17 minute read

Reflections & Key Learnings

EVALUATION PROCESS

There were several moments for evaluation and reflection built into the Design by Doing 2.0 process including:

Reflexive conversations amongst members ofthe stewardship team Testing prototypes with community Evaluative interviews with community partners Focus group with stewardship committee Focus group with Bhutanese community members Community showcase

The following questions guided reflections on the process:

1) What are we learning about barriers to employment as experienced by the Bhutanese community in Edmonton and how they might be addressed? 2) How is culturally adapting the Design by Doing approach going? What is going well and not so well? Are there tensions? 3) What are the implications ofthis kind of approach? Where is the value and why do it again?

Quick Overviewofthe Design by Doing 2.0 Process (24 months)

1) Stakeholders come together - relationships established 2) Core challenge identified and scoped with the community 3) Culturally adapted lab days 4) Prototype Refinement & Testing 5) Community Showcase

33

REFLECTIONS ON THE CHALLENGE

Addressing Barriers to Employment as Experienced bythe Bhutanese Community

For the purposes ofthis lab, employment was thought of as one important piece of a newcomer’s journey towards economic integration. Economic integration, being long term, gainful employment, was the ultimate desired outcome articulated by the Bhutanese community. The journey towards economic integration includes learning English, gaining employability skills, learning about the Canadian employment landscape, holding survival jobs, and obtaining gainful, long term employment. The path towards economic integration is different for everyone and can be described more as a journeywith twists and turns than a linear path. Members ofthe Bhutanese community experience barriers all along the journey towards economic integration and therefore require different supports at different points in their journey.

In this lab, we learned that current settlement and employment supports available for newcomers are not always responsive for smaller immigrant and refugee communities such as the Bhutanese community. Communities such as the Bhutanese c ommunity face multiple barriers such as limited English Language skills, limited education, and complex socio-economic challenges. Through pre lab research, conversation, and various lab activities such as empathy mapping, we heard that the Bhutanese community faces barriers before and during employment. The infographic below highlights some ofthe barriers we learned the Bhutanese community faces (that are also similar to the barriers experienced by other smaller, marginalized newcomer communities).

34

As suggested by the multiple barriers Bhutanese community members face both before and during employment, there is a need for sustained support throughout their journey towards economic integration. The infographic below highlights some ofthe desired supports before and during employment as well as in longer term career development.

The Bhutanese community identified three unique contexts in which their members experience barriers to employment:

Atraditionalcontext:

Members with some employability skills and/or education looking to get a job through job searching, submitting a resume, doing an interview, and completing on the job training

Self-employment or micro-enterprise context:

Members looking to start a small business or micro enterprise based on personal skills such as gardening or crafting

English language learning context:

Members working on gaining increased English language fluency as a stepping stone to employment

35

REFLECTING ON THE PROTOTYPES

The prototypes generated in the Design by Doing 2.0 process reflect each ofthe three contexts identified by the Bhutanese community (see outlined above). Theywere co-designed with community to reflect their unique needs, and drew upon community strengths and gifts. Prototypes were not only designed with and by community members, theywere also tested with community! Each prototype team worked to ‘try out’ their prototype with members ofthe Bhutanese community. Read on to discoverwhat this process looked like for each team and their key learnings.

SupplementalEnglish Language Learning

To test this prototype, the team organized a ‘mock’ English Language learning class. Bhutanese community members were invited to participate in a 4 hour experience that included 2 hours of in-class instruction and discussion, a 1 hour experiential field trip to a local grocery store, and a 1 hour reflection. During the reflection participating community members were invited to share their insights and experiences through group discussion and individually in a short survey. In this process they learned:

• All participants reported enjoying the class experience and content • All participants reported finding the class useful. They thought it would assist them in learning English for employment • Most ofthe participants felt theywould be very likely to sign up for a class like this • Participants liked that the course content was directly applicable to employment

Supported Micro Enterprise

To test this prototype, the team facilitated a meeting between someone with an established relationship and strong working knowledge ofthe Bhutanese culture with a Bhutanese community member and trialled selling crafts at a local market. In this process they learned:

The guide is essential for success: Challenges cannot necessarily be predicted and without the essential support of a guide, the individual would be unable to pursue this pathway to employment. Trust is essential for success: The guide must have a deep understanding ofthe individual’s cultural background to be able to bridge between the individual’s home and Canadian contexts and must work to establish a strong and trusting relationship with the individual.

