S ha ped by th e

Deaf History through Deaf Art

Curated by Brenda Jo Brueggemann

Erin Moriarty

Octavian Robinson

Additional suport has been provided by the National Technical Institute for the Deaf at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

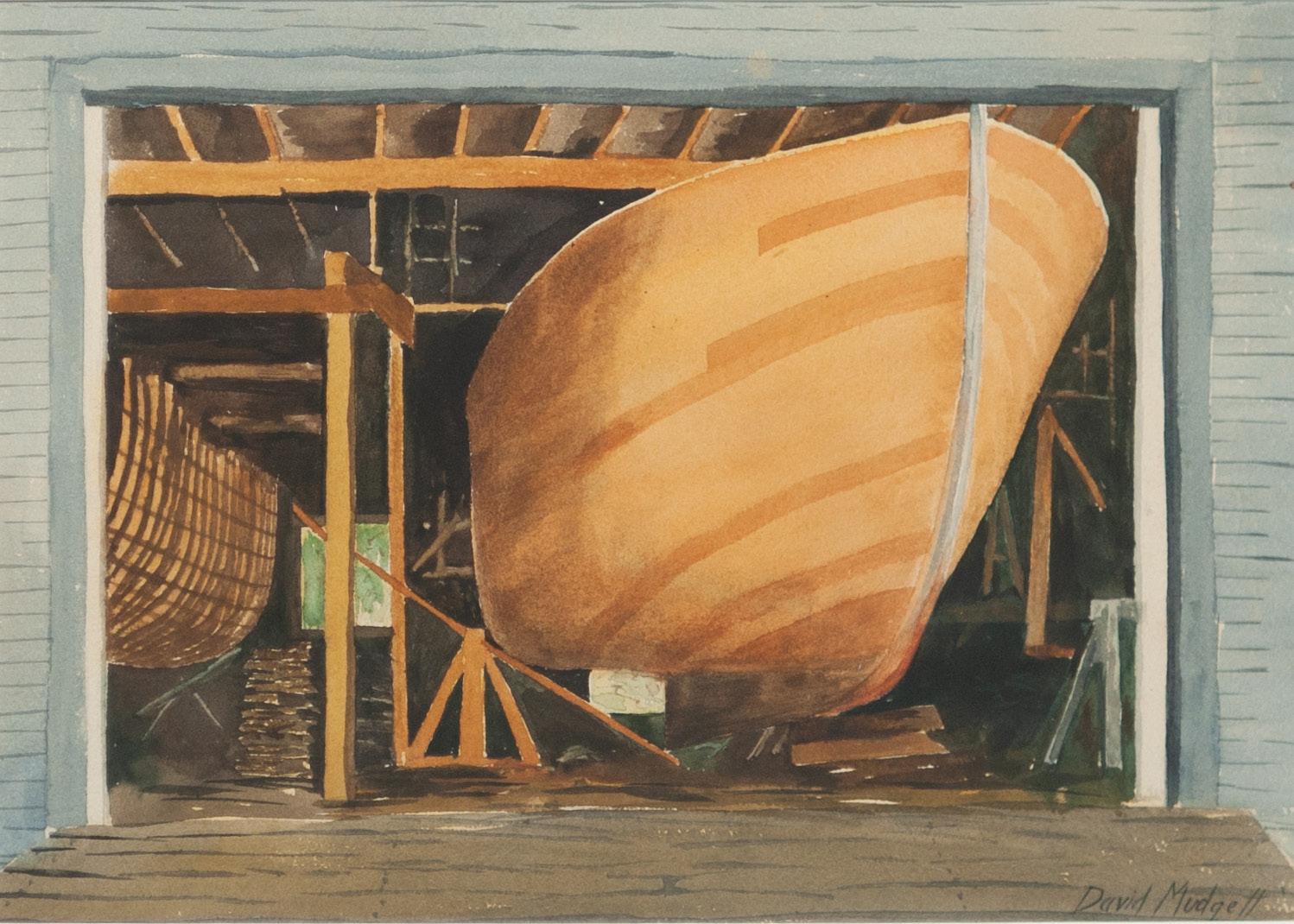

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

Gas Station - Jacksonville, IL, c.1965

Watercolor on paper

22 x 27 inches (55.8 x 68.5 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Offering and embracing an iconic American scene, the gas station, Mudgett’s fall-themed watercolor painting renders a still life. The work itself suggests a sociality, and community, with the fabric of everyday American life.

Preface

The American Dream puts forth a narrative of progress, modernity, and opportunity. Those narratives were not without tension as people wrestled with what it meant to be part of creating a more perfect Union. Deaf people became swept up in those narratives and tensions. Schools for deaf children were touted as evidence of national progress, signed languages signaling an enlightenment of sorts. As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth century, progress and modernity took a different direction. The United States and western Europe engaged in competition for global economic, military, and political dominance. This competition generated ideas about perfecting humanity. One popular idea, eugenics, took root. Eugenic measures that sought to strengthen the American stock included efforts to eradicate deafness and signed languages from the population. Eugenics, coupled with scientific and technological innovation, cast a specter over deaf Americans. Powerful figures, like inventor Alexander Graham Bell, believed that signed languages and deafness weakened the human race and threatened nationalism. They also believed that signed languages were evolutionary throwbacks appropriate for indigenous peoples but not fit for the evolved race of humanity. Eugenic efforts included reforming deaf education through bans on signed languages in schools that served white deaf children, breaking up deaf spaces and social relations, and stigmatizing public use of signed languages. The attempted destruction of deaf spaces and pressure on deaf people to conform to “performative hearingness” created communities and artifacts of resistance. Among those was the Deaf Pride movement. By the late 20th century, with innovations in video and communications technologies, increased mobility, and expansion in disability rights, deaf cultures and signed languages, deaf people asserted their place in the American public sphere and its history. Deaf artists communicated the tensions between their deafness, signed languages, and efforts to navigate American nationalism and exceptionalism in their work.

—Octavian Robinson

Accessing Deaf Art

Brenda Jo Brueggeman

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

Sound of Flower (detail), c.1958

Mixed media

48 x 37 inches (121.9 x 93.9 cm)

Gift of Joan Ankrum

1992.01.002

What is sound, but sensation? The sound of flowers is their smell, the gentle brush of the petal on the cheek and ear. It is also the sensation of a flaming orange sun radiating warmth, a warmth reflected in the slight smile on the figure’s face as they lean down to listen to the flower, an act that may be futile but also brings pleasure through sensation.

It won’t always be easy. Like the ASL sign for access itself, we might have to sneak in and under the thing a bit and have it move toward us as we also attempt to approach it at the same time.

This essay aims to access deaf art by leaning into it, turning it over a bit, and also inviting it to come forward for us. Offering a spotlight first, it chronicles some of the places we can find deaf art and artists—and especially critical, historical, cultural references to them. It also, on the other darker side, suggests reasons for the relative absence of deaf art and artists in the overall critical, historical, cultural canon of American art.

Spotlights and Presence

Jack R. Gannon’s 1981 book, Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America (republished in 2011), devoted an entire chapter (64 pages) to the subject of deaf artists. Gannon’s chapter contains short biographical sketches that are sometimes enhanced by claims made about the art/artists in media or exhibit catalogs and, importantly, a selection of images for each artist’s work. Twenty-six artists are represented there: Hillis Arnold, David Bloch, Morris Broderson, John Brewster Jr., John Carlin, John Louis Clarke, Theophilus Hope d’Estrella, Robert J. Freiman, Louis Frisino, Eugene E. Hannan, Regina Olson Hughes, Felix Kowalewski, Frederick LaMonto, Charles J. LeClercq, Betty G. Miller, Ralph R. Miller, Henry H. Moore, Granville Redmond, William B. Sparks, Kelly H. Stevens, Douglas Tilden, Cadwallader Lincoln Washburn, Tom Wood, Hilbert Duning,

Olof Hanson, and Thomas Marr. Seven of these artists—Bloch, Broderson, Clarke, Kowalewski, LaMonto, Betty G. Miller, Washburn—also have work represented in this exhibit.

In Deborah Sonnenstrahl’s definitive text from 2002 (twenty years ago), Deaf Artists in America; Colonial to Contemporary, she also acknowledges Harry G. Lang and Bonnie Meath-Lang’s 1995 book, Deaf Persons in the Arts and Sciences as an important beginning and “biographical dictionary”—though it “contains no reproductions of artworks” nor does it necessarily offer critical analysis of the artists and their works.

In a span of twenty years then—from Gannon (1981) to Lang & MeathLang (1995) to Sonnenstrahl (2002)—foundational bricks in the structures of deaf art and artists in America were laid down using biographical notes, chronologies of exhibits, major artistic achievements, and some critical commentary and “a closer look” (Sonnenstrahl) at interpreting some of the art. Gannon and Sonnenstrahl also significantly included visual images of some of the artwork itself.

