2024

GATHERING REPORT & RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF THE NEXT 10 YEARS OF LABS

2024

GATHERING REPORT & RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF THE NEXT 10 YEARS OF LABS

Convened and sponsored by Action Lab and Social Innovation Canada

Sponsored and supported by Suncor Energy Foundation.

Ben Weinlick, Anthony Bourque, Paige Reeves, and Rebecca Rubuliak of Action Lab, Diane Roussin of Winnipeg Boldness Project, Geraldine Cahill of Social Innovation Canada

Action Lab is a social enterprise of Skills Society, a not-for-profit disability rights and service organisation in Edmonton that has always been committed to innovation in supporting marginalised community members to find belonging and lead rich, inclusive lives.

Action Lab is part of a social innovation ecosystem in Canada that is engaging in fresh ways of tackling some of the most complex challenges we’re all facing in society today. The Action Lab space was designed for hosting diverse collectives who need to tap into the deep knowledge in their community, look at issues from unique perspectives and generate strategic possibilities. The Action Lab experience promotes creativity, offers tools to help tap into collective wisdom and helps people and systems to prototype proposed solutions.

and UpSocial, Mark Cabaj of Here2There Consulting, Patrick Dubé of Transition Bridges Project and Rhizome group.

Social Innovation Canada (SI Canada) is working to address complex challenges of national relevance and create transformational change.

We support social innovators and ecosystem builders, connecting them to resources, opportunities, and each other. We lead national interventions with place and identity-based communities to address complex issues. We work to reduce systemic barriers and unlock resources to enable the implementation and scaling of solutions.

Future of Labs (FOL) brought together an impressive group of trailblazers and experienced innovators who steward and design collective problem solving processes and share a common goal of creating more impactful practices. The gathering was a catalyst for shaping the next ten years of Lab approaches - looking deeply at what’s been working, not working, and collectively visioning next practices for the field. The resulting work supports more people and systems to get better at understanding, connecting and working with some of the most wicked challenges our world is facing today.

There are several unique ways knowledge was gathered and mobilized before, during, and after FOL. Diverse Lab practitioners from across Canada and beyond were invited to participate in pre-gathering interviews, focus groups, and surveys that contributed to the Primer, the design of workshops, and the production of pregathering learning reports from the field. Thoughtfully designed workshops supported rich dialogue. Post gathering, this report with pathways, signals, and principles Lab explorers and funders of Labs might consider when designing and enabling robust, equitable and impactful Lab processes as well as three podcasts have been produced. These knowledge artefacts will help local and national practitioners and innovators around the world strengthen their practices as well as help funders and enablers of Labs to better evaluate Lab proposals.

In the hopefully not too distant future, we hope there will be support for lab stewards to be able to come together at least yearly to share learning and get better at the practice of labs. We need systems change practices of all kinds in the turbulent world of today and the creative experimentation and reframing of complex problems that labs are so good at, are needed more than ever. If we don’t have labs into the future, there will be a whole lot of innovating and change around surface problems that might not really be getting at the core challenges of our times. We hope the field continues to evolve and is bold. Labs are needed. The strong relationships and creative collisions of lab leaders will ensure labs continue to be relevant and sensitive to the complexities of the future.

You can view the FOL reports, podcasts, and other knowledge products at our webpage here: www.actionlab.ca/future-of-labs-gathering

→ First, many thanks to the FOL delegates, many of whom travelled great distances and took time away from loved ones to generously share their time, wisdom, and experiences to help shape the next generation of Social Innovation Labs.

→ Thank you to core conveners and sponsors Social Innovation Canada, Action Lab, and Suncor Energy Foundation for resources to make the FOL possible.

→ Thank you to Community Foundations of Canada and University of Waterloo WISIR for contributing to bursaries to support equity in attendance.

→ Thank you to Edmonton Community Foundation, Hamilton Community Foundation, and Oakville Community Foundation, for making knowledge sharing more inclusive, grounded in oral traditions and accessible through sponsoring a 3 part podcast series related to the FOL.

→ Thank you to the contributors to this Report who helped synthesise and write:

Ben Weinlick

Alex Ryan Paige Reeves Keren Perla Marlieke Kieboom

Rebecca Rubuliak Mark Cabaj

→ Thank you to Aleeya Velji, Alex Ryan, Ben Weinlick, Darcy Riddell, Diane Roussin, Geraldine Cahill, Keren Perla, Mark Cabaj, Marlieke Kieboom, Patrick Dube, and Tim Draimin for sharing their expertise to facilitate the 5 research conversations at the FOL gathering on Cortes Island.

Aleeya Velji

Alex Ryan

Alison Cretney

Amanda Hachey

Andre Fortin

Andrea Nemtin

Annand Ollivere

Annelies Tjebbes

Anthony Bourque

Ben Weinlick

Bonnie Veness

Brent Wellsch

Carla Stephenson

Carolyn Townsend

Cassandra Litke

Wyatt

Cheryl Rose

Chris Chang-Yen

Phillips

Darcy Riddell

Diane Roussin

Geraldine Cahill

Gordon Chan

Heather Remacle

Huzaifa Faisal

Ione Ardaiz

Jill Andres

Jimmy PaquetCormier

Julia Dalman

Katie Davey

Keren Perla

Kerri Klein

Kirsten Wright

Lewis Muirhead

Lindsay Cole

Lisa Gibson

Mark Cabaj

Marlieke Kieboom

Maryam Mohiuddin

Ahmed

Meghan Durieux

Melanie Thomas

Miquel de Paladella

Monica Pohlman

Nicholas Scott

Paige Reeves

Patrick Dube

Paz (Pachy) OrellanaFitzgerald

Penelope Jean Stiles

Pieter de Vos

Rebecca McSheffery

Rebecca Rubuliak

Rhea Kachroo

Roya Damabi

Sam Rye

Sarah Brooks

Sarah Lamb

Sean Geobey

Sonja Miokovic

Sophia Ikura

Stacy Barter

Tim Draimin

Tonya Surman

Tracey Robertson

Virginie Zingraff

The seeds for FOL came from a community-based nonprofit Lab in western Canada called Action Lab. For the last 15 years Action Lab has led community think tanks and Labs around complex social challenges related to the inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities, behaviour change science in anti-racism interventions, and humanizing social service case management systems.

Like how most system change efforts begin, the idea for FOL began when leaders at Action Lab noticed a signal emerging in the Lab space. Questions were bubbling up as to whether Lab practices were a thing of the past or an approach worth evolving. The Action Lab leaders started to talk amongst themselves and then reached out to see if other colleagues were seeing the same signal. Overwhelmingly, experienced colleagues in public, private, and community Lab spaces were noticing the same signals, and that sparked a desire to come together to explore and make some offerings to the field. A diverse and experienced Canadian convener team then came together to steward FOL.

We recognize the FOL is one type of Lab practitioner gathering and that there are other important gatherings and research explorations happening elsewhere that focus on nuanced aspects of Lab and systems change practice. Our unique offering was to gather a diverse cross-section of experienced Lab leaders and tap into honest and generative wisdom around what could be better. We hope this complements the work of emerging leaders and supports greater coherence on the roots of Lab ideas, philosophies, and practices.

All sectors are under immense stress - more leaders are recognizing the significant challenges society is facing due to transition, polarisation, and the current trend of a snapback to solutionism in tackling complex challenges. This approach of oversimplified solutionism leads to short-sighted, quick fixes that overshadow the need for real systemic change.

Over the past 15 to 20 years, Social Innovation Labs, Innovation Labs, Impact Labs, Social Labs, and Living Labs were launched by many trailblazing changemakers in the Canadian landscape. These included

federal and provincial-led Labs, as well as many community-based social Labs. In discussions with Lab practitioners across Canada, we are finding that many mature Labs and Lab practitioners are finding themselves in a period of reflection. While Lab approaches have shown promise in some ways for helping collectives to tackle tough challenges, there are gaps and inconsistencies in methods, practices, and impact.

Lastly, we also noticed a signal that funders, enablers, and supporters of Labs and Lab-like processes need better sense-making tools and evaluation of criteria to assess Lab proposals and their potential impact.

