Eric Schlosser • Abalone • Cachagua General Store Grahm’s Gamble • Autumn Salt Foraging Member of Edible Communities edible monterey bay Celebrating the Local Food and Wine of Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Benito Counties 2011 Fall • Volume 1 • Number 1

www.ediblemontereybay.com 1

4GRIST FOR THE MILL

6EDIBLE NOTABLES

Fall foraging: collecting sea salt in Big Sur • Mundaka’s Gabe Georgis on creating community, one restaurant at a time • Lightfoot Industries discovers a recipe for happy, successful youth • A new guide to our local foodshed. Holman Ranch rolls out its own wines and olive oil.

12INTERVIEW ERIC SCHLOSSER

The author of Fast Food Nation talks with EMB about our locavores’ paradise, why eating sustainably is a social issue, and why he’s so optimistic.

16WHAT’S IN SEASON BIG SUR BAKERY’S SAVORY PUMPKIN BREAD

Michelle Wojtowicz’s seasonal recipe and a guide to the local fruits, vegetables, fish and nuts being harvested now.

18IN THE FIELDS PHOTO ESSAY

Salinas Valley farm workers by artist Jim Kasson.

21OUT TO SEA

A NEW TAKE ON THE FISHMONGER

Monterey Bay’s first CSF, a CSA for fish-lovers, will help sustain local fishermen.

24EDIBLE

ISSUES SAVING SCHOOL LUNCH

A national trend takes innovative forms at local schools as chefs and administrators join forces to change the way kids eat.

30ON THE FARM A FARM OF THEIR OWN ALBA incubator nurtures pride and produce.

32ROADSIDE DIARIES A NIGHT AT THE CACHaGUA GENERAL STORE

An Upper Carmel Valley adventure.

38THE PRESERVATIONIST QUINCE JELLY AND APPLE BUTTER

Happy Girl Kitchen Co.’s Jordan Champagne loves fall.

40EDIBLE HISTORY ABALONE

The history, lore and science of the Monterey Bay’s beloved gastropod.

44ON THE VINE GRAHM’S GAMBLE

Santa Cruz icon Randall Grahm’s most ambitious project ever finally gets into the ground; his Cellar Door and its new chef shine.

