It happened so suddenly. One moment we were looking forward to spring break, graduation celebrations and summer beach parties. Then, without much warning, it was all about hand washing, sheltering at home and frightening statistics.

Activities we love, activities that sustain this magazine—like dining out, beer and wine tasting, travel— vanished overnight. Scary times for any publication.

But we sprang into action, reporting through our weekly newsletter and social media about the closures, cancellations and ways to help our beloved food community survive—such as ordering to-go meals, shopping at farmers’ markets, supporting local fishermen and donating to the food banks.

As the lockdown dragged on, we began to notice people from all walks of life coming back to the values that Edible Monterey Bay has stood for since it was founded nine years ago—supporting our local community and paying close attention to where our food comes from.

Stuck at home, people joined CSAs, started baking and planted victory gardens. Out in the community, restaurants pivoted to takeout, chefs began selling meal kits, wineries offered virtual tastings, growers and distribution companies invented dozens of new schemes to get their products directly to consumers. Contactless, curbside pickup became the hot new selling point.

In a way the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a stress test on our local foodshed—challenging the ways food is produced, distributed and consumed. While the problems are far from over, we are in awe of all the ingenuity and collaboration that has emerged so far. And, once again, we are so very grateful to be living in a bountiful region where such a wide variety of fresh, healthy food is close at hand.

Did we pass the stress test? That remains to be seen.

But the stories in this issue demonstrate a great resilience in the local foodshed, which seems to be growing ever stronger in the Monterey Bay area despite the pandemic or maybe because of it, blossoming like the beautiful dahlia on our cover.

Our writers and photographers—who worked under unusual circumstances to produce this issue, using Zoom, wearing masks and observing social distancing—are proud to share stories about community-minded endeavors like the Back Alley Garden in Santa Cruz, Off The Hook in Hollister, the Secret Bakery in Salinas and the Cachagua General Store 3.0 in Carmel Valley.

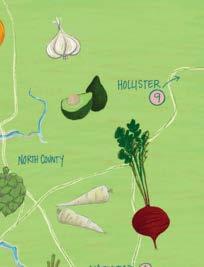

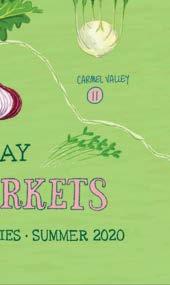

We want to take you behind the scenes at the regional farmers’ markets to meet the folks who have kept them going over the past difficult months.

We think you’ll enjoy reading about a new marriage of high-tech and local farming called EatLocal.Farm. And we invite you to do some armchair traveling with a collector of cannabis seeds from all over the world.

So take a break from the virtual world. Say goodbye to the computer screen for a while and enjoy holding this beautiful, tangible issue of Edible Monterey Bay in your hands. And please take a moment to appreciate all of the wonderful advertising partners who continue to sustain us in these uncertain times. Thank them with your business in a positive cycle of community support. We’re all in this together.

EDITOR AND PUBLISHER

Deborah Luhrman deborah@ediblemontereybay.com 831.600.8281

FOUNDERS Sarah Wood and Rob Fisher

COPY EDITOR Doresa Banning

LAYOUT & DESIGN Matthew Freeman and Tina Bossy-Freeman

AD DESIGNERS Zephyr Pfotenhauer Melissa Thoeny Designs

CONTRIBUTORS

Mark C. Anderson • Liz Birnbaum

Crystal Birns • Julie Cahill • Jordan Champagne

Jamie Collins • Maria Gaura • Margaux Gibbons

Maria Grusauskas • Coline LeConte • Michelle

Magdalena • Kathryn McKenzie • Laura Ness

Zephyr Pfotenhauer • Patrick Tregenza

Jessica Tunis • Amber Turpin • Sarah Wood

ADVERTISING SALES

ads@ediblemontereybay.com • 831.600.8281 Shelby Lambert shelby@ediblemontereybay.com Kate Robbins kate@ediblemontereybay.com Aga Simpson aga@ediblemontereybay.com

DISTRIBUTION MANAGER

Mick Freeman • 831.419.2975

CONTACT US:

Edible Monterey Bay P.O. Box 487 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 ediblemontereybay.com 831.600.8281 info@ediblemontereybay.com

Edible Monterey Bay is published quarterly. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used without written permission of the publisher. Subscriptions are $28 per year at ediblemontereybay.com. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our apologies and notify us. We also welcome letters to the above address. Thank you.

Deborah Luhrman Publisher

Composting

BY MARIA GAURA PHOTOGRAPHY BY CRYSTAL BIRNS

Located just steps from scenic West Cliff Drive, the view from Michelle Yahn’s front porch is phenomenal—wide ocean vistas punctuated by breaching whales and soaring pelicans. But when Yahn moved into her Santa Cruz home in 2008, the backyard was a different story. Behind the back fence, the public alleyway stretching from Modesto Avenue to Swanton Boulevard was piled with trash and choked with brambles, a magnet for illicit drinking and drug use.

Many people might have decided to lock the back gate, stay on the front porch and enjoy the view.

But Yahn is no front-porch sitter. She’s a guerilla gardener and composting evangelist, the kind of gal who sallies forth at dawn to pull weeds and plant flowers in neglected public areas. All those alleyway weeds could be composted, she thought, lots of that trash recycled. She threw open her back gate and assessed the situation.

“I found abandoned sawhorses, a couch, a jet ski overgrown with weeds,” she said. “There were vines everywhere and under the vines were layers and layers of trash. Chip bags and bottles, needles and hygiene products. It had to go.”

Armed with a shovel and a wheelbarrow, Yahn began exca-

She’s a guerilla gardener and composting evangelist, the kind of gal who sallies forth at dawn to pull weeds and plant flowers in neglected public areas.

vating trash and pulling weeds, clearing first the section behind her own fence, and then battling her way down the 1,000-footlong alley.

First on her hit list were the foxtails that lodged in her dogs’ ears, then the crabgrass, the rat-filled ivy, the wickedly thorny Himalayan blackberries. “I hacked through ivy roots as thick as my arm,” Yahn said. “It’s a workout; I’ve never needed to join a gym.”

In the early years, she’d come across teenagers surreptitiously smoking and drinking in the alleyway. “I’d walk up and say, ‘Hi, I’m Michelle! How are you?’” she said, demonstrating her greeting with a bright smile and a big laugh. “They stopped coming.”

Not all of the alleyway discoveries were bad. Yahn’s bushwhacking uncovered an archaeology of previous gardening efforts, including 15-foot-tall yucca plants, bananas, citrus trees and a sturdy little peach, all found struggling beneath thickets of ivy and blackberry.

The fruit trees are now thriving and the sawhorses, sporting a pink floral paint job, are used for traffic control during neighborhood block parties. And thanks to years of grit and inspiration, the entire length of the alleyway has been transformed into

a lovely linear garden.

“This is the opposite of an English garden,” said Yahn on a foggy May morning, as she unlatched her back gate to walk the alleyway with this visiting writer. Yahn, an actor and drama teacher, was kitted out for physical labor this day in dark pinstripe trousers, pink aviator shades and a pair of well-worn Australian work boots. A grey felt top hat, perched atop a mane of sun-streaked hair, added several inches to her petite frame. A sleeveless vest with a Grateful Dead emblem warded off the foggy breeze.

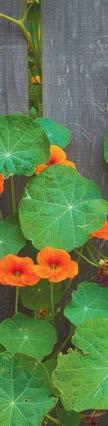

The Modesto Alley gardenway reflects a similar fun and eclectic style. The 15-foot-wide passage is bordered by tall wooden fences that provide reflected warmth while dampening the coastal winds. A narrow dirt pathway winds between shrubs, trees, flowerbeds and the occasional compost pile.

Nasturtium leaves the size of salad plates wave gently at hipheight, interspersed with a kaleidoscopic selection of plants. There are mint and squash, marguerites and Jerusalem sage, Peruvian lilies and camellia, bottlebrush and pelargoniums. Swags of rose blossoms and blazing bougainvillea sway from backyard fences, while fast-growing tree dahlias shoot towards the sky.

With a dramatic flair and a green thumb, Michelle Yahn has spent a decade building this hidden garden.

“This dirt used to be dead dirt,” Yahn said, poking at the dark earth with the toe of her boot. “You’d hold it in your hand and it would just blow away. Like a sandcastle.” Now, after years of composting, the soil feels springy underfoot, and drinks up rainfall like a sponge. Yahn’s good friend Lydia Neilsen, a permaculture landscaper and garden educator, comes once a week to contribute muscle power and expertise.

