LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1.1 A visitor looks at ‘Grumpy Old God, 2010’ by artist Grayson Perry during the press view of the exhibition ‘The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’ at the British Museum, London, 5 October 2011. REUTERS/Olivia Harris. 6

1.2 Underside of an Attic red-figure pyxis, c.430–410 bc. BM 1842,0728.924. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 7

1.3 Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Fourth floor, ‘World Ceramics’ display, refurbished 2010. Photograph by Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis, June 2021. 8

1.4 Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens. Fourth floor, ‘Scenes from daily life in antiquity’, ‘Female activities’ theme. © Nicholas and Dolly Goulandris Foundation-Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens. (Photographers: Marilena Stafilidou and Yorgos Fafalis). 9

1.5 Mary Katrantzou, SS17, Look 8 ‘Chariot Dress Bluebird’. Courtesy of Mary Katrantzou. 10

1.6 Apotheon, AlienTrap Games, released 3 February 2015. Courtesy of Alientrap. 11

1.7 British School at Athens collection, antiquities handling session with students from King’s College London, November 2013. Photograph: Michael Squire. 13

2.1a–c Ink and watercolour drawings of a Campanian red-figure amphora from the archive of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. 1620s or 1630s, possibly Matthieu Frédeau. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, F 38955–7. 28

2.2 Drawing of two Attic lekythoi from Dal Pozzo Paper Museum. Windsor, Royal Library Inv. 11,349, 11,350. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021. 30

2.3 Drawings of vessels from Dal Pozzo Paper Museum, Antichità Diverse Windsor, Royal Library Inv. 10269r. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021. 31

2.4 Engraving of an Attic red-figure calyx krater. After Passeri 1767, pl. 7. 35

2.5a Copper engraving of an Attic red-figure hydria. After Hamilton and Tischbein 1791, pl. 7. 37

2.5b Attic red-figure hydria showing the Daughters of Pelias. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum Inv. GR.12.1917. © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. 38

2.6 Ulysses at the Table of Circe. John Flaxman, engraved by James Parker, 1805. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977.595.53(16). 39

2.7 Beazley working in autumn 1956 at the Museo Archeologico, Ferrara. Photograph by Nereo Alfieri. From the Beazley Archive, Courtesy of the Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford. 48

2.8a Red-figure cup fragment showing a vase painter. Attributed to the Antiphon Painter, c.480 bc. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 01.8073.2.8. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

49

2.8b Detail of cup shown in Figure 2.8a. Photograph reprinted by permission from Springer, Paula Artal-Isbrand et al., MRS Online Proceedings Library 1319 (2011) © 2022. 50

3.1 Illustrations of a pelike, from Michel-Ange de La Chausse, Romanum museum, sive Thesaurus eruditæ antiquitatis (Rome, 1690), 101, pls 1–2.

60

3.2 Illustrations of a red-figure pelike and an amphora from the collection of the sculptor François Girardon (1628–1715). De Montfaucon 1719: pl. 71. 61

3.3 A Paestan red-figure bell krater attributed to Python. Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology, University of Reading 51.7.11. Copyright University of Reading.

3.4 Illustration of the Paestan bell krater in Figure 3.3. Passeri 1770: pl. 123.

3.5 Illustration of a Nolan amphora, formerly in the collection of the painter Anton Raphael Mengs, attributed to the Dutuit Painter. Winckelmann 1767: pl. 159.

3.6 Illustration of the scene on the Nolan amphora depicted in Figure 3.5. D’Hancarville 1766–7: pl. 3.4.

3.7 Reproduction of a Raphael drawing from the collection of Queen Christina of Sweden. D’Hancarville 1766–7: pl. 2.20.

3.8 Pelike from Nola, attributed to the Niobid Painter. London, British Museum 1772,0320.23 (E381; BAPD 206984). Photograph Museum.

62

63

64

65

66

69

3.9 A page from Flaxman’s sketchbook depicting the pelike shown in Figure 3.8. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. 72

3.10 Frontispiece of d’Hancarville 1767, showing the pelike illustrated in Figure 3.8.

73

3.11 Blue-and-white transfer ware dresser plate from the Greek series, after 1806. Photograph by the author, with the kind permission of the Trustees of the Spode Museum Trust. 76

3.12 Hamilton 1791–5: 1, pl. 31, source of the vase image shown in Figure 3.11. 77

4.1 Thomas Hope, ‘Athens, A view of the Lysikrates Monument’, c.1787–95. Watercolour on paper 22 × 16 cm. Inv. No. 27241 (cf. Inv. No. 27240). © 2021, Benaki Museum, Athens. 88