Lastly, we also noticed a signal that funders, enablers, and supporters of Labs and Lab-like processes need better sense-making tools and evaluation criteria to assess Lab proposals and their potential impact. In light of these signals, the conveners of the FOL identified five key conversations we felt were important for the Lab field to have and (try to) converge on to help inform and build a next generation of more effective Labs practice. These serve as an entry point to learn from Lab practitioners through FOL - the purpose not being to reach consensus, but rather to establish coherence. The Broader Arc of Future of Labs

→ An itch for a new iteration

→ A Primer to frame key conversations

→ The gathering itself

→ A Report to harvest our insights

→ A new canvas for the field of Labs

ANTHONY BOURQUE, ACTION LAB

Anthony is the Director of Research and Social Innovation of Action Lab, a social innovation consultancy and social enterprise of Skills Society Anthony has a diverse background in construction, fitness, playwork, social innovation and humancentred design. After working abroad in South-East Asia, Anthony completed graduate research focused on understanding perceptions of risk in unstructured play to understand better the obstacles families face in their communities. He brings his qualitative research and facilitation experience together with playful methods like Lego Serious Play. Anthony consults, designs, facilitates, and leads workshops & innovation Labs around complex challenges.

BEN WEINLICK, ACTION LAB

Ben is the Executive Director of Skills Society and was instrumental in developing their social enterprise systems change consultancy called Action Lab. Skills Society is one of the largest and longest serving disability rights and service organisations in Edmonton, Alberta within Treaty 6 territory. Skills Society has a long history of creating innovative social service culture that support marginalised communities to thrive. Ben has been deeply involved in systems change work through stewarding think tanks and social innovation for the last 15 years. He is also the founder of a creativity and innovation consultancy network called Think Jar Collective, and co-founder of a tangible social innovation called MyCompass Planning that is scaling across North America. Ben is passionate about helping people, organisations and systems to get better at navigating complex challenges together.

Diane Roussin is a dedicated community leader and a proud member of the Skownan First Nation. Diane is the project director of The Winnipeg Boldness Project, an initiative that seeks to create large-scale, systemic change for children and families in Winnipeg’s Point Douglas neighborhood. The project uses tools and processes from social innovation to develop community-driven solutions to create better outcomes for the neighborhood’s residents.

Geraldine Cahill joined Social Innovation Canada (SI Canada) in early 2023 as Director of Engagement. At SI Canada she leads Social Innovation Labs involving multi-stakeholder facilitation, stewardship and project design in areas of complex need. She is also guiding the strategic communication and engagement direction for SI Canada, building on her past experience with Social Innovation Generation (SiG). She is the founding director of UpSocial Canada, inspired and informed by UpSocial Global in Barcelona. Geraldine has also designed a social innovation curriculum for undergraduate university students and nonprofit professionals. In 2017, she co-authored Social Innovation Generation: Fostering a Canadian Ecosystem for Systems Change, with SiG colleague, Kelsey Spitz.

Mark is President of the consulting company From Here to There and an Associate of Tamarack - An Institute for Community Engagement. Mark has firsthand knowledge of using evaluation as a policy maker, philanthropist, and activist, and has played a big role in promoting the merging practice of developmental evaluation in Canada. Back in Canada, Mark was the Coordinator of the Waterloo Region's Opportunities 2000 project (1997-2000), an initiative that won provincial, national and international awards for its multi-sector approach to poverty reduction. He served briefly as the Executive Director of the Canadian Community Economic Development Network (CCEDNet) in 2001. From 2002 to 2011, he was Vice President of the Tamarack Institute and the Executive Director of Vibrant Communities Canada.

Paige is the Director of Research and Social Innovation of Action Lab, a social innovation consultancy and social enterprise of Skills Society. Paige consults, designs, facilitates and leads workshops & innovation Labs around complex challenges. She brings deep knowledge of participatory research methodologies, and has diverse experiences with facilitating human-centred design approaches. Paige has a unique perspective in being in both the academy and grounded in community based research for systems change. Her graduate research centers around ways of fostering communities of belonging. Paige has also been mentored in developmental evaluation and

applies this in longer term Labs she stewards to help collectives ensure learning and outcomes are helpful and relevant. Paige is passionate about making real systems change happen for people and communities that need it.

Patrick is a passionate advocate for social and environmental innovation, a father of two, a musical explorer, a learning horseback archer, and a lifelong entrepreneur with a rich background in research and technology. Holding a master's degree in anthropology and having pursued Ph.D. studies in complexity science at the University of Montreal/CNRS Strasbourg, he co-founded an A.I. startup (1999-2004) aimed at reducing hospital misdiagnoses. His career has since spanned various roles, leveraging open innovation to support a diverse array of initiatives from 2006 to 2012. Between 2010 and 2016, Patrick served as codirector of research and innovation at the Society for Arts and Technology [SAT], later co-founding a service design studio that has been instrumental in fostering innovation practices within institutions, organizations, and communities. As the executive director of the Social Innovation House in Montreal until 2023, he co-designed and supported various open and Social Innovation Labs, focusing on social justice, community resilience, regenerative practices, and systemic change through regulatory and financial innovation. Since 2023, Patrick has contributed as a costeward of the Transition Bridges project and joined the Rhizome Creative Capital group, furthering his commitment to social and environmental innovation. He also serves on the board of the Quebec Network for Social Innovation, demonstrating his unwavering dedication to advancing the practice.

Rebecca is the Director of Continuous Improvement and Innovation at Skills Society, a large disability rights and services organization, where she co-stewards innovative projects, organizational development, and learning practices to affect change towards supporting equity and inclusion in community. Part of her role is co-stewarding workshops and social innovation processes out of Action Lab, a social enterprise of Skills Society. Rebecca is motivated by a curiosity about how we cultivate communities where everyone is valued and belongs. Rebecca’s graduate research engaged

participatory methods to explore alongside children experiencing disability how we might better support inclusion and deeper belonging.

Aleeya was a co-steward of the Edmonton Shift Lab, and built a public sector innovation Lab within the Ministry of Education in Alberta. Currently, in her role at CMHC she has supported, as a lead designer, several Solutions Labs focusing on finance and housing. Aleeya is also currently supporting an Indigenous Innovation Lab in Post Secondary Institutions originally as the lead designer and now as an Advisor to the design firm Coeuraj. She continues to support Lab work through advisory roles in Montreal, and with design and facilitation roles for ongoing Lab work with various organizations across Canada.

ALEX RYAN, SYNTHETIKOS

Alex is the co-founder and CEO of Synthetikos Inc. where he is currently consulting as the lead architect and facilitator for the Future of Hockey Lab. As the Senior Vice President of MaRS Partner Solutions Group he led partner solutions, helping government and corporate partners accelerate the adoption of innovation in their organizations, markets and cities. At MaRS Alex oversaw 150 innovation projects, Labs, challenges and missions, including scaling MyStartr and the Engineering Change Lab from ideation through to national programs impacting thousands of lives. His writing on smart cities, data governance, policy innovation, social innovation, systemic design, and complex systems science has been published by the World Economic Forum, Fast Company, Axios, Stanford Social Innovation Review, and Complexity. Alex is also co-founder of Alberta CoLab, the first provincial government innovation Lab in Canada where he led over 100 Lab projects across every ministry of government. He is an executive-in-residence at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management.

Darcy has worked in cauldrons of social change for 25 years - on forest campaigns conserving the Great Bear Rainforest, leading strategic learning

at McConnell Foundation, training leaders,designing and facilitating multi-sector change initiatives, funding First Nations stewardship at Makeway, advancing environmental policy change, and founding collaborative networks centring sustainability, justice, and systems innovation. She works with RAD Network on Indigenous-led conservation finance and nature-based solutions, and as a consultant. Darcy has a Ph.D. in Social Innovation from UWaterloo focused on leadership and impact in complex multiscaled systems, and reads tarot cards in service of collective transformation. She sits on the board of Social Innovation Canada and Hollyhock. A fifth generation British Columbian, she lives with her two children in əsəlilwətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh), Xʷməθkwəyəm (Musqueam), & Sḵwx̱wú7meshsi (Squamish) territories, where she’s a grateful student of nature and wisdom traditions.