Despite a good number of events, exhibits, movements around deaf visual art (see below), a way to see, interpret, define, represent deaf (visual) art is still more or less missing and unwritten. Sonnenstrahl articulates these issues of absence—even from 20 years ago—in the introduction to her definitive Deaf Artists in America text:

There is no literature on the unique aesthetic of deaf artists… Seminal questions remain unanswered: how do artists see their world, how do deaf artists interpret their world, how do deaf artists define their world, and finally how do deaf artists represent their world? [italics mine] (xxiii)

The elements of this exhibit do some important work forward in trying to answer some of Sonnenstrahl’s key questions.

Since Sonnenstrahl’s foundational 2002 text, other sources have also appeared that make significant critical and creative contributions to the work, study, scope of deaf art/artists in America. Earlier featured texts about specific deaf artists offer different elements of insight and engagement. In 1988, for example, Vivian Alpert Thompson crafted an essay about deaf artist, David Bloch, and his harrowing, haunting, and vivid Holocaust artworks. Thompson’s essay appears her collection, A Mission in Art: Recent

Holocaust Works in America; she outlines Bloch’s artistic career overall before engaging a more detailed analysis (in short form) of 29 different Holocaust-centered artworks by Bloch, folding out from the Dachau concentration camp. Thompson notes, for example, that all of these paintings were 13” x 48”—“a unique and demanding size, but one meant to be symbolic of the boxcars that transported the Jews to the death camps.”

Also in the same year, March 1988, the U.S. Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art completed a long (and rather disturbing and grilling, at points) “oral history interview” with Morris Broderson. Broderson’s lifelong agent and partner, Joan Ankrum, not only participates in the interview but sometimes controls many parts of it while the Smithsonian Institute interviewer, Paul Karlstrom repeatedly tries to rivet the conversation back to a forced reading of the impact of Broderson’s “isolation” and deafness. But Broderson will have little to do with that narrative, telling us instead that “I was not unhappy. I went up to the mountain to go swimming…” And when his agent/friend (Ankrum) later tries to directly suggest, in conversations about Broderson’s drawings that feature Anne Frank, that “you were locked up because of your hearing”... he quickly and directly replies “Not that locked up.” And too, late in the interview, Smithsonian interviewer

(Karlstrom) questions if he (Broderson) was “alone… an artist not connected to all those other wonderful artists in the world? Are you isolated? Are you an individual, or do you feel connected with other artists?” At this “isolation” probing, Broderson turns that conversation around another way: “I’m the artist. I want to be Broderson. Not like the other artist’s work. I do my own way, to see what I like doing. That’s part of my life. I’m Morris Broderson of art.”

Much of this historic Smithsonian interview seems to work toward enforcing a circumscribed and stereotyped identity–and a script of isolation and being “locked up.” There are other examples beyond the ones I’ve quoted here. And Broderson’s deaf identity is not the only one that seems to be questioned and attempted to uncloak in this interview. But Broderson won’t let it/them isolate, uncloak, or lock him up. This troubling interview plays out a particularly locked, scripted, and isolating way of imagining deaf art and deaf artists in the late 1980s (just as the March 1988 Deaf President Now protests are erupting on the national and global scene).

Aside from the essay on David Bloch and the Morris Broderson interview with the Smithsonian, other wide public access to some deaf artists appears on Wikipedia or in blogposts. See, as a few good examples, the Wikipedia entry for Cadwallader Lincoln Washburn or the Geneva Historical Society blogpost entry (2015) on “Deaf Artist Francis Tuttle.”

Circa 1989, and in connection with the first international Deaf Way global event, a new and groundbreaking entity related to Deaf Artists in Amer-

Self Portrait, 1983

Oil on canvas

27.25 x 21.25 inches (69.2 x 53.9 cm)

1984.01

Lighthouse Pier, Seneca Lake, n.d.

Oil on canvas

8.5 x 21 inches (21.5 x 53.3 cm)

On loan courtesy of Historic Geneva

ica makes the scene: De’VIA. Defining its existence as “an art movement formed by Deaf artists to express their Deaf experience” and shorthanding for “Deaf View Image Art,” DeVIA’s impact is still being felt, in ripples and repeated waves, throughout the 21st century Deaf community and culture.

Deaf artist and DeVIA manifesto maker, Chuck Baird, chronicles De’VIA’s role in “A History of Deaf Art” in a 2004 publication arising from Utah Valley State College’s “Deaf Studies Today!” conference. Baird’s lively narrative history outlines twelve different events and websites devoted to the coming out of American Deaf Art from 1989-2004. He especially credits Betty G. Miller as “being the first Deaf artist to expose the country to the genre” since “she had a strong and clear vision of what she was doing.” Baird also suggests in this essay that “in the Deaf community, visual arts, too, were the last to emerge” (in social and cultural changes).

Also stemming from that same Utah Valley State College “Deaf Studies Today!” conference, Patti Durr offers a meaningful contribution on “Investigating Deaf Visual Art.” Durr opens with five (5) “main characteristics of Deaf culture: language, behavior/norms, values/beliefs, tradition/ heritage, and possessions” (167). Durr also laments that “unfortunately a critical component of Deaf cultural possessions—art—is often overlooked or uninvestigated” (167). This current exhibit expands out from, and addresses, Durr’s lament as it intends to look over and deeply investigate the critical cultural possession of art for the not only the American Deaf community but also for the American arts community overall.

In 2016, SAGE publications produced the Deaf Studies Encyclopedia (Editors, Boudreault and Gertz). This groundbreaking publication included three different entries devoted to deaf art/artists: Art Genres & Movements (pages 40-42); Deaf Art (pages 149-165); and Deaf Professionals in American Art Museums; (pages 264-266). The Deaf Art entry (written by Wylene Rholetter) references many significant early deaf American artists who are not included in this exhibit: John Brewster Jr. (1766-1854), William Mercer (1765?-1839), George Catlin (1796-1872), Charlotte Buell Coman (1833-1924), The Allen Sisters (1854-1941), Theophilus Hope d’Estrella (1851-1929). Finally, in that encyclopedia, a rich and longstanding history of deaf people working in American Art Museums—written by Deborah Sonnenstrahl Blumenson—also outlines how deaf curators and museum workers have long been a part of creating accessible and alternative paths to accessing American art overall.

In 2005, the Rochester Institute of Technology/National Technical Institute for the Deaf (RIT/NTID) opened the Deaf Art website, substantially increasing the options for access to deaf art. Partly curated and reviewed but also somewhat “open-access,” the Deaf Art website maintains that “this site features over 100 Deaf and hard of hearing artists and numerous resources and materials” and indicated certain submission criteria. As an ongoing site of both public and educational engagement, the site currently features six main areas: Artists; Deaf Art; Students Self-Portraits; Articles; Videos; Resources.

New opportunities and elements for Deaf Art in America exist through several recent ventures in the last decade. In 2014, the Deaf Artists Residency Program (DAR) at The Anderson Center in Red Wing, MN was initiated, the only residency opportunity in the world devoted exclusively to Deaf artists. Running on a two-year cycle, the DAR has currently been through five cycles of artists-residents. Likewise, the Deaf Professional Artists Network (DPAN) has been thriving in the world of media/TV/ popular communications, including such things as fully sign-performed, artistic, lively pieces from the 2021 Super Bowl halftime show. That the Super Bowl, like several before it, also featured incredibly artistic performances—by deaf artists—for the Star Spangled Banner: most recently Christine Sun Kim in 2021 and Wawa in 2022.

Shadows and Absence

And yet, despite the 2021 Super Bowl spotlights, Deaf art and artists still reside in some shadows and absences. In preparing to do this work, I accessed half a dozen of the most popular textbooks in the history of American art. Deaf art was (Of course? Of course! Of course…) nowhere to be found in them.

It was also missing (with some alarm, some concern, some questions) from the important Through Deaf Eyes book that accompanies the two-hour PBS documentary film—though the film itself features some performance art and short film spotlights by deaf filmmakers.

American Art has always been critically challenged, and sometimes clearly troubled, with indicating and allying diverse identities related to the subject or production of the art. It’s an uneasy space, at best. In the fifteen years I’ve been working with James Castle’s art (in numerous ways), I have noted time and again how unsettled it can make curators, critics, the media, and the general exhibit-going audience to bring the question of Castle’s

Untitled, n.d. Soot, saliva, and color of unknown origin on found paper

3.5 x 6 inches (8.8 x 15.2 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

2021.12.001

There are a series of these box figure doll-like portrait images in Castle’s work. They all seem to evoke the classroom setting at the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind. They are created on found paper and (most) use color—which Castle sometimes created from colored pencils or from chewing down cartons and labels of colored materials (like ice cream cartons) and then re-applying that masticated material in his drawings. The smaller figures seem to represent other students at the school and the larger figure to the left, in green, seems to represent a teacher. Although Castle was only at the school for five years (19101915) it seems to have played a major role in his memory and his sense of friendship, sociality, and connection.

deafness to the center of the conversation. While his deafness was often used by critics and the media as a kind of spectacular spotlight to flash cleverly in a title, no one seemed to want to really talk or think about how Castle’s embodied deafness mattered in his art making and objects. As a counter to this discomfort over Castle’s deafness, I made it the central focus of my 2013 curated exhibit, Constructing James Castle, in the Columbus, Ohio Urban Arts Space; I carry that conversation comfortably forward even more directly in the 22-minute film, Constructing James Castle, I made about the exhibit.

