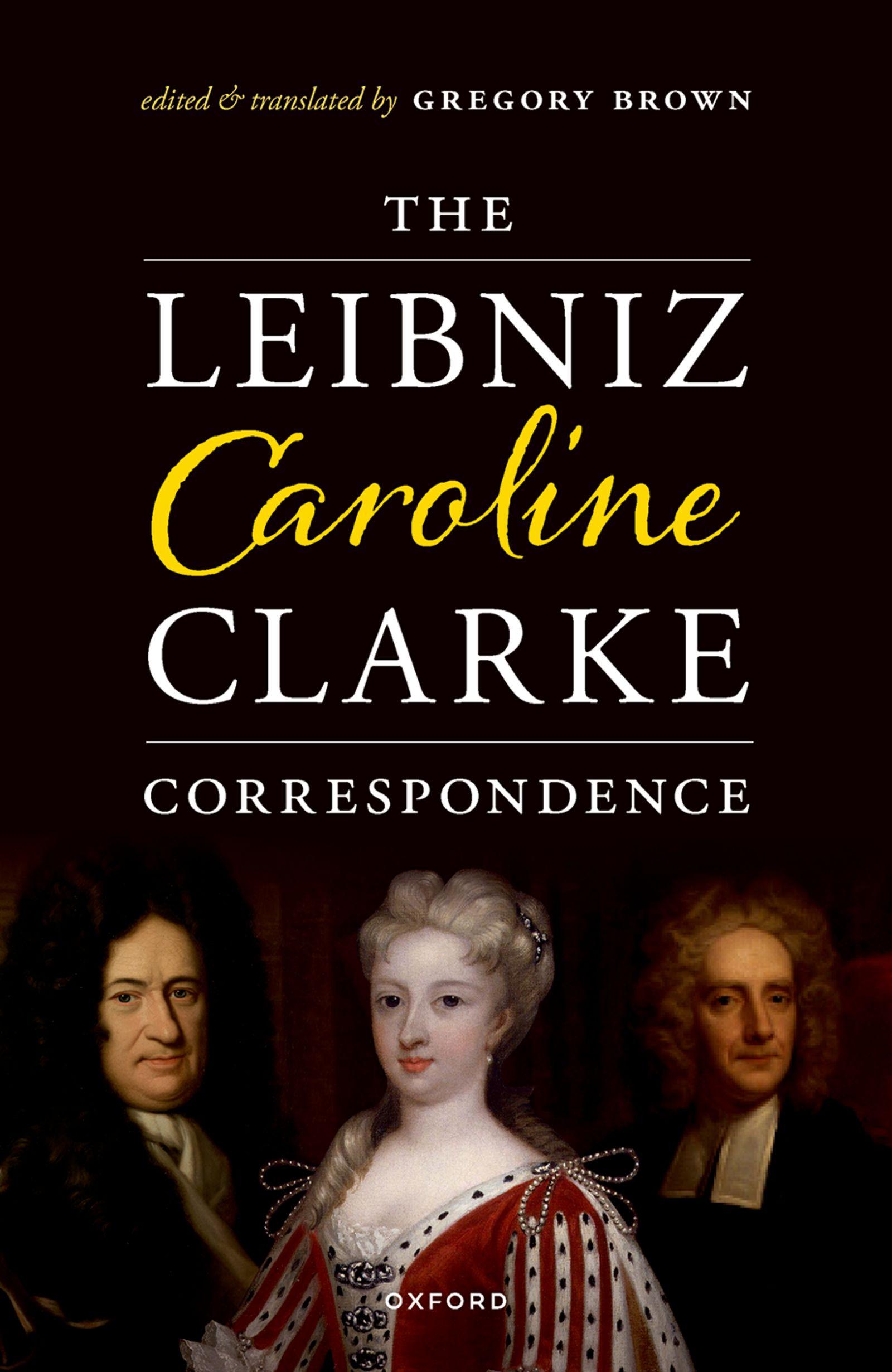

The Leibniz–Caroline–Clarke Correspondence

Edited and Translated by GREGORY BROWN

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Gregory Brown 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022950600

ISBN 978–0–19–287092–6

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

J’espère que S. A. R. ne nous aura point abandonnés entièrement pour les Anglois, ni voulu diminuer ses bontés pour nous par le partage. Comme le soleil ne luit pas moins à chacun, pour luire à plusieurs. V. E. qui nous appartient aura soin de nous à cet égard, et j’espère que vous voudrez, madame, me protéger en particulier contre les mauvais effets de l’absence, que je n’ai que trop de sujet de craindre.

—Leibniz’s letter to Johanne Sophie of 29 January 1715 (document 63)

Vous estes ferme et constante dans les choses grandes et importantes, mais je dois craindre, madame, que vous ne le soyez pas également dans les petites, comme doit être à votre garde tout ce qui a rapport à moi, et particulièrement la version de la Théodicée.

—Leibniz’s letter to Caroline of 28 April 1716 (document 113)

Mais d’où vient que vous me soupçonnez de n’être la même pour vous?

—Caroline’s letter to Leibniz of 5 May 1716 (document 115)

[. . .] V. A. Royale a paru un peu chancelante, non pas dans sa bonne volonté à mon égard, mais peut-être dans sa bonne opinion de moi et de mes opinions, surtout depuis qu’il semble que la version de la Théodicée demeure en arrière

—Leibniz’s letter to Caroline of 12 May 1716 (document 117a)

Vous me trouverez malgré vos soupçons toujours la même.

