“What brings us to the kitchen is hunger, hunger for food, hunger to feed others,” writes Edward Espe Brown in his classic, The Complete Tassajara Cookbook. “What brings us to the kitchen is love, conviviality, connection—we’re finding a place at the table of life.”

Some people see food as nothing more than fuel. But for many of us, it is much more than that. It is a life-enriching thing to “offer our effort," as Brown puts it, to create delicious food.

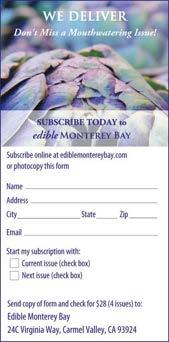

In this issue of Edible Monterey Bay—as we did with our first two—we bring you the stories of many people who passionately offer their efforts in pursuit of bringing our local area truly great food.

You’ll read about a lawyer named Cynthia Sandberg who left her practice to devote herself to growing tomatoes in the Santa Cruz Mountains and now supplies superb, biodynamic produce of all kinds to David Kinch’s two-Michelin-star restaurant, Manresa.

We’ll introduce you to San Benito County grassfed beef ranchers who are reclaiming animal husbandry done in a more intentionally healthful and humane way.

You’ll learn about the inspiring dedication to excellence of Chef Cal Stamenov and Winemaker Dean De Korth at Bernardus in Carmel Valley.

You’ll also read about cooking classes all over the Bay, where local masters provide opportunities to learn from them in their own kitchens.

We’ll provide tales of a sustainable sushi venture, our Bay’s often-forgotten squid, the coffee savants at Verve Coffee Roasters, and a glimpse of the artichoke’s colorful local history.

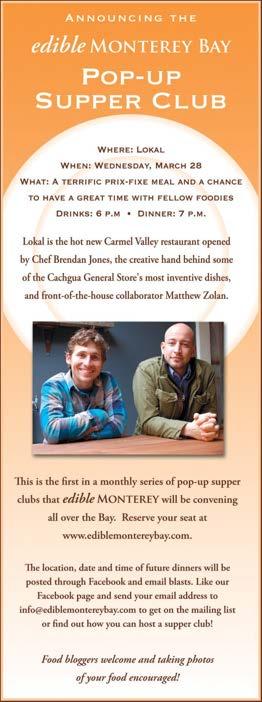

You’ll find an announcement for the first installment of Edible Monterey Bay’s new Popup Supper Club series, at the much-awaited new restaurant opened by Chef Brendan Jones— one of the creative hands behind the Cachagua General Store—and front-of-the-house partner Matthew Zolan. Reserve your seat soon by going to our website!

Finally, you’ll even learn about the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center itself and the quiet influence it’s had on our current passion for all vegetables fresh, sustainable, seasonal and delicious.

As Brown says, “Cooking is not just working on food, but working on yourself and working on other people.”

We hope this issue inspires you to connect with great flavors, conscious choices and, perhaps best of all, with the many people in our local neighborhoods who share our love and appreciation for the effort. We personally admire and enjoy great effort. But delicious, transporting food need not be expensive or fancy—just fresh, wholesome and prepared with passion and love.

Enjoy!

PUBLISHER AND EDITOR

Sarah Wood Sarah@ediblemonter ybay.com 831.238.1217

CO-PUBLISHER AND ASSOCIATE EDITOR Rob Fisher

COPY EDITOR Doug Adrianson

DESIGNER Melissa Petersen

WEB DESIGNER Mary Ogle AD DESIGNER Jean Roth

CONTRIBUTORS

Jordan Champagne • Jamie Collins

Cameron Cox • John Cox • Susan Ditz

Bambi Edlund • Kodiak Greenwood

Mike Hale • Ted Holladay • Geneva Liimatta Elizabeth Limbach • Deborah Luhrman

Jorge Novoa • Keana Parker • Pete Rerig

Darrell Robinson • Patrick Tregenza

Carole Topalian • Amber Turpin Christina Waters • Lisa Crawford Watson

ADVERTISING SALES

Shelby Lambert • 831.238.7101

Shelby@ediblemontereybay.com Kate Robbins • 831.588.4577 Kate@ediblemontereybay.com

INTERNS

Kalia Feldman-Klein • Katie Reeves

CONTACT US:

Edible Monterey Bay 24C Virginia Way, Carmel Valley, CA 93924 www.ediblemontereybay.com 831.238.1217 info@ediblemontereybay.com

Edible Monterey Bay is published quarterly. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used without written permission of the publisher. Subscriptions are $28 per year at www.ediblemontereybay.com. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our apologies and notify us. Thank you.

As sun streams in the huge arched windows of Geisha Sushi, Chef David Graham beams.

“Just look at how beautiful this Arctic char is,” says Graham, showing off the plump, silky, 14-inch cuts.

“It’s sustainably farm raised in ideal conditions—no pollutants—and every bit as delicious as its cousin, the salmon.”

Moving down the row of fresh-as-can-be seafood, he holds up a slab of Tombo Ahi, a species of Pacific Albacore that isn’t suffering the same fate as its overly fished and endangered relative, the bluefin tuna. “It has a buttery taste, very mild and tender,” Graham says.

As delighted as Graham is to display the daily offerings at his Capitola restaurant, he’s even more proud of its mission: to serve only healthy, sustainable, eco-conscious fish.

Gone are the farm-raised freshwater eels for unagi. Instead, he serves up o-nagi, which is catfish prepared in the same sweet, marinated barbecue style. Also absent is all manner of farmed salmon, imported shrimp, octopus and sea urchin.

Opened last summer, Geisha Sushi is one of only a half-dozen or so sushi bars in the country that eschews any seafood not earthfriendly, and it is the first in the area.

“At first, we were nervous about bucking the status quo,” says Graham, who opened Geisha with owners Annop Hongwathanachai and Anchalee Thanachai. “It was a scary proposition.”

But as cutting-edge as Geisha’s operating premise is, it’s been met not with wariness but with overwhelming success.

“Given a choice, people more often than not do the right thing,” says the philosophical Graham. “Our customers have shown their willingness to experiment, to step out of their comfort zone and try new things, and that’s been a key to building our reputation.”

While a very small number of people have walked out of the restaurant upon discovering that their favorites aren’t on the menu, the vast majority, Graham says, have embraced the restaurant’s approach and allowed him to guide them to new and interesting choices.

Graham takes his cues from the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program, the ultimate resource for enjoying the gifts of the sea responsibly. “There are so many factors to consider when choosing seafood, and the Aquarium’s Seafood Watch boils it down so nicely.”

Among the questions the Aquarium asks before giving its seal of sustainability are: Is the bycatch reeled in during fishing hurting the ecosystem? Are farmed fish being raised in terrible conditions, in overcrowded pens with a diet of high-protein food? Is the water on these farms being pumped full of antibiotics? Are pollutants being allowed to enter open waters? The list goes on and on.

But Graham isn’t catering to the fish alone.

“When you buy and prepare sustainable seafood, you’re not only helping struggling fish populations and the ocean, you’re also getting a superior product—fresher, healthier and just plain better.”

And when a certain roll or recipe calls for produce, customers can also be assured of first-rate quality: organic fruits and veggies culled from local markets and farms. Geisha’s menu in fact has an extensive list of vegetarian entries, and most of those dishes are vegan.

Should you make a foray to Geisha, be sure and try the lean walu (also known as butterfish, an apt moniker for its utterly delicious taste); the suzuki, a nice, mild species of Japanese sea bass; and the Thailander roll, a delectable combination of o-nagi, prawn tempura, peanut butter and a hint of spice. Then finish off your feast with a bowl of coconut ice cream crafted with a recipe that’s been passed down through three generations of one of the owners’ families.

If you love what you order, you’ll make Graham a contented man.

“There’s a whole universe of choices in sushi using sustainable, ecologically sound seafood,” says Graham. “And when a customer at the restaurant exclaims ‘that’s sushi and it’s sustainable?’ we smile because we made someone happy and did a little more to help the environment. And that’s pretty exciting and very gratifying.”

Geisha Sushi • 200 Monterey Ave., Capitola • 831.464.3328

Seafood Watch: www.montereybayaquarium.org/cr/seafoodwatch.aspx

fish: Chef David Graham is one of just a half dozen or so sustainable sushi chefs in the nation.

By Amber Turpin

By Amber Turpin

“We really just want to be a homesteader’s convenience store,” says Mountain Feed and Farm Supply owner Jorah Roussopoulos. But instead of a six-pack of Budweiser and some Lay’s potato chips, this colorful “convenience store” offers books and kits on how to brew your own beer and seed potatoes for growing your own crop.

In fact, if a do-it-yourselfer’s convenience store sounds a bit like an oxymoron, the truth is that Mountain Feed is so much more than that: a veritable sustainable-living country store, ready to outfit anyone from any walk of life who wants to live a little more in harmony with the planet—and find stellar customer service while they’re at it.