Keren is President of Perla Inc. and strategic advisor and innovation architect with the Energy Futures Lab leading netzero research initiatives and innovation challenges that bring together government, investors, industry, entrepreneurs, Right and Title Holder and communities to collaborate on energy transitions. Keren’s career spans over two decades focused on public sector innovation working in multiple policy domains, from energy development to circular economies to health innovation and everything in between. She is Co-founder of the Alberta CoLab –the first public sector Social Innovation Lab to launch at a provincial level - where she led and oversaw over 150 projects (in Alberta, Canada and with the UNDP) to successfully introduce new strategies and approaches to solve messy challenges through the use of disciplines such as systemic design, foresight, and design facilitation.

Marlieke is a public sector leader, author, and speaker in social innovation, service design, and systemic strategy across academia, civil society organizations, and government. Her work reflects a deep commitment to developing service and systemic design processes and capabilities across silos and different world views. Marlieke was at the forefront of the Labs movement in Europe in the early 2010’s, where she co-convened the first international social Labs gathering (Lab of Labs). She developed various Lab methodologies,

designed and led social Labs in collaboration with municipalities, philanthropists and community activists and encouraged critical thinking about Labs by writing various publications (ie. Lab Matters, 2014, Lab Craft, 2015). Currently, Marlieke leads a service design chapter in the Ministry of Citizens' Services in the British Columbia Public Service. Her dedication to open, creative, and equitable futures drives her passion for meaningful collaboration.

Tim Draimin is chair and a founding board member of SIC. He is senior fellow at Community Foundations of Canada (CFC). From 2008-2017, Tim was the Executive Director of Social Innovation Generation (SiG), a partnership founded by McConnell Family Foundation, MaRS, Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN), and the University of Waterloo. SiG focused on strengthening Canada’s enabling ecosystem and public policies for deploying social innovation for system change. Tim is a frequent advisor to government, non-profits and business. He is a board member of Trico Foundation and past board member of Social Innovation Exchange (SIX), Centre for Social Innovation (CSI), Green Economy Canada, and Partnership Brokers Association (PBA). He was a member of Grand Challenges Canada’s scientific advisory board. Tim convened the Canadian Task Force on Social Finance, which proposed a seven-point agenda for mobilizing private capital for public good.

What the report doesn’t quite capture is the joy, trust, support, and deep connections shared amongst everyone that attended the Future of Labs. Delegates noticed a maturing in the field in Canada, less competition and a sense of real enthusiastic support for each other even when there was disagreement. This is promising for field building into the future and was maybe the best part of the future of labs.

The Primer, downloadable from the FOL website1, is a scrappy synthesis of the history of Labs, trends in the field, data from a survey and focus groups with diverse Lab practitioners, a collection of inspiring examples of Lab practice, and some provocations to consider. The Primer served as grounding knowledge and context for the FOL gathering that took place in May 2024 and supports wider knowledge sharing around what Labs are, when they might be helpful, and what principles of good Labs look like. Since the FOL gathering on the island and in writing this final report, we continue to find that the Primer has very clear history and knowledge to review on the what, why and how of many diverse types of labs.

This report provides summaries of each of the five conversations held at the FOL gathering. Each summary includes a brief description of the question(s) explored and how conversations were facilitated, as well as a synthesis of the raw data captured from participants, summarising what was heard and initial impressions. Facilitators of the conversations were consulted on the synthesis summaries. At the end of the report we discuss potential working conclusions, recommendations, next steps, and questions for the field to consider.

In striving to not have to reinvent the wheel each time labs are explored, we hope the Primer will support funders of labs, lab practitioners and curious explorers interested in learning about the niche of labs for some forms of systems change.

When reviewing the insights captured during the gathering, we looked for recurring themes, interesting alternative perspectives, and tensionsthese are reflected in the conversation syntheses. It should be noted that the data quality from most of the conversations is quite scrappy, often captured on sticky notes and flipchart paper. We have done our best to triangulate insights based on the raw data, break out group conversations the rapporteurs were immersed in, and group plenary to identify key themes shared in this report.

Across conversations at the FOL gathering there was some disagreement amongst participants on the role Labs play in creating social change and justice. Generally there is agreement that Labs are aiming to produce social change. But there is some disagreement around how that change is best produced and stewarded through Labs. The tension that arose re-emphasised the tensions highlighted in the Primer between Critical Social Justice and Social Innovation approaches2. We’ve shared the following chart from the Primer as a brief reminder of the two different perspectives, how they are similar, and different.

As Struthers (2018) highlights3: each approach is “based on a distinct set of assumptions leading to different strategies and ways of organising for social

1 https://www.actionLab.ca/future-of-Labs-gathering

benefit.” The social justice perspective that came through at FOL, suggested that the future purpose of Labs is to produce deep transformational change through a restructuring of power in systems which often involves deconstruction of the old system and working slowly and relationally. In contrast, other

perspectives at FOL emphasised engagement with multiple stakeholder groups (being careful to centre people with lived experience throughout), had an eye towards adapting proposed solutions to help with scaling, and emphasised co-designed solutions (with co-design coming in many forms).

Summarized from Struthers Article.

Note this is an attempt to highlight rough distinctions for the purpose of sparking reflective dialogue not to create false dichotomies or rigid definitions.

→ “New and fluid”, relatively new approach with loos(er) theoretical associations

→ Focus on social(group) problem solving

→ Asset based, opportunistic frame that aims to amplify what is working in a system

→ Results oriented towards improved social outcomes

→ Preference for loose and evolving language to leave room for ‘getting to action’

→ Historically did not emphasize the inclusion of marginalized groups nor prioritize a deeper social analysis of power and privilege

→ Often deliberate about creating relationships amongst very different organizations or individuals

→ Generative orientated

→ “Established and entrenched”, long(er) history more robustly rooted in theory

→ Equity and justice as primary goal of practice

→ Skeptical approach to systems of power“critical theory” approach that aims to identify problems or needs as flaws to be resisted or corrected

→ Results oriented towards access to justice and equity

→ Emphasis on precision in language that supports clarity and insight into nuance

→ Intentional inclusion of marginalized groups and prioritizes a deeper social analysis of power and privilege

→ Seeks allies with common values

→ Looks at issues and systems through lens’ of oppressor/oppressed

2 See page 37 of the Primer

3 Struthers, M. (2018). At odds or an opportunity? Exploring the tension between the social justice and social innovation narratives, The Philanthropist Journal.

We think it is important to keep these differing perspectives on change making in mind as you read the report as, in many instances, these assumptions underpin the tensions and disagreements in the field today. For example, one way these different perspectives showed up during the gathering was in Conversation 3 around what’s reasonable to expect from Labs. During this conversation scaling came up. Reflecting tensions between these two perspectives, some delegates felt Labs should de-emphasize scaling of solutions while others felt scaling was an essential part of a Lab’s theory of change. Another example of when this showed up was in Conversation 2 around the Niche of Labs with some delegates feeling like Labs’ central role is in facilitating transformation, and in doing so, they could have a role to play in ‘hospicing’ old systems as well as imagining new ones.

We recognize it may be difficult for the field to reconcile the tension between critical social justice and social innovation approaches as the theoretical and philosophical underpinnings are quite different. Attempts to bring both perspectives together is honourable, but continues to show it is very challenging for lab designers and stewards to know when to switch and surf the tensions between the two.

Given this, a question we’re grappling with is: how do we craft working conclusions and possible pathways forward that are broad enough to resonate with practitioners across paradigms of change, but still succinct enough to be coherent to incumbents (funders), and communities who could benefit from Labs?

In this report we’re being brave to put out some draft collective statements. We recognize they might loosely fit but not directly align with the approaches taken up in individual Labs. We’ve designed the statements with what we hope provides some coherence and clarity but also space for Labs to write in their own unique

approaches and theoretical underpinnings. So, if you decide to use these collective statements in your own work, we invite you to customize them, contextualizing them within your own unique theory of change. An example of what we mean is below.

Collective Definition of Labs: Social Innovation Labs hold space for diverse change-makers to sense-make, generate, develop and test a portfolio of promising solutions to address complex societal challenges in a way that is collaborative, experimental, iterative, and systemic.

