60 minute read

The How-To Issue

The How-To Issue Barbara Kingsolver’s recent collection of poems includes one titled “How to Be Hopeful.” It’s the same title as her 2008 commencement address at Duke University. Who better to contribute to DePauw Magazine’s How-To Issue than someone who has ventured there? Well, there’s that, plus she’s the bestselling author of 16 books.

And who better to tell us how to save a life than an emergency room physician; how to find peace at death than an end-of-life coach?

DePauw has a fascinating array of accomplished alumni and faculty members. We imposed on a few of them to tell us how they do what they do.

Howto

By Mary Dieter

save a life

The paramedics have radioed in to say the victim of a vicious car crash is unresponsive and his vital signs are unstable. So when they wheel the man into the emergency room, the nurse skips the usual triage process and the patient is rushed back to the room where Jeff Bohmer ’95 is ready to practice his ABCs.

“Those are the three first steps we take to stabilize any trauma patient,” said Bohmer, an emergency room physician and vice chairman of the Emergency Department at Northwestern Medicine Central DuPage Hospital in Winfield, Illinois.

“My goal is to get them out of the emergency room, to get them to the CAT scanner, identify what the injuries are, then start consulting with the appropriate consultants and specialists who need to intervene to get them the treatment they need right now and get them on the road to recovery.”

Bohmer, like emergency room physicians everywhere, uses the ABC algorithm:

AAIRWAY: Bohmer determines if the patient’s airway is open; if not, “that may mean I need to put a breathing tube down their throat into their trachea and put them on a respirator to breathe for them. Sometimes that’s not an option because they have such bad facial trauma, so we need to do … a cricothyrotomy, where we basically open up the spot right near the trachea to put a tube in.” A respiratory therapist helps with the procedure.

BBREATHING: “Then we put them on a ventilator, make sure we can actually get them breathing on their own.”

By now, the hospital has paged a trauma surgeon, the blood bank, the

radiology team and the in-house pharmacist – all of whom must be ready when Bohmer needs them. He may eventually call other specialists too. Three nurses are with him – one to pull medicines, one to get the IV line going and administer the meds and one to record the action.

CCIRCULATION: Bohmer and his team measure blood pressure and examine visible, bleeding wounds to “establish whether or not the patient has enough cardiac drive and has enough blood in their system, really, to be able to circulate and provide life to their vital organs,” he said. When the team is confident that is happening – a result of the first three steps, which happen simultaneously – they address other issues.

DDISABILITY: The medical team assesses whether something else, more than the trauma, is affecting the patient. Did the car accident and resulting trauma occur because the patient was having a heart attack or a stroke?

EEXPOSURE: When the patient is stabilized, the team exposes him to search for other signs of trauma. Does he have a broken ankle?

Femur? Back?

With breathing and circulation stabilized, the patient can be taken to the CAT scanner, which will reveal injuries to the brain, skull, spine and internal organs and vessels. Though he is not a radiologist, who can identify subtler injuries, Bohmer can look at a CAT scan and recognize bleeding on the brain or in the abdomen, and he’ll inform the trauma surgeon. If he detects brain or spine injuries, he calls a neurosurgeon.

“They’re still my patient until they leave the emergency room,” Bohmer said. “The trauma surgeon will assume some of the care of that patient once they arrive,” which is required within 30 minutes of the hospital’s page. Together, Bohmer and the trauma surgeon decide on a course of action. “They have their expertise and I have my expertise, so we share the duties once they come into the emergency room,” he said. “They also realize that I’m also managing eight or nine other patients at the same time.”

To manage the care of so many people at once, “I’m always having to run a checklist in my mind,” he said. “The way our emergency service is set up is that I’m responsible for 10 rooms, so I make a checklist of who’s in what room and what am I waiting on for that person, what does that person need and what am I anticipating with that patient.”

Bohmer sees about 5,000 patients a year. On a recent shift, he saw an eightweek-old infant who had COVID-19; a 93-year-old woman who had lost so much blood to a bleeding ulcer that she needed a transfusion; a man having a heart attack that was not revealed by an EKG; and a 30-year-old woman who fell while walking her dog and had blood on her brain. He occasionally sees victims of violence but, when possible, paramedics take such patients to Level 1 trauma centers; Central DuPage is Level 2.

“We see everyone who walks in the door, no matter what their complaint is or what their underlying issue is. … It’s a pretty wide breadth, which is what I like about it,” he said. “I don’t know what I’m seeing when I walk into the shift every day.”

The ABC – and D and E – algorithm is prescribed by Bohmer’s advanced trauma life support certification and becomes second nature, he said. The emotional toll does not.

“I’ve learned over the years that if I’m going to be able to live my life and be able to do my job and do it well, you have to put somewhat of a façade up, a little bit of a barrier or you’ll never be able to go on to the next patient, let alone the shift,” he said.

For the emotionally wrenching cases, such as the chronically ill 10-year-old who died despite the team’s long resuscitation efforts, the hospital invites the medical professionals to attend debriefing sessions with a social worker. Still, Bohmer knows he’ll never forget certain cases: The 14-year-old who died from an undetected congenital heart defect (“this was 15 years ago and it still makes my heart race when I think about this”). The woman attacked by a pack of stray dogs.

“There are certain ones who definitely stick out that I’ll take to the day I die,” he said. “And those are the ones that shape us and make us who we are.”

Howto

By Mary Dieter

So you want to write a novel. Be prepared for intense preparation, exhaustive research, careful writing and meticulous revision.

That’s what you can expect, anyway, if you follow the lead of Barbara Kingsolver ’77, bestselling author of eight novels and eight other books. Though engrossed in work on a new one, she responded in writing to DePauw Magazine’s questions about how to write a bestseller.

The plot thickens:

PROLOGUE: “I get ideas everywhere,” she said. “On a walk in the woods, in the grocery. I’m a chronic eavesdropper. I love listening to people’s language, their points of view. … “Nothing ‘just comes.’ I spend years evaluating ideas for their literary potential. For a novel to be worth a reader’s time (and mine), it needs to be about something extremely and universally important, so I lean into my biggest worries. Some examples from my past novels: climate change, partisan divides between rural and urban people, cultural paradigm shifts, the history of colonial arrogance, child abuse. … The hard part is finding a way into a story that will ask big questions, guiding a reader through a compelling exploration of the subject.”

Early in a book project, Kingsolver spends time “choosing and honing a subject, sketching the architecture of the plot, inventing the characters and finding

Photo: Steven L. Hopp

write a bestseller

the story’s voice. I usually spend a year or more on those things before I write the first sentence, the first scene, so I’m very clear about where it’s all going.”

THE SETTING: Kingsolver works on a desktop computer in a book-lined, upstairs office in her family’s Virginia farmhouse. It’s quiet; “any kind of music or noise is distracting, because I’m listening to voices in my head,” she said.

“Does that sound, um, crazy? To be honest, fiction writing might be a carefully controlled lunacy.”

