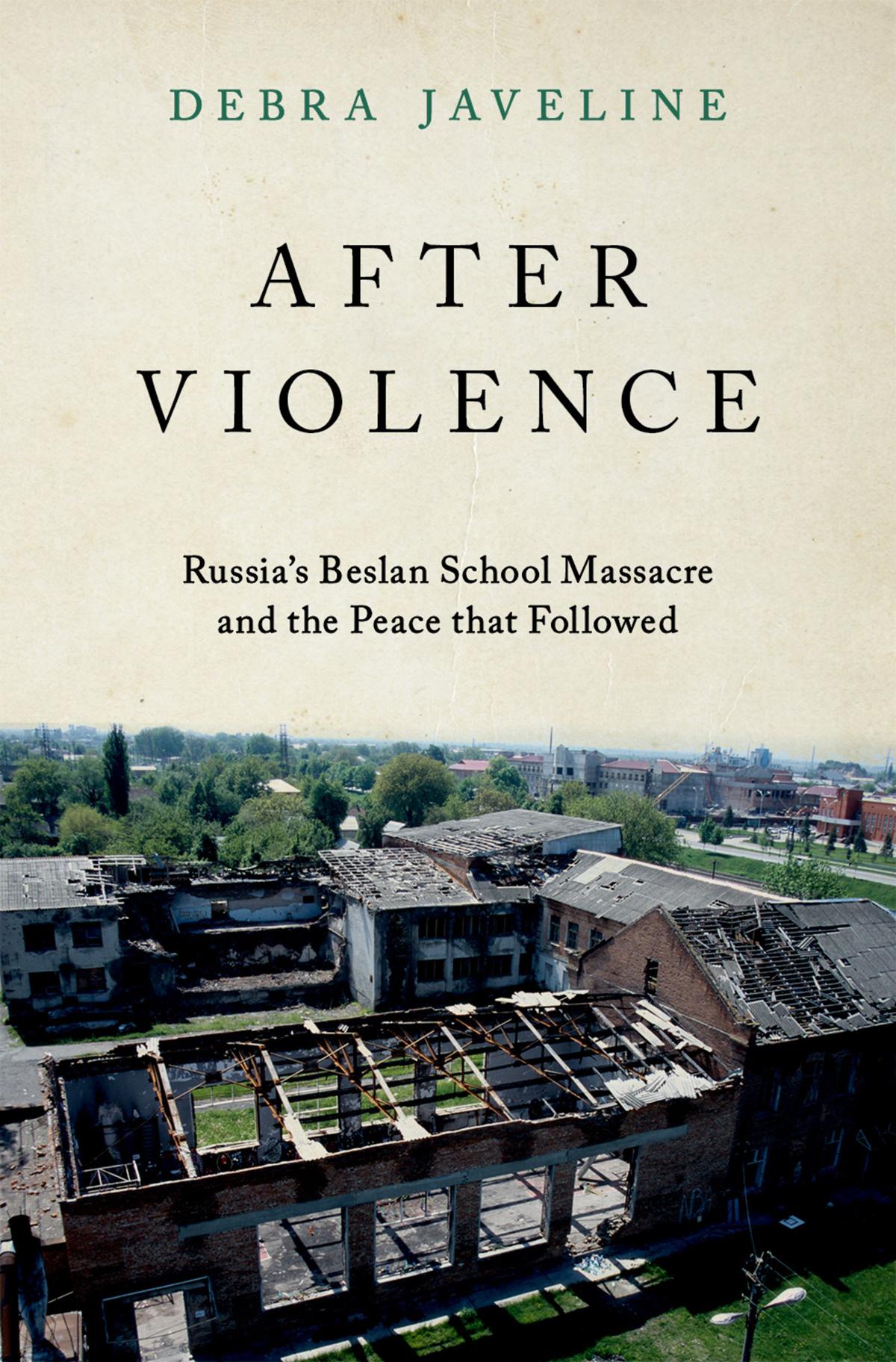

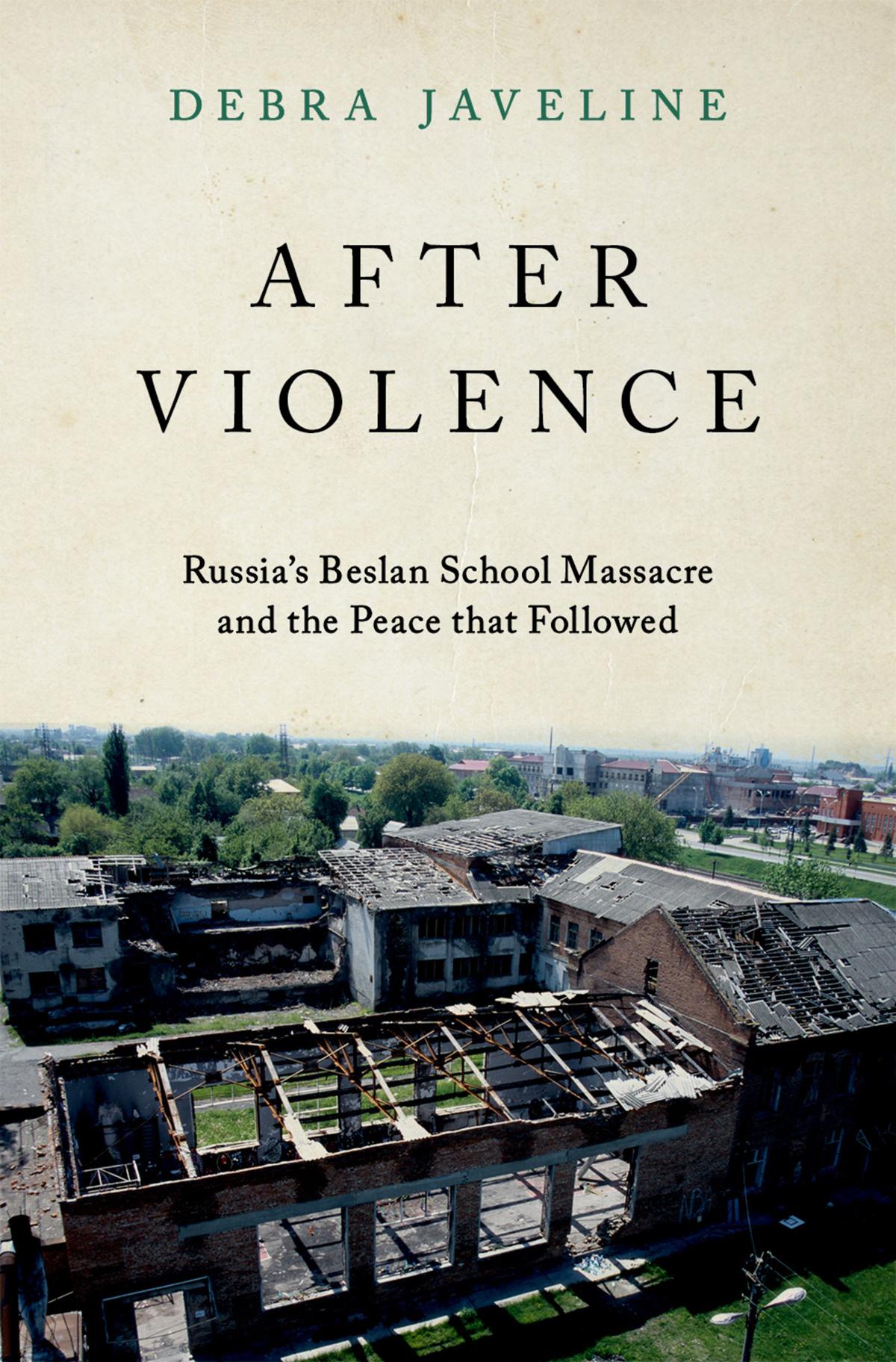

After Violence

Russia’s Beslan SchoolMassacre andthe Peace That Followed

DEBRA JAVELINE

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Javeline, Debra, 1967– author.

Title: After violence : Russia’s Beslan school massacre and the peace that followed / Debra Javeline.

Description: First Edition. | New York : Oxford University Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022058618 (print) | LCCN 2022058619 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197683347 (Hardback) | ISBN 9780197683354 (epub) | ISBN 9780197683361

Subjects: LCSH: Beslan Massacre, Beslan, Russia, 2004. | Terrorism Russia— History 21st century. | Violence Psychological aspects.

Classification: LCC HV6433.R9 J38 2023 (print) | LCC HV6433.R9 (ebook) | DDC 363.3250947 dc23/eng/20221207

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022058618

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022058619

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197683347.001.0001

TothepeopleofBeslan.Yourpainisnotforgotten.Yourpeaceful activismisadmiredandappreciated.

Figures

Tables

Acknowledgments

GlossaryofIndividuals

Introduction: Peace after Violence in Beslan

PART I. THE BESLAN SCHOOL HOSTAGE TAKING

Grievances against Ethnic Rivals

Political Grievances

The Surprisingly Nonviolent Aftermath

The Surprisingly Political Aftermath

PART II. WHY POLITICS AND NONVIOLENCE?

