Architectural research is essential to the future design of resilient structures and communities. Future designs must support architecture that can withstand various stressors and disruptions. Studying the past, present, and future systems that contribute to “resilience” can yield new knowledge for future design thinking. The research in this book engages with the topic of resiliece through one of the following themes:

CLIMATE: Climate change, energy, and natural resource resilience

CITIES: City, community, and social resilience.

HEALTH: Healthy spaces and cities, spaces for human resilience

Each of these themes is broad and can be interpreted in various ways. The included projects were completed during a research-based Undergraduate Capstone Project in Architectural Studies. Students establish a solid foundation of the research topic and write a literature review in their rst term. During the second term, the focus shifts to developing and implementing a speci c inquiry method to further investigate their research question.

The topic of resilience yielded a productive range of inquiry across our group this year. With many topical overlaps in their work, this class was incredibly supportive of one another, engaging in critical dialogue around these important questions. This year, the Architectural Studies graduating cohort investigated the impact of buildings on the resilience of communities and cities, the systemic effect of architecture and the built environment on health, and how cities are made more resilient over time, through architecture. Their projects are only the beginning of lifelong inquiry and change-making.

-Jacklynn Niemiec, Assistant Professor + Capstone Advisor

CLIMATE

Kelly Owens: Adaptive Facades

I. The Reduction of Building Energy Consumption through Adaptive Facades

II. Dynamic Skins: A Study of Adaptive Facade Design

Alex Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

I. Rethinking Place and Material Use in the Regenerative Architecture Paradigm

II. Creating Contexts

CITIES

Jaquelin M. Lara: Community and Cultural Resilience

I. Community Resilience to Changing Environments in South Philadelphia Mexican Neighborhoods

II. Portraits of South Philadelphia’s Mexican Roots and Identity

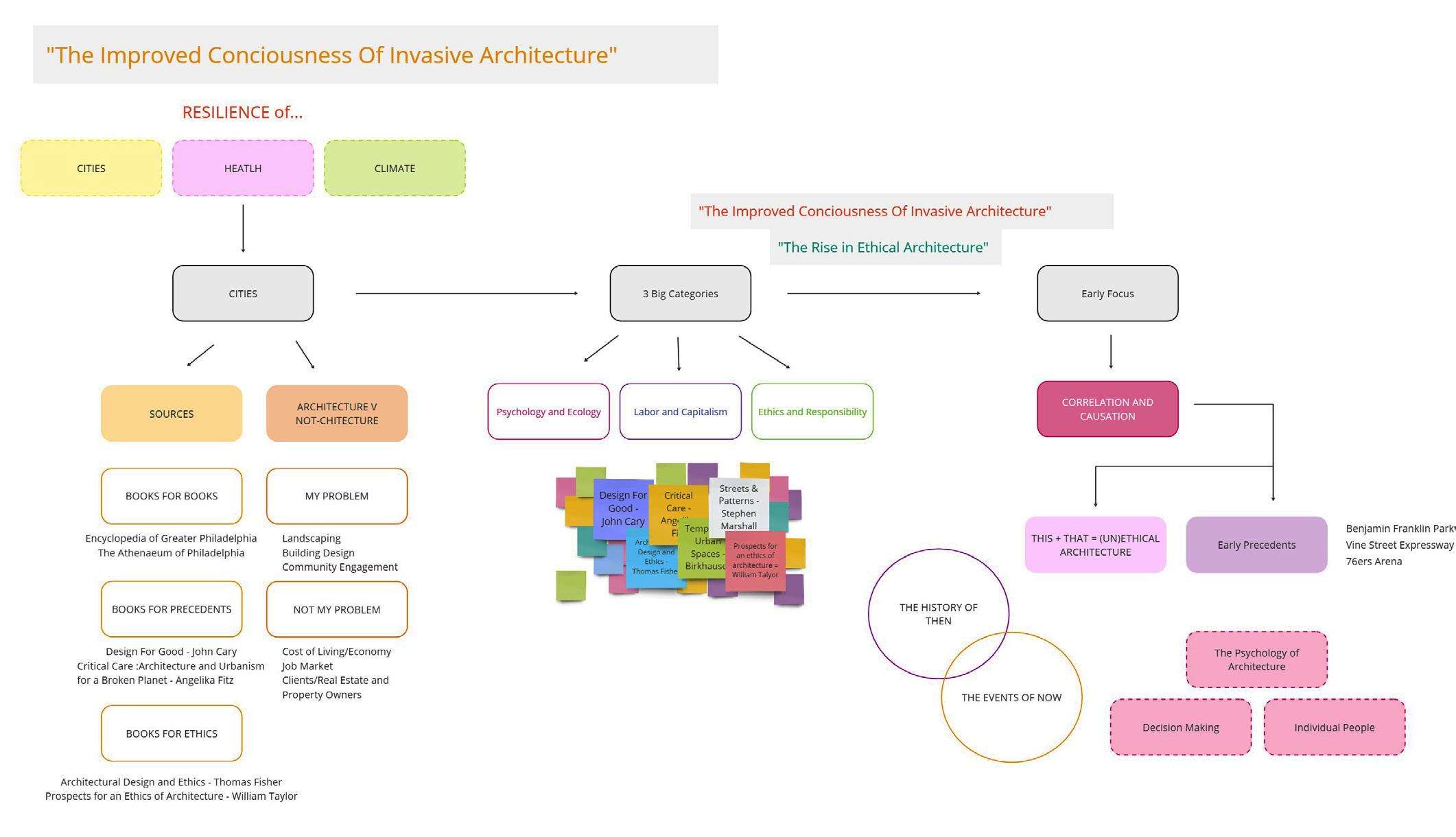

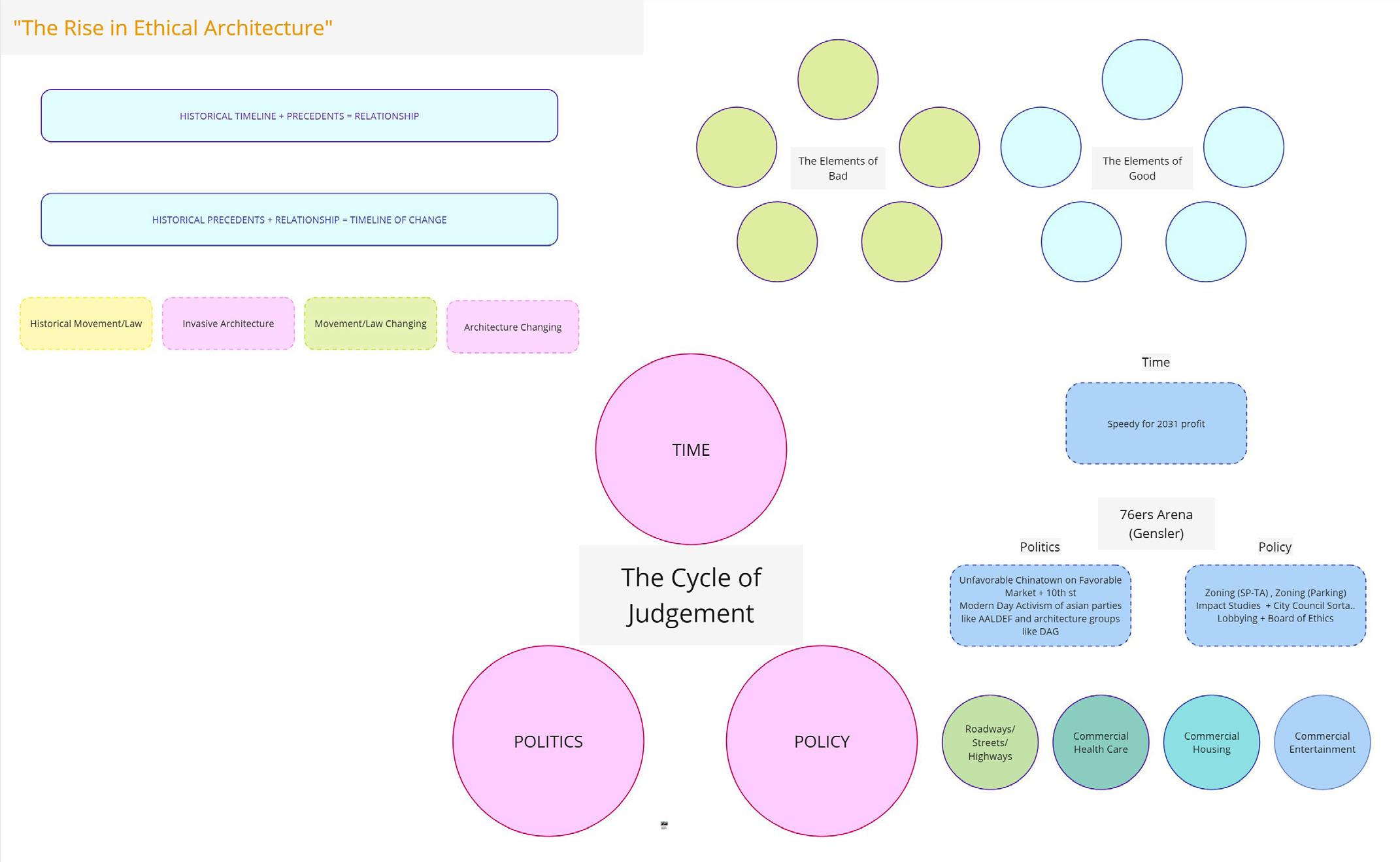

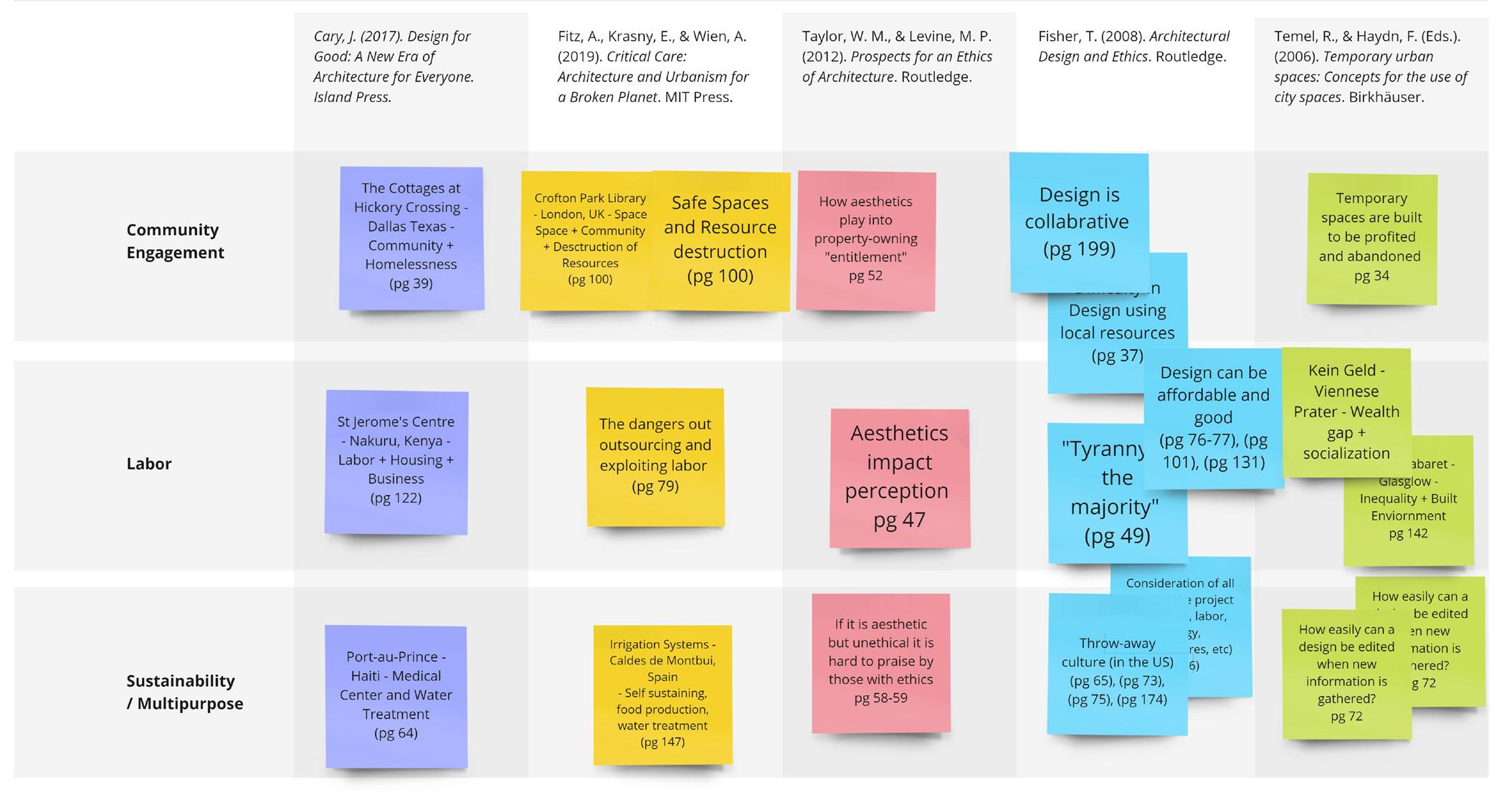

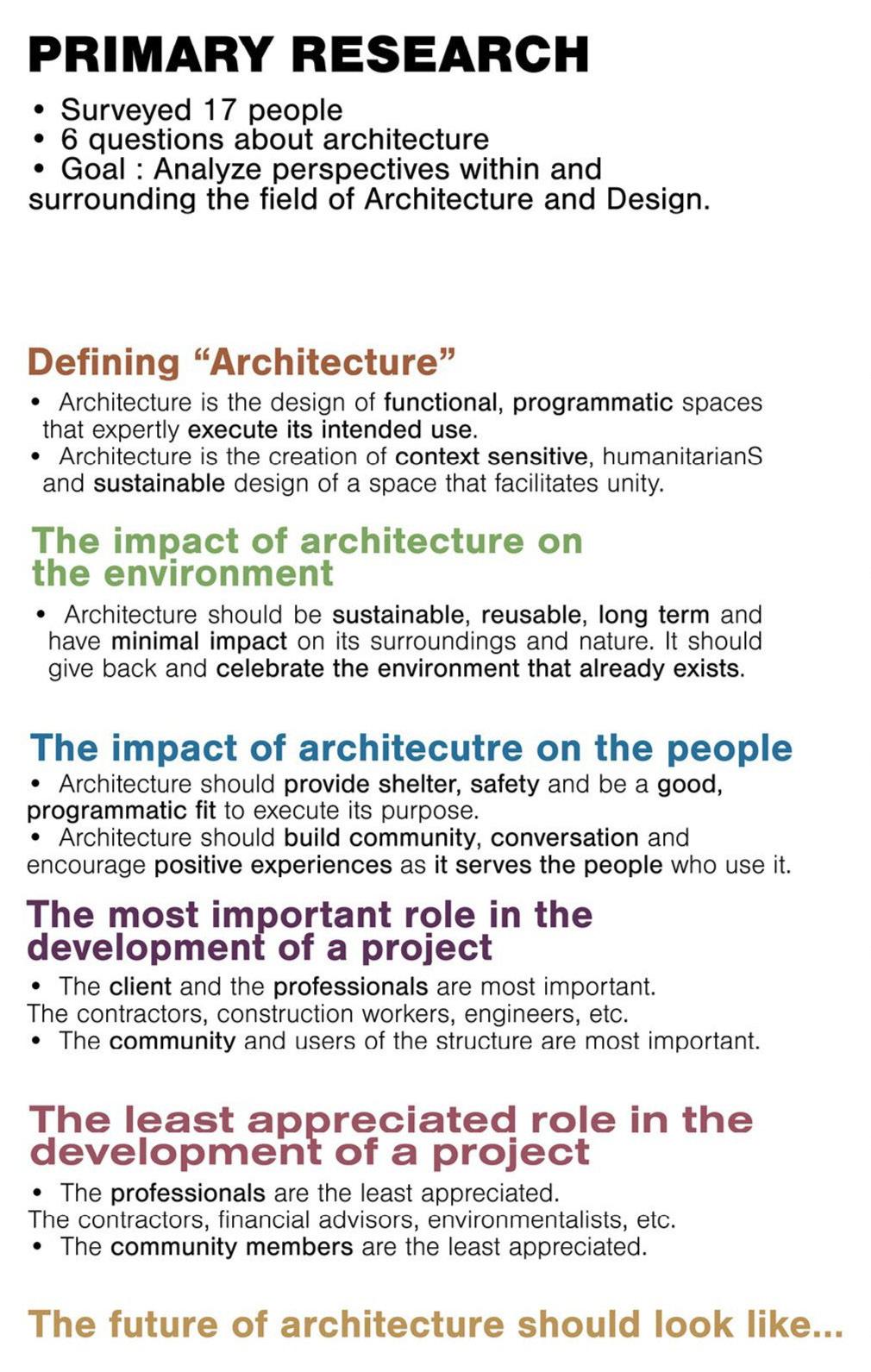

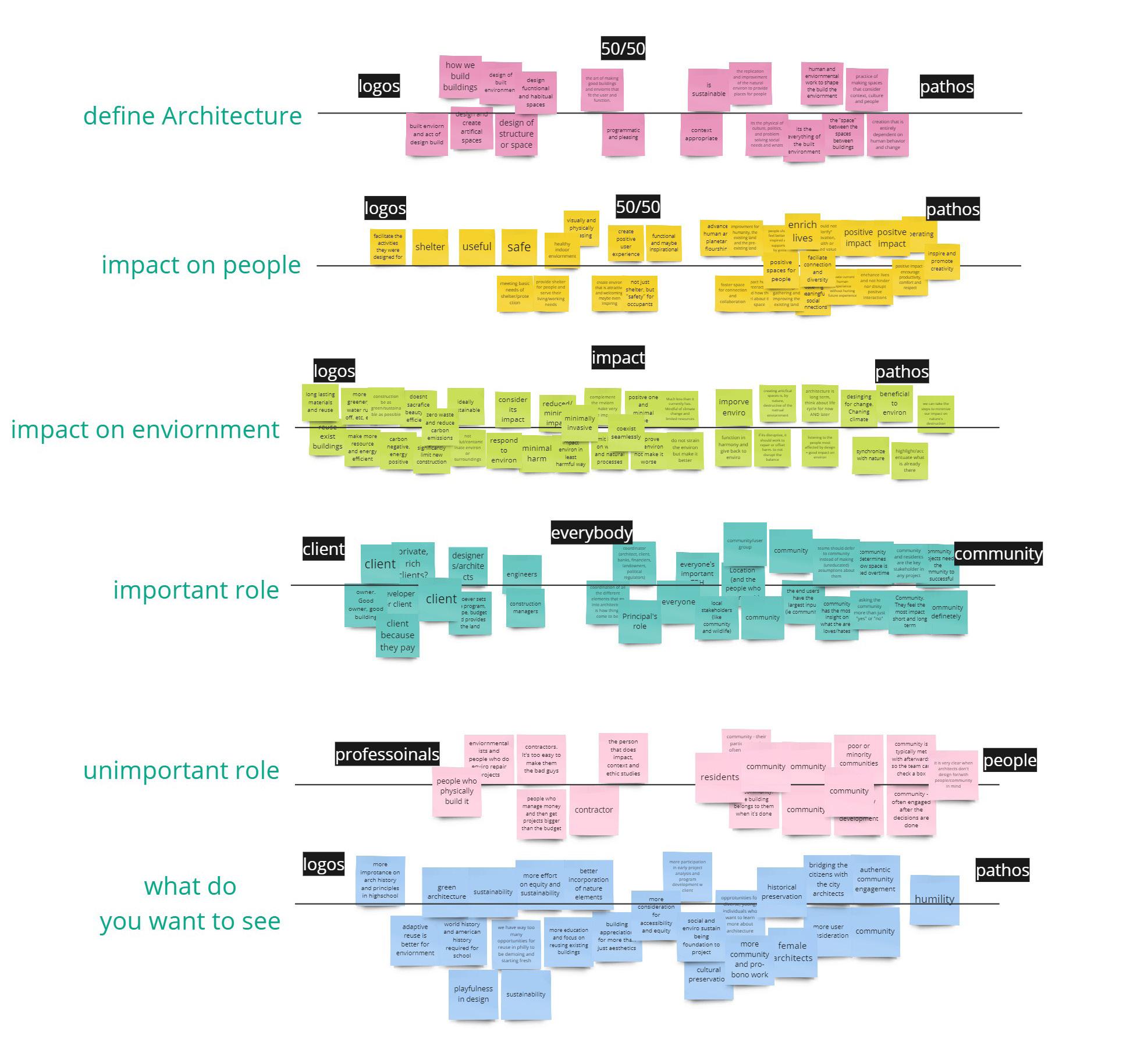

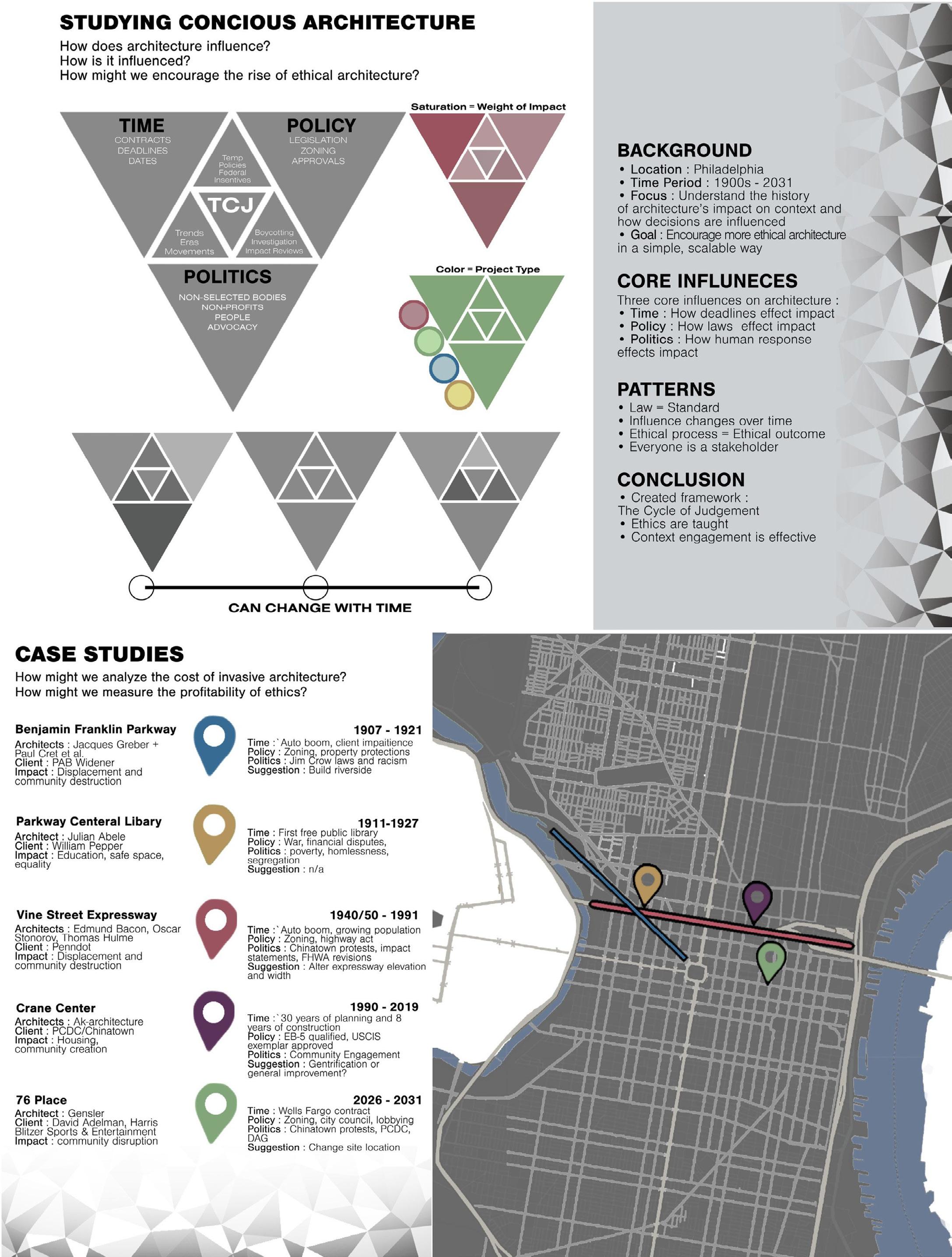

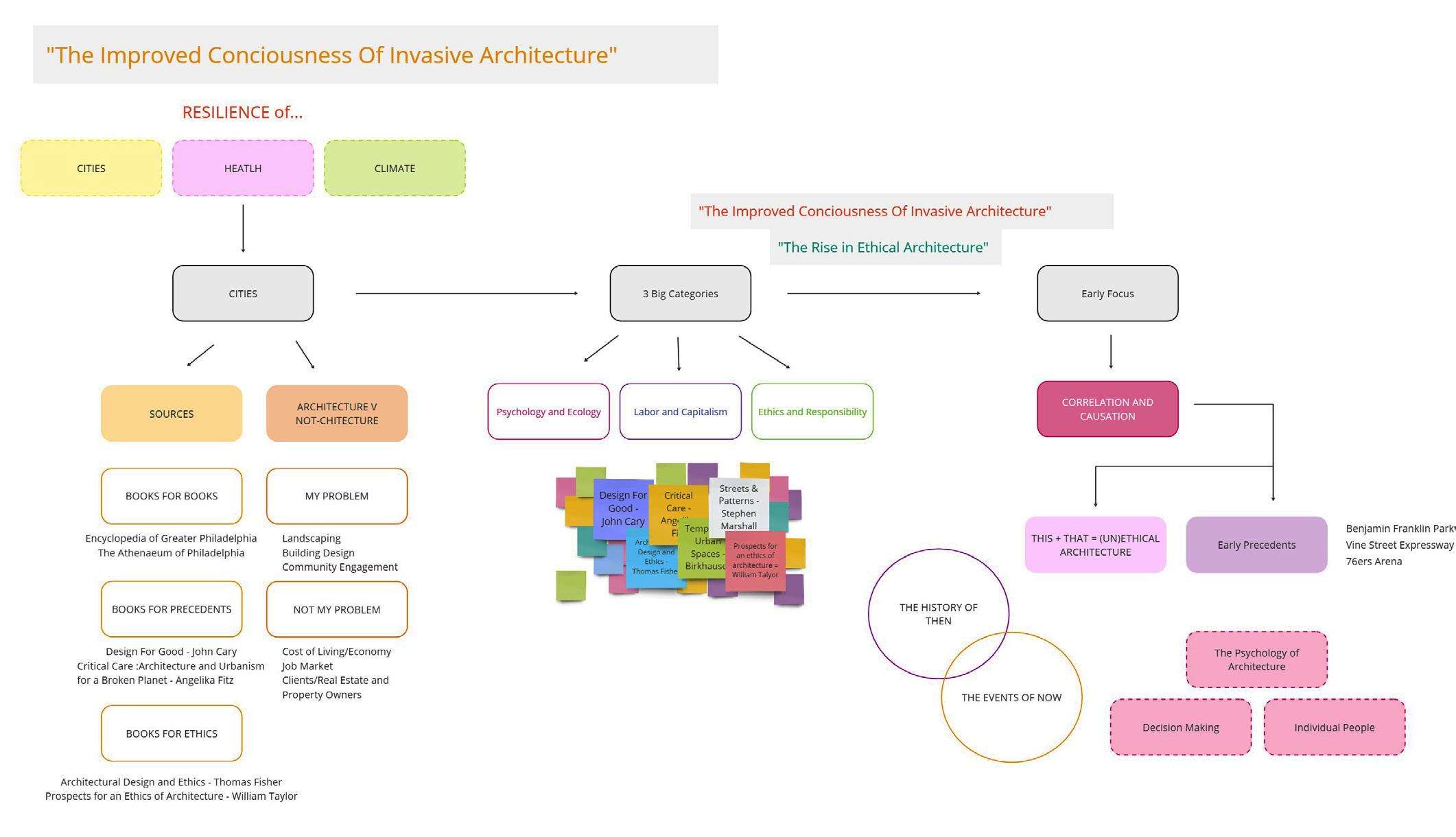

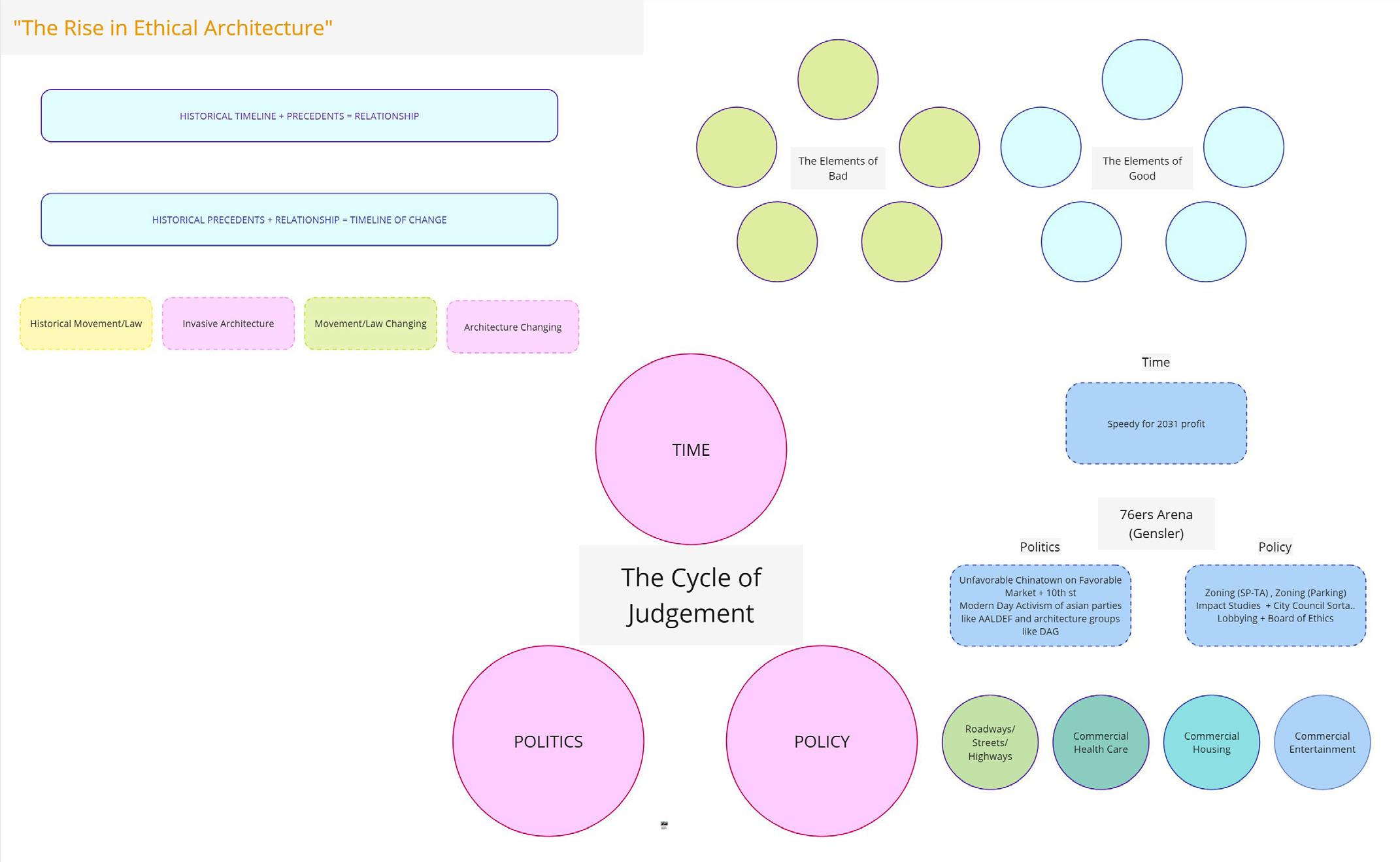

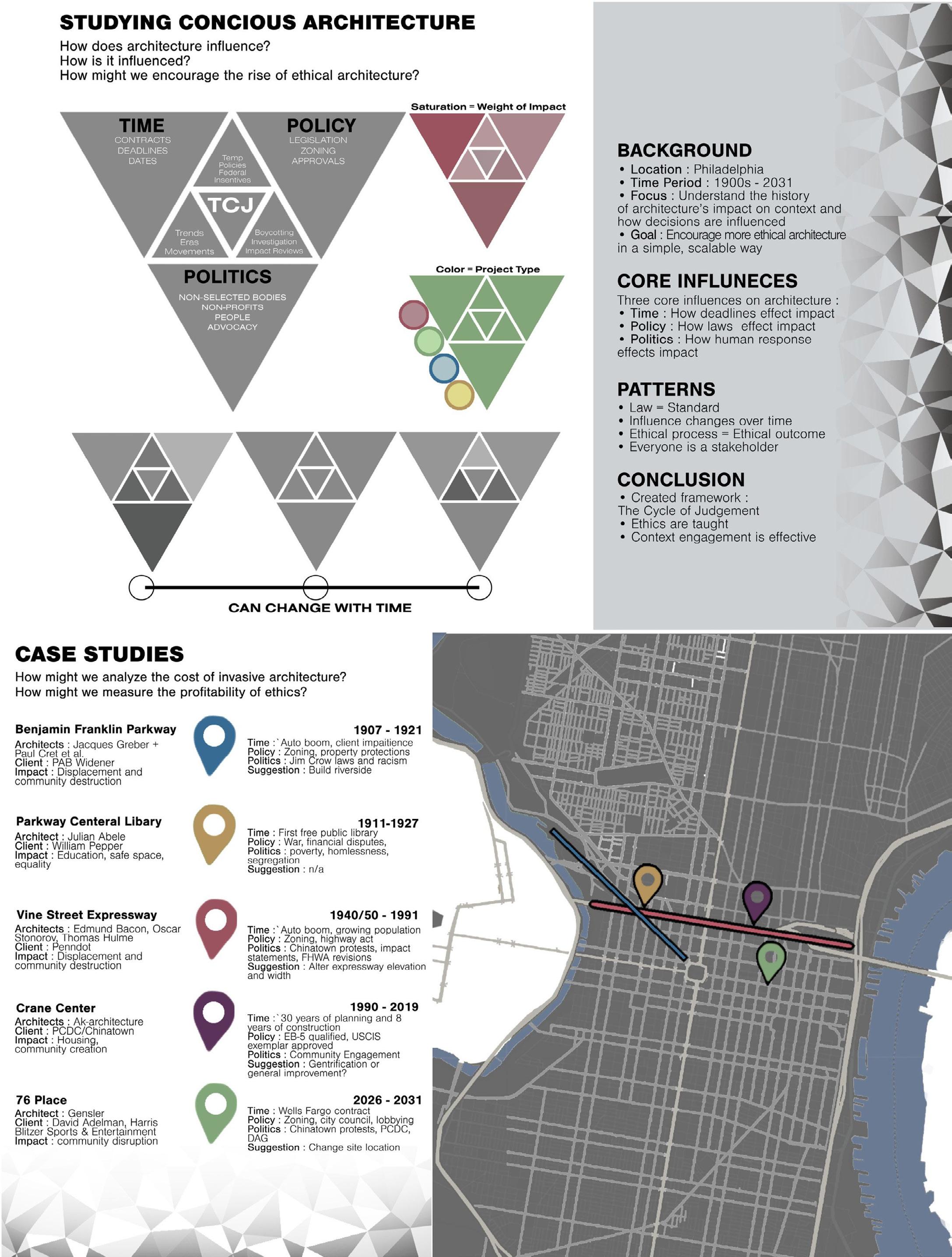

Janet-Nicole Riddick: The Ethics of Architecture

I. The Rise of Ethical Architecture

II. Studying Concious Architecture

HEALTH

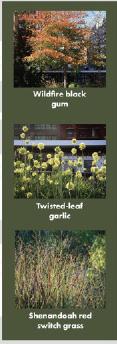

Hannah Souba: Urban Green Space and Well-Being

I. The Future of Urban Green Spaces in the Age of Density Resilience

II. The Future of Urban Green Spaces in the Age of Density Resilience

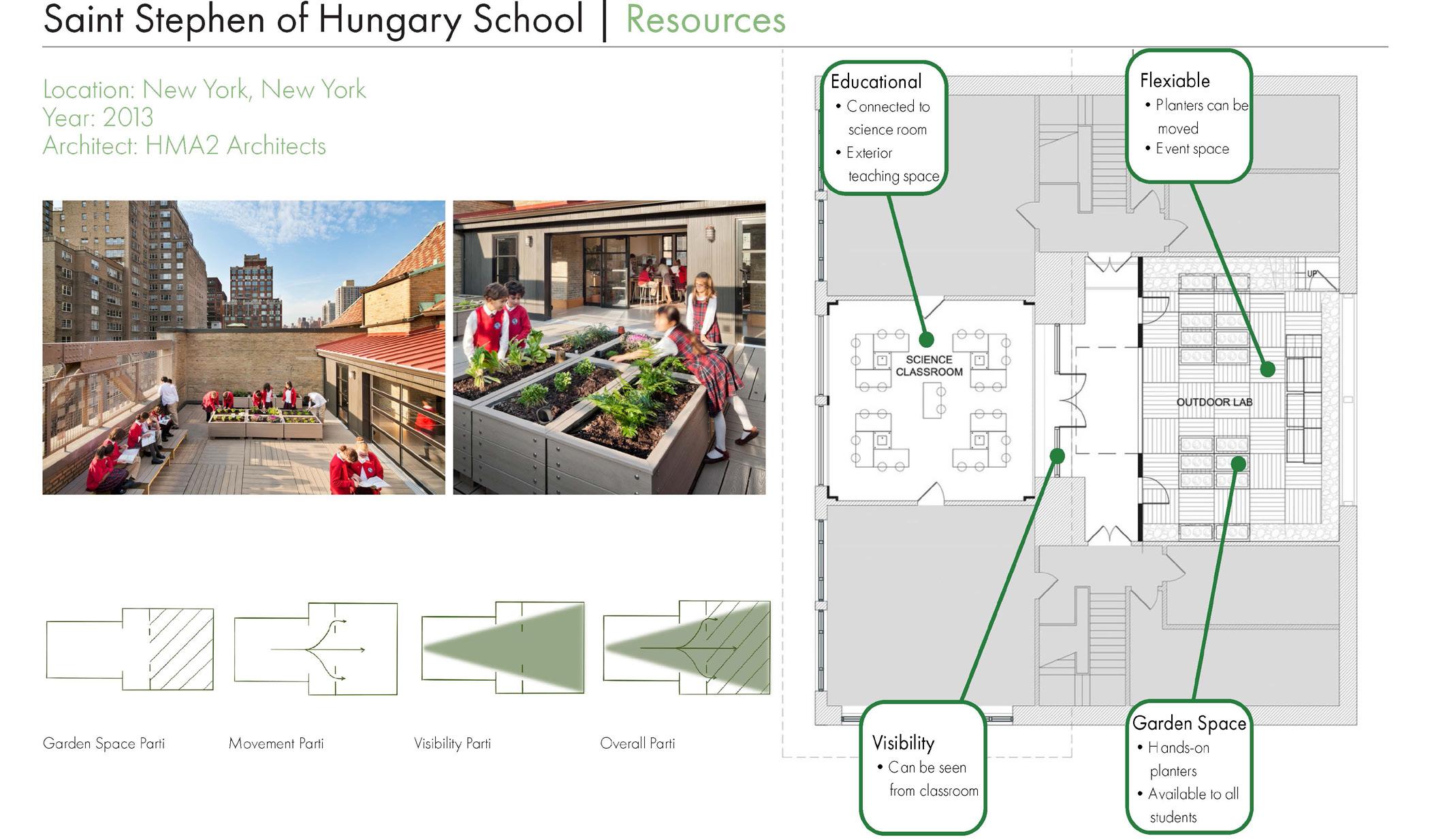

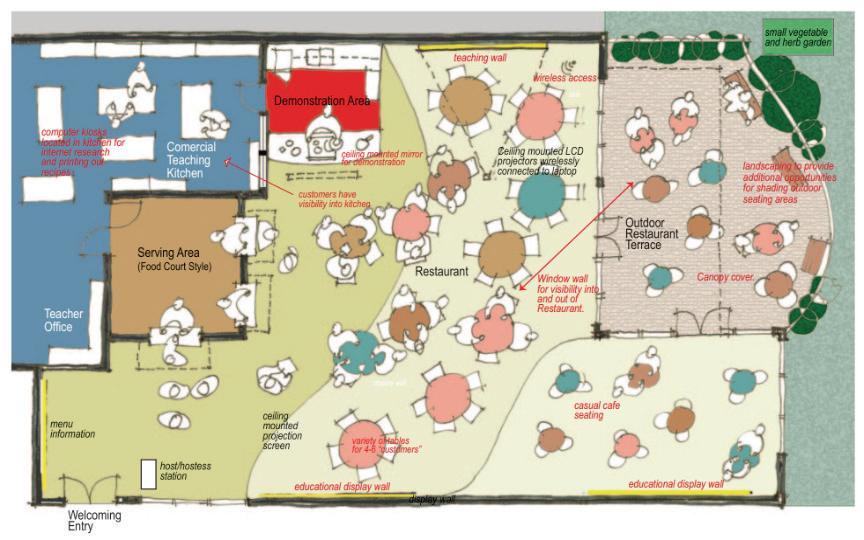

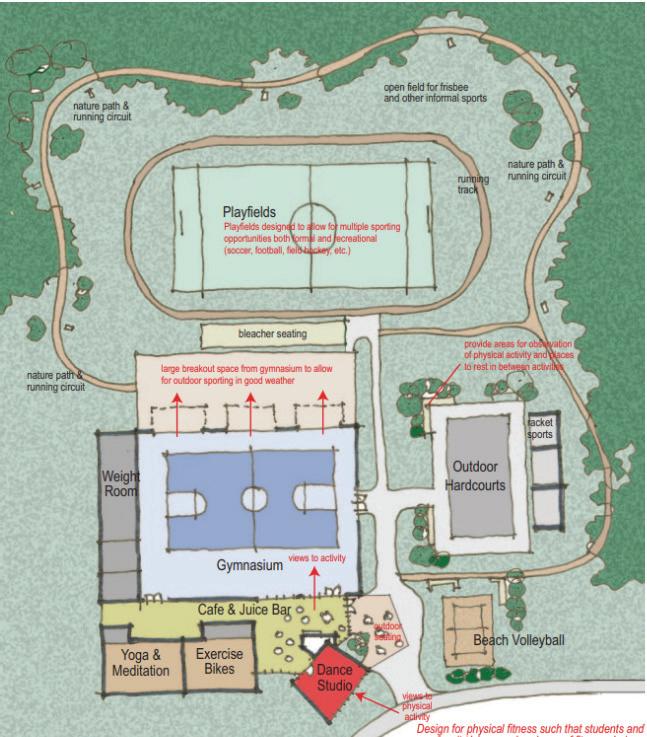

Lydia Janik: School Design and Health

I. The In uence of School Architecture and Design Choices on Student Health Practices

II. The In uence of School Architecture and Design Choices on Student Health Practices

07 27 51 91 107 71

4

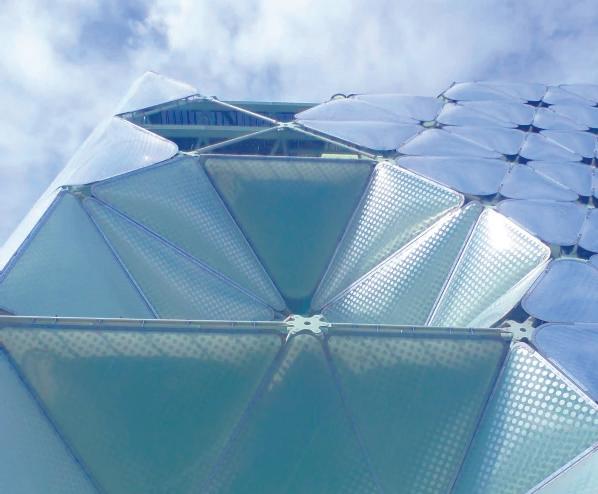

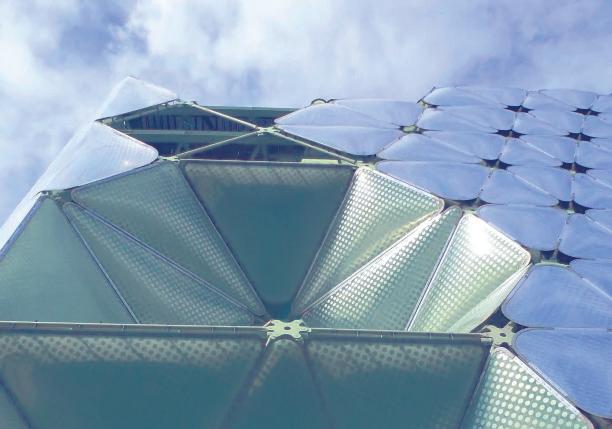

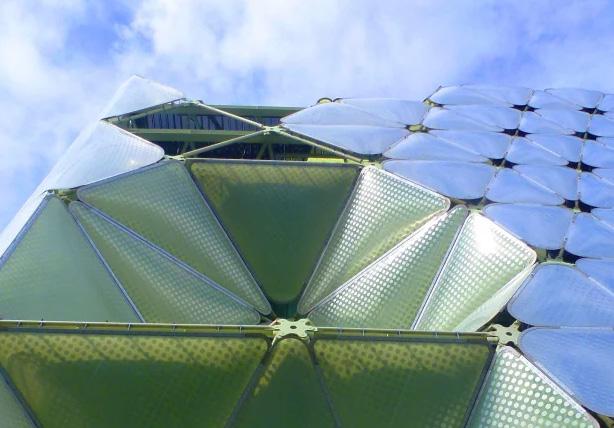

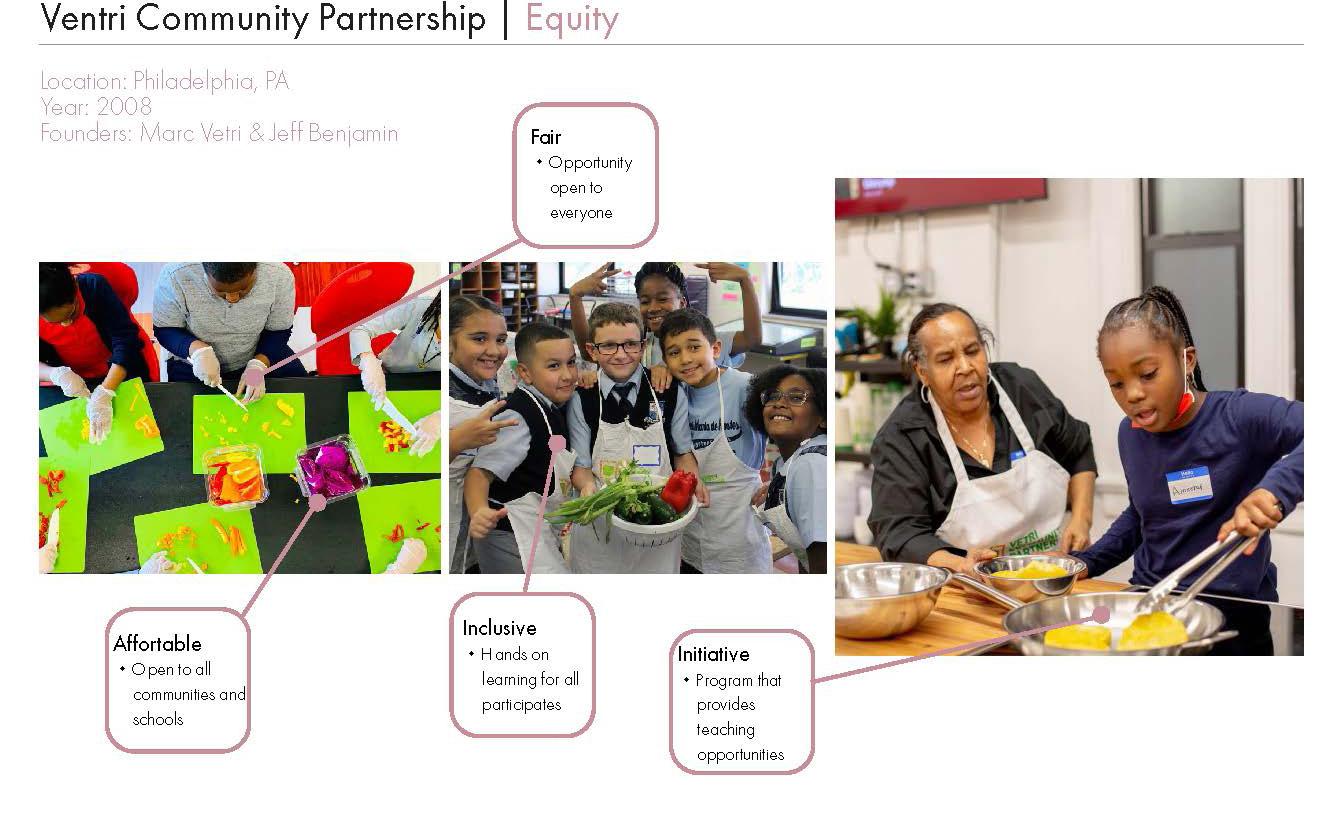

Image Sources: Enric Ruiz-Geli (left) New York Times (right)

CLIMATE

Climate resilience focuses on the design of buildings and communities that can adapt to changing climate conditions. Research in this area may involve developing innovative construction materials, sustainable design strategies, or technologies to enhance architecture’s resilience to climate change. The research may consider high and low-tech developments, historic and vernacular examples, new material processes, maintenance, energy generation, ‘smart’ buildings, design futures, or how arti cial intelligence has begun to play a role in the resilience of the built environment.

5

6 Owens: Adaptive Facades

Adaptive Facades

KELLY OWENS

Bachelor of Science in Architectural Studies

Interdisciplinary Focus in Real Estate Management and Development

7 Climate

PART I: The Reduction of Building Energy Consumption Through Adaptive Facades

KELLY OWENS

Keywords: Facade, Adaptability, Climate, Performance, Energy

In the face of climate change and the imperative of sustainable urban development, the concept of adaptive facades has emerged as a promising avenue to reduce building energy consumption and enhance occupant comfort. Drawing parallels from the natural phenomenon of homeostasis, wherein living organisms adapt to internal and external conditions, adaptive facades dynamically respond to environmental stimuli. This literature review synthesizes existing research on adaptive facades, exploring their role in sustainable building design. It examines the evolution of adaptable architecture, tracing its historical roots and highlighting contemporary approaches such as biomimicry and kineticism. The review underscores the interplay between facade design, thermal regulation, and material choices in achieving energy efficiency and resilience to climatic changes. Despite the demonstrated benefits, challenges remain in terms of cost-effectiveness, integration with existing structures, and long-term durability. However, as research advances and awareness grows, adaptive facades hold immense potential to transform mainstream building practices towards a more sustainable future.

INTRODUCTION

In nature, all living things can adapt to internal conditions while enduring changing ecological conditions. This process is called Homeostasis. Like living beings, buildings go through Homeostasis as well to keep their users comfortable. However, climate pressures make this process more grueling in an ever-changing environment.

