76 minute read

n Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues

Back Issue Bonanza

by Margaret D. Bauer, Editor

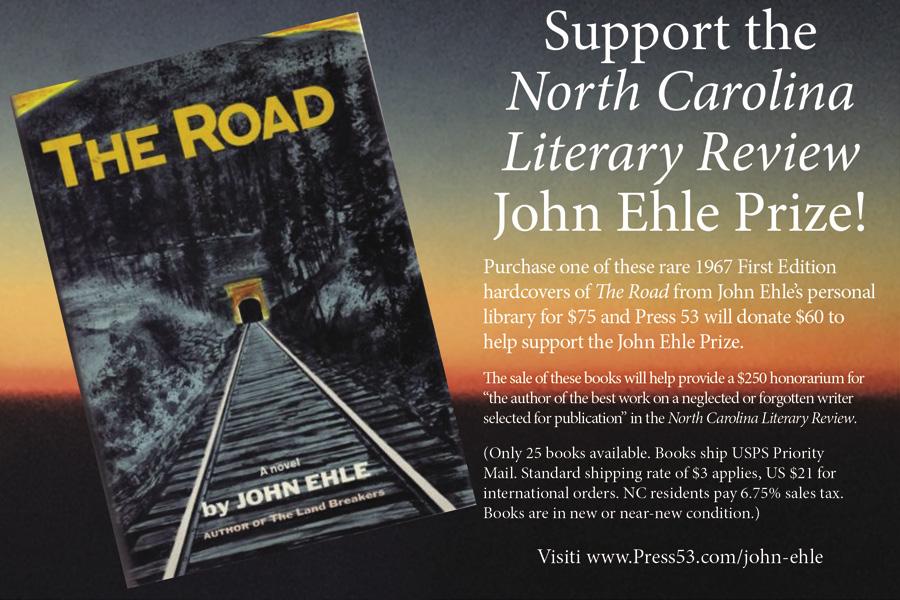

Advertisement

In this section, find reviews of books by writers we’ve published – Allan Gurganus’s selected stories collection and Ed Southern’s memoir – and on the subject of previous content – Popcorn Sutton. Enjoy poems by writers who have been James Applewhite Poetry Prize finalists before: J.S. Absher, Priscilla Melchior, and Benjamin Pryor. And here too we pay our respects to North Carolina's much lauded and beloved mystery writer, Margaret Maron, and her husband, Joe, who passed away within months of each other this past year. As D.G. Martin often advises new North Carolina residents, I learned much about the many treasures of North Carolina through Margaret's Deborah Knott series, while also enjoying the escapades of her central sleuth and admiring Judge Knott for refusing to accept limitations often put upon women of her region and time. I am so grateful to Margaret for the lovely essay she wrote for our 2018 issue.

Other reviews and the literary award stories in this section hearken back to the special feature topics of past issues: 2017's Literature and the Other Arts, 2015's Global North Carolina, 2005's Outer Banks literature, 2001's speculative fiction, and 2000's focus on genre.* As Dale Bailey contemplates the genre of the oddly paired books we sent him to consider for review, he reflects on where we find books in our favorite bookstores, which inspired us to promote several independent bookstores of North Carolina within the layout of his review.

And here I add my own promotion of independent bookstores, who contribute so significantly to the strong literary culture of our state. Congratulations to their owners and operators for holding on through the pandemic, and thanks to them all for providing so much of our entertainment while we were secluding ourselves for safety. Many bookstores drastically reduced and even waived postage charges for mailorder book buying. Bookstores were also among the first to host Zoom readings, allowing writers to celebrate and talk about their new books. I am sure the reviews in this section – in the whole issue – will inspire book purchases, and I urge you: please buy those books from independent bookstores. Consider the cost difference from what you might pay Amazon to be a donation to a very good cause. n

* Who out there is reading the issue introductions? Match the back issue themes listed here with a review or award story, and receive free copies of all of these issues mentioned. Already have one or more them? We can offer substitutions from back issues to help complete your set of NCLR. Email your response to NCLRStaff@ecu.edu before the print issue release in June.

FLASHBACKS:

Echoes of Past Issues

104 That ye be not judged:

A Remembrance of Margaret and Joe Maron by D.G. Martin 106 Gluttons for Local Color a review by Zackary Vernon n Allan Gurganus, The Uncollected Stories of Allan Gurganus 108 Memory’s Songbook a review by Anna McFadyen n Jill Caugherty, Waltz in Swing Time 110 Two New City-Set Novels a review by James W. Clark, Jr. n L.C. Fiore, Coyote Loop n Terry Roberts, My Mistress’ Eyes Are Raven Black 114 Telling Her Story a review by Sharon E. Colley n Heather Frese, The Baddest Girl on the Planet

116 Lost in the Maze of Genre a review by Dale Bailey n Michael Amos Cody, A Twilight Reel n Tim Garvin, A Dredging in Swann 122 Flower of Zeus a poem by J.S. Absher

art by Meredith Hebden

124 Confederate Memorial Day a poem by Priscilla Melchior

art by Stephen L. Hayes, Jr.

126 The Ladder a poem by Benjamin Pryor

art by Chris Foley

127 The Vitruvian Outlaw a review by Jessica Martell n Neal Hutcheson, The Moonshiner Popcorn Sutton 130 A Tale of Two Souths a review by Fred Hobson n Ed Southern, Fight Songs: A Story of

Love and Sports in a Complicated South 132 Natania Barron Wins 2021 Manly Wade

Wellman Award

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

6 n Teachers Who Write, Writers Who Teach

an interview, poetry, creative nonfiction, book reviews, and literary news 133 n North Carolina Miscellany

THAT YE BE NOT JUDGED: A REMEMBRANCE OF MARGARET AND JOE MARON

by D.G. Martin

Judge Knott, that ye be not judged.

No, it’s not just a typo in a Biblical quote; rather, it is meant to be an insider’s signal to the fans of the popular North Carolina author Margaret Maron.

Maron died on February 23, 2021, following a stroke, leaving behind a group of admiring fellow authors, bookstore owners, and loyal readers. She was best known for her twenty-book mystery series featuring Judge Deborah Knott and Knott’s extended family in rural North Carolina. It all began thirty years ago with Bootlegger’s Daughter. Set in fictional Colleton County, it was obviously inspired by Johnston County, just east of Raleigh where Maron grew up.

Maron’s work regularly dealt with art and artists, inspired by Joe Maron, her husband of sixty-one years, himself a talented artist and teacher. After a few years living in Brooklyn, where Joe grew up, Margaret brought him home where they settled on part of her family’s former tobacco farm. Joe died on June 20, 2021, just three months after his wife’s death.

People sometimes ask me what is the best book to learn about North Carolina. If the questioners like murder mysteries, I tell them to try one of the books in Maron’s Judge Knott series. Knott is a smart country woman lawyer who became a state district court judge in a typical North Carolina rural community. Deborah Knott is smart and good, but not perfect. She lives amongst a large farm family led by her father, Kezzie Knott, the former bootlegger, and his twelve children from two marriages, plus spouses and numerous grandchildren.

Having a former bootlegger as Judge Knott’s daddy and a few other mischievous kinfolks whose lives sometimes intersect with the law adds spice to Maron’s stories. Knott’s many friends and work colleagues also enrich Maron’s books. Everybody in Colleton County seems to know everybody else. Rich and poor; black, white, and Hispanic; farmers and townspeople; old and young; good and bad. We meet them dealing with problems of the environment, migrant worker issues, hurricane damage, political shenanigans, real estate development, and other challenges in addition to the murder mysteries that move every book along.

Maron used Judge Knott not only to solve crimes but also to make her readers aware of social issues and other local government challenges, always giving the viewpoints of society’s underdogs. At the same time she shared the rich, and not always pretty, family life in a North Carolina small town.

Every now and then, Maron moved the action to other North Carolina scenes: the furniture market, the Seagrove pottery community, the mountains, and the coast. Along the way, Maron’s readers get a good look at our state and its people.

Longtime host of North Carolina Bookwatch (1999–2021) is just one of D.G. MARTIN's many careers.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DONALD BARLEY

Maron brought back many of the same characters in book after book. She made them so real and compelling that some fans say they read the books just to keep up with the characters in Deborah’s family. Most important was a deputy sheriff named Dwight Bryant. First, he was just one of many characters. He worked his way up to boyfriend, then fiancée, and then husband. Maron stretched out that courtship over several books, reminding this reader of the courtship of Father Tim and Cynthia in the Mitford series of books written by another popular North Carolina author, Jan Karon.

