Vengeance Is Mine

The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath

RICHARD

E. TURLEY JR . AND

BARBARA JONES BROWN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Turley, Richard E., Jr., author, Jones, Barbara Brown

Title: Vengeance is mine : the Mountain Meadows Massacre and its aftermath / Richard E. Turley Jr., Barbara Jones Brown

Other titles: Mountain Meadows Massacre and its aftermath

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2023004613 (print) | LCCN 2023004614 (ebook) | ISBN 9780195397857 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197675694 (epub) | ISBN 9780197675731

Subjects: LCSH: Mountain Meadows Massacre, Utah, 1857. | Massacres—Utah. | Murder—Investigation—Utah. | Mormons—Utah—History—19th century. | Lee, John D. (John Doyle), 1812–1877—Trials, litigation, etc.

Classification: LCC F826 .T87 2023 (print) | LCC F826 (ebook) | DDC 979 .2/02—dc23/eng/20230131

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023004613

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023004614

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780195397857.001.0001

To Juanita Brooks

Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.

Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.

Romans 12:19, 21

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

PART 1 CRIME

1. The Angel of Peace Should Extend His Wings: Salt Lake City and Mountain Meadows, September 11, 1857

2. Sermons Like Pitch Forks: New York to Utah, 1830‒57

3. Imposed Upon No More: Arkansas to Utah, January‒September 1857

4. Too Late: Mountain Meadows to Cedar City, September 12‒13, 1857

PART 2 COVER-UP

5. Forget Everything: Southern Utah, Mid-September 1857

6. The Sound of War: Salt Lake City to Beyond the Muddy River, September‒October 1857

7. An Awful Tale of Blood: Northern Utah and Southern California, September‒October 1857

8. Hostile to All Strangers: Eastern Utah to Eastern California, September‒October 1857

9. The Spirit of the Times: Southern Utah to Southern California, October‒November 1857

PART 3 NEGOTIATION

10. A Lion in the Path: Utah; Washington, DC; Arkansas; and Pennsylvania, November 1857‒January 1858

11. The Mormon Game: Northern and Eastern Utah, November 1857‒January 1858

12. Fearful Calamities: Arkansas, Oregon, Utah, and Washington, DC, January‒February 1858

13. Peacefully Submitting: Salt Lake, Camp Scott, and Spanish Fork, March‒May 1858

14. The Moment Is Critical: Salt Lake, Camp Scott, and Provo, May‒June 1858

PART 4 INVESTIGATION

15. Make All Inquiry: Provo and Salt Lake, June 1858

16. Join the Know Nothings: Northern and Southern Utah, June‒July 1858

17. A Line of Policy: Southern Utah, Arkansas, and Washington, DC, July‒December 1858

18. An Inquisition: Southern Utah, August 1858

19. Bring to Light the Perpetrators: Northern Utah, November 1858‒March 1859

20. Nothing but Evasive Replies: Northern Utah, March‒April 1859

21. Diligent Inquiry: Southern Utah, March‒April 1859

22. Approach of the Troops: Santa Clara to Nephi, Spring 1859

23. Catching Is Before Hanging: Santa Clara, May 1859

24. Precious Legacies from the Departed Ones: Northern Utah to Northwest Arkansas, May‒October 1859

25. Unwilling to Rest Under the Stigma: East Coast and Utah, May‒August 1859

26. The Course Adopted Will Not Prove Successful: Utah; Washington, DC; Arkansas, June‒August 1859

PART 5 INTERLUDE

27. Vengeance Is Mine: Southern States and Utah, 1860‒62

28. In the Midst of a Desolating War: Western United States and Washington, DC, 1862‒65

29. Too Horrible to Contemplate: Utah, 1865‒70

30. Cut Off: Utah and Nevada, 1870‒71

31. Boiling Conditions: Utah and Arizona, 1871

32. Zeal O’erleaped Itself: Utah, Arizona, and Washington, DC, 1871‒72

PART 6 PROSECUTION

33. The Time Has Come: Utah, Arizona, and Washington, DC, 1872‒74

34. Do You Plead Guilty: Utah, 1874‒75

35. Open the Ball: Utah 1875

36. A Means of Escape: Beaver, July 14‒19, 1875

37. Hope for a Hung Jury: Beaver, July 20‒28, 1875

38. The Curtain Has Fallen: Beaver, July 29‒August 7, 1875

39. Coerce Me to Make a Statement: Salt Lake and Washington, DC, August 1875‒April 1876

40. Mr. Howard Gives Promise: Utah, May‒September 1876

41. The Responsibility Before You: Beaver, September 14‒15, 1876

42. Sufficient to Warrant a Verdict: Beaver, September 15‒20, 1876

PART 7 PUNISHMENT

43. The Demands of Justice: Utah, September‒December 1876

44. Allow the Law to Take Its Course: Utah, January‒March 1877

45. Under Sentence of Death: Beaver to Mountain Meadows, March 20‒23, 1877

46. Failure to Arrest These Men: United States, Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

47. Haunted: Western United States and Northern Mexico, Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Notes

Index

Illustrations

1.1. 1.2.

