The Library of Paradise

A History of Contemplative Reading in the Monasteries of the Church of the East

DAVID A. MICHELSON

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© David A. Michelson 2022

The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022937769

ISBN 978–0–19–883624–7

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198836247.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

To Bethany, my wife of more than two decades. Loving me has meant living half your life in a library. Loving you has meant living half my life one step closer to Paradise. Thank you for making this book and so many more important things possible. I love you.

I place my trust in the mercy of our Lord that He will give strength to my weakness, and that I shall endure.1

ʿEnanishoʿ of Adiabene, Paradise

1 ʿEnanishoʿ of Adiabene, Paradise, pt. II/24; translated in E. A. Wallis Budge, ed., The Book of Paradise, Being the Histories and Sayings of the Monks and Ascetics of the Egyptian Desert : Volume I English Translation, trans. E.A. Wallis Budge, vol. 1 (London: Printed for Lady Meux by W. Drugulin, Oriental Printer, Leipzig, 1904), 381 [numbered Pa II/19 in the 1904 edition].

Acknowledgments

We books are many, but there is no one who reads in us. Behold, what a great pity that we remain useless!1

—Annotation left by a medieval Syriac reader

Some of the first inklings of this project came during 2004–5 when I spent time with the Syriac manuscripts in the Asian & African Studies Reading Room of the British Library in London. I remain deeply grateful to those who welcomed me there. I am specifically thankful to the former curator, Rev. Dr. Vrej Nersessian, whose staff were always courteous and professional to the readers even during the most unexpected of moments, such as when the 7/7 terrorist attacks forced them to confine us with the books in the library for safety. I am glad that the collection continues to be well curated today under the care of Ilana Tahan who has been a leader in making the Hebrew manuscripts of the British Library accessible digitally around the globe. May the Syriac manuscripts of the British Library soon find new readers in the same way.

Initial research on this project was sparked by reading the warnings issued by the eighth-century East Syrian author Joseph Hazzaya about the brain damage which could occur from too much reading.2 As someone who is blessed or cursed to read for a living, I was curious to understand the full context of those ascetic warnings. As I pursued research on this project, I became increasingly aware of the work of a small number of scholars who have studied the place of books, reading, and exegesis in the history of the Church of the East. My book would not have been possible without relying on these studies, especially the works of Sabino Chialà, Muriel Debié, the late Mary Hansbury (may she rest in peace), and Joel Walker. These publications have done much to make East Syrian exegesis and East Syrian mysticism accessible to the scholarly public.

1 London, British Library, MS Add. 12,170, f. 135r. Sebastian Brock calls attention to this note in Sebastian P. Brock, “The Development of Syriac Studies,” in The Edward Hincks Bicentenary Lectures, ed. K.J. Cathcart (Dublin: University College Dublin, 1994), 102–3. My translation is from the text in William Wright, Catalogue of Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum, Acquired since the Year 1838: Part II, vol. 2, 3 vols. (London: British Museum, 1871), 460. Caveat lector! This marginalium may be more poignant than true, since it is ipso facto evidence of at least one reader. See the discussion of such tropes in Section 2.1.1.

2 See Joseph Hazzaya, Letter on the Three Stages of the Monastic Life, chap III sec. 68; edited and translated in Paul Harb, François Graffin, and Micheline Albert, eds., Joseph Hazzāyā: lettre sur les trois étapes de la vie monastique, trans. Paul Harb, François Graffin, and Micheline Albert, Patrologia Orientalis, 45.2 [No. 202] (Turnhout: Brepols, 1992), 338.

