The Age of Interconnection

A Global History of the Second Half of the Twentieth

Century

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Jonathan Sperber 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022937044

ISBN 978–0–19–091895–8

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190918958.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Lakeside Book Company, United States of America

Contents

List of Figures vii

List of Tables ix

List of Maps xi Acknowledgments xiii

Introduction 1

Part 1: The Material World 9

Chapter 1 Nature 11

Chapter 2 Disease 41

Chapter 3 Technologies 82

Part 2: Interactions 127

Chapter 4 Markets 129

Chapter 5 Migrations 168

Chapter 6 The Powers 206

Part 3: Varieties of the Social 295

Chapter 7 Societies 297

Chapter 8 Labor 357

Chapter 9 Leisure 400

Chapter 10 Consumers 436

Part 4: Dreams and Nightmares 475

Chapter 11 Beliefs 477

Chapter 12 Mass Murder 530

Chapter 13 Utopias 572

Aftermath 626

Conclusions 641

Notes 655 Select Bibliography 737 Index 755

List of Figures

1.1

1.2

2.1 Spread of Malaria, Worldwide, in the Last Third of the Twentieth Century

2.2 Worldwide Cigarette Consumption in the Twentieth Century

2.3 Mortality Rate for Non-Infectious Diseases in the US, 1950–2000

2.4 Overweight and Obese Adults (Ages 20–74) in the US, 1960s–1990s

2.5

3.1

3.2

3.3 Passenger Kilometers Flown Yearly, Worldwide, 1950–2000

3.4 Global Average Crop Yields, 1961–2000

4.1 Growth of International Financial Transactions, 1973–1998

4.2 Foreign Investments, Worldwide, 1914–2000

4.3 Yearly Change in the Global Product, 1951–2001

5.1 Immigration to Three Major Trans-Pacifc Destinations, 1950–1999

5.2

5.3

7.2a

Fertility Rates Worldwide, 1950–2000

7.2b Life Expectancy at Birth, 1950–2000

