NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE OF NORTH CAROLINA

FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE Interview

n

n

n

more n n n

with Red Justice Project Podcasters

Poetry by Mary Leauna Christensen

Book Reviews

and

WINTER 2023 ONLINE NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW

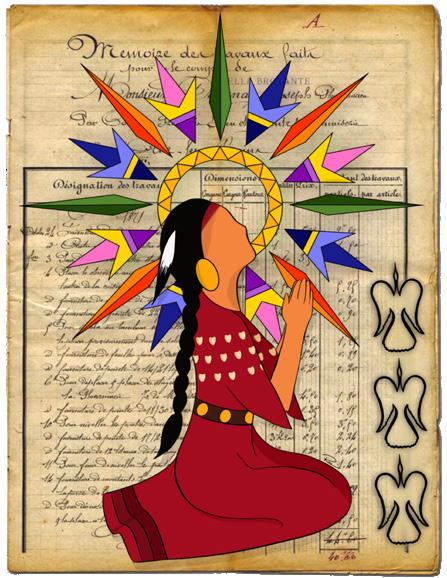

COVER ART

Medicine Woman (oil on canvas, 32x56)

by Gene Locklear

by Gene Locklear

Cover artist GENE LOCKLEAR was born in Lumberton, NC, raised in nearby Pembroke, and is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. After a career in the Major Leagues, he turned to painting full time. His work has been exhibited widely, and his numerous art commissions have come from the White House, the Pentagon, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the NFL, prominent sports figures, as well as Turner Broadcasting. Currently, he lives and works in California and maintains a studio and gallery in El Cajon, a suburb of San Diego. In 2004, he helped establish an art academy for young people at UNC Pembroke, where an endowed art scholarship has been established by friends in his name.

COVER DESIGNER

NCLR Art Director DANA EZZELL

LOVELACE is a Professor at Meredith College in Raleigh. She has an MFA in Graphic Design from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. Her design work has been recognized by the CASE Awards and in such publications as Print Magazine’s Regional Design Annual, the Applied Arts Awards Annual, American Corporate Identity, and the Big Book of Logos 4. She has been designing for NCLR since the fifth issue, and in 2009 created the current style and design. In 2010, the “new look” earned NCLR a second award for Best Journal Design from the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. In addition to the cover, she designed the feature interview with the podcasters, the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame story, and the creative nonfiction by Kielar and Memory in this issue.

Produced annually by East Carolina University and by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association © COPYRIGHT 2023 NC LR

NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW

WINTER 2023 ONLINE

NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE OF NORTH CAROLINA

6 n Native American Literature of North Carolina includes an interview, poem, and book reviews

Cherry Beasley

Kimberly L. Becker

Mary Leauna Christensen

Brittany Hunt

Mary Ann Jacobs

Chelsea Locklear

Lynn Norris Murray

Jennifer Peedin

Kirstin L. Squint

Ulrike Wiethaus

26 n Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues includes poetry, prose, book reviews, and literary news

Anthony Abbott

J.S. Absher

Heather Bell Adams

Malaika King Albrecht

Dale Bailey

Micki Bare

Joseph Bathanti

Barbara Bennett

Jim Clark

Sheryl Cornett

Annie Frazier Crandell

David Deutsch

Judy Allen Dodson

Morrow Dowdle

Janet Ford

Charles Frazier

Philip Gerard

Donna A. Gessell

Rebecca Godwin

Bill Griffin

Jim Grimsley

Janis Harrington

Debra Kaufman

John Kessel

Blaise Kielar

Erica Plouffe Lazure

Patti Frye Meredith

Valerie Nieman

David Potorti

Mark Powell

Glenis Redmond

Maureen Sherbondy

Marty Silverthorne

92 n North Carolina Miscellany includes poetry, prose, and book reviews

Astrid Bridgwood

Cindy Brookshire

Spencer K.M. Brown

Almyr L. Bump

Diane Chamberlain

Sharon Colley

Alana Dagenhart

Joanne Durham

Betina Entzminger

Jo Ann S. Hoffman

Lockie Hunter

Anna McFadyen

n North Carolina Artists in this issue n

Denise Baker

Jody Bradley

Margaret Balzer Cantieni

Brandon Cordrey

Alana Dagenhart

Horace Farlowe

Paul Gemperline

Alex Harris

Krista Harris

Kyle Highsmith

Robert Langford

Chris Liberti

Janna McMahan

Ashley Memory

Patti Frye Meredith

Jamal Michel

Monica Carol Miller

Megan Miranda

Gene Locklear

Tim Lytvinenko

Peter Marin

Lee Nisbet

Dimeji Onafuwa

Ann Roth

Ann Cary Simpson

Bland Simpson

Max Steele

Marsha White Warren

Carol Boston Weatherford

Eric Weil

Leah Weiss

Ross White

Luke Whisnant

Lee Zacharias

Anne Myles

Elaine Thomas

Judith Turner-Yamamoto

Cheryl Wilder

Liza Wolff-Francis

Annie Woodford

Donald Sexauer

Ralston Fox Smith

Leah Sobsey

Theodorus Stamos

Raven Dial Stanley

Carrie Tomberlin

IN

THIS ISSUE

North Carolina Literary Review is published annually in the summer by the University of North Carolina Press. The journal is sponsored by East Carolina University with additional funding from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. NCLR Online, published in the winter and fall, is an open access supplement to the print issue.

NCLR is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals and the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses, and it is indexed in EBSCOhost, the Humanities International Complete, the MLA International Bibliography, and the Society for the Study of Southern Literature Newsletter.

Address correspondence to Dr. Margaret D. Bauer, NCLR Editor

ECU Mailstop 555 English Greenville, NC 27858-4353

252.328.1537 Telephone

252.328.4889 Fax

BauerM@ecu.edu Email NCLRstaff@ecu.edu

https://NCLR.ecu.edu Website

NCLR has received 2022–2023 grant support from the North Carolina Arts Council, a division of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, and from North Carolina Humanities

Subscriptions to the print issues of NCLR are, for individuals, $18 (US) for one year or $30 (US) for two years, or $30 (US) annually for institutions and foreign subscribers. Libraries and other institutions may purchase subscriptions through subscription agencies. Individuals or institutions may also receive NCLR through membership in the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. More information on our website

Individual copies of the annual print issue are available from retail outlets and from UNC Press. Back issues of our print issues are also available for purchase, while supplies last. See the NCLR website for prices and tables of contents of back issues.

Submissions

NCLR invites proposals for articles or essays about North Carolina literature, history, and culture. Much of each issue is thematically focused, but a portion of each issue is open for developing interesting proposals, particularly interviews and literary analyses (without academic jargon). NCLR also publishes high-quality poetry, fiction, drama, and creative nonfiction by North Carolina writers or set in North Carolina. We define a North Carolina writer as anyone who currently lives in North Carolina, has lived in North Carolina, or has used North Carolina as subject matter.

See our website for submission guidelines for the various sections of each issue. Submissions to each issue’s special feature section are due August 31 of the preceding year, though proposals may be considered through early fall.

Issue #33 (2024) will feature NC Disability Literature, guest edited by Casey Kayser

Issue #34 (2025) will feature NC LGBTQ+ Literature, guest editor TBA

Issue #35 (2026) will feature NC Mysteries and Thrillers, guest edited by Kirstin L. Squint

Please email your suggestions for other special feature topics to the editor.

Book reviews are usually solicited, though suggestions will be considered as long as the book is by a North Carolina writer, is set in North Carolina, or deals with North Carolina subjects. NCLR prefers review essays that consider the new work in the context of the writer’s canon, other North Carolina literature, or the genre at large. Publishers and writers are invited to submit North Carolina–related books for review consideration. See the index of books that have been reviewed in NCLR on our website NCLR does not review self-/subsidy-published or vanity press books.

4 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

ISSN: 2165-1809

EDITORIAL BOARD

Jenn Brandt

Women’s Studies, California State Unviersity

Dominguez Hill

Gina Caison

English, Georgia State University

Amanda Capelli

Expository Writing Program, New York University

Catherine Carter

English, Western Carolina University

David S. Cecelski

Historian, Durham, NC

Celestine Davis

English, East Carolina University

Kevin Dublin

Elder Writing Project, Litquake Foundation

Editor

Margaret D. Bauer

Art Director

Dana Ezzell Lovelace

Guest Feature Editor

Kirstin L. Squint

Poetry Editor

Jeffrey Franklin

Art Editor

Diane A. Rodman

Founding Editor

Alex Albright

Original Art Director

Eva Roberts

Graphic Designers

Karen Baltimore

Stephanie Whitlock Dicken

Senior Associate Editor

Christy Alexander Hallberg

Assistant Editors

Anne Mallory

Randall Martoccia

Senior Editorial Assistant

Megan Smith

Editorial Assistants

Cassidy Barbee

Keegan Holder

Daniel C. Moreno

Interns

Lauren Cekada

Ashley Mills

Rebecca Duncan

English, Meredith College

Gabrielle Brant Freeman

English, East Carolina University

Jaime Rochelle Herndon

Freelance writer, Philadelphia, PA

LeAnne Howe

English, University of Georgia

Mark Johnson

English, East Carolina University

Kathryn Kirkpatrick

English, Appalachian State University

Celeste McMaster

English, Charleston Southern University

Kat Meads

Red Earth MFA program, Oklahoma City University

Tariq Moore

English, East Carolina University

Amber Flora Thomas

English, East Carolina University

Angela Raper

English, East Carolina University

Dean Tuck

English, Wayne Community College

Susan O’Dell Underwood

English, Carson-Newman University

Robert West

English, Mississippi State University

5 N C L R ONLINE

Spotlighting North Carolina’s Indigenous Voices

by Kirstin L. Squint, Guest Feature Editor

by Kirstin L. Squint, Guest Feature Editor

I was thrilled when NCLR Editor Margaret Bauer asked me to assume the role of the journal’s first guest feature editor, and it is my great honor to introduce the 2023 special feature section on Native American literature of North Carolina. I conduct research and teach graduate and undergraduate classes in this area, particularly work by Southeastern Indigenous authors, so I knew that this was a topic I wanted to explore in NCLR, especially because North Carolina “has the largest American Indian population east of the Mississippi River.” 1 Also, within the broad category of Native American literature, Southeastern Indigenous literatures have been less well-known to the general public and less studied by scholars, despite the long history of oral and written work by the people who have lived on this land for millennia.

