6 minute read

mr

He raised that another notch in 1976,

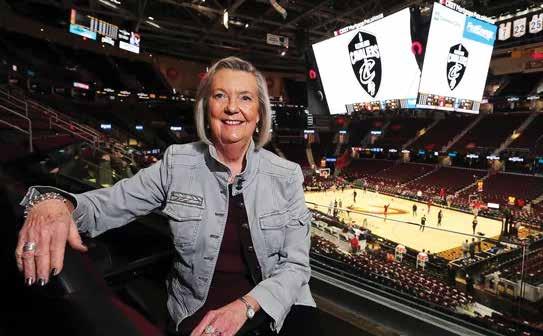

Because I was the first woman to cover the Cleveland Browns in 1981, some consider me a trailblazer for women in sports journalism. But it was Kidd who opened the holes and eliminated the early

That’s why Kidd’s portrait remains untouchable on my office wall, along with his place in

At the beginning of the 2000 football season, as Coach Roy Kidd was inching closer to his 300th victory, I knew that moment would be the one photo that would define my career as Eastern’s university photographer. I could sense that it would be the one image that would still matter a hundred years from now. I just had to make sure I was there when it happened.

Chasing

by Tim Webb

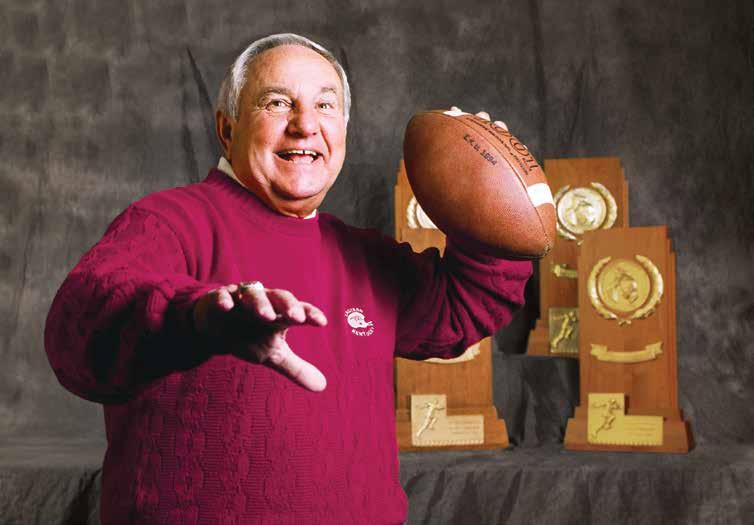

Leading up to 300, I did several photos with Coach because I knew the university and media outlets would be in need of images. One of my all-time favorites came from a portrait shoot with Coach and the four consecutive trophies that came from Eastern’s four consecutive national championship appearances 1979-82. We were casually talking about his time as quarterback at Corbin High School and Eastern, when, out of the blue, he picked up a football and donned a left-handed quarterback pose with a big smile on his face. For a coach so meticulous in his planning, it was such an impromptu moment.

During my time as a student at Eastern, players like Lorenzo Fields, Elroy Harris and Tim Lester were lighting up the record books. Counting my days as photo editor of The Eastern Progress, I covered Coach Kidd and the Colonels starting in 1991. That year, I photographed the Colonels’ playoff run, which included a 14-3 win over Appalachian State on a rainy, muddy Thanksgiving weekend in Richmond, followed by a heartbreaking 14-7 loss in the semifinals to Marshall in Huntington.

With the 2000 season drawing to a close and Coach sitting on 299, I made the long trip to Charleston, Illinois, as the Colonels took on Eastern Illinois and future NFL quarterback and broadcaster Tony Romo. Eastern’s season came to an end that Saturday afternoon and, with it, the quest for 300 would have to wait another year. As I drove back to Richmond, I couldn’t help but think that, surely, they would schedule a home game to open up the 2001 season so that Coach could get his milestone win at home.

Nope. Chasing 300 wouldn’t be that easy. For me, the 2001 season kicked off with an even longer drive to Mount Pleasant, Michigan, to photograph the Colonels against the Division I Chippewas of Central Michigan University. While the Colonels took a lead into halftime, we left Mount Pleasant still one win short.

I knew that Coach’s chances would improve the following Saturday, when we were set to host Liberty University in the stadium that bore his name. As expected, on a beautiful Saturday evening, September 8, 2001, the Colonels whipped

Liberty 30-7 to give Coach Roy Kidd his 300th career victory, solidifying his place among the greatest college football coaches in the history of the game. As the sun fell and with the clock winding down, his players doused him with Gatorade, hoisted him on their shoulders and carried him out onto the field.