7.3 Youth and Age in the World, 1950–2000

7.4 Women of Peak Reproductive Age (25–29) in the Labor Force, 1950–1990

7.5 Women College Graduates per 100 Men College Graduates, Age 25 and Older

7.6 Illegitimate Births in Five Countries, c. 1970 to c. 2010

8.1 Union Membership in Five Countries during the Twentieth Century 379

8.2 Strikes in Wealthier Countries during the Second Half of the Twentieth Century 384

8.3 Strikes in Poorer Countries, 1950s–1980s 385

9.1 International Tourist Arrivals, 1950–2015

10.1 Growth in Number of Air Passengers Worldwide, 1950–2000

10.2 Growth in Number of US Air Passengers, 1950–2000

11.1 The Fate of Progress in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century 490

C.1 The Exponential Function, y = ex

List of Tables

2.1 Global Obesity 2008: Percent Over-20 Population Obese 67

3.1 Crossing the Threshold of Automobilization, 1950–2000 92

9.1 Reaching 200–250 TV Sets per 1,000 Inhabitants 411

10.1 TVs and Telephones (in Millions) Worldwide, 1960–1990 460

13.1 The Economic Fate of Post-Communist Eastern Europe 623

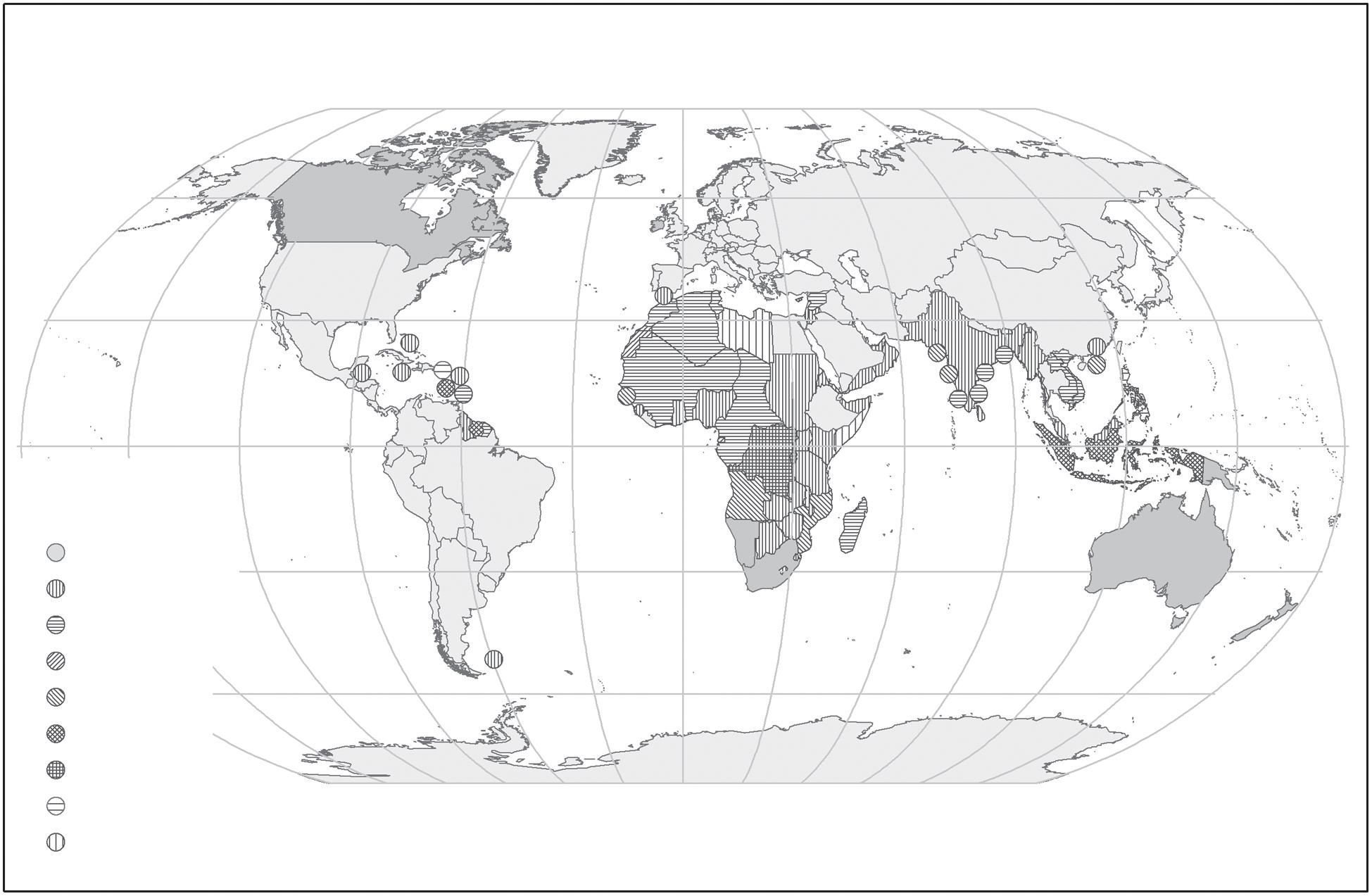

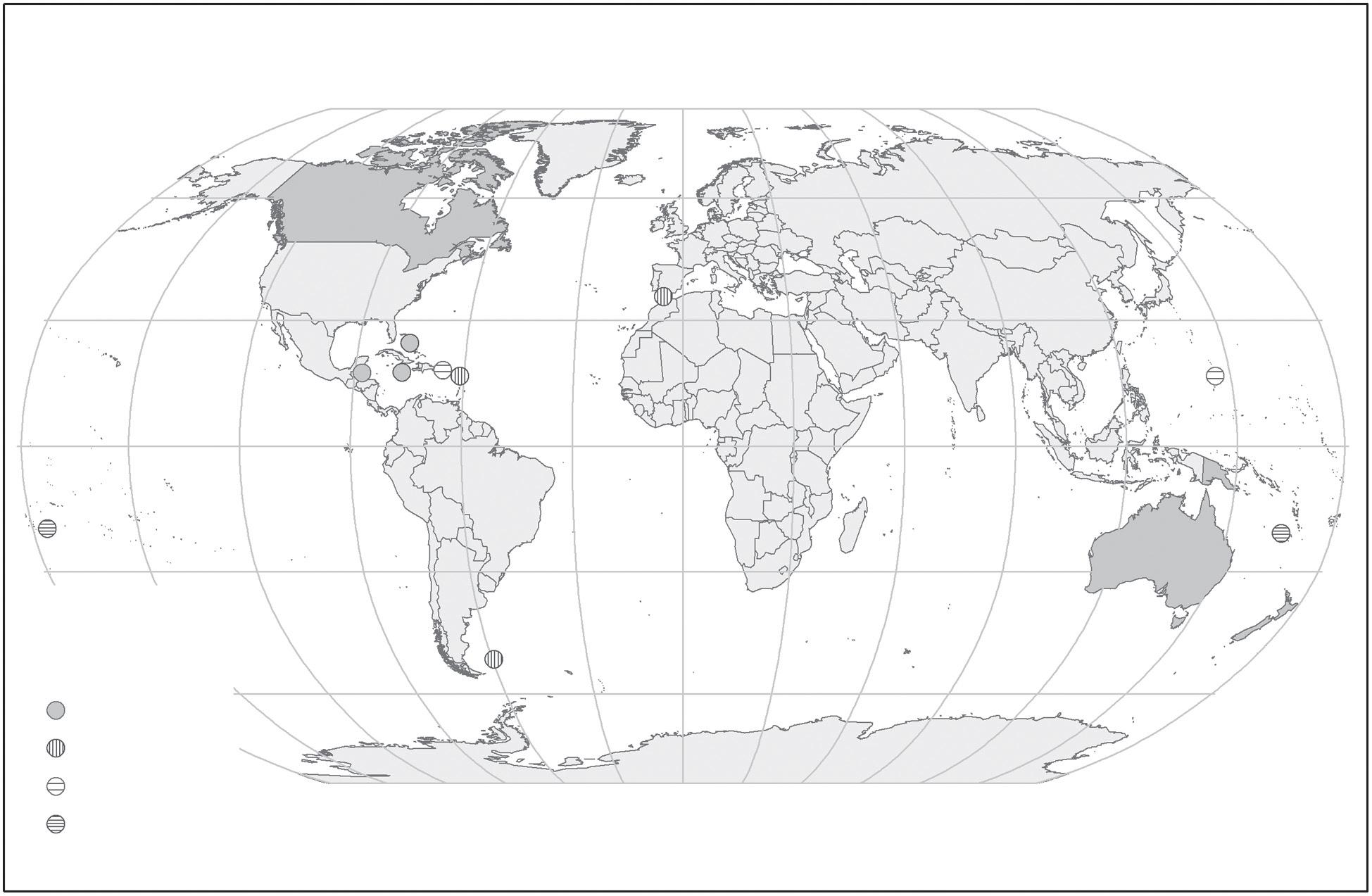

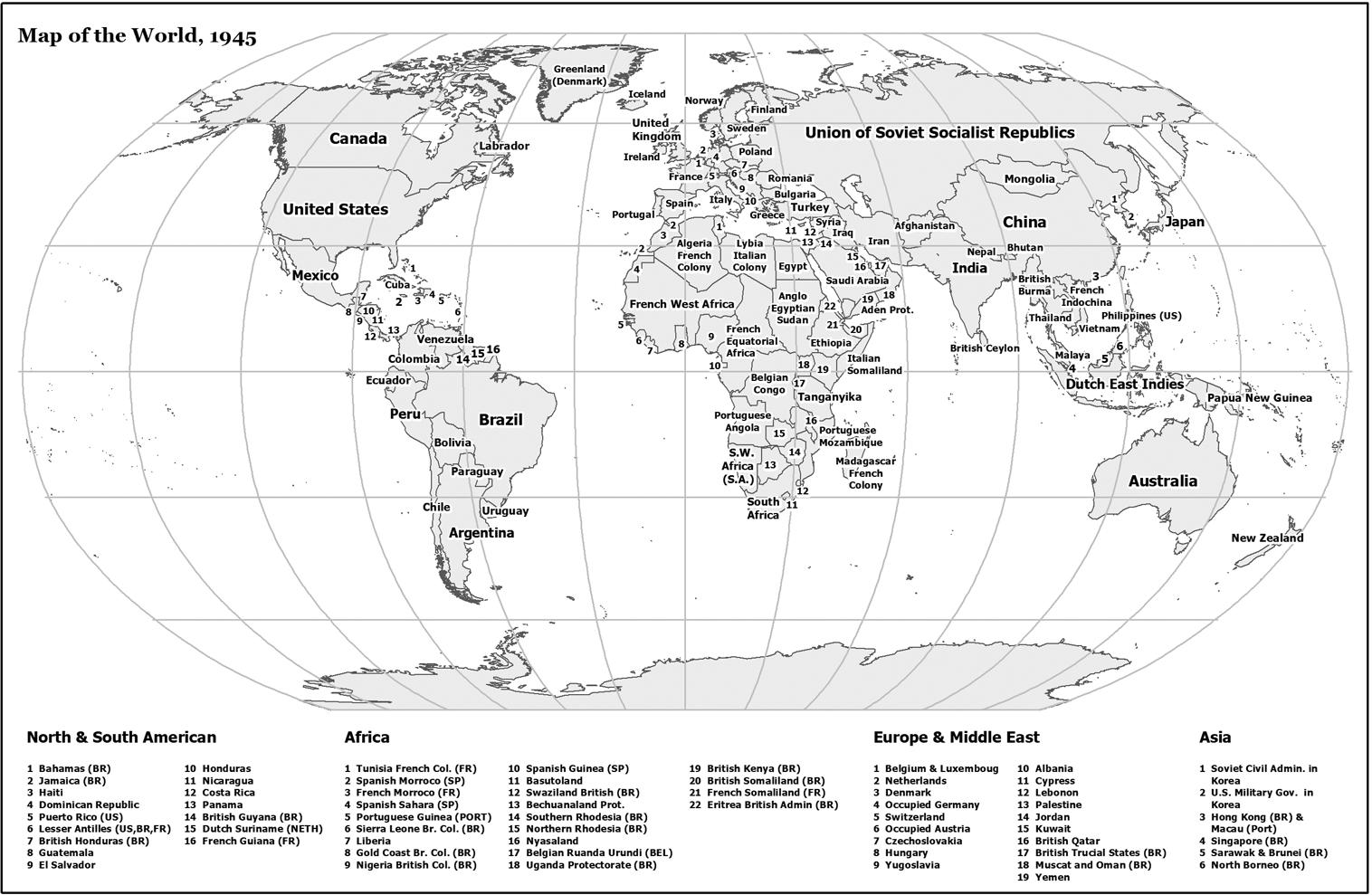

List of Maps

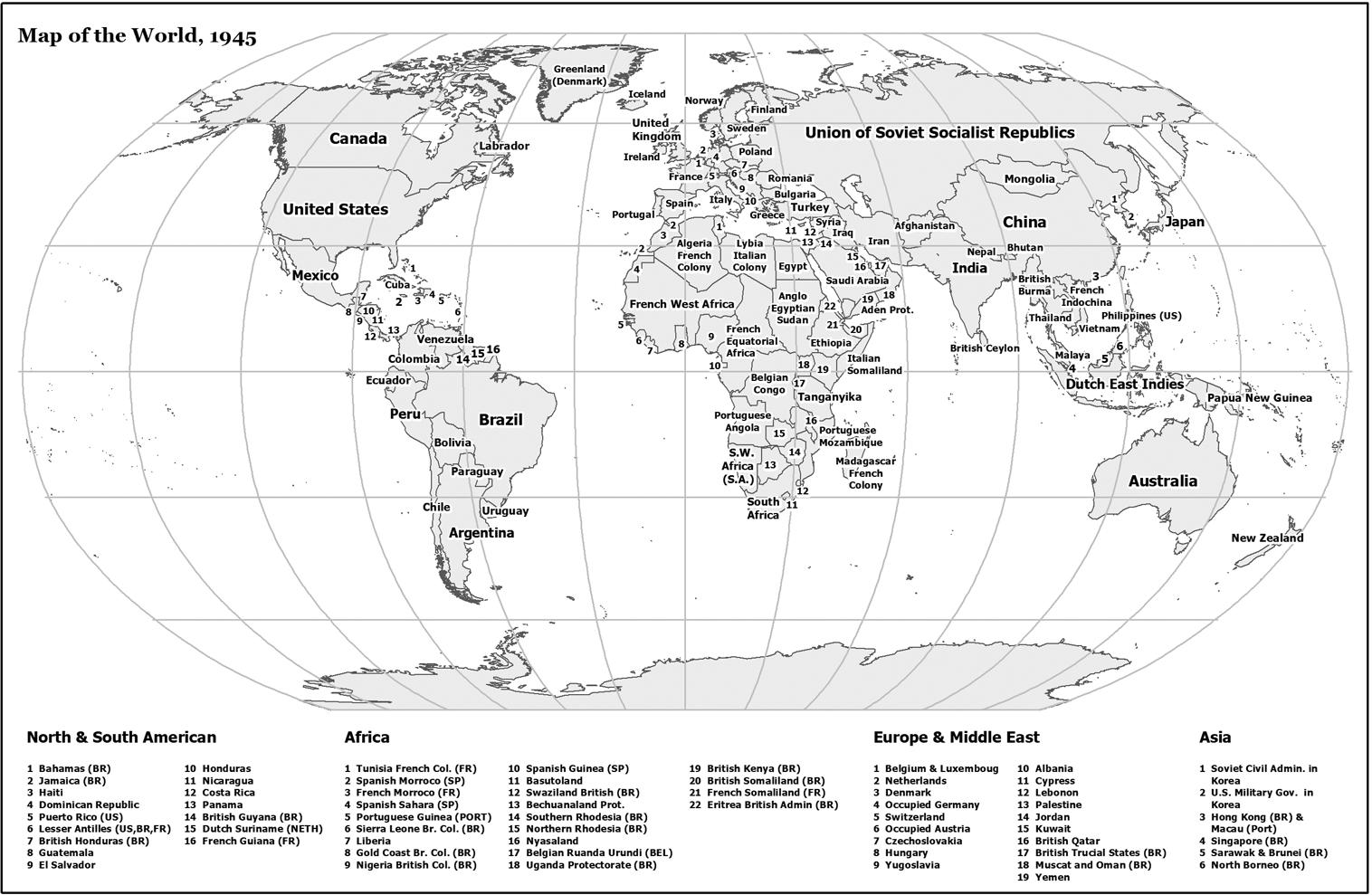

The World in 1945 xv

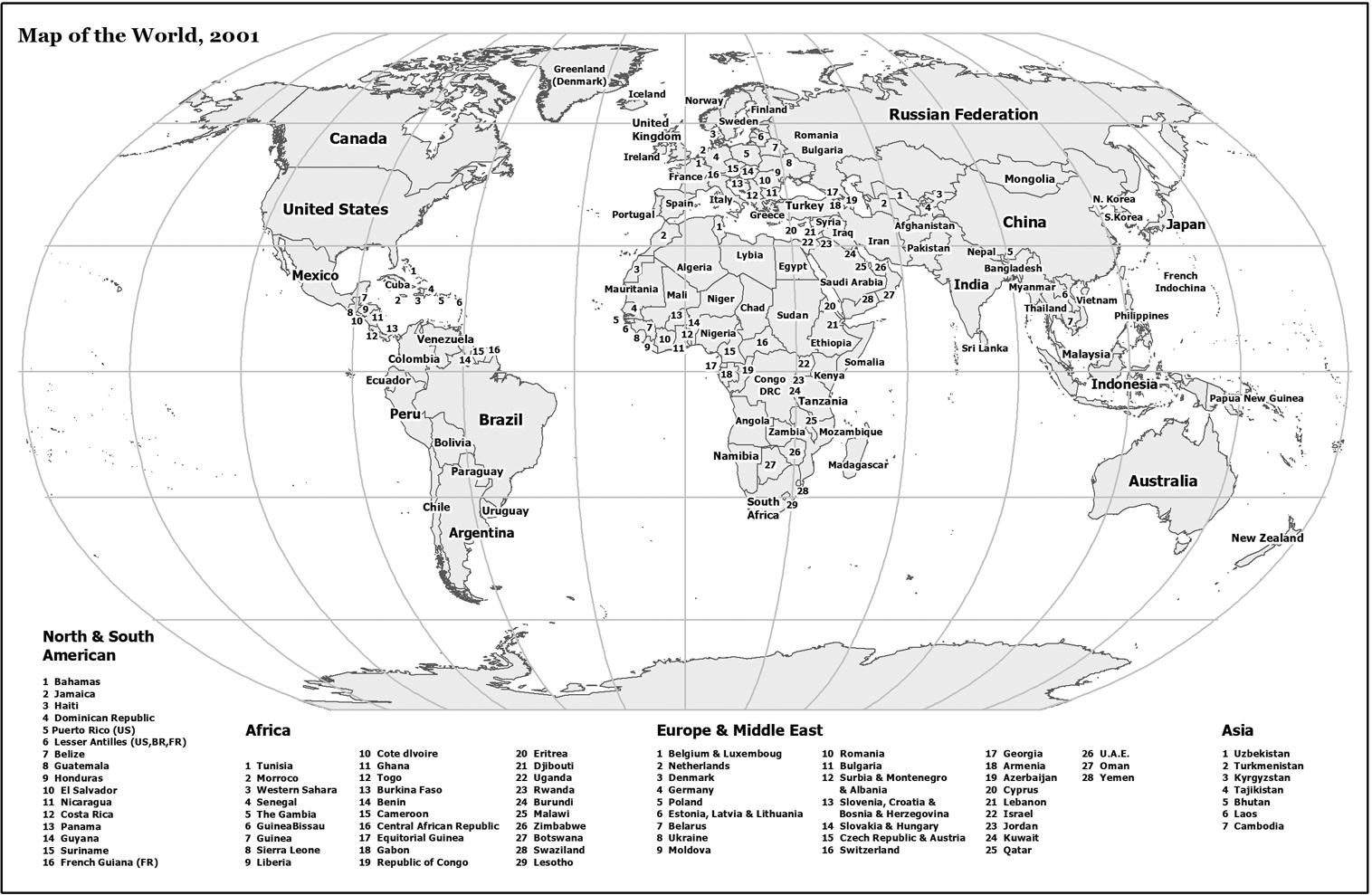

The World in 2001 xv

Colonial Empires in 1945 xvi

Colonial Empires in 2001 xvi

6.1 Countries under Communist Rule, 1945–2000 213

6.2 Germany, 1949–1990 230

6.3 Revolutionary Nonaligned Countries of the 1970s and 1980s 246

In the course of writing a very long book, I have received a lot of advice and encouragement. What follows is a small selection from a larger universe.

