9 minute read

10 WOMEN ARTISTS YOU SHOULD KNOW

Every period of the modern age is shaped, defined and understood by the artists working at the time. What cultural, political or economic shifts occurred during the period? Where did people travel? What literary or religious subjects resonated with contemporary audiences?

These questions and more can be answered by looking at art. However, because artistic pursuits were often unavailable to women and other marginalized groups, we are at times left with only half the picture. Works by women, artists of color, and queer artists provide us with important counterbalances in art history.

Advertisement

Often working outside the academic sphere, these artists experimented with different styles, media and subject matter that lend us even greater understanding of the way certain events impacted society.

Now more than ever, it is vitally important that we recognize the achievements of women artists -- many of whom worked alongside some of the best-known artists of their time with little or no recognition. Doyle is pleased to offer a number of excellent works by women in the auction of Important Paintings on Wednesday, May 20, 2020, and to acknowledge the importance of a diversity of viewpoints in understanding the world around us.

Martha Walter

Lot 1. Martha, Walter American, 1875-1976 Pink Cheeks Signed Martha Walter (ll) Oil on canvas 26 x 21 inches (66 x 53.3 cm), Provenance: Hammer Galleries, New York C $8,000-12,000. Estate of Laura M. Mako

Noted for her portraits of young children, Philadelphia native Martha Walter (1875-1976) was an American Impressionist painter who studied under William Merritt Chase. Prompting from her mentor Chase greatly influenced Walter’s bright palette. This she balanced deftly by using black pigment, a rare choice among artists of the day. Walter’s bright, evocative works bring pathos to her subjects – whether they be child immigrants arriving at Ellis Island or plein-air depictions of the French coast. Pink Cheeks shows Walter’s signature palette put to great use, the heavy blues of the chair offsetting the pink dress and cherubic image of the young sitter.

Harriet Whitney Frishmuth

Lot 2. Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, American, 1880-1980 Joy of the Waters, 1917 Signed Harriet W. Frishmuth, dated 1912, and inscribed R oman Bronze Works Inc. on the base Bronze with light green patina Height 61 inches (154.9 cm) Piped for a fountain. Provenance: James Graham and Sons, New York, circa 1970s Private collection. Literature: C.N. Aronson, Sculptured Hyacinths, New York, 1973, pp. 26, 107-09, illus. J. Conner, J. Rosenkranz, Rediscoveries in American Sculpture: Studio Works, 1893-1939, Austin, Texas, 1989, pp. 38, 40-41, 42n13, 191 T. Tolles, ed., American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born between 1865 and 1885, vol. II, New York, 2001, p. 640 J. Conner, L.R. Lehmbeck, T. Tolles, F.L. Hohmann III, Captured Motion, The Sculpture of Harriet Whitney Frishmuth: A Catalogue of Works, New York, 2006, pp. 28, 66, 79n80, 86, 200, 236, 277-78, no. 1917:3, another example illustrated C $80,000-120,000

While a student of sculpture in Switzerland, Harriet Frishmuth (1880-1980) was singled out by Auguste Rodin for praise when the artist visited her classes. Following her return to the US, Frishmuth opened a studio in New York City in 1908. The artist’s decorative and garden sculptures emphasized the natural grace of the female form. Frishmuth often employed Yugoslavian dancer Desha as a model, because the gifted ballerina had an aptitude for maintaining the stylized poses paramount to Frishmuth’s work. The commanding 1917 sculpture Joy of the Waters is emblematic of Frishmuth’s Art Nouveau elegance, its playful subject full of life and motion.

Yugoslavian dancer, Desha

Berthe Morisot

Lot 3. French, 1841-1895 Tete d’enfant: A double-sided work Stamped Berthe Morisot and B. M. (ll) [recto] Pastel and charcoal on light green/gray paper 18 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches (47.6 x 35 cm). Provenance: Fairweather Hardin Gallery, Chicago Charles E. Slatkin Galleries, New York. Literature: Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot, Catalogue des peintures, pastels et aquarelles, Paris, 1961, p. 53, no. 468, illus., fig. 455 C $7,000-9,000. Estate of Patricia Patterson

Though Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) was every bit the talent as the group of Impressionists with whom she exhibited – Renoir, Cezanne, Monet, Pissarro, Degas and Sisley – she nevertheless struggled for acceptance. In a diary entry, Morisot claims, “I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal and that’s all I would have asked for, for I know I’m worth as much as they.” Having later moved on from plein-air painting to interior scenes largely depicting women, children and domestic life, Morisot documented family without crossing over to sentimentality.