Former state poet laureate Shelby Stephenson, Margaret’s cousin and neighbor, responded in poetry to my request for his thoughts about Margaret and Joe:

A lovely human being, Always giving, mentoring, While coming out with all those books Over 30. And l knew she had a huge following in England. But mostly she would go back to times In school at Cleveland, And Growing Up on a small farm As l did She would say Shelby, we are third cousins once removed. I have no idea what that means. As Margaret never ever let go of those things, Her roots.

About Joe, Shelby wrote, again in verselike lines

He bought and served lobster For our dinners together. He was always Margaret’s mentor. Margaret said so. His paintings and artistic flourishes settle like companions on the walls of their home.

Like Shelby, we will remember Margaret and Joe Maron, and promise that we will

not forget to “Judge Knott.” n

ABOVE Margaret and Joe Maron at the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Weymouth, NC, 16 Oct. 2016 (Read about her induction in NCLR Online 2017.)

GLUTTONS FOR LOCAL COLOR

a review by Zackary Vernon

Allan Gurganus. The Uncollected Stories of Allan Gurganus. Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2021.

ZACKARY VERNON is an Associate Professor of English at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC. He has published numerous articles in magazines and journals, such as The Bitter Southerner, Southern Cultures, Carolina Quarterly, and NCLR. He is also the editor of two recent essay collections: Summoning the Dead: Essays on Ron Rash (University of South Carolina Press, 2018; reviewed in NCLR Online 2019) and Ecocriticism and the Future of Southern Studies (Louisiana State University Press, 2019). He is currently working on a novel.

ALLAN GURGANUS has been featured regularly in NCLR – an essay by him in 2007, essays about him in 2008, 2014 (by Zackary Vernon), 2018 (online and print issues), an interview with him in 2018 (also by Vernon), and most of his books reviewed over the years. His numerous honors include the North Carolina Award for Literature, and induction into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame. Allan Gurganus’s stories have a splendidly antique feel about them. That’s not to say they’re out of fashion. Rather, Gurganus refuses to bend or pander to trends in contemporary fiction. His style is both his own and one that possesses the gravity of nineteenth-century literature; the stories are ornate, the prose at times flowing and florid. Henry James comes to mind, as does Chekhov, whom he mentions specifically in the opening story of the collection. This is, as one of his characters says, “King James” storytelling (171). Gurganus’s luminous tales are told in voices that don’t feel of our time, and they are stranger and more beautiful for it.

Gurganus’s preoccupation with past worlds and styles is immediately apparent in this new collection of nine stories. Take, for example, the first one, “The Wish for a Good Young Country Doctor,” which was published in The New Yorker in 2020. The story begins with a frame narrative in which a graduate student from the University of Iowa’s American Studies program travels to small-town, Midwestern antique stores in search of “folk manifestations” and “outsider art” (17, 19). The importance of the material objects themselves quickly diminishes, and it becomes clear that what matters to the character is the human connections these objects evoke. He is, like Gurganus, a collector and curator of stories.

Beyond the playful metafictional elements of “The Wish for a Good Young Country Doctor,” there is a serious and pressing message for our current moment. One of the stories that the student discovers concerns a mid-nineteenth-century doctor who arrives in a small town during a deadly cholera epidemic. The doctor saves many lives with his scientifically informed advice and compassionate approach, believing as he does that “civilization depends on nobody going untended” (35). This, of course, resonates beyond the context of this nineteenth-century plague. Gurganus also offers commentary on more recent events – from the AIDS epidemic that he himself lived through to our current battle with COVID-19. In such crises, surely the most important thing we can accomplish is to ensure that everyone is well tended to.

Other stories have less clear ethical imperatives to offer. “The Mortician Confesses” is told from the perspective of a sheriff in Falls, NC (the fictionalized version of Gurganus’s own hometown of Rocky Mount) as he investigates a funeral home worker whom he catches having sex with the body of a dead woman. It’s an intensely uncomfortable story from start to finish, inviting us to try to understand not only a man who violates a corpse but also a sheriff who finds the whole ordeal titillating.

Taboos abound in Gurganus’s work, and he forces readers to face them and consider whether they should remain taboo. In some instances, his characters overcome racism and homophobia, but in others, as in “The Mortician Confesses,” the characters continue to dwell in a very dark place. At one point, the sheriff remarks, “When it comes right down to it, we think we know decency and what local folks will do for other locals, but we ain’t got clue

number one as to what-all lurks in any human heart, much less lower-down especially, now, do we? Ever?” (69).

Gurganus is a writer who thrusts the unexpected and unexplainable onto ordinary characters. But he’s kinder to, and more accepting of, the people who populate his works than, say, Flannery O’Connor. The way to grace for him is less narrow, less about salvation in a religious sense and more about learning to empathize. And empathy can be a tricky or even dangerous business if we confront characters like those in “The Mortician Confesses.” Gurganus leaves us to squirm in some of these stories, as we struggle to comprehend both the good and evil that gain purchase in his characters’ hearts.

Some characters arrest my attention more than others. The protagonist in “He’s at the Office” is less engaging than most. This man cannot cope with retirement from an office supply company, so his family tricks him into thinking he is still employed by setting up a fake office, where they enable him to pretend to work until his death. Although I struggle to connect with this man, even here Gurganus manages to get me to think deeply about his tragic life. The character is so vividly presented that I feel like I know him, and in knowing him could extend a kindness to him or to people like him.

All the stories in this collection maintain Gurganus’s customary focus on the lives of local people, most often those from Falls. In “Unassisted Human Flight,” a reporter investigates a middle-aged man who, at the age of eight, was picked up by a tornado and allegedly flew through the air for a quarter of a mile. Everyone in the town is obsessed with the case because they’re “gluttons for local color” (92). The reporter “worship[s] unvarnished ‘Nonfiction’” and is “downright antinovelistic,” saying, “Who needs make-believe – given a world constructed so weirdly as ours?” (96). In a later story, another character makes a similar point, noting that “In a town this small, fiction’s unnecessary” (176; emphasis in original).

After he confirms the veracity of the child’s “unassisted flight,” the reporter states, “We grant ourselves so little daily hope. Meanwhile, barely noticing, we’ve already managed wonders” (124). This theme continues in “A Fool for Christmas,” a story about a mall pet shop owner who helps a teenage girl delivery her baby after her religious parents reject her. The owner asserts, “Ain’t people wonderful!” (143), as he reminisces about the girl’s aplomb.

Although sometimes dark and distressing, Gurganus’s stories possess a sense of unadulterated curiosity. Human nature thrills and horrifies the characters in turns. Gurganus seems to be similarly enamored by human potential. To limit one’s potential for any reason – fundamentalism, sexism, racism, homophobia – is rendered tragic in his stories, for to do so prevents the individual from attaining happiness and fulfillment, and collectively we then miss out on whatever may have resulted from that person’s full experience and expression. To limit another’s potential, in other words, is tantamount to murder by increments.

At the end of a story about an aging woman who leads historical tours of Falls, she remarks that God must have taken “early retirement,” leaving us on earth with “no practical instructions” (192). Gurganus suggests that in the absence of a divine intermediary, we must look to one another for help. As one character reminds us, “It’s a privilege to at least try saving one another” (209). Perhaps we should more often look to stories like these for models of how to live and how to treat one another, attempting compassion always, imperfect but incessant. n

PHOTOGRAPH BY DALE EDWARDS

MEMORY’S SONGBOOK

a review by Anna McFadyen

Jill Caugherty. Waltz in Swing Time. Black Rose Writing, 2020.

Raleigh native ANNA MCFADYEN has reviewed for NCLR since 2018 and was a semifinalist in the 2020 James Applewhite Poetry Prize competition. Her latest articles appear in EcoTheo Review and, forthcoming in 2022, Journal of L. M. Montgomery Studies. She received her MA in English Literature from NC State University and her BA from Meredith College, where she served as a chief coeditor of The Colton Review and was awarded the Norma Rose and Marion Fiske Welch scholarships in English and Creative Writing.

JILL CAUGHERTY’s short stories have appeared in 805Lit, Oyster River Pages, and The Magazine of History and Fiction. Her debut story, “Real People,” was nominated for the 2019 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. The author is a graduate of Stanford University with an MS in Computer Science from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and an MBA with honors from UNC Chapel Hill. She worked for twenty-five years in the tech industry as an award-winning marketing manager and now pursues creative writing full-time in Raleigh, NC. Jill Caugherty was inspired to write her debut novel, Waltz in Swing Time, by the life and letters of her maternal grandparents. In this testimony to the power of music, ninety-yearold Irene Stallings remembers her career as a pianist, singer, and dancer during the Great Depression. Chapters alternate between Irene’s vibrant youth and her troubles in old age – a temporal dance that prevents readers from losing sight of her core identity, regardless of her external deterioration. Throughout this book, Caugherty explores one of the most overlooked but important forms of social invisibility today: the devaluation of the elderly. With frankness, she examines seniors’ loss of agency and visibility amid physical decline, as well as their plight of loneliness.

