FORM

A Space for Ideas, Culture, and Aesthetics

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Jackson Muraika

Ali Rothberg

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Rebecca Boss

Ellie Rothstein

Alyssa Shin

LAYOUT DIRECTOR

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR DIRECTORS OF ART & DESIGN

DIRECTORS OF STYLE

DIRECTOR OF TRAVEL & CULTURE

TRAVEL & CULTURE CONTRIBUTORS

Taylor Delgado

Christina Lee

Sancia Milton

Alveena Nadeem

LAYOUT CONTRIBUTORS

Stephane Bineza

Bethlehem Ferede

Sana Hairadin

Avery Didden

Caroline Rettig

Evelyn Shi

Kaya Hirsch

Sarah Schwartz

Anna Rebello

STYLE CONTRIBUTORS

Anna Brown

Srinjoyi Lahiri

Paige Lind

Karina Lu

EDITORAL CONTRIBUTORS

James Cruikshank

2

3 Table of Contents ART & DESIGN Cowboys&Cupids....8 Reclamation.......................18 Reign.....................................................................32 PoemWrittenInLastYearsRoomReflected...........................................46 TRAVEL & CULTURE JointheClub......................................................52 Down-Home . .............................................................64 MarshSide.............74 CharlestonTravelGuide....84 STYLE In the Vernacular . ........... .......96 ColboNYC...............................................................112 TallTales................................................................126 Backstitch.............130

4

Editor’s Letter

For many, this past year has been a transition back to normalcy. With time now to consider what it is to forego masks, distance, and pervasive anxiety around connection, we see the vestiges of pandemic life still infiltrating our stabilizing community. As Duke University grapples with its new baseline, FORM Magazine looked to make sense of notions of community as we know them. We used this issue to celebrate, mourn, and ultimately embrace this volume’s theme: the concept of kin. We dove into the ways in which community pushes and pulls us to one another, links us together, and makes us kin. We used this year’s issue to explore notions of kin that are generative, working to form connections in a community, some that are intergenerational, looking to remember histories, and others that are present, appreciating kinship as it exists.

We begin our Art & Design section speaking with Yowshien Kuo in Cowboys and Cupids. His work questions limited western notions of Asian-American identity using a personal, empathetic lens. We then speak with Moffat Takadiwa about repurposing consumer residue in Zimbabwe to create art that responds to commercial hegemony in Reclamation. Next, in Reign, Kennedi Carter talks about finding beauty in her own community throughout her growth as a photographer. Last, Poem Written in Last Year’s Room Reflected explores writing as a dual exercise in personal expression.

Our Travel & Culture section begins with Join the Club, a conversation with Matt Cahn from Middle Child, a lunch restaurant that found a missing niche in between fine dining and cheap eats. In Down Home, we speak to Monica and Daniel Edwards of Morehead Manor about their focus on hospitality as they welcome visitors here in Durham, NC. In Marsh Side we highlight two students’ overlapping artistic explorations of nature. Finally, we go south as we explore the music, food, art, and landscape of Charleston, SC.

In the Style section, we start with In the Vernacular, unpacking clothing as a language that lets us balance expression and projection. Next, we speak to Tal Silberstein from Colbo NYC to learn about his curatorial journey in the arts. In Tall Tales, we highlight the potential of storytelling and playing-pretend, realizing that we’re all still playing dress up. To close, Backstitch explores aesthetic concepts that persist across generations.

As FORM shares this issue with the Duke community and beyond, we hope our exploration can bring people just a little bit closer together. These pieces have helped us appreciate kinship through the lens of varied mediums and the eyes of different creatives, with the end goal of sharing this work with our own community at Duke. Just as this volume has allowed us to question, explore, and define what it means to experience kinship, we hope it can help you redefine your own relationship and perspective on kin as well.

Sincerely,

Jackson Muraika & Ali Rothberg

5

Art & Design

6 FORM

Art & Design

7 FORM

COWBOYS & CUPIDS

12 Art & Design

Yowshien Kuo is a St. Louis-based painter who aims to explore notions of Asian-American identity, culture, and history. His surreal, colorful paintings are made up of fine brushstrokes and a smooth acrylic finish. Kuo’s work is layered with symbols that embrace multi-faceted interpretations from both Eastern and Western traditions, a practice that reflects his personal experience. Kuo is currently represented by Luce Gallery in Italy.

Evelyn Shi: Could you tell me about your background and how you became the artist that you are today?

Yowshien Kuo: I was born in the United States, but my parents separated almost immediately after I was born. I ended up spending half my life back in Taiwan with my father and the other half in the United States with my mother.

When I was young, my parents noticed me drawing in my bedroom frequently for long periods of time. I feel like I’m quite lucky, especially given a lot of stereotypes around immigrant parents, because they supported my interest in the visual arts at a young age. In Taiwan, I was studying calligraphy, watercolor, painting, and all the traditions of visual arts from that region. Eventually, I went to art school for a bit, but I was a little disappointed by the experience. I’m not sure why, but I decided not to pursue visual arts for a handful of years and pursued a career in music instead, which was always an auxiliary outlet throughout my life.

Music went well, but I got bored of it and eventually returned back to what felt natural to me, which was the visual arts. I completed my graduate degree when I was almost 30 years old. Once I got my graduate degree, I became an adjunct instructor. I always accredited my presence in the classroom [to] my music experience—playing onstage and being in front of people and having the confidence to convey my ideas are related. Now, I’m working in my studio full-time.

ES: My family is actually also from Taiwan, and I also grew up splitting my time between the US and Taiwan and China, so I can relate.

YK: You know what it’s like, then—navigating your own identity in terms of coming of age and being so desperate to find a place where you fit in. You have all these questions, but a lot of minority groups are not presented with a way to articulate our emotions about our multicultural experience[s]. Therefore, we hold it inside very deeply. And for me, the years of holding it in has found release through the arts, through music, through poetry, through cinema. That’s how we feel like we’re not alone in the world and that we have quite a universal experience.

Evelyn: How do you explore Asian-American identity in your work?

YK: As an art student, I would make paintings that fooled the

13 COWBOYS & CUPIDS

viewer into thinking that only a white person could make these paintings. And then [they would] have this shocking revelation that someone who looks like me, with dark hair and almond-shaped eyes, is making these redneck paintings and celebrating this deep-seated American white culture.

But, that eventually evolved into a conversation that I hope is more effective to the audience—one about inserting Asian bodies into a universal narrative. If I can get audiences to see that Asian bodies are involved in the same emotional world as them, it creates a larger space for empathy. This is a trick that great writers and filmmakers understand very clearly. If you’re watching films by Wong Kar-Wai (a director from Hong Kong), for instance, you don’t have to be Asian to connect with the characters in the story. You can be from any place or culture, and that is very exciting for me. I think my work has become more sophisticated in that regard—it’s not being overly specific but leaving room for the viewer to insert themselves into the scenes that are taking place.

ES: More specifically, your subject matter often includes cowboys in these erotic and fantastical settings. What was the inspiration for this recurring theme?

YK: There are a lot of reasons. Firstly, it is a vehicle to show people what an Asian-American person looks like in a multicultural context. If you paint or show a photograph of an Asian person in the nude or just in daily clothes, we don’t know what sort of cultural background they have. I don’t know if they speak English or if they’re speaking Mandarin or what’s going on. Using the cowboy clothes helped show these people in a place they have historically been alienated from. We’re coming into a space we haven’t been privy to, but we also want to belong.

There’s also the notion of history. Cowboy regalia comes from a time period where a lot of East Asian immigrants started to spread into Western nations. For instance, the Gold Rush era and the building of the Transcontinental Railroad was a period of anti-Chinese propaganda, with the Chinese Exclusion Act during that time as well. I’m also thinking about notions of masculine power that have been present throughout history: the emasculation of AsianAmerican men through the media and law.

On the erotic quality of my work that sometimes appears, I feel like it’s necessary to make the figures feel real and enter our personal space by exposing vulnerabilities that we hide from the public. These are things we don’t want to talk about. Like in one of these paintings, there’s this nude figure flying down, and he’s farting, and the fart becomes the entire universe. There are people being intimate with each other in different ways. These figures want to belong in a place where they’re not fully accepted, but when you fall in love, you are almost blind. You don’t realize the ridiculous things that you think and do. So they are often in this state of embarrassment because they’re clouded by lust.

ES: Tell me about your technical process, your medium of choice, and your artistic process from idea to finish.

