M. Francesca Cotrufo & Yamina Pressler

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/a-primer-on-stable-isotopes-in-ecology-m-francesca-c otrufo-yamina-pressler/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

A Primer of Life Histories: Ecology, Evolution, and Application Hutchings

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-primer-of-life-histories-ecologyevolution-and-application-hutchings/

Statistical Thinking From Scratch: A Primer For Scientists M. D. Edge

https://ebookmass.com/product/statistical-thinking-from-scratcha-primer-for-scientists-m-d-edge/

Transforming Organizations in Disruptive Environments: A Primer on Design and Innovation Igor Titus Hawryszkiewycz

https://ebookmass.com/product/transforming-organizations-indisruptive-environments-a-primer-on-design-and-innovation-igortitus-hawryszkiewycz/

Integration with Complex Numbers : A Primer on Complex Analysis Aisling Mccluskey

https://ebookmass.com/product/integration-with-complex-numbers-aprimer-on-complex-analysis-aisling-mccluskey/

Forest Ecology 5th Edition Daniel M. Kashian

https://ebookmass.com/product/forest-ecology-5th-edition-danielm-kashian/

Translation in Analytic Philosophy Francesca Ervas

https://ebookmass.com/product/translation-in-analytic-philosophyfrancesca-ervas/

Competition Theory in Ecology Peter A. Abrams

https://ebookmass.com/product/competition-theory-in-ecologypeter-a-abrams-2/

Competition Theory in Ecology Peter A. Abrams

https://ebookmass.com/product/competition-theory-in-ecologypeter-a-abrams/

Emergency Psychiatry (PRIMER ON SERIES) 1st Edition Tony Thrasher (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/emergency-psychiatry-primer-onseries-1st-edition-tony-thrasher-editor/

In the past few decades, the field of ecology has made huge advancements thanks to stable isotopes. Ecologists need to understand the principles of stable isotopes to fully appreciate many studies in their discipline. Ecologists also need to be aware of isotopic approaches to enrich their “toolbox” for further advancing the discipline. A Primer on Stable Isotopes in Ecology is a concise and foundational resource for anyone interested in acquiring theoretical and practical knowledge for the application of stable isotopes in ecology.

Readers will gain a more in-depth and complete knowledge of stable isotopes and explore isotopic methods used in ecological research, learning about stable isotope definitions, measurement, ecological processes, and applications in research. Chapters include in-depth descriptions of stable isotopes and their notation, isotope fractionation, isotope mixing, heavy isotope enrichment, and quantification methods by mass spectrometry and laser spectroscopy.

The text guides readers to think "isotopically” to better understand research conducted using stable isotopes. The book also provides basic practical skills and activities to apply stable isotope methods in ecological research. It includes 5 activities through which readers can apply their knowledge to real-world problems and improve their skills for interpreting and using stable isotopes in ecological research. This book is designed for students and scientists from different backgrounds who share the common interest in stable isotopes.

APRIMERONSTABLEISOTOPESINECOLOGY APrimeronStableIsotopesinEcology M.FrancescaCotrufo

DepartmentofSoilandCropSciences,ColoradoStateUniversity,FortCollins,CO,USA

YaminaPressler

NaturalResourcesManagementandEnvironmentalSciences,CaliforniaPolytechnicState University,SanLuisObispo,CA,USA

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©OxfordUniversityPress2023

Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2023935116

ISBN978–0–19–885449–4

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198854494.001.0001

Printedandboundby

CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface Ibecameinterestedinisotopesduringmygraduatestudies(1991–1994),whenmyadvisor,Dr.PhilIneson,andIwerebrainstormingabouthowtoquantifychangesinplant carbon(C)inputsbelowgroundunderelevatedatmosphericcarbondioxide.Weconcludedthatonlyquantitativeisotopetracingcouldanswerthatquestion.Sincethen,I havebeenanisotopesfan,alwaysinsearchoflearningmoreaboutthem!VisitingDr.Jim Ehleringer’slaboratoryandparticipatingintheStableIsotopeEcologyCourseatUtah StateUniversitymademeintoan“Isotopeer”andfurtherdeepenedmyfascinationfor stableisotopes.

Iseestableisotopesasapowerfultooltoadvanceourunderstandingofsoilbiogeochemistryandfindjoyinsharingmyresearchpassionswithstudents.Iestablishedand coordinatedagraduatedegreeprogramin“Developmentandapplicationofisotopic methodologiestoenvironmentalscienceresearch”atmyformerUniversityofCampania,Italy.OnceatColoradoStateUniversity,Idesignedandcontinuetoteacha graduatecoursein“TerrestrialEcosystemIsotopeEcology.”However,inalltheseyears, mystudentsandIsufferedfromthelackofatextbookthatclearlycoveredthebasicprinciplesforthecorrectapplicationofstableisotopesinecologicalresearch.Thisbookwas inspiredbythissentimentandaimstofillthisgap.

Embarkingonatextbook-writingproject,whenIwasalreadyovercommittedbythe research,teaching,andservicetasksofafacultymember,tookcourageandalotof enthusiasm.Forsomeonelikeme,notexpertinpedagogyandnotanativeEnglish speaker,italsorequiredhelpfromatalentedwriterwithpedagogyskills.Thisbook wouldnotexistifYaminaPressler,themosttalentedwriterandpedagogyexpertinmy researchgroupatthetime,hadn’trespondedwiththemostenthusiastic“Yes,let’sdoit!” whenIsharedtheideawithher.Together,webegancraftingatextbooktailoredspecificallytoecologistsandbiogeochemistslookingtounderstandandapplystableisotopes intheirwork.

Inthepastfewdecades,thefieldofecologyandinparticularterrestrialecosystem ecologyhasmadehugeadvancementsthankstostableisotopes.Today,youwillfind presentationsusingisotopetechniquesineveryecologicalconference,andmanypublicationsthatapplystableisotopestoanswerquestionsinecologyandbiogeochemistry. Ecologistsneedtounderstandtheprinciplesofstableisotopestofullyappreciatemany studiesintheirdiscipline.Ecologistsalsoneedtobeawareofisotopicapproachesto enrichtheir“toolbox”forfurtheradvancingourdiscipline.Theincreasingnumberof short,intensive,andconventionalgraduatecoursesonstableisotopeecologyalloverthe worldtestifiestothis.However,anyoneinterestedinstableisotopeecology,inparticular forapplicationsinterrestrialecosystems,hastonavigateamyriadofscientificpublicationsandbookchapters,eachofferingapieceofthepuzzle.Sometimes,researchers

applyisotopictechniqueswithaverylimitedunderstandingoftheunderlyingtheory, leadingtoerroneousconclusions.Webelievethesechallengesemergefromthelackof anapproachablebooktolearnfromandreferto.

