E N Q U I R Y

Welcome to the Summer term edition of our staff Learning and Research Journal, the Enquiry. Across this issue you will find a wealth of ideas and reflections from members of the Downe House community about all things educational research and Teaching and Learning.

We begin, importantly, with a section devoted to student perspectives about their own learning experience. Here, we asked students from different year groups to write a brief summary of something they enjoy or find useful in their learning. They were given no further brief or guidance. The comments are, not surprisingly, very insightful!

We then move onto a section that looks at motivation, which was our CPD topic for Lent and Summer Term. We begin with an overview of this CPD model, with some reflections by Nardin Thabet on what helps to motivate pupils. Matt Godfrey then explores this topic further by suggesting some practical strategies and tips to help with student motivation.

This section is then followed by an excellently insightful article by Kayleigh Bonwick in which she explores the many benefits of strength and conditioning. Next, are two articles about the topic of feedback. The first, by Sandy Clarke, considers some high-impact ways of maximising the impact of feedback and especially responding to it, with the second article, by Andrew Atherton, examining peer assessment. You’ll then find a five-minute video by Jane Basnett in which she walks us through some of the available digital tools for leveraging peer assessment.

We conclude with a short update on our Learning and Research Council as well as various suggestions for further thinking.

Our thanks go to everyone that took the time to write and submit an article as well as Sue Lister who was instrumental in preparing and designing this edition. The next edition of The Enquiry will be published in Lent 2023 as a retrospective of Michaelmas term 2022. A Call for Papers will be announced soon, but if you have an idea and would like to contribute please do get in touch with any member of the Editorial Committee.

The Enquiry Editorial Committee

Andrew Atherton

Charlotte Williams

Kerry Treacy

George Picker

A STAFF JOURNAL DEDICATED TO REFLECTIONS ON EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH AND TEACHING AND LEARNING AT DOWNE HOUSE SCHOOL

While there have been numerous strategies that I have learnt in class which have contributed towards creating an enjoyable learning experience, the one I have found the most valuable is the fact that the teaching of each subject is no longer restricted to merely sitting an exam, but goes beyond exam preparation to enjoying the actual subject.

I have felt this particularly in the way English and Physics are taught, where the material learnt in class has prompted me to go on to do wider reading and has enabled me to view the subject as a whole. For example, while studying Shakespeare, I have been able to link the themes in Othello to those in other works of literature, which has broadened my understanding of the play. By signing up to participate in the Elective Programme, I have also been able to learn about an area in Chemistry, Modern Drug Discovery, which I have been able to link to my current subjects such as Maths. Hence, this new approach towards learning has allowed me to connect various subjects together such that I can view them in a holistic manner.

However, there have been individual strategies specific to each of my subjects that have been valuable in helping my learning, and which vary subject to subject. For essay subjects like English, I have found it far more enjoyable that the way of teaching allows each student to think about a specific text and discuss their own initial thoughts without having any former knowledge of the themes (unseen poetry being a prime example). Additionally, the interactive nature of the lessons has made learning more exciting. Moreover, one thing I have found which has been really valuable in my learning of English is that during the lessons, we have been taught new methods of revision before the exams. I can use these in addition to my own revision techniques. Overall, with regards to all of my subjects, I have found recordings of the lessons to be quite helpful, as it allows one to revise the concepts discussed in class and consolidate them. If I missed any part of the discussion in class, I can review it in the recording.

Throughout my three years of the GCSE course, I have learnt the technique of ‘Iteracy’ with my English teacher. Iteracy is when at the start of each lesson we sit down in silence and complete an activity, whether it be from finishing the quotes or a short character analysis. By doing such an interactive activity ‘iteracy’ truly makes you think of many different quotes and puts the text as well as the quotes into context which is ultimately what makes you learn. It is an immensely useful activity and really helps with memorising important information as well as having time to collect your thoughts on characters. English has been the only subject where we do anything of the sort, and I think that it has made an improvement to my grades and when I am revising, I can consolidate my notes better. Due to the GCSE course being a big

‘ITERACY’ TRULY MAKES YOU THINK OF MANY DIFFERENT QUOTES AND PUTS THE TEXT AS WELL AS THE QUOTES INTO CONTEXT WHICH IS ULTIMATELY WHAT MAKES YOU LEARN.

step it is imperative that we have a deep understanding of language and characters so by using ‘iteracy’ we are able to uphold many interesting points and it is always good to have two contrasting views about one quote. Everyone in the UK who takes the same English Literature GCSE will be well versed in analysis but if you have a key point that makes you stand out, you have an advantage.

In English lessons, mainly literature, we analyse numerous texts and poems and each person has many different ideas. Instead of the class just getting told what the teacher thinks , we each go around and say our opinion. This is extremely important and useful as we are obviously not going to interpret something the same so by sharing each other’s opinions we are able to build a very strong analysis to apply to our essays. As a class we go into such depth about one simple phrase, but it means that we have so much knowledge which is a good thing! Not only does this make learning more enjoyable and helpful but it is intriguing and interesting.

One thing which I find valuable in regards to my learning is the independence we are given in our GCSE years. From the start of our GCSE courses, I have found that we are more trusted to lead on our own and truly be in charge of our academic studies. Although we have this freedom I also appreciate the fact that we can always go to our teachers for help and guidance. Furthermore, the revision preps and consolidation tasks we are given in class are something I believe are beneficial, as they enable me to consolidate my knowledge whilst effectively making revision notes. I think that the learning in Downe House is also very beneficial for us as students as there is a wide range of subjects that we can learn. For instance, we are able to take part in the Elective Programme, which I think is very valuable for our learning as we are able to learn and understand things that are not necessarily in the curriculum. I would say that it is very important to expand your learning beyond school learning.

ALTHOUGH WE HAVE THIS FREEDOM I ALSO APPRECIATE THE FACT THAT WE CAN ALWAYS GO TO OUR TEACHERS FOR HELP AND GUIDANCE.