Many academic colleagues have supported and encouraged me in this project as it incubated. I am grateful to Peter Brown for his friendship and encouragement to always wonder what ancient readers were seeking. I am thankful for Bob Kitchen, who—along with Peter—never stopped asking about when this book would appear, even when the pandemic of 2020 delayed me in my final revisions. Adam Becker, Mary Hansbury, Kathy Gaca, and my parents Paul and Jean Michelson also took time to read the whole manuscript and offer advice. JeanneNicole Mellon Saint-Laurent and Daniel L. Schwartz were my frequent traveling companions among Syriac texts and constantly encouraged me in writing this book—thank you! A number of other colleagues have also put up with my questions related to my pursuit of lectio divina, Syriac readers, and helped me get access to copies of manuscripts. Thank you to Chris Brady, Sebastian Brock, Thomas Carlson, Dawn Childress, Stephen Davis, Muriel Debié, Mark Dickens, Nathan Gibson, Kristian Heal, Christopher Johnson, Joel Kalvesmaki, George Kiraz, Grigory Kessel, Jonathan Loopstra, Adrian Pirtea, Matteo Poiani, Gerard Rouwhorst, Tina Shepardson, Columba Stewart, Jack Tannous, David Thornton, Cynthia Villagomez, Joel Walker, and James Walters. These scholars only caught glimpses of the project at various stages, so any “mis-readings” are my own—of course—not theirs.

Encouraging colleagues at Vanderbilt University also provided key feedback. Students in my seminars read and commented on some portions. Jay Geller was always ready to be interrupted to help me see the value of our work as something more than merely a glass bead game. He was always read-y with puns related to my work. Juan Floyd-Thomas graciously commented on a chapter that strayed into his domain of expertise. Jim Hudnut-Beumler offered thoughts on the general structure of the project at an inchoate point in its formation. Annalisa Azzoni, Paul DeHart, Kathy Gaca, Jaco Hamman, Trudy Hawkins-Stringer, Robin Jensen, Amy-Jill Levine, Paul Lim, Vicki Matson, Bruce Morrill, Joe Rife, Jack Sasson, Choon-Leong Seow, Phillis Sheppard, and Melissa Snarr offered encouragement at moments when it was needed.

One portion of this book, the first half of Chapter 2, was previously published as an article in a special issue of The Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture.3 I appreciate the assistance of the editor-in-chief of the journal, Tim Hutchings, in granting me permission to reuse and revise a portion of that article as part of its open access publication policy. I am also obliged to Claire Clivaz, Paul Dilley, and the other special issue editors for their feedback and for those which they relayed from the anonymous reviewers. An early draft of this same chapter was also presented to the Overlook Seminar of the Religious Studies

3 David A. Michelson, “Mixed Up by Time and Chance? Using Digital Methods to ‘Re-Orient’ the Syriac Religious Literature of Late Antiquity,” The Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 5, no. 1 (2016): 136–82.

Department at Vanderbilt University. Phil Liebermann, Bryan Lowe, Samira Sheikh, and Tony Stewart among others gave me lively feedback.

Narrow sections of the book have appeared as papers at two conferences, one hosted by the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale University and the other jointly sponsored by the History Department at the University of Alabama and the Research Centre for the Comparative History of Religious Orders of the Technische Universität Dresden. I am honored that Professors Peter Jeffery and Henry Parkes invited me to present my work-in-progress at Yale. I am grateful to Professors Gert Melville and James Mixson for their invitation and for publishing material related to Chapters 6 and 7 in Virtuosos of Faith: Monks, Nuns, Canons, and Friars as Elites of Medieval Culture (Zürich: LIT Verlag, 2020).4 I am pleased that LIT Verlag allowed me permission to reuse some prose from that chapter in this book.