The charming pastel work Tete d’Enfant showcases Morisot’s gift for employing white as a means to show dimension. The child’s coy grin sings out, and Morisot’s talent for spare, feathery strokes breathes fullness into her subject. Morisot sadly died at age 54 in 1895, having never shaken the limiting title of “Woman Impressionist.” Nevertheless, she took countless risks within a notoriously alpha-male group of Impressionists. Her fellow artists would secretly, if not publicly, admit that the Impressionist movement would not be the same without her vibrant, thoughtful contributions.

Franciszka Themerson

Lot 5. Polish, 1907-1988 Adagio, 1947 Signed Themerson (ur) Oil on canvas 16 1/2 x 22 3/4 inches (41.91 x 57.78 cm). Provenance: Drian Galleries, London. Exhibited: London, Drian Galleries, A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Franciszka Themerson, Sep. 10 - Oct. 7, 1963, no. 12 C $15,000-25,000

Polish-born British artist Francizka Themerson (1907-1988) created striking abstract paintings, in addition to her revolutionary work in theatre and as an illustrator and filmmaker. Themerson and her husband collaborated on animated films and created the first English translation of Alfred Jarry’s notorious play Ubu Roi, later performed in 1951 at London’s ICA. Each performer wore fabulously bizarre papier-mache masks created by Themerson. This landmark Dada event morphed into a fantastical puppet show, which Themerson would go on to tour for roughly 20 years. Themerson’s Adagio, from 1947, is largely emblematic of work from this period: lyrical, curvilinear forms are rendered in earthy tones with pops of bright color.

"Véritable portrait de Monsieur Ubu" from the 1896 printing of Ubu Roi : drame en cinq actes en prose by Alfred Jarry.

Barbara Hepworth

Lot 6. Barbara Hepworth, British, 1903-1975 Sculpture with Colour, 1968 Initialed B. H., dated 1940 and numbered 2/9, initialed MS (Morris Singer Foundry) and dated 1968 Polished bronze with string on bronze base, from an edition of 9 + AP Dimensions with base 4 3/8 x 6 x 4 1/4 inches (11.11 x 15.24 x 10.79 cm). Provenance: The artist Mercury Gallery, London, purchased from the above, 1969 This work is listed as BH 459. We thank Dr. Sophie Bowness, of the Barbara Hepworth Estate and preparer of the Barbara Hepworth catalogue raisonne, for her assistance. C $50,000-70,000. Estate of Patricia Patterson

Following her stint at the Leeds College of Art, Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) spent parts of the 1930s visiting the studios of Brancusi, Arp and Picasso, which provided crucial insight and focus to the development of her abstract forms. A 1968 bronze contains all the suppleness and grace of the pioneering sculptor’s best-known work. Thin threads connect the curved form to employ the negative space within, creating an object both formidable and delicate. Hepworth energetically pushed the boundaries of how art could be created and exhibited. Challenged by a male-dominated art world, Dame Hepworth simply wished to be known as a sculptor, irrespective of gender. In 50 years of making, the artist created over 600 sculptures.

Hepworth in 1966

Elaine de Kooning

Lot 7. American, 1918-1989 Home, 1953 Signed E. de Kooning (lr); signed E. de K. and Elaine de Kooning, dated 1953 and inscribed as titled on the reverse Oil on Masonite 17 1/2 x 14 inches (44.45 x 35.56 cm). Provenance: Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco [Sale] Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Oct. 27, 2010, Modern & Contemporary Art Auction, lot no. 72045 Purchased from the above by the current owner. Provenance: Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco [Sale] Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Oct. 27, 2010, Modern & Contemporary Art Auction, lot no. 72045 Purchased from the above by the current owner. Exhibited: Elaine de Kooning: Portraits, Apr 3 - May 31, 2003, Hackett-Freedman Gallery, San Francisco C $8,000-12,000

Overshadowed by her husband’s overwhelming fame, Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) was an incredible force in her own right – not only as a tireless promoter of husband Willem’s work, but as an accomplished painter, crucial to the Abstract Expressionist movement. De Kooning was a rare female member of the formidable Eighth Street Club, alongside Clyfford Still, Hans Hofmann and others. Unfazed by the macho New York School artists, de Kooning was the outgoing, gregarious foil to Willem’s gruff, curmudgeonly nature – her brilliance revealed through her regular contributions to ArtNews.

The 1953 work Home is an early example in a series of baseball paintings, a subject she would return to throughout her career. In the work we see the hallmarks of abstract painting connect to the kinetic forms of the sport. Home depicts three figures crowded around home plate, arguing a close play: the umpire with arm outstretched, keeping the catcher from attacking the runner, possibly after an aggressive slide into home plate.

Elaine de Kooning, Lopez and Ump and Baseball #5A, Kansas City, Lou Boudreau. Sold by Doyle for $5,625.

