168 minute read

THEQuad

from WINTER 2020

by DukeMagazine

DEMOCRACY

IN ACTION: The Karsh Alumni and Visitors Center was turned into an early-voting site, attracting a record-breaking 12,694 voters casting ballots. Photo by Megan Mendenhall THEQuad LIFE ON CAMPUS FROM EAST TO WEST

Advertisement

They C You Walking with the team that reminds students of the COVID-era social rules

ON A BRIGHT AFTERNOON guidelines: two students to a glider, that’s the point. When the decision early in the fall term, as- keep that distance, “and if you’re done was made to open campus for the fall sociate dean of students eating,” says team member Jim Hodg- term, Powell says, faculty raised “a lot Amy Powell is taking a es, director of conference and event of questions about adult presence.” So walk through a West Campus residen- services, “mask up.” There are shifts all being the nosey middle-school teacher tial courtyard, and she sees three guys day, from morning till midnight, with has its benefits. In general, “I have been sharing one of the tables under a shel- a pair walking each campus. super impressed” at students’ cooperater for lunch. The team is just an extension of the tion, says Powell. “Even at night, when

“Hey, friends?” she calls. “If you’re policies of Duke United, the universi- there are bigger crowds, they’re weardone eating, can I ask you to put your ty coronavirus response that includes ing masks.” And if they’re a little closer masks back on?” Three masks go back mask requirements, contact tracing, than they should be? “That’s when we on. There is at least a hint of eye-roll- and required testing both before stu- have to intervene a little more.” ing, to be sure, but overall the guys dents arrived and regularly once on It’s not just frowny faces, though. just go along, doing what they know Sometimes when C-Team members they’re supposed to do. see people wearing masks and appro-

Part of the reason they priately distancing, they know is the C-Team, which is why Powell “We know how distribute coupons for the library’s Perk or is patrolling. That’s C as in compliance: you feel about it, the Trinity Café on East Campus. They compliance with all but we’re here to also share thank-you the rules and principles Duke has adopted make sure you cards: “We see you!” the cards say. “THANK in its effort to keep the campus open and as free of COVID-19 as stay here.” YOU for doing your part to keep the Duke Community safe.” possible. (Or maybe it’s C for caring, The team gets calls on occasion. or COVID, or just because there’s al- One R.A. called the team, concerned ready an A-Team for bonfires and a about a video-game tournament in a B-Team for protests; anyhow, C it is.) campus. Says Hodges, “Duke has dorm lounge; when the team arrived

Duke’s success in opening its cam- chosen to take the path that’s hard.” to check, all were keeping their dispus has not come without planning, Which means a lot of walking. tance and had masks on, so no worsay Powell and other team members. If you’re of a certain age, it’s impos- ries—just a walk across campus for With significant spread showing up at sible to see Powell or other C-Team the C-Team. “I’m certainly getting my North Carolina’s public universities, members walking campus and scop- steps in,” Powell says. Students comstaff and faculty recognized that many ing out students without thinking of plain a bit, of course, but they comstudents are, after all, late teens and Miss Grundy from the Archie comics, plain about all the sterner measures. would be more likely to succeed with floating around a dance in the gym, With the library requiring assigned some gentle supervision. frowning, making sure the kids don’t seats and book reservations, students

The C-team provides that gentle get involved in any of that dangerous have said the security feels like Fort supervision in the form of teams of hug dancing. Knox. Powell is fine with that. staff volunteers, mostly from student “You embrace it,” she says of the “If it’s Fort Knox,” she says, “they’re services. They walk East and West Miss Grundy role, laughing. “We know all right.”—Scott Huler Campus in pairs, looking for students how you feel about it, but we’re here not following Duke’s coronavirus to make sure you stay here.” In fact,

DUKE’S AGGRESSIVE COVID-19 surveillance and testing effort was highly effective in minimizing the spread of the disease among students. That’s the finding in a case study released by the Centers for Disease Control in mid-November.

Ahead of arriving on campus, students were required to self-quarantine for fourteen days, sign a code-of-conduct pledge to obey mask-wearing and social-distancing guidelines, and have a COVID test.

Once classes started, the university conducted regular surveillance testing using pooled samples, meaning those samples were batched together; the batches could be broken into individual samples and tested separately to

THIS C IS FOR C O N T A I N M E N T

identify the source of a positive finding. Students conducted twice-weekly tests themselves (at least once a week for those off campus), returned the samples to campus sites, and performed daily symptom self-monitoring through a Duke-developed smartphone app. If they were symptomatic or had been exposed to someone with the coronavirus, the university’s contact-tracers went to work, and those students were temporarily quarantined.

Between August and October, the Duke Human Vaccine Institute processed 80,000 samples. The result: Among students, the average per-capita infection prevalence was lower than in the surrounding community, and Duke avoided the large outbreaks seen on other campuses. Overall, the pooled testing identified eightyfour student cases, with 51 percent asymptomatic—that is, showing no symptoms but infected just the same. n

X

XX.

DR/TL*

Brief mentions of things going on among Duke researchers, scholars, and other enterprises

ANIMALS AND MICROBES

Turns out it actually is not easy being green—it’s not a simple matter of PIGMENTATION. Some frogs are green not because of skin pigmentation but because they hijack a bile pigment. Whatever works, frogs. ➔ If predators can’t see you, they can’t eat you. So fish who live in the inky blackness of deep ocean have evolved ultra-black skin that keeps them from reflecting even a tiny bit of light by evolving pigment packets called MELANOSOMES, which trap light. ➔ A mutation in the spines of research-workhorse zebrafish makes them look like fossil spines, giving insights into spinal evolution. ➔ Birds may make all that racket in the morning as a sort of warmup. SONGBIRDS noisier in the morning were better singers later in the day. ➔ Malaria parasites use a combination of liquid proteins to protect themselves from the fever a body runs as it fights them. This understanding may help scientists figure out new ways to fight MALARIA. ➔ Platonic friendships among male and female BABOONS seem to yield longer lives for the male baboons; the females groom them, whereas males do not groom one another. ➔ Young DOLPHINS pick friends carefully, too: As they move from pod to pod, they keep up with their besties. It’s like networking. ➔ One way to avoid the next pandemic? Reduce WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING and forest loss. The more that separates people and wildlife, the less likely diseases are to spread from them to us.

PEOPLE

North Carolina county ELECTIONS OFFICIALS do not appear to have changed polling places for partisan advantage. ➔ A new BLOOD ASSAY can identify the body’s response to various viruses before symptoms appear, improving treatment, quarantine decisions, and public-health interventions. ➔ Progressive churches have become more politically active during the Trump era, to the point where they are now likely more active than conservative CONGREGATIONS. ➔ TEXTING PARENTS has long proven helpful for kids in early-learning programs. The simple enhancement of automatically enrolling parents in (and allowing them to opt out of, instead of requiring them to sign up for) texting programs yields significant improvements in the children’s development. ➔ Two-thirds of food options near the ten HBCUs in North Carolina are rated “unfavorable.”

MISCELLANY

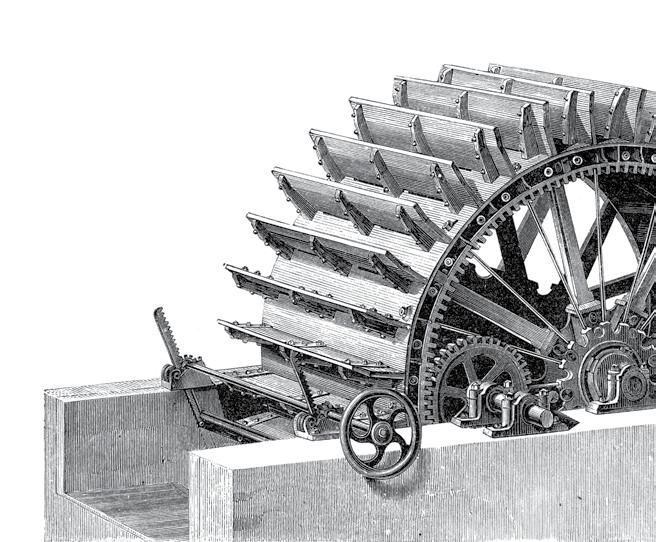

The way cells derive ENERGY FROM RESPIRATION involves positive-charged protons crossing a membrane while two negatively charged electrons bifurcate: go in different directions, undergoing different processes. This is something like a water wheel, where the electrons behave like water, the wheel turning one electron into energy, which it uses to lift the other back to a higher-energy state. People have been wondering about this for a long time, and now you know. ➔ An artificial-intelligence program was able to take highly pixelated images and turn them into extremely realistic, detailed imaginary faces. ➔ Diminishing GROUNDWATER supplies are eating into Midwest grain yields. Uh-oh.