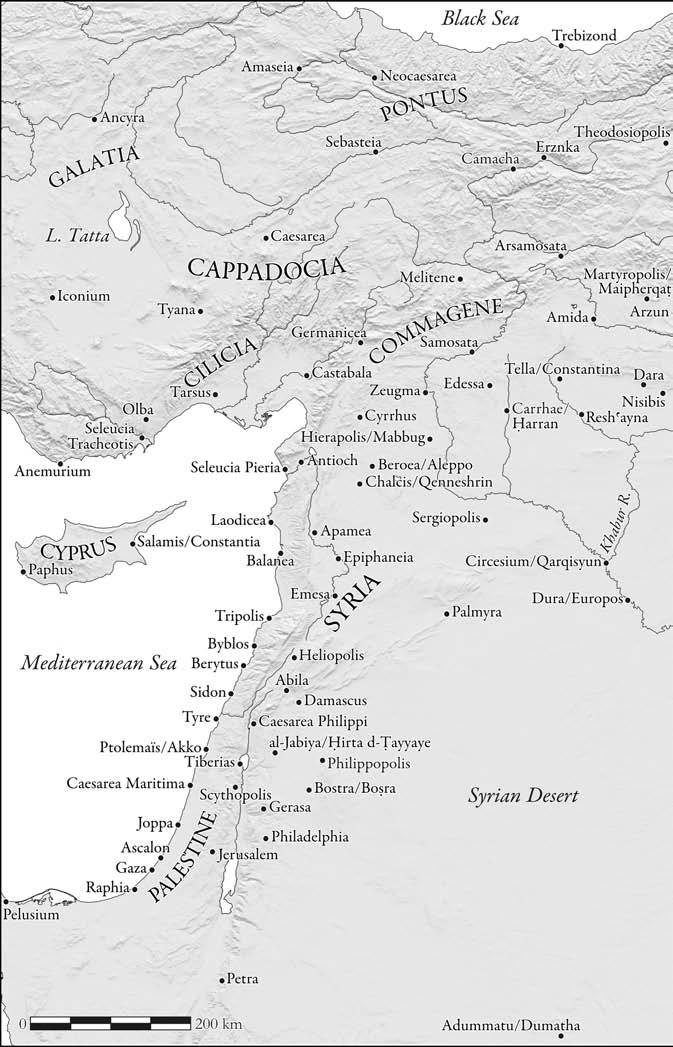

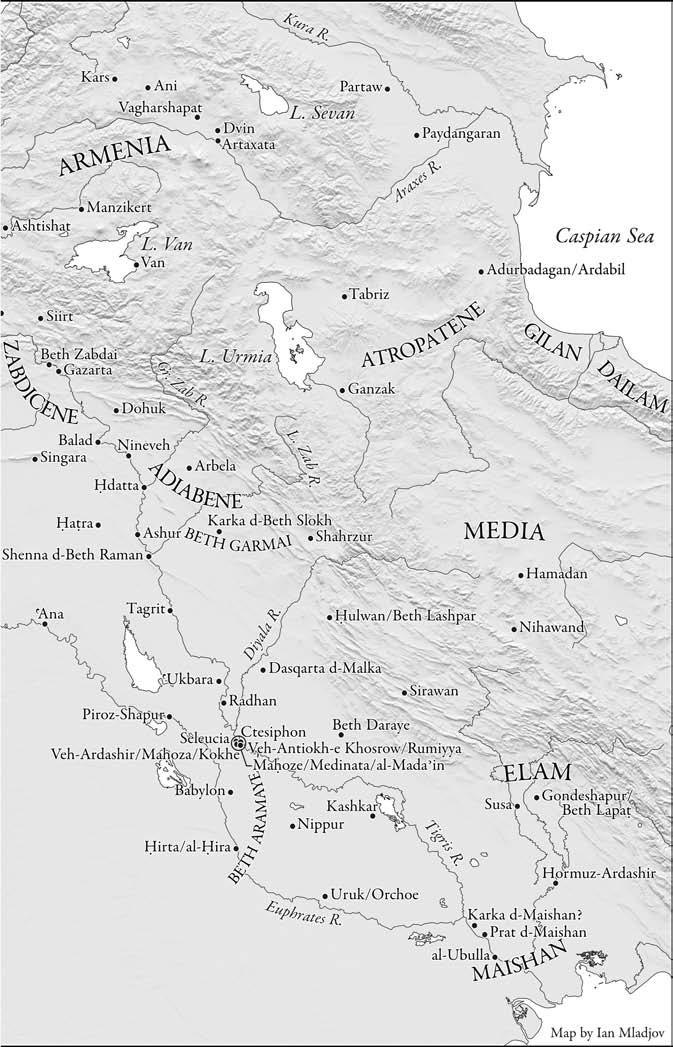

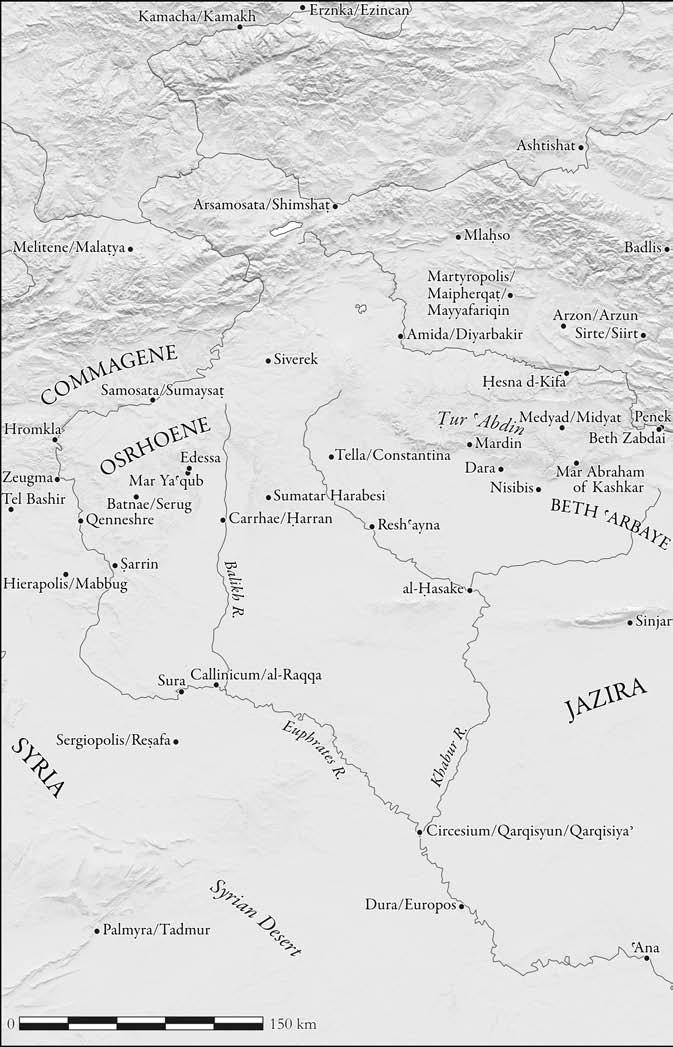

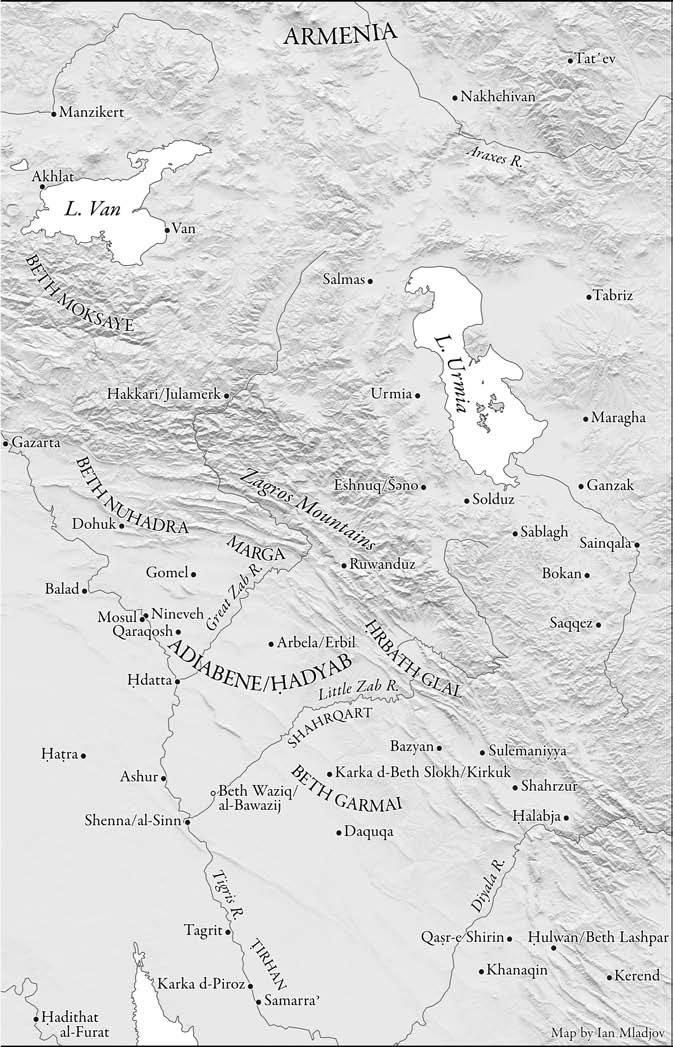

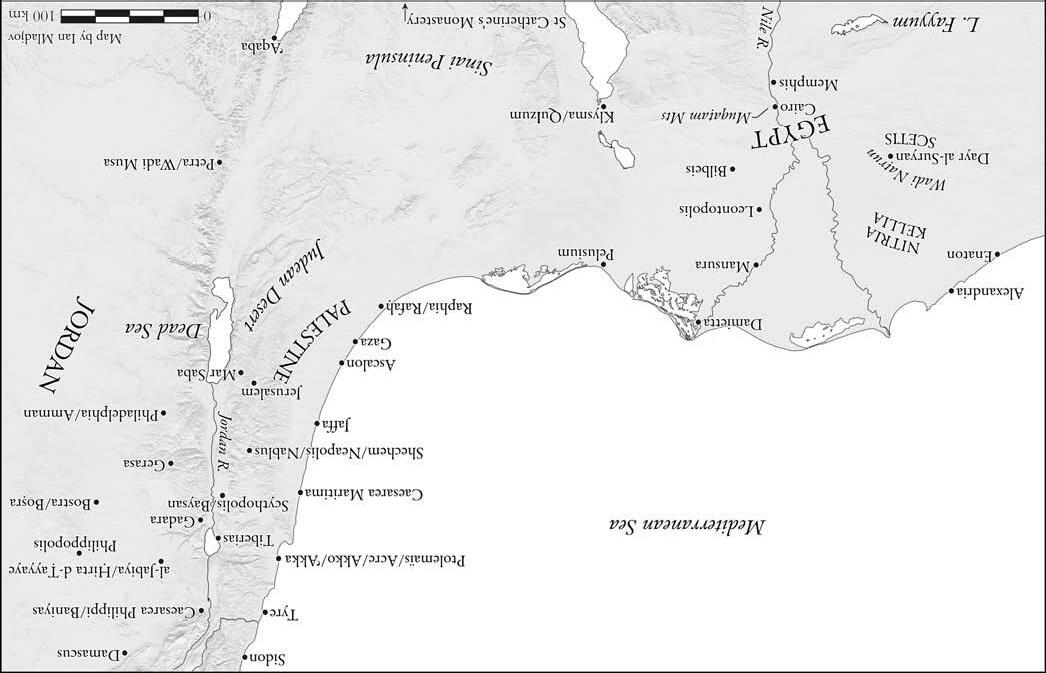

In addition, I presented very preliminary research at three conferences in 2015: a panel at the North American Syriac Symposium hosted by the Catholic University of America, a session of the Syriac Literature and Interpretations of Sacred Texts unit at the Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting in Atlanta, and a workshop held by the Regional Late Antiquity Consortium Southeast (ReLACS) at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. I am grateful to the many colleagues who offered