Carolee Schneemann

Lot 8. Carolee Schneemann, American, 1939-2019 Southern Light, 1961 Signed Schneemann and dated 1/61 (ll); signed C. Schneemann, dated 1/61 and inscribed as titled on the reverse; signed Carolee Schneemann, dated 1/61 and inscribed as titled on the backing Oil on canvas 28 x 21 1/4 inches (71.12 x 53.97 cm). Provenance: Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York C $10,000-15,000

A very early abstraction from 1961, Southern Light contains much of the same all-over busyness of Carolee Schneemann’s later work. Schneemann (1939-2019) was a leading figure in performance art and feminist art and an incredible force across a variety of mediums. An early painting in the sale displays the wildly colorful, abstracted tangles that the artist repeated sporadically throughout her career. Schneemann would largely move to performance following this period of abstract painting. Addressing social issues and gender politics, Schneemann pushed forward from participation in Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings” into revolutionary multi-media feminist art pieces, including 1963’s Eye Body, 1964’s Meat Joy and 1975’s Interior Scroll. Though Schneemann employed film, photography, poetry and installation works in her practice, she always claimed to view the entirety of her work through the lens of a painter. Schneemann explained that she was “a painter who has left the canvas to activate actual space and lived time.”

Lolo Soldevilla

Lolo Soldevilla (1901-1971) eschewed the figurative work common to Cuba in the mid-20th century after returning from a life-changing trip to Paris. Soldevilla was an irrepressible figure in Cuba – after turns in music and politics, she became Cuba’s cultural attaché to Europe in 1949. Soldevilla did not begin to create until her late 40s, but was quickly exhibiting in Parisian galleries and by 1950 was fully immersed in geometric abstraction. She was a star figure among the abstract painters group, the Cuban Concretists. Her tireless energy led Soldevilla to not only create art, but also act as curator, gallery owner and teacher in her native Cuba. A 1957 untitled collage is indicative of her bold, blocky, geometric abstractions. Also featured is an untitled 1955 work that shows a direct line to Malevich and the Russian avant-garde Concrete painters.

Lot 9. Lolo Soldevilla, Lolo Soldevilla, Cuban, 1901-1971 Untitled, 1957 Signed Lolo (lr) Paper collage on cardboard 11 x 14 1/2 inches (27.94 x 36.83 cm). Provenance: Private collection, New York, Exhibited: New York, Sean Kelly Gallery, Lolo Soldevilla: Constructing Her Universe, Sep. 6 - Oct. 19, 2019. This work was executed for an exhibition in Caracas, Venezuela, 1957. This work is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity from Roberto Cobas Amate, reg. no. 30082013388. C $7,000-10,000

Lot 10. Lolo Soldevilla, Cuban, 1901-1971 Untitled, circa, 1955 Signed Lolo (lr) Tempera and graphite on cardboard 18 1/2 x 20 5/8 inches (47 x 52.38 cm), This work is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity from Roberto Cobas Amate, reg no. 1402201400123. C $7,000-10,000

Pinar del Rio Province, Cuba, the birthplace of Dolores Soldevilla Nieto

Grace Hartigan, Self Portrait in Fur. Sold by Doyle for $4,375.