Material from this book was presented at the University of Chicago, Carnegie-Mellon University, and as the 2021 Gerald Feldman Memorial Lecture at the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC. Invitations for these opportunities were extended by Jan Goldstein, John Boyer, Donna Harsch, Simone Lässig, and Kenneth Ledford. My thanks to them and to the participants in the events for their many questions and observations. I am indebted to my colleagues in the department of history at the University of Missouri, who made unusually helpful suggestions, generously deployed their specialized knowledge, and saved me from evident blunders: Merve Fejzula, Gerrit Frank, Victor McFarland, Jay Sexton, Robert Smale, Steven Watts, and Dominic Meng-Hsuang Yang. I am particularly obligated to Catherine Rymph and John Wigger, who provided cogent criticisms of my approaches and fndings; read portions of the manuscript; and, above all, listened patiently as I rambled on about my overly ambitious aspirations. Any remaining mistakes are, of course, to be attributed to me and not to them. Tim Bent of Oxford University Press demonstrated his considerable editorial skills in his work on the manuscript I submitted. As this book was going to press I received the sad news of the death of my agent, John Wright. I remember him not just for his actions on behalf of his clients but also for his dedication to the literary genre of serious nonfction. The writing was completed in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, a particularly unpleasant example of an interconnected world. I dedicate this book to the healthcare personnel, scientists, and public health workers who have battled the pandemic, often against considerable resistance and in diffcult circumstances.

The World in 1945

The World in 2001

Colonial Empires in 1945

Colonial Empires in 2001