Roussopoulos and his wife, Andi Rubalcaba, first opened the store at the “bend in Ben Lomond” in September 2004 as a destination for mountain folk to get chicken feed and fuel from a solarpowered biodiesel filling station. But the ambition of the former high school sweethearts, who worked nights to gradually build up their inventory—he as a bartender and she as a beautician—has always been palpable when you walk in the door.

Today, Mountain Feed employs more than a dozen full-time staffers and each of several departments offers a specialist who is truly expert at helping customers find what they’re looking for and can offer tips and advice on any given project.

The business has also fanned out into five different buildings and about an acre across the street that houses “homesteading infrastructure,” also known as “the big stuff”—soil, compost, water tanks and the like.

In the main buildings, merchandise is arranged progressively, from the basics to the obscure.

“Planting seeds to canning jams, our goal is to be able to take people full cycle from production to preservation,” Roussopoulos says.

That means you can walk in and easily find the standards that most feed stores provide: pet products, livestock feed, seed propagation supplies, soil amendments and anything for the home garden.

But wandering in deeper, you’ll discover what makes Mountain Feed so unique.

The Homesteading Housewares department, for example, is packed full to the gills with everything “dedicated to the gardener’s kitchen,” Roussopoulos says. The space is organized by theme, from soda making to bread baking to fermenting to pickling to canning to dehydrating to curing. All of the bakeware is American made, and even professional chefs and commercial food producers shop there due to the hard-to-find selection in stock.

Local food artisans are also well represented. “If it’s edible in here, it’s local,” Roussopoulos says.

Next door, in the space housing most of the seed and garden products, you can find an array of beekeeping supplies, chicken care items and wild bird feeding supplies. And around back in the “Edible Nursery,” there is always a wide array of seasonally appropriate items, currently consisting of bare fruit trees, spring veggie starts and even hops, horseradish, currant and gooseberry trees, not to mention the vibrant collection of ceramic glazed pots and locally made, artistic repurposed tables, sink stations and cooler cubbies for sale.

Sadly, Mountain Feed’s source for local recycled biodiesel dried up, so the filling station is gone.

But all in all, the store has been a beloved boon to its immediate community and a draw for new customers from far corners of the foodshed who are anything but a convenient distance away.

So what’s ahead?

Mountain Feed is “stocked by popular demand,” says Roussopoulos. “People tell us what they want, and we listen.”

By Mike Hale

By Mike Hale

Once Monterey stopped canning sardines in the 1960s, it quickly earned another moniker: “Calamari Capital of the World.” Yet, today, as part of a fast-food nation that prefers fish sticks to squid tubes, we seem to have lost our connection with the 10-armed cephalopod the rest of the world craves.

Bright lights will again illuminate our bay at night when the season opens in April, bringing local boats out in force to lure market squid from the depths, much as they did when the fishery began in the 1860s. Squid is still the second largest (counted in tons) fishery in California, but the majority of the commercial catch is exported, primarily to Asia.

Even some of those boxes of squid stamped “Monterey Bay Calamari” contain a dirty little secret: The squid was caught here, of course, but shipped to China for cleaning, processing and freezing, before being loaded on a container ship for the long trip back home.

Despite that large carbon footprint—along with a few concerns about bycatch and habitat damage—market squid is considered a “Good Alternative” by the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program, which rates the sustainability of fish by where and how it is caught.

Buying directly from a local source is the most sustainable purchasing decision, and leads to a fresher, better-tasting squid.

Over-processing is the worst thing one can do to fresh squid, according to Kevin Phillips, managing partner at Abalonetti Bar & Grill on Fisherman’s Wharf, known for 60 years as the place for calamari.

Phillips buys only fresh local squid and hires a full-time employee to clean 1,000 pounds of it a week in a room behind the restaurant.

“It’s the freshest squid available anywhere, and the flavor [of squid shipped to China and back] doesn’t compare,” says Phillips, who adds imported squid is rinsed too thoroughly and is often bleached, so the delicate seafood loses its natural brininess. “It’s sad to see much of our local squid shipped away.”

Only four Monterey Bay processing plants remain as part of the region’s 150-year-old market squid fishery—first run, ironically, by Chinese fishermen.

Sal Tringali, a third-generation squid processor at Salinas-based Monterey Fish Co., finds it distressing to see most locals shun the inexpensive and healthful seafood.

“People today don’t know what they’re missing,” says Tringali, wistful for the days when the town celebrated squid, particularly at the now-defunct Monterey Squid Festival.

From its commercial store on Municipal Wharf No. 2, Monterey Fish Co. sells whole market squid for about $1 a pound, the same price seen in the 1970s, Tringali says.

Cooking squid requires proper timing. Phillips adheres to the adage of cooking it very quickly (no more than 2 minutes) at high heat or else for an hour or more in a slow braise. “Anything in between, and it’s tough,” he says.

At the annual Gilroy Garlic Festival, Gourmet Alley pyro-chefs cook squid Sicilian style, with flames leaping from giant pans.

Event organizers have released a less-incendiary recipe that calls for 3 pounds of squid, cleaned and cut into rings (tentacles reserved).

In a large skillet, heat 1/3 cup of olive oil at high heat. Add calamari and 1 tablespoon crushed garlic and sauté for 2 minutes. Lower heat, add 1/4 cup white sherry and squeeze the juice of half a lemon into the pan, dropping in the rind. Sprinkle some basil, oregano and red pepper flakes into the pan, and stir in your favorite marinara. Bring up to desired temperature and serve.

“The Italian community eats squid all the time,” says Tringali. “We call it poor man’s abalone. It’s very important to us, and we all grew up eating it. It’s comfort food.”

Moonlighting: Squid are caught at night; the fishing boats in photo above were at work off of the Pacific Grove shoreline. Drawing of market squid by Bambi Edlund.

by Keana Parker

by Keana Parker

Patricia Poritzky is sitting by the curb in her hybrid, planning tonight’s menu and waiting to pick up the kids in her carpool, one of the many ways she shares and conserves resources throughout her day. Another is the 2,000-square-foot professional kitchen she timeshares. By day, another business cooks there; at night, Poritzky transforms it into a cooking school.

“Let’s Cook Santa Cruz,” which opened with sold-out classes in January, is where she and guest chefs teach the community how to cook SOLE food—sustainable, organic, local and ethical grub.

“SOLE food is part of a movement to help change the way people eat and access their food,” Poritzsky says, adding that if her students “learn one thing about being more environmentally friendly and buy one thing that wasn’t trucked across the States, I’m grateful.”

Poritzky is just one of a number of area cooks and chefs who have begun to offer their expertise to local residents who are increasingly eager to hone their chops for cooking our region’s fresh, healthy local food—be it from their delivery of fresh fish from Local Catch Monterey Bay, their CSA box or finds from their neighborhood market.

Some of the very newest of these classes will come from Dory Ford’s Point Pinos Grill in Pacific Grove, which will soon offer cooking classes for kids; Santa Cruz’s Front Street Kitchen, a community commercial kitchen that will run a variety of culinary classes; and Hollister’s Pasture Chick Ranch, which will teach cheesemaking.

At the Hyatt Carmel Highlands’ Pacific’s Edge restaurant, Executive Chef Matt Bolton is launching in March a “Meet the Farmer” lunch series to offer expertise in sourcing local ingredients and preparing them at home.

“More and more,” says Bolton, “people want to know where their food is coming from, whether it’s organic, heirloom or foraged; how green it is; and what kind of footprint they’re leaving on the earth. I find this a really good way to bring people closer to local food sources, the same fresh products I use in our restaurant.”

Highly trained chefs at other hotel restaurants are also sharing their secrets: at Aubergine in Carmel, Chef de Cuisine Justin Cogley and Executive Pastry Chef Ron Mendoza offer a “Sweet and Savory” series in their renowned kitchen, and Carmel Valley Ranch has set up a special “Adventure Kitchen” for courses with Executive Chef Tim Wood.

The Ranch offers two types of classes: a three-level series for students who want to refine their basic techniques with a pro, and activity-related classes that, for example, allow students to tour the Ranch’s organic garden and then learn how to cook its progeny.

Some local offerings have themes, such as Rio Grill’s “Flavor Education Series,” Cantinetta Luca’s “Secrets of Pizza and Pasta” and Montrio Bistro’s “Artisan Series,” which features local food artisans.

“My flavor series,” says Rio’s chef, Cy Yontz, “expresses what Rio Grill is and how I cook, with bold, earthy flavors. It also is a way to get the community together, to meet friends and have a great time at Rio Grill.”

Monterey’s Stone Creek Kitchen, opened last year, makes things especially easy by offering an on-site classroom kitchen and selling cooking equipment and pantry items that can be used to make their recipes.

“Our goal, when you come to our kitchen, is to inspire you to try new things and to have more fun in your kitchen,” says Co-proprietor Linda Hanger.