comments on those occasions including Dina Boero, Phil Forness, Gregor Kalas, Cornelia Horn, Peter Martens, and Erin Walsh. I originally published the maps used in this book in The Syriac World, edited by Daniel King.5 To further the growth of Syriac studies, my co-author Ian Mladjov and I have made these maps available for reuse through the Vanderbilt University Institutional Repository at the following persistent link: http://hdl.handle. net/1803/16426. The maps are copyright 2017 by David A. Michelson and Ian Mladjov and reused under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Further reuse of these maps is encouraged.

The final draft of this book has benefitted greatly from the editorial assistance of Oxford University Press and the work of Andrew Louth, Tom Perridge, Karen Raith, and Cathryn Steele. The suggestions of the anonymous reviewer allowed me to trim the book and sharpen its argument. Thank you to copy editor Brian North for making my prose better than I could have on my own and to Saraswathi Rajan and the whole production team for negotiating the challenges of Syriac

4 David A. Michelson, “The Hidden Excellence of Lectio Divina: The Ambiguities of Reading as an Elite Marker in East Syrian Monasticism of the Sixth and Seventh Centuries,” in Virtuosos of Faith: Monks, Nuns, Canons, and Friars as Elites of Medieval Culture, ed. Gert Melville and James D. Mixson (Zürich: LIT Verlag, 2020), 285–302.