Introduction

Now, in the third decade of the twenty-frst century, it is time to perceive the years 1945–2001 as a period of human history separate and distinct from the present, in some ways rather distant from it, yet also at the origins of our contemporary condition. There is good reason to do so, since those ffty-fve years between the end of the Second World War and the onset of the new millennium were a period of varied, enormous, and farreaching transformations, from human relations with nature, to interactions of the Great Powers; from the structures of production and exchange of goods and services to the structures of religious faith. These were all changes that occurred on an increasingly global scale.

Overestimating the changes of the years between 1945 and 2001 would be diffcult. Emerging from the most destructive war in human history, the world experienced a quarter century of unparalleled economic growth, along with unprecedented growth in population and in human exploitation of the biosphere—only to be followed by a period of economic crisis and then unsettling global economic, demographic, and environmental realignments. The entire fve decades were an era of scientifc and technological advances, eliminating deadly diseases that had killed hundreds of millions of people, uncovering the secrets of life and of the origins of the universe, expanding agricultural productivity, computing power, and worldwide communications in ways previously unimagined and even unimaginable.

Most of the second half of the twentieth century was an age of global political confrontations, when humanity teetered on the brink of extinction in a thermonuclear confagration, while millions of combatants and civilians died in proxy conficts across the world, and millions more through mass murder. Colonial empires covering most of the globe were dismantled, in both peaceful and violent fashion. The centuries-old worldwide domination

of European countries and their former settler colonies was called into question. The all-encompassing combat that was the Cold War came to an unexpectedly peaceful end, as heavily policed authoritarian regimes suddenly collapsed before a handful of demonstrators. Hopes that the end of this global confrontation also marked the end of all major dissonances and political conficts around the world were disappointed, most dramatically in 2001, and more gradually over the following decades.

The question for a history of the second half of the twentieth century is how to understand the nature of these transformations and to offer a narrative of their development. One answer comes from journalists and pundits who overuse phrases like “globalization,” “the world is fat,” or the “singularity,” all implying unprecedented and worldwide changes. Their work tends to lack historical context, fattens out the past, and fails to make distinctions between the past—even the recent past—and the present. Historians, tracing change over time, attempt to provide a systematic account of the origins and shaping of the contemporary world, global in a double sense: worldwide and also encompassing central realms of human existence. Yet so much of global history focuses on a distant past. Responding to the contemporary realities of globalization with, for example, lovingly drawn portraits of the silk route, or of the crisis of twelfth-century monarchies, is to investigate a time when global connections were sparse, change slow and hesitant, opportunities for global comparisons few and far between, and links to the present hard to fnd.

