Acknowledgements

This book began with my being surprised (or as Mary Poppins would describe it, as having a ‘cod fish’ reaction) in 2012, when I encountered several travelling ayahs in archival records, particularly in ship passenger records which listed them as passengers travelling between Asia and Britain. At that time, I was a graduate student on my very first trip to the archives in the UK. While I worked on my PhD and then my first book, Fleeting Agencies: A Social History of Indian Coolie Women in British Malaya, I continued working on these incredible women—the travelling ayahs. Since then, this curiosity has been encouraged, nurtured, and supported by many scholars, archivists, colleagues, friends, and my family.

The manuscript has been enriched by the detailed and insightful comments from three anonymous reviewers. My sincere thanks to them and Cathryn Steele, Editor of Oxford University Press. Cathryn, special thanks are due to you for always being so kind, supportive, and for constantly mentoring me through the process. You have been a dream to work with and I truly hope other authors are lucky to have the editorial experience I had.

I owe a lot to the incredible generosity of scholars, friends, and mentors who have supported this project in reading earlier drafts of the chapters, related papers, and/or in being my sounding boards for my draft ideas for this book. For all this and more, special thanks are due to Antoinette Burton, Barbara Andaya, Catherine Hoyser, Daniel Grey, Erika Rappaport, Indrani Chatterjee, Jonathan Saha, Kelvin Low, Laura Tabili, Louise Williams, Megha Amrith, Siddharthan Maunaguru, Sumita Mukherjee, Sunil Amrith, Susan Grayzel, Tammy Proctor and Vineeta Sinha.

I am particularly grateful to Kelvin Low, Siddharthan Maunaguru, and Vineeta Sinha, who patiently heard my new finds in archives when this project was just beginning and always were generous with their time and support whenever I wanted to discuss ideas and arguments about this project. Special thanks are due to Antoinette Burton for inspiring me to think about the resilience of the travelling ayahs while they were stranded and how they used different loopholes of the colonial administrative system to their advantage. A special thank you is also due to Susan Greyzel and Tammy Proctor for inspiring me to write a chapter on travelling ayahs during the war. The questions they asked me at a conference and the follow-up discussions helped me formulate Chapter 5 in this book.

No academic journey nor a book is complete without friends in academia who are always just a chat away when you feel stuck. Special thanks are due to Elaine Farrell, Allison Edgren Laura Seddlemeyer, and Gordon Ramsey. You were always there to make time for me and listen to my wild ideas about the book and give me mentoring

and courage to carry on. You read my work patiently and made comments—even if it meant hearing/reading the same case for the fifth time. Elaine, thank you for being such a good influence on my work and always suggesting a ‘way out’ whenever I felt stuck and needed more ideas. Thank you especially for all the chats regarding the profiles section. Gordon, without your careful reading and commenting this book would be incomplete. Allison and Laura, thank you for always being a call away and inspiring me with ‘tomorrow is another day’ whenever I felt stuck.

A historian’s book is impossible without the expertise and support of archival experts. I owe special thanks to the staff of the APAC Reading Room, Imaging Services at British Library, some of whom through all these years have become almost my extended family—Aliki-Anastasia Arkomani, Annabelle Gallop, Arlene C. B., Charles Bonnah, Gary Carter, Haque Sarker, Jay, Jeff Kattenhorn, John Chignoli (Chop Chop), John O’Brien, Jonathan Vines, Lorena Garcia (Guapa), Marie Lewis, Richard Bingle, Richard Morel, Robert Boyling, and Sita Gunasingham. I am also indebted to the staff of the National Archives of India, West Bengal State Archives, National Archives of Malaysia, the National Archives of UK, the London City Mission Archives, the British Newspapers Archives, Hackney Archives, the National Maritime Museum of UK, and the National Army Museum of UK.

I also thank the various conference organizers and panelists I met between 2014 and 2021 who have given me the incredible opportunity to share my research and whose insightful comments have helped me develop my arguments. Your time, comments, and suggestions were extremely valuable. Special thanks are also owed to Cailee Cunningham for patiently helping me with several design aspects of the project.

