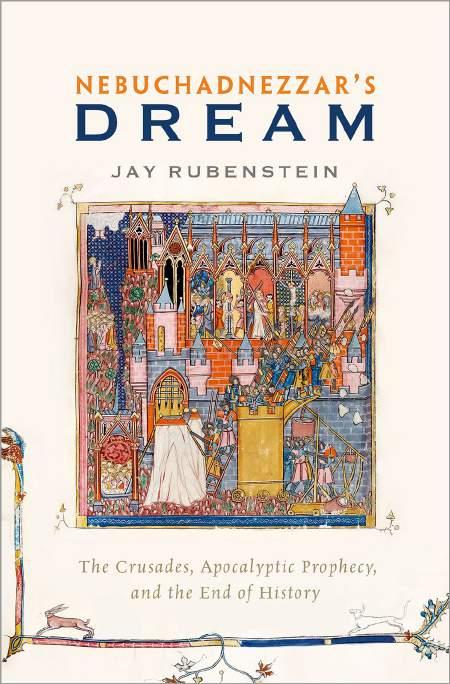

Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream: The Crusades, Apocalyptic Prophecy, and the End of History Jay Rubenstein

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/nebuchadnezzars-dream-the-crusades-apocalyptic-pr ophecy-and-the-end-of-history-jay-rubenstein/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

John among the Apocalypses: Jewish Apocalyptic Tradition and the 'Apocalyptic' Gospel Benjamin E. Reynolds

https://ebookmass.com/product/john-among-the-apocalypses-jewishapocalyptic-tradition-and-the-apocalyptic-gospel-benjamin-ereynolds/

Women and the Crusades Helen J. Nicholson

https://ebookmass.com/product/women-and-the-crusades-helen-jnicholson/

The Queens of Prophecy and Power Danielle Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-queens-of-prophecy-and-powerdanielle-hill/

Enterprise AI in the Cloud: A Practical Guide to Deploying End-to-End Machine Learning and ChatGPT™ Solutions Rabi Jay

https://ebookmass.com/product/enterprise-ai-in-the-cloud-apractical-guide-to-deploying-end-to-end-machine-learning-andchatgpt-solutions-rabi-jay/

The Scribes of Sleep: Insights from the Most Important Dream Journals in History Kelly Bulkeley

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-scribes-of-sleep-insights-fromthe-most-important-dream-journals-in-history-kelly-bulkeley/

Reading the Dream: A Post-Secular History of Enmindment

Peter Dale Scott

https://ebookmass.com/product/reading-the-dream-a-post-secularhistory-of-enmindment-peter-dale-scott/

The Science of Dream Teams Mike Zani

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-science-of-dream-teams-mikezani/

The End of Empires and a World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization. 1st Edition Martin Thomas.

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-end-of-empires-and-a-worldremade-a-global-history-of-decolonization-1st-edition-martinthomas/

The Dream Spies Nicole Lesperance

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-dream-spies-nicolelesperance-2/

Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream

THE CRUSADES, APOCALYPTIC PROPHECY, AND THE END OF HISTORY

Jay Rubenstein

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Jay Rubenstein 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rubenstein, Jay, 1967– author.

Title: Nebuchadnezzar’s dream : the Crusades, apocalyptic prophecy, and the end of history / Jay Rubenstein.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008319 | ISBN 9780190274207 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Crusades—First, 1096–1099. | Crusades—Second, 1147–1149. | Jerusalem—History—Latin Kingdom, 1099–1244. | End of the world—History of doctrines—Middle Ages, 600–1500.

Classification: LCC D161.2 .R746 2019 | DDC 956/.014--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008319