Increasingly, historians have been studying the half century following the Second World War, particularly as these decades draw farther away from us, but have struggled to fnd a coherent framework. Overviews of the period often present a picture of one thing tumbling after another, unconnected. There were crises in Berlin, Cuba, Southeast Asia, Lebanon, Afghanistan. The Cold War arrived and then was over when a wall fell. Computers, lasers, genetic engineering, nuclear power, nuclear weapons, rockets, jet aircraft, the Internet—these are characterized as a jumble of science and technology. Women and minorities achieved greater equality and there were lots of protests and demonstrations. Former colonies became independent. The global economy changed—and it had to do with the European Union, oil price shocks, the International Monetary Fund, deregulation and privatization, cell phones, the rise of East Asia, and McDonald’s. This way of proceeding produces little better than a collection of old headlines and grand statements.

There are global histories that have offered more. A prime example is the account of the nineteenth century by the German historian Jürgen Osterhammel.1 His work, characterized by an analytical and thematic approach to the past, through which long-known events or prominent fgures reduced to cliches appear in a new and unfamiliar light, has been both a model and an inspiration. A central feature of his book is the representation

of the nineteenth century as distant and alien, while simultaneously tracing features within it that have led up to the present.

Applying this approach to the recent past requires an understanding of the second half of the twentieth century as involving two different versions of connection, geographic and temporal, or if one wants to be fancy about it, synchronic and diachronic. The frst, synchronic version concerns global connections: tracing the worldwide occurrence and global intertwining of political, diplomatic and military, economic, social and demographic, and intellectual, cultural, and artistic trends. The second half of the twentieth century is an extraordinarily rich period for this sort of investigation. Politics and diplomacy then played out in a global arena—and, at times, threatened to destroy the entire world. Humans have been transforming their natural environment since their days as hunter-gatherers, but from the 1950s onward environmental impacts moved steadily from locally to globally perceptible. Commerce and fnance were practiced on a global scale—not an entirely unprecedented development, but to an unprecedented extent. The globalization of industrial production, beginning in the 1970s, and gathering momentum ever since, was something quite new. Enhanced and accelerated global communications networks encouraged worldwide interconnections of political mass movements, scientifc and technological research, habits of consumption, popular culture, and religious practice.

In quite another respect, the years between 1945 and 2001 were an era of connection, temporally, or diachronically, between their predecessor, the Age of Total War, 1914–1945/50 and their successor, the initial decades of the twenty-frst century, our current condition. A history of the second half of the twentieth century requires portraying the shaping force of the age of total war on the decades after 1945—and not just in the immediate postwar era but extending down to the very end of the century. In some ways, as this book will show, the Second World War really only ended in 1990. It is not enough, though, to emphasize the shaping power of the age of total war, or even to observe that its shaping power began to wane by the fnal decades of the old millennium. A complete history of the years between 1945 and 2001 also needs to understand the emergence of political, social, economic, demographic, and cultural developments, particularly in the last third of the twentieth century, which moved in new directions, established new structures, broke with the past, and set the stage for today’s world.

Imagining the Era

To give meaning to the generalizations I have already made, consider the following features of the second half of the twentieth century, every one of which will appear in much greater detail in the course of this book:

1. The rate of global economic and population growth over the years 1950–73 was greater than at any previous time in human history— and at any subsequent time, as well.

2. In 1950, the United States was the only country in the world with at least 250 privately owned automobiles per thousand people, having just reached that point. By 2000, there were twenty-four countries worldwide at or above this level of automobile ownership, though none in Africa or Latin America, and just one in Asia. The United States had by then reached eight hundred automobiles per thousand inhabitants.

3. In the fve years after the end of the Second World War, one person in thirteen in the world was a refugee.

4. About one-tenth as many people were killed in wars of the second half of the twentieth century as during the two World Wars. Nonetheless from 1950 to 1989 the threat of a nuclear exchange that could wipe out all life on earth was a constant presence and on at least three separate occasions seemingly imminent.

5. The decolonization of Asia and Africa, occurring in three large bursts, the frst in 1945–1950, the second in 1960–1965, and the third in 1970–1975, saw the end of the largest colonial empires in human history.

6. While there were very widespread expectations that the onset of space travel would lead to a new stage of human existence, characterized by the colonization of the solar system, except for a few Apollo missions to the moon, human presence in space has been limited to low earth orbit. Robotic spacecraft, on the other hand, have explored the entire solar system, rolled around on the surface of Mars, and surrounded the earth with an impressive network of telecommunications and GPS location satellites.

7. As late as 1960, atmospheric CO2 levels were little above their preindustrial values, but by 2000 were more than 40 percent higher.

8. By 2000, there were more women university students than men in all parts of the world, except for African and Islamic countries. The latter were also the only places in the world where the birth rate was well above population-replacement levels.

9. In 1960, the vast majority of commercial passenger aircraft were propeller planes; by 1970, they were overwhelmingly jets.

10. The combination of the introduction of antibiotics, the widespread use of DDT, and the implementation of mass vaccination campaigns reduced infectious disease so drastically in the quarter century after 1945 that its eventual elimination seemed certain. But between 1980 and 2000 infectious disease made a comeback, and in certain instances—especially AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria in Africa—had

reached hitherto unknown levels. This was all before the COVID19 pandemic of the early 2020s, ongoing as this book was reaching completion.

11. In 1995, there were only sixteen million users of the Internet, less than one-half of 1 percent of the world’s population. Five years later, that fgure had soared to 361 million, a jump of over twenty-two-fold in half a decade, one of many examples of exponential growth rates in the second half of the twentieth century.

The question is how all these remarkable features of the years 1945–2001— birth rates, technology, gender equality—can be understood as part of a broader historical process, and not merely as a succession of disconnected headlines. In other words, how can the structures and trends behind the headlines, underlying the events, large and small, of the age be illuminated? The answer to this question comes in two parts: frst establish a chronology and second, set out broad elements of thematic development. Both appear in every chapter of the book.