36

CommunityLed Employment Brokering

This team is still in the midst oftesting. In the first phase oftesting they assembled an employment brokering team consisting of a newcomer seeking employment, a cultural broker, and an employment connector. Together the team explored the newcomer’s career goals, current skills and talents, and completed a scan of potential job opportunities. In this process they learned: • Having both a cultural broker (someone with deep knowledge ofthe cultural background ofthe newcomer) as well as an employment connector (someone with deep knowledge ofthe employment landscape in Edmonton) is critical • Newcomers benefit when employment supports are directed both at individual and community needs • Trusting relationships are essential in building confidence and readiness of newcomers to participate in employment assistance programs • Working closelywith relevant employers ensures that interests and concerns are addressed once a newcomer is connected with them

Next, the team is o rganizing an Employment Resource workshop hosted by the Bhutanese community. In doing so they are bringing Bhutanese community members/leaders and employment agencies together to plan and execute the event. After the event, theywill coordinate a reflection session to bring stakeholders together to reflect on the experience and discuss follow-up activities.

37

REFLECTIONS ON THE PROCESS CulturallyAdapting a Social Innovation Approach

Why a social innovation approach?

Addressing barriers to employment for a multi barriered newcomer community is complex work. The following are indicators that the challenge is complex: (1) there are many people, organizations, and systems that have a stake in the challenge; (2) there is not much agreement on the nature ofthe problem, (3) there is not much certainty about what to do about the problem, and (4) there is a high degree of unpredictability. Complex challenges such as this one are well suited to a social innovation approach because of its emphasis on: (1) bringing diverse stakeholders together, (2) going deep to understand root causes, (3) creating solutions ‘with’ not ‘for’ people, (4) finding out what works using small scale tests, and (5) scaling only the ideas that show promise after testing with community.

Why culturally adapt the social innovation process?

Social innovation processes are often imbued with dominant Western approaches to problem solving. This can become problematic when seeking to meaningfully engage ethno-cultural communities as equal partner s in problem solving processes. When this is the case there is a need to culturally adapt the process so that it reflects their unique cultural context and approach to problem solving.

Foundational Elements to the Design by DoingApproach

Design by Doing 2.0 was unique in its approach. Throughout the process we endeavored to maintain an approach that was community led and culturally adapted to reflect the values and problem solving approach of the Bhutanese community. This was complex work, rife with tensions that required flexibility, adaptability, and a deep commitment to working ‘with’ and alongside rather than ‘for’. As we navigated the process the following continually emerged as foundational elements that enabled the success of this project.

38

Startingwith a Foundation ofRelationship and Trust

A process that is co-designed requires first and foremost a strong, trusting relationship between the project partners. The basis ofthis relationship must be rooted in a genuine desire to learn from and alongside a community of people. In doing co-design work there is a beliefthat the communityyou are working with holds knowledge that you do not have and therefore are important partners in understanding and tackling the challenge. Building relationships takes time and intentional effort. For this project, it was helpful that Multicultural Health Brokers Cooperative already had a well established relationship with the Bhutanese community and knowledge oftheir cultural traditions and approach.

Ways Relationship was Fostered

• Time for getting to know one another and learning from the Bhutanese community about their approaches to community organizing and problem solving were built into the process • Members ofthe stewardship communitywere invited to and attended c ommunity cultural events

Remaining CommunityCentred

Since Western ways of knowing and problem solving are so dominant, it can be easy to slip into ‘old’ ways of doing. Critical reflection, on the part of the stewardship team, was an important part of helping the project remain community centred. Remaining community centred looked like:

The stewardship team checking in with leaders from the Bhutanese community each step along the way to make sure theywere comfortable with the way the project was moving forward The stewardship team asking questions such as “who does this serve?” and “who has been involved” as decisions were made Stewardship members holding each other accountable and gently reminding one anotherwhen they had moved away from a co-design approach Working with Bhutanese community members to identify the core challenge and scope it Having two natural leaders from the community on the stewardship team, attending all planning meetings, and acting as connectors to the broader Bhutanese community in Edmonton Inviting the Bhutanese community to host and lead the lab days, decorating the space, bringing traditional cultural food, and sharing in ritual

39

Openness toAdaptingTools and Activities

A co-designed process requires one to do awaywith rigidity and embrace ambiguity. Prescriptive tools and activities will not always work in a codesigned process because they often do not reflect specific ethno-cultural ways of knowing. This means, in co-design, there is sometimes a need to culturally adapt lab tools. In Design by Doing 2.0 this looked like:

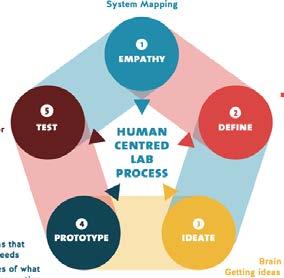

Translating tools into the Bhutanese language - we translated our rules of engagement, empathy map, and human centred design image Adjusting activities to reflect the specific ethno-cultural approach to ideation Trying out activities and tools with community, receiving feedback, and tweaking them Switching things up altogether - during the lab days we used storytelling, an important tool used in the Bhutanese culture, as a way of shaking up participant thinking before ideating together

FlexibleTimelines

Because the process leaned towards the emergent side, we did not know exactly how long it would take. As we moved through the process we learned quickly that culturally adapting and co-designing a process takes much more time than a conventional social innovation process. By creating space for our timelines and deadlines to be adjusted we enabled a more responsive and meaningful process. The bullets that follow highlight a few ofthe reasons things took longer:

Translating not just language but also cultural practices and approaches takes time especiallywhen much of it is implicit knowledge. Much time was spent explaining and learning from one another about different cultural practices and approaches to problem solving. Going back and forth between the stewardship team and community. There would be times when the community leaders on the stewardship team needed to return to the community to find out more information/ ask a question. This process of going back and forth took additional time. Thinking deeply about the approach and process each step along the way. There was a need to pause, reconsider, pivot, and adjust as things moved along. Non hierarchical, democratic and dialogue based approach to decision making led to long discussions and periods of contemplation before moving forward.

40

HIGHLIGHTS OF PARTICIPANT FEEDBACKON DESIGN BY DOING 2.0 PROCESS

The following chart highlights strengths and challenges encountered throughout the Design by Doing 2.0 process as articulated by community community. These insights were gathered through focus groups held with the stewardship team and Bhutanese community members as well as interviews with a sample of community partners.

Stakeholder

CommunityPartners

Involved in the lab days andthe development, refinement, and testing ofthe prototypes partners, the stewardship team, and members ofthe Bhutanese

Design by Doing 2.0 Process

Strengths Challenges

BroughtTogether Diverse

• Perspectives • Networking and learning from others communitywith professional/service

doing similarwork • Gained takeaways to apply to own work elsewhere

Built Empathy &Awareness

• Engaged directlywith the Bhutanese community - the community experiencing the challenge • Learning from the Bhutanese community about their culture and the challenges they face • Learned communities are falling through the cracks, their needs are not met by traditional services • Raised awareness about an issue they

BigTime Commitment

• 2 days was a large time commitment

Needed MoreTime

• Needed more time to prototype - takes time to bridge expert knowledges of didn’t know about before

knowledge • More time fo r sharebacks to large group during lab

41

Stakeholder

StewardshipTeam

Core lab team stewarding and involvedthroughoutthe entire process refinement, andtesting

Design by Doing 2.0 Process

Strengths

CulturalAdaptation

• Enabled by deep conversation and relationship building with community • Valuing of non dominant ways of knowing • Catering to nuances of a specific ethno cultural community enabled very specific and useful prototypes to emerge

CommunityCentred Process

• Anchored in relationship with the community • Entire process built around community needs and desires • Full participation ofthe community, space created forthem to lead and learn from the process • Learning about the community’s already established methods for problem solving

Shared Leadership

• Strength in having multiple partners at the table (Bhutanese community, MCHB,

EndPovertyEdmonton, City, and Action

Lab) - each brought different assets and perspective

Sharing ourStories and Experiences

So good to share ourexperiences in the learning stations Decorating the space and sharing ourfood share theirthoughts and ideas throughout the process Opportunityto share issues and needs with others Honorarium fortime

Solution Focussed Approach

Focus on outcomes was nice

BuildingCommunityC apacity

Participation in lab days resulted in new connections to resources and strengthened

Challenges

Communication Beyond the Stewardship Team

• Challenging to keep communitypartners involved/informed throughout the process without overburdening

Emergent Process

• Hard to plan when you’ve never participated in a socialinnovation process before • Ambiguous and emergent process required flexibility and adaptability

Translation

• Challenging to translate all aspects ofthe process (e.g. tools like EmpathyMap) • Tough forcommunity members to do ‘on

Bhutanese CommunityMembers

Involved in scoping the challenge area, participated in lab days, as well as prototype development,

Having our language present

Felt Heard and Respected

Felt heard and as though they had space to

the spot’ interpreting relationships

WesternWayofKnowingRemained Present

Some members felt their opinions were taken superficially or lightly Some felt the western wayofknowing took precedence at times (during prototyping especially)

Needed MoreTime

Things moved quickly during the lab days More time needed for prototyping, it felt rushed

More or Different Stakeholders

More Bhutanese community members Employers Government ofAlberta programs like Alberta Works