In our Lab context diverse change-makers means l . Promising solutions means l We hope to support systems change by l OR

In our Lab context diverse change-makers means l . We don’t use the term ‘solutions’ in our Lab, instead we use l because l We believe systemic change happens by l

It's likely there will continue to be diversity in the theories of change taken up by Lab practitioners. So, as an evolving field, we’ll need to continue to be bold in grappling with this really tough tension. One place to start might be to push each other to get clear on the theories of change we are drawing on, their utility, and the implications of that perspective (who’s left out, what does it mean for people today, etc.). So at a minimum we can start to better understand how each of us is working in similar and different ways.

What do we mean by Social Innovation Labs?

Why it matters

Social Innovation Labs can’t be everything and there can’t be ‘one version’. What is our working definition of Labs? What are the core attributes? What are Lab types and contexts? The purpose of converging on a working definition of Social Innovation Labs is not to establish a rigid, set standard but rather to try and understand the unique and shared attributes of this specific approach to change making, inclusive of its many variations.

What are Labs’ unique contributions to social change?

Why it matters

Social change, innovation, and transformation require multiple types of change strategies, such as policy advocacy and activism, community organising, multi-stakeholder engagement strategies, and social entrepreneurship, to name a few. With a variety of social change approaches, each with its own unique strengths, limitations, and contributions, we think it can be helpful to explore the ‘niche’ for Labs amongst them. How do Labs distinguish themselves from other social change approaches? Under what conditions is a Lab approach appropriate and when might other social change approaches be better?

What’s reasonable to expect about the scale, pace, and durability of Lab results?

Why it matters

When asking what is reasonable to expect from Labs, the reality is, we really don’t know. Unsurprisingly, our expectations often surpass the reality of what it truly takes to make progress on complex challenges. Let’s see if we can do this better so as to better manage expectations by everyone involved and design better Labs.

What are the capabilities, mindsets, methods, and skills needed to design, manage, and evaluate high quality Social Innovation Labs?

Why it matters

As we look to collectively vision and offer possible next practices for the field, we feel it’s important to reflect on and name the practices and processes that support meaningful and impactful Labs. What capabilities are

‘core’ to Labs, what are important and relational, and what are deeply situational/context specific? What do Labs and Lab practitioners need to get substantially better at in the next 5-10 years?

Conversation 5: What are the Necessary Conditions and Supporting Ecosystem for Social Innovation Labs to Thrive in Canada?

What kind of ecosystem do we need to ensure that the Lab movement – and individual Labs – thrive?

Why it matters

As practitioners we understand that Labs have a place in a larger ecosystem of systems change. How might we articulate a pathway to better resource and deepen the Lab field; and identify synergies and pathways through policy, finance, culture, supports, markets and skills development, to how our collective efforts can contribute to positive system change? Where are we now with this type of ecosystem? What are the things we need to do next?

Hollyhock on Cortes Island sits on the traditional territories of the Klahoose, Tla’amin, and Homalco Nations.

The gathering began in a deeply intentional and relational way. On the first evening, delegates gathered in Olatunji Hall, where we were warmly welcomed by Brenda and Rose Hanson of the Klahoose First Nation. Brenda and Rose opened the gathering in a meaningful way, sharing about the inspiring land we were gathered and learning from, including their ancestors and stories. Delegates were welcomed through a prayer led by Rose, and Brenda honored us with a beautiful song.

In preparation for the gathering, delegates were invited to bring with them a Lab-related artefact that represents something they’re proud of, that puzzles them, or that seems promising related to the FOL. Examples included photos, a quote of something said by a Lab participant, Lab publications, written stories, and artefacts that are connected to the land delegates worked on or representing a collective they worked alongside.

Delegates gathered in small groups, introducing themselves and sharing the stories behind their artefacts. These artefacts were then displayed on a table, each accompanied by a description, for attendees to view and reflect on throughout the duration of the gathering.

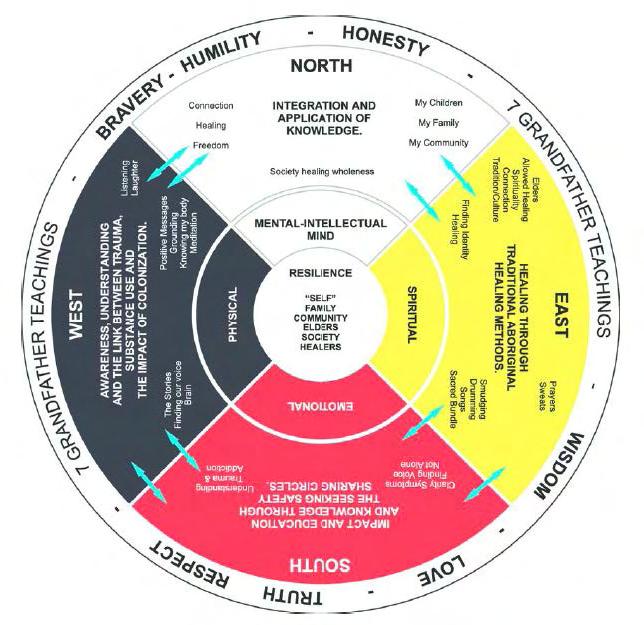

The morning of the second day, Diane Roussin highlighted the importance of connecting with all aspects of our beingness - spiritual, physical, emotional, and intellectual selves. Diane reminded us that relationships form the foundation of our work and our being together. As part of this grounding, tobacco, one of the four sacred medicines, was offered as an invitation to enter into relationship with one another. Each participant was asked to put their thoughts and energy into the tobacco, which was then used to create a group tobacco tie - a symbol of our collective commitment and relationship. Additionally, individual tobacco ties prepared by the Winnipeg Boldness team were distributed, inviting each person to engage personally and meaningfully. Diane concluded the opening with an Anishinaabe song, its translation “come in, all of us”, called in our ancestors and all present to do this work in a relational way.

“When relationships are strong you can go into complexity fast and get shit done.” Diane Roussin

FOL delegate, André Fortin, began the morning of the second day by sharing a song he created, incorporating sounds from the island.

Delegates were encouraged to consider what they hope to take away from the experience and the ways they can contribute. Throughout our time at Hollyhock, and following the event, delegates were provided opportunities to share their thoughts about how what they are learning relates to their work, what potential it opens up, and what next steps we could take together.

→ Let’s think inside the circle

A teaching shared by Diane Roussin, we emphasize creative thinking inside the circle to create space for relational ways of being and foster intuition, allowing us to be agile and responsive to our community.

→ Let’s strive for coherence more than consensus

We accept and understand there will be differences in opinion, and disagreements. Our space is one of mutual respect, where disagreements are acknowledged but not required to be resolved. Let’s recognize if there is something called Labs into the future, it needs to be clearer to us, to system leaders, to funders, to communities, around what Labs are, what niche contexts they are helpful for, where they shouldn’t be used, and what is reasonable to expect from Labs. Let’s aim for coherence.

→ Let’s embrace complexity with boldness and humility

A ‘both-and’ mindset is likely wiser than ‘either-or’. In times of chaos and uncertainty, it’s the stories we share and the relationships we nurture that guide us. We approach challenges with boldness, fearlessness, and kindness while being humble and striving to minimize harm. Remember, making Labs better isn’t really about us - AND it’s a bit about us.

→ Let’s think systemically and act relationally with kindness

By both centering lived experience of Lab stewardship and listening to whole system insights, we can better notice tensions and consider implications for decisions and future directions. Let’s also be considerate

of the time we have on the island. Many volunteer leaders have offered to design and facilitate the 5 conversations despite their limited time. Please try to show up on time. We will work hard together during the day, and play hard during meals and the evening to strengthen relationships. Look out for each other in our community and support.

→ Let’s hold space for intuition, questioning AND bold action

Let’s be careful not to believe everything we think and feel - AND also trust our intuition. Let’s try to recognize we all have preferences, biases and experiences we bring. There is a paradox in trusting our gut and also checking our biases as we move forward together. Let’s be aware that good questions are powerful for change - AND let’s recognize answering questions with more questions is a privilege, safe, and we can avoid critique if we just keep proposing deeper and deeper questions without bold action attached. Many communities and systems cannot afford endless questions as an answer to complex challenges. But there is a paradox in that we need the right questions to point us in good future directions too.