OVER THE COURSE OF LENT AND SUMMER TERM 2022 MATT GODFREY (DEPUTY HEAD) SPEARHEADED A NEW MODEL OF CPD IN WHICH COLLEAGUES SPENT TIME OVER THREE CYCLES FOCUSSING ON A SINGLE TOPIC, IN THE FIRST INSTANCE STUDENT MOTIVATION. IN THIS ARTICLE, ANDREW ATHERTON (DIRECTOR OF LEARNING AND RESEARCH) OFFERS AN OUTLINE OF HOW THIS MODEL WORKED AND NARDIN THABET (TEACHER OF MATHS) OFFERS SOME THOUGHTS OF HER OWN ABOUT MOTIVATING STUDENTS.

In 2021 the EEF (Education Endowment Foundation) undertook a substantive examination of what makes professional development effective. Recognising its crucial importance in maximising teacher efficacy as well as pupil outcome, the EEF investigated a huge range of articles and research surrounding what makes great CPD. A core finding from their work, as well as the broader field of study, is that CPD is at its most effective when there is opportunity for its ideas to be embedded back into the classroom. There should be opportunities for reflection but also to take action. What change in my practice can I make? How might I evaluate it and when? How can I share these findings with other colleagues? These are all crucial questions.

With this in mind, Downe House has innovated a new model of CPD which has built into it opportunities to hear from colleagues and share best practice before implementing and trying out some of the ideas within Departments, and then coming back to reflect as a whole academic community:

In our first strand we looked at the topic of pupil motivation and we heard from a number of colleagues about what strategies work best for them. Below Nardin Thabet (who kindly volunteered to share some of her top tips with colleagues in Cycle 1) summarises her key takeaways.

Motivating students is what teachers do, though I have found most students at Downe House have good levels of motivation, and the rest can be reached with some guidance and a little nudge in the right direction.

For me, the most important aspect of student motivation is to assure them that they are very much liked. I really enjoy it when girls tell me that they “know” they’re my favourite. Making each girl or class believe that they’re my “favourite” is a winning strategy and makes for a fun and accepting work environment.

The second most important aspect is caring for the students – and I do that by having high expectations and uncompromising rules and consequences when these are broken. Lucky for me, the girls seem to appreciate this and understand that I do this because I believe they can rise to these expectations.

The third aspect of student motivation for me is to build on their subject confidence. I focus on effort and set clear and achievable targets. I plan all my tasks very carefully to help them succeed one step at a time, and discuss with them what hard work, practice and perseverance look like. And, lastly, the last aspect for me in building student motivation, is building their confidence in me. I want them to trust me. To trust that every class discussion, activity, or extension has been thought through and is designed to help them make progress – that there is a reason for every prep set and every piece of advice given. This is probably the hardest aspect to achieve; and I can’t say I’ve achieved it with every class or every student – but when this last factor is there the results are truly amazing.

Nonetheless, I try my hardest, but I don’t believe it’s all up to me. They are responsible for their choices. I always tell the girls that “my conscience is clear – I’ve done all I can, and the rest is up to you”.

DOWNE HOUSE HAS INNOVATED A NEW MODEL OF CPD WHICH HAS BUILT INTO IT OPPORTUNITIES TO HEAR FROM COLLEAGUES AND SHARE BEST PRACTICE

One trademark of teachers at Downe House is a love of their subject. Enthusiasm is an important means of motivating pupils since it is infectious. However, enthusiasm alone is not enough: a nuanced approach to classroom management is also needed to engage all pupils effectively.

We are fortunate to have a fully committed, highly professional and experienced team of teachers at Downe, and the appetite to learn from each other is strong. At a busy school it can be hard to find the time to share best practice – so we ensure that time is set aside for this purpose.

During one of our recent regular mid-week training sessions for all staff, three teachers – Mrs Barnard (History and Politics), Ms Thabet (Maths), Dr Hosker (Italian) and Dr Atherton (English) – shared some of the strategies they adopt to sustain high levels of motivation in their lessons. Here are just some of their ideas…

Set high expectations: Our pupils respond well when their teachers set high standards in terms of classroom routines and completion of work. They thrive in a secure learning environment in which they know their work will be checked fairly and rigorously.

Let them know you care! Effort levels peak when pupils know their teacher really cares about them. But girls – be warned! – caring is not necessarily fluffy. As Ms Thabet says: “When I care about you…poor you!” This is because she will be on your case! She will not give up! She will always follow things up, and she will be uncompromising with her rules and standards: “That’s my ‘brand’ of caring, and my pupils recognise it.”

Develop a good rapport: Everyone appreciates being noticed and appreciated. A simple “How was your weekend?” from the teacher, or noting an achievement in an extra-curricular activity, can be very affirming and motivating for any pupil.

Be invested in your feedback: Pupils need to feel that their teachers are invested in them. Individually tailored and detailed verbal praise or constructive criticism can convey this, as can prompt feedback about a task (always appreciated!).

Make it real: Pupils often engage best with a topic if they can relate it to the real world. In politics, for example, it can powerful when girls bring their ideas and reactions to current events into classroom discussions. Similarly, sharing aspects of Italian culture can hook them into learning related vocabulary and grammar more effectively. As Dr Hosker advises: “Know your pupils and tap into their preferences.”

MR GODFREY (DEPUTY HEAD) SHARES SOME OF THE WAYS TEACHERS AT DOWNE HOUSE MAXIMISE THEIR PUPILS’ MOTIVATION TO LEARN.

Give pace to all lessons: All subjects have at least some lengthy topics which can be intimidating. Breaking them into manageable chunks, with regular review, assessment and praise, is an effective way to make progress. Some topics are inevitably less engaging than others: but if the teacher is seen to be looking forward to teaching something ‘boring’, it ceases to be boring!