YK: My training was very traditional. I was copying Rembrandt and Caravaggio paintings, the Dutch and Italian masters in oil. Now, I primarily use acrylic paints because it gives a modern surface and this plasticky color that works well with my narratives. I’m not trying to portray realism, so I need something that feels relatively synthetic, like I’m constructing a children’s book or a movie set.

I actually mix about 90% of the paints on my own so I can get colors and textures that are unique to each painting. I have a deep interest in design, and what I love about design is that everything is so customized. It’s almost handmade, and it makes me think of ancient artifacts where we can feel the presence of someone’s labor going into the work. Mixing my own paints is very labor-intensive, but it also makes a more memorable effect.

Typically, my work exists in series, so I’ll work on several pieces at once. In terms of process, I usually start with drawings and images, and they’re transferred onto the surface that will eventually become the painting. I have assistants that work with me in the studio—I think of us as a team. We use a lot of nail art, jewelry, glitter, and elements like animal bone. Anything we can get our hands on to make the work authentic and make it feel special and customized.

ES: I noticed that you have really interesting and descriptive titles for your work. What inspires you to title each piece the way that you do?

YK: I feel like it helps the viewer engage in the narrative I’m building. Of course, it doesn’t matter if they get the same story out of it as I do, but I think it helps to bring purpose into what I’m showing. How do you build something that we can emotionally wrap ourselves around without a little bit of guidance on how to shift our perspective? That’s why titles are extremely important to me and something that I think is absolutely necessary for the work to exist.

ES: Where do you see yourself going as an artist?

YK: Short-term, I’m doing a show at Expo Chicago after my exhibition now, and there might be a group show or two in New York after that. I’m happy not knowing what’s coming next. I know we’re always pushing for something that’s not quite there yet, which is the role of the artist throughout their life. It’s like Matisse, the French painter—he had his bowel surgery and cancer and was gonna pass away soon. It was only then, in the last few years of his life, where he was like, “God, give me 10 more years to complete my work.” If nothing else, I think that’s true of any creator. Art is not something we retire from. It’s something you do till the end because you’re constantly searching, growing, and learning. As an artist, there’s nothing more exciting than that sense of discovery.

16 Art & Design

PHOTOGRAPHY courtesy of Yowshien Kuo

WRITING Evelyn Shi

17 COWBOYS & CUPIDS

Reclamation

Caroline Rettig: What led you to pursue art professionally? And, more specifically, what inspired your artistic medium of consumer residue?

Moffat Takadiwa: I grew up in a small town called Tengwe, which is almost 350 km from Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe and art was never a likely option. Subconsciously, I grew up with an appreciation for and memories of being surrounded by various shops with merchandise-lined shelves. From this memory, my work has always been informed by my love for the specific designs of packaging containers and a zeal to accumulate and collect. At some point, the shop merchandise appeared in the streets of Harare and became part of the urban landscape with venders occupying every unusual place; vending noise became the new street noise and culminated in building the new Harare street language and sounds. All of which were translated into my work.

CR: After scrounging through household and industrial waste, how do you develop the intricate designs and shapes of your installations with found materials?

MT: The process of my work usually begins with the mobilization of materials. This is done by my team of about thirty-five people from various dumping sites of Harare, and these people are mostly homeless people who stay in the dumping grounds with their families and have a livelihood around sorting through the dumps for recyclable wastes to sell. The collected items are brought to my studio for cleaning and preparations with my studio team of about ten art students who work on a part-time basis. Most of my materials are worked one item at a time and this is a very tiresome process that demands concentration. For example, some materials like computer keys need to have holes drilled with a two-millimeter drill on four sides of the key. After drilling, the computer keys are then threaded into lines and the lines get fabricated and weaved into shape according to my sketches and instruction to my assistants.

CR:What new meaning do your installations give to consumer residue? Does the meaning of your installations change with a Zimbabwean audience versus a Western audience?

MT: Meanings and narratives given to consumer residue by my various installations keep changing and revolving. Recently, my work has been focusing on the everyday residue in suburban Zimbabwe and expressing issues with cultural dominance propagated through trade. With some works, like ‘The Land of Coca Cola and Colgate,’ this works does not only speak on dominance but also brings ecology

"AMERICA SHIPS TONS OF ITS WASTE TO POOR COUNTRIES AND SOMETIMES THEY DON’T GET TO SEE HOW OTHER COUNTRIES STRUGGLE WITH THEIR RESIDUE."

20 Art & Design

23 RECLAMATION

and land ownership into question. Zimbabwe is the only country which has redistributed land to its people after independence from the British.

Besides being worlds apart, some everyday residues like that of famous brands e.g., Colgate, and Coca Cola, are used and consumed in everyday routines and speak to the common modern-day problems of how we consume so many chemicals and also the everyday struggle of fighting those chemicals.

At one point, I was very interested in the reflections from some of my American audience. America ships tons of its waste to poor countries and sometimes they don’t get to see how other countries struggle with their residue. In my exhibition, I had to explain that Zimbabwe is landlocked, and we don’t necessarily receive some of this waste dumped in Africa, but we rely on secondhand items from different countries around the world and this has paralyzed our industry. My show in Paris, France ‘Vaforomani ndimi mawondonga purazi’ was all about farmworkers and how the suburban residue only represents the objects of their dreams and desires. There is so much poverty in some communities of Zimbabwe and sometimes I speak about that labor which feeds the world and how they lack these everyday basics.

CR: How do your installations reflect the cultural narrative of Zimbabwe and its colonial history? How do your installations challenge Eurocentric and Westernized ideals?

MT: The way I compose most of my work is informed by the Korekore culture of Zimbabwe. Borrowing and researching on African knowledge systems has always been cultivating more curiosity in me and my understanding of shapes, utilitarian objects, and African artifacts. The work ‘The Bull’ is a good example of how I tear through the Eurocentric canons in art. The work was from several sketches I did, with Picasso’s several works on the bull as the inspiration for my work. As much as Picasso was speaking of human brutality in his works like ‘Guernica’, I question Europeans’ brutality on the African people through the suppression of vernacular languages and I highlight the human pureness and the plea hidden in vernacular languages.

CR: I noted you serve as a mentor to artists in Harare, Zimbabwe through your program, Mbare Art Space. What hopes or aspirations do you have for Zimbabwe’s artist community?

“BORROWING AND RESEARCHING ON AFRICAN KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS HAS ALWAYS BEEN CULTIVATING MORE CURIOSITY IN ME AND MY UNDERSTANDING OF SHAPES, UTILITARIAN OBJECTS, AND AFRICAN ARTIFACTS.”

24 Art & Design

27 RECLAMATION

MT: Mbare Art Space (MAS) is a project aimed to amplify the message of urban renewal of the historic township Mbare by fostering talents of Zimbabwean artists at home and internationally. The township of Mbare was founded in 1907 as the first community built for Africans in colonial Zimbabwe to provide labor for the Harare.

The project’s aim is mostly for the brimming artistic talents of Mbare, Zimbabwe and Africans to build a creative community inside a former community beer garden and to incubate and showcase talent with this unlikely community becoming the first consumers.

“FOR MY COUNTRY, ZIMBABWE, IT HAS NOW BEEN FORTY-PLUS YEARS AFTER GAINING OUR INDEPENDENCE FROM COLONIZERS AND WE HAVE DEFINITELY PASSED THE INDEPENDENCE HONEYMOON AND ARE NOW FACED WITH THE REALITIES OF THE COLONIAL HANGOVER AND ITS AFTERTASTE.”

CR: Your installations often address social and ecological issues, what pressing issues do you think you will tackle next?

MT: I am currently working on a body of work in Harare at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe that opens March 16, 2023. In the exhibition, I plan to address the urgent need to eliminate the vestiges of colonialism and its aftermath in Africa - this is more important now more than ever. Zimbabwe has been at the center of land redistribution from the former colonial masters and white minority with many issues on repatriation and restitution gaining momentum throughout the continent. Africa has been struggling to find its footing in the global space. For my country, Zimbabwe, it has now been forty-plus years after gaining our independence from colonizers and we have definitely passed the independence honeymoon and are now faced with the realities of the colonial hangover and its aftertaste.

CR: FORM Magazine represents students with vested interests in arts and culture. What is your advice to emerging artists and other art professionals?