2.1.

23.1.

27.1.

27.2.

29.1.

30.1.

30.2.

32.1.

33.1.

33.2.

33.3.

33.4.

33.5.

33.6.

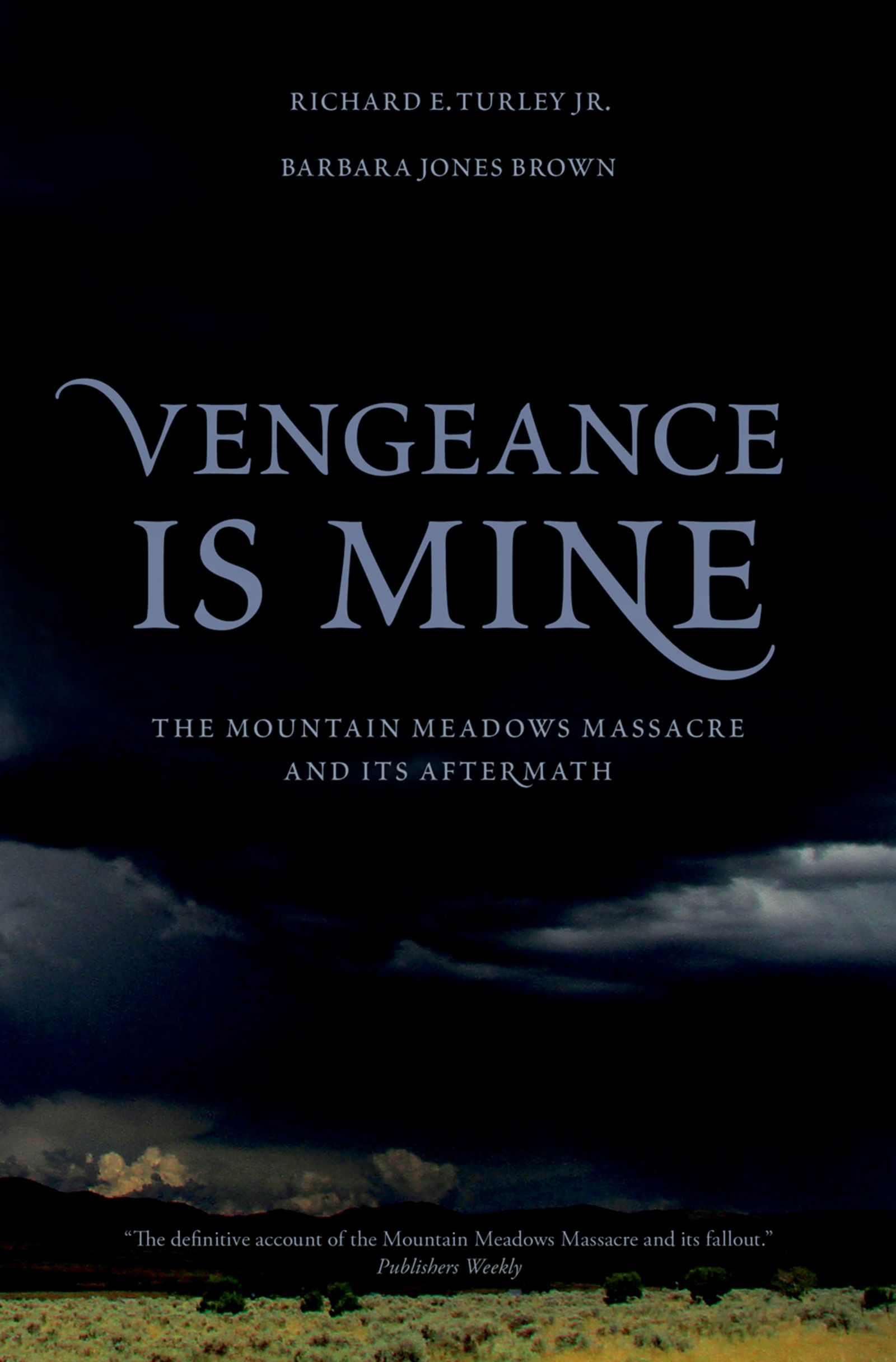

Left to right: Brigham Young’s Lion House, church president’s office, governor’s office, and Beehive House. Courtesy Church History Library.