Most of the neighbors appreciate Yahn’s tireless work; some have unsealed their back gates and ventured out to plant the alleyway with vegetables and flowers of their own. One disgruntled neighbor objected to the composting element of the alley project, referring to Yahn as “the pile lady.”

The name makes Yahn giggle. “It’s a badge of honor,” she said. “And anyway, he moved.”

Years ago, while at a conference, Yahn had a chance conversation with an engaging fellow who turned out to be Yvon Chouinard, the founder and then-CEO of outdoor outfitter Patagonia.

“He said, work in your own neighborhood,” she recalled. “You can’t fight the mountaintop removal in West Virginia from your home in California. Work where you are. Activism is in your backyard.”

Yahn has embraced that approach, infusing environmental activism into her daily life of teaching, theater, parenting and neighborhood activities. At her wedding, Yahn gave guests a book on backyard composting. Now she offers reusable plates, jars, linens and silverware to party planners for free, preventing the needless use of disposable items. “I try to spread the word, make it simple enough for a third grader to understand. Don’t make trash. Compost. Use real stuff.”

Yahn intends to continue tending her gardens, but would love to reach a bigger audience with information about gardening, composting and harvesting rainwater. “Maybe a podcast? Online demonstrations? People want to grow food, and share food,” Yahn said. “I think there’s a lot of interest out there.”

Garden historian Mac Griswold famously called gardening “the slowest of the performing arts,” a sentiment Yahn emphatically agrees with. She gestured at the alleyway’s glorious springtime greenery, more than a decade’s work invested and still a work in progress. “I feel like I’m the director of this spectacular play.”

Maria Gaura is a lifelong writer, journalist and gardener. She lives in downtown Santa Cruz with her family, two elderly cats and an ambivalent garden that can’t decide if it wants to be a vegetable patch, a flower bed or a miniature orchard.

Chef Michael Jones on what makes a restaurant truly great STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY

BY MARK C. ANDERSONThere has always been something lurking behind the legendary outbursts chef Michael Jones is famous for: smashing a guest’s plate with a huge halibut backbone, targeting a diner with a fire extinguisher, calling the sheriff about a table at his own restaurant. That something is respect.

The guy who got the backbone crash was questioning the local sourcing of the Monterey Bay fish in Jones’ “home.” The fat cat who got retardant-blasted wouldn’t put out his cigar. The table of laggers knew full well it was past time to evacuate for a second seating at the now-closed Cachagua General Store.

In other words, respect for product, respect for others, respect for the rules of the game.

That all feeds into respect for what restaurants, done right, should be: one group of humans expending life force to take care of another, bringing joy via old-fashioned elbow grease. For Jones it’s a sacred agreement.

“You’re coming into my home,” he says. “I gotta take care of you. I will do the best I can, but you are in my home. Don’t yell at my people or make weird demands.”

And he knows how to take care of guests with plates and price points that are the stuff of local lore: think house-smoked wild salmon, incredible Corralitos sausage pizzas, oysters roasted with porcini cream and asiago cheese, served in very familial settings, as was the case with Cachagua General Store’s carnival-like Monday Night Dinners. Multiple courses and wine would run maybe $50 for two.

The “treat-you-like-family” refrain, on other chefs’ lips, might ring cliché. With Jones it’s what he seeks in the places he frequents, from the taco shop tucked in the back of Mi Tierra market in Seaside to la Balena’s celebrated organic Cali-Italian in Carmel.

“If you’re not creating the feeling that someone’s part of the family, if you’re not sharing something you’re personally invested in,” he says, “you’re just flipping burgers.”

I’ve talked about these things with Jones for 15 years. He’s been thinking about them since he started in kitchens back in college, though his Cornell training was in engineering. His Facebook followers get an articulate and entertaining torrent of the results, both food related and unrelated. Recent examples include thoughts on lack of drinking water on a Navajo reservation and why he rioted after the Kent State massacre. Eventually he circles back to “douche bag” bad actors in restaurants.

Award-winning Carmel Valley Ranch executive chef Tim Wood has known Jones for 20 years, and doesn’t want people to get too caught up in the rants when searching for Jones’ soul.

“He’s definitely a one-of-a-kind gonzo who’s pro any fight where a man is down,” Wood says. “If there’s an injustice happening, he tells people how he feels. But behind all the talk he has a huge heart. In the end he advocates for people who work their butts off.” Wood goes on to add Jones recently volunteered to drive food to furloughed employees on Wood’s staff.

Back in 2008, the last time a major crisis (The Great Recession) gripped the world, Jones told me, “So many chefs will do anything for people: burn arms, work until they break, work sick, drunk, whatever, in order to take care of a guest.”

“It’s part of our DNA,” he says. “People who are wired our way drift toward being chefs. Why else would you do it? It’s not for the money or the glory. The people not wired for it don’t last. Nobody that doesn’t have an open heart survives the selection process.”

Right about now, open hearts feel as important as ever.

“You just take care of people,” he tells me while driving to Soquel to deliver food to a chef’s kid who is isolated and unable to leave his home. “It comes back around.”

One real way it returns for him, on a daily basis, is in the reactions to the latest iteration of Cachagua General Store.

He’s using Massa’s tasting room (formerly Heller Estate) in Carmel Valley Village to prepare prodigious value, dished out the back door. CGS 3.0 (or is it 5.0?) includes pickup or delivery bargains like Wilson Ranch spring lamb at $8 per serving, nearly 2 pounds of cashew and cumin-crusted pork loin for $10 and Nobu-style marinated fresh local rockfish at $8 a pound. We’re talking Michelin star quality at swap meet prices to help people get through. (Rotating menus and delivery updates appear on CGS’s Facebook page.)

“It’s just that life is supposed to be about joy,” he says. “And we do it through food.”

The guy is rarely speechless, but when I compare high investment/ limited return service occupations like journalism and restaurants, he goes quiet. Eventually he agrees they’re not just a job, they’re both a benediction and affliction.

“It’s a privilege to experience people’s happiness when they get great food, even when it’s another 9am–9pm day and the refrigeration went down,” he says. “There are so many rewards, like the look on the face of an 87-year-old lady whose son hooked her up with some of our food for Mother’s Day.”

In the face of widespread suffering, he counts blessings, including people renewing an admiration for the craft to which he’s dedicated.

“For one thing, people are cooking at home and realizing it’s hard,” he says. “They’re beginning to see the rewards too and finding a sense of pride—‘I made something beautiful’—and have a whole lot more appreciation for restaurants and service.”

Not that all restaurants will return whenever this tunnel finds the light. “The only guys left around will be the ones who like it—like me, this is what I do, it’s not really a choice,” he adds. “You can’t wake up in the morning and decide to be really into serving people any more than you can wake up and decide to be African-American.

“If the owner isn’t on site with a longtime chef or something similar, they’re not going to make it.”

In other words, those for whom it’s not just about food will remain, because it’s simply what they do. Which is something you gotta respect.

Mark C. Anderson is a roving writer, editor and entrepreneur loosely based in Monterey County. Follow and/or reach him on Twitter and Instagram via @MontereyMCA.

“If you’re not sharing something you’re personally invested in, you’re just flipping burgers.”

G&B Organics soils and fertilizers are made from high-quality ingredients that are people, pet, and planet safe.

Available ONLY at independent garden centers

Aptos Landscape Supply

5025 Freedom Blvd. Aptos, CA 95003 (831) 688-6211

Bokay Nursery 30 Hitchcock Road Salinas, CA 93908 (831) 455-1868

Del Rey Oaks Gardens 899 Rosita Rd. Del Rey Oaks, CA 93940 (831) 920-1231

Drought Resistant Nursery 850 Park Ave. Monterey, CA 93940 (831) 375-2120

Far West Nursery 2669 Mattison Lane Santa Cruz, CA 95062 (831) 476-8866

The Garden Company 2218 Mission St. Santa Cruz, CA 95060 (831) 429-8424

Griggs Nursery 9220 Carmel Valley Rd. Carmel, CA 93923 (831) 626-0680

Hidden Gardens Nursery

7765 Soquel Dr. Aptos, CA 95003 (831) 688-7011

M. J. Murphy Lumber

10 W. Carmel Valley Rd. Carmel Valley, CA 93924 (831) 659-2291

Martins’ Irrigation

420 Olympia Ave. Seaside, CA 93955 (831) 394-4106

McShane’s Landscape Supply

115 Monterey Salinas Hwy Salinas, CA 93908 (831) 455-1369

Mountain Feed & Farm 9550 Highway 9 Ben Lomond, CA 95005 (831) 336-8876

The Plant Works 7945 Highway 9 Ben Lomond, CA 95005 (831) 336-2212

San Lorenzo Garden Center

235 River St. Santa Cruz , CA 95060 (831) 423-0223

Scarborough Gardens

33 El Pueblo Rd. Scotts Valley, CA 95066 (831) 438-4106

Seaside Garden Center 1177 San Pablo Ave. Seaside, CA 93955 (831) 393-0400

Valley Hills Nursery 7440 Carmel Valley Rd. Carmel, CA 93923 (831) 624-3482

BY KATHRYN MCKENZIE PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHELLE MAGDALENA

BY KATHRYN MCKENZIE PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHELLE MAGDALENA

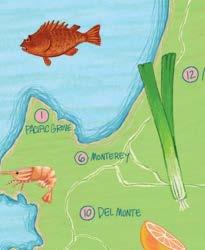

To hear Corina Gitmed and Sara Spencer tell it, destiny brought them together and the universe continues to guide their way through a complicated landscape. Somehow, they say, this was all meant to be.

