cadjan doghouses, cadjan bissa roofs to keep rain and rats out of the stored rice, cadjan cooking rooms, hoops of cadjan covering oxcarts, cadjan privies, and cadjan walls for the smaller boutiques.

From the same source as the rural proverb, “Why climb a mountain? The view from the top is always the same,” comes the villagers’ indifference to itinerant hawkers trying to sell woven wire screens. Why pay hard-earned rupees to discard something that nature freely replenishes, simply because wire screen is modern and you can see through it?

In the distance, the women spot the brownish green leaves of a rubber plantation. Nearby, a line of telegraph poles was abandoned by the telecommunications company when they migrated to buried coaxial cable. Today the cross-arms are empty except for birds' nests and ivy creepers.

Under a bluff with a huge barren-stone gash, Jaya the Quarrier advertises his wares by piling crystal-glinting gneiss and white dolomite alongside the road in front of his cadjan-roofed shack.

Not far beyond, an itinerant sawyer has moved his dieselpowered saw to where the forest begins. A mound of yellow sawdust announces that he's cut down a jackfruit tree, whose yellow wood is prized for Buddhist temple doors because of its durability across decades of hot, humid weather. When the bhikkhu sees the sawn shavings he will come with his begging bowl. He will then boil the shavings in water and salt to refresh the sun-faded saffron color of his robe.

The women reach the bemma, the bund of the village wewa, or tank. The water’s surface ripples silver glints in the intense overhead sun. The path atop of the bemma is wide enough for a wagon, but the base widens at a shallow angle on both sides until it is six to ten meters wide at the base. Unseen by the women, directly beneath them is a thick clay plug that seals the interstices between the broken blocks of granite that give form to the bemma's base. No one knows when the ancient Lankans noted the sealing properties of clay and devised uses to which it could be put, but clay plugs are as old as the tanks themselves and have become so compacted by weather and time that they have acquired a geological name, laterite.*

This, coupled with the fact that the tank's inner face is lined with chunky scree to dampen waves and thus inhibit erosion, points to a water-awareness among Sri Lankans which is as ancient as two millennia, yet as today as the six women whispering their way through their timewind of lives changed very little by the zephyrs of self that they inhabit and depart.

As the women near the far end of the bemma and the descent that leads them to the paddies, they pass the tank's gal penna — literally the “rocks over which water jumps,” meaning a spillway. The stone-strewn watercourse below it is dry today — as in fact it is dry most of the year.

Today several men are harvesting round stones by spading through the watercourse’s gravel-silt bed, grading their gleanings to size by hand. Their sarongs are doubled-over at the waist to raise the hem from the ankles to above their knees. When they have accumulated a bullock cart load of the smooth stones, they will sell them to Jaya the Quarrier, who will in turn announce via a new rock pile that he has a supply of smooth stones. Villagers will buy them and set them one by one, by size just as the workers have chosen them, into a patio surface.

The gal penna exists only to rid the tank of excess water at the height of the monsoon. If the water were to breach the crest of the bund, it could quickly cut a channel into it, and that would mean the entire village turning out in the drenching rain for frantic emergency repairs, hurriedly jamming sticks into the eroding water, followed by wads of grass to stanch the flow, then reinforced with stones from the stream bed and broken bricks brought from the gama on the backs of puffing men. Hence part of each village's water awareness is just how many inches beneath the crest of the bemma to place the spillway, given how fast the area's catch basin can fill during the rush of the monsoon’s first rain, so that water will neither be wasted nor rise high enough to invite ruin.

Just before they descend to the paddies, the women pass the bisokokotuwa, where irrigation water is released into the network of ela canals and horowwa sluices. In uneuphonic English the name "bisokokotuwa" is translated “sluice tower”. The bisokokotuwa is a canal that flows straight down. Its purpose is to convert the potential energy of vertical pressure into the kinetic energy of horizontal flow. Water from an elevated reservoir flows through a gate into the top of the tower where it tumbles to the base, and thence out another gate into the array of individual paddy canals. The adjustable gates regulate the flow but also help the tower act as a silt trap. The simple concept of the bisokokotuwa made possible the ancient kilometers-broad deep-water tanks, and hence the fertile island economy that exists today. Without this year-round supply of gravity-regulated water, Sri Lanka would be an arid island with a jungle in the mountains, drenched in the monsoon and parched the rest of the year.

The women pass the trodden earth of a winnowing circle now riven with springtime shoots where last fall's rice fell into its cracks. A few moments later they cross The Rockery, a shelf of rain-eroded precambrian granites which tumble out into the paddies like a garden of meditating boulders. Then to the Evlum Sanni field, christened two years ago after the demon god of difficult breathing and pains in the chest. One day while weeding his paddy the owner suddenly clasped his chest and fell where he worked. He was gone before his friends could reach him. This year his paddy is an expanse of weeds, for he had no sons.

Then to Veena, the Place of the Wooden Flute, where once a hunter listened to the knotted whistle of raptor wings as two overhead hawks culled and divided their prey. He turned the sound into a tune still played by the village veena player as he accompanies devil dancers exorcising Kana Sanni, the demon that brings blindness. The dividing of the birds happened so long ago that a village grandmother's mother learned of it from her grandmother's mother when she was a child, yet its melodic memory is still relived every year during the end-of-harvest ceremony

They pause at a tiny cloth shaded grave to vandinawa their hands into the prayer clasp which touches their index finger tips to their foreheads at the bindu or Buddha-eye point while their crossed thumbs touch their lips.