—Sign-off, Caroline’s letter to Leibniz of 15 May 1716 (document 119)

Je chercherai avec empressement les occasions à vous marquer que je suis toujours la même.

—Sign-off, Caroline’s letter to Leibniz of 26 June 1716 (document 128)

[. . .] et vous me trouverez toujours la même.

—Sign-off, Caroline’s letter to Leibniz of 6 October 1716 (document 151)

[. . .] et je serais toujours la même pour vous.

—Sign-off, Caroline’s letter to Leibniz of 29 October 1716 (document 156)

Vous me trouverez comme toujours la même personne qui vous estime infiniment.

—Sign-off, Caroline’s last letter to Leibniz, 4 November 1716 (document 158)

Hence these tears.

—A. Rupert Hall, Philosophers at War, p. 9

1. Essais de Théodicée sur la Bonté de Dieu, la Liberté de l’Homme et l’Origine du Mal: Discours de la Conformité de la Foy avec la Raison §§ 18–19 (1710)

2. Leibniz to Nicolaas Hartsoeker (10 February 1711)

Unpublished

Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff to Leibniz (3 March 1714)

John Chamberlayne to Leibniz (10 March 1714)

Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (21 March 1714)

7. Leibniz to John Chamberlayne (21 April 1714)

Leibniz to Sophie of the Palatinate, Dowager Electress of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (24 May 1714)

11. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Electoral Princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (24 May 1714)

12. Queen Anne to Sophie of the Palatinate, Dowager Electress of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (30 May 1714)

13. Queen Anne to Georg Ludwig, Elector of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (30 May 1714)

14. Queen Anne to Georg August, Electoral Prince of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (30 May 1714)

15. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Electoral Princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, to Leibniz (7 June 1714) 53

16. Johanne Sophie, Gräfin (Countess) zu Schaumburg-Lippe, to Baroness Mary Cowper (12 June 1714) 57

17. Benedictus Andreas Caspar de Nomis to Leibniz (13 June 1714) 61

18. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Electoral Princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (16 June 1714) 67

19. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Electoral Princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (7 July 1714) 73

20. John Chamberlayne to Leibniz (11 July 1714) 77

21. Johanne Sophie, Gräfin (Countess) zu Schaumburg-Lippe, to Louise, Raugravine Palatine (12 July 1714) 79

22. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Electoral Princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, to Baroness Mary Cowper (13 July 1714) 87

23a. John Chamberlayne to Leibniz (7 August 1714) 91

23b. Enclosure: Extract from the Journal of the Royal Society (20 May 1714) 91

23c. Enclosure: Copy of a letter from John Keill to John Chamberlayne (20 July 1714) 93

24. Benedictus Andreas Caspar de Nomis to Leibniz (19 August 1714) 93

25. Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (22 August 1714) 97

26. Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorff to Johann Caspar von Bothmer (4 September 1716) 99

27. Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorff to Friedrich Wilhelm von Görtz (4 September 1714) 99

28. Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorff to Leibniz (8 September 1714) 101

29. Leibniz to the Dowager Empress Wilhelmine Amalie of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (16 September 1714) 101

30. Leibniz to Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk (16 September 1714) 105

31. Leibniz to Georg August, Prince of Wales (17 September 1714) 107

32. Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (20 September 1714) 109

33. Leibniz to Ernst Friedrich von Windischgrätz (20 September 1714) 113

34. Leibniz to Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorff (20 September 1714) 119

35. Leibniz to Claude Alexandre de Bonneval (21 September 1714) 121

36. Leibniz to Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (30 September 1714)

37. Leibniz to Eléonore Desmiers d’Olbreuse, Dowager Duchess of Celle (3 October 1714) 127

38. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (3 October 1714) 129

39. Claude Alexandre de Bonneval to Leibniz (6 October 1714) 135

40. Leibniz to Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (7 October 1714) 139

41. Leibniz to Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (12 October 1714) 141

42. Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (14 October 1714) 143

43. Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg to Leibniz (15 October 1714) 147

44. Leibniz to Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk (16 October 1714) 147

45. Leibniz to Claude Alexandre de Bonneval (Beginning of November 1714) 151

46. Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff to Leibniz (1 November 1714) 163

47. Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff to Leibniz (24 November 1714) 165

48. Leibniz to Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg (3 December 1714) 167

49. Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (8 December 1714) 169

50. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (8 December 1714) 175

51. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (18 December 1714) 179

52. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (28 December 1714) 185

53. Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (28 December 1714) 187

54. Leibniz to Johanne Sophie, Gräfin (Countess) zu Schaumburg-Lippe (28 December 1714) 187

55. Leibniz to Friedrich Wilhelm von Görtz (28 December 1714) 189

56. Isaac Newton: An Account of the Book entitled Commercium Epistolicum Collinii & aliorum, De Analysi promota; published by order of the Royal-Society, in relation to the Dispute between Mr. Leibnitz and Dr. Keill, about the Right of Invention of the Method of Fluxions, by some call’d the Differential Method (February 1715) 195

57. Some Remarks by Leibniz on Roberval, Descartes, and Newton (1715?) 201

58. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (Beginning of January 1715) 201