The global imperative to address climate change and achieve sustainable urban development has intensified research efforts in building design and energy efficiency. One significant avenue for reducing building energy consumption is the incorporation of adaptive facades. Adaptive facades, also known as smart or responsive facades, have garnered attention for their potential to dynamically respond to external environmental conditions, optimize energy performance, and enhance occupant comfort.

This literature review synthesizes existing research on the role of adaptive facades in reducing building energy consumption.

ADAPTABLE ARCHITECTURE

The act of altering something or someone’s behavior to fit a new objective or circumstance is called adaptation. Many entities adapt, whether living or not. This adaptation can be either active - with external force, or passive – without external force (Schnadelbach 2010).

The term “adaptable architecture” has been generally understood as an architecture that responds to change. An architecture that is “designed to adapt to their environments, their inhabitants and objects as well as those buildings that are entirely driven by internal data” (Schnadelbach 2010, 2). Since all buildings may be “manually” altered in some way, all architecture is adaptable on some level. For example, buildings are composed of an abundance of windows that in most cases can open and close. While windows offer numerous benefits, adaptability in a building involves a comprehensive approach that considers various elements, including spatial flexibility, technological integration, and environmental sustainability. Buildings that are particularly made to adapt automatically or through human intervention—to their surroundings, their occupants, or the items within them are the focus of adaptable architecture. Occasionally this involves digital technology (sensors, actuators, controllers, and communication technologies) and can happen on several levels. This adaptability through technology is considered active. However, these reactions can also be passive.

Considering the context mentioned before, there are many reasons to build with adaptability in mind. Motivators can be related to communication and social interaction, as well as the cultural, societal, and organizational realms (Schnadelbach 2010). Perhaps an even more significant motivator for building adaptive architecture is to create positive effects on the climate. A way in which architects have found to achieve this is through façade design. More specifically, adaptive façades can reduce a building’s total energy consumption through material usage, building design methods, and practice.

8 Owens: Adaptive Facades

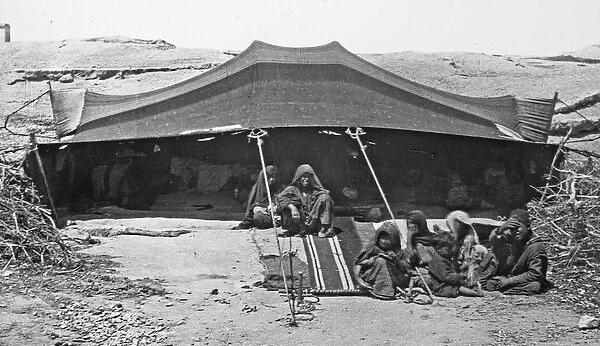

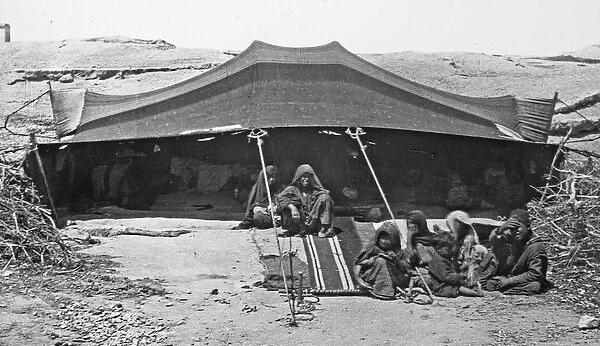

Figure 1: African Bedouin tent. Evans, Mary. Bedouin tent with family. Prints - Online. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.prints-online. com/bedouin-tent-family-14394309.html.

HISTORY

It is important to note that there has always been a human inclination to create adaptive structures. A variety of dynamic, external forces such as time, weather, human needs, etc. impact buildings and as a result, buildings need to adjust to climate and energy optimization. A 2018 journal article (Nashaat, Basma, and Waseef 2018) explains how historically, humans needed to have the ability of adaptation. People used movable shelters to protect their lives. An example that is provided is the African Bedouin tent. This tent was used by nomads who historically inhabited the Syrian and Arabian deserts. They used the tent because it was adaptable to the desert climate and was a mobile shelter, meaning that it could be deconstructed and relocated in a time of need (Figure 1). Now, both globally and locally in the United States, the built environment is composed of primarily static, fixed structures that are immobile. The reason for this lies within the construction of the building. Until recently, newly constructed buildings were not built with adaptability in mind. This approach left them static, meaning they are resistant to change, unable to adapt to evolving needs, and lack responsiveness to technological, social, or environmental advancements. More than ever, buildings are created to serve people but should also adapt to serve their needs (Nashaat, Basma, and Waseef 2018). Buildings that are designed with adaptability in mind are better positioned to endure and remain relevant over time (Melton 2023).

FACADE AND ENVELOPE

A building’s purpose has always been as a kind of protection against exterior conditions. Thus, the building envelope serves as an external shell that regulates interior temperature and upholds comfort levels within. This protective layer encloses a structure’s complete external enclosure system, which includes the foundation, floors, walls, roof, and all other elements that divide the inner space from the outside environment. The primary focus of building envelope performance is on the technological components that ensure the longevity of the building, energy efficiency, air quality, moisture control, and thermal insulation (Alhabash 2023).

Similarly, the façade is also a separation of the external and internal elements of a building. However, the façade combines the technical components with visual strategy. The quality of a building’s aesthetics, utility, and relationship to context is shown through its facade performance. The Façade design should consider things like ventilation, daylighting, views, solar management, and aesthetics (Alhabash 2023). The components of a building’s envelope or façade are a direct way to impact the internal temperatures of a building. As a result, the majority of newly constructed buildings aim to improve the interior environment of a building through façade design (Nashaat, Basma, and Waseef 2018). There are various ways in which the façade and envelope of a building are interdependent and can work hand in hand to lower energy consumption.