The candle on the child’s grave wards away Kalukumara, the sanniya demon who wills that women remain childless by miscarriage or the death of their infant before its first year. The unwritten message is that child beneath the candle had not reached its first birthday.

Of all the demon spirits called sanniyas, the women fear Kalukumara most. He was an ancient prince who plotted to usurp the throne from his father. A humble village woman who possessed the magic ability to peer into the souls of men confronted the prince in front of his father. His plot thwarted, the prince’s first thought was to kill the woman. But then decided he could harm her more by seducing her to implant malign semen that would make her barren. Since she already knew of his malignity and the falsity of his disguise as a handsome man, he had to seduce her in a dream. Over time the superstitions surrounding the Kalukumara story have turned the spirit of the evil princeling into an invisible demon that lurks in the shadows near rivers and lakes. He emerges in the dreams of budding young maidens whose greatest fear is that they will not be able to conceive.

That is why the erotic dream related earlier this was so portentous. Of the thousands of demons — demons of torment, demons of hostility and denial, demons of the dram (liquor), demons of the mythical and divine, demons of the planets, demons of the ancient pre-Lankan Yahksa hunter-gatherers — malign as these may be, they are far exceeded in virulence by Kalukumara. His name translates to Black Prince. He disguises himself as a monkey, a cow, a dog, and handsome men; hence these creatures must be regarded with suspicion. In the womens’ dreams, Kalukumara is a muscular and virile young man. But that is only his disguise. If they awake from their dream they face a creature whose eyes are huge and bulging, his mouth has dozens of huge fangs, and his hands holds the hair of the woman’s future babies he will devour. He devours elephants by darting between their hind legs to hobble them, then he eats them whole. He leaves men alone but torments young girls with erotic dreams, and subjects married women to the lingering gaze of men who are not their husbands. Le mala and kili mala — menstrual disorders and fatal blood loss during pregnancy — are Kalukumara’s specialties among all the ailments brought by demons.

Surprisingly Kalukumara was born on the luckiest day of the year — a new moon day on Saturday, with the constellation Pusa (the three stars of Orion’s belt) in Makara, the dragon's house (the same asterism shape as Babylonia’s Capricorn).*

From the tiny tree planted to protect the grave of a miscarried child against Kalukumara, we sense how often Lankan women suffered frightening menstruations and agonies giving birth, and how often they were entrusted with the gift of new life, notably the planting of rice, to counter their fear of barrenness. That is why, while men may plow, till, and weed the paddy, only women are allowed to plant the seedlings.

*There is no known link connecting the near-eastern and subcontinental traditions. Since Orion and Capricorn are in opposite sides of the sky, the House of Makara refers to the season between the summer and winter solstices, the yala planting season.

Flocks of water birds line the fresh-plowed paddies, seeking grubs brought up when the previous harvest’s roots were plowed over. The men have prepared the paddies well. Being low-country growers, the change in water level between the walkways (which are also property lines) is only a few tens of centimeters between each. The descending staircase of individual plots drops only eight meters from the ridges of coconut groves and rubber trees that rise inland from the paddy field floor to the drainage channel winding its way to the next field of paddies half a kilometer away. In the high country, rice terrace walkways that separate paddies are three to five feet above or below each other. There the men spend as much time repairing leaks as they do plowing.

But here in the coastal lowlands drainage is the problem. The men are kept busy maintaining arrays of drainage runnels that splay like the spines of an opera fan running from the high end of a paddy to an efflux gate at the bottom. The cultivators deepen the runnels in the direction of the water flow, down to the drainage gate that empties into the next paddy.

Three weeks ago the men had begun the plowing with the wap magula ceremony. In the ancient times, the king himself officiated at the first plowing. Today a local official is more likely to be involved. Wap magula is a time to sing old songs, blacken the reputations of tax collectors, patiently listen to the words of a bhikkhu who never turned sod, and remind themselves of their elevated status in the great govi vangsa heritage borne all the way from Dutthugemunu to the present in the phrase, “Wash the mud from a govi vangsa and he is fit to be king.”

Several weeks before, the paddies were flooded to soften the soil. After the liquorous party-time of wap magula, the men fetch their water buffalo and harness them to flat wooden planks the size of a house door. Ears laid flat back, nostrils flaring for breath, hour on hour the buffalo strain at their yokes, guided by to the touch of the stick and the shouts of their drovers, smelling of sweat and mud and droppings, endlessly criss-crossing the paddy until it is a slurpy sea of muck. The men set aside a small pond for lotuses in lieu of a Buddha shrine.

Finally the moment comes when the buffalo are released from their harness and led away to water and the go dane’s fresh grass. Their great curved horns loll back and forth like pendulums as they graze the grass nibbled so low a golfer could putt halfway across Sri Lanka and never encounter the same lay twice. The farmer's own legs tell him how hard his buffalo work, so he works them only every other day; the day between is haetapum arinava, the cows' day off.

Then the men go off to a stream to bathe and brush their teeth with their fingers, a twice-a-day ritual in rural Sri Lanka. Their boys join them, and like boys everywhere, try to make the biggest bellyflop to impress each other. The mens' spot also doubles as the place to wash the buffalo; any farmer traveling from one part of the island to another instantly knows a mens' bathing spot by a hoofhollowed muddy track leading down to the water. After the buffalo are scrubbed with coconut husks, they laze for hours in a muddy hole downstream with only their horns, eyes, and tips of their nostrils showing.