Irene rebels against these issues by secretly recording her memoir on a handheld device. Unfortunately, assisted-living personnel think she is “talking to [her]self,” a senile behavior to medicate (23). Their misunderstanding epitomizes assumptions that younger people make about Irene. Her reactions against agism remind me of “Gynecology,” a poem from Kay Bosgraaf’s The Fence Lesson (2019), which I previously reviewed for NCLR. The poem’s narrator refuses to discontinue her pap smear screenings in her seventies, protesting, “How dare [the doctor] tell me I am not / viable? I will have my exams.”* Irene similarly wants her life to matter – to be seen as more than old. She declares, “[R]esistance . . . is all I have left,” as she fights to remain herself. She does not wish to be drugged into docility, thinking, “Even if I’m sad, my emotions are real, not out of a bottle” (26–27). However, as Irene begins to make “wrong turns” in confusion, she admits, “I can’t help feeling that something essential is slipping away from me, ever so gradually, not unlike the eating away of a sandstone cliff in a canyon from years of harsh winds and water, until the cliff’s definition collapses, and its composite gravel and clay have washed down the mountain” (51). Her (appropriate) metaphor recalls the terrain of her youth in Utah.

Irene’s recordings narrate her escape from farm life into the exciting world of entertainment, set during the era of jazz clubs and Fred-and-Ginger musicals. Songs like “Someone to Watch Over Me” and big band hits play across the pages, evoking the glamor of the time. These elements shine between shadows cast by the Depression, and yet Caugherty paints the desperation of this period carefully.

When Irene’s Mormon parents sell their piano to survive, their daughter’s artistic soul starves, but her dreams persist. Irene’s musical talent becomes her ticket away from hardship and rural conventions. A summer entertainment job at Zion National Park provides the professional opportunity she craves, but Irene’s chances are jeopardized when she falls for a seasoned dancer at the camp. Her electric scenes with Spike bring Dirty Dancing to mind, as the young couple escapes the Depression through the thrill of performing together. Their

courtship unfolds among the natural wonders of the canyons, where CCC boys build trails for Roosevelt’s economic relief program. For a time, this young pair escapes the Depression in the thrill of performing together.

Lines from Irene and Spike’s favorite song foreshadow the protagonist’s twilight years: “Someday, when I’m awfully low . . . I will feel a glow just thinking of you, and the way you look tonight” (238). She will depend on memories of love to make her final trials endurable, finding company in the backward glow of her musical history. As Irene copes with discouragement, Caugherty emphasizes the power of music therapy for the elderly. Music is a lifeforce to Irene, imparting inner freedom and solace.

More than any other grievance of her changing lifestyle, Irene resents being treated like a child in old age. The swapping of mother-daughter power roles is difficult for her to accept, as her daughter becomes the parent figure. Irene feels angry when Deirdre and the doctors talk past her head during appointments, making decisions as if she were not present. She knows her daughter “means well,” but Irene has fought for independence her entire life, and she does not surrender the habit easily (27). Caugherty’s novel explores this and other frictions between mothers and daughters across four generations. Although Irene disagrees with Dierdre, she tries not to repeat her own mother’s mistakes that prevented healing between them.

When Irene first moves to an assisted-living community, her cynical humor brands the Golden Manor the “Golden Manacles,” despite its elegant dining room, movie nights, bridge parties, beauty parlor, budding geriatric romances, and bevies of stylish white-haired ladies (6). She admits, “The forced jollity of the Manor sometimes makes me want to scream. I never chose to spend my final days in a Disney Land for seniors” (76). To her amazement, other residents behave like they are not approaching the end, and they do not resist being coaxed into a second childhood. Irene scoffs that staff members “don’t dare publicly acknowledge the other possibility, that we are entering a horror . . . a steady downward spiral” (199). Instead, they throw parties with “cake . . . ice cream, birthday hats . . . balloons, even a few . . . favors for the guests,” especially for “residents whose families may have forgotten them completely. That is to say, whose relatives have abandoned them here, signed away checks, and, like the three monkeys, closed their eyes and ears to any bad news from inside these walls.” Irene observes that residents are eventually “pushed around the garden in wheelchairs that might as well be adult-strollers,” and she is aware of their “spoon feedings and diaper changings” (198–99). In her view, the Manor is an anteroom to death, with a nursing wing waiting conveniently around the corner.

The Manor’s carnival atmosphere cannot distract her fellow residents from every reality, however. When Irene’s friends visit her in her final stage of care, they “inch ever so slightly away, and gaze out the open door into the hallway,” uncomfortable in the knowledge that “once people arrive in the nursing wing, they don’t come out alive” (274). As they leave, Irene says, “I have the sensation that I’ve just seen someone very dear off at the train station,” but it is her own self that slips away: “I fill with the quiet, inescapable knowledge that the person who has left will not return” (275). She must make peace with her departure.

Caugherty knows assistedliving culture well, including its routines, ironies, and forged alliances. Her observations ring true in my own experience: for a decade, I spent hours every week visiting my grandmother in an elegant assisted-living community like Irene’s. And like this protagonist, my grandmother was always a young person trapped inside an old person’s body, with the fight to enjoy life still surging in her, even though doctors, blinded by her age, overlooked her potential to contribute further to society. At 101, she had not given up on achieving a fuller lifespan. Fortunately, she had advocates in my parents, who helped her pass the century mark, but too many elderly people do not have defenders against ageism, even in high-end facilities. This novel illustrates how a balance of care and listening must be achieved to preserve a person’s individuality – and it acknowledges that the longings of the elderly are no less important than those of the young.

These topics are seldom addressed at length in fiction with an insider’s perspective, and few novels open with a nonagenarian narrator. I applaud Caugherty for addressing the emotional and intellectual value of the elderly without dismissing or diminishing them in the process. She draws attention to a deserving subject. n

TWO NEW CITY-SET NOVELS

NCLR COURTESY OF

a review by James W. Clark, Jr.

L.C. Fiore. Coyote Loop. Adelaide Books, 2021

Terry Roberts. My Mistress’ Eyes Are Raven Black. Turner Publishing, 2021.

JAMES W. CLARK, JR.’s most recent honor is the 2020 John Tyler Caldwell Award from North Carolina Humanities. Read more about him in that award coverage in NCLR Online 2021 and in the coverage of his 2018 induction into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame in NCLR Online 2019. What would Lee Roberts think of My Mistress’ Eyes Are Raven Black, his son Terry Roberts’s latest novel? Set on Ellis Island, it is a hard-boiled detective thriller, the type of book Mr. Roberts was addicted to, short chapters and all. Having died many years ago, he will not be reading My Mistress’ Eyes Are Raven Black. Nor does Mr. Roberts know that his talented son’s three previous historical novels are bringing distinction to the family name and to Western North Carolina in particular.

Stephen Robbins narrates the Hot Springs, NC, book about internment, A Short Time to Stay Here (2012), and this new book also. In each, the subject is processing alien people: first the German nationals detained stateside during the Great War and now the masses of immigrants pouring into Ellis Island in 1920 where US immigration policies and practices had become a hateful mixture of xenophobia and religious bigotry. Administrators as well as staff in the thriller become suspects in vicious murders intended to preserve this country for white Christians and to spare the government the expense of caring for poor, tired newcomers and their offspring.

The narrator clearly details surges of hatred fueled by Christian hypocrisy and the fear of difference on Ellis Island. Simultaneously this troubled place fosters a sizzling love affair for him and a bold female detective. Both arrive to investigate the brewing cultural disaster.

Lucy Paul and her partner Stephen are themselves outside the American mainstream. She is a mulatto nurse working undercover for the American Medical Association to find out who is killing immigrants of color and other aliens deemed undesirable by Ellis Island insiders. Stephen, from the North Carolina mountains, had, until recently, been managing the restaurant in the Algonquin Hotel on West Forty-Fourth Street. A “mixedblood mongrel” (176) by his own account, he can close his “eyes and imagine things other people couldn’t see” (8). Gifted to know

ABOVE Terry Roberts talking about the work of his friend and mentor John Ehle at the 2021 John Ehle Prize Celebration, a virtual event organized by NCLR and Press 53 of WinstonSalem, 24 Mar. 2021 TERRY ROBERTS’s first two novels – A Short Time to Stay Here (Ingalls Publishing Group, Inc., 2012; the subject of an interview with Roberts in NCLR 2014), and That Bright Land (Turner Publishing Company, 2016; reviewed in NCLR Online 2017) – received the Sir Walter Raleigh Award for Fiction, given by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association and the Historical Book Club of North Carolina. His other honors include the 2017 James Still Award for Writing in the Appalachian South, the 2016 Thomas Wolfe Memorial Literary Award, and the 2012 Willie Morris Award for Southern Fiction. Roberts grew up near Weaverville, NC. His family has lived in Madison County, NC, since the Revolutionary War. He is the director of the National Paideia Center in Asheville, NC.