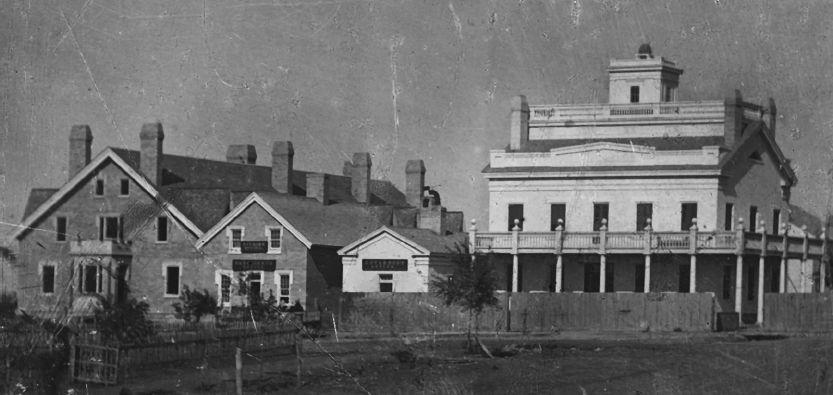

Brigham Young, 1855. Courtesy Church History Library.

Latter-day Saints baptizing Paiutes in southern Utah, 1875. Courtesy Church History Library.

John D. Lee with wives Rachel and Sarah Caroline. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Samuel Clemens. Courtesy University of Nevada, Reno, Special Collections.

The five fingers of Kolob rise above ruins of old Fort Harmony. Wally Barrus, Courtesy Church History Library.

George A. Smith. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Paiute leader Tau-gu (Coal Creek John) and John Wesley Powell. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Men of second Powell expedition. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

John D. Lee family members at home at Jacob’s Pools. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

George W. Adair. Public Domain.

William H. Dame. Public Domain.

Isaac C. Haight. Public Domain.

John M. Higbee. Public Domain.

Samuel Jewkes. Public Domain.

Philip Klingensmith. Public Domain.

33.7.

33.8.

33.9.

37.1.

John D. Lee. Courtesy Sherratt Library, Special Collections, Southern Utah University and Jay Burrup.

William C. Stewart. Courtesy FamilySearch.

Ellott Willden. Courtesy Jay Burrup.

John D. Lee, his legal team, and the judge: Left to right: (seated) William W. Bishop, John D. Lee, and unidentified man; (standing) Jacob Boreman, Enos Hoge, and Wells Spicer. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

45.1.

John D. Lee’s execution. Lee is seated on his coffin left, surrounded by reporters and government officials. To the right are the wagons from which the executioners fired. Courtesy Church History Library.

46.1.

46.2.

46.3.

46.4.

46.5.

47.1.

47.2.

Brigham Young late in life. Courtesy Church History Library.

Kit Carson Fancher. Public Domain.

Sarah Baker Mitchell. Public Domain.

Elizabeth Baker Terry. Public Domain.

Nancy Saphrona Huff Cates. Public Domain.

Nephi Johnson. Courtesy Church History Library.

Juanita Leavitt Brooks. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Preface

On September 11, 1857, a group of Mormon settlers in southwestern Utah used false promises of protection to coax a party of Californiabound emigrants from their encircled wagons and massacre them. The slaughter left the corpses of more than one hundred men, women, and children strewn across a highland valley called the Mountain Meadows.

“Since the Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred,” wrote southern Utah historian Juanita Brooks decades later, “we have tried to blot out the affair from our history.” Brooks believed she was doing her church a service by publishing her landmark book, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, in 1950, maintaining “that nothing but the truth can be good enough for the church to which I belong.” Though no official condemnation of her work came from authorities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, neither did any recognition.1

Just over fifty years later, historian Will Bagley introduced his own book on the subject, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, with the criticism that “the modern LDS church wishes the world to simply forget the most disturbing episode in its history.”2

In 2008, agreeing with Brooks’s conclusion that the atrocity “can never be finally settled until it is accepted as any other historical incident, with a view only to finding the facts,” and acknowledging that “only complete and honest evaluation” of the crime can bring true catharsis, we (along with coauthors Ronald W Walker and Glen M. Leonard) published Massacre at Mountain Meadows. 3 The book was a turning point, marking the first time that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints encouraged its historians to publicly lay bare this shameful episode in its history. The church’s support of that

effort included unfettered access to its previously restricted massacre-related sources and funding for researchers to scour archives and other sources across the United States.