While the men were thus preparing the paddy, their wives were at home germinating the seed by placing it in jute bags, which they then soaked in water and drained. A day later they brought the bags of sprouting seed by oxcart out to the paddy edges. They carefully planted the seed in the richly manured germinating bed in one corner of the paddy. Their men had prepared this area by forming precise narrow furrows, into which the women poked the seed. Within days the patch was an emerald lawn of sprouts. When they reached twenty centimeters tall, it was time for transplanting. Now, white dagobas dot the distant hills as the women teeter across a bridge made of two coconut-palm logs. Then they're on the walkways between paddies, winding curve upon curve across the paddy rims, startling egrets as they approach a lone tamarind tree on a small patch of high ground. Every village sets apart a kurulu paluva of untilled earth as a home for the birds. The tamarind was planted time out of mind ago to supply something bitter to suck on as they work, which keeps mouths from drying even in the heat of the sun. The

hamlet boutiques sell chewing gum to youngsters,

but tamarind doesn't turn the stomach with a cloying aftertaste, and lasts longer.

A farmer amid the paddies of another hamlet waves to them as he stands patiently with his hands behind his back, gauging the flow of muddy water into his plot. He looks over the handiwork of his plowing and sighs at a tree shoot that he missed. He searches the sky for cormorants, for a paddy has been watered just right when cormorants come to dive. When one appears he puts one hand on the sluice plunger, a flat wood board which slides up and down the grooves of two chunky concrete floodgates. As the cormorant sets its glide path then extends it webbed feet for the splash, he pushes down the gate and turns toward home.

The woman with the baby first flattens the grass then shapes a crib for her child in the tamarind's shade, which she lines with a scarf she wore on the way out. She feels around in the grass for six stones she can remember as being there on her own first visit as a child. She arranges these in two triangles, making of them a lipa or place for the cooking fire. She centers the two chattie pots on them, and partly fills them with water. She snaps off some dead twigs from the tree, and lights them under the chatties. Before long the pots begin to sizzle and then steam, and she fills them; rice in one, a mix of meat and vegetables and curry in the other. The wind isn't any kinder now than it was two hours earlier at dawn, so she fluffs up the grass into a makeshift wind shade and lets the fire fend for itself. Fend it does, for within an hour steam from the pots streams flat across the paddy, joined by the cloth pennants of the scarecrows, which look like an array of sari-clad windsocks that all went on the same diet.

When the women eat, they first will put a handful of rice at the edge of the kurulu paluva for the birds and small animals, just as at poya day at the local temple the monks set aside the first handful of rice as alms to the animals. The Buddhist value of metta or universal love is satisfied when fields are set aside for the use of birds and the first handful of cooked rice is given to the animals. The other women inspect the tiny patch of emerald green seed paddy that will be transplanted today. A sixth the size of the paddy they are about to plant, the seedlings are bunched so tightly the wonder is that they could grow at all. The women bend over and begin. Backs barrel-stave strong and equally bent, for the next four hours they separate the tight mass of seedlings into clumps of four to six plants each. Wrapping one shoot around the clump in a makeshift knot, they throw each clump out into the paddy.

They were nearly silent as they had walked, each in their own thoughts. Now one of them lets her thoughts float free. The others listen without comment as the gama's self-appointed guardian of public morality goes through her recital of the week's week's scandals:

"...Abeysena swears it isn't, but I know it's the clap. My sister overheard the guilty party (she lives just down our lane!) at the dispensary last week. Even the orderly complained about her shamelessness!

And Karuna, I've got a juicy piece of news for you, too! You know the man who bought the cow from your nephew, who you said had such a scarecrow face? I heard about him and Jayasinghe's aunt's daughter. They were caught having at it on the mat! What is our sila, our public order, coming to these days, what with behavior like that! Fine example they are, shirking off their household duties on an old woman like me while they diddle the fiddle.

Tsh! It isn’t as if I don’t have enough to think about without hearing about those two! There's the wall to be re-moulded and redung. And washing! Mother's gone with her sister; they won't be back till tomorrow's sun is high.

And you, Udara, I caught you, you sly one! I saw you and

Farmer Borelessa's son in the crowd at Wesak. Really! Tsh on you two!

Then there’s Nimal! What he brings in from the selling potatoes he takes out at the dram shop. There's no peace these days in Savitri's hut, either! The other day she complained her son was nowhere to be seen. Just then he comes in with a bundle of grass as green as she is greedy. Only yesterday she wished her man Kumara would be struck by a thunderbolt. All because he didn't tether his goat tightly and it jumped on the table and broke a pot. And when a stray cow sets her dog barking, Savitri goes at it with a broom.

And how is it that we have missed you these three months, Deepthi? Last week we had the day of the germinating, and you were not there. Next day we put the seeds in the jute bag and soaked them with water, and you were not there. The day after we took them out to see how many had sprouted, and you were not there. Your father made excuses that you were convalescing in the big city hospital after the miscarriage of your firstborn. Well small wonder! I told him how many trysts you had in your unmarried days. He wasn’t in a bragging mood after that, the lout! Tsh on you, shameless one!

"Wimala, may I swap a betel leaf for an arica nut, if you will. You WON’T!? Shameless creature! It is not as if I haven’t had to scrimp these last months. First I had to postpone the ear-piercing ceremony for Nishantha till after Wesak Almsgiving, and now you won’t even swap a bit of arica nut! What is the sila of this gama coming to, with such as the likes of you? …”

To this mix of mother superior combined with treating every scrap of neighborhood trivia as a perfidy of neighborliness, one of the women replies with an old proverb: “She's wearing her needles thin trying to sew a thread into a sari.”