“something before knowing was strictly possible” (185), Stephen is employed by the US Department of Justice to find, in particular, a missing pregnant Irish lass named Ciara McManaway. The federal agent from whom Stephen accepts his new assignment is blunt: “I think the fish ate her weeks ago” (6). He and Lucy suspect that some of the pious staff probably cooked Ciara in the laundry autoclave before she was served up to the fish.

They also share a narrow cot in the psychopathic ward “up under the roof of Building E on Island 3” (20). Lucy in her late thirties and Stephen in his forties, both are single, childless adults who despite having been damaged in earlier romantic liaisons seem to be willing to go through the fires of vulnerability again. After a forced abortion in England, Lucy had been told by her lover, the abortionist, that she would be unable to conceive another child. Formerly married, Stephen has very recently moved away from 1000 Fifth Avenue where since 1918 he had been living with his lover, the photographer Anna Ullman, whom he met in the earlier novel.

If Lee Roberts would expect his son’s layered thriller to lead to any very clear answers, he would be shocked to see what Terry Roberts has done with both crime and romance in the hard-boiled form.

No one ever knows for certain what became of poor Ciara. The vicious and fanatical suspects in the disappearance of her and several other immigrants, plus one staff nurse, are not brought to court. The higher administration of Ellis Island remains largely in place. In the last three chapters, Stephen, badly injured, is having visions, talking to himself and an absent dog named King James on a train heading homeward to Western North Carolina.

As My Mistress’ Eyes are Raven Black seeks its end in readers’ imaginations, the thrust and momentum of the narrative are very personal for Stephen and Lucy. Poor Ciara is gone and forgotten. It is clear that Nurse Lucy is the “mistress” of the title. What do readers imagine the fate of the child they are expecting will be in Anderson Cove? Given the horrible torment some immigrants faced at Ellis Island due to their physical and racial differences, how will this child fare in the upland South? The narrative gifts attributed to the recovering father must now be employed by his readers.

Visiting a library with Daddy is one of the earliest memories of L.C. Fiore, author of Coyote Loop, set in Chicago. The “About the Author” note at the end of the novel reports, “Even today, the world never quite opens out for him the way it does when

he renews his library card – the surging sensation that suddenly, through books, anything is possible” (333).

Fiore’s raw 2008 Christmas season tour in and around the Chicago Board Options Exchange in the Loop is guided by John Andrew Ganzi, or JAG, a “millionaire at twenty-six” (14) with a nasty gift of gab. He is a short, fat, greedy, parent of a high school basketball star named Jeanie or Jeans. Following her parents’ divorce when she was ten, Jeanie had lived with her mother until the late winter of 2008 as the economy in which her daddy is a hero is tanking. Just seventeen, she has moved in with him because her mother, a college professor of religion, was denied tenure at the University of Chicago and has moved to Florida. In the holiday chaos, will young Jeanie be able to meet Georgetown University women’s basketball coach New Year’s Day morning 2009?

In addition to madly loving his rambunctious daughter and trying in a broad spectrum of unseemly ways to be her sufficient, single parent, JAG has long experience as the father figure to the mostly male, aggressive traders who work with him in the pit where until now he spent most of his time. Indeed, before Jeanie came to live with him in his eighteenth-floor apartment, the trading pit was the center of JAG’s beastly world.

The clerk of the pit scene is Pasternak, a large Polish man. Eager himself to become a

COURTESY OF THE NC WRITERS’ NETWORK

trader, while JAG prefers him as his experienced clerk, this financially underwater, lifelong friend from the old neighborhood drowns himself in the Chicago River after the office Christmas party, a boozing fest held at the Art Institute. When Jeanie and JAG attend Pasternak’s wake, options traders from the pit learn for the first time that JAG even has a daughter.

Lucas, now a Chicago policeman, is a former pit trader who left that job because he could not take the stress: “his soul was too pure for finance” (159). In his public safety position he intervenes several times during Jeanie’s Christmas season with her father. This impressive black officer uses his position and his knowledge of JAG to keep as much adult and juvenile misbehavior as possible from destroying his former boss’s parenting experiment in its first weeks. It is Lucas, for instance, who kindly comes to the pit to inform JAG about Pasternak. For reasons of his own, JAG soon makes up an elaborate false account of the suicide of his friend Pasternak.

JAG and Jeanie do have less fraught moments. While making pancakes for dinner, they explore the “practical application of mathematics to real-world issues” (109). Laptop open, Jeanie asks her father to “guess how many cattle are lost to coyotes every year?” (109). He flips pancakes while crunching numbers in his calculator brain. The answer he comes up with is 0.20 percent of all US cows. She checks the laptop and confirms that he is close; the online answer is 0.23 percent. “No big deal” (110). But then he goes into a brief lecture about percentages during which the smoke alarm goes off. When the smoke clears with part of their dinner burned to a crisp, JAG switches from numbers to just plain words. If

ABOVE L.C. (Charles) Fiore at the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Southern Pines, NC, 2018 L.C. FIORE hosts the A440 Podcast and is the Communications Director for the North Carolina Writers’ Network. His work has been published in such venues as The Good Men Project, Ploughshares, Michigan Quarterly Review, New South, storySouth, and The Love of Baseball: Essays of Lifelong Fans (McFarland & Company, 2017). His novel The Last Great American Magic (Can of Corn Media, 2016) won Underground Book Reviews’ Novel of the Year award, and Green Gospel (Livingston Press, 2011) was First Runner-Up in the Eric Hoffer Book Awards in General Fiction.

the number of cows killed by coyotes each year is roughly equal to the population of Ann Arbor, he adds, “you can work up some indignation that way” (110).

In subsequent references to coyotes, Board Options Exchange Chairman Sar reports that coyotes are killing cattle and other animals in South Dakota, JAG wonders if Jeanie can see coyotes from the “L” at night, and she asks him if he knew that coyotes mate for life. This motif earns the novel its title when JAG addresses the whole options trading force in the cafeteria of the Exchange in the Loop. His rambling speech, of course, is extemporaneous, like his entire life, but his serious topic is “Adapt or die” (284), code words for their becoming “a publicly traded company or risk losing this beautiful industry entirely” (283). He says in his characteristic idiom: “I tell you who I see when I look in the mirror. A fucking coyote. That’s right. And here’s why: coyotes adapt to their environment. City, country, woods – they don’t give a fuck” (287). The traders, despite the financial losses coming their way, vote overwhelmingly to do as JAG has advised. He thinks to himself as the session concludes: “sometimes, it’s in your best interest to let yourself be fucked” (288). Happy holidays.

Remaining to be considered in Coyote Loop is the New Year’s Eve party JAG allows Jeanie and her underage friends to celebrate in the apartment he shares with her. She ends up naked with alcohol poisoning and is rushed to a local hospital’s emergency room. Lucas shows up there, as before, to help this most irresponsible parent and his child, whose alcohol level was 0.32. Her doctor says she will recover. Later that early morning, the cop hands JAG an order for him and his daughter to undergo rehabilitation. This order is on top of the alcohol counseling JAG has been receiving since his recent DUI.

Finally allowed outside the hospital to smoke, JAG is improvising the next act of his tragic parenthood. A getaway for him and Jeanie. Lucas is speaking, but JAG is oblivious. Then daddy-o bolts away in pursuit of a lone coyote and follows it into and up to the top of a parking deck. All alone there this rich, desperate fortyfour-year-old Chicago addict greets the dawn of January 1, 2009, “like a new born-scavenger” (330).

How he gets safely down from there, where helpful Lucas has gone, when and how JAG gets Jeanie out of the hospital and to their trashed apartment: all these parenting roles are left up to chance and the readers’ imaginations. The coyote JAG was following is unaccounted for, too.

