10 minute read

EDIBLE D.I.Y

EDIBLE D.I.Y. FEATHERED FLOCK

From coop to soup, the joys of raising backyard chickens

Advertisement

BY JESSICA TUNIS PHOTOGRAPHY BY CRYSTAL BIRNS

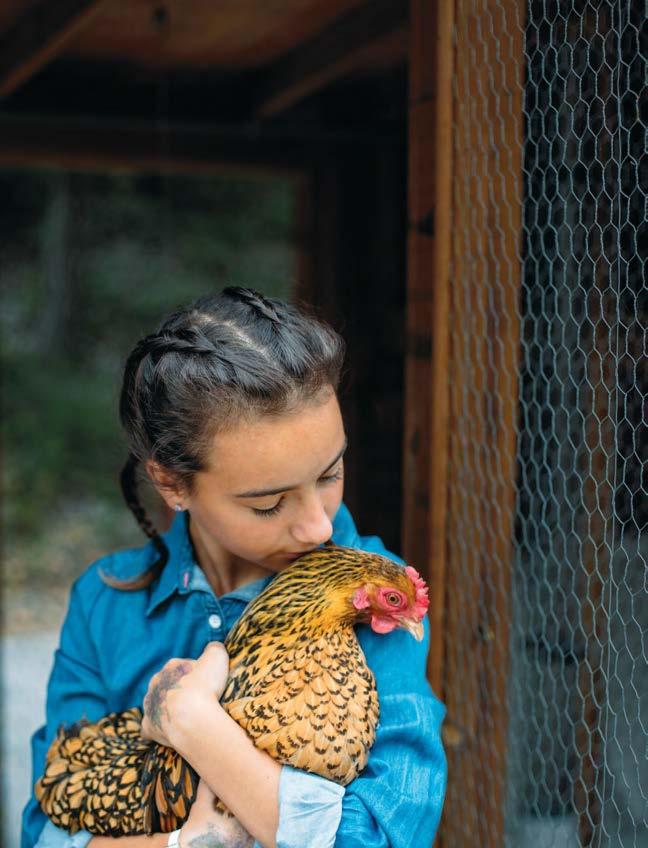

The chickens cluck and chuckle to themselves in the slanting afternoon light, scratching for bugs and seed with their fat feathered legs in the grassy backyard. They aren’t startled by our presence, as they know us well enough.

Chickens are smarter than people give them credit for. They can recognize up to 40 individuals and are especially fond of those who bring them food every day. They greet us with the calm, contented chortles of tame birds, as the kids toss them handfuls of scratch. The flock I visited with my daughter for this story was a mixture of fancy breeds with intricate plumage, and backyard mutts whose broody mothers laid a clutch of eggs in secret, hiding them from gatherers only to re-emerge weeks later with a dozen tiny chicks in tow.

If you’ve ever seen a supermarket egg cracked in a pan beside a home-raised egg, the pallid yellow yolk next to a rich gold one, you may have been shocked at the difference and decided right then and there to have your own chickens. Even birds raised on conventional pellet feed in a backyard will have eggs with noticeably stronger shells and darker yolks than those from a supermarket—this translates directly into increased nutrition. When building a flock, consider your family’s egg consumption, and whether you’ll want to trade eggs with neighbors and friends. A family of four, consuming two eggs per person per day, would want a dozen young laying hens. That average, two eggs per day per three layers, is a good starting point, but be aware that actual egg production will fluctuate with seasons, breed and age of the flock. In winter, egg production drops dramatically, though some breeds lay through the winter more reliably. As the birds age, they lay less each year; though they may live for eight years in a cozy henhouse, their peak laying is limited to their first two years. If you don’t want to continue feeding a bird past its laying prime, a dual-purpose bird, bred for both egg production and meat, is a good compromise. (See sidebar for best varieties.)

“Chickens are one of the few projects that we break even on,” says backyard farmer Tom Boland, who raises sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, geese and ducks in Boulder Creek. “In summer, when they’re laying at their peak, we even get a little ahead. In winter, it’s about waiting for egg production to ramp up again.” His family sells extra eggs to friends and neighbors to cover feed costs, but it’s hard to quantify the value, in this afternoon light, as the children take their favorite chickens onto the swing, of the connections being forged. These girls will grow up knowing about life and death, responsibility and respect. They already know how to scramble an egg in butter, how to set aside bones to make broth, and how to lift the fluffy chicks gently, tenderly, from the nest, and show them the green world outside.

