6 minute read

Fishing and the Future

After the cod collapse, is cod jigging still a rite of passage?

by Jenn Thornhill Verma

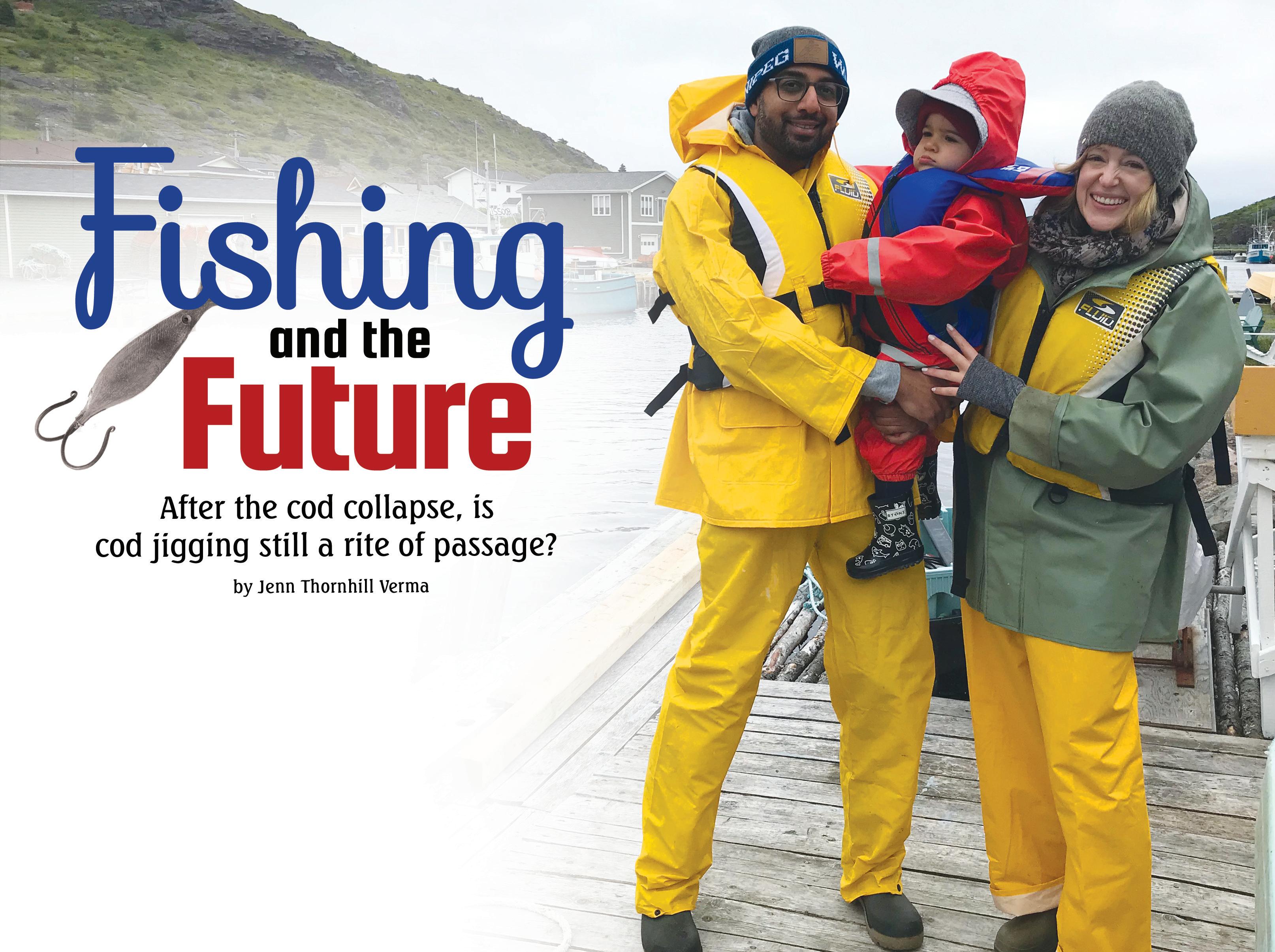

About a mile-and-a-half off the coast of Petty Harbour, NL, we’re dropping anchor, 26 fathoms deep. The fishfinder, an instrument for locating schools of fish, confirms what captains Leo Hearn and Kimberly Orren already know: the cod are plentiful. In their 22-footer, we have everything we need for an afternoon of cod jigging. We’re suited in head-to-toe raingear, rubber boots, wool hats, waterproof gloves and life-jackets – clothing signalling late summer in a place accustomed to late, short summers. We also have a bucket of freshly caught capelin we’ll use for bait; a few single-hook jiggers with steel weights on 250-pound test lines; and an empty fish tub for today’s catch.

This third Sunday of July 2019 marks the first cod-jigging trip for two of the five of us on board. At 20 months, not surprisingly, my daughter, Navya, has never fished a day in her life. I’ll consider the “fishing” she does today an activity best placed in air quotes, much like when she plays “soccer” or goes “swimming.” And yet, Navya gets what’s happening, bright-eyed and repeating “fish” whenever we show her the capelin. My 39-year-old husband, Raman, is the other newbie. Raman is a firstgeneration Canadian; his parents emigrated to Canada from India. While I spent my childhood in Newfoundland running freely outdoors, Raman tells me he often spent his in New Brunswick running mathematical equations indoors. He thinks summertime math is a rite of passage, but we’ll start Navya off with cod jigging today.

As the boat bounces on the Atlantic, Raman holds Navya tightly. I smirk, thinking it looks like he’s hugging an ocean buoy; only Navya’s face is visible, the rest of her body swallowed up in bright red gear, perhaps a size or two too big, her hood and her life jacket.