These two novels set respectively in New York City and Chicago show the creative energy of North Carolinians Terry Roberts and L.C. Fiore. In late 1920 an unborn and unexpected child is on its way to life in Western North Carolina. Seventeen-year-old Jeanie Ganzi of Chicago could as easily be on her way to an early grave as to basketball stardom in 2009 at Georgetown University. n

Call for Submissions

for the JOHN EHLE PRIZE: $250

SUBMIT BY August 31 annually

For more information, writers’ guidelines, and submission instructions, go to: Given annually for the best essay on or interview with a neglected or overlooked writer accepted for publication in NCLR

NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW

Sponsored by

TELLING HER STORY

a review by Sharon E. Colley

Heather Frese. The Baddest Girl on the Planet. Blair Publishing, 2021.

SHARON E. COLLEY is Professor of English at Middle Georgia State University. Her most recent article, “Kaleidoscopic Swirls of Lee Smith,” was featured in NCLR 2021.

HEATHER FRESE, a resident of Raleigh, NC, has published fiction, essays, and poetry in Michigan Quarterly Review, the Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere, earning notable mention in the Pushcart Prize Anthology and Best American Essays. She earned her MFA from West Virginia University. Heather Frese’s debut novel, The Baddest Girl on the Planet, is the 2021 winner of the Lee Smith Novel Prize. The novel tells the story of spirited Hatteras Island, NC, native Evie Austin and her struggles as a young mother and divorcee trying to make sense of her life. A strong-willed young woman telling her own story is familiar to readers of late twentieth- and early twenty-first century Southern women writers, such as Kaye Gibbons, Connie Mae Fowler, Jill McCorkle, and, of course, Lee Smith, whom the award honors. Smith’s female characters need courage to thrive in their challenging and at times impoverished environments. Frese’s book updates and offers an original contribution to this popular vein in Southern women’s fiction.

While most of the thirteen chapters (note unluckiness reference) use first person, three chapters, including the final, are in second person. With many young writers, this choice can come off as experimenting for its own sake, but Frese’s effective usage helps readers empathize with the protagonist. Furthermore, the orally-inflected novel skillfully alludes to multiple text forms. In Chapter Five, Evie tries to cope with the death of her aunt, “the one constant presence in my life” (67). She playfully organizes the narrative around rules from her imaginary Big Book of Funeral Etiquette: “Even if the deceased did indeed enjoy both fishing and the company of fishermen, waders are never appropriate funeral attire” (70). Chapter Seven, “Postpartum, 2009,” is punctuated by letters to Dear Abby, while Chapter Ten, “An Open Letter to Patricia Balance, 2008,” is written as a class assignment during Evie’s only semester in college. The oral quality of the narrative slips seamlessly into these minitextual forms, creating a varied and lively book.

The novel’s title, The Baddest Girl on the Planet, is an ironic reference to former heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson, at times called the Baddest Man on the Planet. Evie begins the book by stating, “My husband is not the first man to disappoint me. That honor goes to Mike Tyson” (1). This combination of the spoken voice, sarcastic whimsy, and complicated feelings about men thread through much of Evie’s narrative.

The popular culture image of Mike Tyson is a touchstone for Evie. As a child, she met Tyson in passing during a vacation and proudly exaggerated their friendship at school, until he was accused of rape. Then her social stock plummeted. Frese adeptly returns adult Evie to the symbol of Tyson at several significant moments, to surprisingly gratifying effect.

Evie is entertaining from the start, but not appealing initially. While she does not deserve the novel’s title, in the first chapter she seems mean-spirited and weary as she rationalizes an affair near the end of her short marriage. Much of this energy

reflects the way she sees herself and her circumstances at this difficult moment.

By the end of the novel, we discover that Evie has believed too much local gossip about herself. After acquiring a not completely deserved reputation in high school, followed by an unplanned pregnancy and a tumultuous early marriage, Evie embraced a negative view of herself. Eventually, the reader and Evie learn that she is kind-hearted, somewhat responsible, and not nearly as wild as advertised. The novel’s development allows the reader to see Evie’s growth in self-esteem and self-respect. In the penultimate chapter, Evie wanders around Las Vegas, hoping to find and “to get revenge on [Tyson] for ruining my life” (204). Tyson represents for Evie the men and things she has trusted only to feel betrayed. The rather tipsy but humorous pilgrimage enables Evie to finish processing negatives in her past and possibly move towards embracing a positive future.

Evie’s relationships with men, however, do not provide the only thematic material. Her friendship with Charlotte, who vacationed on Hatteras Island as a child, surfaces at important moments in Evie’s life. Charlotte’s family is wealthier than Evie’s, and their lives significantly diverge when a pregnant Evie leaves college to marry while Charlotte continues through graduate school. Their

perspectives clash in Chapter Four, “Dominican Al’s Once-ina-Lifetime Honeymoon Extravaganza, Sponsored by Dominican Al’s Rum and Fine Spirits, 2014.” Post-divorce, Evie has entered and won a free honeymoon in the Caribbean; she takes Charlotte as her “partner.” When Charlotte bemoans the resort’s exploitation of poverty-stricken islanders, Evie explodes: “You mean the way you colonized my island every summer? How come that never made you uncomfortable? How come you think you have the right to exploit the locals there but not here?” (58).

Evie is smart and perceptive; though Charlotte often provides her a rational, calming PHOTOGRAPH BY SANDY CARAWAN, SANDY SHORES PHOTOGRAPHY influence, Evie pushes Charlotte out of her comfort zones, intellectually and emotionally. The friendship is as significant as and longer lasting than Evie's romantic relationships. Similarly, motherhood is a central theme in the book. As she narrates her experiences with her newborn, Evie is unsentimental and honest about her physical and emotional exhaustion. Her unromanticized description of life with a sometimes confusing, sometimes exasperating, but dearly loved child is convincing and moving. Her difficulties trying to sort out what is best for each of them, and how much motherhood requires of her, serve as an ongoing conflict in the book.

The Baddest Girl on the Planet is an engaging, clear-eyed, and emotionally nuanced story of a young woman’s twenties. The text’s oral narrative voice, its use of humor and unexpected mixtures that work, as well as its exploration of perennial themes of relationships, friendship, and motherhood, provide a fresh voice engaging with familiar Southern themes. n

LOST IN THE MAZE OF GENRE

a review by Dale Bailey

Michael Amos Cody. A Twilight Reel: Stories. Pisgah Press, 2021.

Tim Garvin. A Dredging in Swann. Blackstone Publishing, 2020.

DALE BAILEY’s new short story collection, This Island Earth: 8 Features from the Drive-In, is forthcoming from PS Publishing. He is the author of eight previous books, most recently In the Night Wood (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018; reviewed in NCLR Online 2019), The End of the End of Everything: Stories (Resurrection House Press, Arche Books, 2015), and The Subterranean Season (Resurrection House Press, Underland Press, 2015). His story “Death and Suffrage” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, 2002) was adapted for Showtime’s Masters of Horror television series. He has won the Shirley Jackson Award and the International Horror Guild Award, and has been a finalist for the World Fantasy, Nebula, Locus, and Bram Stoker awards. He lives in North Carolina with his family. In many ways, the question of genre shapes how we understand literary production in the twenty-first century. How do we pigeonhole the books we read? How do those pigeonholes influence the way we read and value them? These questions come into clear focus in the juxtaposition of Tim Garvin’s A Dredging in Swann, the first volume in a projected series of mysteries and police procedurals set in the fictional county of Swann, NC, and Michael Amos Cody’s collection of short fiction, The Twilight Reel, set in the Appalachian Mountains. Neither book is entirely successful (what book is?), but both possess significant merits. Taken together, they reveal some key insights into what we mean by genre as we begin the third decade of a new millennium.

Academic critics have conventionally seen genre in broad terms – poetry, fiction, drama – that can be broken down into more narrowly defined subgenres: the lyric poem is a different animal than the epic one, the realistic and naturalistic fiction of the late nineteenth century contrasts with the postmodern fiction written a hundred years down the line.

Marketing directors at publishing companies and bookstore buyers take a different tack. They shove books into commercial categories meant to goose sales. Got a hankering for spaceships and robots? Check out the sci-fi shelves on Aisle 11. Feeling randy? You’ll find the bodice-bursting heavypanters over in Aisle 14. Looking for something gruesome? Stephen King’s your man. You wanna know whodunnit? You’ll find Philip Marlowe over in Mystery, keeping company with Miss Marple. Genres, in short, are a marketing tool.

As for the quality stuff, you’ll find it over this way, walled safely off from the commercial ghetto. You can call it general fiction or mainstream fiction if you’re feeling generous, “literature” if you’re inclined to turn up your nose at lowly hackwork about elves and dwarves or pirates with a penchant for their lusty maiden captives. Lennon and McCartney may have extolled the life of the paperback writer, but it’s a losing game.