4.2 Joseph Michael Gandy (1771–1843), watercolour on paper of a Greek tomb, c.1804. To be identified either as ‘A Cenotaph’ or as ‘View of a Tomb of a Greek Warrior, thought to be ‘The Tomb of Agamemnon’’. 75 × 130 cm. Private collection. Image courtesy of the Bard Graduate Center, photographer: Miki Slingsby. 89

4.3 Sir Martin Archer Shee (1769–1850), portrait of Louisa Hope (1791–1851), c.1807. Oil on canvas. 234 × 132 cm. Reproduced by kind permission of The Hon. Mrs Everard de Lisle. 92

4.4 Benjamin West (1738–1820), ‘The Hope Family of Sydenham, Kent’, 1802. Oil on canvas. 183.2 × 258.44 cm. MFA 06.2362. Abbott Lawrence Fund. 94

4.5 Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807), pl. III. ‘Room containing Greek fictile vases’. Drawing by Thomas Hope, engraved by Edmund Aikin and George Dawe. Art & Architecture Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. 96

4.6 Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807), pl. IV. ‘Second room containing Greek vases’. Drawing by Thomas Hope, engraved by Edmund Aikin and George Dawe. Art & Architecture Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. 96

4.7 Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807), pl. V. ‘Third room containing Greek vases’. Drawing by Thomas Hope, engraved by Edmund Aikin and George Dawe. Art & Architecture Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. 97

4.8 Thomas Hope, Costume of the Ancients (London, 1812), vol. 2, p. 168. ‘Grecian ornaments & scrolls’; ‘Drawn & Etched by Thos. Hope’. Jkc22 +812Hb. Special Collections, Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Yale University. 100

4.9 Red-figure amphora attributed to the Painter of the Louvre Symposion, c.475–425 bc. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 11.17 (Beazley Archive 214410). Side A. 102

4.10 William Hamilton. 1791–5 [1793–1803], Collection of Engravings from Ancient Vases Mostly of Pure Greek Workmanship Discovered in Sepulchres in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, 3 Vols, Naples. Vol. 1, pl. 4. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 103

4.11 Thomas Hope, Costume of the Ancients (London, 1812), vol. 1, pl. 102. ‘Greek warrior from one of my fictile vases’. ‘Drawn by Thos Hope’. ‘Engraved by H. Moses’. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. 104

4.12 Designs of Modern Costume (London, 1812), commissioned by Thomas Hope, pl. 4. ‘H. Moses del et sc.’ Private Collection. 106

4.13 Designs of Modern Costume (London, 1812), commissioned by Thomas Hope, pl. 16. ‘H. Moses del et sc.’ Private Collection. 106

5.1 Jug attributed to the Shuvalov Painter. London, British Museum, E525. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 115

5.2 AEGR I, pl. 26. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 118

5.3 Hydria, c.440–30 bc. London, British Museum, E221. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 118

5.4 AEGR I, pl. 58. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 119

5.5 Kalyx krater in the Manner of the Peleus Painter. London, British Museum, E460. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 119

5.6 AEGR IV, pl. 31. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 120

5.7 AEGR III, pl. 92. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 121

5.8 Lekythos, c.470–460 bc. London, British Museum, D27. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 121

5.9 Lekythos attributed to the Bowdoin Painter. London, British Museum, D22. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 122

5.10a–b Amphora attributed to Group E, 540 bc. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 00.330. 124

5.11 Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder I, pl. I. Courtesy Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Yale University. 126

5.12a–b Amphora attributed to the Antimenes painter. London, British Museum, B244. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 127

5.13 Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder I, pl. II. Courtesy Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Yale University. 128

5.14 Cup signed by Exekias. Munich, Staatliche Antikensammlung, 8729. Wikimedia Commons. 129

5.15 Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder I, pl. XLIX. Courtesy Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Yale University. 130

5.16a–b Pelike attributed to the Painter of the Birth of Athena. London, British Museum, E410. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 131

5.17 Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder I, pl. III. Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Yale University.

131

5.18 Amphora attributed to the Achilles Painter. Vatican City, Museo Gregoriano Etrusco Vaticano, 16571. Scala/Art Resource, NY. 133

5.19 Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder II, pl. CLXXXIV. Courtesy Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Yale University. 134

6.1 Sectional tracings from the Gerhard’scher Apparat showing an Attic black-figure amphora attributed to the Painter of Munich 1379. Munich, Antikensammlung 1379 (BAPD 301469). After Gerhard’scher Apparat Berlin XII, 139. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 148

6.2 Composite tracing based on the sections reproduced in Figure 6.1. After Gerhard’scher Apparat Berlin XII, 18. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz.