The two entrepreneurs have family connections in the Moss Landing fishing community and are working to eventually be allowed to buy fish directly from the boats.

Despite the fact that the coronavirus pandemic has been devastating for so many food producers, Gitmed and Spencer have adapted and are thriving. With a demand for healthy foods delivered to people’s doors, their company Off The Hook Essentials is now doing a brisk business as a CSF (community supported fishery), bringing sustainably caught seafood directly to their customers in San Benito County and beyond.

“You have to trust the journey,” says Spencer, an Aptos resident and essential oils educator. “Everything has worked out for us.”

At first glance, Off The Hook’s mix of seafood and essential oil infused salts seem like an unusual pairing, but Gitmed and Spencer have brought their passions together—Gitmed’s quest to provide a source of sustainable seafood for her home area, and Spencer’s to spread the gospel of healthy essential oils.

They’ve been selling fresh fish at the Hollister Farmers’ Market as well as their all-natural dry brine and finishing salts that add a special zip to all kinds of recipes in addition to seafood. But when that farmers’ market closed due to the COVID-19 crisis, Off The Hook pivoted to its current delivery service.

Gitmed and Spencer met several years ago when Spencer was teaching an essential oils workshop at a mutual friend’s home. The two moms hit it off instantly and began collaborating. Their first major

Hawaiian sea salt infused with flavors. The Citrus blend, for instance, uses orange, lemon and lime, while Thai combines lemongrass and basil and Pico de Gallo is a mix of black pepper, cilantro and lime.

Gitmed has made it her mission to provide fresh seafood to her hometown of Hollister and the surrounding area. It’s part of a longtime tradition that she’s proud to carry on. Her father treated fishing as a family activity and lived just down the street from Louie Freitas: “His lineage is legendary in the commercial fishermen industry,” says Gitmed, with Freitas’ boat, The Pancho, part of the harbor scene in Moss Landing for many years.

“I remember playing with his daughter in the front yard while Louie got his crab pots ready for the season,” says Gitmed. “The man still goes out every day! It’s just something I’ve always been around.”

As an adult, Gitmed realized there was a pressing need for fresh local seafood, and she developed the idea to sell at the farmers’ market. “I envisioned always getting our fish from The Pancho, however, state law and permitting was always an obstacle,” she says. She and Spencer are still working their way toward getting the necessary permits to buy fish directly from the boats, a lengthy and time-consuming process that Gitmed compares to “jumping through six hoops of fire.”

For now, they buy from seafood wholesaler Pacific Harvest in San

step forward came when a grocery store district manager visited their farmers’ market stand and became entranced by their salts. As a result, Off The Hook infused salts are now being carried by regional Safeway stores, and Spencer and Gitmed are also working to get these products into independent markets and other mom-and-pop businesses.

Another important connection came about when they met Becky Herbert of Farmhouse Foods/Eat With The Seasons, who manages her family’s CSA and had recently opened the Farmhouse Café in downtown Hollister. Gitmed and Spencer were initially café customers, then became friends with the staff and Herbert, who allowed them to set up their farmers’ market stand in front of the restaurant.

Spencer suggested that Off The Hook products might be something Herbert’s CSA customers would be interested in and Eat With The Seasons began offering this option. Now Eat With The Seasons customers from around the Bay Area and the Monterey Bay can also order Off The Hook seafood and salt selections.

Off The Hook’s infused salts and sugars are also being used by other food purveyors to create unique and creative goodies, such as Heritage Chocolates in Corralitos, which uses them for its toppings. “It’s all about community and collaboration,” says Spencer.

Each of the Off The Hook salt varieties is a mineral-dense combination of Mediterranean sea salt, Himalayan salt, and red and black

Juan Bautista and process the fish themselves at a friend’s butcher shop, where they portion it out and then flash-freeze it for optimum freshness. One of their primary considerations is providing the very freshest but also sustainably harvested seafood for their customers, and they work with the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch to ensure they’re making the best choices.

Customers order through the Off The Hook Essentials website and Gitmed and Spencer personally deliver each order to people’s homes. It’s opened up a whole new customer base for their company and people appreciate the convenience. Gitmed and Spencer are also able to give their customers details on how the fish were harvested.

Their ultimate goal is a zero-waste business supplying sustainably caught seafood that supports the local fishing industry. And although they acknowledge they’re still a little way from that, they’re on the right path.

Gitmed says she and Spencer are excited about the growth and potential for their business.

“It’s great to be doing what we’ve done thus far. Timing is everything. The COVID-19 experience has helped us and guided us…people and our community trust what we’re going to do is good for them.”

Gitmed has made it her mission to provide fresh seafood to her hometown of Hollister and the surrounding area.

BY KATHRYN MCKENZIE PHOTOGRAPHY BY PATRICK TREGENZA

BY KATHRYN MCKENZIE PHOTOGRAPHY BY PATRICK TREGENZA

In the Italian city of Florence, secret bakeries are a longstanding tradition. Hundreds of home bakers supply the city’s cafés, and locals in the know wait outside these clandestine bakeries in the early morning hours to grab a fresh, hot-from-the-oven pastry.

Andrew McClelland didn’t set out to have a secret bakery of his own, but the twists and turns of the past six months have led him down this path. Now, at his home in South Salinas, he produces hundreds of loaves of rustic sourdough and whole grain breads, as well as pastries, croissants and more each week.

People order his breads online, pay in advance and then pick up at a table outside his house twice a week—contactless and convenient.

“I’m probably doing too many loaves for my own good,” says McClelland with a chuckle. He notes that baking, even in the comfort of one’s own home, is demanding work with extremely long hours.

His passion for what he does lifts him above that, though, and there is a constant creative outpouring of new offerings, like his chocolate cherry rye loaves, artichoke and ricotta-filled croissants and rosemary brioche burger buns, to name just a few. He even makes handcrafted sourdough dog biscuits.

For McClelland, the Secret Bakery is a return to some of his favorite things—baking and being in the kitchen. He has been a dedicated home baker for several decades, long before quarantine sourdough was a thing. At the same time, it’s a chance to fill a hole in local artisan food culture. Few Monterey Bay area bakeries specialize in breads, and there was none to be found in Salinas.

“I’ve always been a food person at heart,” says McClelland, who began working for restaurants as a teen in his native Toronto. He then made his mark in the corporate world for many years, pioneering the

California’s Cottage Food Law allows the sale of baked goods from home kitchens, along with other low-risk foods, like jams and pickles.

first chopped bagged salads for Fresh Express and other readyto-eat products for Dole and Taylor Farms. More recently, he was general manager at the Carmel Valley farm stand of Earthbound Farm, which he helmed for about a year.

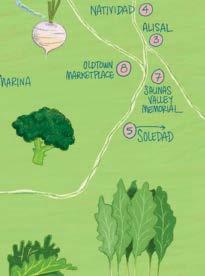

McClelland still consults for ag companies, but the dearth of good sourdough bread in the region continued to nag at him. Last year he became intrigued with the idea of having his own bakery, even looking at potential spaces, and also began baking and selling breads at the Oldtown Salinas Farmers’ Market at the beginning of 2020. “I quickly started selling out,” he says. “I had very happy customers.”

But then the COVID-19 pandemic came along and he opted to pull out of the farmers’ market—at least for now— and sell from home, with the help of daughter Rhylae, whose regular job as an event planner was impacted by the pandemic. Rhylae built the Secret Bakery website and manages its social media.

“She’s been amazing and I’ve hired her part-time,” says McClelland. “She’s now launching out on her own by consulting to other bootstrapping startup brands.”

