8 minute read

Chapter I: Triads 7

Chapter I

Triads

Advertisement

Triads do not represent a separate magic, only a more potent version of the only magic in town. W.A. Mathieu4

Voice Ranges

Traditionally, harmony is written for four voices (soprano, alto, tenor and bass), whose usual ranges are given below. This textbook however, is intended for guitar players; therefore, while I have retained the four-voice setting, the voice ranges will fluctuate to accommodate the specific tuning and range of the instrument.

Example 1.1

Intervals

Essentially, the understanding of intervals is based on the overtone series. The closer an interval is to the fundamental, the more stable and consonant it appears; the further it is, the less stable and more dissonant it appears. Therefore, a “kinship system” of intervals is organized according to the closeness or distance of overtones to the fundamental. The perfect consonances, which are the closest to the fundamental, are: the prime, the fifth and the octave, the imperfect: the third and the sixth. Dissonances, which are the farthest from the fundamental, are: the major and the minor second, the perfect fourth,5 the major and the minor seventh and all the augmented and diminished intervals.

Example 1.2

4 Mathieu, W.A. 1997, Harmonic Experience, Inner Traditions International, Rochester, p.360.

5 The perfect fourth is considered dissonant when there is no other interval below it; consonant, when there is a third or a fifth below it.

5 5

Further on, the intervals of a scale can be classified into: perfect (unison, fourth, fifth, and the octave), and major or minor-second, third, sixth and seventh (see the above example). A major or perfect interval raised for a half step is an augmented interval; a minor or perfect interval lowered for a half step is called diminished.

Modes

Modal scales historically precede diatonic scales, and although they form the essential vocabulary of much folk music as well as Renaissance contrapuntal thinking (in the guise of ecclesiastic or church modes), their use in traditional harmony is usually exceptional and rather limited6 .

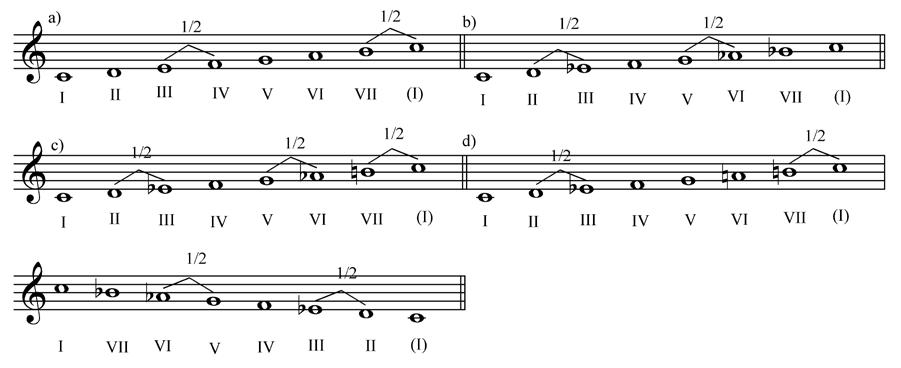

It is important to mention that all of the idiosyncrasies of modes have been reduced in traditional harmony to only major (Ionian) and minor (Aeolian) modes. The following example shows the ecclesiastic modes given from keynote C.

Example 1.3

Diatonic Scales

The scales that are the cornerstone of traditional harmonic values are called diatonic and include major (example 1.4a) and three types of minor scales: natural (b), harmonic (c), and melodic (d). As can be seen, the configuration of whole-tones and halftones varies from one scale to the other. The melodic minor, whose ascending and descending variants differ, is a special case among the diatonic scales, but not among modal systems (Indian ragas, for example).

6 Despite discouraging influence of some writers on this subject, notably H. Schenker and A. Schönberg, modal thinking has not only survived in the guise of ecclesiastic modes, but is widespread in various syntheses and levels of complexity from contemporary classical music to jazz.

6 6

Example 1.4

Scale Degrees

Tonic (I), Subdominant (IV), and Dominant (V) are called tonal degrees of a scale; they are the principal harmonic actors outlining a key or tonality. 7 Modal degrees (III and VI), on the other hand, do not affect tonality, but bring a sense of mode, since they differ in major and minor. Because of its prominence in the VII-I movement, the leading tone is also one of the critical degrees and that requires special handling in harmonic resolution.8

Triad Types

The simplest type of chord called the triad is built by superposition of two thirds. The four types of triads used as building blocks of the traditional harmony are: a) major, b) minor, c) augmented and d) diminished (example 1.5).

Example 1.5

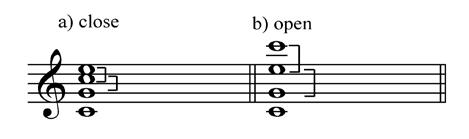

Spacing

The spacing of the voices, as shown bellow in example 1.6, can be in: a) close position and b) open position. In close position, no tone of the same triad can be inserted between soprano, alto and tenor, while in open position, it can.

