6 minute read

After the Bell

AFTER THE BELL

Advertisement

LEADING SCHOOL CHANGE THROUGH RESIDENTIAL LIFE AND EXTRA-CURRICULAR ACTIVITIES

DARYL HITCHCOCK TOK Department Chair Leysin American School

Our education system was designed to meet a need for a workforce capable of learning and implementing a standard set of skills. Though there have been adaptations, we are all too familiar with rows of students taking instructions from a single teacher in order to pass a standardised test. Order is maximised and deviation is identified and rectified.

Schools may need to identify the appropriate levers to pick up their rate of change. In a workshop at the beginning of the school year, educators were asked to identify the skills students need to navigate the modern landscape and workplace. Soft skills like resilience, flexibility, creativity, and the ability to embrace continually emerging and evolving competencies were all put forward. Nary a mention was made of content mastery, standardised tests, or the Common Core.

RESISTANCE IS DEEPLY EMBEDDED

That our educational system is in need of an overhaul shouldn’t be news to anyone. What can be much more difficult is making it happen. Change is hard, and real, substantive change in schools has been particularly

difficult to achieve. Will Richardson and Bruce Dixon (2017) remind us that “truly transformative change … in pre-existing schools is very difficult to find. It’s easier to build a new school than to change an old one” (page 2). School practices calcify and too often petrify.

We know that teaching soft skills, e.g. collaboration, perseverance, leadership, and respect, is important. We also know that course content crowds out soft skills. That doesn’t negate the need for them. And the problem is, even when some parts of the educational equation are ready to embrace change, there are plenty more forces ready to defend the focus on content.

Parents demand it (I want my kid to get into such-and-such university), teachers are trained in it (it’s easy to hire a history teacher, it’s harder to find a perseverance teacher), government programmes require it (no more needs to be said), materials, books, nearly everything is provided for content. And here is the kicker: students demand it, too.

We came face to face with this traditional demand of school - content over skills - in our progressive middle school. It is unfortunately too easy to believe that learning soft skills

is soft, meaning easy, and learning hard skills (content), is hard, and therefore worthy of school. We think it’s just the opposite, by the way, but this message is a difficult one for parents, students, and educators. For example, instead of finishing learning by virtue of a grade entered in the gradebook, good or not, the middle school introduced a policy of redoing work when needed, something central to mastery learning and standards-based assessment. You would think this is a win for education. Alas, not necessarily.

On average, our middle school students did not perceive our assessment system as enabling further learning. A serious school - we think this sums up their feelings - is hard and sometimes painful. Serious schools give Fs and make you stay up late to complete lots of homework.

And why not? It’s what they are used to. While we can disagree with them, it’s not hard to see where they are coming from. The vast majority of the models we experience, literally anywhere on the planet, work this way. School is in fact so predictable that when we walk into one in Moscow or Malaga, Taipei or Toronto, we can feel right at home. If you doubt this, ask a group of six-yearolds to “play” school. They will select one teacher, who will stand while the rest will sit, so the teacher can start asking them questions. We’ll even wager this: the child playing the teacher will quickly become a disciplinarian and delight in pointing out errors. Try it.

THE LEVER OF CHANGE MAY LIE OUTSIDE THE ACADEMIC DAY

Traditional school is built for predictable events. At the end of the unit there will be a test with questions. The questions will have right answers. And, perhaps almost comforting, one can study for them. Life, though, is full of complex questions with fluid responses. So like Don Quixote and Sancho going after the next windmill, we continue to implement progressive programmes in our traditional structure. Our justification is that we believe we can nudge education in a direction it needs to go.

We also feel that there is a place in school where experimentation with more progressive education does not suffer nearly as much from the gravitational reversion to the status quo. This is in our residential and extracurricular programmes, where, if we were clever, we might be creating much more curriculum, and planning much more instruction, than we currently do. In fact, we wonder if it might be these programmes that should be the drivers

That our educational system is in need of an overhaul shouldn’t be news to anyone. What can be much more difficult is making it happen.

of a focus on skills in addition to content. Perhaps it is only when the residential and academic programmes of school are functioning together, intentionally, that a school can fulfill its promise.

WHERE TO BEGIN

Student life outside the traditional bell schedule is a rich archipelago of clubs, sports and activities. These programmes offer more flexibility, are often much less hidebound or “curriculum bound,” and pave a path for schools to begin the process of implementing learning principles for the 21st (and 22nd) century. Here are a few steps to move forward:

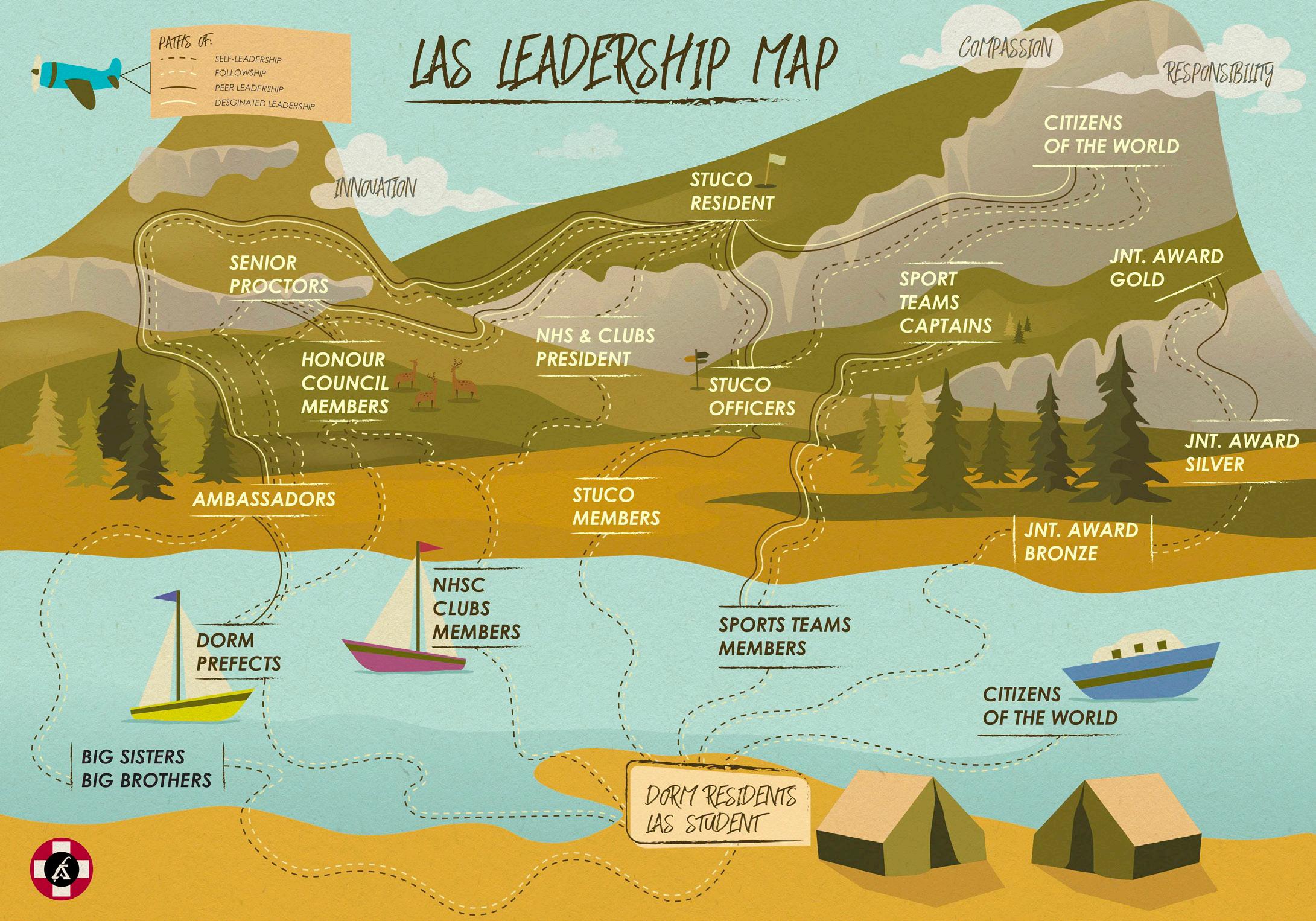

• Start with a definition of learning (see for example ACE Learning, 2017). • Ensure the definition of learning is transferable across all parts of the school. Curriculum does not end when the last bell rings. To be blunt, we are suggesting that the curriculum our students need often starts when the last bell rings. • Create opportunities to meet learning standards in many, if not most, parts of school life. If this statement does not make sense with your current standards, examine your current standards. • “Map out” the residential and student life curriculum. These maps provide orientation and keys to help students navigate their way. • Identify the skills that are, in fact, better suited for after school moments than inside the traditional classroom setting. Maximise their impact. • Avoid the easy temptation to make the residential and extra-curricular day more like the school day. Doing so, we believe, will lead to a loss of good learning experiences. • Extend curriculum planning into residential life and extra-curricular activities. • Define common understandings that describe the ethos of the school. For example, if a school is seeking to create leaders, then a definition of “leadership” must be defined. Then articulate pathways to be leaders and to practice leadership. Students should be able to understand the steps to becoming a leader, just as they need to understand the steps to solving a math equation. • Make multiple routes to reach learning goals known, across the entire school experience.

CONCLUSION

We might do ourselves a favour by examining residential and extra-curricular (even the name gives away our bias, doesn’t it) programmes and their role in leading a shift to greater inclusion of soft skills. For that matter, we might want to reconsider how we speak about soft skills. In the same training we mentioned earlier, our facilitator asked us to step into one of four quadrants which best described

the world we were preparing our students for: simple, complicated, complex, or chaotic. Most of us moved into the section called “complex.” He next asked us to move to the quadrant that best described our current curriculum, instruction, and assessment practices. We all moved to “simple.”

We can do better.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Daryl Hitchcock is the Theory of Knowledge department chair and a resident scholar at the Leysin American School. He has lived and worked throughout his career in boarding schools around the world, including more than 20 years as the head of large dorms of teenage boys. dhitchcock@las.ch

Paul Magnuson is the director of Educational Research at Leysin American School and adjunct faculty for the International Education Program of Endicott College. His interests include student agency and self-regulated learning for students and teachers. pmagnuson@las.ch

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Richardson, W. and Dixon, B. (2017). 10 principles for schools of modern learning. Modern Learners Media. Accessed 20 October 2019.