9 Climate

THERMAL REGULATION

Again, the façade acts as a barrier between the exterior and interior spaces. Although heat and air can be drawn in through the façade, they can also be lost. The greater the façade’s thermal insulation is, the smaller the need for heating systems. This active air loss from a building’s façade leads to constant energy consumption. A building’s facade is responsible for nearly 40% of a building’s thermal temperature with heat loss in the winter and heat gain in the summer (Barozzi 2016). This is why the building sector records the highest energy consumption (even more than transportation).

In addition, The Roadmap to 2050 Report (Masi et al. 2021) revealed that an estimated 36% of the world’s global energy consumption and 39% of its energy-related carbon dioxide emissions are attributed to buildings (buildings make up 28% of services and 11% of materials and construction). The total building stock is projected to nearly double from its current 223 billion square meters to about 415 billion square meters in 2050, growing at a rate of 5.5 billion square meters annually (Masi et al. 2021). This means that, without any interference, the current built environment will continue to consume large amounts of energy. The report emphasizes that to fully decarbonize the building industry, buildings must transition from being inefficient energy users to net-zero carbon structures. These prospective energy-efficient buildings would need to source all their remaining operational energy from renewable sources. The biggest concern with this idea is the impact of the façade.

Undoubtedly, A façade has a lot of roles to play in creating a comfortable environment for the user (Knaack, Klein, Bilow, and Auer 2014). Further components must be added to the façade layer or close to it if the façade cannot satisfy the functional requirements on its own. The role of the façade also applies to the heating and cooling of a building. Active cooling may not always be necessary depending on the climate conditions and internal heat loads. Adaptable facades are one of the ways in which we/architects can encourage buildings to use renewable sources like sun, air, and wind without relying solely on heating and cooling systems.

BIOMIMICRY

An adaptive façade strategy that was developed to rely on renewable sources for power and function is called Biomimicry. Biomimicry, also known as biomimetics, is an approach to innovation and problem-solving that draws inspiration from nature’s designs, processes, and systems (Pawlyn 2016). The term “biomimicry” comes from the Greek words “bios,” meaning life, and “mimesis,” meaning to imitate. The goal of biomimicry is to emulate biological strategies, structures, and functions to create solutions for human challenges across various disciplines, including design, engineering, materials science, and sustainability (Pawlyn 2016). However, these methods are often active instead of passive.

As previously mentioned, heating and cooling systems are considered active, meaning they depend on generated external energy to operate. Passive heating and cooling within a building uses natural elements like wind or shade. Incorporating biomimicry into buildings, specifically in facade elements, allows buildings to go through Homeostasis passively (Bayhan and Karaca 2019). This process is a highly adaptive and resilient way to maintain building energy usage.

With this, the goal of incorporating biomimicry is to reduce the energy consumption of a building. Naturally, biomimicry and adaptive facades have become intertwined in sustainable building practice. Sustainable building tends to fall into a “less bad” category, meaning that it does not reverse the effects of climate change. While biomimicry in design is much more ambitious, the solutions to create sustainable buildings lie within biology (Pawlyn 2016).

Nature has created its structures by trial and error which can be translated to architecture. Genetic mutation and recombination have developed structures and other adaptations. Still, over ages, the stresses of life in all its diverse aspects—finding nutrition, thermoregulation, mating, and evading predation, among many other factors—have brutally perfected these adaptations. Of course, the process goes on, but many of the best structures we see in nature have developed throughout life as we know it. An example often replicated in biomimetic facades is honeycomb patterns (Figure 2). These adapted structures in nature often use less material as well, which is something designers have been striving for. Less is more. Efficient designs have come to light via observation of nature (Pawlyn 2016). Often, the translation of biomimetic structures is conveyed through kinetic facades.

KINETIC FACADES

There are different methods for using kinetic facades; however, the universal goals are to (1) harness solar energy for photovoltaic electricity generation, heating, inducing ventilation, and daylighting, (2) provide varying levels of thermal insulation, and (3) store energy. The combination of these factors is all in hopes of reducing the overall building energy consumption and increasing the quality of life for the user (Barozzi 2016). Kinetic facades, while efficient in reducing internal building temperatures, are still, often active processes, with kinetic energy resulting from movement or motion. This motion in kinetic facades usually involves digital technology (sensors, actuators, controllers, and communication technologies). Kinetic facades commonly use moving pieces to react to sunlight, humidity, wind, etc. (Barozzi 2016). These pieces of a system may act as shading devices, however, they are not limited to rectangular grids and flat façades. Kinetic facades focus on the envelope as an intelligent environmental system capable of exchanging information, materials, and energy. Heating and cooling systems are necessary in buildings to ensure the comfort of the users, however exterior

10 Owens: Adaptive Facades

shading systems incorporated in kinetic structures can provide equal comfort in both cold and warm climate conditions. They protect the facade from solar heat gain, reducing the need for cooling energy in warmer months. In cooler months, they reduce the energy demanded for heating.

METHOD AND PRACTICE

However, even though adaptive facades have great potential to reduce building energy consumption and improve the user’s comfort, they are still not a widely used practice (Borschewski, David, et al 2023). The established benefits and incentives are more appealing to those who have little involvement in the design process. Through their research, Borschewski and others have found that stakeholders with significant decision-making power have additional motivators in addition to the well-known benefits and drawbacks of adaptive facades. Their research highlights a case study of an adaptive facade with an integrated ventilation system which was installed in place of the conventional centralized ventilation system. The performance was compared to a building with centralized ventilation as it usually operates. Since the central duct system may be removed, this lowers the building height and, consequently, the construction’s weight. Up to 680,000 pounds of material and almost 10 feet of building height can be saved, resulting in an averted 220,000 pounds of CO2 which is equivalent to a − 7% impact on climate change. With this, it is possible to prevent 1,230,000 pounds of CO2 during use. Rentable floor space can also be increased by 4%, while the lifecycle expenses can be lowered by 512,436 dollars (Borschewski, David, et al 2023).

When discussing the benefits of adaptive façades, life cycle impacts are often at the forefront, of how the façade will withstand changes over time and continue to reduce overall building energy consumption. However, this is often not enough to persuade stakeholders to choose adaptable facades over static facades. There are ways in which construction can be less damaging to the environment and budget, specifically through local material usage.

A case study discussing the construction of twelve small residential buildings in France using only local materials decreased the overall energy consumption by a significant amount (Morel, Mesbah, Oggero, and Walker 2001). The construction of a typical concrete house was used to contrast the positive effects of the local materials. By adopting local materials, the amount of energy used in buildings decreased by up to 215% and the impact of transportation by 453%. The outcome of this project was successful. All twelve houses were built using techniques with local materials such as soil, stone, and timber. Local materials were resourced systematically to minimize the environmental impact of the project (Morel, Mesbah, Oggero, and Walker 2001).

MATERIAL

It is known that certain building materials can insulate. Dense materials such as concrete or stone are good at insulating (Cao 2019). However, this practice usually applies to static buildings, not ones that adapt to climactic change. Additionally, concrete usage raises other concerns in terms of its sustainability. Manufacturing cement that binds concrete is one of the most polluting processes in building practices (Mayo 2015). Joseph

11 Climate

Figure 2: Honeycomb façade system reacting to light. Charuau, Fabian. Hive, a family home in Surat, was inspired by the organic form of honeycomb designed by Openideas Architects. Stir World. Meghna Mehta, June 30, 2020.

Mayo explains how timber is an ideal alternative to concrete. Timber was the first building material, as it grows from the ground and is completely replenishable in a short time. On the other hand, concrete and metal are limited materials that may one day disappear altogether. The main conflict with timber construction is scale.

As the population continues to grow, there is a greater need for spaces to adapt to that, especially in urban environments, which is why it seems hard for architects and construction companies to let go of steel construction. However, replacing or incorporating more sustainable materials is possible (Mayo 2015). Even though there is little to no research on how adaptable facades can include the use of local or sustainable materials to lead us closer to a net-zero building, incorporating methods in facades that make a building more energy-efficient and resilient to climactic change is a good start.

CONCLUSION

The built environment is essential to sustainable living because, as the world changes, energy consumption and climate change have gained significant importance. The literature has shown that one of the most promising ideas for reducing energy use is through the creation of adaptive facades. These facades function as a dynamic response to environmental circumstances and go beyond simple aesthetics. Whether actively or passively,

adaptable facades have incredible data on the impacts of what is currently being tested. For example, biomimicry, kineticism, and material usage have been closely studied and have proven to have positive effects. While Borschewski and others have expressed that there tends to be a lack of acceptance of adaptive facades, the benefits project a future in which these methods are used widely. In summary, adaptive facades are changing the link between architecture and the environment and are at the forefront of sustainable building design. Adaptive facades allow for the design of buildings with improved livability, aesthetics, and economic benefits in addition to less environmental impact.

However, further research is needed to address challenges such as cost-effectiveness, integration with existing buildings, and the long-term durability of smart materials. As the field continues to evolve, integrating of adaptive facades into mainstream building practices holds great promise for achieving substantial energy savings and contributing to a more sustainable built environment. Adaptive facades mark a critical turning point in the development of tomorrow’s buildings as environmental responsibility becomes paramount.

12 Owens: Adaptive Facades

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aksamija, Ajla. Sustainable Facades: Design Methods for High-Performance Building Envelopes. 1. Aufl. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2013.

Alhabash, Alaa. “Unveiling the Difference: Façade Performance vs. Building Envelope Performance.” LinkedIn, 29 May 2023, www.linkedin.com/pulse/ unveiling-difference-fa%C3%A7ade-performance-vs-building-alaa-alhabash.

Alkhatib, H., et al. “Deployment and control of adaptive building facades for energy generation, thermal insulation, ventilation and daylighting: A Review.” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 185, 2021, p. 116331, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.116331.

Barozzi, Marta, Julian Lienhard, Alessandra Zanelli, and Carol Monticelli. “The Sustainability of Adaptive Envelopes: Developments of Kinetic Architecture.” Procedia Engineering 155 (2016): 275–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. proeng.2016.08.029.

Bayhan, Hasan Gokberk, and Ece Karaca. “SWOT Analysis of Biomimicry for Sustainable Buildings - A Literature Review of the Importance of Kinetic Architecture Applications in Sustainable Construction Projects.” IOP conference series. Materials Science and Engineering 471, no. 8 (2019): 82047–.

Borschewski, David, Michael P. Voigt, Stefan Albrecht, Daniel Roth, Matthias Kreimeyer, and Philip Leistner. 2023. “Why Are Adaptive Facades Not Widely Used in Practice? Identifying Ecological and Economical Benefits with Life Cycle Assessment.” Building and Environment 232 (March): 110069. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110069.

Cao, Lilly. “What Materials Keep Buildings Cool?” ArchDaily, August 26, 2019. https://www.archdaily.com/923445/what-materials-keep-buildings-cool.

Knaack, Ulrich, Thomas Auer, Marcel Bilow, and Tillmann Klein. Façades: Principles of Constructon. Second and revised edition. Boston: Birkhäuser, 2014.

Masi, Maurizio, Chun Sheng Goh, Joaquim E. A. Seabra, Maria Christina Rulli, and Emanuele Oddo. “Buildings: Roadmap to 2050.” A Manual for Nations to Decarbonize by Mid-Century | Roadmap to 2050, 2021. https://roadmap2050.report/buildings/.

Mayo, Joseph. Solid wood: Case studies in Mass Timber Architecture, technology, and Design. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2015. Melton, Paula. Buildings that Last: Design for adaptability, deconstruction, and Reuse. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://content.aia.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/ADR-Guide-final_0.pdf.

Morel, J.C, A Mesbah, M Oggero, and P Walker. “Building Houses with Local Materials: Means to Drastically Reduce the Environmental Impact of Construction.” Building and Environment 36, no. 10 (2001): 1119–26. https:// doi.org/10.1016/s0360-1323(00)00054-8.

Nalcaci, Gamze, and Gozde Nalcaci. “Modeling and Implementation of an Adaptive Facade Design for Energy Efficiently Buildings Based Biomimicry.” 2020 8th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid), 2020. https:// doi.org/10.1109/icsmartgrid49881.2020.9144954.

13 Climate

PART II: Dynamic Skins: A Study of Adaptive Façade Design

Exploring The Role Of Adaptive Facades In Energy Optimization And Occupant Well-Being

In what ways do adaptive facades impact the occupant and how can adaptive facades create longer life cycles for the building/more comfortable living for the occupant?

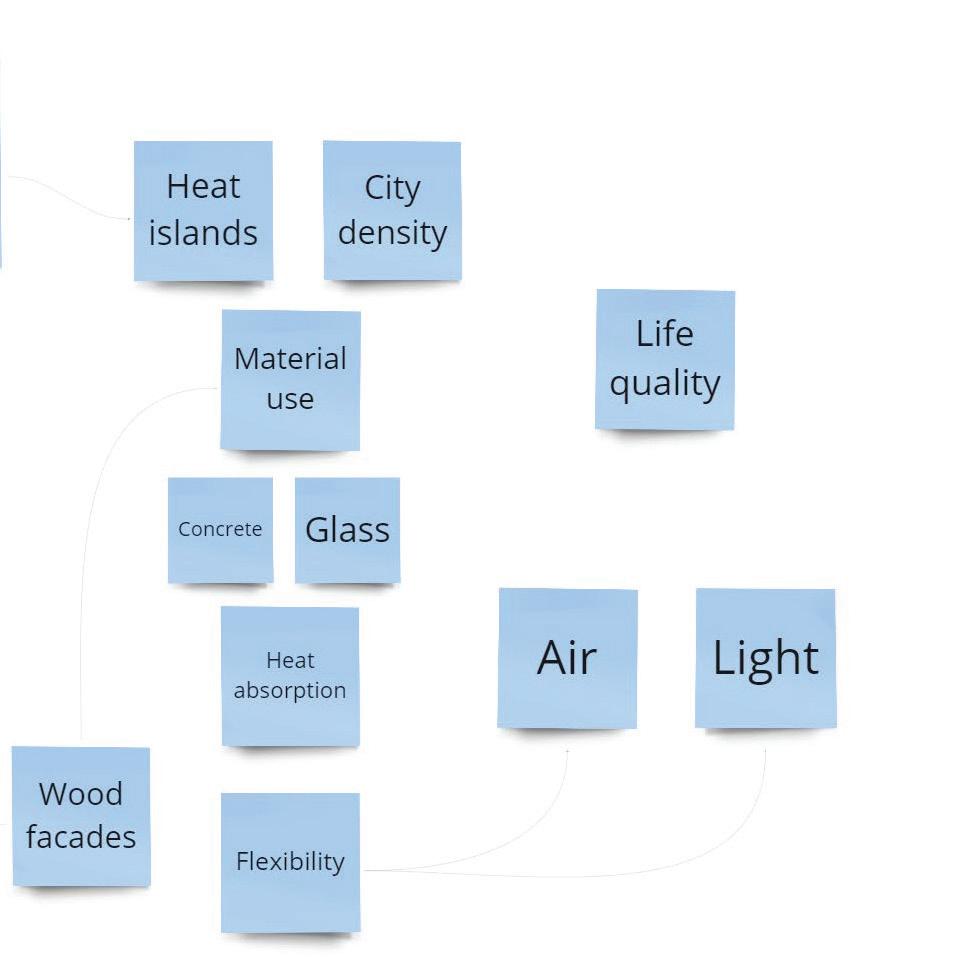

RESEARCH QUESTION

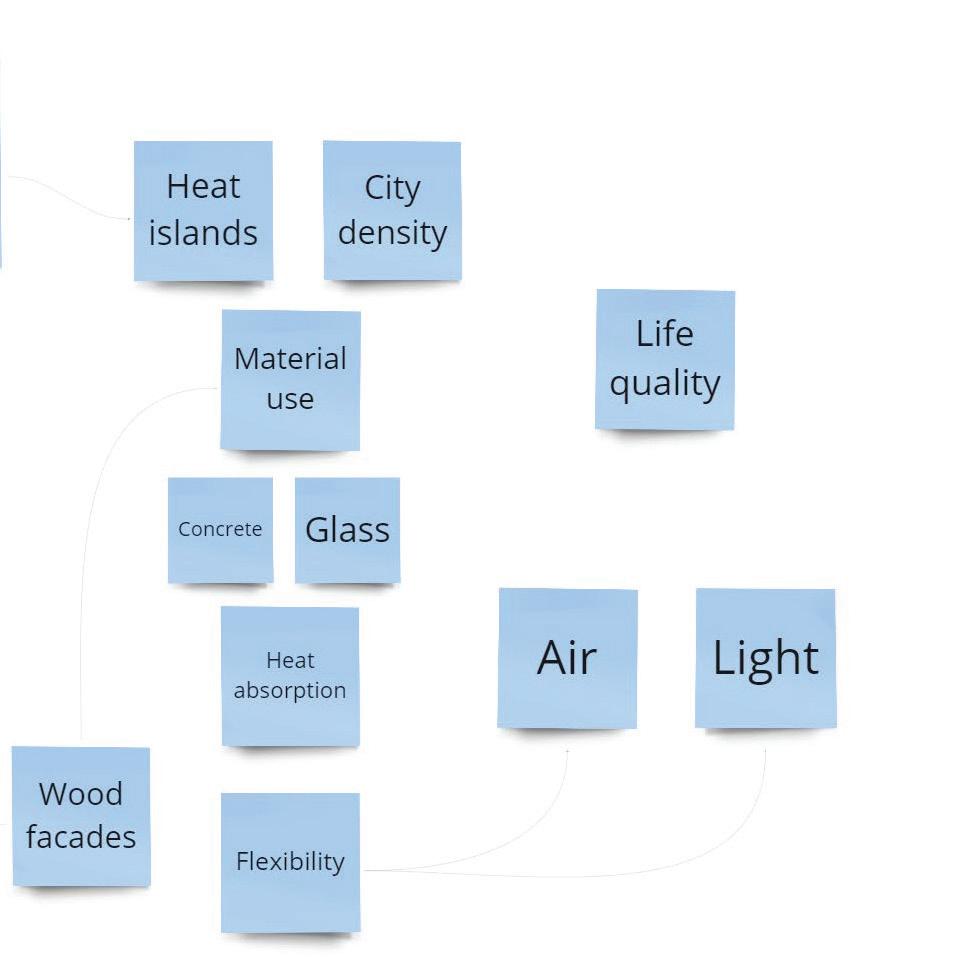

I began my exploration with a list of keywords that would be used to drive research for my topic (Figure 1). With resiliency being the over arching theme for all of the 2024 Capstone Projects, I specifically wanted to focus on resiliency in urban settings and its impact on climate. With this, I collected words like cost, heat islands, flexibility, air, light, and life quality among others. These keywords sparked my attention towards sustainable building practice and then towards kinetic facades, which is a variation of an adaptive facade. In general, the act of altering something or someone’s behavior to fit a new objective or circumstance is called adaptation. Adaptive facades are building envelopes that can adapt to changing boundary conditions and external forces.

I started my research with an interest in kinetic facades, specifically wood facades. I was initially drawn to their aesthetics, but also their ability to reduce energy use within a building. It did not take me long to realize that there are many types of adaptive facades other than wood kinetic facades. My focus switched from wood-specific facades to adaptive facades in general, although my interest in materiality seemed to carry throughout my research.

During my research, I found an interesting fact: heating and cooling systems are the #1 energy consumption of a building, accounting for approximately 40% of a building’s total energy consumption. At this point, I switched my research topic to the reduction of building energy consumption through adaptive facades. I started to think about what elements, structures, or materials could be used to expel or contain heat within a building in place of heating and cooling systems. I then looked at Adaptive facades as a broad topic with other subtopics like biomimicry, kineticism, thermal regulation, construction methods

14 Owens: Adaptive Facades

Figure 1. Word Mapping

KELLY OWENS

and practice, and materiality. These subtopics are discussed in detail in my literature review.

Through my research on how adaptive facades can reduce building energy consumption, I found that these facades are very impactful. Adaptive facades encourage buildings to use renewable sources like sun, air, and wind without relying solely on heating and cooling systems, which in turn directly impacts its occupants.

The abundance of information I had allowed me to look at adaptive facades as a broad category versus specific subcategories. This research made me wonder how adaptive facades can impact the comfort of building occupants. Based on my research, I made a list of building qualities that can improve occupant comfort levels which are: Aesthetics, Temperature, Lighting, Acoustics, and Air Quality. These qualities have direct ties to adaptive façade functions.

PROCESS AND METHODS

To further understand these qualities, I looked into WELL - a performance-based system for measuring, certi fying, and monitoring features of the built environment that impact human health and well-being, through air, water, nourishment, light, fitness, comfort, and mind. Of these, I chose to study Air, Light, Sound, Thermal Comfort, and Mind, with the addition of Aesthetics.