A map of her novel’s location – real or drawn by her – hangs on a nearby bulletin board, surrounded by photos “that resemble important images in my mind – my characters (faces or body types), crucial possessions, articles of clothing, views out a window. It grows into a giant collage. If my novel has an exotic location that’s far from the real view out my real window – like the Congo, Mexico or the 19th century – these visual cues help to get me centered in the world of my novel. I’ll often begin my writing day standing in front of that bulletin board, letting my focus go soft and walking in. Like Alice’s looking glass.”

She begins by creating computer files to store descriptions of her characters and their histories; timelines; themes; and “a big, expanding plot outline.” When she has worked out the plot, she creates a file for each chapter, starting with a few sentences about what will happen in it. “As the story develops and I know more, I can fill these out in greater length,” she said. “By the time I actually begin writing the novel scene by scene, I never start with a blank page. …

“Once I’m well into the book, I’ll jump around a lot. Ideas come to me for scenes that happen at various points mid-novel, and I can write them and put them in

place. At some point, usually pretty early on, I’ll get a clear vision of the book’s final scene, and write it. The end is always written long before I reach that point in the first draft. That way, I can aim everything else toward that focal point, making sure it all adds up just right.”

THE INITIATING EVENT: Kingsolver majored in zoology at DePauw (the precursor to biology), figuring it would lead to a “secure livelihood.” Writing, she said, “was a private passion that grew out of my love of reading. Novels opened the windows of my brain. I started keeping a journal at age 8, and never stopped. I had no ambition to become a professional writer … I just wrote every day, as a way of processing my experience.”

By college age, “I was reading very consciously, noticing how Dickens constructed his plots, how Steinbeck used point of view to reveal character. Doris Lessing blew my mind, showing me that a novel is – or can be – not just about plot and character but also the biggest problems in the world, like sexism and racism.”

RISING ACTION: “I’m always creating on the page, even if I’m working within a planned plot,” Kingsolver said. “The creation is craft. Choosing the exquisitely right words, making sentences that sing, finding the poetry of language.”

She is not influenced by public acclaim or reader expectation, she said. “You don’t get a backlist like mine by trying to please an audience. I mean, let’s face it: climate change, racism, death by snakebite – these things do not scream ‘marketable.’ I just concentrate on doing my best work, even if it takes me into dark and scary places, and trust readers to follow me.

“Many years ago I wrote these words of advice that are now popping up every day in my Instagram feed, so they must be ringing true: ‘Close the door. Write with nobody looking over your shoulder. Don’t try to figure out what other people want to hear from you. Figure out what it is you have to say. It’s the one and only thing you have to offer.’”

CONFLICT: When she embarks on a new book, even after writing 16, “I struggle all over again with the sense that this is too hard, I’ve bitten off more than I can chew, I won’t be able to pull it off,” she said. “When I start feeling daunted, I have to take a deep breath and give myself permission to write a bad first draft. … That permission is very liberating.”

Some of her best thinking occurs in bed, “when I’m first awake in a dreamy state. Often, when I have a tough writing knot to untangle, I’ll set the specific intention of knowing the answer the next morning. And usually, I do.” Other times, she’ll take a five-minute walk, using “basically the same techniques that are helpful in amicably settling disputes with a spouse.

“In some ways, writing a novel is like a marriage. You have to keep showing up, enjoying the company and, when problems arise, you trust the process of working them out.” CLIMAX: “For me, the real art is in revision,” Kingsolver said. “It’s most of the work I do. Honing the language, finding new insights into character, rearranging scenes and events to build the story more perfectly. … I promise you, every paragraph of mine is rewritten at least a dozen times before it’s published. Some are rewritten a hundred times. The first page, probably two hundred.”

FALLING ACTION: The time it takes for Kingsolver to complete a novel varies. Some were written in two years; “The Lacuna” took about seven; “The Poisonwood Bible,” 20. “I also worked on other things during that time, but I was actively writing that novel for two decades,” she said. DENOUEMENT: When a book is finished, “it’s a cathartic ritual to take down all those pictures and start again with a clean cork surface, waiting to be filled,” she said. In between books, she works on smaller projects – travel articles, magazine pieces, essays.

“It’s therapeutic, looking forward to these projects as small treats, because finishing a book is strangely sad,” she said. “There’s a postpartum letdown, the painful farewell to these people who’ve been living in my head for several years.”

She has no plans to retire. Writers “tend to hit our stride in middle age and could actually do our best work in our 70s or 80s,” she said, “because our stock in trade is not just language, it’s wisdom. Isn’t that what readers are really looking for? And wisdom can’t be rushed; it only accrues with time and experience.”

Howto

By Sarah McAdams

Happiness is not always about being in a good mood or having a smile on your face.

It’s about having an underlying and predominant sense of wellbeing, said Doug Smith ’68, whose 2004 bout with leukemia caused him to quit work as a food industry executive and to

watch, read and eat, and with whom you socialize. • Be altruistic and kind. Before you take an action, ask yourself, is this kind? If it isn’t, think of another action. • Think with abundance. Stop comparing yourself to everybody else. • Master your stories. Most of us have a little voice in our head that’s talking to us from the second we wake up and often long after we’d like to go to sleep.

It’s saying things about you and others that you’d never say out loud. How do you stop listening to that voice and start telling better stories? • Find meaning and purpose. Figure out what you want to do with your life and get about it. • Cherish relationships.

be happy

study happiness, well-being and resilience in the face of setbacks.

Since 2006, Smith has taught a winterterm course at DePauw that focuses on happiness. He is the author of two books, “Thriving in the Second Half of Life” and “Happiness: The Art of Living with Peace, Confidence and Joy,” and co-founder of Positive Foundry, an organization dedicated to enabling individuals and their organizations to flourish.

One can achieve happiness, he said, by developing and practicing skills that lead to peace about the past, confidence in the future and joy and exuberance in the present. Here are his specific steps toward happiness:

THE PAST:

• Forgive. Forgiving yourself is the ability to learn from your mistake. Forgiving someone else is releasing the desire for vengeance. • Feel gratitude. Stop focusing on what you don’t have and be thankful for what you do have.

THE PRESENT:

• Do now what you’re doing now. Stop multitasking. Have your head be where your feet are. • Honor mind, body and spirit. Pay attention to what you

THE FUTURE:

• Practice faith. • Find optimism. • Be flexible. • Exhibit openness. • Be inspired by love. Your life is either based on love or on fear – the fear that you won’t be enough or won’t have enough. Smith said those fears drove him “to get up really early in the morning and work really hard.” But if you’re driven by those fears, it’s hard to be happy. And there’s a better place to be: Inspired by love.

Photo: Marilyn E. Culler

Howto

By Mary Dieter

Two bidding wars. And a headline that says NBC “nabs” his medical drama.

Marqui Jackson ’00, it would seem, has reached the pinnacle.

“Nooo,” he said, drawing out the Os. “I’m just getting started. … The pinnacle? Not even close. When you have a billion shows on the air, like a David E. Kelley or Shonda Rimes or Ryan Murphy, then you can say you’ve done something. But I’m still on my way.”