The scope and findings of that research led to reckoning and change. Massacre at Mountain Meadows made its way into the hands of tens of thousands of readers and led church leaders, members, and others to understand and accept “more than we ever have known about this unspeakable episode,” said Latter-day Saint apostle Henry B. Eyring. Speaking to massacre victims’ descendants gathered at a September 11, 2007, sesquicentennial commemoration at the Mountain Meadows, Eyring shared an official apology on behalf of the church.4

Continued reconciliation efforts between the church and organizations of the victims’ relatives resulted in these disparate entities coming together to petition for and receive, in 2011, National Historic Landmark status for the Mountain Meadows, where monuments today memorialize the victims’ final resting place in the valley. “The designation means the United States has recognized that this site is among the most important in U.S. history,” National Park Service historian Lisa Wegman-French declared in a ceremony at the Mountain Meadows.5

All of the sources gathered and used in writing Massacre at Mountain Meadows were made available to the public in Salt Lake City’s Church History Library. Some of the most revealing sources were also published in two documentary histories: Mountain Meadows Massacre: The Andrew Jenson and David H. Morris Collections (2009) and Mountain Meadows Massacre: Collected Legal Papers (2017).

Yet the efforts that produced Massacre at Mountain Meadows were not complete. As the book’s preface explained, after considering the overwhelming amount of source material gathered, “we concluded, reluctantly, that too much information existed for a single book. Besides, two narrative themes emerged. One dealt with the story of the massacre and the other with its aftermath—one with crime and the other with punishment. This first volume tells only the

first half of the story, leaving the second half to another day.” With the publication of Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath, that day has come.

As one of the authors and the content editor of Massacre at Mountain Meadows, we combined our efforts to coauthor Vengeance Is Mine. We have concluded that the decision to tell the massacre story in two volumes was the right one, as it allowed us to explore the aftermath of the atrocity in greater detail than any previous work. The depth of that exploration has led us to new conclusions that change how the story has been told for generations.

Multiple raids on emigrant wagon trains in Utah Territory, both before and weeks after September 11, 1857, demonstrate that the train massacred at Mountain Meadows was not the only one attacked. These assaults were motivated by political wrangling over federal and local rule and tensions between church and state that reached a deadly peak in 1857 but roiled Utah for decades. Modern readers may recognize similar tensions today, not only in Utah but throughout the United States. This jostling for power between Latterday Saints and federal authority continued long after the massacre. Attempts to wield the case as a political weapon resulted in justice delayed—and justice denied—for the innocent victims of the massacre and their families.

For generations, the telling of the massacre and its aftermath has been shaped by an 1877 book titled Mormonism Unveiled; or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee; (Written by Himself). Attorney William W. Bishop published the volume a few months after the execution of his client, John D. Lee—the only man convicted for his role in the mass murder. Mormonism Unveiled went through nineteen printings within fifteen years of its publication and several more modern reprints, demonstrating just how influential this book has been for more than a century.6

Other books and portrayals of the massacre have liberally cited and quoted the words that Bishop claimed to be Lee’s. Based on our research, we conclude that Bishop altered and expanded Lee’s original and significantly shorter “confession” to publish Mormonism

Unveiled. We have therefore not relied on the account that Bishop attributed to Lee in Mormonism Unveiled, but on primary research, including new transcriptions of the original shorthand records of Lee’s two trials and other documents.

With the rare ability to read and transcribe nineteenth-century Pitman shorthand, our colleague LaJean Purcell Carruth created new transcripts of the original shorthand records of John D. Lee’s trials, along with never-before-transcribed passages from other legal proceedings and additional types of records. We cite Carruth’s transcriptions throughout our book. Readers can view the side-byside comparison of her trial transcriptions and the transcriptions made by nineteenth-century shorthand reporters at www.MountainMeadowsMassacre.org, under the “Trial Transcript Archive” tab.

Partly because of their reliance on Mormonism Unveiled, prior massacre historians have concluded that Lee’s trials and conviction were a mere appeasement to justice that closed the massacre case and vindicated church leaders. Our book shows that the pursuit of further convictions continued after Lee’s execution.