A few chapters are revised and much longer versions of the following articles: ‘Responses to Traveling Indian Ayahs in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Britain’, Journal of Historical Geography; ‘Stranded: How Travelling Indian Ayahs Negotiated War and Abandonment in Europe’, Indian Journal of Gender Studies. I owe grateful acknowledgement to the journals and publishers for allowing me to build on this earlier work.

Several funding agencies and organizations have supported the research and writing of this book. A post-doctoral fellowship at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore (2016–18), a National Endowments Endowment for Humanities Sponsored Grant through the Idaho Humanities Council (2020–1), and Idaho State University’s College of Arts and Letters’ Course Release Award (Spring 2022).

I would also like to acknowledge with gratitude the love and support I have received from Jonathan Fardy, Amy Wuest, Elijah Wiley Wuest, Raghava Kondepudy (Raghav Bhaiya), Mira Kondepudy, Riya Kondepudy, and Xiaoyang (Stella) Kondepudy during the writing of this book over the past few years. Thank

you for being my family and home away from home. Thank you for patiently listening to all my challenges and giving me the courage to go on.

I am grateful for my parents, Rumjhum and Debasish Datta, who always found the right words, the right actions, and the right emotions to support me from near and far and helped me carry on. Whenever I felt ‘stuck’ you both inspired me to keep going. Mimi and Papa, without you this book would not have been possible. I can never thank you enough for the invisible labour you provided not only in forms of emotions but also in taking time to carefully read those illegible handwritings from archival records just to help me figure out what one word was, the hours you spent listening to me going on and on about the travelling ayahs and sometimes even raised questions about why was Martha or Mary or Nasiban (ayahs) not mentioned in one chapter but in another. You painstakingly proofread my chapters even if it meant foregoing some of your other plans. For everything and for always being by my side—thank you!

My heartfelt thanks to Shiladitya Mukherjee (Adi), my husband, who always kept reminding me in the power of words and stories and how the smallest stories of the travelling ayahs were worthy to mention in the book because they had the ability to put the readers in the shoes of these incredible women. Many times, when I as an author felt vulnerable to the missing links and silences in those stories, Adi always gave me courage to lay bare where the silences were and show the readers the vulnerability of the past. Adi, it’s really hard to express how grateful I would ever remain for your constant support in this arduous journey. Finally, to all the travelling ayahs of the past and mobile caregivers of the present day, thank you for being an inspiration. This book is for you!