His 18-year journey of persistence, resilience and humility – of “a lot of getting lunch and coffee, personal errands and all of that” – has brought him here: Three production companies competed to produce his show, “Family History,” the story of a Black family of physicians who buy a hospital. Imagine Entertainment, a company owned by Ron Howard and Brian Glazer, won. And then NBC beat out Fox to be the network where the show, if made, will air.

Jackson, who is co-executive producer on “The Resident” and has worked on other popular television shows such as “House” and “Rosewood,” is writing a script and waiting to hear if NBC will make the pilot and, ideally, more episodes. This puts him closer than he’s ever been to being an executive producer of his own show, a goal toward which he has worked since, two years out of DePauw, he earned a master’s degree from Texas Christian University and “started from scratch” in Los Angeles.

So what lessons do Jackson’s experiences teach?

TAKE WHAT YOU CAN GET: Jackson had been working as a temp when he landed a job as a production assistant on “Half and Half,” a sitcom. Not his thing.

“I took the comedy jobs just to get into the industry, to get to know people,” he said. “And just to find my way. I’ve got to eat, and so if I’m going to be working at a job that’s not what I want to do, at least it’s in the industry. And I did learn a lot.”

Later, he worked as an assistant to an agent at Creative Artists Agency LLC. Again, it wasn’t ideal, but he learned a lot. And his end goal was to demonstrate to folks at CCA that they should take him on as a client, something that is “extremely hard to do, to get an agent,” he said. Ultimately, that happened, leading to Jackson’s first job as a professional writer for “The Forgotten,” a Jerry Bruckheimer procedural.

LEVERAGE CONNECTIONS: About that first comedy job? “One of my professors at TCU had a student who had a husband who was a writer’s assistant,” Jackson said. “I got my resume to him, he got it to his bosses, they brought me in, they interviewed me and I got the job.”

break into TV

Later, when he was assistant to the executive producer of “Ugly Betty,” Jackson applied for a fellowship with the Walt Disney Television Writing Program, a big deal in the television business. His boss made a call to recommend him. A colleague who was already a Disney fellow sent an email to the head of the program, and Jackson got an interview. When Jackson learned that Brian O. Harvey ’94 was then working with Disney-connected ABC, he asked Harvey to meet for coffee. They did, and Jackson asked if Harvey would recommend him for the Disney fellowship. “And then he did,” Jackson said of Harvey, who now is a development executive with Amazon Studios.

TAKE RISKS: When Jackson became an assistant on “Ugly Betty,” he hoped he’d be asked to write an episode, something that happens now and then. But it struck him that “everybody has an assistant; I’m literally assistant No. 8,” he said. “And I’m going to have to wait 10 years to get my shot.” That’s when he decided to leverage his relationships with ABC people and go for the Disney fellowship.

When he hadn’t gotten word about the semifinal round of interviews – two friends who also applied had landed interviews and Harvey told him things looked good – “I did something that I ordinarily wouldn’t have done,” he said. He emailed a highlevel executive at ABC, “a guy who helped decide what you guys see on ABC at home. I get coffee and answer phones.”

The executive had, at some time, offered what may have seemed a gratuitous line – “if you need anything” – but Jackson took him at his word. The exec responded with news that Jackson was supposed to be interviewed, but someone accidentally failed to call him. Jackson got the interview and the fellowship.

“Had I just accepted my fate, my life today would be completely different,” he said. “I always tell that story to upand-coming writers because, when you’re getting close to an immediate goal, when it’s so close you can see it – you can almost taste it – sometimes the journey requires that you dig a little deeper.”

Years later, Jackson began work on the “Family History” script after learning that Lee Daniels Entertainment wanted a show about Black doctors. The Daniels company ultimately passed on the script, as did 20th Century Studios, producer of “The Resident.”

“It was late in the year in terms of developing stuff for broadcast, so I was like, I’ll just shelve it and pitch it next year,” he said. Then, in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and was disproportionately affecting people of color, Jackson revived the concept, and the bidding wars ensued.

HAVE A PLAN/SET A GOAL: He tells young people who ask his advice, “Don’t just have one plan, have multiple plans. Have five. And have them all working at the same time because you just don’t know how you’re going to break in.”

Having worked his own plan, his goal now “is to sell and get my own shows on the air,” he said. “I came out here to write my vision, not everyone else’s. But there’s a process in that. There’s a grooming and refining period …

“It’s a tough and competitive business, so to sell something, let alone to get something on the air, is like lightning in a bottle.”

Howto

By Mary Dieter

The legend was wrong: Jimmy Hoffa’s body wasn’t found buried under the end zone when Giants Stadium was demolished in 2010.

Maybe it was cremated in a trash incinerator or crushed in a compacted vehicle sold as scrap. It might be buried in concrete under a skyway in New Jersey. Perhaps it was fed to Everglades alligators. Or maybe two federal agents pushed Hoffa out of an airplane as it flew over the Great Lakes.

For more than 45 years, a lot of people – including the FBI – have devised hypotheses, advanced theories and tried to solve the mystery of what happened to Hoffa, the former Teamsters president, after he disappeared July 30, 1975, from the parking lot of a restaurant outside Detroit.

David Witwer ’85, a professor of American studies at Penn State Harrisburg who is writing a book – his fourth – about Hoffa, is less interested in searching for Hoffa’s physical remains than he is about searching for who Hoffa really was.

Champion of working people or “corrupt, criminal, ruthless, violent, vile” union leader? Hardworking advocate for the little guy or mob collaborator? Family man with a modest lifestyle or all-powerful organized crime figure? Working-class hero or a symbol of corruption? Unsolvable mystery or mythic figure?

Photo: Penn State Harrisburg

“What the book is about is looking for that Hoffa, that Hoffa who’s so hard to pin down,” Witwer said.

As the Penn State laureate for 2020-21, Witwer lectures about his research into union corruption, organized crime and labor racketeering, subjects he has pursued since obtaining his doctorate degree. His first job out of DePauw – investigative analyst for the New York district attorney – sparked those interests.

He has conducted research at the National Archives, poring over eight boxes of reports by investigators pursuing Hoffa at the behest of Robert F. Kennedy, who as a Senate committee counsel and U.S. attorney general, styled Hoffa as “totally corrupt,” Witwer said. The union boss, who was born in Brazil, Indiana, in 1913, finally was convicted in 1967 of fraud, conspiracy and jury tampering and sentenced to 13 years in prison. In 1971, however, he won clemency from President Richard Nixon on one condition: He had to resign the Teamsters’ presidency, to which he had been re-elected while incarcerated.

After he was released, Hoffa began seeking support to run again anyway. Then he disappeared. Theories – and legends – abound about what happened. Witwer dismisses as nonsensical the suggestion that the mob killed him to stop him from running for the presidency; not only would the Nixon administration likely put Hoffa back in the penitentiary, but the historian can’t imagine why organized crime intentionally would invite the public and law enforcement attention that the disappearance precipitated.