We begin the feature section of this first 2023 issue with an interview I conducted in 2021 with Lumbee podcasters and storytellers, Brittany Hunt and Chelsea Locklear, whose Red Justice Project true crime podcast, now in its second season, highlights cases of missing and murdered Indigenous peoples in North Carolina and beyond. This is important work because so often these stories remain untold by mainstream media.

We are also excited to include Mary Leauna Christensen’s powerful poem about the complexity of Indigenous identity, “In Which I am The Sum of Parts.” Christensen, a citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, is a 2022 Indigenous Nations

Poets fellow and attended the inaugural In-NaPo retreat in Washington DC. We look forward to including another of her poems in our forthcoming print issue.

In addition to my interview with Hunt and Locklear and Christensen’s poem, Lynne Norris Murray reviews the collection, Upon Her Shoulders: Southeastern Native Women Share Their Stories of Justice, Spirit, and Community, edited by Cherry Beasley, Mary Ann Jacobs, and Ulrike Wiethaus. In her review, Murray details how the North Carolina tribal women featured in the book tell their stories, illuminating service to their communities, Indigenous spiritual practices, and initiatives for justice. Also reviewed is Bringing Back the Fire by Cherokee-descended author Kimberly L. Becker. In her review of this poetry collection, Jennifer Peedin describes how Becker contrasts imagery of light and darkness and weaves Cherokee language through her work to emphasize themes of pain and solace, especially as they relate to her own Cherokee ancestry. These reviews, as well as the interview and poetry, are punctuated with stunning artwork by Raven Dial-Stanley (Lumbee) and Jody Bradley (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians).

The winter online issue provides a taste of what is to come in the 2023 print issue,2 which will include creative writing by Cherokee and Lumbee writers, including Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, Mary Leauna Christensen, and Tanya Holy Elk Locklear. We will also feature literary criticism by

6 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

2

the

of contents of the 2023 issue here

Find

table

scholars of Indigenous and US Southern literatures about Cherokee, Lumbee, and Catawba texts, and an interview with Cherokee novelist Blake Hausman. And throughout the feature section, artwork by North Carolina Native artists from the Lumbee, Eastern Band of Cherokee, and Catawba tribes will complement the writing. Be sure to subscribe to NCLR, if you don’t already, to receive this historic issue, the first to focus on North Carolina Native American literature.

Finally, I want to share East Carolina University’s land acknowledgment, a way that we recognize North Carolina’s tribal communities at campus events: “We acknowledge the Tuscarora people, who are the traditional custodians of the land on which we work and live, and recognize their continuing connection to the land, water, and air that Greenville consumes. We pay respect to eight recognized tribes: Coharie, Eastern Band of Cherokee, Haliwa-Saponi, Lumbee, Meherrin, Occaneechi Band of Saponi, Sappony, and Waccamaw-Siouan, all Nations, and their elders past, present, and emerging.”

Our 2023 NCLR feature theme is another way of acknowledging the importance of North Carolina’s Indigenous peoples and their continuing contributions to North Carolina literature. n

Native American Literature of North Carolina NORTH CAROLINA

8 The Red Justice Project: An Interview with Brittany Hunt and Chelsea Locklear by Kirstin L. Squint art by Raven Dial-Stanley

20 Taking Up the Mantle and Making it Her Own a review by Lynne Norris Murray art by Raven Dial-Stanley

n Cherry Beasley, Mary Ann Jacobs, Ulrike Wiethaus, eds. Upon Her Shoulders: Southeastern Native Women Share Their Stories of Justice, Spirit, and Community

22 In Which I Am a Sum of Parts a poem by Mary Leauna Christensen art by Jody Bradley

24 Re-membering the Dark and the Light a review by Jennifer Peedin art by Jody Bradley

n Kimberly L. Becker, Bringing Back the Fire

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

26 n Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues poetry, prose, book reviews, and literary news

92 n North Carolina Miscellany poetry, prose, and book reviews

7 N C L R ONLINE

THE RED JUSTICE PROJECT

BY KIRSTIN L. SQUINT

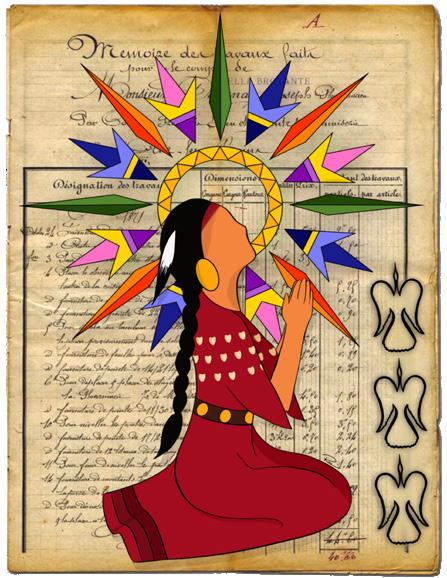

RAVEN DIAL-STANLEY , the artist featured here, is an enrolled member of the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina. She graduated from UNC Greensboro with a degree in consumer, apparel, and retail product design and a minor in new media design studies. She was the president of the Native American Student Association and was inducted into Alpha Pi Omega Sorority, the first Native American sorority in the US. In 2018, she was selected as Miss Indian North Carolina, and in that role, served as an ambassador for all eight tribes and four organizations in North Carolina. Her platform was “Empowered Woman, Empower Women.” She also volunteers for the Indian Education Program in her community. See more of her art on Instagram @artistry_indigenous_angel.

The following is a Zoom interview that took place on November 16, 2021, as part of a lecture series hosted by Kirstin L. Squint, Whichard Distinguished Professor and Native American literature specialist in the Department of English at East Carolina University.1 The conversation focuses on the groundbreaking podcast, The Red Justice Project, co-hosted by Brittany Danielle Hunt and Chelsea Locklear, both citizens of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. The podcast spotlights the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous peoples in North Carolina and beyond. This interview has been edited for reading and style, but carefully, to remain true to the speakers’ voices. Squint’s conversation with Hunt and Locklear focused on the mission of the podcast, which is to bring awareness to the many cases of missing and murdered Indigenous people in North America and the way they are erased in American media. The interview also addressed Hunt’s and Locklear’s choices about how to tell the victims’ stories, particularly from an Indigenous point of view. Season One of The Red Justice Project launched on November 2, 2020, and its twenty-nine episodes aired weekly until June 14, 2021. Season Two, launched on April 24, 2022, and its ten weekly episodes concluded on July 25, 2022. At the time of this interview, The Red Justice Project was on a break between its first and second season.

Brittany Hunt is currently a postdoctoral research associate at Duke University and the owner of Indigenous Ed., LLC, through which she provides workshops, speeches, and consulting around Indigenous education. She is the author of the Lumbee children’s book, Whoz Ya People? and is a graduate of Duke, UNC Chapel Hill, and UNC Charlotte. Chelsea Locklear was raised in Pembroke, North Carolina, and is also a member of the Lumbee tribe. By day, she is a Client Services Manager for a private credit fund, and by night she’s a dreamer and schemer, planning her next passion project. She received her bachelor’s degree from NC State and an MPA from UNC Chapel Hill.

8 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

1 Watch this interview with the podcasters online here. The transcription that follows has been edited for a reading audience.

: : :

:

AN INTERVIEW WITH BRITTANY HUNT AND CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

KIRSTIN L. SQUINT: I read in the local newspaper in Robeson County, North Carolina, The Robesonian, in January of this year that The Red Justice Project was Chelsea’s brainchild because of your love for the true crime genre, and that Chelsea got Brittany hooked on true crime podcasts as well. Chelsea mentions in the first of the twopart story about Julian Pierce, episodes six and seven, that this was the first case the two of you discussed.2 How did you two meet, and what made you decide to become a podcasting team?