Wewrotethisbooktoaddresstheseneedsandprovideaconcise,hopefullyenjoyable, andsolidbackgroundreadingforanyoneinterestedinacquiringstate-of-the-arttheory andpracticalknowledgefortheapplicationofstableisotopesinecology.Thisbookis designedforstudentsandscientistsfromdifferentbackgroundswhosharethecommon interestofexploringstableisotopemethodsintheirresearch,orsimplywouldliketo gainamorein-depthandcompleteknowledgeofstableisotopes.Thetextisdesigned toguidereaderstothink“isotopically”tobetterunderstandresearchconductedusing stableisotopes.Thebookalsoprovidesbasicpracticalskillstoapplyisotopemethodsin ecologicalresearch.Readerswilllearnaboutstableisotopesandtheirnotation,isotope fractionation,mixing,heavyisotopeenrichment,andquantificationmethodsbymass spectrometryandlaserspectroscopy.

Evenwritingarelativelyshortbooklikethisrequireshelpandsupportalongtheway. AbigthanksgoestoDr.JesseNippertandDr.RolandBolforreviewingthetextand providingveryusefulandenthusiasticcomments;Dr.JimEhleringerandDr.PhilIneson forsharingslidesandphotos;andDr.CarstenMüller,Dr.JenniferPett-Ridge,andDr. LivioGianfraniforprovidingsubject-specificsuggestionsandsharingpublications.I amverygratefultoallthestudentsinmylaboratoryandisotopeclasses,whokeptme inspiredthroughalltheseyears,andsharpenedandshapedthewayinwhichIthink aboutandpresentthismaterial.

M.FrancescaCotrufo August31,2022 FortCollins,CO

1.4Stableisotopesrecordbio-physicalresponsestochangingenvironments

1.5Stableisotopessourceandtracemovementofkeyelements,

4.4Concentration-dependentisotopemixing

5.1Isotopelabeling

5.2Carbon-13labelingofplants:continuousversuspulselabeling

5.3Amendmentsofisotope-labeledsubstratesandstableisotopeprobing

ListofAbbreviations APE atompercentexcess

C carbon

CAM crassulaceanacidmetabolism

CDT CanyonDiabloTroilite

EA elementalanalyzer

GC-c-IRMS gaschromatography–combustion–massspectrometry

H hydrogen

IAEA InternationalAtomicEnergyAgency

IRMS isotoperatiomassspectrometry

LC liquidchromatography

NanoSIMS nanosecondaryionmassspectrometry

NIST NationalInstituteofStandardsandTechnology

N nitrogen

NMR nuclearmagneticresonance

O oxygen

P phosphorus

PDB PeeDeeBelemnite

PEP phosphoenolpyruvate

PLFA phospholipidfattyacid

qSIP quantitativestableisotopeprobing

RuBisCO ribulose1,5-bisphosphatecarboxylase/oxygenase

S sulfur

SI InternationalSystemofUnits

SIP stableisotopeprobing

SMOW StandardMeanOceanWater

SOM soilorganicmatter

TDL tunablediodelaser

VSMOW ViennaStandardMeanOceanWaterStandard

1 StableIsotopesasaTool forEcologists 1.1 Introduction Ecologistsaretransdisciplinaryscientists,integratingbiology,physics,chemistry,physiology,biogeochemistry,andseveralotherdisciplinesintheirstudies.Theirtoolkitisthus vastandverydiverse,spanningfromsimpleobservationstostate-of-the-artsophisticatedinstrumentation.Stableisotopesofferapowerfultoolofstudyforanysubdiscipline ofecology.

Ecosystem,plant,soil,microbial,andanimalecologistscanallusestableisotopesto addresstheirquestions.Howlongdoesittakeforacarbondioxide(CO2)molecule totravelfromtheatmospherethroughtheplant,intothesoil,andberespiredback totheatmosphere?Howefficientlydoesaplantusewater,orwheredoplantssource waterfrom?Howmuchoftheorganicmatterofasoilinasavanna-foresttropicalecotoneisderivedfromthesavannagrasses,whichuseaC4photosyntheticpathway,and howmuchfromthetrees,whichuseaC3photosyntheticpathway(seeSection3.6)? Whichmicrobialgrouphasconsumedaspecificsubstrate?Whatisthemigrationroute ofasnowgooseorawhale?Whatarethetrophicrelationshipsinafoodweb?These, andmanymore,arequestionsthatcanbeansweredusingstableisotopesatnatural abundanceorafterenrichmentmanipulations.