McClelland has always felt drawn to hearth breads, especially sourdough. He’s been inspired by great bakers like Joe Ortiz and Nancy Silverton, as well as Peter Reinhart, author of The Bread Baker’s Apprentice: Mastering the Art of Extraordinary Bread and Brother Juniper’s Bread Book.

To McClelland, great bread is all in the details: the right kinds of flour, hand mixing and shaping, slow fermentation, a perfectly caramelized crust and an airy moist crumb. His breads are naturally leavened, a process that he believes is enhanced by his use of organic flour.

He sources his ingredients locally whenever possible, using wheat from Coke Farm in San Juan Bautista, which he mills himself, along with freshly milled flour from Oregon. Hearty whole grains are his passion, with loaves like San Benito Sesame Whole Wheat, Double Fermented Scottish Oat, Country Sour Boule and whole wheat ba-

For a lone baker to have this kind of output seems amazing, especially when you consider it’s all done from home. McClelland has designated an extra room in his house for baking supplies and uses a Belgian oven that he describes as being made for “serious home bakers,” holding nine to 12 loaves at a time.

For now, McClelland is going with the flow and seeing where his business will take him. He’s thankful to be able to stay home and still make his customers happy with his freshly baked offerings.

“Will I ever have a storefront? Who knows?” he says. “I love what I’m doing.”

Kathryn McKenzie, who grew up in Santa Cruz and now lives on a Christmas tree farm in North Monterey County, writes about sustainable living, home design and health for numerous publications and websites.

Secret Bakery secretbakeryshh.com 831.540.5023

Who doesn’t love the smell of lavender and the instant relaxation one gets when instinctively squeezing the flowers between your fingers or breathing in its essential oil? Not only is lavender great for calming the nerves, it also is a drought resistant plant and a magnet for bees—that can extract pollen and nectar throughout the summer, even when other flowers are no longer blooming. When I first saw my home farm, I imagined the driveway and walkways lined with lavender and now, a decade later, I am so happy I made that choice because butterflies hover about while the hummingbirds dart from plant to plant, and the bees, attracted by the sweet scent of lavender, help pollinate my orchard.

Lavender (botanic genus Lavandula) is in the mint family and includes 47 different species that thrive in temperate climates. Lavender is grown as an ornamental plant, for culinary purposes and for essential oils. Lavandula angustifolia—otherwise known as English lavender—is the most cultivated culinary variety and contains the highest quality oils with less of a camphor profile.

French lavender includes Lavandula stoechas, the type with the fatter flower bud and a few open flowers on the top that range from pink to purple, and Lavandula dentata, a wooly leaf variety. French lavender has a lighter scent than English, more reminiscent of rosemary with earthy and rich undertones.

Drought and deer resistant, lavender requires very little maintenance with the exception of shearing off dead flowers and part of the plant once a year to stimulate new growth. Typically lavender has a long summer bloom and some varieties of English lavender bloom twice a year, and if the blooms are not harvested, they can remain on the plant almost year-round!

Flower farmer Amanda Seely, of Laughin’ Gal Floral, grows three kinds of lavender on her fifth generation 1920s farmstead in Aromas. In her work as a wedding flower designer, she loves to sneak lavender in the back of her brides’ bouquets so they can take a deep breath and ease their nerves on their wedding day. Her favorite is the munstead variety because of its low, compact growing habit and dark purple florets. She loves provençal for culinary purposes and grows sweet lavender Lavandula heterophylla because it blooms year-round.

Lavender can be grown from seed but almost no one chooses to do that due to the germination time—it can take up to six months. You are better off buying a plant at a nursery as they are reasonably priced, or making cuttings from a cultivar you like. If you want to take cuttings, it is best to take them in the summer. Take short 3–4-inch pieces of the soft, pliable growth that comes off the woody stem. Cut each piece with a sharp knife, dip them in rooting hormone and nestle them into a propagation mix that is good for rooting cuttings. Typically propagation medium consists of sand, perlite, coir peat and compost. Cuttings should be watered and kept humid either by using a mini-greenhouse (basically a 2-inch seedling flat with a lid) or place a plastic bag with some holes over each pot.

Each lavender variety has a different spacing requirement. Larger varieties need to be planted 2–3 feet apart. Others, like munstead, can be planted a foot apart.

Lavender thrives in full sun and well-drained sandy soil, and is great for hillside erosion control. You can grow lavender where you can’t grow other things very well as it will even thrive in rocky soil devoid of nutrients. Unless you live in a really hot area, watering lavender is only necessary while plants are getting established, for the first year or so.

When you do water, it is best to do a deep and thorough watering when the plant is dry. You can plant lavender any time of year, but I like to plant it in winter or early spring so that seasonal rainfall can take care of most of its watering needs.

Harvest lavender as soon as the blossoms become a vibrant color—whether they are shades of purple, blue, pink or white—that is when the fragrance is the strongest. Store in a cool, dry place until you are ready to use. Or dry in bunches upside down so that stems dry straight, then pack or process. Sunlight will fade blooms and dust can accumulate on drying bunches if left to hang too long and the scent dissipates if not packed properly. You would not want to use these for culinary purposes.

Each year in early spring or fall, after the flowers have been harvested or are dried, take

“It’s such a sensory experience, the way it fills the kitchen with a nice soothing scent.”Carmel Valley Ranch executive pastry chef Tanya Matta has her pick of more than 7,000 lavender plants growing on the ranch property.

pruning shears and cut off all old flowers and some of the leaves. I like to use electric shears and make short work of it, making round mounds. The trick is to cut back most new growth. For low growing lavender varieties, trim back the foliage 1–2 inches. For vigorous varieties that grow 3–4 feet high, trim them back by one-third of their growth so they don’t get overly woody. If they are woody, prune out the middle and remove the oldest branches. Even though lavender is a hardy perennial, it does become more woody over time, leading to shorter flowers and less foliage. You will need to replant every five to 10 years in order to have healthy plants.

Lavender has a slightly sweet, floral flavor. The flower buds can be infused and added to many dishes, but the key is to use only a small amount for the flavor to be subtle. For culinary purposes, be sure to use the English variety, as other varieties have a high camphor content that is strong and can be off-putting.

If you purchase lavender petals, please be sure to only use those sold for culinary lavender in edible dishes. Some sold for potpourri may be treated with chemicals. It is best to strip the blooms from homegrown plants, if at all possible. Or purchase from a local farmer or a reputable medicinal herb grower.

Infusing is one of the best methods for making lavender syrup or adding to whipped cream for topping fresh berries.

If you are infusing for a simple syrup, you need 1 cup of sugar per 1 cup of water. Boil water on stove and stir in sugar until completely dissolved. Add 2 tablespoons of lavender buds to the boiling water and boil for 1 minute. Remove from heat and let steep for 30 minutes. Strain out lavender and cool. Use it to make lavender lemonade mimosas or, my favorite, a Lavender Collins! Just mix a little of the lavender syrup with gin, lemon juice and sparkling water. Lavender syrup goes great with most all clear spirits.

To infuse whipped cream, heat cream on stovetop until simmering, then remove from heat. Add 1½ teaspoons of lavender flowers to the cream (adding 1 teaspoon of fresh mint also pairs well). Strain lavender from the cream after 20 minutes. Cool in refrigerator for 8 hours before whipping.

Lavender shines when paired with lemon and lemon zest. Try making an Earl Grey teainfused pound cake or cookies with a lemon lavender frosting.

Often I add dried lavender to a jar of honey and forget about it on the shelf for a few months, then drizzle it over some soft sheep or goat cheese on a cheese platter.

Lavender can also be added to berry jams and jellies; the best combinations are blackberry or blueberry.

Lavender is sometimes part of the mix in Herbes de Provence, along with traditional French herbs such as dried marjoram, basil, tarragon, savory, thyme, rosemary, basil, fennel and sage. I like using Herbes de Provence in quiches or frittatas. This mix is also great on grilled chicken, lamb or fish or in stews and soups.

Lavender, rosemary, crushed pink or black peppercorns and coarse sea salt would also be a great dry rub for roasts. You can add brown sugar and chili peppers to give it a sweet spicy flavor. This would be great on a lamb leg or beef roast.

I love to add lavender salts to roasted Japanese sweet potatoes, the ones with the white flesh and purple skin and that have a very floral flavor profile. Lavender brings out the floral notes in the potatoes.

French lavender has a high concentration of linalyl acetate which is good for relieving inflammation and pain while killing some bacteria. If you have minor skin lacerations or pain, you can apply the oil.

English lavender tea can soothe the stomach, alleviate stress and anxiety and help you sleep easier. It can also ease a headache when applied to the temples or when a few drops are rubbed together in your hands and inhaled.