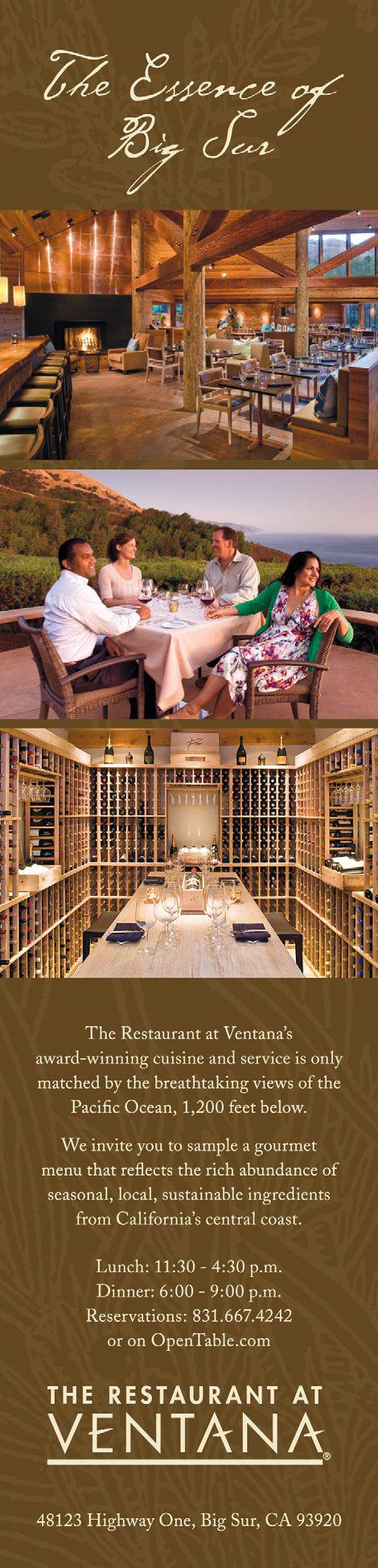

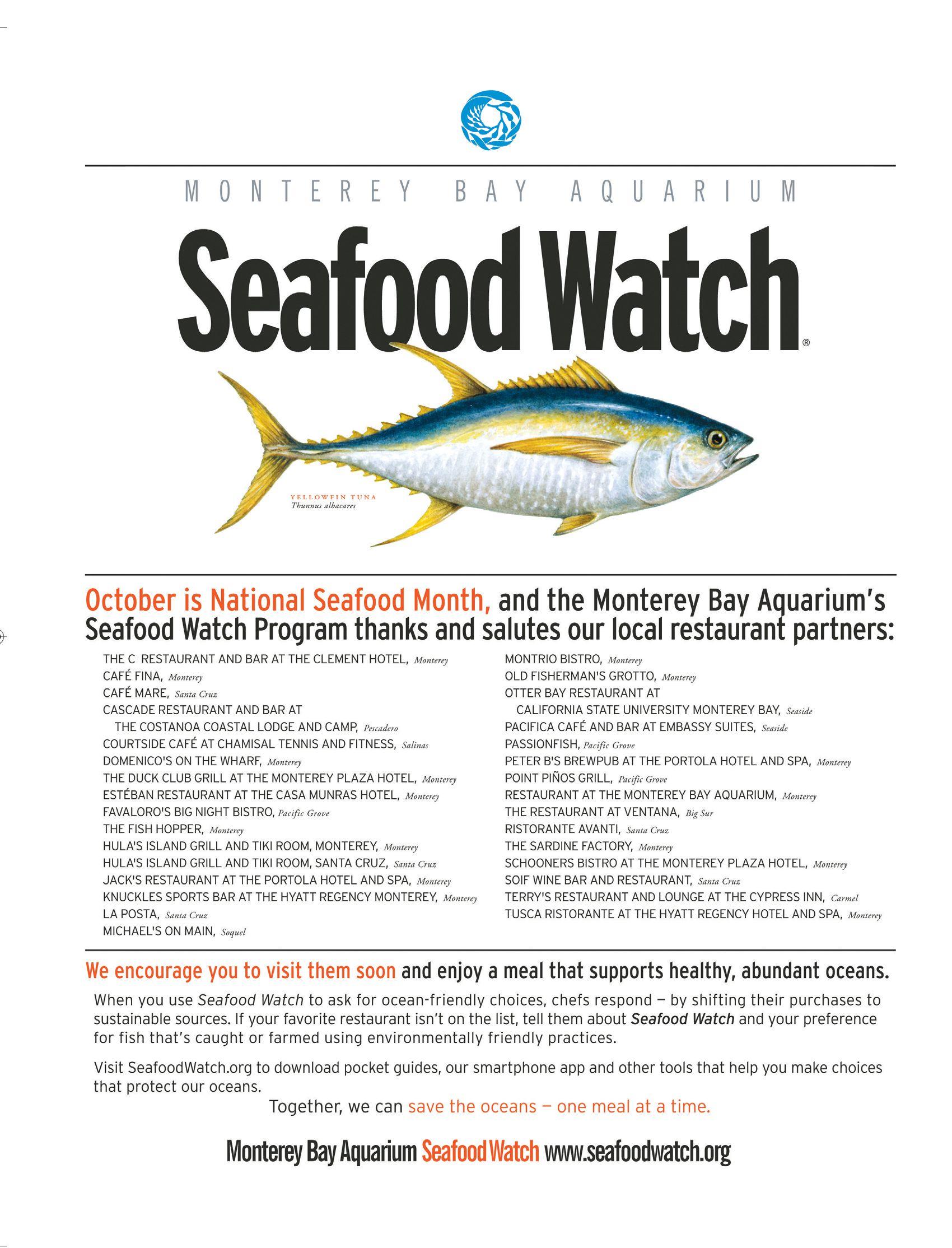

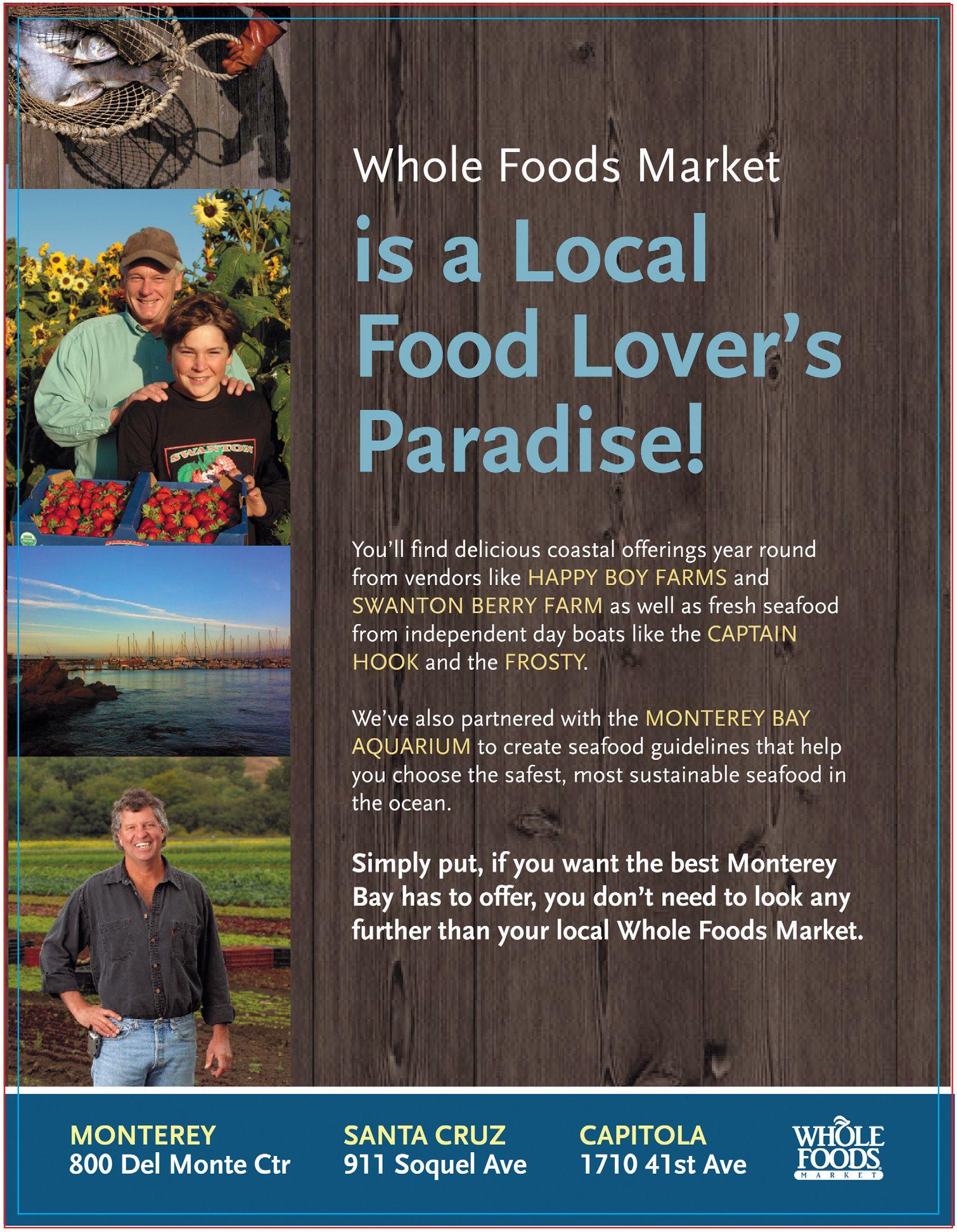

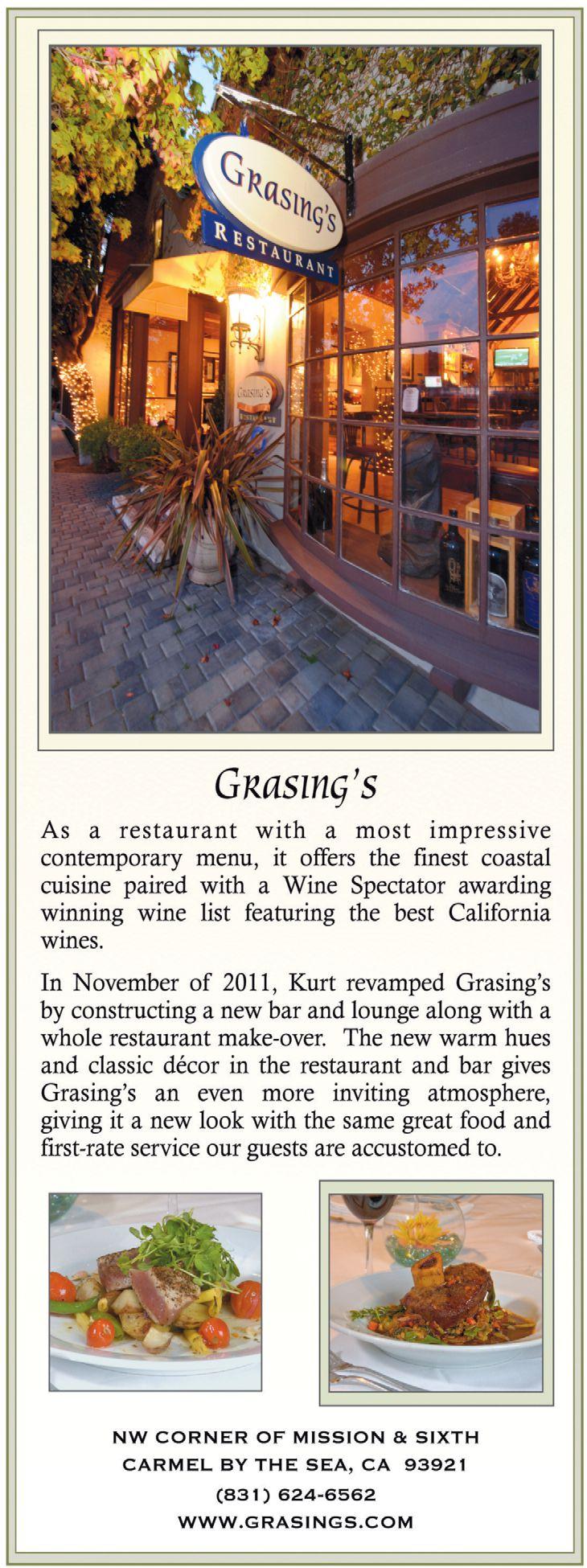

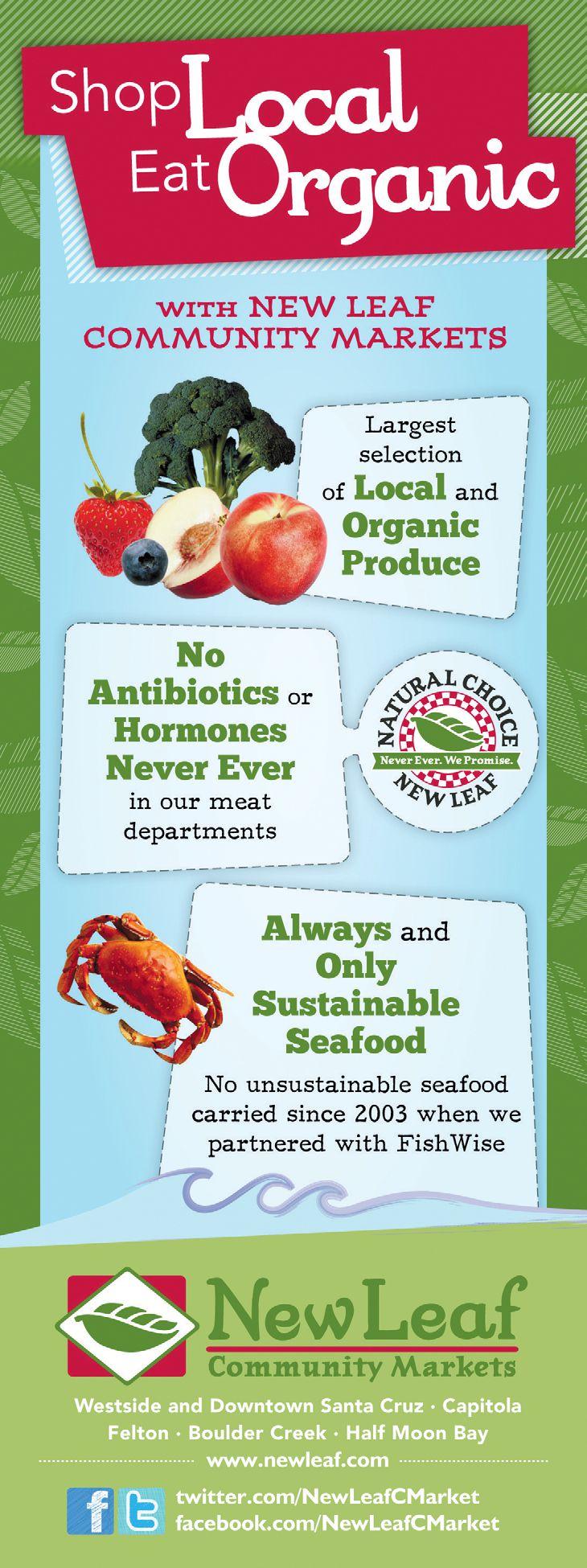

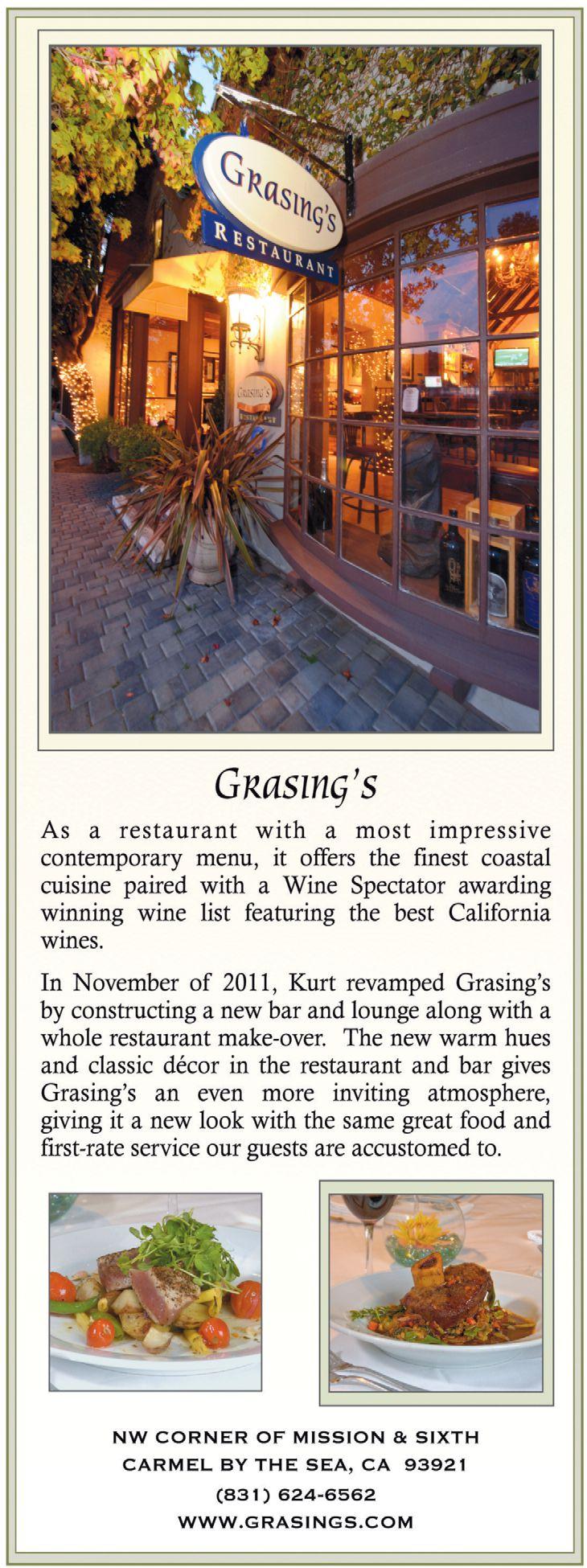

49DINE LOCAL GUIDE

A guide to some of the region’s best restaurants and cafes that emphasize local ingredients.

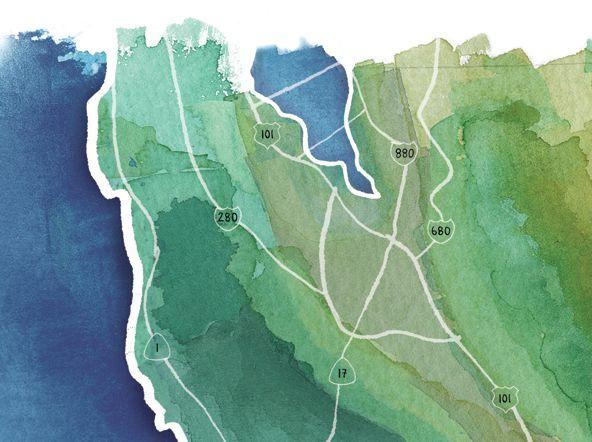

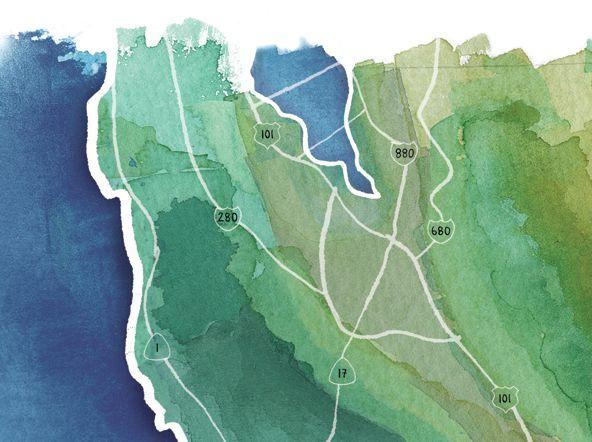

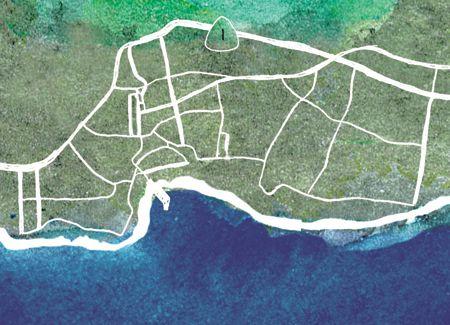

52Map of the Region/Advertiser Guide

Some of the best of everything that the region has to offer, on a convenient map!