6.3 Ink drawing from the Gerhard’scher Apparat showing an Attic red-figure cup attributed to the Foundry Painter. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts,

149

98.933 (BAPD 204364). After Gerhard’scher Apparat Berlin XXII, 77. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 150

6.4 Ink drawing from the Gerhard’scher Apparat representing an Attic red-figure cup attributed to the Ashby Painter. New York, Metropolitan Museum 1993.11.5 (BAPD 212581). After Gerhard’scher Apparat Berlin XXI, 47.1. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 151

6.5 Drawing from the Gerhard’scher Apparat showing an Attic black-figure amphora attributed to the Painter of Berlin 1686. Taunton, Somerset County Museum (BAPD 320388). After Gerhard’scher Apparat XII, 134. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 153

6.6 Drawing from the Gerhard’scher Apparat depicting an Attic red-figure cup signed Epiktetos. New York, Metropolitan Museum 1978.11.21 (BAPD 200498). After Gerhard’scher Apparat Berlin XVI, 21.1. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 157

6.7 Drawing by Carlo Ruspi of Attic red-figured fragments now in Paris, Cabinet des Médailles de la Bibliothèque nationale 385, 532+, 537+, 583+ (BAPD 201702, 212626, 205063, 203925). After Gerhard’scher Apparat Berlin XXII, 01. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz. 158

6.8 Engraving of an Athenian red-figure cup showing the introduction of Herakles on Mount Olympos, signed by Sosias as potter. Berlin, Antikensammlung, Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, F2278 (BAPD 200108). After Monumenti Inediti dell’Instituto di corrispondenza archeologica I, pl. 24, 1835. 160

6.9 Colour lithograph based on the drawings shown in Figures 6.1 and 6.2. After Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder II, pl. CXXI, 2. 161

7.1 The London hydria of the Meidias Painter. London, British Museum E224. Photograph courtesy of the British Museum. 169

7.2 The Karlsruhe hydria. Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe B36. Courtesy of the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe. Photograph: Thomas Goldschmidt. 170

7.3 The London hydria in FR i, pl. 8. Reproduction: Antonia Weisse. 173

7.4 The Duris psykter in FR i, pl. 48. Reproduction: Antonia Weisse. 174

7.5 Eduard Gerhard’s 1839 rendering of the London hydria’s upper picture field: Gerhard 1839, pl. I. Reproduction: Antonia Weisse. 175

7.6 Eduard Gerhard’s 1839 rendering of the London hydria: Gerhard 1839, pl. II. Reproduction: Antonia Weisse. 176

7.7 The Karlsruhe hydria in FR i, pl. 30. Reproduction: Antonia Weisse. 178

7.8 Friedrich Creuzer’s 1839 rendering of the Karlsruhe hydria: Creuzer 1839, pl. 1. Reproduction: Johannes Kramer. 179

7.9 Eduard Gerhard’s 1845 rendering of the Karlsruhe hydria: Gerhard 1845, pl. D2. Reproduction: Johannes Kramer. 180

8.1 Drawing of Herakles and Antaios. Red-figure calyx krater. Paris, Musée du Louvre G103 (after Klein 1886, 118). 190

8.2 Drawing of warriors on black background. Exterior of a red-figure cup. Paris Musée du Louvre G25 (after Hartwig 1893, pl. IX). 192

8.3 Drawing by F. Anderson showing a komos on the exterior of a red-figure cup. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 95.27 (after Hartwig 1893, pl. XLVII). 193

8.4 Drawing by F. Hauser showing the exterior of a red-figure eye-cup. Munich, Antikensammlung 2587 (after Harrison 1895, plate IV). 194

8.5 Drawing of a gymnastic trainer by J. D. Beazley. Red-figure amphora. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 56.171.38, Beazley Archive. Courtesy of the Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford. 195

8.6 Drawing of a komos on a red-figure hydria. Munich, Antikensammlung 2422 (after Brunn and Lau 1877, pl. XXIX). 197

8.7 Drawing of a black-figure exaleiptron with profile of the shape (after Furtwängler and Genick 1883, 18 pl. XXIV).

8.8 Drawing by F. Anderson of a komast on a red-figure neck-amphora. London, British Museum E266 (after Beazley 1911, pl. XI).

8.9 Drawing by Émile Gilliéron père of Theseus and Procrustes on the exterior of a red-figure cup. Athens, National Museum CC1166, former Trikoupis collection (after Harrison 1889, pl. I).

198

200

202

8.10 Restoration proposal by F. Anderson of the exterior of a red-figure cup showing Theseus’ deeds. Paris, Cabinet des Médailles 536 (after Harrison, 1889, pl. II). 203

8.11 Beazley’s Notebook 3, p. 39 [1909]. Drawings from an amphora at Harrow, School Museum inv. 55, Beazley Archive. Courtesy of the Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford. 204

8.12 Double page 29 from Beazley’s Notebook 70 [1910]. Drawings of the name vase of the Berlin Painter. Red-figure amphora. Berlin, Antikensammlung 2160, Beazley Archive. Courtesy of the Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford). 205

9.1 Photograph of a painted scene on an Athenian white-ground pyxis.

BM 1894,0719.1 (Vase D11). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 217

9.2 Two prints of an Athenian red-figure kylix showing a sympotic scene. Name vase of Painter of London E100. BM 1867,0508.1032 (Vase E100).