Anger and Other Emotions

Ethnic Prejudice

Political Alienation and Blame

Social Alienation versus Social Support

Self-Efficacy and Political Efficacy

Biography: Demographics, Prior Harm, and Prior Activism

A Portrait of Political Activists and Violent Retaliators

13. PART III. GENERALIZING FINDINGS FROM BESLAN VICTIMS

Should Results Apply to Nonvictims?

Should Results Apply to Victims in Other Places and Times?

Conclusion: Peace after Violence

AppendixA:ChronologyofActivitiesaftertheBeslanSchoolHostage Taking

AppendixB:SurveyandFocusGroupMethodologies

References

Index

11.1.

11.2.

11.3.

11.4.

11.5.

Figures

Support for retaliatory violence by level of political participation

Support for retaliatory violence short of killing by level of political participation

Predicted number of political activities with other variables held constant at means

Magnitude of effects on political participation, predicted probabilities

Magnitude of effects on support for retaliatory violence, predicted probability that a victim would somewhat or fully approve of killing Chechens

I.1. I.2. I.3. I.4.

2.1.

2.2.

3.1.

3.2. 4.1. 4.2. 4.3. 5.1. 5.2. 5.3. 5.4. 5.5. 5.6.

Tables

Examples of Study Samples

Beslan Victim Survey: Respondent Description and Response Rate

Nonvictim Surveys Response Rates

Focus Group Composition

Hotly Contested Questions about the September 2004 School

Hostage Taking in Beslan

Number of Hostages, Deaths, and Injuries

Support for Retaliatory Violence among Beslan Victims

Support for Less Extreme Retaliatory Violence among Beslan Victims

Political Participation of Beslan Victims in Specific Activities

Cumulative Political Participation of Beslan Victims

Categories of Political Participation of Beslan Victims

Emotions of Beslan Victims

Anger and Political Participation

Anger and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Emotions, Political Participation, and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Interactive Effects of Anger and Social Alienation on Support for Retaliatory Violence

Hypothesized Interactive Effects of Anger on Support for Retaliatory Violence

5.7.

5.8.

5.9.

6.1.

6.2.

6.3.

6.4.

6.5.

6.6.

6.7.

6.8.

7.1.

7.2.

7.3.

7.4.

7.5.

7.6.

7.7.

8.1.

8.2.

9.1. 9.2.

9.3.

9.4.

9.5.

10.1.

Anger and Other Explanatory Variables

The Similar Role of Emotions in Moderate versus Extreme

Political Action

Depression among Beslan Victims

Attitudes of Beslan Victims toward Ingush

Prejudice of Beslan Victims

Attitudes toward Ingush and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Prejudice Index and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Blaming Chechens and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Interactive Effects of Anger with Prejudice and Blaming

Chechens on Support for Retaliatory Violence

Attitudes toward Ingush and Political Participation

Prejudice Index and Political Participation

Political Alienation, Shame, and Blame among Beslan Victims

Political Alienation and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Shame and Blame and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Political Alienation and Political Participation

Shame and Blame and Political Participation

Hypothesized Interactive Effects of Political Alienation/Blame and Efficacy

Political Alienation/Blame and Efficacy

Social Alienation and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Social Alienation and Political Participation

Self-Efficacy and Political Efficacy among Beslan Victims

Self-Efficacy and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Self-Efficacy and Political Participation

Political Efficacy and Political Participation

Optimism and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Prior Harm and Support for Retaliatory Violence

10.2.

Prior Harm and Political Participation

10.3.

10.4. 11.1.

11.2. 11.3. 11.4. 11.5.

12.1. 12.2.

12.3.

12.4.

B.1.

B.2.

Prior Political Activism and Political Participation

Demographics, Political Participation, and Support for Retaliatory Violence

Participatory Acts of Beslan Victims by Level of Support for Retaliatory Violence

Correlations of Support for Violent Responses to the Hostage Taking

Participatory Acts of Beslan Victims by Approval of Responses to the Hostage Taking Measures

Explaining Peaceful Political Participation and Retaliatory Violence

Political Participation of Victims and Nonvictims

Explaining Nonvictim Responses to Violence

Support for Retaliatory Violence among Victims and Nonvictims

Comparing Beslan and Vladikavkaz Nonvictim Responses to Violence

Age, Gender, and Education: Nonvictim Survey and Census Comparisons

Focus Group Participant Recruitment

Acknowledgments

This entire book is an acknowledgment, an expression of profound appreciation for the fortitude of the people of Beslan.