55LOCAL LIBATIONS GOOD JUICE

At Oswald in Santa Cruz, Hans Losee serves it up fresh.

56FARMERS’ MARKETS

A comprehensive guide to the farmers’ markets of Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Benito Counties.

Cover photograph of abalone by John Cox

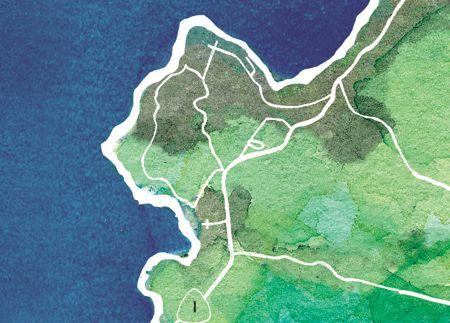

Contents photograph of Whaler’s Cove by Rob Fisher

2 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Contents

GRIST FOR THE MILL

It’s a huge pleasure and honor for me to introduce this inaugural issue of Edible Monterey Bay—and to thank the many people who’ve helped bring it to life. These are tough times for magazines, especially new ones. But in the coming months, I think you’ll find that this isn’t just any magazine.

Edible Monterey Bay is a magazine with a mission, and that mission is to help connect the people of Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Benito Counties who grow, harvest and prepare our food with the people who eat it, and to celebrate the amazing bounty of food and wine being produced here. We’ll especially highlight people who go about their business in sustainable ways.

We’re also excited to help the different communities within the region get to know one another better—and we hope you’re game to start exploring!

In these pages, you’ll read about salt foragers in Big Sur, Bonny Doon founder Randall Grahm’s bold new winemaking adventures in San Juan Bautista and school lunch heroes in Santa Cruz and all around the region.

Marking the 10th anniversary of his landmark book Fast Food Nation, local author Eric Schlosser talks with us about the state of our food system and why he’s feeling positive about it. A number of chefs and farmers speak about what’s important to them—and one chef, Michael Jones, will teach you a skill you never knew you’d need. Artist Jim Kasson shares a photo essay of farm workers, and chef John Cox of Cassanova and La Bicyclette takes us back in history to trace the rise and fall and slow recovery of abalone in our area.

On our website, you’ll find all kinds of additional features: a calendar listing food and wine events coming up around the region, biographies of our talented contributors, a listing of community supported agriculture (CSA) programs, recipes and more.

If there is a theme to this issue, it’s community—how important it is, what a vital role food plays in it all and what great rewards are in store when we’re intentional about creating it.

And speaking of community, I’d like to mention that Edible Monterey Bay is no island unto itself, but is one of 70 magazines in the Edible Communities family of locally owned and edited food magazines. Together, the group in May was honored with the James Beard Foundation’s first-ever Publication of the Year Award and I’d like to congratulate all my Edible colleagues and to thank them for their generous help in making our local Edible a reality.

Finally, I’d like to thank you, our readers, for caring about local and sustainably produced food. I hope you enjoy this issue, and use the beautiful map on page 52 to explore our area and patronize the advertisers who’ve given us critical support and enthusiasm when we needed it most. They provide some of the best of what the region has to offer, and they’ll appreciate your business!

Sincerely,

edible monterey bay

PUBLISHER AND EDITOR

Sarah Wood

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Rob Fisher

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Deborah Luhrman Lisa Crawford Watson

COPY EDITORS

Doug Adrianson • Doresa Banning

DESIGNER Melissa Petersen

WEB DESIGNER Mary Ogle

CONTRIBUTORS

Renee Brincks • Jordan Champagne

Jamie Collins • Cameron Cox

John Cox • Susan Ditz • Kurt Foeller

Ted Holladay • Jorge Novoa

Richard Green • Jim Kasson

Linda Ozaki • Richard Pitnick

Sara Remington • Pete Rerig

ADVERTISING

Shelby Lambert • 831.238.7101

INTERNS

Kalia Feldman-Klein • Katie Reeves

CONTACT US:

Edible Monterey Bay 24C Virginia Way Carmel Valley, CA 93924 www.ediblemontereybay.com 831.238.1217 info@ediblemontereybay.com

Edible Monterey Bay is published quarterly. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used without written permission of the publisher. Subscriptions are $28 per year at www.ediblemontereybay.com. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our apologies and notify us. Thank you.

4 edible monterey bayfall 2011

“If there is a theme to this issue, it’s community— how important it is, what a vital role food plays in it all and what great rewards are in store when we’re intentional about creating it.”

Edible Notables Fall Foraging: Salt from the Sea

by Jamie Collins

by Jamie Collins

Salt. Our bodies wouldn’t function without it, and food wouldn’t taste as good either. Experts disagree on how much salt a person needs to maintain good health. In his book Salt: A World History, author Mark Kurlansky notes that estimates range from two thirds of a pound to 16 pounds per year. Salt deficiency can cause headaches, weakness, nausea and even death, if the deprivation goes on long enough. The human love of salt is probably a natural defense mechanism that causes us to keep on reaching for it.

Kurlansky writes that ancient nomads got their salt from their cattle, which instinctively migrated towards salt ponds. Cultures that raised crops had a harder time meeting their salt quota: While a diet of vegetables is high in potassium, it contains little salt. So farmers began trading cultivated crops for salt, helping to make it a valuable commodity. Roads were built to transport and trade salt, revolutions were started over it, and eventually, people were paid with salt. Perhaps you’ve heard the expression “worth his salt.”

Nowadays, salt is still used as a precious currency here on the Central Coast, when autumn takes foragers down Big Sur’s cliffs to collect naturally forming sea salt.

The Big Sur Bakery serves its famous bread with unsalted butter and an array of sea salts to sprinkle to one’s liking. One of the salts is collected locally by Big Sur resident Brett Engel, and bartered for pastry chef Michelle Wojtowicz’s “death by chocolate” cake for his wife’s birthday each year. “We tend to use it sparingly since it is hard to come by,” Wojtowicz said of the salt. “I use it to garnish caramel desserts and Phil will use the salt to finish off a fish dish right before serving it,” she added, referring to her husband, chef Philip Wojtowicz.

Engel has been foraging salt from a closely guarded spot in the rocks just above the ocean in Big Sur for the past 20 years, ever since an alchemist friend shared the location of the pool, which Native Americans may have once used. The salt pond is the size of a bathtub and about 12 to 16 inches deep. Salt begins to collect in the pool, and

in others formed by depressions in rocks close to the ocean, after the summer sun evaporates seawater splashed into the pools by high winter surf.

Engel makes the annual pilgrimage each September, once the sun has done its work and the tides are low enough to allow the treacherous trip by rope down to the rocks.

“We first take the prized salt bloom, which looks like little flower buds on the top of the larger salt crystals below,” Engel said, “referring to fleur de sel, or “flower of salt.” “We only take what we can each carry up the ropes in our backpacks, which is about 40 to 50 pounds.”

“Each year the harvest is different depending on the weather— if the summer was foggy the salt may not have dried much, yielding less. The year of the Big Sur fires the salt ponds were filled with ash and the taste was surprisingly smoky and good.”

Engel has learned that the best time to collect salt is before the pampas grass goes to seed within the first two weeks of September: If they wait too long the salt will be filled with seeds. Engel says all salts taste different, and describes the taste of the salt he forages as buttery and delicious.

Todd Champagne of Happy Girl Kitchen Co. has also foraged sea salt in Big Sur with Engel, but just in small quantities for his family’s personal use. Happy Girl’s commercial organic kitchen in Pacific Grove uses large quantities of sea salt to preserve lemons and produce its pickle collection, and must buy its sea salt in bulk. Currently, Happy Girl sources it from the South San Francisco Bay–area label Giusto’s Natural Sea Salt and Sonoma Sea Salt.

If you don’t have the time or inclination to harvest your own sea salt, two local artisan salt companies produce sea salt from Monterey Bay by collecting seawater and evaporating it in special greenhouses: Monterey Bay Sea Salt (www.montereybayseasalt.com) and Monterey Bay Salt Co. (www.montereybaysaltco.com).

6 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Photograph by John Cox Sea salts naturally vary in color and taste.

Edible Notables Sustainable Community

by Sarah Wood

by Sarah Wood

Gabe Georis misses the Mediterranean Market, a specialty store and deli that operated at the corner of Ocean and Mission when he was growing up in Carmel in the 1980s. Not because of the sandwiches he bought there, but because of what happened when he and other customers congregated next door in Devendorf Park to eat them.

“Locals used to go there,” Georis said. “But nobody stayed in the store. You’d see everybody in the park—there was this whole social scene directly attributable to the store.”

Georis, an offspring of the Carmel family that for more than 30 years has run the highly regarded gastronomic empire that includes Georis wines and the restaurants Casanova, Corkscrew and La Bicyclette, has for the last couple of years been establishing a strong following for his own restaurant, the Spanish tapas spot Mundaka.

Mundaka, named for the Spanish surf town, is all about sustainability. It’s filled with character-laden reclaimed fixtures and it sources its seasonal menu from local organic farms—efforts that help promote conscious consumers and preserve the region’s family-farm culture, the environment and everyone’s health. And like all the Georis enterprises, the food, prepared by chef Brandon Miller, is transporting.

But like a growing number of restaurateurs around the region, Georis is seeking to help nurture and sustain community through the very experience of eating in his restaurant.

In many cases, people are doing this with communal tables, as at Bonny Doon’s Cellar Door and Lightfoot Industries’ supper clubs in Santa Cruz, FUD’s pop-up restaurants in Monterey and Dory Ford’s new incarnation of Point Pinos Grill in Pacific Grove, as well as the expanding number of dinners held on farms and in vineyards by the likes of the Bernardus Lodge and Winery, Hahn Estates and many others. (Getting people to eat with strangers, though, can take some coaxing, as Randall Grahm explains on page 47.)

“It’s not really just trying to create a restaurant; it’s trying to help build a sense of community back up,” Georis said of his own effort.

In Mundaka’s case, as at the others, diners can eat with strangers at communal tables, but Georis’s method is somewhat subtle, cagey. You might not even notice it, but there are no stools at the bar. So patrons, rather than being able to stake out a fixed spot, have to share space—and start conversations with someone they probably don’t know. Providing live music and dancing is perhaps a more conventional method, but the Mundaka strategy is working—in a town that of late has not been known for its nightlife.