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 218

9.3a Anderson’s drawing of the red-figure kylix BM 1893,1115.1 (Vase E80).

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 219

9.3b Exterior of the Athenian red-figure kylix illustrated in Figure 9.3a.

BM 1893,1115.1 (Vase E80). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 219

9.4 Anderson’s drawing of the painted scene on an Athenian black-figure neck amphora. BM 1836,0224.10 (B244). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 220

9.5 Strips of acetate taped together form an outer transparent ‘skin’ that can be drawn upon. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 222

9.6a Line-block reproductions of inked line drawings by Anderson.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 223

9.6b Thumbnail aide-mémoire drawings in the Register of Antiquities. Greece & Rome. Vol. 4. 1 June 1888–31 December 1899.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 224

9.6c Anderson’s perspective drawing of BM 1894,1101.475 (C855).

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 224

9.7 Line-block reproduction of Waterhouse’s side view of a Cycladic collared pottery jar with suspension lugs. BM 1912,0831.1 (Vase A304). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 225

9.8 (a) Compass, (b) Line pen, (c) Mapping pen with a Gillott crow quill nib. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 226

9.9 Detail of a drawing by Waterhouse, showing Indian ink applied with a line pen and fine brush. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 227

9.10a Departmental archival print of a Melian bowl. BM 1903,0716.33 (Vase A353). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 227

9.10b Waterhouse’s line drawing of the Melian bowl in Figure 9.10a.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 227

9.10c Waterhouse’s drawing on top of a photograph of the same vessel.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 227

9.11 Bird’s profile drawings of Attic red-figure cups in CVA British Museum 9, fig. 5. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 229

9.12 A pencil drawing of the profile and section of an Athenian red-figure cup.

BM 1843,1103.44 (Vase E62). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 230

9.13a–c An experiment using a forged red-figure calyx krater.

BM 2003,1002.1. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 230

9.14 Photograph of the Standard Grant Projector in the assembly and instruction manual. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 231

9.15 Fragments and reconstructed cross section of an Attic red-figure pelike.

BM 2000,1101.26. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 233

9.16 Different presentations of a forged red-figure skyphos. BM 1978,0323.1.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

9.17a Working drawing of a red-figure Lucanian nestoris at 1:2 scale.

236

BM 1865,0103.17 (Vase F176). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 237

9.17b Digital drawings nearing completion at the ‘layout’ stage.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

238

9.18 Set square, dividers, bent-leg caliper, sticks, vernier caliper, ruler, and profile gauge. The skyphos is the same as that shown in Figure 9.16 (BM 1978,0323.1). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 238

9.19a–b A bucchero hydria BM 1873,0820.356 (Vase H208). a) Hand inked using a dip pen and a Rotring rapidograph. b) Digitally ‘inked’ using Adobe Illustrator. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

9.20 Reconstruction drawing of a black-figure Corinthian kylix.

BM 1924,1201.1174. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

239

240

9.21a Side ‘a’ of the partially reconstructed East Greek black-figure situla from Tell Dafana. BM 1888,0208.1 (Vase B104). © The Trustees of the British Museum. 242

9.21b High-resolution digital photograph of the figured decoration on the vessel shown in 4.21a. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 242

9.21c An acetate tracing of the figured decoration on the vessel shown in 4.21a. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 242

9.21d Digital tracing of the outlines of paint remains on the vessel shown in 4.21a. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 242

9.21e Line drawing of the remaining decoration on the vessel shown in 4.21a. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 242

9.21f A colour reconstruction of the figured decoration on the vessel shown in 4.21a. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 242

10.1 Plate XIII from E. Gerhard, Apulische Vasenbilder des Königlichen Museums zu Berlin (Berlin, 1845): Apulian red-figure hydria (Berlin, Antikensammlung F 3290). 248

10.2 Drawing by F. Lissarrague of an Attic black-figure oenochoe by the Painter of the Half-Palmettes (Trieste S 456). 250

10.3 Drawing by R. Reichhold showing the Geryon cup by Euphronios (Munich, Antikensammlungen 8704) published in Furtwängler and Reichhold’s Auswahl hervorragender Vasenbilder (Munich, 1904). 251