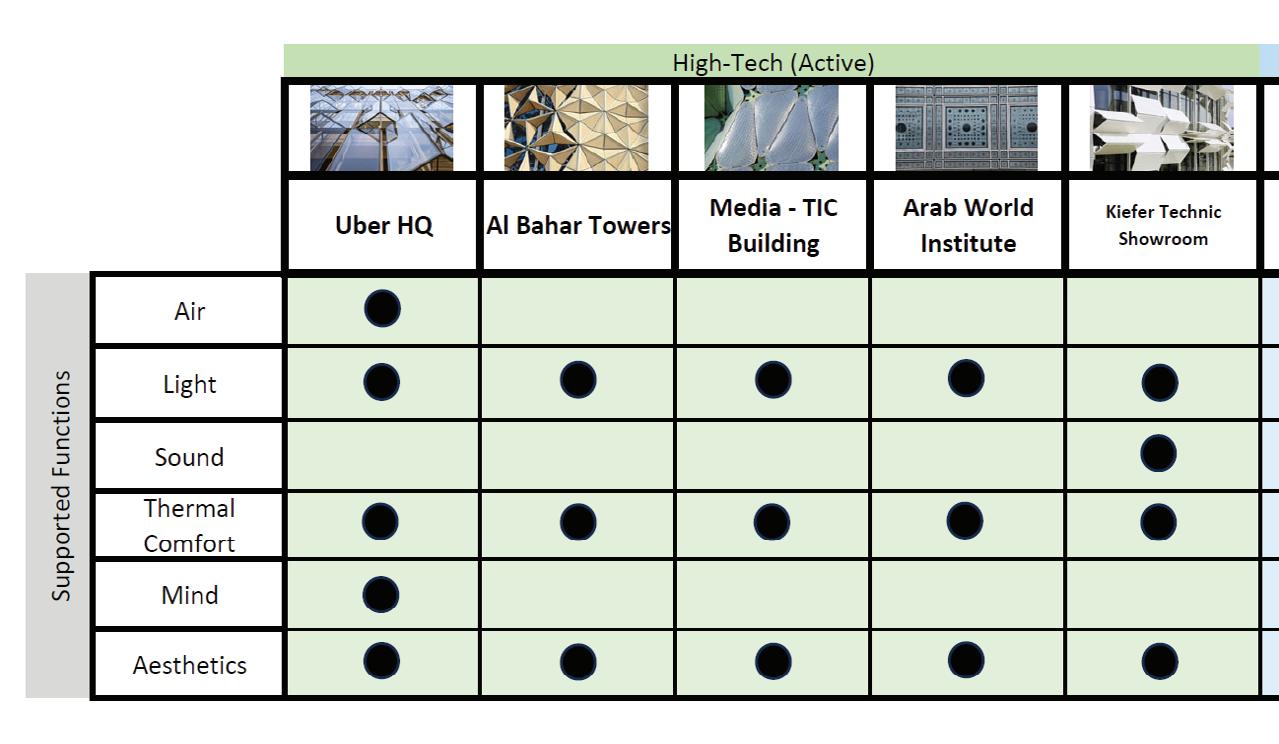

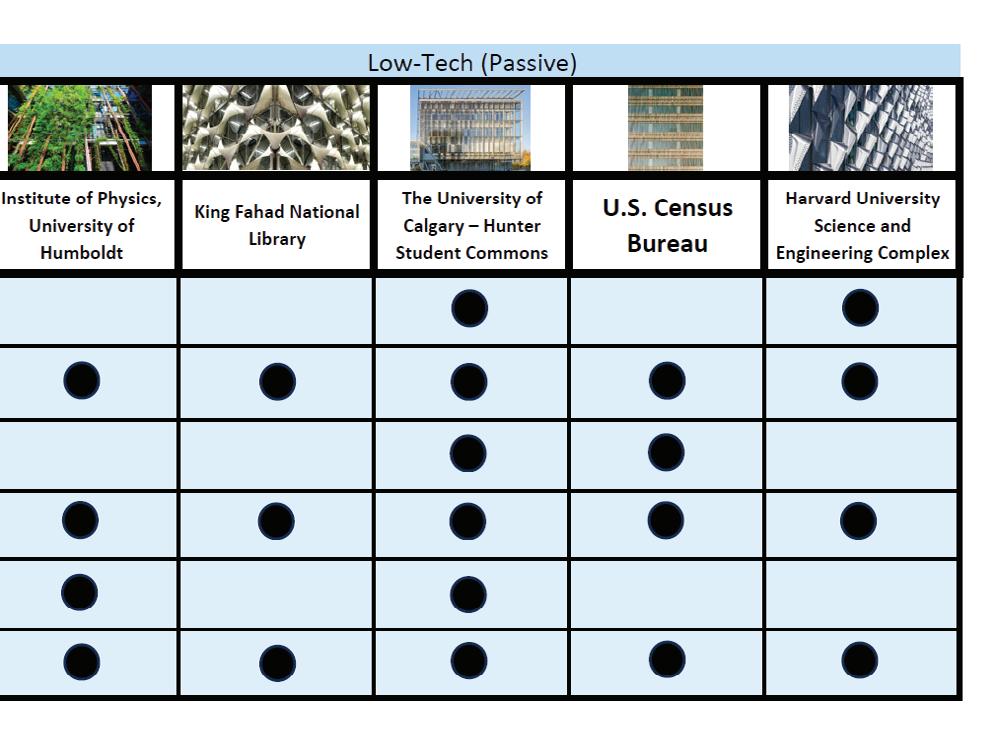

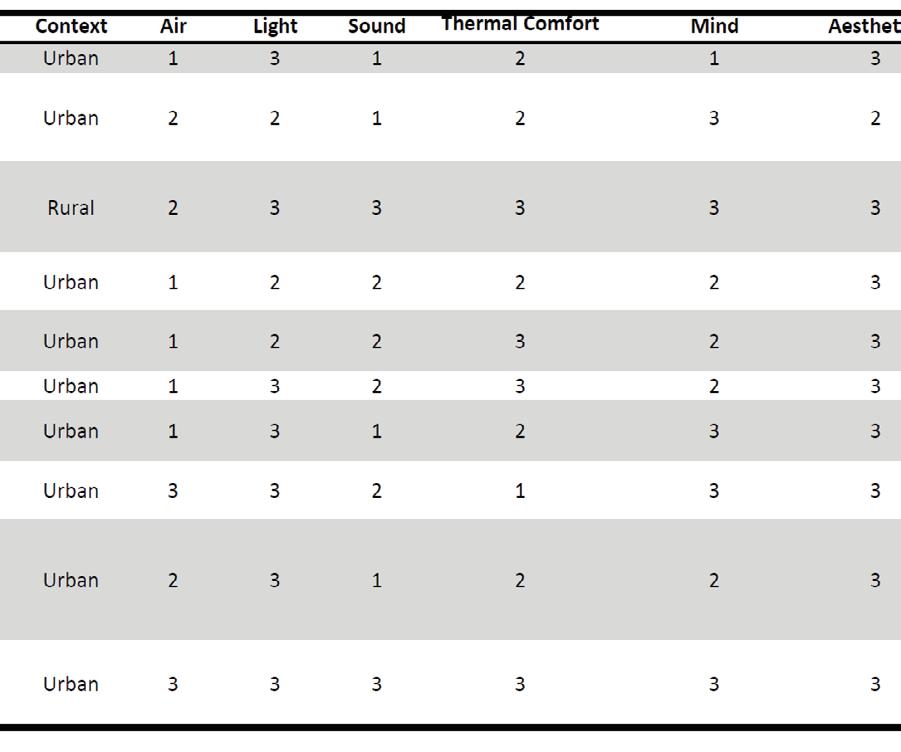

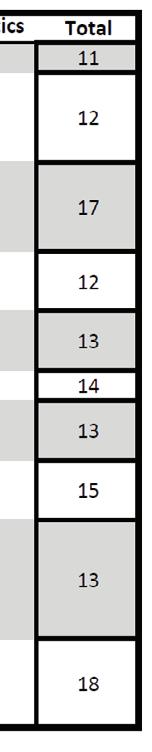

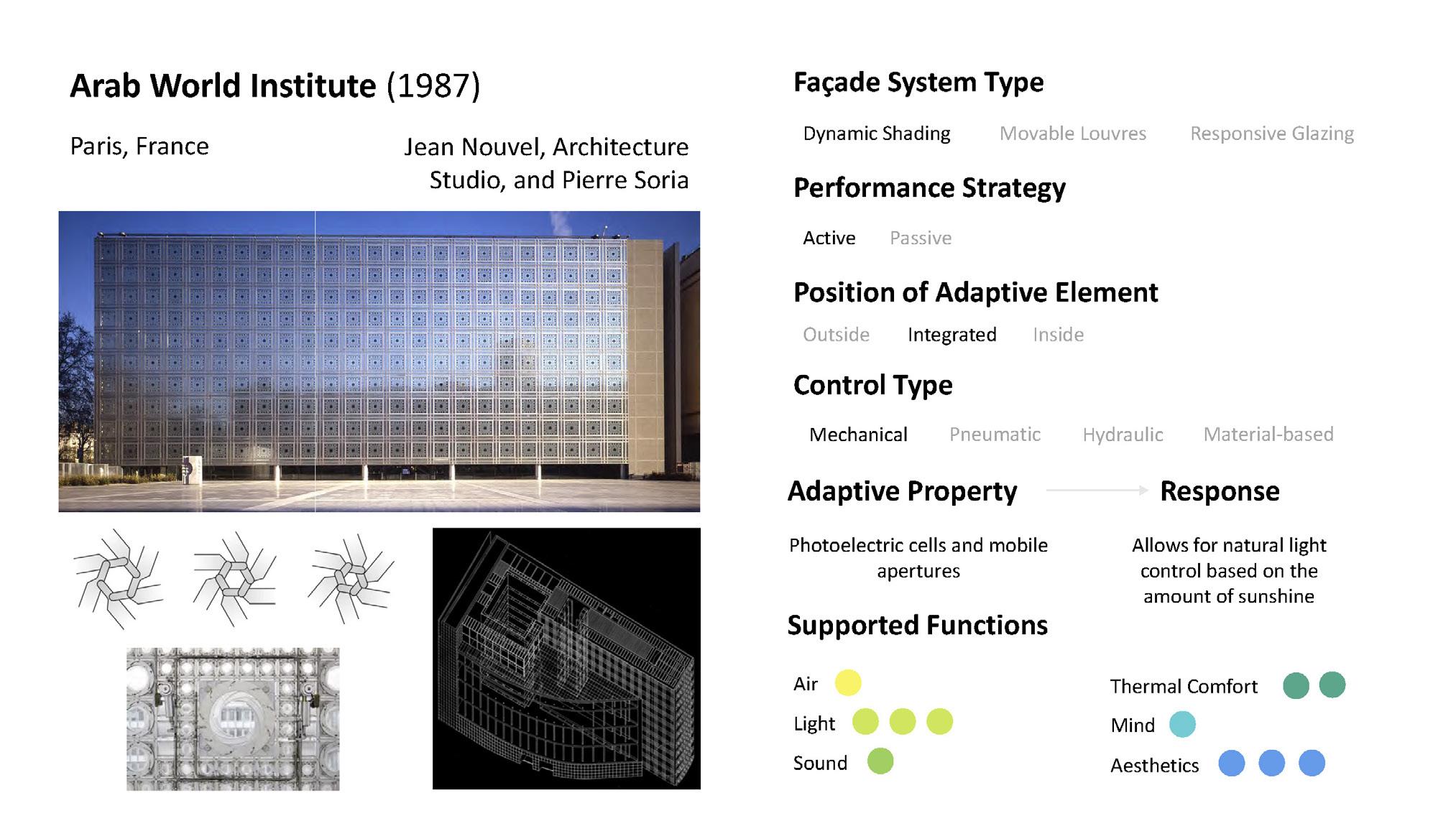

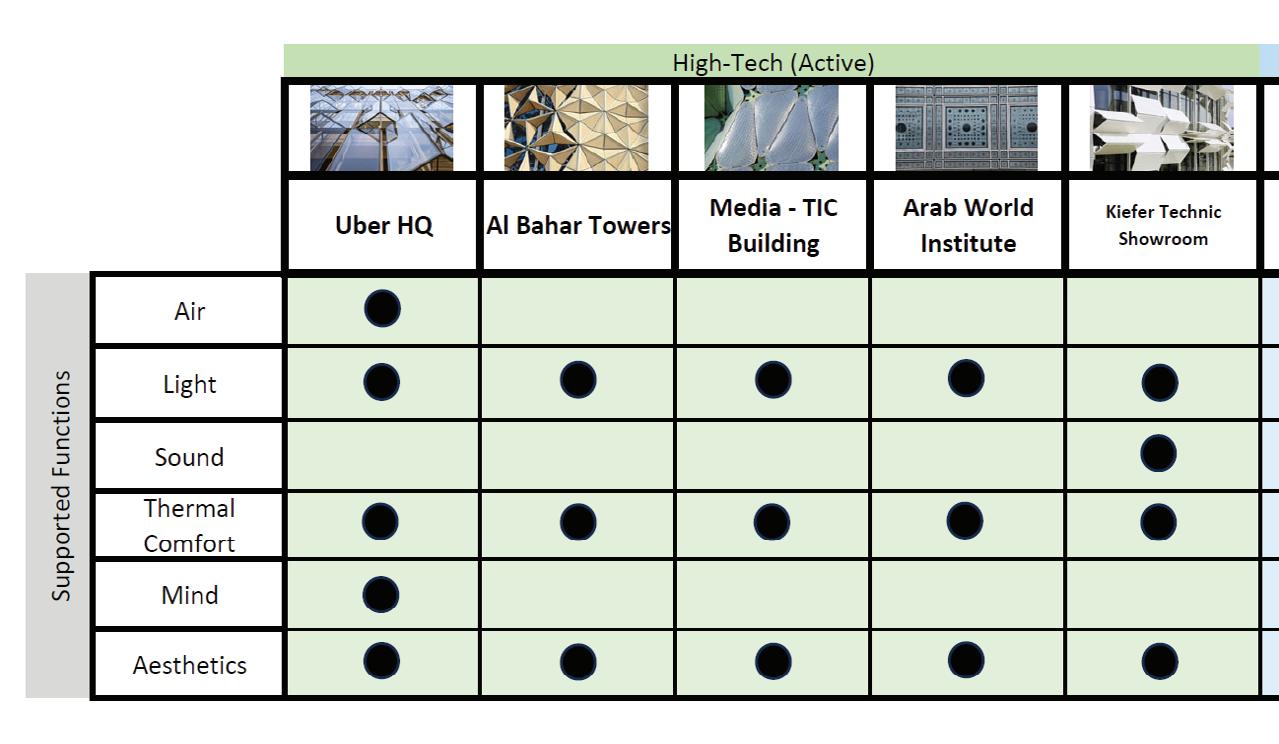

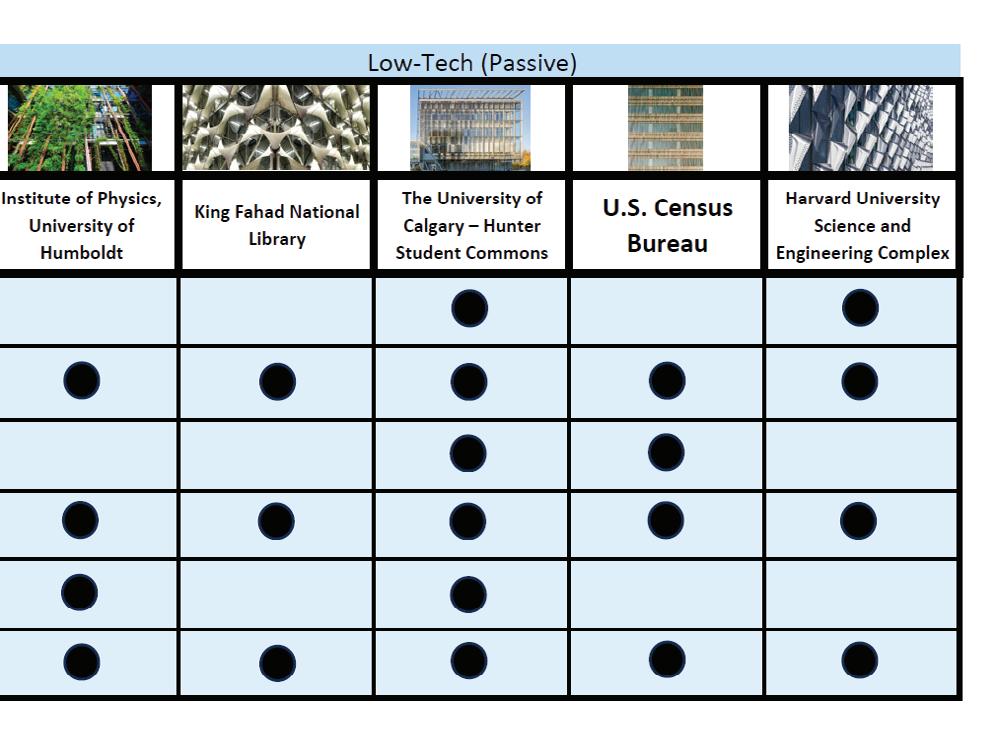

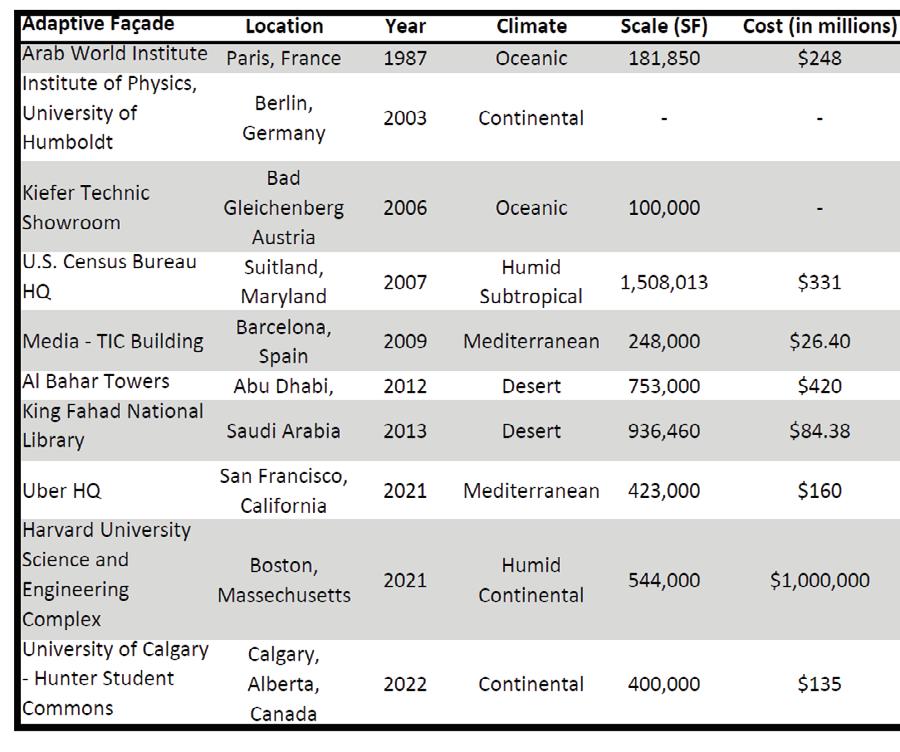

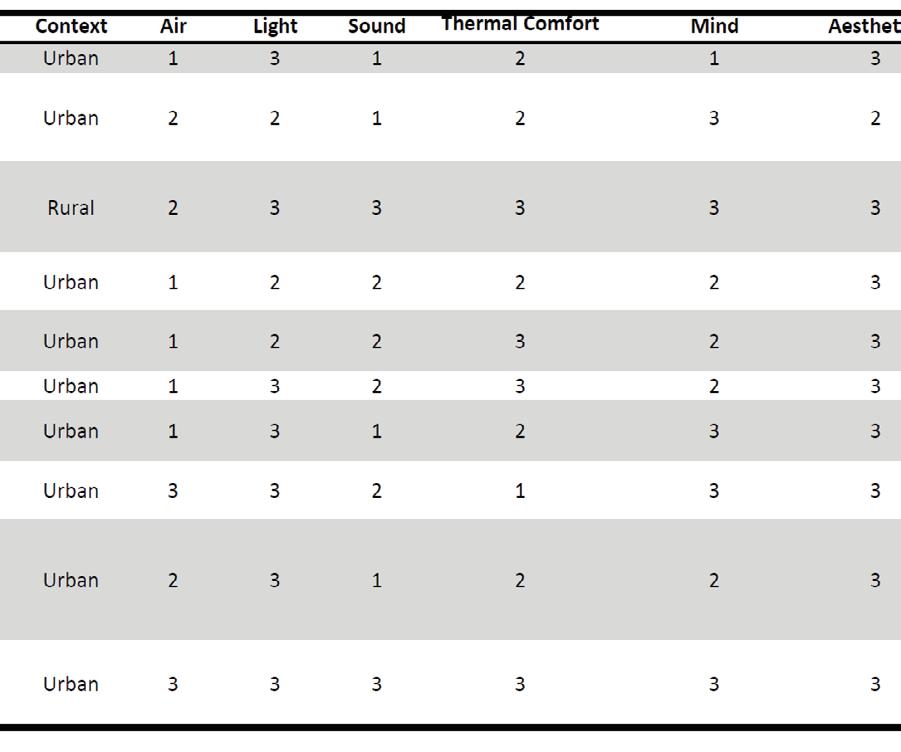

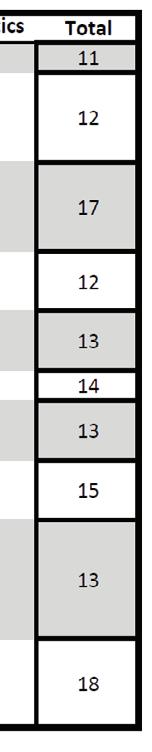

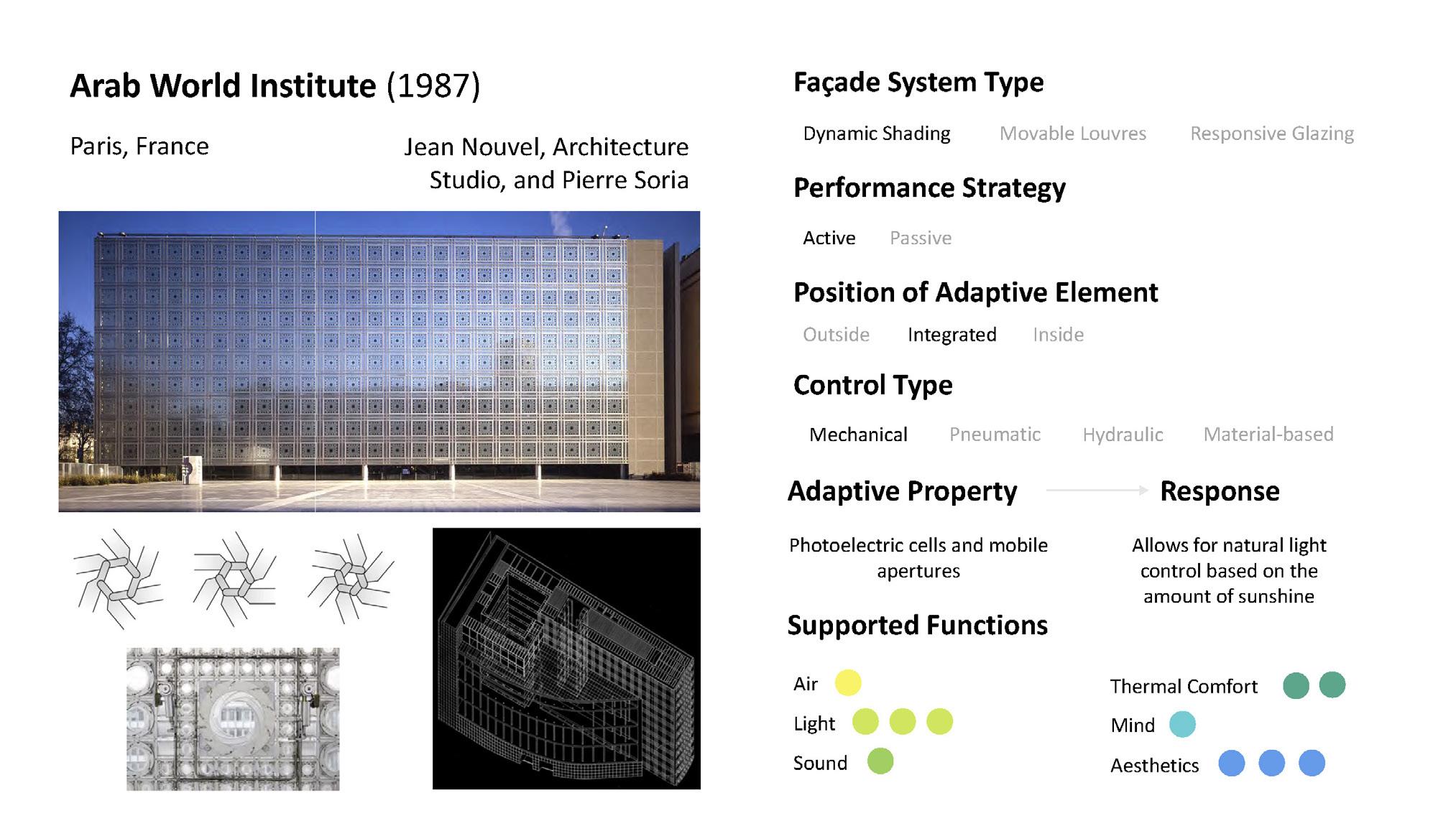

I felt the best way to explore the relationship between adaptive facades and these WELL standards was to study a set of buildings with adaptive facades. I closely studied 10 buildings in various locations and climates (Figure 2).

DATA AND SYNTHESIS

I placed the 10 projects into a matrix where they are divided into High-Tech and Low-Tech (Figure 3). High-tech meaning there is some sort of technology used to allow the façade to adapt, and low-tech meaning no technology is needed for the façade to adapt and little human intervention is required. I then used dots to mark whether or not each of the projects displayed the various qualities listed by WELL.

From this, I placed the buildings in a more specific table not only showing additional information on each building like location, year constructed, climate, scale, cost, and context, but I rated them on a scale of 1-3 on how well they each exemplify the WELL standards (Figure 4). 3 being excellent, 2 being moderate, and 1 being poor. Areas that received a rating of 3 signified the highest level of performance or quality. It indicated that the subject being evaluated has exceeded expectations, achieved outstanding results, or demonstrated exceptional qualities. Areas that received a rating of 2 suggest a level of performance or quality that is acceptable but may have room for improvement. It indicates that the subject being evaluated meets basic requirements or standards but may not excel in all areas. Areas that received a rating of 1 indicate a low level of performance or quality that does not meet expectations or standards. It suggests that the

15 Climate

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Figure 2. Map of 10 Studied Adaptive Facade Projects

Rating System:

3 = Excellent

2 = Moderate

1 = Poor

Excellent (3) – This rating signifies the highest level of performance or quality. It indicates that the subject being evaluated has exceeded expectations, achieved outstanding results, or demonstrated exceptional qualities.

Moderate (2) – This rating suggests a level of performance or quality that is acceptable but may have room for improvement. It indicates that the subject being evaluated meets basic requirements or standards but may not excel in all areas.

Poor (1) – This rating indicates a low level of performance or quality that does not meet expectations or standards. It suggests that the subject being evaluated falls significantly short of the desired criteria and may require significant improvement or corrective action.

16 Owens: Adaptive Facades

Figure 3. Facade Matrix

Figure 4. Facade Table with Rating System

subject being evaluated falls significantly short of the desired criteria and may require significant improvement or corrective action. Each of the ratings were tallied to a total for each of the buildings. The oldest example built in 1987 received the lowest total rating of 11 and the newest example built in 2022 received the highest rating of 18. I created building identification pages to get a better understanding of how each of the façade systems work and in which ways they support occupant comfort. From these pages I have observed.

CONCLUSIONS

After analyzing which aspects of the facades were most successful, I have created a proposed guideline to measure the qualities of a “successful” adaptive façade (Figure 6). I have broken the guideline into the 6 WELL qualities I have been using to analyze each of the projects and then further broke them down into passive and active strategies.

To fulfill air qualities, a façade should Optimize natural ventilation and consider air quality in design. One should install sensors to monitor and adjust for optimal indoor air conditions.

To fulfill lighting qualities, a façade should be designed for daylighting to reduce reliance on artificial lighting. One should utilize automation to control glare and adjust for changing daylight conditions.

To fulfill sound qualities, a façade should minimize noise transmission through its design. One should consider additional features to control sound within the building.

To fulfill thermal regulation qualities, a façade should optimize insulation, thermal mass, and building orientation. One should use responsive glazing and shading systems to regulate temperature.

To fulfill qualities related to mind, a façade should optimize its design for visual comfort, daylighting, and glare reduction. Ensure flexibility to meet diverse occupant needs and preferences. Promote indoor health with passive ventilation and air quality considerations. One should educate occupants on adaptive facade benefits and encourage engagement through interactive displays and digital interfaces. Enable personalization of indoor settings, fostering a sense of control and ownership.

Finally, to fulfill aesthetic qualities, the facade should contribute to the building’s aesthetic appeal. One should balance energy performance with visual aesthetics when implementing dynamic elements.

I have talked about the existing adaptive facades that are out there, but truth be told, it is very limited. There are reasons why adaptive facades are limited and sometimes frightening to people. The three major barriers to adaptive facades are additional costs, maintenance and operations, and unfamiliarity with either construction or operation in architecture, engineering, and construction.

When it comes to fabrication, construction, and integration of adaptive facades, they are a lot more challenging because they require more maintenance. Clients and building owners are also very reluctant to have any moving systems on the exterior of buildings. We typically rely on standard products and systems that have been around for the last 10-30 years and have been tested. In general, whenever you try to bring in an innovative system or material, research and development need to happen. It is considered to be risky to be innovative and makes people hesitant to be the first to implement a completely new system.

Typically, a stakeholder’s first question is what is the return on investment? What is the operation and maintenance of this and what is the long-term performance? Since adaptive facades are pretty new we don’t know what the long-term performance is in most cases because it has not been around long.

During my research, I noticed that academic buildings, healthcare facilities, public buildings, and federal buildings are much more inclined to take risks and incorporate adaptive facades because they assume them to be well-used and around for a long time. They know that they will get their return on investment at some point. I think a crucial part of this all is to educate people who are hesitant about adaptive facades. Studying existing buildings like I have is also very beneficial when determining the success of certain adaptive features. The end result of these adaptive facades is something really beautiful and I think at some point will become an integrated part of the design and construction process because they have proven to be beneficial in many ways.

17 Climate

The Arab World Institute, located in Paris, France, features photoelectric cells and mobile apertures that allows for natural light control based on the amount of sunshine. Naturally, this façade excels in the category of light among others.

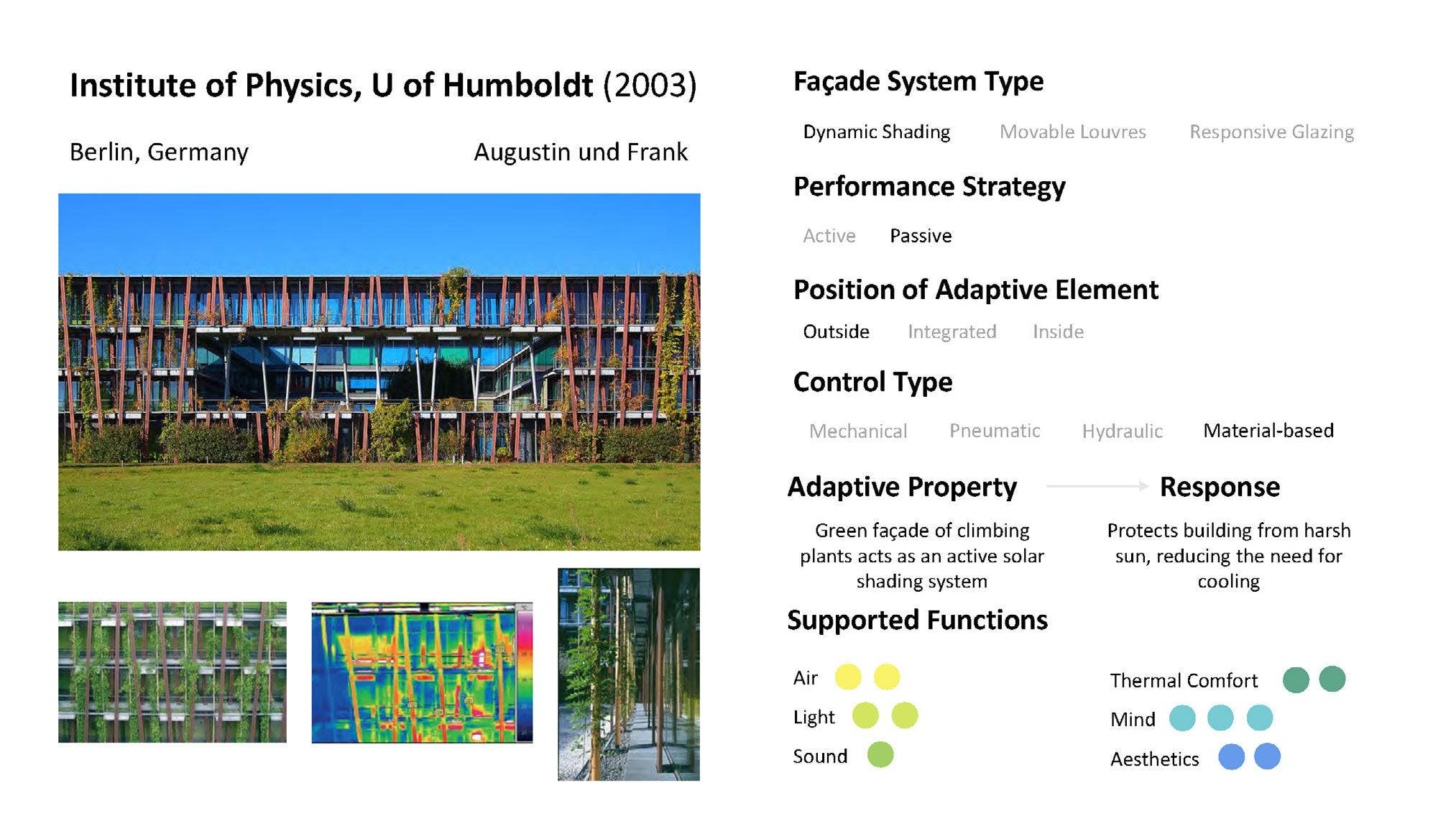

The University of Humboldt’s Institute of Physics, located in Berlin, Germany features a green façade of climbing plants that act as a shading system. In the warmer months, when the plants are in bloom, the need for cooling is reduced. In the winter, when the plants are not in bloom, the natural sunlight is used to heat the building, reducing the need for heating systems. This façade excels in the category of mind among others.

