6 minute read

The Liberator

from Salute to Veterans

by Echo Press

THELiberator

Alexandria developer was a World War II hero

By Karen Tolkkinen

Staff Sgt. Leander Hens, a farm boy from Belgrade, Minnesota, had no way of knowing what lay in store for him and his men that on that wet, cold morning in 1945.

As members of the Army’s 11th Armored Division, they were assigned to check all the roads, bridges and enemy soldiers in the area so that an American force could liberate an Austrian city from Nazi forces.

But Hens and his patrol stumbled onto a series of Nazirun concentration camps, that one Army major described in a book as “emanating wretched human misery and rank with the stench of death.”

The main camp was called Mauthausen, and among its

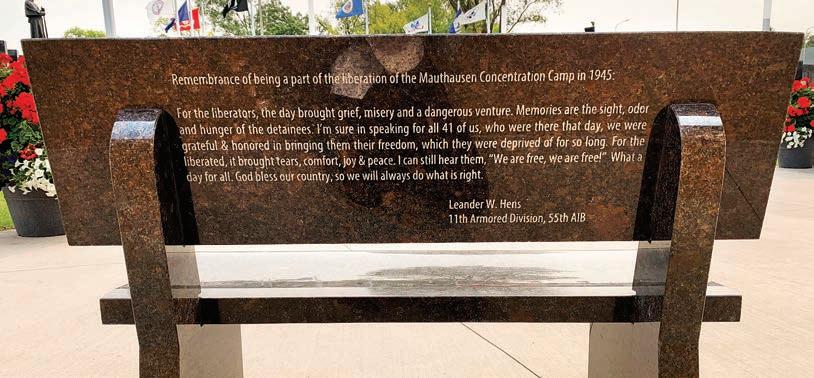

For the liberated, it brought tears, comfort, joy and peace. I can still hear them, ‘We are free. We are free.’

LEANDER HENS Staff Sargeant and WWII hero

100 or so subcamps were three particularly barbarous camps called Gusen I, II and III, where prisoners were worked to death in a rock quarry and in underground factories.

German SS officers had just fled, leaving Austrian troops in charge of gas chambers, piles of bodies and thousands of starving, brutalized people of many nationalities and political persuasions—Gypsies, Poles, Spaniards, Jews, intellectuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses

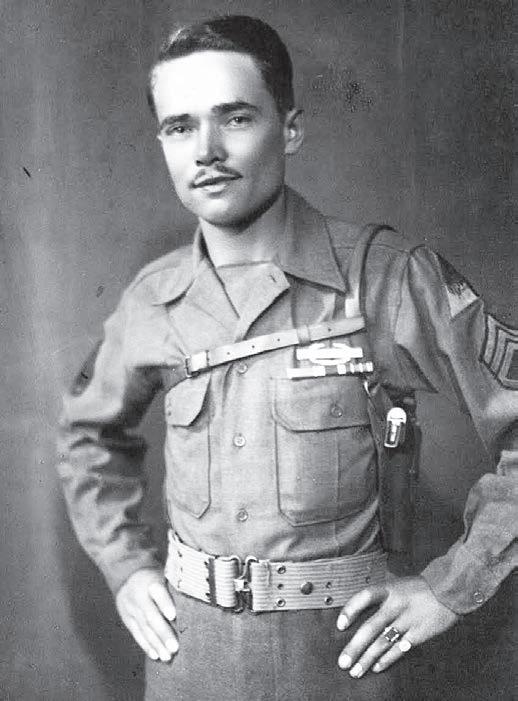

Leander Hens served in Europe during World War II. He was 22 when his patrol liberated several Nazi concentration camps in Austria. (Contributed) and criminals, according to Hens’ patrol was one of the books “Spaniards in the two that came across the Holocaust,” and “St. Georgen camps that day. They liberGusen Mauthausen,” each of ated the prisoners and left, which mentions Hens. Esti- lacking the food, medical supmates of those who died plies and numbers to care for during the seven years of them. In the following days, Mauthausen’s existence at American doctors and nursanywhere from 122,000 to es arrived. Still, hundreds of more than 300,000. former inmates continued to die every day from the trauma they endured. Hens died in 2003. However, his words describing that morning are inscribed on the back of a granite bench at Alexandria’s Veterans Memorial park. “For the liberators, the day brought grief, misery and a dangerous venture. “Memories are the sight, odor and hunger of the detainees. “I’m sure, in speaking for all 41 of us, who were there that day, we were grateful

The inscription on this bench came from Leander Hens’s note in a flyleaf in a book about the camp that quoted him, and which he gave to grandson Randy Roers.