Missing & Murder Indigenous Awareness, 2020 (virtual drawing/painting, 8.5x11) by Raven Dial-Stanley

The premiere guest editor of NCLR, collecting and editing content for the feature section of the 2023 issues, KIRSTIN L. SQUINT is an Associate Professor of English at East Carolina University, where she held the Whichard Visiting Distinguished Professorship in the Humanities from 2019 to 2022. She is the author of LeAnne Howe at the Intersections of Southern and Native American Literature (Louisiana State University Press, 2018), a co-editor of Swamp Souths: Literary and Cultural Ecologies (Louisiana State University Press, 2020), and the editor of Conversations with LeAnne Howe (University Press of Mississippi, 2022). She is also a contributor to Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy (West Virgina University Press, 2019), winner of the 2020 American Book Award for criticism.

CHELSEA LOCKLEAR: Well, I like to say, like any good love story, we met online, mostly because that’s how I met my husband, also. I think we met through social media. Brittany always shared some really insightful posts, and she has been a voice for Lumbee people for several years via social media. She’s very funny and just a really great energy, and so I reached out to her with my idea, and it kind of took off from there.

Did you want to add anything to that, Brittany?

BRITTANY HUNT: Oh, no. I would just say that she mentioned earlier how we met on social media, and also she met her husband there, and we’re both the two great loves of her life, in addition to her daughter. It’s been an honor to work with Chelsea so far on this journey. I wasn’t into podcasting at all, and now I listen to two to three different shows a day, based on Chelsea’s recommendations mostly, and so she really pulled me into the podcast world. I think it’s a tremendous format through which to share stories, which Indigenous people love to do. It feels very familiar to me, so I’m thankful for Chelsea for that.

9 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

2 Julian Pierce was a Lumbee attorney and activist. Episodes 6 and 7 were released 14 and 21 Dec. 2020.

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

: :

COURTESY OF BRITTANY HUNT AND CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

You describe what you do on The Red Justice Project as telling the stories of the victims. What storytelling techniques do you use to create a compelling experience for your listener? I remember in the Jap Locklear episode you talked about the oral tradition, and you also talked about the way podcasting intersects with that.3

BH: So, one of the things that I think we noticed in doing a lot of our research on the cases is that sometimes the cases aren’t treated with as much sensitivity as they should be given, and so we really like to bring a lot of sensitivity to the work, even though we are describing a lot of graphic content most times. That’s really important for us. We also like to, as much as possible, inject humor into the beginning of the episodes because the topics are really heavy, and so we do like to provide a little bit of comic relief in the beginning for our listeners because even though these stories are traumatic, we know that as Indigenous people we often use humor to deal with trauma in a lot of ways. I think Chelsea and I do that as much as possible in the stories.

So, Chelsea, you got Brittany into podcasting. Is that something that appeals to you as well, that kind of storytelling aspect of it, or the orality of it, I guess?

CL: Yeah, as Brittany mentioned, I think Indigenous people are known for their storytelling and oral history, and through my love of true crime podcasts, I was noticing that a lot of our stories, Indigenous stories, were not being told. Once again, I already knew we weren’t being shown in the media; we weren’t frequently featured on episodes of Dateline, of 48 Hours, of other kinds of true crime shows that you might see, or even just your nightly news. And when I was looking through different podcasts, I thought, we really are not being featured in podcasts, either, of true crime, considering the devastating rates at which we go missing and are murdered. I’m not a storyteller by nature, but I thought, there’s a gap. Why not fill it, or try to?

You know I’m a literature professor, and I think about storytelling a lot, and I got so hooked on this podcast. One of the things that I’m often impressed by is your rapport. You are both so genuine and so funny at times. In the episodes on Julian Pierce, you’re talking about that period in the ’80s when there was so much police and political corruption in Robeson County. You describe how two Tuscarora men took over The Robesonian as an act of political dissidence. I laugh out loud every time I listen to this episode when Chelsea joked that if she had been taken hostage, she would have been happy to have been traded for a

10 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

3 Jap Locklear was a Lumbee man whose case was discussed in episode 12, released 25 Jan. 2021.

. . . INDIGENOUS PEOPLE ARE KNOWN FOR THEIR STORYTELLING AND ORAL HISTORY, AND THROUGH MY LOVE OF TRUE CRIME PODCASTS, I WAS NOTICING THAT A LOT OF OUR STORIES, INDIGENOUS STORIES, WERE NOT BEING TOLD.

collard sandwich.4 You can pick out moments where you all are really funny, and I often think, “Wow, how did you make me laugh after telling me this terrible story that needs to be told?” But there are also really poignant moments, like during the interview about Marcey Blanks when Brittany is talking to her mother, and she cries with her on the phone because it’s so traumatic.5 I think you’re both really brave to take on this subject matter. Do you think of yourself that way? You know you are taking on really challenging stuff.

CL: I would not call myself brave. I’d say a little bit foolish to begin with because Brittany and I had no idea what we were getting into. We had no idea the conversations that we would be having with people, the depth of the conversations, and the effect that creating a podcast like this would actually have on us and on our community that actually listens to it. So, I don’t know if “brave” is the right word; I’ll throw in some foolery there at the beginning. But what do you think, Brittany?

BH: I agree with “brave” and “foolish” mixed together. Because some of the stories we’re telling are kind of scary to tell, especially cases where there’s not been any suspect that’s been apprehended, but there are rumors around town of who did it. Should we share those rumors? Should we not? How much protection do we need to give the people who we’re talking to, but also protection for ourselves? There is a level of fear, I think, associated with some of the stories that we’ve told in the past. I think it does take a combination of bravery and foolishness together. The interview with Marcey’s mom, Ms. Mary, was the most difficult interview I’ve ever done. I knew Marcey, so that added a whole other layer to it because I hadn’t known any of the other victims. I cried with her in a very genuine way because of something that she said that just broke my heart. That episode and that story is the closest one to me of all. I think it also takes a little bit of gumption, or strength, to be able to even interview family sometimes because some of the things that they’re telling us are so difficult to hear and so beyond what you could even think a human could endure.

I agree. We’ll come back to the Marcey Blanks episode in just a bit. I was researching what other folks had been saying about The Red Justice Project, and I came across some reviews on a website I had never seen before called Podbay. There were thirty-five reviews. They were all five-stars, of course. There was a review that really touched me because it reflected my own experience. It was by a listener called “DoomerVibes” who said, “I’d recommend

11 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

4 On 1 Feb. 1998, two Native American men protested “unfair law enforcement” in Robeson County by taking hostages at the office of the The Robesonian newspaper. See Donna Gordon, “American Indians Seize Hostages at Newspaper,” Associated Press 1 Feb. 1998: web

5 Marcey Blanks (1998–2016) was a Lumbee woman whose case was discussed in episode 11, released 18 Jan. 2021.

ABOVE Marcey Blanks

COURTESY OF BRITTANY HUNT AND CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

this to anyone, but for North Carolinians, especially, this is a must listen. The dedicated hosts provide invaluable information about Lumbee culture, which is completely omitted from our education, packaged in a bingeable true crime format.” 6 I think all that is true. When I started listening, I started bingeing, but then there was a moment when I had to stop because some of these stories you’re telling are terrifying just to listen to, let alone to try to put yourself in the shoes of the family members of these victims as you all are doing. I feel like I need to process sometimes. I know there are times when you pause while you are actually doing the podcast, and you say, “I had to pray after I read this,” or “I’m going to have to smudge myself.” How does regularly reading about and researching these cases affect you emotionally? Do you ever take a step back and say, “That’s enough work on the podcast today. I need a break”?

BH: We had initially planned to set our podcast up in the same way that Crime Junkie does.7 For people who aren’t familiar with that podcast, they pretty much air every single Monday. But then over time, Chelsea and I started to realize that it was just too hard on us emotionally because, again, we’re telling stories of people we know. Some of the people Chelsea went to school with, and it’s people who lived on the same street as us or lived in the same community. It’s a whole different type of connection that we have to the cases than a typical true crime podcaster would have. So, we decided to start doing our podcast in seasons instead. We finished Season One in June, I believe, and decided to take a pretty long break, much to the anger of some of our fans, who have been messaging us, asking us for Season Two. But I think that we needed a break – mentally, emotionally – from some of the content that we were sharing. And then again, just as a reminder, we’re not just reading articles. We’re talking to family members, which adds a whole other level of pain, even for us in a second- or third-degree way. We had to take a break for our own mental health. And we’re also thinking of maybe potentially a different format for Season Two for that reason alone.

How has your process changed as you moved through Season One? In episode ten, you said you had to record your first episode so many times. And you were so experienced sounding by that point. I am curious, for example, thinking about the interviews with family, what are some of the things that changed and what did you learn throughout the season?

CL: Each episode we learned something that helped us out with the next episode. When we first started – the Brittany Locklear episode was our very first episode – and Brittany and I probably recorded that six or seven times to try to get it right, maybe even more.8 And

12 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

1,

2

6

the reviews page of

Project website. 7

is a true crime podcast that debuted in Dec. 2017: web ABOVE

ABOVE BOTTOM

8 Brittany Locklear (1992–1998) was a Lumbee girl whose case was discussed in episode

released

Nov. 2020.