Other relatively new classrooms include Santa Cruz’s el Salchichero, offering butchery and charcuterie classes, Happy Girl Kitchen Co.’s Pacific Grove Organic Café, delivering preserving workshops, and Love Apple Farms’ beautiful new indoor and outdoor classrooms, home to a number of classes. (See related story, p. 40.)

If you’re willing to travel, there is also the magical Tassajara Zen Mountain Center (see p. 28) and if you get really serious, more formal training awaits you at schools like Bauman College and Monterey Peninsula College.

For a guide to all of these classes, go to www.ediblemontereybay.com, and find “Culinary Course Catalog” under the “Local Food Guides” tab.

Back to school: Patricia Poritzky at Let’s Cook Santa Cruz.

While the “zero energy” status won’t have any particular tax benefits, “it does have a certain amount of marketing value,” Pamela says. It’s also personally satisfying for the couple, whose vineyard and home have been solar-powered from the beginning.

The Storrs’ romance began in winemaking classes at UC Davis, and two decades later, they have raised three children, countless animals, organic gardens and 20 vintages of award-winning handmade wines. Always focused on the Santa Cruz Mountain appellation, they purchased 50 acres in Pleasant Valley 10 years ago, where an heirloom apple orchard awaited restoration and hillsides were prime for grape planting.

On the verge of organic certification, the vineyard boasts 10 acres of pinot noir and chardonnay, growing on land invigorated by stateof-the-art sustainable techniques. These hands-on winemakers have worked tirelessly to plant native wildflowers, create owl nests and raptor perches, and most recently, to introduce a quartet of miniature “baby doll” sheep to graze between the vines.

“They’re a heritage breed,” Pamela explains. “They’re much smaller than the typical breed—the little sheep fit between the rows,” she says, laughing. “Think of them as the organic version of weed control.” She reckons the small breed will work very well in the winter because they won’t compact the moist soil. “In the summer they’ll have to graze elsewhere on the property,” she says, “because they actually will try to eat the tender new grape leaves.”

The vibrant ecology of the vineyard owes a lot to Wild Farm Alliance, which promotes agricultural practices that help restore and protect wild nature, and the integration of farms into their wild settings.

Walking the winery trails tucked away behind Corralitos, it’s easy to feel that you’ve stumbled upon an environmental demo farm. Hidden Springs Ranch, home to Storrs Winery, sits in a panoramic hollow, generously populated with deer, hawks, owls, bats and beneficial insects. From the start, Pamela Bianchini-Storrs and Steve Storrs wanted to encourage the helpful animals, as well as native plants and pollinators such as bees, butterflies and hummingbirds. Applying principles of sustainable and organic growing to their vineyard practice was a reflection of their winemaking philosophy—to step back and let natural processes do what they do best.

This innovative alliance between agriculture and nature is already an estate vineyard, and by summer’s end, the Storrs, who have long offered a downtown Santa Cruz tasting room, will open their vineyard for the first time for tastings in a newly constructed “zero energy,” solar-powered winery and offer walking tours through the surrounding acres.

The aim is for the new building to produce as much energy as it uses, so insulation is key to the design. For the walls, “straw bales weren’t efficient enough, and so we’re using honeycombed foam, filled with expanding foam made from soybeans,” says Pamela. “The roof will be extraordinary, too, made of highly insulative concrete panels.”

“Thanks to a grant, they’ve provided us with native plants, and local high school students came to help with planting.” The idea behind that was to create cover plantings to enhance the habitat and provide food for wildlife. All of this micro-management of their incredibly diverse and fertile acreage “keeps life interesting,” Pamela admits. “It’s so much more engaging than just doing one thing every day. Besides, the vineyard never waits.”

Racks of solar panels face the sun at the top of one far slope of the vineyards, and native fescues have been planted to retain groundwater and valuable topsoil. “We are determined to keep all of the water on our property.” Pamela chuckles. “Our first wet winter, we watched a lot of the vineyard topsoil float downhill.”

And now that the winery building foundation has been poured and the structure itself will soon be up, the winemakers have plans to send visitors on self-guided walking tours, aided by well-placed informational signs.

The Storrs’ move to lure visitors out to their vineyard runs counter to a recent trend that has been opening legions of in-town tasting rooms from Santa Cruz’s Swift Street Courtyard to Carmel Valley Village.

“A lot of city people just don’t get out into the country very much,” Pamela says. We’re interested in educating people about all of these natural cycles.”

The future of winemaking, she believes, is a fully hands-on, natural and highly sustainable enterprise. “Of course I’m interested in planting some fun new grape varietals, too.”

Fruit: Apricots** • Blackberries** • Cherries** • Grapefruit • Nectarines** • Oranges • Peaches** • Raspberries** • Strawberries*

Vegetables: Artichokes • Arugula

Asparagus • Beets • Bok Choy • Broccoli

Brussels Sprouts*** • Cabbage • Carrots Cauliflower • Celery* • Chard Collards • Garlic • Kale • Leeks

Lettuce • Mushrooms • Onions • Peas*

Potatoes • Radishes • Spinach • Summer Squash** * comes into season in April ** comes into season in May *** goes out of season in April

Source: Serendipity Farms

Fish: Abalone (farmed) California Halibut (hook-and-line, bottom trawl) • Dungeness Crab • Lingcod Market Squid • Pacific Sanddabs

Sablefish/Black Cod (hook-and-line, jig) Rock Cod/Snapper/Rockfish (hook-andline, jig) • Sole (Dover and Petrale)

Spot Prawns • White Seabass (hook-andline)

Source: Local Catch Monterey

Note: Only seafood considered sustainable by Seafood Watch is included here.

Gabriella Café has been a fixture of the local, seasonal foods movement since the restaurant opened nearly 20 years ago, just a couple of blocks down Cedar Street from the Downtown Santa Cruz Farmers’ Market.

In the beginning, owner Paul Cocking, a former high school English teacher who’d used the proceeds of a stint as a Santa Monica Jaguar salesman to open Gabriella, and Jim Denevan, the restaurant’s first chef, began buying most of its produce right from the market. Today, 95% of the restaurant’s produce comes from the city’s farmers’ markets and deliveries from local organic growers like Live Earth Farm and Dirty Girl Produce.

Denevan remained with the restaurant for 10 years before taking the farm-totable movement on the road with his acclaimed Santa Cruz–based Outstanding in the Field, the roving restaurant that celebrates local farmers and food artisans by setting the table literally in the field, around the world.

Cocking, meanwhile, is preparing his own next act: a permanent, indoor local food artisan market in downtown Santa Cruz.

“We are talking to a building owner right now to start a kind of Santa Cruz version of the Ferry Plaza,” Cocking says, referring to San Francisco’s Ferry Plaza Farmers’ Market.

Cocking’s plan is to include a baker and a few farms as well as some of his former cooks, such as Rebecca King and her Garden Variety Cheese (a sheep’s milk dairy) and charcuterie specialist Brad Briske, who will provide the anchor business, a café and attached salumeria and crudo bar. Briske, who is back serving as sous-chef at Gabriella after a turn working for Main Street Garden, also plans to host a supper club at the café a few nights each week.

Meantime, Cocking says, Gabriella “is more seasonal and market-driven than it ever has been”—and has been attracting more praise and business as well.

For the recipe opposite, Adrian Cruz, who has been with Gabriella for much of the past 15 years and recently returned as its head chef, highlights just a few simple ingredients to bring out the fresh flavors of our local bounty.

“The chicory greens are a cross between radicchio and bitter greens, and are pretty tough,” says Cruz. “They like hard weather.” Because of the durability of this cold weather lettuce, it doesn’t get damaged in the wet climate of late winter and early spring.

Amber Turpin has immersed herself in all things food since she was a child. Her latest endeavors are homesteading at her property in the Santa Cruz Mountains and launching Filling Station, a café and bakeshop on Santa Cruz’s West Side.

Gabriella Café • 910 Cedar St. • 831.457.1677 • www.gabriellacafe.com

Dressing:

1–2 cups olive oil

1/3 cup Dijon mustard

1/4 cup apple cider vinegar

1 1/2 tablespoons honey

1 tablespoon diced shallot Pinch salt Pepper to taste

Blend all ingredients together in a food processor until it emulsifies.

Salad: 2 heads of chicory lettuce, clean

1 cup Dungeness crab

1/2 bunch radishes, sliced 1/2 red onion, sliced

Toss lettuce, crab, radish and onion together in a large bowl. Add dressing. Serve chilled.

Recipes: Additional recipes from Gabriella Café can be found at www.ediblemontereybay.com under the “Recipes” tab. The recipes are Slow-Braised Short Ribs with Wild Chanterelle Mushroom Bread Pudding, Mizuna Salad with Pickled Chickpeas and Castle Vetrano Olives and Roasted Live Earth Beets with Walnut Purée, Arugula, Candied Citrus and Herb Chevre.