Preface

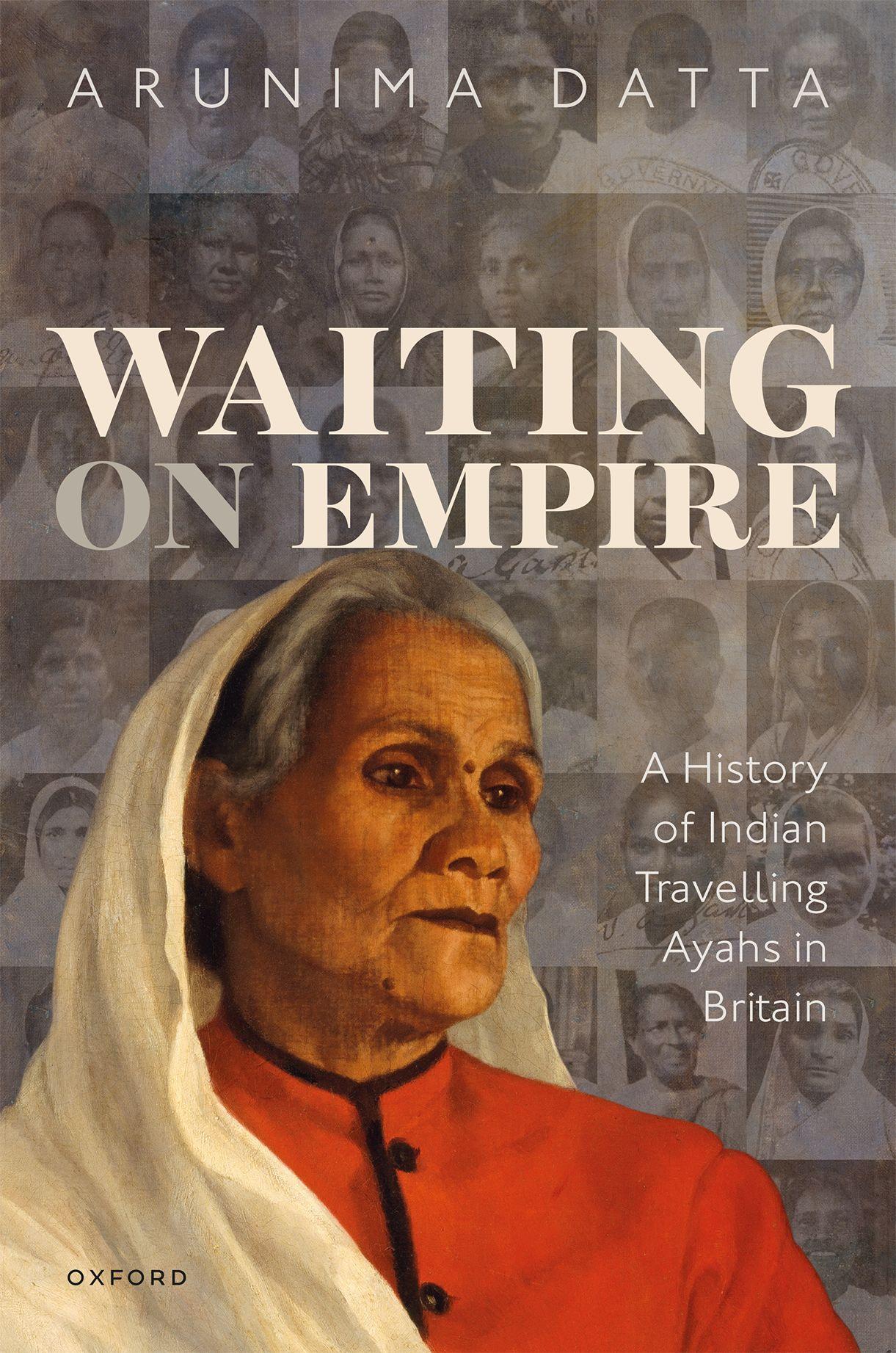

India’s travelling ayahs were once a familiar part of the British Empire, providing childcare and other domestic services for the families of the British privileged class as they voyaged between India, Britain, and further-flung imperial realms. Life could not have been easy for these women, many of whom had left their homes for the first time to care for strangers in unfamiliar waters and lands, making journeys comfortable for their patrons whilst overcoming their own seasickness and fears. Today, travelling ayahs are largely forgotten: one of many groups of migrant workers in the history of the British Empire whose voices have been silenced if not erased. Their experiences and identities have seldom been the focus of archival records and have largely faded from social memory. Yet for close to two centuries, they were a vital part of the infrastructure of the Empire, their labour enabling the mobility of thousands of families in the globalized world in which they played a part in creating and in which they participated. Although their individual identities are often obscured, nevertheless signs of their activities are visible in archival records—even if only in the margins of such records. It is from these archives, documents produced long ago through the routine activities of shipping clerks, border controllers, imperial administrators, businesses, legislators, and employers that I have sought to unearth their story.

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a historian is going into longneglected archives and disappearing into historical rabbit holes, which often lead to new and exciting research paths. In 2012 while doing archival research in Arkib Negara in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for my dissertation on Indian coolie women in British Malaya, I stumbled on a Labour Department file which discussed how an aged coolie woman could easily be employed as an ayah (a nanny) for a planter’s children.1 The image of an old coolie woman who could no longer accurately tap rubber trees, whose hands were probably rough from carrying pails of latex and handling knives for weeding and tapping, suddenly becoming an eligible recruit as a caregiver for the delicate body of a planter’s child—the future of the British Empire—lodged itself in my mind. Later the same year, researching the records of the India Office in the British Library in London, I came across a political and judicial file that documented the story of an Indian ayah who was brought to Malaya by a planter family and then taken to Britain