Try adding a few drops to your hand sanitizer to keep calm during these unprecedented times.

Jamie Collins is the owner of Serendipity Farms and attends all of the Santa Cruz Community Farmers’ Markets, where you can find her fresh organic fruit, vegetables and nutrient-dense prepared food items.

Courtesy Tanya Matta, executive pastry chef, Carmel Valley Ranch

Courtesy Tanya Matta, executive pastry chef, Carmel Valley Ranch

Lavender puts on a show every summer on farms and ranches from Bonny Doon to Big Sur. The grounds at Carmel Valley Ranch, for example, turn bright purple thanks to more than 7,000 lavender plants that line driveways and cover hillsides. Those fragrant flowers provide plenty of inspiration for executive pastry chef Tanya Matta, who loves cooking with it.

“It’s such a sensory experience, the way it fills the kitchen with a nice soothing scent,” says Matta, who uses it not only in scones and cookies, but also in her Vanilla-Lavender Panna Cotta.

“It’s a flavor that combines well with honey and dark berries and chocolate too, but you need to be frugal with it,” she advises. “Start with a little, you can always add more.”

Matta—who studied to become a ballerina and then an urban planner—started baking as a way to relieve stress and found that her real passion was in the kitchen. “There’s a discipline to pastry and the creativity that really appealed to me as a dancer,” she adds.

Before coming to Carmel Valley Ranch in 2018, Matta worked with her mentor Claudia Fleming at the famed Gramercy Tavern in New York City and has worked at fine dining restaurants in Vail, Colo. and her home town, Durham, N.C. Over the past several months, while sheltering in place at her home in Pacific Grove, she has been sharing her baking expertise on Instagram. Look for her videos here: @tanyaalexandramatta

14 ounces all purpose flour

13 ounces cake flour

4 ounces confectioners sugar

3 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons baking powder

1 teaspoon kosher salt

9 ounces unsalted butter, cold, cubed

2 to 3 tablespoons dried lavender buds

2 eggs ¾ cup cream

¾ cup orange juice

Preheat oven to 325° F for a convection oven or 350° F for a regular oven.

Place all dr y ingredients plus cubed butter in bowl of an electric mixer. Using a paddle attachment, mix on medium-low speed until butter is pea sized

Combine all wet ingredients and add all to the dr y ingredients Mix until all ingredients are combined. Transfer dough to lightly floured sur face and roll to

approximately ¾-inch thickness (if making mini-scones, roll out thinner)

Cut scones in desired shape. At this point, scones can be chilled overnight and baked in the morning or you can cut and bake right away

To bake, place on parchment-lined sheet pan about 2 inches apart. Brush with egg wash mixture (I like using egg yolk and a little bit of water to thin it out) Sprink le with raw sugar and bake for about 15–20 minutes or until golden on top.

If there are any leftover scones, they can be wrapped in plastic wrap. They are good the next day, but need to be warmed to be fully enjoyed. Yields 1 dozen.

One of the main reasons we love farmers’ markets is the direct interaction we get with the human beings who grow our food. We preach this idea to our kids, to our colleagues, to the choir here in this organic community surrounding the Monterey Bay. The slogan, “Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food,” is practically old hat to us. We are big fans of shaking our farmers’ soil-caked hands.

Then a pandemic happens. In a matter of hours, we are faced with a new reality, an extreme limit on our contact with others, including the farmers. And certainly no more handshakes. For those of us who gather the bulk of our grocery list from farmers’ markets, it has been a frightening time, almost paralyzing. Yet, in the first hours of shelter in place, certain folks began a marathon of work, tirelessly arguing to the powers that be that we needed our farmers’ markets, and that they should be deemed “essential services.” The managers and directors of our local markets—often people who go unrecognized—are still at it behind the scenes, pushing with all their might to make sure we can get our local food.

Santa

Nesh Dhillon, long-time manager of all the Santa Cruz Community Farmers’ Markets, was in Mexico when his phone started ringing with news of the shelter in place order. He was at his remote plot in Baja, California, with very limited Wi-Fi service, when Santa Cruz economic development director Bonnie Lipscomb called seeking his input for meetings of the emergency COVID-19 task force. For three days straight they texted and called each other via WhatsApp, the only method to connect at the property in Mexico.

Then he returned home and hit the ground running, grateful that the markets had been deemed “essential services,” thanks in no small part to his own lobbying efforts. “I told the City Manager: How does it make

sense to decrease the food supply? You want to decentralize it, diversify it. Let’s be logical about this!” Dhillon explains.

With so many new systems to figure out, the first few weeks of shelter in place were extremely difficult, and public complaints, mostly indirectly on social media, were just another exhausting fire to put out. “Week one was really intense, week two a little less intense, by week four there were no complaints. Basically within three weeks we had developed our protocols. I literally had to work with every vendor individually to maximize public health and social distancing to eliminate risk,” he says. “It is a lot of work to eliminate direct hand-to-hand sales.”

Dhillon and his team are continuing to look for creative and outsidethe-box solutions to these unprecedented and challenging times. For example, when the mask ordinance came out, Dhillon predicted correctly that customers would still show up without a face covering. So he ordered a ton of crafty, homemade masks and just gave them away for free, to remedy the public health risk.

They have also developed a curbside pickup option for customers at the flagship Downtown Santa Cruz market, where farmers offer prepackaged boxes of produce and customers can order and pay ahead online. The system is a precursor to another idea that has been brewing for a while, a produce delivery system for folks who might be physically unable to get to the market.

Dhillon says that despite the hurdles, there have been some great, positive elements coming out of the pandemic. “It’s the silver lining to COVID-19. There’s a lot of great stuff happening right now even though it’s pretty dire for a lot of folks. A lot of innovation,” he says. “Restaurants are coming to me with killer ideas for value added products and they are doing really well.” He lists examples, like Home doing charcuterie, Feel Good Foods doing fam-

Farmers’ market managers keep the fresh produce flowing (clockwise from top left) Nesh Dhillon, Catherine Barr, Reid Norris, Jerry Lami.

Farmers’ markets have spread out and started new safety protocols so shoppers can maintain social distancing.

ily meal boxes, chef Anthony Kresge from Belly Goat doing burger boxes, Soif and La Posta doing dried pasta and even Freddy the Forager bringing his mystical, legendary goods to sell at the market. None of this would have happened during “normal” times.

But for Dhillon, the big picture is very clear, and he is anxious to address it. “When are we going to have a national discussion about food security? How much food is being produced overseas? A ton. A serious amount. Is that really in our best interest? Is that logical? We need to start talking about that on a national level, and the economic impact of that. We can glorify farming again! That’s the big discussion that needs to start happening right now because people are paying attention to where their food is coming from.”

The thing about operating a farmers’ market is that it is very dependent on property owners and institutions that provide the venue for it. Catherine Barr, manager of the Monterey Bay Certified Farmers’ Markets, had a strong link to the Monterey Peninsula College for its weekly market on Fridays. But as we well know, all schools have had to close, including MPC. This was a huge blow to Barr, who had to hustle to shift the market at risk of closing it down. When asked what the hardest part about COVID-19 has been for her, she says, “Where should I start? I think the biggest hurdle was having to move the MPC market over to Del Monte Shopping Center during COVID-19. At this time MPC will not allow us to set up the market while the campus is closed. If it wasn’t for Karla Corres and Denae DiBenedetto from Del Monte reaching out to our organization, I don’t know what we would have done.”

Of course, that market move is just one of the many changes Barr has had to grapple with. Opening of her seasonal markets at The Barnyard and the Del Monte Center had to be delayed. And on the precipice of launching a new, highly anticipated market in Pacific Grove, Barr had to make the call of cancelling it. “Pacific Grove has been scratched for now...with all this going on, no way can anything happen for this year,” she laments.

Yet she sees the positive within the hurdles of the pandemic and says that customers have been extremely loyal, moving without complaint to a new venue, and continuing to support the vendors who are able to sell their goods, thanks to Barr for keeping the markets operating. “We have seen new customers as well, who don’t necessarily want to go inside a grocery store to buy food. They like the new setup,” she adds.

And the big picture remains for Barr, who has been doing this job for 28 years. “Coming from a farming background, I get how hard these farmers work to bring food to your table. Interacting with the farmers

and seeing the third and fourth generations taking over the family business...it’s exciting to see what the next generation is coming up with to improve crops and marketing at the farmers’ markets.”

One of the major tenets behind Everyone’s Harvest is serving the surrounding community by promoting health and nutrition. For executive director Reid Norris the shock of shelter in place was incredibly challenging. But he says that “the most important thing for us is to keep the markets and our employees and customers as safe as possible so we can continue to fulfill our mission and get healthy food to people in our community who need it most right now.”