5 David A. Michelson and Ian Mladjov, “Diachronic Maps of Syriac Cultures and Their Geographic Contexts,” in The Syriac World, ed. Daniel King (New York: Routledge, 2019), xxvii–xxxiii and maps 1–14.

Unicode characters. David Calabro, Curator of Eastern Christian and Islamic Manuscripts at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library suggested the cover image of Elijah and Enoch in Paradise with the Tree of Life, an illustration of the Anathema of Paradise found in Congregation of the Chaldean Daughters of Mary Immaculate MS 18, folios 8v–9r.6 I am grateful to the Centre Numérique des Manuscrits Orientaux (CNMO), Ankawa, Iraq and the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library for permission to use the image. While the Anathema of Paradise perhaps dates to a millennium later than the focus of my study, this manuscript bears witness to the enduring fruitfulness of both Paradise and books as theological motifs in the later East Syrian traditions. The other image reproduced in this book is an opening fragment with a faded rubric from a Sogdian translation of Dadishoʿ of Qatar’s Commentary on the Paradise found in the Christian Sogdian MS E28 (Fragment E28/8c Recto n208) now held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. I am grateful to the Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften for permission to use it here.

While an author may not live on “bread alone”, material and financial support was nevertheless key in the preparation of the book. Sabbatical funding from the Research Scholar Grant program of the Office of the Provost at Vanderbilt University made it possible for me to take a year-long research leave to write the book. Similarly, research leave and funding from Dean Emilie Townes of Vanderbilt’s Divinity School was essential to the completion of this monograph. When I was in the depths of writing seclusion, a number of faculty colleagues including Ari Bryan, Kathy Gaca, Joe Rife, and Betsey Robinson made Cohen Hall a Paradise where I knew I could find fruitful interlocutors or else the peace and isolation to read as needed. Many Vanderbilt staff members provided material assistance such as printing pdfs of Syriac manuscripts, upgrading computers, or signing for book deliveries, including Donald Grubb, Julia Kamasz (and Luna!), Heather Lee (you are always anticipating things before I need them), Tyrone Mallett, Ela May, Marie McEntire, Matthew McGlasson, Shelby Merritt, Judy Peterson, Fay Renardson, and Drew Scott.

This study of reading required a good deal of reading in its preparation. My work as a reader was supported by the selfless work of dedicated research assistants who travailed away thanklessly entering bibliographic items into Zotero, fetching ILL items, or tracking down obscure references in Revue de l’Orient Chrétien. Ed Gray, Sarah Porter, Justin Arnwine, and Julia Nations-Quiroz provided research assistance before I was even sure what form the book would take. Elizabeth Lefavour also assisted with ILL queries. Thank you all for helping me read widely and quickly. Stephanie Fulbright, Julia Liden, Will Potter, Lindsay Ruth, and Roman Brașoveanu helped bring the book to completion.

6 ʿAynkāwah, Iraq, Congregation of the Chaldean Daughters of Mary Immaculate, MS 18, https:// w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/500460.

Libby and Wills Michelson checked the footnotes for punctuation. During one academic year, Stephanie and Julia were collectively responsible for submitting one out of every seven interlibrary loan requests filled across the entire university. Julia and Will provided key copy editing on short deadlines. Will, your knowledge of Chicago Manual of Style should qualify you to be the editor of the next edition! Thank you to all of you—this book would not have been possible without your essential collaboration. May you all continue to find Paradise through reading.

The staff of the Jean and Alexander Heard Library at Vanderbilt were essential to my completion of this project. Jim Toplon, Rachel Adams, and Robyn Weisman have perhaps never encountered a more delinquent or voracious ILL patron, yet were always gracious and efficient. Chris Benda, Bill Hook, Keegan Osinski, and Bobby Smiley also surpassed my expectations for purchasing new Syriac materials in the Divinity Library which made my work easier. Cliff Anderson put up with sundry requests even though I often refused to return his favors since I was “on leave”. Thanks for making our own Vanderbilt library a little Paradise.