As my former art education/art practice and disability studies colleague, John Derby, conveys in a groundbreaking piece about the intersections of art education and disability studies (2012), the crossings between art practices, art education, and deaf/disability studies are potent and prolific. In his 2012 essay, Derby proposes five ways that disability/deaf art practices can contribute to, intervene with, rewrite American art at large, because:

1. Art Addresses Identity

2. Art Practices Are Social, Cultural, And Critical

3. Art And Visual Culture Can Be Transdisciplinary

4. Visual Culture Is Narrative

5. Art Making Can Performatively Interact With Spaces As Tactics

The anxiety of identity that perhaps over-narrates the story of deaf art and

artists in America is no small thing to set aside; such anxiety can leave deaf artists and their art work in the shadows, absent. Instead of shadows and absence, this exhibit carries out Derby’s five proposed ways: it helps bring out the shape of American deaf identities; it shows the transdisciplinary potential of deaf art; it explores the visual-cultural-narrative in that art, and it demonstrates the dual performance of being deaf, being American in social, cultural, and critical spaces. Sometimes that shape is spotlighted and sometimes it is only shadowed in the art exhibited here.

When we access deaf art, as we do in this exhibit, we can begin answering those “seminal questions” Sonnenstrahl set out for us twenty years ago: “how do artists see their world, how do deaf artists interpret their world, how do deaf artists define their world, and finally how do deaf artists represent their world?” (xxiii)

Works Cited

Deaf Art, 9 August 2018, https://deaf-art.org/. Accessed 17 April 2022.

DPAN.TV – The Sign Language Channel, https://dpan.tv/. Accessed 18 April 2022.

“access-[ENTER-ENTER] / accessible.” YouTube, 23 June 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NNW5xUz_v9E. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Askins, Alice. “Deaf Artist Francis Tuttle.” Historic Geneva, 26 June 2015, https://historicgeneva.org/people/ artist-frances-tuttle/. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Boudreault, Patrick, and Genie Gertz, editors. The SAGE Deaf Studies Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications, 2015. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Brueggemann, Brenda. “Constructing James Castle | Urban Arts Space.” Urban Arts Space, https://uas.osu.edu/ events/james-castle. Accessed 18 April 2022.

Brueggemann, Brenda Jo, director. Constructing James Castle. Dandelion Pictures, 2013, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=PNuTZJ8OTYY. Accessed 18 April 2022.

“Cadwallader Lincoln Washburn.” Wikipedia, https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cadwallader_Lincoln_Washburn. Accessed 17 April 2022.

“Christine Sun Kim Performs the National Anthem / Super Bowl LIV.” YouTube, 3 February 2020, https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=c2TCT5HYlHQ. Accessed 18 April 2022.

“Deaf Art: De’Via.” Silent Voice, 9 February 2021, https:// silentvoice.ca/deaf-art-devia/. Accessed 17 April 2022.

“Deaf Artists Residency Program.” Anderson Center at Tower View, https://www.andersoncenter.org/residency-program/dar/. Accessed 18 April 2022.

Derby, John. “Art Education and Disability Studies.” Disability Studies Quarterly, https://dsq-sds.org/article/ view/3027/3054. Accessed 18 April 2022.

Eldredge, Bryan K., et al., editors. Deaf Studies Today! A Kaleidoscope of Knowledge, Learning, and Understanding: Conference Proceedings, Utah Valley State College, Orem, Utah, April 12-14, 2004.

Deaf Studies Today! American Sign Language and Deaf Studies Program, Utah Valley State College, 2005. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Gannon, Jack R. Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America. Edited by Laura-Jean Gilbert and Jane Butler, Gallaudet University Press, 2011.

Lang, Harry G., et al. Deaf persons in the arts and sciences: a biographical dictionary. Greenwood Press, 1995.

“National Anthem in ASL at Super Bowl LV.” YouTube, 8 February 2021, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=HRtDjTQHG-g. Accessed 18 April 2022.

“Oral history interview with Morris Broderson, 1998 March 11 and 13 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.” Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa. si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-morris-broderson-12187. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Sonnenstrahl, Deborah M. Deaf artists in America: colonial to contemporary. DawnSignPress, 2002.

Thompson, Vivian Alpert. A Mission in Art: Recent Holocaust Works in America. Mercer University Press, 1988.

Durr, Patti. “De’VIA: Investigating deaf visual art.” RIT Scholar Works, https://scholarworks.rit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1424&context=article. Accessed 17 April 2022.

Citizenship

Octavian Robinson Helen Dyer(Florida 1911 - 2001)

New England Village, 1960

Oil on canvas

22.75 x 18.75 inches (57.7 x 47.6 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

2006.03.002

Popular memory within deaf cultural communities and many historical narratives about American deaf cultural history begins in 1817 with the founding of the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in Hartford, Connecticut. The 1817 narrative is only part of a larger complex and multilayered history of deaf peoples in the United States. Historians have countered that deaf histories, signed languages, deaf cultures and communities existed prior to 1817; schools for deaf children were not a prerequisite for community formation. Deaf people, by genetics or by choice, would find ways to congregate. Enclaves of signing communities, due to intergenerational deafness in the local genetic pool, existed in places like Henniker, New Hampshire and Martha’s Vineyard off Cape Cod. Vibrant signing communities where deaf people were integrated into local communities were present before the founding of ASD. However, the 1817 narrative remains popular as the origins story of the deaf cultural community in the United States because schools intentionally brought together deaf people in sufficient numbers that a standardized language flourished, where political power coalesced, and deaf people’s integration in society was affirmed by the state.

As an origins story, the 1817 founding of ASD by Laurent Clerc, deaf Frenchman, and two hearing people, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Mason Fitch Cogswell, reveals much about the attitudes, values, anxieties, and tensions experienced by deaf people in the United States. The story emphasizes the importance of Gallaudet choosing to bring Clerc and the

French deaf educational method to the United States instead of the oral method that first brought Gallaudet to the Braidwood School in Scotland in search for a solution to a social and spiritual problem. The education of deaf children and their exposure to Christianity. The story also highlights Clerc’s adventurous nature and excellent negotiation skills. He negotiated a good salary for himself, secured his freedom to practice as a Catholic in Protestant America, and the means to return to France should Gallaudet’s venture not work out. Clerc, with Gallaudet and Cogswell, secured public financial support for the school, making ASD the first permanent school for deaf children in the United States. In short, the origins story emphasizes signed language as the right and moral choice, highlights language and education as central to deaf people’s agency, and reveals expectations for deaf people as citizens. Those tropes remain dominant in deaf cultural narratives into the 21st century. This origin story illustrates also the importance of schools for deaf children across the globe as cradles of signed languages, foci of deaf communities, and incubators of deaf political thought.

The modern standardized version of American Sign Language (ASL) is a product of the coalescing of regional and national deaf communities throughout the United States schools for deaf children, deaf organizations and clubs, and Gallaudet University along with broader changes in U.S. society such as the expansion of rail networks and urbanization. The early origins of ASL is traced back to ASD where Laurent Clerc brought Langue des Signes Française (LSF) to Hartford, teaching Thomas Gallaudet the language during their voyage to the United States. Clerc’s LSF combined

James Castle (Idaho 1899-1977)

Untitled, c.1930

Soot and spit on cardboard tea carton

3.5 x 4.5 inches (8.8 x 11.4 cm)

On loan courtesy of Rob Roth and John Berg

Castle’s drawings of the Idaho

School for the Deaf and Blind in Gooding are created from memory but all are astonishingly accurate. He attended the school from 1910-1915 (ages 10-15) and was sent home as “illiterate and ineducable.” Yet the importance of the school as a place of profound connection for him resonates through his many drawings. This drawing was made on recycled paper from his parent’s general store and done with soot (gathered from family and neighbor’s wood stoves) mixed with his own saliva and etched with his own self-made, whittled wood sticks. All of these elements convey Castle’s connection to his community and sociality. Castle almost always made his art from recycled materials. The soot and saliva drawing here was a medium he often used for drawings of the school and the local Idaho landscape at large. The medium of local soot and his own saliva on recycled paper conveys nostalgia, deeply embodied interaction, and a seeming direct simplicity.