59. Nicolas Rémond to Leibniz (9 January 1715) 205

60. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (16 January 1715) 207

61. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (27 January 1715) 207

62. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (29 January 1715) 209

63. Leibniz to Johanne Sophie, Gräfin (Countess) zu Schaumburg-Lippe (29 January 1715) 211

64. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (12 February 1715) 213

65. George Smalridge, Bishop of Bristol, to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (15 March 1715) 215

66. Leibniz to Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff (15 March 1715) 221

67a. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (29 March 1715) 225

67b. Enclosure: Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (29 March 1715) 227

68. Nicolas Rémond to Leibniz (1 April 1715) 231

69. Andreas Gottlieb von Bernstorff to Leibniz (5 April 1715) 231

70. Leibniz to Johann Bernoulli (9 April 1715) 233

71. Henriette Charlotte von Pöllnitz to Leibniz (c.10 May 1715) 235

72. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (10 May 1715) 237

73. Leibniz to Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk (28 June 1715) 243

74. Leibniz to Dowager Empress Wilhelmine Amalie of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (28 June 1715) 245

75. Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk to Leibniz (6 July 1715) 249

76. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (3 August 1715) 253

77. Leibniz to Louis Bourguet (5 August 1715) 255

78. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (13 September 1715) 265

79a. Nicolas Rémond to Leibniz (18 October 1715)

79b. Enclosure: Extracts from letters of Antonio Schinella Conti to Nicolas Rémond Concerning Newton (30 June, 12 July, and 30 August 1715)

79c. Enclosure: Antonio Schinella Conti to Leibniz (April 1715)

80. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (21 October 1715)

81. Leibniz to Johanne Sophie, Gräfin (Countess) zu Schaumburg-Lippe (21 October 1715)

82. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (not sent) (late October to mid-to-late December 1715)

83. Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk to Leibniz (13 November 1715)

84. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (14 November 1715)

85. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (Late November 1715)

86.

First Paper (Late November 1715)

87. Leibniz to Johann Bernoulli (December 1715)

88a. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (6 December 1715)

88b. Enclosure: Leibniz to Antonio Schinella Conti (6 December 1715)

88c. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (early December 1715)

89. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (6 December 1715)

90. First Reply of Samuel Clarke (c.6 December 1715)

91. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (Mid-to-late December 1715)

92. Leibniz’s Second Paper (Mid-to-late December 1715)

93. Leibniz to William Winde (23 December 1715)

94. Leibniz to Christian Wolff (23 December 1715)

95. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (10 January 1716)

96. Second Reply of Samuel Clarke (c.10 January 1716)

97. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (c.14 January 1714)

98. Leibniz to Louis Bourguet (24 February 1716)

99. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (25 February 1716)

100. Leibniz’s Third Paper (c.25 February 1716)

101a. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (c.8 March 1716)

101b. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (c.8 March 1716)

101c. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (c.8 March 1716)

101d. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (c.8 March 1716)

101e. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (c.8 March 1716

101f. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (c.8 March 1716)

101g. Isaac Newton to Antonio Schinella Conti (17 March 1716)

102. Nicolas Rémond to Leibniz (15 March 1716)

103.

Bourguet to Leibniz (16 March 1716)

104. Antonio Schinella Conti to Leibniz (26 March 1716)

105. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (27 March 1716)

106. Louis Bourguet to Leibniz (31 March 1716)

107. Leibniz to Louis Bourguet (3 April 1716)

108. Leibniz to Antonio Schinella Conti (9 April 1716)

109. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (9 April 1716)

110. Leibniz to Johann Bernoulli (13 April 1716)

111. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (14 April 1716)

112. Leibniz to Louis Bourguet (20 April 1716)

113. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (28 April 1716) 501

114. Leibniz to Johann Caspar von Bothmer (28 April 1716)

115. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (5 May 1716) 513

116. Johann Caspar von Bothmer to Leibniz (5 May 1716) 519

117a. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (12 May 1716) 521

117b. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (P.S.) (12 May 1716) 529

118. Louis Bourguet to Leibniz (15 May 1716)

119. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (15 May 1716)

120. Third Reply of Samuel Clarke (c.15 May 1716)

121. Johann Bernoulli to Leibniz (20 May 1716)

122. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (26 May 1716)

123. Johann Caspar von Bothmer to Leibniz (29 May 1716)

124. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (2 June 1716)

125a. Leibniz’s Fourth Paper (c.2 June 1716)

125b. Leibniz’s Proposed Additions to his Fourth Paper (c.2 June 1716) 573

126. Leibniz to John Arnold (5 June 1716) 577

127. Leibniz to Johann Bernoulli (7 June 1716)

128. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (26 June 1716) 583

129. Fourth Reply of Samuel Clarke (c.26 June 1716) 591

130. Leibniz to Henriette Charlotte von Pöllnitz (30 June 1716) 605

131. Leibniz to Louis Bourguet (2 July 1716)

132. Johann Caspar von Bothmer to Leibniz (10 July 1716) 609

133. Johann Bernoulli to Leibniz (14 July 1716) 611

134. Pierre Des Maizeaux to Philipp Heinrich Zollmann (14 July 1716) 613

135. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (31 July 1716) 613

136. Leibniz to Robert Erskine (Areskin) (3 August 1716) 623

137. Johann Caspar von Bothmer to Leibniz (11 August 1716) 625

138. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (15 August 1716) 627

139. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (18 August 1716) 629

140a. First Draft of Leibniz’s Fifth Paper (c.18 August 1716) 633

140b. Leibniz’s Fifth Paper (c.18 August 1716) 661

141. Leibniz to Pierre Des Maizeaux (21 August 1716) 715

142. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (1 September 1716) 719

143. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (8 September 1716) 725

144. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (11 September 1716) 727

145. Leibniz to Dowager Empress Wilhelmine Amalie of BraunschweigLüneburg (20 September 1716) 733

146. Leibniz to Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk (20 September 1716) 739

147. Leibniz to George Cheyne (25 September 1716) 739

148. Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk to Leibniz (30 September 1716) 741