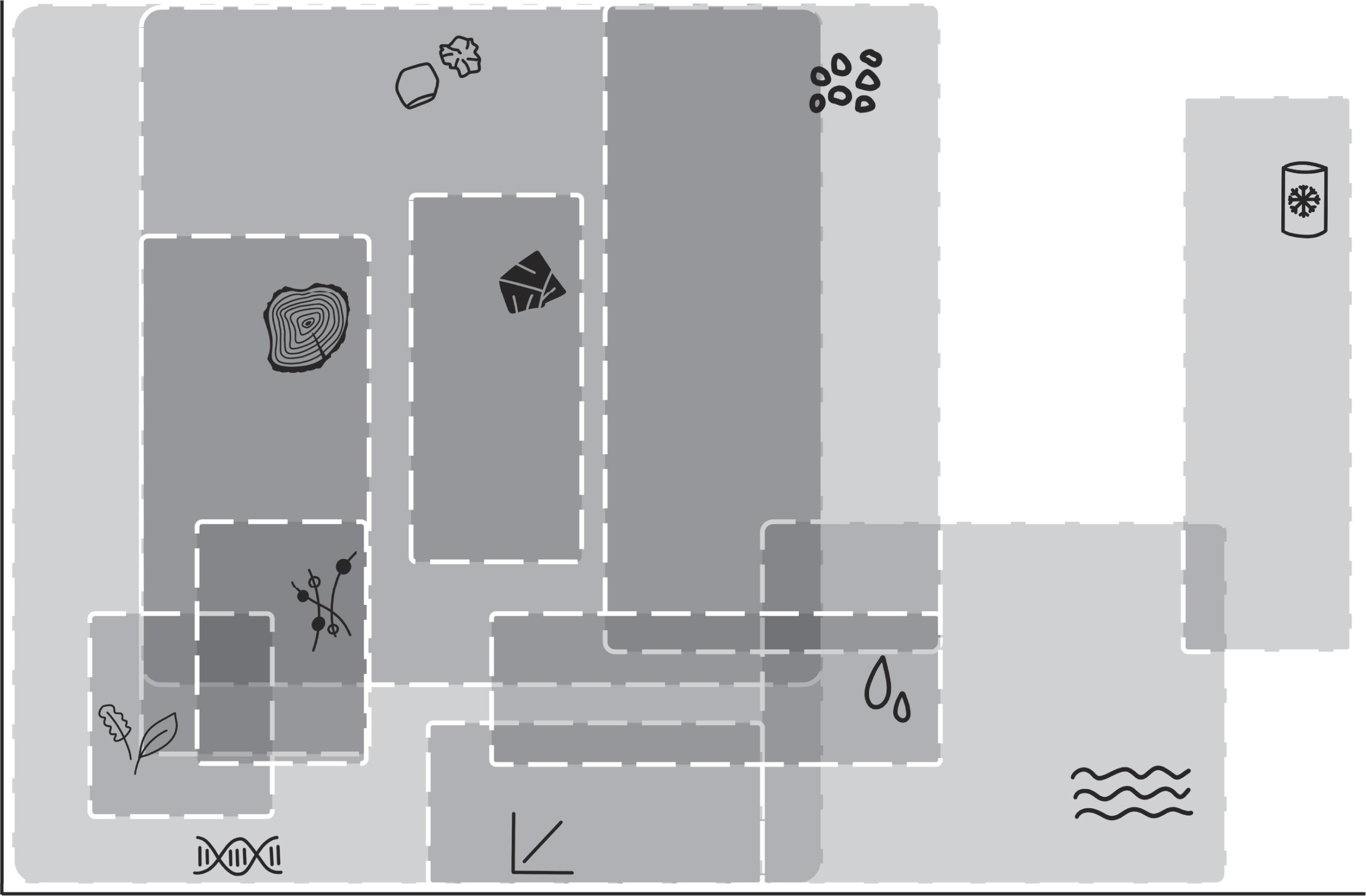

Stableisotopesareapowerfultoolinecologybecausetheyare“oneofnature’s ecologicalrecorders”(Westetal.2006)astheyintegrate,indicate,record,andtrace fundamentalecologicalprocessesacrossabroadrangeoftemporalandspatialscales (Figure 1.1; Tuetal.2007).

1.2 Stableisotopesintegrateecologicalprocesses inspaceandtime

Theisotoperatioofanybiogeochemicalpoolrepresentsatemporalintegrationofthe processesresponsibleforfluxesintoandoutofapool.Thetimescaleofthisintegration dependsontheelementturnoverratewithinthepoolinquestion.Becauseofthis,stable

biomarkers

Figure1.1 Stableisotopeanalysesofavarietyofsamplescancoverwidespatialandtemporalscales. Spatialandtemporalscalesrefertothespatialandtemporalintegration,respectively,ofasampleused forisotopeanalyses.Forexample,asampleoficefromanicecoreintegratesspatiallyacrosstheentire globe,andtemporallyfromayearlyresolutiontohundredsofthousandsofyears.

Modifiedfrom Tuetal.(2007)

isotopesareapowerfultooltostudyturnoverratesofbiogeochemicalpools.Thispropertyhasbeenextensivelyused,forexample,todeterminetheturnoverratesofsoil organiccarbonpoolsaswellasofspecificcompounds,bothatnaturalabundanceafter land-useconversionfromC3toC4vegetationorviceversa(e.g., Balesdentetal.1987; DelGaldoetal.2003)orthroughheavyisotopeenrichments(e.g., Wiesenbergetal. 2008).

Similarly,thetemporalintegrationofstableisotopesinanimalandplanttissues providesinformationonphysiologicalandecologicalprocessesonthelandscape.For example,thenitrogen-15(15N)isotopiccompositionoftissuesofmigratorybirdscan informonbirds’stateoffatigueorstarvation(Hobsonetal.2010),orthecarbon-13 (13C)abundanceintherootsofC3andC4plantslivinginproximitycaninform usontheexistenceofsymbioticrelationshipsthroughcommonmycorrhizalnetworks (Watkinsetal.1996).

Forwell-mixedbiogeochemicalpools,suchastheatmosphere,thestableisotopecompositionintegratessourceinputstothepool,extendingoverlargespatialandtemporal scales.Forexample,sincetheindustrialrevolutioninthesecondhalfoftheeighteenth century,anthropogenicemissionsofCO2 fromthecombustionoffossilfuelshave contributed 13C-depletedCO2 totheEarth’satmosphere.Overtime,thesehavemixed

3 andintegratedwiththeCO2 derivedfromnaturalbiologicalandgeologicalprocesses, resultinginacontinuousdecreaseofdelta(δ;seeSection2.3) 13CofatmosphericCO2 ataglobalscale,knownasthe Suesseffect (Keeling1979).

1.3 Stableisotopesindicatethepresence andmagnitudeofecologicalprocesses Throughfractionation(aprocessthatwewilllearnaboutinChapter3),ecologicalprocessesproducedistinctivestableisotopecompositionsinplant,animal,andmicrobial tissues,andotherbiogeochemicalpools.Thus,thestableisotopecompositionofanelementinapoolreflectsthepresenceandmagnitudeofsuchprocesses.Let’slookata coupleofexamplestounderstandthisconcept.

PhotosynthesisinC3plants(seeFigure3.6)fractionatesagainst 13Cwiththelevelof fractionationdependingonthedegreeofopeningofleafstomata.Sincestomatalopening alsodetermineswaterlosses,photosynthetic 13Cfractionationislinearlyrelatedtothe amountofwatermoleculesaC3plantlosestoacquireamoleculeofCO2,alsoknown aswateruseefficiency.Forthisreason,thenaturalabundanceof 13CintheleafofC3 plantsindicatesCO2 uptakeandtranspirationprocessesandcanbeusedtodetermine themagnitudeofwateruseefficiency(Ehleringeretal.1993).

Nitrogenislostfromsoilsvialeaching,denitrification,orvolatilization,whichallfractionateagainsttheheavyisotope 15N(i.e.,the 14Nispreferentiallylost).Thus, 15N accumulationinsoiltypicallyindicatesthepresenceofNlossprocesses,andthehigher the 15Naccumulation,thehigherthemagnitudeofthoselosses.Forexample, Frank andEvans(1997) quantifiedthe 15NabundanceinsoilsatYellowstoneNationalPark, USA,tobetterunderstandecosystemNdynamicsingrazedandungrazedsites.They observed 15Nenrichmentsinnativegrazers’urineanddungpatchesindicatinghigherN lossprocessesfromthesepatchesthancontrolungrazedsoils(FrankandEvans1997).

1.4 Stableisotopesrecordbio-physicalresponses tochangingenvironments Whensubstratesaccumulateincrementallyovertime,thestableisotopecompositionof thesubstratecanbeusedasarecordofecologicalresponsesorasaproxyforenvironmentalchangesacrossthetimecoveredbythesample(DawsonandSiegwolf2011). Suchincrementalaccumulationoccursintreerings,animalhair,icecores,soilcores, andotherecologicalmaterials.