1 Although the term ‘coolie’ is sometimes seen as derogatory, veterans of the Malayan plantations whom I interviewed were proud to call themselves coolies, and in my publications I therefore use the term without quotation marks.

during the family’s summer leave. Subsequently, the ayah had been abandoned in London and her case came to the attention of the India Office. The correspondence suggested that such desertion of travelling ayahs by their employers had become alarmingly common in Britain during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Later during the same research trip, I found hundreds of passenger records in the archives revealing how common the profession was. This find intrigued me. The figure of the nanny or domestic servants in the British and broader Western imagination has tended to be dominated by Disney’s Mary Poppins or Downton Abbey, respectively. The fact, that many British middle- and upper-class children were raised and cared for largely by women of colour, was not part of this image. As I continued my research on coolie women on Malayan plantations, I also collected all records I came across that mentioned travelling ayahs or in some cases travelling servants.

By the end of 2012, I was torn between my research on coolie women and my new interest in travelling ayahs. A part of me wanted to simultaneously write about both communities of extraordinary South Asian women migrant workers, but that was not possible. When I discussed this with one of my mentors, Vineeta Sinha, she gave me the courage to focus my research on coolie women while suggesting that I should view the material on travelling ayahs as a second book in the making. Following her advice, I actively continued to collect and reflect on the voices of the travelling ayahs which I encountered in the archives, while being grateful to my mentor that she had confidence I could produce a second book when I was still unsure whether I would ever finish the first.

Between 2012–17, during my annual research visits to London, I attempted to embody the experience of the travelling ayahs in the city. I walked the same streets they would have walked to get from the dockyards to the Ayahs’ Home in Hackney;2 I visited the London City Mission where many would have attended Sunday prayers and visited the various addresses of the employers of travelling ayahs that emerged from the archival files. On one of my many jaunts to the dockyards in 2014, I ended up in the Museum of the London Docklands. The museum did present material on ‘lascars’ (Indian seafarers of the imperial era), but had nothing to say about travelling ayahs, although they must have been a frequent sight, coming and going from the London docks. I took this silence as a sign that the story of travelling ayahs was long overdue for the telling.

Carolyn Steedman has observed that a historian frequently experiences ‘archival fever’ long after leaving the archives. I was no different. The stories of the travelling ayahs kept me awake, wondering about their lives, their emotions, and their voices. But I experienced this archival fever in different ways in different spaces. While in the UK I constantly found myself attempting to re-visit,

2 Ayahs’ Home was a typical lodging and service brokering place, which housed travelling ayahs in London. This is the focus of Chapter 5 in this book.

re-walk the roads and places the travelling ayahs frequented, in India I encountered travelling ayahs in a different way. Travelling through the streets of Kolkata during my time carrying out research in the West Bengal State Archives, I frequently came across advertisements by ‘ayahs’ seeking employment, making me realize that the profession had not been consigned to the colonial past, but was still a way of life and a living for many Indian women, especially in India.

Some advertisements in present-day Kolkata, primarily pasted on the walls of hospitals and pharmacies (Fig. 1), specifically offered caregiving to patients, whilst others offered care services for the elderly and children (Fig. 2). These advertisements were very similar to advertisements I found in the archives that were circulated in Britain by travelling ayahs seeking employment on passages back to India. The only difference was that most ayahs in present-day Kolkata were not always travelling ayahs.