Helen Dyer

(Florida 1911 - 2001)

Playing Checkers, 1961

Oil on Canvas

22 x 18 inches (55.8 x 45.7 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

2006.03.004

with the signed languages that the pupils at ASD brought with them from signing enclaves, Henniker and Martha’s Vineyard, home signs from home, and contact signed languages such as those learned from local indigenous populations. Those languages evolved together through use, growing through regional and national gatherings of deaf people in both permanent and temporary spaces such as schools for deaf children and biennial national conferences. Within half a century of ASD’s founding, regional and state associations and alumni associations, and many local deaf clubs were founded. By 1880, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) was founded, followed by the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf (NFSD), a national insurance company that also functioned as a social organization for deaf men, in 1901. Those organizations, clubs, schools, and later, factories with large numbers of deaf workers became critical sites of linguistic transmission and deaf political organizing.

However, many of those schools and organizations were not inclusive. Segregation in deaf schools, and especially the exclusion of Black students, were prevalent through the late 20th century. The NAD and NFSD both explicitly prohibited Black members until the mid 20th century; both organizations also had limited roles for women. Women, white and non-white, were also either excluded or highly restricted in access to beat organizations as communal linguistic spaces. Women, who otherwise satisfied the racial exclusion policies, were often welcomed into organizations to perform gendered labor like organizing social events, managing social relations and charitable service projects, and providing refreshments for everyone at meetings and events.

The growth of deaf communities organized around formal spaces and organizations meant that American Sign Language had brought together a unified linguistic community that encouraged habits of being and values centered on signed languages.

A common language allowed social and mutual aid communities to flourish. A common language also generated a space for cultural blossoming. A culture can be described as a habit of being in the world. A shared language in an uncommon modality meant a unique culture rooted in a different orientation to the world. This unique culture produced literary and artistic traditions that highlighted the beauty and value of ASL. This emphasis makes clear that signed languages are important, not only for communication, but representative of the value of language itself for agency and belonging.

Throughout this narrative about the development of ASL, deaf education, and deaf communities, the value of ASL is highlighted as the major overarching theme of deaf cultural history. Historically, signed languages have been an important political issue for deaf people. Since the early 19th century, deaf thinkers, writers, and political figures made the claim that signed languages were critical to deaf people’s agency and served as their best pathway to belonging as citizens.

Leaders of the National Association of the Deaf argued that education was important for deaf people’s status as citizens. First, the state’s investment in deaf education meant that society viewed deaf people as potential citizens. As citizens, they would be expected to participate in the workforce and in political discourse, be granted rights and freedoms like their hearing counterparts, and given opportunities for social advancement. They did

Portrait of Betsey White, 1939

Oil on canvas

30.5 x 24.5 inches (77.4 x 60.9 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth “Betsey” White 2006.11.001

Mixed media

22.75 x 26.5 inches (57.7 x 67.3 cm)

2006.03.008

not stop at this logic. Education alone was not enough. This investment was moot if the outcomes did not produce intelligent, independent, selfsufficient deaf adults. Leaders argued this education had to be accessible. For deaf children, this meant education in signed language, which would be fully accessible and serve as a pathway to English literacy, employment, and political power. Language allowed for deaf people’s agency as empowered actors and as active participants in the public sphere.

However, there was much pushback against signed languages in the 19th century rooted in racist, ableist, and colonial logics. Those ideas, combined with the racial hierarchy and gendered inequities in the United States, meant that deaf people encountered many attempts to eradicate the existence of deaf communities, cultures, and signed languages. This included efforts to close deaf schools, enact oral mainstream programs that isolated deaf children from each other, prohibit marriages and limit reproductive freedoms, and prohibitions on signed languages in deaf education. Language suppression led to language protectionism, which in turn meant ugly politics surrounding citizenship and worthiness. Who was worthy of belonging? Deaf leaders of organizations and signing schools were generally conservative in their politics.

Whiteness is largely unmarked in this essay because whiteness itself was a shifting category throughout the 19th century and early 20th century. At

times, some of the leaders of the organizations were not considered white by the standards of their time. This essay instead marks anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity when and where it appears to show the processes of the consolidation of whiteness within deaf political spaces. Essential to those discourses was the value of employment and self-sufficiency.

Deaf people were expected to work, avoid vagrancy, and be taxpaying citizens. Avoiding vagrancy specifically meant avoiding becoming public charges. A deaf person should not depend on society (or their local communities) for material support. Deaf communities formed mutual aid societies like the Ladies’ Aid Society of Chicago to provide support for deserving deaf people who might need community assistance. Those efforts were to protect the reputation of deaf schools as successes, especially those that used signed languages. Gainful employment and status as taxpayers lent deaf people legitimacy as contributing members of society. This perception afforded deaf leaders some degree of political power to advocate for deaf education, signed language, and civil rights for deaf people. Social pressures surrounding class, gender, and race meant the adoption of respectability politics, moral panics over the future of deaf children, and the reproduction of social structures within deaf spaces such as racism, sexism, and lateral ableism. For this reason, deaf organizations worked very hard to distance deaf people from other deaf-disabled people, shunned peddlers, outcast beggars, and often refused to advocate for equal educational access or civil rights for Black deaf people.

This vein of respectability politics continued throughout the 20th century and persists in the 21st. In the 1980s, when the AIDS crisis hit, deaf communities viewed the AIDS crisis as a gay problem mirroring much of American society. Public and sexual health education was not made accessible to deaf people who remain twice as likely to be infected with HIV, yet this remains a little discussed issue among deaf people. Which makes Harry Williams’ work even more so striking. Despite popular notions, it is a misconception to understand the deaf communities in the United States as monolithic. What the above illustrates is that even among this microcosm of American society, we find a group who reproduced, refracted, and maintained broader status quos. A close study of dominant strains of deaf history exposes ideas about worthiness of belonging and citizenship. The histories of deaf communities in the U.S. shows us how language functions as an axis for understanding the experience of power, privilege, belonging, and citizenship.

Harry Williams (Ohio 1948 - California 1991)

ABC ASL Peddler Card, n.d.

Oil on canvas

23 x17 inches (58.4 x 43.1 cm)

Gift of Malinda Mangrum

2021.09.024

Deaf peddlers are an iconic–and troubled and complicated–part of the American deaf community and history. Williams captures here the bleak and desolate background and the rising hope of the deaf peddler’s ABC card (for income, sociality, recognition in the larger hearing community and U.S. economy) that is pinned and floating above that starkness.

Educational Policies and Employment Opportunities

During the early nineteenth century, the United States experienced a period of reform movements. People reformed prisons, asylums, elder care facilities, and schools as part of the broader American narrative of progressivism. Prisons were touted to be rehabilitative of mind and spirit, encouraging meditation and repentance; asylums were established to care for those with psychiatric disabilities; homes for the aged boasted how Americans cared for the elderly; and schools for blind and deaf children were founded. Cast as exemplars of progress and modernity, educational institutions for deaf and blind children advertised innovative teaching practices and efforts to shape disabled children into productive American citizens. At the beginning, signed language was viewed as innovative, modern, progressive, a means for the deaf child to access spiritual salvation. Agrarian and craft based economies offered plentiful opportunities for employment for deaf people, especially as schools for deaf and blind children offered vocational training. As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth century, signed languages were framed as backward and regressive. Inventors invented technologies that were supposed to restore the facility of hearing. The valorization of medical authority superseded the lived experience and advocacy among deaf people to preserve sign language methods in education. Between the valorization of medicine, science, and technological progress, deaf schools stood little chance of missing the onslaught of cure and pathology. By 1920, eighty percent of deaf schools used oral methods. The development of a manufacturing economy, rising immigration, and urbanization also changed the employment landscape for deaf people. Deaf people were called into the factories in full force during wartime, proving their worth as patriotic worker-citizens but this show of loyalty and competency did not last beyond the war, although booming postwar economies provided some lasting benefit. Deaf people continued to grapple with low employment rates and barriers to higher education throughout the 20th century.

Frances Carlberg King (Florida 1913- 1997)

Kansas Farm, 1965

Acrylic on board

23.5 x 27.5 inches (59.6 x 69.8 cm)

Gift from the artist

1990.02.002

Francis M. Tuttle

(Geneva, New York 1839-1910)

Lodi Point on Seneca Lake, 1885

Oil on canvas

24 x 30 inches (60.9 x 76.2 cm)

On loan courtesy of Historic Geneva

Francis M. Tuttle was a renowned portrait and landscape painter from Geneva, New York in the Finger Lakes region at the end of the 19th century. His family was wealthy and well-established, dating back to the Mayflower. The paintings included here offer a sense of Tuttle’s skills at capturing his local Finger Lakes landscape and his portrait skills. In all of the work, scale is somewhat distorted, as certain elements appear considerably larger than others and suggest the painter’s visual attention to certain elements over others.

(Geneva, New York 1839-1910)

Wooded Lake Scene, 1882

Oil on canvas

17.5 x 24 inches (60.9 x 76.2 cm)

On loan courtesy of Historic Geneva

Francis M. TuttleFrancis M. Tuttle

(Geneva, New York 1839-1910)

The Steele Child, n.d.