From the beginning of this project, our goal has been to make our work approachable for nonacademic readers, not just professional scholars. We believe our decision to tell the story in a narrative style is another reason Massacre at Mountain Meadows reached so many readers. We chose to continue that narrative format in this volume, though with interpretive signposts along the way to share our conclusions based on our decades of researching and writing about the massacre. While Vengeance Is Mine essentially picks up where Massacre at Mountain Meadows left off, the use of flashback and summary—often with new insights—will bring readers up to speed even if they have not read the first volume.

The primary sources we rely on for our book’s narrative reflect some of the erroneous beliefs of their time. While we feel it is important for modern readers to see how these prejudices of the past shaped the Mountain Meadows Massacre and its aftermath, we do not subscribe to them.

Nineteenth-century Euro-Americans did not typically distinguish between the vastly diverse original peoples and nations of the Americas, instead monolithically referring to all simply as Indians. In general, we have used tribal or band names—such as Paiute, Pahvant, Ute, and Shoshone—to identify these groups when we can, using Indian, Native, and Indigenous as synonyms occasionally for variety. Similarly, both Mormon and non-Mormon sources of the era refer to non–Latter-day Saints as gentiles We find this term objectionable today but use it in the text to reflect nineteenth-century parlance, in part because the alternative non-Mormon, which we also use for variety, has its downside.

Though this volume, like the first, benefited from extensive research funded by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints History Department, for the past several years we have written Vengeance Is Mine independent of church funding. From start to finish, we have had sole editorial control over our manuscript, and we alone are responsible for its contents.

Richard E. Turley Jr. Barbara Jones Brown

The Angel of Peace Should Extend His Wings

Salt Lake City and Mountain Meadows, September 11, 1857

On September 11, 1857, a tall, slender girl approached a pair of offices nestled between two mansions. The elegant structures must have intimidated the sixteen-year-old, who lived her life in roughhewn houses and stone forts. Gathering her skirts and her nerve, she stepped through the door marked “President’s Office.”

Figure 1.1 Left to right: Brigham Young’s Lion House, church president’s office, governor’s office, and Beehive House. Courtesy Church History Library.

As her eyes adjusted to the coolness of the brick-and-plaster interior, she made out several clerk desks. In a ledger labeled “Sealings Record,” a clerk recorded her name, birthdate, and birthplace: “Sarah Priscilla Leavitt; 8 May 1841; Nauvoo, Illinois.” On

the line above, the clerk took down the same information for the man who came in with her: “Jacob Hamblin; 2 April 1819; Ashtabula County, Ohio.”1

Priscilla and Jacob creaked up a staircase to the second story, where they met with the man who was both Utah’s governor and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, fifty-sixyear-old Brigham Young.2

Figure 1.2 Brigham Young, 1855. Courtesy Church History Library

Priscilla and Jacob clasped hands as Young pronounced the words of their marriage ceremony, which the Latter-day Saints called

a “sealing.” When Priscilla accepted Jacob’s proposal weeks before, he gave her the options of marrying in southern Utah, where they lived, or waiting until he could bring her here, to Salt Lake City. She chose this place. Priscilla Leavitt’s marriage was unusual by American standards, but not because of her youth. Rural girls of the day often wed by sixteen, sometimes marrying established men who were much older. Priscilla’s marriage was peculiar because Jacob already had a wife.3

At that moment, thirty-five-year-old Rachel Hamblin—whom Jacob called his “kind[,] effctionate companion”—was three hundred miles south in a highland basin called the Mountain Meadows. The year before, Rachel and Jacob had moved their family to the north end of the pristine valley to start a summer ranch.4

The Hamblin and Leavitt families had long been intertwined. Two of Priscilla’s older sisters both married Jacob’s brother William, and Rachel employed Priscilla around the house. In early August 1857, when Brigham Young called Jacob to head his church’s Southern Indian Mission, Jacob chose Priscilla’s brother Dudley as one of his two mission counselors. Rachel chose Priscilla to be not only a “plural wife” for Jacob but also a helpmeet and companion for herself.

“I told them both,” Priscilla said, “that I loved this family well enough to help them, and to give them my love and care. Since Brother Jacob had to be away from home so much on church business and missionary work with the Indians, I felt very humble in accepting this great responsibility.” In polygamous Latter-day Saint culture, a plural wife did not just marry a husband; she married his family.5

As Priscilla and Jacob took their marriage vows at 11:55 a.m., dozens of Mormon militiamen readied themselves for action at the Mountain Meadows, four miles south of the Hamblin ranch. They lined the wagon trail that ran through the valley’s luxuriant grass. The ragtag men faced a circle of besieged wagons some distance from where they stood. Above the encircled wagons, they could make out a white flag, hung from a pole in desperation.6