Quoted from

The Red Justice

Crime Junkie

TOP Chelsea Locklear

Brittany Hunt

COURTESY OF CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

COURTESY OF BRITTANY HUNT

WE QUICKLY REALIZED BY EPISODE THREE OR FOUR THAT IF WE WANTED TO COVER MORE STORIES, ESPECIALLY IN OUR COMMUNITY, WHERE THE LOCAL NEWSPAPER OR LOCAL TELEVISION STATION HAD NOT COVERED THOSE CASES THOROUGHLY, WE ACTUALLY HAD TO SPEAK TO FAMILIES.

we actually wrote the script together; whereas, in later episodes we would take turns writing scripts, so it wouldn’t be such a burden on us each week. But I think we realized pretty early on, because of the type of podcast that we had, an Indigenous true crime podcast, where there’s not a lot of media coverage, that it actually was up to us to create that media and that was really through interviews with families. We quickly realized by episode three or four that if we wanted to cover more stories, especially in our community, where the local newspaper or local television station had not covered those cases thoroughly, we actually had to speak to families. That changed our mindset once we learned that we would have to do that. And it really changed the tone of the podcast because we couldn’t just binge newspaper articles and write a quick script. We really had to take our time and think about questions like, Who do we interview? What questions do we ask? How sensitive do we need to be with these family members? What can we cover? What can we not? As Brittany said, some of them tell you things like, “Please do not say this in the podcast,” even though it would be something really interesting to the audience. You have to honor those wishes. I think with each episode in Season One, it was a learning curve for us. But it was a good experience leading up to Season Two for us.

I have been very interested in the craft of it. How much time does it take for you to write an episode? I imagine that’s also changed.

BH: It just depends because sometimes there’s more information about one case than others, and sometimes family members haven’t gotten a chance to talk about their loved ones in a while to anybody, so they’ll talk for longer, maybe, than other interviews where a family member doesn’t want to share so much. But usually if we have, for example, a twenty-five-minute episode, that would be about twelve pages of a script. Writing that does take several hours to do. It is a pretty laborious process. But there have also been times when the way Chelsea and I will do it is we’ll record separately or on Zoom. But there were a few times when her recording didn’t work, so we didn’t know until the end, and we had to do it over and over again. And those were times when I wanted to fight Chelsea, which I never told her until now. But that only happened a few times. Generally, I would say it takes five to six or seven hours to write a story, and then recording it might take another hour or so. Then Chelsea’s husband is the one who edits and cuts and puts our episodes together, so he has to do quite a bit of work on that as well, especially if we mess up a lot while we’re recording. He’ll have to go through and delete.

CL: Which is often.

13 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

Do you have the whole season ready before you release it?

CL: We were really working on the fly during Season One. Season Two we are planning out much better. I don’t think we realized how much traction we would get with Season One, and I couldn’t even imagine that we would turn out basically thirty episodes over a six-month period. That’s pretty hefty for one season of a podcast, thirty episodes. Also, that gives my husband a break from editing.

That’s a lot of work, especially on top of your regular jobs. On that note, that Robesonian article I read from January said that your reach was across twenty-five states at that point, but I’m sure it’s much different now.9 Do you know how many listeners you have, or do you measure that by downloads? What do you know about your audience?

CL: I actually had not looked up the stats in a while. I looked them up and shared them with Brittany yesterday. We’ve reached fifty-five countries! Granted, some countries only have ten downloads, but we’ll count it, and forty-four states. It’s gotten quite a bit of a reach across the US now, which is exciting.

That is exciting! Thinking about those early episodes, I love the way that you say, “This is what Lumbee is; this is who we are; you’ll notice our Southern accents.” Even at that point when you didn’t realize the reach you would have, you prepared everybody. I think that’s fantastic. I guess I’m wondering: did you have that vision or that hope that you would get an international reach?

BH: I think we had that hope. And Chelsea didn’t mention, but we also have forty-four thousand downloads total of the podcast, so it’s a lot more than I thought we would ever get. I’m really excited that not only are North Carolinians and Robesonians listening to the podcast, but people all over the world and all over the country as well. I don’t think we had anticipated it, but it was definitely something we hoped for. It’s good to see that it’s realized.

That’s excellent news. In terms of thinking about the content and the way it connects to that reach, The Red Justice Project examines many cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, especially Lumbee women, but you also discuss missing and murdered Indigenous people more broadly in North Carolina and beyond US national borders. I’m thinking about Canada’s Highway of Tears, which are episodes nine and ten, and episode twenty-eight about the bodies of 215 children that were found on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia.10 They were found last May, so I think folks will remember that in the news. These were just very powerful. Can you talk a little bit about how you chose the scope of your podcast?

14 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

10 Episodes 9, 10, and 28 were released 4 and 11 Jan. and 7 June 2021.

9 Tomeka Sinclair, “Hosts of ‘Red Justice Project’ Seek to Raise the Voices of Slain, Missing Indigenous People,” Robesonian 22 Jan. 2021: web

ABOVE Chelsea Locklear’s husband, Dakota Lowery

COURTESY OF CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

CL: I think when we first started, our idea was to be pretty broad, which is why our second episode was about Neil Stonechild, which was based in Canada as well.11 We had several other episodes that were across the US, but we really found that we got more listeners and more engagement, especially on social media, when we talked about cases specific to our community. One, because thankfully we have friends and family who are nice enough to listen to our podcast, but really because these stories had never been told in this format and really had hardly been told in the media. With Marcey’s case, as Brittany can tell you, there were about three or four news articles, very small, and most people wouldn’t have even known about what had happened, so we really found that people were most interested in the cases they had never heard of. There are other bigger cases, like Kamloops, that were really relevant because it did actually make some national media attention.Since then, several more residential schools in the US and in Canada have been investigated. They did ground radar penetration, and they’ve actually uncovered several thousand more bodies of Indigenous children. There has been nothing in the media, which was really sad because at least Kamloops did make national media, but since then none of the other schools have even made a blip really on national news.

BH: And I would just like to add another comment about what Chelsea was saying earlier. I think our listeners have really enjoyed listening to cases that were in our community but they didn’t know about because they’re getting so few articles. There was even one story that we covered of a girl named Casey Young, who I went to school with.12 One of my friends who I was telling about the episode knew Casey and had not known that she had died in 2009. At this point it had been eleven years, and she didn’t even know that Casey had passed away, so finding out that way with me telling her about us covering her story highlights the ways that these stories are covered up or hidden in our communities or in our local news media. They’re not really talked about as much as they definitely should be.

Sometimes you talk about particular roads where several crimes have taken place, and sometimes it’s a revelation to you that so many crimes have taken place in one area. I’m often amazed when you talk about how – and this happened in several different episodes – the victim had just one line in the newspaper. There’s a real honoring of these folks that’s happening in your episodes, which I think is moving, from a listener perspective. I would like to talk some more about Marcey Blanks. This is such a powerful story. It’s so powerful because the victim was a student Brittany knew when she worked at Lumberton High School. Brittany shared firsthand memories of Marcey, as well as the pain she experienced from her loss. I think this episode is also very important because you’ve underscored how murders of Indigenous women are much less publicized than those of

15 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

11 Episode 2 about the case of Neil Stonechild was released 9 Nov. 2020.

12 Casey Young was a Lumbee woman whose case was discussed in episode 13, released 1 Feb. 2021.

I THINK OUR LISTENERS HAVE REALLY ENJOYED LISTENING TO CASES THAT WERE IN OUR COMMUNITY BUT THEY DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT BECAUSE THEY’RE GETTING SO FEW ARTICLES.

white women. And this is certainly true of your first episode about Brittany Locklear, which is a truly horrifying case of a very young girl, and you talk about some comparisons to JonBenét Ramsey and some others who made national media. Would you talk about the ways you’re trying to amplify this issue and humanize the statistics around missing and murdered Indigenous women?

COURTESY OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF ROBESON COUNTY STAFF

BH: For me, in researching these cases and in talking with families, and also being a person who does consume a lot of true crime media in general, either through podcasts or Dateline episodes, you see the ways the cases in our home communities are almost identical to some of the cases that are really popular, for example JonBenét Ramsey. There’s also a woman named Jessica Chambers, who was murdered in Mississippi, I believe, and her body was burned, but she lived just long enough to name the person who had killed her, and then she died shortly after. Marcey’s case was very similar in that she had been stabbed repeatedly and was burned and then named her assailant. But Marcey’s case got three articles that were maybe five sentences total. And Jessica Chambers’s case ends up getting a special on the Oxygen network that’s eight parts, and now it’s a podcast.

Our issue is not that white women don’t deserve coverage; it’s just that Indigenous women and girls deserve the same level of coverage and that the purposeful covering up of these cases is adding to the problem that’s happening in our community. There’s a common phenomenon called “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” which describes the way our nation, and even the world, becomes captured by the stories of missing and murdered white women. Think of Laci Peterson, JonBenét Ramsey, Natalee Holloway, so many different women’s stories we know in detail. It makes you sympathize and empathize with that family. But then you don’t have that complementary coverage of Native women, so there’s no one who is empathizing and sympathizing with us, which makes the problem even worse. I think that’s why our podcast is so important, not only to us, but to our community, as well.

CL: Another great example of that that’s super recent is Gabby Petito. The whole nation and social media were enthralled with her. She was a young white girl, very pretty, trying to make it as a social media influencer. She went missing in Wyoming, where several hundred Indigenous women have gone missing. And there’s been no blips, no thousands of TikToks or Instagram posts wondering where these Indigenous women are, like you saw with Gabby Petito. What causes America to rise up for Gabby Petito, and how can we get that same rise for Indigenous women, as well?