Oil on canvas

35.5 x 29.5 inches (90.1 x 74.9 cm)

On loan courtesy of Historic Geneva

Francis M. Tuttle

(Geneva, New York 1839-1910)

Grace Walton Wheat, n.d. Oil on canvas

49.5 x 38.5 inches (125.7 x 97.7 cm)

On loan courtesy of Historic Geneva

Like John Brewster Jr., a hundred years before him, Tuttle was a deaf painter who gained fame and income through portrait (and landscape) painting. In this way, his portraits engaged sociality with the larger hearing American community around him. This portrait of Grace Walton Wheat is larger than life and intricately detailed while it also captures Seneca Lake behind her but out of scale with her own physicality.

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

Seaside in Maine, 1955

Ink & Pencil

19 x 27 inches (48.2 x 68.5 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Frances Carlberg King (Florida 1913- 1997)

Stilt Houses on Canandaigua Lake, c.1960

Watercolor on paper

10.5 x 13 inches (26.6 x 33 cm)

Gift from the artist

1996.02.012

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

The Fisherman, 1957

Watercolor on paper

19 x 19 inches (48.2 x 48.2 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

Boats in Maine, 1955

Watercolor on paper

27 x 22 inches (68.5 x 55.8 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

2006.08.001

22.25

1981.01.001

Chuck Baird (Missouri 1947 - Texas 2012)

(Top): Autumn Woods, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

25.5 x 31.5 inches (64.7 x 80 cm)

Gift of Robert Pratt

(Bottom): Down by the Roadside, 1982 Oil on canvas

x 26.5 inches (56.5 x 67.3 cm)

Gift of Robert Fergerson

Chuck Baird (Missouri 1947 - Texas 2012)

(Top): Autumn Woods, 1975

Acrylic on canvas

25.5 x 31.5 inches (64.7 x 80 cm)

Gift of Robert Pratt

(Bottom): Down by the Roadside, 1982 Oil on canvas

x 26.5 inches (56.5 x 67.3 cm)

Gift of Robert Fergerson

Igor Kolombatovic (Greece 1919 - California 2014)

Coastal Landscape (Mendocino, CA), 1974

Oil on canvas

37 x 41.5 inches (93.9 x 105.4 cm)

Gift from the artist 1990.04.001

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

Horse Barn in Winter, c.1965

Watercolor on paper

23 x 29 inches (58.4 x 73.6 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

The Illinois River, c.1965

Watercolor on paper

22 x 29 inches (55.8 x 73.6 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Kelly H. Stevens

(Texas 1896 - 1991)

River & Mountain in Texas, c.1930

Oil on canvas

21 x 27 inches (53.3 x 68.5 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Kelly H. Stevens

(Texas 1896 - 1991)

Texas Bluebonnets, c.1930

Oil on canvas

22 x 28 inches (55.8 x 71.1 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Untitled, c.1970

Watercolor on paper

19 x 23.5 inches (48.2 x 59.6 cm)

Gift of Jeanette Daviton

2015.02.001

Louis Francis Xavier Frisno (Maryland 1934 - 2020)David Mudgett (Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

Marshland, c.1965

Watercolor on paper

22 x 29 inches (55.8 x 73.6 cm)

Gift of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and James DeCaro Family

Jean Hanau

(France 1899 - New York City 1966)

Transportation, c.1930

Watercolor and graphite

20.5 x 18 inches (52 x 45.7 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.024

Harry Williams

(Washington DC 1959California 1991)

Untitled [Sinking Titantic], 1970

Oil on canvas

9.5 x 15.5 inches (24.1 x 39.3 cm)

Gift of Malinda Mangrum

2021.09.001

Deaf people have always been a part of history, but their stories are underdocumented, especially the stories of deaf people who were not straight white men. In Belfast, Northern Ireland in the 1900s, deaf shipyard workers gained access to employment at Harland and Wolff, a major shipbuilding company, through deaf activism. Deaf people were among the builders of the Titanic, which sank in the early hours of April 15, 1912. This, coincidentally, is also the date of Williams’ death from AIDS, almost 80 years later to the day, on April 15, 1991. Williams painted Titanic in 1970.

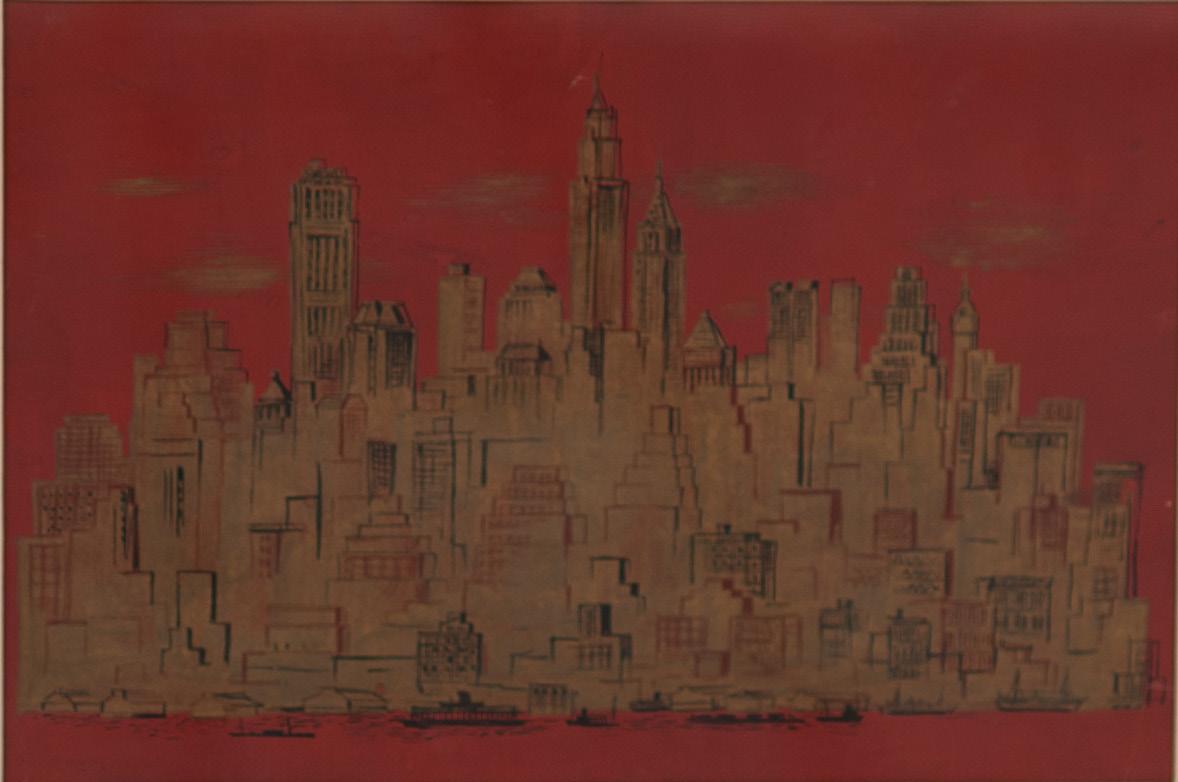

Jean Hanau

(France 1899 - New York City 1966)

Manhattan, 1930

Mixed media

14.5 x 18 inches (36.8 x 45.7 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.016

David Mudgett

(Wisconsin 1909 - Illinois 1991)

Cityscape, c.1965

Watercolor on paper

21 x 23 inches (53.3 x 58.4 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Jean Hanau (France 1899 - New York City 1966)

Male and Female Circus Performers, 1934

Oil on canvas

52.5 x 39.5 inches (133.3 x 100.3 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.003

Circus Performer Seated at a Table Approached by a Young Woman Carrying an Empty Bowl, 1954

Oil on canvas

52 x 38.5 inches (132 x 97.7 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.002

Igor Kolombatovic (Greece 1919 - California 2014)

Study of Nudes, 1978

Oil on canvas

30 x 36 inches (76.2 x 91.4 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.021

Jean Hanau

(France 1899 - New York City 1966)

At the Vanity, 1930

Watercolor and graphite on paper

17 x 15 inches (43.1 x 38.1 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.005

Fashion Illustration

Watercolor and graphite on paper

18 x 14 inches (45.7 x 35.5 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.010

Florence Ohringer

(Massachusetts 1914 - Florida 1981)

Woman’s Head, 1940

Oil on canvas

19 x 16 inches (48.2 x 40.6 cm)

Gift of Milton Ohringer

1979.03.002

Bubba, 1940

Oil on canvas

37 x 25 inches (93.9 x 63.5 cm)

Gift of Milton Ohringer

1979.03.001

Mary Thornley (Indiana 1950 - )

Self-Portrait, 1989

Charcoal on paper

24 x 19 inches (60.9 x 48.26 cm)

