12 minute read

Reflecting on All At Once

Reflecting on

On view through Sept. 26, 2021, All at Once: The Gift of Navajo Weaving showcases 46 exquisite textiles from contemporary Navajo weavers. All at Once has been made possible by the generous donation of longtime Heard Museum members and supporters Mark and Julie Dalrymple (see page 22 to read an article from Julie). These textiles, plus dozens more, now reside in the Heard Museum’s permanent collection. Also featured throughout this exhibition are artist statements from leading Navajo weavers including Marlowe Katoney, Marilou Schultz and sisters Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete.

All at Once was curated by Dr. Ann Marshall, Director of Research, in collaboration with Velma Kee Craig, Assistant Curator, and the Andrew W. Mellon Fellows: César Bernal (Chicanx), Roshii Montano (Diné) and Ninabah Winton (Diné). Continue reading for personal reflections from Kee Craig and the Mellon Fellows about their time creating and curating this exhibition.

VELMA KEE CRAIG | ASSISTANT CURATOR

At the end of 2019, the Heard Museum received a large donation of textiles from Mark and Julie Dalrymple, collectors and longtime Heard supporters. At that time, I was midway through my third season as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow. I remember the excitement as the 2019-2020 Fellows and I first encountered the nearly 90 textiles as they lay stacked in neat piles on tables in the museum basement. We dove immediately into surveying each individual textile, in complete awe of the diversity of styles represented in this batch of weavings. As we laid out each textile for the team to discuss, one of us would read aloud the accompanying information, beginning with the assigned ID number, weaver’s name, the title of the weaving (if the weaver had given it one) and the type of design. Having this information to accompany the textiles was such a treat for us. Two of us, Ninabah Winton and I, had just wrapped up working on the exhibition Color Riot! How Color Changed Navajo Weaving, in which all but the handful of textiles included in the “Still Rioting” or contemporary section of that exhibition were woven by people whom we labeled as Unidentified Artists. Time and again, we heard ourselves express out loud how we wished we could reach out to the makers of these masterfully woven Transitional-era textiles to get insight into their process, their design inspiration(s), and the story or meanings behind the design or included elements—or even just to know who the weavers were and what region they called home. With this new batch of donated textiles—the Dalrymple Collection—we recognized immediately the opportunity we had to center the weaver’s voice in the upcoming exhibition, and we began reaching out.

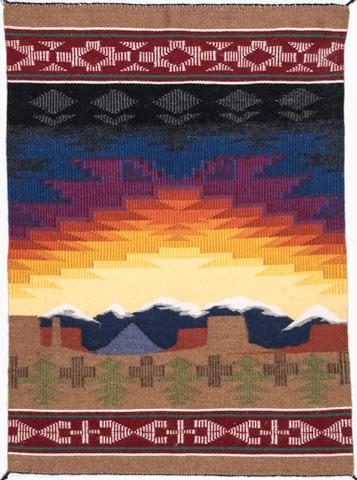

Elverna Van Winkle (Diné), b. 1968, Revival textile, commercial wool, aniline dyes. Collected in 2013. Gift of Mark and Julie Dalrymple, 4951-15.

One of the more memorable conversations I had was with weaver Elverna Van Winkle. For Van Winkle, weaving allowed her a freedom to “pick up and go anytime and take work with me.” The most exciting part of the weaving process for her is seeing the design come to life on the loom, as she believes it is for all weavers. We also talked about her late grandmother, Nellie Joe, who taught Van Winkle to weave when she was just 6 or 7 years old. She became emotional when she relayed to me her grandmother’s words, “You should always have a rug set up and on the side to fall back on,” and expressed the gratitude she felt at knowing she has been able to fulfill this wish.

It’s hard to narrow down my choice for “favorite” textile, but I’ve settled on Salina Dale’s impressive and exciting reinterpretation of the classic Two Grey Hills design. Dale’s version has the central diamond medallion turned inside-out or rearranged so that it is instead four triangles pointed toward the center to create an X. At the age of 86, Dale is a master. Her textile and her dissection and reinvention of an age-old classic Navajo design bring me joy.