Mosttreesdepositannualringsintheirtrunk.Analyzingthe 13C,oxygen-18(18O), orhydrogen-2(2H,ordeuterium,D)naturalabundanceofeachringbulktissueorcellulosesenablesthereconstructionoftemporalrecordsofavarietyofclimaticvariables, fromlocaltoregionalscales(McCarrollandLoader2004).Stableisotopesintreerings arealsoapowerfultooltorecordtreephysiologicalresponsestonaturaloranthropogenic eventssuchasvolcaniceruptions(Battipagliaetal.2007)orfires(Beghinetal.2011).

Interrestrialmammals,hairgrowsovertime.Thus,theirisotopiccompositioncan beusedtodeterminechangesintheseanimals’dietatthetimeresolutionoftherateof formationofthelengthofhairincrementmeasured.Forexample, Cerlingetal.(2006) reconstructedstableisotopechronologiesfromhairofelephantsinNorthernKenyato determinetheirdietarychangesbetweenbrowsingonC3vegetationandfeedingonC4 savannagrasses.

1.5 Stableisotopessourceandtracemovement ofkeyelements,substrates,andorganisms Duetofractionation,thestableisotopecompositionofelementpoolswithinandamong ecosystemsoftendiffer.Becauseofthis,andtheconservationofmass,wecanuse isotopicmixingmodelstodeterminetherelativecontributionofsourcepoolswithcontrastingisotopicfingerprintstoamixturepool(aswewilllearnaboutinChapter4).The useofstableisotopestopartitionsourcecontributionsiswidelyusedinecology.Examplesincludethereconstructionoffoodsourcesinanimaldiets(PhillipsandKoch2002; Tykot2004),thepartitioningofwaterorNsourcesinplants(Dawsonetal.2002),and thequantificationoftherelativecontributionofdifferentvegetationinputstothesoil organicmatterpool(Balesdentetal.1987).

Additionally,sincethesourceofanessentialelementacquiredbyanorganismcanbe tracedusingstableisotoperatios,wecantracktheoriginofsubstratesandmovementsof organismsacrosslandscapesandcontinents.Geographicalpatternsofthenaturalabundanceofstableisotopesareknownasisoscapes(Bowen2010).Isoscapesarecommonly usedtotracktheroutesofmigratoryanimals(Hobsonetal.2010)andhavemanyother applications.

Asanecologist,youwillcomeacrossmanyapplicationsofstableisotopesintheliteratureandmayconsiderapplyingtheapproachtoyourownresearchquestions.This bookisdesignedtoprovideecologistswiththebasicprinciplesandconceptsrequiredto understand,interpret,andusestableisotopesintheirresearch.Whilewepresentafew examplesforapplicationsofstableisotopesinecology,mostlyfromthefieldofbiogeochemistryandsoilecologywhichareourfieldsofresearch,wedonotintendtodescribe allecologicalapplicationsofstableisotopes.Weencouragereaderstoexplorethediverse ecologicalapplicationsofstableisotopesinpreviouslypublishedbooks(Ehleringer etal.1993; Unkovichetal.2001; Flanaganetal.2004; FaureandMensing2005; Fry 2006; MichenerandLajtha2008; DawsonandSiegwolf2011; Rundeletal.2012)and publishedsubject-specificresearchpapersinareasofinterest.

References

Balesdent,J.,A.MariottiandB.Guillet(1987).“Natural 13Cabundanceasatracerforstudies ofsoilorganicmatterdynamics.” SoilBiologyandBiochemistry 19(1):25–30. Battipaglia,G.,P.Cherubini,M.Saurer,R.T.W.Siegwolf,S.StrumiaandM.F.Cotrufo(2007). “VolcanicexplosiveeruptionsoftheVesuviodecreasetree-ringgrowthbutnotphotosynthetic ratesinthesurroundingforests.” GlobalChangeBiology 13(6):1122–1137.

Beghin,R.,P.Cherubini,G.Battipaglia,R.Siegwolf,M.SaurerandG.Bovio(2011).“Treeringgrowthandstableisotopes(13Cand 15N)detecteffectsofwildfiresontreephysiological processesinPinussylvestrisL.” Trees 25(4):627–636.

Bowen,G.J.(2010).“Isoscapes:spatialpatterninisotopicbiogeochemistry.” AnnualReviewof EarthandPlanetarySciences 38(1):161–187.

Cerling,T.E.,G.Wittemyer,H.B.Rasmussen,F.Vollrath,C.E.Cerling,T.J.RobinsonandI.Douglas-Hamilton(2006).“Stableisotopesinelephanthairdocumentmigration patternsanddietchanges.” ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesUSA 103(2): 371–373.

Dawson,T.E.,S.Mambelli,A.H.Plamboeck,P.H.TemplerandK.P.Tu(2002).“Stable IsotopesinPlantEcology.” AnnualReviewofEcologyandSystematics 33:507–559.

Dawson,T.E.andR.Siegwolf(2011). Stableisotopesasindicatorsofecologicalchange.London, AcademicPress.

DelGaldo,I.,J.Six,A.PeressottiandM.F.Cotrufo(2003).“Assessingtheimpactofland-use changeonsoilCsequestrationinagriculturalsoilsbymeansoforganicmatterfractionation andstableCisotopes.” GlobalChangeBiology 9(8):1204–1213.

Ehleringer,J.R.,A.E.HallandG.D.Farquhar,eds.(1993). Stableisotopesandplantcarbon–water relations (PhysiologicalEcologyseries).SanDiego,CA,AcademicPress. Faure,G.andT.M.Mensing(2005). Isotopes:principlesandapplications.Hoboken,NJ,John Wiley&Sons,Inc.

Flanagan,L.B.,J.R.EhleringerandD.E.Pataki,eds.(2004). Stableisotopesandbiosphereatmosphereinteractions.SanDiego,CA,Elsevier. Frank,D.A.andR.D.Evans(1997).“EffectsofnativegrazersongrasslandNcyclingin YellowstoneNationalPark.” Ecology 78(7):2238–2248.

Fry,B.(2006). Stableisotopeecology.NewYork,Springer.

Hobson,K.A.,R.Barnett-JohnsonandT.Cerling(2010).Usingisoscapestotrackanimal migration.In:J.B.West,G.J.Bowen,T.E.DawsonandK.P.Tu,eds. Isoscapes:understandingmovement,pattern,andprocessonEarththroughisotopemapping.Dordrecht,Springer Netherlands:273–298.

Keeling,C.D.(1979).“TheSuesseffect: 13Carbon-14Carboninterrelations.” Environment International 2(4):229–300.

McCarroll,D.andN.J.Loader(2004).“Stableisotopesintreerings.” QuaternaryScienceReviews 23(7):771–801.

Michener,R.andK.Lajtha(2008). Stableisotopesinecologyandenvironmentalscience.Hoboken, NJ,JohnWiley&Sons.

Phillips,D.L.andP.L.Koch(2002).“Incorporatingconcentrationdependenceinstableisotope mixingmodels.” Oecologia 130(1):114–125.