Find ultra-fresh, local produce and support your local farmers!

CARMEL

Barnyard Shopping Village

3690 The Barnyard • 831-728-5060

Tuesdays, 9am–1pm • Open May–September www.montereybayfarmers.org

CASTROVILLE

Castroville Farmers’ Market 11261 Crane St., North County Recreation Center 831.633.3084 • Thursdays, 4–dusk Open May–October • www.ncrpd.org

GREENFIELD

The Sundays Market 98 S. El Camino Real at Huerta Ave. • 831.674.5591 Sundays, 9am–3pm • Open May–August

KING CITY

King City Farmers’ Market 905 Broadway St., South Valley Auto Plaza parking lot 831.385.3814 • Wednesdays, 4–7 pm Open May–October • www.kingcitychamber.com

MARINA

Marina Certified Farmers’ Market 215 Reservation Rd., Marina Village Shopping Center 831.384.6961 • Sundays, 10am–2pm www.everyonesharvest.org

MONTEREY

Del Monte Shopping Center

1410 Del Monte Center, Whole Foods parking lot 831.728.5060

Sundays, 8am–12pm Open June–October www.montereybayfarmers.org

Monterey Fairgrounds Certified Farmers’ Market

2004 Fairgrounds Rd. 831.235.1856

Fridays, 3–8pm Open April–December

Monterey Peninsula College

980 Fremont St. 831.728.5060

Fridays, 10am–2pm Open year-round, rain or shine www.montereybayfarmers.org

Old Monterey Market Place

321 Alvarado St. at Pearl Street 831.655.2607

Tuesdays, 4–7pm (winter), 4–8pm (summer) Open year-round, rain or shine www.oldmonterey.org

PACIFIC GROVE

Pacific Grove Farmers’ Market

Central and Grand Avenues, in front of Jewell Park 831.384.6961 • Mondays, 4–7pm Open year-round • www.everyonesharvest.org

Alisal Community Farmers’ Market

632 E. Alisal St., Gabby Plaza • 831.384.6961 Tuesdays, 9am–5pm • Open spring–November www.everyonesharvest.org

Alvarez High School Farmers’ Market

1900 Independent Ave. at Boronda Road 831.905.1407 • Sundays, 8am–2pm Open April–November champfarmermarkets@comcast.net

Natividad Hospitals Farmers’ Market

1441 Constitution Blvd. • 831.402.4705 Wednesdays, 11:30am–5:30pm Open March–November

Monday: Pacific Grove

Tuesday: Carmel, Felton, Monterey, Salinas, Santa Cruz

Wednesday: Hollister, King City, Pacifica, Salinas, Santa Cruz,

Thursday: Castroville, Pescadero, Sand City, Soledad

Friday: Monterey, Santa Cruz, Watsonville

Saturday: Aptos, Half Moon Bay, Salinas, Santa Cruz, Scotts Valley

Sunday: Aptos, Gilroy, Greenfield, Marina, Monterey, Salinas, Santa Cruz, Watsonville

Salinas Old Town Marketplace

301 Main St., behind Rabobank

Saturday, 8am–2pm • Open year-round www.oldtownsalinas.com/market.asp

SAND CITY(New!)

The Independent Farmers Market

600 Ortiz Ave. • 831.394.6000

1st Thursday of every month, 4–9pm Open year-round, beginning April 5th www.sandcityca.com

Soledad Farmers’ Market

Front and Encinal Sts. • 831.737.8033 Thursdays, 4–8pm • Open May–December oldtownsoledad@yahoo.com

APTOS

Aptos Farmers Market

6500 Soquel Drive, Cabrillo College • 831.728.5060 Saturdays, 8 am–12 pm • Open year-round, rain or shine • www.montereybayfarmers.org

Seascape Village Farmers’ Market

Seascape Village • 831.685.3134 Sundays, 11am–2pm • Open May–October

Felton Farmers Market

120 Russell Ave. at Hwy. 9, St. John’s Catholic Church 831.454.0566 • Tuesdays, 2:30–6:30pm

Open May–October, rain or shine www.santacruzfarmersmarket.org

SANTA CRUZ

Downtown Santa Cruz Market

Lincoln and Cedar Sts. • 831.454.0566 Wednesdays, 1:30–6:30pm

Open year-round, rain or shine www.santacruzfarmersmarket.org

Live Oak/Eastside Market

21511 E. Cliff Drive, East Cliff Shopping Center 831.454.0566 • Sundays, 9am–1pm

Open year-round, rain or shine www.santacruzfarmersmarket.org

Santa Cruz Saturday Market

137 Dakota Ave., San Lorenzo Park 831.515.4108 • Saturdays, 10am–6pm Open April–November www.thesantacruzsaturdaymarket.org

UCSC Farm & Garden’s Market Cart

1156 High St. at Bay Street • 831.459.3240 Tuesdays and Fridays, 12–6pm • Open June–October www.casfs.ucsc.edu

Westside Santa Cruz Market

2801 Mission St. at Western Drive • 831.454.0566 Saturdays, 9am–1pm • Open year-round, rain or shine www.santacruzfarmersmarket.org

Scotts Valley Farmers’ Market

360 Kings Village Rd., Scotts Valley Community Center • 831.454.0566 Saturdays, 9am–1pm • Open year-round, rain or shine www.santacruzfarmersmarket.org

Watsonville Certified Farmers’ Market Peck and Main Sts. • 831.234.9511 Fridays, 3–7pm ª Open year-round, rain or shine

Watsonville Fairgrounds Certified Farmers’ Market

2601 E. Lake Ave. • 831.235.1856 Sundays, 8am–4pm • Open year-round

HOLLISTER

Hollister Farmers’ Market Fifth and San Benito Sts. • 831.636.8406 Wednesdays, 3–7pm • Open May–September www.downtownhollister.org

GILROY

Downtown Gilroy Farmer’s Market

Seventh St. between Eigleberry St. and Monterey Rd. 408.710.7147 • Sundays, 10am–2pm www.gilroyspiceoflife.com/home.html

HALF MOON BAY

Coastside Farmer’s Markets—Shoreline Station

225 Cabrillo Highway S. • 650.726.4895 Saturdays, 9am–1pm • Open May–December farmersmarket@coastside.net www.coastsidefarmersmarket.org

Coastside Farmer’s Markets—Rockaway Beach

200 Rockaway Beach Ave. • 650.726.4895 Wednesdays, 2:30–6:30pm • Open May–December farmersmarket@coastside.net www.coastsidefarmersmarket.org

Pescadero Farmers’ Market 620 North St., Pescadero Elementary School Thursdays, 5–8pm • outreach@mypuente.org

Making sauerkraut, kimchee and pickles is a great way to play with spring’s tender vegetables. It is also a good way to brush up on your preserving skills while the mountains summer fruits are mere ideas in the world—just blossoms and seeds—and have yet to come raining down upon us.

Spring is the time of year when vegetables are king. The beets, carrots and other root crops have had a chance to nestle into winter’s cold, damp earth and slowly grow into juicy, tender roots.

Fermenting vegetables and other food is the only way to actually increase nutritional value while preserving it. It is also a way to really eat locally because we foster the live cultures and promote cooperation with visible and invisible life that surrounds us. This is the real local biodiversity.

Fermentation is the safest way to preserve food because muchfeared botulism cannot create its dangerous byproduct in the aerobic environment of fermented foods.

Fermented foods are delicious, nutritious, safe and easy—a great introduction to preserving foods. My absolute fermentation hero, Sandor Katz, just wrote a new book on fermented foods titled The Art of Fermentation. It’s due out in May, just in time for when you really get into it.

In the meantime, the farmers are ramping up for the spring plantings, which will bleed into the busy summer harvest. These recipes will help you ramp up your skills.

Jordan Champagne is the co-owner and founder of Happy Girl Kitchen Co. She has a passion for preserving the local, organic harvest and loves sharing the secrets she has unearthed. She teaches preservation workshops at the company’s café in Pacific Grove.

Recipes: Please see p. 22 and 23.

Happy Girl Kitchen Co. • 173 Central Ave., Pacific Grove 831.373.4475 • www.happygirlkitchen.com

Courtesy of Jordan Champagne, Happy Girl Kitchen Co.

Makes 1 gallon

Sauerkraut is easy to make. We just need to create the right conditions, and the microorganisms do the rest. You will be rewarded with crunchy, tangy golden kraut to enliven your spring.