I turn my attention to Leo, who offers a quick lesson on baiting. One can jig a cod without bait. In fact, that’s why the jigger, designed to look like capelin, was introduced by merchants – so fishers could catch cod no longer taking bait. If fishers could guarantee catch, then merchants could guarantee incomes. But fishing without bait eliminates a natural equilibrium between fishers and fish. It’s one of the reasons I chose Kimberly and Leo’s non-profit, Fishing for Success, for today’s family fishing excursion. They teach families like mine our ancestral and traditional fishing knowledge and skills, and they do it in a way that conserves the fish and protects the environment. “There are no gill nets here for three miles,” Kimberly had told us as we headed out to the fishing grounds. Petty Harbour-Maddox Cove has a protected fishing area, having first banned trawls (longlines) in 1961, then gill nets in 1964.

I follow Leo’s instruction, holding the capelin in my left hand, then piercing its eye with the jigger’s hook in my right. I guide the hook along the capelin’s spine until the fish curls around the hook. Then I drop the jigger in the water, allowing the line to pass over my open hands, as the steel weight helps the jigger plummet to the depths below the deep blue rug. Then, I gently hold the line, awaiting that distinctive tug. Within seconds, the line is taut against the gunwale (sometimes called gunnel, the rail of the boat). I pass my one hand over the other pulling in the line, at the same time noticing marks along the gunwale, evidence of many lines pulled many times. Then, a glint emerges to the surface. I haul my cod up and over the gunwale.

“Fish, fish!” Navya says excitedly, emphasizing the shh the way toddlers do, awkwardly making their way around new word sounds, uncertain where to place the emphasis. Raman tries his hand at jigging and before we know it, we are hauling in cod for cod, in a way that’s almost comical. Just as one of us catches one, the other has one on their line. Navya’s “fish, fish” repetition becomes the perfect narration. The unfolding scene reminds me of an Ernie and Bert sketch from Sesame Street when Ernie calls “Here fishy, fishy, fishy” and fish come flying into the boat.

Should we fish cod at all?

It's easy to get caught up in the excitement, but I know cod aren't as plentiful in the Northwest Atlantic as they appear to be today. It's 27 years after the collapse of northern cod and the July 1992 shutdown of its fishery, better known as the cod moratorium. That moratorium remains in effect today, but the federal government, which manages the fishery, allows a small commercial and recreational cod fishery (a.k.a. the food fishery).

In August, a new union hoping to represent inshore fishers, the Federation of Independent Sea Harvesters of Newfoundland and Labrador (or FISH-NL), called for an end to all cod fishing apart from the commercial fishery. The call comes after a new paper by fisheries scientists George Rose and Carl Walters finds overfishing played a greater role in the collapse of cod and its slow rebuilding than originally thought. A few years ago, other work by Rose and Sherrylynn Rowe found cod making a comeback (in an area called the Bonavista Corridor on the northeast coast of Newfoundland), but that comeback didn’t play out. And yet, Fisheries and Oceans Canada continued to increase the landing limits for cod in the years that followed. More recently, a federal fisheries scientist reported a “highly probable” near future extinction of cod in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

This information might lead one to reasonably ask: Why fish Newfoundland and Labrador cod at all? But I don’t think the route to conservation is an outright fishing ban. To protect and preserve the fish, or any species, I believe we need a healthy relationship with them.

History tells us that traditional fishing approaches like baited hook and line are sustainable (the fish bite when they’re hungry) and ecological (this approach leaves no “ghost fishing gear” or microplastics behind). Of course, we must fish within reasonable limits – something we hadn’t done a particularly good job at leading up to the moratorium. Two fisheries scientists hypothesized that more cod were commercially fished from the Northwest Atlantic in the 15 years between 1960 and 1975, than during the 250 years between 1500 and 1750. Social enterprises like Fishing for Success, a small-scale fishery operation, help maintain links with history while allowing us to enjoy the benefits of fishing for generations to come.

The end of the day

Back in the boat, we have our 15 fish – the daily limit for a boat of three or more recreational fishers – so Leo hauls up anchor and Kimberly sets a course for harbour. I’m sitting at the stern, my arms wrapped around our living ocean buoy. This vantage point allows Navya to see a female fishing captain at the helm. While there are fewer fish and fewer harvesters and processors, the fishery has never been more profitable. A commercial fishing career remains viable, though there are more hoops to jump through than ever before – being female in a male-dominated industry is only one of them.

We pull up next to the red ochre fishing stage. Inside, the Fishing for Success crew have prepared a pot of coffee, ginger cookies, partridgeberry loaf and partridgeberry jam. The coffee helps, but real warmth will come with the salt beef and cod fish stew simmering on the stove in the back corner of the stage. Yet another reason to enjoy the food fishery: to put fresh, local food on our plates. In a province accustomed to shipping most of its food in from elsewhere, this feels like a luxury, but it need not be the case. Newfoundlanders and Labradorians have fresh seafood at our oceanfront doorsteps. So long as we pay respect to the fish through sustainable fishing approaches, we can enjoy these simple luxuries for generations.

As Leo fillets the cod, I try my hand at a traditional Japanese fish print. Before photography, fishers made prints like this to record their catch. Using acrylic paints that can be washed off so the cod may be used for food, I paint my canvas in bold shades. The resulting prints appear as magic cod – and they ought to be, given it marks Navya’s first cod jigging trip at a time when one can’t help but wonder how many more trips we’ll have like this. We hold up the print for a family photo. Before we can pour a bowl of soup, Navya is already fast asleep in Raman’s arms.

Jenn Thornhill Verma is the author of a new book, Cod Collapse: The Rise and Fall of Newfoundland’s Saltwater Cowboys.