10.4a–c Attic black-figure amphora with Herakles and Geryon (Louvre F 53): (a) in a drawing from the Gerhard’scher Apparat; (b) as published in Gerhard 1843, pl. CVII; (c) in a modern photograph taken at the Louvre. 253

10.5 Plate CVIII from E. Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder, hauptsächlich etruskischen Fundorts, Vol. 2: Heroenbilder (Berlin, 1843): Attic black-figure amphora with Herakles and Geryon. G. Callimanopulos private collection in New York (ex Castle Ashby, Northampton). 254

10.6a–c Attic red-figure chous by the Shuvalov Painter (British Museum E 525), as depicted in the 1801–2 re-edition of AEGR, pls 101 (= fig. 6a), 102 (= fig. 6b), and 103 (= fig. 6c). 255

10.7a–c Attic white-ground lekythos by the Triglyph Painter (Berlin, Antikensammlung F 2680), in two partial photographic views and a drawing. 258

10.8 Attic black-figure amphora with Herakles and Pholos (Bologna, Museo Civico 1436), as illustrated in Gerhard 1843, pl. CXIX. 259

10.9a–b Attic red-figure cup by Makron (Paris, Louvre G 271), interior picture photographed twice under the same electric light, but at a slightly different angle. 261

10.10 Plate LXXIII from Beazley and Caskey 1963, combining photography and drawing to illustrate a cup by Douris (Boston 00.499).

10.11 Plate V from Beazley and Caskey 1931, combining photography and drawing to illustrate an amphora by the Kleophrades Painter (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 10.178).

10.12 Plate LXXXIV from Beazley and Caskey 1963, combining photography and drawing to illustrate a lekythos by the Alkimachos Painter (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 95.39).

265

267

268

11.1 Photographic albums in the Medici Archive. Courtesy of Dr Christos Tsirogiannis.

11.2 Polaroid photograph from the Medici Archive showing a Paestan bell krater in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1989. Photograph: courtesy Dr Christos Tsirogiannis.

11.3a–b Two versions of a plate showing two red-figure amphorae in the auction catalogue of Passavant-Gontard 1929. Photograph a) from catalogue in the DAI, Rome (author); photograph b) from catalogue in Heidelberg (Cassirer and Helbing 1929, plate IV).

11.4 Photograph in the auction catalogue of the Lambros and Dattari collections 1912. Photograph: Hirsch 1912, pl. VI.

11.5 Interior of one of the rooms in Arnold Ruesch’s house in Zürich. Photograph: Galerie Fischer 1936, pl. 25.

11.6a–b Obverse and reverse of a photograph from the Marshall archive showing a Corinthian pyxis and an Attic red-figure lekanis. Photograph by author, after John Marshall Archive, British School in Rome ID1147.

11.7 Four red-figure vases on a table. Photograph from the John Marshall Archive in the British School at Rome, 1921. John Marshall Archive ID192, photograph JM[PHP]-05-0379.

11.8 A group of objects offered to John Marshall in 1914 by the Greek dealer E. P. Triantaphyllos. John Marshall Archive ID580, British School at Rome, photograph JM[PHP]-15-1121.

11.9 Etruscan impasto bowl on a high foot offered to John Marshall in 1925 by de Angelis. Photograph from the John Marshall Archive in the British School at Rome, 1925. John Marshall Archive, photograph ID237, JM[PHP]-06-0460.

11.10 Red-figure bell krater offered to John Marshall by Dr Filippo Falanga. Photograph from the John Marshall Archive, British School at Rome, ID224, JM[PHP]-06-0425.

12.1 Inked profile drawings of Archaic and Classical Attic cups from the Athenian Agora. From Agora 12.2 (1970), fig. 4.

12.2 Carlo Bossoli, pencil drawing of two fragmentary Athenian black-figure lekythoi from the collection of I. P. Blaramberg, probably 1830s. Archive of Odessa Archaeological Museum.

277

278

283

285

287

290

291

293

294

296

305

307

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ABV J. D. Beazley. 1956. Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters (Oxford: Clarendon).

Add2 T. H. Carpenter, J. D. Beazley, L. Burn, T. Mannack and M. Mendonça. 1989. Beazley Addenda: Additional References to ABV, ARV 2 and Paralipomena, 2nd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

AEGR P.-F. H. d’Hancarville. 1766–7 [1768–76] Antiquités étrusques, grecques, et romaines tirées du cabinet du M. William Hamilton: Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Hon. Wm. Hamilton, 4 Vols (Naples: Morelli).

ARV J. D. Beazley. 1942. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters (Oxford: Clarendon).

ARV2 J. D. Beazley. 1963. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, 2nd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

BAPD Beazley Archive Pottery Database http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/XDB/ ASP/dataSearch.asp.

CVA Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum.