Gift of Tom Willard

2018.02.003

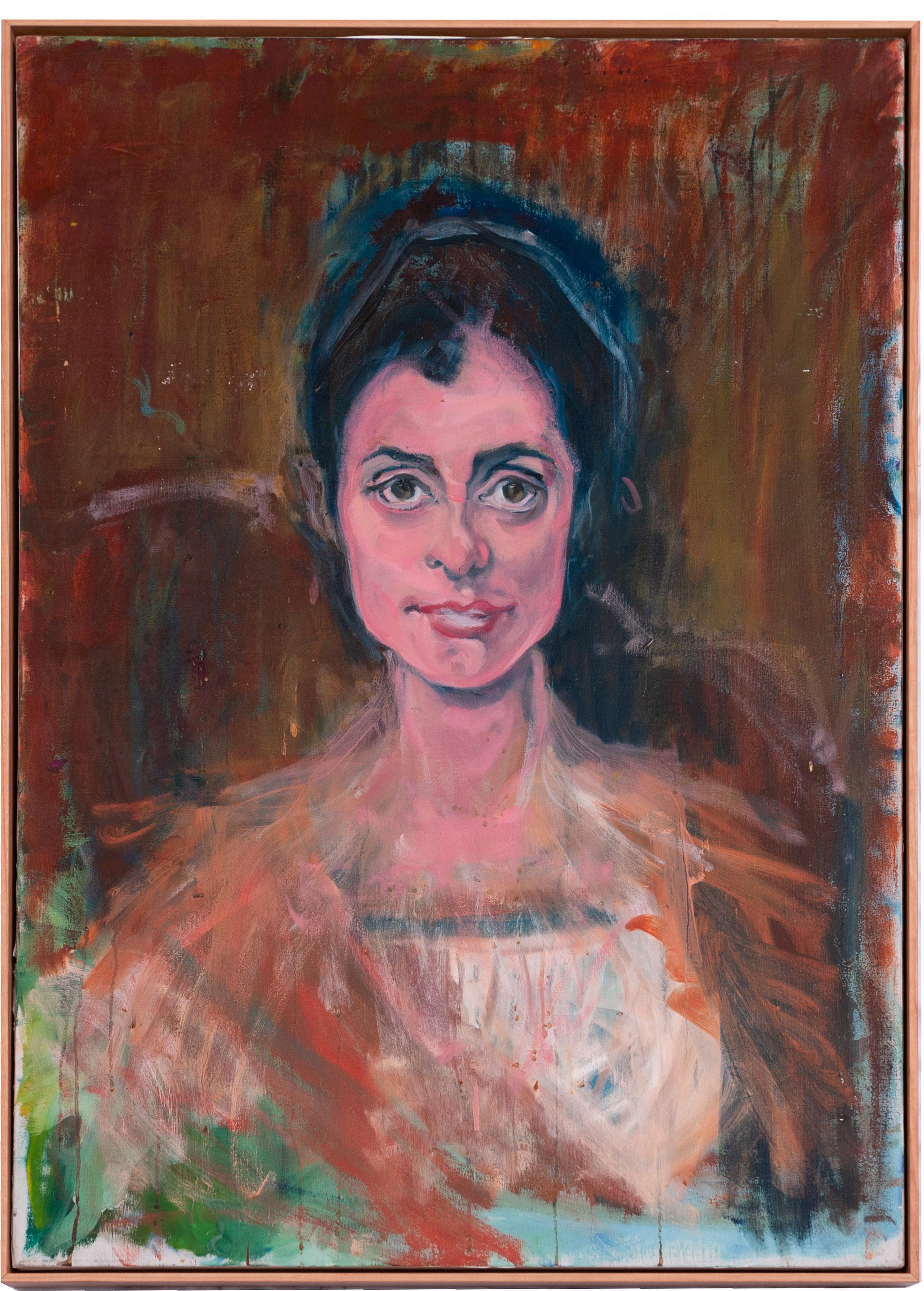

Igor Kolombatovic (Greece 1919 - California 2014)

Elizabeth, n.d.

Oil on canvas

42 x 30 inches (106.6 x 76.2 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.003

Jean Hanau

(France 1899 - New York City 1966)

Fantasy II, c.1931

Watercolor on paper

18 x 21.5 inches (45.7 x 54.6 cm)

Gift of Renate Alpert

2009.03.009

Robert “Ned” Edward Behnke (Washington 1949 - 1989)

Philodendron Lady, c.1975

Acrylic on canvas

55 x 52 inches (139.7 x 132 cm)

Gift from the artist

1976.02.001

Igor Kolombatovic (Greece 1919 - California 2014)

Foreplay of the Lovers, 1970

Oil on canvas

41 x 35 inches (104.1 x 88.9 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.002

Igor Kolombatovic (Greece 1919 - California 2014)

Mother and Her Baby, n.d.

Oil on canvas

40 x 36 inches (101.6 x 91.4 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.006

Helen Dyer (Florida 1911 - 2001)

Floral Still Life with Vase, 1962

Oil on canvas

20.25 x 16.25 inches (51.4 x 41.2 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

2006.03.001

Yellow Flowers, 1969

Acrylic on canvas

17 x 15 inches (43.1 x 38.1 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

2006.03.010

Helen Dyer (Florida 1911 - 2001)

Zinnias, 1962

Oil on canvas

16.25 x 20 inches (41.2 x 50.8 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

2006.03.11

17

Gift

Chuck Baird (Missouri 1947 - Texas 2012)

(Top): A Flower Stall in St. Gallen, Switzerland, 1982

Acrylic on canvas

x 23 inches (43.1 x 58.4 cm)

Gift from the artist 1982.01.001

(Bottom): Vegetable Stand, 1974 Oil on canvas

46 x 57 inches (116.8 x 144.7 cm)

Chuck Baird (Missouri 1947 - Texas 2012)

(Top): A Flower Stall in St. Gallen, Switzerland, 1982

Acrylic on canvas

x 23 inches (43.1 x 58.4 cm)

Gift from the artist 1982.01.001

(Bottom): Vegetable Stand, 1974 Oil on canvas

46 x 57 inches (116.8 x 144.7 cm)

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

Gifts from the Garden, 1984

Oil on canvas

25.5 x 20 inches (64.7 x 50.8 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

1984.01.002

James Castle (Idaho 1899-1977)

Untitled [Flicker and Flutter], n.d. White commercially printed paper with print on reverse (Saturday Evening Post), small rectangular pieces cut out and re-adhered in place 3 x 3.75 inches (7.6 x 9.5 cm)

On loan courtesy of Rob Roth and John Berg

Castle frequently rescripted pieces of text, although the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind records declared him “ineducable and illiterate.” This piece calls forward the image of the candles that deaf children frequently had to blow out as part of their oral training and the kinds of consonant clusters they would often be drilled to speak in.

Joan Popovich-Kutscher

(California 1951 - )

Hearing Test Different Way, 1985

Watercolor and colored pencil on paper

28.5 x 35.5 inches (72.3 x 90.1 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

2018.09.002

After the first eight years of her life were spent in an institution where she was assumed to be cognitively disabled, Kushner transferred to a deaf school where her symbolic etchings and and printmaking emerged under some guidance from her deaf art teacher, Felix Kowalewski. The symbolism of broken fences and lattices, tracks that don’t go anywhere, ties that barely bind or are disconnected, and broken frames with arrows and symbols on them that don’t quite connect characterize this piece and much of Kushner’s work. As a piece representing those broken connections and identities, Kushner also offers commentary on the overall disjunctive symbolism of hearing tests themselves.

Joan Popovich-Kutscher (California 1951 - )

Mrs. Lux with Me, c.1985

Watercolor and colored pencil on paper

20.5 x 16.5 inches (52 x 41.9 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

2018.09.001

(North Dakota 1906 - Missouri 1988)

The Learners, c.1975

Sculpture

5 x 5 x 5 inches (12.7 x 12.7 x 12.7 cm)

Following on the 1964 Babbidge Report to the U.S. Congress about the status of deaf education in America, oralism is coming under some threats. Here Arnold sculpts the intimate scene and close family circle of a deaf child learning to speak with their mother. The emphasis on her open mouth, their faces closely connected, the circular shapes, and their two hands joined at the child’s throat to feel voice vibrations conveys both the tenderness and vigilant attention needed to learn oral speech.

Newell Hillis Arnold

Newell Hillis Arnold

James Castle (Idaho 1899-1977)

Untitled, n.d.

Found board and wheat paste

3.5 x 6.5 inches (8.8 x 16.5 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

2021.12.001

All of Castle’s work is undated. This piece seems as if it is just a re-pasted cutout from a magazine but Castle often used images from popular culture and product material around his environment to cut and paste, and slightly re-alter the images so that they looked “true” to their sources but also, upon closer examination, revealed his own manipulations. He was adept at not only recycling but also practicing and presaging a later trend of “re-mixing” and “covering” already circulating material.

Untitled, n.d.