149. Leibniz to Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales (End of September to mid-October 1716) 743

150. Nicolas Rémond to Leibniz (2 October 1716) 749

151. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (6 October 1716) 751

152. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (9 October 1716) 753

153. Leibniz to Nicolas Rémond (19 October 1716) 757

154. Leibniz to Johann Bernoulli (23 October 1716) 759

155. Johann Caspar von Bothmer to Leibniz (27 October 1716) 761

156. Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (29 October 1716) 763

157. Fifth Reply of Samuel Clarke (c. 29 October 1716) 763

158. Caroline of Ansbach, Princess of Wales, to Leibniz (4 November 1716) 801

159. Johann Bernoulli to Leibniz (11 November 1716) 803

160. Antonio Schinella Conti to Isaac Newton (10 December 1716) 805

161. A Note by Isaac Newton Concerning his Dispute with Leibniz (after 10 December 1716) 809

1717–1718

162. Dedication and Advertisement to the Reader, Clarke’s 1717 edition of the Correspondence (1717) 813

163. Clarke’s Appendix to his 1717 edition of the Correspondence (1717) 819

164. Isaac Newton to Pierre Des Maizeaux (c.August 1718) 835

165. Isaac Newton to Pierre Des Maizeaux (c.August 1718) 837

List of Abbreviations

A Leibniz, G. W. Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe. Edited by the Academy of Sciences of Berlin. Series I–VIII. Darmstadt, Leipzig, Berlin: 1923 ff. Cited by series, volume, and page.

AAK Briefe von Christian Wolff aus den Jahren 1719–1753. Ein Beitrag zur Geschicte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu St. Petersburg. Edited by Arist Aristovich Kunik (Ernst Eduard Kunik). St Petersburg: Eggers (and Leipzig: Leopold Voss) in Commission der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

AG G. W. Leibniz: Philosophical Essays. Edited and translated by R. Ariew and D. Garber. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989.

AT Oeuvres de Descartes. Edited by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery. 11 vols. Paris: Vrin, 1974–1989.

Bodemann-BR Der Briefwechsel des Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Hannover. Edited by Eduard Bodemann. Hanover, 1889. Reprint, Hildesheim: Olms, 1966.

Bodemann-HS Die Leibniz-Handschriften der Königlichen öffentlichen Bibliothek zu Hannover. Edited by Eduard Bodemann. Hanover and Leipzig, 1895. Reprint, Hildesheim: Olms, 1966.

CHH The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1690-1715. Edited by Eveline Cruickshanks, Stuart Handley, and David W. Hayton. 5 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Cited by volume and page.

Dutens Leibniz, G. W. Opera omini, nunc primum collecta, in classes distributa, praefationibus et indicibus exornata. Edited by Ludovici Dutens. 6 vols. Geneva: De Tournes, 1768; reprint Hildesheim Georg Olms, 1989. Cited by volume and page.

Erdmann Leibniz, G. W. Opera philosophica quae extant Latina Gallica Germanica omnia. Edited by J. E. Erdmann. Berlin, 1839–1840.

FC Oeuvres de Leibniz. Edited by Louis-Alexandre Foucher de Careil. 7 vols. Paris: Firmin Dido frères, fils et Cie, 1861–1875.

FXF Biographie Universelle, ou Dictionnaire Historique des Hommes qui se sont fait un Nom par leur Génie, leurs Talens, leurs Vertus, leurs Erreurs ou leurs Crimes. Tome Troisième. 13 vols. Edited by François-Xavier Feller and François Marie Pérennès. Paris: Gauthier Frères et Cie. Paris: Gauthier, 1833–1838. Cited by volume and page.

GB Der Briefwechsel von Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz mit Mathematikern. Edited by C. I. Gerhardt. Berlin: Mayer & Müller, 1899.

GLW Briefwechsel zwischen Leibniz und Christiaan Wolff. Edited by C. I. Gerhardt. Halle: H. W. Schmidt, 1860.

GM Leibnizens mathematische Schriften. Edited by C. I. Gerhardt. 7 vols. Berlin –Halle: A. Asher H. W. Schmidt, 1849–1863. Cited by volume and page.

GP Die philosophischen Schriften von Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. 7 vols. Berlin, 1875–1890. Cited by volume and page.

H Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man, and the Origin of Evil. Translated by E. M. Huggard. LaSalle, IL.: Open Court, 1985.

HALS Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies (Hertford, England).

HC The Encyclopædia Britannica. Edited by Hugh Chisholm. 11th edn. 28 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. Cited by volume and page.

HGA The Leibniz-Clarke Correspondence. Edited with introduction and notes by H. G. Alexander. New York: Manchester University Press, 1956.

JGHF Commercii epistolici typis nondum vulgati selecta specimina. Edited by Johann Georg Heinrich Feder. Hannover: Gebrüder Hahn, 1805.

JHC Journals of the House of Commons. Reprinted by order of the House of Commons, 1803. Cited by volume and page.

JK Neue Beiträge zum Briefwechsel zwischen D. E. Jablonsky und G. W. Leibniz Edited by J. Kvacala. Jurjew (Dorpat): C. Mattiesen, 1899.