→ Let’s be open to the old, the new and a dash of surprise - the emergent

Canadian Social Innovation leader Al Etmanski suggests for innovation, or new pathways in complex systems we likely need to be mixing ideas from history, being open to new possibilities and be open to surprises that will emerge through all of our sharing, exchanging, learning and being curious together about the FOL.

→ Let’s try not to make Labs about everything

There is kindness in clarity and creating boundaries on scope. Staying true to the original intentions and purpose of FOL helps to ensure we design and generate an offering for the FOL that transcends individual interests - for Lab processes and systems to work better.

→ Let’s recognize we don’t have to figure everything out in 2 and a half days

In our time together we aim to both strengthen relationships, coherence and insights around the FOL, but we don’t have to figure it all out. We can’t. There will be a post gathering survey to share thoughts. There will also be opportunities to share ideas on the island with our podcaster. With funding we also hope to have short, think- pieces/blogs related to the FOL from experienced Lab leaders who join the event. Exactly what will happen after and what organizations and leaders will pick up the threads and further develop them is still to be determined and will emerge from our collective.

Led by Ben Weinlick and Aleeya Velji

Together Ben and Aleeya shared the following definition and core attributes of Labs. This version had been refined based on feedback from a survey that went out to practitioners ahead of the gathering. FOL participants again had an opportunity to react to the definition and offer feedback. Ben and Aleeya shared that so often in these types of gatherings, groups can spend the whole time wordsmithing a definition and not get to the depth required. Instead of large group re-writes of the definition, a canvas with voting options and suggested upgrades was presented to everyone and everyone invited to engage in edits over the two days on the canvas.

Participants were encouraged to consider that a decent definition should feel okay for stewards/ practitioners of Labs, but maybe more importantly, it should help funders, communities, incumbents, and systems leaders to see more clearly the potential value, unique niche, and purpose of Labs. The implication being that a definition we suggest for others may not feel exactly right for deep practitioners of Labs, but we should embrace that, because as one of the FOL principles stated, “the FOL is kind of about us (practitioners) but also not about us”. Delegates were reminded that FOL is more about honing the next generation of problem-solving labs that help communities and systems to be better. We are codesigning the future of labs sort of for ourselves, but more to offer robust ways of tackling wicked challenges when the niche of labs might be needed.

Words highlighted in blue are changes based on the feedback from the FOL pre-gathering survey (see below Feedback on Working Definition) and convening group.

Social Innovation Labs hold space for diverse change-makers to sense-make, generate, develop, and test a portfolio of promising solutions to address complex societal challenges in a way that is collaborative, experimental, iterative, and systemic.

Minimum core principles of Social Innovation Labs:

→ Focused on complex societal challenges

→ Learns from diverse perspectives from across a system, while centering those with lived experience

→ Explores collaborative ways of working on a shared complex challenge

→ Systemic in thinking and action

→ Experimental in iteratively developing and testing possible solutions, ideally in real life and at a minimum in realistic settings

→ Aim at exploring root causes of complex challenges and then generating possible solutions and pathways from leverage points

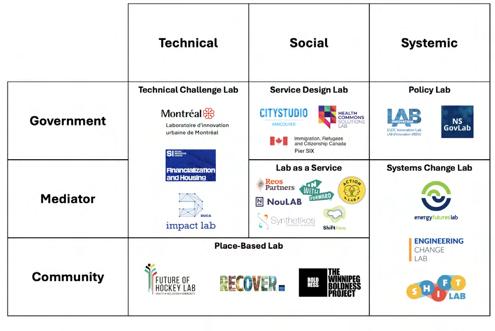

Another really important piece to the definition of labs is to consider the different types and contexts of labs that were identified in the Primer. The working definition aims to be a kind of mothership that unites across all the diverse and varying types of labs. In the Primer, some of the types of labs identified were Technical Challenge Labs, Service Design Labs, Policy Labs, Systems Change Labs, Place Based Labs, and Labs as Service (consultancies that do labs). FOL needed to consider if a working definition could hold all types of Labs in order to help with coherence and communication about Labs. Also it was noted from the

Primer that FOL consciously left out accelerator labs, and social enterprise incubator labs as those labs tend to not hold space for diverse change-makers to sensemake a system challenge, nor create space to hone the problems to be worked on from multiple perspectives. Social enterprise and accelerator incubators can be important in the portfolio of systems change methods and important for scaling certain types of solutions, but they don’t quite meet the definition criteria above for social innovation labs. It was important for FOL to get better at discerning these distinctions to improve coherence and communication around labs. As Carl Sagan said, "If all ideas have equal validity then you are lost, because then it seems to me, no ideas have any validity at all."

From the dot votes, FOL delegates felt the upgraded definition was roughly right.

Roughly right, a few flaws but I’m supportive of the direction

people

This feels good, I’m all for it.

Not supportive, there needs to be a serious overhaul

Some recurring language suggestions included:

→ Changing the language of “changemakers” and “solutions” (examples: interventions, proofs of possibility, potentials, pathways, approaches, shifts, probes of systems, levers)

→ Rather than ‘including’ people with lived experience, ‘centre’, ‘grounded in’, etc.

Led by Darcy Riddel and Patrick Dubé

When and how are Labs most powerfully employed? WHAT HAPPENED AT THE GATHERING

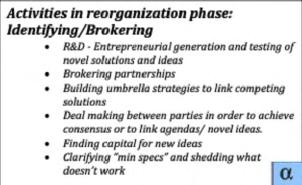

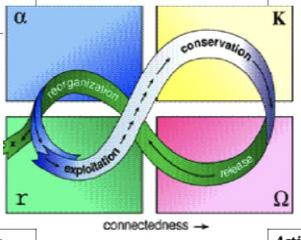

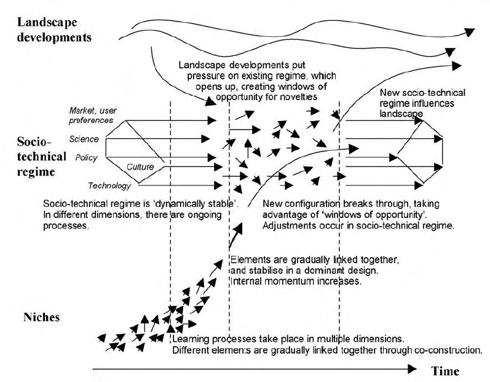

Darcy and Patrick provided four social change frameworks to support locating a Lab approach:

4. Multi-Layer Perspective

Participants selected one framework and used the following questions to explore it with a partner:

→ What are the niches (where) Labs can contribute to this system change framework?

→ What is/are the unique or most interesting niche(s) for a Lab using this system framework?

→ Why there?

→ Under what conditions or context can Labs best create value at these locations?

Pairs then formed a foursome to share their reflections and further discuss the following questions:

→ What is the unique added value of Labs in relation to other modalities (i.e. collective impact, social enterprise, social movement, innovation challenges, accelerators, incubators, mission oriented innovation, etc.)

→ What can’t/shouldn’t the Lab do in these action spaces?

→ What happens when Labs are conflated with other social/system change modalities? Where does a Lab responsibility end into these action spaces?

Based on the reflections shared back by pairs, it appears the Two Loops Model and Medicine Wheel were primarily discussed by delegates.

Resoundingly we heard that one niche is that Labs are good at convening diverse stakeholders and cultivating strong trusting relationships. The act of convening was seen as one of the most important things Labs practitioners do, and it is done with great intention, care, and time. Participants shared that the intentionality around the invitation, the container, and what happens within it is something that sets Social Innovation Labs apart from other approaches.

“The social function of Labs is more important than what comes out of the Lab; it re-socializes people to be in a different way.”

FOL Delegate

“Trust building is so powerful in a Lab process and something that transcends the Lab process.”

FOL Delegate

Delegates highlighted that Labs support depolarization by helping bridge divides and building understanding across diverse perspectives. While Labs often strive to be more impartial, they are guided by a clear vision, with vision holders - such as Lab leaders and facilitators - who excel at articulating the purpose and continually bringing participants back to the core “why” behind the Lab. This balance between neutrality and purposeful direction supports Labs ability to foster understanding and collaboration across diverse perspectives.