Active is better than passive: Our girls prefer to be active participants rather than passive observers. It is important to give them time to think and to interact with each other during lessons. A variety of tactics within the same lesson – for example, an interactive start, then some quiet thinking time, followed by an explanation or exposition from the teacher –can be a particularly good tactic.

Learning is a two-way process: It is important to ‘model’ learning to our pupils: we can learn from them. It is affirming for a pupil when they bring their own knowledge or experience into the classroom and share it with their teacher and fellow pupils. It could be something they have seen in the news or read in their spare time. As Mrs Barnard says: “When this happens, let them know that you are enjoying learning with them.”

Clarity is important: When introducing new concepts, it is important to take sufficient time to ensure that no-one falls behind. If necessary, take more time than you had planned. Our pupils appreciate clear explanations and the time to practice and check their own understanding. This is key to building confidence and independence. Some will learn faster than others, so it is important to have both reinforcement and extension activities available to enable pupils to work at their own pace before moving on to new topics.

Tech is great! Everything in moderation, but there is so much software that can provide variety, texture and differentiation to the learning process. Multiple choice questions on Kahoot are very popular, and OneNote and other platforms are great for collaboration between pupils and other interactive learning methods.

Mistakes are fine and important: It is essential for pupils to engage with their own mistakes – to feel OK about making them, and to be able to recognise them and work through them. It can be highly effective for pupils to practice and to check their own answers with a sheet of solutions. They need to know they can solve problems without their teacher. It can take effort working through mistakes, but the rewards and confidence from getting there in the end are powerful.

IT IS ESSENTIAL FOR PUPILS TO ENGAGE WITH THEIR OWN MISTAKES – TO FEEL OK ABOUT MAKING THEM, AND TO BE ABLE TO RECOGNISE THEM AND WORK THROUGH THEM.

MISS KAYLEIGH BONWICK (GRADUATE SPORTS ASSISTANT) EXAMINES THE RESEARCH UNDERPINNING THE BENEFITS OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING, WITH A PARTICULAR FOCUS ON ITS USE IN YOUTH ATHLETIC PERFORMANCE

Strength and conditioning (S&C) is a relatively modern branch of sport science, yet traditional, out-dated practices and anecdotal myths mar its use and effectiveness in youth athletic performance. In a period when youth obesity and inactivity is rife and the promotion of youth physical activity is at an all-time high (Aubert et al., 2018; Guthold et al., 2020), why is youth S&C viewed so negatively, and what does the research and literature suggest for the use of S&C training for the physical and mental wellbeing of youth populations?

Perhaps the largest concern of mal-informed stakeholders of young people is that resistance training can stunt growth and increase the risk of injury occurrence in children. An early Japanese study indicated that heavy labour (i.e. lifting) has a negative impact on the stature of children, and this is a possible reason for the adverse perceptions of the use of resistance training with young athletes (Kato & Ishiko, 1964). Furthermore, Docherty et al. (1987) and Vrijens (1978) reported ambiguous results relating to the benefits of resistance training in the physical development of preadolescent boys, thus creating a more unfavourable view on youth resistance training. However, as scientific research and understanding have advanced, modern insights indicate the importance of developing muscular fitness throughout childhood and adolescence (Pietzsch & Wallis, 2020). It is now

understood that weight-bearing and resistance-based exercise in youth populations can elicit improvements in bone formation (Faigenbaum et al., 2009), bone mineral density (Gunter et al., 2008), increases in muscular strength (Behringer et al., 2010; Faigenbaum et al., 2011), greater body composition (Schranz et al., 2013), more refined motor skills (Cattuzzo et al., 2016; Duncan et al., 2018) and a reduced risk of injury (Faigenbaum et al., 2009). It is therefore vital that traditional ways of thinking are challenged, by providing education to as many people as possible on the purpose and benefits of S&C training.

In 2012, the United Kingdom Strength and Conditioning Association (UKSCA) released their position statement on youth resistance training and they concluded that the use of resistance training by children and adolescents has sizeable physiological and psychological benefits (Lloyd et al., 2012). Notably, the UKSCA also state that training programmes must be consistent with the individual needs, goals and abilities of each young athlete, appropriate equipment and progressions must be provided and therefore, a knowledgeable and qualified professional is required to facilitate such training. As such, there exists no real minimum age recommendation for young athletes to commence resistance training, if the individuals taking part can follow coaching instruction. In addition, seminal work by Lloyd and Oliver (2012) and refined work by Lloyd et al. (2015) introduced The Youth Physical Development (YPD) Model and The Composite Youth Development (CYD) Model. These models provide a live training framework for youth physical development that allows S&C coaches to structure their training appropriately in relation to the chronological, physiological and social development of their athletes. Moreover, Faigenbaum and McFarland (2016) offer the acronym PROCESS (progression, regularity, overload, creativity, enjoyment, socialisation and supervision) and they suggest that these are the principles with which youth S&C should be approached. Training

goes beyond ‘getting strong’ and the importance of creativity, enjoyment and socialisation for young athletes should not be forgotten, regardless of their physical and sporting ability.

At Downe House, S&C training occurs throughout the week, primarily with the Sport Scholars and select highlevel performers who are not part of the Scholarship Programme. Sessions take place in small groups, with everyone completing 1–2 sessions per week and exercises are updated half-termly, to maintain novelty. Using the YPD/CYD Models as a guide, programmes are designed with a focus on strength training and development. Once a sound strength base has been formed, the programmes are adapted to include power training, and a small amount of hypertrophy, as subfocuses. With this approach, pupils receive a strength stimulus all year round, as well as the opportunity to enhance other essential physical qualities as they advance. Furthermore, timetabled PE lessons, a mobility session and a conditioning session provide organic exposure throughout the week to develop qualities such as agility, speed and mobility. Additionally, all our Remove and LIV students are exposed to S&C through their three-week PE rotations, and they receive lessons that introduce the training of acceleration and deceleration, reaction time and balance and stability, delivered through fun games and activities.