It goes without saying that as an academic and as a category writer myself, I have a dog in this fight. I don’t see a lot of difference between the “good” stuff and the “rubbish” the common folk read. And I think the juxtaposition of Garvin’s police procedural and Cody’s literary short stories drives my point home.

In A Dredging in Swann, Tim Garvin checks off the boxes of the police procedural with the requisite skill. Take Seb Creek, his hard-boiled protagonist, an off-the-shelf police detective who works the shady, gray areas at the edge of the law (he has a penchant for violence) and keeps pushing at the murder case that drives the book, kicking awake sleeping dogs his

fellow cops are more inclined to let doze. He’s damaged goods (stints as a marine in Iraq have left him scarred with PTSD), but he insists on looking for true north in a world without a clear moral compass. He has a quirky side gig (he’s started a singing group called Pass the Salt to help heal other PTSD-damaged veterans) and a near-death experience. He has a budding romance with an artsy type (a local pottery instructor) whom he’d like to protect from the horrors of the world around him and the horrors that bloom in his own damaged heart.

And of course he’s as deeply rooted in place as the great detectives that precede him. Philip Marlowe owns Los Angeles (except for Watts, which is Easy Rawlins’s turf). Spenser is to Boston as Dave Robicheaux is to the bayous of Louisiana. Tess Monaghan polices the mean streets of Baltimore, Nick Stefanos those of Washington, DC (at least when he’s sober). And when he’s not falling off the wagon himself, Matthew Scudder sees to the seedier parts of New York City. Seb Creek is a creature of the fictional Swann County, NC, but his world seems to be roughly contiguous to Camp Lejeune and its surroundings (one subplot involves the theft of a handful of Stinger missiles, another the poaching of Federally protected Venus Flytraps) and the puzzle he’s set to untangle is deeply rooted in the military culture of the nearby Marine base, the local hog-farming industry (you’ll never look at bacon the same way again), and the state’s long history of racism. Tangled family histories come into play. Axes are wielded to horrific effect. Extortion, illegal gambling, and prostitution make cameos. There’s even a gas chamber.

It’s a task to keep track of all this, but by the novel’s end Garvin winds it up skillfully. One only wishes he had been more careful with his language. At its best, the book’s prose is workmanlike; however, it too often veers off-track, wandering down little-trodden paths of the English language that are little trodden for good reason. When Garvin describes a lawyer making “a mouth smile” (147), one can’t help wondering what other smiling options are available – nose smiles? ear smiles? what? More problematic is Seb’s penchant for portentous, quasipoetic musings. Wondering how he will respond when Mia, his potter paramour, asks him what he does for a living, Seb imagines saying, “I am the sandman. I put the past to sleep” (47). One senses that Garvin thinks it’s a great line (he isn’t averse to repeating it, anyway), but it’s hard to imagine how Mia might respond to this pronouncement without a snicker. The line might – might – work in the context of a more lyrical prose style (but then again, it might not). In the context of Garvin’s windowpane thriller prose, however, it’s as out of place as a peacock crashing a party of house wrens. And the book hosts a chapter title that might have been plucked from a Dead Kennedys playlist: “A Really Pussy Heart Song” (102). These

are only blemishes, however, on a solid, if unsurprising crime novel – a book that is enjoyable enough to read and that bodes well for enjoyable-enough Seb Creek mysteries to come.

For those novels to achieve their real potential, however, Garvin must do more than employ the conventional tropes of his genre; he must innovate within them. The pleasure of reading a fine novel in any commercial genre is not dissimilar to the pleasure one derives from reading a good sonnet: we enjoy the constraints of the form only to the extent the writer does something unique within those constraints. Frost tells us that writing free verse is like playing tennis without a net. We watch the match not for the net, however, but for the artistry of the great player who can send a forehand rocketing over it to land an eighth of an inch inside the baseline. The same rule applies in commercial fiction of any genre. Readerly pleasures lie not in the constraints themselves, but in the writer’s skill at deploying them in fresh and illuminating ways.

The same thing is true of “literary” fiction, as Michael Amos Cody’s collection of short fiction, A Twilight Reel, makes clear. In “Overwinter,” the book’s third story, a cuckolded professor passes the long midnight hours of a blizzard with Joyce’s Dubliners – as one does, especially if one is a character in a collection of stories meant to trace the threads of meanness and grace woven through the deeply interconnected lives of a single town’s inhabitants. In short, the allusion is a bit too on the nose (it’s like being blindsided with a bottle of Bud Light in a bar fight, actually); Cody might have been better to dispense with it altogether. Failing that, he might have used Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, a specifically American story cycle that sets the bar somewhat lower. If, in the end, Cody doesn’t clear either hurdle, it hardly matters.

Who could?

He does give it a game shot, and in doing so he produces an

occasionally acute portrait of small-town Appalachia. But the allusion is a pointed reminder that “literary” stories are every bit as genre bound as their commercial cousins. With his small epiphanies, Joyce laid down the court lines of the genre wherein thousands of MFA aspirants have set stories with small epiphanies of their own. Many such stories are quite good, of course; they’re the artful equivalent of low backhand smashes over the net. The less successful ones barely clear the net at all. In A Twilight Reel, Cody has a fair amount of both.

His Dublin, his Winesburg, OH, is Runion, NC. Runion is (or was) a real place, a mill town near Hot Springs that began to fail a century ago, when the land was timbered out. The body blows of the Great Depression and World War II finished the job. Cody, however, imagines a present-day Runion and peoples it with an ensemble cast of small-town types. The preacher who encounters a hitch-hiking eccentric who may or may not be a demon (“The Wine of Astonishment”), for instance, turns up as a bit player in “The Loves of Misty Sprinkle,” the (unfortunately) eponymous hairdresser who endures his theme-appropriate sermon while pondering her romantic entanglements. So it goes.

The weakest stories here have a paint-by-numbers quality: they deliver your standard small epiphanies about the way you’d expect them to. “Conversion” presents us with a gang of small-town Pentecostals confronting the transformation of their divided church into a mosque. This goes about as well as one would expect. Despite the friendliness of their new Muslim neighbors, the Pentecostals condemn them as “devils” up to “God-knows-what unholy business” (145) before racing off in their Dodge Rams and Chevy Silverados, flinging up rooster tails of invective as they go. The ones who stick around have trouble distinguishing between Native Americans and immigrants from the Indian sub-continent. They are prone to saying things like, “If ya’ll are gonna talk in front of me . . . you talk American” (147). Only matriarchal Big Granny looks on with mountain-granny wisdom as the “mosque’s crescent moon rose above the dark mountain ridges” with “a pulsing white star in [its] silhouette-black embrace.” The sight stirs her into voice. “Well, ain’t that something,” she says in the story’s final lines. “Reckon what it might mean, Livvy?” (156). But we really don’t have to reckon very hard at all, do we? The story’s intent is laudable, to be sure, but it fails to

push past self-congratulatory sentiment into the ambiguities and complexities of real-world human conflict. In challenging one set of stereotypes, it merely reinforces another one.

Other stories are drawn in similarly broad strokes. In “The Invisible World Around Them,” an insurance salesman struggles to accept his gay son, Mike, who is dying of AIDS. In “A Poster of Marilyn Monroe,” a lonely widower surrenders the solitary pleasures of fantasy for the possibility of love. Poor Mike turns up again in “A Fiddle and a Twilight Reel,” to face down smalltown bigotry against people with the “queer sickness” (250).

There’s nothing inherently wrong with such stories, of course. People do come to terms with their gay children. Widowers do fall in love. Small-town bigotry often does prevail. But Cody tends to lay his thumb heavy on the scale. Ben Frisby and his sons, the rednecks who burn a straw effigy of much-abused Mike in “A Fiddle and a Twilight Reel,” are comically broad hillbilly villains. If Cody depicted them with more nuance, the story would gain weight and power. The genius of Southern writers such as Faulkner and O’Connor lies in their capacity to depict even their most despicable characters with a complexity that inspires our compassion. Abner Snopes in Faulkner’s “Barn Burning” is a violent monster, but underneath his fury one feels the frustration and despair of a man lashing out against a crushing social hierarchy. In O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” the murderous Misfit’s spiritual agonies are palpable.

Cody’s stronger stories push hard against the boundaries of the “small epiphany” genre story and move powerfully in the direction of such complexities. These tend to be longer stories, and their structural complexity reflects their more nuanced explorations of what we used to call the human condition. The two best pieces here are “Decoration Day” and “The Flutist.” Both stories are built upon simple premises, but they employ shifting points of view to rove through time and space, setting up mirror mazes of revelatory reflections between worlds past and present and worlds waiting to be born. In “The Flutist,” the strongest of the two stories, Jubal Kinkaid, one of the flutists the title alludes to, travels to Runion State University to interview for the position vacated by the untimely death of beloved faculty member Brian Anderson, the second flutist in question.