MT: Africa is quickly becoming on the art radar, and it is important for young and emerging professionals from western universities to also have a focus on Africa for its growing influence and beautiful, strong works. It’s also important to understand the shift in knowledge production. Africa has a lot to offer!

28 Art & Design

PHOTOGRAPHY courtesy of Moffat Takadiwa WRITING Caroline Rettig

29 RECLAMATION

31 RECLAMATION

REIGN

A native of Durham, North Carolina, Kennedi Carter has become a leading voice in contemporary photography with her photos gracing the covers of top publications like British Vogue, The New York Times, and Vanity Fair. Her portraiture captures the beauty, resilience, and complexity of Black life. Carter spoke with FORM about projects past and present as well as her experience as a young photographer in the industry.

REIGN

Caroline Rettig: What led you to pursue photography? And, more specifically, what inspired your artistic focus on Black life?

Kennedi Carter: I started my photo work there, and then I decided I wanted to go to UNCG. I ended up leaving there and pursuing freelance work. I think what really ended up drawing me to photograph Black sitters in particular is… I don’t know. I think when I was making work in North Carolina, I was becoming super bored with what was in front of me. While I was getting bored, I don’t think I realized the beauty that was in front of me and in my community. When I started reaching out to various people I was in community with, that’s when I realized what I wanted the primary focus of my process to be or who I wanted it to focus on in particular.

CR: How does living in Durham, North Carolina shape your photography?

KC: It’s just super quiet here, and it gives me more space to think. Working with folks that I had gone to high school with... asking them and their families five years post-graduation or reconnecting with someone that I once knew from high school that could then connect me to a person that I could probably photograph. I think that’s what Durham and North Carolina does; it keeps me grounded, and it keeps me searching for new people to photograph or to find new people that I think are interesting.

JM: Would you say that staying grounded in Durham, North Carolina has been a personal journey for you, in addition to being an artistic one?

KC: I definitely think so. My family is quite small, and I think about them, as well. They’re based in Texas, and the portion of my family that is from Philadelphia, we’re not that close. I think that since my family is so spread out, finding a community of my own and consistently following-up with them, taking their picture, documenting them, archiving them has been very helpful in creating a newfound family of my own.

CR: You have been incredibly successful in both commercial and fine arts photography. Do you foresee yourself continuing to photograph both types?

KC: I think I more so see myself doing fine arts photography in the future and more than likely teaching later on. In regard to editorial, I am likely going to pump the breaks on that within the next three years. I have been doing it primarily for about two years now, and it has become difficult to create a thought of my own without comments from the peanut gallery in the back. When it came time to shoot my personal work, I didn’t have the cacophony of people telling me, “Maybe you should try this, or maybe you should try this.” It was all on me again, and it was becoming super difficult.

35 REIGN

I didn’t know and still feel as though I don’t know how to really trust my own intuition anymore. I think in order to get back to a place that I need to be in order to do my fine artwork, which is what I want to do full-time, I am more than likely going to have to take a step back from editorial.

I think in fine art, you have more room to trust your intuition, because that is what’s expected of you. But, when it comes to editorial, commercial, advertising, you got people you have to please to get paid.

JM: Have you experienced community amongst photographers? If so, how has that helped you along the way?

KC:: I think especially in the most recent years, there has just been a renaissance of Black photographers or Black photography in general. With that comes a great sense of kinship or community or just being in solidarity with someone. I think also with that, you have so many questions that you are able to turn towards your neighbor and ask, which is super helpful. I think especially because when it comes to how much you’re getting paid or advocating for yourself and how much you think you should get paid, it’s helpful to have these people that are going through everything that you’re going through at the same time. In order to get advice whether it’s like working with the clients and getting an idea as to how much you can charge for that or… when you’re selling edition prints, how to sell edition prints, could you connect me to this curator, could you connect me to this editor. For the most part, most of the photographers that I am friends with these days have been willing to help me with this information, or they ask me questions and I give them answers. It’s been very helpful, and I think it’s one of the reasons why I have been able to have the career that I am having.

CR: For your personal fine arts projects, how would you describe your artistic process?

KC: I feel like it’s constantly evolving. Usually, something just piques my interest, and I am like, “Okay, I would like to know a bit more about this thing.” I feel like it usually starts off with a wormhole… and being like, “Oh wow. This is a really great subject matter, or this isn’t something that has been documented enough. How can I fill in the gaps?”

I think that’s where my artistic process starts, and then I think over the course of time, I just keep trying to expand on it and try different things or use different materials, such as maybe I shoot analog, I shoot digital, or I do a cyanotype print or mixed-media project. I’m trying not to keep myself boxed into one particular space these days.

CR: More specifically, with your project Ridin’ Sucka Free, how did you develop that concept?

KC: My mom’s side of the family is from Texas. When I was

36 Art & Design

younger, we would go down the freeway, and there would be people on horseback going down the freeway. I just thought that was super interesting, because dude, we have cars. I think I started reading Beverly Jenkins novels, and she’s in quotations corny but I don’t think she’s corny. She’s a romance novelist, and she would create these vivid scenes of 1800’s Black horseback riders. I was like, “I really think that I could probably do a project on this.” About three years ago, I had gone to Houston for a family event, and there was a trail ride happening that weekend, so I decided I was going to go to one, and I just started going around taking photos of people. And, I just started consistently going to trail rides, sometimes going to different ones, sometimes going to the same ones, as well as reaching out to Black equestrians in North Carolina and in Durham. Everywhere I would go… I would try to find at least one if I could. That’s how the project was born. Lydia Sellers: How did you first gain exposure for your photography? How did you outsource your work and get into the public eye?

KC: I was mainly posting on Instagram, but that could only really take me so far. I knew that I wanted to get my work in front of editors, so what I did was I started submitting images to PhotoVogue, which is an online photography platform that is curated by Vogue Italia. After that, they put some of my images in their photo festival they do every year out in Milan. That is when I started getting a lot of eyes on

38 Art & Design

39 REIGN

my work. I also would go to portfolio reviews every now and then, and I would just consistently follow-up with people and that was very helpful. One of my good friends who is a photographer, Dana Scruggs, she was telling me that you just have to reach out to editors and that you just have to be consistent with them, especially because they’re busy. That was very helpful advice. I felt like my work increased significantly when I was reaching out and just marketing myself, because I didn’t have anyone else to do it at the time. I didn’t have an agent or PR or anything. That’s pretty much how I got started. Another thing I would do was I would go underneath the posts of different photographers that I admired and if they posted an editorial or something they did that was a commission and they tagged the editor they worked with, so I would then follow the editor. That would be another way of me finding a point of contact for a certain magazine. I would also go to the magazine’s website and go find their letterhead or use this website called Rocket Reach, which is super sketchy, but I somehow ended up finessing and finding the emails of various editors.

JM: What is it like now to be in a position where you have this well-established career and can now help the next generation?

KC: I feel like it’s successful in theory, but I feel like I still have more stuff to do, to be honest, especially because after the birth of my son, a lot of my work just fell off. I took a

41 REIGN

six-month maternity leave, and I just wasn’t reaching out to people as consistently as I was before, because I simply didn’t have the energy to do so, and I was rethinking a lot when it came to my relationship with the editorial world. Now, I am like, “Okay, what does success look like for me in regard to the fine art world,” and I am still figuring that out. I think, if anything, how I try to pay things forward is by always being willing to answer questions, because I remember, a few years prior to when I was super serious, whenever I would try to ask questions, there was a period of no one responding. I think that is the best thing someone can do is just not gatekeeping information.

45 REIGN

PHOTOGRAPHY courtesy of Kennedi Carter WRITING Caroline Rettig, Jackson Muraika & Lydia Sellers

Poem Written In Last Years Room Reflected

Would-be what-if, what if. . . We wanted it back, big promise, portent, apocalypse, urgency, plummet, plunge”

― Nathaniel Mackey

“And if an essential thing has flown between us, rare intellectual bird of communication, let us seize it quickly;”

― Muriel Rukeyser

46 Art & Design

Being with you on the worst of days — still choosing my words uncarefully— not tanning in the sun, just sleeping. Just speaking, just sweat, clutching of one moment, no matter how long it lasts. Suffering insistence. Sweeping the leg loudly. You know I want to fuck her before I tell you, you keep this to yourself. You do this; you do that— hung hug and a half moment of hatred we’ve forgotten about. Mixed Emotions. Emitted motions .