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. United States of America

For Edward

CONTENTS

List of Figures ix

List of Tables xi

Maps xiii

Preface xvii

part i: Prophecy and the First Crusade 1

chapter 1: Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream, 600 bce 3

chapter 2: Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream, 1106 ce 7

chapter 3: Building Blocks of the Apocalypse 21

chapter 4: The Oncoming Madness of Antichrist 35

chapter 5: Sacred Geography 49

part ii: Warning Signs 65

chapter 6: Crusaders Behaving Badly 67

chapter 7: Troubling News from the East 80

part iii: Prophecy Revised (1144–1187) 99

chapter 8: The Second Crusade’s Miraculous Failure 101

chapter 9: Translatio imperii: Leaving Jerusalem 123

chapter 10: Apocalypse Begins at Home 143

part iv: The New Iron Kingdom 165

chapter 11: Jerusalem Lost 167

chapter 12: The Crusade of Joachim of Fiore 181

conclusion: The Ongoing Madness of Antichrist 208

Acknowledgments 221

Notes 223

Select Bibliography 259

Index 269

LIST OF FIGURES

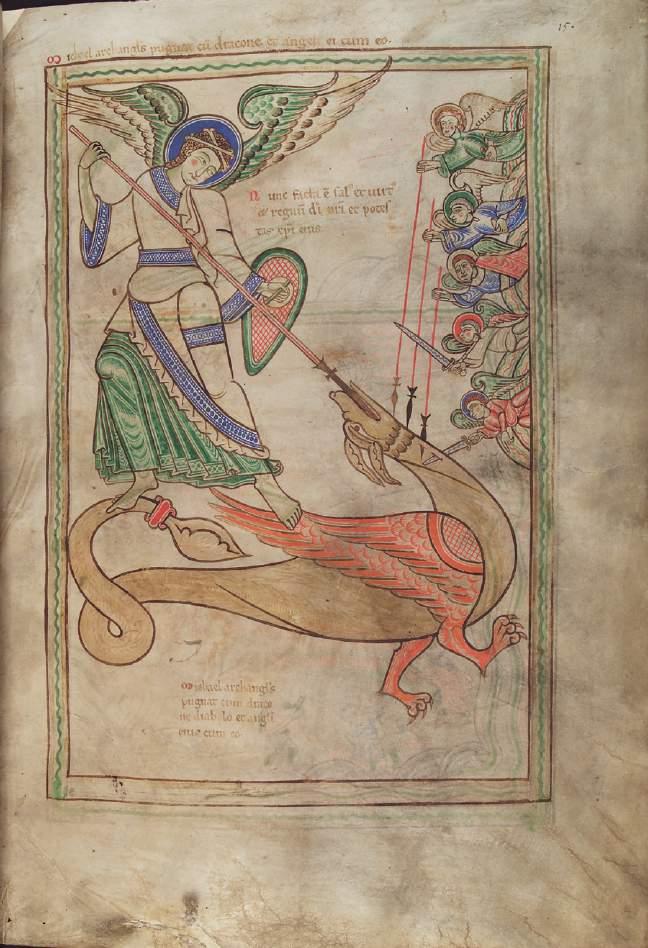

figure 1: Michael Battling the Dragon

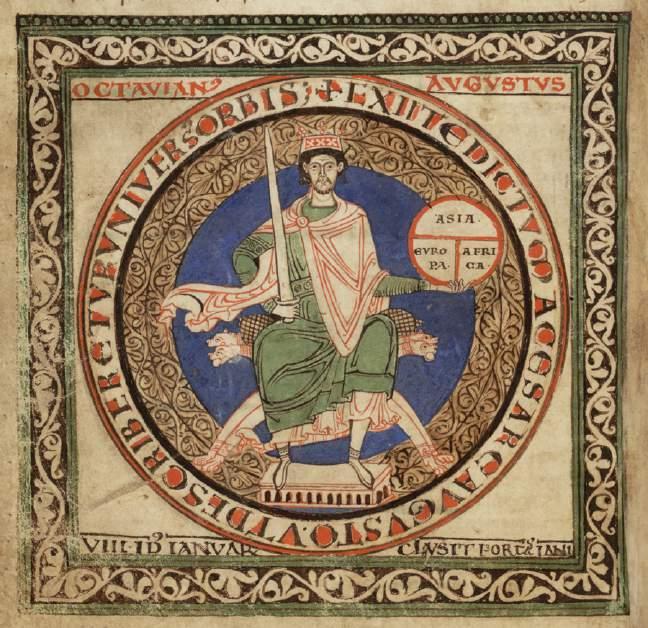

figure 2: Augustus Caesar at the Fulcrum of History

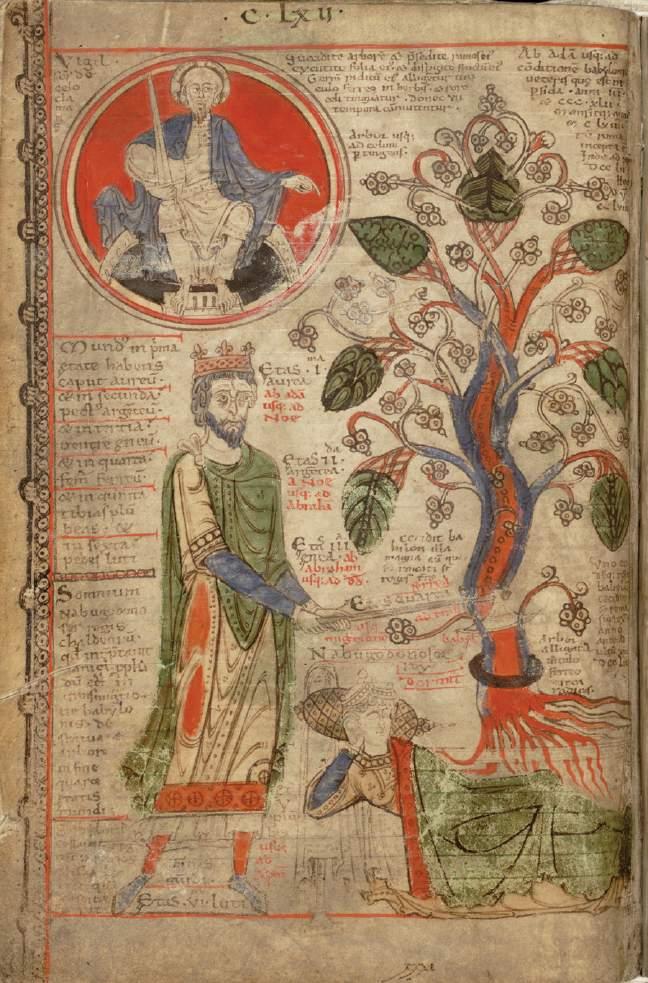

figure 3: Lambert’s Illustration of Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream

figure 4: Antichrist Seated on Dragon

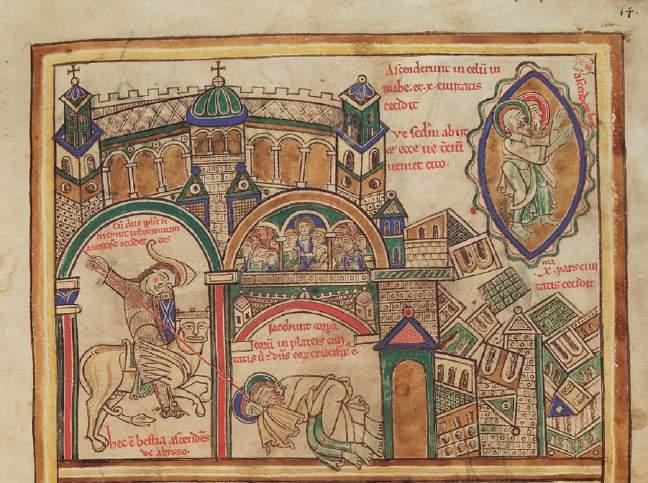

figure 5: Antichrist’s Activity from the Book of Revelation

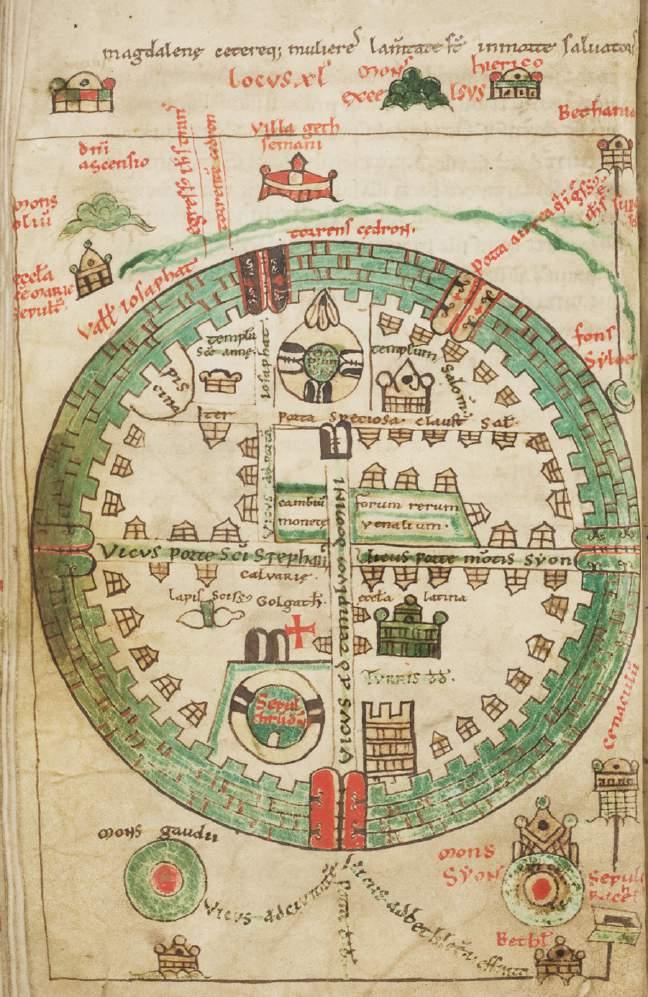

figure 6: The Saint-Bertin Map of Jerusalem

figure 7: A Crocodile

figure 8: Alexander the Great

figure 9: Rome and Babylon in Otto of Freising’s Two Cities

figure 10: Augustus Caesar in Otto of Freising’s Two Cities

figure 11: Otto the Great in Otto of Freising’s Two Cities

Figure 12: Henry IV Faces Henry V at the Regen River

figure 13: Antichrist Emerges from the Loins of the Church

figure 14: Frederick Barbarossa on the Eve of Departing for Jerusalem

figure 15: Joachim’s Red Dragon

figure 16: Two Trees, Representing Joachim’s Two status of History

LIST OF TABLES

table 1: Lambert’s Six Ages of History 28

table 2: Lambert’s Three Ages of History 28

table 3: Lambert’s Kingdoms and Ages of the World 33

table 4: Bernard’s Model of the Hours, Temptations, and the Apocalypse 110

table 5: Bernard’s and Gerhoh’s Fourfold Models of History 157

table 6: Joachim’s Trinitarian Model of History 185

table 7: Joachim’s First Presentation of the Seven tempores 191

table 8: The Seven Seals, from the Exposition of the Apocalypse 193

table 9: Joachim’s Later Reading of the Seven Seals 203

table 10: Joachim’s Reading of Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 205

PREFACE

This book began with an observation and the question that followed upon it. The observation involves one of the most creative historians of the Middle Ages, Guibert of Nogent (ca. 1060–1125), and how he looked at the key event of his lifetime, the First Crusade. In addition to being one of the most perceptive writers of his day, Guibert was also one of the most melancholic and dyspeptic, not often given to enthusiasm about the state of human affairs. Upon first hearing the news of the campaign for Jerusalem’s capture, he became uncharacteristically excited about the crusade. By the end of his life, however, his attitude toward it had grown more jaundiced. He had become disillusioned with the whole enterprise.1 The question then followed from this observation: Was Guibert’s disillusionment widely shared? How did his contemporaries look upon the event that has come to define their age?

To answer this question in full, which this book will try to do, requires first addressing another question. If disillusionment such as Guibert’s followed the First Crusade, what was the illusion that had originally inspired it? The First Crusade, and in particular the capture of Jerusalem, had changed the course of history. Indeed, it represented in the eyes of contemporaries probably the most important event ever. But more fundamentally, it changed not just perceptions of the past but of the future. Human potential seemed limitless, but time itself was winding down. Divine closure, in the form of the Apocalypse, was at hand.

That is where my work ended, but when I began, I was confident that the Apocalypse and the crusades had nothing to do with one another. Recent historians have almost all agreed on this point: When talking about the crusade movement, it is best to avoid prophecy. Such an attitude, more importantly, conformed to Guibert’s prejudices, too. It was a point of principle for him. Rather than a prophetic framework, the most meaningful level of interpretation of any event or idea was, for him, moral, or tropological, something akin to what modern readers think of when they hear the word psychological: How

is the human mind structured, and what makes people behave as they do? Guibert’s goal as a teacher and writer was to change hearts. Promises of heavenly reward and threats of hellfire, he thought, were ineffective tools for reaching listeners and teaching them how to behave. Whatever the reason for Guibert’s disillusionment, it could not be because it didn’t meet his apocalyptic expectations. Guibert had none to begin with.