DUKE

In April 2020, Duke launched a research program called COMMUNITY HEALTH WATCH, which provides symptom support and guidance, in both English and Spanish, for people caring for themselves at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. In its first six weeks, the program provided support to more than 1,500 people. The Duke team reached out to other organizations providing help and created the nationwide Pandemic Response Network. ➔ Duke received a $5 million grant to lead a five-year program creating a new national center to develop wireless communications and networking protocols fast, reliable, and resilient enough for use by the U.S. AIR FORCE. ➔ Duke researchers found a way to make VENTILATORS safer and more efficient when splitting them between patients. ➔ To sustain students through the exceptionally long semester break this year, Duke has designed WINTER BREAKAWAY, a cluster of two-week online programs in early January that will encourage students to step outside their usual areas of study. ➔ Duke has received a $16 million grant from THE DUKE ENDOWMENT in support of efforts to increase faculty diversity and campus inclusion, supporting the university’s Diversity, Inclusion, and Anti-Racism Initiative. n

Go to dukemagazine.duke.edu for links to further details and original papers.

Not just a game

In this course, students at play is a path to sociocultural understanding.

In the spring of 2020, JaBria Bishop built her first video game.

It was a 2D side-scroller—think Super Mario Brothers—which she believes she called Lunar Dreamscape. In it, a little girl wakes up in a lost world. Bishop’s idea for this whimsical game was for the players, too, to feel lost, so she designed it accordingly.

“I wanted the player to also feel how the little girl feels,” she says.

Bishop—today a senior; then a junior—was a student in Asian and Middle Eastern Studies department chair Shai Ginsburg and professor Leo

Ching’s “Games and Culture” course. Her project communicated one of the class’s key takeaways:

The mechanics of a game (how the controls work; how the character interacts with its world; what the player can and can’t do) serve the same function as, say, meter in poetry or key and tempo in music. She had learned to view games analytically and understand the emotional and conceptual underpinning of something as seemingly innocuous as a video-game character’s abilities.

Indeed, gaming permeates the lives of the middle and upper classes globally, Ginsberg says, but the meaning, the function of our video and tabletop gaming habits is rarely addressed in depth. In short, play isn’t taken seriously. The

European Protestant conceit, Ginsburg continues, maintains that work and play are a binary, yet he and Ching reject this dichotomy. “Games and

Culture” parses gaming with the same rigor with which one would study literature or film. It’s also structured like a role-playing game (RPG), with the syllabus outlining multiple “quests” rather than a single, shared set of assignments.

Coursework, too, involves playing a lot of video and board games.

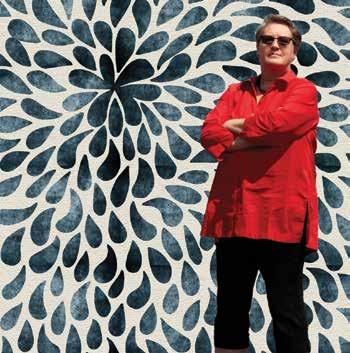

GAMER: Leo Ching

In Ginsburg and Ching’s course, the subject is the method.

“We hear a lot of professors talk about these alternative ways of pedagogy and blah blah blah, but oftentimes, those are done in an abstract way,” says Ching (whose first favorite video game was Space Invaders). “For us, playing board games with the student actually concretizes some of this sense of equality.”

Indeed, when the dice are out, when the pieces are on the board, and when the cards are dealt,

there are no instructors and students—just players. Ginsburg (who loved Legos from an early age) compares it to siblings playing together: The age difference disappears. Especially when the class plays a new-to-everyone game together, all are novices and there’s a momentary suspension of the teacher-student hierarchy. This is by design.

The course is just like a game, says Ching. “Sometimes when you play it, a game is designed in such a way that at least gives you a sense of agency, even though you might not have it. You feel like you’re doing something because the game allows that interactivity.”

Ching grew up in Japan and Taiwan, where the education system privileged rote learning. After that upbringing, he found the participation and discussion within American education particularly stimulating. Yet he and Ginsburg believe students can be offered yet more active roles in their schooling; that the teacher-student hierarchy can

INTERACTIVE:

In the “Games and Culture” course, students explore the social context of games like “Rap Godz.” be at least paused, allowing students to co-create the course.

“It’s like if we talk about community theater,” Ching offers.

In the course he, Ginsburg, and each semester’s students co-create, their play includes an unpacking of games’ social context and subtext. Some of this is overt, such as gaming’s troubling history of representation. Statistically, Ginsburg says, you’re more likely to see a sheep on a game box than a woman, while nonwhite and LGBTQ characters are even rarer. Ching and Ginsburg include modern games that consciously buck this trend, such as Omari Akil’s Rap Godz.

As a Black man, Akil is rare among board or video-game designers. Accordingly, representation is expressed through mechanics, too. Most game designers are white males and most game characters are white American males, Ginsburg says. They’re aggressive and assertive, and gameplay is defined by competition, conflict, and the pursuit of a goal. The feminist critique, Ching says, holds that this is a heteronormative, masculine game design.

“This seemingly very democratic, open-ended, fun space” is actually informed by a chauvinistic white privilege “that we have to undo,” adds Ginsburg. “We have to unpack this facade of inclusion and fun.”

It’s heavy conceptual lifting, implying deep philosophical questions. What, Ginsburg wonders, does game design communicate to an international audience about American culture? About Korean culture? About Japanese culture? And would, Ching wonders, broader representation in game design result in different definitions of game? In games with no goal? In collaborative games?

In their course, such lofty hypotheticals and sociocultural analyses are explored through play.

—Corbie Hill

Q&A

John Aldrich, who specializes in American politics and behavior, is Pfizer-Pratt University Professor of political science, a former president of the American Political Science Association, and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The common view is that high turnout favors Democrats. With the recent election, has that assumption been forever overturned?

There’s a Democratic advantage in that more in the electorate favor [that] party. Even so, Democrats draw disproportionately from those who vote at lower than typical rates, such as minorities, the disadvantaged, and the young. But the Democrats have been building support among the college-educated, who are among the most likely to vote. Over a decade or so, the Republicans have built increasing support among rural whites and others. Those groups also are somewhat less likely to vote. That historical reality helps explain Trump’s focus on energizing his base, which is all about moving traditional non-

Shaun King voters into becoming voters.

Thus, the balance between the two parties in turnout is evening out; this was especially evident in 2016 and 2020. However, I would say that nothing in electoral politics is forever. If trends continue, the Democrats once again might become the party with higher expected turnout.

Is one takeaway from the election that voters now resist crossing party lines as they consider candidates for office?

This election looks like a very strong affirmation of party-line voting. It was not just Trump who outperformed expectations; it was Republican candidates for the Senate, House, and state legislatures, up and down the ballot. The thickening and deepening of the partisan divide has been under way for a long time now, and each election extends that partisan cleavage more. Many call this the rise of identity politics, but it is even more than that. It is identity politics reinforced by issues, ideologies, and values, and it is further reinforced by the tendency of everyone to interact with fellow partisans and especially media in their echo-chamber bubbles of (mis-)information.

Have the Democratic and Republican brands changed over time, maybe in terms of whom they appeal to or the values they stand for?

One of the critical questions for political scientists and political historians alike is to understand when and how such changes occur and with what consequences. While this is a continuing process, the modern Republican Party emerges out of the breakdown of the one-party South, starting under President Reagan and reaching a point of

real success in 1994: Not only did Republicans break the forty-year hold of the Democrats on the House majority, but they also won a majority of House seats in the South for the first time and chose a heavily Southern leadership, led by Speaker [Newt] Gingrich. This transformed the party of Lincoln, which relied exclusively on Northern votes, to one that had a strong base in the South—and among white Southerners, in particular.