Kemble State Papers and Correspondence Illustrative of the Social and Political State of Europe from the Revolution to the Accession of the House of Hanover. Edited by John M. Kemble. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1857.

Klopp Die Werke von Leibniz Erste Reihe. Historisch-politische und staatswissenschaftliche Schriften. Edited by Onno Klopp. 11 vols. Hannover, 1864–84. Reprint, New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1973.

L Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Philosophical papers and letters. Edited and translated by Leroy E. Loemker. 2nd edn. Dordrecht and Boston: Reidel, 1969.

LBr Leibniz-Briefwechsel. Hanover, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz BibliothekNiedersächsische Landesbibliothek.

LDB The Leibniz-Des Bosses Correspondence. Translated by Brandon Look and Donald Rutherford. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

LH Leibniz-Handshriften. Hanover, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz BibliothekNiedersächsische Landesbibliothek.

MJM G. W. Leibniz: Dissertation on Predestination and Grace. Translated and edited by Michael J. Murray. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

NC The Correspondence of Isaac Newton. 7 vols. Edited by H. W. Turnbull, J. F. Scott, A. Rupert Hall, and Laura Tilling New York: Cambridge University Press, 1959–1977.

OB Lahonton, Œuvres complètes. Edited by Réal Ouellet and Alaine Beaulieu. Montreal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1990.

Pertz Gesammelte Werke. Aus den Handschriften der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Hannover. Edited by Georg Heinrich Pertz. 4 vols. Hannover: Hahnschen HofBuchhandlung, 1843–1847. Reprint, Hilesheim: Georg Olms, 1966. Cited by volume and page.

R Leibniz Political Writings. Translated and edited by Patrick Riley. 2nd edn. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

RB G. W. Leibniz. New Essays on Human Understanding. Translated and edited by Peter Remnant and Jonathan Bennett. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

List of Abbreviations xxi

SHS Œuvres Complètes de Christiaan Huygens, published by La Société Hollandaise des Sciences. 22 vols. La Haye: Martinus Nijhoff, 1888–1950. Cited by volume and page.

SMJ The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 13 vols. Edited by Samuel Macauley Jackson, George William Gilmore, Clarence Augustine Beckwith, Henry King Carrol, James Francis Driscoll, James Frederic McCurdy, Henry Sylvester Nash, and Albert Henry Newman. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1908–1914.

Preface

The documents gathered in this volume cut a winding path through the tumultuous final thirty-three months of Leibniz’s life, from March 1714 to his death on 14 November 1716. The disputes with Newton and his followers over the discovery of the calculus and, later, over the issues in natural philosophy and theology that came to dominate Leibniz’s correspondence with Samuel Clarke*, certainly loom large in the story of these years. But as the title of this volume is intended to convey, the letters exchanged between Leibniz and Caroline* of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Electoral Princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and later Princess of Wales, also figure prominently in their telling, and I have included their complete extant correspondence from 1714 to 1716. These letters are of particular interest inasmuch as they provide valuable insights into how and why Leibniz’s correspondence with Clarke arose, and why it developed as it did, with Caroline in the role of influential go-between—whence the title, The Leibniz–Caroline–Clarke Correspondence. But there is more; for these letters provide a window into the evolving personal relationship between Leibniz and Caroline. Much of the early correspondence between them after Caroline’s arrival in England is filled with thoughtful and engaging exchanges about philosophy, literature, and politics, about people Caroline was meeting in England, about those known by Leibniz far and wide, about the new royal family in England, headed by George I (Georg Ludwig* of BraunschweigLüneburg), as well as gossip about affairs of state in both Great Britain and Europe at large. Beyond the interest they hold for Leibniz scholars in particular, many of these exchanges may also be of interest to historians of early eighteenth-century Great Britain and Europe, and especially to those interested in the period immediately preceding and following the Hanoverian succession to the throne of Great Britain. But even quite early on in their correspondence Leibniz seemed to sense a threat to his relationship with Caroline, and a worrisome paranoia began to creep into some of his letters to her, letters in which he expressed concerns about her continuing allegiance to him now that she had been installed in England amongst his rivals. As the correspondence progressed, Leibniz’s paranoia only deepened; but it was nevertheless prophetic of a tragic truth to come. For the letters exchanged between Leibniz and Caroline document the rather sad story of the slow but steady erosion of Caroline’s loyalty to Leibniz after she departed from Hanover on 12 October 1714 and landed in England at Margate in Kent on 22 October as the new Princess of Wales and future Queen of England. In 1727 the Scottish poet James Thomson penned A Poem Sacred to the Memory of Sir Isaac Newton, calling him ‘our philosophic sun’, and it was by force of the political and cultural mass of

this sun that Caroline was eventually, and inexorably, drawn into its orbit, and away from Leibniz.

As I have already intimated, not every word of the letters exchanged between Leibniz and Caroline recorded in this volume speaks directly to Leibniz’s correspondence with Clarke and his dispute with Newton; but even when the words tack wide of those topics, they are not, for all that, lacking in interest to Leibniz scholars and historians of the period. The same may be said of the letters that Leibniz exchanged with other correspondents during this final period of his life, many of which are also included in this volume. For while most of them touch more or less directly on the dispute with Newton and the correspondence with Clarke, I judged that all of them record something of philosophical or historical value and thus contribute something of interest to the final chapters of the fascinating and complex story of Leibniz’s life and career. The title of this volume should be understood in this light; and thus while the correspondence between Leibniz and Clarke, on the one hand, and that between Leibniz and Caroline, on the other, occupy centre stage in this project, they do not fall exclusively within its purview, a purview that encompasses a much broader perspective on the swirl of events that engulfed Leibniz during the last few months of his life.