18 Owens: Adaptive Facades

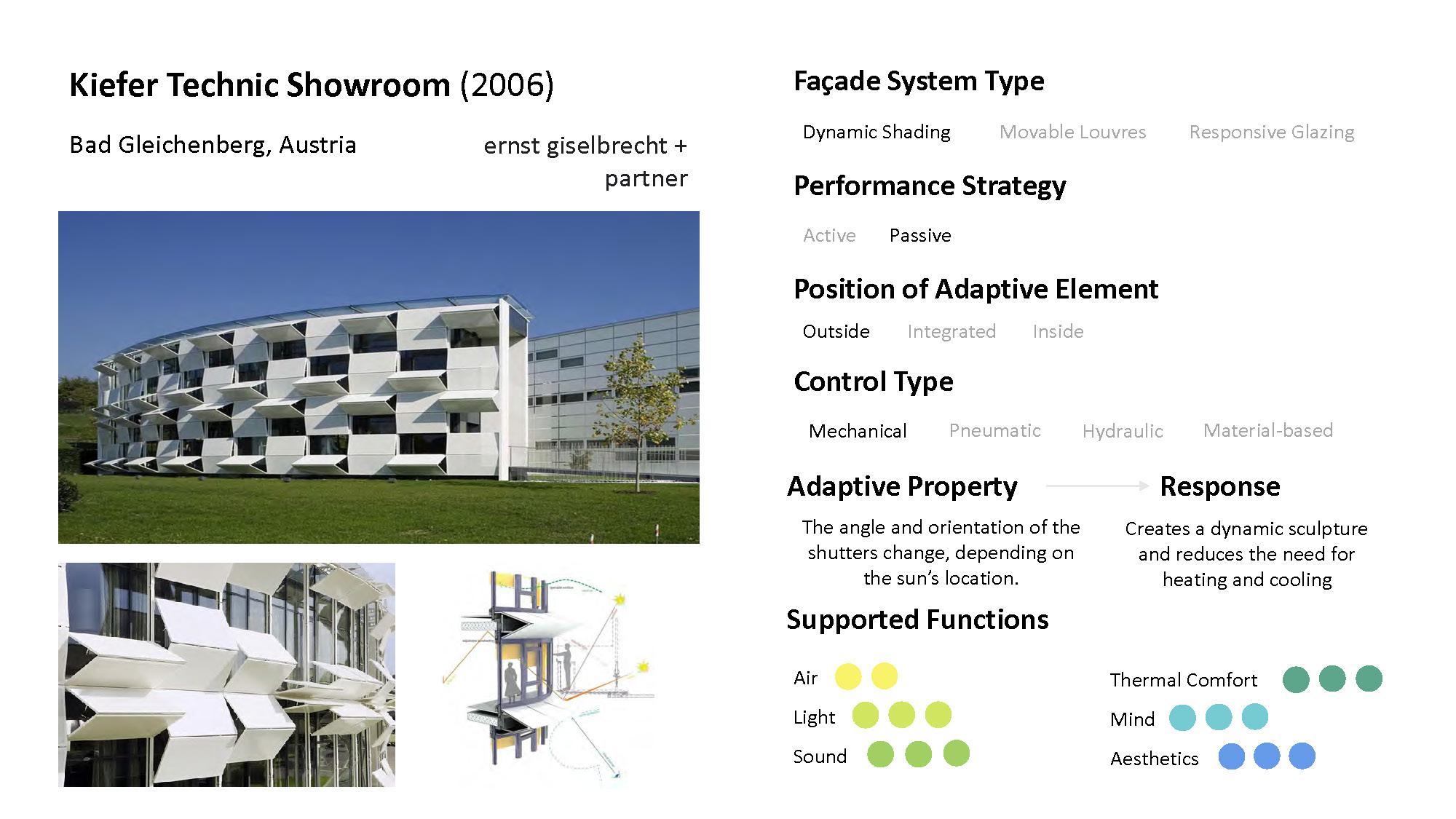

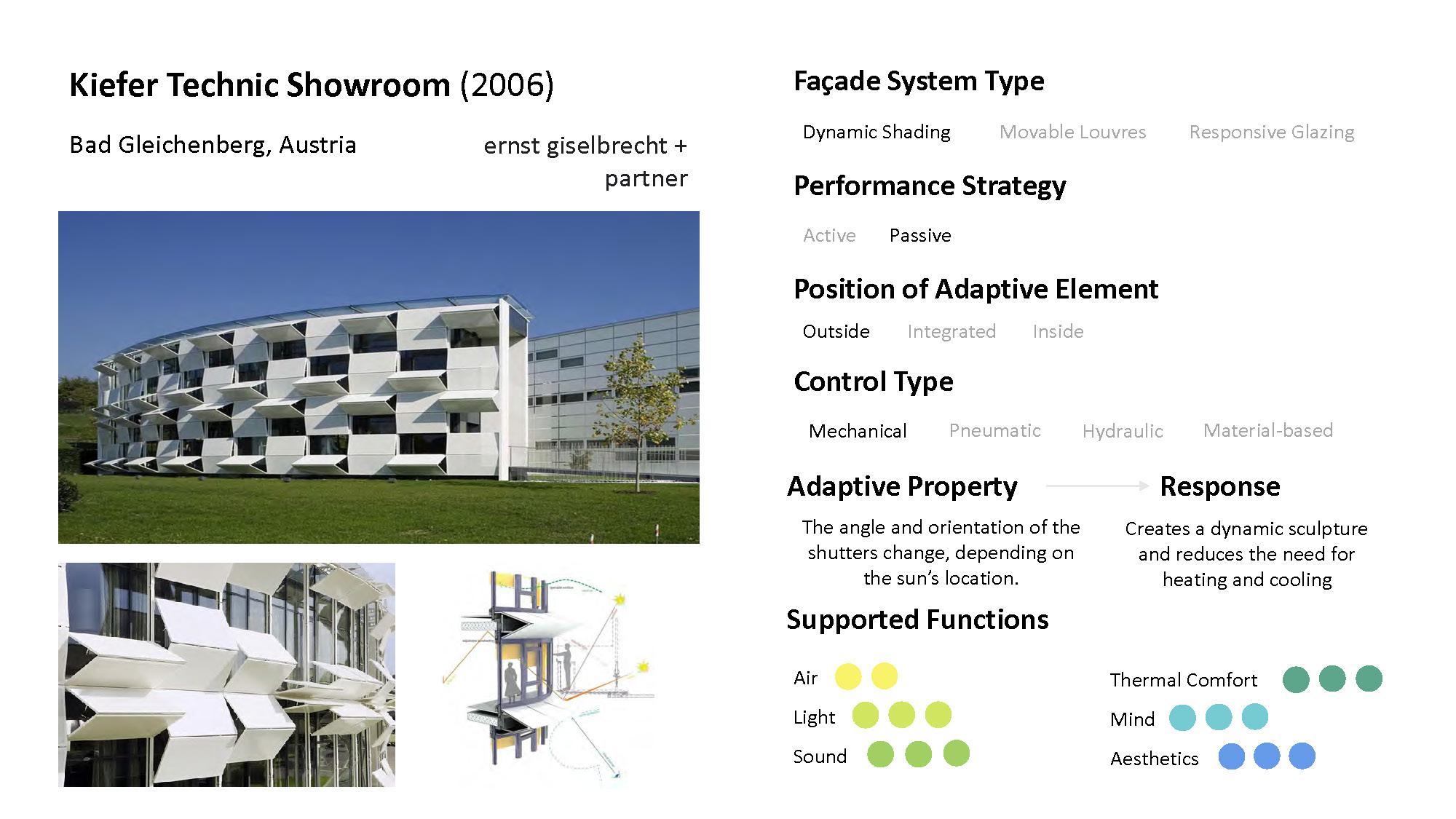

The Kiefer Technic Showroom, located in Bad Gleichenberg, Austria features mechanic shutters whose angles and orientations change depending on the sun’s location. The shutters create a dynamic sculpture and reduce the need for heating and cooling systems. This façade excels in all areas besides the air category.

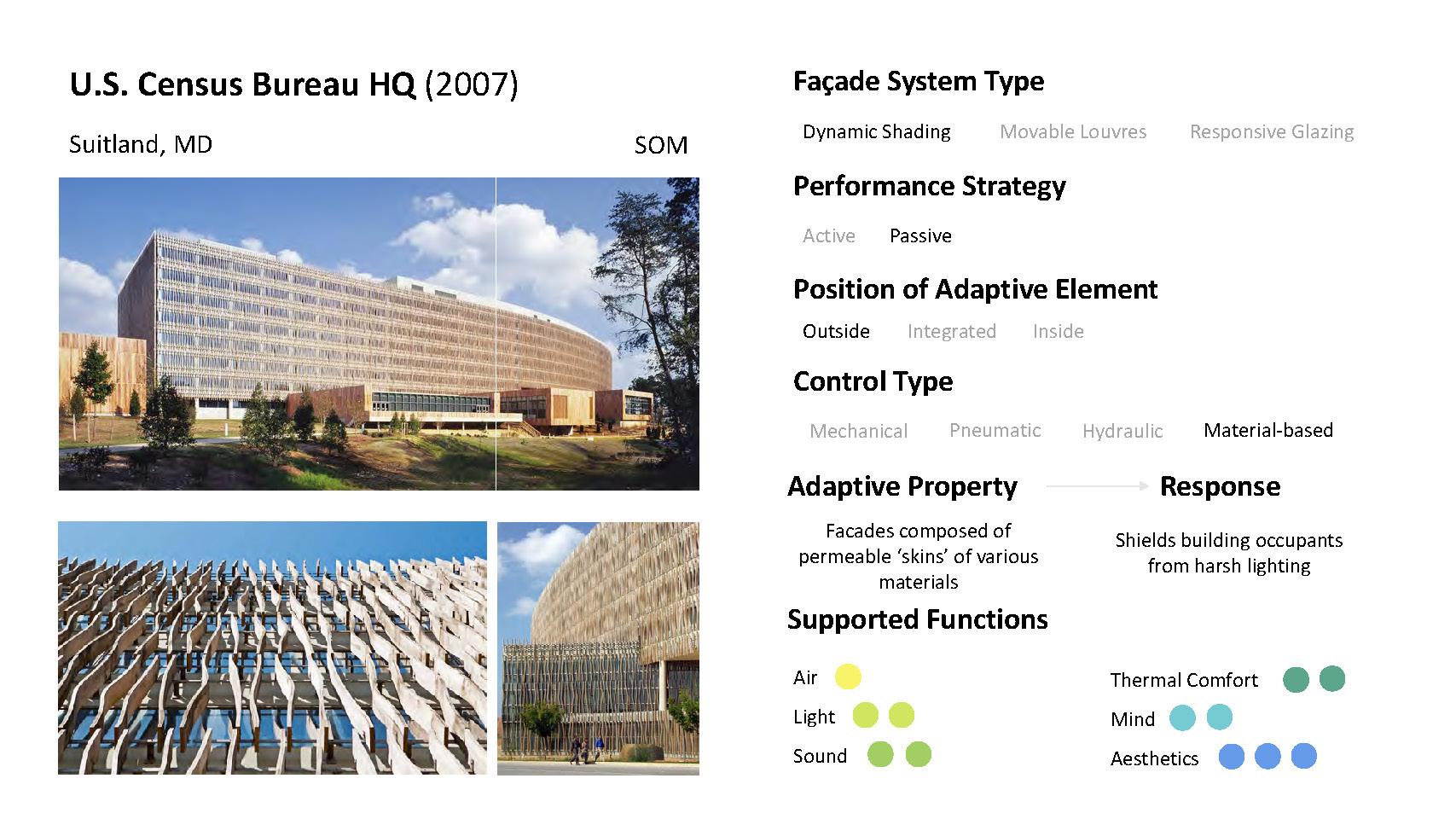

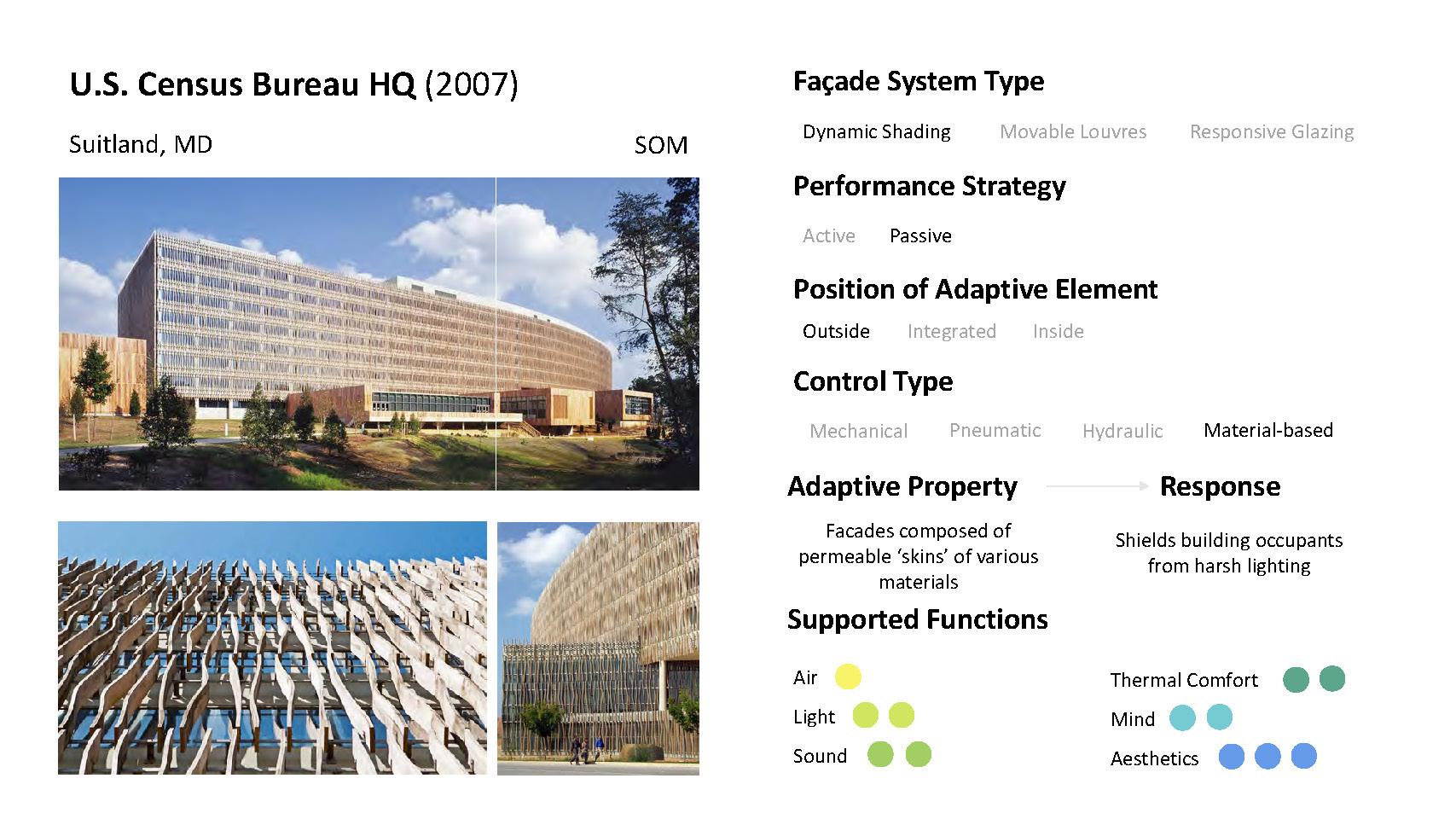

The U.S. Census Bureau HQ , located in Suitland, Maryland, features facades composed of permeable skins of various materials which shield building occupants from harsh lighting. This façade is moderate in all categories besides air.

19 Climate

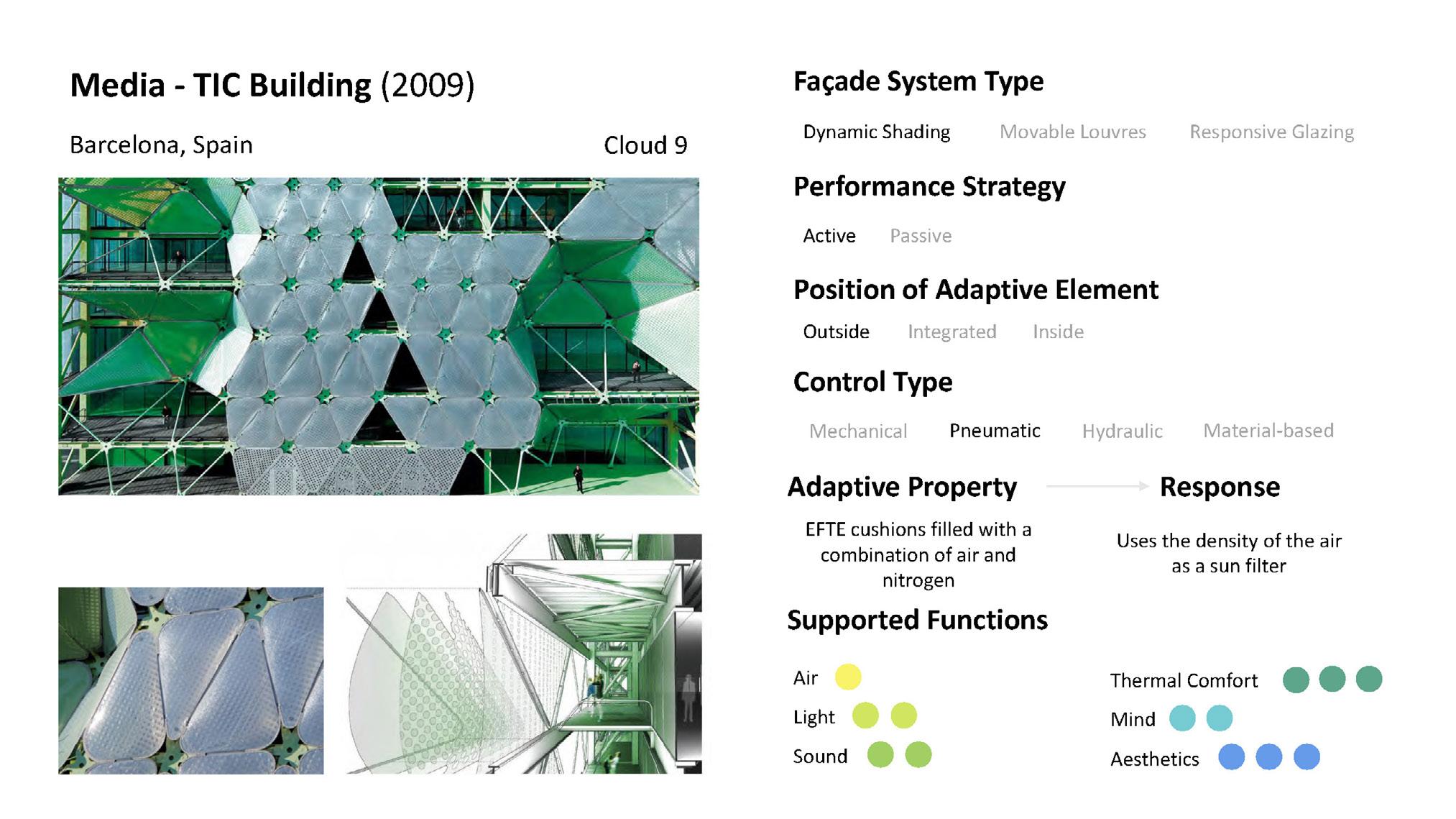

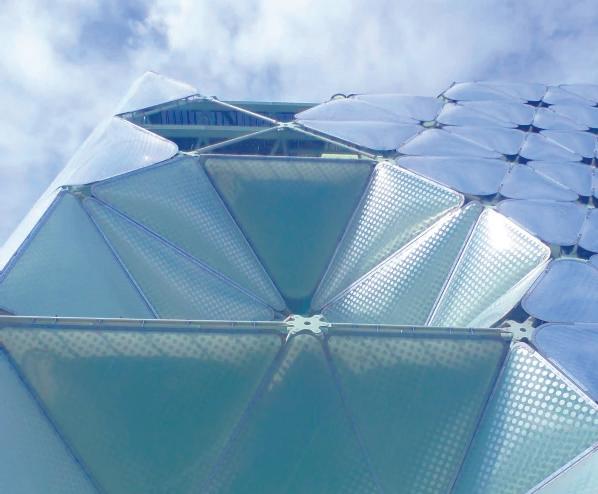

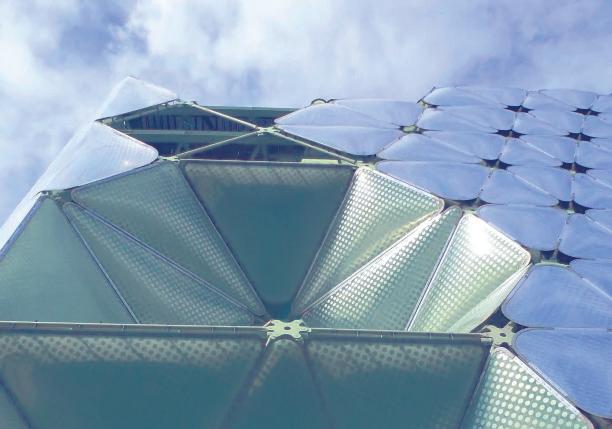

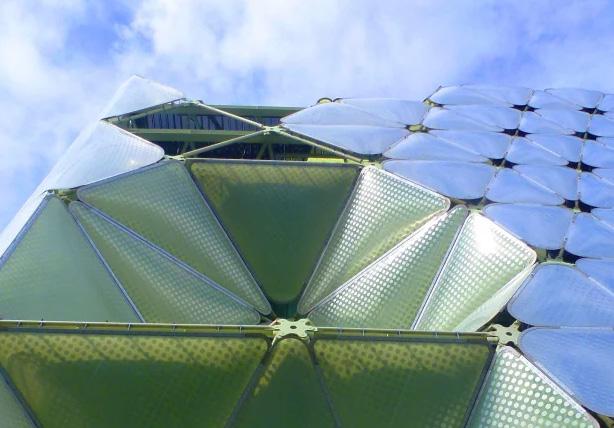

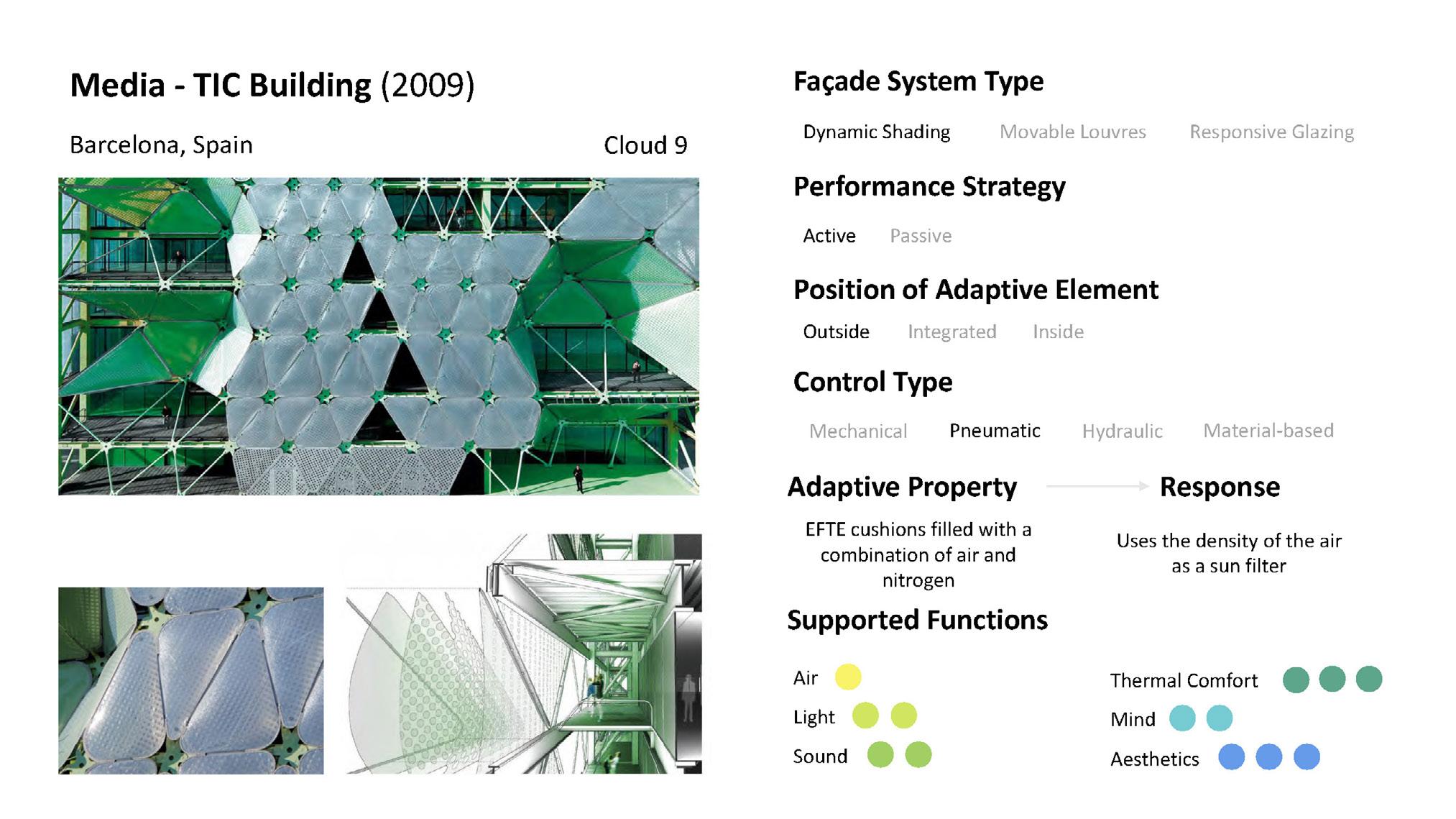

The Media – TIC Building, located in Barcelona, Spain features EFTE cushions filled with a combination of air and nitrogen which use the density to act as a sun filter. This façade excels in the category of thermal comfort.

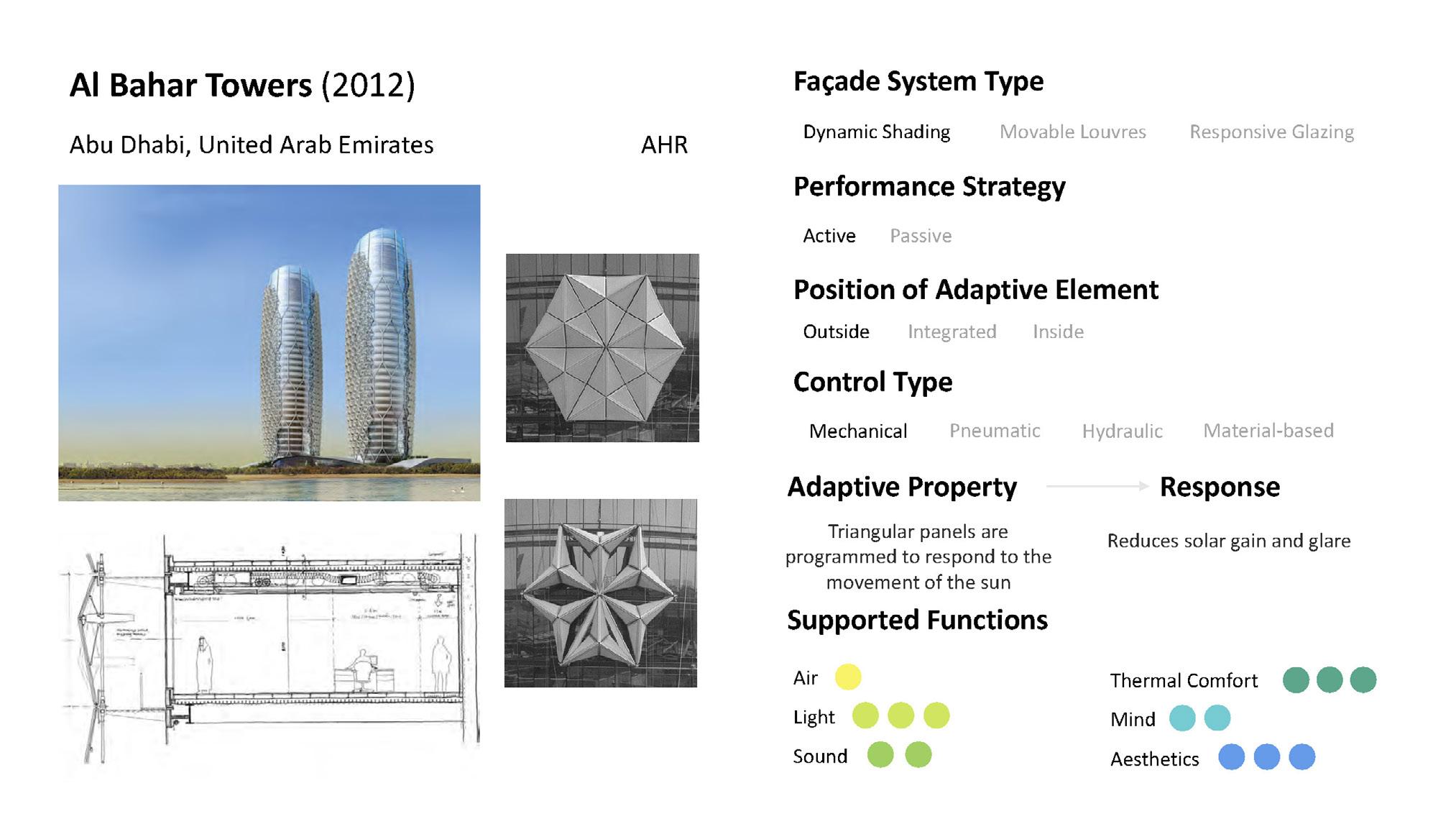

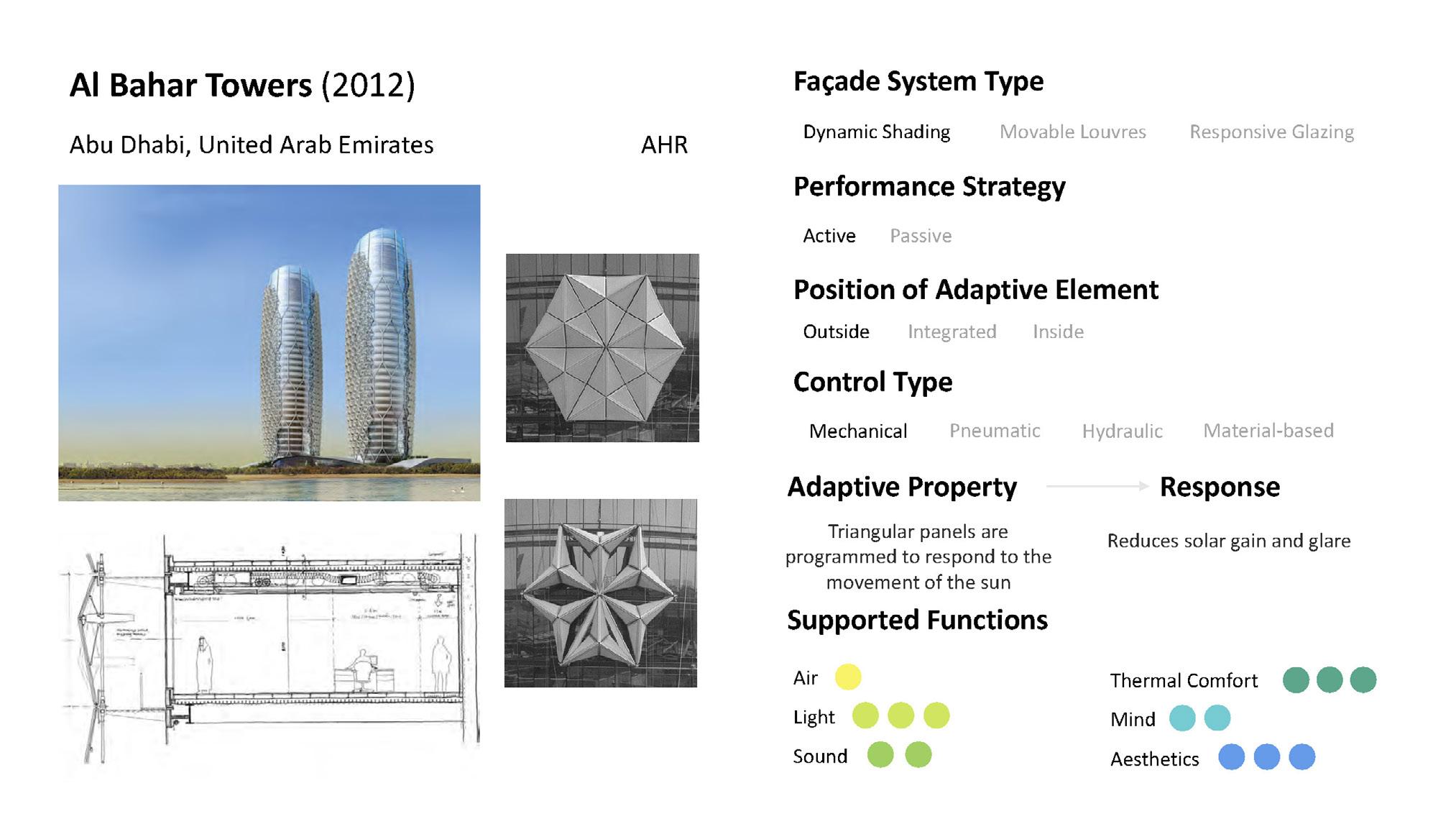

The Al Bahar Towers, located in Abu Dhabi, features triangular panels that are programmed to respond to the movement of the sun. This reduces solar gain and glare in the hot desert climate. This façade excels in thermal comfort and lighting among other categories.