A number of Syriac scholars and members of the Hugoye discussion forum also provided copies of hard to find items. In particular, I am grateful to Bishop Mar Awa Royel of the Assyrian Church of the East for providing me a copy of the current version of the Hudra which is still in use in his tradition.

Besides the many academic colleagues and staff who provided material support for the project, I want to thank those friends who saw the spiritual value of the project. Manuel, Dan, Yuri, Aaron, Ben, Andy, Brent, Ryon, Matthew, Morgan, and other actual practitioners of lectio divina supported me with prayer, reading, and a reminder that ancient spiritual practices might remain valuable today. Susan Thrasher provided a suitably remote location ideal for revising the book manuscript. Other friends were willing to risk a grumpy reply and ask if I had yet found my way out of the Library of Paradise, especially Bill Brewbaker, Walter Bodine, Tammy and Steve Casey, David Cassidy, Beth Cruz, Don Paul and Ginger Gross, Fr. Travis Hines, Elizabeth and John Kea, Rachel and Aaron Kelly, Cor-inne Michel, Jade Novak, Sherry Paige, Russ Parham, Tammy and Charley Petit, Seth and Miriam Swihart, Matt Webb, and Fr. Sammy Wood. Brady Henson belongs in a superhero category for his encouragement.

I also want to thank my family for sacrificing their time and my presence for this book. My parents, Paul and Jean Michelson, taught me long ago the joys of libraries, from the half-floor stacks in Urbana-Champaign to the warren-like studies of scholars in București, to the familiar library at 1632 Station Road. Thank you—and pace Borges and Hesse—for teaching me that the actual Paradise is nothing like a library. Thank you as well to Sharry, Paco, Hee-Eun, Tirzah, and Matt for encouraging Bethany as I wrote. I would choose family over books any day (or at least on my best days). Most of all, to my Bethany, Simeon, Joel, Anna, Libby, and Wills: Thank you! May reading and praying always lead you to know

and love the Word who though he was beyond all words became flesh on our behalf.

As an invocation for this book, I can do no better than to join with prayer of Thomas of Marga: “I ask our Lord, through the prayers of Mar Abraham and of the children of his holiness that I may hear and relate His glories; that I may speak of His glories in His saints . . . so that by the author and the scribe, and by the reader and the listener, and by the confessor and the faithful may be woven a cord of glories for His holy name for ever and ever.”7

David A. Michelson

The Feast of Denha, 2022

7 Thomas of Marga, The Book of Governors, I:2; edited in E.A. Wallis Budge, ed., The Book of Governors: The Historia Monastica of Thomas Bishop of Margâ A.D. 840: The Syriac Text, Introduction, Etc., vol. 1 (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1893), 20; translation adapted from E.A. Wallis Budge, trans., The Book of Governors: The Historia Monastica of Thomas Bishop of Margâ A.D. 840: The English Translation, vol. 2 (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1893), 24–5.

Permissions

Text and Romanizations

List of Figures

List of Abbreviations xxiii

Maps xxiv

I. METHODOLOGY

1. Introduction: Framing Questions for the Study of Contemplative Reading in the Church of the East 3

2. Manuscripts without Readers? Perspectival Obstacles to the Study of Syriac Ascetic Reading 15

3. Was There a Syriac Lectio Divina? Models and Definitions for the Study of Contemplative Reading in the Church of the East in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries 44

II. NARRATIVE

4. Contemplative Reading on the Banks of the Euphrates: The Establishment of a Tradition from Ephrem the Syrian to Abraham of Kashkar 73

5. “Cloak, Tunic, Book, Cell”: Reading Evagrius in Syriac with Babai the Great 134

6. “Dense with Every Kind of Fruit”: ʿEnanishoʿ of Adiabene, Dadishoʿ of Qatar, and the Harvest of East Syrian Contemplative Reading 187

7. Conclusions: Trajectories and Legacies of East Syrian Contemplative Reading