Trump’s inability to condemn white supremacy is one legacy. There are many other aspects of deep and important changes. Trump appears to true for lots of races, not just the presidency. It may very well be that they did not miss by more than a reasonable margin of error, but that it was pervasive is worrying.

I would start by understanding that doing high-quality polling is getting more difficult—and therefore more expensive—year after year. One possibility is to have major media form a consortium, as they do already for the exit polls, and allocate the resources to get a common set of high-quality polls of the nation and of key states, if not all states.

One challenge is to get the best possible snapshot of the electorate,

Lots of money flowed into the campaign, including downballot races. Is there reason to question the importance of money in contributing to victory?

Money—actually the things that money can buy—is necessary for an effective campaign in anything like a competitive environment. It is not sufficient. You have to have something to say that resonates with the people whose support you are pursuing. That has long been the advantage of the incumbent: a known quantity with access to resources and something to say about what she or he worked on

have weakened if not broken the Republican commitment to free-market principles and small deficits. But who knows if that will continue? Democrats have become the party that embraces a commitment to the environment, a set of principles that was at least shared if not more strongly held by Republicans at the start of the twentieth century. Democrats were the pro-life party, Republicans the pro-choice party, until around 1980. Everything changes. What matters is how and when.

Again the polls seemed to miss the mark. How would you reform political polling?

While there is much work to be done to understand polling’s successes and failures, it seems clear that they did not lead us to expect how close 2020 was going to be. And this appears to be since each poll is but a snapshot of a single moment in time, and that is what inspires the thought of a consortium of some sort. These are designed to actually include in the poll the full set of people. A second challenge is to worry about whether people are reporting their attitudes and choices accurately. We’ve been hearing for two election cycles about the possibility of “shy” Trump voters. I suspect there are very few of them—and if there are any, they are likely shy not just about their support for Trump but for other candidates, too. But there is so much other relevant information out there, in social media and in other public forums, that the future seems, to me, a combining of all kinds of “big data” with polling data to reach better conclusions. since the last election. Challengers need money to compete against those advantages. But this time, there was so much money floating around that campaigns seemed to be looking for some way to be able to spend it all!

How did you do your own voting? Did you vote early in person, vote by mail, or vote on Election Day?

My wife and I filled out mail ballots, but I decided to take them to the Duke early-voting site for hand delivery. It was easy; there was no one else voting or doing handdelivery of ballots when I went there. And the ability to interact with poll workers doing what turned out to be such a wonderful job in support of the community was heartwarming.

—Robert J. Bliwise

T R U T H T R U T H

Masking the truth A study goes viral for all the wrong reasons.

EVERYONE LOSES TIME to COVID-19. sure they worked. Sending them to a lab would be Martin Fischer lost most of a month to expensive and slow and might not even really measure masks. them under real-world conditions. So Westman sent

“I’m not getting anything done oth- an e-mail asking for help to the physics department. er than this,” says Fischer, associate It ended up with Fischer and his optics techniques. research professor in the department of chemistry. Fischer had seen scientists at the National Insti-

“The last three weeks have been this, 100 percent.” tutes of Health use a method of widening a laser

By “this” he meant media availabilities, Zoom inter- beam vertically into a sort of sheet of light; through a views, and various other responses to his attempt to computer algorithm, they could then count droplets help out as masks spread through the culture. in the air as they passed through. A subject spoke

Surprise, “especially since my usual line of work is through a mask into a special box with no air curnot really involved in topics that get a lot of media rents. Fischer followed the method and built a quick attention.” Fischer works in optics, developing tech- and cheap mechanism to do the same. To compare niques in microscopy in fields like materials science the mask Westman was interested in, Fischer exand biomedical materials. Then came COVID-19, panded the idea, using whatever masks happened to and he helped out a colleague. be lying around.

Eric Westman, associate professor of medicine, was Don’t think about a big complex setup, he points working with other physicians on a project called out. He had to get permission from the dean to come

Covering the Triangle that, in the early days of the on campus to do the work; his daughter, a Duke stupandemic, helped sew, acquire, and distribute masks dent, functioned as his assistant because they lived in to people in the Triangle who needed them. Westman the same house and so transmission wasn’t an issue. had a line on some masks he could buy in bulk, Fisch- It was a kind of spare-time project. “This project is er says, but at that point getting masks was a some- unfunded,” he said. what dodgy business, and Westman wanted to make They tested fourteen mask types, with one per-

T R

T H U TRR T U UH

son talking through the mask and the other using the camera. mask types under all droplets than no mask at all. Reporters got excited, and stories about some masks And again: The point was the method, and sharing it so others could quickly test masks hither conditions. But we being worse than nothing at all spread, were criticized, were responded to, were amended. And always with more phone and yon. “This was not a largescale systematic study of all mask types under all conditions,” developed a very simple calls to Fischer. Mind you, Fischer points out, the study made no claims about the effects of Fischer says. “But we developed a very simple method of visualizing the effects of a mask.” method of visualizing the more or fewer droplets, the viral load per particle, or anything like that. This was a quick proof-of-principle test, and it The data looked worthy, so he and his colleagues thought this easy and cheap method of mask effects of a mask.” worked. As science, it was something of a counterexample to his daughter, who got her first publication out of it. “I did remeasurement should spread. “It’s peatedly tell her, don’t think this is usual super easy to set up. Let’s hope science,” he says of the study, which took people pick this up and do their own demonstrations a couple of weeks of research and was printed a couand quick checks,” Fischer said. “This was never in- ple of months later. “Usual science works differently. tended to be a certification or an endorsement of any How often do you go into a lab and a couple days of kind of mask.” data-taking you have a paper that has a million-and-

Tell that to the media. The study came out. Then a-half views?” came dozens of stories, mostly focusing on the fact That’s a lot of views; it’s spreading quickly. Spreadthat according to the study’s measurements, one ing almost like a…almost like something. mask—a thin neck gaiter—actually resulted in more —Scott Huler

WE ASKED

Marjoleine Kars ’82, Ph.D. ’94, an associate professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and author of Blood on the River: A Chronicle of Mutiny and Freedom on the Wild Coast (The New Press), about how she found this untold story and what compelled her to write about it.

early praise for blood on the river “A masterpiece. . . . Marjoleine Kars has unearthed a little-known rebellion in the Dutch colony of Berbice and rendered its story with insight, empathy, and wisdom. You’ll find no easy platitudes herein. Instead, you’ll find human beings in full relief, acting with courage, kindness, calculation, and mendacity in their quest for selfdetermination. Blood on the River is a story for the ages.” —Elizabeth Fenn, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Encounters at the Heart of the World “Takes readers on a moving journey deep into a colonial heart of darkness. Drawing on rich and challenging sources, Marjoleine Kars reveals enslaved people making a rebellion that lingers in memory and landscape.” —Alan Taylor, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Internal Enemy and William Cooper’s Town “ is riveting story offers a close look at the inner dynamics of a slave war— its fraught alliances and antagonisms, strategies and tactics, and the grievances and aspirations of its combatants and resistors.” —Vincent Brown, author of Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War “One of the great slave revolts in modern history has at last found a gifted historian to tell its epic tale. Using a breathtaking archival discovery to make the Berbice rebels vivid flesh-and-blood actors, Marjoleine Kars deeply enriches the global scholarship on the history of slavery and resistance.” —Marcus Rediker, author of The Amistad Rebellion “Vivid. . . . e aborted attempt at freedom she chronicles provides a harrowing counterpoint to the American and marjoleine kars is an associate professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. A noted historian of slavery, she is the author of Breaking Loose Together. She lives in Washington, DC.Sifting through documents in the Dutch National Archives, I hit gold. A little-known but massive slave rebellion had oc French revolutions that would soon follow.” —Russell Shorto, author of The Island at the Center of the Worldwww.thenewpress.com Jacket image: map of the Berbice River and plantations curred in 1763-64 in Dutch Berbice, in the chartered colony of Berbice, by Jan Daniël Knapp (1742), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Jacket design by Emily Mahon Author photograph by Tim Ford, UMBC now Guyana. The archives held boxes of material about the conflict that played out in this impenetrable land of savannas and subtropical rainforests crisscrossed by rivers. While most slave rebellions were suppressed in a matter of days, this one lasted more than a year.