Rundel,P.W.,J.R.EhleringerandK.A.Nagy(2012). Stableisotopesinecologicalresearch.New York,SpringerScience&BusinessMedia.

Tu,K.P.,G.J.Bowen,D.Hemming,A.Kahmen,A.Knohl,C.T.LaiandC.Werner(2007). “Stableisotopesasindicators,tracers,andrecordersofecologicalchange:synthesisand outlook.” TerrestrialEcology 1:399–405.

Tykot,R.H.(2004).Stableisotopesanddiet:youarewhatyoueat.In:M.Martini,M. Milazzo,andM.Piacentini,eds. Physicsmethodsinarchaeometry.Amsterdam:IOSPress: 433–444.

Unkovich,M.J.,J.S.Pate,A.McNeillandJ.Gibbs(2001). Stableisotopetechniquesinthestudyof biologicalprocessesandfunctioningofecosystems.NewYork,SpringerScience&BusinessMedia. Watkins,N.K.,A.H.Fitter,J.D.GravesandD.Robinson(1996).“Carbontransferbetween C3andC4plantslinkedbyacommonmycorrhizalnetwork,quantifiedusingstablecarbon isotopes.” SoilBiologyandBiochemistry 28(4):471–477.

West,J.B.,G.J.Bowen,T.E.CerlingandJ.R.Ehleringer(2006).“Stableisotopesasoneof nature’secologicalrecorders.” TrendsinEcology&Evolution 21(7):408–414.

Wiesenberg,G.L.B.,J.Schwarzbauer,M.W.I.SchmidtandL.Schwark(2008).“Plantand soillipidmodificationunderelevatedatmosphericCO2 conditions:II.Stablecarbonisotopic values(δ13C)andturnover.” OrganicGeochemistry 39(1):103–117.

2 StableIsotopes,Notations, andStandards 2.1 Whatisastableisotope? Thematerialworldasweknowitismadeupofarelativelylownumberofchemical elementswhosepropertiesaredefinedbythenumberofprotonsintheiratomicnuclei, whichwerefertoasthe atomicnumber (Z).In1869,theRussianchemistDmitri Mendeleevproposedtoarrangethechemicalelementsonthebasisoftheiratomicnumberinthefirstpublishedversionofwhatweknowtodayastheperiodictableofthe elements(Figure 2.1).

Nuclidesarenucleiwithdifferentconfigurations.Afamilyofnuclideshavingthesame numberofprotons,andthereforebeingofthesameelement,resideinthesameplaceof theperiodictableofelements.Theyarecalled isotopes.Isotopesvaryinthenumberof neutrons (N)andthereforeintheirtotal atomicmass (A),where A = N + Z.

Thewordisotopecomesfromthephrase“isotopos”or“sameplace”intheancient Greeklanguage.In1913,FrederickSoddy,aBritishphysicalchemist,wasthefirstto defineisotopes,bystatingthat“certainelementsexistintwoormoreformswhichhave differentatomicweightsbutareindistinguishablechemically.”Forthis,hewontheNobel PrizeinChemistryin1922(Soddy1923).

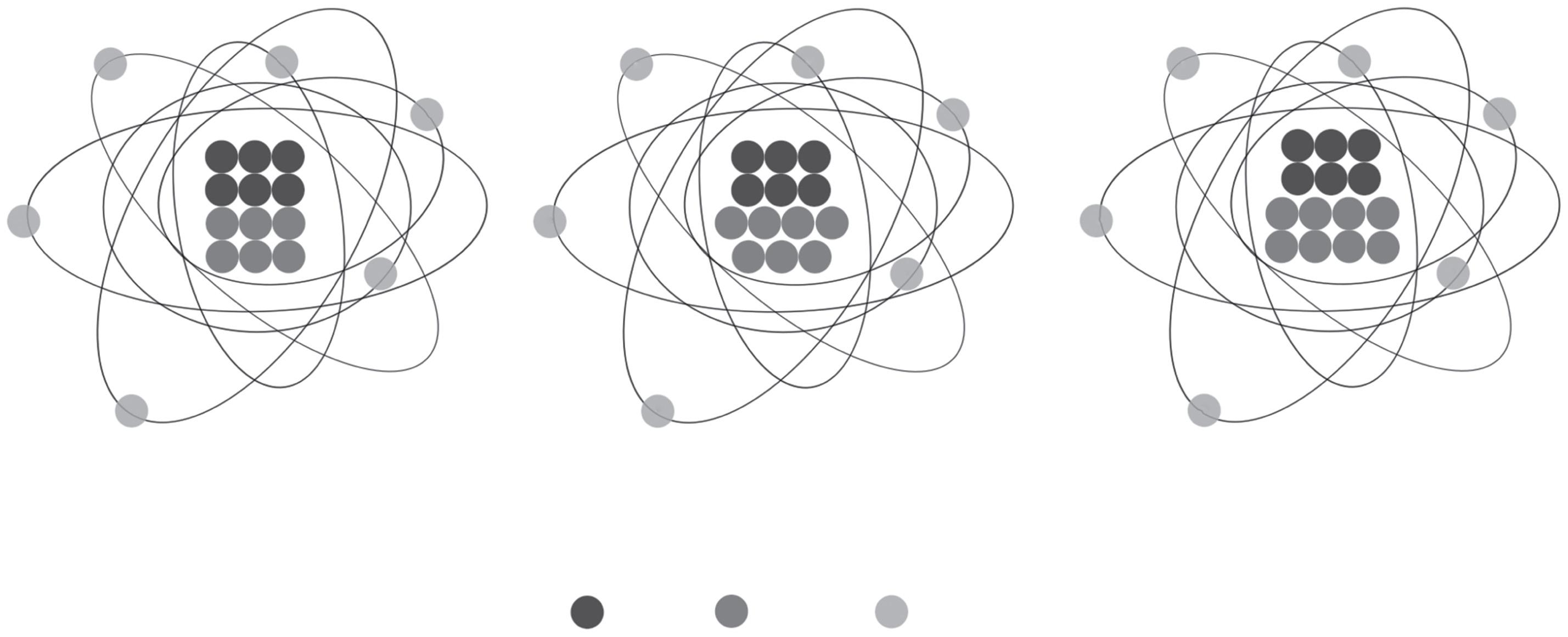

Let’sexplorethisconceptwithanexample.Carbon(C)atomshavesixprotonsin theirnucleus(i.e.,anatomicnumber, Z,of6)whichpositionstheminaspecificplace ontheperiodictable.Carbonatoms,however,canexistwithadifferentnumberof neutrons.Thelargemajorityofthem(98.9%)haveanumberofneutronsequaltothe numberofprotons(N = Z = 6),andthereforeatotalatomicmassof12.Farfewerof them(1.1%)haveanadditionalneutronintheirnucleus(N = 7, A = 13).Finally,an evensmallernumberofCatoms(<10−12%)haveyetonemoreneutron(N = 8, A = 14) whichmakesthemradioactive.WecallCatomswithdifferentatomicmassesCisotopes andidentifythembyaddingtheiratomicmassasasuperscripttotheleftoftheelement symbol,sothat 12C, 13C,and 14CrepresentCatomsofatomicmass12,13,and14, respectively(Figure 2.2).