FR (i–iii) A. Furtwängler, K. Reichhold, F. Hauser, E. Buschor, C. Watzinger and R. Zahn. 1904–32. Griechische Vasenmalerei: Auswahl hervorragender Vasenbilder, Serie I–III (Munich: F. Bruckmann).

LIMC Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae.

Para J. D. Beazley. 1971. Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure VasePainters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, 2nd edn (Oxford: Clarendon).

Introduction

Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis

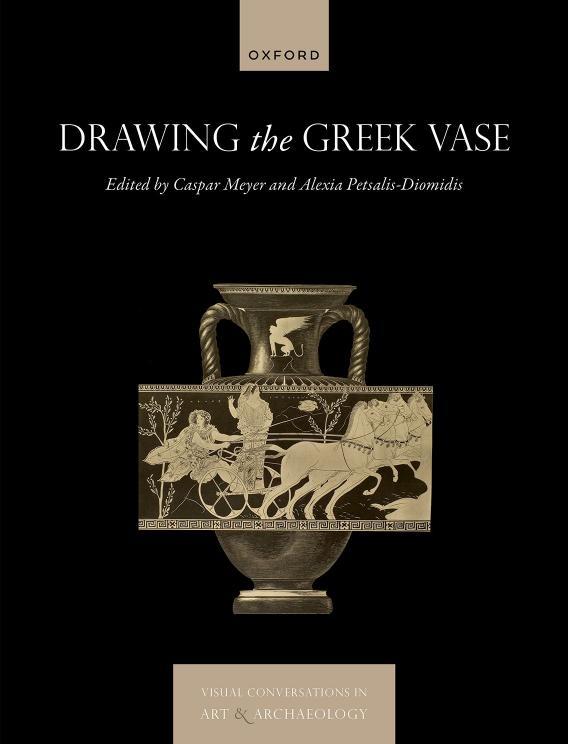

This is the first book to be published exclusively on the subject of two-dimensional depictions of Greek vases. This is remarkable given the proliferation of images of Greek vases or their extracted iconography in art and in publications, ranging from antiquarian luxury folios to recent scholarly textbooks. In addition to the significant presence of such images, the process of their production has been an important feature of artistic and scholarly practice.

Many scholars have in fact considered the subject of depictions of Greek vases and brought them into a range of studies. Such discussions feature above all in scholarship on the history of collecting Greek vases. Images of vases, or images which appear to reflect the painted decoration of Greek vases, have been used as evidence for the timeline of the story of discovery, collection, and restoration of these objects, as well as the ‘taste’ of the time.1 They have been examined with a view to reconstructing the sources of individual painters, such as Donatello, Ingres, Alma-Tadema, and Leighton.2 Discussions of depictions also feature in histories of the scholarship of Greek vases, although there are some surprising silences, revealing the way that images of vases can become almost invisible in the quest for the original object in its antique setting.3 The tracings and drawing practice of the twentieth-century scholar Sir John Beazley (1885–1970) have

1 e.g. Masci 2013: 277–82; Bonora 2003; Sparkes 1996a; Lyons 1992; Jenkins 1988; Vickers 1987; Greifenhagen 1939.

2 On Donatello: Greenhalgh 1982. On Ingres: Picard-Cajan et al. 2006 (particularly contributions by S. Jaubert, C. Jubier-Galinier, P. Picard-Cajan, and M. Denoyelle); Denoyelle 2003; Picard-Cajan 2003. On Alma-Tadema: Barrow 2001: 44–6, 130–4. On Leighton: Jenkins 1983.

3 e.g. R. M. Cook’s history of the study of Greek vase painting, a fundamental text for classical archaeologists and art historians, makes only cursory reference to illustrations and does not analyse their role in the development of scholarly debates. Cook 1997: 275–311.

Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis, Introduction In: Drawing the Greek Vase. Edited by: Caspar Meyer and Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis, Oxford University Press. © Caspar Meyer and Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis 2023. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192856128.003.0001

received considerable attention, as well as engravings of vases in antiquarian books of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in particular.4 The latter have also been studied as an inspiration both for wall paintings in domestic interiors and for objects such as furniture and ceramics, especially in the designs of Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95).5 The emphasis of these sophisticated scholarly discussions has been on images as historical evidence for the collecting and reception of Greek vases. Rarely have visual reproductions of pots themselves been the centre of the enquiry or been analysed for what they can reveal about the modern artistic or scholarly process.6 That, however, is the approach adopted here, foregrounding the images in their own right and as indicators of creative engagement and intellectual exploration.