Grace Hartigan

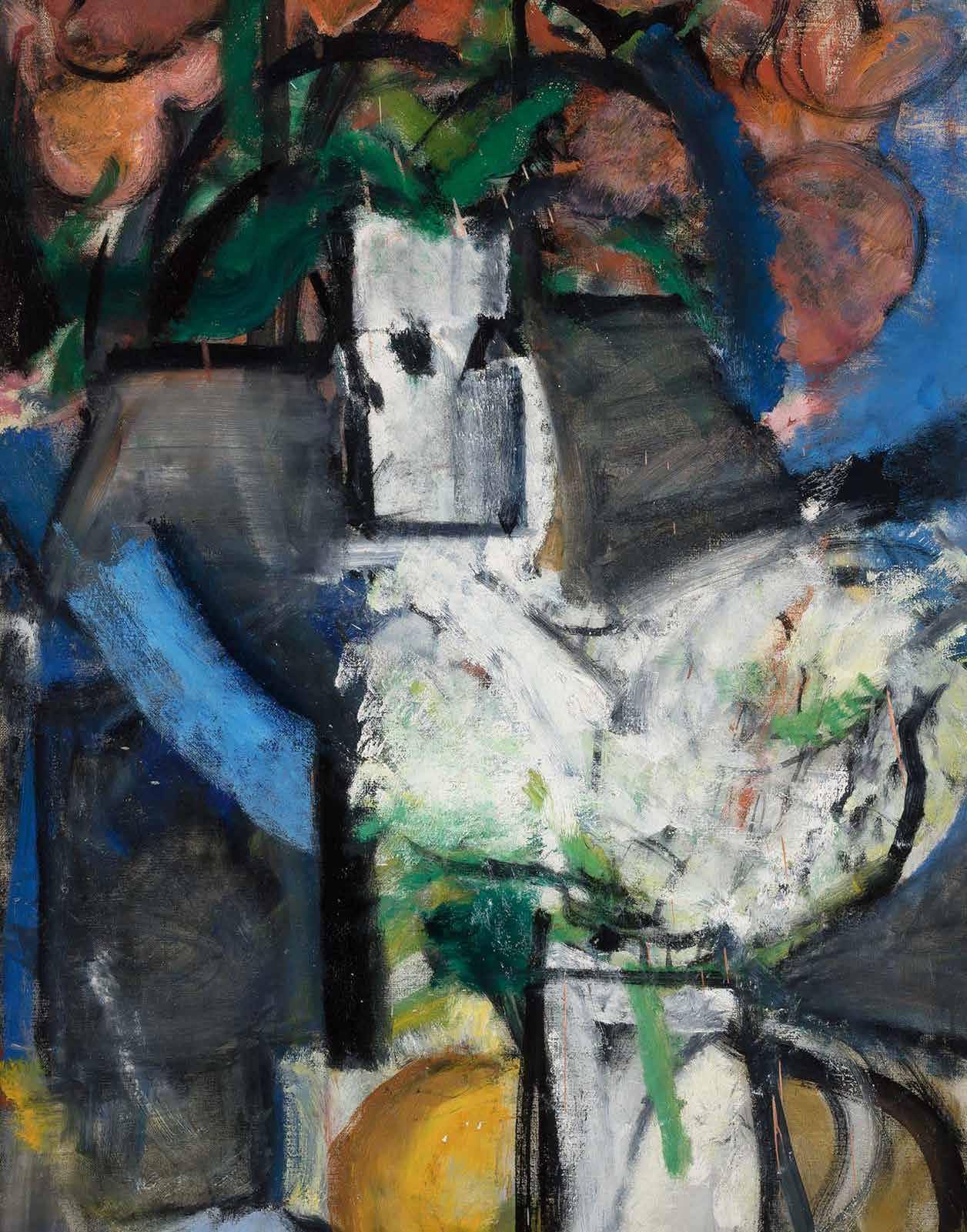

Lot 11. Grace Hartigan, American, 1922-2008 Flower Still Life, 1954 Signed and dated Hartigan ‘54 (ll) Oil on canvas 42 x 27 inches (106.68 x 68.58 cm), Provenance: [Sale] Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, May 4 - 5, 1982, Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, sale 4856M C $70,000-100,000. Estate of Richard and Carole Rifkind

Grace Hartigan (1922-2008) employed bold colors and recognizable imagery in her work. The 1954 Flower Still Life is a prime example of the chunky, distorted shapes culled from her immersion in the works of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Hartigan was the first of the second generation Abstract Expressionists to have a work included in MoMA’s permanent collection, an event followed by a sold-out 1954 exhibition at the important Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Hartigan’s pool of close friends, including Philip Guston, poet Frank O’Hara and many other legends of the New York School provided constant opportunities for exploration, growth and collaboration. The rediscovery and inclusion of figurative painting within her work both set her apart from her peers and provided a bridge to the Pop artists that would follow.

Louise Bourgeois

Lot 12. Louise Bourgeois, French/American, 1911-2010 Untitled, 1968 Initialed LB (lr) Oil on paper 17 x 24 inches (43.18 x 60.96 cm), Provenance: Robert Miller Gallery, New York Purchased from the above by Carole and Richard Rifkind Thence by descent to the estate, Exhibited: Berkeley, CA, University Art Museum, Louise Bourgeois: Drawings, Jan. 24 - Mar. 24, 1996 Traveled to New York, The Drawing Center, Apr. 24 - Jun. 8, 1996 C $100,000-150,000

A sublime 1968 work on paper by Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) shares the eccentric, organic shapes of some of her best-known sculptures. The abstract, biomorphic forms intertwine with the rest of Bourgeois’ oeuvre -- the strikingly bright colors employed here belie the bizarre morbidity of her focus on the human body. Bourgeois was a fearless creator and many of her works act as catharsis, documenting her childhood abuse and personal turmoil. Regardless of the medium, the artist created strangely beautiful anthropomorphic shapes that feel both remembered and new, alien and personal.

Louise Bourgeois, Fragile Goddess. Sold by Doyle for $137,000.