The men pass the time between plowing and planting by repairing the guard huts at the edges of the paddies. They will soon be needed. Between transplanting time and the burst of the rice, the paddy requires weeding by day and protection against rats and elephants by night. Wearing hats that look like a straw cockade with a wide brim, the men pull up the weeds, swizzle off the mud in the water, and throw the clumps onto the banks. Their children stuff them into jute bags to take home for the cows. Sprouts from the endless fall of fruits from the trees are replanted by the sides of the stream, in hopes of preventing future erosion. In between the biweekly weedings the men tie snap beans to their poles using the plant's spiral tendrils, and prune the tobacco rows they use as income-producing property-line markers.

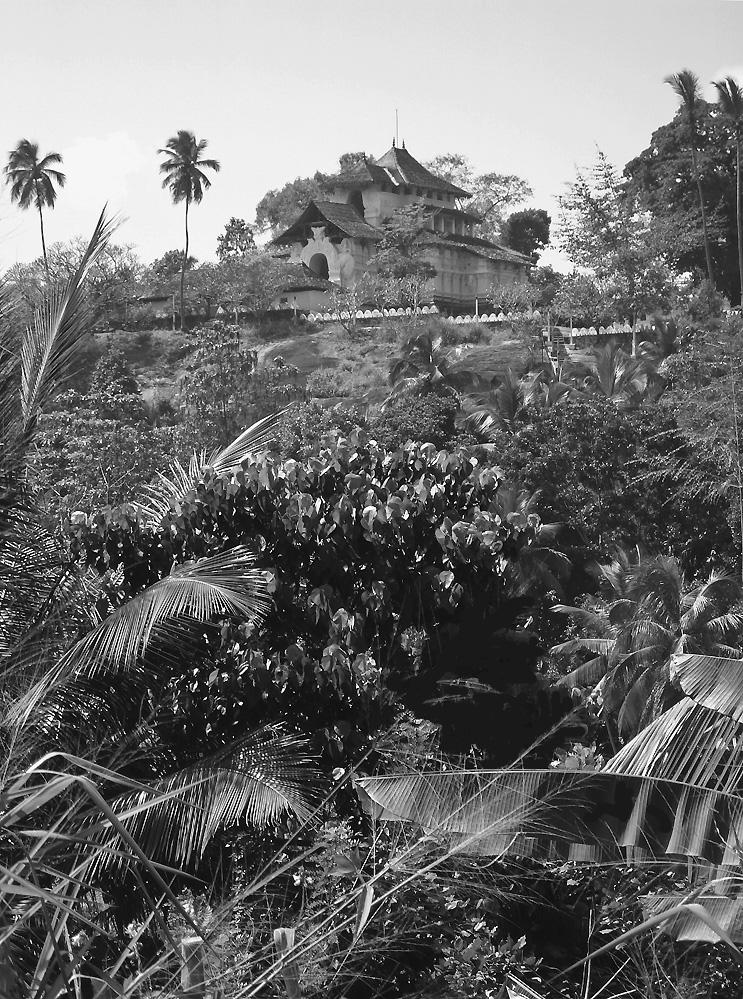

Anchorite woman living in a cave adjacent to a massive ancient Bodhi tree on the grounds of the Mihinthalaya Rajamaha Viharaya. Her only possession not shown in this picture is an ekal broom out of view to the right, which she uses to sweep her quarters at dawn to satisfy her Bodhi Puja duty to honor the moment. She rejoices at the fact that she has only as many lifetimes yet to live as there are leaves on the Bodhi tree.

Night predators are another matter. They make foul eating, and unless the moon is high, their presence is known only by their splashes and gurgles. So alongside each paddy there is a cadjan hut that looks like a Boy Scout camping cot with a thatched roof. It is made of six upright poles on which they lashed miniature roof beams and rafters made cadjan braced with sticks. These guard huts are only slightly larger than their builders. The sawgrass on which they sleep has long been flattened to the shape of their bodies. A pile of stones lies within easy reach of their throwing arm to hurl in the direction of any sound. The whole affair is a delight to mosquitoes. Little wonder that malaria is the prime suspect why ancient Lanka's population density was so low despite the island’s agricultural wealth.

As with most places of sleep, the men's heads point to the East, toward Suriya the Sun God, source of life and activity. A sleeping head must never point west, toward the waning of life that is the setting sun. South is also taboo, for that is the abode of Yama, the god of death. North is where all living spirits reside, so if the head is aligned in that direction it will be filled with confusing dreams from which one will awaken in a confused state.

The inter-monsoon heat begins when the thin blues and whites of a water-filled sky turn into the cloudless pure cornflower blue of a sapphire heaven. The paddy sprouts its flattened wheatstalk heads, which must be protected from parrots, crows, doves, and countless other birds — in addition to the nighttime predators. The entire gama shifts to a month-and-a-half, twoshift, twenty-four hour schedule. During the day the men catch up on their sleep and the women make new scarecrows of old shirts spreadeagled across lashed sticks. If they have time the women add gaudily painted papiermâché faces, discarded clothes stuffed with straw for bodies and legs, hands holding carnival twirlers. At night the men add their own cacophony of whistles, hoots, yells, songs, croaks, roars, beating drums, blowing conches, and threats to invoke demons and the evil eye.