“Don’t rile up the dog” but squeak your shoe soulfully. Full stop. A dragon cannot fly over this mountain. But, it can wrap its wings around the tip, including the creatures that lie atop. A new biome— a bright 30-mile crater, for all foot-travelers and clusters of theaters on wheels, their brakes broken for decades.

bubbles of stone, rigid, wiggle out from below sound of a sound of a bark of a dog. things trickle thru salt and lime you had a high voice that worked happy

happenings thru all-being like a shiver. quiet in the house, the imprint was more

audible as a negative wave. Us a shriek in choral mode. polygon of love opening pleasure of doing business with you fancy of seeing you here lightning on the water brightness gone and naught but live ripples were one to feel them. as it does the world shifts we bite into new selves like teeth

A C 47 POEM WRITTEN IN LAST YEARS ROOM REFLECTED

Ducked thru in the slow-quick gap where distant eyes catch. Naturally, we wake up in another world dreamed each morning in the cold auras of rosywinged dawn. Or what we can have agency in. Enjamb each flashback into the other one. Invisible farce we walk in; all riddles to art, if thought can hit a nerve cluster. Stirred fluster. Who sleeps in this caldera?

How many Jokes can we make about kissing nuns? or about polyamorous nuns loving economics? Who’s to say at this point we lay down at the foot of the tub and ask ourselves to shout curse words until we feel it at the base of our heels and the tip of our big toe.

I happen to think that keeps us human & this whole thing healthy. How tangy is the honey? How tart the summer okra? If I could write a whole book of epigraphs: guess; Yesterday, Maia reminded me we used to kiss, but it didn’t have the effect she wanted. It zigged and zagged up and down to the stairs of the house, shrieking in staccato, in discordant tones, no less beautiful than ever before. It reminded me that I need a new bookshelf, dark wood is preferred.

D

B 48 Art & Design

“What, in other words, is possible in the infinity, if indeed it is an infinity, between one and two?”

― Olivia Michiko Gagnon, “The Between”

What is viscous and vicious enough to bring us here? What has passed between you and I, I want to ask, knowing there’s no correct answer. Dungeons and dragons failed, but the scarf stand still stands. Galaxy brain leviathan, or swimming round those murky synapses. A world that loves back in some awful way. Now and when— a thick sea seething. My memory of that first walk rose like a cinnamon stick in one of Jolie’s soups— almost forgotten but not quite gone. Like, how when you focus on the white of a goose it’s like there was never black. Hopepunk once you realize it was always just in your peripheral. Serenity of an old shock. Jolie strutting pompous circumstance / in some always elsewhere. Reflection on an echo, but we’re all that ever was/is though.

WRITING Becca Schneid & Dylan Haston

E.

49 POEM WRITTEN IN LAST YEARS ROOM REFLECTED

Travel & Culture

50 FORM

Travel & Culture

51 FORM

JOIN THE CLUB

Philly native Matt Cahn opened Middle Child, a sandwich spot in the heart of his city, to celebrate a culinary intermediate that he didn’t see: lunch food somewhere in between fine dining and cheap-eats. In fall 2021, Cahn expanded his business, opening Middle Child Clubhouse, where he brought his unique culinary taste to dinner as well. Cahn spoke with FORM about the importance of community and the creative roots that inspire his menu.

Jackson Muraika: So could you tell me a bit about your background? Where are you from and how did you get involved with food?

Matt Cahn: I was always obsessed with food my whole life, particularly cheap eats. Fine dining was never my thing. I just love street food and delis and hoagies. My whole life, I was kind of obsessed.

I always joked around with my friends about opening a sandwich shop. I remember in college I did a sandwich draft, you know, to be like, what would our menu be if you only had five items and that kind of thing…It’s like playing marry, fuck, kill with hoagies, sandwiches we know and love. You know, all those things — I was kind of obsessed.

I was an English major in college…I was going to be a professor and then moved to New York to work in advertising. I did an internship at DDB and ended up really falling in love with it. So after my internship, I applied for a couple of gigs and got an account exec position at Deutsche, which is about as big and creative as you can be for an agency, like Mad Men style.

I worked there for a little while, and got a little sick of it. So I quit and used the money that I had saved up to go travel around Asia and ate a shit ton of food there. That was always the thing for me; I go to a place and I just like to eat my face off. Everywhere I go I eat crazy food. I just love trying anything.

So I came back and I moved to Colorado for a year to do the ski season and had to pick up a gig there. There weren’t a lot of creative gigs. I couldn’t find anything in copywriting or account exec or whatever. So, I just started flipping burgers. The rent was cheap…I could live off it, as long as I had my ski pass. I was good. I was flipping burgers and just really loved it. I worked the register some nights. And it felt really natural to me. I really liked making people happy.

And, I like to serve the people. You know, I fell in love with it. And then afterwards, I moved back to New York. I worked at Court Street grocers which is probably the greatest sandwich shop of all time. I worked there for a couple of years—worked my way from register guy to cook, then to prep cook, then to kitchen manager, then to manager.

While I was there I was also doing double duty and working at Superiority Burger front-of-house which was like a vegan burger spot Run by Chef Brooks Hadley who was like the

54 Travel & Culture

55 JOIN THE CLUB

56 Travel & Culture

whole pastry chef from Del Posto. So yeah, really really fancy high-quality like Michelin star. I kept working at Court Street and was sort of joking around looking for some spaces in Philly.

I was always really wary of opening a sandwich shop in Philly because there’s so many. Sandwiches are so blue collar and lunch food is so important to the community. There’s so much competition. It’s so good. But, the New York problem started to happen…a lot of the places that I grew up going to started closing. Snow White Diner closed, and Little Pete’s Diner closed and Salivarius, which was my favorite hoagie shop, closed. I was kind of like: What the fuck is going on? Why are these places closing and Starbucks opening up? We really should maintain that sense of community. So, I had written a business plan on my own and found, in Philly, a space with really cheap rent that was a lunch spot that was basically turnkey, meaning I didn’t have to do any construction to it… So, I moved home with my parents as I started redoing the space. And, yeah, got Middle Child open. And the rest was history, I guess.

JM: What you said about the modesty of the food scene in Philly is really interesting. My mom went to college in Philadelphia and told me about the food truck she would frequent when she was a student there. But there is also an element of pushing the culinary envelope at Middle Child.

MC: There are two sorts of opposite tendencies, right? It’s like one is to serve a community, which means to know everybody’s name, have good relationships with the neighborhood that we work in, do donation efforts, internally having a good relationship amongst our staff, and then a desire to make really interesting food… Making really interesting food costs a lot of money.

So for Middle Child, and sort of always, [there’s] a balance between pushing the envelope, while at the same time, maintaining about a $13 price point for our sandwiches… We want to be really creative and create cool shit, but we don’t want to make it so weird that we are pricing or sort of boxing out, you know, a nurse from the Northeast who grew up on cheesesteak. So what we’re always trying to do is to push the envelope while also creating a sense of community.

It’s like being like the people shop versus being, you know, the chef’s shop. And I feel like we end up falling somewhere in between because what we’re doing is like, we always base our dishes on classics and things that people know and love, you know, a turkey club, a bowl of pho. Inspiration can come from different places, it doesn’t have to be a sandwich. We can kind of push that further, in simple ways that are low barrier to entry. We’re not making a duck pate club. Just making a cranberry miso club. So it’s like a little bit more dry, a little bit sweet. It’s got avocado on it. It’s a little more modern in that way. We’re able to sort of maintain that $13 price point but we can feed the chefs, and we can feed the nurses.

57 JOIN THE CLUB

JM: With Middle Child Clubhouse, you now have a bigger space and can expand your menu to dinner, offer drinks and that sort of thing. How has it been to have fewer constraints in terms of size and what you can offer as far as food?

Yeah, it’s a new set of constraints and it’s a new sort of pressure, right? Before, we used to only have to sell 16 seats at a time, we had to do a lot of volume to make money, but now I have to fill 120 seats. So I have to be a little bit more conscious of what people want, right? Like, I can’t just do freaky shit anymore. Because, I can’t fill those seats. I need to have a burger on the menu, I need to have a Caesar salad on the menu. It’s sort of similar things that keep people coming back. And now we have tables of eight. So before, if somebody comes in with their mom, and their mom doesn’t like it, I’m like: “Sorry, Mom.” Now, someone comes over the table of six and their grandmother, their mom, and I have to figure out how to make them all happy. So that’s a challenge. At the same time, it is so rewarding to have an opportunity to make dinner.