20 Owens: Adaptive Facades

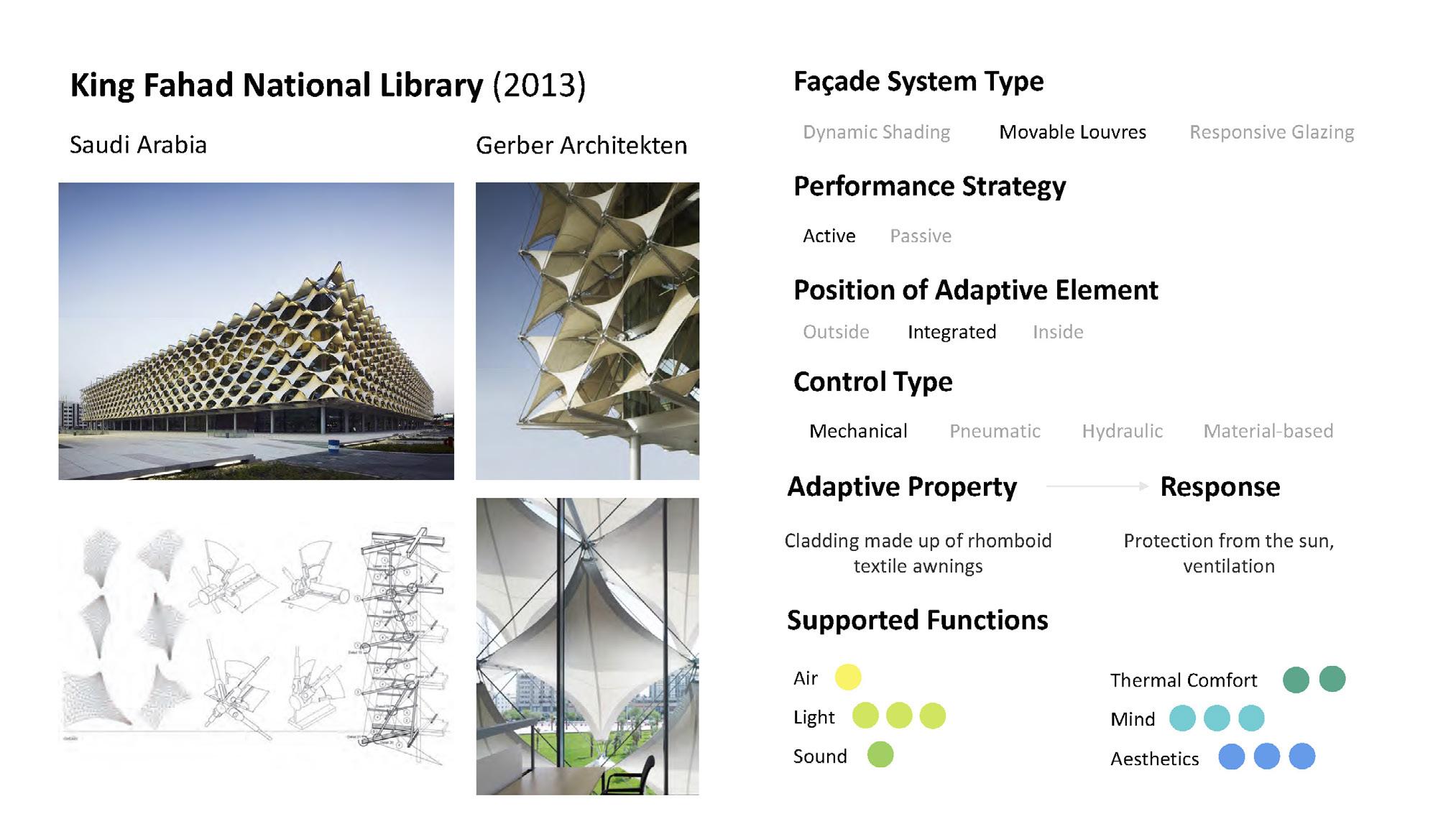

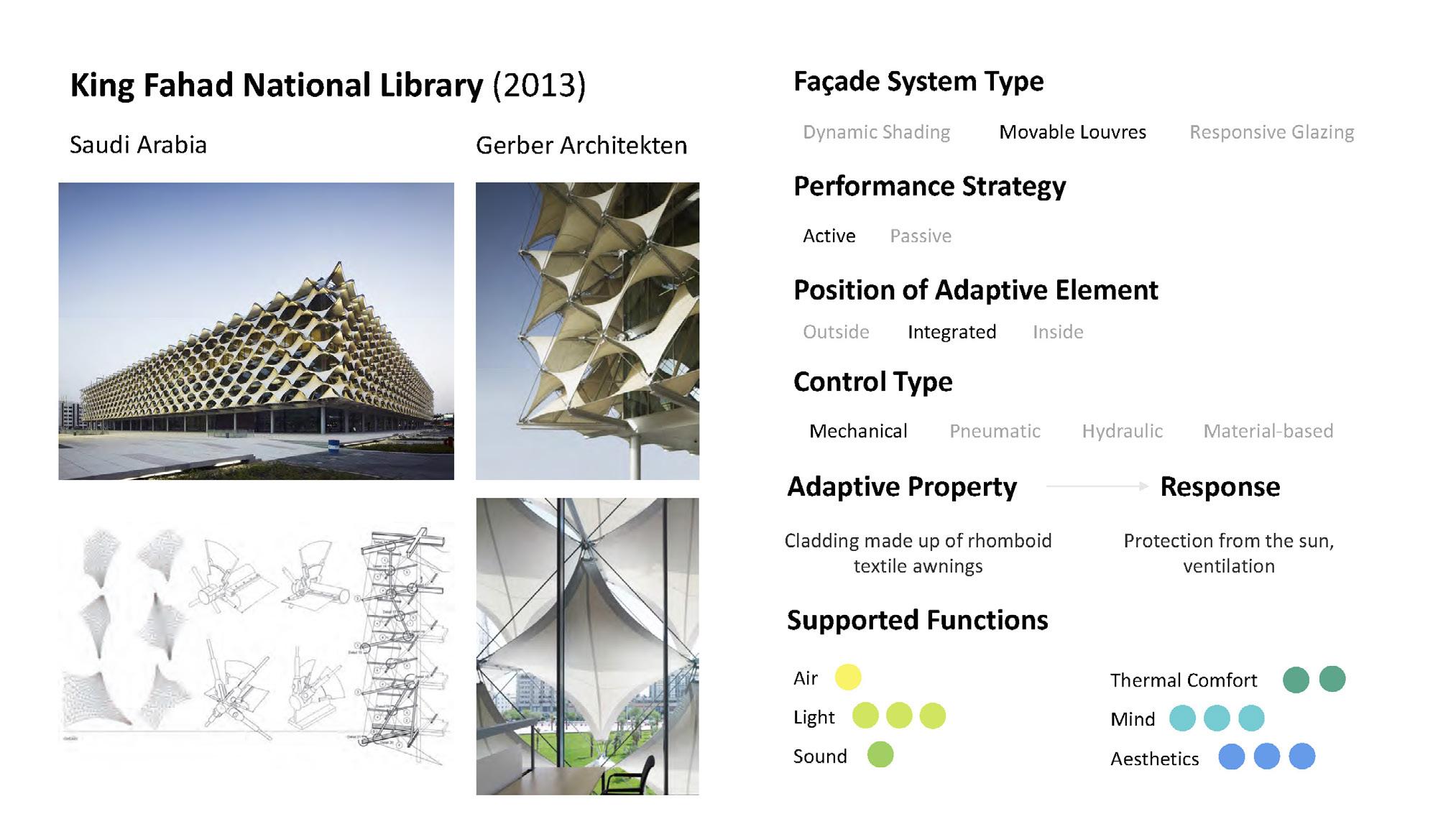

The King Fahad National Library, located in Saudi Arabia features a cladding system made of rhomboid textile awnings that offers protection from the sun. This façade excels in light and mind among other categories.

The King Fahad National Library, located in Saudi Arabia features a cladding system made of rhomboid textile awnings that offers protection from the sun. This façade excels in light and mind among other categories.

21 Climate

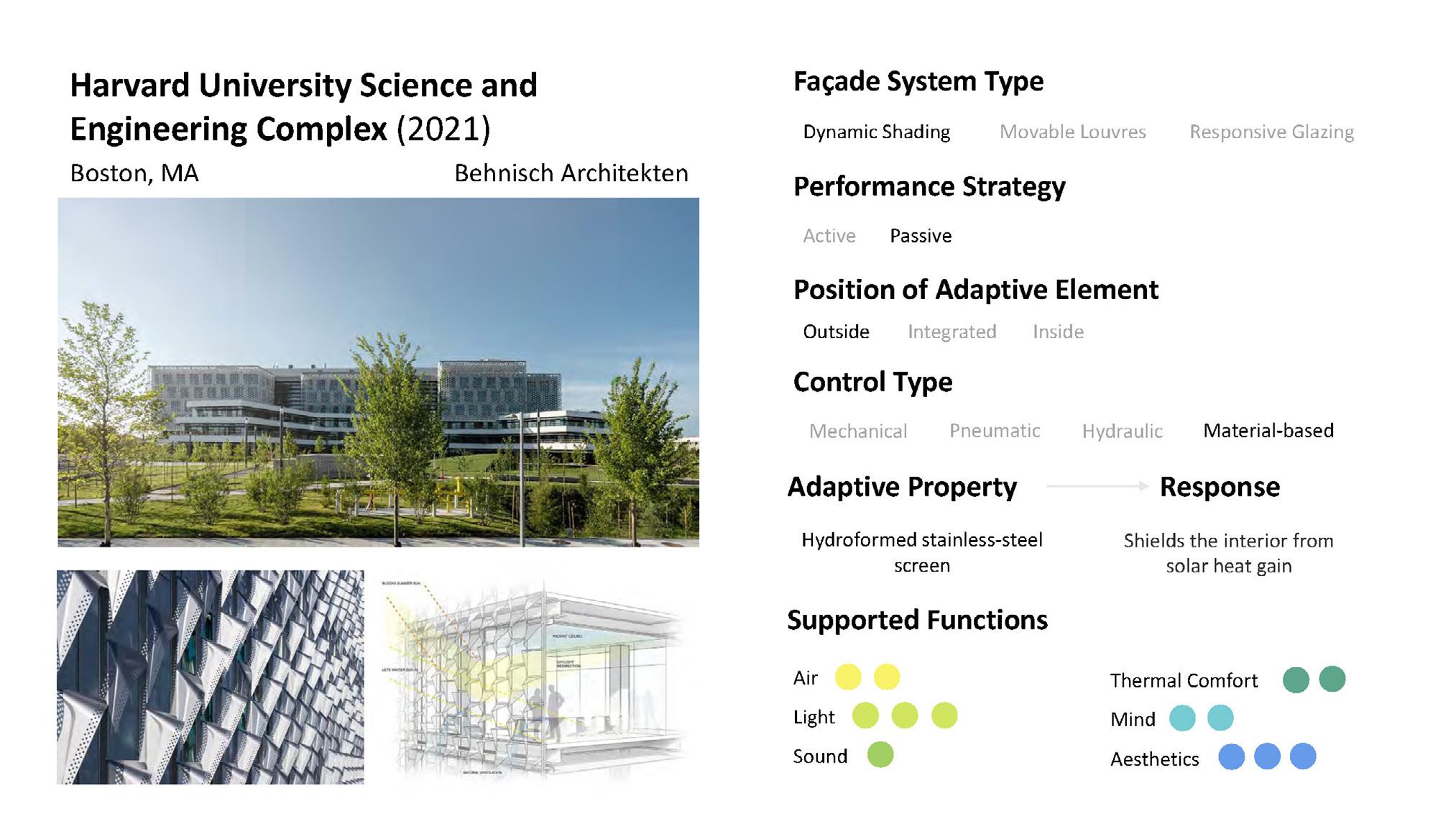

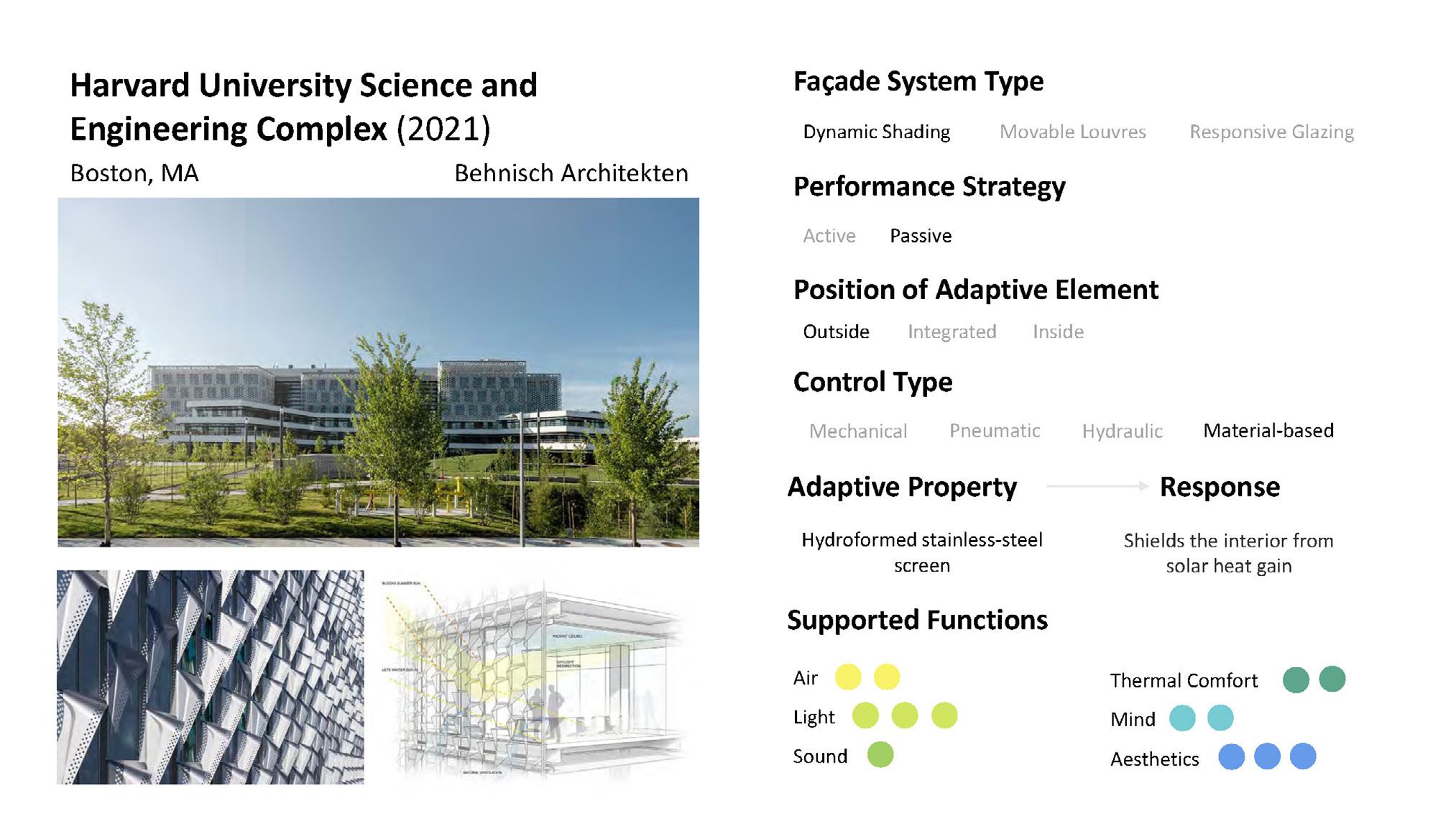

The Harvard University Science and Engineering Complex, located in Boston features hydroformed stainless steel screens that shield the interior from solar heat gain. This façade excels in the category of light among others.

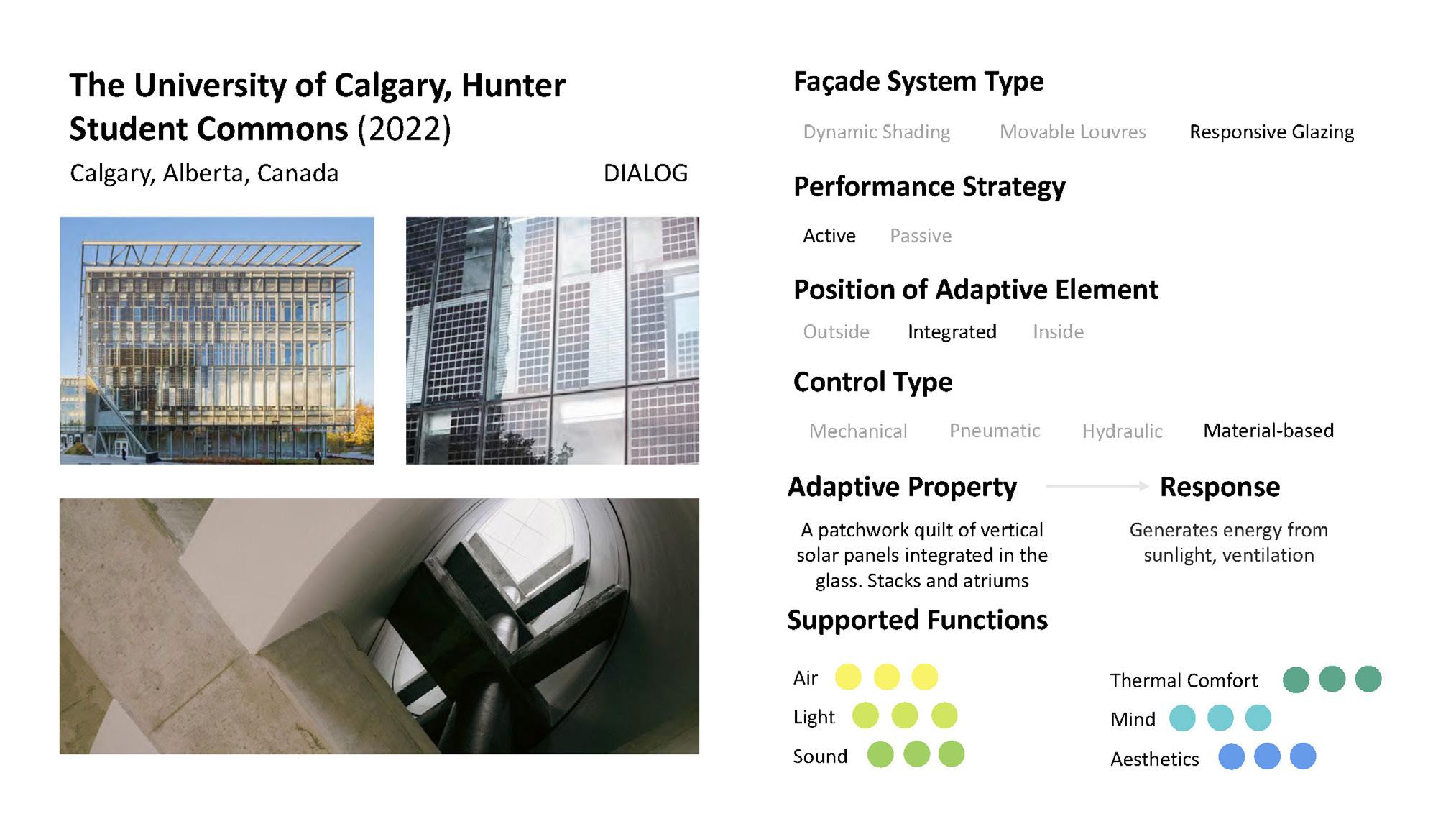

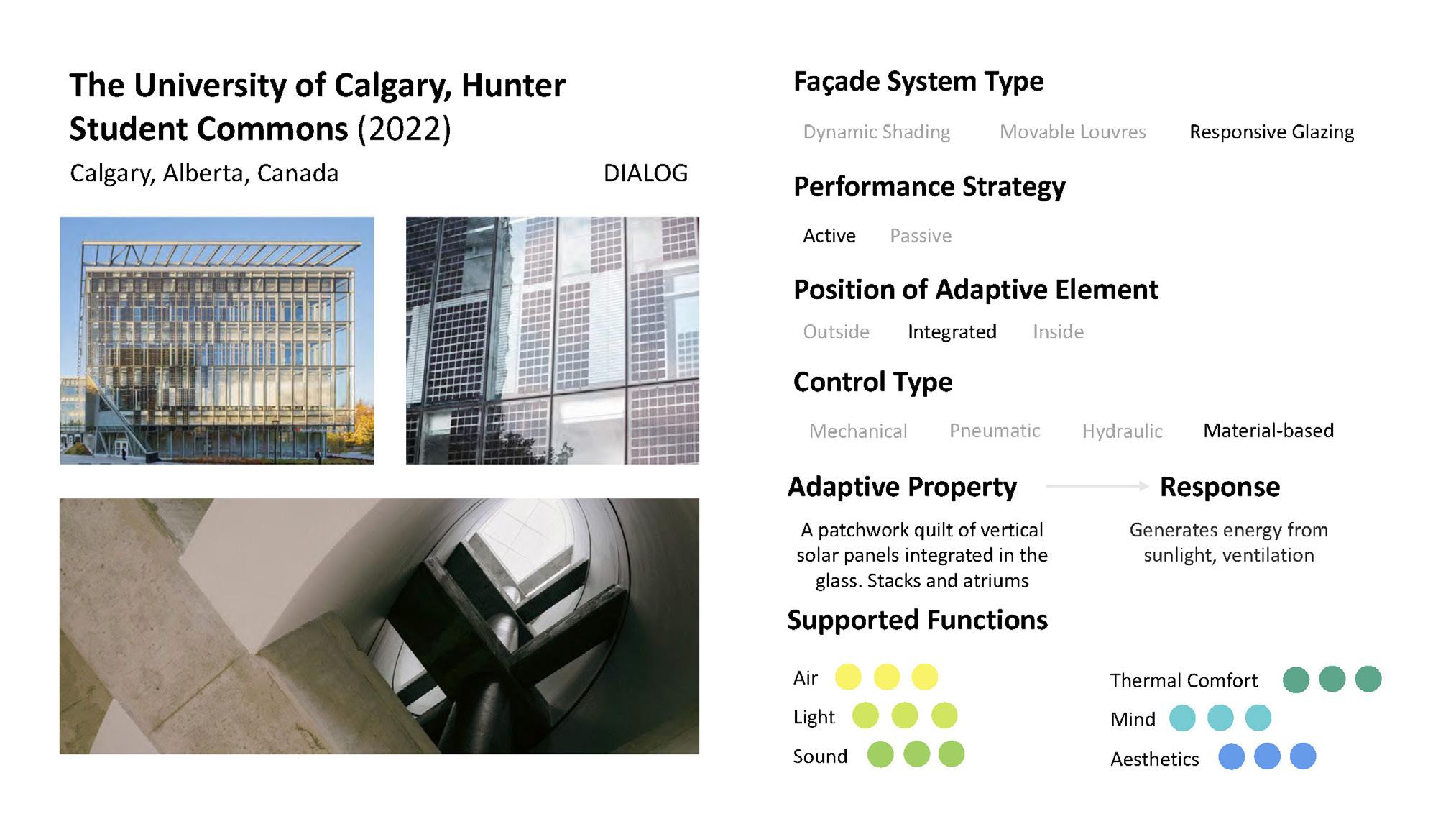

The University of Calgary’s Hunter Student Commons, located in Alberta, Canada, features a patchwork quilt of vertical solar panels integrated in the glass. This building also offers stacks and atriums for increased ventilation. This façade excels in all categories.

22 Owens: Adaptive Facades

Guideline for a “Successful” Adaptive Façade

Passive Strategies: Optimize natural ventilation and consider air quality in design.

Active Control Systems: Install sensors to monitor and adjust for optimal indoor air conditions.

Thermal Comfort

Passive Strategies: Optimize insulation, thermal mass, and building orientation.

Active Control Systems: Use responsive glazing and shading systems to regulate temperature.

Passive Strategies: Design for daylighting to reduce reliance on artificial lighting.

Active Control Systems: Utilize automation to control glare and adjust for changing daylight conditions.

Passive Strategies: Minimize noise transmission through facade design.

Active Control Systems: Consider additional features to control sound within the building.

Aesthetics Mind

Passive Strategies: Optimize facade design for visual comfort, daylighting, and glare reduction. Ensure flexibility to meet diverse occupant needs and preferences. Promote indoor health with passive ventilation and air quality considerations.

Active Control Systems: Educate occupants on adaptive facade benefits and encourage engagement through interactive displays and digital interfaces. Enable personalization of indoor settings, fostering a sense of control and ownership.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by professors, professionals, and peers throughout the completion of my capstone project. I would like to thank those who were involved in the development of the Architectural Studies Program and the endless support I have received while being a part of it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aksamija, Ajla. Sustainable Facades: Design Methods for High-Performance Building Envelopes. 1. Aufl. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2013.