The too-bright sky of mid-monsoon paints the birds in toobright colors — the stained glass windows of the kingfisher's dive, the swamp-colored skulk of a bittern in the grass, tufts of grass spat rearward by foraging wild roosters, the hoo-wooos of magpies seemingly three to every tree, an explosion of kews as the Seven Sisters clear a place to land. The great unquivering ibis's veer across the tumbling shears of wind turns as lightly on its feather tips as its black and white wings turn amid the immense gyre of blue.

The night shift is for grandfathers, old uncles, and children. Sunset-red meringue-pie clouds turn the dull gray of an afternoon storm's scud into the lucent brilliance of rising anvil-tops darting electrical spiders and roar-bruised air. The young boys come after supper, their schoolbook backpacks turned into dinner carriers for Grandpa — called Siya in the lowlands and Atta in the mountains. At night the Southern Cross rises in May and the Pleiades in December as the paddy guardians witch-watch through a frogfilled night.

Every night Atta reminds the youngsters how to spook the paddy birds:

Kaputu: kah! kah! kah!

Goraka: den! den! den!

Kamata: wah! wah! wah!

Korawakke: pwak! pwak! pwak!

Keetha: bulath! bulath! bulath!

His rhyme names the predator bird, then mimics its call: and finally chases it away (with the help of a few stones):

Crow: caw! caw! caw!

Warbler (on the goraka tree): tin! tin! tin!

Kamata (threshing floor) pigeons: hwa! hwa! hwa!

Water coot: pwak! pwak! pwak!

Blue coot: poola! poola! poola!

Usi! ... Kaputa! ... Usi!

Usi! ... Goraka! ... Usi!

Usi! ... Kamata! ... Usi!

Scram, crow, scram!

Scram, warbler, scram!

Scram, pigeon, scram!

When the children are finally asleep and the silver luminescence of moonrise comes over the wind-calm paddies, the grandfathers and uncles gather before a low fire. When the rice is high, Sri Lanka is dotted with paddy fires. There the talk turns not to politics or philosophy or the gossip of the village, but to paddies. Paddies they now own, paddies they did own, paddies they hope their sons might buy, paddies they wish they could own, curse their luck for not having owned, or wouldn't own even if they could. They do not think of any other thing with such unalloyed desire. Little wonder that almsbowl bhikkhis making their daily pindipada rounds stick to the towns and are seldom seen wandering the paddy paths.

Dukkha’s most eloquent disguise is the transience of beauty.

When it is rice's time, its death is as simple as its life. The Goyam gi reapers come to the field with their sickles. The children carry baskets and woven reed kulla baskets for winnowing. The women fetch reeds from the sluices and weave the cords that will bundle the sheaves. Lunches are hung over limbs, blankets over branches. Then the songs begin about cut, bunch, sheave; cut, bunch, sheave. The men cut, the children bunch, the women sheave. As the sheaves are tied, the women lift them over their heads and carry them to the winnowing ground. There they stack the sheaves all around the periphery. To pass the time the children invent an endless jingle. Each has a turn and must add a new line that relates to the last. All day they play it, and every day after until the harvest is in. Then they'll declare a winner for the best non-sequiturs:

Bane inne mokada — What is in your stomach?

Lamaya — A baby child.

Eyi andanne — Why is it crying?

Kiri batuyi netuva — For rice and milk.

Ko man dunna kiri batuyi — Where is the rice and milk?

Ballayi belali keva — The dog and cat ate it.

Ko ballayi belali — Where are the dog and the cat?

Linde vetuna — They fell into the well.

Ko linda — Where is the well?

Goda keruva — It has been filled up.

Ko goda — Where is its place?

Andiya pela hittevva — Where the andiya plants are.

Ko andiya pela — Where are the andiya plants?

Deva — All burnt.

Ko alu — Where are the ashes?

Tampala vattata issa — Thrown into the tampala garden ...

When the baby under the tamarind tree cries while its mother is off carrying a sheaf to the winnowing pad atop her head, the girls pacify the child by giggling, Hankutu! Hankutu! "Tickle! Tickle!"

Then they pull at each of its fingers while singing:

"This one says, I am hungry.

This one says, What's to be done?

This one says, Let me eat.

This one says, Who will pay?

And the little one says, I am the smallest so I must pay."

The name of the commonwealth system during the time of the ancient kings until 1832 is Rajakariya, The King's Duty. From its ancestral roots long before Dutthugemunu, Rajakariya built and maintained Lanka's great palaces, monasteries, and irrigation systems. Surplus rice, in turn, fed the workers who built them. It was a home-grown polity of quid pro quo: the economy was almost wholly based on consumption of rural products, so the machinery of state's first duty was to keep the rural base strong. The govi-vansa caste was therefore considered the highest next after the rodiya caste royalty.

Unlike indentured labor exactions in other parts of the world, ancient Lanka's Rajakariya was not a product of the lash. Nor was it like feudal Europe’s pyramid of alliances, which tended to shift society’s economic burden to the shoulders of those at the bottom. Rajakariya was based on concordant cooperation which obliged military protection and water resource development from the kings, and the combined labor of the community in return. The govi-vansa regarded Rajakariya as labor whose ultimate beneficiary was the rice paddy.