Staying safe came in the form of a Social Distancing Plan, made up of best practices developed in close collaboration between the health department, local governments and other market organizations. Yet, Norris says, “It’s still a really anxious time for essential businesses like ours whose employees and partners are out serving the public, and for everyone who’s trying to figure out how to operate sustainably at a time when the economy is in shock and the loan programs created by the government are overwhelmed and, so far, unresponsive.”

In addition, Everyone’s Harvest has launched a personal shopper service at the Marina and Pacific Grove markets, a very convenient option

for folks to get fresh produce and other goods. It uses an online, pre-order format, in which customers select items, a price point and time slot, then a customized box of produce is assembled for pickup.

Everyone’s Harvest is also the only market group in Monterey County that offers Market Match, the program that doubles EBT and CalFresh spending for market produce. Norris says, “It’s been so great to see this program continue to thrive at this time. I wish everybody knew about Market Match, because it’s accessible to any family who shops with a CalFresh card, and 100% of the Match supports local farmers.”

Everyone’s Harvest’s regular market season would have offered cooking workshops led by local chefs for families to learn about cooking with local produce, but they are unable to host these during COVID-19 times. However, Norris says they are exploring alternate ways to bring these workshops to market or get them out to us virtually.

Amidst the struggles and intense logistical juggling, Norris has been able to reflect on the work his organization does, celebrating victories like the June re-opening and 10th anniversary of the market at the Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System. “Any time you go through a challenge like this you learn more about yourself and you grow closer as a community. Being a small nonprofit or small business is always incredibly hard work, but it’s so worth it to see the positive impact you can have on the health and lives of people you work with and care about,” he says.

Jerry Lami, manager of the large network of West Coast Farmers’ Markets, got his start in a supermarket. He never imagined he would be managing farmers’ markets in six different counties, acting as a go-between for farmers, food producers and county governments.

“I have a lot of satisfaction in the dozen or so markets that I run, in that I employ 300–400 vendors, cut out the middleman, give them an opportunity to sell what they grow and create an opportunity for them to make a living,” he says.

But that opportunity was drastically cut when COVID-19 hit, especially in locations with strict regulations concerning who could still sell goods at the farmers’ market. He says that Monterey County, in particular, has been tough because it halted all on-site cooking and hot food vendors. His Carmel Valley market had 30 vendors and was reduced to 14, while Oldtown Salinas had 35 and is now down to 12. “More than 60% of the vendors were eliminated by restrictions put on by Monterey County. I was forced to close four of my markets,” he says regrettably.

Despite the restrictions, he has been impressed by those who are still present at the market, “the resilience of my farmers that keep coming and keep trying despite that their sales have probably dropped about 90%. The hope that they will survive at all is that customers will remember them and keep buying from them.”

Lami also says that customer feedback has been very positive. “They like that we are still allowed to have packaged foods, like hummus. They like the ability to be able to shop in the open air. I think that it’d be a lot better if the restrictions weren’t so tough in Monterey County, but I guess having some vendors is better than none.”

Ultimately, his hope is that “the heat of the summer will kill off the virus and we can all go back to work and things will just go back to the way it used to be. I personally feel that farmers’ markets are in a good position, being outdoors, and we have the opportunity to be healthier and safer.”

Amber Turpin is a freelance food and travel writer based in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

200

Any time you go through a challenge like this you learn more about yourself and you grow closer as a community

Resilience. Roll the word around in your mind or your mouth, tasting iron, or earth, or a springy loaf fresh from the oven. Look out the window and see it in action; your neighbor making masks to pass out to strangers, curbside pickups from local stores, or the efforts of protesters who march for justice and wield brooms to clean the streets the next day. Resilience is elastic, stretching and bouncing back, adapting to changed conditions. It’s a touch word for our times.

Resilience implies a struggle or a problem to overcome. It is through struggle that we are tested and through this struggle that we realize what we are capable of. This is just the beginning of changes that will reverberate for generations. Here we are in it, all together, reaching out and breaking down and getting it back together, donating to causes we support, wearing masks, trading sourdough cultures and trying not to touch our faces.

Americans are reckoning, perhaps for the first time, with shortages of basic necessities: toilet paper, eggs, flour. Many of us have never had to wait in line to be allowed inside a grocery store or had limits on how much we could purchase. And while it has been disconcerting, this aspect at least reminds us that in much of the world and throughout much of history, this was the norm and not the exception. American exceptionalism is over; some might argue that it never existed.

In any case, if we have had to adjust to new, uncomfortable changes, we are not alone. While the devastation that this virus has wreaked is real and not to be dismissed with platitudes, it has not been without its lessons. It is perhaps in poor taste to talk of silver linings, when so many are facing great loss — loved ones, businesses, jobs and more. So we will not use that term. But we will speak of lessons that we have learned and skills that we have remembered, that have been hidden or buried like potatoes in the ground; humble, grounded truths that can serve us long after this virus has passed.

We are being constantly reminded what community is and how to sacrifice for and take care of each other. We are being reminded of the value of jobs and persons that our current system does not honor or compensate fully enough. Grocery and postal workers are heroes in this time, as are the bent-backed laborers in the fields of our fertile farmland. Their work has always been vital and meaningful. May we remember it when our current troubles have resolved, and treat them accordingly, and vote in ways that will support their basic dignity.

Farmers have always been resilient, adaptable folks. Each year begins anew, with too much rain or not enough, with rising rent and falling prices, storms, blight and a shifting climate. It has never been an easy undertaking, although in these times, when many restaurants have been shuttered and people’s shopping habits have changed overnight, the

work of farming seems less certain than ever. But many local farms have risen to the challenge by shifting their businesses almost overnight, using everything from CSA models to farm stands to pop-up sales announced on social media to get their produce onto the plates of hungry people.

The big supply chains are faltering and the artificially low, subsidized price of mass-produced food has risen. But the local food system is nimbler, better able to adapt in real time to the vagaries of the market and the current situation, and its value is unmistakable. If ever there was a time to shop at the farmers’ market, or go in with another family on a half a steer, or to reduce your reliance on packaged food, this is that moment.

This is a time to examine our habits of consumption and make choices that better reflect the world we want to inhabit. The streets are less crowded, the birdsong more audible. The morning air is clear and full of possibility. Breathe it in, before you slip the mask over your face. The clear air of a world in which much has been lost, but much might be created anew. Embracing the opportunities for growth and change as we move through and recover from this pandemic is the work we all must do, to build a more resilient world.

Like dough that stretches as we knead and knead. Like potatoes in the ground. Like warm eggs lifted from the nest of a backyard hen. Resilience in all its forms has always been a basic quality of life on earth. Let us not be dinosaurs, trapped when our old way of life becomes unsustainable. Let us be farmers, sowing the seeds of the world we want to live in. We’ll keep a weather eye on the storm clouds and make sure our neighbors are fed. In the oven, the bread is rising. Resilient.

Sharing a passion for organic agriculture and an entrepreneurial spirit, Kimberly Null, her husband Nick de Sieyes and Ethan Rublee had been talking for months about a way to apply technology to the local food system. Then the pandemic hit and within about a week their virtual farm stand EatLocal.Farm went live.

The three met last fall at the Santa Cruz Montessori School where their children are enrolled. “This started before COVID. Nick and Ethan were talking on a school camping trip about how to apply Ethan’s tech savvy and knowledge of networks and tech apps to agriculture,” says Null, who together with Nick’s sister Jamie tends an 8-acre olive orchard in Aptos and produces Wild Poppies Olive Oil.

Typically, small farmers lack the infrastructure to sell directly to consumers, except at farmers’ markets. With COVID-19, as restaurants closed and corporate outlets dried up overnight, vendors suddenly had excess production. Under lockdown, consumers—even those who formerly frequented farmers’ markets—flocked to CSAs, which filled up immediately. That left many farmers and would-be customers out in the cold.

Kimberly Null and her husband Nick de Sieyes founded the company with friend Ethan Rublee.

Produce and other local items like chicken, eggs, coffee and jams are ordered online for curbside pickup or delivery.

“When we saw what was happening with the lockdown, we all three just said to each other, ‘Let’s do this now!’ We decided to create pickup boxes that people could come get at our farm,” says de Sieyes.

EatLocal.Farm is basically an online farmers’ market portal with a unique dashboard from which consumers can select a variety of produce and protein items from an ever-increasing pool of suppliers. They can pick up their treasures at a farm stand on Valencia Road in Aptos or have the boxes delivered locally.