We just get to do so many things that influence us [with Clubhouse] and Middle Child. One is very small. Before it was like, I go on a trip and I come back, and I’m like, here are fucking 100 things I want to do. We don’t have a lot of space, we have cooking limitations, labor limitations, space limitations. We cook everything out of Middle Child from an induction burner and one oven, which is crazy. And with Clubhouse, we were able to expand that in so many ways. I could come up with something and be inspired by something and do it as a cheap turkey sandwich, or I could do it as a beautiful ceviche. It’s really rewarding to be able to do that.

JM: I love how you constantly add new things to the menu or release things short-term. It feels like a constant creative expression of food.

MC: No doubt. I mean it’s vital; it’s the only thing that keeps me going. We’ll get to that place where we sort of have a menu that’s finished. And we maybe only have one special going at a time. But that’s years down the road. Like, that’s what happened with Middle Child, like, things changed everyday at Middle Child and five years later, I found what I love here. I’m gonna move on to making higher quality dinner. And then from there, you know, we’ll see what happens next. I’m super ADD, super driven and want to keep things changing. I don’t like stasis. I want people to come in every time and expect something different. It’s just fucking fun.

JM: Like I mentioned before, the theme of this issue is kin. You talked a bit about this relationship between you and your staff. Five years in, what has your Middle Child experience taught you about fostering relationships?

MC: For me, it’s absolutely something not a damn thing without the people who come in and people who work for us, and that there is no amount of money that I can make that

58 Travel & Culture

59 JOIN THE CLUB

60 Travel & Culture

would make me happy [while] not having my customers happy, and not having my employees happy. So at this point in my career it’s like, I could take it, and I could go try to franchise it, or I could do whatever it is to try to make money off of it. But that’s not what it is. I want to create a sense of community. And like, that’s what restaurants were, when they were diners, and delis, and foster shops. So, I think maybe I won’t make as much money as [I could], but that’s fine. If my employees are happy, they’re feeling well paid. They’re taking care of their benefits. They don’t work 60 hours a week. All of my cooks work 40 hours a week. The executive chef works 50 hours a week, Monday to Friday, Saturday and Sunday off. There’s a quality of life that we have, you know.

JM: Beyond the food, the look and personality of the restaurants is very palpable. And I’ve seen that you collaborated with a local web designer to create an incredible website and worked with a furniture designer for the sign outside [Middle Child]. How have you collaborated with other people to realize your vision for the restaurants?

MC: Yeah, I mean, restaurants can’t just be about the food anymore. I don’t see any reason why I shouldn’t put the exact same attention into my sign as I do my sandwiches, you know. The level of detail that I have and want to have doesn’t stop with the food that we serve. That’s just a lifestyle I have. I want things to be great; I want them to be beautiful, I want to collaborate, you know. Sometimes I collaborate with other chefs, and sometimes I collaborate with other artists. I want to use Middle Child as a platform, not just for myself, but for everybody around me, you know, going back to the idea of community. Like, why would I pay a big corporate sign painter to come in and make a sign for me when I can find a local Philadelphia artist to come do it and use my platform on Instagram to post about them, so that people know, maybe they make more money and then they can put people on. So I always just think about it as rising tides. I’m happy and blessed that people have supported us and that we have a platform, and I can use that platform to give people the same opportunity.

JM: What does the name ‘Middle Child’ mean to you?

MC: It was just a couple things. My initials are MC. So I thought that was cute. But that’s not where I started. That was just by chance.

Yeah, so basically, we chose Middle Child because lunch was our main thing, and it was the middle child between breakfast and between dinner. Everybody wakes up wanting to eat breakfast. And then they’re really excited to make reservations for dinner, but they eat whatever crap for lunch, because they’re just eating at their desk. And I was like, we could do that. We could do a better option for somebody to eat at their desks…We were kind of like outcasts. We weren’t quite cheap eats, and we weren’t quite fine dining. So, I felt like we were the middle child of the industry.

61 JOIN THE CLUB

D O W N H O M E .

66 Travel & Culture

Monica and Daniel Edwards of Morehead Manor see their hospitality work placing them as ambassadors of the Durham, NC community. Having lived in Durham for thirty years, the couple cherises sharing their extensive knowledge and connection to the city with visitors. Their bed and breakfast puts them in a unique position to explore a passion for design while experiencing the excitement of human connection through hospitality.

Anna Rebello: One of the biggest appeals of a bed and breakfast like this is the charm and the character that comes with a house that has some age. When you were starting the inn, how did you come across this space?

Monica Edwards: It was something we fell into, I guess you could say. Back in 1995, we had our first stay at a bed and breakfast. Ever since Daniel and I had been together, we’ve had people living with us. We planned parties and events. When I got to the Inn, I was like, “Man, we could do this and get paid for it.”

Whenever Daniel was not working as a police officer, he would do artsy projects like redoing the house, and I would farm him out to friends and family. He would say, “I’m not sure I’m good at what I do. You can’t tell me I’m good because you’re not a professional.”

Daniel eventually went to work for Jack Mitchell of Mitchell’s Designs, who had been an interior designer in Durham for over 50 years. It didn’t take two weeks for Jack to tell him “Daniel, I’ve worked with a lot of people, and I’ve never seen anybody with as much talent as you.”

Daniel told Jack that he was looking for the perfect place to open a [bed and breakfast]. Jack asked him where would want it to be and how much money he had—to which my husband said, “I have no idea, but I know it’s the right place when I see it.” Over the course of their conversation, this property came to mind, but it was not for sale. Jack knew the owner at the time, so Daniel asked Jack to help set up a meeting between them.

Edgar Thomas, the owner at the time, described the intimate details of the house. He talked about the Italian marble and where this bookshelf came from. Daniel kept pointing across every room saying, “We’re going to do this here, and this here.” He had found the perfect place. Daniel is a visionary. I’ve learned to trust his sight because he can see way past what I can imagine.

We get in the car after the tour, and my eyes are glazed over because I’m totally overwhelmed. Starting a [bed and breakfast] was something we’re supposed to do closer to retirement. This was August 1996. I wasn’t in a position to retire at 30.

But, I immediately started making an outline as if we’re

going to start this bed and breakfast. We needed a business plan, we had to get financing, we had to do all these things. It took us from August to October to negotiate a price for the house. We closed on the house in February of 1997, and we opened our doors in April.

AR: When you first opened your bed and breakfast, how did your background in the hospitality industry help you ease into running your business?

ME: I graduated in 1984 with a degree in Human Resource Management from East Carolina University, and ECU was one of the first universities to offer a business administration major with a concentration in human resource management. Working with accounting and being in finance helped me a lot because I needed to know how to do financials to run our bed and breakfast.

AR: With an old house, you guys have done a great job of highlighting the historic charm of it. What is its history?

ME: We’re the fourth owner and third family to own this house. The house was built in 1892 by James Cobb, who was one of Durham’s founding tobacconists. When he passed away in the mid 1930s, Edgar Thomas’ father bought the house from Cobb’s widow. He lived here with his family until he passed away in the mid 60s. Then, Edgar Jr., his oldest son, bought out his brothers and sisters to live in this house. That’s who we bought the house from when we started our bed and breakfast journey.

AR: Do you constantly want to rearrange or improve the inn, or do you feel like you’ve settled in a good system for the time being?

DE: This property is 112 years old. By the time I finish my last project, something else needs my attention. My ultimate goal is to create a space that feels like we’re on vacation every day. I want it to feel like such a wonderful space that when guests arrive, they’re surprised.

AR: Where have you found the most exciting projects in renovating the inn? What have you liked the most about making this space your own?

DE: My best renovation is always the last space I worked on. That’s where I find my joy. Right now, it’s the side porch. Finalizing the end result of a project is therapy for me. That feeling kept me from becoming the police officer that we see on the news—who is cynical and who doesn’t trust themselves or anyone else. Designing and renovating gave me the opportunity to remain a healthy person.

Space wise, I love the design of this building. I love old homes; I love their architecture. This space has given me a palette that I can play with.

67 DOWN HOME

AR: When you were growing up, was there anything that inspired your eye for design?

DE: My mother used to tell me I was going to break the legs off the furniture, because every Friday when I was younger, I would rearrange my bedroom. I was immersed in Feng Shui before I even knew what that word meant. My foundation was about creating a feeling. I have dubbed myself as a Black Ricardo Montalban—in giving people something that they have at home but presenting in such a way that it feels special.