To those victims who agreed to participate in surveys and/or focus groups, thank you for sharing your stories. I hope I have treated these stories and the memories of your loved ones with the dignity and respect they deserve, and I hope my interpretations of events after the school hostage taking have done justice to your complex and difficult situations. I am grateful for the privilege of learning from you. Hearing your concerns and frustrations, I understand that you yourselves often see the ineffectiveness of your public actions after the terrorist attack that forever changed your lives. I hope that this narrative of your actions may slightly alter your perspective, for even if you were received poorly by the authorities and sometimes by each other, I see much in your overall reaction that could serve as a model for other communities. You did the best you could under extraordinarily horrible circumstances, and thanks to you, violence in your region did not spiral into greater violence. Given the interethnic violence plaguing other regions of the world, the peaceful outcome after violence in Beslan is worthy of global gratitude.

Thank you to the many Russian journalists who courageously covered the aftermath of the Beslan school hostage taking with incredible thoroughness, sensitivity, and insight. I am especially indebted to Elena Milashina and Marina Litvinovich, without whom I and the world would have a far weaker understanding of the terrorist attack and victim activism.

Thank you to Anna Andreenkova and her talented staff at the Institute for Comparative Social Research (CESSI) for collaborating

and implementing the surveys and focus groups from which this book’s findings are drawn. I cannot imagine a more fulfilling partnership. Thank you to Vanessa Baird who began this journey with me and contributed greatly to survey and focus group methodologies and data analysis. The book builds on Javeline and Baird (2011). Thank you to Betsy Brooks, one of the most impressive undergraduates I have ever taught, who collaborated on the chronology in the Appendix and helped puzzle through inconsistencies in the official and unofficial records of the hostage taking.

Several scholars read parts of this manuscript and offered thoughtful feedback that shaped the final product. Many thanks to Dave Campbell, Matt Evangelista, Evgeny Finkel, Jill Gerber, Sarah Lindemann-Komarova, Kim Marten, Jim McAdams, and Roger Petersen. Mark Beissinger and Sid Tarrow went above the call of duty in providing detailed, highly critical but always constructive and helpful comments. Tim Colton has my special gratitude as advisor and friend throughout the years who helped usher the manuscript to ultimate publication. Ruth Abbey also has my special gratitude for friendship and insightful guidance along the way.

Funding for surveys, focus groups, and writing was generously provided by the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, as well as Notre Dame’s Nanovic Institute for European Studies, Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts (ISLA), Kellogg Institute for International Studies, and Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. ISLA also generously funded indexing and permissions to use the book’s cover and interior images. Notre Dame colleagues Matthew Sisk and Monica Moore have my deep thanks for assistance with map creation and image searching, respectively, as do David McBride and his team at Oxford University Press for decisively steering the publication process. Early versions of the manuscript were presented at Indiana University’s Department of Political Science and Russian & East European Studies program and the University of PennsylvaniaTemple University European Studies Colloquium; conferences of the Southern Political Science Association, Midwest Political Science

Association, American Political Science Association, Program on New Approaches to Russian Security (PONARS), and Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies; and the University of Notre Dame’s Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy, Kellogg Institute for International Studies, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, and Social Movements and Politics workshop. I thank all participants for helpful feedback.

I have the good fortune and privilege to love and be loved by my cherished adult family, Tony Ciliberti, Barbara Javeline, Brian Javeline, Lucy Venegas, Jodi Simons, Clayton Simons, Jill Gerber, Cynthia Belis, Stephen Belis, Carol Rose, Sylvia Tesh, Carol Smith, and Philip Smith, and to enjoy the fond memories of Anna Goldberg, Lester Soloway, Ilene Singer, Don Singer, Elaine Rose, and Stanley Goldberg. I also have the good fortune and privilege to parent three amazing kids, Jake, Gabrielle, and Danielle, to be an aunt to my fantastic nieces, Taylor, Jennifer, Hailey, and Lindsey, and to be a special kind of aunt, Aunt Jav, to the fabulous Sam, Alex, and Jessie. During the writing of this book, these privileged roles allowed me to appreciate the gravity of the loss of a child, if one could even do so, because the mind fights a parent on daring to imagine the kind of loss faced by Beslan parents. I cried from imagining, I cried from fighting the imagination. I hope the writing that emerged was better for the struggle. I thank all these wonderful people with whom I am lucky enough to share my life.