When the Portuguese arrived in 1505 their primary concerns were monopolizing the spice and gem trade and converting Buddhists to Catholicism. The giant reservoirs of the Anuradhapura kingdom had been effectively abandoned for five hundred years, and those of Polonnaruwa for over two hundred, both civilizations having been overrun by ruinous invasions from Chola India and malaria at home. Rajakariya in those areas had become a matter of each community fending for its local irrigation system as best it could. Rajakariya still existed in the Kandyan kingdom, but there so much water poured from the skies that paddies needed few vast waterworks. Hence Kandyan rajakariya was harnessed for the building of palaces for the kings and works for the Sangha.

As caste consciousness grew, so did the caste basis of Rajakariya. When the Dutch drove out the Portuguese in 1656, they came to regard Rajakariya purely as a source of cheap labor, oblivious to the caste implications involved. Sri Lankan cinnamon was considered the best in the world. Cinnamon grew best in the humid, diseaseridden lowland jungles. Instead of rewarding with cash, the Dutch took to rewarding with the lash.

By this time the govi-vangsa caste had come to consider itself not as first among equals, but first, period. The more socially manipulative personalities elevated themselves into a hereditary caste of village headmen. Other castes, especially the lowland salagama, karava, and durava, performed manual labor ranging from the strenuous to the onerous. These caste names are still to be found in the marriage proposal ads as a hint to marriage brokers who have evolved a tidy pre-qualifications business serving caste-aware families with spare daughters.

For working in the pestilential cinnamon jungles, the Dutch rewarded the salagama caste with privileges similar to those the govi-vangsas enjoyed during the time of the great kings and their tanks. Soon karava and durava farmers far distant from the jungles were registering their newborn with lowland salagama families so their children would enjoy cinnamon-peeler privileges.

When the British took over in 1795 they disdained Rajakariya as an example of their notion of the backward Asian coolie mentality. That did not stop them from tinkering with the caste system to serve the needs of London rather than the villages surrounding the paddies. When the soup tureens being filled by the East India Company cried out for more cinnamon, pepper, or cloves, the colonists cranked up production. The result was threefold: workers began to die from exhaustion; those who didn't die deserted as 60 soon as they could; and those who didn't desert took to registering their children with salagama families in the highlands.

This reinforced the British assumption that Lankans were lazy, so they courted military retirees at home with capital and ambitious farmhands with promises of free land. A brief experiment with Chinese immigrants to show the locals what the work ethic was all about flopped. The Chinese took one look at the malarial jungles and promptly decamped to the coastal towns where they started small cash-and-carry businesses.

The European contribution to Ceylonese history is not an edifying affair. Those with investment-grade capital were remorselessly self-interested, put their money into ventures from which they alone prospered, piled onto the natives more work than they could handle, turned caste differences into manipulative alliances, took over more property than they allowed to their workers, corrected the character of everyone they encountered, experimented with the latest economic theories at home but suppressed them in Ceylon, and spoke eloquently of statecraft and law while surrounding their bungalows with thorn bushes and fences.

If the East India Company saw no problems with salagamas dying in the jungles, the government administrators were equally ill-informed when it came to the building of roads. To the Ceylonese, using Rajakariya to build roads was worse than an insult. Roads were never part of the ancient Rajakariya bargain. The Kandyans in particular saw roads as a symbol of the loss of their freedom. Their three-century aloofness to European dominance relied on there being no roads. Without transport, no army could penetrate the jungles. Moreover, roads occupied land that could be more usefully employed to grow rice.

But in London loftier heads were crying to be heard. Names like Ricardo and Bentham devised words like “utilitarianism,” “laissez faire,” and “plantation”. Soon enough these ideas turned up in the colonies. The British notion of hands-off local administrative autonomy had been badly mangled by the American revolt. Whitehall weighed in with the observation that as Napoleon was now safely sequestered, there was no longer any reason why strategic colonies should be allowed to run at a loss. This Rajakariya business might be good for public works, but the colonies should also be revenue sources. These ideas translated to labor being moved at will and taxed in coin rather than measures of rice or pots of curd. Having turned their own farmers into industry serfs, they saw no reason why the brown coolies of Asia should receive any better.

In 1832 a Commission of Eastern Inquiry, better known as the Colebrook-Cameron Commission, did what many such commissions do: they suggested changes whose net beneficiary was themselves without much concern about the consequences for everyone else. One of their ideas was to abolish Rajakariya. They introduced taxation in coin rather than payments in kind. Where exactly a farmer who had rarely if ever seen a coin was suddenly to come up with an abundance of them the British left for the farmer to sort out. They assumed that plot-holding farmers would see the light and gravitate toward the tea plantations and their lifetime sinecures compensating for the low pay.

The farmers did indeed see the light. They stayed as far from plantations as they possibly could. The British were forced to import untouchable pariyar-caste indentured labor from India, thereby creating one of the most intractable social problems in Sri Lanka today. (The word pariah derives from pariyar.)

In the rice regions, the abolishment of Rajakariya was devastating. Removing the obligation to share labor on the community's behalf turned what was once everyone's business into no one's business. Who was eager to neglect their own paddy in order to take up the duties let fall by a laggard? An indolent minority came to dominate an industrious majority. Kasippu was an ever-reliable, cheap alternative to personal responsibility, which exacerbated the already intractable.

There is a Sinhala word, damana. It means, “park-land with high trees.” These days is more often describes an abandoned and overgrown paddy. The oldest trees in a damana today are about onehundred eighty years old. Why? Within ten years of the ColebrookCameron Commission, thousands of community irrigation systems and their paddies were neglected to ruin. Spillways choked up with wind-felled trees and brush. Heavy monsoons turned bund tops into huge gashes. Clogged sluices converted paddies into jungle, which the industrious and profit-minded plantation owners soon cleared and replanted with neat rows of coconut and rubber trees. Ceylon went from rice exporter to rice importer.