Figure2.1 Themodernperiodictableofelements.

protons (Z) = 6

(N) = 6

(A) = 12 protons (Z) = 6

(N) = 7

(A) = 13 protons (Z) = 6

(N) = 8

mass (A) = 14

Figure2.2 Conceptualdiagramof 12C, 13C,and 14Cisotopesdemonstratingtherelationshipbetween protons(Z),neutrons(N),andatomicmass(A).Protonsareshownindarkgray,neutronsinmedium gray,andelectronsinlightgray. 12Cismoreabundant(98.89%ofEarth’snaturalCisotopes)than 13C(1.11%naturalabundance)and 14C(<10−12%naturalabundance).

Manyelementshavemultipleisotopes.InadditiontoCmentionedabove,nitrogen (N),oxygen(O),hydrogen(H),andsulfur(S)aresomeofthemoststudiedisotopes inecologyandbiogeochemistry.Therefore,wefocusontheminthisbook.Nitrogenatomsexistas 14N(N = Z = 7,A = 14)and 15N(Z = 7, N = 8, A = 15). Oxygenatomsexistas 16O(N = Z = 8, A = 16), 17O(Z = 8, N = 9, A = 17),

Table2.1 Naturalabundancesofstableisotopescommonlyusedin ecology.

and 18O(Z = 8, N = 10, A = 18).Hydrogenatomsexistas 1H(Z = 1, N = 0, A = 1), 2Hordeuterium(D; N = Z = 1, A = 2),and 3Hortritium(Z = 1, N = 2, A = 3),whichisradioactive.Sulfuratomsexistundermanyisotopicconfigurations,fourof whicharestable: 32S(N = Z = 16, A = 32), 33S(Z = 16, N = 17, A = 33),34S(Z = 16, N = 18, A = 34),and 36S(Z = 16, N = 20, A = 36).Foreachelementoneisotope isoverwhelminglymoreabundantonEarththantheothers(Table 2.1).Ingeneral,the lightestisotopeismoreabundantthantheheavierisotopes(Table 2.1).

Sinceisotopesarehiddenwithintheperiodictableofelements,wecanvisualizethe variationinisotopesinanuclidechart(Figure 2.3).Inthenuclidechart,wecanalso distinguishfamiliesofnuclideswiththesamenumberofneutronsbutvaryingnumbers ofprotons,called isotones,andfamiliesofnuclideswiththesameatomicmass,called isobars (Figure 2.3).

Bydefinition,isotopesofoneelementhavedifferentneutron:protonratios,andthereforedifferentnuclearstability. Whenthenumberofneutronsissuchtoneutralizethe repulsiveforcesoftheprotons,theisotopeisstable.Thatis,thenuclearconfigurationof astableisotopewillnotchangeovertime.Bycontrast,animbalancebetweenprotonsandneutronsresultsinanunstableorradioactiveisotope,whichwilldecaytoa moreenergeticallyfavorablenuclearconfigurationovertime.Interestingly,ofthe2500 knownnuclidesonly270arestable.Radioactiveisotopes,suchas 14Candphosphorus32(32P)and-33(33P)arealsousedinecology.Inthisbook,wewillonlydiscussstable isotopes.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Figure2.3 Nuclidechartshowingtherelationshipbetweenisotopes,isotones,andisobars.Isotopesare nuclideswithvaryingnumbersofneutrons(N).Isotonesarenuclideswithvaryingnumbersofprotons (Z).Isobarsarenuclideswiththesameatomicmass.Notethatthechartisusedtoexemplifythe relationshipbetweenisotopes,isotones,andisobars,butnotallofthenuclidesinthechartexistinnature.

2.2 Isotopocules Isotopesarenuclidesofthesameelement.Isotopeshave,bydefinition,thesamechemicalpropertiesdeterminedbythenumberofprotonsinthenucleus.Thus,different isotopesformthesamemolecules.Therefore,moleculeswithdifferingisotopiccompositionsorwiththesameisotopiccomposition,butdifferentisotopicsubstitutions (i.e.,differentpositionoftheheavyisotopeinthemolecule)bothexist.Molecules withdifferentisotopiccompositionsaredefinedas isotopologues andhavedifferent masses.Moleculeswithdifferentisotopesubstitutionsaredefinedas isotopomers and havethesamemass.Together,isotopologuesandisotopomersofthesamemolecule aretermed isotopocules.However,becauseheavyisotopesformstrongerchemicalbonds thanlighterisotopes,andbondstrengthaffectsmolecularenergydifferentlydepending ontheisotopepositioninthemolecule,allisotopoculeshavedifferentmolecularenergies(Box 2.1).Thesedifferentmolecularenergieshavewidespreadconsequencesfor thebiogeochemicalcyclingofstableisotopesintheenvironment—mostnotably,isotopefractionation.Wewillrevisitisotopoculesinthecontextofisotopefractionationin Chapter3.

Box2.1 Isotopologues,isotopomers,andtogether,isotopocules

Ecologistsleveragethechemicalpropertiesofstableisotopesinmoleculestounderstand, measure,andmanipulatebiogeochemicalprocessesinnature.Understandingtheisotopic compositionofamoleculeisapowerfultoolforgaininginsightintothedynamicsof thatmolecule,anditscomponents,intheEarthsystem.Therefore,wemusthaveaclear understandingofhowstableisotopesarearrangedwithinmolecules.SeeTable 2.2

Table2.2 Definitionsofkeyterms.

Term Definition

IsotopologuesMoleculeswithdifferentisotopic composition,andthereforedifferent masses

Isotopomers Moleculeswithdifferentisotopic substitutions,andthereforethe samemasses

Isotopocules Isotopologuesandisotopomersof thesamemolecule

Let’sconsiderthemoleculeCO2 asanexample.Isotopicsubstitutioncanoccurinboththe CatomsandtheOatomswithinaCO2 molecule.Asaresult,thereare12isotopologuesof CO2,ofwhich 12C16O2 and 13C16O2 arebyfarthemostabundant(Table 2.3).Noticethat in 13C16O2,thelighterandmoreabundantisotope(12C)isreplacedwiththeheavierandless abundantisotope(13C).Whilemuchlessabundant, 17Oand 18Oisotopeswillalsoreplace 16OinsomeCO2 isotopologues(Table 2.3).