Yet during the course of my work, I kept noticing exceptions in the foundational sources for crusade history to what I believed the anti-apocalyptic rule. Eventually, I had made note of so many instances of apocalyptic language that I had to throw the rule out altogether. That earlier, skeptical consensus was understandable. Historians try to empathize with their sources, to treat them (with rare exception) respectfully, or to at least assume that historical figures with whom they are engaged were rational actors, that they had sound reasons for what they thought and wrote, and weren’t prone to lunacy. In our age, those who believe in the Apocalypse are dismissed as mad, the kind of people who reject reality and retreat into allegorical or literal bunkers.

For most historians, it has been far easier to see the crusades as driven by a desire for wealth, territorial expanse, or colonial dreams. Or if religion drove them, it would likely be a need for penance on the part of the soldiers, a desire for salvation, a dream of redemption for themselves or their families. In the halcyon days of the early 1990s, when history supposedly had ended and liberal democracies stretched into the future as far as the prophetic eye could see, this sort of modernizing, empathetic retelling of crusade history seemed the only rational approach. Now that we have reentered an age where religious violence is not so foreign, where its enactors openly dream of bringing about the End Times in some form or other, an apocalyptic reading of crusade sources seems compelling, or at least pardonable.

The story told here, however, is not about the rage for apocalyptic thinking that erupted in 1099. It is rather an examination of the question that animated Guibert and other contemporary writers, and one with revived relevance. What had the capture of Jerusalem changed and would these changes endure? Behind it is the question of how to live with an ongoing apocalyptic war, one that seemingly can end only with the destruction of institutions of human judgment and secular government and their transformation into something eternally enduring. That was the illusion that Guibert embraced and then gradually let go.

Part 1 lays the foundation for this project by laying bare the illusion. In its initial conception, the First Crusade was understood and interpreted in biblical, prophetic language. This vision originated not with theologians. It came, rather, from Bohemond of Antioch, from soldiers who had helped lead the crusade and who proclaimed that by taking Jerusalem, the crusaders had fulfilled prophecies from the book of Daniel, prophecies involving the ancient Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar and a dream about statues and a magical rock. The dream’s interpretation had long been shrouded in obscurity, but now those meanings were coming clear, according to Bohemond. A man of remarkable charisma—he was tall and uncommonly handsome, it was said—Bohemond was a brilliant field tactician without whose leadership the crusade would have likely failed during the long siege of Antioch (October 1097–June 1098).

But for all his charm and genius, as well as his facility at selfpromotion, Bohemond was a soldier—and a mercenary’s son—not a scholar. And he was an opportunist, too, having abandoned the crusade shortly after the fall of Antioch, preferring to remain as the city’s ruler rather than to continue on the road to Jerusalem. Even in 1106, as he preached about the prophetic significance of the crusade, his eyes were fixed on not a Muslim but a Christian enemy, the Byzantine ruler Alexius Comnenus, whose empire he hoped to claim. Bohemond’s presentation was therefore, for multiple reasons, a bit rough around the edges. Better-educated historians needed to put a nicer gloss on it. None did more in this cause than Lambert of SaintOmer, a Flemish canon who is one of the principle figures in this narrative. Lambert placed the conquest of Jerusalem at the culmination of world history. That was the illusion; that was the grand hope. European soldiers had fulfilled prophecies of both the Old and New Testaments.

But this view of history had consequences, which form the subject of Part 2. These consequences also help to explain the sources of Guibert’s disillusionment. Because of their achievements, born of personal purgation and purity, veteran crusaders were being held to impossible standards of conduct and virtue. The turbulent and at times pathologically brutal behavior of some of these men—justified by appeals to their status as crusaders—would have given any thoughtful observer cause to question how they or their achievements could possibly fit into God’s plan. Additionally, the triumph of the crusade carried in its wake hundreds of stories of tragedy, now mostly lost to view but certainly known to contemporaries. It is not a question of whether the First Crusade remained popular or else a target of

scathing criticism. It is, rather, a recognition that the idealized version of the story crafted in the years following 1099 was from the start vulnerable to doubt, and that such doubt would have been present well before the first great failure in the crusade movement, the Second Crusade (1146–49).