All three founders are highly educated refugees from the worlds of academia and high tech. Null has a PhD in marine science and came from Indiana to do postdoc work at UC Santa Cruz, where she met de Sieyes. Until recently, she worked at the Moss Landing Marine Lab.

De Sieyes comes from Maine and calls himself a “recovering academic.” He came west to study at Stanford and UC Davis, pursuing a PhD in environmental engineering. Five years ago, he left academia to work with his brother in real estate investments, which is how farmland became a topic of interest. The couple now lives in Aptos, where they have a farm and vineyard near the Wild Poppies olive orchard, growing everything from lima beans to corn, with the help of their two young children.

Rublee describes himself as a serial entrepreneur and expat from Silicon Valley, where he worked in robotics at Google. He later started and sold a company that provided a computer vision and machine-learning platform for Hollywood creatives.

“After the last company, I knew I wanted to get involved in applying technology to the local food system. Something that made an environmental and social impact sounded like a great second act!” says Rublee, who now lives on a farm in Watsonville with his wife and their twin sons.

Their method in building the online store was to choose favorite vendors, going down the list from local farmers’ markets and picking the ones they felt were the best.

“It started with P&K strawberries, they are the best! And then Blue Heron and Borba Family Farms,” says Null. They quickly added chickens from Fogline Farm, eggs from Pajaro Pastures, salsas and

are so excited that Jordan’s book launched! Join her as she shares her unconventional secrets in these approachable, fun, flavorful and low sugar preserving techniques. YUM.

“I knew I wanted to get involved in applying technology to the local food system. Something that made an environmental and social impact sounded like a great second act!”

Invention doesn’t always rely on advanced technology; sometimes, a little creativity will do. Call it thinking inside the box. The pandemic prompted restaurants to begin offering grocery boxes in addition to prepared takeout food. La Balena, for instance, offers one that includes genuine Italian staples like canned tuna, pasta, olive oil and semolina flour. Mentone provides regular Sunday boxes of fresh veggies from Spade & Plow farm, a tin of Wild Poppies olive oil, a Manresa Bread baguette and a bottle of wine. Quail & Olive in Carmel Valley also has weekly meal boxes, including olive oils and all the ingredients, for pickup or delivery.

Tomatero Organic Farm, out of Watsonville, has turned to pop-ups to supplement its farmers’ market presence. They pop up at Manresa Café in Campbell on Thursdays, and at other San Francisco Bay Area locations.

Calling himself “just bloody lucky!” with his timing, Tony Baker of Baker’s Bacon, left his longtime gig as executive chef at Montrio Bistro in Monterey earlier this year to build up his bacon business. As shelter in place began, he rolled out a series of special meat boxes (steaks, bacon, chicken, burgers, shrimp), which include Chef’s Palette spices by chef Dyon Foster, available for pickup on Tuesdays and Fridays in Marina. Baker has partnered with many local vendors, like Rogue Pyes and Bigoli Fresh Pasta. Local berries, vegetables, breads from Rise

+ Roam and butter and cheeses from Spring Hill Cheese can be added to any box.

Belly Goat Burgers began selling buildyour-own burger kits, featuring Markegard beef patties and Paulino’s buns, along with an array of housemade condiments and cheese options, at local farmers’ markets in late May. Chef Anthony Kresge says the response has been huge.

Colleen Logan from Carmel’s Savor the Local had been supplying local chefs with produce, but quickly retooled to sell produce from local farms directly to consumers. Mystery veggie boxes from Mariquita Farm are $50, and you can add items like Schoch cheeses, eggs, fresh pasta, elderberry syrup, Palo Colorado honey, breads and baked goods from Ad Astra and Rise + Roam and jams from Friend in Cheeses Jam Co.

Partnerships are burgeoning. Emily Thomas of Santa Cruz Mountain Brewing, which just celebrated its 15th anniversary, is doing a weekly collaboration box with various local food artisans, including El Salchichero and Hanloh Thai, where her son works. “Each box includes a special beer or wine and ingredients for dinner for four. We sell out every week. The Hanloh Pad Thai kit, (pictured above), which included a video of owner, Lalita Kaewsawang, showing how to assemble the meal, was a big hit!” Thomas says she chooses the beer and wine carefully to pair with the food. “It’s a lot of work, but it’s fun!

Customers are encouraged to leave a tip, which goes directly to field workers.

Once the go-to for Americans wanting farm fresh produce, CSAs (community supported agriculture) have been on the wane since the 2008 recession. Services like Good Eggs, Instacart and Sun Basket, along with meal delivery services like Blue Apron, Freshly and Hello Fresh, offered consumers the convenience of multiply sourced ingredients in a single delivery. But then came the COVID-19 pandemic and those services became overwhelmed, with consumers turning once again to CSAs. By mid-April, most local ones were completely oversubscribed. Some, like the Homeless Garden Project and Live Earth Farm, started waitlists. Others are just trying to cope with the newfound demand.

J.P. Perez of J&P Organics in Watsonville, a family farm and CSA that has been in business for 14 years, admits the sudden demand caught him completely off guard. “Oh, my goodness! In April, our online system said we had 750 new signups. I thought this must be a mistake! But no, our sales have been through the roof! I had to add two more delivery days and hire four new employees.” He’s also tripled his planted acreage and has turned to other farms to source more product, adding local honey, coffee from Carmel Valley Coffee Roasting Company, fresh flowers and eggs as add-ons to their core produce boxes.

See our complete listing of local CSAs at ediblemontereybay.com.

pastas from Two Dog Farm, coffee from 11th Hour, mushrooms from Far West Fungi and New Natives, and Wild Poppies’ awardwinning olive oil, naturally.

Borba Family Farms packs about 50% of each box for EatLocal.Farm, delivering the boxes to Aptos. Other vendors drop their wares to Null and de Sieyes, who pack up the rest of each order. As of press time, they were offering pickup in Aptos, on Wednesday and Thursdays, with local delivery from Watsonville to Scotts Valley and from Marina to Carmel for $10.

Rublee, who developed the website and came up with the clever name, says, “We’ve had 875 customers for 1,175 orders [as of May 19]. Nick thought we’d do $10k/month, but in just eight weeks, we’ve done $73k! It’s a bit chaotic right now, so we’re looking at modifying our processes.” The trio takes a small service fee of $7.50 on each order and the farmers get 100% of their asking price.

Customers are encouraged to add a tip for field workers. “We call them our veggie warriors!” says Null.

Rublee says his goal is to figure out a way to facilitate the online ordering process to make it as smooth as possible for everyone, helping farmers predict what they need to plant. “How can we move food from field to table with very little waste?” He also wants to expand the storefront to include locally produced cheeses and ice cream.

“We’re so happy to be helping farms,” adds de Sieyes. “We’re in an amazing place; it feels like we’re at a golden point. It’s very cool!”

Laura Ness is a longtime wine journalist and judge who contributes regularly to Edible Monterey Bay, Spirited, Los Gatos Magazine and The San Jose Mercury News. She enjoys showcasing the intriguing characters who inhabit the world of wine and food.

In the springtime when the world is green. In the summer when the air is warm and fragrant. In the fall when the light slants sideways. Even in the winter, in a break between storms. There is no wrong time for a picnic. In fact, these times are perfect for a picnic—in wide open spaces, friends can sit six feet apart and partake in beauty, good food and companionship, while safely reducing the risk of germ transmission. Get outside, and take some snacks!

Children understand this intuitively: Breakfast is much more fun if you eat it spread on a beach towel in the yard. At its simple heart, a picnic is nothing more than this, delight in two of life’s great pleasures, good food and fresh air. Appreciation of one strengthens appreciation of the other, in a delicious feedback loop. What a beautiful meadow/ what an excellent sandwich/listen to that birdsong/have a sip of this! And so on.

So we packed our baskets. Actually, we packed four of them. Each

with a theme, because we could not choose a favorite, and when writing for a food magazine, it seemed poor form to advise people to bring both quiche and spring rolls, cold sesame noodle salad and ginger beer and marinated cheese. Not that there’s anything wrong with an ad hoc assembly. In fact, one of the beautiful things about a picnic is the freedom of it; go where you like, and eat what you like, and stay as long as you like and eat it in whatever order you like. Indulge in the occasion; dress fancy if that makes you happy, or go as you are. Discover a local park, climb a peak, spread a blanket beneath a tree in your backyard. There are no rules on a picnic. Just a set of guidelines, perhaps. A framework around which to assemble an epic outdoor feast.

Amber Turpin and Jessica Tunis live with their respective families in the green folds of the Santa Cruz Mountains. They share a love of food and writing, adventure and good company.