Witwer said another theory that “makes some sense” is that, when the mob opposed his candidacy and tried to dissuade him from running, he threatened

find Jimmy Hoffa

retribution: Snitching to law enforcement. He thinks the mob planned to intimidate Hoffa, not kill him. But he ended up dead, and after the panicked functionaries did something with the body, their displeased bosses moved it for “a double layer of security.”

So will Hoffa be found? “I don’t think you do find Hoffa’s body,” Witwer said, though some are still trying. That includes the FBI, though those who know what happened likely are dead and thus can neither provide information nor be charged with a crime.

But the mythic figure lives on, primarily because the mystery endures.

“Some people have talked about Hoffa’s significance as a folk figure, a mythic figure, … the kind of working class Everyman who defies the authority and the establishment,” Witwer said. “Myths matter because they tell us something about how we explain our world.”

View in the crowded caucus room in the Senate Office Building as James R. Hoffa (on right), began his testimony before the Senate Labor Rackets Comittee. Beside him is attorney George S. Fitzgerald. Aug. 20, 1957. Courtesy: CSU Archives/Everett Collection.

Howto

By Mary Dieter

Willis “Bing” Davis ’59 sees art everywhere. Hears it too.

“It’s never far from my mind,” he said. “It’s a way of existing and being.”

When he spotted a shredded tire on the side of the interstate, he was reminded of the necklaces an African dancer might wear. So he pulled a u-turn, stopped and tossed the tire – which will someday adorn one of his anti-police brutality masks – into his car.

When, ensconced in his basement workshop, he heard the footsteps of his wife from above as she entered their Dayton gallery, he beat out a rhythm with his fingertips. “Once you get tuned into that, you collect information all the time,” he said.

When, as a high schooler, he saw an iridescent oil slick in a mall parking lot, he knelt to observe the colors, prompting queries from his peers. “It used to bother me when they’d think I was crazy,” he said. But “once you get into that mode of working and thinking, then you make it a part of your life.”

And when he recently entertained a visitor to his gallery and “caught a glimpse of the leaves making patterns in the window,” he did not miss a beat in the conversation. “I’m actually concentrating more and I’m picking up more,” he said.

At 83, Davis makes ceramics, paints and sculpts using found objects such as the shredded tire. He learned his broad approach to art from Richard E. Peeler ’49, for whom the DePauw art center is named and who was Davis’s teacher, academic adviser and, when Davis taught at DePauw for six years, his colleague. Peeler, he said, asked the question: “How do you use art to enhance growth?”

Davis’s answer: “Once you open up to it, it’s unlimited what you can do.”

Davis said he will never stop making art. “You don’t do that,” he said, his tone incredulous. “You find time. You stop the other stuff so you have more time to do the art. Because that’s really a lifeline.”

He officially retired from teaching in 1998, but still participates in and sponsors workshops, summer camps and art lessons for children and teens; volunteers for community projects; and operates his gallery. He recently was hired as an aesthetic consultant to place African symbolism on a bridge in Dayton.

He said he wants to stop all those things – but provides no timeline for doing so – and “just enjoy making art and enjoy being alive.”

create art

Here are some of Davis’s other thoughts about art:

IT REFLECTS VALUES: “Art is a reflection of spiritual, cultural and social values of all people,” Davis said. “And so you can look at any culture or any people, and look at the art, their music, their dance and their drama, and you understand their whole way of life.”

IT TEACHES SKILLS: Teaching children art “enhances self-concept and confidence, increases goal setting,” Davis said. A young person who creates art learns critical thinking; creative problem-solving; fluency of thought; instrumental behavior to solve a problem; and assessment and evaluation – “all qualities an individual will need to enhance their success on the job and in life.”

Photos: Brittney Way

IT PROVOKES ACTION:

Art can be an “agent of change,” he said. That’s why much of the art created by this friendly, upbeat man addresses violence. “Sometimes art can say things that you have a hard time saying in words or can stimulate a conversation,” he said. “I want to find as many ways as possible of putting the viewer into the position of thinking and taking action on a serious problem.”

Davis has a series of sculptures labeled as “antipolice brutality masks.” He recently completed “Colin Kaepernick and George Floyd Cushion,” a sculpture that juxtaposes former quarterback Kaepernick’s taking a knee to protest police abuse of Black people with the death of George Floyd, who died when a police officer knelt on his neck. And he is working on a multi-media piece centered on the August 2020 shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and the killing of other Black people by police officers.

IT PROMPTS LEARNING: “Clay is still my favorite medium, but I was accustomed to working in and teaching a variety of techniques and a variety of mediums, and I just keep it up professionally,” he said. “So when an idea comes, sometimes I transfer that same idea to a variety of mediums to see the different effects. And sometimes when I get an idea, it already suggests a technique. If I don’t know the technique, I’ll learn it.”

Howtowrite a love letter

By Sarah McAdams

Your heart beats faster; your palms sweat. You get butterflies in your stomach. And you’re smiling a lot.

You’re in love.

So how do you communicate your feelings to the object of your desire? Jen Adams, associate professor of communication and theatre, has some thoughts on that.

For her doctoral dissertation, Adams studied 400 love letters she found in the attic of the Victorian home she was renting. The deceased owners had written them to each other in the 1930s.

“They wrote every day, and their relationship is detailed in these letters,” Adams said. “I was able to study the progression of how their relationship developed, which was historical and very romantic.”

Adams did not publish her work immediately, thinking the letters too personal. But after her DePauw students persuaded her to search for the couple’s children, Adams found their daughter, who was thrilled to learn of the letters and who gave her permission to publish them in a book.

Here’s what Adams saw demonstrated in the letters:

BE AUTHENTIC: “You should try to be as authentic in representing yourself and your feelings as you possibly can,” she said. “We are not all poets, nor can we write Shakespearean prose, and that’s probably not what our loved one wants to hear anyway. They want to hear our voice.”

REFLECT SIGNIFICANT MOMENTS

TOGETHER: Adams suggested writing about anything that relates to your past together. “I think it is a useful way of communicating the love and importance of that person,” she said.

ADDRESS THE FUTURE: “If it’s a true love letter, you want to encourage them to also think about your future together. It doesn’t have to be, ‘Let’s get married,’ but, ‘I hope we can continue to have these shared moments.’”

WRITE BY HAND: It takes effort and time, but do it anyway, she said. “I imagine that, for some people, that might be frustrating, but I also think that it’s a really valuable exercise,” she said. “… Most of us aren’t used to it, so we have to slow down.” That doesn’t mean the letter will automatically be more thoughtful, but it allows time for reflection.

CREATE ATMOSPHERE: Use language to create an atmosphere for your loved one to read the letter. “That’s something that my letter writers did all the time,” Adams said. “They would share, ‘when I got your letter, I sat down in my bedroom, dimmed the lights and read it.’”

Howto

run for your life By Sarah McAdams

For every day of 20 years, 10 months and 16 days, Pat Babington ran at least a mile.