The Second Crusade was indeed a monumental disaster, and its impact on the memory of the First Crusade is the primary focus of the third part of this book. It was the moment when the disillusionment experienced earlier by Guibert became widespread. The mismanagement of the campaign and its shockingly fast and dire denouement alone would have undercut the idealistic memory of the First Crusade.

Perhaps more startling than the historical and political changes inspired by the Second Crusade were the concomitant changes in prophetic thought itself. Effectively, Christian theologians and intellectuals began writing Jerusalem and the Holy Land out of their apocalyptic narratives. Revelation, the advent of Antichrist, the Second Coming of Christ—all looked more likely to be events that would occur inside Europe, products of ongoing battles between popes and emperors, rather than the result of wars fought in the distant East.

Christian Europe might have continued down this self-critical road and eventually lost interest altogether in the settlements in the Holy Land and in continuing the crusade project. In 1187, however, the Muslim general Saladin conquered Jerusalem, an event shocking enough to demand yet another revision of history and another reinvention of prophecy. That is the subject of the fourth and final part of this book. The fiction that the First Crusade had been a transformational moment in salvation history could no longer be maintained. It was just another battle. Armageddon might yet occur in Jerusalem, but if so, the First Crusade would be only a footnote to it. It surely is no coincidence that at this precise moment, when external events dictated a complete rethinking of the Apocalypse, the most influential prophetic thinker in the Middle Ages, Joachim of Fiore, began writing in earnest. Among his many other achievements, which have been widely recognized and even celebrated, Joachim forced a complete reevaluation of the importance of both the First Crusade and of the ongoing crusade movement. Despite his reputation as a medieval thinker unusually tolerant toward outside groups, including Muslims, Joachim’s vision embraced an inevitable and probably endless conflict between Christendom and Islam, between West and East.

A final word on terminology. The word apocalypse literally means “revelation.” In the Latin tradition, it is the title of the last book of the Bible, written by John of Patmos (an obscure figure who, in the Middle Ages, became conflated with John the Apostle). It also refers to a genre of literature about the End Times and Last Judgment, a genre to which Jewish, Christian, and Muslim writers have all contributed. Among students of the Middle Ages, “apocalypse” refers to a belief that the Last Days are imminent (as opposed to eschatology, which refers to a general interest in the Last Days, without a sense that they are at hand). A related concept is millennialism or millenarianism, a belief based on Revelation 20 that Christ will return to earth to rule for one thousand years before the Last Judgment actually occurs. Because of the association between this last belief and socialist utopias, millennialism has been the focus of most histories of apocalyptic thought—the lead character, as it were.2 In this book, by contrast, millennialism plays only a minor part.

The ongoing fascination with millennialism does help to explain why historians of apocalyptic thought have taken so little interest in the crusades. And although I will make frequent use of the word apocalypse, the book of the Apocalypse proper did not exert significant influence on twelfth-century thinkers who tried to isolate the intersections between prophecy and current events. The most important text was instead the book of Daniel, specifically the story of that dream of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, a dream with whose historical context this story shall begin.

1. St. Michael slaying the dragon, from Lambert of Saint-Omer’s illustrated Apocalypse. Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel, Cod. Guelf 1 Gud. lat., fol. 15r.

Fig.

2. Augustus enthroned, from the Liber floridus. Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 92, fol. 138r.

Fig.

Fig. 3. Two dreams of Nebuchadnezzar, combined, from the Liber floridus. Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 92, fol. 232v.

Fig. 4. Antichrist enthroned on a dragon, from the Liber floridus. Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 92, fol. 62v.

Fig. 5. Antichrist slays the two witnesses in Jerusalem, from Lambert of Saint-Omer’s illustrated Apocalypse. Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel, Cod. Guelf 1 Gud. lat., fol. 14r.

Fig. 6. The circular map of Jerusalem made at the monastery of Saint-Bertin. Saint-Omer, Bibliothèque d’agglomeration de Saint-Omer, MS 776, fol. 50v.

Fig. 7. A crocodile, as imagined by Lambert of Saint-Omer, from the Liber floridus. Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 92, fol. 61v.