Blood on the River

KARS MARJOLEINE

the untold story of the berbice slave rebellion Blood on the River

A Chronicle of Mutiny and Freedom on the Wild Coast

MARJOLEINE KARS

HISTORY $27.99 U.S.

“Marjoleine Kars has brought from the archives the voices of the enslaved, both in hope and in defeat. A tale of importance for our time.” —Natalie Zemon Davis, author of Trickster Travels and The Return of Martin Guerre

ON SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 1763, thousands of slaves in the Dutch colony of Berbice—in present-day Guyana— launched a massive rebellion that came amaz-900 defeated freedom seekers. Here was ingly close to succeeding. Surrounded by jungle and savannah, the revolutionaries (many of them African-born) and Europeans struck and parried for an entire year. In the end, the Dutch prevailed a story that had to be told.because of one unique advantage—their ability to get soldiers and supplies from neighboring colonies and from Europe. Blood on the River is the explosive story of this little-known revolution, one that almost changed the face of the Americas.It was a topsy-turvy world of shifting

Drawing on nine hundred interrogation transcripts collected by the Dutch when the Berbice rebellion finally collapsed, and which were subsequently buried in Dutch archives, historian alliances. The former colonial masters Marjoleine Kars reconstructs an extraordinarily rich day-by-day account of this pivotal event. Blood on the River provides a rare in-depth look at the political vision of enslaved people at the dawn of the Age of Revolution and introduces us were confined to a few plantations near to a set of real characters, vividly drawn against the exotic tableau of a riverine world of plantations, rainforest, and Carib allies who controlled a vast South American hinterland.the coast while the formerly enslaved

An astonishing and original work of history, Blood on the River will change our understanding of revolutions, slavery, and the story of freedom in the New World. were in control of most of the colo-

ny. Caribs and Arawaks fought on the

side of the colonists, eager to keep African competitors out of their territory. Dutch soldiers sent from neighboring Suriname mutinied and joined the very rebels they had come to defeat. African ethnicities and competing visions of freedom divided the rebels. Self-emancipated people welcomed the overthrow of slavery while dodging both the rebels and the Dutch. In the aftermath, the Dutch tried the leaders and interrogated hundreds of others. Their accounts provide a vivid picture of the internal workings of the rebellion and of the emotional life and aspirations of the enslaved in Berbice. Popular politics in the Berbice rebellion were as complex as any other in this era. During the Age of Revolutions (17631820s), not only elites but also peasants, Indians, ordinary whites, and enslaved people fought for greater autonomy and better lives, though how they defined these values differed greatly. Leaders of the Berbice rebellion wanted liberty to run a colony of their own with a measure Courtesy Marjoleine Kars of human bondage in place. Ordinary The collection included a remarkable diplomatic self-emancipated people wanted autonomy to tend exchange—letters between the Dutch governor and their own gardens without being exploited. This difrebel leader Coffij, paddled back and forth by Am- ference was a common theme in the revolutionary erindians in dugouts. Even more astounding was age: Elites wanted one thing; commoners wanted the post-rebellion testimony, revealing the voices of another; both called it “freedom.” n

RECOMMENDATIONS from Corey Sobel ’07

JOHN MICHAEL KILBANE

In The Redshirt, Sobel—a former Blue Devil linebacker—explores identity, masculinity, class, and more through the coming-ofage stories of two football players at a private university in North Carolina. Here, he shares books that inspired him.

Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens I like my Dickens late and dark, and have a passion for this story of an imprisoned debtor and his daughter. Dickens is thrilling in how he dramatizes systems—social, political, and in the case of Little Dorrit, economic. Debt deforms William Dorrit and his unendingly loyal daughter Amy, and this novel helped me think through how college football’s system of indentured servitude mauls bodies and souls in a similar fashion.

Autobiography

of Red by Anne Carson This novel in verse’s protagonist is Geryon, a boy who also happens to be a mythical winged red monster, and it follows him through an abuse-haunted childhood into his doomed love for Herakles, the hero fated to destroy him. My novel’s narrator, Miles, also feels baffled by the strange body he’s made to wear, and likewise struggles to remember that that body is capable of taking flight.

The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, Second Edition

My novel’s other main character, Reshawn McCoy, researches an enslaved poet I based on George Moses Horton. In the mid-1800s, Horton taught himself to read and went on to publish three volumes of deft, heartbreaking verse. I first learned about him in an AAS course with the brilliant Maurice Wallace, and still own the Norton anthology we used as our primary textbook. It was a delight to open the book during my research—and mortifying to read my late-adolescent marginalia.

The History of the

Siege of Lisbon by José Saramago A master satirist of power structures, there are books of Saramago’s that are more directly linked to The Redshirt’s themes (like The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis), but this novel has a very personal resonance for me. Its protagonist is a lonely proofreader awakened to his true self by a woman he loves and a book he writes; I got married as I was starting The Redshirt, and then worked on the manuscript between drab freelance proofreading jobs. You can fill in the rest.

BY DUKE ALUMNI & FACULTY

State of Empowerment: Low-Income Families and the New Welfare State

(University of Michigan Press) Carolyn Barnes, assistant professor of public policy and political science, and Andrea Louise Campbell

How to Write a Horror Movie

(Routledge)

Neal Bell, professor of the practice in the department of theater studies

The Lonely Letters

(Duke University Press) Ashon T. Crawley A.M. ’11, Ph.D. ’13

Sisters in Hate: American Women on the Front Lines of White Nationalism

(Little, Brown & Company) Seyward Darby ’07

The Haitians: A Decolonial History by Jean Casimir

(UNC Press) Translated by Laurent Dubois, professor of Romance studies and history; foreword by Walter D. Mignolo, professor of Romance studies and literature

Lula and His Politics of Cunning: From Metalworker to President of Brazil

(UNC Press) John D. French, professor of history

Survival of the Friendliest: Understanding Our Origins and Rediscovering Our Common Humanity

(Random House) Brian Hare, professor of evolutionary anthropology and psychology and neuroscience, and Vanessa Woods, director of Duke Puppy Kindergarten

The Brief and True Report of Temperance Flowerdew

(Blackstone Publishing) Denise Heinze Ph.D. ’90

Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America (University of California Press) Katherine Jentleson Ph.D. ’15

An alumnus ponders the university’ s anti-ra In the spring of 2018, I joined a group of student cist ef orts. By Michael Ivory Jr. leaders and student activists in a protest on the stage of Page

Auditorium during Duke’s Reunions Weekend. This weekend We were also protesting because we did not want to allow was a gilded one, as newly inaugurated President Vincent E. Duke any opportunity to believe that its work was done. There

Price welcomed generations of Duke graduates to revel in just were issues both on and off campus so pressing that an instituhow far the university had come on so many accounts. In fact, tion as vast and as powerful as Duke celebrating its progress felt this was a special celebration of the legacy of student activism. premature, to say the least. Gentrification continued to force

What troubled me and my fellow protestors, however, was nonwhite, and especially Black, Durham residents farther and what truths Duke seemed to be sidestepping to justify celebrat- farther away from the heart of the city they helped build. A coing what it called “progress.” There was, for one, the droves of herent hate and bias policy was yet to be found, in the wake of student activists who would not set foot on campus, exhausted such events as a Black Student Alliance poster defaced with the or wounded after years of researching, protesting, and challeng- n-word, a noose found hanging on campus, and a homophobic ing Duke, only to see change happen at a glacial pace. Adding threat against a queer Jewish student scrawled on the side of a to the toll taken on their well-being, just by virtue of the work residential building. To many, Duke was still “the plantation.” of activism, there were Duke’s punitive measures. Through ges- Knowing all of this, while I felt the planned protest was justitures ranging from a summons from Student Conduct to a po- fied, I was simultaneously terrified. My sole consolation was that lice presence to discourage protest, the historical Duke has had whatever happened would not happen to me alone. I locked arms no issue with flexing its muscle to quell dissent. For it to claim to with Trinity board of visitors member Bryce Cracknell ’18, and honor past activists while threatening current-day activists pre- our group interrupted the afternoon’s fanfare. sented an especially stinging irony to us. As one of us read the manifesto associated with our protest, several of the alumni in the room began to stir. At first it was a trickle of shouts: “Oh, come on!” “Get off the stage!” And then came the tempest. At the foot of the stage, alumni clamored, most (if not all) of them white. On the stage stood a handful of students, primarily Black or of color. From the crowd came shouts of “You don’t deserve Duke!” “Just be grateful you’re here!”