“Because Labs have a central sustaining stewardship, it supports things moving forward even when some stakeholders are not cooperative.” FOL Delegate

Several groups surfaced that Labs are fundamentally about learning

→ Learning about each other and the system

→ Learning about what’s needed to transition to better future states (mindsets, tools, processes)

→ Learning how to work collectively – when we do it well, people are bought in

“If you don’t learn anything, you’re not letting go of anything.”

FOL Delegate

“Labs are a space for learning about and working through shit.”

FOL Delegate

There was discussion around the niche of Labs being about transformation rather than focused on solutions to problems. Some participants suggested moving away from the solution/problem dichotomy, as focusing solely on solutions might limit the transformative potential of Labs. However, there was not consensus on whether Labs inherently aim for transformation. What transformation meant likely had varying interpretations in the minds of delegates. Most commonly, conversations on transformation entailed notions of transitioning from old system paradigms to new system paradigms. How much of the transformation blended old and new systems was rarely articulated. But the general notion with transformation was a deeply generative one with less pragmatic attention to what a stakeholder group in a Lab might need to change or transform on shorter term horizons.

Some argued that we should let go of labs focusing on ‘solutions’. This could take the form of using prototyping and testing as tools to better understand the problem, rather than identifying solutions. In this view, prototypes serve as creative probes to explore the system(s), helping reframe issues and check assumptions, which can be more effective than simply talking about the problem.

“Is transformation inherently a part of Lab work?” FOL Delegate

“Is a solution orientation (as opposed to a transformation orientation) a Lab’s kryptonite?”

FOL Delegate

This lively discussion also brought up questions surrounding the role of Labs in transformation. Some delegates wondered if Labs of the future could occupy a ‘hospicing’ role, supporting an old system to die and the transition into new paradigms. This idea suggests Labs could engage in the act of letting go, helping to ‘end’ systems. Some questioned whether Labs could be a space for navigating grief scenarios, offering support not just for new possibilities but also for the process of closure and endings. Depending on the size and connections of a system(s), other delegates raised pragmatic considerations. Do Labs and Lab practitioners have the, often advanced, skills required to hospice a system(s) with integrity? Do they have the sphere of influence, relationships, and authority to do this work? Who gets to decide a system is ready to die? Whose perspective matters and whose does not? How do you equitably manage the countless perspectives on what needs to die or stay alive in a system(s)? One delegate emphasized that hospicing should always be considered within the broader arc of what Labs are aiming to do - bring about positive social change. They cautioned against replacing what Labs currently do with hospicing, suggesting that hospicing might best be considered an ‘add on’ to what Labs already do:

“If you’re just hospicing, I don’t know if that’s a Lab. If you’re just saying goodbye, and not saying hello to anything, what are you doing?”

FOL Delegate

Whether labs begin to take on the role of hospicing more fulsomely or not, delegates seemed to agree that there is merit in engaging with hospice oriented thinking and tools as part of a Lab process as, at a minimum, they might help generate insights around how to transform and transition systems from old to new.

Some delegates pointed out that Labs have not been as effective at culture change. One delegate referenced an article that outlined three primary ways change comes about: markets, cultures, and policy4. It was felt that while some Labs are good at policy change, they are seen as less effective in shaping cultural systems change, which is where social movements tend to thrive in driving social change. Systems change is deeply rooted in culture, beliefs, and values, but some delegates felt Labs are often not centred there for that kind of change.

Delegates surfaced that Labs are inherently holistic and generative in their approach. Some people felt the primary contribution Labs make is identifying root causes to complex problems while others challenged this perspective. One delegate remarked:

“I think we say we are good at identifying root causes. I’ve said it lots and thought our labs were doing great at it. But now I'm less and less convinced we're actually good at it. A tension may be that we need to acknowledge this more. I have a hunch that AI that we don’t quite have yet, combined with human community sensemaking will help more in the future to get to better root cause analysis. People's lived experience stories are often pointed to as the best sources of finding root causes, but I actually think now, it's not so much the case that we’re

getting closer to real root causes. There is deep bias everywhere and it’s harder than ever to navigate well. Whole systems perspectives, lived experience centred, and really good literature reviews are needed. Good labs have always said that. But I think the field is going to need to develop some additional ways of honestly looking for real root causes to design pathways or new systems around”

As this delegate raises, perhaps there is more work to be done to continue to get better at identifying root causes.

As a whole, this conversation highlighted the many tensions that persist in the field related to the role Labs play in broader change making efforts.

4 Surman, T. (2018). Unlocking Canadian Social Innovation: https://socialinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Unlocking-Canadian-Social-Innovation-.pdf

Led by Mark Cabaj and Marlieke Kieboom

How do you create a shared narrative around what’s appropriate to achieve? We feel we need to get better at articulating: ‘what does progress look like and how are we going to get there (knowing it will evolve)?’

The session was meant to more deeply explore two of the four ideas about what Lab stakeholders should consider reasonable to expect proposed in the FOL Primer5.

To do this, participants were active in two exercises:

EXERCISE 1: MOST SIGNIFICANT CHANGE PAIRED INTERVIEWS

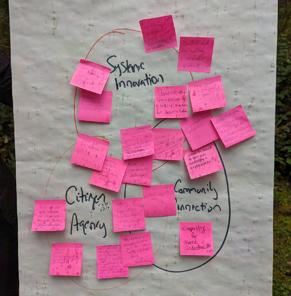

Participants ‘paired up’ to interview each other on the most significant result they’ve seen come from a Lab and why it's significant, then posted it on the CONVERGE Impact Diagram (see below). If the result did not fit in one of the existing CONVERGE categories participants were invited to create a new category.

See Appendix A for examples of participant insights during this session.

EXERCISE 1: MOST SIGNIFICANT CHANGE PAIRED INTERVIEWS

Participants were invited to do a ‘soft shoe shuffle’ locating themselves on a continuum with the following extremes:

1. In the future, Labs should emphasize developing and testing solutions to complex challenges that can/should be scaled more broadly

2. In the future, Labs should emphasize developing, testing, and - if appropriate - sustaining helpful solutions that work locally, and not worry about broader scaling beyond place.

5 The Primer is downloadable from the FOL website: https://www.actionLab.ca/future-of-Labs-gathering

1. Labs generate (at least) four broad types of results

Participants concluded that the four types of results represented in the “Lab Results Diagram” developed for the 2018 CONVERGE Final Report and in the FOL, were

LAB RESULTS DIAGRAM

SYSTEMATIC INNOVATIONS

BUILDING CITIZEN AGENCY COMMUNITY CONNECTION Supporting prototypes to scale Supporting system leaders

IMPACT

“roughly right”. They mapped the vast majority of their post-it notes, which summarized the significant results that emerged out of their conversations, against one or more of the types of results. In an informal poll following the mapping exercise, most participants voted that the visualization offered a ‘roughly right’ framing of Lab results.

PARTICIPANT PLOTTING OF RESULTS

However, many participants pointed out ways that the description of these outcomes could be more fully elaborated. Some of the feedback includes:

Building Citizen Agency

Increasing Lab participants’ confidence, skills, and commitment to participating in civic life and the change process. This is not only necessary for a productive Lab, but it’s an outcome that reflects a commitment to building a vibrant, inclusive, participatory democracy.

Challenge the status quo, consider improbable futures, unlock creativity, and encourage transformative thinking.

Strengthening Community Connections

Systemic Innovations

Impact

Strengthening the connections and relationships between diverse stakeholders encourages people to see issues through a variety of different lenses, enhances a sense of collective agency, and can build a constituency for making change.

Expanding the set of quality solutions to a complex challenge in a way that is informed by diverse perspectives, systems thinking and based on a systematic process of surfacing, developing and testing possible solutions.

The tangible progress made on complex challenges (e.g., more equitable employment, protecting biodiversity, better housing) and changing the deeper systems that hold them in place.

Acknowledging and trying to address power imbalances.

The process of developing and testing solutions is based in - and done by and with - community and key stakeholders.

Expanding the set of quality solutions

An emphasis on transformative systems change at a scale that addresses the poly-crises.

2. Lab stakeholders have different preferences for the core purpose and/or results of a Lab

Participants’ general agreement about the types of results that Labs can generate did not translate into a consensus on what results should be most central in designing, implementing, and evaluating Labs.