Found paper and wheat paste

2.5 x 4 inches (6.3 x 10.1 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

2021.12.002

Castle often played with letters and text in clever and critical ways—even though the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind (Gooding) sent him home at the age of 15, declaring him “ineducable and illiterate.” Here he seems to reference the “lasting qualities” of his own family name. While this drawing looks like type that might have just been cut from a newspaper or magazine, it has actually been re-cut, manipulated, and re-pasted by Castle himself in a kind of recycling of original material. Castle used recycled materials in almost all of his art.

Untitled, n.d.

Red, green and blue washes with soot and spit stick-applied lines on blotter

paper 4 x 9 inches (10.1 x 22.8 cm)

On loan courtesy of Rob Roth and John Berg

James Castle (Idaho 1899-1977)Nationalized Identity

The Civil War was bloody and rended the nation apart. People were wounded by the war of internal division and discord over the right to enslave people. Elsewhere, famine, drought, war, and religious persecution brought waves of immigrants from Asia, Southern and Eastern Europe, and Latin America. Between increased immigration [which represented competition for perceived limited labor and resources] and wounds of war, pressures amped up for people to assimilatethrough customs, norms, and language. Deaf people’s signed languages, once viewed as innovative, became suspect. Unamerican. Deaf people understood [but did they accept?] that, in order to obtain employment, they had to assimilate as English language users. Performative hearingness became an expectation, literacy in English acquired a new significance, and understanding that one’s categorization as white was what opened many doors to the American Dream, deaf people worked hard to achieve this by emphasizing their abledness of both mind and body, their literacy and intelligence, their conformity to dominant understandings of what it meant to be American. Deaf people were met with those expectations and pressure to embrace a nationalized identity. As the United States entered various military conflicts, from wars on the American frontier to wars across oceans- in Asia and Europe, patriotism often became a significant question and gatekeeping measure for employment opportunities. To preserve work and deaf education and participation in the public sphere, deaf people conformed to those expectations by being hyper patriotic, responding to calls for wartime labor, fundraising for military equipment, and engaging in racist campaigns to reject Others (foreigners, disabled people, and so on).

Igor Kolombatovic

(Greece 1919 - California 2014)

The Eagle Protects the USA FlagPatriotism, 1977

Oil on canvas

29 x 23 inches (73.6 x 58.4 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.037

David Ludwig Bloch (Germany 1910 – New York 2002)

Dachau Concentration Camp, 1977

Inkjet print

18.5 x 34 inches (46.9 x 86.3 cm)

Gift of Jane Bolduc

1995.03.005

The geometrical precision of the triangles in the lights—a Nazi symbol for prisoners of many kinds and identities—shine ominously in circles of light on the uniform lines of figures. While the Nazi triangles to mark “other” bodies always pointed down with the single point at the bottom (and two points at the top), Bloch inverts that triangle here. The play of shadows and light, linearity and uniformity, make the image into “still-life” as Bloch provides commentary on oppression, genocide, violence, difference and othering—all themes familiar in deaf history and community.

Cadwallader Lincoln Washburn (Minnesota 1866 - Maine 1965)

La Vieja, 1925

Etching on paper

15 x 12 inches (38.1 x 30.4 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

Vieja translates as “old woman” in Spanish though this etching seems to have been done from the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia during a 1925 scientific expedition where Washburn was sketching exotic birds. The simple, rough etching enhances the solidity of her figure and her direct, knowing gaze back at the artist who is also gazing at her. The portrait also demonstrates Washburn as a global, traveling, cosmopolitan citizen.

Cadwallader Lincoln Washburn (Minnesota 1866 - Maine 1965)

Bearded Old Man, 1934

Etching on paper

9 x 12 inches (22.8 x 30.4 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

The Shepard, 1965

Etching on paper

15 x 12 inches (38.1 x 30.4 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

Honor of Dead Bull, 1957

Watercolor and charcoal on paper

36.25 x 48 inches (92 x 121.9 cm)

1996.01.001

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

Japanese Man with Melon, 1954

Watercolor and charcoal on paper

48 x 36.5 inches (121.9 x 92.7cm)

1996.01.002

Frances Carlberg King (Florida 1913- 1997)

South Florida Scene 1, 1939

Watercolor on paper

20 x 24.75 inches (50.8 x 62.8 cm)

Gift of Perry O’Connell

1993.01.001

Frances Carlberg King (Florida 1913- 1997)

South Florida Scene 2, 1939

Watercolor on paper

21 x 24.75 inches (50.8 x 62.8 cm)

Gift of Perry O’Connell

1993.01.002

Igor Kolombatovic (Greece 1919 - California 2014)

North Beach Locals, n.d.

Oil on canvas

37 x 36 inches (93.9 x 91.4 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.008

Igor Kolombatovic

(Greece 1919 - California 2014)

Agonies of 1974 [Watergate], c.1974

Oil on canvas

48 x 33 inches (121.9 x 83.8 cm)

Gift of Elizabeth Kolombatovic

2019.01.004

Kolombatovic offers an interpretation of an important national event, the Watergate Trials, in this dramatic, dark painting that brings him into conversation with the national (hearing) identity. The eagle’s symbolic talons resonate with the ghost-white hand embracing the figure’s left shin. A swirl of dark clouds above the figure’s head then transforms into an angry and swooping eagle on the left. While the American flag is crumpled it is still vibrant and commanding in the image. The vibrant foot planted at the center of the work conveys both a sense of solidity and establishment while it is also attached to a leg that is folded in tightly, as if protecting the self. The contradictions of security and anguish in the image place Kolombatovic in conversation with a significant rupture in American culture and collective identity.

Deaf Sociality

Deaf sociality is based on networks, which are complex webs of social, economic and cultural relations that stretch and contract as deaf people move through spaces, physical and virtual. Deaf spaces and networks are diverse in that they can be permanent, temporal, precarious, historical, and contemporary. Deaf networks often involve deep, affective entanglements, which are deep feelings of connections and/or fractures that both drive and emerge from encounters between people, languages, and spaces. These affective entanglements shape the formations of deaf networks, as well as sustain the circulating of ideas, resources, and knowledge among deaf people. At different stages of their lives, deaf people circulate in different networks, encompassing different places and spaces. Dispersed, multiscale, and multiple forms of social spaces are central to the contemporary deaf lived experience; however, in the past, deaf people formed groups and clubs based on shared interests and political activity. Knowledge in the form of deaf histories and stories about specific people and places travel through networks and more recently, material resources in the form of support for local deaf artisans, deaf businesses, or charity, comprising the Deaf Ecosystem.

Guy Wonder

(Washington 1945 – California 2020)

Untitled, c.1969

Mixed media

21 x 17 inches (53.3 x 43.1 cm)

Gift from the artist 2018.13.001

Exotic stamps can be a way of experiencing the world in its expansiveness as a deaf cosmopolitan. Historically, exchanging letters was the foundation of transnational deaf networks. Writing, as with painting and drawing, is another modality in deaf languaging practices; however, it is also fraught because of perceptions that deaf people cannot write well.

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 – 2011)

Homage to Winslow Homer, c. 1968

Watercolor on paper

42 x 28 inches (106.6 x 71.1 cm)

Gift of Robert Baumgarten

1996.01.003

Broderson celebrates fellow watercolor painter Winslow Homer’s popular quote in watercolor washed rainbow hues that spotlight fingerspelling hands. While the long fingerspelled translation is tedious, it is also tender and flowing. The sexuality of both Homer and Broderson have been questioned and considered, but never definitively determined, in art history.

Helen Keller, c. 1973

Mixed Media

40.25 x 28.25 inches (102.2 x 71.7 cm)

Gift of Donna and Robert Davila

2006.12.002

In this portrait of Helen Keller, LaMonto paints Keller’s awakening to language— through sign language converses with the national identity and popular narrative of American culture. Using his technique of sequential figuration and engaging movement, varied direction, colors, contrasts of view, LaMonto paints Keller’s awakening to language. Set upon a grass/natural green background, Keller radiates ecstasy and perhaps a bit of being overwhelmed from the center of the work. Starting at the top of her head the smaller tighter fingerspelling communicates W-A-TE-R. Then emanating out in a fingerspelling circle-swirl that grows larger, more expensive (like the process of learning itself) the fingerspelled words surround her: D-O-G. C-A-T. F-L-O-W-E-R. B-O-O-K. H-E-L-E-N-K-E-L-L-E-R. L-O-V-E.

T-E-A-C-H-E-R. The handshapes are rendered in ghostly, spiritual white shade.

Frederick LaMonto (New York 1921-1981)

T-E-A-C-H-E-R. The handshapes are rendered in ghostly, spiritual white shade.

Frederick LaMonto (New York 1921-1981)

Henry Newman (Ohio 1929 – 2005)

Panorama, 1987

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 48 inches (91.4 x 121.9 cm)

Gift of Andrew and Teresa Newman

2018.05.001

The Quest for Knowledge, c. 1952

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.8 cm)

Dyer Arts Center Founding Collection

2001.05.002

A young student figure with intense, over-large eyes gazing ahead holds pen poised and page open with their left hand thoughtfully holding up their chin–in a classic scene of literacy longing, of beginning to write and express oneself. But there are no words yet on the page and only instead an empty cochlea-shaped shell figure placed near the left margin of the empty journal book before them. The pressure and desire to be a part of the hearing-literate culture, the isolation of education, and the intense but also empty gaze characterize much about the education of deaf children during this period in American history.

