13 minute read

Flipped Learning

By Ross Corker Secondary Learning and Teaching Advisor Bangkok Patana School

Bangkok Patana School is committed to developing students who achieve their full potential as independent, motivated and engaged learners. Our staff continuously strive to enhance their own professional learning; working collaboratively to develop and practise a diverse range of learning and teaching strategies. One such pedagogical approach is that of Flipped Learning, a model which enables students to foster their critical thinking and collaborative skills.

What is Flipped Learning? Flipped Learning is a learner centred model, which ‘flips’ the more traditional idea of a teacher telling the students what they need to know or providing them with information. Students are more active in their learning; they are given materials and tasks prior to a lesson and asked to work through these independently as Home Learning. Students may read materials or watch clips or tutorials outside of class. Students are encouraged and challenged to discover key concepts, or broaden their knowledge, of a particular topic themselves, facilitated by the materials or guidance from their teacher. The concept of Flipped Learning goes back to the 1990s, but the phrase came into more popular use in the mid-2000s following the work of two Science teachers, Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams.

“Flipped Learning provides students with predictable, manageable, achievable and valuable Home Learning, leading to lessons which are immediately engaging and challenging,” said John Burrell, Secondary School Biology teacher.

Flipped Learning in Action There has been a renewed focus due to the positive effects it has on Home Learning routines and in supporting greater progress and challenge during lessons. Across Bangkok Patana’s Secondary School,

Flipped Learning provides dynamic, engaging learning opportunities for students in a range of subject areas. Teachers are looking at a variety of ways to deliver Flipped Learning, including asking students to look at pre-lesson content and using technology which allows students to pause, rewind and repeat videos at their own pace.

“For me, Flipped Learning is about maximising the face-to-face time I have with my students. By asking them to carry out learning that requires lower-order thinking skills before the lesson, it means we can move on to the more challenging, higher-order thinking skills when we are together in class. This leads to more insightful discussions, a wider range of critical, inquisitive questions, and it essentially accelerates the learning in a supportive environment,” said Lindsay Tyrrell, English teacher.

Students in a Drama lesson were set the Home Learning task to remember and practise a monologue. During the lesson students began performing almost instantly. Instead of having to spend time learning the lines in class, students burst into a performance of energetic and dynamic monologues. This maximised the time in class for students to develop and refine the vital performance skills required for their assessment and allowed the teacher to spend more time providing individual formative feedback.

Students in Mathematics watched a video for Home Learning, which gave them the opportunity to gain the knowledge and understanding of Key Formulae required for the lesson. One student said, “After watching the video I understood the methods and felt confident applying some of the formula, but still had questions about some aspects of the methods. By completing the ‘consolidation task’ I felt more confident completing harder questions at a later point in the lesson.”

Last academic year, a number of staff explored ways to develop their own knowledge and expertise of Flipped Learning. This included a cross-faculty Home Learning party, Career Professional Learning sessions and the Secondary School Teacher Learning Communities.

“I creatively flipped the teaching of Twelfth Night, a lengthy Shakespeare play, asking students to research the plot and characters before producing their own plot summary in a format of their choosing. The results were fantastic and included videos, Twitter feeds from the characters, storybooks and a flip book. More importantly, the students were really enthusiastic about the task and clearly relished the opportunity to show off their talents and skills,” reported English teacher Hannah Davis.

This year Bangkok Patana School will continue to develop our understanding and application of Flipped Learning and continually review the impact that it is having on students’ progress and attainment.

EdThought

Coordinator’s Reflection: A Three-Year Journey of Explicit Approaches to Learning Instruction

Matthew Baxter, PhD Archive, Research and Collaboration Coordinator Hangzhou International School, mbaxter@his-china.org

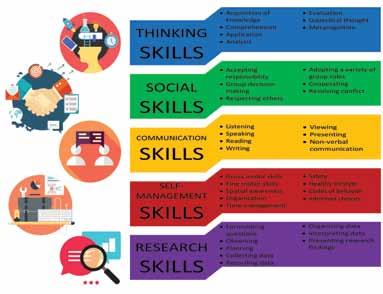

The purpose of the IB’s Approaches to Learning (ATLs) is to improve student outcomes. When considering this purpose, the first question that comes to mind is, “How?” When it came to the implementation of ATLs at Hangzhou International School, we decided to deliver the curriculum by any and every means necessary. The International Baccalaureate requires that IB Schools cover ATL skills in all subject areas. Explicitly teaching ATLs to every student in the Middle Years Program (MYP) via a designated course is not required. This leads us to ask the question, “Why not?” The feedback from universities and industries all over the world is that these are the skills students seem to be missing and the skills they will need for the future of work (World Economic Forum, 2018; Schleicher, 2015).