The militiamen watched as a leader from their ranks, Major John D. Lee, hoisted his own white swag on a stick and walked toward the

wagon fort. After a brief negotiation, iron jangled as the emigrants inside removed chains connecting their wagons at the wheels. After their barricade opened, Lee disappeared into the circle with two other men, both driving wagons. One was Samuel Knight, Jacob Hamblin’s other counselor in the Indian mission. The remaining militiamen outside waited for an hour or more, clutching their guns, sweating in the midday sun, thinking about what they were soon to do.7

That evening in Salt Lake, a newly arrived visitor joined his Latterday Saint hosts for supper. Captain Stewart Van Vliet was a quartermaster for hundreds of U.S. troops headed for Utah. The army had sent Van Vliet ahead with the “ostensible errend . . . to Learn wheather certain Supplies could be procured for the troops ‘enroute’ for this place,” Young concluded, “but it is generally thought that he has been Sent here as a feeler to know & find out the mind of the people.” Young gave Van Vliet his answer: the soldiers must not come into Utah’s settlements. If the troops continued their advance, his people would resist.8

This was not Van Vliet’s first meeting with the Mormons. A decade earlier, he gained their trust when he visited their refugee camps along the Missouri River after mobs drove them from their homes in Illinois. Now, at the September 11 dinner, Van Vliet arose and asked the privilege to speak. “He warmly expressed gratitude for his former and present acquaintance and associations” with the Saints. “His prayer should ever be,” he said, “that the Angel of Peace should extend his wings over Utah.”9

About the same time, near sundown at the Mountain Meadows, Lee, Knight, and several other militiamen arrived at the Hamblin shanty in time for their supper, drawing two wagons to Rachel Hamblin’s door. Though she had heard gunshots throughout the week and “a firing greater than before” earlier that day, Rachel must have been shocked at what she saw in the wagon beds—seventeen blood-stained children, most of them crying. Their hair was tangled and their clothes filthy from what they had endured over the past five days. Seven were infants not yet two years old. The other ten ranged from ages two to six.10

Blood oozed from one toddler’s ear. A one-year-old girl’s left arm dangled by the flesh just below the elbow. The ghastly wound made one militiaman think she would die. Yet these children were lucky to make it this far. Behind them on the killing fields lay the butchered bodies of their parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. The children in the wagons were all who remained of what had been a bustling train of more than a hundred California-bound emigrants.11

The tear-stained girls and boys, along with two quilts, were pulled from the wagons and passed to Rachel, who was already caring for several children of her own. Some were her stepchildren, some adopted, and three she’d had with Jacob. She could not shield her youngsters from the trauma of seeing the bloodied and wailing little ones. Instead, the older Hamblin children must have helped their mother care for the survivors, who cried in vain for their own mothers. Rachel left no account of how she and some two dozen children at the ranch got through that horrific night. Her adopted Shoshone son, a teenager named Albert, recounted that “the children cried all night.” He never got over the horror of that September 11.12

Outside, in the Mountain Meadows, the militiamen made their own beds under the blackening heavens. John D. Lee unrolled his blanket, laid his head back, and fell into an oblivious sleep.13

Sermons Like Pitch Forks

New York to Utah, 1830‒57

In the summer of 1857, Elizabeth Knight Johnson bent over her handiwork, her aging fingers pulling needle and thread through scraps of fabric. She and her Salt Lake City neighbors were making quilt squares they hoped to bind together in time for October’s territorial fair Beginning in late July, they had another reason to hurry They worried they might soon be abandoning their homes. Their fears were born from experience, and, perhaps more than any of them, Elizabeth knew the trauma of fleeing.1

At age thirteen in 1830, she joined a church just established not far from her home in Colesville, New York. Elizabeth and her extended Knight family formed most of one of its first congregations. Believing God had chosen the faith’s prophet-leader, Joseph Smith, to restore Jesus Christ’s primitive church in modern times, or “the latter days,” the Knights supported Smith during his translation of the Book of Mormon. A man in his early twenties, Smith taught that early inhabitants of the Americas—descendants of the biblical Israel— recorded the book of scripture on gold plates he found buried near his home in Palmyra, New York.2

Smith eventually called the new faith the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Its divine mission was to usher in Christ’s millennial return by building a new Zion on the American continent. To follow their prophet and escape persecution, Elizabeth Knight’s family left Colesville, gathering to Ohio with a growing body of “Latter-day Saints” or “Saints,” as they came to call themselves. A few months later they were on the move again.3

As the Saints proliferated, so did the controversy surrounding them and their prophet. Through the 1830s and 1840s, they tried to establish their permanent home and Zion, sojourning in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. Some of their beliefs and practices—including communitarianism, theocracy, bloc voting, and the emerging practice of polygamy—ran against American mainstream values of capitalism, individualism, democracy, and monogamy.