All the documents gathered in this volume are arranged chronologically according to the dates on which they were either composed or transmitted. And so although Clarke published his edition of the correspondence between himself and Leibniz in 1717, I have arranged Clarke’s papers chronologically according to the dates of the letters by which they were transmitted by Princess Caroline to Leibniz; similarly, I have arranged Leibniz’s papers chronologically according to the dates of the letters by which he transmitted them to Caroline for delivery to Clarke. However, the Dedication and Advertisement to the Reader with which Clarke prefaced his edition of the correspondence, as well as the list of passages from Leibniz’s works that he appended to that edition, are here reproduced in the section for the year 1717. In order to give the reader some idea of the sweep of the documents included in this volume, I have summarized a few highlights below.

March to September 1714 (documents 4–36)

The documents from March to September 1714 (documents 4–36) are from the period leading up to the death of Queen Anne on 12 August 1714, the consequent ascension to the throne of Great Britain by Elector Georg Ludwig, Leibniz’s employer in Hanover, and Leibniz’s hurried, and harried, departure from the imperial court in Vienna, where he had also been employed as a member of the imperial aulic council*, and his arrival in Hanover on 14 September. There are revealing letters exchanged between Leibniz and John Chamberlayne* concerning the calculus priority dispute with Newton (documents 5, 7, 20, 23a) and between Chamberlayne and Newton on the same subject (documents 8 and 9).

The letters exchanged between Leibniz and Caroline prior to the death of Queen Anne are valuable for what they reveal about the electoral family’s anxiety during the so-called succession crisis (see Caroline’s distraught letter to Leibniz of 7 June (document 15)), precipitated by the letters that Queen Anne had written on 30 May to the Dowager Electress Sophie* of the Palatinate (document 12), to her son, the Elector and future King of England Georg Ludwig (document 13), and to the elector’s son, the Electoral Prince Georg August* (document 14). Among the other notable documents from this period is a poignant letter from Johanne Sophie*, Gräfin (Countess) zu Schaumburg-Lippe, of 12 July 1714 to Louise, Raugravine Palatine (document 21) recounting the collapse and death of the Dowager Electress Sophie, Leibniz’s close friend and patroness in Hanover. Sophie had fallen ill while strolling in the gardens of Herrenhausen* with Caroline and Johanne Sophie; Sophie died there, in their arms, on 8 June 1716, just a day after Caroline had written her distraught letter to Leibniz. Johanne Sophie had written a shorter account of the ordeal in a letter of 12 June 1714 to Lady Mary Cowper* (document 16), who would eventually become one of Caroline’s English ladies-in-waiting after her arrival in England as Princess of Wales some five months after Sophie’s death. Caroline also sent a short account of the event to Lady Cowper on 13 July 1714 (document 22). There is also a moving letter of 7 July 1714 that Leibniz wrote to Caroline after hearing of the Dowager Electress Sophie’s death (document 19). On 17 September Leibniz wrote a pleading letter of excuse (gout and plague) and pardon to the new Prince of Wales Georg August for not having returned to Hanover sooner, before the departure of the prince and his father the king (document 31; see also his letter to Minister Andreas Gottlieb Bernstorff* of 20 September (document 32), his letter to Minister Friedrich Wilhelm Görtz* of 28 December (document 55), and his letter to Caroline from the end of November 1715 (document 85)). On 20 September, three weeks before Caroline’s departure for England, Leibniz wrote to the President of the Imperial Aulic Council, Ernst Friedrich Windischgrätz (document 33): ‘I am preparing to go to England with Madame the Royal Princess, who has the kindness to desire it. I have reasons for not yet revealing any of it to others, but I think that it is my duty to inform Your Excellency of it in order that you may judge if I could be useful there for the service of the emperor.’ And on 21 September Leibniz wrote to the Imperial General Claude Alexandre de Bonneval* in Vienna: ‘If I were in a state to obey Her Royal Highness, I would go with her to England’ (document 35). In letters to Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg* over the next three weeks (documents 36, 40, 41), he suggested more definitely that he intended to go to England soon.

October 1714 to the Middle of November 1715 (documents 37–83)

The documents from October 1714 to the middle of November 1715 are from the period immediately preceding Caroline’s departure for England on 12 October

1714 and leading up to the beginning of Leibniz’s correspondence with Clarke. On 14 October 1714 Leibniz wrote to Minister Bernstorff (document 42) warning him of a rescript that was prepared by a minister of the King of Prussia to be sent to King George I of Great Britain suggesting that the Anglican religion, headed by George I, is different from the evangelical (Lutheran) religion of George I and the Hanoverian electorate. Leibniz suggested to Bernstorff that something should be said against the view that the king’s religion is different from that of Anglican religion of Great Britain (see also the P.S. to his letter to Bernstorff of 8 December (document 49)). This signaled the beginning of several attempts by Leibniz to reconcile the Reformed and Evangelical churches through the mediation of the Church of England, a scheme in which he would soon attempt to enlist Caroline’s support (documents 97, 111, 113, 117a, and 124). In the P.S. to the last of these documents, a letter of 2 June 1716, Leibniz, having been frustrated by the responses of Caroline (documents 115 and 122) and that of the king, which Caroline had reported to Leibniz in her letter of 26 May 1716 (document 122), finally gave up his attempt to reunite the Protestant churches, saying: ‘I have done my duty, and the conscience of each will determine his own’ (p. 561).