Table2.3 Abundancesandmolecularenergiesofisotopoculesofmoleculesrelevanttoecologyand biogeochemistry(isotopomersareindicatedinparentheses).

(Continued)

Table2.3 Continued

AbundanceestimatesfromHITRAN2016database(Gordonetal.2017).

GiventhemolecularconfigurationofCO2,thepositionofagivenisotopeinoneofthetwoO atomsdoesnotchangeitsmolecularenergy.However,somemoleculeshavedistinctmolecularconfigurationsthatleadtoisotopomerswhenisotopesubstitutionoccurs.Forexample, N2OhastwoNatomsthatoccurindifferentpositionswithinthemolecule(Figure 2.4).

The 14NinN2Ocanthereforebesubstitutedwith 15Nateitherposition,resultingintwo isotopomersofN2O: 15Nα-N2Oand 15Nβ-N2O(Figure 2.4).

(a) general structure of N2O + –N N O

(b) structure of 15Nα-N2O isotopomer

(c) structure of 15Nβ-N2O isotopomer

Figure2.4 IsotopomersofN2O. 15Ncansubstitutefor 14Ninbothcentral(α)andterminal(β) positionsofNintheN2Omolecule,resultingin 15Nα-N2Oand 15Nβ-N2O.

2.3 Whydoweusedeltanotation? Thenaturaldistributionofstableisotopesissuchthatoneisotopeisgenerallyoverwhelminglymoreabundantthantheotherrareisotopes.Mostoften,thelightisotopes arethemostabundantwhiletheheavyisotopesarerarer(Table 2.1).Wearegenerally

interestedinthechangeinabundanceoftheheavyisotopes(H)relativetothelight isotope(L).Thisiscalledthe isotopicratio (R):

Smalldifferencesintheisotopiccompositionofanenvironmentalsamplearedifficult toreportbecauseoftheverylowrelativeabundanceoftheheavyisotopewithrespect tothelightisotope.IfreportedasanR,thedifferencewouldoftenbeatthelevelof thefourthorfifthdecimalpoint.Forexample,theheavyhydrogenisotope,deuterium (2HorD)intheViennaStandardMeanOceanWaterStandard(VSMOW)ispresent ataconcentrationof0.015574%,whilethelightisotope(1H)ispresentat99.984426% (Table 2.1).Aswaterevaporatesfromtheoceanintotheatmosphere,moreofthelight isotopewillbecomewatervaporthroughaprocesscalledisotopicfractionation(see Chapter3).Thus,thepercentageof 2Hinwatervapormayreduceevenfurther.Canyou imaginehowharditwouldbetoreportanddiscusschangesinthehydrogenisotopicratio (R = 2H/1H)valuefrom0.00015576oftheVSMOWto0.00014953ofahypothetical watervaporsample?

Toaddressthischallenge,thedelta(δ)notationhasbecomethemostcommon notationusedtoreportnaturalabundanceisotopicvaluesbecauseitamplifiessmall differencesintherelativeabundanceoftherareisotope.The δ notationwasfirstintroducedby McKinneyetal.(1950) inordertoreportthemeasuredisotopicvalueswith referencetoastandard(i.e.,asadifference).Theexpressionforthe δ notationis: δ =(Rsample/Rstandard 1) 1000 (2.2) whereRsample isthemolarratiooftheheavytothelightisotopeforthesampleofinterest, andRstandard isthemolarratiooftheheavytothelightisotopeofthestandard(see Section 2.4).Thus, δ isaratioofratiosandismultipliedby1000foreasierreporting.In fact,the δ notationisexpressedina permill (‰)unit,whichisLatinforperthousand. ForanelementX,withaheavyisotopeY,thedeltanotationiswrittenas δYX.The 13Cabundanceofasamplewillthereforebereportedin δ notationas δ13C.Similarly, δ15N, δ2H(δD), δ18O,and δ32Swillbeusedtodenotetherelativeabundanceof 15N, 2H(orD), 18O,and 32S,respectively.Itisworthnotingthatthe δ notationdoesnot useaunitacceptedintheInternationalSystemofUnits(SI; Slateretal.2001).For thisreason, BrandandCoplen(2012) proposedtheadoptionofanewunit,calledurey (symbolUr),namedafterHaroldC.Urey,toreport δ values,ratherthan‰.Since δ valuesaredimensionless,accordinglytoSI δ isa“quantityofdimension1”(Dybkaer 2003).Theureywouldthusbeconsideredaquantityof1,andavalueof‰wouldbe reportedasamilliurey(mUr).However,thisproposalhasnotfoundmuchacceptancein ecologyandbiogeochemistry,andnaturalabundancestableisotopesarestillcommonly reportedusingthe δ notationin permill (‰).

While δ valuesarestandardizedtomakeisotopicratioseasiertohandle,theymay notbeintuitiveatfirst.So,howdoesthisnotationwork?Giventhisformula,itbecomes clearthatthestandard,bydefinition,hasa δ valueof0‰.Anysamplewhichis enriched

A

B

= 0

C

D

sample A is enrichedintheheavyisotopecomparedtothestandard and all other samples

sample B is enriched in the heavy isotope compared to the standard, sample C, and sample D, but depleted in the heavy isotope compared to sample A

Standard, or samples with the same isotopic composition as the standard

sample C is depleted in the heavy isotope compared to the standard, sample A, and sample B, but enriched in the heavy isotope compared to sample D

sample D is depletedintheheavyisotopecomparedtothestandard and all other samples

Figure2.5 Therelationshipbetweenstandardsandsampleswithpositiveandnegative δ values.

intheheavyisotopeascomparedtothestandardwouldhaveapositive δ value,while anysamplewhichis depleted intheheavyisotopeascomparedtothestandardwould haveanegative δ value.Ausefulthingtorememberwhenfamiliarizingyourselfwith δ valuesisthat thelowerthe δ,thelighterthesample;thehigherthe δ,theheavierthesample (Figure 2.5).

Let’sgobacktoourhypotheticalwatermoleculewhichevaporatedfromtheVSMOW (Table 2.4)withanRof0.00014953.KnowingtheRofVSMOW,thestandardused forhydrogenisotopes,wecancalculatethewatervapor δ2Hvalueas:

Clearly,avalueof−40ismucheasiertohandlethan0.00014953.Additionally,justby thefactthatitisnegative(i.e.,lowerthantheoceanwaterwhichweuseasastandardthat bydefinitionhasa δ valueof0‰),wecanimmediatelysaythatthewatervaporis4% (40‰)lighter(i.e.,depletedintheheavyisotope, 2H),thantheoceanwaterstandard fromwhichitevaporated(Figure 2.5).