“Everybody likes to listen to music and dance. People come in and boogie. Eighteen-year-olds to 70-year-olds are shaking it out,” he said.

Georis especially laments the city’s loss of more bohemian days, before a surge in real estate prices and other factors over the last few decades put pressure on the city’s sense of community and its youth culture, making intergenerational crowds shaking it out rare.

But he’s been encouraged to see other businesses create gathering places that appeal to the young, like the new restaurant Vesuvio’s roof bar. And as a result, the city is beginning to shed its sleepy reputation and is staying open later.

Next, he’d love to see the city’s iconic beach transformed into more of a catalyst for community.

“Wouldn’t it be great if you could have tables and chairs at the bottom of Ocean Avenue, in the sand?” Georis said. “We all respond to our environment, so if you create the environment, people will follow along.”

Mundaka is located in the Carmel Square shopping center on San Carlos St. between Ocean Ave. and 7th Ave. For more information, go to www. Mundakacarmel.com.

www.ediblemontereybay.com 7

“How do you create more community feeling? You create public spaces where people get to know each other.”

Photograph by Richard Green

Gabe Georis speaks with guests at Mundaka

“How do you create more community feeling?

Edible Notables

Lightfoot’s recipe for reinventing school

by Susan Ditz

fered in conjunction with Delta Charter High School in Santa Cruz. Lightfoot will also continue its supper clubs at DIG, and will be available for hire to cater events. Eventually, Kubas hopes to expand the program across the U.S.

Lightfoot is a hybrid nonprofit/for-profit organization, so it can operate a nonprofit academy while giving kids real-life business experience working with its roving restaurant.

The aim, Kubas said, is to provide marginalized teens with entrepreneurial training, an innovative curriculum and meaningful apprenticeships and, in so doing, develop the participants’ social, environmental and fiscal responsibility. The students learn about nutrition, farming, food preparation and food service. They attend yoga classes, learn social media proficiency and receive hands-on experience in developing new products and marketing a wholesale food line.

“It’s designed around a culture of achievement, with real incentives, reachable goals and in-depth integration with the teachers, and with the same graduation requirements of traditional high schools,” Kubas said. “We take a whole-person approach, giving young people critical guidance and marketable skills, so they can become fully engaged, responsible citizens.”

Kubas, who drew on her experience as a parent, restaurant consultant, soccer coach and teacher to conceive Lightfoot, became a proponent of sustainable vocational education years ago, “because people are diverse, so there can’t be just one method of education, and education needs to take a relevant, whole systems approach,” she said.

Santa Cruz social entrepreneur Carmen Kubas had one of her biggest aha! moments last spring, in the middle of a hot, crowded kitchen at her regular Saturday night supper club at DIG Gardens.

In the midst of what some might see as controlled chaos, Kubas realized that her vision for a sustainable vocational training program focused on food and the restaurant business was working: Her highschool-aged participants were using their newly acquired professionalism to pull together and do a nearly flawless job helping chef Loren Ozaki prepare and serve a delicious gourmet meal.

Kubas is the founder of Lightfoot Industries, one of a growing number of Central Coast organizations providing sustainable agriculture and culinary vocational education for youth. Rancho Cielo in Salinas, Food What?! (part of the Life Lab at UCSC) and the Santa Cruz County Office of Education’s Natural Bridges High all provide such programs. The groups are coalescing into a veritable movement around food-centered educational programs. (See related story p. 28.)

This fall, Lightfoot will move from a 10-month pilot project to a full four-year high school vocational program for 23 students, of-

“Vocational education is often seen as less valuable and desirable than college prep, but we need the infrastructure of skilled workers and artisans who are critical to the health of our economy—they are just as important as doctors and lawyers. And to be successful today, all high school students, regardless of whether college prep or not, need to learn the three principles of sustainability: social, environmental and fiscal responsibility.”

During the pilot program, Kubas saw every student grow—especially in discovering how to think for themselves. Each had a story.

“Kyle started out very shy and awkward as a busser and evolved into my lead server, who earned a stipend by showing up and pitching in for everything,” she said. “Enrique is another success story for us—he was totally introverted in the beginning, but learned how to speak up and delegate when he was put in charge of the dish area. He’s returning to do an internship in product development.”

Lightfoot’s weekly supper club dinners at DIG Gardens (420 Water Street, Santa Cruz) will be starting up again on September 30th. See www.lightfootind.com and diggardensnursery.com for the latest event information.

8 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Photograph by Linda Ozaki

Lightfoot founder Carmen Kubas with one of her students

Edible Notables

By Deborah

By Deborah

Did you know that in our region, Monterey County alone boasts more than 150 wineries? Whether you’re a longtime resident of Santa Cruz, Monterey or San Benito Counties or just passing through, the new California Welcome Center that opened over the summer just off Highway 101 in Salinas aims to help you get to know and enjoy the area better.

The center provides maps, information and a concierge service that can make hotel reservations and sell tickets to such attractions as the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The center is focused in particular on the region’s agriculture and wine, and will serve as a catalyst for development of farm tours and winery visits, both popular tourism products elsewhere in the state.

“I call it Napa version 2.0,” said Craig Kaufman of the Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau, which runs the center. “We have so many wonderful agriculture businesses here that people don’t know about, and what is being done at some of our wineries is truly amazing.”

It is a destination whose time has come. “We have what people are looking for in healthy eating and good wines,” he added.

Wine tourism is still in its infancy in the Salinas Valley, compared with places like Napa and Sonoma counties. For example, few people know that there are so many wineries in Monterey County or that it boasts nine different appellations or unique growing areas.

Visitors looking to sample Salinas Valley wines are directed to the River Road Wine Trail, which starts just south of Salinas and winds its way past 14 visitor-friendly wineries along the banks of the Salinas River south to Soledad. Or they are sent to tasting rooms in Carmel Valley, which include the award-winning Heller Estates and its certified 100% organic vineyards.

Farm tours are expected to get under way soon. Kaufman said they would begin with nationally known brands like Taylor Farms and Fresh Express—both producers of pre-packaged salads—and Ocean Mist, which grows 70% of the nation’s artichokes.

“You’ve got nearly 2 million people a year who come through here on their way to the Monterey Bay Aquarium who would also be interested to know how their food is grown,” he said, emphasizing that locals will also be welcome on the tours.

Developing agrotourism or winery tourism is not part of the county’s general plan, and that makes the permitting process for farm stays and wine tasting rooms extremely complicated. While tourism officials acknowledge the need to preserve farmland, they also report it can take years to open a new tasting room and that wineries are not yet allowed to operate bed-and-breakfast accommodations.

Sites related to writer John Steinbeck and the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas are also promoted by the new center. European tourists are especially drawn to the Steinbeck literary trail and enjoy visiting spots mentioned in his famous books, such as East of Eden and Cannery Row.

The Welcome Center is located in the Westfield Shopping Center at 1213 N. Davis Rd. on the West Laurel Drive exit off Highway 101. It is open 9am–7pm daily. In addition to travel information, it provides for the basic needs of travelers and their pets, with public restrooms, picnic tables next to a cool pond and a dog walking area.

www.ediblemontereybay.com 9

“I call it Napa version 2.0. We have so many wonderful agriculture businesses here that people don’t know about, and what is being done at some of our wineries is truly amazing.”

Attention adventurous locavores and oenophiles!

Luhrman

photo courtesy of California Welcome Center

The welcome center is already attracting plenty of business.

Edible Notables

Holman Ranch launches new homegrown products

By Renee Brincks

Five years after acquiring Holman Ranch, its owners are adding a new chapter to the property’s storied history. The first estate-grown wines and olive oil from Holman Ranch Vineyards have hit shelves, and construction of a new on-site winery wraps up this fall.

The late Dorothy McEwen, who owned Holman Ranch from 1989 to 2005, first introduced vines to the resort grounds. Though she planted only 1 1/2 acres, her goal was to build a 25,000-case winery. Current plans are more modest—2,000 to 3,000 cases a year at most, according to Holman Ranch Director of Hospitality Hunter Lowder—but guided by a similar vision.

“We focus on the past of the ranch—the history, romance, memories—and the future,” she says. “And it’s all about using the land for what it does best.”

Lowder was attending a wedding at the old Hollywood hideaway when she learned it was for sale following McEwen’s passing. She persuaded her parents, whose European travels had left them with dreams of tending grape vines and olive trees in their retirement, to take a look at the 400-acre property. They were skeptical, initially, because the land was more than they envisioned for themselves. Still, Lowder insisted that they visit.

“They saw the mountain views and the hacienda and really saw the potential,” she says. “It’s not just about having a family vineyard; it’s having a family business.”

Thomas and Jarman Lowder took over Holman Ranch in 2006 and began renovations that modernized the grounds, stables and 1928 stone hacienda building. They planted 17 additional vineyard acres, and the winery will be completed in the coming months. A series of caves dug into the hills houses the crush pad, barrels and storage facilities.

“It’s a very low-impact, low-footprint, modular type of winery,” Lowder says.

Though the facility will not be open to the public, guests can sample Holman Ranch wines at a new Carmel Valley Village tasting room

opening later this year. Neighboring restaurant Will’s Fargo pours them, as well, and a wine club is in development. Selections include a 2009 Pinot Noir aged in French oak, and 2010 wines ranging from Pinot Gris and Chardonnay to Sauvignon Blanc and rosé of Pinot Noir.

“We really wanted to be a Pinot house because we’re located in the Carmel Valley appellation, which is a small and very rare appellation. All our wine is from estate-grown vines; we don’t bring in any grapes, and we don’t sell our grapes,” Lowder explains.

She says the earliest releases, which “came out pretty complex and tasty,” have earned positive feedback for their originality. The Pinot Noir, for example, falls somewhere between the traditional flavor of a French Burgundy and the fruit-forward blends from the nearby Santa Lucia Highlands.

“We wanted to try and span the generations of different wine drinkers,” Lowder says.

In addition to growing the property’s wine program, the Lowder family also planted a grove of 100 Tuscan-varietal olive trees at Holman Ranch. Only a small quantity of this year’s extra-virgin, coldpressed olive oil remains.

“It has a little bit of a spice on the back of the throat, and a little bit of greenness, but it’s buttery on the finish,” says Lowder.

Like the wines, the olive oil is particularly popular with people who have ties to the property.

“The romance and history of Holman Ranch and Carmel Valley ... you get a piece of that,” says Lowder.

To order wine or olive oil from Holman Ranch Vineyards, call 831.659.2640 or email wines@holmanranch.com. Resort, wedding and vineyard information is at www.holmanranch.com.

10 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Photograph courtesy of Holman Ranch

Holman Ranch is located on 400 acres in Carmel Valley

www.ediblemontereybay.com 11

INTERVIEW

ERIC SCHLOSSER

The author of Fast Food Nation and co-producer of Food Inc. sits down with Edible Monterey Bay at the Wagon Wheel.