Reacting to these practices, vigilante mobs used violence, including mass murder, to drive “Mormons,” as they called them, from their communities. At times the Saints fought back, only to be overwhelmed by more violence and then fleeing to a new place. With their religious minority status, the Saints’ petitions to federal and local governments failed to bring redress or lasting protection.4

The Latter-day Saints, including Elizabeth Knight and her kin, paid a heavy toll for their beliefs. The greatest blow came in 1844, five years after they established a city called Nauvoo on the Illinois side of the Mississippi. A mob disguised with painted faces assassinated Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum in the nearby Carthage Jail. The two were awaiting a hearing on a treason charge for declaring martial law and calling out their state militia unit to protect Nauvoo from anticipated attack. The Smiths’ murder struck close to home for Elizabeth. Not only had her family known Joseph since she was a child, Hyrum had baptized her in 1830 and performed her marriage to Joseph Johnson in 1842.5

After the Carthage murders, Latter-day Saint apostle Brigham Young became the leader of the main body of Smith’s followers, continuing his legacy. Illinois governor Thomas Ford later observed that the Smiths’ murders, instead of ending their religion, “as many believed it would,” only “gave them new confidence in their faith.”6

At Nauvoo, they finished building the temple Smith began. Before his murder, the prophet-leader introduced a ceremony called the endowment through which initiates made covenants to prepare Zion for Christ’s Second Coming and their souls to return to God in the afterlife.7 The temple was a holy place where Latter-day Saints received their endowment and “sealed” their marriages for eternity. Elizabeth Knight Johnson and her husband were among several

thousand Saints who were endowed and sealed in the Nauvoo temple after Smith’s death.8

The endowment was a strictly oral ceremony, believed too sacred to write down.9 Speaking in 1845 of one promise or “covenant” of the rite, a church leader shared his interpretation that “I have covenanted, and never will rest nor my posterity after me until those men who killed Joseph and Hyrum have been wiped out of the earth.”10 Abraham Cannon, son of apostle George Q. Cannon and an apostle himself, said his father told him “that he understood when he had his endowments in Nauvoo that he took an oath against the murderers of the Prophet Joseph as well as other prophets, and if he had ever met any of those who had taken a hand in that massacre he would undoubtedly have attempted to avenge the blood of the martyrs.”11

The concept of avenging the blood of martyred prophets appeared in the Book of Mormon, in which the blood of slain prophets cried unto “God for vengeance upon those who were their murderers.”12 But it was not unique to Latter-day Saint thought. The Old Testament records that God commanded an Israelite king to “avenge the blood of my servants the prophets.”13 In the New Testament, Jesus taught that “the blood of all the prophets, which was shed from the foundation of the world, may be required of this generation,” and the apostle John shared a related vision of the world’s end days. “I saw . the souls of them that were slain for the word of God,” John wrote. “They cried with a loud voice, saying, How long, O Lord, holy and true, dost thou not judge and avenge our blood?”14

Latter-day Saints had varying interpretations of what avenging the blood of the prophets meant. The people of Nauvoo did not use violence to avenge the Smiths’ deaths. Instead, apostle Willard Richards, who witnessed the brutal murders, urged his people to remain still. After hearing Richards’s impassioned speech, “a vast assemblage” in Nauvoo, “with one united voice,” wrote a Mormon reporter, “resolved to trust to the law for a remedy of such a high handed assassination,” and “to call upon God to avenge us of our wrongs!”15

Brigham Young believed that God would command his people to avenge the blood of prophets before the world’s end, though he did not know exactly how or when. He told apostle Wilford Woodruff in 1856 that “were we now Commanded to go & avenge the Blood of the prophets,” the Saints would not “know what to do.” Fortunately, Young confided to Woodruff, “there is one thing that is a consolation to me[.] And that is I am satisfied that the Lord will not require it of this people untill they become sanctifyed & are led by the spirit of God so as not to shed inocent Blood.”16

In late 1845, Latter-day Saint leaders in Nauvoo planned yet another mass exodus. “To hasten their removal,” Illinois governor Thomas Ford admitted, the twelve apostles “were made to believe that the [U.S.] President would order the regular army to Nauvoo” to arrest them as soon as the frozen Mississippi thawed and troops could travel upstream by riverboat.17 Speaking to a congregation, apostle Heber C. Kimball expressed his belief that “the Twelve [apostles] would have to leave shortly, for a charge of treason would be brought against them” for swearing their people “to avenge the blood of the anointed ones.”18