16 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

Let’s talk about Faith Hedgepeth because her story does also tie into this issue that we’re talking about right now. Your season finale is just absolutely powerful from beginning to end.13 You have a beautiful song at the end, “Hometown Hero” by Charly Lowry. A lot of folks in North Carolina are probably familiar with the very horrific murder of Faith Hedgepeth. She was a Haliwa-Saponi woman and a UNC student whose body was found in 2012. This case is a rarity because it has had some national attention, and it did make state-wide headlines again in August of this year because a suspect was finally arrested. Your storytelling in this episode is powerful for a lot of reasons, but I think part of it is because you both talked about relating to her: you were similar ages, you had taken similar paths, in terms of going away from your home community to predominantly white institutions, and you felt like you had some similar experiences as Faith Hedgepeth. How did you feel when you heard about the arrest, especially given all of the possibilities that were out there about the suspect?

YEAH, I DON’T THINK THERE’S ANY INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY IN NORTH CAROLINA WHO DOESN’T KNOW FAITH’S NAME AT THIS POINT BECAUSE SHE DID HAVE SUCH AN IMPACT.

BH: I was actually taking a nap when I got the news. And I woke up and had thirty texts and all these notifications, so I think it’s a lot of different emotions. Who is this person? He was never named in any of the other information. It seems so random, almost. So, there’s also a lot of curiosity. How did this happen? But also a lot of relief and such happiness for her family to have one answer among hundreds of questions that they probably have on this case. There are so many different connections that I feel like I had with Faith without actually knowing her. This case has always felt really close to me in a lot of ways. I felt a whole mix of emotions when I found out.

CL: Yeah, I don’t think there’s any Indigenous community in North Carolina who doesn’t know Faith’s name at this point because she did have such an impact. Faith is the exception, she’s not the rule, because she did meet some of those standards. She was smart. She was very beautiful. She was off at a good school, not in her tribal community. In many other ways she was similar to Marcey: she was an Indigenous girl, grew up in her Indigenous community. But she was different in other ways. Marcey wasn’t an honor student heading to Chapel Hill and getting out of her community. So, I think being in Chapel Hill had a lot to do with it. I don’t know that we would see the same kind of coverage if it had happened in Hollister, in her tribal community.

BH: Then you even think about cases like Eve Carson, which I think is kind of similar to Faith’s case, which got even more national attention than Faith’s and which was solved rather quickly in comparison to Faith’s, which took nine years to solve.14 So, even though Faith’s case got much more attention

17 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina 13 The

One

episode 29, released 15 June 2021,

the

Season

finale,

featured

case of Faith Hedgepeth.

14 Eve Carson was a white female student at UNC Chapel Hill who was murdered in 2008.

ABOVE Brittany Hunt, during this interview

COURTESY OF BRITTANY HUNT AND CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

than most Indigenous women get, she still got less than most of the famous cases of white women being murdered get.

Regarding another case, the Casey Young episode, you talk about how the victim was a part of the LGBTQ community and the ways that LGBTQ people are more vulnerable to violence. You also talk about homophobia and its connection to evangelical Christianity in Robeson County. To what degree do you feel you need to educate your listeners about issues in Robeson County and Lumbee communities, in particular? Obviously, I’m talking about the context of this case, but you could speak to that more broadly.

BH: I was thinking about this question a lot. I think that there are some media that are created for non-Natives to tell them about what Natives are like, and then there’s some media that’s created for Native people by Native people, and Chelsea and I really strive to create something that feels like it’s for Indigenous people but still accessible to non-Natives, as well. We not only want to create a podcast where people can learn more about Lumbee people, and Indigenous people in general, where they can learn more about what our communities face, but also something that provides a space and a voice for Lumbee and Indigenous people and provides a media platform despite us having very little media coverage in general, especially media coverage that’s positive. But on the issue of homophobia in the Lumbee community, more generally, it’s important to think about the impacts of colonization into Indigenous communities. Prior to colonization, Indigenous communities were often very welcoming and accepting of LGBTQ tribal members, and there were protected spaces specifically for those members who were often regarded or respected even higher. Unfortunately, the introduction of colonization, with a particular type of Christianity that has infiltrated into Indigenous communities, has caused a level of homophobia that ends up creating situations like what happened to Casey Young and what happened on other episodes that we shared, as well. These impacts are disastrous, but I still think they’re important for us to talk about. And also, to help Lumbees confront these issues that are in our communities, it’s really our responsibility at this point.

WE NOT ONLY WANT TO CREATE A PODCAST WHERE PEOPLE CAN LEARN MORE ABOUT LUMBEE PEOPLE, AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLE IN GENERAL, WHERE THEY CAN LEARN MORE ABOUT WHAT OUR COMMUNITIES FACE, BUT ALSO SOMETHING THAT PROVIDES A SPACE AND A VOICE FOR LUMBEE AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLE.

I’m wondering what the future of The Red Justice Project looks like. Are you planning to revisit any cases, or do you mainly do that with folks via social media?

CL: I definitely think there are a couple of things that we would like to revisit, especially in the start of Season Two. One is kind of an extended chat around residential boarding schools, especially given the media that, again, hasn’t been quite the same wave of media that we saw

18 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

with Kamloops. But there have been a lot more bodies found, and we really, in just a thirty- to forty-minute episode did not get to touch on many of the issues that were caused by Indigenous boarding schools, such as loss of language, loss of culture, some of the experiments that were done on Indigenous children, such as malnourishment and its effects on students’ ability to learn. So literally they would starve kids to see if it would affect their ability to learn, which is, of course, if you don’t eat, you cannot concentrate. There are so many things in that episode alone that we didn’t get to touch on that I think we would love to bring back for Season Two. And, of course, with us ending with Faith’s episode, we’re hoping that there will be many more updates since someone has been arrested, so I could see us touching on that as well in Season Two.

What is your engagement like with your listeners? I follow you on social media, and I know you say, “Call us if you have a tip.” Do you get tips? Do you talk to folks just through social media? Are there other ways? When you go to Robeson County, do people pull you aside now and say, “Hey, I heard this thing”? What’s that like for you?

BH: We do get messages from people. We get theories. After the Casey Young episode, her cousin actually reached out to me and told me that it was the first time she felt like she could breathe in eleven years because the way we told the story kind of validated her own perspectives and her own memories of her cousin. There are times like that where it feels so right, what we’re doing, and so purposed.

I really enjoy those episodes when you’re talking to people that are in your family or people that you know, or they’re people that you just met, and they get really comfortable, and then there’s this guy who says, “Chelsea, let me tell you.” I thought, “That’s great. You developed this relationship that makes people really comfortable.”

CL: This was something that I think Brittany was touching on earlier: we might use a thirty-second clip of an interview, but literally we were on the phone with someone for two hours because when you’re talking, especially to people from your own community, you really build that rapport with these families. For them, it’s almost like a therapy session. Here’s someone who actually wants to listen to my story and hear what I have to say about my child, or my cousin, or my niece. And for a lot of family members, even though it’s really hard to talk about in some ways (and this is something Brittany says a lot), it’s kind of a form of justice for some of these families: just to be able to have their story put out there and to know that other people are listening. n

19 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

ABOVE Chelsea Locklear, during this interview

COURTESY OF BRITTANY HUNT AND CHELSEA LOCKLEAR

TAKING UP THE MANTLE AND MAKING IT HER OWN

a review by Lynne

Norris Murray

Shoulders:

Upon Her Shoulders: Southeastern Native Women Share Their Stories of Justice, Spirit, and Community, a collection of stories and poems that the editors term “contemplative reflections” (xxii), amplifies the voices of Native women, primarily from the Lumbee Tribe in North Carolina. These editors – Mary Ann Jacobs, Cherry Beasley, and Ulrike Wiethaus – view stories as empowering, weaving past and present together to preserve culture, to maintain community, and to determine how “shared knowledge . . . fits her own needs” (xvi). The book’s dedication to Rosa Winfree, Ruth Revels, and Barbara Locklear honors the elders who preserve a culture that colonialism tried to silence, while also tirelessly continuing a path towards social justice for the women who will come after them. The collection also captures new voices who embrace their collective past and use their knowledge to advance their futures.

The editors divide the book into three themes: community, spirit, and justice. Each editor introduces the theme and writers followed by the stories. Each part ends with “In Closing: Contemplating the Words of Wisdom by Our Women Elders,” a patchwork of voices from notes posted on the walls during conferences and workshops. A list of reflection questions and a short bio of each contributor aid the reader in delving deeper in the stories.

The title of Part I, “Make Yourself Useful, Child,” comes from Mary Ann Elliott’s early life lesson from her grandmother that

everyone, including children, is expected to contribute to the community. For women in this section, usefulness benefits beyond the immediate of day-to-day living, but also the community’s future well-being. Lumbee elder Ruth Revel surmises, “You do not have to do it all, but you can help others do more than you did” (15). Revels took on the challenge of helping others first through persevering discrimination to gain a teaching job. After hearing a racist comment from a fellow teacher, Revels chose to do more to address inequities in her community. Becoming the first executive director of the Guilford Native American Association and member of the North Carolina Mental Health Commission, she utilized her talents to address adult literacy that grew into Native Industries, which provided jobs and daycare to the chronically unemployed.