Glossary of Individuals

Beslan activists

Bzarova, Emilia Voice of Beslan

Diova, Zalina Voice of Beslan

Dudiyeva, Susanna Mothers of Beslan

Gadiyeva, Aneta Mothers of Beslan

Guburova, Zalina Mothers of Beslan

Karlov, Valery Independent activist

Kesayeva, Ella Voice of Beslan

Khamitseva, Alma Voice of Beslan

Kochishvili, Mziya Mothers of Beslan

Kokoity, Mziya Mothers of Beslan

Margiyeva, Svetlana Voice of Beslan

Melikova, Marina Voice of Beslan

Nogayev, Elbrus Retired lieutenant colonel of Beslan police investigations department

Pak, Marina Mothers of Beslan

Sabanov, Azamat Independent activist

Sidakova, Rita Mothers of Beslan

Tagayeva, Emma Voice of Beslan, wife of Ruslan Betrozov, sister of Ella Kesayeva

Tebiyev, Ruslan Independent activist

Techiyeva, Rita Mothers of Beslan

Tedtov, Elbrus Editor-in-chief of local Beslan newspaper, Zhizn Pravoberezhnya, former police officer

Tuayeva, Elvira Mothers of Beslan

Tuayev, Mairbek Chairman of Beslan Public Council

Frequently referenced former hostages

Betrozov, Ruslan Father, assassinated

Dudiyeva, Fatima Police officer

Mamitova, Larisa Doctor

Tsaliyeva, Lydia Former principal of Beslan School No. 1

Officials of the Russian Federation

Anisimov, Vladimir Deputy Director of Federal Security Service until 2006

Aslakhanov, Aslambek Advisor to President Putin on the Caucasus 2004–2008

Chaika, Yuri Prosecutor General 2006–2020

Fridinsky, Sergei Deputy Prosecutor General for Southern Federal District until 2004

Khloponin, Alexander Presidential Envoy to North Caucasus Federal District 2010–2014

Kolesnikov, Vladimir Deputy Prosecutor General 2002–2006

Kozak, Dmitry Presidential envoy to Southern Federal District 2004–2007

Krivorotov, Konstantin

Lead investigator for Prosecutor General’s official investigation until 2005

Medvedev, Dmitry President 2008–2012, Prime Minister 2012–2020

Nurgaliyev, Rashid Minister of Internal Affairs 2003–2012

Patrushev, Nikolai

Federal Security Service Director 1999–2008

Peskov, Dmitry Spokesperson for Vladimir Putin 2000–present

Pronichev, Vladimir Deputy Director of Federal Security Service until retirement in 2013

Putin, Vladimir President 2000–2008 and 2012–present, Prime Minister 1999–2000, 2008–2012

Savelyev, Yuri Former Rector of St. Petersburg Institute of Military Mechanics, State Duma deputy and dissenting member of Torshin commission, conducted independent investigation

Shepel, Nikolai Deputy Prosecutor General for Southern Federal District 2004–2006

Sobolev, Viktor Lieutenant General and Commander of 58th Army 2003–2006

Sydoruk, Ivan Deputy Prosecutor General for Southern Federal District 2006–2012

Tikhonov, Alexander General and Special Forces Commander of Federal Security Service

Tkachov, Igor Lead investigator for Prosecutor General’s official investigation as of September 2005

Torshin, Alexander Federation Council Deputy Speaker, head of parliamentary commission investigation

Ustinov, Vladimir Prosecutor General 2000–2006, Presidential Envoy to Southern Federal District 2008–present

Officials of the Republic of North Ossetia

Aguzarov, Tamerlan Chief Justice of North Ossetia’s Supreme Court, 1999-2011

Andreyev, Valery Director of Federal Security Service until 2004

Bigulov, Alexander Prosecutor until 2006

Dzantiyev, Kazbek Minister of Internal Affairs until 2004

Dzasokhov, Alexander President 1998–2005, Federation Council member 2005–2010

Dzgoyev, Boris Minister of Emergency Situations 1997–unknown

Dzugayev, Lev Presidential Press Secretary until 2004, Minister of Culture and Mass Communications 2004–unknown

Gobuyev, Oleg Mayor of Beslan

Kesayev, Stanislav Deputy Speaker of Parliament, head of republic’s independent investigation

Khalin, Alexei Lead investigator for Prosecutor’s Office 2009–unknown

Mamsurov, Taimuraz President 2005–2015, Parliament leader 2000–2005

Solzhenitsyn, Alexander Lead investigator for Prosecutor’s Office until 2009

Zangionov, Vitaly Officer of Federal Security Service, official negotiator during hostage taking