5 pounds cabbage 3 tablespoons sea salt 1 tablespoon juniper berries (optional) Optional: carrots, Brussels sprouts, turnips, beets, burdock root, apples, raisins

Suggested spices: caraway seeds, celery seeds, garlic

Chop cabbage into a large bowl, coarsely or fine, however you like. Sprinkle on the sea salt now and then. Mix the cabbage and salt (and juniper berries, if desired) together to distribute the salt evenly. The salt pulls water out of the cabbage and creates a brine in which the cabbage (and other vegetables) can ferment without rotting or softening. Note on salt: Use only non-iodized salt, such as sea salt and unchlorinated water, as these chemicals inhibit the growth of microorganisms. Pack into a vessel. Tightly push and pack the cabbage down using your hands or a kitchen tool, forcing as much air out as comfortable and encouraging the cabbage to release its juices. Note on fermenting vessel: Many folks use earthenware crocks for making kraut as the wide mouth gives easy access for tamping and cleaning. Other suggested vessels are wide-mouthed glass jars, stainless steel pots or food-grade plastic buckets (which are all much lighter than crocks).

Cover kraut with a plate or other lid that covers the surface snuggly. Place a weight on the cover to help force out the air and keep the kraut submerged under the brine. A glass jar filled with water or a plastic bag filled with salt brine all work well. Secure a breathable cloth over the container to keep out debris.

Press down on the cabbage over the next few hours to force out water. It may take 24 hours for the brine to rise above the level of the chopped cabbage. Add a salt water solution (1 tablespoon sea salt completely dissolved in 1 cup water) as needed to cover the cabbage if, after a day, it remains high and dry.

Let fermentation happen. Put the vessel in a cool spot. Check on your kraut every day or two to skim off any surface scum, which is just an aerobic phenomenon where the developing kraut has come into contact with air—don’t worry about it. The kraut below the surface is unaffected and fine. Rinse off your cover and weight to discourage the surface mold.

Start tasting the kraut. It will be fully fermented in 2 to 4 weeks at 70° to 75° F or 5 to 6 weeks at 60° F. The air bubbles you see rising to the surface, a result of our busy microbe buddies, will become slower and eventually cease after the kraut is fully fermented.

Eat the kraut. You can begin eating the young kraut any time to enjoy the evolving flavor as it matures over several weeks. Remember to replace the clean weight on top, adding brine to keep it covered.

Store and start some more before it’s gone. Pack the kraut tightly in jars and store covered in the fridge for several weeks (or longer). Eventually, it softens, and the flavor turns less bright. Rinse the crock, repack it with fresh salted cabbage and add some old kraut to get your new batch started with active cultures!

There are many names for a mixed pickle, from Pickle Lilly to chow chow. This recipe is for a fresh mixed pickle, which is easy and safe and a great introduction to pickling. You can experiment with any combination of fresh vegetables and spices you desire or highlight whatever may be abundant at the moment. I always toss in a few beet slices to add great color to whatever I am pickling and some chili to spice it up. Keep in mind that you will be cooking all of the vegetables together in one jar, so pay attention to how thickly you slice them.

Cauliflower (separated into small florets) Beets (quartered and sliced 1/4-inch thick)

Carrots (quartered and speared)

Romanesco (separated and sliced)

Cabbage (grated 1/4-inch thick) Onions (in 1/4-inch rounds)

Thyme Pickling Spice Blend (or spices of your choice)

Vinegar Brew

12 cups water 8 cups apple cider vinegar 1/4 cup sea salt

Go to the farmers’ market or your own garden and pick the freshest vegetables possible. Chop and prepare vegetables into desired shapes and sizes to fit into your jar of choice. Start with a clean jar and add spices that you desire. Pour the hot vinegar brew over your vegetables and fill to the rim of the jar. You can experiment and make each jar unique using different spices and vegetables. Screw lid on tightly and put in your refrigerator. Let it sit for 2 weeks. It will keep in the refrigerator.

Hidden away in our own Monterey Bay area is a place that has had tremendous influence on the way America cooks and eats today. The Tassajara Zen Mountain Center in the heart of the rugged Ventana Wilderness is not a cooking school, but the cooks who have worked in the Tassajara kitchen over the past 45 years have helped spark our current love affair with fresh, healthful and locally grown vegetables. And through their many cookbooks, people like Edward Espe Brown, Deborah Madison and Annie Somerville have taught us that vegetarian cuisine is not only healthy; it can also be complex, beautiful and delicious.

Like so many students before him, Dale Kent arrived at Tassajara attracted by Brown’s iconic Tassajara Bread Book, which was first published in 1970. Equipped only with a degree in philosophy and some work experience baking cookies, Kent was assigned to clean rooms for his first summer but eventually found his way into the legendary kitchen that he had read about in the bread book. There, he began learning how to work magic with vegetables.

For two seasons, from 2002 to 2004, Kent served as head cook, or Tenzo, which is an important post at the Zen Buddhist center because along with preparing three meals a day for up to 80 guests and 70 students, the Tenzo is also a teacher who guides the spiritual growth of some 20 kitchen staff.

“We have a little service every morning, offering incense and chants to remind ourselves that this is a much bigger process than just filling empty stomachs,” he says. “It is actually offering energy for the flourishing of people.”

At Tassajara, which is part of the San Francisco Zen Center, cooking is not just working on food but also working on yourself. So it was with some trepidation that I agreed to attend Dale’s summer workshop called “Finding Yourself in the Tassajara Kitchen.” Getting there was hard enough. Driving that last 12 miles down a rutted, winding, dirt road at the end of Carmel Valley and into the Los Padres National Forest took more than an hour. Since I’m more of a gardener than a meditator, I was nervous about what was in store for me at the Japanese-style Zen center and hot springs at the end of the road.

Anyone who was around in the 1970s probably remembers when The Tassajara Bread Book first came out. In my little kitchen up in the Santa Cruz Mountains, I stood at a flour-drenched wooden table and kneaded loaf after loaf. It was fun. My friends appreciated hot bread from the oven, and it was liberating for me to discover I could make something so basic as bread, and not feel dependent on Staff of Life bakery or the supermarket.

Dale’s workshop was just as fun and empowering. Along with Tassajara’s current head cook, Graham Ross, we sat calmly in the meditation hall in the morning, discussing the experience of cooking and the Zen manuscript Instructions for the Cook, written by Eihei Dogen back in the 13th century but still oddly relevant today. Then in the afternoon, we prepared food for the staff and other guests staying at the center.

If you do not pay attention in the kitchen and “cook with mindfulness,” then the results will be meaningless, we were told—meaningless to the soup of your own soul and damaging to the community you are feeding. So trying to be mindful, we entered the fabled kitchen and began chopping carrots and slicing cucumbers under its rough-hewn beams. Graham showed us how to sharpen knives and chop properly. Dale taught the class how to make delicious vegetable sushi filled with carrots, scallions and avocado.

Talking is normally prohibited in the Tassajara kitchen—to help with the mindfulness—but the rules were bent for us novices. Even so, we tried to stay as quiet as possible and just focus on our work. Surprising thoughts bubbled up in my mind. How did my sushi rolls look compared to those made by others in the class? How could they be satisfied with their less-than-perfect products? What’s the point of making mine look good if they are going on the same plate with others that are falling apart? Hmmm…am I a competitive perfectionist? Maybe that’s what they meant by finding yourself in the Tassajara kitchen.

The food at Tassajara is traditionally vegetarian because Tassajara is a monastery, but vegetarianism is not a requirement of Buddhism and there is nothing Spartan about the cuisine.

It is about 80% organic, with most of the produce grown at James Creek Farm in the Cachagua Hills, so the ingredients are top notch. The food at every meal was delicious. One morning we had

Whole Wheat Ginger Bread with Orange Syrup. For lunch we slurped Broccoli Soup with Mint Crème Fraiche and the famous homemade Tassajara breads. The dinner we prepared included Sushi, Sweet Ginger Tofu, Cucumber Salad, Sautéed Daikon and Chocolate-Dipped Strawberries.

“It’s tricky to get meat eaters to feel satisfied at the end of a vegetarian meal, and I think we do a really good job of that,” Kent says. “We walk a fine line between preparing kind of fancy food, nicely presented, and offering rustic, home-style cooking.”

Vegetarian food isn’t always easy to make pretty, so garnishes are especially important at Tassajara. There’s a flower garden that supplies nasturtiums, lavender, calendula, bachelor buttons, grape leaves and roses. “Lots of our food is brown, but put a few flowers on it and it sparkles and people are excited to eat it,” he says. “Just putting one rose petal on a bowl of yogurt, for example, is a nice touch and makes that yogurt seem even more special.”

Kent’s own Tassajara Dinners and Desserts, lusciously photographed by Patrick Tregenza, is the latest in the series of influential cookbooks to come out of Tassajara. It reflects his love of Asian flavors and current tastes for lighter vegetarian meals. The book includes lots of amusing parables from the kitchen and makes Kent the latest in a long lineage of cooks who’ve contributed to the Tassajara mystique.