Interview by Sarah Wood Photograph by Richard Pitnick

12 edible monterey bayfall 2011

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the publication of Fast Food Nation, the seminal work by award-winning investigative jouralist and local resident Eric Schlosser. The book exposed the ills of the highly centralized and industrialized U.S. food system, and in many ways set the agenda for efforts to reform it over the last decade. His next book, Reefer Madness, provided fuel for the movement to improve the plight of migrant farm workers.

Since Fast Food Nation came out, Schlosser has also become a devoted food activist, focusing on improving food safety and farm worker rights, curbing childhood obesity and bringing about a more sustainable food system in general.

In May, he helped organize with the Washington Post a major conference on the future of food. His comments and those of many other leaders of the sustainability movement can be found on the Post’s website.

This past summer, Schlosser took time out from the books he’s working on now—one on nuclear weapons and another on the prison system— to talk about food, our region and why he’s optimistic about the future.

Edible Monterey Bay: You moved to the Monterey Bay area from New York City a few years after Fast Food Nation was published. What brought you here?

Eric Schlosser: I lived in Big Sur a while ago, and my wife and I got engaged there. We’ve always considered the Central Coast one of our favorite places in the world. It’s quiet and beautiful and a great place to raise kids. I write about a lot of dark things, and this whole area offers a good counterbalance.

EMB: Where do you like to eat?

ES: We love the Big Sur Bakery, Nepenthe, Mundaka, Carmel Belle, La Bicyclette, Katie’s, Akaoni, Hanagasa, the Wagon Wheel. And we also like eating at home.

EMB: You started your writing career by editing your college humor magazine, but as you say, your journalism gets into pretty grim areas; in fact, you’ve explored and exposed all manner of exploitation of the weak by the powerful. What do you do to find respite from these heavy topics?

ES: You know, most people assume that I must be a pretty bleak guy, with my office walls painted black, listening to thrash metal bands like Slayer and Megadeth all day. But I try hard to enjoy the day. Fundamentally, I’m optimistic. I’m driven by the belief that things don’t have to be the way they are. And that may be what helps me to explore these dark subjects for long periods of time. There’s a lot of laughter in our household, usually at my expense. And when life starts feeling grim around here, you can just walk outdoors, look around and put things in the right perspective.

EMB: You never planned to write about fast food—Rolling Stone asked you to. And yet, writing about it seems to have changed your life: You’re an extremely private person, but you became an ardent food activist. Are you glad your path took you down this road?

ES: I feel lucky beyond words to have written a book about issues that I care about—and to find that other people care about them, too.

EMB: What reforms have you been most gratified to see come to pass?

ES: The most gratifying thing hasn’t been any specific legislation or reform. It’s been the sea change in attitudes that’s occurred since the late 1990s, when I first began to investigate our food system. So many of the issues that once seemed to be on the fringes of society— like food safety, childhood obesity, animal rights, the need for healthy, organic food—have entered the mainstream. I wrote Fast Food Nation because I thought these things weren’t being discussed and debated in the media. And now they are, on a daily basis. I’m not taking credit for the change. I just feel incredibly relieved that it’s happened. And there’s no turning back. When most people see how this industrial food system really works, they don’t want to be part of it any more.

EMB: What about the Food Safety Modernization Act?

ES: Like everything that Congress does, it was a compromise. But it was also a good first step toward improving food safety without harming small producers.

EMB: What continuing problems with our food system are you most concerned about?

ES: I’m concerned about the overuse of antibiotics by factory farms. It’s created superbugs that threaten everybody, regardless of whether you eat this industrial meat. I’m concerned about the ways in which companies still market unhealthy food to children and prey upon the poor. I’m concerned that genetically modified foods and the meat from cloned animals are being sold without any labeling. I’m concerned about the cruelties inflicted every single day on the livestock at factory farms—and on the workers who harvest and process our food. These battles are far from being won.

EMB: A lot of fast-food chains have added salads and other “healthy” items to their menus. But in its August edition, Consumer Reports magazine disclosed that only 13% of respondents to its first survey of fast food customers said they’d chosen something “healthy” on their last visit to a fast food outlet. What do you make of that?

ES: I’m delighted when any of these chains puts something healthy on their menu. McDonald’s just announced that they’re going to add

www.ediblemontereybay.com 13

fruit to their happy meals. That’s great. But it would’ve been a lot greater if they’d done it 10 years ago. I question the sincerity of these moves. It’s all about PR and marketing. But if that’s what gets someone to do the right thing, well, it’s better than nothing.

EMB: Despite America’s lingering bad food habits, you say critics have it all backwards when they say that being a foodie—and more to the point, being a conscious eater and supporting sustainable food production—is elitist.

ES: Wealthy people will always eat well. We don’t need to worry so much about them. They’re doing fine right now. The people who need organic food the most are the people who pick our fruits and vegetables by hand. And the people who live in agricultural communities. And most of all, their children. Tens of thousands of farm workers are sickened every year by pesticide exposure. These are incredibly toxic poisons. We need to get these pesticides out of rural America, out of the water, the households, the air. And we need to get them out of our food. As for the urban poor, they are being sold some of the most heavily processed, unhealthy food on earth. And they can least afford the obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer and high blood pressure that soon follow. Our current food system is profoundly elitist. I think a living wage, and a safe

workplace, and access to good, healthy food are basic human rights. And right now millions of Americans are being denied them.

EMB: In this issue, we quote a local school food services director saying that some farm worker parents avoid feeding their kids vegetables because they’re so familiar with pesticides and don’t want their children to be exposed to them.

ES: I am much more concerned about the pesticide residues in the air, the dust, and the clothing of farm workers than I am about the pesticide residues in their food. We need to get these poisons out of everybody’s homes and out of the environment.

EMB: What do you think are the best hopes now for getting farm workers into fields where they don’t have to worry about pesticides—and getting more organic food on their tables, and those of other lowincome Americans?

ES: If people who can afford organic food buy a lot of it, the supply will increase and the price will come down. That’s how the market works. It will increase the amount of acreage that’s organic—and the number of people who can buy organic.

14 edible monterey bayfall 2011

EMB: Are you hopeful that the 2012 farm bill will help?

ES: We’ll see. Despite all my optimism, it’s hard to be hopeful about anything in Washington, D.C., especially this Congress. But I do think there will be a strong push to make the bill take into account the interest of consumers, not just agribusiness companies.

EMB: Are you encouraged by shifts in public sentiment and agricultural practices in our own region?

ES: I am encouraged. There are a lot of farmers here, big and small, who are trying to do things more sustainably. And if you want to be a locavore, it’s hard to imagine a better place in this country to eat local.

EMB: Your book Chew on This aimed to deliver the message of Fast Food Nation to teenagers, and it became a New York Times bestseller. Aside from giving our kids books like yours to read, what else can we do to raise our children to be responsible eaters?

ES: I’m a big believer in trying to make people think, instead of telling them what to do. And that applies, most of the time, to kids, too. I think once they understand how the current system works, they’re eager to eat differently. For me, it’s all about being aware. And action follows from that.

EMB: What do you think are the most important things we can each do as individuals to reform our food system?

ES: Support your local farmer. Try not to give money to food companies that are causing great harm. And get engaged, one way or another, with groups that are trying to make change on a local, state or national level. There are about a dozen or so companies causing all these problems—and more than 300 million Americans. We ought to be able to change how that dozen behave.

EMB: Do you think that “sustainable” will ever become “conventional” in the agricultural world?

ES: It won’t happen overnight. But as the real costs of the current system become clear—and as the companies responsible for the problems are made to pay for them—the pace of change will accelerate. This industrial, “conventional” way of farming is clearly unsustainable. So we’re going to have to embrace a new way, and the sooner the better.

EMB: When it comes to fast food, you’ve said that after writing Fast Food Nation, you stopped eating at most chains other than In-N-Out Burger. Do you miss any of the rest?

ES: My diet is far from pure. But I have zero desire to eat that processed, industrial stuff. When I want to eat a burger, fries, pancakes or a chocolate chip cookie, I want the real thing, not some phony imitation of it. The best thing about McDonald’s is the toilets, which are generally clean.

www.ediblemontereybay.com 15

What’s in Season? Big Sur Bakery’s Savory Pumpkin Bread

By Renee Brincks Photograph by Sara Remington

For Michelle Wojtowicz of Big Sur Bakery, autumn means menus built around seasonal delights such as quince, apple and, of course, pumpkin.

Pumpkins don’t have a dominant flavor, she says, so they mix well with sweet potatoes, Butternut squash and a variety of spices. The restaurant’s popular pumpkin yeast bread, seasoned with cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger and sea salt, puts a surprising twist on the traditional fall fruit.

“It’s a table bread—it’s a bread to have with dinner, or to make French toast out of in the morning, or to use for croutons. It’s not a sweet bread,” Wojtowiczsays. “You get all the flavors of a pumpkin pie, but in more of a savory option.”

To sample the pumpkin bread, visit the Big Sur Bakery this fall season, reserve a seat for the restaurant’s traditional Thanksgiving Day dinner or make it yourself at home with this recipe from the Big Sur Bakery Cookbook.

Pumpkin Bread

Big Sur Bakery

1 pound fresh or canned pumpkin purée

10 whole allspice berries

4 whole cloves

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

2 teaspoons ground ginger

2 teaspoons active dry yeast

4 3/4 cups bread flour, plus extra for dusting

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon powdered milk 1 egg

1/2 cup plus 3 tablespoons (packed) light or dark brown sugar

1 tablespoon fine sea salt

1/4 cup unsalted butter, softened

Makes two pumpkin-shaped loaves

Start the night before: Put the pumpkin purée in a sheet of cheesecloth. Bundle it up and tie it. Put a rack inside a large pan, suspend the bundle over the rack, and let it drain in the refrigerator overnight to release the excess moisture, leaving behind only the dense pulp.

The next day, remove the pan from the refrigerator. Discard the liquid collected in the bottom, and reserve the pulp in the cheesecloth.

Grind the allspice and cloves in a spice grinder, and combine with the cinnamon, nutmeg, and ginger.

Pour 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons lukewarm water into a bowl, and rain the yeast over it. Stir, and set it aside to activate for 5 minutes.

In an electric mixer fitted with the dough hook attachment, combine the yeast mixture with 3 cups of the flour and the powdered milk, egg, brown sugar, sea salt, and pumpkin purée on very low speed. Over a 1-minute period, add the spice mixture and the remaining 1 3/4 cups flour, a scoop at a time. Add the butter and mix until combined. Turn the speed up to medium and mix for 2 minutes. Stop the mixer, scrape down the sides of the bowl with a rubber spatula (the dough should be sticky), and then mix on high speed for 5 minutes. The dough will become shiny, somewhat firm, and less sticky. Transfer the dough to a bowl that’s large enough for the dough to double in size. Place the bowl in a large plastic bag, tie it loosely, and set it aside in a warm place in the kitchen until the dough has doubled in size, 1 to 1 1/2 hours.

Turn the dough onto a floured surface and divide it in half. Pinch off a nugget of dough about the size of a walnut from each of these halves; these will be used as the stems of the pumpkins. At this point you should have two large pieces of dough and two walnut-size pieces. Flatten each of the dough pieces with the palm of your hand and roll them into loose balls. Cover with a plastic bag and let them rest for 10 to 15 minutes.