Some felt strongly that building citizen agency and connections for participants is the most important outcome of a Lab. They point out that any given Lab cannot ‘guarantee’ progress on an issue and warn about the dangers of ‘solutionism’ (aka a belief that all problems have one or more technical solutions):

“The idea that it’s not in our control – once you’ve done the inner work it can all happen.” FOL Delegate

“Not focusing on solutionism and prototyping – but rather the inner work needed; connectivity work, civic agency work." FOL

Delegate

Other participants felt that coming up with systemic innovation that can positively impact stubborn societal challenges should be a central concern of Labs. While civic agency and creating connections are important outcomes, they argued, they are also building blocks for unleashing people’s creativity and committing to getting at the roots of stubborn challenges:

“The point of a Lab is to develop effective responses to real issues, to make change. If Labs don’t try to do that, then why are they called Labs? They have to do more than just community mobilizing."

FOL Delegate

Yet other participants debated the merits of embedding Labs in a strong social justice and transformative change orientation - using Labs as ways to ‘hospice’ the seeming decline of our current systems while developing entirely new ways of doing things - versus trying to ‘shrink the focus’ to developing more immediate responses:

“You can’t really change some of these things until you change the underlying structures, like capitalism and racism. It’ll just be window dressing if you don’t.”

FOL Delegate

“We have to - and can - get microplastics out of the ocean right now. We can’t wait - and don’t have to wait - for a transformed world to do that.” FOL Delegate

The richness of the debate on what comprises the ‘best’ results of a Lab revealed, in the words of one participant, a paradox in the field:

“We all believe in inclusive and pluralist communities and societies, yet we are having a hard time manifesting that ourselves. Can’t we say the field is united on the importance of Labs and its core features, but that there is a lot of differences in what we focus on and why, and that is ok because it reflects a diversity in the field?"

FOL Delegate

3. The emphasis on whether or not to scale depends on the purpose and context of the Lab

The shoe shuffle exercise uncovered a range of opinions and ideas on whether participants felt that Labs should scale or not scale whatever promising solutions emerge from their efforts.

→ The majority of participants (30 plus) felt that Labs should focus on supporting community actors to develop (and sustain) solutions that work in their unique context, and not be overly concerned about their scalability in the design of the Lab,

Lab should be designed to develop and test solutions that can be scaled broadly.

→ Scale of polycrises requires us to scale solutions.

→ Aiming or scale may make it easier to mobilize resources and actors.

Labs should focus on developing local solutions that address local issues, and not worry about scaling to other contexts.

→ More emphasis on the directions and needs of community.

→ Solutions more likely to reflect unique local context

→ Expands ability to increase agency and connections of local participants.

→ Easier to mobilize funding for experimental - than scaling - work.

→ A very small number of participants (roughly 5) felt that Labs should be designed - and expectedto scale solutions.

→ A medium sized group (roughly 12) expressed uncertainty and/or emphasized that the answer ‘depended’ on the situation.

The rich discussion that emerged when people shared their rationale for their ‘shuffle position’ revealed that (1) it may be best to avoid the urge to assume there is a ‘right or wrong’ answer to the question of ‘to scale or not to scale’ and (2) instead be clear on the specific context and larger change strategy in which the Lab approach was being used. Two situations stand out: largely local Labs and issue-based, non-local Labs. See Table 1.

→ May miss solutions that might work in 1 community simply because they are not scalable.

→ May encourage one-size-fits-all thinking and solutions, and even imposing solutions on diverse communities.

→ May limit the number and variety of local actors who want to be part of the change process.

→ Scaling requires different skills and people than early experimenting.

→ Difficult to mobilize resources for scaling effort.

→ May limit broader thinking on how to approach the issue

→ May not address larger nonlocal systemic forces that underlie local challenges.

→ May not make it easy to mobilize resources if only focused on one community.

Non-local Labs, where participants aim to work together to solve an issue that cuts across communities.

Can include communities, but the emphasis is on surfacing scalable solutions.

Local/community Labs, where stakeholders are primarily local/community based.

May surface solutions that might be worthy of scaling, but that is not the primary purpose.

“Labs are expensive and slow, I can’t justify the way of this work to not be for some form of scale."

FOL Delegate

“Considering a specific context –only place to see if it’s actually making a difference. Yes there might be important lessons to then share and scale – but I’m not sure that’s the work of the Lab. There is danger in “this is important to see in the world” – not sure that’s the work of the Lab." Cheryl

Rose

“The scales of the issues of the polycrisis - if we work community by community we will die quickly."

FOL Delegate

“We owe it to the Lab to be in service to it in it’s specific time and context – if we’re already thinking about other contexts (ie. scaling) how are we in service to that specific context. Scaling it becomes a different project."

FOL Delegate

“I feel the weight of the investment all the time. You should be thinking about scaling from the outset."

FOL Delegate

“The learning through the ecosystem is very context specific." FOL Delegate

4. We are still working on a shared understanding of what we mean by ‘scaling’ in innovation work

The discussion about whether Labs should - and should not - make scaling their results a priority revealed that practitioners have different levels of understanding and opinions about what it looks like in practice. Some of the discussion highlights include:

→ Several participants seemed to assume scaling meant a focused emphasis on “replicating” solutions elsewhere, while others referred to a broader conception of scaling which includes the following attributes:

> Scaling out - expanding impact by supporting its adoption by others (including replication).

> Scaling deep - capturing hearts and minds of broader networks and society to support the idea behind the innovation.

> Scaling up - changing policies and systems to support the innovation.

→ Other participants surfaced the different ways to support the ‘scaling out’ of Lab results, emphasizing that it's not only about “replication” of models or solutions, but pollinating the ideas and results so that other social innovators can “riff on” and “reshape them” for their own contexts.

→ Yet participants pointed out Lab stakeholders can also scale the learnings that emerge from their efforts, in addition to specific promising solutions (e.g. a model, a policy, a new institution):

“We

all have a role in scaling. Taking something from one domain and inputting

it into another domain. Not the role of Labs to take something – responsibility to mobilize and share the knowledge in context so that others might learn quickly. It’s a push vs. pull. Don’t scale the prototype – scale the learning.

Scaling vs.

pollinating." FOL Delegate

“The moral imperative – to think about sharing that out, and that’s a form of scale. It’s not replication (ie. cookie cutter). If it does look like something that can be useful, share that out. We don’t talk to each other enough.” FOL Delegate

“Part of what we ask people to do is to take that away in their work. That’s a form of scale. Deliberately a part of our theory of change. The question of what do we mean by scale and replication? They’re not the same.” Sarah Brooks (Energy Futures Lab)

→ Finally, some participants pointed out that there are different perspectives on scaling that may be rooted in different worldviews (e.g., Indigenous perspectives) and should take into account that scaling ‘anything’ depends on the inner changes and transformation of Lab participants.

One veteran Lab practitioner captured one of the challenges of building the Lab field in this next chapter of its development:

“There are a lot of people relatively new to the discussion of scaling at this event, so it feels like we are covering old ground, and maybe our field is not on the same page on some of these basic things. At the same time, the discussion of scaling

solutions and learnings is new and indicates that we are advancing: we did not talk about this 10 years ago much. That's progress!”

Additional resources on scaling:

→ Everyday Patterns for Shifting Systems Right Scaling https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_ file/0024/1867002/Right-Scaling_Patterns_ TSI-and-GCSI.pdf

→ Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep Strategies of Non-profits in Advancing Systemic Social Innovation by Michele-Lee Moorea and Darcy Riddell (2015)

→ Problematizing Scale in the Social Sector (1): Expanding Conceptions An opinion piece by Gord Tulloch https://www.inwithforward.com/2018/01/ expanding-conceptions-scale-within-socialsector/

Led by Alex Ryan and Keren Perla

What are the capabilities, mindsets, methods, and skills needed to design, manage, and evaluate high quality Social Innovation Labs? What do Labs and Lab practitioners need to get substantially better at in the next 5-10 years?