The documents from this period include an extraordinary and amusing letter from the beginning of November 1714 that Leibniz wrote to the Imperial General Claude Alexandre de Bonneval (document 45), answering the latter’s equally extraordinary and amusing letter of 6 October (document 39), in which Bonneval related that Prince Eugène* of Savoy had suggested that since Leibniz was not going to England he should come to Vienna, a bit of information that Leibniz did not fail to share with Caroline in his letter to her from around 8 December 1714 (document 50, see also his unsent and undated draft letter to Caroline from late October to mid-to-late December 1715 (document 82)); then Bonneval described how the prince guards the copy of the Principes de la nature et de la grâce, fondés en raison that Leibniz had prepared for him, and how the prince forces Bonneval to kiss it, but without allowing him to copy it. Bonneval presents a rather bawdy analogy to illustrate how Leibniz might recompense him by giving him an even more expansive summary of his system than the one he prepared for the prince. Among other things in his response, Leibniz writes that he could still go to England before the end of the year, expresses his approval of and expands upon Bonneval’s bawdy analogy, and implores Bonneval to apply himself to having Emperor Karl VI* issue a rescript to the Regency of Austria ordering them to grant Leibniz’s requests and to follow his directions in the matter of the proposed Imperial Society of Sciences*.1

1 As early as his letter of 20 September 1714 to Ernst Friedrich Windischgrätz (document 33, p. 113) and his letter of the same date to Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorff* (document 34, p. 119), Leibniz had expressed his intention and desire to return to Vienna. His reason for wanting to return to Vienna as soon as possible was to oversee the founding and administration of the proposed Imperial Society of Sciences*. In his letter to Bonneval of 21 September 1714 he also spoke of returning to Vienna, but mentioned being delayed in that by ‘certain occupations’, by which he meant his work on his history of the House of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, his so-called Annales imperii occidentis Brunsvicenses*

On 1 November 1714, Minister Bernstorff, having been informed that Leibniz was planning to leave for England, strongly advised him to remain in Hanover and to focus his attention on his history of the House of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, his so-called Annales imperii occidentis Brunsvicenses* (document 46) (see also the letter from Nicolas Rémond* to Leibniz of 9 January 1715 (document 59)). Leibniz subsequently wrote to Schulenburg on 3 December (document 48) to inform him that he had changed his mind about going to England because of ‘a touch of gout’ (see also his letter to Rémond of 27 January 1715 (document 61)). In his response to Bernstorff of 8 December 1714 (document 49), Leibniz informed the minister of his progress on his history and then broached a topic that would surface periodically in his correspondence until nearly the end of his life, namely his desire to be appointed historiographer of Great Britain (see his letter to Bernstorff of 15 March 1715 (document 66); his letter to Caroline from c.8 December 1714 (document 50), of 18 December 1714 (document 51), of 29 March 1715 (document 67a), of 10 May 1715 (document 72), of 21 October 1715 (document 80); Caroline’s letters to Leibniz of 28 December 1714 (document 52), of 16 January 1715 (document 60), of 13 September 1715 (document 78); the letters of 11 August 1716 and 27 October 1716 to Leibniz from Minister Johann Caspar Bothmer* (documents 137 and 155, respectively)). In the letter of 10 May 1715 (document 72) Leibniz revealed to Caroline for the first time his long struggle with Newton over the discovery of the calculus and suggested that if the king made him historiographer of Great Britain it would make him an equal of Newton and do honour to Hanover and Germany.

Leibniz’s letter to Johanne Sophie of 29 January 1715 (document 63) is remarkable for its rather panicked worry about Caroline’s loyalties drifting from him to the English, something he solicits the help of Johanne Sophie to prevent by appealing to her own Germanic loyalties. Leibniz’s worry on this head, which was eventually shown not to be unjustified, surfaced again in his letter to Caroline of 21 October 1715 (document 80), this time in connection with her not having found a translator for his Theodicy, but blaming his suspicions on the wavering loyalties of Antonio Schinella Conti*. It surfaced yet again in his letter to Caroline of 28 April 1716 (document 113), this time tied to her failure to respond to his letters soliciting her help in his project to reunite the Protestant churches, but hinting once more at her need to deliver on the proposed translation of the Theodicy in order to alleviate his worry.

(document 35, p. 121). Leibniz also expressed his intent and desire to return to Vienna as soon as his historical work was completed in letters to the Dowager Empress Wilhelmine Amalie* of 28 June 1715 (document 74, p. 245) and 20 September 1716 (document 145, p. 735) and to her first lady-in-waiting, Charlotte Elisabeth von Klenk*, also of 28 June 1715 (document 73, p. 243) and 20 September 1716 (document 146, p. 739). See also Klenk’s letters to Leibniz of 6 July 1715 (document 75, p. 249), of 13 November 1715 (document 83, p. 293), and of 30 September 1716 (document 148, p. 741). Some of these letters also concern Leibniz’s worry about the news he had received that his wages for his service as aulic councilor had been cancelled.