His streak stopped when he hyperextended his knee while attaching a camper to his truck. Arthritis aggravated the injury and, “ultimately the pain was too great to walk, let alone run,” he said. So the DePauw associate professor of kinesiology took a WORK THROUGH THE DAYS when you don’t feel like running. “There were many. Basically the hard part was getting out the door. If you get out the door then year off running.

“Stopping wasn’t as big a deal as I thought it would be,”he said, but he nevertheless started back up in January 2020, and now runs about three miles every other day.

He shared tips he learned along the way for anyone contemplating running: everything ends up being OK. Some of my best runs were on days that I didn’t feel like going out. … Ended up, I always went further on those days.”

DECIDE TO START. It wasn’t initially Babington’s idea to run every day. His wife Cindy “offered the challenge of ‘let’s try to run every day for a year,’” so they started on New Year’s Day 1998.

HAVE A PARTNER to whom you can be accountable, at least initially. “You end up being accountable to a whole host of people once word gets out that you have a running streak.”

FAMILY SUPPORT HELPS. “My daughter woke me up one night at 11:30 p.m. with the statement, ‘Dad, you haven’t run today.’ I had the flu, but off I went for my mile run in the dark.”

PAY ATTENTION TO HOW YOU

FEEL so you know when something is wrong. “Running every day hurts. If something hurts more as you run, then it’s not good. If, as I ran, a pain lessened, then it wasn’t a concern, but I paid attention if the pain got worse.” DON’T GET SICK OR INJURED. “If you do, back off and fix the problem. In 20 years, I ran with the flu and colds many times. I also had non-running related injuries that I had to work through. Normally, some strengthening exercises helped me get through the injury.”

PICK A TIME OF DAY to do your run. “I always ran at noon.”

PLAN FOR THE WEATHER. “If you are running outside every day, then there will be snow, rain, heat and cold. I ran when it was minus-10 and when it was 95. For freezing rain or icy streets, I suggest investing in a pair of Yaktrax.”

DECIDE A DISTANCE that counts as a run. “I chose a mile. There was no real reason for this distance. Other people have counted less as a run, some more.”

DECIDE IF TREADMILL RUNS

COUNT. “I never did. For a run to count it had to be outside. If I ran inside, I still went outside for the daily run of at least a mile.”

Photo: Cindy Babington PLAN AHEAD FOR TRAVEL and stay on the time where you live. “When I went to Vietnam during winter term, I stayed with local time so I may have picked up an extra day. I also ran at 3 a.m. before our return trip just to make sure I got a run in. In Australia during another winter-term course, I ran on Indiana time. It was much easier to figure out how not to lose a day.”

Howto

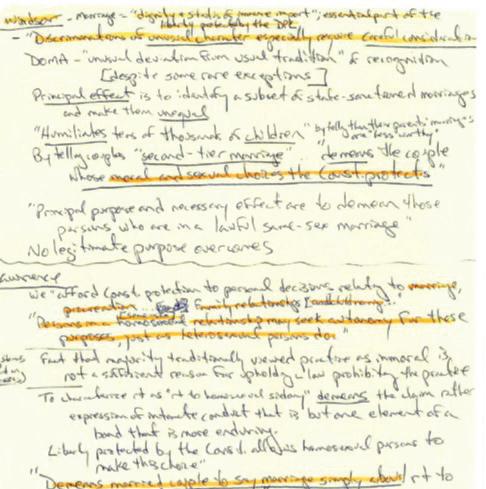

By Mary Dieter

He donned his dark grey pinstriped suit – the one he always wears for Supreme Court arguments – and fixed his cuffs with the “D”-monogramed links that had been his grandfather’s.

And then, aware of the “pretty narrow window of what is acceptable attire in court,” he chose a tie that, “while understated and appropriate, does have a little bit of pink in it.”

Pink, the traditional color of the

LGBTQ movement, “a signal of defiance and resilience,” he said. With that,

Douglas Hallward-Driemeier ’89 was ready to argue the most momentous case of his career, the one that would result in the 5-4 decision that legalized marriage between two people of the same sex.

Hallward-Driemeier has argued before the U.S. Supreme Court 17 times, including earlier in the same month,

April 2015, of the Obergefell v. Hodges argument. While preparing for the latter,

“the highlight of my career,” he followed many of the routines that he follows for every case, though with extra emphasis on a few steps.

Ultimately, he said, “it’s all about preparation,” which includes:

COLLABORATING AND

STRATEGIZING. Chris Stoll ’91, a friend from DePauw and Harvard Law School,

Photo: National Center for Lesbian Rights

brought Hallward-Driemeier into the marriage case in November 2014. The 6th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals had ruled against the National Center for Lesbian Rights, where Stoll is a senior staff attorney, sanctioning Tennessee’s refusal to recognize the marriages of gay and lesbian couples who were married elsewhere and moved to the state.

Hallward-Driemeier and the team designed their case thinking the high court might require states to recognize marriages that occurred in other states, a “baby step” toward equality. But then the court said it would consider two issues raised in four cases – the constitutionality of samesex marriage bans and the recognition issue. That, he said, “increased the level of collaboration we had to have with the other counsel. We were all collaborating very, very closely anyway, but once it was agreed that I was going to argue for all of the plaintiffs on the second question, it was more formalized. I am now speaking for them as well. I need to be engaged with them and taking their points and suggestions, but I also had to know the facts of their plaintiff’s case better than I had.”

While his associates surveyed marriage laws across the country, HallwardDriemeier and other team members anticipated issues the justices might ask him about. “You have to say, if I were coming to this totally fresh and I was just a really super smart person and very, very curious, what are the questions that I would have?” he said.

IDENTIFYING THE TARGET:

During preparation, “everybody knew that the entire case was about Justice

argue before the Supreme Court

(Anthony) Kennedy,” he said. “We had written our briefs for Justice Kennedy. We had thought long and hard about how to pitch it. We pitched our case as a marriage case, not an equal protection case, because we thought that was how Justice Kennedy would respond.”

Indeed, during the arguments, “every question that every justice asked was designed to sway Justice Kennedy,” who ultimately wrote the majority opinion.

STEPPING AWAY: After “trying voraciously to just suck in as much information” as he can, “at some point you have to step away from that so that you’re dealing with it at a higher level of generality; you’re thinking about your themes; you’re thinking about, how am I going to articulate that? How am I going to pivot that question? If it’s a hostile question, how am I going to turn it?

“… At the end of the day, there’s only one person who’s at the podium, and it’s you. So, first of all, you have to have it in your brain. Second of all, you have to be confident about it.”

PREPARING THE MANILA FILE

FOLDER: Instead of memorizing lengthy answers to specific questions that may or may not be asked in just that way, Hallward-Driemeier homes in on topics. He handwrites his notes, because there is “something about the process of going from the brain to the fingers that helps in the memory.” Then he repeats the process, writing on the inside of a manila file folder, “my cheat sheet, because if I’m going to quote from a cases, I want to make sure I get the quote right. … That way I don’t need to have memorized those pages. That doesn’t seem like a good use of brain space to me.”