Cody gives us a deft and amusing overview of the faculty job search process. But the story transcends its academic focus to become something larger and more significant. Jubal’s potential job offer unsettles his partner back home in Chicago, who isn’t at all sure he wants to move to a southern Appalachian town that might not welcome gay men (he’s right on that score, as poor Mikey can

ABOVE City Lights Bookstore in Sylva, NC

attest). This troubled relationship finds its echo in Anderson’s love affair with a European flutist named Anna, who chooses a few months with her lover in Amsterdam every year over marriage in America. Anderson’s longing for Anna outlasts her death; it’s reflected in his paternal affection for a talented young student who much resembles her – an affection that spills over into a tentative kiss hours before his unexpected death. These events are presented in the context of an academic department where personal friendships, marriages, and professional jealousies are held in careful equipoise. Cody, to his credit, resolves none of these complications. No one has an epiphany summing up the point at hand with a bit of tidy mountain lyricism. As the story draws to a close, we’re not even sure Jubal will get the job. But by the time his plane lifts off from Asheville and turns toward home, the story has unfolded for the reader a sense of the manifold complexities of love as it ranges over gulfs of time, geography, gender, and age. In the final paragraphs, the story, like Jubal’s plane, takes flight.

It’s a memorable piece in part because it resists the constraints of the “small epiphany” genre that so often dominates “literary” short fiction. It’s hard to argue with Frost that watching a writer wrestle with the constraints of form, whether it’s a sonnet or a space opera, can provide one of the genuine pleasures to be had from the creative enterprise. But it’s also clear that it’s not the only, or even the most important, pleasure. The lines drawn between and within genres – even “literary” genres that pretend they’re not genres at all – may showcase a writer’s dexterity in manipulating a set of conventions; but coloring inside the lines poses real dangers to writers who have the chops to step outside those lines and find new ways to tell new stories – or old stories in new ways.

Tim Garvin’s A Dredging in Swann is engaging enough, but it might be something more than an entertainment (to borrow Graham Greene’s term) if it pushed harder against the conventions that govern category mysteries – or pushed past them altogether. The weakest stories in Michael Amos Cody’s The Twilight Reel likewise highlight the dangers of adhering to the protocols of its literary predecessors. When Cody puts down Dubliners and unlocks the prison cell of the quiet epiphany, more of his stories, like “The Flutist,” will find wings. It’s a utopian fantasy, but indulge yourself for a moment: imagine a bookstore not cordoned off by categories, a library of dreams where you might reach up to any shelf on any aisle, take down a volume, open up its pages, and find anything, anything at all. n

ABOVE Scuppernong Books in Greensboro, NC

2021 JAMES APPLEWHITE POETRY PRIZE FINALIST

BY J.S. ABSHER

Flower of Zeus

He had seven thousand sheep, three thousand camels, five hundred yoke of oxen, five hundred donkeys, and very many servants.—Job 1:3

Trellising the one rose, admiring the surviving verbena, deadheading the marigold, and watering the solitary peony

and four hellebore, 18 irises, 13 begonias (in pots and out), three pansies, spreading phlox and bugleweed;

caring for one son (far), one stepson (near), two elderberries, two kinds of mint, one kind wife to cling to

in pain and in peace, the Holy Spirit – all cultivated against ruin and despair: I ponder that man

who loved his herds and flocks, his sons and daughters, secure in his sense of rightness, of a life of plenitude and joy.

J.S. ABSHER is a six-time finalist whose first full-length book, Mouth Work (St. Andrews University Press, 2016; reviewed in NCLR Online 2017) won the 2015 Lena Shull Book Competition sponsored by the North Carolina Poetry Society. His work has been published in approximately fifty journals and anthologies, including Visions International, Tar River Poetry, and Southern Poetry Anthology, VII: North Carolina. He lives with his wife, Patti, in Raleigh, NC.

Viola, 2008 (photograph) by Meredith Hebden

A single day took it all from him, by theft and murder, by fire from heaven, by a gust of wind. These days I fear

one microbe, a fearful cop, an angry canceler’s lust to erase, one moment’s inattention at the wheel or in a friendship.

In prayers as short as breath, I offer up a bleeding heart, crushed muscadine and pink dianthus, flower of Zeus:

Purge me from fear and anger, give me a cheerful face, a heart of gladness and tender mercies, wisdom’s beginning.

MEREDITH HEBDEN is a botanic/floral art photographer, a horticulturist, and the gardens manager for Van Landingham Glen at UNC Charlotte Botanical Gardens. She studied at the University of New Hampshire and Oregon State University, and she received a BS in Photojournalism with a Botany minor from Northern Arizona University. Since 1993, she has been photographer in residence at Meredith Hebden Photography in Charlotte.

2021 JAMES APPLEWHITE POETRY PRIZE FINALIST

BY PRISCILLA MELCHIOR

Confederate Memorial Day

April 1958

Even the mules seemed tired, every bit as exhausted as the old men who drove the wagons, gray as the uniforms they wore to plod down Nash Street, heads bowed, solemn, righteous.

Children followed the parade, romping, teasing, summoned by the marching commands, the clop, clop of feet, utterly unaware of the reason for such a rare display of flags and guns, this march

for soldiers in a cause long disgraced. Few even paused to watch as they passed. Only the young would follow across town, giggling, dodging that which mules left behind, half interested until,

at last, the procession came to a halt at the graveyard, where faded headstones formed a battalion of memorials to men who took up arms against their country and called to their aging sons and grandsons to resurrect the past,

cover it with a veneer of honor and pride and ignore the irony of Taps as it lifted on the April air and drifted over the hill.

PRISCILLA MELCHIOR is originally from Wilson, NC. She is now a four-time finalist for the James Applewhite Poetry Prize, and her poems have previously appeared in NCLR 2017, 2018, and 2020. Throughout her career, she worked at various newspapers in eastern North Carolina, including The Daily Reflector. She retired to Highland County, VA, in 2011.

Boundless, 2021 (bronze sculpture, 16x7.5x3) by Stephen L. Hayes, Jr., Collection of Cameron Art Museum

STEPHEN L. HAYES, JR. was born in Durham and is an Assistant Professor at Duke University. He earned a BA at NCCU in 2006 and an MFA at Savannah College of Art and Design in 2010. He was the 2020 winner of the prestigious 1858 Prize for Contemporary Southern Art. The artist’s work has been featured at the National Cathedral, Rosa Parks Museum, and Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Art + Culture, among others. His art explores the African American experience, often incorporating historical context, as in his thesis exhibition, Cash Crop, which has been traveling and exhibiting for nearly a decade. Stephen L. Hayes, Jr. was commissioned by CAMERON ART MUSEUM to commemorate the United States Colored Troops (USCT), who fought for freedom and won the Battle of Forks Road in Wilmington, NC, the current site of the museum. The pivotal battle led to the fall of Wilmington, location of the last seaport of the Confederacy, and soon after, to the end of the Civil War. The life-sized bronze sculpture features eleven of the 1,600 soldiers, many from the region, whose faces were cast from present-day African American descendants of the soldiers, reenactors of the battle, veterans, and community leaders. Boundless was unveiled at Cameron Art Museum on 13 Nov. 2021. Read and see more on the museum's website.

Born Here (photography printed on canvas, 22x33) by Chris Foley

2021 JAMES APPLEWHITE POETRY PRIZE FINALIST

BY BENJAMIN PRYOR

The Ladder

Pa made a ladder from locust poles he cut in the pasture and hung it on the woodhouse wall. At twelve I propped it on the rancid tin and climbed the roof to view metropolis sheds of Hazelwood.

It seemed a trinket town of lockets and dead soldiers. Below, the creek was choked with leaves. The trees were close and I could jump and scale where squirrels nested, and take a baby in my hands and study hard

its plum of wrinkled face. But then my Ma would holler me down; the rusted roof might cave. Sheepish, I’d take the ladder Pa had built back to its iron nails. I’d find another way to sing above the town I knew.

CHRIS FOLEY was born in New York City’s Greenwich Village. He earned a BFA in painting and sculpture at Georgetown University. He also attended the School of Visual Arts in New York and the Visual Information Technology graduate program at George Mason University. His work has been exhibited internationally, including at Michihito Ohtagaki Gallery in Tokyo; Troyer Gallery in Washington, DC; and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD. He moved to the Asheville, NC, area in 2004, and is the owner and director of Haen Gallery in Asheville, as well as a second gallery location in Brevard, NC. BENJAMIN PRYOR is a native of Maggie Valley who now lives in Orange County, NC. He earned a BA in English from UNC Greensboro and an MFA in Poetry from the University of Florida and now works in IT and educational assessment in Chapel Hill. His writing has appeared in, among other venues, Oxford American, Southern Review, Cimarron Review, and Best New Poets 2010, as well as in NCLR 2005 and 2016. This is his second time as a finalist.

