5 minute read

Island in the Sun

Fire Island has weathered all kinds of adversity, and is stronger than ever.

by Mike Hammer photography by Isaac Namdar

Advertisement

FIRE ISLAND, a 32-mile-long barrier island off the south shore of Long Island — is no stranger to both glamour and adversity. It is an island of 17 unique communities and over 4,000 homes and it is famous for, among other things, being a go-to destination for the LGBTQ community. It has also been a home and escape for writers, artists, and fashionistas alike, including W. H. Auden, Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks, Richard Avedon, Andre Leon Talley, Calvin Klein, and Angelo Donghia among many others.

Though Fire Island’s history stretches all the way back to the Indigenous communities that called it home, in the 1980s it was synonymous with the beginning of AIDS crisis. The Pines and The Grove were emerging as gay communities in the 1970s, when the party came to a screeching halt. Community residents recall the seemingly endless days of losing friends, tending to the sick and dying, and planning funerals. Activist Larry Kramer began the Gay Cancer Fund in 1981 by collecting money to help people

AERIAL VIEW The Fire Island ferry brings summer visitors and residents alike to the barrier island off the coast of Long Island.

suffering from the disease in The Pines and The Grove, and a few months later he became the co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), one of the earliest organizations to focus on the disease. The crisis that longtime residents lived through served to tighten the community in a shared bond of surviving adversity.

More recently, a massive fire consumed the Pavilion dance club in 2011, and dealt a devastating blow to the gay community. Pines resident Jon Wilner said at the time, “For anyone who lives or rents here, they feel like the Pavilion was their building. It represented their lifestyle, and it was the place where they could celebrate it.”

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy wreaked havoc on the island, severely depleting its beaches and destroying more than 200 homes. Summer visitors craving the glistening shoreline and party atmosphere stayed away. A massive rebuild was needed and for some, it was too much

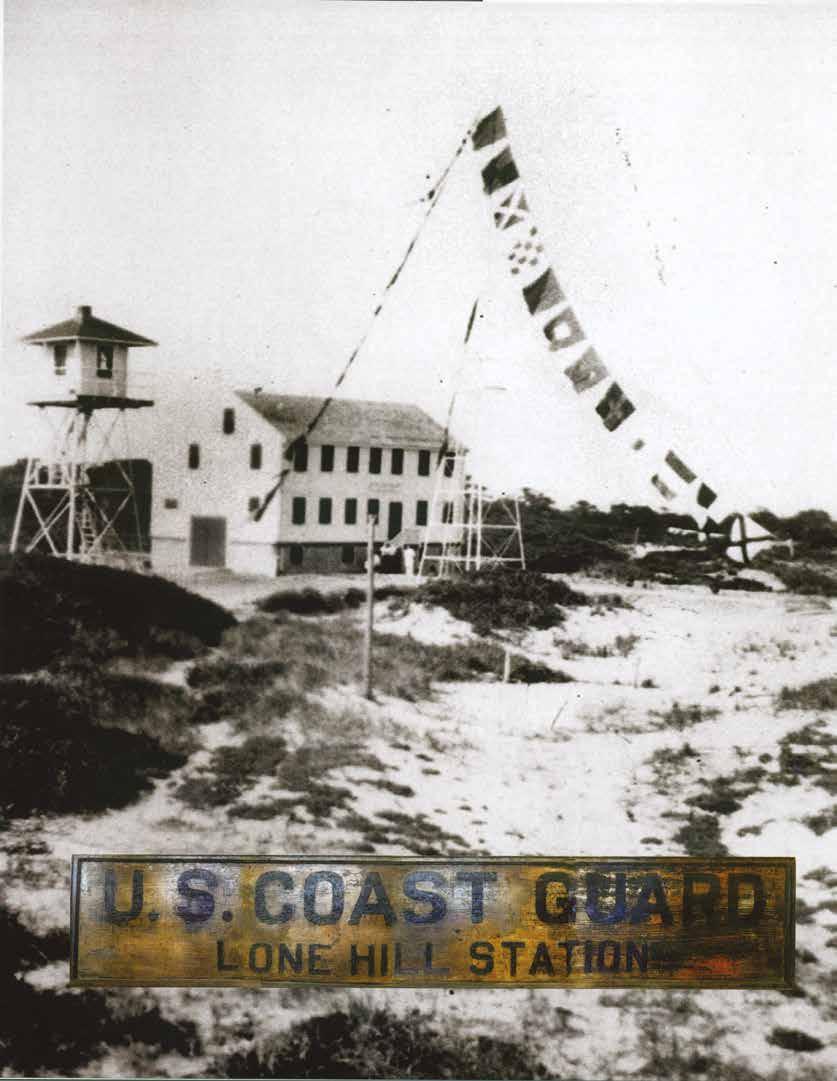

NEW LIFE In 1956, the Coast Guard station was sold to the Fire Island Pines Property Owner’s Association, which then sold shares to the community. The Community House was rebuilt and included a stage and a medical care center. In 1994, the architectural firm of Bromley Caldari Architects won a contest to redesign the building, and in 2007 the new, modern structure was completed and named Whyte Hall after famous resident, John Whyte.

to endure. “There was so much damage from Sandy — both to the homes and to the beaches,” says Joel Robare, a longtime Fire Island resident. He believes that a new kind of Fire Island rose from rubble. “Oddly, all of these tragedies have served to bring new life and permanence to what was once exclusively a summer getaway.”

Robare continues, “I started coming here about 10 years ago and I’ve noticed an incredible evolution. Many people are looking at this as a place to put down roots. It’s no longer simply a party destination.”

After Sandy, those committed to a future on the island remained, and those who left were replaced by a more diverse population which set about rebuilding. Architect and longtime resident Scott Bromley says, “Many of the new people saw a greater potential for year-round homes, and those who were rebuilding saw the opportunity to winterize their homes. Suddenly, people were seeing Fire Island as a place to put down real roots.”

After the Army Corps of Engineers completed a massive 281 million dollar beach replenishment project, the Island seemed reborn with a new spirit. “Fire Island was always a slice of paradise just a little more than an hour from Manhattan,” says Henry Robin, the recently-minted president of the Fire Island Pines Property Owners Association (FIPPOA). “Now it offers what just might be the most beautiful beach in the world, and the draw has never been stronger.”

Just weeks after the beach project was completed last year, the island was slammed by another natural disaster — the COVID-19 pandemic.

But Robin says that tragedy has lifted the community to remarkable new heights. The Property Owners’ Association estimated that about 200 of the approximately 500 homes in The Pines were occupied during the winter months. “The recovery efforts from Sandy brought the many communities of the island together to restore the natural beauty that makes this place so unique. And now the pandemic has made people more aware that it’s a place they can enjoy year round.”

“It’s as safe here as it is anywhere,” says Diane Romano, president of the Cherry Grove Community Association, adding that “the people in Cherry Grove have been really great at implementing social distancing.” The common theme among the island’s devoted residents is that tragedy has never brought them to their knees. Romano says, “The tragedies brought us all closer together. This is a cohesive community with people who really care about each other.”

Through all of its challenges, Fire Island continues to evolve. Walter Boss, a builder and resident of The Pines says, “Let me sum it up in four simple words: rich history, bright future. The Pines has been built through dedication and with respect for its heritage. You can’t move forward successfully unless you respect where you have been. The Pines is extraordinary, there is no other place in the world like it. As a building, it’s my goal to preserve and enhance the natural habitat.” DT

A PLACE TO GATHER The Community House began life in 1854 as a lifesaving station, and in 1900 it was taken over by the Coast Guard and called Lone Hill Station. During World War II it served as a base to patrol the beachfront.