16 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Michelle Wojtowicz oversees bread baking and desserts at Big Sur Bakery.

Local foods in season now:

Fruit: Apples • Avocados • Figs • Grapefruit • Kiwi Melons • Lemons • Persimmons • Plums • Pomegranates Oranges • Peaches • Pears • Quince • Raspberries Strawberries • Tomatoes • Nectarines

Vegetables: Artichokes • Arugula • Basil • Beets • Bok Choy Broccoli • Brussels Sprouts • Cabbage • Carrots Cauliflower Celery • Chard • Collards • Corn • Cucumber • Eggplant Garlic • Kale • Leeks • Lettuce • Mushrooms • Mustard Greens Onions • Bell Peppers • Potatoes • Radishes • Spinach • Squash Sprouts • Sunchokes • Turnips • Wheatgrass

Nuts Almonds • Chestnuts • Pinenuts • Pistachios Walnuts

Fish Albacore Tuna • Cabezon • California Halibut Dover Sole • Lingcod • Market Squid • Pacific Sardine Petrale Sardine • Rock Crab • Sablefish • Shortspine Thornyhead • Spot Prawn • Swordfish

Source: CAFF and area farmers’ market operators

Reshape the dough pieces into tight balls. Line two medium bowls with a linen napkin and dust them generously with flour. Put one of the large dough balls in each bowl. Top each large ball with a small dough ball. Loosely cover each bowl with plastic wrap, giving it room to expand, and let the dough rise in a warm place in the kitchen until doubled in size, 1 to 1 1/2 hours.

Meanwhile, adjust the oven rack to the middle position and put a baking stone on it. Place a cast-iron skillet on the bottom rack of the oven and fill it 2 inches deep with water (to increase the level of moisture inside the oven). Preheat the oven to 450°.

Gently turn one of the pumpkin breads into your hands. Put the bread on a floured pizza peel (a flat wooden or metal shovel with a long handle) with the stem side up. With a razor blade or a sharp paring knife, make 1/4-inch-deep cuts into the bread, from the stem to the bottom, to create the ribs of the pumpkin. Immediately slide the bread directly onto the baking stone. Reduce the oven temperature to 375° and bake for 35 to 45 minutes, until golden brown.

While the first pumpkin bread is baking, place the second one in a cooler spot to prevent it from over-proofing.

The bread is done when a thermometer inserted in the middle reads 200°. Transfer it to a wire rack and let it cool for at least 1 hour before cutting.

Repeat the process for baking the second pumpkin.

www.ediblemontereybay.com 17

IN THE FIELDS FARM WORKERS

A photo essay

Photographs by Jim Kasson

Photographs by Jim Kasson

A big part of Edible Monterey Bay’s mission is to tell the stories of the people who grow and harvest our region’s food.

Elsewhere in this issue we’ve interviewed several farmers, including a vintner, a couple of abalone producers and three vegetable growers who got their start through the Agriculture and Land-Based Training Association (ALBA), which helps former farm workers and other low income people acquire and run their own farms. One farmer, Jamie Collins, wrote about salt foraging.

Here, the magazine pays tribute to the thousands of farm workers in our area, which is believed to host the largest concentration of such workers in the country. Farm workers labor without the same legal protections as other workers, often under arduous conditions and frequently with exposure to toxic pesticides. Farm workers with no legal status in the U.S. lead an especially precarious existence.

The photographs in this essay were created by Carmel Valley artist Jim Kasson as part of his series “This Green Growing Land.” Aiming to create archetypal images that represent all farm workers, he used stylization and abstraction in the images. Kasson achieved this effect by taking the photos from a moving car and using panning to focus on some aspects of the scenes he portrays, and blur others. He then printed the photographs in muted pastels.

Edible Monterey Bay is very grateful to have the opportunity to publish some of the images in this series, which can be found in its entirety at www.kasson.com.

—Sarah Wood

Opposite, from top to bottom: Picking Strawberries, Davis Rd., Salinas; Burning Debris, Old Stage Rd., Salinas; Boxing Lettuce, Harris Rd., near Spreckles. Overleaf, top to bottom: Discing in Gypsum, Castroville Rd., west of Salinas; Irrigation Worker, Castroville Rd., west of Salinas; Worker and Sunflowers, Molera Rd., near Castroville.

18 edible monterey bayfall 2011

www.ediblemontereybay.com 19

20 edible

2011

monterey bayfall

A NEW TAKE ON THE FISHMONGER

Monterey

Bay’s first CSF, a CSA for fish-lovers, will help sustain local fishermen

By Pete Rerig Photographs by Richard Green

Kathy Fosmark knows fishing. There are five generations of the life in her blood, and few people are in a better position to understand the nuances of the trade in Monterey.

“Thirty years ago, most of the fish and crab my family caught were sold to the local community, often right off the boat,” says Fosmark. “Now nearly all our crab goes to China and our albacore goes to Spain. The relationship between fishermen and consumers has changed so drastically, and it’s harder and harder to make a living from the sea.”

Taxes, fuel, safety inspections, crew salaries, insurance premiums—it’s little wonder why the local fleet has diminished in recent years. “We have so many forces challenging us now—stock quotas and permit acquisitions take a huge bite out of our profits and hamper our access to the ocean—and the result is young people don’t want to get involved in the business,” adds Fosmark, who also chairs the nonprofit Alliance of Communities for Sustainable Fisheries. “What we need is more desire from the public for fresh catches from local waters. We need to reconnect people with the seafood they eat.”

With a continually evolving set of rules and regulations governing what can and cannot be caught, for the past 15 years the friction between fishermen and conservationists has become highly contentious. “The layers of precautionary management have led to a lot of uncertainty about the future,” says Steve Scheiblauer, Harbor Master for Monterey. “Unfortunately, fishermen here are undervalued, and they don’t have a strong enough connection to their consumer base. Throw in rising gas prices and a dwindling availability of fish, and the situation becomes even more bleak.”

Now, there’s help on the horizon—a community-supported fishery, or CSF, modeled on the widely popular farm-produce subscription programs known as community-supported agriculture (CSA).

Enter Alan Lovewell and Oren Frey, both of whom are Sea Grant fellows and graduates of Monterey Institute of International Studies. “Alan was the first one to notice the real lack of CSFs on the West Coast,” says Frey. “There are organizations from Maine to Florida that

www.ediblemontereybay.com 21 OUT

TO SEA

Oren Frey at Monterey’s harbor

have been operating for decades, and yet in California there are only three—one in Half Moon Bay, currently available only to Google employees, and others in San Luis Obispo and San Francisco. So the time is ripe to get a CSF up and running on the Monterey Peninsula.”

The premise behind a CSF is simple: Customers buy a share or membership in the program, and each week they receive a box of fresh-off-the-boat seafood. And because the week’s catch is dictated by what’s in season and can be caught in a responsible, sustainable way, each week will bear surprises.

“We’ll work with a buyer/processor, who’ll act as a middleman between the CSF and the fishermen. They’ll control quality and negotiate prices, making sure everyone involved is getting the best deal available.”

It’s possible, Frey adds, that a share won’t be available to customers each week, which adds to the educational aspect of the program. “The lion’s share of seafood consumed in the U.S. travels

thousands of miles to get here. But when weekly boxes contain only what’s available locally at any given time, people will understand the quality of what they’re getting, as well as the importance of responsible fishing and consumption.”

As much as this will be a boon to the local food community, it will help the fishermen who participate even more. “By guaranteeing them a higher price for their catch, they can avoid the market fluctuations that plague the industry,” says Frey. “The fishermen will have a more stable consumer base, and they’ll be able to expand their business and reach a larger market.”

And there are myriad other benefits, like bringing consumers and fishermen together in a decidedly non-antagonistic way. “We want the CSF to connect people in the community. Customers can put a face to the fishermen who provide their catch. We can make them aware of conservation issues, and hopefully end the polarization be-

22 edible monterey bayfall 2011

“We want the CSF to connect people in the community. Customers can put a face to the fishermen who provide their catch. We can make them aware of conservation issues, and hopefully end the polarization between those who make their living from the ocean and those activists trying desperately to protect the environment.”

tween those who make their living from the ocean and those activists trying desperately to protect the environment.”

One person on the front lines of the issue is Jim Anderson, who runs the CSF arm of the Half Moon Bay Fishermen’s Association, started with the help of Google, Inc., and currently available only to the company’s employees. “We’re still a relatively small outfit, with just a handful of boats,” says Anderson. “But the response and support from Google has been extraordinary. We’ve been up and running for only a month, and the fishing hasn’t been great, but everyone involved sees good things coming in the near future.”

Lesley Milton, who belonged to a CSF in Seattle before she moved to the Monterey Bay area, is eager for Local Catch Monterey to get up and running. “Getting my weekly shipment was always a highlight of my week,” she says. “I knew that what I was eating was incredibly fresh and was helping local fishermen. It was just one small way that I could make a big impact on the environment as well as the local economy.”

Local Catch Monterey is still in the planning and organizational stage, but the general plan is to offer shares on a seasonal basis, with customers paying fishermen up front for three months’ worth of fish. As EMB went to press, Frey and Lovewell were leaning towards offering a choice of full or half shares. The weekly cost of a full share would average about $32 for three pounds of fish and the weekly cost of a half share would be about $16 for 1 1/2 pounds of fish. The species will vary with the season.

One downside of the model is that because the shares must be purchased up front, the program won’t be able to cater to sponta-

neous cravings or specialized shopping lists for that special fish you want for that specific number of people you’re having on the particular date you’re having a dinner party.

But the upside of the limited flexibility of the model is that it is sure to leave plenty of business for more traditional fish purveyors in the area.

Frey and Lovewell hope to begin selling shares by early 2012. “We want to create the framework, and then let the CSF grow organically. Our major goal is to build relationships in the community— we want to show that fishermen and conservationists don’t need to work against each other, that with practical collaboration everyone can come out a winner.”

And for Fosmark’s family and other fishermen plying the waters of Monterey Bay and beyond, that’s the best news possible. “If the public really wants the types of products the CSF provides, the boats will come back and the industry will grow,” she says. “There’s real value in programs such as Local Catch Monterey—we just need to rebuild the community connections that have been lost.”

How can you help? If you’re interested in becoming a customer, signing up on Local Catch’s waiting list will help the organization gauge interest. To sign up and learn more, go to www.localcatchmonterey.com

www.ediblemontereybay.com 23

Saving School Food

By Deborah Luhrman

Photographs by Deborah Luhrman and Richard Green

By Deborah Luhrman

Photographs by Deborah Luhrman and Richard Green

24 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Photo by Richard Green

Not long after signing on to manage food services for Santa Cruz City Schools, chef Jamie Smith was moving out an old piece of kitchen equipment when he spotted a greasy, smiley-faced disc of processed potatoes on the floor.

“That potato product thing had been there for six months at least,” he said. “It had been through heat and cold, wet and dry, yet it showed no visible signs of decay. Mold wouldn’t even grow on that scary thing, but still it was counted as a vegetable by the USDA!”