To summarise, it is now generally considered safe and best-practice for youth populations to undertake S&C training throughout their physical development, irrespective of their sporting ability. Such training leads to a host of physical and performance benefits, which in turn can improve mental wellbeing. S&C at Downe House is still evolving, but we endeavour to always maintain an athlete-centred approach and base our practices on up-to-date research and evidence, balancing the art and science of S&C coaching to support all our pupils as best we can, not just our high level performers.

THE USE OF RESISTANCE TRAINING BY CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS HAS SIZEABLE PHYSIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL BENEFITS (LLOYD ET AL., 2012).

Being a classroom teacher is no mean feat; we are constantly juggling with so much, and it is not surprising that the effectiveness of feedback can be overlooked. As a school, we have been spending a lot of time looking at effective feedback, and I have witnessed so many of my colleagues do such a great job with this. However, I think that work can still be done on ensuring that the feedback is taken on board; after all, we have all put in so much effort into our marking as well as other forms of feedback, and we would certainly want out students to benefit from the feedback. Hattie and Gan (2011) wrote that “we know much about the power of feedback, but too little about how to harness this power and make it work more effectively in the classroom”, which to some extent, I agree.

Realistically, how many of us have an excess amount of time to investigate whether our students are learning from the feedback, and are

MRS SANDY CLARKE (TEACHER OF CHEMISTRY) CONSIDERS THE ROLE THAT FEEDBACK PLAYS IN HER TEACHING AND ITS VITAL IMPORTANCE, OFFERING PRACTICAL TIPS TO TRY OUT IN THE CLASSROOM.

subsequently making progress? I think that despite our best efforts, sometimes we just hope for the best (we hope that we have equipped the students with the right skills to make use of the feedback appropriately). In addition, depending on the feedback, it is not always measurable. I find that at the start of the academic year especially when taking a new class, spending time to establish a routine, such as at the start of the lessons when students are entering the classroom, it is worth asking students to read and respond to prep feedback, and make sure we check that they have made corrections. It might take a few weeks to establish this routine, and we might be losing 5–10 minutes per lesson for those few weeks, but soon they will have a habit of responding to the feedback. If students know that we check and re-check their work, they tend to feel obliged to do the task (it is particularly easy now with One Note, as they will not misplace a piece of work and forget about it). After a few weeks, you will find that students automatically respond to feedback. The magical thing is that I am now noticing many students automatically respond to feedback in their own time and I don’t need to allocate lesson time for the task. Hopefully, this is a skill or a culture that we can instil in them. It is a great feeling that they are willing to spend time to work on your

feedback even when you don’t ask them to!

For me, the second challenge is also what to do with the corrections afterwards. It might need adapting for some subjects, but I strongly believe that it is essential for them to learn from the corrections, and I ask students to add corrections to their revision notes, so when they revise, they can incorporate the corrections into their revision.

In my opinion, feedback should be a two-way communication. How do we know whether our initial feedback is working? How do we know if students are making progress? We do this all the time, we assess them verbally and on paper. Post COVID restrictions, now that we are back in the classroom, we have a larger variety of ways to gain feedback from the students. Recently, I have been doing revision classes with the exam groups, and they are so tired of doing yet more and more past papers. Whilst past papers are key to improve on application skills in a subject like Chemistry, just to give them a slight ‘break’ and a variety, I have used ‘loop game’ which works in a similar way to Dominoes.

Students seem to love this activity as it provides immediate feedback for them, and also for me to know

whether they have learnt from the feedback, or if there are specific gaps in their knowledge. Of course, we need to design the ‘loop game’ or in fact any activity (such as an effective low-tech weekly quiz on paper), to make sure it gives effective feedback to the students and for us, not just a bit of fun! Like many colleagues, I also try to use different online games and platform such as Kahoot, Blookat, and UpLearn. They key is to utilise something that will give us feedback on whether our students are improving as a consequent of our feedback.

Koenka et aI. (2021) found in their study that there is a positive correlation between good quality feedback and both academic achievement and motivation. I also believe that effective feedback (mutual) is not only important for students making progress, but also for us to build a closer rapport with them. A few students have told me that they like that we care about following up on actions from the feedback, they feel like we care about their learning. In a Parents’ Meeting, a couple of parents have commented that they very much appreciate that when AfDs are followed up on. So, all this following up on feedback is timeconsuming, but once we have set up expectations and a routine, it will pay dividends.

THERE IS A POSITIVE CORRELATION BETWEEN GOOD QUALITY FEEDBACK AND BOTH ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND MOTIVATION.

By no means a new idea and gaining particular prominence during the boom of Dylan Wiliam’s AfL years, peer assessment, in broad terms, describes an assessment routine where one student assesses or provides feedback on the work of another student.

There are many reasons to implement this strategy into our teaching, not least the fact it frees up the teacher to provide more individual help to those who need it, but, if deployed without careful attention, it can also create far more misconceptions and misunderstandings than it might address. This issue of The Enquiry will outline some strategies to help make sure peer assessment is being implemented as effectively as possible.

But first, what are some of its benefits and why should we think about using it as a classroom strategy?

It can help to improve student understanding of success criteria as they begin to internalise what success and excellence looks like, or doesn’t look like, in a given task or topic.

It could help to reduce teacher workload as students are, in Wiliam’s phrasing, being ‘activated as agents for their own learning’ and so feedback is not being funnelled through one teacher. Of course, this relies on the feedback being provided being of high quality, but more on this later.

It can help to encourage and promote exploratory and dialogic talk between students, which the research of Mercer and Sams (2006) has suggested can be very effective for student learning and progress.