Once our manifesto was complete, we stepped off the stage and the alumni took the opportunity to get as close to us as possible as we processed out the room. I felt a compulsion to flee but stayed locked in place by the arms of my fellow protestors. Behind us echoed administrators’ apologies to the frustrated alumni.

In that moment, I was reminded that the problem of racism is a problem of roots. It is just as much a question of what nourishes life as we know and understand it, as it is about what antagonizes so many people’s right to live. Racism is often spoken of as a barrier. Too infrequently is it addressed as something that enables and permits.

Hearing those apologies to people who I am convinced were on the verge of spitting on me told me the side the university had chosen. At its core, regardless of the headway it had thought itself making on matters of race or general matters of equity, Duke was still content to settle the dust kicked up, rather than face what was unearthed.

It is with this memory that I read President Price’s sequence of communications announcing Duke’s effort to become an anti-racist institution. With the announcements came a website extensively outlining the number of initiatives the university intends to enact toward its anti-racist vision. Headings for the various initiatives address such goals as “furthering excellence for our faculty,” “revisiting Duke’s institutional history,” and “engaging with and supporting our Durham and regional communities.” The website is thorough.

Yet, I have to wonder: Has Duke University really reckoned with what racism means beyond a command of the vocabulary race scholarship has produced? Can a university like Duke, with its stronghold on the economic and political forces that define so many people’s access or lack thereof, truly make a claim to anti-racism? Would Duke be willing to face the truth that anti-racism is reckoning with the systems that make racism palpable and real, and give up power accordingly?

Given what I have learned in my time as a student and as an alumnus, I am sobered by how racism has affected so many at Duke and in Durham. For all the thoughtfulness that seems to have gone into this declaration of a new “anti-racist” Duke, I am ambivalent about how much fruit this statement will bear.

I speak of racism as a matter of roots because I also believe that the answer to racism requires uprooting. I believe this partially because of what I have witnessed at Duke, but also because of my own journey facing and understanding racism and other facets of oppression, both at and beyond Duke. In fact, much of this journey is intertwined with my matriculation at the university. What I was rooted to was called into question. I had to decide whether to yield to having certain definitions about myself and the world change or be utterly undone.

When I first arrived at Duke, I was more absorbed with the joy of being accepted than I was with most other emotions. To say I saw my new school through a rose-colored tint is an understatement. I grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Miami, far from the glitz of the shoreline. My acceptance to Duke was an exception to many of the rules of everyday life, and I came ready to prove myself worthy of the Blue Devil mantle.

I quickly learned that one of Duke’s favorite pastimes is visiting the nightclub and bar Shooters II, just off East Campus. So, I went. As I nervously huddled outside the club, making sense of the heat in the air as droves of eager first-year students clamored to join the noise inside, I struck up a conversation with another young Black man in the line near me.

Most of the conversation proceeded in a blur; I was mostly concerned with surviving the oncoming bustle as more and more students crowded the line to enter. Yet, eventually, I would learn that he was not a Duke student, but a native Durham resident. I was not from Durham, but a Duke student. Out of these facts came one of the most disturbing lessons I would ever learn.

“We really call Duke a modern-day penitentiary,” he said matter-of-factly. “We say that when you’re born, Duke signs your birth certificate. When you work, Duke probably signs your paycheck. And when you die, Duke signs your death certificate.”

The line continued to inch its way into the building. We would both make it into the club, only to lose each other quickly to the crowd. Still, those words never left me. I would eventually come to understand that, for all the excitement and accomplishment I felt in getting into Duke, my education was inextricably tethered to a history of subjugation and inequity in the city of Durham. Before I would even know Duke as “the plantation,” I had learned of it as “the penitentiary,” replete with bondage for many of the people who made both the city of Durham and Duke University possible. Just by virtue of attending a school that constantly rendered many residents of Durham feeling trapped, I was complicit in that foreclosure of access.

This was my first explicit experience of the nature of systemic racism as it enables and shapes Duke. As I continued to experience Duke for myself, that conversation returned again and again to remind me that even if my presence as a Black student at Duke seemed to reverse some racial tide, it was minuscule compared to the systemic racism that was built into Duke’s presence in Durham. I had embraced Duke, but what I rooted my identity in had been, and would continue to be, questioned.

I would come to understand through my time at Duke that I could not meaningfully reckon with racism at its root until I dealt with my identity as a participant in its function, even as someone oppressed by the very system. In this same way, I’ve witnessed Duke’s identity be questioned. Many of the protests, conversations, and demands issued in response to racism on Duke’s campus have revolved around wanting the university to face the truth of itself and respond accordingly.

Months after that encounter outside Shooters, I entered the gauntlet of academic and personal growth that defines the transition to college. Some of it was joyous, while some of it was uncomfortable, but I was still determined to prove my worth. I cannot help but admit how much of that determination was based in the reflexive sense that I did not belong at Duke. That the occasion of my being on campus as a Black first-generation student from a working-class neighborhood was historically uncommon. Still, I made the best of it through friendships and frequent calls home. Then, a noose was hung on campus. An image of the bright yellow cord, twisted into a sinister loop, circulated more and more widely until it reached the local and regional news circuit. I, stunned and disturbed, called my mother, and her immediate response was to offer me the chance to withdraw from Duke and apply for a local university in Miami. I insisted on staying.

In the following days, students rightfully inquired about the university’s response. There were e-mails. There were statements. There were convenings on the quad. Eventually, the university released an anonymous open letter penned by the student who had hung the noose, in which the person claimed the noose as an inside joke among friends, gone horribly awry. The writer went on to deny knowing the racial trauma symbolized by a noose in the United States, no less the South, and promised to do reading and personal reflection so as to ensure full understanding. Issuing from the student’s claim of ignorance came the administration’s firmly

planted stance: “This is not the Duke I know.”

Yet, as a first-year, I noted the immediacy with which Black and other nonwhite students responded. It was muscle memory. To them, the noose was not an interruption, but a culmination of the history of race on and around Duke’s campus. Even if the student who had hung the noose claimed ignorance, which in turn allowed Duke to reassure us that the experienced bigotry coiled in a noose was a misfire of friendship, the response of Duke’s constituency suggested this was not so foreign to Duke’s identity. For administrators to say this was not the Duke they knew denied a great deal of institutional history. What would my brief companion in the Shooters line have to say about this Duke that this noose and the administration’s reflex gestured toward?

As I understand racism to be structural oppression, an “anti-racist” ethic must also be a structural one. I don’t see it generative to treat “anti-racist” as a personal identifier that reverses a previous “racist” identity, because anti-racism can only be revealed through actions and commitments. In short, to dismantle racism is to sever ties with what endangers nonwhite people, and to make a commitment to what protects them. As I thought about this, I realized I should reach back to some of my peers and mentors to gain their thoughts on what this means for Duke in tangible terms.

“I’m not sure if we have done a really thorough job in terms of coming to terms with us being a predominantly white institution,” says Li-Chen Chin, assistant vice president for intercultural programs in Student Affairs, who also teaches in the program in education. She specifically cites how Duke’s curriculum is shaped by an agenda that prioritizes white, Western histories. “When you talk about the history of the Americas, we can’t ignore the role of the Black diaspora and Native community. There really needs to be a fundamental shift in the curriculum.”