This fall, a vortex of factors is combining to ban those kinds of frankenfoods from the cafeteria and make school food part of the lesson plan for teaching kids how to become healthy eaters.

At the center of the vortex are British celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and his Food Revolution TV show, as well as Jan Poppendieck’s groundbreaking book Free for All: Fixing School Food in America, and First Lady Michelle Obama’s campaign against childhood obesity. But equally influential is our own Central Coast Farm to School program, which is now part of the Healthy Kids Act signed by President Obama last December.

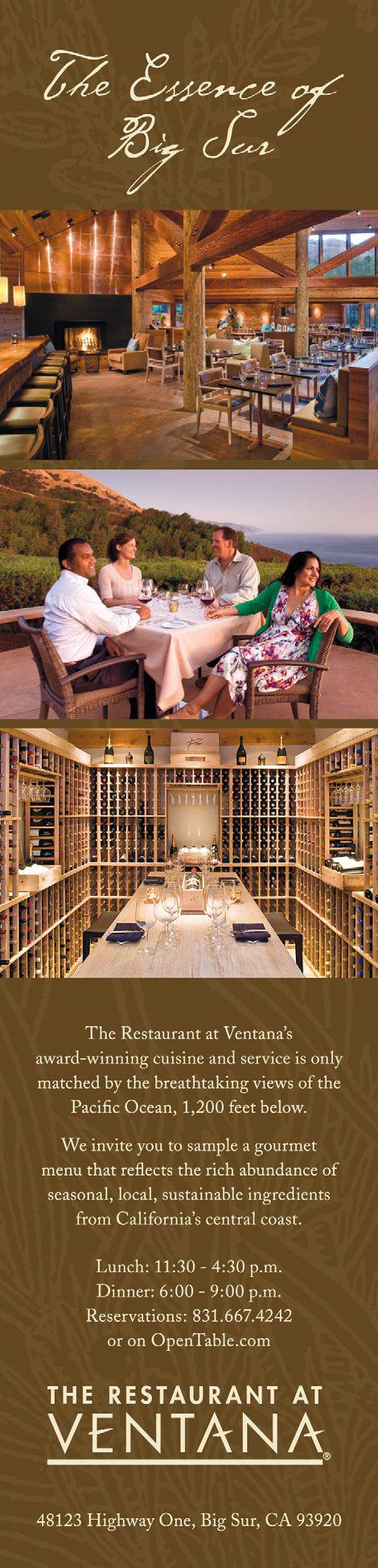

Perhaps it is not surprising then that school food, once the turf of lunch ladies in hairnets, is now attracting rock-star chefs like Smith— who got his start at New York’s famed Union Square Café and once owned Santa Cruz’s popular Sestri restaurant. In Monterey County, chef Dory Ford—formerly of the Ventana Inn and the Monterey Bay Aquarium and now chef at Point Pinos Grill in Pacific Grove—prepares school lunches, as does Earthbound Farm Executive Chef Sarah LaCasse.

They are joined by dozens of tireless food service directors, school board trustees and PTA members throughout the Monterey Bay area who are working in fits and starts to health-up and transform the food kids eat at school.

“My goal is to make people understand that nutrition is as important as education,” said Kimberly Clark, head of Student Nutrition for San Lorenzo Valley schools. “You can have a wonderful teacher who imparts wonderful knowledge, but if the student is not well-nourished and not able to absorb that information, then it is all pointless.”

Starting from scratch

So with slight variations and different degrees of transformation, depending on the school, it’s out with the potato smileys, French fries, ice cream, sodas and flavored milks. Banned are all desserts, corn dogs, chicken nuggets and even burgers—because Chef Smith thinks USDA school beef is “gross” and too frequently subject to health recalls.

What’s in is a back-to-basics, balanced meal made “from scratch” using local produce as much as possible.

“We used to have Sponge Bob milkshakes and sherbet, but now the school food tastes better and we get healthy things like teriyaki rice bowls and fruit,” says 11-year-old Gabby White, who goes to Branciforte Middle School in Santa Cruz and likes the changes.

Cooking school food “from scratch” is one way to eliminate potentially harmful preservatives, dyes and binders that pre-packaged foods may contain. But it goes beyond health benefits.

“Pre-packaged food leads us to have no attachment to where the food came from, to who made it or who’s serving it, so we are empowering our local workforce by using fresh, local foods and reducing our carbon footprint too,” said Smith—who was one of two Califor-

Gardens as classrooms

Spread out on 10 acres alongside Carmel Middle School is a paradise of flowers, fruit trees and lush organic vegetable gardens called the Hilton Bialek Habitat. Begun in 1995 as an outdoor science classroom and named for a beloved member of the board of the Carmel Unified School District, it has blossomed into a multi-purpose oasis where students learn everything from gardening to ancient history and ecoliteracy.

On a recent sunny morning, garden director Tanja Roos was teaching a group of students about the kinds of plants grown in Roman times and foods the gladiators might have eaten, like the dates topped with goat cheese and honey that she handed out for the kids to sample.

“When they study Mesopotamia, we dig irrigation channels and plant fava beans,” she said. “And when they study ancient Egypt we make papyrus. It makes history come alive!”

Next period, the sixth-grade ecoliteracy class straggled in. Ecoliteracy is a required daily six-week class designed to teach kids “where we are in 2011 on planet earth.” They learn how sustainability is reflected in everyday lifestyle choices like food, clothing, shelter, energy use and transportation.

And they learn the FLOSS principle. No, it is not a way to get bits of celery out of the teeth, but simple guidelines for making healthy food choices. FLOSS, as any sixth grader could tell you, is an acronym for Fresh, Local, Organic, Seasonal and Sustainable.

New this fall is a $1.1 million LEED-certified cooking classroom in the garden. It is the first “green” public school building in Monterey County and was built entirely with recycled or renewable materials. It features alternative energy sources, rainwater catchment for irrigation and a living roof planted with wildflowers and native grasses. The living roof is a good insulator, helping keep the classroom warm in the winter and cool on hot days. It also provides a habitat for the beneficial bees and other pollinators needed to keep the garden growing.

www.ediblemontereybay.com 25

Tanja Roos teaching ecoliteracy at Carmel Middle School. Opposite: Jamie Smith, food services director for Santa Cruz City Schools.

Photo by Deborah Luhrman

Chicken Pot Pie Casserole

Courtesy of Myra Goodman and Sarah LaCasse, Earthbound Farm serves 6-8

Filling

1 pound chicken, boneless breast or thigh

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 cup chopped onion

1/2 cup chopped carrot

1/2 cup chopped celery

2 cups peeled, diced potatoes (1 large or 2 small)

1 tablespoon chopped garlic

1/2 cup frozen or fresh corn kernels

1/2 cup frozen or fresh peas

1/2 cup chicken stock

4 tablespoons butter

1/4 cup all-purpose flour

1 1/4 cup milk

2 teaspoons salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon dry thyme

Heat oil in a large skillet. Sauté onion, carrot, celery and potatoes over medium heat for 10 minutes, stirring to prevent sticking. Add garlic and continue cooking for 5 more minutes. Add chicken, corn, peas and stock. Reduce heat to medium-low and cook 10 minutes, or until potatoes and carrots are soft. While the chicken and vegetables cook, in a separate pan melt butter and then add flour. Whisk to combine and then add milk, salt and pepper. Cook over medium heat until mixture thickens. Add the white sauce to chicken-vegetable mixture and stir well to combine. Remove from heat and pour into an 8x8” pan.

Pre-heat oven to 375 degrees.

Biscuit Topping:

1½ cups all-purpose flour

2 teaspoons sugar

1 3/4 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon baking soda

4 tablespoons cold butter, cut into small pieces

½ cup plus 2 tablespoons whole milk

In a mixing bowl combine flour, sugar, baking powder, salt and baking soda. Stir together well. Cut in butter using two knives or low speed hand mixer. When the butter is incorporated into dry ingredients, add milk and stir until dough is just combined. Drop by tablespoons on top of pot pie mixture and bake for 35 minutes until golden brown.

Please go to the EMB website to find two more recipes shared by Goodman and LaCasse: Roasted Beet and Arugula Salad with Walnuts and Feta Cheese, and Turkey Meatballs with Linguini.

nia school chefs invited to Washington, D.C., this summer to take part in the USDA’s Produce University, designed to get more fruits and vegetables into the nation’s cafeterias.

Stealth health School lunches that lucky kids are enjoying this fall include things like pasta Bolognese made with ground turkey, pork chile verde, roast turkey sandwiches on whole-wheat buns, fish tacos, roasted yams, salad bars, veggie burgers and everybody’s favorite—pizza!

Yes, pizza can be a healthy option. When made with a wholewheat crust, it becomes an edible plate for any combination of fresh toppings and kids almost always like it.

“The most important thing to consider is: Will kids eat it?” said Ford, of Point Pinos Grill. His catering company, Aqua Terra Culinary, provides school meals for Stevenson School in Carmel, Chartwell School in Seaside, and is in talks to expand into Pacific Grove schools. Ford blends fresh vegetables into his pizza sauce, makes a whole-wheat crust from scratch and uses low-fat, low-sodium mozzarella—so it’s healthy but the kids don’t notice.

His mac and cheese with turkey sausage is another favorite and all meals are served with fresh fruits and vegetables. He says kids often try foods like tomatoes at school that they refuse to eat at home, because they see friends eating them.

“It’s not a hard sell. I’m not the food police and I don’t do school lunches because it is the foundation of our business, but as a way to give back to the community, to make sure kids are eating well and learning to appreciate healthy foods,” he added.

Organic and local

Watching kids turn into adventurous eaters is one of the most rewarding parts of the job for Myra Goodman, cofounder of Earthbound Farm, whose Carmel Valley–based Farm Stand serves up 100% organic lunches to students at nearby All Saints Day School.

26 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Myra Goodman, co-founder of Earthbound Farm and Sarah LaCasse, Earthbound’s executive chef.

Photograph courtesy of Earthbound Farm

“What’s exciting is that there are now lots of foods in the cafeteria that kids never really embraced before, like beets in the salad bar or roasted yams and soups that the kids are really liking. So there’s kind of a positive peer pressure to try new things and be an adventurous eater,” she said.

While Goodman hadn’t originally planned to be a school lunch provider, she was convinced by her sister—who has a daughter at the school—and by Earthbound Executive Chef LaCasse. In addition to helping develop healthful young eaters, she sees it as a way of keeping kitchen staff fully employed year-round, even during the slow winter season.

Each day vegetarian and nonvegetarian meals are offered, the most popular being linguini with turkey meatballs, quesadillas and chicken potpies. (See recipe box opposite and EMB website.) For breakfast, they serve a healthy bar made with carrots and sweetened with applesauce.

Earthbound’s Farm Stand also hosts field trips for local schools with the goal of waking up the taste buds of young eaters. “We want to create those childhood memories of that sweet melon, that juicy peach and that sweet pea and fresh carrot,” said Goodman. “When kids taste delicious produce that is truly fresh at its peak of flavor— which is often seasonal and local and organic—then they are going to realize that they love fruits and vegetables.”