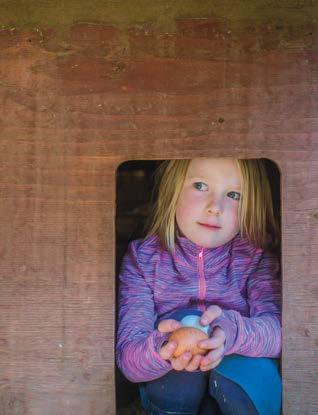

My daughter likes to crawl into the nesting boxes from the

What breed to choose?

If you dream of a connection to the food chain right in your own backyard, gathering eggs still warm from the nest, watching a flock of chickens peck and scratch in the garden, or even of raising your own birds for meat and bone broth—here are some varieties to consider.

Dual-purpose birds, like Orpingtons and Marans, Wyandottes, Delawares, and Rhode Island Reds were the historical choice of the backyard farm flock. They are reliable layers, though not quite as prolific as the egg-specific breeds, and they grow to a good size worth harvesting for the table. Egg-specific breeds like Leghorns, Welsummers, and Hamburgs favor egg production over making muscle and meat on their slender frames. They begin laying earlier than other birds, at about five months of age, and are often more skittish and nervous than dual-purpose birds. While this type mostly lay white-shelled eggs, the Ameraucana, also known as Easter Eggers, lay colorful eggs ranging from pale pink and olive to pale blue and light green. In fact, Martha Stewart has a paint line based on the colors of her Ameraucana eggs.

The meat birds best suited for a backyard flock are older breeds: the Brahma, Turken, and Cornish Game. These birds are large and meaty. Some, like the Dark Cornish, are even decent layers. Modern poultry farms use huge white birds known as “broilers,” which grow so fast and so unevenly that they often are unable to walk after a few months of life. Unsurprisingly, they also tend not to be very good foragers. These broiler birds, available as Cornish Cross, are an efficient choice for those who are certain they will harvest them on schedule. But if you’re at all squeamish at the prospect of killing your own birds, it’s best not to start with this breed, as you’ll soon run into problems past the age of harvest.

chicken entrance, eschewing the main door that makes egg collecting easier for adults. She gathers eggs still warm from the nest as though it were Easter. We’ve struggled and learned a lot about coop design over the years; birds require good ventilation, nesting boxes, roosts to perch on and protection from excess heat and cold. A covered outdoor area is ideal, too, so that birds can spend time outside even in the rain.

Rodents have been our worst problem in the henhouse, stealing both eggs and chicken food. A rodent-proof enclosure saves dollars and stress, as well as keeping out other potential pests like skunks, raccoons, and even hawks and owls. Rodents burrow as well as climb, so a truly secure enclosure will have gopher wire or hardware cloth lining the bottom, and chicken or aviary wire over the top. Pay special attention to corners, grade changes and seams where wire meets to ensure the best protection, and be aware that those little buggers will eventually gnaw through even thick-gauge wire.

Some coop designs provide a minimum of protection and allow the birds to forage freely outside during the day. Chickens will naturally put themselves to bed just before dusk each night. Other coop designs will keep the birds enclosed in a single area, ideally with some dirt to scratch in. The regular addition of fresh grass, vegetable scraps and dry bedding material such as rice hulls, hay or wood chips will enhance their environment and health.

Chickens are proficient foragers that will eat anything from bugs and worms, to seeds, grains, fresh greens and kitchen scraps. The more varied their diet, the healthier they will be. Baby chicks will need a finely milled feed specific to the nutritional needs of young birds. They can transition to larger pelletized adult feeds at 18 weeks old. Chickens raised for meat will do best on a grower feed, while egg layers require a layer mix. The true D.I.Y. chicken-keeper can also formulate feeds by hand from whole and sprouted grains. This approach, while more labor intensive and requiring a larger initial investment, usually provides better quality nutrition than the pelletized feeds.