Edward Espe Brown, Tassajara’s first head cook and author of the bread book as well as The Complete Tassajara Cookbook and many other volumes, is now 66. As an ordained Zen priest, he still lectures and leads meditations in Marin County. I tracked him down one sunny morning in his writing studio at the back of a weathered wood house on Tomales Bay. As seagulls squawked overhead and ducks paddled by, we talked about his early days at the center and some of his cooking secrets.

“Some things end up speaking to you, and bread certainly spoke to me,” he says. “Wheat is earthy, it’s sweet, it’s hearty and substantial, but on the other hand you can do things with it that are fairly delicate and light.” He attributes the tremendous success of The Tassajara Bread Book to drawings that actually demonstrated, for the first time in print, how to knead dough. He also credits the book’s attraction to a primal need people have to do something “real.”

“There’s a deep longing to produce something with your hands, so you have something to show for it and share with other people. It makes you feel you have some way of taking care of your own life,” he says.

Tassajara’s Japanese founder, Suzuki Roshi, once told Brown and other students, “I don’t understand you Americans. When you put so much milk and sugar on your cereal, how can you taste the true spirit of the grain?” It was a turning point in Brown’s cooking style. Instead of making things according to recipes or the way the dishes were supposed to taste, he started experimenting with ways to bring out the best in each ingredient.

In Zen, this is a life lesson as well: “Why don’t you taste the true spirit of yourself?” Brown explains. “Why don’t you know yourself instead of trying to make yourself over the way you’re supposed to be?”

By carefully tasting each ingredient, Brown started to develop the Tassajara style of cooking. “It turned out I liked a sharp knife,” he says. “I liked cutting up the ingredients, and I found out over the years that small pieces work best. Cut surfaces release more immediate flavor and it is especially true with vegetables.”

Brown also likes to use fresh herbs, peppers and lots of lemon. “At one point I put lemon in every dish,” he says with a laugh. “Lemon gives a floral, fresh, tart flavor and that tartness is important to me in cuisine; it’s so good.” Peppers warm the palate. “The food seems to fill up the mouth more,” he says.

Brown, who was the subject of the award-winning 2007 documentary How to Cook Your Life, says one of the key lessons he learned as a cook at Tassajara was that “you are only as good as your last meal,” so cooks should just put their hearts into their work and try to ignore complaints.

“Certainly if you are cooking for a group of people, somebody will not like it. So if your self-esteem is based on your performance, your self-esteem is always going to be shaky,” he says. “But if you know that you’ve put a wholehearted, sincere effort into something, then you can let go of the other part.”

A wholehearted connection with the true spirit of ingredients is easier nowadays, he believes, because of farmers’ markets and the farm-to-table movement. “If food is local, it’s more likely that you may know the producers, you may have visited the farm and it’s more likely that it speaks to you. Then you have much more connection with the food, the people and the earth.”

“I’m more interested in what speaks to your heart, rather than if it’s local or it’s organic…but what’s local and organic tends to speak to me more,” he says as we munched on a tasty apple from the tree in his front yard, cut into very thin slices.

From simple to superb Brown and Deborah Madison, who followed him as head cook at Tassajara in the 1970s, took vegetarian cuisine another giant leap forward with the opening of Greens restaurant in San Francisco.

A graduate of UC Santa Cruz, Madison spent a year working at Chez Panisse in Berkeley—a noisy kitchen where the radio was always turned up loud—before opening Greens as part of the San Francisco Zen Center. At Chez Panisse she was exposed to the cooking style of Alice Waters, and the cuisine at Greens reflected that influence.

“When Greens started, the food was pretty sophisticated,” Madison recalls. “It didn’t have meat but it had enough complexity that people didn’t miss it.”

“Lots of our customers were not vegetarians. They were food people coming to a beautiful restaurant with a beautiful view. The food happened to be vegetarian, but it wasn’t the drab, heavy food of the ’60s. It was light and bright and attractive and delicious,” she says.

Madison and Brown collaborated on The Greens Cookbook and since then, she has gone on to author 10 more books about food, including the celebrated Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone—which she envisioned as a kind of vegetarian Joy of Cooking. Because of that book and her role as founding chef at Greens, Madison is sometimes considered the goddess of vegetarians, a role she bristles at.

“You know what, I really don’t care about vegetarianism, and it’s not my purpose to advance it,” she said in a recent telephone interview from her home in New Mexico. “When I wrote the book, I had other more important concerns, like what do we do about organics? What do we do about how meat is raised? Eating local food and seasonal food and looking at heirloom vegetables, things that people weren’t talking about so much back then.”

Madison thinks eating meat is fine as long as people do it in the best possible way—for their own health, for the environment and for the welfare of the animals. She sums up her beliefs like a Zen master at Tassajara: “My philosophy is to be aware and know the consequences of the choices we make, paying attention to what you are eating, to how much, to where the food comes from and how it connects to the rest of your life.”

“If you are eating food that is harmful to other people to produce, grown with a lot of pesticides that poison rivers and groundwater, and is therefore hard on wildlife…well, then you need to know that,” she adds.

Ever the teacher, Madison is hard at work on a 12th book called Vegetable Literacy, due out in 2013. The book will profile individual vegetables and plant families and should help cooks improvise and create new dishes. Judging by excerpts from the book that appeared in many Edible Communities magazines around the U.S. last year, it will also make fascinating reading.

Annie Somerville served in Tassajara’s kitchen in the late 1970s, and like Kent, Brown and Madison, became head cook during her time there. Later, she worked with Madison at Greens, and since taking over as Green’s executive chef nearly 30 years ago, Somerville has gained a national reputation for her imaginative approach to vegetarian cooking.

A sparkly woman with a pixie haircut, Somerville loves to see how excited chefs and home cooks are about using vegetables nowadays.

“Tassajara has really influenced the way people cook, and I think we’ve had a sizeable influence, too. Particularly in the early days, what we were doing was so unusual because it was hard to find a restaurant that prepared really delicious vegetarian food,” she says. “Now almost all restaurants have good vegetarian dishes.”

Over the years, Somerville has adapted the menu to suit evolving tastes and to take advantage of the increasing variety of fresh ingredients available to chefs.

“Early on we used dairy products more heavily than we do now, lots of cream, and we sautéed with butter and used a heavier hand with cheese,” she recalls. “Then we went through a low-fat period, but now we’ve reached a happy medium. We find the right places to use really good cheeses, a touch of cream here or there, a nice butter sauce—a brown butter pasta or Meyer lemon cream, that sort of thing.”

Somerville thinks it’s important that a vegetarian meal feature distinct and diverse dishes, including vegetable appetizers and both standout entrees and side dishes. Otherwise, the items on a vegetarian menu can all sound the same.

May 31–June 3

“Breakaway Cooking with Tea”

Eric Gower and Ikushin Dana Velden

June 22–24

“Dragon Greens: A Cooking and Gardening Summer Solstice Celebration”

Annie Somerville and Wendy Johnson

June 29–July 1

“Finding Yourself in the Tassajara Kitchen”

Dale Kent and Unzan Graham Ross

The goal is “really nice dishes that stand on their own but just happen to be made with all vegetables,” she explains. “People come to Greens and have a great salad or a great vegetable ragout, a tagine or a delicious pizza or pasta. All of these things can be made with vegetable ingredients, and they are delicious.”

She delights in going to the Ferry Plaza Farmers’ Market twice a week and watching the seasons change through the produce that’s available. “It’s probably the main thing that keeps me engaged and excited about food,” she says. “Some people might really get tired of this after 30 years, but I love those direct connections with farmers and experiencing first-hand the moments of the seasons.”

Somerville, along with gardener Wendy Johnson, will return to Tassajara in June to teach a workshop on vegetarian cooking from harvest to plate called “Dragon Greens: A Cooking and Gardening Summer Solstice Celebration.”

Since the San Francisco Zen Center still owns Greens, it will probably always remain a vegetarian restaurant. Along with the former cooks of Tassajara and cooks to come, it will continue to set the pace for American vegetarian cuisine and shape our continuing passion for vegetables.

Deborah Luhrman was once the Santa Cruz County bureau chief for Channel 46 news. She has been traveling the world and spending too much time on airplanes for the past 25 years. So she returned to Santa Cruz to grow a garden and write about local issues.

Recipes: For Somervilles’s recipes for Asparagus and Beets with Meyer Lemon Vinaigrette and Fava Bean Purée with Garlic Toasts and Shaved Pecorino and Kent’s recipes for Sweet Ginger Tofu and Glazed Daikon, go to www.ediblemontereybay.com and click on the “Recipes” tab.

By Elizabeth Limbach Photography by Ted Holladay

By Elizabeth Limbach Photography by Ted Holladay

Unlike many modern cafés, which boast litanies of complicated, flavored concoctions, the drink menu at Verve Coffee Roasters is strikingly simple. After all, co-owner Colby Barr doesn’t travel 12 weeks out of the year to remote villages around the globe to source “the best coffee on earth” just to have it disguised by syrups and frills.