The volume situates itself at the meeting point of art history, classical reception, and archaeology. Within art history there is a well-established field of study of what is often called ‘the classical tradition’, a description which carries connotations of an august, unchanging canon passed on more or less intact.7 Recently, a more critical approach has been applied, which sees not so much a passive reception of a ‘classical tradition’ but rather a series of contested, evolving encounters with a diffuse body of material, including previous engagements.8 This volume addresses art history and classical reception scholars interested in this latter approach, offering case studies of images produced from the seventeenth to the twentieth century which are in dialogue both with classical art and with contemporary artistic trends. The volume also addresses archaeologists interested primarily in situating vases in their ancient contexts. Specifically it shows how images produced or used by past scholars have constrained and enabled interpretations of Greek vases; more generally it offers a heightened awareness that images of archaeological objects are not just illustrations, reflecting or complementing texts, but are themselves active producers of knowledge.

Building on earlier scholarship, the volume offers greater breadth and depth of analysis of images of Greek vases, with the aim of opening the subject up further. It is not concerned with ‘accuracy’ or ‘truth’ in these representations, but instead foregrounds the fundamental partiality of every depiction of Greek vases, and the diverse roles these images have played. The case studies of this volume, ranging in their chronological focus from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, purposefully include a wide variety of two-dimensional media—ink line drawings, oil paintings, watercolours, engravings and photographs. All graphic depictions tend to begin with drawing as an initial moment of encounter with

4 On Beazley see Rodríguez Pérez 2018; Rouet 2001; Neer 1997; Kurtz 1985. On engravings in antiquarian books see Lissarrague 2003; Coltman 2001.

5 Kulke 2003; Arnold 2003; Coltman 2006. 6 With the notable exception of Sir John Beazley.

7 Silk, Gildenhard, and Barrow 2014.

8 Gilroy Ware 2020; Vout 2018; Squire 2014; Prettejohn 2012.

the object and, as N. Dietrich argues, the conventions of scholarly photographs of Greek vases are heavily influenced by the tradition of scholarly drawings. The inclusion of images from a range of contexts is also purposeful, setting scholarly uses within a broader context of reception. Material is drawn from scholarly archives and publications (C. Meyer, A. Smith, M.-A. Bernard, K. Lorenz, A. Tsingarida, N. Dietrich, K. Morton), luxury publications for elite amateurs and collectors (M. Gaifman, C. Meyer, A. Smith), portrait paintings for display (A. Petsalis-Diomidis), middling publications for use as models by artists and actors (A. Petsalis-Diomidis), and archives associated with the art market (V. Nørskov). In this volume the term ‘Greek’ is used broadly and includes black- and red-figure ceramics produced in ancient Greece and South Italy from the seventh to the fourth centuries bc. While the case studies include some crucial episodes in the history of Greek vase reception, the volume is not comprehensive and there is an emphasis on northern European receptions. It is hoped that the critical approaches applied to this material will be useful to scholars exploring depictions of Greek vases produced in southern Europe and beyond.

The discussion which follows places the volume’s case studies against the background of major developments and approaches in the academic study and reception of Greek vases—it is not a comprehensive history of the historiography of Greek vases. The volume opens with Meyer’s exploration of the practitioner’s perspective and of drawing as a process rather than an end product. The chapter ranges widely from the seventeenth century (Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and Cassiano Dal Pozzo) through the eighteenth (William Hamilton and John Flaxman) to the twentieth (Sir John Beazley), and Meyer makes a number of proleptic connections to other chapters in the volume. He argues that the scholarly practice of drawing Greek vases led to an understanding of drawn lines not only as a representation of imagined space, but also as marks relating to the hand and perception of the artist. This shift from line to hand to senses to person was essential for the creation of the primary scholarly model of attribution to artists which has so dominated the field of ancient pottery studies. More broadly he explores ways in which drawings shape viewers’ perceptions and he shows that the practice of drawing has given rise to new frameworks of interpretation.

Thereafter the chapters are arranged essentially chronologically in order to put into high relief the way that the production and reception of images of Greek vases intersect with contemporary intellectual trends and technological developments. The academic study of Greek vases has a history of well over three hundred years. This is substantially shorter than the histories of the study of classical texts, sculpture, and even small-scale precious antiquities such as coins and gems. The relative lack of interest in Greek vases before the second half of the eighteenth century is itself remarkable. Images of Greek vases in luxury publications began to proliferate towards the end of the eighteenth century. Prior to that,

such representations had appeared only sporadically in publications on ancient art and antiquities, such as the Comte de Caylus’s Recueil d’antiquitées égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques et romaines (1752–57). The dominant approaches to these objects encompassed both artistic appreciation and scholarly recording and there was no clear demarcation between scholarship, collecting, and publishing. The history of the discovery and receptions of Greek vases in this period unfolded in South Italy and Sicily, both as a source for these objects and as a centre of antiquarian scholarship, and in northern Europe, as material was removed to collections there. At the time Greek vases were often mistakenly thought to be Etruscan because most of them were found in Etruscan tombs in Italy. The histories of collecting and reception in Ottoman Greece, Turkey, and the northern Black Sea shore remained separate, and have yet to be fully explored by scholars, particularly in the period before the mid-nineteenth century.9 This initial focus on material from Italy has implications not only for the kind of pottery the first histories of Greek vases were based on (predominantly South Italian red-figure wares and Attic Archaic black- and red-figure specimens imported by the Etruscans), but also for the understanding of the cultural identities of those receiving the vases.