Explicit instruction of ATLs raises the standards of student learning across all subjects and disciplines, in addition to student improvement in the skills taught. HIS decided to create a course in the MYP dedicated to the instruction of the five main ATL domains: Self-Management, Communication, Research, Collaboration, and Thinking. This approach is not meant to replace implicit ATL acquisition in other classes, but to be the transdisciplinary glue that aligns the progression toward mastery of these skills. ATL class also provides support for what is happening in other courses.

In ATL class, students’ long-term and short-term projects help them work toward mastery of the five domains. These projects are based on student passions and develop proficiency in thinking and learning skills. Students synthesize their knowledge to apply ATL skills across all school subjects and into their lives outside of the classroom. This process has demystified who is responsible for ATL skill acquisition by placing the responsibility onto the student, with teacher coaches and administrator support. Now, imagine you are a student in school. Think about your daily or weekly routine. What are some things that you control? As you go through a long list, you may perceive that many behaviors, traits, and skills are out of your control. This may leave you feeling helpless. According to Martin Seligman, “Learned Helplessness” is embracing negative inputs because past events have demonstrated that you are helpless to change an outcome (1972). ATL class develops tools, techniques, resources, and skills that combat specific instances of Learned Helplessness. The objective is to empower students to understand that control and change are possible.

We know that control over our behaviors, traits, and skills is attainable because of research regarding the Growth Mindset, including that of Carol Dweck and others. According to Lance King, an expert on ATLs and Growth Mindset, “Control over the quality of your own output is absolutely necessary for both intrinsic motivation and high performance. The world outside of school demands the acquisition of ATL skills as what is needed most from college graduates” (2018). At HIS, we are working to meet that demand by developing ATL class. In class, student autonomy is promoted through teaching toward the mastery of skills. Students define the purpose of the skills needed, so they not only succeed in an academic setting, but have success beyond the classroom.

In short, students have command over their Approach to Learning. This is important because “today’s economy no longer rewards people simply for what they know--Google knows everything-- but for what they can do with what they know” (Schleicher, 2013). ATL class directly teaches how much effort students need to apply in order to take control over their learning and acquire the full spectrum of the ATL indicators listed below.

Self-Management Research Thinking Collaboration Communication

-Affective -Information Literacy -Creative Thinking -Interpersonal Information -Literary Skills

-Reflective -Media Literacy -Critical Thinking -Social and Emotional Intelligence -Verbal Skills

-Organizational -Ethical Use of Information -Transfer Thinking -Information and -Non-Verbal Skills

Communication Technologies

Students buy in to ATL class because we focus the units on giving them control over their success. Students who feel that they have a purpose, are provided with an unobstructed pathway to achieve, and believe that anyone can gain talent with a bit of effort, are those who succeed (Dweck 2007; King 2018). This understanding goes beyond ATL class and should be supported by the whole school community. At HIS, we promote ATLs through cross-curricular activities, engaging students in every subject. We go beyond the classroom by informing the community of student ATL expectations, communicating what is happening in ATL class to all stakeholders, and focusing professional development on ATLs.

We have many measures to gauge success in this program, including anecdotal observations, qualitative feedback, and honor roll recipients. The most compelling quantitative data is in the form of a yearly ATL diagnostic survey that students Grades 7-12 complete. This data is pushed out to all instructors and student support specialists, not just ATL course teachers, to help find the gaps in proficiency and bring students to mastery. Over the past three years, since the inaugural ATL class, a steady increase in self-reported ATL proficiency has been observed.

The first year the program was implemented, the ATL diagnostic assessment helped us build the four units that now make up the core of the program. Our team specifically looked at deficiencies and decided to begin each grade level with a self-management unit, the lowest-performing self-reported skill. The self-management unit focuses students on planning, reflecting, and setting goals for their learning, as well as organizing their computer and classroom folders. After the first unit, Grades 8 and 10 focus on their Community and Personal Projects for the remainder of the year. The ATL instructor gives class time for the MYP Projects while directing lessons toward ATLs that address the needs of the year-long projects. Grades 6, 7, and 9 move from self-management to their communication unit, focusing on media and information literacy, ending in an oral presentation on topics students feel passionately about. Students use comprehension skills to analyse a variety of media on their topic. Their next unit, research, begins by selecting a passion-based theme. Students then acquire strategies to find and evaluate information to write an argumentative essay. The final unit is the social unit, where students work together to create a film for the Hangzhou Student Film Festival. In this task, the assessment focuses on how well the students work together, not on the quality of the film. We end the year for Grades 6, 8, and 10 with formative tasks based on scenario planning, puzzles, and thinking games while Grades 7 and 9 begin their MYP Project journey.