HOLDING MOOT COURT: For most cases, Hallward-Driemeier practices in two moot courts. For Obergefell, he and the team held four formal moot courts and various informal sessions. They started a month before oral arguments were to take place, unusually early for moot court, he said.

TAKING A WALK: As an oral argument nears, “I go on a long walk. I don’t have any papers,” he said. “I just am on a long walk and thinking it through in my head. … “For the marriage case, rather than doing that on my own, I had three colleagues who were working very, very closely with me and whom I just trusted absolutely, each of whom brought something different.

They came over to my house and we went on a long walk together and, as it happens, it was at the peak of cherry blossom bloom. There’s a neighborhood very nearby with beautiful cherry trees and we just walked around and around and around this neighborhood, talking through the case.”

After that, he avoided the office for the days leading up to oral arguments, preparing at home “because I needed to be in my own head. I needed to be thinking it through myself because, again, you own it yourself at the podium. I couldn’t take any more input at that point.”

SETTLING IN: When the arguments have begun and opposing counsel is speaking, Hallward-Driemeier takes notes, especially of the questions the justices have asked. “I’m looking for an opening in those questions,” he said. “… I don’t really like giving speeches and so I always feel much more comfortable once the questions start, because then I’m in conversation with the justices.

“If I’m the respondent or appellee, I’ll always prepare opening remarks, but I almost never give them as prepared because what I’m looking for is an opportunity to jump into an ongoing conversation. … For me, that’s how to make it more natural and how to engage them. You have to see oral argument as a discussion.”

SETTLING DOWN: While his cocounsel was arguing the constitutionality question, Hallward-Driemeier experienced something that has not happened before or since: “I started to experience a very tight chest. …

“I thought to myself, this would be a very, very bad time to have a heart attack. I said to myself, OK, the chance of my having a heart attack was almost nil, but it sort of felt like that. I really went through this process: OK, you’re feeling the pressure. I hadn’t been focused on that; I’d been focused on the argument prep. All of a sudden, sitting there, the weight of this hit me. And I had to go through a process. I had to let it go.

“It’s not the weight of all of these people on me. … I had friends, clergy friends, who were outside the court praying for me. I knew that. And I thought, they’re there. All of these people are lifting me up. And I thought about that and, with that, I was going to let it go, and the pressure went away and I was able to focus again on the case.”

Howto

sell pot (legally) By Mary Dieter

Justin Dye ’94 had had a long and successful business career in an array of industries, but when it came to his most recent career move, he consulted his grandfather. And his father. And his minister.

He asked his grandfather: “Do you think worse of me if I get involved with this? Here are the things we’re thinking about. Here are some of the stories I’ve heard about this. Here’s a growing industry. This plant does a lot of good for people. And it’s been ostracized and there’s a lot of stigma to it. Do you think I’m a bad person?”

Grandpa, age 94, a conservative, retired high school principal who is Dye’s hero, told him: “Absolutely not. I have friends here in Idaho who go to Oregon and use cannabis regularly.”

Dye’s dad, who was awarded the Purple Heart for being wounded in Vietnam, admitted he used pot back then. The minister said he should go for it, and ended up investing in the company. So in December 2019, Dye became chairman and chief executive officer of Schwazze, a Colorado firm that cultivates cannabis; manufactures cannabis-related products for wholesale and retail sale; owns and operates 17 dispensaries; and consults in 22 states.

How does a guy who didn’t use pot when he was growing up in tiny Winslow, Indiana, evolve into a big shot at a growing cannabis company? “I didn’t use for moral reasons and, to be honest with you, I was uneducated about it. You’d see Nancy Reagan says don’t use drugs in the ’80s and cannabis was one of those. Marijuana was one of those. I think after a lot of research and spending time with people and really understanding what a wonderful, wonderful industry it is, and it does a lot of good for people, the stigma wore off for me and it’s wearing off for America.

“If you look at who’s coming into the category, it’s folks who are seeking pain relief, better sleep. There’s a whole host of things it can help with – the plant in different forms – and you know, simply having a relaxing Friday evening or a Saturday evening, versus having a glass of wine, people can have a gummy or can participate with the plant in different ways. So that stigma wore off for me as I got educated.”

Dye said his DePauw friends reading this likely are shocked. If he could have a “good, old-fashioned conversation” with them, he would tell them “what the opportunity is. This industry today is a little over $10 billion. It’s going to be $100 billion by 2030. It’s projected that. It’s probably the fastest-growing industry in the United States and it does a lot of good for people.

“… You’re helping change people’s lives and you’re making the world a better place. And you’re getting to professionalize and build an industry, and that’s incredibly, incredibly satisfying. It’s hard work and I have the privilege here. We’ve recruited a fabulous team here and it’s fun to come to work every single day, trying to change the world.”

Photo: Schwazze

Howto

By Mary Dieter

Lauren Clark ’11 was doing standup comedy and improv on a New York City stage, buoyed nightly by the laughter, when the COVID-19 pandemic ripped her from her moorings.

“My tiny Brooklyn apartment was not going to be pandemic-proof,” she said, so she moved in with her mother and stepfather in Charlotte, North Carolina, and began to contemplate how to survive outside the “bubble of comedy” in which she had lived for nearly a decade.

“I was very upset because it was like,

I don’t know the next time I’ll be on the stage again. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that I can’t create,” she said.

Here’s how she does it:

“MAKE DO WITH WHAT WE HAVE”:

Early in her pandemic-induced quarantine, she said, “the idea of just like, OK, now I have a year ahead of me and all I can do is write; I can’t actually take it on stage or turn it into some kind of short film or anything – that was a bummer at first.”

But as the quarantine has dragged on, “we all seem to collectively realize we’re going to be in this situation, the pandemic, for a little while, so we have to adjust; we have to make do with what we have. That’s where I’m at.”

ESTABLISH A ROUTINE: Clark, who moved into her own place in August, gets up as early as 4 a.m. and, after getting

Photo: Mike Baker

be creative in a crisis

ready for the day, sits down to write for four hours. (Her remote work as a customer experience representative for a New York-based startup comes later.)

“If I do it based off of my feelings, I’ll never write,” she said. “I never actually feel like writing. … I’ve gotten really, really strict with the routine in a way I really haven’t before. And I think because of that it has really, really helped my creativity.”

TAKE RISKS: After graduating from DePauw, Clark had had the courage not only to move to New York, but to study improvisation and sketch comedy at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and perform stand-up comedy.

“I really had no idea what I was doing but I knew very, very intuitively that you have to start before you’re actually ready,” she said. “I had so many bad performances when I first began in school but I didn’t care because I just had so much fun.”

Later, she co-founded a sketch comedy group called My Mama’s Biscuits out of frustration that the theatre, which since has folded, did not give Black comedians much stage time.

With the pandemic preventing her from performing on stage, Clark has diverted her creativity to producing the Black Creator Connection podcast, on which she interviews a Black artist each week about his or her work. She also is writing personal essays and a script for the pilot of an autobiographical television show.