“We’re buying coffee from ultra-specific farms and people who have specific flavor notes and varietals, and letting those bloom on their own,” explains Chris Baca, Verve’s director of education. “We don’t need to dress up our coffees.”

This is characteristic of a “third wave” coffee shop, although the Verve folks dislike the term, which was coined to describe the generation of specialty coffee that followed the “second wave,” or the Starbucks/latte/mocha generation. If anything, Verve may be closer to “fourth wave”—part of a yet-to-be-defined movement, forging the path that the rest of the industry may someday follow. “Whatever you want to call it, we just want to see ourselves on the frontlines,” says Barr.

Barr and co-owner Ryan O’Donovan opened the first Verve, on 41st Avenue in Santa Cruz in November 2007 with the help of head roaster Sean White and barista Jared Truby. In mid-2009, when Baca came on board, the company had about a dozen employees and wholesale accounts in the single digits. The 590-square-foot roastery was adjacent to the café “so you could see the roaster if you were a customer in the café but also so that the roaster could see if we got buried on [the] bar because there was such a small crew, and come in and help,” recalls Barr.

Interest in Verve’s top-notch coffees and famously skilled baristas (who, for example, undergo three days of training and a fourhour test before getting hired) has boomed in the years since—enough so to land it wholesale accounts across the country, from New York and Los Angeles to Pittsburgh and Austin—and catalyze major retail expansions. The Verve team is now 45 employees strong and is spread across three locations, including two that opened in fall 2011: one in Santa Cruz’s Seabright neighborhood, where the company operates a 7,000-square-foot roastery, and one on Pacific Avenue in Downtown Santa Cruz.

Verve’s latest triumph is being chosen by the Specialty Coffee Association of America as host of the 2012 Southwest Regional U.S. Barista Competition, which will take place in Santa Cruz on March 9, 10 and 11. The competition will be one of six regional events that feed into a national showdown later in the year. (What’s a barista competition? See related story, “How Do I Compete?” on p. 34.)

Baca organized the event along with Verve Director of Retail Sara Peterson. Both baristas are former regional champs and have placed second and fourth, respectively, at the U.S. level.

Verve had its eye on hosting the competition for several years, but California-based chain, Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, hosted it the last two years and provided a Hollywood television studio as the venue.

Fourth wave: Clockwise from upper left, Verve co-owners Ryan O’Donovan and Colby Barr; Verve’s new Seabright location; freshroasted coffee beans.

In bringing the competition back to a small company and a small town, Verve hopes to re-envision what has historically been an exclusive, somewhat esoteric event.

“We’re trying to shake all of that loose and bring everyone to Santa Cruz to have a good time,” says Barr.

Verve will host social activities for visiting baristas throughout the weekend and has added an educational component as well, partnering with the Barista Guild of America to offer classes and Level One testing for barista certification.

As for non-coffee professionals, the event is free to attend and promises to be fun and, of course, caffeinating.

“It’s entertaining, and kind of goofy,” says Barr. “It’s kind of like Best in Show, but for coffee.”

Attendees can partake in tastings, including—for the first time ever—the drinks competitors make for the judges.

“In the past, it’s been a joke in a way that people come to see, but they just watch four lucky judges taste the coffees,” says Barr.

But as part of Verve’s overall vision of making world-class coffee more inclusive, competing baristas will be required to stay for half an hour after the competition to make cappuccinos, coffee and specialty drinks for members of the audience.

“Our goal in our whole company, and thereby in this event, is to always be trying to do the best we can at world level but making it as accessible to people as possible,” says Barr. “Because, otherwise, what’s the point?”

Elizabeth Limbach is an award-winning journalist based in Santa Cruz. When not working, she can often be found enjoying the area’s beautiful outdoors, seeking out new delicious eateries and indulging in her latest obsession—vegan baking.

The competition will be held Friday, March 9 through Sunday, March 11 on the fourth floor of the Rittenhouse Building, located at Pacific Avenue and Church Street in Downtown Santa Cruz. Visit www.usbaristachampionship.org to learn more about the competition, or follow it on Twitter at @swrbc2012. For more about Verve, including location and contact details, visit www.vervecoffeeroasters.com. (See related story, p. 24.)

Looking for fresh-roasted coffee closer to home? Go to the “Local Food Guides” tab on the EMB website and scroll down to find “Micro-Roasters Near You,” a complete guide to artisan roasters in the tri-county area.

Regional competitions like the 2012 Southwest Regional U.S. Barista Competition are open to any barista “who dares to compete,” says Chris Baca, Verve’s director of education, but “if you don’t do your homework, you’ll feel ridiculous and get destroyed.”

To avoid this, Baca, whose own rule-bending 2010 regional performance made coffee competition history, is serving as mentor and trainer to the two Verve baristas competing in March: Lizzy Sampson, 21, and Jared Truby, 29.

The baristas began their training in December, first studying competition rules and then working with senior Verve staff to select ingredients and perfect their drink recipes. The training will culminate with rehearsals of their precise routines in the weeks before the event.

“By the time you’re at the competition, what you’re doing on stage should be second nature to you,” says Baca.

The competition itself is akin, in part, to a live cooking show, complete with an audience and seven judges.

“It’s nerve-wracking the first time,” says Peterson, who has been with Verve since 2009. “There are lights shining on you, they’re streaming it online, you’re wearing a Britney Spears-[style] microphone, there’s an audience—it’s really surreal.”

Competitors are provided with an espresso machine and table but must bring everything else themselves, from the coffee and ingredients to table settings and coffee grinders.

“They wheel you out to this blank canvas, and you have everything stacked up on your cart, and you have 15 minutes to unload, prep, dial in your coffee, taste and clean your area before the judges get there,” explains Baca.

Once the judges arrive, the barista has 15 minutes (after which they’re disqualified) to make three courses: a single espresso,

a cappuccino and a “freestyle,” or specialty, drink. As they work, the baristas must explain to the judges and audience what they are making and why.

Three technical judges watch closely as the drinks are made and score in categories like efficiency, cleanliness and technical skill, while four sensory judges are served the beverages and grade on flavor, balance, consistency, color, presentation and more.

Competitors choose the soundtrack that plays during their performance—both to help set the mood and also to cue the different stages of the routines they will have memorized.

“It’s like playing a piano—you want to learn it technically first, so well, that you can forget about all of the technical stuff and play it by feel,” says co-owner Barr.

That anyone first found it edible is a testament to curiosity, persistence, risk. By all appearances, the artichoke is an anachronism, a prehistoric plant whose thorny plates of armor protect its vulnerable heart until it dries from the inside out and releases a spiky purple blossom. To anyone who hasn’t tried it—or ever imagined eating a thistle—it can be confounding.

And yet, when dragged through mayonnaise, yogurt or warm, drawn butter, each sharp, fibrous leaf becomes a delicacy; once they are pulled through the teeth, leaving behind only that which is soft, succulent, tender, tasty and melting in the mouth, even the uninitiated and the skeptical come to understand why the artichoke is considered an aristocrat of the vegetable kingdom.

Although not native to this area or even the United States, the artichoke’s longevity in this region’s rich, sandy loam and cool, coastal climate; its popularity on local menus, both trendy and traditional; and its abundance here make the artichoke one of the iconic plants of the Monterey Peninsula. They thrive throughout our local foodshed, which produces as much as 80% of the artichokes grown in the U.S.

No one knows just when artichokes, which come into season in March, arrived on this continent. Some accounts place their introduction in the 19th century, by French immigrants in Louisiana and Spanish settlers in California. Others say they were brought to Colonial Williamsburg in 1720 to indulge aristocratic immigrants from Europe.

Artichokes had already reached Castroville on the northern peninsula by the time Battista Odello brought his bride, Josefina,

from Northern Italy to Carmel in 1924 with the promise of prosperity through artichoke farming at the mouth of the Carmel Valley.

Odello leased, ultimately, 340 acres from the Thomas Oliver family, whose coastal river-bottom lands were bisected by Highway 1 just south of Carmel. There he and 17 partners planted artichoke slips cut from Castroville crops, and six months later brought in their first harvest by hand. Eventually his two sons, Emilio and Bruno, entered the operation, taking the helm in 1945. Ten years hence, they purchased the property.

By 1964, Bruno’s son John, armed with a degree in agribusiness from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, had joined the family business that had shaped his growing-up years.

“My family was the first to farm artichokes in Carmel Valley,” says the third-generation artichoke farmer, whose father is now 97. “John Emile later came in to farm where the Crossroads and Barnyard shopping centers are. Joe Sbarra planted artichokes where Rancho Cañada Golf Club is now. And the Pezzini family, still prominent in artichokes, partnered with my grandfather.”

Theirs was a community sustained by artichokes. It was their lifestyle and their livelihood, their “daily bread” and even the currency with which they bartered for everything else they needed.