42

EMERGING TENSIONS

One Side oftheTension

Important to have the community’s voice present Recognizing the value in pushing for systems change newcomers into the future. authen tic engagement and collaboration with the extra time and continual reflection. As with any complex challenge, a number oftensions emerged as we moved through the process. The chart below provides an ‘at a glance’ look at three tensions that emerged in the Design by Doing 2.0 process. Navigating these tensions skillfullywas trickywork that took consistent reflection, flexibility, and adaptability. Recognizing that simplistic approaches and rigid strategies would not work for the complex tensions. What emerged was an approach that was culturally sensitive, collaborative, reflective of community gifts and talents, and responsive to community needs.

throughout the process.

so that things can change for

Co-design requires community. This requires challenge at hand, the stewardship team opted to embrace the following

Tension

Engagedvs Burdened

Changing systemsvs Change inthe here and now

Withvs For

Other Side oftheTension

People’s lives are busy and full. Community members are already engaging in a lot of ‘invisible labor’.

Community members face certain realities right now that they long to have support with (e.g. finding employment).

Because offiscal and time constraints it can be easy to fall back into patterns of inauthentic collaboration with community- doing for rather than with.

The Design Challenge (SoWhat?)

How do you foster authentic community engagement that isn’t burdensome?

How do you balance the need to push for systems change (slow but important work) and the need to create material change in the lives of the community members in the here and now? How do you design the process so the work is done with rather than for ethnocultural communities?

43

CONSIDERATIONS AND IDEAS FOR NEXT TIME

Keyconsiderations:

Planning and building in additional‘check in’ pointswith people participating in the process:

As the process unfolded it became challenging to reconnect with people who attended the lab days, updating them on how the project was moving ahead, and providing them with further opportunities to get involved. An idea for the future would be to have someone on the stewardship team in charge of delivering project updates via an electronic newsletter or in person announcements.

Planningforthe ending ofthe project and supporting prototypes in becoming pilots:

This challenge is not unique to this lab but one worth noting. As the project progressed it became blurrier and blurrier as to when a natural endpoint might come and who would be responsible for carrying prototypes forward. This is something we are still navigating as we work to find ‘homes’ for each ofthe prototypes - people or organizations who will continue to work on supporting the prototypes in becoming pilots.

Planning an ethicalexit:

Afterworking so closelywith a community for an extended period of time it is important to consider what the end ofthe relationship looks like. This is something we are still navigating as a group. One thing we did decide to do was host a community showcase. This afternoon event provided the stewardship team an opportunity to share key learnings from the project with community members. It also created space for the community members to ask questions about the process and outcomes and learn more about the prototypes.

44

CONSIDERATIONS AND IDEAS FOR NEXT TIME

Things thatworked reallywell and shouldn’t be forgotten:

Having a project manager/coordinator:

Hiring someone who could focus on keeping the project moving forward, booking meetings, and following up on loose ends so they aren’t forgotten was critical to the success ofthis project. For future projects, if it is feasible, it would be even better ifthere could be a prototype coach/coordinator for each prototype team to help guide them through the development, refinement, and testing process and keep things on track.

Compensation forcommunity members:

We had two community leaders from the Bhutanese community as part ofthe stewardship team. They and other community members who participated at various points throughout the process were financially compensated fortheir time. This was a critical component of engaging the community as equal partners.

Havingtranslators in each prototype team forthe lab day s:

We had bilingual members ofthe Bhutanese communitywork as translators in the working groups during the lab days. This was crucial in ensuring each step ofthe process was accessible and inclusive to everyone.

45

SO WHAT, NOW WHAT? IMPLICATIONS AND NEXT STEPS…

Project Outcomes

• Increased awareness about the Bhutanese community and their needs • A number of Bhutanese community members have found jobs through connections made in the process • Deepened understanding of approaches to problem solving with community rather than to community • New relationships leading to fruitful partnerships and collaborations into the future

Implications

• There is value in co-designing a process and prototypes directlywith a specific community (rather than focussing on newcomer communities for generally for example) • Design by Doing 2.0 is an example for others to use - Culturally adapted approach applicable to other ethno cultural communities • Prototypes hold promise for addressing barriers to employment experienced by the Bhutanese community in Edmonton as well as other multi barriered newcomer communities

Next Steps

• Prototypes, in theirvarious stages continue to be tested and developed • Seeking funding and a ‘home’ for each prototype - community members or organizations with the capacity to continue to support prototypes in becoming pilots • Share our learnings with others through presentations, conversations, and distributing the mini documentary on the process