In a letter apparently lost, but written in the third week of March 1715, Caroline transmitted to Leibniz a letter of 15 March written to her by the Bishop of Bristol (document 65), George Smalridge. As part of a plan to produce an English translation of Leibniz’s Theodicy, Caroline had solicited his thoughts about a copy of the Theodicy that she had sent to him for evaluation. In his letter to Caroline of 29 March 1715 (document 67a), Leibniz acknowledged receipt of Smalridge’s letter and defended his work against Smalridge’s charge that the Theodicy was obscure, going so far as to enclose a separate paper of three folio pages (document 67b) in response to the objections that Smalridge had raised in his letter. Significantly, in the footnote to his letter to Caroline, Leibniz proposed Michel de la Roche* as a suitable translator for the Theodicy. Although aborted after Leibniz’s death on 14 November 1716, the Theodicy translation project was an ongoing topic in several of the letters exchanged between Leibniz and Caroline following Leibniz’s letter to Caroline of 29 March 1715 (see Leibniz’s letters to Caroline of 21 October 1715 (document 80), from the end of November 1715 (document 85), of 28 April 1716 (document 113), of 12 May 1716 (document 117a), of 2 June 1716 (document 124), of 31 July 1716 (document 135), of 18 August 1716 (document 139), of 11 September 1716 (document 144) and Caroline’s letters to Leibniz of 14 November 1715 (document 84), of 6 December 1715 (document 89), of 10 January 1716 (document 95), of 26 June 1716 (document 128), of 1 September 1716 (document 142); see also Leibniz’s letter to Rémond of 6 December 1715 (document 88a), the letter of Pierre Des Maizeaux* of 14 July 1716 to Philip Heinrich Zollman* (document 134), and Leibniz’s letter to Pierre Des Maizeaux of 21 August 1716 (document 141)).

Because of their philosophical significance I have included four letters from Leibniz to Louis Bourguet* (documents 77, 98, 112, and 131) and three letters from Bourguet to Leibniz (documents 103, 106, and 118). All but one of the letters in this group were written in 1716. That one letter was Leibniz’s letter to Bourguet of 5 August 1715 (document 77), which was written in response to a letter from Bourguet in which Bourguet had apparently expressed his shock at the derogative remarks that Roger Cotes* had made in the preface to the second edition of Newton’s Principia about those who, like Descartes* and Leibniz, rejected a nonmechanical, primitive force of gravity and instead explained the motion of the planets in terms of material vortices. Leibniz used the occasion to argue, not only against the notion of gravity that Cotes had defended in his preface, namely that it is essential to matter, but also against the void, which Leibniz argued the Newtonians had to accept because the mutual attraction of all the parts of matter could produce no change if there were a plenum. But beyond criticisms of the Newtonians and remarks about Clarke, the letters between Bourguet and Leibniz reproduced here involve two other significant discussions—one revolving around the generation of animals in light of the discoveries of the microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, and the other concerning whether the universe had a beginning in time, under either the hypothesis that the universe is always equally perfect or

the hypothesis that it always grows in perfection. This discussion, which also involves an interesting exchange on the nature of infinities and infinite series, has some relevance to the Leibniz-Clarke correspondence since the question of whether or not the world is eternal does come up there (see section 15 of their fourth papers and sections 55–63 and 73–75 of their fifth papers).

In her letter to Leibniz of 13 September 1715 (document 78), and despite her confession that she ‘did not like [John Locke’s] philosophy at all’ (p. 265), Caroline praised the civility and the arguments of both Locke and Edward Stillingfleet in their famous exchange on the subject of substance. In his response of 21 October 1715 (document 80), published here for the first time, Leibniz conceded that Locke put up a tolerably good defense against Stillingfleet, but then added that ‘Mr. Locke undermines the great truths of natural religion.’ He went on to say that he ‘had hoped that my Theodicy would be found a bit more sound in England, if one day it were read in English, and that it would furnish some better principles’ (document 80, p. 279), and he lamented the fact that Caroline had not yet found anyone suitable to translate it into English.

In a letter of 18 October 1715 (document 79a), Nicolas Rémond transmitted to Leibniz a letter that Antonio Schinella Conti (the Abbé Conti) had left with him for Leibniz before Conti departed Paris for England (document 79c), as well as ‘some articles extracted from his letters that concern Mr. Newton’ (for which, see document 79b).

End of November 1715 to 14 November 1716 (documents 84–159)

These documents cover the entire period of Leibniz’s correspondence with Clarke. One of the more important documents from this time period, and here published for the first time in its entirety, is the letter that Leibniz wrote to Caroline at the end of November 1715 (document 85), which includes the famous passage that initiated the correspondence with Clarke and which Clarke published as Leibniz’s first paper in his 1717 edition of the correspondence (document 86). As in his letter to Caroline of 21 October 1715 mentioned in the previous section, Leibniz accuses Locke of undermining natural religion, but here he also indicts English philosophy in general, saying that ‘natural religion itself declines precipitously there’ (document 85, p. 313), and singles out Newton by name for having contributed greatly to this decline. In a letter dated December 1715 (document 87), Leibniz notified Johann Bernoulli* that the Newtonians were now attacking his philosophy and proceeded with his own attack on Newton’s philosophy, in which he included some of the criticisms he had raised in his earlier letter to Caroline. He also mentioned the letter from Conti that Rémond had transmitted to him (document 79c) and stated that he was replying to it. His reply of 6 December 1715 (document 88b) included the important P.S. in which Leibniz begins with a brief defense against the charges made by Newton’s followers that he had plagiarized Newton’s calculus and