Young and other apostles began leading the Saints’ westward flight across the icy Mississippi in early 1846. Knowing that the Mormons had no choice but to sell out, “people from all parts of the country flocked to Nauvoo to purchase houses and farms,” Ford said, “which were sold extremely low, lower than the prices at a sheriff’s sale.”19 Isaac Haight, later a church leader in southern Utah, was one of those forced to sell, trusting “in the Lord,” he said, “that he will open the way for us to get away from this wicked nation, stained with the blood of the Prophets.”20

Carrying provisions in their wagons and bitterness in their souls, the Saints put behind them not only the state of Illinois but the borders of the nation. “We owe the United States nothing,” railed British-Canadian apostle John Taylor. “We go out by force as exiles from freedom. The Government and people owe us millions for the destruction of life and property in Missouri and in Illinois. The blood of our best men stains the land, and the ashes of our property will

preserve it till God comes out of his hiding place, and gives this nation a hotter portion than he did Sodom and Gomorrah.”21

Elizabeth Knight Johnson and her husband left Nauvoo and the graves of their first two children. They and the other refugees spent months in makeshift camps across Iowa and along the Missouri River Hundreds of graves peppered their path from Nauvoo to their winter quarters as hunger, malaria, tuberculosis, and scurvy took their toll.22

In these conditions, Elizabeth gave birth to another child and buried her father and an older brother. Her now-orphaned nephew, fourteen-year-old Samuel Knight, had already suffered the death of his mother in Missouri.23 Working as a wagon driver, Samuel set out with an advance train of Saints in the summer of 1847, traveling more than a thousand miles west. Believing the West would free his people from their trials, Brigham Young envisioned the isolated Great Basin as the place they would permanently call Zion.24

The Saints were not the only Americans looking west. Their migration unfolded in an era of expansionism, when Anglo-Americans claimed a divine mandate, a “Manifest Destiny,” to spread “white civilization” throughout the Western Hemisphere. Government leaders encouraged emigration as a means of colonizing new territory, empowering the nation through occupying the land and exploiting its resources.25

In 1845, the United States annexed the independent Republic of Texas, which had been part of Mexico, and provoked the U.S.Mexican War.26 West Point graduate Stewart Van Vliet fought in the conflict, helping win the war.27 The resulting 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo forced Mexico to sell much of its northern territory in what became all or large parts of California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah.28

After his Mexican tour, Van Vliet transferred to Fort Kearny, in what would become Nebraska. Van Vliet visited the Mormon refugee camps in the area and over the years gave some Saints muchneeded work.29

Joseph and Elizabeth Knight Johnson trekked to the Salt Lake Valley in 1848 when Elizabeth was pregnant with twins. Her babies died on the plains the day they were born.30 After settling in Salt Lake, the couple took in Elizabeth’s orphaned nephew, Samuel. Joseph taught him his trade of making adobe bricks for building.31

The 1848 treaty with Mexico brought the Latter-day Saints, barely forging a new life in the Salt Lake Valley, back under the U.S. rule they had traveled more than a thousand miles to escape. They first drafted a petition for territorial status, then sought statehood instead after learning it would give them far more autonomy, including the right to elect all their own leaders. But Congress made Utah a territory instead. The vast territory essentially extended from upper California’s eastern border to the continental divide, encompassing all or parts of what later became Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, and Colorado.32

President Millard Fillmore granted the Saints some self-rule when he appointed Mormons to half the territorial positions in 1851, including Young as governor and superintendent of Indian affairs. The other appointees were non-Mormons, or “gentiles,” as early Mormons called them.33

Though the Saints were unpopular, at first their westward migration fulfilled the U.S. government’s desire for white Americans to colonize the newly acquired territory. Believing in their own manifest destiny, the Saints began expanding their “kingdom of God” on earth as soon as they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Their version of expansionism included polygamy, a marital system they believed extended into the afterlife.34

By the mid-1850s, Mormon settlement expanded as far north as Oregon Territory’s Salmon River, as far west as Carson Valley near northern California’s border, and southwest to San Bernardino, California. Mormons built settlements along the “northern route,” which led from Salt Lake City to Oregon Territory or northern California, and along the “southern route,” which passed from Salt Lake through the deserts of southwest Utah to southern California. Watering places along the trails brought settlers and travelers into