For a few seconds, I froze and didn’t know what to do because the clock was still running with about 30 seconds, and the game was still in progress. I thought, “You can’t do that. You can’t do that. The game is still going on!” All I could think about was how I had driven so many miles and spent so many hours chasing 300. And now, here it was unfolding in my back yard, and I was about to miss it because I didn’t want to be a rule breaker.

Not to be denied, I ran out onto the field and cut into the middle of the huddle as it was still moving. I popped up in front of Coach Kidd and was able to fire off two frames before stumbling backward. I couldn’t be sure I got the “money shot” until the following Monday morning, when I picked up the film from a local lab. My heart sank when I looked at the first frame because one of the players who was holding coach’s leg was looking directly at me with his tongue stuck out. Thankfully, by the second frame, he had looked away and put his tongue back in his mouth — that was the image that will go down in EKU history.

The celebration on the field that night was unlike anything I had ever experienced. You could tell there was a sense of relief with Coach Kidd because a weight had been resting on his shoulders for several months. You could see the sense of accomplishment on his face, along with a big smile, as he and Sue embraced on the field. It was as if everything they had worked for all those years culminated that night. And while Coach was celebrating with his family, the students were busy tearing down the goal posts. It warmed my heart to watch as they carried one of posts off of the field like an army of ants and down Kit Carson Drive to its final resting place at Madison Garden downtown.

Colonel fans climb a home-field goal post to celebrate Coach Kidd’s historic 300th victory.

It dawned on me that night as I was packing up my gear to go home that Coach Kidd was never meant to win number 300 on the road. The opposing fans wouldn’t have appreciated it the way we did. It was only fitting that number 300 was won at Roy Kidd Stadium in Richmond, making that rendition of “Cabin on the Hill” extra special.

Chasing 300 and having the opportunity to record part of Coach Roy Kidd’s legacy was an experience I’ll

IT WAS ONLY FITTING THAT NUMBER 3OO WAS WON AT ROY KIDD STADIUM IN RICHMOND, MAKING THAT RENDITION OF “CABIN ON THE HILL” EXTRA SPECIAL.

by Dr. Charles Douglas Whitlock (EKU President Emeritus)

I first met Roy Kidd in the fall semester of 1957. He was my freshman general science teacher at Madison High School in Richmond. He was in his second year as the football coach of the Madison-Model Royal Purples, which built into a dynasty of sorts. A decade later, he would be well on his way to the same sort of success at EKU.

Randall Fields, editor of the Richmond Daily Register, was looking for someone to cover Madison-Model athletics and asked my English teacher for recommendations. That’s what got me into sports reporting. Eventually, I was also stringing for newspapers in Louisville and Lexington.

In a story I did for the Lexington Herald in advance of a big Central Kentucky Conference game, I wrote something to this effect: “Two of the Royal Purple trademarks are a stunting defense and counter trap running plays.” After this appeared in the morning paper, Coach Kidd sought me out in study hall. His words, still etched in my memory, were, “Doug, I did not appreciate that scouting report in the newspaper, and if we lose, your butt is mine.” He may not have said “butt.”

I graduated from high school in 1961, and it was the last combined Madison-Model graduating class. It seems that other schools in Central Kentucky had complained that it was unfair for two schools to combine their student bodies for athletic teams. Considering there were only 57 seniors in my class, these other schools were chafing from being outcoached.

Incidentally, Jack Ison and Bobby Harville, who later joined Coach Kidd at Eastern, were on his MadisonModel staff.

Coach Kidd and I were reunited in 1963 when he came to Eastern as an assistant on Coach Glenn Presnell’s staff. He had left Richmond in 1962 and spent a year as an assistant coach at Morehead State. A year later, in 1964, he was named head coach and what would become “A Matter of Pride” was begun.

Our relationship was very much like it was in high school. I was a student assistant in Vice President Donald Feltner’s Office of Public Affairs, and under his tutelage I was doing sports information work and once again covering a Roy Kiddcoached team, both home and away. It was during the 1964 and 1965 seasons that my appreciation for him as a coach and person really grew. I have never been around anyone with higher expectations for himself and those around him. And these high expectations were not limited to the football field. He demanded politeness and courtesy. On more than one occasion, I heard him tell players –– often stars –– to take off a cap or hat indoors.

During our long careers at EKU, Roy and I had a lot of contact and became good friends. He retired one year before my first retirement in 2003. In 2007, when I came out of retirement to become president, he was working part time in development, helping our fundraising efforts. It did my heart good to see so many of his former players show their respect and love for the man at alumni meetings around the country. No one embodies what I call the Essential Eastern more than