The British Council libraries in Sri Lanka today are models of proper British efficiency. Books are on the shelves where the card catalogs say they will be. The Sri Lankan staffs are knowledgeable and helpful. The study rooms are filled with industrious young people and serious scholars. A mislaid card is replaced with sympathetic dispatch. An unreturned book is mourned like a deceased cousin.

Yet the section devoted to Sri Lankan history and culture is a small proportion of the size of the stacks devoted to England. To this day the British idea of Sri Lanka's 2,500-year history is that it sums to a few percent of Britain's contribution. To the young Sri Lankan visitors to the Council Library today, the Western historian’s relevance to their futures is a speck of dust hovering in the air as the great rice culture of Lanka cycles into its destiny.*

* This book derives from notes written during my residency in Sri Lanka from 1991 to 1995, supplemented by multiple visits since. It makes no mention of the Tamil Tigers war of the 1990s and the disastrous Rajapaksa era of the 2000s because those events, while worthy of a literature of their own, simply do not relate to the rice culture and its legacy as studied here.

At the kamate or threshing circle, the children let slip the knots binding the sheaves. Rice stalks collapse loosely into heaps surrounding the kamate. The gama's wiseman, the steward of the ancestral traditions, arrives dressed in white robes with a green sash draping his neck, the traditional garb of being in direct communication with the ancient gods that protected the isle before the coming of the Aryans commanded by Vijaya about 500 BCE.

The wiseman carries a sharpened pole, which he now pierces into the harvest-hardened earth at the center of the kamate. Wound around the pole is a twine with a sharp stick tied to the outer end. The wiseman unwinds it to the length of his forearm. His son — who is learning the precise sequence of events and words of this ritual, the Sakwala Chakraya — scrapes a circular furrow at the taut end of the string. The wiseman rotates on the opposite side of the pole until the furrow becomes a circle.

The wiseman unwinds the string another forearm’s length and his son traces a second circle, centered on the first. They repeat this six more times, the circles representing in turn the Earth at the center, the Sun, the Moon, and five planets, all rotating around the Earth point. Then the son pulls the string outward until it is twice the length of a man’s height. The two of them then scratch two more circles, the outermost one a forearm’s length larger than the innermost, turning the outer circles into an annulus. The wiseman aligns his back with the sun directly behind his shoulders. He instructs his son to gouge straight lines from the pole to the four quadrants, symbolizing the four legendary kingdoms of pre-human Lanka — the Yakha peoples, the Gandabbas, the Kumbhandas, and the Nagas — who occupied the island before the Aryans and their Vedic religion arrived about 500 BCE. In the outer annulus of the circle the headman’s son scratches the outlines of fish and shrimp, representing a chattie cooking pot filled with rice and fish.

Over the next hour the wiseman instructs his son to trace a complex array of circles with crosses in the center, straight lines, a

Architect’s drawing of the original Sakwala Chakraya found incised into a rock surface in an inconspicuous overhanging ledge near the Isurumuniya sangharamaya near Anuradhapura, the ancient kingdom of Lanka’s capitol city. Its existence, function, or mythology related to it was not mentioned in historic records until the British Archaeological Commissioner H. C. P. Bell identified it as Sakwala Chakraya in his Archaeological Survey of Ceylon Annual Report published in 1901. The name translates to “Universe Cycle” in Sinhalese. None of the pictographic images in the outer annulus, which appear to depict fish, turtles, and seahorses, relate to traditional Buddhist iconography of vines, swans, and lotus blossoms.

The only known example of what the British Archaeological Commissioner H. C. P. Bell identified as Sakwala Chakraya in his Archaeological Survey of Ceylon Annual Report published in 1901. In his words, “This weird circular diagram, incised on the bare rock—even more unique in a way than the elephant bas-reliefs of Pokuna A—may with every show of reason claim to be an old-time cosmographical chart illustrating in naivest simplicity the Buddhistic notions of the universe. The concentric circles with their interspaces at the centre of the chakra can assuredly mean only the Sakvala, in the centre of which rises Maha Meru, surrounded by the seven seas (Sidanta) and walls of rock (Yugandhara, &c.) which shut in that fabulous mountain, l,680,000 miles in height, half below, half above, the ocean's surface.” second smaller bull’s eye in an upper left quadrant, several pictograms whose shapes he had memorized just as his son is learning them today, but whose interpretation has been lost to antiquity.

Finally, the wiseman puts a sickle on one side of the center hole and a conch shell on the other, lying with its open side facing up.

At the hour the gama’s astrologer has deemed the most auspicious, the wiseman hefts an armload of rice sheaves and trudges clockwise four times around the concentric circles. He utters words he repeats at every threshing time yet whose meanings he suspects but does not really know. The memorized words are in a language which has passed into the present virtually unchanged from long before the Pali of Buddhism — perhaps from before the Aryan Indo-European prakrit spoken by Vijaya. It is the rice-cycle language of the bali and tovil rituals, ancient tonguedances extending so far back into Lankan ways that no one today, not even scholars, can specify their span. As with Latin to the Catholic, Sanskrit to the Hindu, and Pali to the Buddhist, the ancient appeals to the rice gods for protection are an archaic language whose power lies, as language's power always has, in fencing out the unknown. Like Christian-carved crosses on druidraised stones, Buddhism replaced the ancient burnt offerings, blood sacrifice, homages to the sun, and glossolalia of a person possessed by the spirits, with pirit chants and the knotted yellow thread. The theologians of the Sangha buddhistified the Yakkhas, Gandabbas, Kumbhandas, and Nagas by rebadging them with the words of The Four Noble Truths.