While my personal experiences are primarily tied to my Blackness, my time in Durham, and my own experiences of racism, I know it’s vital to remember that the question of anti-racism is also a question of the land. Chin’s mention of the role of Indigenous people and anti-Indigenous racism in the forming of American society speaks to much of the work done by Indigenous people to name that. In fact, Duke, in its reckoning, must face the fact that it is based in the state with the largest Indigenous population east of the Mississippi River. As I explore Duke’s history, I am reminded that anti-racism cannot be wed to the insistence on coexistence within our present way of living. Even I, as a Black person, would have to reckon with the question of taken land. Chin’s comments also reminded me that history, and the way it is told, is a function of power. Elizabeth Barahona ’18 is a former president of the Latinx student organization Mi Gente and a current history Ph.D. candidate at Northwestern. I talked to her about this question of history and how it shapes knowledge in the present.

“Duke was made Duke University because of the donation made by the Duke family of $40 million,” she told me. “Because of that sort of donation, Duke has always positioned itself as not ever having slave money.” Instead, she says, Duke cites the tobacco money that lines its coffers in lieu of slave money. Yet, she points out a flaw in that logic. “Leslie Brown, [a] Durham historian, says that Black women who were rolling tobacco and processing it…were working in slave-like conditions. And we all know from the history of Reconstruction and the history of Jim Crow that slavery never ended. Slavery was transformed.”

I know intimately the harm intrinsic to sharecropping. My mother’s expression still turns somber when we discuss Duke’s tobacco money, because her grandfather was a tobacco sharecropper. The exploitation of his financial, physical, and mental faculties left him worn and penniless. While he may not have worked the same plantations that fed Duke’s wealth, the irony of his life and Duke’s founding within the same industry relentlessly stretches across state borders. This history may feel distant, but I sense it is still present in Duke’s configuration today.

Two years after I graduated from Duke, I lived on Onslow Street, which cut through the heart of Walltown, a historically Black neighborhood near East Campus. As I commuted between my home and downtown Durham, I would often hear some variation of this phrasing as people

reflected on their hustle through morning traffic: “Durham sure has grown. Nobody used to want to live here, it was so bad.” Those comments would either come from a fellow transplant to Durham, or from a colleague at Duke, lauding the university for drawing business to the region. Each time, though, I was troubled because I grew up in a rapidly gentrifying Miami neighborhood like Walltown. Then and now, it felt as if the powers that be were all too eager to discard Black life when there was money to be made. It was lucrative.

I will not deny that as a student and an employee, I benefit from Duke’s wealth. Yet this does not prevent me from noting that this wealth is both the result of and reason for much of the oppression Duke purports to combat. Any critique of racism necessarily becomes a critique of capitalist wealth. If nonwhite people are regularly dispossessed of access to health care, education, and housing with the usual concern being who can “afford” to provide these resources, then I am very interested in challenging the notion of wealth at its core. What is “wealth” that is not contingent on another’s lack or another’s endangerment?

“In terms of an institution being fundamentally just, everything about its creation has to be considered,” says Chandra Guinn, director of Duke’s Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture. “To exist within a capitalist system means that there are some questions around morality and fairness that are probably not going to be answered in a positive light. Does Duke become Duke without [Julian] Carr’s contribution of the land?” (Two years ago, the university removed Carr’s name from the building that houses the history department; even as Carr was instrumental in the relocation from Randolph Country, he was an active proponent of white supremacy.)

With this in mind, I reached out to Charmaine Royal, who heads up Duke’s Center for Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation. In our conversation, we discussed how Duke may see its anti-racist effort as making it an equal stakeholder in the decisions communities make to heal, when in actuality much of it might be Duke simply allowing communities to take the lead to name and resolve historical harms.

“Unless we deal with the history, and see our role in what is, we won’t understand what we really need to do to change things,” Royal told me. “Maybe when we see what we’ve done, we’ll realize we do need to step out of the way…. I have my doubts about how deeply we want to get into that.”

That “step out of the way” spoke to a core belief I found myself struggling with. It wasn’t until I returned to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, which is included in Duke’s anti-racist and Black liberation reading list, that I found the language: …people find it very difficult to act on what they know. To act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger. In this case, the danger, in the minds of most white Americans, is the loss of their identity.

The anti-racist struggle is just as much a struggle to give up as it is to gain. Duke must be willing to face the “danger” of its form and function being shifted and transformed. As I see it, “stepping out of the way” means Duke cannot center its own interests in the conversations and subsequent solutions. If the problem-solving efforts reproduce the same power dynamics that yielded the issue, then it is not a challenge to racism, but an attempt to placate.

As I write, my mind returns to the moment when I was descending the steps of the stage in Page Auditorium, hearing fresh apologies from administrators to alumni that were in my face reminding me that a future alumnus did not deserve Duke. I remember realizing that even if Duke did not create what felt like violent racism, it did not immediately condemn it. I remember that Reunions Weekend is a bid for the ongoing favor of alumni—a push to keep Duke’s roots intact.

I reached out to Bryce, who grounded me as we left Page, to ask his thoughts on Duke’s relationship with its alumni, and how that might affect anti-racist efforts.

“If the purpose is to continue to get money from alumni, I don’t know that the university can make fundamentally different decisions,” he says.

Still, he says, even in donorship there may be some assumptions worth investigating and deconstructing. “What alumni are we missing? Why are they not engaged or involved in broader Duke networks? What can you get from alumni other than dollars?”

What Bryce illuminated for me is the question of imagination. While Bryce’s considerations home in on specific issues within Duke’s operations, I am especially excited by how they point to the possibilities for an education that is not tethered to the precariousness of Black, Indigenous, and nonwhite communities. This is about Duke no longer making justice fit into its current framework, and instead, allowing justice to define what new frameworks are necessary.

For all the thoroughness in the intention of Duke’s anti-racism initiative, I haven’t seen a true and productive interrogation of Duke’s fundamentals in its past efforts. Duke has a number of ways to enact its anti-racist vision, but here is what I know: Race and racism have always been a matter of roots.

I cannot remain satisfied with the pruning of branches.

Ivory Jr. ’18 studied political science and minored in French. He is a Miami native who continues to carry the city with him and is currently pursuing an M.F.A. in creative writing at North Carolina State University.

Steven Heritage

SEARCH: Duke Lemur Center researcher Steven Heritage and Djiboutian ecologists Houssein Rayaleh, right, and Djama Awaleh set sengi traps on a rocky hillside.

Here a sengi, there a sengi

IN SEARCHING FOR AN UNDERSTUDIED AFRICAN MAMMAL, LEMUR CENTER RESEARCHERS LIVED A TALE OF “DISCOVERY” AND LOSS. | BY CORBIE HILL

MAYBE THIRTY FEET from the campsite something rattled in a trap.

It was nearest Galen Rathbun’s sleeping bag, and it wrecked the veteran ecologist’s sleep. “God, that animal has been keeping me up all night long,” the California Academy of Sciences’ Rathbun told Duke’s Steven Heritage a few hours later, when the scientists woke up early enough to beat the fierce Djiboutian sun. The two exchanged a meaningful look, and while they were discussing how to proceed, Rathbun picked up the trap and peeked in.

That was early February 2019 and Heritage’s second morning in Djibouti. The day before, the Duke Lemur Center researcher had touched down in the Horn of Africa jet-lagged and tired from a long flight. Djibouti City— the capital and only city—isn’t big, and the nation itself is about the size of North Carolina’s Triangle region. Heritage spent a night in a hotel, with its comfy bed and running water, and hit the grocery store the next morning to stock up on fruit and nuts and food that would keep for weeks at a time, in a Land Cruiser, in 110-degree heat.

And then Heritage, Rathbun, and Djiboutian colleagues Houssein Rayaleh and Djama Awaleh left Djibouti City for a rocky wilderness called Djalelo, all on the gamble of finding a minuscule creature researchers knew precious little about.

No specimens had been taken in five decades.

Though also known as a species of elephant shrew, the Somali sengi is neither. It’s about the size of a mouse, but only superficially similar (humans are more closely related to mice than sengis are, in fact). It’s insectivorous, with a long snout and gazelle-like hind legs. Sengis mate for life, and their offspring can sprint within an hour of birth.

The sengi itself is an ancient endemic African mammal, its lineage predating even the charismatic “big game” African mammals. Heritage sounds al-

Houssein Rayaleh

most proud as he describes HANDFUL: Heritage its roots, which he has holds a Somali sengi. studied extensively. Not “They don’t bite,” he only is Heritage a sengi says. “It’s nice.” specialist, but he works at the Division of Fossil Primates, a department of the Duke Lemur Center focused on the mammalian fossil record. If it happened after dinosaurs but before now, its remains are studied here, by Heritage, curator Matt Borths, and their colleagues. The division houses remains of entire extinct genera the layperson has no reason to have heard of, as well as the ancestors of modern creatures like lemurs and, yes, sengis.