ME: At Morehead Manor, we try to put things in place for guests to make their stay an enjoyable experience that they didn’t know was really needed.

AR: The all-encompassing mission of Morehead Manor is having elegance, excitement, and hospitality meet. How do you feel connected with that idea in the day-to-day operations of hosting guests at the Inn?

ME: One of the things that stood out to us when we were frequently staying in bed and breakfasts was when the innkeepers checked us in, we oftentimes didn’t see them anymore after that. The next morning, they would serve breakfast, but then you were left at your leisure.

Daniel and I see ourselves as ambassadors to the city of Durham. When we check in people in the afternoon, the first thing I ask is if this is their first time in Durham. And if they don’t already have dinner plans, I always offer to give recommendations. We like to sit down with our guests at breakfast time and ask about their plans for the day and what they’d like to see while they’re here.

AR: Do you find yourself keeping your recommendations local when advising the guests on what to do during their stay?

ME: Because we’ve been here 25 years, we have developed relationships with other small businesses over the period of time. Durham has many restaurants, so Daniel and I try to visit the restaurants that we refer people to.

DE: Another thing we have done and we’re looking at starting up again in the spring is a scavenger hunt in the city of Durham, which involves many of the small local businesses, acting as a self-guided tour.

ME: Between the Durham Bulls baseball team, the Durham Performing Arts Center, and the local festivals, there’s always something going on. By connecting with other businesses on social media, we keep tabs on what’s happening in the area so we can make timely recommendations for our guests.

AR: There’s no doubt that the pandemic heavily impacted the hospitality industry—especially when it came to people being comfortable enough to leave their houses. What were

some of the effects of the pandemic on running the inn?

ME: During the pandemic, we launched a campaign called “Stay Safe, Stay Small, Stay Inn.” At that time, there were a lot of hotel goers that converted to staying in b&bs. As a smaller establishment, people felt safer staying with us because there was going to be less traffic and not as many people staying on our property.

AR: How are you able to balance your work life and your personal life when it’s all so intertwined?

ME: Running the inn has become a lifestyle. We try to set up the inn to be self-sufficient. Once we check in and show around our guests, they have access to a digitized Guest Services book that has a link to the local visitors guide. Even with that, we’re still a call or text away if our guests need something.

We enjoy the lifestyle that we’ve grown accustomed to here at the inn. Even when we have difficult days, to me, it’s a blip in the schedule to make us appreciate all the other good days that we’ve had.

DE: That’s what it’s about, that appreciation. One of our guests asked us, “How does it feel to be African-American doing what we do at the level at which we do it?” It’s very humbling. Understanding the history of a city like Durham, we see that this is magical. I take no guests or day for granted.

AR: You two have built an environment in the inn that truly represents family and hospitality. Where do you find moments of kinship in your everyday operations at Morehead Manor?

ME: In interactions with our guests, because we find that we’re more alike than we are different, no matter where they are from. One year for Duke’s Parents Weekend, two families that sat near each other in the breakfast room were from opposite ends of the block at home and they didn’t know each other. They met their neighbors here, and now they go back to California and they’re friends.

DE: It’s all about connection. Connecting, as a model, is simple: Be a nice human.

ME: Our home is also our business. We have a personal life, too, so we try to incorporate our guests into those things. Like every Thursday night is bocce night at the inn. If Daniel and I have friends over and we’re out in the garden, and guests come out, we welcome them to join us.

AR: How have you been able to make a name for yourself in a city like Durham?

ME: Word of mouth is key. Durham has a lot of people, especially since the pandemic, that have concentrated

68 Travel & Culture

69 DOWN HOME

more on supporting locally owned businesses, because they understand the importance of keeping money local. There is definitely a cohesive community here.

AR: Daniel, what was your experience like growing up in Durham? How have you seen the city change throughout your life, especially since you started the inn?

DE: We’re legacies of the Black Wall Street.

ME: Daniel’s mom graduated from the Old Hillside High School. She was a participant of the Great Migration in the 1950s: when Blacks graduated from high school in the South, they migrated to the North for better opportunities.

A lot of Blacks that matriculated to the North have moved back south. Nobody returns to the North, but everyone comes back to the South. That’s basically what Daniel’s mother did; he was back in Durham before he graduated from high school.

DE: Durham has since done a 180: population wise, culturally, the overall design and feel. We have new attitudes that are bringing a lot more opportunities.

On one hand, that’s a good thing. On the other hand, there are some who can’t afford to stay here through gentrification. It’s a struggle. We’re fortunate enough to be somewhere in the middle where we can hold on.

Durham was the first place I’ve experienced racism. At some point, you need to know what it feels like, in order to really tie things together for yourself. Durham has given me wonderful opportunities to get to know me.

It was our fate to be here. When we purchased this property, Durham had less than 100 people living downtown. Since then, Downtown has exploded, which has allowed us to be close enough to be a part of it.

AR: …But not too close to where things are stepping on your toes.

ME: Exactly. The beautiful thing about our location is that guests can come here and park their cars and walk to all the things downtown. We tell our guests if they’re having a date night or going to the DPAC, it’ll take you less time to walk down there and back than to deal with parking your car or calling an Uber.

This particular neighborhood is historically designed. We’ve historically designated it so that you can’t just come and put up a convenience store across the street.

AR: Maintaining that integrity is not always the easiest thing to do. Those innovations might be very fruitful for a business, but in maintaining the motto you have here at

Morehead Manor—“keeping the elegance and excitement in hospitality”—there’s clearly a lot of value in sticking to the classics.

DE: It doesn’t have to be extra: Do the basics well, make sure it’s functional. You can’t go wrong with that. So now it’s just a matter of choice: How can we create a space that people want to be a part of?

I have dubbed Morehead Manor as a charging station. We go out and give all this energy by connecting with people and living our lives. You have to reset, and this space allows people to do that.

PHOTOGRAPHY Jackson Muraika

72 Travel & Culture

WRITING Anna Rebello

73 DOWN HOME

marsh side

PHOTOGRAPHY Christina Lee & Jackson Muraika

PHOTOGRAPHY Christina Lee & Jackson Muraika

74 Travel & Culture

WRITING James Cruikshank

75 MARSH

Spartina from the Storm

I go to see the marsh grass each day, the swaying green bringing jubilation to the sound’s fringes, I go to see it as the sun sets when it glows a flaxen yellow, radiation from its fingertips,

It is the life of the isles before dusk.

Last summer the storm raised up choppy waters, As the surge swallowed the snails atop the golden refuge, those spears waged war against the inexorable current, from their muddy roots, from the elements.

The sky was blue again the next day, a day so fair to go see the opulent grass, Yet the marsh no longer shone, brackish, brown demise, drowned by its own nature,

Still each day I traveled to see it, hoping to see a speck of glow, hoping to glimpse upon those swaying sun rays in the sand, But now I wish I had waited to look upon the marsh again, For I never noticed how green the spartina grew each day.

77 MARSH

80 Travel & Culture

Out of the Golden Isles

I harken back to those dilapidated homes, Filled with the youth of a generation, attempting to crystallize moments fleeting, As I roam the chartreuse blots of marsh, like oil and water, there appears the two cranes together, soaring to display their wanderlust, as do I, In these glowing estuaries are the new lives I speak of, the ecology of convergence, Where the ebb of the tide does not erode, but create anew the Garden of the World, A home, constantly transformed but free from transformation, a native place, a time period, a sovereign, a memory, My migration is one of a natural succession of things, a rite of all those who grace themselves with the spartina grass, Be it the whales from the Arctic, or the butterflies from South America, it is to thee, dear mother of the Golden Isles, that we ceaselessly return to lose ourselves in the warm embrace, the tepid waters, the brilliant green. Now, as the sun meets the waves, as the grass points towards me, I want to grasp that salience, for I know that I cannot bring it with me, Equally knowing that I will lose myself once again, transitory for the gifts granted to the amblers, perhaps next in Appalachia, It is to you, home, wherever you are, that I hope to return.