“I had always wanted to do a podcast and truly I always had so many excuses for why I didn’t,” she said. “My main thing was just perfectionism. Perfectionism truly stopped me, just like oh, I know all of these other people who are podcasting out of a studio, and they have the best equipment and they’re booking these guests and giving them incredible snacks. Like, who lets snacks stop them? I did.

“But I realized people are going to be a little more forgiving now, with the pandemic. Everybody is doing the interviews over Zoom, so even if I have the best equipment but something sounds a little off because of Zoom, nobody’s going to belittle or come down on me for that. But then, also, if they do, who cares? People are always going to be judging. So you might as well let that be liberating and just do whatever you want.”

PURSUE A LARGER PURPOSE: “The work that I’m doing right now, a lot of it feels very mentorship-y,” she said. “I’m starting to coach people and help them on a one-on-one basis. And the Black Creator Connection is essentially that as well, where I’m just motivating people and making sure everybody is staying positive and inspired …

“I just genuinely want people to have a space where they can share their experiences and we just have a conversation about the creative journey, the creative life. Hopefully, for whoever is listening, it unlocks something for them too.”

Howto do well byBy Mary Dieter

Two years out of DePauw and newly graduated from the Thunderbird School of Management,

Jim Alling ’83 just wanted a job. “It’s not that I didn’t have a curious mind when I came out of

DePauw and a desire to learn,” he said. “I just don’t think ‘purposedriven’ and ‘profit’ landed in the same sentence for me. I have to be honest with you: If I was looking for a purpose-driven job, that meant I didn’t feel I could do a job where I could make money. It would just be a getting-by job.”

He landed at Nestle, where he worked 12 years and rose to become a vice president, then in 1997 moved to an 11-year stint at Starbucks, a company whose mission is to sell responsibly produced products and invest in educational and communitybuilding causes. It was his first exposure to doing well by doing good, an achievement he ultimately accomplished by:

FINDING THE RIGHT

COMPANY: After Starbucks, Alling spent almost six years as chief operating officer at wireless communications company T-Mobile USA and was not looking for a job when he was headhunted by TOMS Shoes. He was reluctant to move from Seattle to Southern California, but after a conversation with TOMS’ founder Blake Mycoskie, “I was in, hook, line and sinker.”

Mycoskie started TOMS in 2006 with a plan to produce casual footwear and, for every pair sold, give a pair of shoes to a needy child living in a developing country. TOMS has given 97 million pairs of shoes away since.

Alling was drawn by the company’s purpose – to improve lives – as well as its leaders, finding that “genuinely good, committed people are drawn to companies with a purpose,” he said.

RECOGNIZING “THERE IS NO MISSION WITHOUT

MARGIN”: TOMS was struggling financially when the owners, then Mycoskie and Bain Capital, brought Alling in to tighten business operations.

That included some difficult choices, including laying off employees and making other cuts. “Doing that in any company

doing good

is hard, but in a purpose-driven company, you have to go back to the mission of the company,” Alling said. “And if the business aspects of the company aren’t working, we have to make sure we do something to make that a sustainable business so that we can continue to fulfill our mission of improving lives.”

Alling left TOMS at the end of 2019, when its creditors agreed to take over the company in exchange for restructuring its debt.

KEEPING THE CUSTOMER

IN MIND: “It’s naïve to think you can only pick your shareholders as your key constituent and do things only to maximize your share price without doing something to endear and engender support from your customers,” Alling said. “So by doing good in that broader ecosystem of contact, you should put yourself in a position where you’re driving your share price up, where you’re driving your business up, because people are loyal to you. Your business partners are loyal. Your customers are more loyal. Your employees are more loyal and more engaged, and they help lift your results.” that “if you’re doing right by your people, you will do well financially. …

“An executive has a tremendous responsibility to recognize and work for the people on the front line of the organization. … While they may not get the notoriety, if you’re set up right, they’re set up to be the stars of the show, and they will be engaged and inspired and really believe in your purpose, believe in your mission and help you to continue to drive that forward.”

BEING RESPONSIVE: TOMS changed its giving model while Alling worked there, largely in response, he said, to the suggestions of the organizations that helped TOMS give away shoes.

The giving partners wanted the company to expand its largesse to other needed items and services, he said. While the company still gives away shoes, TOMS now dedicates a third of its net profits to provide clean drinking water; pay for sight-saving surgeries and eyeglasses; advocate for measures to end gun violence; support organizations that battle community violence and mental illness; and promote educational opportunities to children in poverty.

In addition, the company, which was criticized for creating dependency on its shoes but failing to create jobs where they were needed, responded by building

DOING RIGHT BY YOUR EMPLOYEES TOO: Alling said that, while at Starbucks, he recognized

manufacturing plants in several countries where shoes are distributed.

STAYING COMMITTED: “The last thing you want to do,” Alling said, “is create a sustainable model, have giving partners build an infrastructure around that model and then say ‘hey, we’re bored with this; we’re going to step away.’”

Fulfilling the philanthropic mission in a sustainable way means “embracing criticism, seeking feedback and then not getting defensive,” he said. It also means maintaining the philanthropic commitment even during financial troubles.

“It would be difficult to do good if you’re not willing to stay committed to doing good in the hard times,” he said. “… It’s not necessarily easy to stay the course in the difficult times, but if you choose not to, it’s very hard to get back on that course after having taken a tour off and gone off in a separate direction and then try to come back. It’s just really difficult to have trust and credibility when you do that.”

Howto

By Mary Dieter

This is the story of how Tip Moody gave away his life.

It’s the story of how his promising career in power politics was halted – relinquished, really – because the 1982 graduate made a choice. And it’s the story of how he is reckoning with the mistake that held him in thrall for nearly half of his 60 years.

Moody was a bored junior executive at an Indiana department store when a friend beckoned: Join her at the National Republican Senatorial Committee. Moody, who majored in political science, heeded her invitation and in the mid-1980s headed to Washington D.C., where he got a job writing fundraising letters for the committee.

About 18 months in, he was recruited to raise money for Bob Dole’s ill-fated campaign for president. The candidate quit in early 1988, leaving Moody “in a period of flux” until another friend invited him to help clean out the U.S. Senate office of Dan Quayle ’69, the 1988 vice presidential nominee, and, after Quayle’s election, to work on the inaugural committee. Then Moody worked a year for the Republican National Committee.

Along the way, he tried methamphetamines. “It was in a sexual situation … For the gay population in big cities on the East Coast, it was starting to become a part of their social life and, of course, sex was a part of social life,” he said.

Photo: Frank Simkonis

He recalled thinking, “‘I like this; I need this more often.’ So I’m going to say the addiction began with the first-time use.”

For a while, his drug use didn’t affect his work, he said. But as he worked a series of private-sector jobs, it took its toll. An employer tried her version of therapy, refusing to pay him so he couldn’t afford to buy drugs. His family staged an intervention and forced him to enter a locked-down rehabilitation program. A friend offered him a place to stay until Moody’s behavior became intolerable. Meanwhile, his habit was costing $1,000 a month.