Among sengis, Somali sengis were especially data-deficient, with fewer than forty specimens in collections, as of early 2019. Some of these were “pickles”—specimens preserved in formaldehyde— and many more dated from the late 1800s and early 1900s. “And they’re just scrappy,” says Heritage. “Here’s a skull and, like, part of the skin of the animal.”

Needless to say, there were no photos or DNA samples.

None of this indicated that the Somali sengi was rare, but understudied. Decades of instability in Somalia made biological expeditions to that country unsafe, leaving a possibly common animal off-limits to the wider scientific community—even if Somalians saw them regularly. And this brings up a question of perspective that was historically absent in Western scientific literature: “The first sengi that ever got brought back to Europe in the 1800s from Somalia, even that wasn’t a discovery,” says Heritage. “The people that lived in Somalia already knew that sengis were there before the Europeans showed up.”

Since Somalia borders Djibouti, Heritage had the idea of a collaborative American and Djiboutian expedition. A mutual friend at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History connected Heritage and Rayaleh in 2017, and soon the two were planning a small mammal survey.

Djibouti is a biodiverse region, Rayaleh says, and its terrestrial and marine biomes range from under-

explored to unexplored. For one, CUTE: Neither there are few Djiboutians work- elephant nor ing in biology or conservation: shrew: the The nation’s university, he says, Somali sengi is all of ten years old, and its faculty tend toward law and the humanities rather than science.

“It seems I am the only crazy man who runs the countryside to see birds, mammals, reptiles, plants, and so on,” Rayaleh says.

Educated in France and Djibouti, Rayaleh started his “nomad city boy in the countryside” career teaching elementary school in remote villages, eventually moving into school administration and biological research. By the end of the ‘90s, he was organizing and coordinating expeditions studying different taxa— birds, reptiles, mammals, insects—and birdwatching tours. Having spent decades in rural and wild Djibouti, Rayaleh knew what lived there.

“The only thing I did not know was the taxonomy of the sengi in Djibouti,” he says matter-of-factly. “As a long-lasting naturalist in Djibouti, I encountered it many times.”

Based on interviews with locals and his own experience, Rayaleh selected Djalelo as the first field site, confident the team would find sengis. He chuckles as he thinks back to his American colleagues’ impression that these creatures would be difficult to find. From the international scientific community’s perspective, however, there remained no guarantee that the sengi species in Djibouti was the Somali sengi.

“You can imagine that if the IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature] has no records of any of that taxonomic order from that country, it’s really kind of a risk to go there,” Heritage says. “There have been three or four previous small mammal expeditions to Djibouti, and none of them had produced any sengis.”

Steven Heritage

It was late afternoon by the time the team reached Djalelo Wildlife Protected Area. Like much of Djibouti, Djalelo is made up of rocky basalt hillsides, many at fifteen to thirty-degree grades. Heritage tore holes in his boots trekking across rocks and acacia thorns, though his Djiboutian colleagues happily walked around the campsite barefoot.

The team scoped the Djalelo landscape, checking for scat and paying attention to how rodents like gerbils, mice, and gundis moved through the terrain.

Elsewhere, in Namibia and South Africa, sengi species live in sparse woodlands or flat gravel plains— nothing like this. Finding sengis, then, held its own set of challenges on these rock-strewn hillsides.

Traps get lost or—in one instance this expedition— smashed by baboons.

In Djibouti, all sengis are called wali sandheer: wali for “small scurrying mammal” and sandheer for “long nose.” Photos existed of some kind of sengi at Djalelo—including one that was sent to the team days before the expedition—but it could have been another known sengi species or even an undescribed one.

The team picked a spot on the horizon. Then the four walked ten paces in that direction, put down a trap, moved ten paces, and set another. It went like this: Lay the trap against a rock or under a bush.

Bait the trap with a mix of oatmeal, peanut butter,

and marmite. Tie yellow flagging tape around a nearby rock. Take GPS coordinates. Move on. When it’s time to turn back, walk ten paces to one side and return to the starting point, ten paces at a time. Working together, Rathbun, Rayaleh, Awaleh, and an already sunburned Heritage laid 100 traps each day.

At times, Rathbun was in pain, Rayaleh recalls, but insisted on pushing forward.

Late the first night at Djalelo or early, early that morning, Rathbun heard something trip the nearest trap. Again—he woke at dawn, groused to Heritage that it had kept him up all night, and picked up the offending trap.

“It’s a sengi,” he said.

“No way,” Heritage replied.

“See? I told you,” Rayaleh said. “They’re all over the place here.”

Rathbun noted its tufted tail at first glance, and

Heritage checked its incisors. From these indicators, the team was all but certain it had a Somali sengi.

Science is a patient discipline, and it would take further analysis to say for sure, but that didn’t stop a sense of excitement that now, finally, missing data could be gathered—things like the Somali sengi’s habitat and diet and distribution.

“I can’t believe it,” Rathbun said. “I’ve never seen one before.”

Not long after Rathbun and Heritage returned to the States, the first DNA analysis came in, which indicated at the very least that this sengi belonged in its own genus. Heritage and Rathbun put off saying with certainty that it was a Somali sengi until the data were more complete, and Rathbun’s sentiment was that he’d be happy to be surprised. Yet a few weeks after returning to California, he became ill with metastatic melanoma, and died in April 2019.

Rathbun was easy to work with, says Heritage, a scientist to whom fieldwork came naturally and who made expeditions fun, razzing colleagues and even “playing chicken” with a camel at one point during the Djibouti trip. Heritage is in contact with his widow, Lynn Dorsey Rathbun, who has told him that bringing this missing species back FIELDWORK: into the realm of science was the Rayaleh, perfect end to Rathbun’s life’s work. standing, and Indeed, when the Somali sengi was Awaleh with a reclassified into a new genus, it was sengi trap named Galegeeska: Gale- for Galen;

geeska for the Horn of Africa.

This expedition was a win for Djibouti, too, Rayaleh says. Djiboutians don’t tend to know the true taxonomy or conservation status of the species around them, for one, and as a result of his team’s fieldwork, one long-“missing” creature is returning to the scientific community. A former French colony, Djibouti has only been independent since 1977 (Rayaleh was seventeen), and historically it’s been negatively stereotyped or useful only to world powers as military barracks and bases, he says. Yet this discovery highlights biodiversity in Rayaleh’s homeland, where he hopes a new generation will answer the call of ecology and conservation. “Natural history research in Djibouti is an important step in my country’s renaissance,” Rayaleh says.

And then there’s widespread media coverage. The Somali sengi is a furball with big eyes, round ears, a tufted tail, and a funky little trunk. It’s cute. People tweet about it, Rayaleh says. They draw cartoons of it. It’s a positive, scientific story about Djibouti, which has been a long time coming.

Since the Djalelo expedition, he has traveled to Durham and met with Duke Lemur Center director Greg Dye, Division of Fossil Primates curator Borths, and—of course—Heritage. Rayaleh’s next step is discussing the future of Djiboutian fieldwork with the Duke Lemur Center, Smithsonian, and other American institutions. “I am not young, and we need FRIENDS: A the young generation to continSomali sengi ue the same thing I am doing nestles on Galen now,” he says. Rathbun’s vest. In that moment, in February 2019, Rathbun, Heritage, Rayaleh, and Awaleh had in their trap what would turn out to be the Somali sengi, which had not been documented in the wild in more than five decades. They could only celebrate for so long, because there were ninety-nine traps still out on the hillside, and these needed checking before the fierce Djalelo sun hit their aluminum frames. (“Then you’re baking animals. And that’s not cool,” says Heritage).

So, the team put the first trap in the shade of the Land Cruiser, found the preselected spot on the horizon, walked ten paces to the next trap, and peeked inside. n

The man with the plans

With a Duke career extending across three presidencies, Tallman Trask has played a key role in remaking the university and its surrounding community.