The Civil and Disability Rights Movement

Deaf people sought from the very beginning to participate in the American Dream that was promised them. The American Dream promised prosperity, freedom, happiness, and full participation in society as citizens (a promise that was explicitly not for indigenous peoples or enslaved peoples or their descendants). This participation meant economic security, freedom from government interference, and inclusion in the public sphere as political subjects. This promise was made explicit through the state’s investment in deaf education (signed or oral). Deaf people interpreted public support for deaf education as a two way obligation. Mainstream society owed it to themselves to see that their investment via tax dollars was worthwhile and deaf people owed taxpayers a return on their investment by becoming hard working, tax paying, law abiding, voting citizens. However, despite participating in the educational, economic, and political systems, deaf people found themselves on the margins, frustrated by the barriers presented by inaccessibility, lack of resources, and attitudes toward deaf people. Deaf people were not alone in recognizing that the American Dream was not attainable or open to all. Deaf people agitated for inclusion in the public sphere from the earliest days of the American republic; the founding of the National Association of the Deaf in 1880 and the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf in 1901 were both early disability rights advocacy organizations.

By the mid-twentieth century, many Americans on the margins organized to demand that the United States, in the context of Cold War politics and illusions of a perfect multiracial democracy, deliver on its promise of the American Dream. The 1970s and on witnessed a minority rights revolution where disability rights, deaf rights, women’s rights, queer rights, black and indigenous rights mvoements coalesced to expand inclusion in American society. While political participation was being contested, linguists and scholars were busy behind the scenes affirming that American Sign language was indeed a bona fide language and deaf people needed to be understood as a sociolinguistic cultural group.

This resulted in a more affirmative understanding of deafness and what we might understand now as Deaf Pride or deafhood. Riding this wave, the deaf rights movement crescendoed with the Deaf President Now movement in 1988, demanding that Gallaudet University, as the world’s sole liberal arts university serving deaf and hard of hearing students be led by a deaf person. After a weeklong protest, the students prevailed; a deaf president, I. King Jordan, was selected. This period inspired an affirmative acceptance of deaf identities, cultural spaces, and communities. A part of this was the De’VIA movement that celebrated deaf artists such as Chuck Baird and Betty G. Miller.

Betty G. Miller

(Pennsylvania 1934 –Washington DC 2012)

Spectrum: Deaf Artists, c.1991

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 48 inches (91.4 x 121.9 cm)

Purchased through the Permanent Collection Acquisition Fund

2008.04.001

Spectrum was established in 1975 as a Deaf artists’ colony in Austin, Texas, bringing together deaf visual artists, theater performers, writers, and dancers in an early example of what we now know as the Deaf Ecosystem, an ethos of cooperative capitalism. The replacement of the stars on the American flag with hands is an assertion of deaf citizenship and the sensual potential of deaf spaces.

Culture Shock, c.1989

Acrylic on canvas

35 x 47 inches (88.9 x 119.3 cm)

Gift of Brenda Schertz

2017.06.001

The tension in Culture Shock, inspired by Stout’s first time watching television with closed captioning, alludes to access friction and contradictory sensory orientations. A black and white photo is notched between an amorphous wash of blue with black streaks and a vivid yellow square within a black frame, suggesting tension between imagery and text with a monochromatic sensibility.

Marjorie Stout (Washington DC 1959 – )

Marjorie Stout (Washington DC 1959 – )

Marjorie Stout (Washington DC 1959 – )

Facets of Sound, c.1989

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 47 inches (88.9 x 119.3 cm)

Gift of Eleanor Shafer

2017.07.001

Harry Williams (Washington DC 1959California 1991)

17 x 13 inches (43.1 x 33 cm)

Gift of Malinda Mangrum

2021.09.029

In Three Naked Men, the nakedness of these running men, in contrast with their footwear and the pillowcases over their heads, hints at illicitness and concealment. But what is concealed is also celebrated in Over the Rainbow. This undated painting of a single foot treading on a sheet of music juxtaposed with the colors of the rainbow suggests several levels of representation and improvisation. It is a celebration of queerness and visual music as a repudiation of societal conventions regarding sensory and sensual orientations.

9.25 x 11.25 inches (23.4 x 28.5 cm)

Gift of Malinda Mangrum

2021.09.008

(Left): Three Naked Men, 1974 Watercolor and ink (Right): Over the Rainbow, n.d. Oil on canvasMorris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

Linda, 1981

Watercolor on canvas

45.5 x 35.5 inches (115.5 x 90.1 cm)

Gift of Joan Ankrum

1984.01.003

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

The Answer, 1982

Watercolor on canvas

34.5 x 45 inches (87.6 x 114.3 cm)

Gift of Joan Ankrum

2009.04.001

Morris Gayle Broderson (California 1928 - 2011)

Two Birds, 1982

Watercolor on paper

23.5 x 28 inches (59.6 x 71.1 cm)

Gift of Tsukuba University, Japan

1992.01.001

Cantata, 1985

Oil on canvas

32.25 x 42.5 inches (81.9 x 107.9 cm)

Gift from the artist

1993.02.001

James Canning (Pennsylvania 1942 - )Ralph Miller

(Illinois 1905 - Washington DC 1984)

Expressionless, 1981

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Gift of Nancy Creighton

2022.01.001

Chuck Baird

(Missouri 1947 - Texas 2012)

Untitled, 1989

Acrylic on canvas

33 x 50 inches (83.8 x 127 cm)

Gift of Richard Nowell

2014.06.001

Baird’s painting conveys a sense of surrealism in its juxtaposition of a ghost-like deaf body, complete with an FM-style hearing aid attached to the left ear. This ghost figure is set beside a field of mocking, advancing lips on a dark, foreboding background. The disembodied lips color connect with the ghost body’s FM system. The figure’s left ear with the aid in it turns toward the advancing lips, devoid of bodies, while its hands are overly large, somewhat distorted, and register a sense of surrender. The oppression and disconnection of self, rights, and language shadow the scene.

Black, Brown, and Indigenous Artists and Lack of Recognition

We cannot claim there is little or no art generated by black and indigenous people of color during the 20th century. There certainly were works generated and circulated. Rather, this section reflects the politics of dominant institutions. The RIT/NTID Dyer Arts Center’s collections are primarily determined by donations and purchases. Those who bought and accepted art for the collection likely sought out well known artists, and being well known depended on certain currencies (e.g. personal networks, connections, relationships with NTID itself, community acclaim). Mainstream deaf community discourses and political organizing was dominated by white deaf people. The leadership of national deaf advocacy organizations like National Association of the Deaf and National Fraternal Society for the Deaf were both dominated by white deaf men and women. Looking inward and to each other, this collection reflects back the values of the institution and its agents. And it is clear through the politics of this collection that the works of black, brown, and indigenous deaf artists were not valued.

John Louis Clarke (Montana 1881 - 1970)

Bear in East Glacier Park, MT, n.d. Wood sculpture

9 x 4 x 3.25 inches (22.8 x 10.1 cm x 8.2 cm)

On loan courtesy of the Patricia Mudgett-DeCaro and and James DeCaro Family

As the only known indigenous artist represented in this collection, Clarke’s rustic wood carved bear appears to be looking at, or for, something, leaning and listening toward it. Bears are known to have extraordinary hearing and yet little clear or far-range sight. The bear’s open stance is both engaged towards the world around it but also seems ready at defense.

Cover Image

James Canning, Cantata, 1985

Oil on canvas, 32.25 x 42.5 inches (81.9 x 107.9 cm)

Curators

Dr. Brenda Jo Brueggemann is a Professor of English and the Aetna Chair of Writing at the University of Connecticut.

Dr. Erin Moriarty is the Program Director of the Master of Arts in Deaf Studies Program at the Department of Deaf Studies at the School of Arts and Humanities at Gallaudet University.

Dr. Octavian Robinson is an Associate Professor of Deaf Studies at Gallaudet University.

Subsections

Dr. Erin Moriarty Deaf Sociality, 78

Dr. Octavian Robinson

Educational Policies and Employment Opportunities, 24 Nationalized Identity, 66

Civil and Disability Rights Movement, 84 Black, Brown, and Indigenous Artists and Lack of Recognition, 96

Interpretive Labels

Dr. Brenda Jo Brueggemann 4, 13, 18, 29, 60, 61, 63, 64, 69, 70, 77, 81, 83, 95, 96

Dr. Erin Moriarty 7, 22, 43, 79, 85, 86

Photography RIT/NTID

Graphic Design

RIT/NTID

Typeface

Granjon

Printed and bound in Rochester, New York