Pumpernickel Open-Faced Sandwiches

Smoked Almonds

Sauerkraut

Apples with Aged Cheddar Cheese

Hard Salami with Whole Grain Mustard Beer in Amber Bottles

Assemble this one in the field or wherever your picnic takes you. A small cutting board is ideal for slicing whole cukes, or slice them ahead of time and carry them in a reusable container.

1 loaf pumpernickel bread, sliced

8 ounces cream cheese

4 ounces smoked fish

1 small cucumber, sliced

1 small bunch fresh dill or arugula

Spread each slice of pumpernickel with approximately 1 ounce of cream cheese. Top each with a few thin slices of cucumber. Evenly distribute chunks of smoked fish among all the sandwiches and top with sprigs of dill. Serves 4–8.

Topping Variations:

Blend chopped, toasted walnuts + honey + dried rose petals into cream cheese and top with berries for a sweeter slant. Top bread instead with avocado + thin slices of lemon + flake salt.

Cold Sesame Noodle Salad

Spring Rolls with Peanut Sauce

Miso Pickled Eggs

Quick Asian Pickles

Matcha Shortbread

Ginger Beer or Green Tea Cocktail

1 cup rice wine vinegar

1 cup cold water

1 tablespoon light honey

1 tablespoon sea salt

2 inches ginger, thinly sliced

3 cloves garlic, smashed

1 teaspoon whole coriander seeds

6 whole black peppercorns, lightly crushed

½ teaspoon red chile flakes

One pound vegetables of choice; think thinly sliced cucumbers, radishes and red onion, peeled carrots, and fennel cut on a long diagonal.

Make the brine. Combine rice vinegar, water, honey, salt and ginger in a saucepan and bring to a boil, stirring to dissolve salt and honey. For a milder blend, omit the ginger from the boiling step. Remove from heat and allow to cool while you prep the vegetables.

Wash and peel carrots, peel cucumbers if desired (peeling helps the flavor penetrate the veggies.) Thinly slice the red onion, cucumbers, fennel, radishes and any other vegetable that catches your fancy.

Layer the remaining spices in the bottom of a quart or 1 liter jar. Tightly pack the vegetables in the jar on top of the spices, then pour the brine mixture over them, making sure that all the vegetables are covered by the brine. (If you have some brine left over, it makes a great base for a salad dressing.)

Let the jars cool to room temperature, then seal the lid and place in the refrigerator and allow the flavors to meld for a day or two if possible before eating. These can be eaten in as little as an hour after making them, but they are at their flavorful best if allowed to marinate for 48 hours. Store in the refrigerator for up to 2 months. Note: recipes for Spring Rolls with Miso Sauce and Miso Pickled Eggs can be found on our website.

Hand Pies

Potato Salad with Green Beans and Cherry Tomatoes

Brownies

Strawberry Lemonade (with or without vodka)

Crust

1 cup all-purpose flour

1/3 cup whole wheat flour

2 tablespoons brown sugar

½ teaspoon salt

8 ounces (1 stick) cold butter, cut into small cubes

4 tablespoons ice water

Place the dry ingredients in the bowl of a food processor and blend. Add the cold butter chunks and process in bursts until incorporated and the dough is sandy looking. Transfer to a mixing bowl and add the ice water. Stir with a fork until the dough forms clumps, then gather together with your hands and knead briefly and gently, just until

you can form a ball. If the dough is too dry, add tiny bits of water to bring together. Form a square-shaped disk and wrap in plastic wrap. Refrigerate overnight.

Preheat the oven to 375° F. Roll the disk of dough out on a floured surface to form a large rectangle, about 6 x 12 inches. Using a pizza cutter, cut the rectangle in thirds lengthwise, then in half horizontally, forming 6 squares. Place 2 tablespoons of your filling of choice in the upper half of each square, then fold the lower portion of dough up over filling. Crimp edges with a fork or fold over on itself to seal the hand pie. Cut a few vents in each pie with a knife or fork tines, then transfer them to a parchment-lined baking sheet. Place sheet in refrigerator to firm up for 20–30 minutes, then bake for 30 minutes, rotating the baking sheet halfway through to ensure even baking. Makes 6.

1½ cups roasted or sauteed vegetables mixed with 2–4 tablespoons of cheese (chèvre, brie, grated Cheddar)

1½ cups ricotta cheese mixed with 2 tablespoons pesto

1½ cups chopped fresh fruit mixed with 2 tablespoons sugar

1 cup jam or preserves

Marinated Goat Cheese

White Bean Dip with Herbs and Lemon Zest Nicoise Chopped Salad with Little Gems

Baguette

Lemon Verbena Cucumber Cooler (with gin)

1 15½ ounce can white beans (such as cannellini), drained and rinsed, or 1½ cups cooked white beans

3 small cloves garlic, peeled

2 teaspoons lemon juice

Zest from 1 lemon

¼ cup plus 1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil, divided

2 teaspoons fresh herbs (rosemary, thyme, parsley, dill or combination)

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Combine beans, garlic, lemon juice, zest and ¼ cup olive oil in food processor. Blend until smooth. Add the herbs and blend again, then season with salt and pepper, to taste. Transfer dip to a serving bowl or jar and drizzle with the remaining tablespoon of olive oil.

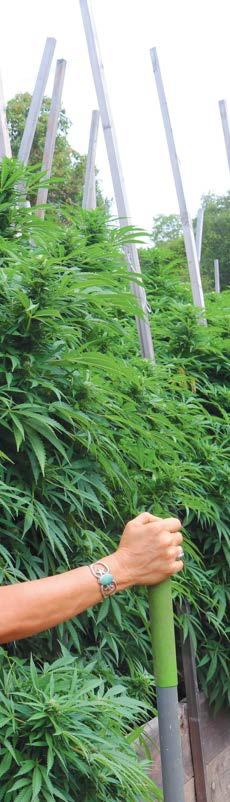

a trip around the world with a man growing ancient landrace strains in his botanical garden in the Santa Cruz Mountains

BY MARIA GRUSAUSKASJeff Nordahl hadn’t touched cannabis for at least a decade when his doctor suggested that it might be beneficial to his health. So he revisited the plant that had fueled the adventures of his teens and 20s—but it was not the energized, inspired experience he remembered. The new modern weed didn’t make him want to jump on his bike, clatter around in the kitchen making up a new recipe or dance for hours to the Grateful Dead; it made him want to take a nap.

“I thought maybe I was just nostalgic or getting old, but it turns out that cannabis was actually really different back then,” says Nordahl, now 47.

His curiosity was piqued, and he began learning all he could about older strains of cannabis, the ones the world smoked back before “couch lock” was even in the cannabis-consuming zeitgeist. His passion blossomed into something of an obsession, as be began collecting landrace cannabis seeds in a tackle box now brimming with more than 100 varieties from around the world.

Nordahl is currently in his third year

of testing them on the sun-drenched slopes of his botanical garden in Boulder Creek—which will one day be opened to the public for events and retreats. He also plans to continue donating exotic strains to those in the community who need it most.

Nordahl founded Jade Nectar medical cannabis collective in 2016 (full disclosure, I’ve been using its CBD oil tinctures for headaches and cramps since around that time). But by advocating sun-grown landrace genetics and incorporating them into his product line, he’s swimming against the current trends of an industry where a lot of what is being grown has never seen the sun.

And while he has learned a lot—and is clearly having a really good time doing so—Nordahl has barely scratched the surface: so far he’s popped only about 5% of his seed bank (which, like a baseball card collection, continues to grow).

“Every single one of these seeds is a mystery,” he says. “We don’t know what they will turn into. And that just makes it really fun.”

Landrace strains are the oldest, purest cultivars, and the foundational building blocks for all modern strains. Just a little further down the same garden path as the heirloom concept, which may be more familiar to California’s culinary community, landrace seeds have similarly been passed down through history, but they are also specific to a region, whether that’s a village, a province or a country.

“The landrace tend to be more uplifting, energizing, amplifying, thought-provoking, creative, silly,” Nordahl says, showing me some speckled Acapulco Gold seeds, one of the first strains he bred for his own seed bank, and the one that remains his favorite for going out dancing. In the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, most of the weed in the U.S. was landrace sativa from Colombia and Mexico.

Michael Pollan writes about domestic crops in The Botany of Desire, “...the offspring of the ancient marriage of plants and people are far stranger and more marvelous than we realize. There is a natural history of the human imagination, of beauty, religion, and possibly philosophy too.”

This may all seem a little out there (and I assure you, that is the point), but landrace seeds, according to Nordahl, carry much more than just the influences of the climate and seasons in which they’re grown.