CÉSAR ESTEBAN

BERNAL | ANDREW W. MELLON FELLOW AND CO-CURATOR

When stepping into museum spaces, what intrigues me the most—besides my interest in what is being exhibited—is the question “How did this come to be exhibited?” This curiosity of mine was satisfied as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Heard Museum helping with putting together All at Once: The Gift of Navajo Weaving. It was exciting to walk into the workroom for the first time this past October, seeing the entire collection rolled up, and going through each and every textile as we unrolled them and discussed where they could go in the exhibition. Everything up to the point of hanging the textiles on the gallery walls, from learning about the process in conceiving this project to preparing for installation, was exactly the knowledge I was missing when walking into exhibition spaces before.

As I had the opportunity to closely look at every textile, I grew fond of one in particular. A cornstalk pictorial by Charlotte Begay quickly stood out to me. What I really admire about this weaving, and what caught my eye first, is the attention to detail that is placed into the illustration of the birds that line both sides of the cornstalk. Compared with other representations of birds in weavings, these are finished with a more realistic touch. You can see where each feather on the wings and tails of the birds starts and ends. Every bird has its own distinct color markings, and that one thread of yarn that comes up for the eyes brings each of them to life. The cornstalk also has a dimension to it where you can see the depth of the space with the leaves extending back and to the side; it is not merely lying flat. Through viewing it more, the weaving takes the form of a digital rendering in my eyes, as the color shifts become pixelated. This is definitely a favorite of mine among a collection of great works.

Michele Laughing-Reeves (Diné), b. 1971, Canyonland Flight, 2015. Handspun wool, commercial wool, cochineal dye, indigo dye, vegetal and aniline dyes. Gift of Mark and Julie Dalrymple, 4951-56.

NINABAH WINTON

| ANDREW W. MELLON FELLOW AND CO-CURATOR

Working on All at Once has been very different from our work on our last project as Mellon Fellows (Color Riot!, 2018).

For parts of 2020 and throughout the process, working on this exhibition has meant working from home, researching and sourcing information—calling and emailing weavers, trading posts, and galleries—while also enduring the doldrums of the pandemic at the same time.

When we did return to the museum, meetings and discussions on the textiles were very different, of course. During textile review sessions, we were unable to fully lean in and huddle over shared magnifying glasses as we once had; we weren’t always able to hear every word of each other’s insights beneath masks and face shields; the exhibition installation was much less populated; and all of the accompanying programming has been moved online.

The whole experience has made me acutely homesick and longing for a place I can’t be right now. For that reason, I find myself drawn to two textiles within the exhibition in particular that evoke a very strong sense of time and place: Canyonland Flight by Michele Laughing-Reeves and a pictorial textile by Angelena Jackson.

Each reminds me of a place I know—climbing amongst canyon bluffs, committing the colors of a landscape to memory, or even the warmth of home after a much too hectic day of sheepherding. Ahxéhee’ to all of the weavers for sharing their visions and works with us.

I joined the Heard Museum through the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship in early October, after graduating with my B.A. in art history from Stanford University. It has been a bizarre experience having to enter the fellowship during a global pandemic. Even though I’m new to the museum, I think that, no matter our experience, many of us have had to overcome similar challenges. There had already been a lot of work done on the exhibition before I was introduced to the project. I’ve never co-curated an exhibition of this scale. Working on All at Once: The Gift of Navajo Weaving was truly a unique and collaborative experience. I honor the knowledge that I’ve gained from this project—working closely with the weavers’ work, their personal statements, and the discussions that arose within the curatorial team.

It’s difficult to pick a favorite piece from the exhibition. When you’re in the room with the other curators thinking about the story you’re trying to tell or themes to bring out, you advocate for certain works to be included in the exhibition. I learned from this process that I developed an attachment to a few select works, one of those being the Ye’ii pictorial textile by Aurelia Joe. There’s an otherworldly, space-like aura that emanates from the landscape that the representational Ye’ii figures inhabit. Multicolored stars are speckled across the sky in colors red, yellow, blue, green and purple. The atmosphere Joe created in her work exemplifies the innovative essence that stands out in contemporary Diné weaving. When I get a quiet moment at the museum, I’ll walk into the Jacobson Gallery to look at the textiles hanging on the walls. I always look to find something new.