It provides students an opportunity to evaluate and compare their own work with that of peers, helping to better grasp and reflect on gaps or areas for development. Indeed, Lundstrom and Baker (2009) have concluded that assessing a peer’s written work was more beneficial for their own work than that of the peer.

Following the above, peer assessment might best be understood not even so much as a feedback strategy but a metacognitive one where the benefit of the task is in helping the assessor to develop better self-regulation strategies and come to a deeper understanding of how their own work could be developed and improved. This is part of the argument made by Topping in their 1998 study of peer assessment.

Peer assessment may also improve the communication of feedback as students may use more accessible language than that of a teacher whose comments, inadvertently, may be difficult to decode given they are necessarily written from a perspective of expertise, connecting to the

DR ANDREW ATHERTON (DIRECTOR OF LEARNING AND RESEARCH) EXPLORES SOME OF THE RESEARCH UNDERPINNING PEER ASSESSMENT ARGUING IT IS AN INCREDIBLY VALUABLE TOOL TO USE IN THE CLASSROOM, BUT OFTEN VERY TRICKY TO DO IT WELL.

THERE ARE MANY REASONS TO IMPLEMENT THIS STRATEGY INTO OUR TEACHING, NOT LEAST THE FACT IT FREES UP THE TEACHER TO PROVIDE MORE INDIVIDUAL HELP TO THOSE WHO NEED IT

cognitive phenomena of the ‘curse of knowledge’. In other words, we often find it difficult to remember what it was like to be a novice. As a related note, this is one reason why written comments may not always be the most effective means of delivering feedback.

As Liu (2016) has argued peer assessment may also reduce any potential negative feelings of being evaluated and judged by an authority figure, making students perhaps more willing to attend to the feedback. However, as explored in more detail later, the opposite could be true where students feel more judged by friends or students are less willing to provide feedback for fear of upsetting a peer.

It is clear then that there are many benefits to peer assessment if incorporated into routine classroom practice and perhaps Kit Double makes this case best when concluding in his 2019 paper that his study ‘suggested that the effectiveness of peer assessment was remarkably robust across a wide range of contexts’.

However, it is also very true that peer assessment could go wrong and be utilised in such a way as to dampen or even hinder student learning. What, then, could most obviously go wrong when using peer assessment?

Listed below are some of the factors that could contribute to peer assessment not being effective or leading to greater student misconception. If using peer assessment, what should we be wary or mindful about?

The feedback students provide to their peers could be inaccurate, unhelpful or lead to greater misunderstanding. If Student A does not understand or has a particular misconception then, without teacher guidance, this could be passed onto Student B, thus hampering student progress.

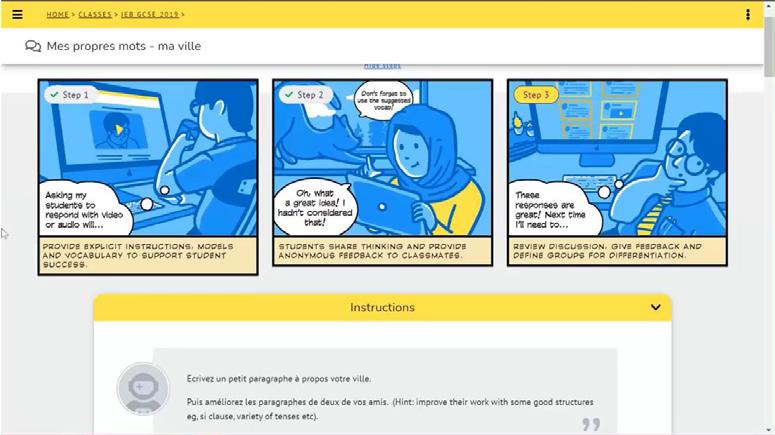

The above scenario is most likely to happen if teachers do not provide adequate explicit instruction, guidance or training. The least effective mode of peer assessment would be for students to assess each other without any prior kind of training from the teacher. As both Boon (2015) and Topping (2018) have pointed out such training is crucial to the success of peer assessment.

Students do not have access to some kind of model or exemplar before beginning peer assessment and as such they may not have a concrete baseline against which to provide feedback.

Students are encouraged to use the specialised language of the mark scheme when delivering peer feedback, which may be difficult for them to decode or understand, even with training, as these documents are written for specialists. The language students use should instead be jargon-free and translated by the teacher into something less exam-focussed and a more concrete success criteria. The potential pitfall here is viewing an examination mark scheme as a formative document rather than a summative one written for specialist examiners and not students.

Peer assessment could play into and against relationships within the classroom that are perhaps not immediately visible to the teacher, meaning that students may not wish to provide honest feedback for fear of upsetting their friends or disturbing a group dynamic (Dochy 1999). As such, the feedback can often result in unhelpful and vague comments along the lines of ‘this is excellent’ or ‘I really loved this’. Building a very specific and granular success criteria into the task can help with this.

As a general point before looking at more specific strategies, the success or lack of it when it comes to peer assessment is in large part

determined by the kind of modelling and training students receive. Asking students to peer assess, even if something seemingly trivial, without some kind of explicit direction, will likely lead to further misunderstanding. Berg 1999, Min 2005, Gielen 2010 have all emphasised the important of teacher modelling prior to beginning peer assessment. With this in mind, what are some practical strategies we could use to help make peer assessment effective?

Model the specific process of peer assessment on a fictional student before asking students to do it so that they can see from the teacher what effective peer feedback looks like without any anxiety given the target is fictional. Teachers could also ask for student input at this stage, which again will eliminate any perceived wariness about upsetting friends.

Provide lots of scaffolding to help students be as specific and granular as possible when providing feedback to their peers. This might take the form of checklists of what to be looking for, a student-friendly rubric to refer to, a model response to compare against. The more specific and targeted this scaffolding is the less likely students are to offer vague and potentially unhelpful comments.