Learning to serve is a common thread that runs through the stories of teachers in this section, from Mary Alice Pinchbeck Teets using music to teach “self-respect, hard work and good ways of living” (32) to Cherokee Elder Marie Junaluska who translates English into Cherokee language that keeps the culture “thriving” (43). The impetus for learning is to preserve the community’s values and culture and to work toward social justice in the world beyond. Many women describe their purpose as spiritual; the path will be difficult at times, such as facing obstacles of racism and navigating their Native identity within mainstream

20 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

Mary Ann Jacobs, Cherry Maynor Beasley, Ulrike Wiethaus, Editors. Upon Her

Southeastern Native Women Share Their Stories of Justice, Spirit, and Community. Blair, 2022.

LYNNE NORRIS MURRAY is an English Instructor at High Point University and the Faculty Director of the Community Writing Center. She teaches first-year writing and a course in Southern Gothic literature.

MARY ANN JACOBS, chair of American Indian Studies at UNC Pembroke, teaches courses in American Indian identity, education, and culture. She is a member of the Lumbee Indian Tribe.

CHERRY MAYNOR BEASLEY, a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, chairs the Department of Nursing at UNC Pembroke. Her expertise includes minority and rural health.

ULRIKE WIETHAUS developed the religion and public engagement concentration in religious studies at Wake Forest University where she is Professor Emerita in the Department for the Study of Religions and the Department of American Ethnic Studies.

Read about RAVEN DIAL-STANLEY with her art featured in the preceding interview.

societal ones. Barbara Locklear prays that she “will live a good path” (46). From her perspective as an elder she writes, “I now see that what is truly important is not the things that I leave behind, but the path that I make for others to follow” (47). The path is not designed for others to follow lockstep in her footsteps, but to continue making one’s own. Cherokee Madison York, an aspiring medical doctor, stands at the beginning of her own path in her poem, “My Questions for Creator”: “I want to help / but I am not sure I can walk both paths.” York feels the obligation to honor her ancestors and that of her healing call, which requires her to follow the society’s course. She seeks guidance from her Creator to “span . . . the two walks” (11).

Spirituality is explored more fully in Part 2, “Spirit Medicine,” which shares its title with Kim Previa’s essay. In her work as a life coach, Previa embraces the spiritual in her approach called “eyes of my heart” (67). Seeing through the eyes of the heart

allows one to connect with another in a genuine way that disperses loneliness and fear. Previa concludes with “As we trust the divine, then things can change and shift because we are free to be ourselves” (70). The women in this section share how reliance on the spiritual gave them strength to persevere through traumatic experiences and find the freedom Previa describes.

Spiritual entities Clan Mother and Three Sisters respectively provide guidance to Daphine Strickland and Charlene Hunt. In Iroquois culture, the Clan Mother is honored for her wisdom and power. Responsible for the well-being of the tribe, she advises the Chief and oversees ceremonies. The Three Sisters provide sustenance for the tribes. Represented as corn, beans, and squash, they demonstrate the interconnectedness of the community. Corn provides the stalk for the beans to climb, and squash’s shade preserves the moisture for growth.

Strickland assumes the identity of Yellowbird in sharing her suffering from raising a violent child at her mother’s request, grieving her sister’s untimely death, and caring for her mother after a debilitating stroke. Yellowbird relies on the Clan Mother within, who guides her decisions, until she ultimately sees the Clan Mother in herself. For Charlene Hunt, the Three Sisters represent “a deep spiritual connection not only with the Earth, but also with our souls” (90). Caring for her ailing father, she understands the cyclical nature of life. As her father loses strength, she gains strength by becoming corn, “helping to hold my father up” (92).

Gayle Simmons Cushing’s poem “Patchwork Images” opens Part III, “Getting Justice When There Was None,” and provides part of the book’s title. The last stanza likens women’s roles to a patchwork quilt: “The responsibility of being Native woman was placed upon / Her shoulders at birth, / Blanketed –like a patchwork quilt – around her body” (106). Less of a burden and more like a comfort, a patchwork quilt suggests different patterns, colors, and fabrics that represent individual women’s contributions to the whole community. The stories in this section relate what Jacobs describes as “Indigenous restorative justice designed to bring peace and balance to the community” (97–98). An excerpt from Ruth Dial Woods’s dissertation documents her experience at the Alcatraz Occupation in 1969–70, a protest designed to create an autonomous cultural center on Alcatraz in accordance with the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Kay Oxendine, who as a child was told in history class that “all Indians were dead” (136), dismisses erasure through her writing, radio shows, and Native organizations. Non-violent protests, educating others, amplifying Native voices are the means by which women in this collection seek justice for their communities.

Each woman featured in this volume takes up the metaphorical mantle and adds her unique contribution to the fabric design, providing vibrant images of proud, thriving Native cultures. Olivia Brown poses in her poem, “Native American”: “We are still here, / Hidden by our education and modernisms. / Do you see us?” (56). Yes. Yes, we do. n

21 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

Young Healer, 2020 (virtual drawing, 8.5x11) by Raven Dial-Stanley

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

BY MARY LEAUNA CHRISTENSEN

In Which I Am a Sum of Parts

2 corn seed necklaces hang on the back of my door

along with 2 medicine bags made of tiny glass seed beads

sterling silver & turquoise bolo ties

(nothing crafted by my own hands)

* Another lesson

my ancestors hid in mountain caves & confederate uniforms

my many-greats grandfather was given the English name Nimrod

b/c aren’t we all mighty hunters

& it is likely my blood is altered or diluted somewhere in Oklahoma

b/c not all ancestors were so lucky

(if that is the term we’re using & the fact cannot be ignored –

I am diluted down to the card in my wallet which states my blood as a percentage) *

While I was cleaning my grandmother’s house I found a box of tears

I was barely a teenager the first time I remember visiting the reservation my grandmother left decades prior

her brother & brother’s wife tried to educate me

*

commented on my lack –

how that was the first time I tried & gave up beading –

disillusioned when the belt I made broke *

My first lesson was corn seeds their grey hard form imperfectly round how they were solid manifestations of every Cherokee tear rained along the trail

*

22 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

This poem previously appeared in Southern Humanities Review

MARY LEAUNA CHRISTENSEN , an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, was an undergraduate at Western Carolina University and is now a PhD student at the University of Southern Mississippi, where she is Managing Editor of The Swamp literary magazine. Her work can be found in New Ohio Review, Puerto del Sol, Cream City Review, Laurel Review, Southern Humanities Review, and Denver Quarterly. She was also named an Indigenous Nations Poets fellow for the inaugural In-Na-Po retreat.

The scientific name for corn seed is many syllables but here we’ll call it Cherokee Tear

it is easy to string onto necklaces but should not be confused with seed beads which come in varying degrees of tiny plastic & glass *

The last time I was on the rez it was not for an introduction but a burial

& I bought beads in colors I found comforting

along with needles

thin strips of leather

waxy manmade sinew *

Tears do not equate mourning but I take the pad of my finger press against a duct & hope to find some hard blockage induce a kind of birth

Cherokee, NC, native JODY BRADLEY, a poet, writer, and artist, is a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. She earned a BS in Education at Western Carolina University. Since retiring in 2015 from careers in the fields of education, medical, and public relations, she has turned her attention to her art, which has earned frequent invitations for talks and exhibitions in such venues as CarsonNewman University’s Appalachian Cultural Center, Asheville Art Museum, and Heywood County Arts Council. Bradley owns and operates Legend Weavers Studios in Cherokee, NC, and she still lives on the Cherokee Indian Reservation. See more of her art in the 2023 print issue.

23 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

Just As I Am II (acrylic with copper, 8 in. round) by Jody Bradley

RE-MEMBERING THE DARK AND THE LIGHT

a review by Jennifer Peedin

Kimberly Becker’s new volume of poems, Bringing Back the Fire, is a collection of darkness and light, of grief and relief, and is in part a personal journey. On a much wider scale, it is a journey that reflects the exploration that is ongoing in North Carolina and in the South at large as we remember and learn about our Indigenous history. While Becker “re-members,” so do we; as Becker calls home over and over again, so do we, wherever that may be. In the title poem, told from the perspective of the water spider that brought the fire to the world in the Cherokee legend, she writes, “I dream dreams of fire and water / And when it thunders I think of the hollow in the sycamore tree on that / island that once seemed impossible to reach.” This story, like Becker, seems to be calling for a re-memberance and a redefinition of what it means to be from the South, what we hope the South will one day become, though at times it seems impossible to reach.

doing so, Becker divides the collection into two sections, Dark and Light, the former beginning the volume. The Dark section opens with “Affixing the Halo,” her own story of the process of getting a Halo brace before stereotactic brain surgery, but readers find bits of themselves as she describes the painful process: “The halo is heavy as hell / It becomes hard to hold your head up / with the weight / of this unwieldy glory.” We remember the burdens of smiling when angry, holding our heads up when we want to collapse in exhaustion, and Becker embraces those thoughts, too, writing, “Buck up; hold your head high? / But the halo is heavy; you can barely walk / No way you could fly.” She offers permission to let the halo fall and drop our head into the absolute chaos of modern life.