BY JULIE DALRYMPLE

Julie and Mark Dalrymple with Lynda Teller Pete.

My late husband Mark and I enjoyed traveling to places with great scenery, especially the Pacific Northwest and the Southwest. And we liked to bring home things that reminded us of our trips: honey, cheese, fabric for shirts for Mark, and beautiful things that would look nice in our house. We gathered Northwest Coast carvings, Zuni fetishes, Navajo silver seed pots and jewelry, a little Pueblo pottery, a few Inuit masks and some Navajo sandpaintings, along with Navajo rugs. We really liked three-dimensional, useful work.

We had a few miscellaneous art pieces in 1989 when we made our first trip to the Southwest and bought our first rug (and then two more), along with four pottery storytellers, a sandpainting and a Zuni fetish. That first rug, bought at Garland’s, was woven by Helen Walker from hand-spun, hand-carded wool. It has a wonderful texture as well as design. I still have it.

We had already developed an appreciation for Northwest Coast nations’ art (starting on our honeymoon in 1969), and I think the same strong design elements connected us emotionally to Navajo weavings. So we continued trips to the Southwest and Northwest and continued to find art that appealed to us. In 2005 we went with friends to our first InterTribal Indian Ceremonial in Gallup. High on the wall was the First Prize and Best in Category, a hand-spun and vegetable-dyed rug by Mae Jean Chester. We asked them to take it down. I think it was the first rug that made me think about the person, the artist, who wove it.

Helen Walker (Diné), Storm Pattern textile, 34 x 51 1/2 inches.

We began to realize the work and artisanship that go into the best rugs. Mark was a recording engineer for the Music Department and the Memorial Church at Stanford University, and he built a lot of equipment for them. I was a librarian for the Santa Clara County library system and sewed and made beaded jewelry. As makers ourselves, both of us appreciated good design and attention to detail. We also developed a few quirks: Mark loved rugs with trains and didn’t like pictorials with stylized perspectives. I liked a few rugs mostly because I loved the colors used, but neither of us liked too-bright colors. Somehow our tastes were very similar, making it all too easy to find rugs we could agree on. However, we had a three-bedroom house with normalheight walls (and cats), so we wouldn’t buy rugs that measured longer than 5 feet vertically.

In 2011, we first bought rugs from the Heard Museum Shop, visited trading posts on the reservation, and bought a rug online (also from the Heard Museum Shop). We first attended the Crownpoint Weavers Auction and the Santa Fe Indian Market in 2012. By the end of that year we had 43 rugs. Once we started online shopping, we discovered Steve Getzwiller’s Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, so we bought a first rug online and then visited in 2013. Steve’s expertise and relationships with the weavers taught us a lot about Navajo weaving. Mark and I were both introverts, pleased to meet weavers and hear what they had to say, but shy about asking questions or talking about much beyond how we admired their work, so the relaxed setting at Nizhoni appealed to us. We also visited our first Heard Indian Fair & Market and our first Hubbell auction that year. We were happy that buying contemporary weavings helped support the weavers and the continuation of a cultural tradition. And we filled our house with beauty.

Sometime that year we ran out of space on our walls. What to do? I suggested that if we called ourselves collectors, we could buy more rugs and rotate them on the walls. Yay! Until 2017, we continued trips to shops, auctions, trading posts and markets. When Mark fell ill, we could no longer travel, but it was wonderful that he and I could continue to collect by shopping online. We had talked about what to do with our collection, as no one in our families shared our interest. Because we had enjoyed visiting and shopping at the Heard Museum and taking trips with the Heard Museum Guild, we decided that we would like to offer much of our Southwestern art to the Heard Museum. Fortunately, they accepted. I kept some of my favorites, although I do plan to leave them to the museum in my will. I’ll just share two more of the rugs I still have. The first (from the Heard Museum Shop) is a train pictorial rug by Florence Riggs that I hung where Mark could see it from his sickbed. The second is a sunrise pictorial by Bobbi Jo Whitehair that lifted my spirits during those dark days and still does today.

Florence Riggs (Diné), First Phase Chief/pictorial textile, 39 x 48 inches.

Bobbi Jo Whitehair (Diné), pictorial/raised outline textile, 24 x 34 inches.