7 According to Piston: “The supertonic should (therefore) be included in the list of tonal degrees, since it partakes of both dominant and subdominant characteristics, but should be distinguished from I, IV, and V as having much less tonal strength. (W. Piston, 1987, p.55) 8 According to another classification, this by Susan Andre-Marchal, degrees divide into three categories: 1. Tonal degrees (I, IV, V), 2. Second order degrees (II, VI), 3. Third order degrees (III, VII). (S. AndreMarchal 1974, p. 1)

7 7

Example 1.6

Doubling

The doubling of the triad notes as shown, can include: a) double root, b) triple root and third, c) double fifth, and d) double third. While the preferred doubling is of the root, doubling of the third and the fifth is done according to the harmonic function of the note or the logic of voice leading. The doubling of the leading tone in Dominant function is avoided, except in sequences.

Example 1.7

Triads in Scales

Triads can be built on all scale degrees. The example 1.8 shows all the triads in major and minor scales. In major: I, IV and V are major triads, II, III and VI are minor and VII is diminished. In harmonic minor, I and IV are minor triads, V and VI major, II and VII diminished and III augmented; in melodic minor: I and II are minor, IV and V major, VI and VII diminished and III augmented (the descending form of melodic minor is the same as in the natural). The natural minor scale is built on the sixth degree of the major and contains all the triads so far mentioned, except that they are assigned to different degrees: I, IV and V are minor, III, VI and VII are major and the II is diminished.

Example 1.8a

Example 1.8b

8 8

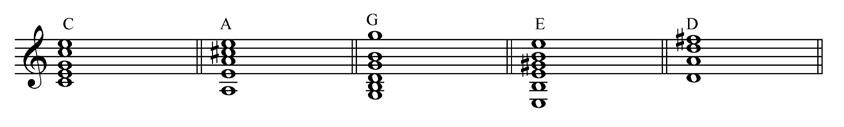

Triads in Root Positions

The following examples show some common chords built on triads in root positions used on the instrument. While example 1.9 shows the five chord patterns in an easy mnemonic order (CAGED), example 1.10 shows all the triad types in close and open positions.

Example 1.9

Example 1.10

Rules of Motion

There are three possible movements of voices: a) direct, b) contrary, and c) oblique (example 1.11). Direct motion is the movement of voices in the same direction; contrary motion is the movement of voices in opposite directions; in oblique motion, one voice moves while the other remains static.

Example 1.11

9 9

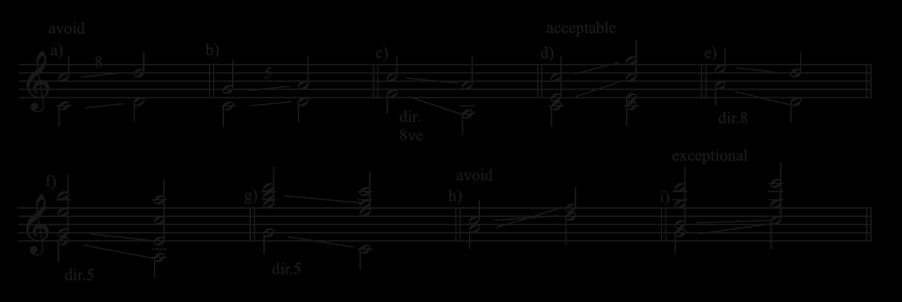

In traditional harmony, one should avoid: parallel octaves, fifths and unisons.

9

Direct (hidden) fifths and octaves, which are brought by direct motion from smaller intervals (example 1.12a-c), are also avoided, unless they occur in the same harmony (d), between interior voices, or between an interior and one of the outer voices (f, g), and if the upper voice proceeds with a gradual movement (e). Crossing of voices should also be avoided (h).

Example 1.12

Progressions

Example 1.13 shows all the basic harmonic progressions, including bass movement of a fourth, fifth, third and a second. In general, if two triads have one or more notes in common, one should repeat the common notes, while moving the remaining notes to their nearest positions (a-c). In the case of no common notes between the triads, one should move the upper three voices to their nearest position opposite to the bass (d). Note that, since the traditional resolution of the leading tone is into the octave, the progression of V-VI results in VI with a doubled third (the example f should be avoided because of the wrong resolution of the leading tone).

Example 1.13

The following two examples are both transcribed from piano literature: the first, an excerpt from I. Albeniz’s Cordoba, shows use of triads in root positions with traditional voice leading; the second, an excerpt from Debussy’s Prelude Canope, illustrates an Impressionist use of triadic harmonies in a modal context. Note that Albeniz, in his progression, uses both natural and harmonic minor.