Other officials or public individuals

Aidarov, Miroslav Director of Pravoberezhny District Department of North Ossetian Interior Ministry, tried for negligence and amnestied

Aushev, Ruslan President of Ingushetia 1993–2001

Chedzhemov, Taimuraz Attorney for Beslan victims until 2007

Dryayev, Georgy Chief of Staff of Pravoberezhny District Department of North Ossetian Interior Ministry, tried for negligence and amnestied

Grabovoi, Grigorii Tried and convicted self-declared messiah who claimed to resurrect the dead

Gurazhev, Sultan Ingush police officer abducted and released by hostage takers on route to Beslan

Gutseriyev, Mikhail Former Deputy Speaker of Russian State Duma, president of Rusneft oil company, unofficial negotiator during the siege

Kotiyev, Akhmed

Former Deputy Director of Malgobek [Ingushetia] District Division of Internal Affairs, tried for negligence and acquitted

Martazov, Taimuraz Deputy Head of Public Security of Pravoberezhny District Department of North Ossetian Interior Ministry, tried for

Maskhadov, Aslan

negligence and amnestied

Former President of Chechnya and separatist leader

Roshal, Leonid Moscow pediatrician, unofficial negotiator during the siege

Yevloyev, Mukhazhir

Former Director of Malgobek [Ingushetia] District Division of Internal Affairs, tried for negligence and acquitted

Zyazikov, Murat President of Ingushetia 2002–2008

Journalists

Allenova, Olga Kommersant

Chivers, C. J. The New YorkTimes, Esquire

Farniyev, Zaur Kommersant

Litvinovich, Marina Pravda Beslana

Marzoyeva, Emma Caucasian Knot

Meteleva, Svetlana Moskovskiikomsomolets

Milashina, Elena Novayagazeta

Politkovskaya, Anna Novayagazeta, book author

Shavlokhova, Madina Izvestia, Kommersant, Gazeta

Tokhsyrov, Vadim Kommersant

Voitova, Yana The Moscow Times

Militants

Basayev, Shamil Chechen rebel leader and presumed mastermind of the Beslan attack

Khodov, Vladimir Wanted terrorist, second-in-command of the hostage takers, known as Abdul or Abdulla

Khuchbarov, Ruslan Wanted terrorist, leader of the hostage takers, known as Polkovnikor “Colonel”

Kulayev, KhanPasha Brother of Nur-Pasha

Kulayev, Nur-Pasha Surviving hostage taker, captured, tried, and presumably incarcerated for life

The town of Beslan (C) is located in the North Caucasus (B) of the Russian Federation (A).

Credit: Matthew Sisk.

Unrealized Expectations of Retaliatory Violence

In 2004, political officials and observers of the North Caucasus commonly predicted ethnically motivated revenge attacks in retaliation for the school siege (Dyupin 2004; Weir 2004). Some suggested the possibility of full-scale ethnic violence and war. Indeed, surviving and incarcerated hostage taker Nur-Pasha Kulayev claimed that the Beslan hostage taking was specifically designed to provoke Ossetians to conduct revenge attacks on Ingush and Chechens and thereby foster greater ethnic conflict, violence, and outright war throughout the North Caucasus. President Vladimir Putin too suggested that inciting conflict was the aim of the hostage takers who hoped that their violent act would serve as a trigger and ignite fighting. In a national address, he said that the hostage takers and their bosses tried to provoke further conflict and “rupture the fragile balance” of ethnic and religious differences in the region (Mydans 2004b). “Those who have sent bandits to commit this heinous crime have aimed at setting our peoples against one another, intimidating the citizens of Russia and unleashing a bloody feud in the North Caucasus” (Sands 2004a).

Former president of Ingushetia, Ruslan Aushev, warned, “The Caucasus is on the threshold of a new ethnic war. The war in Chechnya might look like nothing in comparison with this possible war” (Mite 2004). Ruslan Khasbulatov, former speaker of the Russian parliament, commented, “One push, like a new Ossetian-Ingush war, and the entire Caucasus will be engulfed in one bloody, senseless and hopeless melee that Russia will not have enough troops to contain” (McAllister and Quinn-Judge 2004). A local policeman agreed, “It would take just one match and this whole place would go up in flames. . . . No one is going to forgive, that’s certain. This is the Caucasus. That doesn’t happen. . . . wait till the 40 days [of traditional mourning] are over,” and the policeman made a cutting motion with one hand across the palm of the other (Mydans 2004b).