Hens

Page 11

HENS From page 10

and honored in bringing them their freedom, which they were deprived of for so long.

“For the liberated, it brought tears, comfort, joy and peace. I can still hear them, ‘We are free. We are free.’

“What a day for all. God bless our country, so we will always do what is right.”

After the war, Hens married and settled in Alexandria. He had suffered two major wounds during the war and received two Purple Hearts plus a Bronze Star, and a doctor had told him he would likely not live past age 40, said grandson Randy Roers.

The doctor’s warning motivated Hens. He started a contracting business and developed the Midway Mall. He owned the Corner Bar downtown and the Algon Ballroom, where the movie theater is now. He slept only three or four hours a night.

“If you knew my grandpa, he never stopped moving,” Randy said. “Everything was urgent. It had to be done now. If you’re told 40 is your expiration date, you’re kind of double timing it.”

Hens actually lived to be 80, and in his later years, he began talking about his wartime experiences.

“When my wife and I got married, he didn’t talk about it,” said Hens’ son-in-law, Roger Roers, who is Randy’s father. “As Lee got older, I remember him talking about it constantly: ‘These stories need to be told or they’re going to be lost.’ He really wanted his stories to be known.”

Hens told his son-in-law about seeing three skinny people still alive in a one-person bunk at Gusen, and how he had to carry one because he was too weak to stand.

He also told them about the injuries that earned him the Purple Hearts. One occurred when he was going houseto-house in a village, looking for Germans. When he entered one house, someone leaped on him and jabbed a knife down his throat. Bleeding, he fought back and crashed through the window to escape.

Another injury occurred when he went looking for his friend Larry, whose sister Hens would eventually marry. Larry had been lost in woods where a battle had taken place. While looking for Larry, Hens fell into a foxhole occupied by a German soldier. He killed the German, but another German soldier hit him in the head with his rifle so hard that he blacked out and was found later wandering by American troops, covered in blood that was not all his own. The first he remembered was waking up in the medic tent. His head injury was so severe, he had to have a plate in his head.

After the war ended, Hens remained in Europe for a year. He spoke fluent German, and he went undercover for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services — the precursor to the CIA — to find SS officers who were in hiding.

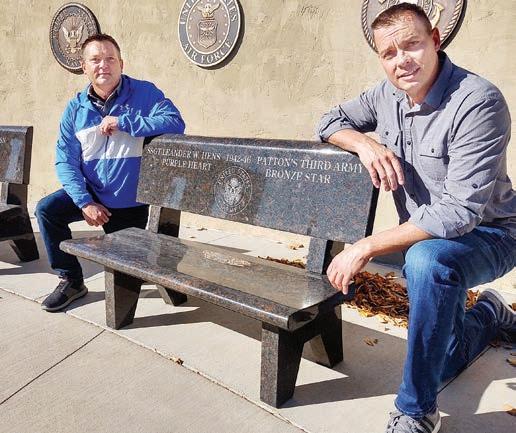

The intelligence agents would tell him the location of a suspected SS officer, and Hens would get work alongside the person to see if he could spot a telltale tattoo Cousins Scott Kluver, left, and Randy Roers with the bench dedicated to their grandfather, Leander Hens, at the Veterans Memorial Park in Alexandria.

As Lee got older, I remember him talking about it constantly: ‘These stories need to be told or they’re going to be lost.’

ROGER ROERS

LEANDER HENS’ SON

under the man’s arm. Twice, he fooled men into raising their arms, once while taking a swim on a hot day and once while washing off after working on a farm, and saw the tattoo. After he identified the men, said grandson Scott Kluver, his job was done.

“He got the hell out of there.”

Randy started accompanying his grandfather to Army reunions when he was 22.

“I was very interested in the history of it, and the history of World War II and his history,” Randy said. “To be able to talk to a living history book, who had a connection to you.”

Hens took two trips back to Austria, one in 1995 for the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the camps, and one in 2000 for another celebration. Several family members went with him in 2000.

The liberators were greeted with intense gratitude by survivors and their children.

“We saw one woman kiss his feet,” Randy said. “Well, his shoes, I guess.”

With their grandfather gone, it has fallen to his grandsons, now in their 40s, to tell his stories. They have pictures and war booty to prove it, including a large scarlet Nazi flag with a swastika that their grandfather pulled off a water tower while bullets were flying at him.

“We were lucky he talked about it,” Randy said.

About 300,000 World War II veterans remain alive in the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center, citing a federal report.

FLAG ETIQUETTE

Proper flag etiquette requires a person to only fly the flag between sunrise and sunset unless it is illuminated properly. The flag should be taken down in inclement weather, unless it’s an all-weather flag. Flags should only be flown if they are in good condition.