But in a world so close to nature as the rice cycle, nature gods neither die nor reincarnate. They live on in paddies as unchanged by the realities of Air Lanka's dreamliners filled with tourists alighting from aloft, just as they lived unchanged by birds fluttering to a tamarind tree three days, three years, three centuries, or three millennia ago.

When the wiseman has finished invoking the rice gods, he walks through the harvested stalks until he reaches a flat altar-like stone at the edge of the kamate. In a water-pooled rectangle chiseled into the surface, the wiseman places flowers for the gods. All through the threshing and winnowing about to begin, fresh flowers will replace those that fade, just as the human’s role in the rice culture is the butterfly looking for nectar.

Threshing begins. The first sheaves are shaken above a cloth sheet to ensure that the next planting's seed grain will be the ripest. The rest of the rice sheaves are strewn evenly over the kamate. The farmers then bring in the same buffalo that began the season tethered to a large flat board that smoothed the mud surface of the paddy. Now they are tethered to the same board as they tread in lissajous circles around the kamate. Ears laid back, nostrils flaring with each breath, they merge the season's end with its beginning, trudging belly-deep in the stalks until the husks of the grains are cracked under their hooves. Hour after hour they circle, smelling of sweat and leather and droppings and dust, endlessly converting hoof-steps into rice grains in their circular world. If time is a line, its direction is a circle.

Finally the moment comes when they are released and led away to water and the go dane’s ripe maize. The men and women then wade into the chaff. They kick and then stomp, kick and then stomp, freeing the last grains from their husks. The men rake the stalks into heaps. The women slide kulla baskets into the chaff on the ground and toss it up to the wind. The wind catches the flax and arcs it to dust trailing away across the paddies. The kullas lift and then hurl, lift then hurl, with a pause in the middle to get the balance just right, lifting and hurling in the dance of the paddy. The women wear their skirts hiked up to their knees as they shove their baskets into the grain. Scoop-shaped and broad, as wide as their encircled arms, the kulla carries the rice in rice's time, mangoes in mango time, fodder and fruits, greens from the garden, and in the midseason as the paddy grows it is pillowed with clean straw for the guard dog nursing her new puppies. The work is unpausing, backs aching from bending as they fill baskets and pouches with mounds of the grain. One day for threshing, another for winnowing, ceaseless hard work from the cold glow of dawn to the last light of dusk, and longer if there's a winnow moon.

It takes three thousand years of rice make a govi-vangsa. It takes fifty to kill one.

During the time of the Buddha, the city Vesali in northern India was afflicted by drought, disease, and “fear of the non-humans.” The Buddha recited the Ratana Sutta, the Discourse on the Jewels. His disciple Ananda went through the city repeating it while sprinkling water from the Buddha's stone begging bowl over people’s faces. The King commissioned a golden image of the Buddha, which he placed in the bowl. He ordered a great almsgiving and bade the citizens to observe the moral precepts which the Buddha observed. The city was decorated as monks chanted the Ratana Sutta in all its streets. The rainy season arrived at last, poured for days, reviving the land. The pestilence disappeared.

This ceremony came to be called Gangarohana. Old chronicles record that it was performed again to end a drought during the reign of Aggabhodi IV (658-674 ACE), when monks chanted pirit using the Ratana Sutta. It was repeated during a drought in the time of Sena II (851-885), and again under Kassapa V (913-923), whose kingdom suffered no drought but was beset by a pestilence which was warded off after the Sangha chanted the Gangarohana. Though propitiations to the gods of old preceded the harvest's threshing, the bhikkhu's pirit is considered more powerful than either bali or tovil. When the last of the grains have been whisked into sacks and the kamate floor is clean, the bhikkhu comes to chant the last mantra of the season, the Ratana Sutta as it was uttered from the Buddha's own lips. The first two verses establish his preeminence over the older gods:

Whatever spirits are assembled here, Those of the earth or those of the air, May all those spirits be happy, Let them listen to what is being said.

Therefore indeed, all the spirits listen, Having loving kindness towards the human beings Who make offerings day and night; Therefore indeed, protect them diligently.

Verse 8 harkens to the harvest ceremony's pole:

Just as Indra's post which is fixed to the earth Cannot be shaken by the four winds, a good person is similar to that. To one who sees the four Noble Truths, The jewel of the Sangha is excellent.

The 14th verse signifies the end — and the finality — of the harvest, whether of rice or the cultivation of the spirit:

The past has been destroyed, There is no becoming of the new, Their mind is unattached to a future existence, They have destroyed the root, Their desires are absent. As this lamp is blown out, The wise one becomes passionless.

The bhikkhu ties pirit thread around the wiseman's arm, then recites the Maha mangala sutta and the Keraniya metta sutta, the Great Discourse on the Auspices followed by the Discourse of Loving Kindness, among whose verses are:

Whoever there are living beings, Either worldly or spiritually developed, Long or those who are huge, Middle-sized, short, atom-sized, fat, Those seen and those unseen, Those who live far and near, Those who have become and those who expect to become, May all beings be happy.

Standing, walking, or sitting, or lying down, As long as one is free from sleep, One should make up his mind on this thought: That a loving life is holy living.