ATLs are inclusive and comprehensive enough that a course in ATL acquisition would benefit any school and any student, no matter the curriculum. This 21st Century skills program can be the soil that grows the skills of a 21st Century learner. It can be a constant in a child’s schooling and beyond into their career. Once you have an ATL class in place, a discussion about methods will undoubtedly arise. Things to consider will be implicit versus explicit teaching, assessment methods, reporting, and feedback. Schools should consider the implications and research surrounding these topics and design the best program to fit their community and support their students in becoming successful life-long learners.

References

Dweck, Carol. (2007). Mind Set: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY. Ballantine Books.

King, Lance G. (2018). The Future of ATL. Notes from the IB Heads and Regional Conference, Republic of Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.taolearn.com/ approaches-to-learning/

Schleicher, Andreas (2013). Lessons from PISA Outcomes. Observer OECD. Retrieved from http://oecdobserver.org/news/fullstory.php/ aid/4239/Lessons_from_PISA_outcomes.html

Schleicher, Andreas (2015). The well-being of students: New insights from PISA.

EduSkills OECD. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/pisa 2015-results-volume-iii-9789264273856-en.html

Seligman, Martin E. P. (1972). Learned Helplessness. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The Future of Jobs. Centre for the New Economy and Society. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/ docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2018.pdf

Community Service

IGB International School’s Race Against Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery

24 Hour Race Kuala Lumpur 2018, held at IGB International School

By Julie Chen Arcidiacono, Community Services & Support Coordinator IGB International School, Malaysia, julie.arcidiacono@igbis.edu.my

For the fourth time within our school’s six years of operation, IGB International School has hosted the 24 Hour Race Kuala Lumpur. Each time, we have welcomed over 1000 students from around 40 different schools to our lush green campus in Sungai Buloh, Malaysia. The 24 Hour Race is the largest student-led movement to abolish modern-day slavery in the world, and it all stemmed from a philanthropic vision that a student in Hong Kong had back in 2010. Today, student teams across the globe compete in endurance relay races over the course of 24 hours to raise awareness and funds to stop human trafficking. Funds raised through these races support antislavery NGOs. This year alone, races have been held in Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Tokyo, San Francisco Bay Area and New York.

Hundreds of students who are interested in being involved with the movement as part of the 24 Hour Race Organising Committee, undergo a rigorous application process and are carefully selected nearly a year before the event. As a member of the organising Committee, they are fully engaged in social entrepreneurship and are tasked with coordinating the logistics of the event, its planning, preparation and execution. Several of our own students have been—and are currently—actively involved with the 24 Hour Race as runners, volunteers and most commendably, as organising Committee members. Last year, Esha Mardikar, one of our Grade 12 students, acted as the Executive Director for the 24 Hour Race Kuala Lumpur, the largest of all such races, raising over MYR 200,000.

According to Esha: “On a local scale, Malaysia is, unfortunately, a hot bed of human trafficking. As a major transportation hub and one of the more developed nations in the South East Asian region, Malaysia sees a lot of human trafficking activity, be it as a transit hub or as a final destination. Sadly, many are still unaware of the plight of these victims.

“This is what the 24 Hour Race movement hopes to address. The movement has allowed students to find their voice while taking the initiative to lead the fight against human trafficking.”

Our most recent hosting of 24 Hour Race Kuala Lumpur was on 23 November 2019. The figures were equally impressive. Nearly 70% of our Grade 9-12 students were actively involved with the event, as was the rest of our student body. In anticipation of the event, children as young as 5 years of age participated in our school’s version of the 24 Hour Race, namely the 24 Minute Race. Students from grades 1 through 12 joined together in 24 minute relay races and parents were invited to watch and cheer on their children. The trickle effect was massive, as our student members of this year’s organising Committee were able to raise even more awareness of the movement with community members beyond the Secondary School.

Run it. Raise it. End it. These six words have been the driving force for the 24 Hour Race and have certainly become part of our school’s identity. Its impact has reached beyond imaginable levels, as our student organizers, our leaders of tomorrow, have proven over and over how much can be gained when we apply our collective efforts to tangibly impact society in such a positive way.

Middle School Art Celebration

American International School Hong Kong