BY ROBERT J. BLIWISE PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS HILDRETH

When, back in 1995, Tallman Trask III was emerging as the likely choice as Duke’s executive vice president, law professor James Cox was chairing the search committee. He did what search-committee chairs typically do: He called an administrator at the University of Washington, where Trask was then working, to check him out.

The conversation didn’t start on a typical note. “There was a pause. Then all of a sudden, there was this sigh,” Cox recalls. A long sigh. And a personal observation: “He plants flowers.”

Where is this conversation going? Cox wondered. But the administrator went on: “One of the first things I noticed when Tallman came on board is how beautiful the campus suddenly became. He planted flowers. Over his tenure here, I just realized, God put us on the world for some special purpose. And Tallman was put on this planet to make universities better.”

Cox makes a sweeping gesture to take in his lawschool surroundings. Construction that, over the years, has overtaken the school’s original featureless façade of red brick. Just out of view, a glass-enclosed oasis for eating and conversation. A stand of trees that’s been preserved through all the physical growth. “When I look out my window now, the scene is a lot more beautiful than it was before Tallman came.”

Trask retires at the end of the calendar year, a halfyear later than originally anticipated. Vincent E. Price, the third Duke president Trask has worked for, says it became clear that the timing of the transition had to be adjusted: “When the pandemic hit, we had the benefit of an experienced executive-leadership team to navigate the university through unchartered waters. It was important to keep that team together.”

Duke is looking to its centennial in 2024. And it’s striking, says Price, that Trask has been a major presence at Duke—really a major shaper of Duke, and not without controversy—for a quarter of that time. It’s quite a portfolio: finances, campus planning, real estate, human resources, information technology, stores, maintenance and construction, safety and security, parking and transportation.

CURTAIN CALL: Trask in Baldwin Auditorium, whose 2013 renovation he oversaw. “I wanted Baldwin to be a Duke building, which is why the interior is blue and white. I also wanted to overwhelm the N.C. State-red seats in DPAC, which I intensely dislike,” he says.

More than being a builder, Trask had “a strategic sense of the campus” and saw “the importance of Duke as a cohesive and coordinated architectural entity. ”

Trask's office is a museum of memorabilia documenting the evolution of Duke's campus. The following objects are just a few examples in the collection, some of which will be moved into Duke's archives for permanent safe-keeping:

These soda bottles, dating from the 1920s, were found during the excavation for the new Baldwin mechanical room— apparently thrown off the original construction site by workers.

His manner can seem gruff, but it can also seem refreshingly direct. In any case, it’s brought results, right from the beginning. He talks about how Student Affairs was initially in his area. “The argument made to me was, ‘Well, students are in the dorms, the dorms are buildings, and that’s what you do.’ Well, that’s just weird.” So a trade ensued. Student Affairs went to the provost, the academic side of the campus. Information technology had been in the domain of the provost. That was weird, too, he argued. It became part of his portfolio.

One of the first things you notice as you walk into Trask’s office, on the second floor of the Allen Building, is a message, taped to the door, from a Panda Express fortune cookie: “You are a charmer.” On his desk he has a big red button; when you hit it, a mechanical voice calls out, “No!” His longtime assistant, Nancy Metzloff, has a corresponding big green button: “Yes!” Now and again, they engage in a cacophonous back-and-forth.

If Trask doesn’t feel he needs to be a conventional charmer, he’s happy to express his own sense of style. Beyond the pocket squares with matching socks, there are the madras jackets, the rainbow-colored Nike sneakers. ”My sartorial sense is purely Pasadena,” says the native Californian. “I’ve dressed that way more or less since I was in high school.”

His office shelves are packed with books on design and architecture. Some showcase star architects like Frank Gehry and Cesar Pelli; there are also Trees and Shrubs; The Stones of Naples; The Campus as a Work of Art; Scandinavian Design; American Gargoyles. (There are also nods to more mundane aspects of campus planning, like The High Cost of Free Parking.) On his desk, you can spot a standard computer and a not-so-standard screensaver. It rotates between the image of a 1973 Porsche, the very first Trask-owned Porsche, and Porsche portrayals through the years—an attachment inherited from Trask’s sports-car-driving father.

Trask arrived at Duke three years into the presidency of Nannerl O. Keohane. Cox recalls it as “the search from hell”; it stretched over two years. For his part, Trask says, “If you would have asked me six months before I decided to move to Duke, ‘What are the odds you would move to North Carolina?’ I would have said, ‘Can odds be less than zero?’ It just wasn’t on my radar.” But the University of Washington soon was in the midst of a messy presidential transition. So he adjusted his expectations.

Having graduated from Occidental College, Trask had earned an M.B.A. from Northwestern and finished a Ph.D. at the University of California, Los Angeles. His doctoral dissertation was “Student Perceptions of College Administrations.” It’s filled with data sets, mathematical modeling, and statistics-driven concepts like “correlational matrixes.” He applied all those tools in exploring university culture. Universities with top-down governance, he found, tend to rate lower on “institutional quality measures.” He pondered a cause-and-effect quandary: “Does the low-quality factor induce an environment which can be operated only with a firm hand, or do more restrictive administrative styles hold back the academic development of the institution?”

Keohane had a firm sense of her own administrative style, but at the time she recruited Trask, she was still building a team of top administrators. She found in Trask someone who understood higher education from his own experience, and from having studied it. “I figured that he would be the kind of executive vice president who would fit well with the academic side— would fully understand it, but not try to manage it. And that’s exactly what happened.”

Trask had been in charge of academic and ad-

ministrative computing at UCLA, as vice chancellor for academic administration, when he was in his mid-thirties. Duke’s IT past and present are wrapped together in another of his office displays. It’s a bundle of data-carrying wires recovered in the midst of a library renovation; those wires would have carried data under protocols now considered exceedingly slow (kilobits per second, not the current gigabits per second). He says, “We got it right, and we got it right early. Unlike other places, we didn’t have eight-figure failures in the process. Now we’ve got the infrastructure everybody else wishes they had. And we run it across the entire enterprise, including the School of Medicine and the three hospitals, which nobody else does.”

Part of what energizes Trask, says President Price, is the chance to build systems—from information technology to payroll. “I think he finds them as interesting and challenging to envision and construct as a new building would be to envision and construct. It’s satisfying for him to contemplate a building when it’s up and running. He gets the same satisfaction from an administrative system when it’s up and running.”

Trask’s role of overseeing finances has coincided with economic upswings and downturns—none ENGINEERING: The more dramatic than work of ZGF, part of the pandemic. Duke Trask’s architectural announced a series of brain trust cost-saving measures: expenditures above $2,500 requiring approval from the top of the hierarchy; a hiring freeze except for positions deemed essential; no salary increases for all those earning more than $50,000; no university-paid retirement contributions for a year; temporary salary reductions for highly paid staff; a pause in new construction projects.

To Trask, this all feels different from the earlier moment of financial stress, which came with the Great Recession in 2008-09. Back then, the most worrisome hit applied to the endowment. But endowment performance over a single year or so wasn’t bound to affect university spending levels all that much: The payout policy takes into account the returns over several years, and so is designed to smooth the effect of market fluctuations. It was just a matter of waiting out the markets as they recovered. Now, though, the revenue hits persist, with no clear endpoint for losses in dining, housing, stores, parking, and elsewhere.

In the end, Duke “will have to be a little bit smaller,” Trask says. “But 99 percent of colleges

Each day, pre-iPhone, longtime assistant Nancy Metzloff typed a schedule notecard for Trask which he carried in his breast pocket. He saved them. This stack is only a fraction of the stash.

Before the chapel’s renovation, a part of the ceiling fell—fortunately, when it was empty. This piece, found during inspection, was just barely still attached.

This marker was made by Charles B. Wade Jr. from a Duke Chapel pew salvaged from the 1971 fire there. and universities would be happy to have Duke’s problems. Their problems are a lot worse.”

A pandemic hardly figured in the scenarios imagined for higher education. But Duke’s president during the Great Recession, Richard H. Brodhead, says Trask at the time “saw what was coming, if not necessarily on the scale it would take. Because of that, we weren’t as far out over our skis as some universities were. Tallman took the message that there were reasons for caution.”