“We rarely went to the store,” says John Odello from his kitchen table in Carmel, a room like every other in the home he shares with wife, Marie: artfully adorned but not overrun by objets d’artichoke. “When my grandfather established our artichoke fields, he was land rich and cash poor, so he implemented the European custom of bartering. Down at the wharf, we traded a sack of artichokes for a bucket of fish or abalone. Up the Valley, we traded artichokes for apricots

and pears. My grandmother canned what we couldn’t eat. We planted a vegetable garden by the cookhouse and raised pigs by the barn. We even made our own soap.”

When harvesting his more than 300 acres of artichokes, John never wore gloves. They got in the way of his technique, he says— the flick of his wrist that helped him cut hundreds of chokes per hour while avoiding the thistle’s spiny defenses.

“When we farmed artichokes,” he says, “we grew globe artichokes by breaking a stalk off an older plant and letting it take root in the ground. It took six months. Nowadays, that process is too costly, so farmers grow artichokes from a seed, which has a yield in 90 days. But the artichoke lover can tell a globe from a seed artichoke. The globe is tight, whereas the seed is open. The globe is hard, like an apple, and the seed artichoke is soft. If it doesn’t squeak when squeezed, don’t buy it. This means the artichoke is dehydrated and will get tough when boiled. But when an artichoke is just right, it is still the best.”

You know you have waited too long to harvest an artichoke, he says, when the leaves have popped open. By then, the heart has begun to harden, and the stem has become woody and brittle. In late harvest, it takes twice as long to saw through the dry stalk. And a cook cannot boil or bake or roast or fry the choke back to succulence.

Yet if harvested when the leaves are still clenched in a tight fist, the artichoke will be soft at the center. The stem will yield to one slice of the X-Acto knife, and the heart will remain tender.

“When the artichoke is mature but not over-ripe,” says John, “you don’t need to hide it; you can just boil it in a little lemon juice and vinegar, and it’s great. Of course, it was such a staple for us that

we came up with all kinds of ways to serve it—in soups, salads, frittatas, gnocchi, grilled, breaded and fried—and we never grew tired of it. But that was then, when the fields were active. Today, we buy our artichokes and consider them a treat.”

The Odello artichoke fields were in full production in 1995 when the El Niño storms hit the Peninsula, flooding the fields and destroying their yield. The family restored the fields and returned to farming, only to witness the wrath of El Niño return two years later. This time, they “called it quits.”

“Today, the fields west of Highway 1 to the ocean belong to the State of California,” says John, “and the acreage east of the highway belongs to Clint Eastwood. Some days I miss it, miss the artichokes and the life we built around them. Every day I go down to visit my father, who still lives on the property. Some people say it’s great to see the land restored to its native state, back to what it was hundreds of years ago. I wonder who here knows what it looked like then.”

Lisa Crawford Watson lives with her family on the Monterey Peninsula, where she is an instructor of writing and journalism for California State University Monterey Bay and Monterey Peninsula College. Lisa is also a freelance writer, specializing in art & architecture, health & lifestyle and food & wine.

For related stories, see p. 38 and 39. For Marie Odello’s recipes for Artichoke Linguini, Artichoke and Chicken Sauté and Artichoke Hearts stuffed with Crab, Macadamia Nuts and Boursin Cheese, go to www.ediblemontereybay.com and find the “Recipes” tab.

If all goes according to plan, the Big Sur Land Trust (BSLT) could soon return some 30 acres of the legendary Odello artichoke fields to organic agricultural production—and install a new system of hiking trails that would connect it to the pristine Palo Corona Regional Park.

“Getting into organic farming takes awhile to put the infrastructure in place,” says BSLT Director of Philanthropy Lana Weeks. “If it happens any time in 2012, it will be great.

“The Southbank Trail is open, but the Regional Parks District has the key to Palo Corona, so our hope is to figure out parking and logistics to enable people to go from Southbank Trail into Palo Corona by walking right past the farm fields. Eventually this will be called the Carmel River Trail.”

The farmland to which Weeks refers is the 30 acres in front of the Odello’s Palo Corona barn, closest to Inspiration Point. She often studies the land in wonder and amazement at all that has happened historically on that piece of land, while imagining the generations that have gone before her, cultivating and living “off the fat of the land.”

“Here we are, hundreds of years later,” she says, “and that piece of land still has not been developed or destroyed. Six cultures have lived and worked on this very land before us—the Rumsen Indians, the Spanish, Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese—and it was somehow sacred to each of them. I find it amazing that so many cultures found the power of this place. It is a very spiritual space to withstand time and never be developed beyond farming. I marvel at the blessing.”

Weeks’ hope and expectation is that the BSLT can work in partnership with the organizations that will develop the system of

trails and the organic farm, creating a seamless experience and a legacy of land for future generations to experience.

The Odello artichoke fields were very nearly lost to all but several dozen homeowners when previous buyers of the property sought several years ago to develop the land into 82 tract houses.

That plan was thwarted when actor-director-developer Clint Eastwood and his former wife, Maggie, stepped in to purchase the property. The Eastwoods saw some 130 acres of the Odello fields as a kind of crossroads to provide public access to state and regional parklands, if preserved.

“In essence, the Eastwoods gave 30 acres in that development plan to the BSLT,” says Alan Williams, president and CEO of Carmel Development Company, who works with Eastwood on his development projects. “The BSLT, working with the State and Regional Parks districts, has come up with a beautiful plan to tie it all together.”

She came to town as an afterthought. A relatively unknown up-and-comer chosen to replace starlet Doreen Nash, who had canceled a jewelry store appearance at the last minute, the young Norma Jean would have to do. It was 1948. Her stage name was Marilyn Monroe, and it was just catching on. At least she was pretty enough to promote diamonds.

During some free time between appearances, jeweler Stan Seedman attended a Kiwanis Club meeting in Salinas, where banker Randy Barsotti suggested they take Miss Monroe to Cal Choke for a photo session on behalf of an artichoke promotion. Perhaps, he said, they even could crown her the “Artichoke Queen.”

Marilyn Monroe’s legendary sash remains on display at the Castroville Chamber of Commerce. And her status as the first Artichoke Queen continues to lend a certain cachet to Castroville and its celebrated crop.

Sponsored by six local artichoke growers, the Artichoke Queen contest continued and became a highlight of the annual Castroville Artichoke Festival and Parade, which commenced in 1959.

In the early days, the festival was little more than a barbecue and a parade. Folks could count on chicken, beans, salad, coffee and a fresh-picked Castroville artichoke.

Today, the “Artichoke Capital of the World” and its festival attract some 30,000 people for the two-day event. The festival has grown into a city-wide celebration, featuring an Agro Art Competition of three-dimensional fruit and vegetable artwork, live music, children’s entertainment, arts and crafts, wine tasting, field tours and a farmers’ market.

And then there are the artichokes, prepared just about every way one can: fried, sautéed, grilled, marinated, pickled, fresh and creamed.

What: Castroville Artichoke Festival 2012

Where: Castroville, California

When: May 19, 10am–6pm and May 20, 10am–5pm

Cost: $10 adults, $5 active military, seniors and children ages 4–12; free for age 3 and under Contact: 831.633.2465 or visit www.artichoke-festival.org

It’s a crisp autumn evening in the Santa Cruz mountains. Birds are chirping and cawing in the surrounding redwoods that point faithfully toward a deepening blue sky. Hordes of commuters are corkscrewing their way home along nearby Highway 17 in anticipation of a well-earned dinner or cocktail in front of their favorite TV show or, better yet, with friends or family.

Meanwhile, Cynthia Sandberg is scooping cow manure out of cow horns and stirring it into buckets of well water with a broomstick. Later, she and six apprentices will use paintbrushes and cornhusks to flick this solution onto thousands of plants before the sun completely disappears and darkness takes over.

This image may seem ritualistic, even creepy to some. But it’s just another day here at Love Apple Farms, a 20-acre, terraced property with sweeping views of the Santa Cruz Mountains, which serves as an educational center and the exclusive biodynamic kitchen garden for chef David Kinch and his two-Michelin-star Los Gatos restaurant, Manresa.

As the light begins to fade, farmer-proprietor Sandberg gathers her apprentices and farm partner, Daniel Maxfield, and begins to explain the idea behind Preparation 500, one of the many methods used in biodynamic farming.

“The land is breathing in as we go into winter,” Sandberg says between scoops, “and this preparation from the cow horn has taken into it the earthly forces from being buried and also through the manure from the cow.”

All of these forces are infused into the well water, creating a potent homeopathic substance that will help fertilize the plants and protect them through the cold months, encouraging growth and vitality.

The mixture is meant to be stirred by a human arm, wooden stick or some other natural material for one hour in one direction, creating a vortex, with random pauses “to create chaos.” Then it is stirred in the opposite direction to further enhance the forces already present. Seems a bit witchy, but reasonable.