81 MARSH

We Are an Endangered Species, You and I

We are an endangered species, you and I, We, lovers of power, devotees of performance – go away, we are told, There is hardly a place for us out here anymore, not amongst all the commuters and congestion,

Not in this growing age of safety and restraint, where practicality trumps adrenaline. The evidence is everywhere, you and I are being squeezed out, pushed aside, and hunted down,

And yet, there is hope, there is a safe haven, a place where we are free to challenge conventions, push the laws of physics and utilize our powerful and beautiful machines, It is not a monastery free from civilization, or even a field outstretched for frolicking and jubilation,

It is not even a place, but it is more than that, It is a communal celebration, Of power, of histories, of victories, of competition, of grip, of beauty, of technology, of innovation, of heat, of shouting, of community, of love, of friendship, of life, It is the last bastion of a life vital, And it is right there in the living room, mounted on the wall.

82 Travel & Culture

83 MARSH

85 CHARLESTON

CHARLESTON Travel Guide

SLIGHTLY NORTH OF BROAD RESTAURANT

192 E Bay St, Charleston, SC 29401

Slightly North of Broad Restaurant – more commonly known as SNOB – lies nestled in the hub of downtown Charleston, only a two-minute walk from the waterfront pier. On the corner of East Bay and Faber Street, SNOB has welcomed patrons from both near and far for the past three decades.

Upon entry to this Lowcountry, farm-to-table bistro, guests are greeted by the warmth of southern hospitality. Owned by the family-operated Hall Management Group, SNOB leans into that familial vibe with a colorful dining room that looks onto an open kitchen and spot for nightly live music.

“Welcoming someone into our homes, that’s the feeling that we want all of our guests to have… like they are an extension of our family,” says Analisa Muti, manager since July 2020.

Over the course of thirty years that SNOB has established itself in the Charleston dining scene, its food has remained far from static. The menu cycles through daily and seasonal specials amongst a few restaurant classics–thanks to the creativity and expertise of executive chef Russ Moore.

“Keeping SNOB relevant, keeping up to date with what’s available locally, and staying active in the community have always been super important,” Moore says.

Through his 20-year tenure at SNOB, Moore has played an instrumental role in establishing relationships with suppliers throughout the state that bring the freshest ingredients to the table. The air of comradery and collaboration within the Charleston food and beverage industry, Moore says, contributes to the never-ending menu inspiration.

At SNOB, menu development and employee development go hand in hand. The restaurant is active in the Apprenticeship Carolina program, a division of the South Carolina Technical College System that hires young and inexperienced cooks. These apprentices gain a free culinary education through

working in one of the best restaurants in Chucktown. Oftentimes, Moore runs a menu special–such as chocolate mousse or seared duck–so that apprentices can develop a new culinary skill.

“I work with these people and watch them develop into real culinarians. It’s incredibly gratifying,” Moore says.

I indulged in the creamy, seasonal butternut squash bisque to start before landing on the classic shrimp and grits for my entrée. While I’m normally neither a shrimp nor a grits person, I knew that if a dish had been on the menu for as long as I’ve been alive, then it must be good. If there is a taste that epitomizes southern hospitality, the SNOB shrimp and grits is it. And knowing the foundations of the kitchen made me appreciate the dish all the more.

Among the staff, vendors, and patrons, SNOB is a family, and eating here will make you feel right at home.

87 CHARLESTON

88 Travel & Culture

THE GRAND

BOHEMIAN GALLERY

55 Wentworth St, Charleston, SC 29401

T ucked behind the primary reception for the Grand Bohemian Hotel Charleston lies an art gallery bursting with the most special works in all of Chucktown.

Curator Kaitlin Stanton maintains the gallery, which is ever-changing yet consistently cohesive. Between local and international artists, up-and-comers and big industry names, and artwork in virtually every medium imaginable, there is truly something for everyone in this gallery.

The Grand Bohemian Gallery perfectly embodies its motto: “Leave the familiar behind.” Every visitor knows Charleston by the water, boats, and historic sites–and most of the artwork around the city mirrors exactly that.

“But you’d be so bored if all you saw was what you thought you were going to see in town,” Stanton says.

Instead of traditional nautical landscapes, the Grand Bohemian Gallery features boat sculptures made with local driftwood across the room from pixelated pastel scenes of Charleston’s most well-known landmarks.

At the Grand Bohemian Gallery, every art piece has a

story behind it. Taylor Redler of Visceral Homes honors her past through her art of acrylic, cement, charcoal, and plaster, which brings in donations for substance abuse and mental health disorders. From an anonymous Iranian artist, abstract portraits of women blur out only their faces, the one part of their bodies their government allows them to show. This artist sells to a Miami art dealer at risk of being caught for a chance to be seen.

Stanton knows her inventory inside and out, and her passing along these stories makes you appreciate the spectacular art so much more.

“My goal for the gallery is to make sure that every person who walks in this space can find something that makes them happy and changes their day,” Stanton says.

For some, that means simply perusing the gallery to let their mind drift from the bustling nature of downtown Charleston. For others, that means making a purchase and taking some magic from the Grand Bohemian Gallery to a new home. An open spot on the wall or a small orange sticker below a big painting signals that more art will cycle through the gallery for visitors to see.

89 CHARLESTON

FORTE

JAZZ LOUNGE

477 King St, Charleston, SC 29403

On King Street, Charleston’s hotspot for food, night life, and shopping, Forte Jazz Lounge fits right in. Opened in 2019, Forte stands as the perfect combination of the big sound of New York City jazz clubs and the comfort of southern hospitality. Husband and wife Joe and Rosie Clark run the venue, with the help of their kids, to bring Chuckdown a place for music that the city didn’t know it was missing.

Having always lived in Charleston playing a myriad of instruments, Joe Clark naturally found himself in the city’s music scene as an adult. Clark has both taught and performed his craft, while developing a network of like-minded artists. Clark has since shifted his career to running Forte, he has musicians that come from near and far to perform.

“Every musician has their forte – the thing they do better than anybody else – and we wanted to create an environment where they could come and be heard,” Clark said.

And, that is exactly what the Clarks have done.

Past the lobby and wine bar is the comfortable yet luxe seating area for 120 listeners. Couches toward the front, candle-lit tables behind those, and bar seating on the sides, there is not a bad seat in the house. Blue and green lights illuminate the stage with a grand piano and ample space for performers. The ambience is warm and inviting with the foundations for a lively night of music.

A grand mural covers the wall to the right of the stage, with portraits of ten of history’s greatest jazz

musicians, including Louis Armstrong, Aretha Franklin, and Frank Sinatra. Many performers that come through Forte Jazz Lounge channel inspiration from these icons in their acts, bringing a unique, modern flair to the classics that many know and love.

“You can’t have jazz without Hispanic, African, and European influences coming together and creating something completely new,” Clark says.

The performances at Forte flourish because of this beautiful mélange of cultures, time periods, and genre adjacencies. They connect a diverse audience that would not have come together otherwise by way of a common sound and a shared experience.

Any concertgoer understands the magic of live music that headphones cannot translate. The Clarks at Forte Jazz Lounge prioritize making live music more accessible for both locals and those traveling through Charleston, in an effort to uphold their mission of exposing more people to the wonders of jazz.

“Most people yearn for this environment. They may not know that they need it. The kind of environment we’ve built at Forte is essential for human connection,” Clark says.

Perfect for a date night, special occasion, or fun night on the town, Forte Jazz Lounge provides an exceptional small concert experience in the premier listening room in downtown Charleston.

90 Travel & Culture

91 CHARLESTON

JOE RILEY

WATERFRONT PARK

Vendue Range, Concord St, Charleston, SC 29401

People are not lying when they say Charleston has it all: from vibrant city life to centuries of rich history, arguably the best cuisine of the southeast, bustling art scene, closeness to the water, and calm nature sights not too far away. It’s easy to get overwhelmed with all that the city has to offer, but Joe Riley Waterfront Park offers a much-needed pocket of peace with beautiful views.

Located along half a mile of the Cooper River bank in downtown Charleston, Joe Riley Park includes bits of history in the concrete benches and plaques throughout this sunny, twelve-acre oasis.

What was once a center of maritime traffic for the oldest city in South Carolina has served as an open-air space for relaxing tourists and local dog walkers since the spring of 1990.

On November 24, 2015, this park became a namesake for Joe Riley, Mayor of Charleston from 1975-2015. The end of his four-decade tenure spent building up the human spirit within the city and the surrounding natural environment marked the perfect opportunity to establish his legacy.

The famous pineapple fountain is a landmark photo spot halfway down the park’s stretch, and the adjacent boardwalk welcomes a comforting sea breeze. Overlooking the main length of the park is a brick walkway lined with garden benches, shaded by tall oak trees and Spanish moss dangling in the slivers of sunlight. The park stands as one of the best places to view the sunrise and sunset in Charleston, with watercolor skies mirroring over the calm river.