THE VITRUVIAN OUTLAW

a review by Jessica Martell

Neal Hutcheson. The Moonshiner Popcorn Sutton. Reliable Archetype, 2021.

JESSICA MARTELL is an Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at Appalachian State University. She is the author of Farm to Form: Modernist Literature and Ecologies of Food in the British Empire (University of Nevada Press, 2020) and co-editor of Modernism and Food Studies: Politics, Aesthetics, and the Avant-Garde (University Press of Florida, 2019). Her work has also appeared in a variety of scholarly journals and collections. Her current research explores transatlantic whiskey-ways in the UK, Ireland, and Appalachia. The Moonshiner Popcorn Sutton, a volume of photographs, essays, and interview transcripts, is part of Neal Hutcheson’s multidecade efforts to document the life and work of the famous Appalachian moonshiner Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton (1946–2009). Preceded by several films by the author about Sutton, this beautifully presented book is billed on the back cover as “the full story of the man behind the legend.”

Hutcheson is an author, filmmaker, and producer affiliated with the Language and Life Project at NC State University. His diverse range of films records lesser known but significant aspects of North Carolina cultures in transition, from Core Sound fisheries to mountain music. He has an abiding interest in language and has particularly focused on the struggles to preserve Appalachian, Black, and indigenous dialects and languages in the state. Interviewing people in the western North Carolina mountains about dialect initiated a working relationship with Sutton early in his career. The ensuing years spent shadowing Sutton shaped multiple projects that sought to bring the complexities of Appalachian culture to unfamiliar audiences, while documenting aspects of mountain life that are often perceived as passing out of recognition.

Sutton, a Haywood County native, remains one of the most famous moonshiners in the world. Known as an old-time craftsman with a dedication to quality, he became notorious as a colorful TV star who defied the law by running illegal shine on camera for a variety of documentaries, including Hutcheson’s early films. His operations straddled the border between North Carolina and Tennessee, a secluded area of the Blue Ridge that he knew intimately. The book touches on the important role that the Great Smoky Mountain National Park played in the gradual mainstreaming of moonshine, as tourists conditioned by stereotypical media representations of Appalachia came in search of “authentic” mountain culture. By “leaning-in” to the perceptions of outsiders (27), Sutton’s deliberately manufactured “hillbilly” aesthetic brought him fame and prosperity, and his iconic image left a legacy that continues to characterize legal moonshine marketing today.

Hutcheson’s early films were arguably vehicles that catapulted Sutton into the domain of reality TV. The Emmy-winning film The Last One (2009) and A Hell of a Life (2013) achieved cult status by introducing this Appalachian “outlaw” figure whose hostile relationship to

NEAL HUTCHESON is a filmmaker, author, and photographer. He has been the recipient of a North Carolina Arts Council Artist Fellowship, the North Carolina Folklore Society Brown-Hudson Award, and The North Carolina Filmmaker Award. His documentary films, including: Talking Black in America (with Danica Cullinan, The Language & Life Project, 2017), First Language: The Race to Save Cherokee (with Danica Cullinan, The Language & Life Project, 2015), both of which received regional Emmy awards. Core.Sounders: Living from the Sea (The Language & Life Project, 2013) also received an Emmy nomination. Land and Water Revisited (Empty Bottle Pictures, 2021) aired on PBS. He has also adapted Gary Carden’s stage plays The Prince of Dark Corners and Birdell for the screen. He is a founding member of Empty Bottle Pictures. He lives in Raleigh, NC.

mainstream American culture was also an implied subject of the works themselves. Sutton later appeared in moonshiner programs on PBS, CMT, the History Channel, and the Discovery Channel. After being sentenced to jail time while suffering from cancer, Sutton’s suicide in 2009 cemented his reputation as a legendary folk hero who would rather die than submit to government authority. The pain of this loss inflects Hutcheson’s essays, which investigate the boundaries between the man himself and the public image. Sutton was both “an archetypal mountain moonshiner, to the point of courting stereotype, and yet, remarkably real and present” (40).

Any documentarian seeking to represent marginal figures to a broader audience faces challenging ethical dilemmas and must guard against commodifying their subject. In this book, Hutcheson’s approach to depicting Sutton shows he is aware of the dangers. His introduction plus three essays labeled “Further Reading” take the time to outline some of the core concerns of the academic field of Appalachian Studies, wherein many writers have critiqued the exaggerated depictions of outlaws, hillbillies, and moonshine that court a national or global audience to the detriment of the region’s reputation. Hutcheson clearly states his belief that degrading Appalachian stereotypes are “a repulsive expression of inequitable power dynamics in the nation” (27). At the same time, what makes anything truly Appalachian is anything but clear, he notes. Sutton provides an apt subject to illustrate the complexity of the debate over authenticity.

One way that this book aspires to realism is to present Sutton in his own voice through extensive interview transcripts. The Sutton recorded here is humorous, barbed, and always seems to have the edge on those around him. From the rowdy threats on the signage of his property (“WHAT PART OF NO GOD DAM TRESSPASSING [sic] DON’T YOU UNDERSTAND . . . STAY OUT OR BE CARRIED OUT” [166]) to the carefully curated gravestone he commissioned several years before his death (“POPCORN SAID FUCK YOU” [167]), his X-rated gift of gab illustrates the signature quick wit undergirding his reputation, suggesting that the distinction between person and persona is smaller than one might think. The photographs help color myriad anecdotes and exhibit Sutton’s style.

Even as he intends to tell the “unvarnished facts” about the man he knew, Hutcheson describes the difficulty of leaving behind popular perceptions about him (29). His choice to make this struggle transparent lends the book its credibility, although some shortcomings are on display as well. The ratio of space devoted to evincing the large, boisterous public persona, especially by letting him speak so much, overshadows some unsavory details that linger long after the all-caps noise, exemplified above, have faded.

According to the author, Sutton was forthcoming about his ancestry but never discussed his own numerous family ties: “His life as a moonshiner was in fact tightly interwoven with a secret history of relationships, populated by women and children who have (for the most part) chosen to remain anonymous” (105). Sutton was a negligent father who denied his paternity or remained estranged from most of his children. In Daddy Moonshine (2009), his daughter’s account of failing to know her famous father, Sky Sutton writes, “He may be a phenomenal moonshiner but sadly he’s a complete loss as a father” (qtd. on 105). Without violating anyone’s anonymity, I wonder what else could have been done to expand the discussion of these less-than-heroic realities. What would it look like, post #MeToo, for a weighty contribution to the public record like this book to actually treat these “tightly interwoven” stories as central features of Sutton’s life and legacy (105), rather than as intriguing sidebars?

To his credit, Hutcheson does include them, acknowledging that not everyone who knew Sutton enjoyed his generosity like he did. Yet the choice to devote so much of the text to Sutton’s own words has the effect of omitting the fallout from the discomfort, and even trauma, his choices must have caused to those around him. The glimpses that this book provides into the domestic danger and turbulence of Sutton’s secret personal life – such as his insistence on showing polaroids of himself performing oral sex on an unidentified woman to anyone who entered his stillhouse, “whether they want[ed] to see them or not” (144–45) – creates an unsettling backdrop that, for many, will overshadow the masculinist focus on craft.

In contrast to so many accounts of Sutton, this book

takes a more measured approach to his legacy. If some fans are moved to declare Sutton “one of the last real men left in the world!!!,” or see his law-defying trade (ironically) as a “stand against the law to take care of family and neighbors,” Hutcheson contextualizes their remarks as romanticized notions from those who view Appalachia as the “embodiment of the best of traditional America” (qtd. 188). Scholars have long challenged such misunderstandings. The great rural theorist Raymond Williams warned against glorifying any lost Golden Age, which he famously called “a myth functioning as a memory.” As Mark Essig writes, the “mood-altering substance Popcorn peddled was not so much ethanol as an ersatz nostalgia.”* Yet nostalgia is hard to shake. Even the first preface of this book, written by David Joy, mourns the loss of a golden age of old timers, declaring Sutton’s Appalachia “a culture on the brink of extinction” (17). To declare it a loss is to deny the privilege of modernity to a region in flux – a region that is still very much alive, even as its identities multiply, its composition diversifies, and its people produce new, more inclusive cultural forms to market to curious outsiders.