Looking at the first kind of advertisement, offering care for medically challenged individuals, I noticed that although some advertisements offered both nurses and ayahs, there was a care and wage hierarchy here. A nurse was a

Source: Author’s photograph

Translation: “Florence Nurse Center / For Ayah and Nurse contact / Mobile: 9874392628”

Fig. 1 Advertisements offering the services of Ayahs on hospital walls in Kolkata

Source: Author’s photograph

Translation: “Arogya Ayah Center / Ayahs available for child care, babysitting, caring for new born babies, caring for physically ill. / Available for 12 hours, 24 hours slots / Contact: 9836847191 8017935217 / 13/9 Dr. Neelmani Sarkar Street, Kolkata 700090”

professionally trained medical caregiver, but the ayahs in these advertisements were caregivers without formal qualifications who offered feeding, cleaning, and general care for the patients. Hence, they ranked lower in the professional hierarchy of caregiving, making them more akin to servants than nurses. The advertisements were a constant reminder of how capitalist languages and structures of work which were introduced during the colonial era remain part of everyday lives across the globe.

The second kind of ayahs’ advertisement in Kolkata offered caregiving services for the elderly and children. In a country where old peoples’ homes are still taboo and hospices are not well established, family members often hire ayahs to take responsibility of caring for elderly family members. Ayahs are also hired by nuclear families who prefer not to, or don’t have the means to, send their children to day care centres, which have only recently appeared in cities in developing countries such as Kolkata in India.

Even in our present-day world, however, we find domestic servants who travel, albeit serving under different names and different contexts. In 2014, during the controversial Devyani Khobragade trials in the US, I was struck by a different

Fig. 2 Advertisements pasted on various market streets in Kolkata

kind of archival fever. Khobragade was an Indian diplomat accused of fraudulently securing a visa for Sangeeta Richard, her domestic servant, whom she then paid less than the minimum wage, leading Richard to flee her house. In many ways, I witnessed the challenges faced by travelling ayahs being played out in the twenty-first century. Whilst many academic colleagues were struck by the details of the case, to me it seemed much like many of the cases I had examined in archives dating from a century ago: this was the past being played out in the present. Yet again I was reminded of the importance of the historian’s role: to remind society that without the past we remain prisoners of the present. This incident re-affirmed to me that the stories of travelling ayahs needed to be brought to the fore to historicize the experience of migrant domestic and caregiving work.

Waiting on Empire: South Asian Travelling Ayahs in Britain brings this muchneeded and long-overdue focus to travelling ayahs. The work of these women was vital to the Empire’s everyday functioning, but serving the Empire in the globalized environment it had created also transformed the consciousness of the travelling ayahs as they moved from margin to centre and back again, learning along the way to assert their rights and negotiate their positions in interaction with the colonial employers and imperial administrators in which the power of the Empire was embodied. In the pages that follow, I explore how travelling ayahs—women migrant caregivers in the empire’s metropole—engaged with various hierarchies in Britain: through emotions, through discourses, through materialist transactions, through religion, and more.

During my research for this book, I was constantly struck by a contrast between the way I encountered travelling ayahs and the way I encountered coolie women in the archives. Whilst both groups of migrant women workers were marginalized and were never the focus of the archives, the presence of travelling ayahs was, nevertheless, considerably more visible than that of coolie women. The names, faces, and other personal information about travelling ayahs could often be found in archives, unlike those of coolie women who, as a commodified mass labour force, usually only appeared as statistics. A key factor that made the travelling ayahs more visible was the fact that they frequently travelled with colonial families and were intimately involved in their caregiving. This personal engagement with the dominant class not only made travelling ayahs more visible than coolies at the time, but made the imperial surveillance of these mobile bodies more crucial and thus rendered them more visible to historians.

In its geographical focus, Waiting on Empire is a departure from my earlier work, which focused on South and Southeast Asia, specifically inter-Asian connected histories under the British Empire. However, the unwavering focus on migrant South Asian women workers within the context of the British Empire connects this book to my previous monograph. I turned to this work in an attempt to make an intervention following widespread anthropological discussions about contemporary migrant labour (especially from South and Southeast Asia) and

Preface

their experiences in the ‘West’. Waiting on Empire aims to open a window into the longer history of Asian migrant women’s caregiving work, the role of these women in facilitating connections and mobilities within the British Empire, and the ways they asserted agency in making lives for themselves within the imperial context. The concept of ‘waiting’ is the lens through which I examine these issues.3