Alkhatib, H., et al. “Deployment and control of adaptive building facades for energy generation, thermal insulation, ventilation and daylighting: A Review.” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 185, 2021, p. 116331, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.116331.

“Architecture.” Institut du monde arabe, October 13, 2016. https:// www.imarabe.org/en/architecture.

Arquitectura Viva. “Media-TIC Building - Cloud 9 .” Arquitectura Viva, May 11, 2022. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/ media-tic-building.

Böke, Jens, Paul-Rouven Denz, Natchai Suwannapruk, and Puttakhun Vongsingha. “Active, Passive and Cyber-Physical Adaptive Façade Strategies: A Comparative Analysis Through Case Studies.” Journal of Facade Design and Engineering. Accessed February 10, 2024. https://jfde.eu/index.php/jfde/article/view/239.

Borschewski, David, Michael P. Voigt, Stefan Albrecht, Daniel Roth, Matthias Kreimeyer, and Philip Leistner. 2023. “Why Are Adaptive Facades Not Widely Used in Practice? Identifying Ecological and Economical Benefits with Life Cycle Assessment.” Building and Environment 232 (March): 110069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2023.110069.

CBE Facade Map, March 10, 2023. https://facademap.cbe. berkeley.edu/.

Passive Strategies: Ensure the facade contributes to the building's aesthetic appeal.

Active Control Systems: Balance energy performance with visual aesthetics when implementing dynamic elements.

Cilento, Karen. “Al Bahar Towers Responsive Facade / Aedas.” ArchDaily, September 5, 2012. https://www.archdaily.com/270592/ al-bahar-towers-responsive-facade-aedas. CBE Facade Map, March 10, 2023. https://facademap.cbe.berkeley.edu/.

Cilento, Karen. “Al Bahar Towers Responsive Facade / Aedas.” ArchDaily, September 5, 2012. https://www.archdaily.com/270592/ al-bahar-towers-responsive-facade-aedas.

Gilse. “The Lise-Meitner-Haus (Department of Physics).” Institut für Physik, April 21, 2021. https://www.physik.hu-berlin.de/en/ department/about/the-lise-meitner-haus-department-of-physics.

Harvard University Science and Engineering Complex | Architect ... Accessed February 11, 2024. https:// www.architectmagazine.com/project-gallery/ harvard-university-science-and-engineering-complex_o.

“King Fahad National Library / Gerber Architekten.” ArchDaily, January 22, 2014. https://www.archdaily.com/469088/ king-fahad-national-library-gerber-architekten.

Pintos, Paula. “Uber Headquarters / Shop Architects.” ArchDaily, September 4, 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1006339/ uber-headquarters-shop-architects.

Sadineni, Suresh B., Srikanth Madala, and Robert F. Boehm. “Passive Building Energy Savings: A Review of Building Envelope Components.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15, no. 8 (October 2011): 3617–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rser.2011.07.014.

Vinnitskaya, Irina. “Kiefer Technic Showroom / Ernst Giselbrecht + Partner.” ArchDaily, November 17, 2010. https://www.archdaily. com/89270/kiefer-technic-showroom-ernst-giselbrecht-partner.

Well. “Standard: Well V2.” WELL Standard. Accessed February 10, 2024. https://v2.wellcertified.com/en/wellv2/overview.

23 Climate

Air Sound Light

24 Owens: Adaptive Facades

BIO

Kelly is a fifth-year senior anticipated to graduate in June of 2024. She is a dual major in architectural studies and real estate management and development. As a student, she developed an interest in sustainable design practice. Having the privilege of participating in both design and business courses provided her with a broader lens into sustainable topics. In her fourth year, she completed her Co-op experience with the University of Pennsylvania’s Planning, Design, and Construction group for the School of Engineering. Working as a junior interior designer, she strengthened her skills as a designer and as an advocate for green building practice. During her year with PDC, she was a member of the Penn Engineering Green Team, a cross-disciplinary team of staff and students representing each department across Engineering, who work to raise awareness about sustainability and change behavior within the Penn community.

Her senior architectural studies capstone project reflects her ongoing interest in sustainability. Her capstone focuses on adaptive facades and their ability to reduce building energy consumption while creating healthy and comfortable experiences for occupants. She anticipates the end of her undergraduate career with the embarkment on an exciting journey further exploring her interests and skills.

25 Climate

26 Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

Regenerative Architecture

ALEX PUERTO Bachelor of Science in Architectural Studies

27 Climate

PART I: Rethinking Place and Material Use in the Regenerative Architecture Paradigm

ALEX PUERTO

Keywords: regenerative architecture, sustainability, life-cycle assessment, biomaterials, materiality, place specificity

In the face of an escalating climate crisis, the view of sustainability in architecture has started to shift from a reduction-based mindset to one that is based in restoring, regenerating and giving back habitats and environmental resources. Central to regenerative architecture is the notion of place specificity, transcending conventional sustainability approaches by actively integrating local ecosystems and cultural contexts into design consideration. Indigenous wisdom and vernacular architectures become frameworks for a symbiotic relationship with nature in architectural practice. Equally as important are material choices. Bio-based materials show promise for achieving regenerative outcomes through carbon sequestration and waste utilization, and it is imperative to responsibly source materials while undergoing comprehensive life-cycle assessments. Regenerative architecture will require a complete shift in architectural thinking but will become a moral imperative in face of global environmental challenges.

INTRODUCTION

“Organic buildings are the strength and lightness of the spiders’ spinning, buildings qualified by light, bred by native character to environment, married to the ground.”

—Frank Lloyd Wright

Humankind’s relationship with nature and the act of building has changed throughout time, and with it the way we conceptualize place and engage with materials has followed. Industrialization has fundamentally altered our place in the natural world, and this is reflected in our architecture. The world faces a climate crisis. Unprecedented severe weather events and rising sea levels among a host of other environmental challenges to life on Earth have occurred and will continue to worsen due to climate change. Climate change has been a direct result of human impact and the emission of greenhouse gases (CO 2-eq). According to the World Green Building Council, “buildings are currently

responsible for 39% of global energy-related carbon emissions: 28% from operational emissions, from energy needed to heat, cool and power them, and the remaining 11% from materials and construction.” This astounding statistic presents architects with both an enormous opportunity and a crucial responsibility to deeply incorporate sustainability into their practice.

Within the last two decades, terms such as “emissions” and “resource use” have been part of the debate on sustainability in architecture. However, evidence suggests that reducing waste produced and limiting energy consumed, in other words, a “less-bad” reduction mindset is not enough to combat the climate challenges that humanity is facing. Rather than focusing on limiting human activity that contributes to the degenerative effects of climate change, design going forward needs to be actively contributing to the reversal of these effects. Architecture is on the verge of a new paradigm, one in which regenerative cradle-to-cradle principles are intertwined with architectural design. (McDonough 2002) The viewpoint of buildings as separate from the natural environment must be abandoned in favor of a more integrated approach. The natural next step is regenerative architecture.

Regenerative architecture is not only net-zero emissions but is net-positive on its surroundings and global emissions, restoring and actively regenerating the environment. Buildings should not only be free from fossil fuel usage but should also generate renewable resources. Other related strategies that should be considered are design for disassembly and reuse of construction products, water purification, nitrogen-fixing, and carbon removal processes. For architecture to become truly regenerative, the way we engage with the places and materials that we build into and with needs to be radically transformed. This paper will explore the language and debate surrounding regenerative design and the importance of both place and materials within this kind of thinking.

PARADIGM SHIFT AND LANGUAGE

There have been many well-documented upheavals of style and form within architecture throughout history. With industrialization in the 20th century came a new type of discourse—sustainability in the built environment. In the 1970s

28 Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

and 1980s concerns about building energy consumption and environmental impacts started to gain more traction within architecture following the 1970s energy crisis. Prototyping of renewable energy systems became popular in architectural applications at this time, as well as simulations for energy consumption modeling, and the first energy-neutral buildings were conceptualized. It was not until the early 1990s that the paradigm started to shift and green design became a more commonly embraced idea, by way of ideas from the US Green Building Council. Within the last 20 years, carbon-neutral building has become a reality. Green building codes have been widely adopted worldwide. However, this is not enough. The next step for true sustainable development is regenerative architecture, though the process of implementing this and at what scale is still an area of research and discussion.

Sustainability within architecture is most often defined as “minimiz[ing] negative impacts on building occupants and the environment,” (U.S. General Services Administration). This fits into the less-bad approach of reducing energy use, emissions, and waste. “The Doughnut for Urban Development, a Manual,” developed by leading Scandinavian architecture firms and universities, defines sustainability “as a state in which all human socio-economic activity and systems are scaled within biophysical planetary limits”, which implies that sustainability is not a practice of minimizing impact, rather it is a state that needs to be attained for life on this planet. (Bjørn et al. 2023, 9) Regenerative architecture takes this one step further, proposing buildings that promote life and have a positive impact. In their 2005 book Sustainable Architectures researchers Simon Guy and Steven A. Moore propose a thesis on sustainability: “Sustainability is more a matter of local interpretation than of the setting of objective or universal goals” (Guy and Moore 2005, 1). This statement is particularly powerful because it stresses the importance of place in sustainability. Cultural frameworks and local ecologies influence how people around the world view sustainable practices. Different attitudes towards nature inform design, which in turn impacts nature.

Regenerative architecture is place-specific design and accounts for the impacts of building on local systems and ecology, incorporating them into the design. What distinguishes regenerative design from other approaches is that there is an active focus on regenerating local resources and having a net positive effect on the surroundings, leaving things in a better place for generations to come. The Brundtland Report, an influential publication by a commission directing the nations of the world toward more sustainable development was published in 1987. This report established sustainable development as a concept in the areas of planning, politics, and architecture. The report defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Report 1987, 3.27). This is the most cited definition of sustainability that accounts for both present needs and those of the future.

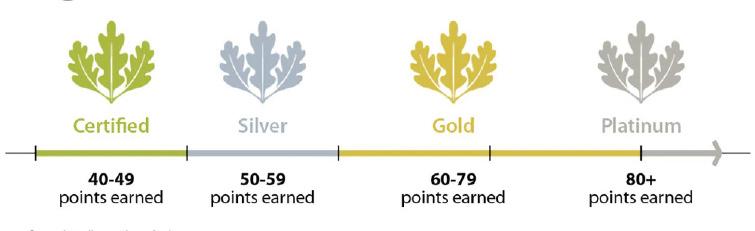

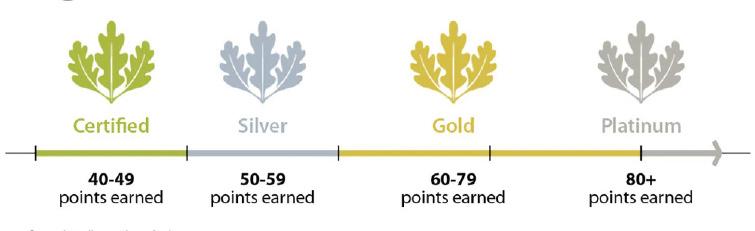

There is much debate about the contents of different national and international sustainability standards. The lack of alignment and consistency of measurable standards between frameworks can make the greater initiative of sustainability in our built environment seem like a very divided effort. Many argue that some of these standards are not doing enough to incorporate the “entire project life cycle and supply chain(s)” (Bjørn et al. 2023, 52). It is not sufficient to account for just carbon emissions and energy consumption. Obtaining and refining materials is not without consequence, and effects on habitat loss, deforestation, erosion, eutrophication, water pollution, and consequential loss of biodiversity are often tough to quantify and are not adequately considered in standards such as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method). BREEAM is based on a weighted scoring system which means that some areas of the assessment are given more importance. This system contrasts with LEED standards which are based on a point system, meaning that if a project gets enough credits for one area, it may not need to get as many in another area, allowing designers to pick and choose. (Fiure 1) Often this results in designers

29 Climate

Figure 1. LEED Ratings and Corresponding Point Values. US Green Building Council.

reaching for the points that are easiest to achieve. Current environmental assessments for buildings also “often [translate] into design as a series of isolated design gestures… rather than encouraging synergies, closing loops, and responding appropriately to the local ecological and social contexts.” (Cole 2012, 42). These standards also commonly look only at performance projections and do not consider actual performance after projects are built. Others, like the Living Building Challenge, do account for actual building performance and are not certified until 12 months of building performance data has been collected and reviewed. Where does regenerative architecture depart from the checklist-based standards that are now commonly used? What is the advantage of a regenerative approach? Regenerative architecture looks to incorporate natural and closed-loop systems, and unlike existing standards, “such an approach requires design to acknowledge and respond to the unique attributes of ‘place’ and secures sustained stakeholder engagement to ensure a project’s future success.” (Cole 2012, 40) Regenerative architecture relies on the links between systems to focus on a more holistic approach rather than incorporating selective strategies to fit a set of criteria or obtain a qualification.

HYPERLOCAL/VERNACULAR – THE ROLE OF PLACE IN ARCHITECTURE

How do we conceptualize place in an increasingly interconnected world? Modernists in the 20th century proposed an architecture based on efficiency, an architecture that is independent of place.

Le Corbusier argues in “Towards a New Architecture” that the role of the house is to be a machine for living, meaning that dwellings have taken on a new meaning as tools that facilitate our lives. The prevailing view from this period—that there is one correct way to build where ornament and beauty are wasted capital and function should define form—still has its remnants in architectural practices and the architecture education of today. (Loos, Sullivan) An ultrafunctional approach to architecture with core design principles set in the Technosphere has largely been adopted in our homes and urban environments leading to a largely placeless and generic built environment in many parts of the world. Architecture that draws deeply from the people and places that it serves is socially and environmentally more sustainable. The book “[Ours] Hyperlocalization of Architecture: Contemporary Sustainable Architecture” explores the role that place plays in sustainability. Projects outlined in this book show how place acts as the catalyst for resilient architecture that is integrated into distinct cultural fabrics and environments. Each of the locations in the book have given rise to different strategies that create cultural and environmental resilience in their contexts, for example, “Australia Unfolds, Japan Condenses, and Denmark Plays.” (Michler 2015)

Examination of place should not be limited to formal architecture built by architects. Many indigenous cultures have co-designed with nature and utilized natural processes sustainably. In her book “Lo—TEK. Design by Radical Indigenism”, Julia Watson, an architect and researcher of nature-based strategies has formed a practice based on local approaches that apply traditional ecological knowledge, or TEK. This book explores indigenous cultures’ nature-based strategies and how they fit into a model of climate resilience. The focus is on scaling these technologies and learning from cultural strategies that prove to be effective and regenerative. Watson writes “In this era of the Anthropocene, humankind will need to redefine the myth of technology to include indigenous innovations,” meaning that there is true knowledge within these nature-based strategies that can be scaled and included in the architecture of today (Watson 2019, 28). Just some of the TEK strategies showcased in the book include the living root bridges of the Kahsis in Meghalaya India (Figure 2), in which growing trees are guided into bridge formations to allow travel between villages during the monsoon season (Watson 2019, 49-65), the floating islands and reed architecture of the Ma’dan people in Iraq that utilizes one local material in a variety of ways way to sustainably engage with aquatic living (Watson 2019, 291-322), and the Acadja Aquaculture system of the Tofinu tribe that increases biodiversity with a high yield. (Watson 2019, 352-380) There is much to learn from indigenous communities on how to live in and with the land in symbiosis. However, these regional practices should not be appropriated to areas where they do not make sense culturally or ecologically. None of these regional, nature-based strategies are one-size-fits-all and are indigenous to their regional contexts. The lesson instead to be taken from this, is that there is true value in building from

30 Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

Figure 2. Living Root Bridges of the Kahsis. Julia Watson.

traditional ecological knowledge for regenerative architecture that makes sense in its place. Symbiosis is a regenerative strategy that can be applied anywhere as architects seek a collaborative relationship with nature.

MATERIAL USE, LIFE CYCLE, BIOMATERIALS

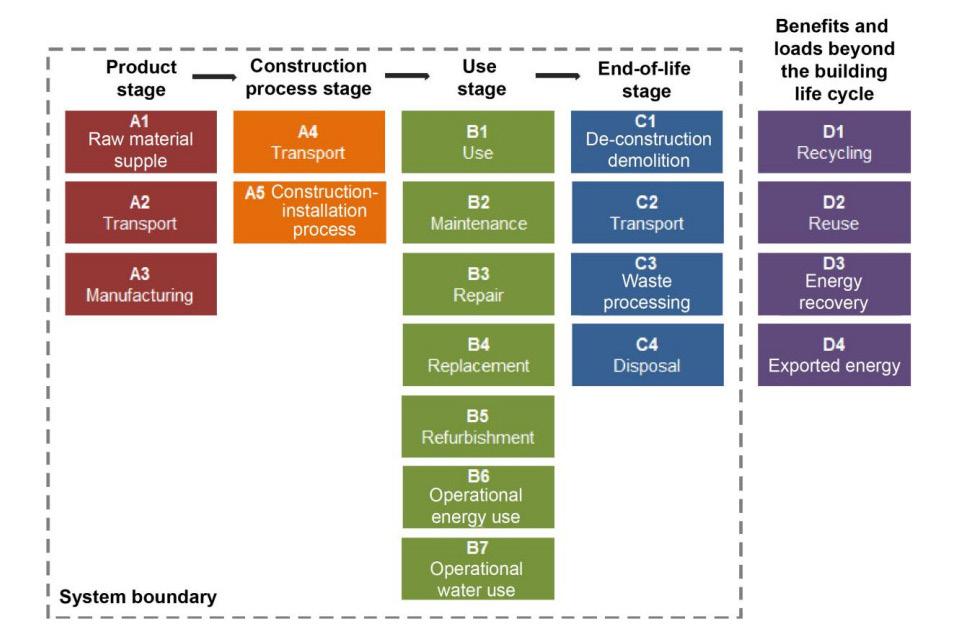

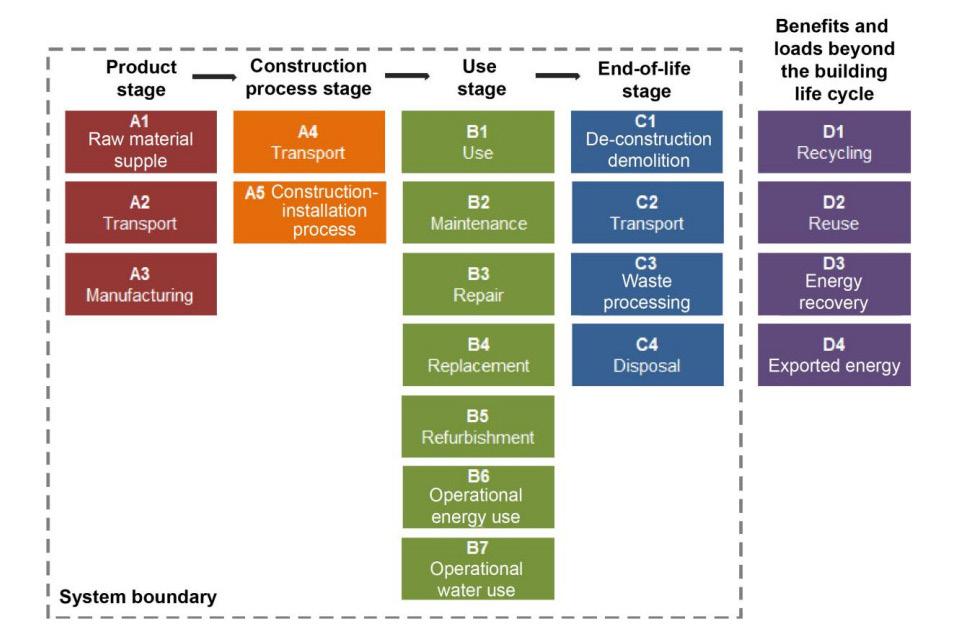

Regenerative design can only be possible if the materials used are responsibly sourced and the effects of obtaining the materials are fully documented, and the full life cycle of the building materials are considered after demolition or reuse. This is where Life Cycle Assessment becomes an important tool. “Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a quantitative methodology that tracks the chemical material and energetic flow in a product system over its full life cycle, connecting the inventory of materials and processes to their impacts on aquatic, terrestrial, atmospheric, and human systems.”(Figure 3) (Carlisle 2016, 172) Rather than looking at sustainability as just something to be evaluated as building performance during operation, it has “evolved… to multi-stage evaluation including product stage, construction stage, and end of life stage.” (Attia 2018, 33) Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment (WBLCA) “estimate[s] the environmental impacts of a building throughout its useful life, including the Global Warming Potential (GWP).” (American Chemistry Council 1) It is important to utilize this process early in the design process so that it can inform the design decisions in tandem with Building Information Modeling (BIM). Different tools pull from material databases, taking spatial information and material quantities from the design and calculating the project life cycle based on the Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) and Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) data available in the databases. Some tools

require manual entry of material information while others can pull BIM data from Revit and similar software. A few of the currently available tools are Tally, EC3, EPIC, cove.tool, BHoM, and One Click LCA. Each of these has different strengths and scopes. For example, EPIC stands for Early Phase Integrated Carbon Assessment and is focused on U.S. regionally specific data, while others may have a larger of scope databases and different functionality. These tools rely on quality data and availability of EPDs sometimes resulting in inconsistencies between assessments. To illustrate this, “Tally[’s] and Athena’s assessment results on the same building assembly revealed up to a 42% variance between their calculated global warming potential” in one study (American Chemistry Council 1). While these tools are limited, WBLCA is still a comprehensive way to study building impact, and the tools used will only continue to improve. Another tool for regenerative architecture is designing for future material use. To fully embrace the cradle-to-cradle principles set forth by architect William McDonough, buildings can be used as material banks that can be repurposed and reused rather than following the traditional cradle-to-grave model after demolition. This can be an integrated approach using BIM as a material passport of sorts for future use.

Bio-based materials in architectural applications are construction materials derived from living matter. Naturally occurring materials such as wood and straw are considered bio-based, but this also includes materials that have been engineered or synthesized such as bioplastic, 3d printed wood, and engineered concrete. A possible advantage of bio-based materials over manufactured materials such as concrete and steel is that

31 Climate

Figure 3. Understanding Whole Building Life-Cycle-Assessment. ArchDaily.

they can sequester carbon, by capturing and storing it within the construction material. Minimizing embodied carbon is key and using materials that have less of an impact is a strategy in most green building assessments, though there are sometimes performance tradeoffs that must be considered when using a bio-based material in place of a manufactured one.

To take this a step further, some bio-based materials even present unique opportunities to actively contribute to regeneration through their physical and chemical properties, consuming waste materials and producing useful resources, building materials, and/or energy. These materials are comprised of or use microbes. Rachel Armstrong is a professor of experimental architecture at Newcastle University School of Architecture and has conducted research in the area of synthetic biology applications for buildings. Her work examines microbes that present a unique opportunity for regeneration through their metabolism. Many of these metabolic systems can turn waste streams into production systems under the right conditions. One might speculate that in the not-so-far-off future, “a synbio revolution in the construction field could lead to sustainable answers to our polluting and downcycling lifestyles, as factories are replaced by “biofactories,” growing products with self-assembling, self-replicating, self-repairing, self-sustaining and self-degrading proprieties of living organisms.” (Persiani et al. 2018, 11) These processes are very much in line with the goal of regenerative design and show promise as an area of future exploration and research.

Two of the materials that are being widely experimented with are mycelium and algae. Mycelium can be combined with other types of biomass (ideally a waste product) by its unique growth

process. Fungus “colonize[s] the substrates or biomass by utilizing wide filamentous branche[s] called hyphae. The fungal mycelium forms a three-dimensional network by growing at the tip and branching out across the substrate. (Marium et al. 2022, 272). After this process, a biocomposite is formed and can be dried or heated to stop further growth. Growth can be controlled within shaped molds for architectural applications. (Figure 4) While not suitable for long spans and being a relatively weak material, mycelium biocomposites are a lightweight material that shows promise in “compression for large scale structures, that is, as dome/vault, tower, and column structural forms” (Armstrong 2023, 115). This is useful for carbon capture if the substrate has sequestered carbon itself; the mycelium serves as a binder that allows the substrate to serve a structural purpose. Algae also shows lots of promise for applications in energy-saving building facades as well as composite materials made from algal biomass. Microalgae can be used in photobioreactors and grown in large quantities. This has multiple uses, including “reduced carbon dioxide emissions, oxygen generation, biofuel production, wastewater treatment and solar heat absorption.” (Armstrong 2023, 8) Photobioreactors can be applied to facades to power the buildings and reduce energy consumption at the same time sequestering carbon. The biomass produced can go on to be used as biofuel or composite building materials. This technology is still being developed and will need longer term analysis in performance and efficiency.

CONCLUSION

The regenerative paradigm is the next step in sustainable development; it can become a reality through careful reconsideration of place and materials. Through a thorough examination of existing standards, it is clear that at this moment environmental policies and standards for the built environment in every country are not doing enough. This is a problem larger than the scope of architecture itself, yet designers still find themselves responsible for doing better. Within the literature, there is still much discussion on how to design regeneratively, how to quantify regenerative design, and at which scale regenerative design can be most effectively carried out. Sustainability is defined differently by different actors and is not one united effort but rather a conglomeration of many approaches. Upon reviewing the literature two distinct approaches have emerged. The first, centered in the technosphere, focuses on the development of new materials and high-tech strategies for performance metrics. The second is based on low-tech adoption of vernacular architectural languages and materials. Over the next century, there will likely be a hybridization of these two approaches as humanity moves away from minimizing our impact on the planet and towards a new era of regeneration and symbiosis with the land we occupy.

32 Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

Figure 4. The Growing Pavilion for Dutch Design Week 2019. Company New Heroes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ARE, Federal Office for Spatial Development. “1987: Brundtland Report.” Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.are. admin.ch/are/en/home/medien-und-publikationen/publikationen/nachhaltige-entwicklung/brundtland-report.html.

Armstrong, Rachel. “Towards the Microbial Home: An Overview of Developments in Next- generation Sustainable Architecture.” Microbial Biotechnology 16, no. 6 (2023): 1112–30. https://doi. org/10.1111/1751-7915.14256.

Attia, Shady. Regenerative and Positive Impact Architecture: Learning from Case Studies. SpringerBriefs in Energy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2018. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-319-66718-8.

Bjørn, A., A. Fanning, A. Branny, C. Clausen, D. Pham, E. Engelbrecht, E. B. Lassen, et al. Doughnut for Urban Development - A Manual. Danish Architectural Press, 2023.

Carlisle, Stephanie. “Getting Beyond Energy: Environmental Impacts, Building Materials, and Climate Change,” 165–77, 2016.

Cole, Raymond. “Transitioning from Green to Regenerative Design.” Building Research & Information 40 (January 1, 2012): 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2011.610608.

Guy, Simon, and Steven A. Moore. Sustainable Architectures: Cultures and Natures in Europe and North America. London, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004. http:// ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/drexel-ebooks/detail. action?docID=200806.

Mariam Jamilah Mohd Fairus, Ezyana Kamal Bahrin, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Enis Natasha, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Noor Arbaain, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Norhayati Ramli, and Universiti Putra Malaysia. “MYCELIUM-BASED COMPOSITE: A WAY FORWARD FOR RENEWABLE MATERIAL.” JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 17, no. 1 (January 31, 2022): 271–80. https://doi.org/10.46754/ jssm.2022.01.018.

Michler, Andrew. [Ours] Hyperlocalization of Architecture: Contemporary Sustainable Archetypes. First edition. Los Angeles, California: eVolo, 2015.

Persiani, Sandra Giulia Linnea, Alessandra Battisti, Sandra Giulia Linnea Persiani, and Alessandra Battisti. “Frontiers of Adaptive Design, Synthetic Biology and Growing Skins for Ephemeral Hybrid Structures.” In Energy-Efficient Approaches in Industrial Applications. IntechOpen, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5772/ intechopen.80867.

Watson, Julia, and Wade Davis. Lo–TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism. TASCHEN GmbH, 2019.

“Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment American Chemistry Council.” American Chemistry Council. Accessed December 15, 2023.