To help with the chronology, the years 1945 to 2001 can be divided into three distinct and separate eras. The frst runs from the end of the Second World War and its immediate aftermath, 1945/50, until the mid1960s. In this Postwar Era, political conficts, leaders and aspirations, the interactions between the Great (and not so Great) Powers, social and demographic structures, crucial technologies, economic institutions and trends, even human relations with the biosphere, were all heavily infuenced by the preceding age of Total War, which extended from 1914 through 1945/ 50. There followed an Age of Upheaval in the 1960s and 1970s, when the structures and institutions of the postwar era were attacked, dissolved of their own accord, or suddenly and unexpectedly collapsed. During the third historical period, the last two decades of the millennium, the Late-Millennium Era, one might say, new structures and institutions, setting the stage for our current condition, made their appearance.

The second unifying idea of this work is that the second half of the twentieth century was, as the title of the book states, an age of interconnection, one in which economic, political, cultural, demographic, and informational relations spanned the world, integrating far-fung continents and countries of very different levels of economic development, social structures, and political systems. A crucial point is that the process of expanding interconnection was not uniform, linear, continuous, or unidirectional. Periods of rapid growth alternated with ones in which connections grew more slowly, or even declined. Advances of interconnection in one area of human existence might bring with them rejections of it in others: the globalization of manufacturing, the labor market, and communications in the last two decades of the twentieth century, for instance, resulted at least as much in

the growth of nationalism and religious intolerance, as they did of cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism.

In articulating these two structuring principles—dividing this half century into three distinct historical eras and the uneven rise of global interconnection—the book has a primarily thematic orientation. Each of its four parts approaches the years 1945 to 2001 from a different direction. In Part 1, “The Material World,” the emphasis is on the relationship of humanity to the physical and biological environment—human impact on the biosphere, the spread and decline of diseases (which is a form of human impact on the biosphere, taking place inside the human organism), or the ways science and technology changed human use of the physical world. Part 2, “Interactions,” follows the very uneven creation and development of global networks, and their consequences, from economic structures and economic growth, to relations between the Powers, great and small, to the paths people took in crossing borders, continents, and oceans. Part 3, “Varieties of the Social,” considers human interaction in a different vein, the many facets of society, from structures of class, gender, and generation, to labor relations, tourism, and consumerism, all portrayed in their development across fve decades, their forms of global interaction, and in their different expressions around the world. The fourth and fnal part of the book, “Dreams and Nightmares,” turns the focus to beliefs and aspirations, and their—often extreme—consequences, including the worldwide vicissitudes of the belief in God or of the belief in the idea of progress, the three waves of worldwide utopian aspirations, each connected to the upheavals of one of the fateful years of the era—1945, 1968, and 1989—or the repeated and varied instances of mass murder in the second half of the twentieth century.

Individual events and trends reappear in different ways across these four sections. To take an example of one of the better-known events of the era, at the time more than a little traumatic, the oil price shocks of the 1970s, the book’s frst section discusses their infuence on understandings of human relations to the natural world, as well as their role in promoting large-scale changes in automotive engineering. The same price shocks are investigated in the second section as part of a broader set of changes leading to a profound structural transformation of the global economy, playing a large role in the development of the Cold War and in the relations between the world’s wealthier and the world’s poorer countries, as well as redirecting global fows of migration. The price shocks and the infation and slowdown in economic growth they helped bring about affected both labor strife and consumer choice, topics of Part 3. The way rising oil prices reinforced, in both a material and spiritual sense, forms of integralist religion, in Christianity and Islam, are considered in the book’s fourth section. Repeatedly following this procedure, re-envisaging well-known (and more obscure) events in multiple contexts produces a multifaceted portrayal of a central era in recent history.

Writing history on a worldwide scale is always a challenge. No book can deal with every single issue and every single sovereign state. Information is not available to an equal extent for every continent—to say nothing of every country—and every writer, defnitely including myself, has specialized knowledge and limited linguistic abilities. If this book does not mention, or mentions insuffciently, any reader’s favorite country or particular interest, please accept my apologies in advance.

A combination of the availability of information and authors’ capability of accessing it all too often results in a “global history” comprised mainly of the North Atlantic world, North America, and Western Europe, sometimes also including a few other affuent lands, such as Japan and Australia. This global history often envisages developments occurring frst in wealthy countries, with the rest of the world engaged in “catch-up.” Though sometimes accurate, this approach is both fundamentally antithetical to an understanding of history as global process and increasingly inappropriate to comprehending the world of the late twentieth and early twenty-frst century, in which there has been a shift from the Atlantic to the Pacifc.

Attempting to cover the entire world across a period of over fve decades is ambitious chronologically as well as geographically. I have lived through most of the century’s second half, and on occasion add my own memories to the story, though I of course do not use my experiences as the sole basis for this book’s basic assertions. Those will stand on their own. Still, personal experience can sometimes be part of a broader process of bringing irony, humor, and human scale to a global story.

The Material World

Workers clear- cutting forests in Brazil, Indonesia, and Oregon; rapid population growth in Rwanda pushing farmers into cultivating ever-steeper slopes and more easily eroded soil; massive DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, a synthetic insecticide) applications in the United States, Italy, India, and Africa, killing the mosquitoes that carry malaria but also birds and fsh; the air irritating, choking, and even fatal for the ill, elderly, and newborn, from sulfur dioxide and particulates in London, ozone in Los Angeles or sulfur dioxide, particulates and ozone in Jakarta, Delhi, and Shanghai; volunteers in Santa Barbara and Brittany desperately trying to wash spilled oil from seabirds; the Aral Sea pumped dry to irrigate cotton crops in Soviet Central Asia; the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland catching fre; salmon and founder living in the Rhine River, for the frst time in decades; refneries producing gasoline without tetraethyl lead: all these scenes from the second half of the twentieth century testify to the most basic feature of those fve decades: human interaction with nature.