“I was good at my job and I gave it away,” he said. “… I actually gave my life away.”

In 2000, when his father had a stroke, Moody moved to Kentucky to help out. He stopped using meth – “when you have no contacts and no cash, you should be living drug-free” – and switched to alcohol. He found work, and the drinking continued. Then he went to graduate school, and the drinking continued. “Then my drug use started again,” he said. “And when that started again, that’s when everything swirled out of control. It had spiraled out of control previously, but there was always some place to land, only this time it was really descent into maelstrom.”

He was arrested for possession in April 2017 and again in July; in May 2018 he pleaded guilty to one felony and made an Alford plea, a guilty plea but a claim of innocence, on the second. He was sentenced to two years’ probation.

“Daily life didn’t change, and that was a real mistake on my part,” he said. Three months later, “I didn’t use my turn signal and I was pulled over and again I had something in my pocket,” he said. Moody pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor charge, and the judge sentenced him to 120 days in jail.

reckon with the past

“That was my ‘qualifying event’ that made me step back and say, you know what? You really have reached rock bottom,” Moody said. “… I had to run into a brick wall full stop before I would ever think about the harm and the sorrow and the pain that I had put around me, primarily on my mother.” He spent hours thinking and more hours putting his thoughts into letters he sent to his mother, who had lived alone since his father died. After 90 days, Moody was released early for good behavior and, on a cold November 2018 Saturday that he said was simultaneously heartbreaking and joyful, his 87-year-old mother came to fetch him. He promptly deleted 200 contacts from his phone, and has not used drugs or alcohol since.

Moody, whose father was a United Methodist minister, said “the good Lord gives me that strength every day. … Having grown up the progeny of clergy, I always knew the precepts that were necessary for a healthy life but, in the mind of an addict, you’re always greater than your addiction. I finally had to learn the true meaning of surrender. … I’m not as smart, I’m not as good, I’m not as great, I’m not as powerful as I always thought I am.”

He’s not one for programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous, he said, but therapy has helped him figure out what drove him to use meth and alcohol. He has apologized to many of the people he harmed; some have rebuffed him but many have supported his journey. He is “doing my best to forgive myself” and learning to be humble.

“You get used to – at least I did – being wanted and being recognized and being appreciated and that becomes a part of your life and it sometimes becomes difficult to remain humble about it,” Moody said. “It just becomes a given; you expect it. Part of that humility is understanding what it is that you’ve done wrong, how you’ve affected people directly.”

He still smokes a pack of cigarettes and drinks two liters of Mountain Dew every day, addictions that “I fully realize are harmful. But they don’t destroy the ones around me. So I have become stronger.”

He volunteered at a recovery center until the pandemic hit and hopes to find a job when it is over, though that “is a Sisyphean task for any convicted felon – especially one with a professional career,” he said. He recently volunteered for the League of Women Voters, which seeks to change the Kentucky Constitution so a felon’s right to vote is automatically restored upon completion of his or her sentence. Moody’s voting rights, and those of 140,000 other Kentuckians convicted of nonviolent offenses, were restored by Gov. Andy Beshear’s December 2019 executive order.

Moody said he mourns the life he lost, but does not regret what happened. “If you live with any regret, it means you didn’t learn the lessons of the experience,” he said. “So I can be sad about it. But I certainly can’t regret it.”

Howto die peacefully By Mary Dieter

They are the last words one wants to hear from a doctor: “It’s terminal.”

“There’s fear. There’s panic. There are the ‘what ifs?’” said Julianne “J” Miranda, a certified end-of-life coach and a part-time faculty member in DePauw’s university studies program. “When a person is first facing that diagnosis … it’s really about first acknowledging what’s present in this moment for you.

“One of the challenges that we have culturally and societally in dealing with death, and grief as well, is that we see it as a process that leads somewhere. And that’s really counterintuitive to what is needed in the moment of anguish, if you will, or what’s needed in the moment of recognition.”

Miranda helps clients – people facing death or their loved ones – by listening, asking questions, delving into what is important to them under the circumstances. She takes it slow – “this is not a process that can be rushed” – and “a lot of those values, a lot of those concerns, a lot of those wishes will emerge.”

Her role, she said, is to “be a companion, to be a guide, to be a witness and to really help the person ask the question and live into the answers. I could tell you what I think and it doesn’t mean anything. … Allowing them to ask and answer their own questions brings them closer to what they value, to what is important to them, to them owning their perspective on death and their perspective on the relationships they have with others in the process of dying.”

Ideally, people should make decisions about their death when they’re healthy, and she works with healthy clients who are doing just that, she said. “We’re biological entities; we can’t really control how the body dies. But we can think about quality of life and end of life, so that’s a large part of what I try to do with individuals and families, even before a diagnosis.”

She asks clients, “What does a good death look like for you? What would it mean for you to have a peaceful death, to have a loving death? And so talking about what you want your family to know, who is the person who will make decisions for you when you can’t – that’s really called the advanced care planning process. And that’s a large part of what I do with individuals and families.”

But “the fundamental hurdle is people don’t want to talk about death,” she said. “We’re afraid of it. We’ve stigmatized it. We made it uncomfortable.”

A good death, she said, “is well prepared. … All those things that we need and want to say in terms of closure, with those other parts of our life, those become possible when we think about death. I think when we become more in control of all the parts we can control – obviously we can’t control how the body dies – we can control our mind, our spirit, our attitude. When we have that control, fear lessens. …

“All of the work that we have to do toward a peaceful death is within … There are wonderful resources about death and dying, but there’s no better expert on your life than you.”

Photo: Brittney Way

LEAVING A DEPAUW LEGACY CARING FOR STUDENT NEEDS

From our student days to today, we’ve appreciated the fact that the broad and strong foundations of our adulthoods were significantly and positively influenced by DePauw. We decided to make an investment in a life insurance policy naming DePauw University as beneficiary, allowing us to make a gift that could be meaningful to DePauw in the long term, yet would have a manageable out-ofpocket impact for us in the short term. – Jim Emison ’71 and Kathy Holmes Emison ’72 The experiences I’ve gained through my liberal arts education have shaped me into a well-rounded individual who can think critically, communicate effectively and contribute great work ethic to a team. Please know how much of an impact your support for DePauw’s students has and will have on my time here. – Tyler Hufford ’22

CONTINUING STUDENT SUCCESS

LEADING THE DEPAUW WAY

DePauw gave me the opportunity to explore my interests, to learn from the experiences of others around the world during my winter term trips and to share my passion for service. Giving back looks different to everyone but I choose to make an annual gift to DePauw through my employer’s matching gift program, multiplying the impact I make each year for DePauw’s students. – Jessica Anderson ’02 Without your generosity, I would not have been able to attend DePauw, and I am forever grateful for your support. In my time at DePauw, I have been blessed to have amazing opportunities such as undergraduate research and attending a winter-term trip to Ecuador where I worked in medical clinics in underdeveloped areas. – Claire Jarrett ’21