33 Climate

PART II: Creating Contexts

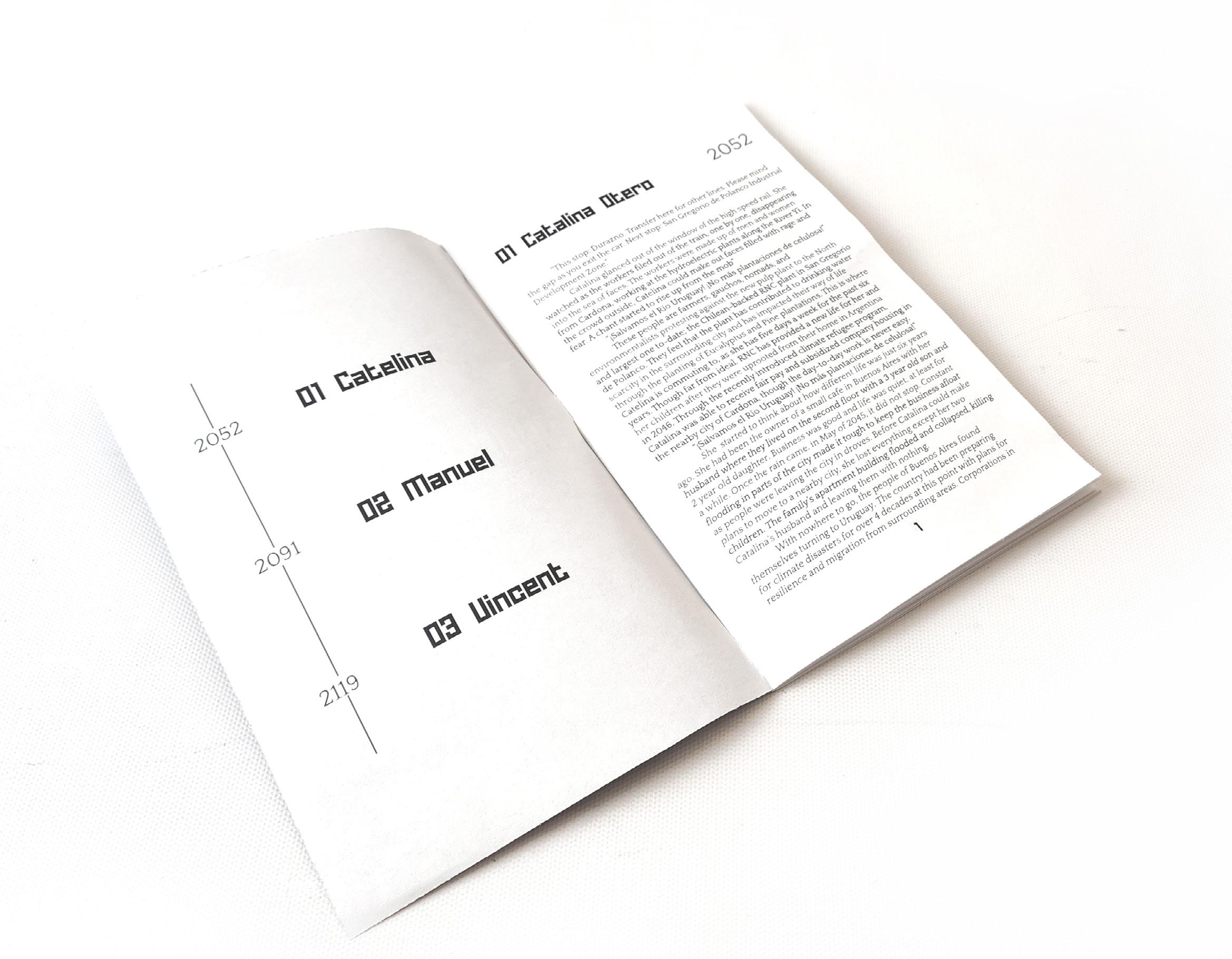

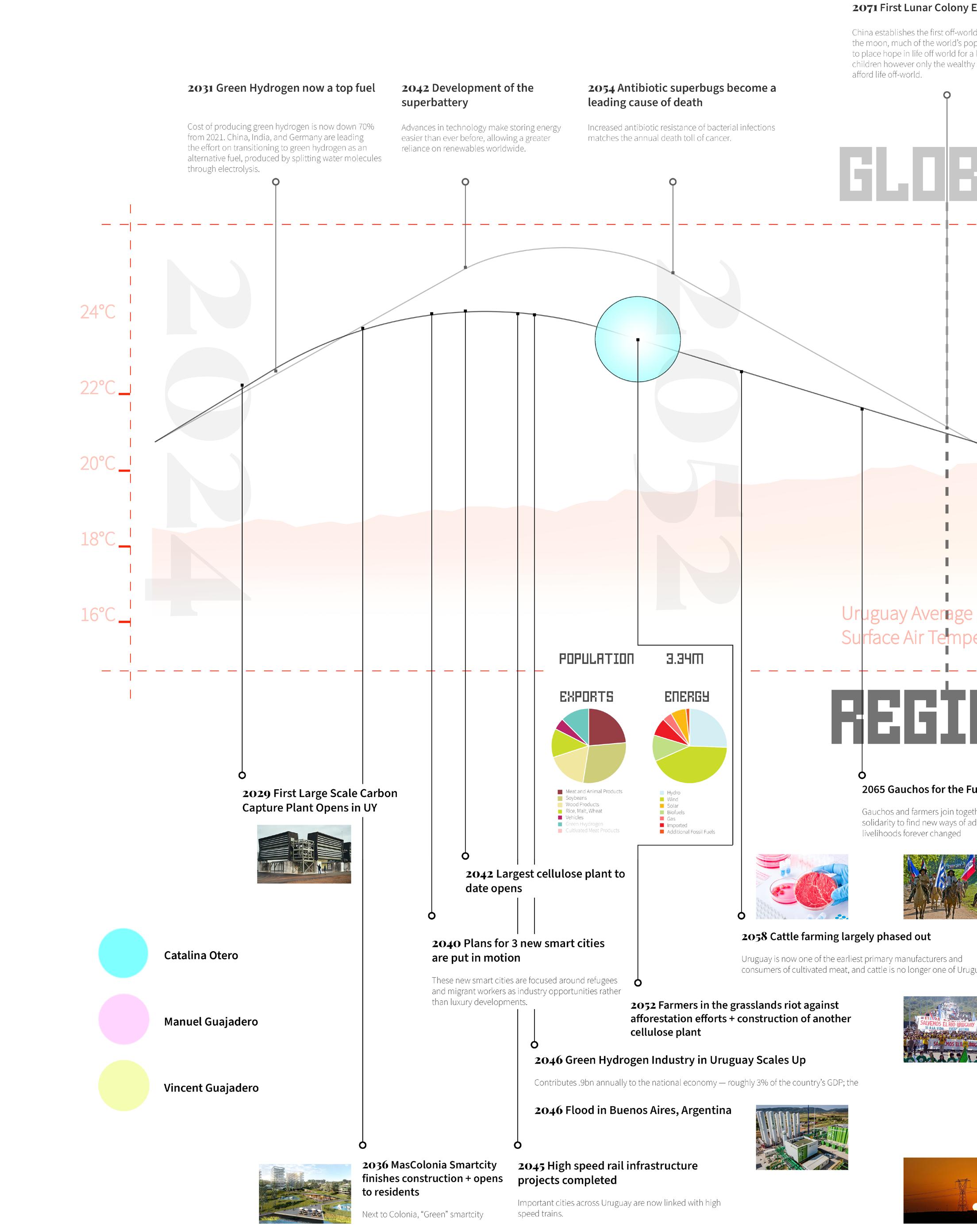

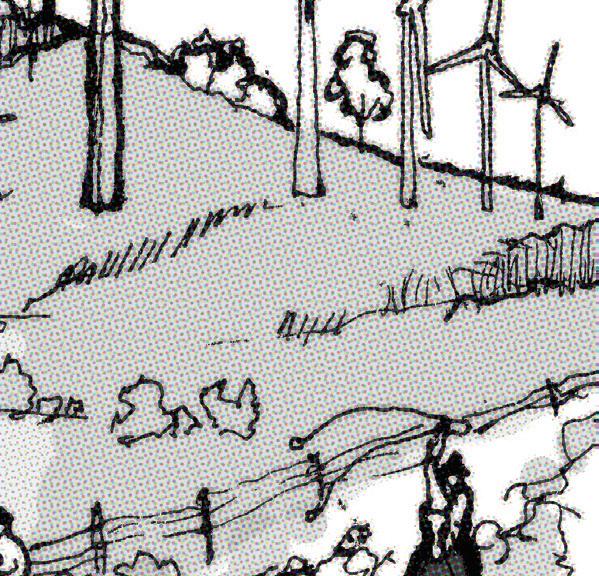

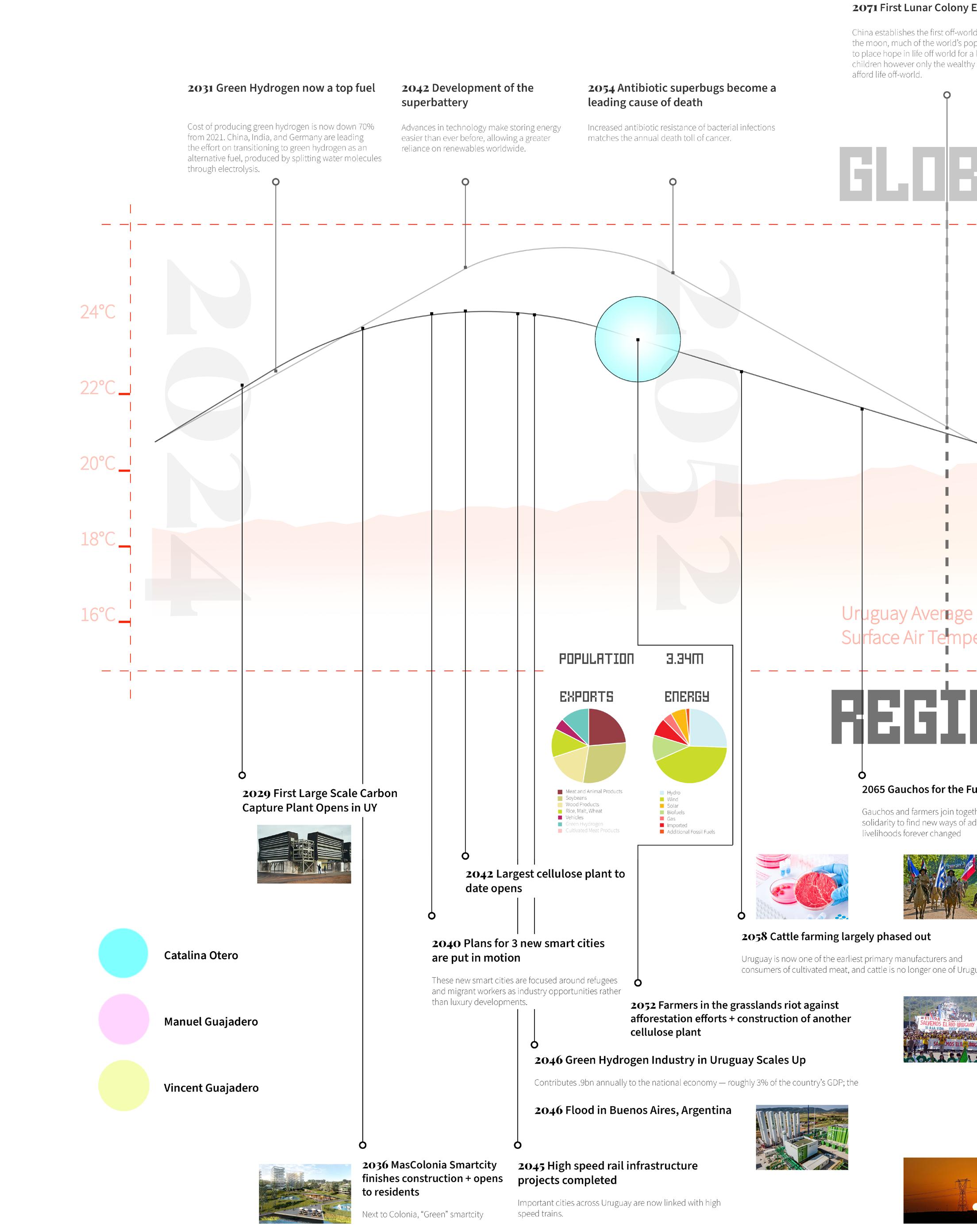

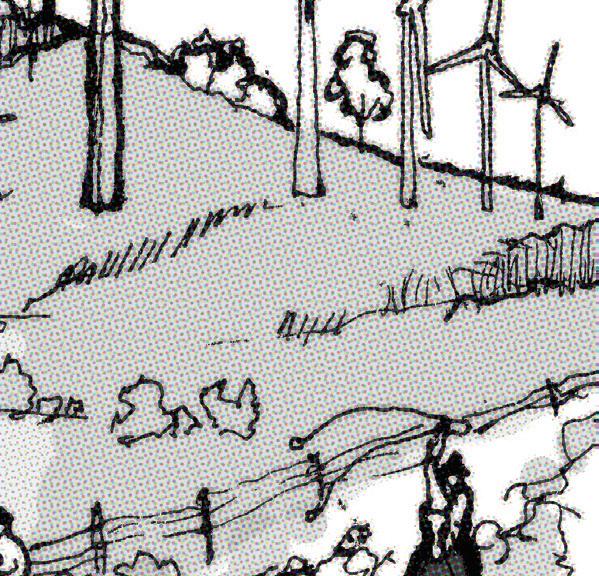

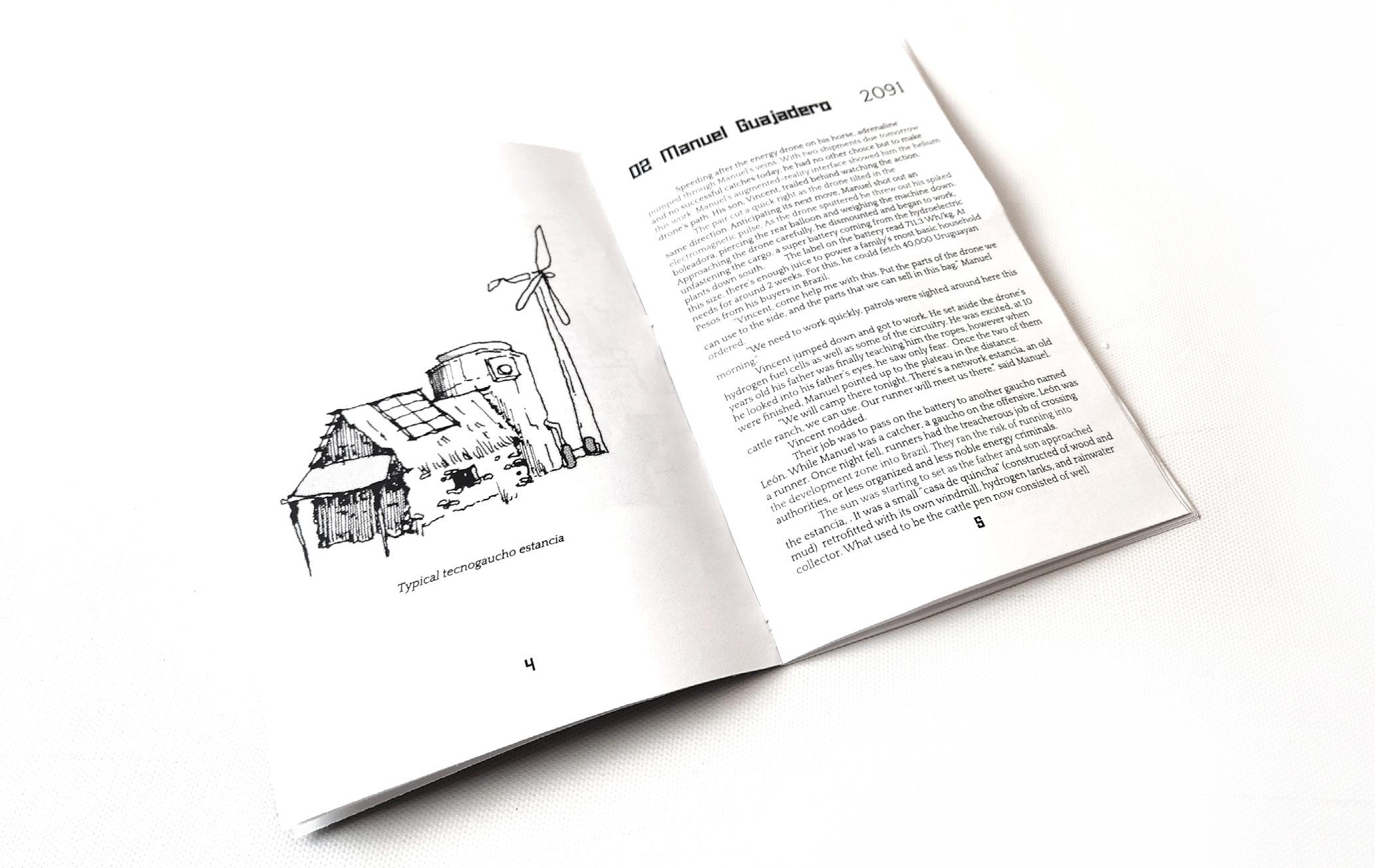

Creating Contexts investigates through design a possible context in which regenerative architecture becomes essential through design fiction. Through the process of meaningful worldbuilding a future timeline was created along with three fictional narratives taking place upon it.

RESEARCH QUESTION

How can design fiction and meaningful worldbuilding be utilized to explore the necessity and implementation of regenerative architecture in the context of Uruguay in the year 2119?

PROCESS AND METHODS

Design Fiction is defined by The Near Future Laboratory as “the practice of creating tangible and evocative prototypes from possible near futures to help discover and represent the consequences of decision making.” Within the theme of regenerative architecture, the aim was to use worldbuilding to imagine a context for regenerative architecture, as well as represent the themes of sustainable development, climate migration, and cultural adaptation. Three narratives were created at different points in the span of 95 years to show how development affects a variety of stakeholders, introducing a region-specific context for regenerative architecture.

34 Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

ALEX PUERTO

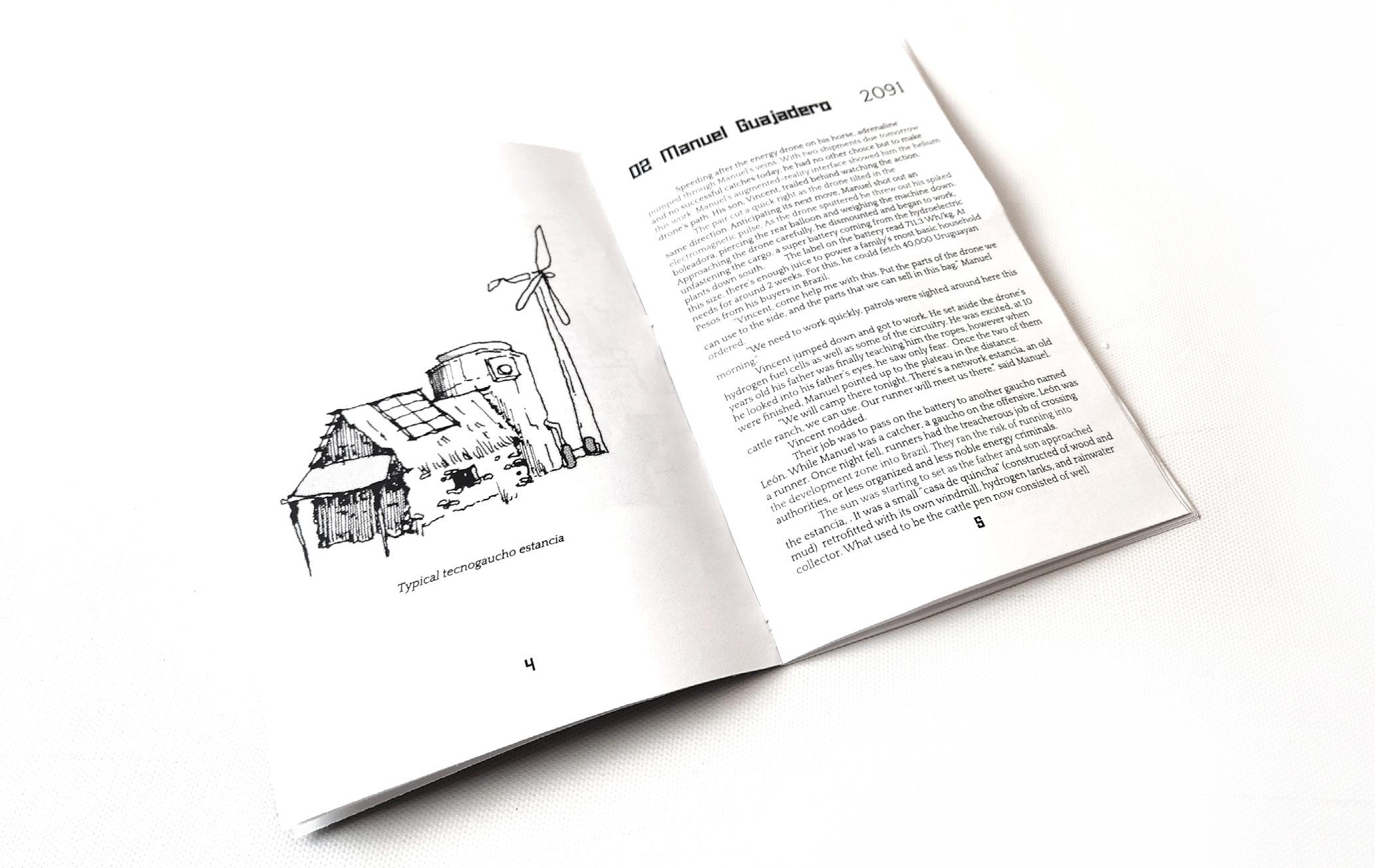

Gauchos at Pintado Wind Farm, Uruguay, The New York Times

Final book Uruguay 2119: 3 Tales from the Future; Alex Puerto

35 Climate

(URUGUAY 2119: 3 TALES FROM THE FUTURE)

CATALINA OTERO, 2052

“This stop: Durazno. Transfer here for other lines. Please mind the gap as you exit the car. Next stop: San Gregorio de Polanco Industrial Development Zone.”

Catalina glanced out of the window of the high speed rail. She watched as the workers filed out of the train, one by one, disappearing into the sea of faces. The workers were made up of men and women from Cardona, working at the hydroelectric plants along the River Yi. In the crowd outside, Catelina could make out faces filled with rage and fear. A chant started to rise up from the mob”

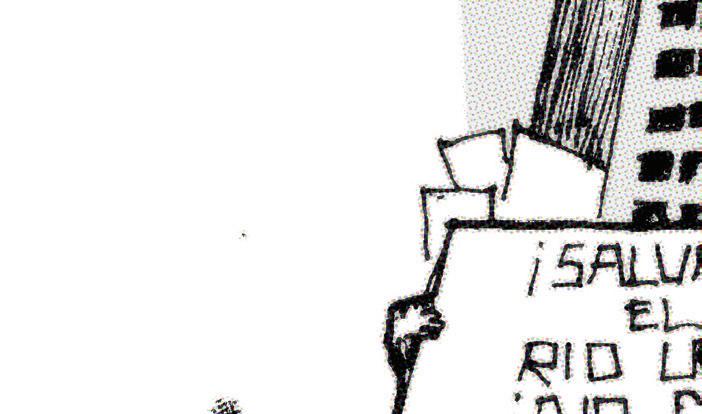

“¡Salvamos el Río Uruguay! ¡No más plantaciones de celulosa!”

These people are farmers, gauchos, nomads, and environmentalists protesting against the new pulp plant to the North and largest one to-date; the Chilean-backed RNC plant in San Gregorio de Polanco. They feel that the plant has contributed to drinking water scarcity in the surrounding city and has impacted their way of life through the planting of Eucalyptus and Pine plantations. This is where Catelina is commuting to, as she has five days a week for the past six years. Though far from ideal, RNC has provided a new life for her and her children after they were uprooted from their home in Argentina in 2046. Through the recently introduced climate refugee program, Catalina was able to receive fair pay and subsidized company housing in the nearby city of Cardona, though the day-to-day work is never easy.

“¡Salvamos el Río Uruguay! ¡No más plantaciones de celulosa!”

She started to think about how different life was just six years ago. She had been the owner of a small cafe in Buenos Aires with her husband where they lived on the second floor with a 3 year old son and 2 year old daughter. Business was good and life was quiet, at least for a while. Once the rain came, in May of 2045, it did not stop. Constant flooding in parts of the city made it tough to keep the business afloat as people were leaving the city in droves. Before Catalina could make plans to move to a nearby city, she lost everything except her two children. The family’s apartment building flooded and collapsed, killing Catalina’s husband and leaving them with nothing.

With nowhere to go, the people of Buenos Aires found themselves turning to Uruguay. The country had been preparing for climate disasters for over 4 decades at this point with plans for resilience and migration from surrounding areas. Corporations in the tax-free zones had already set up smart cities like Cardona, ready for refugees to move in through the Smart City Investment and Expansion Initiative. Within a few weeks, Catelina was set up with a new apartment in one of Cardona’s new large-scale climate refugee developments. The construction was modular, with two bedrooms and two bathrooms. It had everything that

her family needed, with a good school for the children inside of the building. Though Uruguay was setting the standard for refugee housing worldwide, Catelina missed the sense of place that their Buenos Aires apartment had given her: the main criticism of all this new development was that all of the buildings looked more or less the same.

“BANG!”

Someone had thrown a paint bomb, splattering the windows blood red. The car rattled with the sound of protestors smacking the sides of the train. It was an intimidation tactic. The climate refugee assimilation and employment program had prepared Catalina for days like today– the best thing to do was to stay silent and not acknowledge them. After all, the claims that the RNC afforestation efforts were bad for the environment were false anyway, Catalina reassured herself. She was very lucky to have a second chance at life for her children. Chants could still be heard in the distance as the train started to accelerate towards San Gregorio.

MANUEL GUAJADERO, 2091

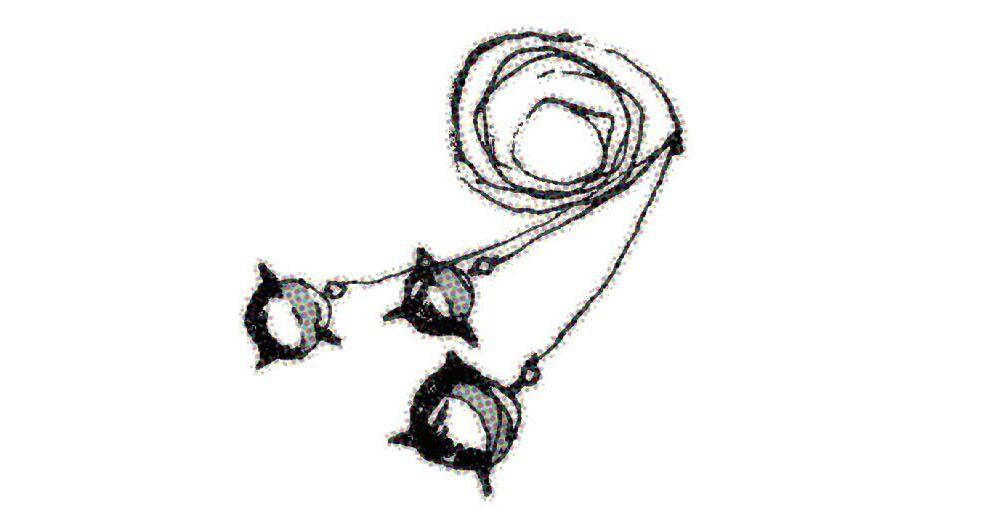

Speeding after the energy drone on his horse, adrenaline pumped through Manuel’s veins. With two shipments due tomorrow and no successful catches today, he had no other choice but to make this work. Manuel’s augmented-reality interface showed him the helium drone’s path. His son, Vincent, trailed behind watching the action.

The pair cut a quick right as the drone tilted in the same direction. Anticipating its next move, Manuel shot out an electromagnetic pulse. As the drone sputtered he threw out his spiked boleadora, piercing the rear balloon and weighing the machine down. Approaching the drone carefully, he dismounted and began to work, unfastening the cargo, a super battery coming from the hydroelectric plants down south. The label on the battery read 711.3 Wh/kg. At this size, there’s enough juice to power a family’s most basic household needs for around 2 weeks. For this, he could fetch 40,000 Uruguayan Pesos from his buyers in Brazil.

“Vincent, come help me with this. Put the parts of the drone we can use to the side, and the parts that we can sell in this bag.” Manuel ordered.

“We need to work quickly, patrols were sighted around here this morning.”

Vincent jumped down and got to work. He set aside the drone’s hydrogen fuel cells as well as some of the circuitry. He was excited, at 10 years old his father was finally teaching him the ropes, however when he looked into his father’s eyes, he saw only fear. Once the two of them were finished, Manuel pointed up to the plateau in the distance.

36 Puerto: Regenerative Architecture

pulp plantation protest. Drawing by Alex Puerto

“We will camp there tonight. There’s a network estancia, an old cattle ranch, we can use. Our runner will meet us there.” said Manuel. Vincent nodded.