Of course, humans had been interacting with nature—procuring food and raw materials, depositing wastes, changing the landscape, transforming, reducing, or eradicating other species, serving as hosts to bacteria and viruses and facilitating their spread—since their days as Stone Age hunters and gatherers. There had been phases of acceleration and intensifcation of interactions, such as the invention of agriculture in the “Neolithic Revolution,” some twelve thousand years ago. In more recent centuries, the beginnings of more rapid global population growth around 1700; the largescale burning of coal with the onset of the Industrial Revolution during the frst half of the nineteenth century; and the development and increasingly widespread manufacture of artifcial fertilizers, synthetics, and petroleum products, as well as the large-scale generation of electricity, in the Second

Industrial Revolution beginning c. 1890, marked important waypoints in human relations with the biosphere.

But the second half of the twentieth century was an era of a new quality of human infuence on the natural world, stimulating a new level of awareness of that infuence and its consequences for humanity, as well as for all other species residing on the earth, and, in view of these consequences, quite unprecedented and steadily more controversial efforts to limit, regulate, and direct that infuence. At the beginning of the new millennium, Paul Crutzen, a Nobel Prize-winning chemist, gave all these changes a name— the “anthropocene,” suggesting a new era, in which human population and human economic and technological activity had become the dominant force shaping the global environment.1

Sometimes, the increase in the intensity of the interaction of humanity with nature appears as a straight linear pattern, a steady increase from 1945 to 2000. But breaking down this interaction, by considering its regional modalities across the globe; the similarities and differences with past historical eras; the effects of economic, demographic, and technological change; or efforts to respond to the interaction, at local, regional, national, and international levels, reveal a more complex picture. A postwar era in which taking the natural environment for granted was the norm gave way to a period of rethinking and actual changes during the Age of Upheaval in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by the Late Millennium Era in which new relations between humanity and nature formed—relations whose consequences often defed appropriate responses.

Taking Nature for Granted in the Postwar World

In the quarter century following the Second World War, human relations with the biosphere followed a pattern set in the frst half of the twentieth century—perceiving the natural environment as an adaptable and inexhaustible resource, to be exploited and managed. Electric power and home heating (in colder climates), came from burning coal, with the resulting train of particulates and sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere. Automobiles added lead and nitrogen oxides, the latter broken down into ozone. Farmers, carrying out both large-scale, mechanized agriculture and smaller-scale cultivation, with human and occasional animal power, acted as if soil reserves were unlimited, in spite of paying occasional lip service to conservation measures, such as contour plowing. At least in the regions of mechanized agriculture, farmers also added steadily larger amounts of nitrates to the soil.

What was true of farming extended to other forms of exploitation. Fishermen and whalers harvested as though the sea’s living resources were

without end. Industrial wastes, including mercury and heavy metals, were dumped into streams and rivers or emitted into the atmosphere; industrial workers had little if any protection from toxic chemicals in the workplace, such as lead or vinyl chlorides. Large-scale construction projects, for instance, the channeling and canalization of France’s Rhône River, in order to generate hydroelectric power, were carried out in an impressively rapid and dynamic fashion, but without any particular consideration of the effects of this hydraulic engineering on the inhabitants of riverside villages, to say nothing of fsh and wildlife.2

In this treatment of natural surroundings, there were some distinctly new elements, products of the technological changes stemming from the Second World War. One example was the introduction of radioactivity into the environment as the result of nuclear chain reactions. Later in the century, the consequences of using nuclear power to generate electricity would stand at the center of environmental interest, but until the 1970s there were virtually no atomic power plants. Rather, it was nuclear warfare, more precisely, the preparation for it, that was the major environmental consequence of atomic fssion. Building nuclear weapons was environmentally toxic. At the two major sites of the production of weaponized plutonium, Maiak, near Ozersk, in the Russian Urals; and Hanford, near Richland in Washington State, administrators and site workers demonstrated a distinctly cavalier attitude toward massively radioactive substances. No sooner had the Ozersk plant started production in 1948 than plutonium was bubbling through its ventilation system. Spills of radioactive substances occurred everywhere, and workers generally ignored the (few and totally unenforced) safety guidelines. Between 1949 and 1951, 7.8 million cubic yards of toxic and radioactive chemicals were dumped into the Techa River on the eastern fank of the Urals. At the end of that two-year period, Soviet scientists found villagers in the vicinity were receiving a lifetime’s dose of radiation in a mere week. The unsuspecting villagers were hustled away without warning, while all their possessions were burned and their livestock shot. The culmination of lax practices toward radioactivity came in 1957, when an underground storage tank holding radioactive waste exploded, blowing its 160-ton cement cap into the air, producing a cloud of radioactive gas a half mile high, and showering the vicinity with radioactive particles.

While there was nothing quite so extreme in Hanford, millions of gallons of radioactive waste were dumped in the Columbia River and buried in the vicinity; construction workers who were not plant employees were never monitored for exposure. Since the end of the Cold War, the problems facing the site’s decontamination—seventeen hundred pounds of plutonium-239 amid ffty-three million gallons of waste being just one small part—have proven well-nigh unresolvable. Nobody is even attempting to resolve the much-larger issues of radioactive pollution in Ozersk.3