9 J. S. Bach calls parallel octaves and fifths “the greatest mistakes in music”, The Bach Reader, 1972, p. 392.

10 10

Appendix I

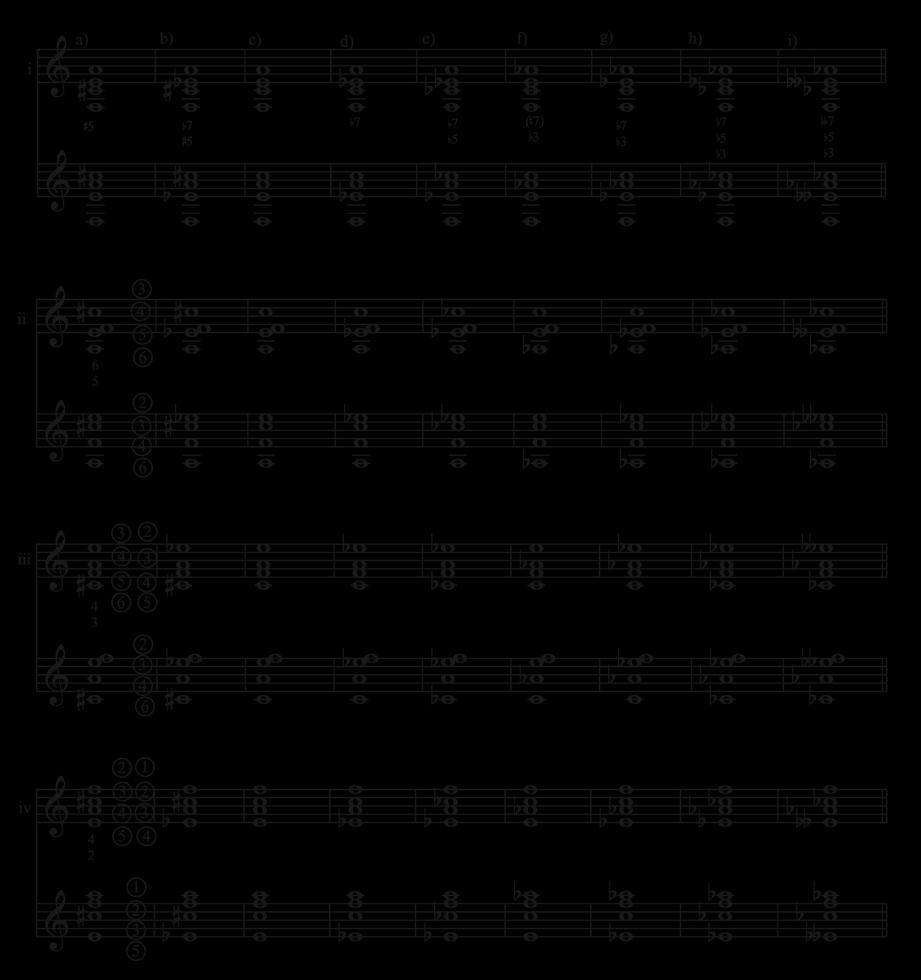

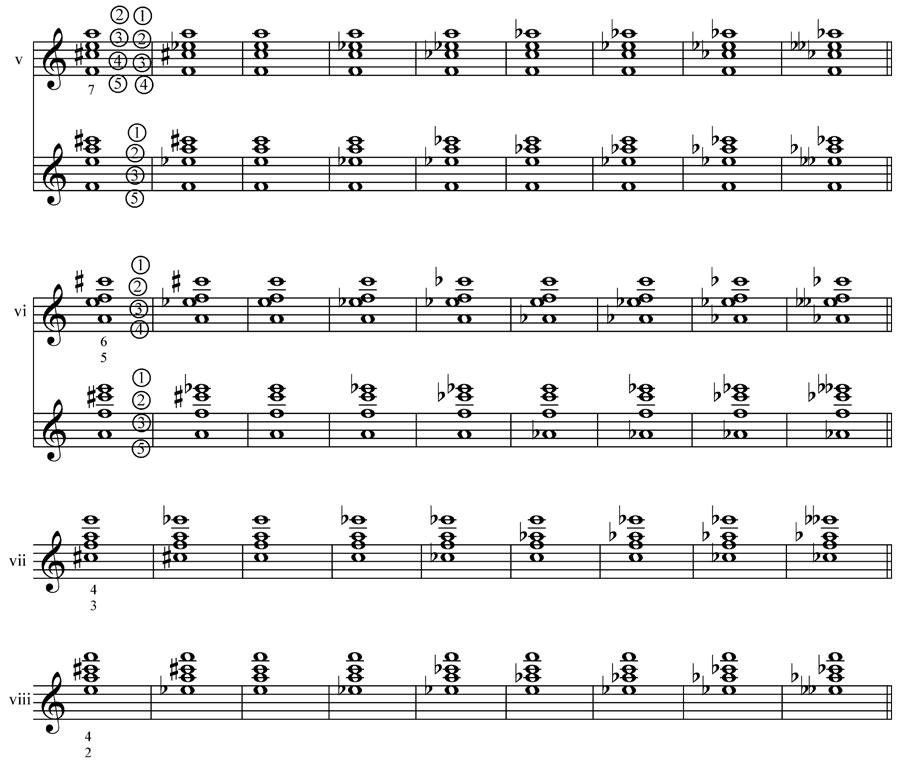

Seventh Chord Inversions

Since seventh chord inversions are crucial for figured bass on the guitar, I have included an additional appendix consisting of all the nine seventh chord types shown in different positions on the fingerboard. Examples a-f show chords in two different voicings: the note in tenor of the upper staff is moved to soprano of the lower. In consequence, all the chords in the upper staff are played on contiguous strings, while all the chords of the lower staff are not.

123 123

124 124