Adding fire to these expectations of retaliatory violence, local authorities were reported as saying that “a criminal has a nationality,” and local newspapers published lists of terrorists’ names and nationalities (Mite 2004), with “Chechen” and “Ingush” predominating. Deputies to Ingushetia’s parliament, the National Assembly, were concerned enough about the possibility of retaliatory violence to adopt a formal appeal to their counterparts in North Ossetia. On October 6, 2004, the Ingushetian deputies warned of a concerted campaign to sow interethnic discord across the North Caucasus and called for measures to end rhetoric that might fuel mutual enmity, revenge, or branding an entire ethnic group as responsible for the crimes committed by a handful of its members (Fuller 2004).

The concerns and fears about retaliatory violence had foundation. Immediately after the hostage taking, anti-Ingush rallies were held by Ossetians in Prigorodny, a disputed district in North Ossetia that once was part of Ingushetia and had housed an Ingush majority. Police and Russian troops increased their presence to prevent the rallies from turning violent, and fearing retaliation, Ingush families began fleeing Prigorodny, and Ingush students left their North Ossetian universities (Sands 2004a; Weir 2004).

In a meeting in the gymnasium of the wrecked school, many victims insisted on vengeance:

“Let’s gather up all of the men in the villages and fight!”

“The people who don’t want to fight say, ‘So many innocent lives will suffer if we take up arms.’ Well, we’ve already suffered enough. It’s time to fight.”

“Of course, after the funerals our men will try to take matters into our hands. And of course, this is the right thing to do.”

“[T]his is the time to take up arms, because the blood that was spilled was ours. Who among us can just go home and live calmly?” (Rodriguez 2004a)

Almost a year later, prominent Russians continued to assert that provocation of interethnic violence was a prime motive for the hostage taking and that the provocation could have worked. Noted pediatrician and negotiator during the hostage taking, Dr. Leonid

Roshal, said, “What did [Chechen rebel leader Shamil] Basayev want to do? He wanted Ossetians to take spades and machine guns and move on to Ingushetia. If someone’s child is taken hostage, he may do this” (Official Kremlin International News Broadcast 2005).

In a focus group of male Beslan victims over thirty-five years old, participants were asked whether people had been thinking about taking revenge on the Ingush.

VITALY: Yes, some people were [thinking this way].

BORIS: In the beginning, there was such an opinion.

VITALY: Yes, it was a stressful situation.

TAMERLAN: People had this idea. You could even say the overwhelming majority of people . . .

KAZBEK: To tell the truth, if I had seen a full bus with Ingush people right after the events and there had been children there, I would have shot all of them. All of them.

ТOTRAZ: You are overreacting.

KAZBEK: I would have shot everybody there.

TOTRAZ: I don’t think you would have shot children.

ALIK: I can easily believe him.

KAZBEK: I would have shot because I saw in the hall, in the morgue. . . . I mean, I am talking about the first days after the events.

In a separate focus group, female victims remembered the same discussions and expectations of retaliatory violence.

ANGELA: At that time it was true [that there were attempts at revenge].

VERA: Well, consider the state everyone was in at that time.

VALYA: This desire originated in rage.

VERA: These were men who buried their children. I think not only an Ossetian but a Russian would also avenge his child.

VALYA: Everyone went there, not only Ossetians. At that time, everyone was in such a rage that they were ready for anything.

In response to whether people in 2008 still thought they should take revenge and even look for such an opportunity, the men answered:

BORIS: No one will tell you openly about it. Probably they do.

ALIK: No person will say that it is unnecessary, that it is senseless. If a person slapped you in the face once and you didn’t respond, the second time he will cut off your finger, and the third time your hand, and then in general . . .

KAZBEK: In the Bible it is one way, but in real life, it is another. Share your bread with your enemy. I will share dynamite with him.

Rumors circulated that at least some retaliatory violence materialized. Human rights activist Timur Aliyev claimed that only hours after the siege ended, Ossetians took a handful of Ingush hostages in the village of Chermen, twelve kilometers southeast of Beslan (McAllister and Quinn-Judge 2004), and some Beslan residents allegedly headed into Ingushetia and abducted ten Ingush men (Walsh 2004a). Later, in 2007, Suleiman Vagapov, deputy to presidential envoy to the Southern Federal District Dmitry Kozak, circulated a document describing a North Ossetian group that engaged in abductions as retaliation for the school hostage taking and claiming that 238 people went missing in North Ossetia, 26 of whom were Ingush. In 2006–2007, 25 Ossetians and 19 Chechens and Ingush were reportedly abducted (Fuller 2007). Also in 2007,

Lieutenant Colonel Alikhan Kalimatov of the Russian Federal Security Service was shot dead on the Caucasus highway in Ingushetia where he was investigating the kidnappings of ethnic Ingush in North Ossetia (“High-Ranking Security Officer” 2007).