Since the publication of Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (1764), a dominant way of approaching Greek vases has been to use their painted decoration as a proxy for Greek polychrome paintings on panels and walls, which no longer exist.10 This misleading approach came about because of the overwhelming desire to see what is described in ancient texts, not least in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History and Philostratus’ Imagines, which rhapsodize about Greek painting. The use of Greek vases as stand-ins has both elevated them to high art (even though some are, without doubt, poorly crafted and painted) and emphasized their painted decoration at the expense of their threedimensional ceramic utility. Comparisons of Greek vase painting with the work of Raphael, and Greek potteries with Renaissance workshops, subsumed these ancient artefacts into a tradition of Western artistic progress. Smith argues that Winckelmann’s characterization of vase paintings as worthy of Raphael had an impact not only on the status of these artefacts but also on the way that contemporary artists chose to depict them. William Hamilton (1730–1803) was a key figure of the second half of the eighteenth century who both collected and had his vases engraved and published. He is discussed in depth by Gaifman, and he also features in the chapters by Smith, Petsalis-Diomidis, and Dietrich. Smith and Gaifman explore the way in which, despite the rhetoric of faithful reproduction, Greek vases were transformed into modern forms of framed painting,

9 Tunkina 2002; Bukina, Petrakova, and Phillips 2013.

10 See Gaifman, Smith, and Meyer in this volume.

drawing, and illustration by the pervasive practice of excising their painted decoration from the three-dimensional vessels and flattening it on the page, and by the use of modern graphic conventions and styles such as shading and neoclassical outline drawing. Dietrich argues that these images reveal an unexpected documentary intent as well as their long-recognized aesthetic concerns, thus showing that scholarship and art were coexistent, essential elements in one of the most influential eighteenth-century publications on Greek vases.

The history of receptions of Greek vases, encompassing collecting and creative responses, is at least as long as that of academic study. In the eighteenth century receptions included a cascade of reproductions in all sorts of media ranging from luxury and artists’ publications, oil paintings (particularly in portraits), through ceramics, soft furnishings, and sartorial fashion. Yet the study of receptions of Greek vases has a relatively short history, something surely related to the literary origins of this field.11 Classical material culture is receiving increasing attention within this scholarly tradition, although painted vases still lag behind monumental stone sculpture, considered a more prestigious medium. Studies of the history of collections of vases are proliferating, and more recently the role of non-elites and non-Western communities in (re)productions and consumption of cheaper products is also being explored.12 Petsalis-Diomidis’s chapter on Thomas Hope (1769–1831) explores two-dimensional receptions of Greek vases in a variety of graphic styles and their use in subsequent three-dimensional designs for clothing and furniture. Hope’s explicit intention in his affordable publications was to make his designs accessible to artists and craftsmen who would use them to transform the aesthetics and morals of British society. These images mediated an embodied engagement with Greek vases through dress, furniture, interiors, and even movement.

This chapter thus discusses an instance of a particularly interesting strand of vase reception, that of embodied imitation of, on the one hand, the figures depicted on vases and, on the other hand, the craftspeople who produced the vessels. Other notable examples of embodied imitation of painted scenes include the ‘attitudes’ of Emma Hamilton (1765–1815), and the choreographed dances and production of woven textiles at the Delphic festivals by Eva Palmer Sikelianos (1874–1952).13 An instance of the re-enactment of ancient production of vases is Wedgwood and Bentley’s inscription of ‘artes Etruriae renascuntur’ (‘the arts

11 e.g. Bérard 2014; Bourgeois and Denoyelle 2013; Heringman 2013: 125–218; Coltman 2012 and 2006; Brylowe 2008; Masci 2008; Zambon 2006; Nørskov 2002; Tsingarida 2002; Lyons 1997; Jenkins and Sloan 1996.

12 Petsalis-Diomidis with Hall 2020; Petsalis-Diomidis 2019.

13 On Emma Hamilton see Slaney 2020; Brylowe 2008; Touchette 2000. On Palmer Sikelianos see Leontis 2019, esp. 3 (poses after the figure of Sappho on an Athenian red-figure hydria). Delphic festivals in 1927 and 1930.