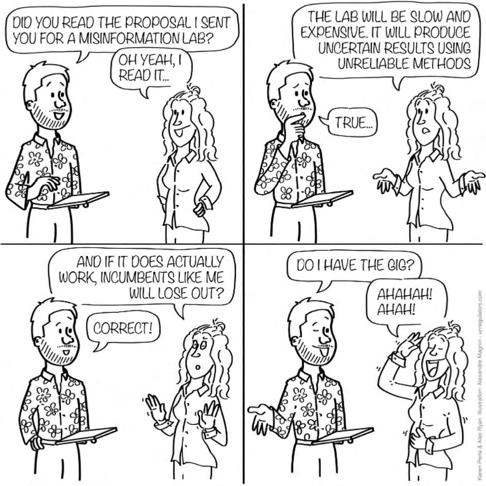

Alex and Keren began the session with a role play of a skit between an incumbent (and prospective funder) of a Lab on disinformation and a Lab as a Service consultant pitching the value of Labs. Following the workshop, they translated the skit into a series of four cartoons:

Alex and Keren’s skit surfaced amongst participants the need for a clearer value proposition for funders/ incumbents.

“Made me feel we have a branding issue." FOL

Delegate

“We have to be externally coherent"

FOL Delegate

A Provocation: Next, Alex and Keren then presented their thesis and provocation to the group. Social Innovation Labs are uniquely good at holding space for diverse groups to ideate transformational ideas for a better world. But an overly narrow focus of the Labs movement on optimizing the participant experience at the fuzzy front end of innovation has left a gulf between the promise of Labs and what they actually deliver. This makes it challenging to gain the trust of incumbents who are needed to invest in the Lab; as well as communities who are invited to vest their time, trauma, hopes and dreams in the Lab. To succeed in the coming decade, we contend that Labs need to extend their empathetic horizons to include incumbents who may legitimately fear systems change. They need to be able to get out of the Lab space and engage with much more of the community where they are at. And Labs need to progress beyond tabletop prototypes to spread and scale innovations that create measurable and attributable real-world impact over the course of decades.

Alex and Keren introduced a framework for exploring how to expand the field of Lab practices across three phases (Ideation to Scaling) and three layers (Community to Incumbent):

WHO PRIMARILY BENEFITS:

Incumbent (status quo/ institutions/power/ funder)

Lab participants (cohort)

Community & More Than Human (constituents)

Labs want incumbents’ money but not their status quo bias

Labs are arguably uniquely best at this!

Labs do engage community deeply in need-finding, but sample sizes are very small

Participants first self-organized into groups each focused on an intersection that aligned with their passion space to discuss:

→ What are your most important Lab practices in your area?

→ How might they be enhanced in the next decade?

→ What capabilities are needed to deliver on this?

In a second round of conversations, using the same intersections, participants moved to where they saw the biggest value gap where Labs need to get significantly better. They then shared:

→ What new practices do Labs need to invent / borrow / reinvent to fill this value gap?

→ What new talent is needed to do this? What new capabilities do we need?

→ What needs to be done to decolonize Lab practices in this area?

→ What existing practices do we need to retain?

It’s hard to get incumbents excited about the Lab’s scrappy prototypes

Labs are pretty great at this too!

Labs usually involve community in prototyping but not normally as designers

This is what Labs vaguely allude to as the impact in the sales pitch

Here be Unicorns

Labs can’t really do this unless they secure a decade of funding

Practices, mindsets, skills, and capabilities needed to run highly effective Labs

In the breakout group conversations, participants emphasized that for Social Innovation Labs to achieve sustainable impact, they must enhance their ability to progress beyond prototyping and contribute to scaling systems change. This requires not only a shift in Lab practices but also stronger collaborations with allied movements, partners, and funders.

Recommendations for Scaling:

→ Secure Funding for Scale: Participants noted the need for Labs to secure funding from the beginning to support diffusion and scaling. Although funding itself is not a capability, this implies Labs need to develop deeper capabilities in business development, fundraising, government relations, impact measurement, and strategic communications. Suggestions included designing innovative financial instruments and exploring ways to monetize participant networks.

→ Develop Leadership for Scaling: Several groups discussed the importance of cultivating leadership skills that can guide initiatives from ideation to broad implementation. Recommendations included expanding coaching and mentoring programs focused on systems thinking.

→ Strengthen Ecosystem Awareness: There was a strong call for Labs to better understand their role within the broader social innovation ecosystem. Participants recommended learning from other movements (social justice movements, living Labs, collective impact, challenges, missions, social entrepreneurship etc.), forming agile partnerships, and building stronger connections between Labs that excel at different stages of the innovation process.

→ Enhance Foresight for Scaling Opportunities to be prepared when scaling opportunities arise, groups suggested that Labs improve their networking capabilities, conduct readiness assessments, and maintain a library of prototypes ready for deployment.

→ Embrace Experimentation and Knowledge Sharing: Participants emphasized the need for Labs to cultivate a culture of experimentation, documenting their experiences rigorously to create a repository of use cases and best practices for scaling.

Participants highlighted the need for Labs to deliver clearer value to incumbents—such as government agencies, businesses, and established nonprofits— as funders and stakeholders. This involves aligning Lab outcomes with the strategic goals of these stakeholders while maintaining a commitment to social change. It also requires attention to hospicing dying systems and exapting transitioning systems in addition to incubating new enterprises.

Recommendations for Enhancing Value to Incumbents and Funders:

→ Deepen Relationships with Funders: Participants suggested that Labs should build trust with funders by understanding their priorities, providing valuealigned proposals, and involving them throughout the process. This could involve profiling different funder types, crafting targeted value propositions, engaging funders in Lab governance, and broadening the range of capital accessed.

→ Deliver Strategic Insights and Solutions: Several groups recommended that Labs differentiate themselves by offering insights and solutions that incumbents can implement directly to enhance their social impact. This might involve actionable research insights, demonstrating policy impact, innovation partnerships, or piloting scalable solutions.

Groups recognized that participants—including Lab members, partners, and people with lived experience— should experience clear, tangible benefits from their involvement in Lab activities. Labs must create environments where participants feel valued, heard, and empowered to contribute meaningfully.

Recommendations for Adding Value to Participants:

→ Expand Roles and Pathways for Engagement: Participants expressed a desire for Labs to offer multiple ways for engagement beyond traditional Lab activities. This includes meeting communities where they are, hosting Labs in diverse settings, and ensuring engagement opportunities are accessible and inclusive.

→ Embrace Equity and Inclusivity in Engagement: Groups called for Labs to apply an equity lens to all engagement efforts, ensuring fair compensation, accessible participation, and respect for the time and energy of community members. The idea of becoming “design allies” was also raised, guiding Labs to co-create solutions with communities rather than imposing them.

There was a consensus that Labs should be deeply embedded in and accountable to the communities they aim to serve. Participants suggested that Labs focus on building trust, fostering genuine relationships, and generating multiple forms of value for communities.

Recommendations for Adding Value to Communities:

→ Deepen Community Engagement: Groups recommended that Labs move beyond traditional settings and engage communities in their own spaces. Several groups imagined future Lab processes anchored in ‘love and care for the community’ and for them to maintain their ‘authenticity’, ‘hope’, and ‘sense of possibility’. Suggestions included integrating more regular touchpoints with the broader community and adapting methods to fit community contexts and needs.

→ Focus on Community-Driven Leadership and Governance:: Participants called for Labs to emphasize local and collective governance models that empower community members to take the lead. Ideas included “rematriating capital” and rethinking whether scaling is always the right path.

→ Prioritize Decolonization of Lab Practices: Many groups highlighted the need for Labs to commit to decolonizing their practices by integrating Indigenous methods, fostering reflexive and trauma-informed approaches, slowing down to align with community pace, and using local and collective governance models.

Led by Diane Roussin, Geraldine Cahill, and Tim Draimin

Labs generate a rich array of prototypes or fully realized solutions that require ecosystem support to get purchase, to be scaled, to have the greatest impact. We believe an enabling ecosystem benefits Labs both in terms of addressing their operational needs and in creating an environment that could see outcomes achieve their greatest potential.

does that enabling ecosystem look like? And what conditions can be fostered for it to be most successful?

Participants were invited to choose one of six ‘ecosystems’ (i.e. policy, finance, culture, markets, human capital, or supports) to gather around and collectively discuss answers to the following three questions:

1. What do we have and need today?

2. What do we imagine 10 years from now?

3. How will we get there?

Is the enabling environment better than in 2018?