There may have been other incidents of retaliatory violence. However, the bigger story of the Beslan aftermath is in how little retaliatory violence actually occurred, especially relative to expectations and relative to historical patterns in the North Caucasus. The September 2004 hostage taking did not initiate a new ethnic war or significantly escalate the level of violence in an already tense region. Importantly, most Beslan victims and their relatives, neighbors, and other co-ethnics opposed the idea of responding to violence with further violence.

As participants in a focus group of female victims under thirty-five years old explained:

IRINA: There were people who wanted it [revenge]. They were not a majority, but if they had felt support, they would have gone.

BELA: No, better a thin peace than a war.

Participants in a focus group of female victims over thirty-five years old also dismissed revenge as a viable option:

DINA: And did you want us to attack our neighbors?

BERTA: And on whom to take revenge now?

TATIANA: There is nobody.

BERTA: And slaughter—what do you mean? Ossetia will now get together and attack Ingush, Georgians? This is senseless.

RAISA: We are used to a fair trial. That’s all.

BERTA: And again there will be no result. And we need a result.

TATIANA: And we don’t need war.

BERTA: War is just bloodshed with no result.

TATIANA: Like here. Our children again.

BERTA: Children, young boys will be left without parents.

The men over thirty-five provided some details on the decision to avoid retaliatory violence:

ALIK: Literally a few days later, I don’t remember the date exactly, the most active young people gathered in our recreation center. And there was one question: What is to be done? Serious interrepublican problems may emerge. But as we have many clear heads, sensible ones—there were very many people there, and they decided that we would not take any active actions until we sorted out all our funerals, all this business. That is why it was quiet. I know what you mean: why didn’t you all take machineguns?

KAZBEK: Everybody was very emotional. So one small spark, and it would have been bad. Everybody understood that.

ALIK: God, help us to avoid an explosion between the two republics.

KAZBEK: Everybody had a say. We listened to everybody there. But most people were saying that it does not pay to do anything for the time being.

Unexpected Political Activism in Beslan

Instead, starting in September 2004, the town of Beslan, with its population of only 36,000, became the site of some of the most politically active of Russia’s 140 million citizens. Before the hostage taking, Beslan was unknown outside of Russia and rarely made the news even inside Russia. Beslan was far from any major power center, and its residents were not wealthy or powerful or more highly educated than other Russian citizens. There was little reason to predict the sustained activism that followed. Virtually overnight, thousands of Beslan residents began engaging in politics, with dozens becoming full-fledged activists for years to come. They held rallies at their House of Culture, central square, and other sites. They set up websites and organizations. They attended

town meetings, signed petitions, and met with local and national politicians and aggressively pursued them with demands. They blockaded a highway, staged a courtroom sit-in, went on a hunger strike, and carried out independent information-gathering in order to challenge the authorities. They traveled to Vladikavkaz, Rostov, and Moscow. They litigated, appealed to the international community, and filed a complaint in the European Court of Human Rights.

While observers and politicians in September 2004 and beyond were predicting retaliatory violence, few if any were predicting this outpouring of political activism. Certainly, no one was predicting the sheer size of the activist population, the diversity of the participatory acts, or the perseverance of many who continue to challenge the authorities even today. In the early aftermath, the number of participating individuals was remarkable: hundreds showed up for various rallies, and occasionally more than a thousand, in a town only thirty-six times as large. Victims describe these early events as spontaneous, with no clear leaders or official sources of information, just relatives and neighbors instinctively spreading the word to go. Even those who were just released from the hospital and who were, in the words of one victim, “half-dead, cut, and injured here and there and everywhere and could hardly move,” went to the rallies. Funerals too became a kind of rally, and for some two months afterward while the entire town buried their loved ones, the politicized crowds retained their momentum.

By then, Beslan residents were emboldened, with many willing to vocalize their grievances in public settings where they could be individually identified by authorities. For example, at 3 p.m. on November 3, 2004, just two months after the hostage taking, more than a thousand residents gathered at the House of Culture to meet with an official delegation headed by Russian Deputy Prosecutor General for the Southern Federal District, Nikolai Shepel, and including the former mayor of Beslan and other officials. Shepel informed the crowd that there had been thirty-two terrorists, that the terrorists had been using drugs, that there were no weapons planted in the school in advance, that the terrorists brought the weapons with them, and that legal action had been taken against