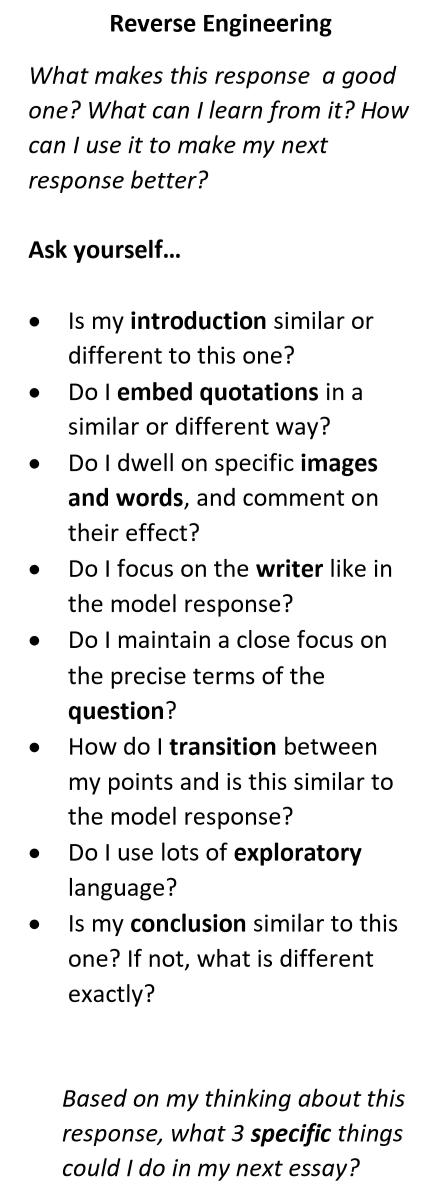

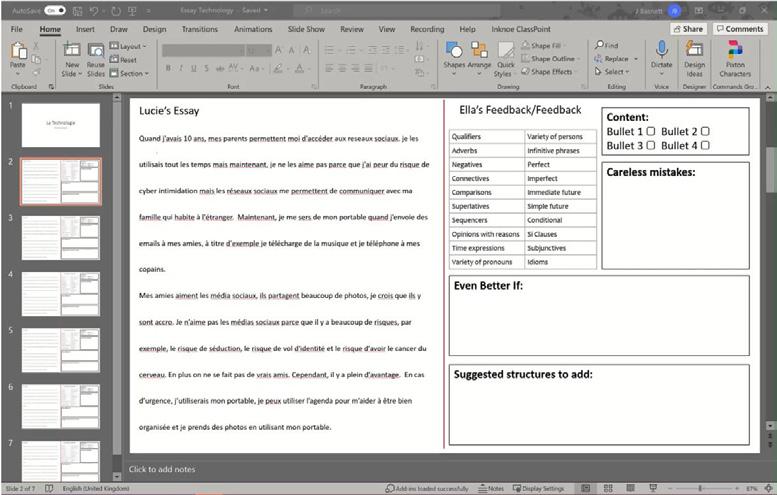

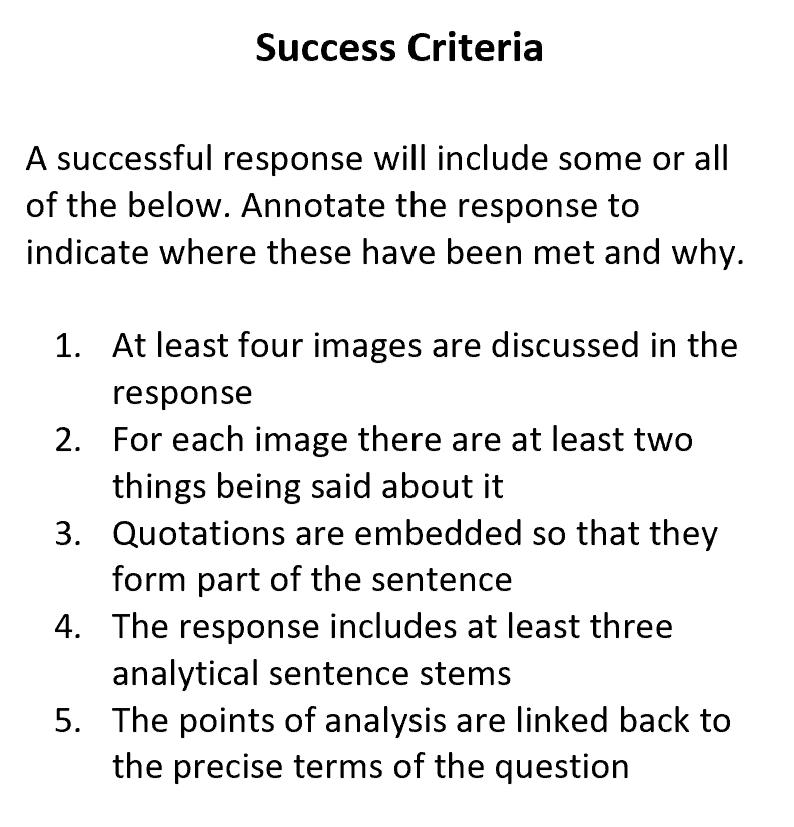

An example of the above kind of scaffolding is featured (1 - left), where students are offered a set of specific questions to help guide their thinking when looking at peer work or indeed their own work. This could be connected with a model response so that students are comparing peer work against the concrete example of a model and then using the questions to help ensure their feedback is as specific and task orientated as possible. Provide a concrete and granular success criteria as opposed to a full mark scheme where the success criteria includes the same information as the mark scheme, but in such a manner that removes some of the examspecific jargon (such as assessment objectives) that students may not fully understand and might add an additional layer of complexity. Student feedback could then be anchored to this specific criteria and revolve around the extent to which it has been successfully met. Again, a model example could be provided first to help make the points of the success criteria as concrete as possible. An example of this kind of success criteria is featured opposite (2).

