4 minute read

When a Different Pandemic Disrupted Campus

In 1918 and 1920, influenza temporarily changed Trinity College.

READY FOR ACTION: The Student Army Training Corps

Advertisement

BY VALERIE GILLISPIE

Duke’s spring semester is unlike any that came before it. Students are largely absent from campus, classes are online, and spring traditions—even commencement itself—are canceled or postponed. As we feel the impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, it’s helpful to look back at how the campus weathered a global influenza epidemic that struck 100 years ago, coinciding with the end of World War I.

In 1918, Trinity College had yet to become Duke University. The school, located on today’s East Campus, had fewer than 500 students. In the fall of 1918, the majority of the male students enlisted in the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) at Trinity. The SATC was a program under the United States War Department to enlist currently enrolled students and provide them with training. Trinity was just one of hundreds of colleges and universities that hosted such programs.

The SATC radically changed life on the Trinity campus. Those enrolled in the program were no longer freshmen or seniors—instead they were divided into sections based on age. Fraternities, literary societies, and campus publications were largely on hiatus. No Chanticleer was published in 1918, and the first issue of The Chronicle during the 1918-19 school year was not published until November, following the armistice that ended the war.

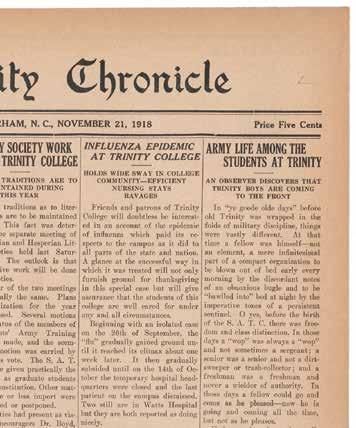

As the SATC became ascendant, a global influenza pandemic emerged. It reached Durham and Trinity in September 1918, and over 200 students and several faculty members contracted the flu. In the November 21 issue of TheChronicle, the course of the epidemic was detailed. Of particular interest is the way the students were triaged if showing symptoms:

An example of the way the work was done, as soon as a boy was reported sick, he was at once looked after. “Thermometer squads” were formed who went to every patient twice a day and took his temperature and made a record of it. Mild cases were simply dosed with such medicines as seemed necessary and the proper diet furnished. Cases of a more serious nature were placed in the hands of trained nurses. Even more serious cases were placed under the care of a physician. In this way the strength of the doctors and nurses was conserved and used to the greatest advantage possible.

The school was proud that not a single student died of influenza that season. By November, with the war and the worst of the flu over, attention could return to studies. In response to students pleading to cancel final exams, the faculty met in what The Chronicle described as “that mysterious and secret council known as ‘Faculty Meeting.’ ” Following it, the faculty announced that students would receive credit, but no examinations would be held until March. The Chronicle breathlessly reported that “After the reading of the above resolutions, the eye of every student on campus has beamed with new lustre, and every heart has throbbed with more delight in its longings for the joys of the Christmas holidays.”

Sadly, a student, J.W. Neal, did succumb to flu-related complications in April 1919. His decline was quick, and he lived for only a few days after the symptoms began. TheChronicle reported, “His mother arrived in Durham yesterday morning in time to be at the bedside of her son before he died, but he never regained consciousness after her arrival.” The impact of influenza can also be seen in the Alumni Registers (predecessor of Duke Magazine) of 1919 and 1920, with notices of alumni deaths scattered throughout.

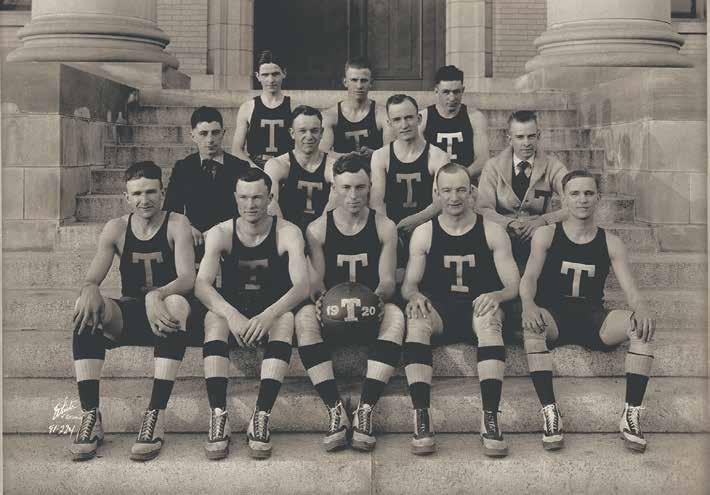

A second wave of influenza struck North Carolina in February 1920. In early February, the basketball team had to cancel a game in Raleigh, “on account of the seriousness of the epidemic of influenza in that city.” Soon after, on Valentine’s Day, students entered “voluntary quarantine.” Under a headline that boasted “Influenza Situation on Campus Excellent,” The Chronicle reported:

GAME OFF: The 1920 basketball team had a game in Raleigh canceled.

Upon the advice of Dr. Joseph Speed, advising physician for the college as a whole, the students were requested to go into voluntary quarantine Saturday. By this request the authorities asked the students to refrain from going down town except on pressing business, and when doing so to sign out on the book at the office.

The reason for this precaution is to avoid bringing the epidemic, which is raging to a considerable degree in the city of Durham, into the college. Places of amusement in the city have been closed for some time, and the public schools were closed a few days ago. Congregating in drug stores, cigar stores, and street corners is warned against. Street cars are prohibited from receiving passengers in the excess of the normal seating capacity. Thus far students have been exceedingly wise and prudent in the observance of the precautions recommended by the authorities, and if they will but “carry on” as they have been doing, there is no reason why Trinity College should not get past the epidemic without suffering noticeably.

As in 2020, athletics were canceled during the quarantine in 1920. It was lamented that there wouldn’t be an end to the season, but happily contests were restarted in late February. Trinity College took home the state championship in men’s basketball that year, a bright spot during a troubling time.

Although the spring of 2020 has been disruptive and unsettling, perhaps we can find some comfort in looking at our past, and seeing that we have come through disruptive and unsettling times before. We’ll come through this one as well, making our own history as we do it.

Gillispie is the university archivist.