This book argues that waiting is a space and, for marginalized women, it could be a space of precarity and vulnerability. Yet waiting also had the potential to offer a myriad of opportunities for those who waited and those who engaged with them. In other words, waiting offered not just trepidation but also hope. Whilst waiting has sometimes been theorized as being characterized by ‘stuckedness’,4 the focus in this work is on waiting as a site and process of activity. Waiting for the Empire reveals that colonized migrant women never allowed waiting to become a state of exhaustion and hopelessness. Rather, they endured when they had to and actively engaged with a range of others from officials of the state to churches, businesses, and individuals in an effort to make waiting part of an onward journey to the better life they sought for themselves. Sometimes they were successful, sometimes they were not, but they were never passive. This is therefore the story of ordinary women engaging with waiting in extraordinary ways. In the book I invite readers to share in the experiences of wonderment, epiphany, and sometimes profound sorrow that I encountered in my study of these extraordinary women. I ask readers to bear witness to the accounts of the travelling ayahs and see how their stories help us to re-vision and remember the place of migrant caregivers in colonial histories and thus shed light on the situations of workers in similar situations today.

3 Waiting is a process and phenomena frequently encountered by migrants of past and present societies.

4 V. Crapanzo, Waiting: The Whites of South Africa (New York: Random House, 1985); Christine M. Jacobsen, Marry-Anne Karlsen, and Shahram Khosravi (eds), Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration (Oxon: Routledge, 2021); Shahram Khosravi, ‘Introduction’, in After Deportation: Ethnographic Perspectives, ed. Shahram Khosravi (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), and others.

1. Becoming Travelling Ayahs and Supporting the Empire: Historical and Contextual

2. Waiting in the Heart of Empire: Abandoned Travelling Ayahs and the Contradictions of

3. Creative Resilience in Crisis: Making Arguments and Evoking

4. Capitalizing

5. Travelling Ayahs and Ayahs’ Homes:

6. Travellers’ Tales: Negotiating

List of Illustrations

1. Advertisements offering the services of Ayahs on hospital walls in Kolkata xiii

2. Advertisements pasted on various market streets in Kolkata xiv

3. Traffic of travelling ayahs between India and Britain (1835–1940)

4. Children’s Christmas dinner at sea by Godefroy Durand

5. Looking after a British baby

6. English girl and her Indian nanny or ayah, sailing to England, watch pet parrot and monkey

7. Ports from which travelling ayahs most commonly embarked in India (1876–1940)

8. Ports where travelling ayahs most commonly disembarked in Britain (1876–1940)

15. Nineteenth-century postcard with an Indian ayah at Edinburgh with her ‘charges’

18. Advertisement for the Ayahs’ Home claiming it was self-supporting, 1885

19. Advertisement for the Ayahs’ Home without the phrase ‘self-supporting’, 1887

20. Ayahs’ Home at 26 King Edward Road, London (1900)

21. The same building (as in Fig. 20) in 2017

22. Ayahs’ Home at 4 King Edward Road (1921)

23. The same building (as in Fig. 22) in 2016

24. Travelling ayahs with their matron at the Foreigners’ Fete

25. Ayahs’ Home advertisement, 1890

26. British propaganda poster, World War II Indians in Civil Defence

27. Mary passport image

36.

37.

64.

72.

73.

75.

100.

108.

109.

110.

111.

112.

136. Phulmaya passport

Suzana Rocha passport image

141. Miranda Pedro Sequeira passport image

142. Ka Lisbon Kharsing passport image

143. Mini Phemalu passport image

144. Dhan Maya passport image

145. Maili passport image

146. Sakinabai Ahmed Husain passport image

147. Ka Derissamon passport image

148. Gangabai Makan Misa passport image

149. Sivbai Narayan Shinde passport

150. Rajpati passport image

2. Ships with only one travelling ayah onboard for ships travelling to Britain (1890–1940)

3. Details of travelling ayahs recorded in the ship’s manifests of S.S. Golconda, 1891 and 1901

5. Emotions and emotional lexicons captured in various archival records concerning travelling

Introduction

Mobile Caregivers for the Empire

MAIDS FROM INDIA: HIRE INDIAN MAIDS FOR ABROAD:

Maids From India is a tech enabled and most trusted platform for all your overseas household help needs. We are a one stop destination having our self collected and trusted database of 50,000+ candidates in Mumbai, Navi Mumbai and Thane location within our committed time. All the household services, be it hiring a house-maid or a house-keeping staff, babysitter, nanny or japa maid, cook or chef, elderly care, patient care or a nurse—we provide solutions for all your needs. We specialise in providing housemaids in Dubai, Singapore, Mexico, Canada, USA, Saudi Arabia, Muscat, Hong Kong, Toronto, New York, Malaysia.

Online Advertisement for Maids from India (2020)1

The above advertisement for ‘maids for abroad’ in local dailies and various online websites in 2020 India can be seen as an almost direct descendant of the advertisements placed by or on behalf of the ‘travelling ayahs’ during the imperial period. The term ayah derives from the Portuguese word aio, which closely translates to meaning tutor, carer or servant. In British India, ayah came to mean a child’s nurse or nanny, or a lady’s maid, and was widely applied to female domestic servants. Travelling ayahs comprised a particular subsection of the profession who specialized in serving colonial families travelling by sea between India, Britain, and other destinations.2 Mobile caregivers and domestic servants, then, are not entirely a product of late twentieth-century globalization as they are often portrayed. Consider these two advertisements for travelling ayahs which appeared in newspapers in the late nineteenth century. The first, published in India in 1886 by a servant brokering agency in India on behalf of its client, a European family, read: ‘EXPERIENCED AYAH WANTED for voyage to England in April, must be a good sailor and accustomed to young children. Apply stating

1 ‘Maids From India: Hire Indian Maids For Abroad: Home Help Service Agency in Vikhroli’, https://maid-in-india.business.site/.

2 Primarily colonial families although there were few cases of privileged Indian families travelling with travelling ayahs.

Waiting on Empire: A History of Indian Travelling Ayahs in Britain. Arunima Datta, Oxford University Press. © Arunima Datta 2023. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192848239.003.0001

terms to “S”. ’3 The second, published in Britain in 1890 by a brokering agency in London, read: ‘. . . Experienced Ayahs always waiting for engagements to return to all parts of India.’4 These advertisements, placed by agencies on behalf of both servants and their clients, demonstrate continuity between past and present in the mobile domestic service industry, albeit in changed geo-political contexts. In both cases, South Asian domestic workers, primarily female, were being recruited via brokers to work across the world in the capacity of caregivers.

The expansion of the British Empire had facilitated movement across the globe for both colonizers and colonized. Travelling ayahs had to deal with the challenges of long sea voyages during which they were expected to provide crucial care to their employers and especially to employers’ children. Some of them travelled between India, Britain, and other destinations scores of times, making them some of the most experienced travellers of the imperial era. The ‘ordinary’ labour of these extraordinary women provided an essential part of the infrastructure of Empire, allowing imperial soldiers, planters, merchants, and administrators, amongst others, to undertake long sea voyages with the confidence that their families would be adequately cared for during the passage. Yet the travelling ayahs, a familiar sight in British port cities over a period of more than two centuries, have faded remarkably quickly from British public memory.

The historiography of South Asian labour migrants under the British Empire remains overwhelmingly male-focused. This book seeks to disrupt maledominated narratives by focusing on the gendered work of mobile South Asian women as they engaged with the process of labour migration, interacted with host societies, negotiated colonial laws, and engaged with temporalities in the migration process.5 While contributing to the fields of gender, transnational labour history, and Empire studies, the book also addresses the absence of Indian migrant women workers employed in domestic work from colonial history, especially in the British case. Whilst there is a flourishing literature covering other forms of migrant labour amongst Indian women—such as labour on plantations and in public works in the Caribbean and other parts of Asia,6 the work of migrant Indian caregivers has remained almost invisible.