As well as any written feedback that students may provide one another, it can be very useful to provide opportunity for more exploratory and dialogic talk where one student feeds back to the other and explains why they arrived at the feedback they provided. The student being assessed could then explain what specific changes they might make based on this

PROVIDE LOTS OF SCAFFOLDING TO HELP STUDENTS BE AS SPECIFIC AND GRANULAR AS POSSIBLE WHEN PROVIDING FEEDBACK TO THEIR PEERS.

feedback. This kind of interaction will be helpful to both the student providing the feedback and the student receiving.

Peer assessment does not need only to be delivered in relation to a more formal or extended tasks, but could be as effectively, if not more so, completed with shorter tasks or retrieval activities. Examples might include:

Paired quizzing where one student asks a predetermined set of questions provided by the teacher and then checks their partner’s answers against a provided sheet

Paired rehearsal where one student is asked to rehearse a process, cycle, sequence of events or series of ideas and another uses a set of prompts to help provide feedback.

Elaborative/interrogative where one student asks another a series of ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions, again using a prompt sheet to help guide the exchange.

In this short five-minute video Jane shares her thoughts about how to use PPT, Class Notebook, and Verso App, offering lots of practical ideas for using these in the classroom. Downe House staff can access this video here or scan the QR code.

In Lent term 2022, we introduced to colleagues our Learning and Research Council. The L&R Council aims to provide a process for colleagues to engage in a sustained yet manageable project of practitioner research that has a tangible positive impact on their own practice and that of the wider academic staff body.

We currently have six colleagues from a range of departments who have embarked on this process and whose projects are currently well underway, exploring a range of fascinating topics.

The purpose of Practitioner Research is to answer a question about a teacher’s own practice. It is this process of critical reflection and evaluation that is valuable and not whether any designed intervention is ultimately successful.

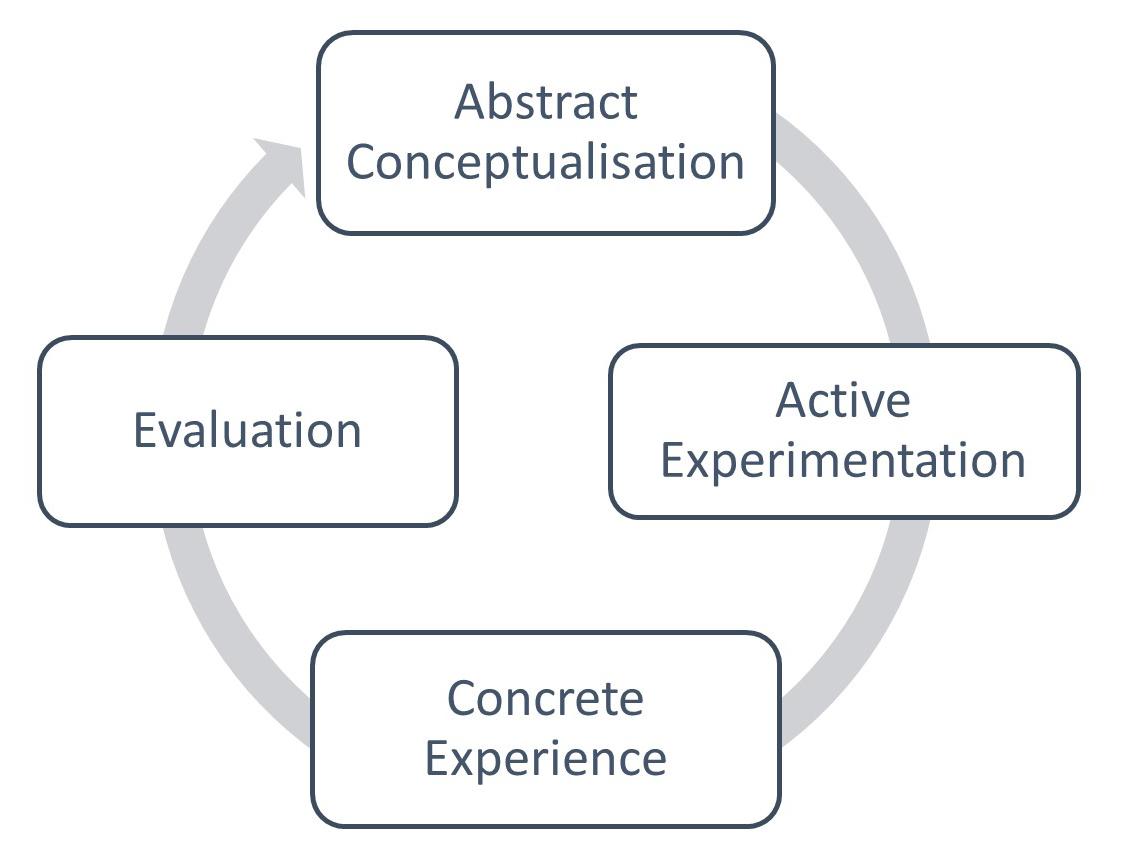

In creating such a model, we are aligning our processes to current research underpinning effective professional development, such as David Kolb’s learning cycle, which involves sustained reflection across four stages, as depicted in the diagram (3):

Here, abstract conceptualisation involves encountering new ideas or theories that might help us to re-evaluate existing knowledge, which then leads to active experimentation in which we discuss and reflect on the practical implication for these new ideas. What might this actually look like in our classroom? In the concrete experience phase, we then adapt and implement the strategies or ideas we have encountered, evaluating as we go how it seems to be working. Finally, the cycle is completed with the opportunity to critically evaluate the changes made in the concrete experience phase, where we consider whether the strategy worked or not and what other changes might be made.

The great benefit to a model such as this is that it encourages engagement with research, but also recognises such research must be enacted in specific contexts and that this takes place

over time. Simply put, it offers the tools with which we can think about something important to our practice, try it out, and evaluate whether or not it works. This is at the heart of what we hope the Learning and Research Council can offer.