JENNIFER PEEDIN grew up in Eastern North Carolina and is currently a PhD candidate at West Virginia University where she researches southeastern Indigenous and Black narratives that rely on swamps and hurricanes.

KIMBERLY L. BECKER is author of several poetry collections, including Words Facing East (WordTech Editions, 2016), Flight (MadHat Press, 2018) The Bed Book (Spuyten Duyvil, 2020). Her poems have appeared in journals and anthologies, including Women Write Resistance: Poets Resist Gender Violence (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2013); Indigenous Message on Water (Indigenous World Forum on Water and Peace, 2014); and Tending the Fire: Native Voices and Portraits (University of New Mexico Press, 2017).

Becker is assiduous in communicating with the past, memory, and grief, both her own grief and others. Her new poems are frank in their raw emotion and unromantic in the best way possible. Those of us who tire of a romanticized version of the dark places in life and the journey to circumvent them find relief in Becker’s poems. They easily allow us to see ourselves in these situations, in that arduous journey of trying to bring back the fire. In

Other poems reflect Becker’s preoccupation with memory and home. She often writes “re-member,” stressing the reconnection and recollection of the past rather than a simple remembering of what is forgotten. This may be evidence of Becker’s continued explorative journey into her Cherokee heritage with her consistent use of the Cherokee language, seeing and connecting with her ancestors in everyday life and retelling Cherokee stories and legends such as the title poem, “Bringing Back the Fire.” This process of exploration and identifying as a poet of Cherokee descent is present in her other volumes,

24 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

Kimberly L. Becker. Bringing Back the Fire. Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, 2022.

but in this collection, Becker allows readers to engage with the Cherokee past and how it bleeds into a present-day North Carolina, reminding us of a long ago home. It is natural to think of the past, of home, in the midst of grief or struggle, and in her poem “Heimweh” (German for homesickness), Becker writes, “I am far from / mound and mountain / . . . / but I will face East to sing / my morning song in Cherokee.” Many of us, in the waning days of a pandemic, often look homewards or to a past with more comfort in the known, and though Becker acknowledges this anxious nostalgia, she is also very quick to share that she is not alone in her

journey through the present.

Spirits are scattered throughout the collection, spirits that watch and council and those that have chosen Becker to share their story. They are “Knocking from within barn walls / Spirits saying / we, too, lived with unmet needs / we, too, need attention,” and they come to the surface in a trip to New Echota, the beginning of the Cherokee Trail of Tears, as Becker is overcome with emotion narrating, “from this place of strength and grief, / offering thanks / My tears are for self, but also from deeper source.” In the journey to bring back the fire, Becker reminds us of a time of deep darkness, employing these spirits to narrate in “Missio Mei,” a poem about Native boarding schools. She writes “of a religion that forced baptism / onto heathens / forced innocence / from children.” Though reflecting a dark time in American history, many in the Indigenous community are now active in ensuring the future is different. Becker writes, “This is what happens / when you give away your power / Now my mission is to call it back.”

Offering these words of power and action, Becker calls us into the Light section of her collection. As promised, she brings us through the grief to the other side, a lighter side, made wiser from trauma.

In Bringing Back the Fire, Kimberly Becker’s poems bring life back to a comatose world, to awaken what was forgotten, but she must take us through the fire to get there. Becker takes us back to the lows of the past few years as she describes hospital rooms, COVID chaos in the ER, and the undignified state of death. Her words serve as a reminder that there must be darkness, sometimes significant darkness, before there can be light. When she does return us to the light, brings us back to the fire, we know we’ve conquered the darkness. n

25 N C L R ONLINE Native American Literature of North Carolina

Read about Cherokee artist JODY BRADLEY with the poem that precedes this review.

COURTESY OF

ABOVE TOP Just As I Am (acrylic paint on canvas, 8x10) AND BOTTOM Some Day (acrylic paint on canvas, 8x10) by Jody Bradley (Cherokee Syllabary behind the figures, respectively, “Just as I Am” and “Amazing Grace”)

THE ARTIST COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

Increasing Echoes

by Margaret D. Bauer, Editor

After three decades of feature sections and writers, it is no surprise that our Flashbacks section gets longer and longer. Welcome back to several writers, whether for yet another poem or essay that was a finalist, for having a new book reviewed, or for receiving a new award covered here (looking at you, 2022 Raleigh Award winner, Valerie Nieman). Given our 2006 issue’s focus on children’s and YA literature, we always publish the news of the latest recipient of the NC AAUW Young People’s Literature Award in this section. Congratulations to Micki Bare. Too often, this section includes notice of the passing of one of NCLR’s writers. This time it is my mentor and friend Philip Gerard, who has been a source of support and kindness since I met him in my early years as Editor. During Alex Albright’s editorship in NCLR’s first years, Philip shared a chapter from his provocative novel Cape Fear Rising, a novel that would bring much needed attention to one of the darkest chapters of North Carolina history, the 1898 coup d’etat in Wilmington. I learned about the only successful coup d’etat in American history via this issue of NCLR, sent to me prior to my interview for the job as NCLR Editor. And I remember that I could not wait to read the full novel. Since doing so, I have taught Cape Fear Rising several times, including in an honors seminar on the coup in literature and history, during which my colleague History Professor Karin Zipf and I brought our class to Wilmington. Observing his engagement with our students, as well as at readings and other literary events, I got to see Philip in action, and I know his students are mourning the loss of such a generous, enthusiastic professor. I share their grief, and repeat my condolences to his wife, Jill, and his colleagues at UNC Wilmington. Read more about Philip in our remembrance here.

In 2001, our science fiction feature included an interview with John Kessel, and we published a short story by him in 2006. More recently, Dale Bailey got a little carried away – in a good way – in his effort to review Kessel’s new collection of short fiction. “Keep going,” I said, when he warned me that the review was exceeding our usual thousandword range. I know you’ll enjoy Dale’s essay as much as I did. Now I’m looking forward to reading more of Kessel’s fiction, though I’m still deciding about whether to read the one that “took the top of [Dale’s] head off (not gently) and gave the contents inside a thorough stirring.” But how can I resist after Dale’s description of the effect of that story every time he reads it?.

If you are a writer we have not previously published and are therefore wondering how your essay or poem ended up in this section, it’s something about your work’s focus, which echoes a past issue’s feature section. Our 2011 issue featured environmental writing, and the environment plays an important role in Mark Powell’s novel reviewed in this section. In 2014, we featured war in North Carolina Literature, and here you’ll read a review of a new World War II–era novel by Leah Weiss, who is new to our pages. Our 2017 topic, North Carolina Literature and the Other Arts, brings Morrow Dowdle’s poem “Brow,” inspired by artist Frida Kahlo, and Blaise Kielar’s music-inspired essay into this section.

Enjoy, too, reading about the newest members of the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame in the pages to follow. And as North Carolina Writers’ Director Ed Southern directed the audience at the induction ceremony, “keep reading.” n

26 NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY REVIEW Winter 2023

28 Celebrating, Finally, the 2020 North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame Inductees

34 A Triumph from Doodle Hill

a review by Rebecca Godwin

n Malaika King Albrecht and Marsha White Warren, eds. Collected Poems of Marty Silverthorne

36 “We’ve all lost a champion”: Philip Gerard (1955–2022)

38 A Very Dark Ride: Three Ways of Looking at the Short Fiction of John Kessel

a review essay by Dale Bailey

46 Cosmic Background Radiation

a poem by Eric Weil

art by Robert Langford

48 The Coming of Wisdom in WWII Eastern North Carolina

a review by Donna A. Gessell

n Leah Weiss, All the Little Hopes

50 NC AAUW Young People’s Literature Award

51 Making Sense of the Sixties

a review by Sheryl Cornett

n Lee Zacharias, What a Wonderful World This Could Be

53 Valerie Nieman Receives Sir Walter Raleigh Award

54 Captain von Trapp in the Surgical Suite

a poem by Maureen Sherbondy

art by Tim Lytvinenko

55 Jubilee

a poem by Janet Ford

art by Carrie Tomberlin

56 Complicated Connections: Young Love in the 1970s South

a review by David Deutsch

n Jim Grimsley, A Dove in the Belly

FLASHBACKS:

Echoes of Past Issues

58 Vocation and Dead Sea Pantoum

two poems by Janis Harrington

art by Horace Farlowe

60 Raised by Hand and Story

an essay and poem by Glenis Redmond

66 Heading West

a poem by Debra Kaufman

art by Ralston Fox Smith

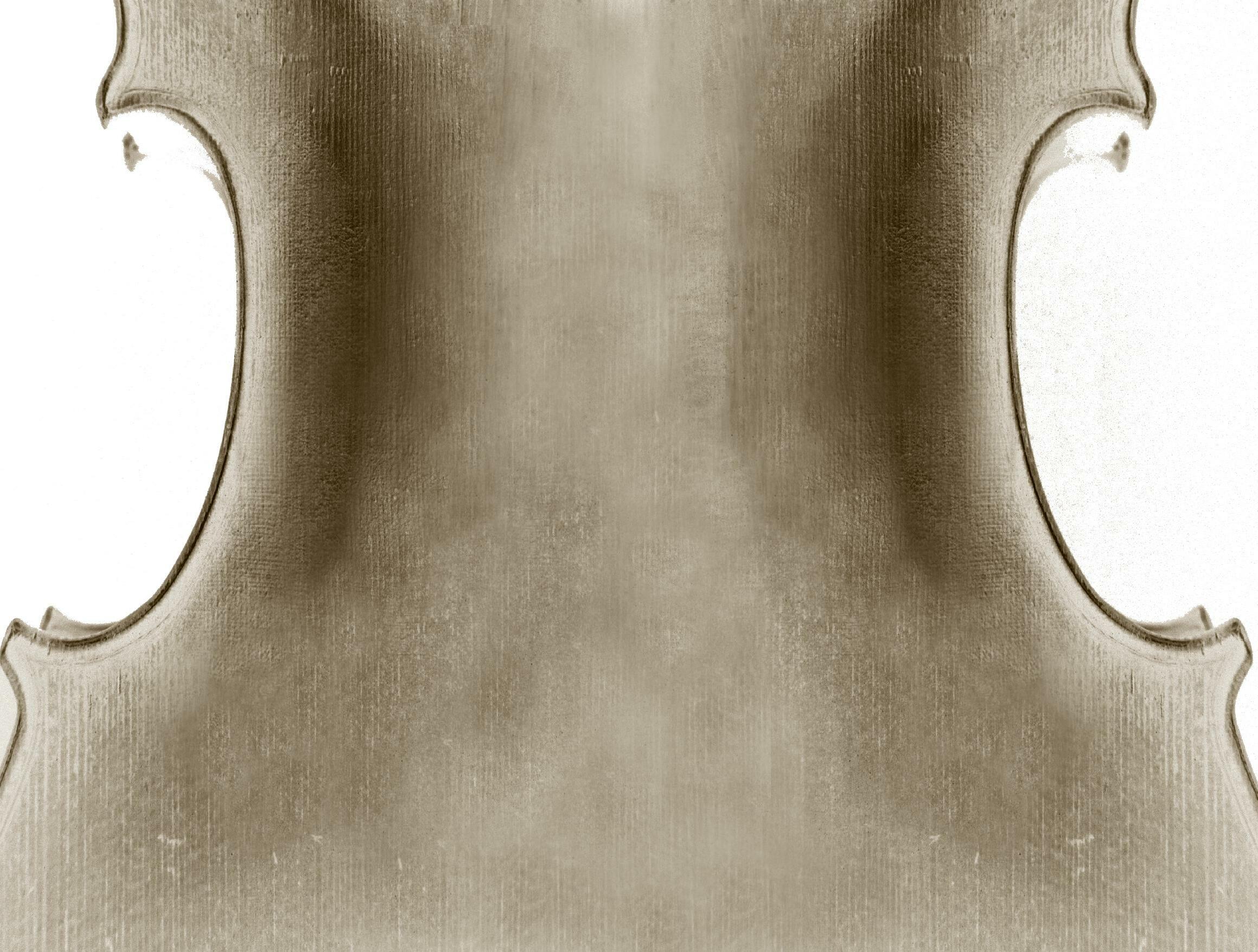

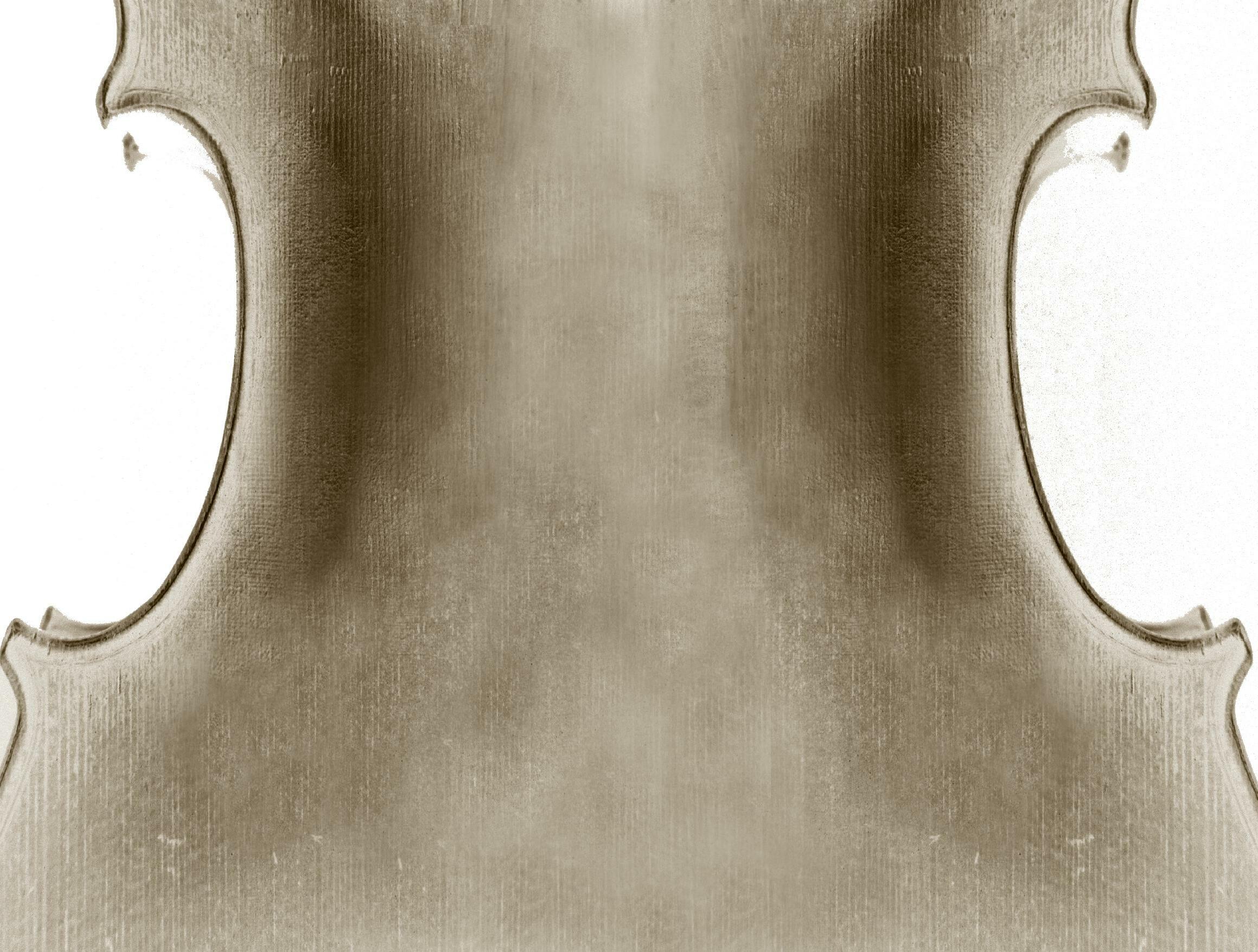

68 Violin Shop: Behind the Velvet Counter

an essay by Blaise Kielar

77 “All come to look for America”

a review by Jim Clark

n Joseph Bathanti and David Potorti, eds.

Crossing the Rift: North Carolina Poets on 9/11 and Its Aftermath

80 Brow

a poem by Morrow Dowdle

art by Peter Marin

82 An Examined Life Through the Lens of Artistic Vision

a review by Heather Bell Adams

n Luke Whisnant, The Connor Project

84 Daylight Savings

a poem by Bill Griffin

art by Chris Liberti

86 “idealist with the big broken heart”

a review by Barbara Bennett

n Mark Powell, Lioness

88 Patient Doe Escapes the Asylum and Goes on the Town

a poem by J.S. Absher

art by Theodorus Stamos

90 “the human heart in conflict with itself”

a review by Patti Frye Meredith

n Erica Plouffe Lazure, Proof of Me & Other Stories

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

6 n Native American Literature of North Carolina an interview, poem, and book reviews

92 n North Carolina Miscellany poetry, prose, and book reviews

27 N C L R ONLINE

CELEBRATING, FINALLY, THE 2020

NORTH CAROLINA LITERARY

The induction ceremony for the 2020 inductees into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame was worth the wait for a safer time to gather to celebrate. October 16, 2022 was warm and clear in Southern Pines, NC, and the crowd sitting under the tent behind the Weymouth Center were in for a treat. The crowd enjoyed stirring speeches as Anthony Abbott and Max Steele were inducted posthumously. Two former North Carolina Poets Laureate spoke about and read from Abbott’s work. Steele was lauded by UNC Chapel Hill’s Director of the Creative Writing program, a position Steele held for twenty years. Carole Boston Weatherford was inducted in absentia by a writer influenced by her and then her work read by her son and daughter-in-law. Family members also inducted Charles Frazier (his daughter, also a writer) and Bland Simpson (his wife and collaborator).

“revered, inspirational, life-changing teacher”

Anthony Abbott

induction remarks by Joseph

Bathanti

Anthony S. Abbott graduated from Princeton, then Harvard, where he received his PhD, and, in 1964, joined the faculty at Davidson College. He was named Charles A. Dana Professor of English in 1990 and served as Department Chair from 1989 to 1996. Recipient of Davidson’s Thomas Jefferson Award and the Hunter-Hamilton Love of Teaching Award, a revered, inspirational, life-changing teacher, he has launched scores of writers and scholars. I do not exaggerate when I say Tony Abbott remains a legend beloved at Davidson College and in the town of Davidson.