With our first flock, we tried to outsmart our natural tendency to become attached to individual birds—the layers were a mix of breeds, but the dozen meat birds were all Dark Cornish hens. We thought that in this way we’d be able to harvest them more easily when the time came, but it was not to be. The birds all had subtly different feather patterns, personalities and habits, and defied our attempts to remove ourselves from the process. Killing is not pleasant work, but for someone who eats meat, it completes the circle of life in a way that feels right, somehow. The act of butchery can be a way to connect with the food chain, with our shared animal heritage and mortality. The birds we killed had names by the end, and in retrospect, I think it was better that way. When we pull a package labeled Bardo from the freezer, we remember the hen with barred black-and-white feathers and a crooked beak, and give thanks to her specifically, all over again.

Jessica Tunis raised her first chicken from an egg in elementary school and never looked back. She lives, writes and tends a homestead in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

BOLD AND UNIQUE FLAVORS IN A NEW AGE TAQUERIA SETTING MIJO'S TAQUERIA

BEET DEVILED EGGS

Courtesy Jessica Tunis These ravishing beauties are worth the effort. While deviled eggs have long been a staple of the season, these bright snacks are something special, with an added piquancy from the vinegar, balanced by mild sweetness and salt from the brine. And the color! A deep, rich magenta, that does not impart any beet flavor to the eggs.

Play with the infusion times; even 2 hours will give a lovely pink color to the outside of the egg, but a bit more time will allow that luscious color to bleed slowly into the center of the egg, like a drop of watercolor paint that spreads gracefully across a page. An overnight infusion will give you color all the way to the yolk; a two-day soak will yield the sharpest pickle flavor.

Photo by Jessica Tunis

12 hard-boiled eggs, peeled

For the pickled beet marinade: 2 pounds fresh beets 2 cups vinegar; red wine, white, champagne or apple cider all work well 2½ cups water 1/3 cup sugar 1 tablespoon salt

For the filling: 3 tablespoons mayonnaise 3 tablespoons sour cream 1 tablespoon prepared mustard Pinch salt and freshly ground pepper, to taste

Hard boil the eggs. Tip: Jostle the eggs now and then as you are cooking them, so that the yolks do not settle to one side or another, but rest in the center of the egg. Choose eggs that are at least 3 days old for the easiest peeling. Peel the eggs under running water, and refrigerate until ready to use.

Peel the beets and slice them in ¼-inch slices, then quarter the slices. Red beets give the brightest color; yellow beets make a soft golden hue that is less intense. If you’re aiming for a brighter gold, add a 1-inch piece of fresh turmeric, grated, to a golden beet mixture.

In a medium saucepan, pour the water and vinegar over the beets. Add sugar and salt. Bring to a boil, stirring to dissolve sugar, then simmer over medium heat for 30 minutes or until beets are tender. Remove the beets from heat and allow to cool. Remove the pickled beets from the liquid; they will have lost some of their color, but can be used in salads.

When the beet liquid has cooled, place the eggs in a large container, and pour the beet liquid over them. Allow the beets to infuse in this liquid in the refrigerator for at least 2 hours, and up to 2 days. A 2-hour infusion will stain the outsides but not the insides of the beet; 2 days will turn even the yolks pinkish. A happy medium is about 6 hours, where the centers and yolks are still their natural color.

Remove the eggs from the beet brine. Slice the eggs in half lengthwise, and gently pop the yolks out of the middle, into a small mixing bowl. Add the mayonnaise, sour cream, mustard, salt and black pepper, and mash the mixture with a fork until it acquires a creamy consistency. Scoop the filling into the center of each egg, mounding it up.

Prepare toppings to garnish the top of each egg; this is where to get truly creative. We used capers, finely chopped snow peas, calendula and borage blossoms, chopped red pepper, chives, parsley, smoked paprika and dill; just one or two of these ingredients per egg is ideal. But there are so many other beautiful topping options. Consider cucumber, zucchini or pepper relish, smoked salmon, bacon bits or black olives, just to name a few.

Arrange the stuffed eggs on a platter with other seasonal finger foods, such as carrots, radishes and snap peas. Enjoy!

Reprinted with permission from Mountain Feed. Visit the EMB website to see our recipe for Savory Chicken Bone Broth.