Our process begins in Summer Term by identifying an area to examine and beginning to read relevant research around this topic. Then, in Michaelmas Term, colleagues make adaptations to their practice in some fashion and as aligned to the research they have done, looking at what impact it has and whether it works well. Lent Term will then be an opportunity to evaluate and reflect on any findings and consider what to change or implement.

We are hoping to share a lot of updates and findings from these projects in the coming months so watch this space…!

Five Ways to: Scaffold Classroom Dialogue –teacherhead

In this excellent blog post, Tom Sherrington suggests 5 ways to make classroom discussions as effective as possible.

This much I know about… defining the terms used to discuss the school curriculum – John Tomsett

In this post, John Tomsett looks at some of the key ideas underpinning curriculum design. Strategies to Increase Pace – TomNeedham (wordpress.com)

Tom Needham looks at what we mean (and don’t mean) by pace. ‘Include more pace’ is one of the most common pieces of feedback from lesson observations, but what does it actually mean?

Christine Counsell:

The support our middle leaders need if curricula are to flourish – ResearchED Here, Christine Counsell consider how to make best use of middle leaders and Heads of Department in the conext of curriculum design.

Our book of the term, and many more, are available for staff to borrow in the Staff Research Library, situated in the Staff Common Room.

BY OLI CAVIGLIOLI

BY OLI CAVIGLIOLI

Dual coding is becoming increasingly popular as a way in which to embed information in long term memory and this book offers various practical steps and ideas to implement dual coding into teaching.

Aubert, S., Barnes, J.D., Abdeta, C., Abi Nader, P., Adeniyi, A.F., Aguilar-Farias, N., Tenesaca, D.S.A., Bhawra, J., Brazo-Sayavera, J., Cardon, G. and Chang, C.K., (2018). Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: results and analysis from 49 countries. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 15(2), pp. 251–273.

Behringer, M., Vom Heede, A., Yue, Z. & Mester, J., (2010). Effects of resistance training in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 126(5), pp. 1199–1210.

Cattuzzo, M.T., dos Santos Henrique, R., Ré, A.H.N., de Oliveira, I.S., Melo, B.M., de Sousa Moura, M., de Araújo, R.C. and Stodden, D., (2016). Motor competence and health related physical fitness in youth: A systematic review. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 19(2), pp. 123–129.

Docherty, D., Wenger, H. A., Collins, M. L. & Quinney, H. A., (1987). The effects of variable speed resistance training on strength development in prepubertal boys. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 13, pp. 377–282.

Duncan, M. J., Eyre, E. L. & Oxford, S. W., (2018). The effects of 10week integrated neuromuscular training on fundamental movement skills and physical self-efficacy in 6–7-year-old children. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(12), pp. 3348–3356.

Faigenbaum, A.D., Farrell, A., Fabiano, M., Radler, T., Naclerio, F., Ratamess, N.A., Kang, J. and Myer, G.D., (2011). Effects of integrative neuromuscular training on fitness performance in children. Pediatric exercise science, 23(4), pp. 573–584.

Faigenbaum, A.D., Kraemer, W.J., Blimkie, C.J., Jeffreys, I., Micheli, L.J., Nitka, M. and Rowland, T.W., (2009). Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the national strength and conditioning association. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23, pp. 60–79.

Faigenbaum, A. D. & McFarland, J. E., (2016). Resistance training for kids: right from the start. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal, 20(5), pp. 16–22.

Gunter, K., Baxter-Jones, A.D., Mirwald, R.L., Almstedt, H., Fuchs, R.K., Durski, S. and Snow, C., (2008). Impact exercise increases BMC during growth: an 8-year longitudinal study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 23(7), pp. 986–993.

Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M. & Bull, F. C., (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 populationbased surveys with 1.6 million participants. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 4(1), pp. 23–35.

Kato, S. & Ishiko, T., (1964). Obstructed growth of children’s growth due to excessive labour in remote corners. In: K. Kato, ed. Proceedings of International Congress of Sports Sciences. Tokyo: Japanese Union of Sport Sciences, p. 476.

Lloyd, R.S., Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D., Stone, M., Oliver, J., Jeffreys, I. and Pierce, K., (2012). UKSCA position statement: Youth resistance training. Professional Strength & Condtioning, Issue 26, pp. 26–39.

Lloyd, R. S. & Oliver, J. L., (2012). The youth physical development model: A new approach to long-term athletic development. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(3), pp. 61–72.

Lloyd, R.S., Oliver, J.L., Faigenbaum, A.D., Howard, R., Croix, M.B.D.S., Williams, C.A., Best, T.M., Alvar, B.A., Micheli, L.J., Thomas, D.P. and Hatfield, D.L., (2015). Long-term athletic development-part 1: a pathway for all youth. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(5), pp. 1439–1450.

Pietzsch, F. & Wallis, J., (2020). Coaching children and youth: Building physical foundations.

In: J. Wallis & J. Lambert, eds. Sport Coaching with Diverse Populations: Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 24–37.

Schranz, N., Tomkinson, G. & Olds, T., (2013). What is the effect of resistance training on the strength, body composition and psychosocial status of overweight and obese children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 43(9), pp. 893–907.

Vrijens, J., (1978). Muscle strength development in the pre and postpubescent age. Medicine and Sport, Volume 11, pp. 152–158. 05.

Hattie, J., & Gan, M. (2011). Instruction based on feedback. In R. E. Mayer & P. A. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning and instruction (pp. 249–271).

Koenka, A. C., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Moshontz, H., Atkinson, K. M., Sanchez, C. E., & Cooper, H. (2021). A meta-analysis on the impact of grades and comments on academic motivation and achievement: A case for written feedback. Educational Psychology, 41(7), 922–947.