Farm to School

While not all schools are so fortunate as to be neighbors with Earthbound Farm, there’s a good chance that wholesome produce is growing within a few miles of every school in the Monterey Bay area.

“We’re blessed with all these fruits and vegetables that we can get locally,” said Irene Vargas, director of food services for the Alisal Union School District in Salinas—a large district that provides nearly 19,000 free breakfasts, lunches and snacks to children every day with funding from the USDA.

Because it is a poverty district, Alisal has been able to pioneer many government programs designed to get more fresh produce into the schools. In the early 1990s it was one of the first districts in the country to install salad bars and, starting in 2003, won a USDA grant to implement the “eat five a day” campaign promoting fruits and vegetables.

You might think that kids in the Salinas Valley are born with a love for fresh produce, but it is not so. “Even kids whose parents are farm workers sometimes don’t eat fresh produce at home,” said Vargas. “Often farm worker parents are very aware of all the pesticides used in the fields and don’t want their children exposed to them.”

The Farm to School program, run by CAFF (Community Alliance with Family Farmers) in our area, was designed to tackle those problems. Started in Watsonville, it has now expanded to 350 classrooms throughout California, including school districts in Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Benito counties—where almost all third-grade classes participate. Since receiving funding from the Healthy Kids Act last year, requests for assistance from more districts are flooding in.

Farm to School has a two-pronged approach: It offers technical assistance on getting local produce into cafeterias, while at the same time working to get kids excited about eating more fruits and vegetables, and where their food comes from.

www.ediblemontereybay.com 27

Food What?!

Sitting at a picnic table under a big, shady walnut tree up at the UC Santa Cruz farm, students from area high schools were getting a lesson in how to write a resume. Under the category of experience, they were instructed to write “Successfully completed youth empowerment internship”—strong words aimed directly at potential employers.

Empowering young people through growing and cooking their own food is the goal of the 5-year-old Food What?! program headed by teacher Doron Comerchero. Each spring and fall, 52 teenagers are selected to take part in the 12-week internship, which is a youth arm of Life Lab, the Santa Cruz–based science and environmental educational organization. The students plant and tend to organic vegetable gardens and learn to cook healthy lunches with the produce, including dishes like quesadillas stuffed with kale, broccoli and red peppers, spanakopita, pasta with homemade pesto, whole-wheat pizza topped with green vegetables, and even vegetable sushi.

They also participate in practical skills workshops in communications, public speaking, resume writing and financial literacy. On completion of the internship they are paid $175, which according to Comerchero is an important motivational factor.

“My mom works late and I got tired of eating Ramen noodles for dinner,” said 16-year-old Tyler Espinosa. “So I joined Food What?! to learn how to cook, but I found out that I really like plants and now I’ve got a job at ProBuild nursery.” Other teens said their weekly Food What?! internship lunch was the only time they ate vegetables at all.

During the summer months, the best interns are hired to run the farm and sell their fresh, organic harvest to needy families at heavily discounted prices—all with the goal of youth empowerment and getting more healthy foods onto the tables of more Santa Cruz families.

The Santa Cruz District, for example, has some direct contracts with apple growers Gene Silva and Gizdich Farms in Watsonville. It also buys through ALBA (Agriculture and Land Based Training Association), which operates a type of cooperative so that organic produce from small local farmers such as Happy Boy Farms and Swanton Berry Farm can be purchased by large institutions like the school district.

But Farm to School is probably best known for its efforts in the classroom. The Know Your Farmer program brings farmers into the school and organizes class field trips to local farms, while Harvest of the Month provides each classroom with a box of fresh produce and a lesson plan to help teachers introduce each food to the students. Thirty-two different products are rotated through the Harvest of the Month program—from rutabagas to kiwis.

Exposing children to fresh fruits and vegetables and letting them pick them at a farm or, better yet, grow produce themselves, is one of the best ways to teach healthy eating. That is why school gardens are sprouting up throughout the area, along with garden-based programs for teaching about ecology. (See sidebars.)

New rules

The new USDA guidelines for school food being implemented this fall are part of the Healthy Kids Act signed by President Obama last December. They bring menus more in line with government dietary recommendations. They also reflect the switch from the old carbheavy food pyramid approach to the new plate symbol—which shows that half of a meal should be made up of fresh fruits and vegetables.

The new standards provide districts with an additional six cents per subsidized lunch to accomplish the following:

•Limit the amount of starchy vegetables such as potatoes, corn and peas to one cup a week.

•Increase the amount and variety of fresh fruits and vegetables.

•Increase the use of whole grains.

•Require unflavored milk to be 1% fat and flavored milk to be fat-free.

•Limit salt and trans fats.

Some lawmakers in Washington—backed by the potato, processed food and dairy lobbies—have blasted the new guidelines as another example of big government meddling in the personal lives of its citizens. They are also trying to slash USDA funding for the upcoming year, which could put some programs in jeopardy. But administration officials say the national epidemic of childhood obesity makes healthy improvements absolutely necessary.

Salinas Valley produce growers have a lot to gain from the new guidelines and are squaring off for an ag battle. Led by Central Coast Congressman Sam Farr, they invited the USDA’s top nutrition official to visit our area on August 30. As EMB went to press in August, Kevin Concannon, USDA Under Secretary for Food, Nutrition and Consumer Services, was scheduled to tour local fields, a packing plant and a school cafeteria to see the new guidelines in action from field to fork. He was also set to take part in a round table where local growers and school lunch providers offered their advice on how to push back against critics in Washington.

28 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Food What?! interns tend their crops on the UC Santa Cruz farm

Photo by Deborah Luhrman

Fighting fast food

Parents have generally reacted favorably to these improvements in school food, but it is still hard to gain acceptance from kids. They are accustomed to fast food and when given the chance will go off campus to buy it instead of eating in the cafeteria. In Salinas, for example, vendors surround the schools before and after class, selling Cheetos, Red Bull and ice cream. In Santa Cruz, fast food restaurants or convenience stores are often walking distance from campus and earn up to 40% of their revenues from students.

Last year on average only about 150 students out of 1,000 ate in the cafeterias at Santa Cruz high schools. The others went off campus. Short of closing the campus cafeterias, the district is embarking on a marketing campaign with a name change, hoping to make cafeterias fun and school food “cool.” Cafeterias are being re-named the Surf City Café and taste tests will be conducted to introduce kids to the upgraded food.

While it is hard to innovate in a time of school budget cuts, the district will also experiment with offering free, healthy breakfasts in the classroom for every student at Gault Elementary School—something other schools like those in the Pajaro Valley have been trying for some time.

“The kitchen is competing with the classroom for budget dollars, but we’re going to persevere,” said Santa Cruz School Board President Cynthia Hawthorne, who has been the driving force behind the transformation in the city’s school cafeteria food.

“Serving breakfast is the most effective way to make sure every child, including those who may not have had much supper the night before at home, is prepared for academic success,” she added.

To help educate parents and the community at large, Santa Cruz is joining together with districts throughout the area to sponsor the School Food Festival on Saturday, October 8, from 9am to noon at the Aptos Farmers Market at Cabrillo College to showcase what they have achieved.

As Hawthorne, whose youngest daughter just graduated from Santa Cruz High, put it: “We have a moral obligation to do this for our children. Children have a right to healthy food and when communities are falling short we need to come together to make sure the rights of children are respected.”

www.ediblemontereybay.com 29

Watermelon is a hit at Santa Cruz’s Branciforte Middle School

Photo by Richard Green

ON THE FARM A FARM OF THEIR OWN

ALBA incubator brings pride and produce to the community

By Renee Brincks Photograph by Richard Green

ness plans, prepare soil, set up irrigation systems, control pests and market her crops.

Despite its challenges, she finds her new career fulfilling.

“It gives me something that is mine,” Bravo said. “I grew these things. I feel really proud.”

ALBA first helped aspiring farmers 10 years ago, though its roots reach back another three decades. The organization’s predecessors launched local programs supporting agricultural workers and beginning farmers in the 1970s. Today, ALBA’s major efforts include offering courses for growers-to-be, matching select graduates with ground and managing a produce distribution outlet called ALBA Organics. Longtime executive director Brett Melone left ALBA this summer, but organization representatives say the mission remains the same: Advance economic viability, social equity and ecological land management among limited-resource and aspiring farmers.

Interested individuals start by applying and interviewing for spots in ALBA’s farmer education program. Many participants are Latino, and about one-third are women. Nearly three-quarters of the students are current or former farm workers.

“We seek low-income people with agricultural experience and entrepreneurial drive,” said Gary Peterson, ALBA’s communications and development director. “We’re able to enroll about 30 adult learners each year, typically ranging from 18 to 50 years of age.”

ALBA staff members and industry experts lead classes and field experiences, sharing the practical information students need to seek employment or build their own farming operations. Graduates are invited to create a business plan and compete for a spot in the ALBA incubator. Approximately eight participants are accepted annually; each leases a half-acre parcel for a fraction of the regular market rate and pays a per-use fee for shared machinery and irrigation equipment. Thriving farmers can rent additional acres for up to seven years, topping out at around 10 acres at ALBA’s full commercial rates. At that point, program administrators help growers find their own land in the region.

The goal is to provide a low-risk environment that prepares students for long-term success, explained Peterson.

“That lease rate increases each year if people continue in the farm incubator program,” he said. “Beginning farmers get a fairly real sense of the resources and routines and commitment it takes to run a successful small farm business.”

The first time Maria Olga Bravo watched growers tending land leased from the Agriculture and Land-Based Training Association (ALBA), she was ready to sign up!

“I fell in love,” said Bravo, who grew up picking strawberries with her father. “It was the family atmosphere...small farmers had their acre or two, and they had their wife or their husband or their uncle there, and they were all picking the produce.”

Five years after that initial visit, the 52-year-old mother of four grows vegetables south of Watsonville at ALBA’s 195-acre Triple M Ranch. She earned the chance to sow there after completing a sixmonth, 150-hour curriculum and qualifying for ALBA’s small farm incubator. Bravo, who worked a desk job for 20 years before a company shutdown left her unemployed, now knows how to write busi-

“To be successful in this type of work, you have to be there every single day and be able to work hard,” said 21-year-old Octavio Garcia, who farms nearly four acres at ALBA’s Salinas property. He believes he would not be farming without the support of ALBA’s instructors and field managers.

“They really help us. They try to give us as much information as they can. They are patient with us.” Garcia said. “It’s really hard to become a farmer outside of ALBA because everything is really expensive, and ALBA makes it cheaper and easier for us.”

“It typically takes three to four years before someone leaves their day job to be a full-time farmer,” Peterson said. “Five years after leaving our farm incubator, 80% of those farmers are still in business elsewhere.”

30 edible monterey bayfall 2011

Maria Bravo beams while standing in her field.

ALBA statistics show that incubator participants net an average $10,000 of income during their first three years, $33,000 in years four through six and $50,000 or more once they reach commercial farming status.

“That’s a trajectory that is obviously the very basis of our program: to help create wealth in low-income communities in our region by leveraging vocational skills and entrepreneurial drive with education and access to resources,” Peterson said.