2.4 Isotopestandards Whenfirstintroduced,the δ notationwasusedtoidentifysamplevariationsinisotopicabundancefromalaboratoryworkingstandard(McKinneyetal.1950).Itquickly becameevidentthattheuseofglobalstandardswouldenablecomparisonsof δ valuesacrossdifferentlaboratories.Tothisend,committeesofstableisotopegeochemists workedtoidentifyasetofinternationallyacceptedstandardsbeginninginthe1970s.

Standardsaresetupbyanauthoritytofunctionasmeasurereferences.Inthecaseof isotopiccomposition,largeandisotopicallystablematerialswereselectedasstandards. Today,weuseatmosphericN2 (AIR)asthe 15N/14Nstandard,oceanwater(StandardMeanOceanWater(SMOW))asthe 2H/1Hstandard,limestonerock(PeeDee Belemnite(PDB))asthe 13C/12Cstandard,andanironsulfidemeteorite,theCanyon DiabloTroilite(CDT)asthesulfurisotopestandard(Table 2.4).Oxygenisotopescan bemeasuredbothwithreferencetoSMOWorPDB,dependingonthemoleculefrom whichoxygenisotopesarederived.PDBiscommonlyusedforanalysesoforganicor inorganicoxygencompounds,whileSMOWisusedforanalysisofoxygenisotopesin water(Table 2.4).

IsotopestandardsaredepositedattheInternationalAtomicEnergyAgency(IAEA), basedinVienna,Austria,andattheNationalInstituteofStandardsandTechnology (NIST),inGaithersburg,Maryland,USA.BecausetheIAEAisinVienna,theSMOW, PDB,andCDTstandardsareoftendesignatedwitha“V”forVienna:VSMOW,VPDB, andVCDT,respectively.IsotopestandardscanbeacquiredfromtheIAEAorNIST

Table2.4 Isotopiccompositionforinternationalreferencestandards(HandLcorrespondtoheavyand lightisotopiccomponents,respectively).

PeeDeeBelemnitea (PDB) andViennaPeeDee Belemnite(VPDB)

CanyonDiabloTroiliteb (CDT)andVienna CanyonDiabloTroilite (VCDT)

a LimestonefromthePeeDeeFormationinSouthCarolina(derivedfromtheCretaceousmarinefossil Belemnitellaamericana);

bTheCanyonDiabloTroilite,isanironsulfidemeteoritethatimpactedatBarringerCrater,Arizona. FragmentswerecollectedaroundthecraterandnearbyCanyonDiablo.

Tableadaptedfrom Gröning(2004)

StableIsotopes,Notations,andStandards 17 butareveryexpensiveandavailableinverylimitedamounts.Thus,isotopelaboratories commonlyuseworkingstandardstocalibratetheirmeasurements.

2.5 Whenshouldweusefractionalandatom percentnotations? Heavyisotopeabundancecanalsobereportedinproportiontothetotalelement abundance(i.e.,H+L),termedthe fractionalnotation:

Whenthefractionoftheheavyisotopeisexpressedinpercentage,itisdefinedasthe heavyatom%notation(HAP):

Atom%reportsstableisotopeabundanceasamolarfractionandthereforeitisan acceptedSIunit(Slateretal.2001).

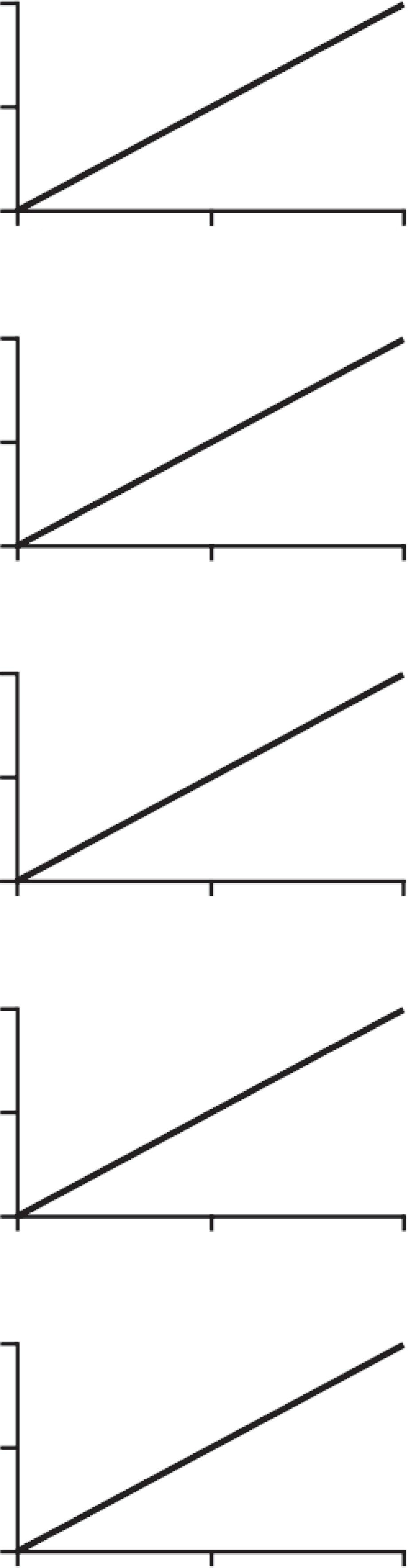

Theatom%notationislinearlyrelatedtothe δ notationatlowheavyisotopeabundancestypicalofthenaturalrangeofheavyisotopes(Figure 2.6).Thus,fornatural isotopeabundancevaluesbothatom%and δ unitscanbeused.The δ notationispreferredforeaseofuseandstandardization. δ valuescanbeconvertedtoatom%values asfollows:

Thevariationinnaturalabundanceofisotopesdiffersbetweendifferentbiogeochemicalpoolsduetoaprocesscalledisotopicfractionation.WewilllearninChapter3how wecanusethisvariationinnaturalabundancetounderstandbiogeochemicalandecologicalprocesses.Heavyisotopescanalsobeartificiallyaddedtoasample,increasingthe heavyisotopeabundancetovaluesoutsidethatofthenaturalrange(seeChapter5).For sampleshighlyenrichedintheheavyisotope,thelinearitybetweenthe δ andtheatom %notationislost,andthe δ notationbecomesinaccurate.Similarly,itiserroneousto usethe δ notationtocalculateisotopicdiscrimination(Chapter3)andinmixingmodels (Chapter4)withhighheavyisotopeenrichmentvalues.Inallthesecasestheatom% notationmustbeused.Additionally,becausethe δ notationisaratioofratiositcannotbe usedtocalculatethecoefficientofvariation,inwhichcasetheatom%notationmustbe used.Wereferthereadersto Fry(2006) foradetaileddescriptionofthecorrespondence amongisotopenotations.

HF=H/ (H+L)

HAP= HF 100

HAP = 100

Figure2.6 Linearrelationshipsbetweenatom%and δ notationfor 2H(a), 13C(b), 15N(c), 18O(d), and 34S(e).

Modifiedfrom Fry(2006)