One of the benches reads, “Parks make our cities beautiful, soften the hard edges of urban life, invigorate us, and give us peace and repose.” And the Joe Riley Waterfront Park does exactly that for the city of Charleston.

PHOTOGRAPHY & WRITING Anna Rebello

93 CHARLESTON

94 FORM

Style

95 FORM

Style

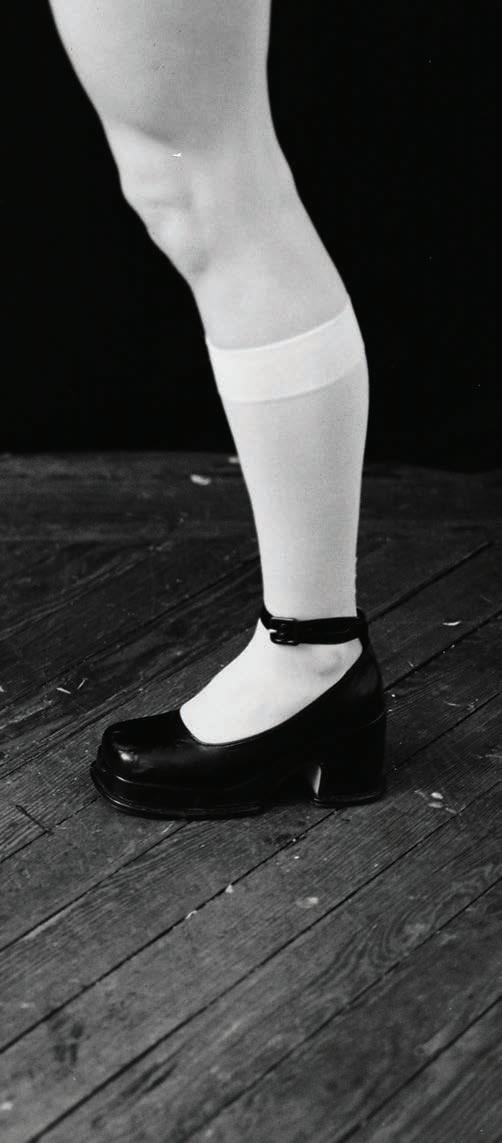

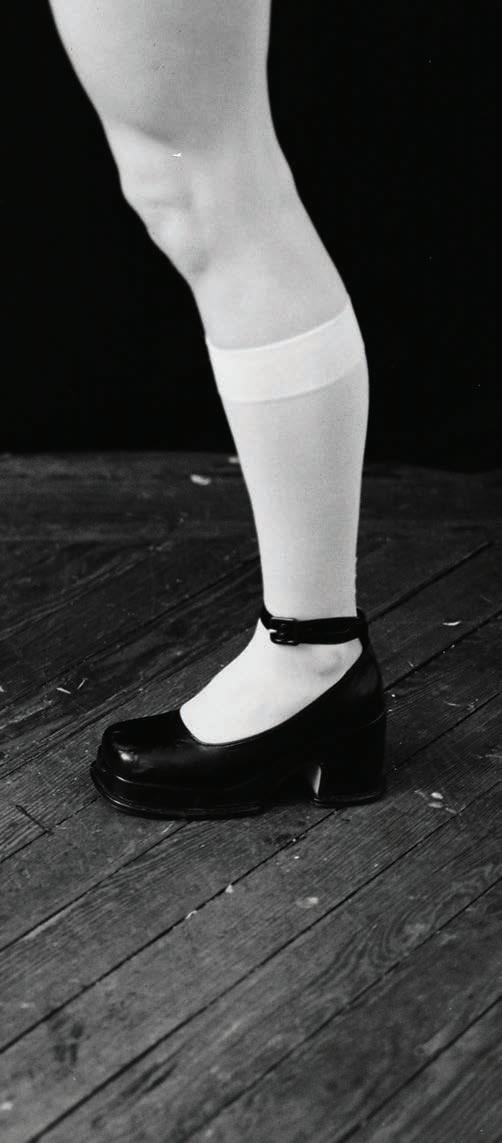

in the vernacular

Clothing is part of the cultural dialogue with which we are forced to engage. To be entirely flat-footed, it is our outermost layer. That isn’t to say it is our most shallow layer, but it is certainly the most forward-facing. Clothing, then, makes sense as a medium to examine the interplay between how we understand our projection of the self, and how we demonstrate it to others. It is language that is implicit, as it is observed rather than imposed. Clothing is curated, but it is still intuitive, expressive, and radically personal like any other form of communication.

Ordinary language philosophy tells us that language does exactly what it says it does. In a world constantly looking to critique, uncover, and dig beneath the surface, this framework reminds us to take what our language does at face value. Calling the concept of ordinary language a philosophy is misleading; ordinary language philosophy really tells us to stop philosophizing and reminds us that there are types of thinking other than that which is critical.

99 IN THE VERNACULAR

100 Style

Clothing is both projective and observed. In its creative existence, it does something simple. It lets us tell people how we hope to be perceived, and with that, how we perceive ourselves. There is an interpretive level at play, as well as some optionality. A clothing choice can be made as an expression, a projection, or both. Aligning both is not necessarily smooth, though. How we hope to be perceived for the sake of professionality, conformity, lack thereof, or any number of personal factors has to actively be aligned with how we perceive ourselves. That process is not only difficult, but it anticipates incompleteness; there are always external factors that call for mediation between understanding and projecting the self. However, the process of defining and developing that perfect harmony is exciting.

To go back to framing this process alongside language, clothing lets us implicitly tell people what we want that balance of projection and expression to look like. It also lets us iterate quickly in a way that traditional language does not. With clothing, we can say we see ourselves one way, say we are interested in one thing, and then, slowly tweak it to more truly line up with our internality. It is fast, constant, expansive, and of course, creative and expressive. It speaks through its existence, its fabric, its color, its silhouette; it is taken at face value. This isn’t to say that there are no deeper, philosophical, or critical concerns surrounding clothing, but just that this framework of treating clothing as ordinary language works.

103 IN THE VERNACULAR

FORM chose models for this shoot in pairs of close friends. They first styled each other in the way that best aligned with their perception of the other’s personal style. Each then styled themself in the way that best fit their own personal expression. The balance of harmony and dissonance between the outfits styled for them and the outfits they themselves styled made for an exciting conversation. They loved those fun pants, but they’d probably pair them with something a bit more comfortable or a bit brighter in color. Really, though, they’d rather wear the skirt from their mom’s early adulthood adventures around the world, or the shirt from their favorite sports club or the jacket they’d thrifted with their closest friend in their favorite city.

It became clear that within the expressive element of clothing sits the stories that accompany it. There is, then, a level of personal attachment to this dialogue, like any other, that goes beyond what is perceived. In that sense, our approach falls short; it is not enough to talk about what this clothing does in being seen and worn, without talking about its entire lifecycle and the memories attached to it. What we did see was how an expressive personal style could both translate, being understood by friends to represent the person’s sense of self, but also be more personal than interpersonal, meaning more for selfexpression and understanding than it ever could externally.

106 Style

This layer of expression is not without its faults, like any other. As language, it has the capacity to be misinterpreted, and even misrepresentative or misleading. Moreover, clothing as communication can be shallow, wasteful, and prejudiced in a host of ways. Those considerations are implicit in the intuitive transmission of information via clothing. Still, with an ordinary approach to clothing, we can make sense of what it does and lets us do implicitly. We can lean into using this form of expression that is essential and diversified, to better align our expressions and our projections of self.

PHOTOGRAPHY Jackson Muraika

WRITING Ali Rothberg

MODELS Michaela Harris, Abhinav Jain, Katie Lam & Ayushi Patel

110 Style

the processes for curating clothing and curating music as

112 Style

Colbo NYC

Colbo NYC is a multidisciplinary retail space in The Lower East Side, New York founded in Fall 2021. It’s the latest project for co-founder Tal Silberstein, who oversees creative direction in addition to designing Colbo’s in-house clothing line. Silberstein spoke with FORM about drawing inspiration across fashion, art, and music, and what lies ahead for the brand.

113 COLBO NYC

Jackson Muraika: Colbo is a multidimensional space— there’s a lot going on in terms of coffee and clothes and art, and more—but it all feels very cohesive. What was the vision behind bringing these different aspects of the store together?