3 British Newspaper Archives (henceforth BNA), Times of India, 24 February 1886.

4 BNA, The HomewardMail, 9 June 1890. I discuss such advertisements in further detail in Chapters 1 and 4.

5 This book continues the focus on Indian migrant women workers within the British Empire initiated in my first book, Fleeting Agencies: A Social History of Indian Coolie Women in British Malaya (New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

6 Datta, Fleeting Agencies; Gaiutra Bahadur, Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture (Gurgaon: Hachette Book Publishing, 2013); Shobita Jain and Rhoda Rheddock (eds), Women Plantation Workers: International Experiences (Oxford: Berg, 1998); Brij V. Lal, ‘Kunti’s Cry: Indentured Women on Fiji Plantations’, Indian Economic and Social History Review 22.1 (1985): 55–71; Marina Carter, Lakshmi’s Legacy: Testimonies of Indian Women in 19th Century Mauritius (Stanley, Rose Hill, Mauritius: Editions de l’Océan Indien, 1994); Marina Carter, Women and Indenture: Experiences of Indian Labor Migrants (London: Pink Pigeon Press, 2012).

Furthermore, studies focusing on domestic caregiving work in colonial contexts have overwhelmingly looked at ‘local’ labour and not necessarily migrant labour in mobile domestic spaces.7 Waiting on Empire breaks this silence, centring the history of migrant care labourers recruited for caregiving on the high seas, on which the power-relations of Empire were daily enacted. Exploring fragments from the lives of socially marginal women care-workers, who played vital roles in the British Empire’s everyday functioning, Waiting on Empire interrogates colonialism and colonial migration history from a subaltern perspective, and places women’s labour migration and care work in a broad global context. In so doing, it foregrounds South Asian labour history and women’s history as important lenses through which we can study world history and history of the British Empire specifically. The title of this study, Waiting on Empire, of course, has a dual meaning. It refers both to the service the travelling ayahs provided to the Empire, but simultaneously to the active process of waiting—that is, spending time in contexts where further movement depended upon actors more powerful than themselves.

Waiting on Empire focuses on the everyday histories of travelling ayahs, some of whom travelled up to fifty times between India and Britain. In particular, the book focuses on the temporal period of waiting which usually interrupted their migration loops between India and Europe. This waiting period began once they arrived at Britain and lasted until they could find a passage back home to India. The various chapters of the book show how the dynamics of gender, class, ‘race’, and religion, in various combinations, played crucial roles in the ways travelling ayahs experienced waiting in the metropole.8 At a broad scale, this book explores how different actors and institutions interacted with female migrant care workers in the metropole, whilst at the personal level, the book allows the individual, everyday histories of travelling ayahs to emerge, thus recognizing their status as rightful citizens of the Empire: a recognition which they repeatedly demanded during their lifetimes. In the process, the book takes its readers on a journey

7 Fae Dussart, ‘Family and Household: Domestic Service in Colonial India’, in A Cultural History of the Home: In the Age of Empire, ed. Jane Hamlett (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 43–65; Swapna Banerjee, Men, Women and Domestics: Articulating Middle-Class Identity in Colonial Bengal (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004); Indrani Sen, ‘Colonial Domesticities, Contentious Interactions: Ayahs, Wet-Nurses and Memsahibs in Colonial India’, Indian Journal of Gender Studies 16.3 (2009): 299–328; Joyce Grossman, ‘Ayahs, Dhayes, and Bearers: Mary Sherwood’s Indian Experience and Constructions of Subordinated Others’, South Atlantic Review 66.2 (2001): 14–44; Suzanne Conway, ‘Ayah, Caregiver to Anglo-Indian Children’, in Children, Childhood and Youth in the British World, ed. S. Robinson and S. Sleight (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); Sucharita Sen, ‘Memsahibs and Ayahs during the Indian Mutiny: In English Memoirs and Fiction’, Studies in People’s History 7.2 (2020).

8 Whilst the term ‘race’ is regarded as scientifically meaningless today, during the imperial period under discussion, scientific racism remained respectable; the concept of ‘race’ was regarded as a meaningful distinction between different human groups and was used to build social hierarchies. I use the term in parentheses to emphasize that this social significance was built upon a scientific fallacy.